InfrastructureFutures:NavigatingtheIntersectionofHumanand NaturalSystems

RichardMacGeorge UniversityoftheSunshineCoastAbstract

Infrastructuresupportshumanwellbeingyetisalsohighlyconsumptive.Thisfundamentalresearchinvestigatestheconceptthatinfrastructurestrategy-makingisentrenchedin theNeolithic,andthatfuturesandforesighttechniquesarerequiredifcivilisationandour biospherearetobebetterservedbyinfrastructure.AreviewofthemacrohistoryofinfrastructuredevelopmentfromtheNeolithicagerevealshowcivilisationshaveevolvedthrough arelianceonsurplusesthatfuelpopulationexpansion,increasingwantandfortification againstthreats.Itisarguedthatformillennia,ideologiesdominatedbyanextractiongrowthparadigmhaveweighedoninfrastructureplanningandstrategymakingapproaches. Todayinfrastructurestrategyisbasedonthecreationofprojectedfuturesbasedonempiricaldatathatareunlikelytoeventuate.Newmethodsofconsideringalternativefutureshave becomenecessaryagainstthisbackdrop,andaparticularpullofthefuturesuggestscloser attentiontoapost-colonialrelationshipwithnatureisrequired.Reducingflowsofliving biologicalmaterialstothebuiltenvironmentgenerallyandinfrastructurespecificallylieat theheartofapotentialnewhumancohabitationwiththeearthsystemthatenduresinto whateverepochfollowstheAnthropocene.

1.Introduction

Thisliteraturereviewleadstoanargumentthatthepresentstateofhumankindrenders outdatedcurrentnotionsofinfrastructurestrategyformulation.Top-down,growth-driven thinking,itisreasoned,haslongdominatedinfrastructuredevelopment,withplanningeffortsfocusedonfutureprojectionsbasedonempiricaldatabutwithinsufficientconsiderationofcomplementarywaysofconsideringalternativefuturesandtheirimplicationsfor infrastructure,andcivilisation.Itisproposedthatthebuiltenvironment,whichincludes infrastructure,hasplayedasignificantroleinthedepletionofnature’sresourcepool,since thecontributionofinfrastructuretotheunsustainableuseofnaturalresourceshasnotbeen addressedfully.Inresponsetotheseclaims,itiscontendedthatconsideringtheinterdependenceofinfrastructurefuturesandcivilizationfuturesnecessitatestheuseofforesight

Emailaddress: rbm009@student.usc.edu.au (RichardMacGeorge)

March10,2023

methodologyinadditiontocurrentempiricalapproaches.Theseconceivablefuturesalso implyabettercoexistencebetweenhumanandnon-humanactorswithintheearthsystemif policyandplanningbecomefocusedontheserelationshipsasameansofminimisingmaterial flows.

2.Methods

Thefollowingexaminationisthestartingpointforarelatedbodyofworkthatlooks athowwellthecurrentwaysofplanninginfrastructurecreateamoresustainablebalance betweenhumanandnaturalwell-being.Theintentistothenexplorehowsocietycanplan andbuildinfrastructurethatismoresociallysustainablesothathumanandnaturalwellbeingworktogetherbetter.Thefirstoftheseelementsisthesubjectofthisarticle.

Theprimarymethodologyforthecollectivestudyisthroughparticipatoryfuturesresearch(Popp,2013a).ThePoppmethodentailsdefiningexistinganddesiredstatesand exploringtheseuntilconsensusamongstparticipantsisreachedoneachofthestates.The participatoryelementoftheresearchistoexplorekeypropositionswitharangeofparticipantsinethicallysoundworkshopsettings.

Inconductingthisexamination,theactualstatecomponentofthemethodologyisconsidered.Doingsoinvolvesestablishingthecontributionofcurrentinfrastructurestrategy makingtowardsocialsustainability.ThereviewisstructuredthroughthelensofInayatullah’s(2008)“FuturesTriangle”,atoolthathelpscontextualisepast,present,andfuture examinationofaspecifictopic.Arrangedasthethreepointsofatriangle,thepointsofthe FuturesTrianglerepresentthe“weightofhistory”,the“pushofthepresent”andthe“pull ofthefuture”.Fergnani(2019)describestheseforcesas:“Thepullsarepossiblevisionsand imagesofthefuture;thepushesarepresenttrendsordrivingforcesaffectingthedirectionof futurechange;theweightsareobstaclesandbarrierstoachievedifferentfutures”(Fergnani, 2019).

Aseriesofpropositionsandquestionsemergingfromtheliteraturereviewarepresented intheresultssection.

3.LiteratureReviewResults

EmployingtheFuturesTriangleofferstheopportunitytoanalyseinfrastructure’smacrohistoryanditsplanning.Importantly,theanalysisframesthepastwithinpresentinfrastructureplanningapproaches.Eachaspectofthepastandpresentcontributestothedevelopmentofinfrastructurestrategyforthefuture.Theapplicabilityofcurrentplanning methodologiesconsideringthesepossibilitiescanalsobeevaluated.Whatthenarethebeginningsofinfrastructureplanninginthesesettings,andhowdoesthisrelatetothecurrent statusofinfrastructureplanning?

3.1.TheWeightofInfrastructure’sPast

TheExtraction-GrowthParadigm,alsocalledthe"LinearEconomy,"andplanningfor infrastructurebothcomefromtheNeolithiceraandhaveessentiallynotchangedsincethen.

March10,2023

Christian(2011,p.140)suggeststhat,oncehuman’sdiscoveredfireinthePalaeolithic period,theprocessofmasteringenergybegan,whichenabledlandclearancesinthelater Neolithicperiod.Thoseclearancesledtocroppingand,forthefirsttime,foodsurpluses.A transitionfromnomadiclifestylestopermanentsettlementsfollowed(Harari,2014,p.85) andsurplusesspawnedelites.Theelitessoughteconomicrentsfromwhichtheyfirstbuilt irrigationsystemsandroads,andthen“palaces,forts,monumentsandtemples”(Harari, 2014,p.101),thebeginningsofinfrastructure.Thisinfrastructurerequiredplanningand soinfrastructureplanning’sbirthcanbetracedtosome12,000yearsago(Derrible,2017,p. 8;Olsson&Paik,2016,p.2).

Withtheestablishmentofsurpluses,elites,rents,andplanning,citystatesdeveloped viathegrowthandinterconnectionofsettlements.Greatersurpluses,orgrowth,drewon theearthsystemandsupportedlargerpopulations.ThecitiesofUruk,UrandBabylon werecentralactorsinthisgrowth,thoughsimilardevelopmentswereoccurringacrossAsia simultaneously.Chinesecitieswere,forexample,alsoemergingindependentlywithclear designprinciples(Milburn,2015,p.210).Theseincludedfortifications,agridsystemof streets,divisionofacityintowardsandwatersystemsalldesignedtosupportlarge,stratified populations.UrbanplanningenabledAlexandriainEgypttosupportapopulationofone millionpeoplebythetimeoftheAppianRomanEmpirearound120AD.Sedlak(2014) chronicleshowtheRomansenabledevengreaterpopulationswithwaterreticulation.While areversaloccurredthroughtheMiddleAges,whencitiesbecamefortifiedandisolated,the Renaissancesaware-emergencetosociety-buildingandcentralisedplanning(Zucker,1955). Indoingso,infrastructureplanninghadmovedfromspendingsurplusestomanaginglarge populations,oftenintheformofthecity-state,yetstillwithinapublicsphere.

Civilisationevolvedtowardnationstates,which“actasasurrogateofthecollective self-interestofthecitizenryintheinternationalarena”(Rifkin,2009,p.2).Infrastructure planningalsobecameanationalendeavour,thepurposeofinfrastructurebeingtheadvancementofnationalsocialdevelopment.Fromcity-states,thenation-stateevolvedmost distinctivelyfromtheearly1800s(Wimmer&Feinstein,2010,p.765)atatimewhen Malthus’(1798)LawofPopulationwarnedofpopulationinducedfoodlimits.Infrastructuresupportedthisnineteenthcenturynational‘scaling’Millward(2004,p.3)duringthe colonisation-enabled(Habib,1975,p.XXVI)firstIndustrialRevolutionthroughnewtechnologyandashiftinfundingandplanning.Whereasinfrastructuretothistimewasfunded fromsurpluses,theseactivitiesbecameself-funding,puttinginfrastructureintoprivatehands (;Bogart2005)(Millward,2004).Thisenabledgreaterinfrastructurescalingthroughthe introductionofcommercialfinance.Naturallymonopolisticinfrastructureenabledexcessiverent-seeking,curbedbythepublicsectorinanewroleasregulator(Derrible,2017, p.11).Thepublicsectorthereafterhashadamixedroleassurplusspendingplannerand rent-regulator,sotheIndustrialRevolutionwasassociatedwithaninfrastructureplanning revolutionalso.

TheSecondIndustrialRevolutioncontinuedwithWesternexpansionandsurpluseseventuallyleadingtoWesternruledglobalinstitutionsandglobalisationafterWorldWarII.In thattimecivilisationmovedintoapost-colonialeraasbetweenhumans,butnotinrelationtonatureanditsbounty.Colonialismandcapitalismintertwinedinthe19thand20th

March10,2023

centuries,tyingculturalandnaturalsystemstoglobalandneoliberalstructures,assertCelemejeretal(2020,pp.1470–8914).WherethefirstIndustrialRevolutionwasdrivenbycoal andsteel,theSecondIndustrialRevolutionwasdrivenbyoil,electricity,andtheTelegraph. PostwarinfrastructurerebuildingbecameimportanttotheWestforreasonsofnationbuilding,modernisationthrougheconomicdevelopment(Rostow,1959)anddemocratisingthe “ThirdWorld”(Helleiner,2014,p.124;Przeworski&Limongi,1997,p.158).Foreignaid wasasignificantdiplomatictooldesignedtostemthesweepofcommunism(Griffin,1991,p. 34)thusplayinganimportantroleingeo-politicalfortification.Internationaldevelopment playedaroleinthisfortificationbychannellingsomesurplusfromhigherincomenationstatesthroughinternationalfinancialinstitutionsas“thearenainwhichdevelopmentwasto bepursued”(Teeple&McMichael,1998,p.147).ThoughBritainandtheUnitedStates,as majoractors,haddifferingapproachestoinfrastructureownership(Hennesy,1993;Jacobson andTarr,1995),infrastructureanditsplanningwasdrivenbytheWestandorientedaround economicgrowthundertheWashingtonConsensusideology.

Thereisacloseconnectionbetweenideologyandinfrastructureorientations,henceideologyhasbeenasignificantfactorinshapingthesedirections(;Josheski,n.d.)(Canning andPedroni,2004;Égertetal.,2009;EsfahaniandRamírez,2003).TheprevalentideologyoftheBrettonWoods-inspiredinternationalmonetarysystemispairedwithmeasuring socialdevelopmentusingKuznets’(1965)GrossDomesticProduct(GDP).GDPimplicitlyadvocatesmaximisationofconsumptionandinvestment-ofwhichinfrastructureplays akeypart-asanationalgoal.AsGDPformsanimportantelementoftheSystemof NationalAccounts(2008)promotedbytheUnitedNations,InternationalMonetaryFund, WorldBank,OECDandEuropeanCommission,consumptionmaximisationbecomesan internationalgoaltoo.YetcontestingthisconsumptionobjectivewasMeadowsetal.(1972) “TheLimitstoGrowth”,whichfollowedsoon,butcoincidentally,aftertheUSabandoned theGoldStandardin1971.Ironicallyperhaps,theGoldStandardalsolimitedgrowth becauseglobalmoneysupplyunderthatregimerelatedtothequantityofgold,afinite resource,circulating.HistoricalcomparisonshowsthattheGoldStandarddeliveredmore moderateandconsistentmoneygrowththanbydelegatingthetasktoacentralbanking committeetocontrolfiatmoneyexpansion(White,2008,p.7).Onesuchexpansionhas beenQuantitativeEasing,whichhastheconsequenteffectofraisingassetprices,increasing creditavailabilityandleadingtohigherconsumptionofgoodsandservices(Watkins,2014, p.433).EachoftheseelementsserveeconomicgrowthasmeasuredbyGDPbutallleadin consequencetofurtherflowsofmaterialfromtheearthsystemtosupportmaterialhuman wellbeing.InthiscontexttheendoftheGoldStandardandthegrowthofmoneysupplythat followedhaveaffectedconstruction,andthereforematerialflows,specificallysincemoney supplyandconstructionactivityarecorrelatedaccordingtoTseandRaftery(2001).

LimitstoGrowth,whichwaswidelybutunfairlydiscredited,didnotinterruptthe business-as-usualprimacyofeconomicgrowth(Turner,2008,p.401).Yetthetopicof sustainabilityreceivedrenewedvigourthroughtheWorldCommissiononEnvironmentand Development’s“OurCommonFuture”report(Brundtlandetal.,1987).Thereportprogresseddiscourseonsustainabledevelopmentbychallengingunfetteredconsumptionand itsrelationtohumanwelfare.Waring’s(1990)researchonfeministeconomicsthenilluMarch10,2023

minatedGDPbeingatoddswithsustainableuseofnaturalcapital.Shewasnotalone, asHawken(2013;1997)Hawkenetal.(2013)andEisenstein(1994,2011)addedtothe dialoguebyassertingtheneedforefficientresourceusetomeethumanneeds.Yet,though infrastructureplannersbeganconsideringenvironmentalimplicationsfrom1990,whichis relativelyrecently(Hironaka,2002;Meyeretal.,1997),theenvironmentremainssubordinate toeconomicdevelopment.

Whilehumanrestraintregardingextractionandgrowthmaynotbeabating,theearth systemis“speaking”moreloudly,ifargumentslikeRifkin’sthatenvironmentalrestrictions hadasignificantroleinthe2008GlobalFinancialCrisisarecorrect(Rifkin,2011,p.31).

RifkinarguestheSecondIndustrialRevolutionendedwhenoilpricesbecameunsustainable,signallingoildepletionandtheendofthefossilfuelera.Cheapgasolineencouraged consumption,andWesterncivilization,especiallytheUS,paidformostofitwithsurpluses fromtheprecedingfourdecades(Rifkin,2011,p.31).Theresultingdebtbubblecollapse weakenedtheUSandstrengthenedChina(Rosecrance,2006),whichhassincechallenged thepost-WorldWarIIdemocraticorder(HameiriandJones,2018).Asaresultofthe SecondIndustrialRevolution’send,theThirdIndustrialRevolution,drivenbydigitalization,began,andhasbeenacceleratedbytheCOVID-19pandemicbeginningin2019and itsripplingeffects.Rifkin(2009)arguestheseturningpointsareachievedwhenthetwokey infrastructuresectorsofcommunicationsandenergyexperienceconcurrentregimechange.

COVID-19confinedpeopletotheirhomesandscreens,andthepost-pandemicenergycrisis, fuelledbyRussiangaspolitics,iscausinganenergyrevolutioninwhichenergysecurityhas onceagainbecomeafundamentalpriorityofpoliticiansandpolicymakers.

Howthendoesthepastplanningandbuildinginfrastructurecontributetothepresent, andhoweffectivelydocurrentinfrastructureplanningapproachesaccountforbothhuman andnaturalwell-being?TheNeolithicAgegaveustheExtraction-GrowthParadigmand infrastructuredevelopment.Yet,sincethen,highersurplusesandthepursuitofexpansion havesappedmaterialsfromtheearthsystem,supportinglargerpopulationsandmorematerialprosperitydespiterisingpollutionandconsequentclimatechange.Infrastructureasan instrumentofgrowthhasbeenacentralthemethroughtime,withplanningbeingdominated byatop-down,economicgrowthledworld-viewinwhichlimitingconsumptionbymanagingdemandforbuilding,ifthatwasanobject,hasnotyetbeenachieved.Untilrecently therefore,infrastructuredevelopmentintentionshavefavouredhumanmaterialwell-being overecology,asindicatedbyclimatechange.Thus,infrastructure’srecenthistorybrings ustothepresent,whenthedesireforhumanwellbeingandclimatechangenowoperateas opposingforces.

3.2.ThePushofInfrastructure’sPresent

Climatechange,pandemicresponse,andpost-pandemicructionsdominatethepresent forpolicymakers.Theseaspects,togetherwithgeopoliticalpressurestowardnationalism(Yang,2017),authoritarianismanddeglobalization,supportcurrentsocialprotection proceduresthatareincreasinginfrastructureinvestment.Planstoexpendsubstantialpublic resourcesoninfrastructureinChina,India,theUnitedStates,UnitedKingdomandmore generallyamongsthighincomecountriesexist,ifIMFrecommendationsarefollowed(Giles, March10,2023

2020;HookandShepherd,2021;HookandThomas,2020;InagakiandLewis,2020;Politi, 2021).TheseprotectionsandasupercyclealignwithRanders,oneoftheauthorsofLimits toGrowth,beliefthat“wewillbefacinganincreasingnumberofproblemsoverthenext 40years,andthatsocietywillrespondbymakinginvestmentsinordertotrytogetridof theseproblems”(Randers,2012,p.7).

BuildingnewinfrastructuretosolveRanders’concernsrisksstokingthefiresincebuilding activitydepletesthelimitednaturalenvironment(Burns,Hope,&Roorda,n.d.;)(Dentinho, 2011;Næss,2006).Forexample,theaveragemoderncityconsumes112tonnesofconstructionmaterialsperperson,excludingthelanditself(Dixonetal.,2018).Thesematerials compriseland,aggregates,cement,steelandenergymaterialflows.Schandletal.(2018) providemoreprecisionaboutthelevelsofmaterialflowsoverthelastfortyyears.Humansextracted22billiontonnesofmaterialin1970foralltheirpurposes,andby2010 thishadincreasedto70billiontonnes,arealcompoundannualgrowthrateof2.94%in thatperiod.Inpercapitaterms,thisextractionequalled7tonnespercapitain1970and 10tonnespercapitain2010.Schandlalsoidentifiestherelationshipbetweenmaterialextractionandeconomicgrowth,notingtheeconomicslowdownduringtheGlobalFinancial Crisisbeingassociatedwithsharpdeclinesinmaterialsextracted.Schandletalarguethis extraction-growthparadigmneedstochangebydecouplingeconomicgrowthfrommaterial flows(Schandletal.,2018,p.827).

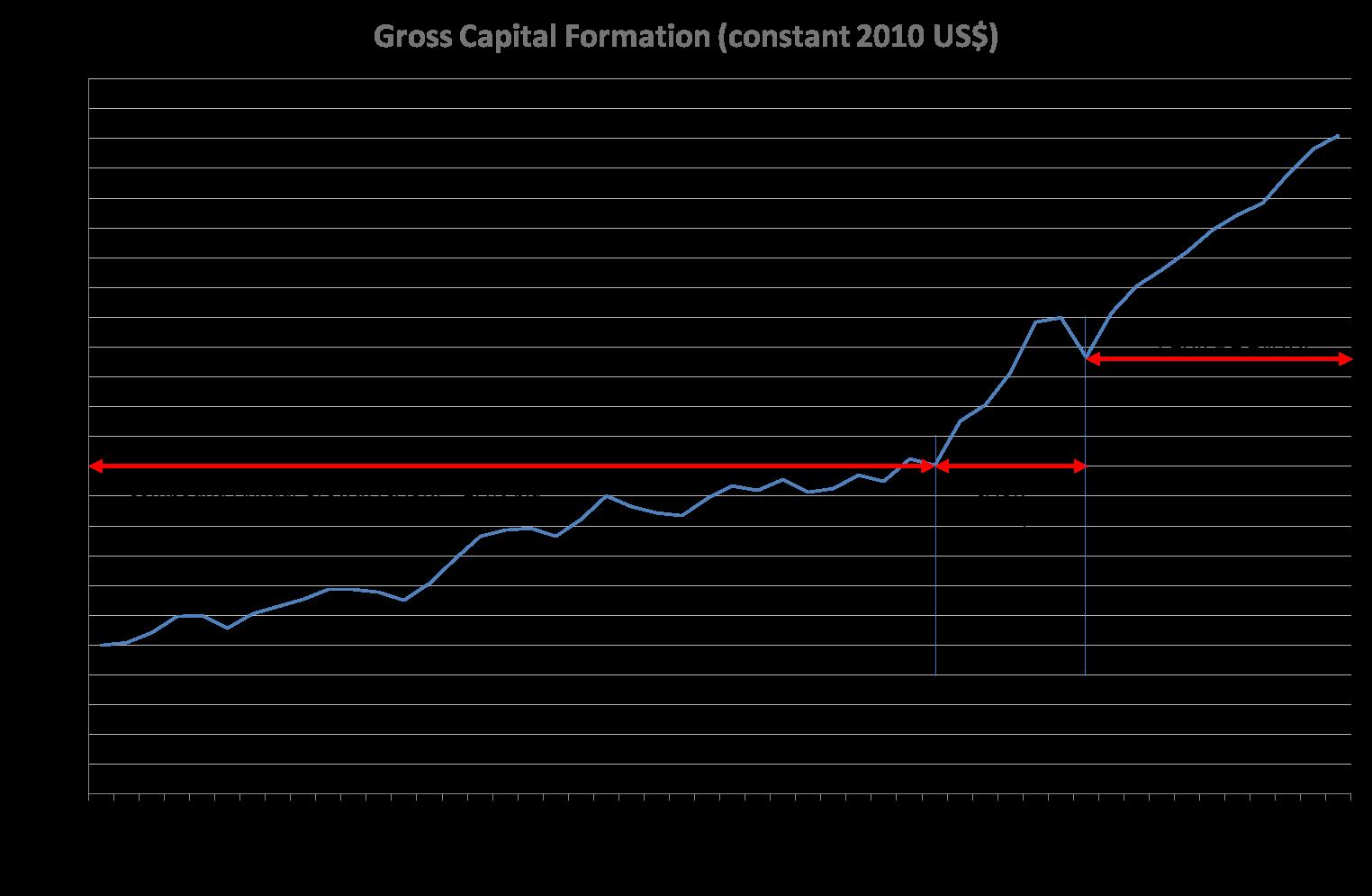

AfurtherusefulproxyforconsideringtherateatwhichthebuiltenvironmentisconsumingnaturalmaterialsistoconsiderGrossCapitalFormation(GCF),whichmeasures buildingoutputs(WorldBank,n.d.).Figure4,below,showsthatGCFin1970amounted toUS$4.989trillion(expressedin2010dollars).In2019GCFreachedUS$22.103trillion (expressedin2010dollars),arealcompoundannualgrowthrateof3.1%.Notably,inthe 1970–2010periodconsideredformaterialflowsabove,therealcompoundannualgrowth rateincreaseinGCFwasvirtuallythesame,at2.98%.

TheaboveindicatorstellusthatdespiteeffortstoachievetheSustainableDevelopment Goals,therateatwhichnaturalmaterialsareconvertedintoinfrastructure-relatedmanufacturedcommoditieshassteadilyincreased.TheUnitedNationsnowstatesthat“growingrelianceonnaturalresourceshassettheEarthonanunsustainablecourse”(United NationsStatisticsDivision,2022).Macrohistoryandthedominantdriversoftodayshow theextraction-growthparadigmisthecentralproblemthatinturnhasthreekeydrivers. Thesedriversarepopulationgrowth,demandforimprovedlivingstandards(want);and threatmanagementthroughfortification.Takingeachinturn:

(i)PopulationgrowthisresponsibleforapproximatelyhalfofGCF’srealgrowth.The numberofpeopleintheworldincreasedfrom3.68billionpeoplein1970to7.67billionpeople in2019(WorldBank,2019b).Thus,populationhasrisensteadilyatarealcompoundannual growthrateof1.5%perannum.Rippleetal.(2017)notetheeffectsofthispopulationgrowth onthecarryingcapacityoftheplanet,muchofwhichisduetotheconversionofnatural capitalintobuildingsalreadyexplored;

(ii)Materialsflowspercapitaareincreasingbecauserealincomesarerisingandpeople spendmore.Overallrealincomeshaveincreasedby5.6%perannumsince1970.Oflow,

March10,2023

Figure1: middleandhighincomepopulations1 ,realincomeshaverisenmostinmiddleincomecountries,witha6.1%realcompoundannualgrowthoverthe1970-2019period(WorldBank, 2019a).Thisissignificantbecausemiddleincomecountriesalsorepresent5.77billion,or 75%,oftheWorld’s2019population(WorldBank,2019b).Povertyalleviationefforts,led bytheWorldBankaspartofitsTwinGoals(Bank,2013),haveseenasignificanteffect onincomes.WorldBankdatashowsthatthoseinextremepoverty(receivinglessthan US$1.90adayin2011terms)hasreducedfrom42.7%oftheworldpopulationin1982to 9.3%in2019.Yetrisingincomesbringrisingconsumption,includingtheuseofnatural materialsusedinthebuiltenvironment.Schandletal’s(2018)workhighlightsthisreality andRanders(2012),inrevisitingtheClubofRome’sLimitstoGrowth,expectsthistrend tocontinue,and;

(iii)Fortificationusuallythroughphysicalprotectioninourmacrohistoryhasmoved toincludegovernmentaleconomicshoringupinresponsetocrises.Financial-economic shocks,theCOVID-19pandemic,climatechangeandtheEuropeanenergycrisisstarting in2022(CalanterandZisu,2022)haveallbeenmetwithfiscalstimuluspoliciesforsocial protection.Forexample,Figure1abovedepictstwoperiodsofhigher-than-averagegrowth

March10,2023

1 TheWashingtonConsensusinvolvesasetofprinciplesadoptedinthelate1980sbyWashingtonDC basedInternationalFinancialInstitutionspromotingfree-marketapproaches.between1970–2019(WorldBank,2019b).ThefirstoftheseoccurredaftertheAsian FinancialCrisis,whentherealGCFcompoundannualgrowthratewas6.0%perannum. ThesecondistheperiodfollowingtheGlobalFinancialCrisis,whenGCFcompoundannualgrowthratewas4.2%perannum.Eachoftheseperiodscoincideswithsignificant increasesinpublicexpenditure,especiallyoninfrastructure(Blanchard,2009;Gatauwa, 2014;Sawyer,2017;Taylor,2010),whichfurthersupportstheproblem-investment-problem paradoxidentifiedbyRanders(Randers,2012,p.7).Furtherprotectiveexpenditureon infrastructurewasexpectedinresponsetotheCOVID19globalpandemic(Denny-Smith etal.,2021;Jallowetal.,2020).Inpractice,thisexpectationhasbeenmetwithadditional fiscalmeasuresspecifictotheCOVID-19Pandemicin2020equaling15.4%ofGDPacross allcountries(Imf,2020).

Forinfrastructure,theabovedriversleadtopresentdemandforinfrastructureservices exceedinginfrastructuresupply.Largeinfrastructure“gaps”exist(Heathcote,2017;Mafusire etal.,2010;Mirza,2009;RozenbergandFay,2019).Ignoringinfrastructurerenewals,the G20GlobalInfrastructureOutlookestimatesaninfrastructuregapofsomeUS$15trillion (G20GlobalInfrastructureHub,2017).Thisamountequalstwo-thirdsof2019GCF,which hastakenallhumanhistorytoaccumulate.Thus,withoutmoderation,infrastructure’s contributiontosustainabilitychallengesislikelytogetworse,despitetherebeingsubstantialworkonmoresustainableinfrastructuresupply(Anderssonetal.,2019;Couttsand Hahn,2015;Infieldetal.,2018;Liqueteetal.,2015;Tzoulasetal.,2007).Whilethatwork evolves,investigatinghowtoplanforlessconsumptiveinfrastructureremainscompelling. Infrastructure’senvironmentalimpact,decouplinganddecarbonization,assignalledbythe SustainableDevelopmentGoalsandSachetal’s(2019)sixtransformations,alltherefore relyonhowsuccessfullyinfrastructureanswerstheassociatedcallstoaction.

ReferringagainthentoInayatullah’s(2008)Future’sTriangle,appropriatequestionsto askare(i)towhatextentistheday-to-daypracticeofinfrastructureplanningdominatedby theweightofthepastdescribedinthisarticle?;and(ii)howareinfrastructurestrategists decreasingmaterialflowstoinfrastructureandconsequentlytheenergyusageandemissions thatcontributetoclimatechange?Inshort,thereisinertiainbringingaboutmeaningfulreductionsinmaterialsuseforinfrastructuregloballybecausematerialefficiencyhasdeclined. Instead,Schandletal(2018,p.834)tellus“theglobaleconomynowneedsmorematerials perunitofGDPthanitdidattheturnofthecentury”andthisisbecauseofthelargeshift ineconomicactivitytolessmaterialefficienteconomies.Astheplanetisapproachingits environmentalboundaries,“thelevelofwellbeingachievedinwealthyindustrialcountries cannotbegeneralisedgloballybasedonthesamesystemsofproductionandconsumption” (Schandletal.,2018,p.835).

Becauseofthecomplexityoftheinfrastructureenvironment,thegreatchallengepresentedabovecausesinfrastructurestrategistsandplannerstoexperienceinertia,or"entrenchment,"asEgyediandSpirco(2011)discovered.Thisisindeedasizeableproblem becauseinfrastructurestrategistsarecaughtbetweenwantingtofindinfrastructurerelated solutionstopromotehumanwellbeing,yettheyarealsoawareofresourcelimitsandthe needforefficiency.Makingmisstepsthatleadtoinfrastructurebeingusedlessthanplanned isnottheirobjective,yetallinfrastructureplannersface“uncertaintyofcapacityutilisa-

March10,2023

tion”(AnsariandHolz,2020),whichmakesforecastingfuturedemandforserviceschallenging(Caldecott,Harnett,Cojoianu,Kok,&Pfeiffer,2016;Sen&vonSchickfus,2020; Shimbar,2021)(Caldecottetal.,2016;Shimbar,2021).Ifinfrastructureisusedlessthan anticipated,somewastageexistsandtheinfrastructurecouldhavebeendesignedtobe smallerinthefirstplace,withlessembeddedcarbon.

Onewaytoseehowwellthefuturewasanticipatedinthepastforspecificinfrastructureistocompareitsplannedversusactualusageinthepresent.Coalfiredpowerstations constructedtwentytothirtyyearsagoinEuropeareanexampleofactualutilisationhavingbeenlowerthanoriginalexpectations(MaterialEconomics,StockholmEnvironment Institute,2018).Environmentalprotectionmeasures,likePigouvianexternalitytaxesthat defendtheenvironmentbycausingemissionsreductions,haveledtothisloweredutilisation.Sodidthebuildersofcoalplantsconsiderthatthisenergysourcemaynotbeusedinto thefuture?TheaffectsofCO2werecertainlyknownfrom1983(Oreskesetal.,2008)and theexternalcostsofcoalfiredpowergenerationhadbeenidentified(Clarke,1997;Clifford, 1984).Yetthesewere“weaksignals”ofapossiblefuture,notgovernmentalpolicyorlegislatedrequirementsatthetime.Bycontrast,thecurrentwarinUkraineandtheconsequent politicsofenergyinEurope,wereweakersignalsstilltoa1980spowersystemsplanner, whentheprevailingenergypolicyleanedawayfromsecurityandtowardefficientprices.Yet thesemorerecentgeopoliticaldevelopmentshavetheopposingeffectofleadingtogreater investmentinfossilfuelsatthecostofdecarbonisation(OsičkaandČernoch,2022).Making senseoftheseuncertaintieswoulddependonwhetherplannersofcoal-firedpowerplants decadesagoconducted"environmentalscanning,"aforesightmappingmethod,tolookfor theseweaksignalsinthefirstplace.Yetthestandardapproachtoplanningthenandnow wastolooktopastgrowthasadominantinputintoprojectingfuturedemand.

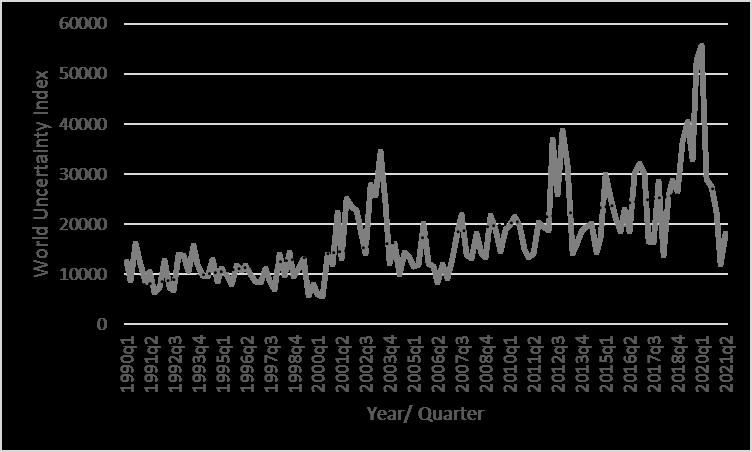

Theuncertaintyofactualutilisationandtheriskof“strandedassets”isincreasing(Ahir, Bloom,&Furceri,2018,2021)asFigure2illustrates,soforesighttechniqueshaveincreasing importance.Thisisbecausehumanityislivinginpost-normaltimes,“thein-betweenperiod whereoldorthodoxiesaredying,newoneshavenotyetemerged,andnothingreallymakes sense”(Sardar,2010,p.1).Sardararguestheuncertaintiescausedbycomplexity,chaosand contradictionshavebecomeadominantfeatureofeverydaylife.Nowotnydescribesthisas the“cunningofuncertainty”inthatthemorehumansknow,themoreisrealisedaboutwhat isunknown.Withthisuncertainty,Sardararguesthatthewaythroughpostnormaltimesis throughcreativityand“ethicalimagination”(Sardar,2010,p.10).Specifically,Sardarand Sweeney(2016)proposethreepotentialtomorrowsforconsiderationtoday:theextended present-extendingthepastdespite‘BlackElephants’;familiarfutures–trendsandimaginingspullinghumanityforwardwhileconsidering‘BlackSwans’;andunthoughtfutures–questioningthevalidityoftheextendedpresentandfamiliarfutures.

Post-normaltimesgiveequalspacetofamiliarandunthoughtfuturesamidsttheswirlof "radicaluncertainty",whichKingandKayandKing(2020)refertoasaspecificsubsetof uncertainty.Understandingradicaluncertaintyrequiresagraspoftwotypesofuncertainty. Thefirstoftheseisresolvableuncertainty,whichisuncertaintythatcanbeknownorgiven probabilitywithgreaterknowledge.Thesecondtype,radicaluncertainty,isunresolvable ambiguityforwhichinclusionvianarrativereasoningandcollectiveintelligencearepath-

March10,2023

waysahead(Kay&King,2020,Chapter22).So,howaretoday’sinfrastructureplanners andpolicymakersfaringinthepost-normalworld,ifpastinfrastructurepolicymakersand plannerswerelesssensitivetothesefuturesandthemanagementofuncertainty?

Oneinsightregardingtheextenttowhichplanningpracticesareadaptingandincorporatingforesighttechniquesrequiredforthepost-normalcomesfromOno(2018).Inteaching infrastructureplannersfromvariousnationsovermanyyears,Onoconcludedthatplanners, whohaveyearsoftechnicalexperience,ofteninthepublicsector,"assumethatdataand informationinthepastandpresentformthebasisoftheirplanning".Thisleavesplanning inSadar’sextendedpresentwhere(Ono,2018,p.232).Thisplanningapproachisnaturalin thefaceofuncertaintyandsupportsEgyedi’s(2011)findingthatinfrastructurecomplexity leadstoentrenchmentbecauseitishardtomakesenseofthefutureforassetsthatcouldlast generations.DuinandLigtvoet(2019)alsofoundthatinfrastructureprovidersarenotattunedtoweakfuturesignalsandinsufficientlyalerttodisruptivechanges.Similarly,Herder etal.(2011),inconsideringrealoptionsasameansofaddressinginfrastructureuncertainty, refertopolitical,institutional“lock-in”(Haan,2011).Whatisdifferentnow,deHaan,argues,isthereis“moredepthtothisuncertaintythanpreviouslyacknowledged”and“the predictabilityofwhatinfrastructurewillandshoulddoisdiminishing(Chester&Allenby, 2020,p.3).Dixonetalsuggestinfrastructureplannersrespondbymovingbeyondthe short-termnatureofprojectionsbyaddressingtheirreluctancetothinkaboutthelonger term“possibilityspace”(Dixonetal.,2018,p.15).Inayatullahexpandsonthisnotionin proposingthatquantitativedriversandthetrendsofthedayarepartofthepushofthe presentratherthantrulyfacingforward(Inayatullah,2008,p.8).Trulylookingahead meansembracingthepossibilityspacebylisteningforthepullsofthefuture,includingcontemplatingtheprospectsoffamiliarandunthoughtfutures,andnavigatingtowardsthose pullsthatarepreferable.

March10,2023

Figure2:WorldUncertaintyIndexwithlineartrendline

Figure2:WorldUncertaintyIndexwithlineartrendline

Thusfarinthisdiscourse,wehavelearnedinfrastructurestrategyisnotattunedtothe pullsofthefutureandisinsteadimbuedwithempiricalapproacheswherethefutureisan extensionofthepast.Strategymakingisalsoinfusedwithpragmatismoverphilosophy, being“goal-oriented,pragmaticand‘makeithappen/cando!’innature”(Voros,2003). Yetstrategisingoughttoinvolve“sense-making”(Healey,2006,p.185)toinformpolicy directions,ratherthanthe“predictandprovide”approachidentifiedbyMarshall(2012). Infrastructurepolicymakinghasalsobeendominatedbygovernmentallineministriesmakingplanssectorbysector.Infrastructureisthereforeacollectivenounforthephysical aspectsofsub-sectorslikeenergy,transport,health,andeducation,likedoctorswhodiscuss theheart,lungsandbrainbutnotthebody.Yet,since2008,nationalgovernmentinfrastructureorganisations(I-bodies)havebeenestablishedprogressivelytoenableanew,systematic,approachtodevisinginfrastructurestrategy.Onewaytodeterminewhetherthese I-bodieshaveadoptednewapproachesthatmightrevealthehuman-natureproblemsofthe extraction-growthparadigmtothemistoexaminetheirstrategydocuments.Lookingfor conformitytoestablishedempiricalproceduresbyscrutinisingreferencestoevidence-based practiseandthephrases"foresight"and"futures"yieldsinsights.Inthisrespect,keystrategydocumentsfromthefiveinfrastructurebodiesforAustralia,andtheAustralianstatesof NewSouthWales,SouthAustralia,Victoria,andWesternAustraliawerereviewedforthis paper.ComparabledocumentsfromthethreeinfrastructurebodiesoftheUnitedKingdom, CanadaandNewZealandwerealsoconsidered,withthefollowingresults:

TheresultsfromTable1illustratehowthekeystrategydocumentsfromleadingI-bodies reflectarelativerelianceonevidenceandapaucityofreferenceto“foresight”and“futures 2 ” ifsimplewordcountsareareasonablereflection.Victoria’sDraft30-YearInfrastructure Strategydoes,however,acknowledgetheroleofscenarioplanninginthecontextofdiffering possiblefutures(InfrastructureVictoria,2021,p.68).Similarly,InfrastructureWestern Australia’sStrongerTomorrowdocumentimaginesthefutureofvarioussectors,though doesnotofferavarietyofpossibilities(InfrastructureWA,2020,p.18).NewSouthWales’ StateInfrastructureStrategy-BuildingMomentumalsodiscussesuncertainfuturesanda varietyofscenariosforasinglesector,ratherthanforallsectors.NewZealand’slatest infrastructurestrategyistobecreditedforrecognisingtherelevanceofalternatefutures consideredbyothersinenergy,transport,andspatialplanning,alongwithindigenousvisionsofthefuture.Consequently,thereissporadicbutemergingengagementbyi-Bodies with,andincorporationof,futuresconcepts.Post-pandemicgrowthambitionsanddecarbonizationmeasures,twosocialsafetynetsperpetuatingtheextraction-growthparadigm, arenonethelessdrivinginfrastructureexpenditure.(Dempsey&Plimmer,2021).

Acentralthemeofthispaperistounderstandtheeffectivenessofinfrastructureplanning forbothhumanandnaturalwellbeing.Areviewoftheword"wellbeing"inTable1reveals limitedreferencetothepositionofwellbeingininfrastructure,howevertheemphasison wellbeingisexpandinginAustralasiaevenifthesereferencesaretohumanwellbeing,which

2 Basedon2019GNIpercapitadata,Low-incomeeconomieshaveanannualpercapitaincomeof <=US$1,035,middle-incomeeconomiesbetweenUS$1,036andUS$12,535percapita/yearandhigh-income economiesexceed$12,536percapitaperyear(Bank,2021).

March10,2023

issimplyonesideofthehuman-naturalwellbeingequation.Strengtheningtheinfrastructure strategicprocesscouldbeonewaytonarrowdowninfrastructureplanningtobothtypes ofwell-being.AmeansofdoingsoinvolvesconsideringVoros’statementthat“Strategic thinkingisaboutexploringoptions;strategydevelopmentisaboutmakingdecisionsand settingdirections,andstrategicplanningisaboutimplementingactions.Problemsarise whenoneoftheseactivitiesiselevatedtopre-eminence”(Voros,2003,p.6).Pre-eminence inthiscontextistheprimacyofdirectionsandactionstowardeconomicgrowthratherthan onmeetinghumanandecosystemneeds.Tomeettheseneedswouldstartwithplanners reflectingonOno’ssuggestionthatthecrucialquestionforinfrastructurestrategistsistoask whatismostimportant.Insodoing,Onoarguesthat“whatisofsupremeimportancefor humanbeingsisthecontinuedflourishingofhumancivilization”(2018,p.4).Infrastructure plannersarethereforeproperlyconcernedwithcivilisationalandenvironmentalorientations, necessitatingplannerstohavetheauthoritytoretrenchandintegratemoreholisticallywith thehighestlevelsofpolicymaking.

Inexaminingthepastandpresentofinfrastructureplanning,anobjectivehasbeentoestablishtheoriginsofinfrastructureplanninganditscurrenttrajectory.Acentralpurposeof doingsohasbeentoassessthefuture-readinessofcurrentinfrastructureplanningpractices. Theburdenofthepastconsistsprimarilyofunwaveringacceptanceofthe12,000-year-old lineareconomybasedonextractionandgrowthasthedefaultparadigm.Populationgrowth, increasingconsumptionperpersonandfortificationaremajordriversofthispast.These forceshavecontributedtothepushofthepresent,whichischaracterisedbygrowinguncertaintyandaclingingtocurrentplanningapproaches.Yetthesepractices,especiallyevidence basedempiricalplanning,arenolongerfitforpurpose.Despitehumanattemptstoconstrain exploitationandexpansion,theearthsystemisprotestingforcefully.Civilizationhasbeen thrustintoapost-normal,highlyunpredictableeraandthefuturesofinfrastructureandits planningareequallyuncertain.Partofthereasonforthiscouldbethattheproblemswith infrastructurestrategymaybetoobigforinfrastructurestrategiststosolvebecausetheyare causedbycivilisation-shapingthatmaythemselvesbetoobigforpoliticsandpolicymaking. Thus,thecurrenttrendsorleadingfactorsinfluencingthepathoffuturechangeforinfrastructurestrategyandplanningarerelatedtoentrenchmentinalineareconomy.Thismodel isincreasinglyunabletosupportthehumanpopulationandindividualmaterialdesiresdue tooverburdeningoftheEarth’snaturalsystems.Asaresult,societyisrapidlyreverting toitsdefaultreactionoffortification.Curiously,traditionalfortificationwasdrivenbypeoplerepellingotherhumans,butmorerecently,ithasbeenmotivatedbyhumansrepelling nature.Aspeoplehavebeenabletoimprovetheirpost-human-colonialisationrelationships withoneanother,perhapstheymightenhancetheirharmonywithnaturebyrenegotiating theircolonialisationofnaturetonew,lessanthropocentrickindsofjustice,asCelermajer examines(Celermajeretal.,2020,p.2).Thistakesthediscoursefromthepushofthe presenttoadiscussionaboutthepullsofthefuture.

3.2.1.ThePullofInfrastructure’sFuture?

Inayatullahin"QuestioningtheFuture"explainsthatbetweenastrology,prophecyand forecastingitisthelatterofthesetechniquesthathasbecomethepreferredapproachof

March10,2023

planners,economistsandsocialscientists(Inayatullah,2005,pp.6–7).Infrastructurestrategyisnodifferentandinfrastructureparticipantsgrapplewithunderstandingfutures,often withoutframingtheirworkinafuturesorforesightsense.Forexample,Onohasfoundthat infrastructureplanners“areforcedtofacethefutureeveryday,withouthavingeverlearned whatthatfuturewouldandcouldbe”(Ono,2018,p.243).Yetfuturesthinkingisessential fordecision-making,especiallyasthefutureisinfluencedbyactionstakentoday.Taken inanothercontext,infrastructurestrategyinvolvesallSardar’sfourlawsoffuturesstudies. Namely,thatfuturesproblemsarewicked,involvediversity,aremulti-dimensionalandare embeddedinthepresent(Sardar,2013).

Toinvestigatetheembeddednessofthefutureinthepresent,itisnecessarytoanalyse otherplanningtechniquesratherthanresorting“primarilytoacertainplanningmethod” (Ono,2018,p.232).Fixedmindsetsleadtoafearoflettinggoofoldpatterns,whereas agrowthmindsetalsofeelsthatloss,thoughismoreopentoproblemsolvingandmutual learning(Farrow,2020,p.907).Opennessbecomesaprecursortoone’swillingnessto engagewithscenarios,asameansofchallengingthepresent(Curry&Schultz,2009,p. 36).Asaresult,firstpullofinfrastructure’sfutureissupplementingconventionalplanning procedureswithopenplanningtechniquesthatconfrontthefutureasanextensionofthe past.

Adoptingopennesshelpsusbecomeattunedtopullsofthefuture.Oncesuchpullstems fromMcAllum’s(2018,6)discourseonrevolutions,whereheproposestheyhavebeenhumancentricuntilnow.Yetmodernityhascausedageophysicalrevolutionthatisexistentialto humansandisnowmarchingtoitsownrhythm.Steffenetal(2018)suggestEarthisat riskofcrossingaplanetarythresholdleadingto"hothouseearth"andmassivedisruptionto humanity.Therealisationthathumanityispartofthesystem,notsimplysittingatopit, isrequiredtheyargue.Toalignwiththenewrhythmmayrequirehumansrethinkingwhat itmeanstobehuman,McAllumcontends(McAllum,2018,p.7).Inthisregard,Raskin (2016,p.25)putsforwardanargumentthatwhatisrequiredisatransitionfromaworld ofstrangerstoaCommonwealthofcitizens.Insodoingthe"conceitofpredictionmustbe abandoned"(Raskin,2016,p.25)andinsteadalternativepossibilitiesmightbeposedto "envisionwhatmightbe"(Raskin,2016,p.25).Thisapproachleadstoataxonomyofthe future,Raskinsuggests,whichcomprisesaseriesofbranchingpossibilities(Raskin,2016,p. 26),comparabletoDynamicAdaptivePolicyPathwaysdevelopedtoconsidersea-levelrise intheNetherlands(Haasnootetal.,2013).

Branchingpossibilitiesdonotsitwellinclosedsystemsofplanningthataretrapped betweentherealmsofpredictionandpossibilities.Yetevenifplannersweretoshifttheir worldviews,changeisalsonecessaryatthehighestlevelsofpublicpolicymakingandamong politicaldecision-makers.Consequently,plannersanddecision-makersmayhaveaninbuilt biastowardfuturescentredoneconomicdevelopmentas"theway,"asdescribedbyInayatullah(2013).Thisfutureispassive,steady,andpredictable,eventhoughitmightnot becomerealised.Thereareotherpossibilitiesoralternativefuturesrequiringexamination, suchasthedisownedfuture,whichisthereality"werejectorcannotnegotiate"(Inayatullah,2013,p.22).Althoughtheintroductionofdisownedfuturesisseenasadversarial,they reallyservetoilluminateourblindspots.Ifso,whataretheblindspotsthatinfrastructure

March10,2023

plannersmightnotseeorareunabletoconfrontthatwouldactuallythreatenthefutureof businessasusual?

Thesignalsforthepullsofthefuturesitatthesurfacelevelwithcivilization’sworries abouttheveryrealdangersofclimatechange,whichtakescentrestageeventhoughitcould sharethestagewiththeemissionsandpollutioncausedbyproductionandconsumption. Eachoftheselinksultimatelytoextractionfromtheearthsystemandsoallarecomplexand interrelated.Dryzekprovidesinsightintothiscomplexitybyexplainingthatenvironmental andhumansocialsystemsarebothcomplicatedinandofthemselves,andhencearedoubly sowhenstackedtogether(Dryzek,2005,p.9).Inthiscontext,itiseasiertoseethelinear economyasanessentialcauseoftoday’swoesandwhyitissochallengingtoaddressthe problem.GiventhatthelineareconomystartedintheNeolithicperiod,ifnotbefore,italso becomesclearertoseehowgrandachallengethetransitionawayfromthelineareconomy hasbecome.Whatthenarethebigdriversthataffectcivilisationanditsentwinementwith infrastructureanditsplanning?

WilliamandHowe’s(1997)studyisrelevanttothefutureofinfrastructurepolicyand couldupendbusiness-as-usualplanning.Saeculums,unitsoftimeapproximatelycomparable toalengthyhumanlife,arestudiedmacrohistorically.CycleswithintheseSaeculumsare established,withfourperiodslastingaround20yearseachandreferredtoas“turnings”. Theturningshavehigh,awakening,unravelling,andcrisisphasesthatcorrelatetothe annualseasonsofSpring,Summer,Autumn,andWinter.StraussandHowe’sprophecy ofanunravellingcoincidingwithwhatisnowknownastheGlobalFinancialCrisis,as wellasthesubsequentpotentialforpandemicandecologicaldistress,havingmaterialised, callsattentiontothepossibilityofasignificantcrisisperiodleadingtoaformofrebirth thatisyettobedeterminedbutchallengingtocomprehension.Onesuchscenarioforthe purposesofDryzek’sdiscourseas“asharedwayofapprehendingtheworld”(Dryzek,2005, p.9)mightcontemplatewhethertheremayyetbeafundamentalhegemonicshiftinthe worldorder,whichisafamiliarfuture.Ifso,afurtherandpossibleunthoughtfuturemight considerwhethertheextraction-growthparadigmanditsdriverswillbeaddressedbythat neworder,orwhethertheexistentialproblemsconfrontinghumanitytodaywillremain unchanged.Withoutaparadigmshift,themostdramaticinterimeffectscouldbethenew order’sconsequentialredistributionofprivilegestothoseitfavours.Eitherpathwouldaffect howhumanslive,theservicestheyseekandtheinfrastructureabletoservethatdemand. Againstthisbackdrop,perhapstheAnthropocene,orHolocene,willbeashort-livedepoch markedbytheperiodinwhichEarthisinfluencedandthoughttobecontrolledbyhumans, withtheendoftheepochbeingahumanrealisationthatnosuchcontroleverexistedand thatearth’ssystemsandadaptationtochangingenvironmentsisrequiredhoweverhumans organisethemselves.Ifthisisthecase,mightthenexterabeoneinwhichtheearthsystem reassertsitselfandhumanityeitheradaptsorperishestotheextentofitsincapacityto adapt?Suchanepochmightnotexcludehumansbutmightcallforhumanstomovefrom keepingnatureoutthroughtheirfortificationsandinsteadtobringhumanityintonature throughanintegrated,post-colonialrelationship.Iftheprospectiveepochbecameknown asthe“Sylvanocene”(Fishel,2022,p.4)orNaturacene-atermcoinedbyGuidoNigrelli as“anerainwhichnaturalprocessesgoverntheentireearthsystem”(Nigrelli,G,2020)-

March10,2023

whatdirectionsthenforinfrastructure?

Onepossibilityisanawakeningtotheimplicationsofincreasedintegrationbetween humansandthebuiltenvironment.Humansystemsarenowdependentoninfrastructure systemsinamannerthatsuggestsanentwiningofthetwointoacyborg-likeorganism,yet onethatremainsdistinctfromtheorganismofearth’secosystem.Human-infrastructure relationsmightwellbecomemoreembeddedthroughdigitisationandvirtualisationinways thatarestilldifficulttofathom.Yetnaturalsystemsremainanorphantothisrelationship, thoughcouldbecomepartofanenduringtrio.Dryzekargues,forinstance,that“weshould treatsignalsemanatingfromthenaturalworldwiththesamerespectweaccordsignals emanatingfromhumansubjects”andthatthecreationofan“non-anthropogenicdemocracy” isaplausibledemocratictheory(Dryzek,1995,p.21).Fishelremindsustoothathumans arejustoneofovereightmillionotherspecies(Fishel,2022,p.3).Considerinthatcontext, forexample,thatvolumeandnumberofspeciesthataredisplacedand/orkilledtoenable human’sbuildings.Whatpotentialmighttherebeforareorientationtowardlivingmaterials andbio-fabricationsthatcouldimprovethewellbeingofnatureandhumansinalastingand symbioticsense?

Suchascenarioasoutlinedabove,andmaybeothers,showthatthepullsofthefuture arerelatedtotheweightsandpushesofthepastandpresentinthatpopulation,individual demand,andafortificationethosallneedtobeaddressed.Someofthesecanbeconfronted throughattemptsatinfrastructuresolutionsthatmightbebettersolvedthroughhigherlevel policydecisions,suchasdevelopmentofpopulationplans,asrecommendedbyTeWaihanga -theNewZealandInfrastructureCommission(TeWaihanga-NewZealandInfrastructure Commission,2022,p.75).Equally,addressingtherootcausesofconsumptionwithits requirementforphysicalgoodstobecarriedthroughthearteriesofinfrastructuremightalso beaddressedthroughbehaviouralshiftsthatarebeyondthewheelhouseofinfrastructure planninginstitutions.Wheretheseinstitutionscanplayaroleisbymovingfromexisting pathdependencytothetypeof“ecosystemicreflexivity”soughtbyDryzek(Dryzek,2016, p.17).Doingsomightleadtosuchinstitutionsadvocatingmorerobustly,forexample,for imposingmaterialsflowtoinfrastructurelimits.Doingsothroughregulationortaxation measuresdesignedtocausesocietytocutitscloth-throughintensificationandusingwhat alreadyexistsbetter-moreassiduously.Considerationofandformingviewsaboutwhat appeartobenon-infrastructuralrelatedpoliciesmightalsobepullsofthefuture.Onesuch exampleisthemonetarysystem,whichhasbeenshowntohaveaninfluenceonthecapital formationofwhichthebuiltenvironmentandinfrastructureformalargepart.

Ultimately,therealmoftheinfrastructureplannerisfarmoredeeplyrootedintime andcivilisationalissuesthanmayappearinthemandateofmajorinfrastructurepolicymakinginstitutions.Complementingexistingplanningapproachestoopen,futures-oriented methodsisthereforehelpfultowhateverfuturesarefacedbycivilisation.Advocatingfor expandedscopeintheserespects,particularlyregardinghuman-naturewellbeingrelations willlikelyincreasetherelevanceofinfrastructurepolicymakinginstitutions.ThoseinstitutionsotherwiseriskshiftinginfrastructurechairsonacivilisationalTitanicwhenoptionsfor changingcoursearestillavailable. March10,2023

4.PropositionsEmergingfromtheReview

Thisliteraturereview,intraversingtheevolutionofcivilisationthroughabuiltenviromentperspective,andconsideringpastandpresentpracticesofinfrastructurepolicymaking, directsustoaseriesofpullsofthefuture.Inall,theseyieldaseriesofpropositions,as follows:

Thefirsthypothesisisthatinfrastructurecontainsaspectsthatareexcessivelyentrenched intheNewStoneAge.Thefundamentalmotivationsofinfrastructuredesignhavenot changedsincetheNeolithic,andcurrentplanningmethodologiesareintertwinedinthe extraction-growthparadigmthatsustainscivilisationtoday.Theseareroadblockstoanew wayofbeing.

Asecondclaimisthatinfrastructureistoofocusedonhumans.Theconstructionof infrastructurepromoteshumanwell-beingviathedeploymentofnatural,human,social, andfinancialresources,butitismainlydependantonnature,whichisfinite.Thehumannatureinteractionisunevenandunsustainableformankind,notnature,sincetheearth system’sadaptabilityisnotdependentonhumanexistence.

Athirdargumentisthatsocietyisonanunsustainablecourse,analogoustoanindustrial wreckingball.Infrastructureconstructionandoperationisasignificantcomponentofalarminglyhighmaterialflows,andisthereforeaccountableformuchlossofEarth’sbiodiversity, whichcivilisationviewsasaresourcepool.

Fourth,itisarguedthattheHuman-Natureinteractioniscomparabletohumancolonisation.Humansarenolongerinacolonialrelationshipwithoneanother,byandlarge,but theyarestillinacolonialrelationshipwithnature.Climatechangeisamplifyingtheearth’s voiceandgivingvoicetoitsversionofacivilrightsmovement.

Theprecedingtwopremisescombinetoformafifthpremiseconcerningsocietalsustainability.Theevidencespeakstoanewbargainwithnatureifhumankindistothrivein thefuture.Civilisationwouldbenefitfromenteringapost-colonialrelationshipwiththe earthsystembyclearlyrecognisingthatwellnessinvolvesbothhumanandenvironmental components.Asaresult,happinessisacommongoal.

Sixth,the"ThreeMusketeers"ofpopulationgrowth,individualconsumption,andfortificationsarethreemajordriversofmaterialflowstoinfrastructure,allofwhichsubstantially contributetobiodiversityloss,climatechange,andpollution.Asaconsequence,itisadvocatedthatthematerialsflowmetricbecomeofprimaryimportancetoinfrastructure development.

Thedriversofinfrastructuresolutionshavegrownsoentrenchedthat,accordingtoa sevenththesis,infrastructurepolicymakinghasbecome"stuckintraffic."Thecontinuous weightingofempiricalprocedures,whichwouldbestrengthenedbylesscomfortablebut equallyessentialFuturesandForesightmethods,isaprimarysourceofthisentrenchment. Thesetechniques,takentogether,mayassistinfrastructurepolicymakersinbetterintegratinghumanandecologicalcomponentsofwell-beingasfundamentalcriterionforinfrastructuredevelopment.

Humansresideontopoftheglobe,asthoughtheyareseparatefromtheecologyofwhich theyareapart.Thisgapisworsenedbytheconstructedworldinwhichpeoplelive,andwith

March10,2023

whichhumansareprogressivelyintegratingandvirtualising.Thishuman-builtcouplemust becomeanintegratedhuman-built-naturaltriadifhumankindistoflourishindefinitely,as aneightproposition.

Ninth,ratherthanfortificationagainstnature,itisclaimedthatpeopleneedanew connectionwithnaturethatisdiametricallyopposedtofortifyingtokeepnatureout,and insteadseeksmethodsformankindtointeractwiththeearthsysteminfundamentally differentways.

Asaconsequenceoftheprecedingpremises,afinalthesisdevelops,accordingtowhicha roadaheadmayfavourgrowingthingsabovebuildingthings,sincebuildingnecessitatesthe displacementanddeathofbuildingmaterials.Asaresult,thisanalysisconcludeslogically thatsuccessfulintegrationofhuman,built,andecologicalsystemsisrequiredforhumanity toenduretheAnthropocene.Putsimply,economic"growth"dependsonnature’sgrowth.

Insummary,climatechangeisamplifyingtheearth’s"voice"andspeakingtonature’s versionofacivilrightsmovement.Civilisationwouldbenefitfromenteringapost-colonial relationshipwiththeearthsystembyclearlyrecognisingthatwellnessinvolvesbothhuman andenvironmentalcomponents-happinessisthereforeacommongoal.Theauthorargues thatinfrastructurepolicymakingismiredintheextraction-growthparadigmassumption.It isalsoarguedthatpolicymakersneedtobetterintegratehumanandecologicalcomponentsof well-beingasfundamentalcriterionforinfrastructuredevelopment.Theanalysisconcludes thatsuccessfulintegrationofhuman,built,andecologicalsystemsisnecessarytohuman survival.

5.FurtherResearch

Againstthebackgroundoftheprecedingpropositions,anumberofissuesariseforfurtherconsideration,suchas:whataretheplausibleandpreferredfuturesforcivilisationin 2100,forexample,thatmaybeenvisionedtoday?Whatinfrastructureservicesmaybeenvisagedtoberequiredtomeetagenerallyacknowledgedrealisticandpreferredfuturebased onaconsensusviewofrepresentativeswithinfrastructure,environmental,humanwellness, andculturalperspectives?Givensuchcircumstances,whatfundamentalmodificationsin infrastructurepolicycouldberequiredinthenearandmediumtermtoallowthatchosen futureandtherelatedsupportinginfrastructure?What,therefore,aretheprimarypolitical,social,technological,economic,andenvironmentalproblemsthatmustbeaddressedin ordertoachievethefundamentalchangeininfrastructurepolicyandplanningthatarepresentativegrouphasidentified?Howmayinfrastructureplanningmethodologieshelpor hinderthetransitiontothisenvisionedfuture?Forexample,willalternatemethodologies likeasforecastingandforesightcometosupplementempiricalmethods,andifso,how? Perhapsmostsignificantly,whatdomembersofarepresentativegroupbelievewillhappen tomankindifthechangesdescribeddonotoccur?

Toshedlightontheissuesraisedinthisliteraturereview,collaborationwithothers isrequiredtovalidate,orotherwise,thecurrentstateofinfrastructurepolicymakingand planning,aswellastheextenttowhichcurrentapproachesaresuitableforacommonly

March10,2023

aspiredtargetfuturestateofpolicymaking.Participatoryresearchisrequiredinthisenvironmenttoinvestigateimportantideaswithadiversevarietyofparticipantsinethically soundworkshopsettings.

References

(2008). UNSystemofNationalAccounts

(2017).GlobalInfrastructureOutlook:Infrastructureinvestmentneeds,50countries,7sectorsto2040. G20GlobalInfrastructureHub. (2018). (2021). (2022a).

(2022b).RautakiHanganga-o-Aotearoa. TeWaihanga-NewZealandInfrastructureCommission Ahir,H.,Bloom,N.,&Furceri,D.(2018).

Ahir,H.,Bloom,N.,&Furceri,D.(2021).

Amara,R.(1974).Thefuturesfield:Functions,forms,andcriticalissues. Futures,6(4),289–301.

Andersson,E.,Langemeyer,J.,Borgström,S.,Mcphearson,T.,Haase,D.,Kronenberg,J.,&Baró,F. (2019).EnablingGreenandBlueInfrastructuretoImproveContributionstoHumanWell-Beingand EquityinUrbanSystems. Bioscience,69(7),566–574.

Ansari,D.&Holz,F.(2020).Betweenstrandedassetsandgreentransformation:Fossil-fuel-producing developingcountriestowards2055. WorldDevelopment,130,104947–104947.

Australia,I.(2016).

Australia,I.S.(2020).

Bank,W.(2013). Bank,W.(2019a). Bank,W.(2019b).

Bank,W.(2021).

Blanchard,O.(2009).LessonsoftheGlobalCrisisforMacroeconomicPolicy.

Brundtland,G.H.,Khalid,M.,Agnelli,S.,Al-Athel,S.,&Chidzero,B.(1987). Ourcommonfuture.New York,8.

Burns,P.,Hope,D.,&Roorda,J.

Calanter&Zisu(2022).EUPoliciestoCombattheEnergyCrisis.

Caldecott,B.,Harnett,E.,Cojoianu,T.,Kok,I.,&Pfeiffer,A.(2016).

Canning,D.&Pedroni,P.(2004).

Celermajer,D.,Chatterjee,S.,Cochrane,A.,Fishel,S.,Neimanis,A.,O’brien,A.,&Waldow,A.(2020). JusticeThroughaMultispeciesLens. ContemporaryPoliticalTheory,19(3),475–512. Chester,M.V.&Allenby,B.(2020).

Christian,D.(2011).

Clarke,L.B.(1997).Externalitiesandcoal-firedpowergeneration. AtmosphericEnvironment,31,1381–1381.

Clifford,T.E.(1984). Externalcostsofelectricpowerfromcoal-firedandnuclearpowerplants.Retrieved fromCaliforniaUniv.SantaBarbara(USA.

Coutts,C.&Hahn,M.(2015).GreenInfrastructure,EcosystemServices,andHumanHealth. International JournalofEnvironmentalResearchandPublicHealth,12(8),9768–9798.

Curry,A.&Schultz,W.(2009).Roadslesstravelled:differentmethods,differentfutures. JournalofFutures Studies,13(4),35–60.

Dator,J.(1995).WhatFuturesStudiesis,andisNot. RetrievedfromHawaiiResearchCenterforFutures Studieswebsite Dempsey,H.&Plimmer,G.(2009).

Denny-Smith,G.,Sunindijo,R.Y.,Loosemore,M.,Williams,M.,&Piggott,L.(2021).HowConstruction

March10,2023

EmploymentCanCreateSocialValueandAssistRecoveryfromCOVID-19. Sustainability:Science PracticeandPolicy,13(2),988–988.

Dentinho,T.P.(2011).Unsustainablecities,atragedyofurbaninfrastructure. RegionalSciencePolicy& Practice,3(3),231–247.

Derrible,S.(2017).Complexityinfuturecities:theriseofnetworkedinfrastructure. InternationalJournal ofUrbanSciences,21(sup1),68–86.

Dixon,T.,Connaughton,J.,&Green,S.(2018).

Dryzek,J.S.(1995).Politicalandecologicalcommunication. EnvironmentalPolitics,4(4).

Dryzek,J.S.(2005).

Dryzek,J.S.(2016).InstitutionsfortheAnthropocene:GovernanceinaChangingEarthSystem. British JournalofPoliticalScience,46(4),937–956.

Duin,P.V.D.&Ligtvoet,A.(2019).Linesintothefuture.ExploringhowDutchinfrastructureproviders organizeandmanagetheirforesightprocesses. Futures,105,187–198.

Égert,B.,Kozluk,T.J.,&Sutherland,D.(2009).

Egyedi,T.&Spirco,J.(2011).Standardsintransitions:Catalyzinginfrastructurechange. Futures,43(9).

Eisenstein,C.(1994).

Eisenstein,C.(2011).

Esfahani,H.S.&Ramírez,M.T.(2003).Institutions,infrastructure,andeconomicgrowth. Journalof DevelopmentEconomics,70(2),443–477.

Farrow,E.(2020).

Fergnani,A.(2019).FuturesTriangle2.0:integratingtheFuturesTrianglewithScenarioPlanning. Foresight, 22(2),178–188.

Fishel,S.R.(2022).Theglobaltree:ForestsandthepossibilityofamultispeciesIR. KokusaigakuRevyu =ObirinReviewofInternationalStudies,pages1–18.

Gatauwa,J.M.(2014).The2008GlobalEconomicCrisisandPublicExpenditure:ACriticalReviewof theLiterature. AdvancesinManagementandAppliedEconomics,4(2),131–131.

Giles,C.(2020).IMFcallsonrichnationstoboostpublicinvestment. FinancialTimes Government,N.(2018).

Griffin,K.(1991).Foreignaidafterthecoldwar. DevelopmentandChange,22(4),645–685.

Haan,J.D.(2011).Flexibleinfrastructuresforuncertainfutures. Futures,43(9),921–922.

Haasnoot,M.,Kwakkel,J.H.,Walker,W.E.,&Maat,J.T.(2013).Dynamicadaptivepolicypathways:A methodforcraftingrobustdecisionsforadeeplyuncertainworld. GlobalEnvironmentalChange:Human andPolicyDimensions,23(2),485–498.

Habib,S.I.(1975).

Hameiri,S.&Jones,L.(2018).Chinachallengesglobalgovernance?Chineseinternationaldevelopment financeandtheAIIB. InternationalAffairs,94(3),573–593.

Harari,Y.N.(2014).

Hawken,P.,Lovins,A.B.,&Lovins,L.H.(2013).

Healey,P.(2006).

Heathcote,C.(2017).

Helleiner,E.(2014).

Hennesy,P.(1993).

Herder,P.M.,Joode,J.D.,Ligtvoet,A.,Schenk,S.,&Taneja,P.(2011).Buyingrealoptions-Valuing uncertaintyininfrastructureplanning. Futures,43(9),961–969.

Hironaka,A.(2002).TheGlobalizationofEnvironmentalProtection:TheCaseofEnvironmentalImpact Assessment. InternationalJournalofComparativeSociology,43(1),65–78.

Hook,L.&Shepherd,C.(2021). Hook,L.&Thomas,N.(2020).

Imf(2020).

Inagaki,K.&Lewis,L.(2020). Inayatullah,S.(2005). March10,2023

Inayatullah,S.(2008).Sixpillars:futuresthinkingfortransforming. Foresight,10(1),4–21.

Inayatullah,S.(2013). Futuresstudies:theoriesandmethods.There’saFuture:VisionsforaBetterWorld BBVA,Madrid.

Infield,E.M.H.,Abunnasr,Y.,&Ryan,R.L.(2018).

Infrastructure,W.A.(2020).

Jacobson,C.A.&Tarr,J.A.(1995).

Jallow,H.,Renukappa,S.,&Suresh,S.(2020).

Josheski,D.InfrastructureInvestmentandGDPGrowth:AMeta-RegressionAnalysis. SSRNElectronic Journal

Kay,J.A.&King,M.A.(2020).

Kuznets,S.(1965). TowardsaTheoryofEconomicGrowth“inEconomicGrowthandStructure.NewYork, WWNorton&Co.

Liquete,C.,Kleeschulte,S.,Dige,G.,Maes,J.,Grizzetti,B.,Olah,B.,&Zulian,G.(2015).Mapping greeninfrastructurebasedonecosystemservicesandecologicalnetworks:APan-Europeancasestudy. EnvironmentalScience&Policy,54,268–280.

Mafusire,A.,Anyanwu,J.,Brixiova,Z.,&Mubila,M.(2010).Infrastructuredeficitandopportunitiesin Africa. AfricanDevelopmentBankEconomicBrief,1,1–15.

Malthus,T.(1798).

Marshall,T.(2012).

Mcallum,M.(2018).Allrevolutionsareequal;butsomearemoreequalthanothers. JournalofFutures Studies,23(2),1–12.

Meadows,D.H.,Meadows,D.L.,Randers,J.,&Behrens,W.W.(1972). Thelimitstogrowth,volume102. NewYork.

Meyer,J.W.,Frank,D.J.,Hironaka,A.,Schofer,E.,&Tuma,N.B.(1997).TheStructuringofaWorld EnvironmentalRegime. InternationalOrganization,51(4),623–651.

Milburn,O.(2015).Urbanizationinearlyandmedievalchina:Gazetteersforthecityofsuzhou.University ofWashingtonPress.

Millward,R.(2004).Europeangovernmentsandtheinfrastructureindustries,c.1840-1914. EuropeanReview ofEconomicHistory,8(1),3–28.

Mirza,S.(2009).

Næss,P.(2006).UnsustainableGrowth,UnsustainableCapitalism. JournalofCriticalRealism,5,197–227. Nigrelli,G.(2020).

Of,C.G.(2021).

Olsson,O.&Paik,C.(2016).Long-runculturaldivergence:EvidencefromtheNeolithicRevolution. Journal ofDevelopmentEconomics,122,197–213.

Ono,R.(2018).IntroducingFuturesConceptstoExpertsinPublicServicesinDevelopingCountries. World FuturesReview,10(3),231–246.

Oreskes,N.,Conway,E.M.,&Shindell,M.(2008).FromchickenlittletoDr.Pangloss:WilliamNierenberg, globalwarming,andthesocialdeconstructionofscientificknowledge. HistoricalStudiesintheNatural Sciences,38(1),109–152.

Osička,J.&Černoch,F.(2022).EuropeanenergypoliticsafterUkraine:Theroadahead. EnergyResearch &SocialScience,91,102757–102757.

Politi,J.(2021).

Przeworski,A.&Limongi,F.(1997).Modernization:Theoriesandfacts. WorldPolitics,49(2),155–183.

Randers,J.(2012).

Raskin,P.(2016).

Rifkin,J.(2009).

Rifkin,J.(2011).

Ripple,W.J.,Wolf,C.,Newsome,T.M.,Galetti,M.,Alamgir,M.,&Crist,E.(2017).WorldScientists’ WarningtoHumanity:ASecondNotice. Bioscience,67(12),1026–1028.

Robèrt,K.H.,Daly,H.,Hawken,P.,&Holmberg,J.(1997).Acompassforsustainabledevelopment.

March10,2023

InternationalJournalofSustainableDevelopmentandWorldEcology,4(2),79–92. Rosecrance,R.(2006).PowerandInternationalRelations:TheRiseofChinaandItsEffects. International StudiesPerspectives,7(1),31–35.

Rostow,W.W.(1959).TheStagesofEconomicGrowth. TheEconomicHistoryReview,12(1),1–16. Rozenberg,J.&Fay,M.(2019).

Sachs,J.D.,Schmidt-Traub,G.,Mazzucato,M.,Messner,D.,Nakicenovic,N.,&Rockström,J.(2019).Six TransformationstoachievetheSustainableDevelopmentGoals. NatureSustainability,2(9),805–814. Sardar,Z.(2010).Welcometopostnormaltimes. Futures,42(5),435–444. Sardar,Z.(2013).

Sardar,Z.&Sweeney,J.A.(2016).TheThreeTomorrowsofPostnormalTimes. Futures,75,1–13. Sawyer,M.(2017).

Schandl,H.,Fischer-Kowalski,M.,West,J.,Giljum,S.,Dittrich,M.,Eisenmenger,N.,&Fishman,T. (2018).Globalmaterialflowsandresourceproductivity:Fortyyearsofevidence. JournalofIndustrial Ecology,22(4),827–838.

Sedlak,D.(2014).

Sen,S.&Schickfus,M.T.(2020).Climatepolicy,strandedassets,andinvestors’expectations. Journalof EnvironmentalEconomicsandManagement,100,102277–102277. Shimbar,A.(2021).Environment-relatedstrandedassets:Anagendaforresearchintovaluedestruction withincarbon-intensivesectorsinresponsetoenvironmentalconcerns. RenewableandSustainableEnergy Reviews,144,111010–111010.

Taylor,J.B.(2010).GettingBackonTrack:MacroeconomicPolicyLessonsfromtheFinancialCrisis. Review,92.

Teeple,G.&Mcmichael,P.(1998).DevelopmentandSocialChange,aGlobalPerspective. Labour/Le Travail,41,313–313. Treasury,H.(2020).

Tse,R.Y.C.&Raftery,J.(2001).Theeffectsofmoneysupplyonconstructionflows. Construction ManagementandEconomics,19(1),9–17.

Turner,G.(2008).AcomparisonofTheLimitstoGrowthwith30yearsofreality. GlobalEnvironmental Change:HumanandPolicyDimensions,18(3),397–411.

Tzoulas,K.,Korpela,K.,Venn,S.,Yli-Pelkonen,V.,Kaźmierczak,A.,Niemela,J.,&James,P.(2007). PromotingecosystemandhumanhealthinurbanareasusingGreenInfrastructure:Aliteraturereview. LandscapeandUrbanPlanning,81(3),167–178.

Victoria,I.(2021).

Voros,J.(2003).Agenericforesightprocessframework. Foresight,5(3),10–21. Waring,M.(1990).

Watkins,J.P.(2014).QuantitativeEasingasaMeansofReducingUnemployment:ANewVersionof Trickle-DownEconomics. JournalofEconomicIssues,48(2),431–440. White,L.H.(2008).

William,S.&Howe,N.(1997). TheFourthTurning:AnAmericanProphecy.NewYork,BroadwayBooks. Wimmer,A.&Feinstein,Y.(2001).TheRiseoftheNation-StateacrosstheWorld,1816to. American SociologicalReview,75(5),764–790.

Yang,M.(2017).

Zucker,P.(1955).SpaceandmovementinHighBaroquecityplanning. TheJournaloftheSocietyof ArchitecturalHistorians,14(1),8–13.