College

Tiger alumna and Gotham Writers Workshop Dean shows you how to turn midnight mischief, beautiful mistakes and unreliable memories into lasting literature.

(Expect edits from your former roommates.)

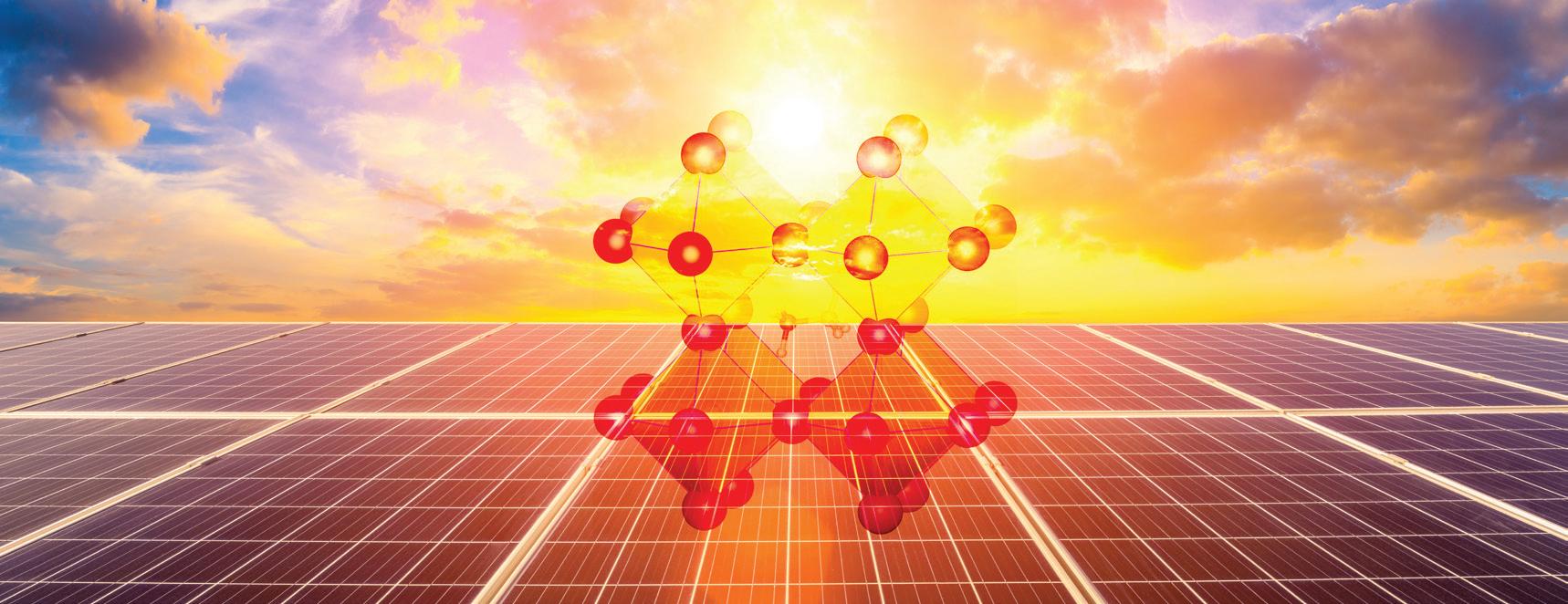

IN THE LINE OF FIRE

Earlier this year, photojournalist Patrick T. Fallon captured the aftermath of California’s relentless wildfires with unflinching clarity, from the skeletal remains of homes in Altadena and Pacific Palisades to the broader devastation visible from the sky.

For more than a decade, Fallon, BJ ’11, has documented the state’s most destructive blazes, including the Thomas, Woolsey and Camp Fires. This aerial image, taken on Jan. 8, 2025, shows thick smoke from the Eaton and Palisades Fires blanketing the Los Angeles skyline. It’s a stark visual testament to the region’s vulnerability.

Fallon has spent his career distilling catastrophe into singular human moments, whether documenting the wreckage of Joplin’s tornado, the political turmoil of a U.S. election or the quiet grief of a man standing in the ashes of his family home. His award-winning photography has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Getty’s global archives, ensuring that these fleeting, harrowing scenes are not lost to time.

Support moments they’ll never forget with the Mizzou Traditions Fund.

Scan to give or visit mizzou.us/traditionsfund

This town tunes to a different frequency when the semester ends and the campus clears. The volume drops. Sidewalks open. Parking lots empty. You can walk into any restaurant and sit wherever you want.

Summer in Columbia isn’t just quieter. It’s weirder. The students who stick around stretch out, some picking up campus jobs, others diving into fun courses like History of Popular Music in half-empty lecture halls. Faculty and staff stay too, and they know the rhythm. They bike to work. They linger at lunch. You’ll find them at Ragtag Cinema catching a matinee, iced coffee in hand. The season feels like a 90-day secret. Thankfully, it doesn’t last, which makes it more magical. By late August, the city transforms. The quiet gives way to freshmen finding their footing and athletes training on the fields. Grocery stores bustle. Classes fill. In the student-heavy neighborhoods east of campus, couches migrate to porches and claim their spot for the season.

The summer before my senior year, I worked at the Blue Note. I’d show up early evenings to quarter limes and restock the bar, then stay for the indie bands and the late shifts, walking out at 2 a.m. with $150 in tips and ringing ears, feeling like a millionaire. During the day, I was flattening century-old newspapers at the State Historical Society of Missouri to be photographed on microfilm. I was sunburned and basically living at KCOU, where I played records for anyone still in town with a half-working radio and a fan in the window. The station ran 24/7. So did I.

Sunsets brought porches, easy laughter and the flicker of lightning bugs. The whole town seemed to pause. Much of that still holds true, but now the Mizzou International Composers Festival unfolds across Columbia every July, with events at the Jeanne and Rex Sinquefield Music Center and the Missouri Theatre. It’s among the country’s most forward-thinking summer programs of its kind, where student composers and musicians bring contemporary scores to life through ensemble-in-residence Alarm Will Sound. The New York-based group also will perform works by distinguished guest composers Hilda Paredes and Judd Greenstein.

This issue of MIZZOU picks up the same offbeat rhythm of summers in Columbia. Two families take to the water in separate sailing stories. One alum chases presidential libraries across America. A campus researcher listens in on insect vibrations. Ag scientists grow rice in the Bootheel. A former U.S. ambassador reflects on 30 years in diplomacy. We spotlight alumni behind standout podcasts and studentathletes landing perfect scores.

Much like those summer months, the stories twist, linger and sometimes circle back, by the end changed just enough to feel new.

— RANDALL ROBERTS, BA ’88 Editor

Editorial and Advertising

Executive Editor

Robert D. Waller

Editor Randall Roberts, BA ’88

Art Director

Blake Dinsdale, BA ’99

Class Notes Editor

Jennifer Manning, BJ ’18

Advertising Scott Dahl: 573-882-2374

Mizzou Alumni Association

123 Reynolds Alumni Center 704 Conley Avenue Columbia, MO 65211 573-882-6611

Executive Director, Publisher Todd A. McCubbin, M Ed ’95

Mission

The Mizzou Alumni Association proudly supports the best interests and traditions of Missouri’s flagship university and its alumni worldwide.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President Leigh Anne Taylor Knight, BS HES ’89, BS Ed 90, M Ed ’91

President-elect Kim Utlaut, BS ’89

Immediate Past President Mindy Mazur, BA ’99

Treasurer Kevin Gibbens, BS BA ’81

Secretary Todd McCubbin, M Ed ’95

Directors Joanna Russell Bliss, BA ’07, BSEd ’07; Brent Buerck, MPA ’05; Clarissa Cauthorn, BS ’15; Morgan Corder, BA ’18; Renita Duncan, BS Acc, M Acc ’08; Christine Holmes, BS BA ’10, MBA ’17; Chris Hurt, BA ’88; Matt Jenne, BS CiE ’97, MBA ’15; Cheryl Jordan, BA ’84; Col. Pete O’Neill, BA ’00; Daniel Pierce, BA, BJ ’99; Gabriela Ramirez-Arellano, BS BA ’91; Amber Rowson, BS ME ’99; BS ’07; Mark Russell, BJ ’84; Nick Ruthmann, BS ’05, MD ’13; Vanessa Vaughn West, BA ’99 Janet Wheatley, BS HE ’77; Justin Wilson, BS ’07

Student Representative Bhushan Sreekrishnavilas

Editors Emeriti Karen Worley, BJ ’73, and Dale Smith, BJ ’88

MIZZOU magazine

Spring 2025, Volume 113, Number 3 Published triannually by the Mizzou Alumni Association

ISSN 2833-3970

Address changes: mizzou.com/update or call 800-372-6822

Comments: mizzou@missouri.edu mizzou.com/magazine

Opinions expressed in this magazine do not necessarily reflect the official position of the University of Missouri or the Mizzou Alumni Association. ©2025

2025 Kemper Award Winners Each spring, Mizzou leaders and Commerce Bank executives surprise faculty members with William T. Kemper Fellowships for Teaching Excellence. Videos capture the moments this year’s recipients learn they’ve been selected, each receiving a $15,000 award in recognition of their exceptional teaching. Learn more about the fellowship and the tradition behind it at mizzou.us/kemper25

Nina Mukerjee Furstenau, BJ ’84, is the author of Green Chili and Other Impostors and Biting Through the Skin: An Indian Kitchen in America’s Heartland, the latter of which won the 2014 M.F.K. Fisher Grand Prize for Excellence in Culinary Writing. She traveled to the Missouri Bootheel for “Rice Country, USA,” Page 38.

Kelly Caldwell, BJ ’88, teaches memoir writing and leads the faculty at Gotham Writers Workshop. Her work has appeared in Vox, House Beautiful and Newsday. Read her cover story — “How to Write Your Mizzou Memoir” — on Page 14.

About the cover

Tony Rehagen, BA, BJ ’01, has written for GQ, The Columbia Journalism Review and Next Wave: America’s New Generation of Great Literary Journalists. He profiled the sailing Kuhners for “Found at Sea,” Page 24.

Serge Bloch is a French illustrator and author known for his minimalist, expressive line drawings featured in children’s books, magazines and newspapers worldwide. His work includes the popular “Max et Lili” series and collaborations with The New York Times, The Washington Post and major brands such as Hermès. He illustrated “How to Write Your Mizzou Memoir,” Page 14.

A tip of the red editor’s pen goes to art director Blake Dinsdale, BA ’99, who designed this ode to messy, meaningful memory. The Society of Publication Designers recently recognized his work, and photography from Mizzou Visual Productions, across five categories during its 60th annual awards.

facebook.com/mizzou x.com/mizzou

instagram.com/mizzou @mizzou

1 First Look

Photojournalist Patrick T. Fallon captured Los Angeles glowing beneath smoke from the Eaton and Palisades fires.

6 Around the Columns

A bounty of recent Mizzou achievements; a health data engineer advancing AI; researchers studying quasiparticles; and introducing new women’s basketball coach Kellie Harper.

44 Mizzou Alumni News

From presidential library quests to groundbreaking blood drives, Mizzou alumni have made an impact. Plus, highlights from Mizzou Giving Day 2025, and celebrating the recipients of the 2025 Geyer Award.

Class Notes

Mizzou grads keep making news: new jobs, new places and new faces. An update on what’s happening.

49 Alumni Podcasts

Whether in front of the mic or behind it, Tigers are entertaining and educating on podcasts including “Wiser Than Me with Julia Louis-Dreyfus.”

64

Celebrating Mizzou gymnast Helen Hu’s flawless performances during a banner year for the program.

Council for Advancement & Support of Education Awards

2024: District VI Award: General Interest Magazine

2022: Bronze, Periodical/Magazine Design

2021: Gold, Feature Writing (“Who Was I in College?,” Winter 2020)

2020: Bronze, Feature Writing (“Forever Young,” Spring 2019) 2019: Bronze, General Interest Magazine

Society for Publication Designers Awards

2025 medal finalists: “The Guardians of Silent Worlds,” Spring 2024; “The Invisible Networks,” Fall 2024

2025 merit awards: “Hog Harmony,”(2) Winter 2024; “Capturing Jumpers,” Spring 2024

2024 merit awards: “Vlad Has Stories,”(2) Winter 2023; “The Cosmochemist’s Guide to the Galaxy” Spring 2023

2023 medal finalist: “A LIFE in Focus,” Spring 2022

2022 merit awards: “The Long Quiet,” Winter 2021; “International Reach,” Spring 2021; Spring 2021 cover

How to Write Your Mizzou Memoir

Teacher and memoirist Kelly Caldwell unloads her best tips and tricks for writing about a favorite episode from your campus years.

story by kelly caldwell, bj ’88

Thinking Inside the Box

What started as one mom’s hunt for the perfect keepsake case turned into a $10 million sensation — and caught the eyes of Shark Tank’s toughest investors.

story by mara reinstein, bj ’98

After two trips around the world, Kitty and Scott Kuhner came to understand that all they need is a boat, a heading and each other. Plus: Last year, a School of Engineering alum and his wife left their desks behind, working remotely while boat-schooling their son. stories by tony rehagen, bj ba ’01 and blaire leible garwitz, ma ’0₆

The Botanical Sound System

How plants transmit the secret songs of insects. story by eric stann * photos by abbie lankitus

A Diplomat’s Guide to Uncertainty

Ambassador David Young recalls life lessons from a career on the road — and during his years at Mizzou. story by randall roberts, ba ’88

With their alien-like ornamentation and secret tremors, treehoppers are masters of plant-borne communication. To research these signals, Mizzou biologist Rex Cocroft uses special sensors that turn the insects’ silent vibrations into audible sound.

Rice Country, USA

Missouri’s Bootheel was once a vast, untamed swamp. Now it powers an agricultural industry that feeds the nation.

story by nina mukerjee furstenau, bj ’84

Abdulmateen Adebiyi, a doctoral student in computer science, develops machine learning tools to help doctors diagnose skin conditions more accurately. His research could expand access to quality health care for patients in rural areas.

What can a Mizzou engineering student passionate about revolutionizing health care achieve during his doctoral studies? For Abdulmateen Adebiyi, the answer is a growing list of accolades and breakthroughs. The fourth-year computer science PhD student has earned the respect of his peers and professors, co-authored multiple studies in top-tier journals, and clinched the prestigious Outstanding Achievement Award from Upsilon Pi Epsilon, the international honor society for computing disciplines.

Working under Associate Professor Praveen Rao in the Scalable Data Science Lab, Adebiyi explores engineering solutions to medical challenges.

“I enjoy collaborating with primary care physicians, nurse practitioners and oncologists,” he says.

This partnership applies machine learning via deep learning models to diagnosing skin lesions,

and the results are promising. Their research shows that combining images with textual descriptions of lesions produces more accurate diagnoses than images alone. Adebiyi hopes the work will help improve health care access and outcomes for patients in rural areas.

He credits much of his success to his mentors.

“In addition to supporting my research and studies, my advisor and committee members take an interest in my well-being and help me adjust to American culture,” says Adebiyi, who was raised in Nigeria and has been at Mizzou since 2021.

As the engineer looks ahead to completing his PhD within the next year, Adebiyi sees a bright future. “I’ll be able to walk into a research lab anywhere in the world and contribute to solutions,” he says.

— Jack Wax, BS Ed ’73, MS ’76, MA ’87

For 186 years, the University of Missouri has prepared leaders who make a difference. No one knows the power of a Mizzou education better than the 365,000 alumni worldwide. As we approach two centuries of excellence, we are proud to grow our legacy and drive even more impact for all we serve.

As I complete my 8th year as president of the University of Missouri, I’ve been reflecting on the many achievements that were made possible because of the leadership and support of the University of Missouri Board of Curators, faculty and staff, alumni, and elected leaders.

But we’re not ones to rest on our laurels. This semester, we celebrated the opening of transformational facilities, including phase one of the new Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory and the groundbreaking of the second phase of the building, which will be named in honor of Dr. Dan Brown. We are breaking ground on ambitious projects such as the Michael L. Parson Meat Science Education and Training Laboratory to support Missouri’s ag community. In addition, we’re making progress on the Memorial Stadium Centennial Project, which aims to open in time for the stadium’s 100th anniversary in fall 2026. Success is also measured in the lives we improve. That’s why we completed a critical expansion of our University of Missouri Research Reactor facility to enhance radioisotope production. To advance our impact even further, we signed an official agreement to launch a design studies phase for a new, even more powerful research reactor, NextGen MURR.

Mizzou is the only supplier of four important radioisotopes in the United States. One of them, Lutetium-177, is a key ingredient in Pluvicto, a prostate cancer treatment that was advertised during this year’s Super Bowl. NextGen MURR will build on our proven legacy and secure our leadership in nuclear medicine for generations.

These initiatives advance our campus and bring pride — and incredible value — to our state. Missouri taxpayers and students recognize our impact, and we’re anticipating another year of strong state support as well as a record number of applications for next semester. We know there’s even more we can achieve. That’s why we’re preparing an exciting new fundraising campaign to support our land-grant mission. I’m thrilled to share more with you soon, including ways to get involved and help build our incredible momentum.

Thank you for your dedication to our students and university. M-I-Z!

— MUN Y. CHOI, PHD President, University of Missouri

Mizzou has made substantial progress in recent years, advancing student success, research and economic growth. These achievements, as outlined by President Mun Y. Choi, demonstrate the university’s commitment to serving the state and its people.

$5 BILLION

Annual economic impact to Missouri — a 25-to-1 return on taxpayer investment

1.2 MILLION

Missourians reached through Extension programs focused on agriculture, rural health, economic development and education

$509 MILLION

Record-high R&D expenditures at Mizzou — up more than 74% since 2017

89%

Approval rating from informed Missouri residents who say they’re “better off” because of Mizzou

48%

Growth in Mizzou’s freshman enrollment since 2017

39%

Increase in state appropriations since 2020, following five straight years of gains

The University of Missouri Board of Curators voted to name the forthcoming meat sciences laboratory after former Missouri Gov. Mike Parson. The facility will be called The Michael L. Parson Meat Science Education and Training Laboratory.

“As a third-generation cattleman, I can think of few greater honors than to have my name on a stateof-the-art facility dedicated to teaching and training Missouri’s next generation of meat farmers,” Parson says. “I proudly supported the work of the University of Missouri to advance agriculture in our state during my tenure as governor.”

Parson signed budget bills in 2023 and 2024 allocating $35 million for the facility, part of broader investments he championed for higher education and agriculture.

“Governor Parson’s bold leadership and support to the University of Missouri System empowered our educational, research, outreach and workforce development missions,” Mizzou President Mun Choi says.

The laboratory will update and consolidate existing meat science facilities and expand lab space, classrooms and faculty offices. It will support workforce training, research and innovation in meat processing, enhancing the nationally recognized Mizzou College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources. Located near Mizzou’s food science and veterinary programs, the lab will provide a wellrounded educational experience.

As humans age, our cells are under constant attack. They endure DNA damage from ultraviolet rays, irradiation, toxins and other environmental factors. For women, this process decreases egg quality over time and can lead to infertility, miscarriage, birth defects or genetic disorders.

The body does have a defense mechanism: autophagy, which maintains cellular health by essentially recycling the body’s own components.

In a recent study published in Nature Communication and funded by the National Institutes of Health, a team led by Ahmed Balboula, assistant professor in the College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources and researcher at the Roy Blunt NextGen Precision Health building, discovered that in female eggs, autophagy is less efficient when there is already moderate or severe DNA damage, which is more common in older women. This increases the risk of aneuploidy, or an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell, which in turn is the leading genetic cause of miscarriage and congenital birth defects, including Down syndrome.

Fortunately, Balboula and team also discovered a possible solution: By stimulating the process of autophagy in female eggs, they improved egg quality and reduced DNA damage. Their findings open new directions for improving reproductive health for both humans and animals.

“The deactivation of autophagy that we found is likely just one of many underlying mechanisms contributing to aneuploidy,” Balboula says. “Going forward, I will continue to explore other underlying mechanisms contributing to poor egg quality.”

In the world of quantum physics at nanoscale, new phenomena are invisible to the naked eye and even most run-of-the-mill microscopes. But that doesn’t mean their implications are small.

Such is the case for a new quasiparticle discovered by Mizzou researchers Deepak Singh and Carsten Ullrich, along with a highly involved team of postdoctoral students including Jiasen Guo and Daniel Hill and collaborators at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Their discovery — funded in part by the U.S. Department of Energy — affects what physicists know about magnetism and may influence the future of energy and electronics.

Unlike fundamental particles such as electrons and photons, quasiparticles are not distinct entities on their own. Rather, they arise from the collective behavior of other particles. Ullrich offers an analogy: “A body of water is made up of many gazillions of water molecules. But at times they come together and form structures that are larger and have particular behavior — whirlpools and eddies, for example. We are interested in studying the properties of those larger structures that arise from the small molecules coming together and doing something collectively.”

The team surveyed the quasiparticle in multiple environments. “We observed exactly the same behavior, the same peculiar dynamics of this fast-moving quasiparticle,” Singh says. “It can be observed in any magnetic material. As long as it’s a very narrow constricted structure, this behavior can be detected.”

The next steps for this research are further observation and replication by the Mizzou team and, hopefully, other physicists. “If we can

Mizzou researchers have created an affordable, portable system to help identify mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a potential precursor to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. The system, which uses a depth camera to capture movement, a force plate to assess balance and an interface board to process data, analyzes subtle motor function differences linked to cognitive decline.

In a recent study, the device captured data from older adults performing simple movement tasks while counting backward. A machine-learning model then identified 83% of participants with MCI.

“The areas of the brain involved in cognitive impairment overlap with areas controlling motor function, so when one is diminished, the other is

Department of Physics and Astronomy researcher Deepak Singh, who studies magnetic quasiparticles at the nanoscale.

understand and control it, it does have potential for a field like spintronics,” Singh says, referring to an emerging alternative to electronics with the promise to drastically reduce power consumption for everything from high-level computing to the smartphones everyone carries in their pockets. “But first things first, we are physicists. We want to understand it.”

— Chris Blose, MA ’04

impacted as well,” Trent Guess, associate professor in the College of Health Sciences, told Show Me Mizzou.

With Alzheimer’s cases projected to double by 2060, researchers hope to expand the system’s use to clinics, senior centers and assisted living facilities for early intervention.

• Jonathan B. Murray, BJ ’77, has donated $10.3 million to the Missouri School of Journalism’s Jonathan B. Murray Center for Documentary Journalism to enhance educational opportunities and solidify Columbia as a Midwest hub for documentary storytelling. The gift will support new initiatives, including increased student mentorship, expanded professional partnerships and innovative documentary production opportunities.

• Sara Parker Pauley, JD ’93, has received The Pugsley Medal, a prestigious national award honoring leadership in natural resource management. Established in 1928, the award recognizes individuals who advance parks and environmental stewardship at local, state and national levels. Pauley, the first woman to lead both the Missouri Department of Conservation and the Missouri Department of Natural Resources, has enhanced outdoor access and guided key land acquisitions across the state.

• The University of Missouri Advanced Light Microscopy Core (ALMC) has a new director: Tara Finegan, assistant research professor in the Division of Biological Sciences. Finegan, who joined Mizzou’s faculty in 2023, brings expertise in light imaging technologies and will continue her academic and research duties while leading the ALMC.

Suchi Guha and Gavin King are exploring the extraordinary properties of halide perovskites at the nanoscale — dimensions typically less than 100 nanometers, where materials can exhibit unique physical and chemical behaviors. At this scale, the ultrathin crystalline structure of halide perovskites makes them highly efficient at converting sunlight into energy. The Mizzou physicists’ work could lead to more affordable and effective solar panels and longerlasting LED lights.

“Halide perovskites are being hailed as the semiconductors of the 21st century,” says Guha, an expert in solid-state physics. “Over the past six years, my lab has concentrated on optimizing these materials as a sustainable source for the next generation of optoelectronic devices.”

A class of minerals with a distinctive cubic structure, perovskites have gained attention for their exceptional electronic and optical properties. To fabricate the material, Guha’s team used chemical vapor deposition, a scalable method refined by former Mizzou graduate student Randy Burns, PhD ’24, in collaboration with

Chris Arendse of the University of the Western Cape. The team analyzed the material’s optical properties using ultrafast laser spectroscopy before collaborating with King to enhance its electronic applications.

The scientist, who specializes in biological physics, applied ice lithography, an advanced technique that cools the material to cryogenic temperatures and allows for precise patterning at the nanometer scale.

“By creating intricate patterns on these thin films, we can produce devices with distinct properties and functionalities,” King says. “These patterns are the equivalent to developing the base or foundational layer in optical electronics.”

The researchers credit their interdisciplinary approach for the project’s success.

“When you collaborate, you get the full picture and the chance to learn new things,” Guha says.

Their work is part of Mizzou’s growing research portfolio powering the new Center for Energy Innovation. The team’s findings were published in the Journal of Materials Chemistry C and Small.

— Chris Blose, MA

’04

Ready to help, Mizzou’s new AI-powered texting tool connects undergraduates to the people and resources they need to thrive. Roary navigates university policies, places, programs and people, and links students to the support they need — whether that means improving academic skills, joining campus groups or finding dining options.

“Mizzou is a big, complicated place, and Roary is like a GPS that helps students navigate their campus experience,” says Jim Spain, vice provost for undergraduate studies. Launched this semester, Roary already has answered more than 30,000 texts from students. Students can access it 24/7, and each week, it proactively checks in with messages tied to the academic calendar. Roary’s knowledge continues growing, but its mission remains the same: “Roary is all about helping students succeed,” Spain says. — Jack Wax, BS Ed ’73, MS ’76, MA ’87

@NFL

Mizzou Tiger Armand

Membou’s roaring 4.91u at 6’4” 332 lbs!

: #NFLCombine on @NFLNetwork

@BioNexusKC

At BioNexus KC, we believe in the power of partnership. Thank you, @Mizzou & @MizzouResearch, for being a champion of innovation and discovery in the life sciences. Your dedication to research are making a lasting impact on our region's scientific and healthcare landscape.

@MizFanJoe

Mizzou sports are boomin’. Back to back 10+ win football seasons, finishing ranked in AP/ CFP polls, entering next season with arguably the top transfer class. Basketball has wins over the #1 and #5 teams in the nation. Entered the poll at #22 this week. 15-3 and ROLLING.

@CoachDrinkwitz

MIZZOU STUDENT

SECTION NEVER DISAPPOINTS!! #MIZ

@Mizzou

Yesterday, #Mizzou leaders hosted a ribbon cutting celebrating a 47,000-square-foot addition to the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR) facility. The addition offers new opportunities for industry collaboration and advances in nuclear science.

As an undergraduate in the School of Health Professions in 2011, Scott Meyer needed a fieldwork requirement to complete his degree. At the bottom of a list of possible internships, he saw an opportunity with Mizzou’s wheelchair basketball team. Meyer, who played basketball through high school, figured he’d compile stats and film games for a year before moving on.

Instead, wheelchair basketball became his future. On Feb. 25, 2025, Meyer, BHS ’12, was named head coach of the U.S. men’s wheelchair basketball national team. He will lead Team USA through a four-year cycle culminating in the 2028 Paralympic Games in Los Angeles.

“Like a lot of people, I had no visibility into adapted sports growing up,” Meyer says. “Initially, I thought, ‘How can people play basketball sitting down?’ But then you see it and see how fast people go, hear the contact of the chairs, see people falling over and popping back up, being able to shoot sitting down from pretty much anywhere on the court. I fell in love with it.”

Mizzou is one of only 12 U.S. colleges to offer wheelchair basketball. Thanks to longtime coach Ron Lykins, the school has strong ties to the international game. As head coach of U.S. national

teams, Lykins won four Paralympic gold medals: two each for the women (2004, 2008) and men (2016, 2021).

“He’s the best to ever do it,” Meyer says of his mentor. “To be able to learn from him, it was like a third master’s degree for me.”

Lykins saw in Meyer an eager student with a strong basketball background who built trust with players and taught the game well. Post-graduation, he invited Meyer to stay as a Mizzou assistant coach and chose him for his Paralympic staffs. After winning gold in Tokyo in 2021, Lykins stepped down. Robb Taylor then led Team USA to a third straight gold in Paris, with Meyer assisting.

Now, as head coach, Meyer moves from making suggestions to making decisions, the easiest of which was inviting Lykins to be his assistant coach. They’ll be side by side again for a run they hope ends with a fourth straight Paralympic gold for Team USA.

“To see him grow and get this opportunity is well-deserved, and I’m really happy for him,” Lykins says. “He doesn’t need me — he’s good on his own — but for me to be there and offer advice when he needs it, it’s just payback for all he did for me.” — Joe Walljasper, BJ ’92

New U.S. wheelchair basketball coach Scott Meyer, right, stands with his mentor Ron Lykins. Both are longtime Mizzou coaches and pioneers in Paralympic wheelchair basketball.

Mizzou has named Kellie Harper as the new head coach of its women’s basketball program. Harper becomes the fifth head coach in program history and brings more than two decades of head coaching experience, nine NCAA Tournament appearances and a 393-260 overall record to Mizzou.

She replaced Robin Pingeton, who led the Tigers for 15 seasons and guided the team to four NCAA Tournament appearances.

Harper, who most recently served as head coach at Tennessee, returns to the sideline after spending the 2024–25 season as an analyst with the SEC Network. A former national champion as a player at Tennessee, she also led Missouri State to two NCAA appearances during a successful six-year run in Springfield. At Tennessee, she guided the Lady Vols to multiple 25-win seasons and three Sweet 16 appearances.

“I am incredibly honored to be the next head coach at Mizzou,” Harper said of her new job. “Missouri is a special place, and I know firsthand the passion and pride that surrounds this program. The foundation is in place for success — and I can’t wait to get started.”

SOPHIE’S TRADE All-time Mizzou women’s basketball leading scorer Sophie Cunningham, BS ’20, will play alongside WNBA superstar Caitlin Clark after being traded to the Indiana Fever in February. Cunningham spent six seasons with the Phoenix Mercury, averaging a career-best 12.6 points and 4.4 rebounds per game in 2024. The 2025 WNBA regular season begins Friday, May 16.

Brock Olivo’s playing days at Mizzou are three decades past, back in the era of gigantic shoulder pads. Even then, the Tiger running back seemed like a throwback. He lived in spartan quarters, forsook fatty and frothy pleasures and pushed himself to legendary lengths in the weight room.

Those sacrifices transformed a lightly regarded recruit into a star back and special teams player. Olivo, BA ’01, was a firm believer in the notion that anything was possible in football if you outworked the other guy. As a senior in 1997, he and the Tigers earned their first winning season in 13 years.

The game has changed dramatically since then, and not at all.

“Football, I call it the great revealer,” says Olivo, who has served as Mizzou football’s special teams assistant since 2023. “There’s a lot of pomp and circumstance around college football, but on Saturday afternoons, you have to prove it. I don’t care how much NIL or revenue sharing you’re getting directly deposited into your bank account each month.”

Although the coach is a romantic about football, he says sharing his real-world experience has the most impact on Mizzou players. After four seasons as a player with the Detroit Lions, Olivo transitioned into coaching. He worked with the Chiefs, Broncos and Bears before returning to his alma mater.

“I’ve been in their shoes here,” he says. “I can give them perspective on what it takes as a player and what coaches look for at the next level.”

— Joe Walljasper, BJ ’92

When Abby Hay finally decided to switch from baseball to softball as a freshman at Rock Bridge High School in Columbia, she had some adjustments to make. She needed to learn how to hit riseballs, how to stay put on the basepaths until the pitcher released the ball and, perhaps most jarring, how to sing cheerful chants in the dugout.

“In baseball, it’s more ruthless. You’re trying to get under the other team’s skin,” Hay says. “The cheering is still not my favorite. I like to heckle sometimes. I have to control that a little bit.”

Hay has otherwise adapted just fine. As a freshman first baseman at Mizzou in 2024, she hit .282, earned second-team All-Southeastern Conference honors and helped the Tigers come within a game of the College World Series.

That Hay became a Mizzou athlete seemed natural. Her parents are both former Tigers: baseball player John Hay, BS BA ’92, and golfer Amy Smethers Hay, BS ’95. That Abby wound up playing softball, though, was no sure thing.

Her dad’s sport was her first love. She started by trying to keep up with her brother, Zack, who is four years older, and his friends in backyard games.

“I was the kid that would watch games and then go out in the yard and imitate the swings or the way they fielded ground balls to get the movements down,” Abby says.

John helped coach Abby’s baseball teams. She says he was always a little harder on her than the other players. He would tell her to shake off the occasional foul tip to the throat when she played catcher. Her parents never tried to steer her away from baseball.

“Who am I to tell her she can’t do something?” Amy says. “Why would I be the one that says no and defines what she can’t do?”

Abby decided to join some of her friends on the Rock Bridge softball team as a freshman. She continued to play baseball through her sophomore season before turning to softball full time for her final two years of high school. After Mizzou offered her a scholarship, the decision was easy.

“We’ve raised our kids at Mizzou football games and basketball games, and we’re just Tigers through and through,” Amy says. “The fact she wanted to stay here, it makes my heart swell.”

— Joe Walljasper, BJ ’92

2 — Number of Missouri wrestlers who earned All-America honors at the NCAA Championships. Keegan O’Toole placed second at 174 pounds, and Cam Steed finished seventh at 165. As a team, the Tigers placed 14th.

4.0 — GPA of women’s basketball player Grace Slaughter, who was named the Southeastern Conference Scholar-Athlete of the Year.

197.650 — Program-best postseason score posted by Mizzou gymnastics at the NCAA Seattle Regional, where the Tigers advanced to the regional final. The performance featured a perfect 10 on beam from Helen Hu — the first in program history — and helped earn five gymnasts All-America honors, including Hu and Mara Titarsolej on the first team. (See Semper Mizzou, Page 64.)

7:53.61 — School-record time posted by Drew Rogers in the 3,000 meters at the SEC Indoor Championships. The win made him the first Mizzou man to claim gold in the event and the first to break the 8-minute barrier in school history.

17.04 — Length in meters of Jonathan Seremes’ triple jump, which earned him a gold medal at the NCAA Indoor Track & Field Championships. That leap — 55 feet, 11 inches — made the sophomore from Paris, France, the first triple jump national champion in Mizzou history.

Warm football Saturdays. Wandering the stacks at Ellis. A bronze tiger statue. A menu featuring chickenfried steak. Something puts that faraway look in your eyes and unleashes your best stories — and it need not trigger an urgent need in your spouse or kids to check their phones. You can hold their attention while reliving your best moments. In fact, you should. Because looking back is just another way of moving forward, and your audience will feel the same acceleration. Read on as teacher and memoirist Kelly Caldwell unloads her best tips and tricks for composing a favorite episode from your campus years.

SIDE BY SIDE in the smallest apartment in Columbia, Sherry and I taught each other how to fry bacon.

We were sharing a studio on Rosemary Lane that we’d nicknamed “The Closet.” It could fit one single bed, so we took turns sleeping on the floor. We had a kitchen chair, too, but it went into the hallway when both of us were home at the same time.

It felt like living inside an oil can, and that summer, Columbia suffered a record-breaking heatwave. I spent my last dollar on a used window air conditioner and stored it overnight with a boyfriend. He sold it.

He was why Sherry was there with me, clogging her pores in The Closet at midnight when she should have been in a cool movie theater with a date of her own. After an argument with the air conditioner thief, I’d called her in tears at work; she came home instead.

She should have called me a putz like she did whenever I slept through our 8:40 a.m. Econ 51 class and needed to borrow her notes. She should have banned me from hanging out, eating Oreos and gossiping at her second job at the Brady Commons

commissary until I’d broken up with the air-conditioner thief. She should have told her co-worker to take a message. Instead, Sherry held my hand until I calmed down. Then she stood up, stuck the chair out in the hall and proclaimed, “I’m starved! Aren’t you starved?”

Of the countless nights I’ve stayed up too late eating fried foods with friends, this one stands out. I could joke that it’s memorable because of the Missouri summer heat, my almost nonexistent cooking skills or my questionable diet.

But that would be glib and unsatisfying. And it wouldn’t be true in the deepest sense. As a writer and teacher of memoir, it just won’t do.

That’s because in memoir, we excavate and share our memories not just to entertain friends or bathe in the balmy breezes of nostalgia. We also examine them in the hopes of unearthing deeper truths about what it means to be human.

Our college years — when our prefrontal cortexes are in the final stages of development, when we’re gulping down knowledge like thirsty hippos drinking water, and when

we’re experiencing more big firsts than we can count — are especially rife with memories begging to become meaningful stories. They’re also likely to bubble up to the surface with the slightest provocation: the mere existence of a football Saturday, the smooth spine of an old book, the tang of pizza sauce.

Once they’re unlocked, though, then what?

First, write them down before they have a chance to skitter off and get lost forever. Writing them down also may summon other memories you can preserve. Before you know it, you’ll have a notebook full of stories you didn’t even know you remembered.

If you’d like to take it further, to craft those stories into memoir and discover why they’re meaningful to you, read on.

HOW OFTEN HAVE YOU heard someone say, “Someday, I’m going to write my memoirs, and then everybody better watch out!”? What they really mean is, “Wait till I write my autobiography and exact revenge upon all those who have wronged me.”

As fun as it might seem to write a vengeance-inspired hit job, a memoir is a story written for other people. It’s also one story of your life, not the story of your life. That’s autobiography, which is mostly reserved for the super famous (or infamous): politicians, inventors, performers. Think of last year’s Lovely One by Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson or the much-anticipated life story forthcoming from pop star Lionel Ritchie. Their successes are the destination; all that remains is to answer the question, “How did I get here?”

There’s no preset destination for the rest of us; any moment in our lives that feels urgent and memorable to us can be the focus of a good memoir. Everyone’s life is full of potential meaning— no fame required.

But we have to narrow and narrow and narrow the focus of our story. You don’t want to tell the whole story of living in your sorority or choosing your major or courting your spouse. You want to single out one moment that sings to you and write it down. Where was it? What music was playing? When did it happen? Who said what? Repeat for the next moment. And then the next.

You wouldn’t throw flour, sugar, butter and cherries into a blender, dump them into a pan and bake them, and expect them to turn into a pie. The same goes for memoir. You create each layer individually, then knead them together into a whole.

OFTEN THE MOMENTS that sing to you are when something disrupted the status quo of your life. Spring comes too early, prompting two best friends to commit to bottling a record amount of maple syrup. A tornado rips through your community. You land the lead role in the campus production of Angels in America

But great memoirs can start with a change that’s so small it wouldn’t be remarkable, except that it led to something more meaningful. You start going to the pizza place for lunch every Tuesday instead of every Wednesday and develop a friendship, ultimately an important one, with another regular customer. You attend the same St. Patrick’s Day party every year, but one year you wake up the next morning with a hangover, a wad of cash you didn’t have before and no memory of how you got it. (This sounds like the beginning of a thriller, but it happened to my grandfather.)

There’s meaning in the mundane. A friend’s father used to order a chocolate cake to be delivered to their home every Saturday morning. Sweet routine, right? Maybe not much more than that — until you learn that he grew up as one of nine hungry children and spent most of his childhood scrounging food for his younger siblings. Even then, with that crucial detail, it still isn’t a story. It becomes a story when the bakery van breaks down, or the mother gives the cake away to a neighbor’s family, or the dog eats it. Because then you have to answer the question, “What then?”

In her memoir Eastern Circle, forthcoming next year from Holt publishing, Catina Bacote describes how her grandfather looked out for the Connecticut community she grew up in. He scared off stray dogs and bullies, broke up fights and somehow materialized whenever anyone needed help. Again, it’s lovely but mundane. It becomes meaningful when we learn that “Dada” died protecting his community. He was shot to death defending teenage neighbors under attack by strangers.

Now it’s a story, albeit one that needs a focus. Bacote finds

that when she discovers a monument overlooking the neighborhood that honors long-dead soldiers who fought in long-ago wars. She argues a similar monument should be built to honor her grandfather and the thousands like him killed in violence during the crack epidemic of the 1980s. You can see that idea in the subtitle for Bacote’s book: Searching for a Just End for My Grandfather’s Murder.

Now, it’s a story.

SOMETIMES, YOU CAN describe an important memory to the point of exhaustion — capturing every word spoken, the slant of the sunlight, the smell of lunch bubbling over on the stove — and still, you have a memory, not a memoir. What’s missing is the action within yourself.

“Interiority moves us through the magic realms of time and truth, hope and fantasy, memory, feelings, ideas, worries,” Mary Karr writes in Art of Memoir. “Whenever a writer gets reflective … she moves inside herself to where things matter and mean.”

You’re looking for something more nuanced and granular than, “We broke up, and I felt sad.” Events trigger internal responses, and those responses shape us: our actions, our dreams, our fears, our hopes. The stuff meaning is made of.

How many times have you walked Mizzou’s Quad on a Homecoming weekend past crowds of alumni of all ages, staring at the Columns with misty eyes? You might assume they’re all feeling the same wistfulness and nostalgia. You’d also be mistaken.

Sure, some may be ruminating generally on the past because the Columns represent the whole Mizzou campus, all the places where they did some of their most important growing up. But others may be reliving meeting their best friend in Switzler Hall or breaking up with their first love in front of the chancellor’s residence or registering for classes in Jesse Hall after overcoming enormous adversity to be able to attend college at all.

They may all be united in their nostalgia, but not all nostalgias are the same. They can be a longing for one’s past, or a yearning to reconnect with something forgotten. Humans can feel nostalgia for the future, or for a past that never existed.

My favorite description, though, is from the novelist Michael Chabon. “It’s the feeling that overcomes you when some minor vanished beauty of the world is momentarily restored,” Chabon wrote in an essay on nostalgia for The New Yorker. “In that moment, you are connected; you have placed a phone call directly into the past and heard an answering voice.”

line to the past. In that way, they’re connected to each other.

That connection, too, is the strain of nostalgia that’s most useful to us in our quest to turn our memories into stories, because despite its bad reputation as a sappy time-waster, nostalgia can be an effective tool. Not only does it churn up memories and emotions — also known as material — it is useful in other ways. It prompts us to reach out to others (research), it opens conversations on long-forgotten or long avoided subjects (discovery) and it fosters empathy (just a good thing generally).

diving into the crowded madhouse of your memory, grasping one moment from the many, and then trying to study it while it bucks and flips. But you already have practice at this. Think of all the times you’ve been at a party and pulled out an anecdote to share, changing it slightly depending on your audience. Leaving out the NC-17 parts when your boss is there, opening with the NC-17 parts on a bachelorette weekend. That’s memoir.

It’s also an opportunity to visit places and eras that no longer exist, with people (including your younger self) who no longer exist — except within you. It’s a chance to return with a gift better than any snow globe: a story that helps you understand yourself better and maybe helps others understand themselves better, too.

Take that night frying bacon with Sherry in The Closet. For years I thought of it as a story about heartbreak or about navigating romantic relationships or maybe about cooking. Only when I wrote it as a memoir did I finally understand: That sweltering summer, Sherry showed me what it takes to be a real friend. It’s listening even when you want to shake someone by her shoulders and tell her to snap out of it. It’s sacrificing a night at the movies because someone you love needs you. It’s showing up, even when it’ll be uncomfortable.

Memoir is one story of your life, not the story of your life. That’s autobiography, and it’s mostly reserved for the super famous (or infamous).

All those misty-eyed alums on the Quad might not be listening to the same voice, but I like to think they’re sharing a party

Like stepping onto campus as a freshman, you never know what you’ll find when you wander into your memories and look for the stories they hold. And like the adventure you embarked on then (and the adventures since), you navigate by reaching for what seems promising and see which ones lead you home.

For an example of a short memoir, take a look at the following story about Read Hall, with a few tips and tricks in the margins. Then try to write a memoir of your own. Think of a moment from your time at Mizzou that’s calling out to you. See how much of it you can remember. Ask yourself why it’s singing to you. See what answer floats in through the open window. M

One place, one time, one story. This moment orients the reader to where I am in my life revealing important facts for this story.

I WAS 19, SELF-CONSCIOUS, as quick to mortification as some drivers are to road rage, so, really, the incident should have killed me.

On an 80-degree day in mid-April, another reporter walked into the office wearing a jacket and heavy blue wool sweater.

“Take that sweater off!” I said. “You’re making me hot just looking at you!”

The room erupted into a middle school, “OhhhhhhOOHHHHoooohhhhhhhhhhh!!!” The next thing I knew, someone dragged over a chair. An upperclassman named Fred grabbed a fat black Magic Marker and started inscribing my words high onto the walls of Read Hall.

It was one of the proudest moments of my life.

You had to earn your way onto the wall, which made the memory, well, memorable.

For at least 15 years in the ’70s and ’80s, the Maneater third floor of Read were legendary for the graffiti covering every inch of the greenish-gray walls. Ceilings, too. It was of varying vintages, some so faded you could barely read them, and the handwriting fluctuated in its legibility, too. There were a few drawings, but mostly, it was text. You couldn’t make the wall with something so generic as your initials or “Kilroy was here” or earned your way onto the wall with bits of threats, jokes, insults and assorted weird nonsense muttered at 4 a.m

“I’ve got a lot of patience. And that’s a lot of patience to lose.”

Be specific about the place and time. Not just “in Read Hall” but the ’eater office on the third floor of Read Hall.

“The Digest is turning into a good paper.” (No doubt that was a sick burn when Eric said it in 1979, but I never figured out whether the burnee was

Examples make the mundane more vivid.

“You have to choose someday whether you’re going to be a journalist or a .” Underneath, someone replied, “Man, I hope you have a good

It wasn’t Basquiat. But it was ours.

This is the reality of life at the ’eater — what it would take to be immmortalized on the walls.

Story begins when everything changes.

it would be gone. At the end of that school year, the university Maneater out of Read Hall and move us into bigger, cleaner, more modern quarters in Brady Commons, where we’d be able to produce the paper with actual computers instead of the manual typewriters and rub ber cement we’d been using since the Wilson administration.

We lobbied hard to stay, but the administration rejected all our appeals. To the university, I suppose, one set of rooms was as good as another for the scruffy loudmouths who published the student newspaper. No doubt they thought we were being overly sentimental.

Why should you care about place attachment? Because you have it, too!

It was so much deeper than that.

What we had is called place attachment bond with a space where you’ve had intense personal experiences. It can develop because of the nature of the experience or because it took place in a community or because the place itself is special. Sometimes it’s all three.

Memoir is of necessity built mostly from our memories. But speculation and imagination are good, too.

You want to recreate not only the physical setting of your story but the emotional setting, as well. And if it finds common ground with your reader — like 20-somethings figuring out who they will be when they grow up — all the better.

Think of all the classes you remember? Maybe those skinny windows were on the left side of your Spanish classroom and the right side of your algebra classroom. Or was it the other way around? Does it matter? an earthquake hit the Francis Quadrangle. Two Columns lay on their sides, split in half. The other four are nothing but dusty chunks. That sensation you’re having right now of being place attachment.

Find meaning in your personal story, connecting it to larger subjects outside of your own experience — current events, social issues, history, etc.

Sure, Read Hall was special to us because it’s where we met our closest friends, saw our first byline, suffered heartbreaks, celebrated victories. It’s story of

Those pivotal, life-changing moments happened to us elsewhere on campus, too, on Lowry Mall or in Middlebush Hall. But our affinity for those spaces was never quite so fierce as our attachment to Read.

The difference is the graffiti.

We liked its audacity, this open, gleeful defacing of university property. It appealed to our desire to be perceived as rebellious, independent, willing to speak truth to power.

Memoir isn’t just recounting what happened. It’s shaping a story for other people. Seize opportunities to connect with readers on shared experiences.

Don’t be afraid to break your readers’ heart.

Private agonies read deeper than external whammies. Also good? Secret longing and aspiration.

First-person stories always risk sound ing self-indulgent, so be sure to an ticipate the reader asking, “So what?” Possibly with an eye roll. “Great, you kids defaced the walls of your offices and thought you were soooo cool. And I should care about this because ... ?”

It also gave us a sense of legacy: Every scribble connected us to aspiring journalists who became the real thing. We sat where they sat and hoped to follow their bad puns into careers of our own.

But most importantly for creating that cognitiveemotional attachment, the graffiti changed the physical space. Nowhere else on campus looked like the Maneater offices, and that made them indelible. It made events within those walls more vivid, special. We read it, preserved it, shared it, added to it. Hell, we curated it.

I saved this background for this moment in the story so it will show why the place was so important to me. Any earlier and I’m just one of 5,000+ overwhelmed freshmen.

It’s why my “Take that sweater off!” moment was so joyful. In the fall, it taken me a full month to work up the nerve to attend my first Maneater news meeting. By then, the campus had stopped seeming so overwhelmingly huge, and I’d met the woman who would become my best friend. I’d attended enough home football games to say hi to the students who sat in my section.

But as a shy kid eight hours from home, I fully a part of university life. Mizzou still did not belong to me. Not yet.

That feeling started to fade after I finally dragged myself into Read Hall and one of the editors read out the last story to be assigned. “You there,” he said, pointing at me in the back of the room. “What’s your name? This one’s yours.”

And here is where the interior story ends.

Each action in a story triggers a reaction; this is the ripple effect of the move out of Read Hall.

Now, I was being immortalized for saying fellow writers were teasing me with, “What else would you like him to take off, Kelly?” and “Is there anyone else you’d like to see strip, Kelly?” Now, just like Patient Laura or Eric ’79, I’d made the wall.

That one was mine

As the school year wound down and the move loomed, we were in genuine mourning. Some ’eaters declared they’d never set foot in the offices in Brady Commons, and they kept their word. Others tried but soon drifted away. It wasn’t the same. As promised, the space was clean and modern and sterile

Those of us who continued

This is the beginning of my interior story.

Memoir doesn’t feel authentic unless you are honest about moments when you messed up or said something stupid.

Students started making memories at Brady Commons in 1961, clockwise from above: Grabbing a bite at the food court, 1994; navigating a tumble of texts at the bookstore, 1976; and registering for classes, undated photo.

bring our place attachment along with us.

After the Maneater’s move, a rumor around that before construction workers took sledgehammers to the walls, tearing them down to the studs and rebuilding them, a couple of editors tried to chisel out hunks, to save some of the quotes. The plaster crumbled in their hands.

Don’t say something is true when you know (or are pretty sure) it’s not. But as long as you’re clear with the reader, rumors, myths and legends are all fair game.

One place, one time, one story means you can only choose one idea to leave the reader with at the end. Here, I hope the reader leaves feeling like they time trav eled to that spring, hung out for a bit with a lively group of spirited young writers in a funky, sacred space — be cause that’s how it felt to me.

Age, cigarette smoke, neglect — there were plenty of sound, logical reasons why we couldn’t take those pieces of Read Hall with us.

For me, though, it’s more likely that the graffiti was an artifact, ancient and enchantoutside its temple. M

Kelly Caldwell, BJ ’88, who has published Newsday and teaches memoir and leads the faculty at Gotham Writers Workshop in New York City.

What started as one mom’s hunt for the perfect keepsake case turned into a $10 million sensation — and caught the eyes of Shark Tank’s toughest investors.

by mara reinstein,

bj ’98

INDSAY MULLENGER turned a personalized trunk into a multimillion-dollar business.

Mullenger, BS BA ’10, founded Petite Keep, an online retailer specializing in custom-made, hand-crafted chests to store sentimental mementos from weddings, births and other major milestones. In more than 5 years, she’s grown her startup from a buzzy social media curiosity to a $10 million-a-year powerhouse.

Mullenger also has lured in some big fish along the way. On January 24, she appeared on ABC’s Shark Tank and secured a rare threeperson investment from Mark Cuban, Barbara Corcoran and Jamie Kern Lima.

“I am obsessed about the business,” Mullenger says from her home in suburban St. Louis. “I feel so strongly about what we’re doing and the pure joy that we’re bringing to people’s celebrations. We’re a part of the highest moments of their lives, and

that’s so fun.” The married mother of five adds that the company “is my sixth baby.”

In 2018, pregnant with her second daughter, Mullenger struggled to find a personalized keepsake box. “I talked to my friends across the country, and no one had a great solution,” she says.

The entrepreneurship skills she honed at Mizzou’s Robert J. Trulaske, Sr. College of Business kicked in. Despite working full time at Procter & Gamble with little product development experience, she poured her energy into Petite Keep. “It was like a Rubik’s Cube trying to figure everything out,” she says. “I listened to a lot of business podcasts and did a lot of Googling.” She also happened to launch at the start of the pandemic in early 2020. She benefited from customers craving new at-home to-dos that led them to discover her colorful trunks on Instagram.

In those early days, Mullenger and her husband set up shop in the attic and worked nights

and weekends. She got help from her parents: Her mother, Dotti (Heiman) Durbin, BS HES ’82, wrote every gift card, while her father, Mike Durbin, BA ’82, handled packing and shipping.

“It was a very bare-bones endeavor before it grew,” Dotti says. In just one year, the company produced six figures in revenue.

Mullenger first applied for Shark Tank a few years ago and waited it out until she got the call. She taped last September. “I was really nervous, but I realized that this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” she says. A confidentiality agreement precludes her from sharing details, but viewers surely made note of her moxie. She negotiated for 15% of her company in exchange for $400,000 — and she made an enthusiastic plug for her education at Mizzou. “I’m so happy it wasn’t edited out!” she says. While at Trulaske, Mullenger was accepted into the Cornell Leadership Program and

attended its first Tigers on Wall Street corporate trip in 2008. “It was an incredible experience because I saw a window to the world,” she says. The program also “had an emphasis on leadership, which I have definitely taken with me.”

She currently runs Petite Keep out of a warehouse in St. Louis. Teams across the country take on the fabric and sewing responsibilities. With her parents no longer serving as makeshift employees, they can marvel at her accomplishments. “We always had confidence in her,” Mike Durbin says, “and knew that whatever she did, she was going to make it a major success.”

Indeed, Mullenger encourages aspiring entrepreneurs to go for it. “A lot of people told me that it was crazy to start a business when I was building a family and had a steady career,” she says, “But there’s never going to be a better time than right now.” M

After two trips around the world, Kitty and Scott Kuhner came to understand that all they need is a boat, a heading and each other.

STORY BY TONY REHAGEN, BA, BJ ’01

MIZZOU MAGAZINE SPRING 2025

SCOTT AND KITTY KUHNER were working in New York City when Scott popped the question: “Will you sail around the world with me?”

Saying “yes” arguably wasn’t even the most impulsive thing Kitty had done that year. She had already met and agreed to marry Scott in the span of six weeks that spring. Still, in many ways, an ocean voyage around the globe in a sailboat was a bigger ask than “Till death do us part.”

Scott was a New Englander who’d taken sailing lessons since age 13. Kitty Heaton, BS Ed ’66, was a Midwesterner raised in Ladue, Mo. “Not many people in Missouri sailed,” Kitty says. “I’d never heard of anyone sailing around the world.”

On the other hand, Kitty had relished the couple’s honeymoon sailing from Westport, Conn., to Nantucket, Mass., and back. She loved living in the cramped quarters and “taking our home wherever we went.” Plus, she was an adventurer at heart. “I read a book written by an older couple from England that had sailed around the world,” Kitty says. “I thought, ‘If they could do it in their 40s, we could do it in our 20s.’”

Two years later, the Kuhners hopped aboard their ketch and embarked on a 32,000-mile journey across three oceans and five continents. They witnessed natural wonders, experienced foreign cultures and met fascinating people along the way. They also struggled to avert disasters in the form of hurricanes, pirates and medical emergencies. In many ways, the experience shaped them into who they became as individuals and as a family. “Every place we anchored, we made friends and had fun,” Kitty says. “Even though we’d faced the storm, there were so many good things. We wouldn’t have traded it for anything.”

AS THE KUHNERS WERE, they didn’t set sail into the unknown on a whim. They spent more than a year preparing. First, Scott upgraded

Kathleen “Kitty” Heaton, from the 1965 Savitar yearbook

from his 23-foot O’Day Tempest to a 30-foot Allied Seawind, which they bought for $7,000 and named Bebinka, a Russian-inspired term of endearment for “little baby.” After refitting it with a diesel engine, a 30-gallon water tank and a spray dodger to shield them from sun, rain and surf, they installed a wind vane self-steering device to keep the boat pointed in the right direction relative to shifts in the wind. They both studied on a borrowed sextant, an essential sailing device. “We didn’t have a GPS or even a depth-finder,” Kitty says. “All we had was celestial navigation. We went to the planetarium to practice.”

On October 17, 1971, after quitting their jobs — his as a securities analyst, hers as a teacher — the Kuhners set off from Westport, Conn., to the Virgin Islands. Within two weeks, they encountered 40- knot winds, a Coast Guard helicopter asking if they needed assistance in the storm (they didn’t) and a leak in the onboard sink. The couple sang and danced in St. Thomas. Scott caught dysentery in Panama before they passed through the canal. They encountered a pod of whales en route to the Galapagos Islands and went 22 days without seeing another soul as they crossed the open sea. Then the Kuhners skipped across South Pacific islands, including Tahiti, Bora Bora and Fiji. They combed the beaches for seashells, rode out Hurricane Bebe (with Bebinka moored to some mangroves) and welcomed guitar-toting

Scenes from Kitty and Scott Kuhner’s first sailing adven- ture: navigating open seas in their 30-foot ketch, baking bread in a pressure cooker, cutting hair on deck, working office jobs in Sydney, renting motorcycles in Bali, sharing a guidebook with local kids at a temple and anchoring off the cliffs of Nuka Hiva.

Polynesians aboard to sing and dance into the night. They hitchhiked around New Zealand and paused for a couple of months to take jobs in Sydney, Australia. He was a financial analyst, she a secretary. Then to New Guinea and Indonesia. They crossed the Indian Ocean to skirt Madagascar and stopped in South Africa for a safari. They climbed the 699-step Jacob’s Ladder in St. Helena before crossing the Atlantic to Antigua.

“In the last 500 miles between Bermuda and Cape Hatteras, we got caught in a hurricane — but we didn’t know it was a hurricane,” Scott says. “We fell off this giant wave, blew the main hatch, bent the boom and scooped up water as we right- ed. I tell friends we were lucky enough to have the most efficient bilge pump in the world: a fright- ened woman with a bucket.”

After almost three years away, they returned to the workaday world. They lived in New York for a few years, where Scott worked on Wall Street and Kitty toiled in an art gallery. They bought a house and had two boys, Alex and Spencer. But it wasn’t long before the Kuhners again looked to the horizon. “We were spending a lot of summers and weekends on the boat anyway,” Scott says, “and as the boys grew up, they took on more responsibility on board. They loved sailing.”

“We wanted to show the kids there was more to the world than Fairfield County, Connecticut,” Kitty adds.

THREE YEARS, six months, 20 days and 30,347 miles after the Kuhners left Connecticut for the Virgin Islands, they returned home from their second trip around the world. The boys, now both teenagers, returned to school. They went on to private colleges and successful careers. Scott eventually went to work running the New York office of a Brazilian investment bank, and Kitty worked part-time until the kids got out of school.

In all, the couple spent $3,000 a year ($23,037 in today’s dollars) during their first round-trip and $18,000 per year ($49,278) on the second ring around the globe some 16 years later. “People assume you’re rich if you sail around the world,” says Kitty. “But no one’s living ashore. We had all we needed on the boat.”

“We wanted to show the kids there was more to the world than Fairfield County, Connecticut.”

In 2005, Scott and Kitty, both retired, sailed to the Azores, an archipelago in the North Atlantic, and wintered in Portugal, where they spent two years before sailing home. It was their last great adventure at sea. “We have body part malfunctions that keep us from using the boat,” Kitty says.

In fact, the couple is now preparing to move into an independent living senior center. The hardest part, Kitty says, is deciding which of the many paintings, sculptures, wood carvings and other mementos they collected during their travels will fit into their new quarters.

But what they don’t have to downsize are the hundreds of photos — sunrises igniting empty horizons, storm clouds swallowing the sky and strangers turning into friends in harbors around the world. Each image opens a portal, a reminder that, for a time, the sea was home. M

They upgraded their boat to the bigger Tamure (a hula-like Tahitian dance) and arranged for the boys, ages 9 and 11, to be home-schooled by Kitty onboard. After renting their home out in October 1987, the family began a trip around the globe, starting with St. Thomas and detouring through the Suez Canal. The boys raced canoes against village kids in the Solomon Islands. Kitty broke her leg while hiking in New Zealand. The family rented camels in Cairo to visit the Pyramids. In Indonesia, three men wearing black pajamas and ski masks boarded the Tamure.“Kitty and the kids were below doing schoolwork,” Scott says. “I start- ed yelling at them to get off, and Alex stuck his head out and noticed they weren’t armed. Next thing I know, Kitty comes out with three Coca- Colas and a pack of cigarettes. They immediately pulled off their ski masks and gave us big smiles.”

The Kuhners lived by rhythm and ritual as they circled the globe a second time in the ’80s: checking supplies, painting the hull, teaching Alex and Spencer, washing clothes in a bucket and reading magazines aloud. They wandered temple grounds in Bali, rode camels in Egypt, anchored near party boats off Bawaen Island and endured a long pause in New Zealand after Kitty shattered her leg on a cow path.

Last year, two engineers traded their desks for decks, working remotely while boat-schooling their son.

PACKING UP YOUR BELONGINGS, leaving your old life behind and traveling around the world is an adventure most people can only dream of, but for Jim Bob Schell, BSBA ’05, it’s a dream come true. This past September, the Schell family — Jim Bob, his wife, Marlie, and their 5-year-old son, Aksel — set sail on their big adventure to circumnavigate the world by boat over the next decade.

Jim Bob’s interest in boat life originated in early 2020. “For some reason, the YouTube algorithm thought I needed to watch this channel about a family who sails around the globe,” he says. Given his love for travel, Jim Bob was hooked. He soon realized that sailing would be a great way for his family to experience different cultures around the world.

“When Jim Bob first pitched the idea, I thought it was crazy,” Marlie says. “But I soon realized it was actually smart. Living on the water would be beautiful. Plus, most of our sailing would be carbon-free by mainly using wind for propulsion. This eco-friendly form of travel really appealed to us.”

There was only one problem: They had zero sailing experience. So, the couple enrolled in an introductory course at a sailing school and bought a small boat to take out on the lakes in their home state of Wyoming. After sailing to the North Channel Islands in an intensive 7-day course involving heavy weather, Jim Bob and Marlie got their certification to charter a boat on their own to the Sea of Cortez, Mexico. It was a much bigger boat than they were used to, more similar in size to the 49-foot boat they’re in now. “It was the final step to see if we really wanted to live this life, and it was an awesome experience,” Jim Bob says. Although they were much more experienced in water by then, they still needed to figure out the logistics for this new lifestyle. They hired sailing consultants to help them plan budgets, develop a homeschooling curriculum for Aksel and advise them on various other things, such as canning tips to save food. The Schells would rent out their home for supplemental income, and Jim Bob and Marlie (both engineers) could continue working part-time for their current employers using satellite internet.

The Schells — Jim Bob, Marlie and their son Aksel — turned the Caribbean into a floating classroom, blending boat chores and schoolwork with monkey encounters in Grenada, fishing expeditions, domino games in Dominica and a soak at Sulphur Springs in St. Lucia. 20.5825860

In June 2024, Jim Bob bought a Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 49i performance sailboat in Antigua and sailed it to Trinidad to store during hurricane season. On September 19, 2024, the family officially set sail on their adventure. So far, they’ve visited several Caribbean islands. They’ve spent an average of two to three weeks at each locale, depending on the weather, their affinity for the area and the number of other similarly inclined sailing families with children nearby. (To find these “buddy boats,” the Schells use an online resource where fellow sailing families can post where they’re currently anchored.)

Some of their favorite places so far include Dominica, Tobago and St. Lucia. “Trafalgar Falls in Dominica was incredible with its dual waterfalls, hot springs and lush landscape,” Jim Bob says. “It was the first place where I felt blown away. We attended Carnival in Tobago, which was spectacular. St. Lucia was the most visibly stunning place we’ve been.”

The best part of boat life? “We’re close with nature, which makes us want to be good stewards for the planet, and we’re able to spend much more time with our son,” Marlie says. “Our hearts are full because we see how much joy this life brings him.”

But it’s not always smooth sailing. “This lifestyle is amazing, but it’s not easy,” Jim Bob says. “We spend a lot of time repairing the boat and tracking the weather. Figur- ing out logistics, like getting groceries or visiting a doctor, requires a lot of planning. And it’s hard to watch Mizzou games! I usually have to catch the radio broadcast.”

What’s next for the Schells? They plan to sail to central Florida by May before hurricane season begins. Once it’s over, they’ll travel back to the Caribbean before heading to the Mediterranean for at least a year. Other must-see places for them include South Africa, Patagonia, Indone- sia, Thailand and India. “We have a general plan, but 10 years is an ambitious goal since we want to spend a decent amount of time in some of these areas,” Jim Bob says. M — Blaire Leible Garwitz, MA ’06

To live vicariously through the Schells’ adventures, follow their journey on Instagram at @sailingjaimeera.

Treehoppers communicate through tiny pulses that travel along plant stems. Biologist Rex Cocroft has spent decades listening.

Lined up like thorns, treehoppers communicate through subtle leg vibrations. The signals are too faint for human ears but can be captured with special sensors.

the mellifluous voice of Sir David Attenborough, British lilt and all.

“In the Amazon live many strange species. This is a treehopper,” the veteran actor and naturalist says during “Forests,” a 2023 episode of the BBC series Planet Earth III. The insect has a hard, tank-like protective shell. Its body is shaped like a crescent. It looks like it’s prepping for an alien attack.

“They not only have a bizarre appearance, but they also communicate in a remarkable way,” Attenborough continues. “Vibrating their bodies, they send signals through the forest plants they live on, and every sound has its own particular meaning.”

To analyze the footage and audio for this scene, which was shot within Yasuní National Park in the Ecuadorian Amazon, BBC producers connected with Rex Cocroft. For more than 30 years, the Mizzou biologist has studied treehoppers — insects found on every continent except Antarctica — and how they signal each other through a plant’s leaves and stems. His fellow researchers even took the rare step of immortalizing his contributions by naming a new species of the plant-feeding insects

Cladonota rex — in his honor.

“Treehoppers have vibration sensors that detect when their legs move up and down, and they are extremely sensitive to that kind of motion,” Cocroft says. “Sound and vibration are very closely allied in treehoppers, and they experience vibration in the way we experience sound.” Human ears can’t detect treehopper utterances, so Cocroft uses a specific kind of sensor to capture and amplify the signals.

“Piezoelectric materials produce an electrical current when under mechanical stress,” Cocroft says. He compares it to a guitar pick-up. “A piezo disk is commonly attached to an acoustic guitar’s soundboard. The guitar’s vibrations become an electrical signal in the piezo, which can be amplified by a speaker to produce sound.”

Treehoppers communicate by activating parts of their bodies, usually the abdomen. Those micromovements stimulate plant stems via the insect’s legs. The bugs can mimic cicadas

by buckling a part of their thorax to make a clicking sound. They also can shake their abdomen or hindquarters to create songlike sounds that vary in pitch, tone and volume.

“One species sounded like an oinking pig, another like mournful whale song, another as if an entire drum circle had assembled on the thin little twig, and yet another like a zapping gun sound effect from an old school computer game,” BBC director Abigail Lees wrote in a post about her experience in Ecuador.

Lees noted one species whose mother “will actively defend her fifty-or 100-odd nymphs from predators. Mum and young communicate with one another using vibrations, but it also looks like they signal visually by waving their arms like an air traffic controller if a predator comes too close.” One scene in the episode suggests that this arm-waving serves a more urgent, transactional purpose: summoning honeybees to fend off a predatory ant in exchange for nectar secreted by the treehoppers.

The insects, Cocroft explains, typically have a repertoire of several types of signals. “They are good at distinguishing between those and responding appropriately,” he says. “It’s not what we traditionally think of as an insect sound because the mechanics of producing and transmitting sounds are different. To some people, they sound more like the clicks, chirps and whistles of birds, frogs or whales.”

COCROFT WAS FIRST INTRODUCED to treehoppers during graduate school. After borrowing a recording device initially