The Community Park Design for Petersfield, Jamaica

Optional Studio 2024 Fall, Cornell AAP Mengmeng He, M.S.AAD 25'

1 ' Headdress Research 2 ' Park Design

The Community Park Design for Petersfield, Jamaica

Optional Studio 2024 Fall, Cornell AAP Mengmeng He, M.S.AAD 25'

1 ' Headdress Research 2 ' Park Design

Optional Studio 2024 Fall, Cornell AAP

Mengmeng He, M.S.AAD 25'

1 ' Headdress Research

2 ' Park Design

Through studying the content and history of the Jamaican Jonkonnu festival, it becomes clear how the headdress, with its intricate design and symbolic weight, serves as a marker of both personal and collective resistance and identity.

By reconstructing the map, one examines the distinctive features of the Jonkonnu festival. This process captures its essence and characteristics, allowing for the historical narrative to be restructured through the lens of materials.

By repeatedly using models to convey the same story, the aim is to uncover the part that truly holds profound meaning for the headdress, revealing its symbolic significance and distilling its essence through constant reexamination and refinement.

12 + 1 models

In accordance with Mr. Brown’s will, PGBS envisions the land as a community park that not only serves as a space for public activities but also generates income through a central public kitchen and surrounding event spaces, all efficiently managed to ensure sustainability.

Drawing on the way Jonkonnu united noble characters to resist slavery, this proposal uses architectural forms of varying functions as distinct characters, seamlessly weaving together functions, sites, environments, content, and people to create a cohesive whole.

Various transparent zones form distinct edges and boundaries, woven together by unique characters. This embodies my vision of bringing together all positive elements, creating a park strong enough to stand as a landmark and a symbol of the Jamaican community’s efforts.

In 18th-century Jamaica, there were only a few days each year when enslaved people were granted some respiteChristmas being one of them. With plantation work ceasing during the Christmas holiday, the celebrations were marked by grand all-night dances featuring elaborately dressed masked dancers and the beat of drums, a tradition known as Jonkonnu.

Many people, possibly including the Jamaican slave owners of the time, believed this was some sort of West African witchcraft tradition. However, Jonkonnu was, in fact, a celebration of resistance against slavery. Christmas was the only time of the year when enslaved people from West Africa were allowed to stick out their tongues at their masters. In the earliest versions of Jonkonnu, each character was created to mock the slave owners, European lifestyles, and their impact on the lives of the enslaved. Accompanied by the relentless beat of drums and music throughout the night, the enslaved people, hidden under their headdresses, would move from house to house in the community, clapping, jesting, and cheering. They would enter the master ' s house, shake hands with their owners, and demand money. Sometimes, it wasn’t until this event occurred that you even knew who lived on the next plantation.

Jonkonnu was meant to release and celebrate the enduring spiritual freedom of the Jamaican Africans, with disguise being the most significant symbol of this celebration. Jonkonnu includes eleven important characters, each with

a distinctive headdress, such as the King and Queen, the Indian Chief, the Devil, the Policeman, Cow Head, Horse Head, the Bride, the House, and the belly woman, along with the brave maroon Pitchy-Patchy, camouflaged in green shrubbery. Some characters existed from the start, while others were born in various parish performances.

I use four verbs starting with " M " to abstract the term " Headdress ": Mix, Mask, Mock, and Move. There is some overlap and interrelation between these words, with each word forming a precondition for the next, logically creating a cyclical progression.

1 2 Pitchy-Patchy Guardians of the Jungle and Folk Heroes Indian Respect for indigenous peoples

5 Bride

Marriage is the beginning of a new stage of life, and it is also a sacrifice for the reproduction of the next generation to work for the master.

4 6 Horse Head

Devil

Symbol of all evil and exploitation

Hope to have the ability to be hardworking and durable like livestock

King & Queen Policemen Policewomen

Symbolizes civilization, security, good social order and power

Wear a houselike hat, a white mask, and fancy clothes, like a house mocking an exaggerated version of European fashion Bellywomen

The ritualised sexual domination of the slave Belly Woman by the Devil of a plantation owner results in the literal belly swelling of a forced meeting of races

7

8 Act Boy

Enslaved people had no agency, no sovereignty, forced to toil endlessly in the fields until death. At the same time, these laborers, entirely stripped of political identity, also generated the potential for revolutionary violence.

With each cycle of Jonkonnu, the wildfire of revolution spread.

Mix /verb 1./

to ( cause different substances to ) combine, so that the result cannot easily be separated into its parts

The headdress is a hybrid product born from the release of multiple desires, much like the grand celebratory event it represents : Jonkonnu. The various contested spellings of Jonkonnu that persist to this day reflect its multifaceted nature in collective memory. Some believe that Jonkonnu was named after the folk hero John Canoe, while others assert it is a variant of the French phrase " gens inconnus, " meaning " unknown people." In reality, none of these theories have definitive evidence, as they all stem from an orally transmitted history.

The performance style of Jonkonnu also reveals a clear sense of hybridity. Jonkonnu can be traced back to at least three groups of West African festival traditions : ( 1 ) the annual New Yam Festival of the Mmo secret society of the Igbo people, ( 2 ) the Egungun masquerades of the Yoruba people, and ( 3 ) the Homowo yam festival of the Ga people. These festivals share traditions of revelry and celebrations featuring horned masks and other masked figures. However, the dance style of Jonkonnu cannot be ignored either. The chief steps involved a quick step and hop on one foot, then on the other, with a continuous shifting of weight from the back foot to the front foot, creating a type of vibrating action that could be likened to a rapid open coupe in the fourth position, done with bent knees. Turns were quick spins on one foot, followed by sudden stops with feet apart sideways, hips sharply forward, and arms extended to the side.

Another turn was executed with one foot remaining in the center of an imaginary circle, while the other quickly traced the circumference by alternately lifting and placing it in a new position, with knees bending and straightening alternately, and the body inclined at an angle toward the circle's center. Dancers often paused in front of each other, performing rotary pelvic movements that ended with a sudden stop. Some would break away from the group to dance solo before the spectators. These steps were common for the entire group. As a result, Jonkonnu is often considered a variant of the jig or horn-pipe, dances commonly performed by slave owners or British soldiers in the 17th and 18th centuries. The diversity of characters in Jonkonnu showcases another form of hybridity. During the revelry, enslaved people would disguise themselves by donning costumes that borrowed from and mimicked Western archetypes : admirals, sailors, queens, plantation owners, actors, all wearing dramatic headdresses. Intermingled with these figures were wild men, nature spirits, and demons, whose roots were more deeply planted in African ancestral traditions.

The blending also extended to the materials used. In colonized Jamaica, the enslaved people made headdresses from whatever they could find : leaves, nightgowns, tablecloths, rags, and more. Today, Jonkonnu performing troupes in Jamaica continue this tradition of using everyday objects, crafting hats from graters, masks from wire mesh, enormous houses worn on the head from delivery boxes, and drums for music from broken stew pots.

/verb 2./

to prevent something from being seen or noticed

As a mask, the headdress serves as a veil, concealing all revelry and release under the anonymity of the group.

In the 18th-century illustrations of Jonkonnu that can be found, the masks used by the enslaved were not the halfmasks common in their West African homelands but rather full coverings that completely obscured the performer ' s entire face. This level of concealment was so thorough that children attending the celebrations often became frightened, unable to determine whether a real person was beneath the costume.

Under such disguise, Jonkonnu transformed into an unrestrained carnival and a form of retribution. The revelers would enter the slave owners ' homes, singing around them, and if anyone failed to donate the required coins or gifts, the celebrants would sing a song with lyrics that essentially mocked, " Oh, this poor fellow, he ' s too poor to even spare us a penny. "

Moreover, the mask provided a form of disguise and detachment, offering the enslaved a temporary escape from their painful and burdensome daily lives. For a brief moment, they " became " another character - perhaps a spirit ancestor imagined in their minds or the very slave master they despised, mocked, yet were forced to obey. This was a momentary interruption of their suffering. The mask also served as a shield for their true identities, protecting the enslaved from the retribution that might follow the Christmas festivities.

to laugh at someone, often by copying them in a funny but unkind way

In 1655, the British Navy seized Jamaica from Spain, and Britain subsequently controlled Jamaica for over 300 years. By the 18th century, Jamaica had become the most valuable British colony, but the living conditions for the enslaved were extremely harsh. Families were often separated, housing and sanitation were deplorable, and beatings and torture were rampant. Many died from overwork and starvation, with the life expectancy of West African slaves in Jamaica being a mere seven years The transition from Spanish to British rule sparked turmoil, with many West African slaves fleeing to the interior of Jamaica, leading the resistance against slavery - a struggle that lasted over 200 years until the abolition of slavery. These runaway slaves were known as Maroons. They developed their own culture and, in 1739, secured political autonomy, never to be recaptured or subdued by the British.

The earliest documented occurrences of Jonkonnu date back to this period. On one hand, Jonkonnu emerged from the struggles and resistance of unfortunate West Africans, seizing any opportunity for respite. On the other hand, it was influenced by the English tradition of wassailing. In England, on Christmas Day, the lower classes would don strange costumes to " invert " their roles ; men dressed as women, young boys as bishops, and the humblest farmer or town drunk might be declared the " Lord of Misrule ". They would form rowdy mobs, storm the homes and estates of

the wealthy, making a ruckus, singing bawdy songs, and demanding entry. Surprisingly, they were often granted access and given alcohol, food, and even money. They would gamble and engage in debauchery (often culminating in marriage at the end of the revelry ) . Once the mob was satisfied, they would move on to the next wealthy estate. This tradition "acted as a safety valve, keeping class resentments within defined limits," thereby ultimately reinforcing the social hierarchy.

Similarly, slave owners may have seen Jonkonnu as a "pressure valve" . " The idea was that you had to give those who were humiliated, whipped, ordered around, had their families separated, and were sexually exploited throughout the year some way to vent their frustrations," one scholar explained. " These outlets were largely harmless, but you needed to allow them some release. " Of course, some scholars speculate more dramatically, suggesting that the slave owners of the time did not fully understand the meanings of the lyrics being sung - they assumed it was merely an imitation of elite life, which also explains the colonial crackdown on Jonkonnu in the late 18th century.

Thus, we witness scenes in Jonkonnu where the " actor boy " wears a whitefaced headdress and lavish clothing, mocking the exaggerated European fashions that a house might ridicule. Jamaican Blacks poked fun at the Europeans ' obsession with all things fancy, like furniture, porcelain, and their penchant for building houses too large for any single family.

to (cause to) progress, change, or happen in a particular way or direction

Jonkonnu is not a performance confined to a single location ; rather, it is more akin to a procession. Led by the ever-moving headdresses, it spirals through the main thoroughfares of Jamaica. This linear geographical movement represents a cultural encroachment of Black culture into the political realm.

By the mid-18th century, Jonkonnu had reached its peak in Jamaica. However, out of fear of slave uprisings, the ruling government sought to suppress any gatherings of Black people, along with the use of drums, horns, and conch shells, in an effort to eliminate the possibility of rebellion.

After the abolition of slavery in 1838, Jonkonnu began to decline further. This was due to Christian missionaries ' attempts to eradicate pagan entertainments and rituals among their converts, as well as opposition from municipal authorities, leading to one of the most severe social upheavals in the years following emancipation. This unrest, known as the " John Canoe Riot " of 1841, was sparked by the mayor of Kingston ' s decision to ban the John Canoe parade. During the ensuing clashes between enraged revelers and the militia, the mayor was forced to take refuge on a ship in the harbor.

Over time, some in society came to view the John Canoe dance as vulgar, crude, and frightening to children. Consequently, self-appointed moralists actively discouraged its practice.

Frequent clashes between bands and the police also occurred, relegating the John Canoe dance to remote rural communities. Additionally, band members began to prioritize fundraising for their entertainment activities, with raising money becoming more important than the parades and performances themselves.

Over the years, the John Canoe tradition has gradually faded, and today it is nearly extinct, except for occasional performances at organized social events. However, it is still regarded as an important aspect of Jamaica ' s culture and tradition. Today, it primarily survives through government-sponsored events like the Jamaica Festival.

In this conceptual " move ", Jamaica ' s Jonkonnu is the least commercialized in the entire Caribbean, organized by local grassroots Black artists funded by charity, rather than by commercial performance teams. However, it has also inexorably slipped toward commercialization and tourism service.

Today, Jamaica ' s Jonkonnu has added diverse roles, allowing women to participate in the performances, not just young men. Some roles have also been modified, such as the Devil now wearing Halloween-themed costumes. Artists are making efforts to preserve their culture, despite these changes.

It is overly flattened, lacking distinct structural layers, and thus abandoned.

The idea begins with how to deconstruct and reconstruct a headdress on a map. The initial plan was to use fabrics with different textures stacked upon each other to create edges and categories between the overlapping fabrics. In this version, the counter map becomes a game of textures with varying transparencies, formed by the centripetal force of the fabric moving from the periphery to the center, resulting in a transparent Jamaican map. Additionally, in the bottom-left corner, it unpacks into a complete Jonkonnu storyline.

At all times of the year, people were required to toil diligently.

On the day of the Jonkonnu festival, enslaved people gathered in the middle of the sugar cane plantation.

Cross Over

Enslaved people crossed through the buildings that monitored them, entered the master's house, and shook hands with their owner, as if they were born equal.

They moved between the houses of the masters, skipping, cheering, clapping, and dancing.

I secondly view the headdress differently, deconstructing it into a skeleton and its covering. the overlapping of different materials creates distinct, sharp edges, which both reveal and obscure the boundaries of a map.

The materials, constantly transforming in transparency and texture, are stitched together by red thread, forming a fabric. these masses take shape as clusters, representing the core plantations on the map of Jamaica.

small, anthropomorphic sculptures carry a particular kind of sorrow. their human-like elements are all drawn from Jonkonnu, where, on just one day each year, only through disguise can equality be momentarily achieved. in this sense, each of them embodies a character.

1 3 2 4

Layered burdens, where hemp ropes tightly compress various materials, reveal different states of being bound. together, they bear the weight of the glittering upper class of slavery sociery.

Hierarchy

The hierarchical structure of Jamaican slave society was built upon layers of exploitation and oppression, cascading downward.

Cotton, a staple crop of Jamaica, is tainted with blood and the soot of industry, turning it into a symbol of sin. wrapped in forced labor and iron cages, it carries the weight of its own oppression.

Beneath the layers of confinement, the slaves sought a path to the center, but their efforts only added more layers, thickening the outer shell and reinforcing the surface of the social order.

5 7 6 8

The mixing of different materials, akin to the merging of crowds, invariably gives rise to boundaries, conflict, and mutual erosion.

How do you decorate a stone by binding its edges with red thread, locking it in. by adorning it with beautiful lace fabric, concealing its essence.

A heap of small, anonymous graves displays an unspeakable sorrow. the crushed bodies lie discarded and buried, each a silent testament to profound suffering.

Stone-like Tighten it, expressing hardness with a piece of soft, elastic fabric. steel wire pierces through the material, revealing rigid boundaries in a taut manner.

speculative model version 1, 9-12

The membrane evokes an imagined boundary, with force pushing outward from within pins. At times, the pinpoints break through the surface, becoming acts of penetration, but more often, they merely press outward, distorting the form without breaking through.

The crushed and compacted slave class supports the soft, indulgent upper class (master), with an insurmountable chasm of modern industry separating them.

The enslaved people sought to enter the master ' s class, to partake in their food, drink, wealth, and social status. they attempted to infiltrate from all directions, but only found themselves inside a hollow

Peering, spying, gazing. slaves looked at the master ' s house, yearning to enter. They tried to peer inside, but all they saw was their own reflection in the mirror.

By combining the concepts of stitching and loading from the first 12 speculative models, I trace the process of stitching downward. It should follow a circular path, pulling different materials and forms along the way, manipulating them and organizing them together. At times, certain sections of the path are amplified, creating different spatial effects.

In the constraints I’ve shaped for myself, I’ve cast aside the beautiful yet irrelevant aspects of the jungle and begun to truly understand the headdress as a tool for revealing or disrupting certain behaviors and power structures. The red circulatory threads, like the all-night leaps of Jonkonnu, tug at the material, drawing it inward. On this upward path, the movement shifts from circling and clinging to the edges toward the core. What begins as a flexible outer loop becomes increasingly solidified, ultimately forming tight knots that stand in direct opposition to space.

The interaction between space and space, material and material, is like a veil through which one thing transforms into another. There’s an inherent ambiguity, a refusal to operate in a singular way. The materials overlap in layers and fuse into complex forms, constantly challenging the boundaries of their own identities.

At the entrance of the PGBS Club, Mr. Brown is clinging to the wire fence, watching the children on the soccer field.

In accordance with Mr. Brown's will, PGBS still hopes that the land will be used to create a community park, a space for picnics, gatherings, and public activities. However, a new demand emerges to generate income, ensuring that the park can sustain itself.

Building on this foundation, the park concept I envision will feature a public kitchen directly facing the PGBS Club, serving as its central core, stitching together all the spaces. The public kitchen can generate economic revenue by providing meals for the soccer field, offering cooking demonstrations to students and visitors, and functioning as a juice bar.

Surrounding this core will be three zones designed to generate income. The first is an open space that can be rented for weddings, parties, and educational events. The second is centered around the kitchen. The third is a farmer's market, integrated into the site with a dispersed layout. All of this can be efficiently managed by PGBS.

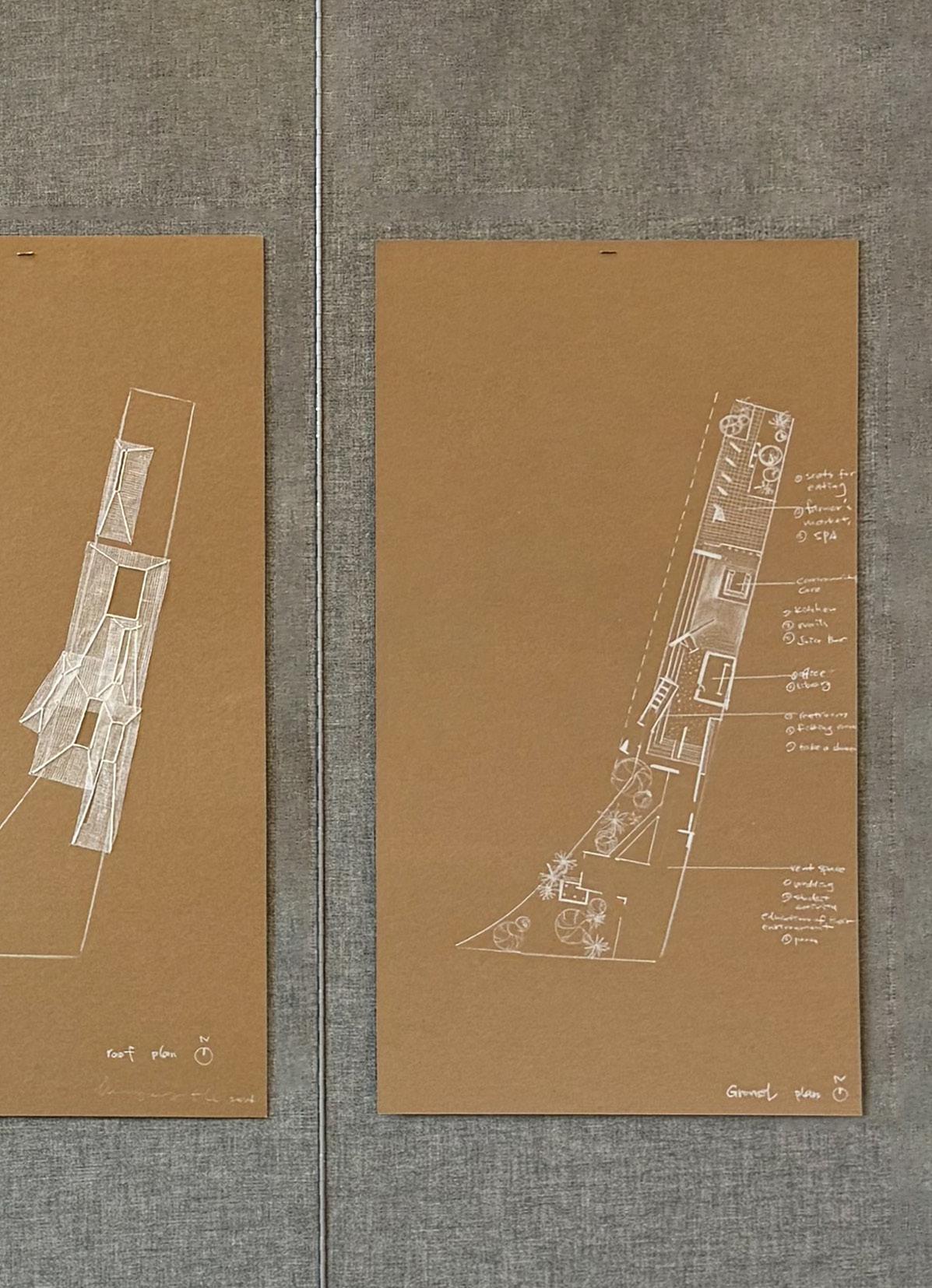

1 2 Site materials transparency fabric Diagram core public kitchen generate income farmers' market femalism education rent

The architectural form prototype is selected from early speculative models. This small house takes the form of a traditional West African dwelling, its roof heavy with the allegorical weight of Jamaica's burdensome history of slavery. A skylight at the top forms an inward gaze, leading into a layer of transparency. At its base, possibilities for entry emerge from all directions, pulling the space towards the dense roof, where, at its center, an upward break occurs.

The break in the roof is symbolic, allowing light to pierce through, challenging the weight of history. The contrast between the solid mass of the roof and the transparency beneath it creates a tension where past and present converge. The prototype becomes both a reminder and a character, drawing on the past to shape the future.

multidimensional integration

Further still, recalling how Jonkonnu gathered all the noble characters to resist slavery, the proposal uses architecture form of different functions as distinct characters, stitching together different functions, sites, environments, contents, and people.

These architectural prototypes will act as stitching, bringing together and unifying all that is good into one cohesive whole.

The site itself possesses the quality of overlapping materials, as if each layer of substance merges and interweaves with the other.

Different characters possess different functions they occupy distinct territories and carry with them varied radiating textures. They layer upon one another, densely overlapping.

Community Zone

character 1

Public kitchen as the core.

Serving community

Economic Zone character 2

Gather with vendors space to be a farmers' market.

Education Zone character 3

Computer classroom for students to learn.

Service Zone character 4

Bathroom and fitting room for everyone.

Activity Zone character 5

Rent for activities such as wedding and parties.

Void Zone no character

Stitching Fabric spaces with varying transparencies stack

Roof Plan the centripetal force of

each character space is a distinct core of multiple roofs

On either side of the public kitchen, a duality unfolds, much like the nature of Jonas. On one side, the kitchen faces and serves the soccer field, with seating on the grandstand, where people can gather, share food, and watch the match.

On the other, the kitchen, with large windows, faces the school, offering a clear view into the students ' class schedules, always ready to observe when they finish. In this way, the kitchen becomes both a communal heart and a watchful eye.

The entrance serves as a threshold, drawing attention to the flow between the external world and the interior, cultivating a sense of anticipation. Also, it integrates seating, becoming a functional space.

1 ' gather to be a giant roof

2 ' clarified interior characters

1. different function

2. environment

3. community

1. public kitchen

2. seats

3. grandstand

2 ' push and contraction

JONUS

1. soccer field

2. high school and private school

The guiding entrance reveals a silent invitation beneath the weighty roof. In its deepest recess, light emerges, beckoning you. There, in the distant courtyard, lies the public kitchen below.

A cleverly designed inward-curving wall creates seating, offering students a space to wait for the bus. They may enter the interior and use the computer classroom, a separate educational zone.

The grandstand facing the soccer field is equipped with a fence that can be closed off, while its intrinsic introspective quality extends into the space of the public kitchen.

The public kitchen can manage the space belonging to the farmers ' market. Transactions will unfold here. Thus, the kitchen stitches together the cooks and the community.

Different transparent zones create their own edges and barriers, tightly stitched together by distinct characters. This is my concept of gathering all that is good into one, making the park strong enough to become a landmark and a testament to the efforts of the Jamaican people for their community.

a+d), different entrance

c+d), jonus of the public kitchen's view

4 5

Community Zone

1. public kitchen

2. storage room

3. stands

4. the second-floor stands can be used for multi-purpose

Economic Zone

5. farmers’ market

6. vendors Education Zone

7. Seats provided for students (waiting bus)

8. communication

9. computer zone

Service Zone

10. bathroom and fitting room

Activity Zone

11. original pavilion

12. open space for renting to parties, and weddings.