Buster Simpson Constructs for the Anthropocene

Lot’s Lithium Lick, a Module for a Monument, 2022 (oppostite page) Salt lick compliments of Compass Minerals

Buster Simpson Constructs for the Anthropocene

Weber State University

Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery September 2 – November 5, 2022

Voxel Frog as Environmental Action, 2022. Rozel Point, UT. Photo: Joe Freeman Jr.

Voxel Frog as Environmental Action, 2022. Rozel Point, UT. Photo: Joe Freeman Jr.

“CONSTRUCTS FOR THE

ANTHROPOCENE is a compilation of studio and public art projects addressing some of the prime concerns of climate disruption. The selected constructs are examples of environmental and social actions, intended as suggested approaches for mitigating climate change effects through publicly sited art, in what could be considered an ecological call to arms. The exhibition presents a wide range of tactics for addressing pressing issues such as: sea rise, migrating species, acidification, sequestration of greenhouse gases, potable water supplies, sustainable energy, and climate equity.

Creative thinkers are well equipped to engage with complex issues and communicate the urgency of human response to ensure our survival on the planet. The Anthropocene epoch is of our making and will require us all to transition creatively to an adaptive future that is both life-sustaining and poetic.”

Canary in Cage, 2022

Lead glass, wood, paint, iron Hobart wire whip, and LEDs

Buster Simpson is a habitat artist.

“I am fascinated by the prospect that a work of art can evolve into habitat.”1

Urban habitats, mainly. Those of Seattle, especially. Scott Lawrimore in his essay on Buster Simpson The Sky’s the Limit2, points out that the Greek etymology of the word ecology includes the reference to ‘house’, a place of living, a site of habitation. According to the Ecological Society of America, “ecology is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environments.” It follows that ecosystems can be “a natural wilderness area, a suburban lake or forest or a heavily used area such as a city.”3

hippies on a tree farm”—Buster realized that it could also be done the other way round: “Rather than deserting the city to go back to nature, I became interested in bringing the ethos of nature into the city and finding some discussion between the systems we see in nature and the systems of the city.”7

It makes sense: the Anthropocene has come to its current boiling point due to exponential population growth and industrial expansion—’backed’ by global terraforming—over the past two-hundred years, primarily in cities. Buster’s artistic practice is social practice; he is a citizen artist committed to society and his work takes myriad forms. There are:

Early performative acts.

But don’t call Buster Simpson an ‘eco-artist’. His artistic practice has been far too inclusive and complex to satisfy the vexing need to categorize. Since the 1970s, it has been driven by his ambition to integrate art into life4 and by the artist’s social responsibility to be “the canary in the coal-mine”5—through public art works, environmental projects and sitespecific Civic-Ecological Art Plans for national and international urban districts. Incidentally, in this exhibition the proverbial canary in the coal mine has transformed into a caged canary, perching on the narrow end of the show’s title wall (Canary in Cage, 2022). The bird’s silhouette is applied to a piece of lead glass from the Hanford Nuclear Plant—the decommissioned nuclear production complex along the Columbia River—where “the viewing windows that the scientists looked through in the plutonium production reactor were made of 70% lead to protect them from the highly radioactive material they were working with.”6

And why urban?

Sometime after being commissioned to make art at the Woodstock Music and Art Festival of 1969—there “we were imagining a self-sustaining, back-to-nature, multimedia art community [...] we were just a bunch of

• A sound piece at the Pilchuck Glass School (1971) where he recorded the ‘music’ of a quiet field. Buster as Woodman (1974), wandering the streets of Seattle with bundles of urban debris on his back, gleaning from sites of reckless urban development.8

Activist environmental gestures.

• The agitprop Crow’s Nest moment (1979) took place during the ongoing Urban Arboretum project, when Buster barricaded himself in the crown of an old but still viable cherry tree which had been felled and set aside to make room for high-end condominium development. The occupation of the uprooted tree equated, as the artist put it, “the loss of nature with the loss of affordable housing.”9

• With Purge Series (dating back to 1983), Buster performed metaphoric and briefly effective healing rituals, using gigantic limestone disks (aka “River Rolaids” or “Tums for Nature” as they became popularly known)10 in contaminated, polluted rivers as an antiacid since limestone is capable of mitigating toxins.

When the Tide is Out the Table is Set, 1983-1984/2013 Environmental artwork, East River, NYC; Duwamish River, Seattle, WA

• When the Tide is Out, the Table is Set (1983-1984/2013) exposed pollution when Buster made concrete casts of picnic plates and placed them into rivers contaminated by sewage effluence. When they were taken out of the water and fired, the result was beautifullyperverse, patinated plates: the more toxic the effluence, the more intensely colored and patterned the plates.11 The title, a Salish proverb celebrating the abundance of food at low tide turns sadly paradoxical.

Comedy and Tragedy (1983/2012/2015) and Plate & Platter (after John) (1983/2012/2015) exemplify the multiple encores of this project. In this case, Buster made the plates of vitreous china —a hard porcelain commonly used in the manufacture of toilets and sinks—while doing

Plate & Platter (after John), 1983/2012/2015 Vitreous china with effluent glaze, Army issue forks, and silver serving tray

an artist residency at the Kohler Company. The addition of eating and cooking utensils confers on these plates an eerie resemblance to masks of the Pacific Northwest First Peoples, including those of the Kwakiutl, where Buster was a guest at a potlatch.

• For Downspout - Plant Life Monitoring System (1978) at Seattle’s Pike Place Market, adjacent to the artist’s beloved Belltown, Buster altered down spouts on apartment buildings to accommodate plant growth. The plant growth, in turn, filtered out industrial toxins, functioning as phytoremediators by cleansing the rain-water before it entered the stormwater and sewage system.12

There are:

Commissioned public art pieces (which often double as environmental projects)13—always compelling, never tame, always mitigating, never contentious—as well as brilliantly prescient Civic-Ecological Art Plans for urban communities from Seattle to Vienna.14

sculptural placements” along the Seattle Elliott Bay Seawall. SeaBarrier are “pre-cast concrete wall segments, with a faux sandbag motif.” Anthropomorphic Triapods, on the other hand, features dolosse, arranged to “act immediately as seating and interactive play objects” while also serving as “future deployments when shoreline mitigation is needed. Able to be moved inland over time, they are adaptable, as we also need to be, as part of a changing environment.”16

• The Seattle George Monument (1989), a topiary sculpture at the Seattle Convention Center is a mischievously ingenious public art piece commenting on the complex history of the city. Seattle’s Indigenous roots appear as a series of cut-outs making up Chief Stealth’s/Seattle’s head. The head, in turn, is overlayed by the sharp-edged template, weathervane-like, of the state’s namesake George Washington who represents manifest-destiny-driven colonialism. Both heads are mounted on a cone that suggests colonial land grabbing (the surveyor’s plumb bob) and the sculpture would eventually be covered by the vine planted at its base. As it grows, the vine will form a topiary view of Washington’s profile, seemingly in homage of this founding father. The sculpture, including the adjacent landscape, is maintained by “a mechanical watering system [that] meters out water.” If this “man-made landscape is interrupted by disease, neglect, or change of aesthetic sensibility,” however, “the armature, Chief Seattle, will be re-revealed,” thus reaffirming the true foundations of our nation.15

• Simpson’s most recent Civic-Ecological Art Plan is his multi-part, multi-use Anthropocene Migration Stage (completed 2022). It features one of Buster’s favorite object-concept, the dolos (plural dolosse): an immense, concrete tetrapod, which in large numbers and arranged in a loose interconnected manner, function as a barrier against coastal erosion (more on this later). Living in Seattle most of his life, Buster has always been interested in waterfront habitats. The implications of rising oceans due to global warming (references to this threat are scattered throughout this exhibition) have now become a priority in his work. Anthropocene Migration Stage consists of two “sets of

• The central element of Dialogue Along the Danube/Dialog Entlang der Donau (1994), a Civic-Ecological Art Plan proposal for the city of Vienna, was a “river-water pipe [...] designed to produce a fluctuating head of water pressure that would episodically reveal itself through hydrokinetic events to raise awareness about habitat mitigation along the [Danube] canal.”17 The proposal also included a tuningfork sculpture in homage of Vienna’s musical heritage and other sitespecific elements. As with all of Buster’s Art Plans—and what is true of his artistic practice in general—the Vienna proposal built upon ‘what was there already’: the city’s already existent plan to install a new sewer culvert along the river. If put into practice, Buster’s low-cost proposal would have transformed a necessary but otherwise tedious infrastructure project into an appealing, even didactic urban habitat. Dialogue Along the Danube was meant to raise awareness, make waves, so to speak, and “have citizens and visitors alike learn while having fun walking” along the ‘Blue Danube’.18

In a Nutshell: Buster Simpson cares.

About environments and ecologies; our bodies of water, public spaces, urban habitats and the health of neighborhoods; the fallout of the Anthropocene and rampant pollution; the moral responsibility of the artist to their fellow mammals and other species; the “urgency of pedagogy”; and the necessity of an “urban consciousness.”19

Buster’s ‘social sculpture’ parallels and echoes German artist Joseph Beuys’

call, first made in 1967, for an expanded understanding of art, away from the exclusionary, even hedonistic practice of art-for-art’s-sake and towards a definition that everyone is an artist because each one of us is the creator of our life and therefore also the creator of a viable and beneficial society. Social sculpture calls for “flexible thinking” and asserts that it is “never complete” and constantly changing.20 Buster Simpson responds to the call of ‘art-into-life’ with his “Constructs for the Anthropocene.”

The Anthropocene...

is “the current epoch in which humans and our societies have become a global geophysical force.” The term “suggests that the Earth has now left its natural geological epoch” and that “human activities have become so pervasive and profound that they rival the great forces of Nature.”21 It was coined in 2000 by the Dutch meteorologist, atmospheric chemist and Nobel Prize recipient Paul Crutzen who proposed that the human impact on our planet is so vast in scale that it constitutes a new geological epoch. Though the notion of the Anthropocene has not yet been granted official geological time designation, “the concept has since gained a firm foothold” among geologists, other scientists and in the general population.22

points to the distant beginnings of the Anthropocene.

Conversely, the attendant diptych (Assisted Migration/Empty Tanks, 2015/2022) brings us into the presence of what scientists call “The Great Acceleration,” the explosive increase in technology, resource extraction and global consumption beginning around 1950, aka the Atomic Age.24

A lineup of oil tank cars, parked in the Utah desert, is juxtaposed with the artist’s hands planting mangrove saplings, or ‘sprouted pups.’ A repeated theme in the exhibition–fossil fuels and their devastatingly dominant role in this “climate endgame”25– are challenged by the tender shoots of mangrove plants.

The harbinger of the Anthropocene dates back some 10,000 years to the Agricultural Revolution, when early humans transitioned from hunting and gathering to settled farming communities. That impact on the earth, initially negligible but intensifying over thousands of years, culminated in the Industrial Revolution around 1800. Its central feature, following the virtual deforestation of much of Europe, “was the enormous expansion in the use of fossil fuels”23 which has since relentlessly progressed into the 21st century.

Praying Mantis (2019), mounted on the exhibition’s title wall, is a conglomerate of stained, dis- and newly re-assembled agricultural tools (pickaxe, hoe and their handles) and fused with what might read as a symbol of domestication (bedpost). As a suggestive social sculpture, it

Constructs for the Anthropocene (Installation view, Shaw Gallery at Weber State University)Praying Mantis, 2019

Wooden axe handles, axes, pitchfork, hoe, and stain

“Mangrove forests, specifically their thick, impenetrable roots, are vital to shoreline communities as natural buffers against storm surges, an increasing threat in a changing global climate with rising sea levels.”26 However, the propagation of the mangrove spores depends, among other factors, on a distinct water level—which is seriously endangered by the rising waters due to global warming.27 The subtle graphic similarity between the extended oil tank cars and the equally extended arms of the artist and his companion may evoke yet another level of conversation between the two halves of the diptych, as does the fact that the artist chose to place the mangrove panel above the industrial panel, dominating it, perhaps allowing a sense of optimism to rise to the surface.

Art as mitigator. Mending. Healing. Constructs for the Anthropocene. Proposals for sustainability. Artistic interventions for the common good.

We must be reminded constantly of the big picture underlying this exhibition, as Buster’s individual pieces are so rich with layered references that it is easy to get side-tracked in his prodigious environmental storytelling.

The story of the Anthropocene continues on the south wall with a photo of the mesmerizing array of grapevines near Mecca, a vital agricultural community located in the parched desert of California (Divining Agrarian, 2012/2020). The entire proposition is unnatural; it is absurd. But there it is, thanks to the services of the divining rod, attached to a frame, which is poignantly fashioned from a storm-window. Our species is ‘divining’ (an oddly inappropriate word) the water needed to make the desert fertile for agriculture from the Colorado River, the beleaguered source of water for much of the Western United States. The divining has worked for a while; alas, the Colorado River is drying up.28 With a world population of over 8 billion people, and the Great Acceleration ever accelerating, the Anthropocene has reached critical mass. So have the “planetary boundaries [such as freshwater use, ocean acidification or stratospheric ozone depletion] within which humanity could continue to develop and

Assisted Migration/Empty Tanks, 2015/2022

Archival Inkjet prints with storm window frame

Planting of mangrove pups, Rising Waters Confab, Robert Rauschenberg Residency, Captiva Island, FL; Google Maps Street View image, west of Salt Lake City, UT

Divining Agrarian, 2012/2020

Archival Inkjet print with stainless steel model and storm window frame

Irrigated vineyard, Mecca, CA; model for public artwork, Divining, Latta Nature Center and Preserve Visitors Center, Huntersville, NC thrive.” The Earth system, which consists of interrelated ecosystems and habitats, has been seriously compromised.29

The local is global (and the global, local). The butterfly effect. Six degrees of separation—Buster tackles anthropogenic transgressions on the local level with his artistic practice. Grim diagnoses and this writer’s tirades aside—the artist’s mitigating solutions to environmental maladies are, after all, more constructive than ranting—Buster in Divining Agrarian correlates the shape of the divining rod with that of the grapevine supports to suggest the ultimate hubris of water retrieval with the illusory help of heavenly agency.30

Reworked versions of Pinkie and Blue Boy31 (P & BB - Veiled Bequest III, 2020 and P & BB with Lenticular Lens, 2014) announce another major phase of Buster’s orientation toward the Anthropocene. Both paintings are iconic for the self-importance of the early Industrial Age, albeit preceding the invention of photography which would largely replace portrait painting as a genre.

The merging of the two figures—eerily smooth for the faces and awkwardly askew for the bodies—sets the tone for complex questions in relation to the Anthropocene: about evolution, about humanity, about gender, about the role of art in society, even about the role of color. Note the original gender-dictating colors of pink and blue which in the artist’s

Trinity, 2022

Northern hemisphere print, Boeing vellum print, plastic templets of nuclear fallout prediction, glass, wood, aluminum, and slotted shims

lenticular version have been complicated by rendering gender/color fluid.

The obscured version of Pinkie and Blue Boy (Veiled Bequest III) foregrounds the building blocks of life—carbon (the basis of all living organisms) covers the male, and limestone (the stratum containing the beginnings of life—fossils) the female halves. Taking this gendered reading a step further, one could suggest that the mitigating properties associated with limestone have been attributed to the ‘female’ half, while carbon, in the guise of coal—the impostor, the bad seed—have been attributed to the ‘male’ half. These binary assignments have been ‘veiled’ however, allowing for more nuanced interpretations. The angular shape resulting from the limestone-carbon overlay aggressively thrusts into the viewer’s space as if to echo Claes Oldenburg’s credo “I’m in favor of an art that does something other than just sit on its ass in a museum.”32

instance. His choice of oil drums as ‘plinths’33 for his constructs magnifies an ugly truth: that our addiction to, and dependency on, fossil fuels is the driving force—no pun intended—of cataclysmic climate change and the pinnacle of the Great Acceleration.

But I am jumping ahead in the geological timeline.

Pinkie’s and Blue Boy’s literal dominance over nature, standing not in nature but high above it (while reducing that very nature to a romanticized backdrop), signifies that critical point in the Anthropocene, when human activities begin to ‘rival the great forces of Nature’.

Limestone has been one of Buster Simpson’s favored art materials; it is of course also one of the main sources of fossil fuels—coal, gas and oil for

Trinity (2022), with its view of our Blue Planet at night and the burning of energy prominent in the industrialized parts of the world ‘where the lights are always on’, addresses another anthropogenic bottom line, that of the Atomic Age.

Gubbio Dipstick, 2014-2017

Archival Inkjet print, dip sticks, leveling staff, cherry wood figure with bobber head, hard drivedisc, glass cylinder with water, and Monopoly game components

Superimposed on this global night sky are two cone-shaped plastic templates used as part of a device to measure nuclear fallout. Their tight positioning, yet pointing in opposite directions, indicates the potential for mutual destruction by nuclear power—whether originating from the industrialized eastern or western hemispheres. Etched onto the templates are missiles—carrying the bonanza of bombs—and numbers alluding to the tremendous speed and distance nuclear fallout travels after the initial blast. The title of course refers to the explosion of the first atomic bomb (part of the Manhattan Project) at the so-called Trinity Site in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, but it also resonates with overtones of sanctification, as did Divining Agrarian. Not even a month later, on August 6, 1945, the United States would use the atomic bomb to destroy almost the entire city of Hiroshima in a matter of minutes.34 The Great Acceleration of the Anthropocene had begun. “I am full of happy thoughts” was the artist’s ironic comment during a conversation about this piece.

captured in the photograph.

Taking the viewer back to a pre-human moment in geological time, Gubbio Dipstick (2014-2017) is an homage to an extremely rare layer of iridium, a naturally occurring metal, first discovered in Gubbio, Italy, and now established to be what Buster calls a “seam” found in various parts across the globe.

The Gubbio layer was discovered in the 1970s, and since then has become a pilgrimage destination for geologists. It is also a compelling geological detective story. The layer, aka the Cretaceous-Paleogene or K-Pg boundary layer, is “evidence that a 10-kilometer-wide bolide smashed into the Earth 65.5 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, extinguishing half the life forms on the planet and finishing off the dinosaurs.”35

The tree-branch is a relic from the cherry tree (see Crow’s Nest above) Buster was unable to save in 1979. Combined with the fishing bobber functioning as a head, and the hard drive functioning as a halo, the shape of the branch evokes Christ on the Cross—the branch has been given the sanctity appropriate for the deceased. In this context, the dipsticks may obscurely allude to the Crown of Thorns. And in their obvious function as measuring devices for oil, they are perhaps in an uneasy, metaphorical conversation—’oil and water do not mix’— with the large water level gauge that appears to hold all the components of Gubbio Dipstick together. Gubbio, incidentally, is only about 20 miles from Assisi, the birthplace of Saint Francis, the venerated patron saint of animals and the natural environment in this region—certainly an eminent saintly position in the context of this essay. But the artist also suggested that Gubbio Dipstick could be an indirect critique of antiquated religious belief systems, as it proves, so to speak, the biblical creation stories wrong.

The health of water, the amniotic fluid of (not only) human evolution—find your inner fish—is one of Buster’s many worries. Ralph Waldo Emerson, living during the Industrial Age (1803–1882) respected water and accorded it the advantage over ‘civilization’ as one of the great natural forces. It seems fitting, considering Buster’s mixed media constructs and projects to include a piece of literature, a poem, in praise of water:

The Water understands Civilization well;

The aslant, gilded frame insists on the significance of that seemingly ordinary stratum, iridium—devoid of life—but is sandwiched between layers of limestone—thriving with fossilized ancient life. The purposeful tilting of the frame references the uplifting of the geological strata as

It wets my foot, but prettily, It chills my life, but wittily, It is not disconcerted, It is not broken-hearted: Well used, it decketh joy, Adorneth, doubleth joy: Ill used, it will destroy,

In perfect time and measure

With a face of golden pleasure Elegantly destroy.

Gubbio Dipstick is a construct with “poetic utility”36— poetic in its artistic sensibility, utilitarian in its social relevance. Buster’s aesthetic finds value in found objects which he recycles and repurposes in complex constructs. Limestone and water return in the next two pieces of this geological timeline.

The starkly black, white and red composition of Purge at Hand (1985, 2013/2022), its limited graphic elements, stenciled lettering, even the vertical format of the artist’s hand fiercely grabbing a block of limestone above his ‘Sea Rise’ pants, resemble the work of Russian Constructivists from the 1920s. These visual elements emanate a strong sense of agitprop, that dynamic and efficient dissemination of political and civic ideologies originally associated with Russian revolutionary poster designs. The inscription “Anti Acid Purge Direct at Source” refers of course to Buster’s Purge Series mentioned earlier. The adjacent black and white photo—Nisqually Headwaters Purge (1984)—shows the artist performing agitprop as he releases limestone into the headwaters of the Nisqually River in the Cascade Range, “seeding” it as he put it, and sending the river on its way with good karma.

Constructs. As viewers move on, both along the walls and into the gallery space, they continue farther down the rabbit hole of the Great Acceleration. Buster’s constructs are standing on oil-drum plinths or right on the floor, hugging corners, being suspended from the ceiling or dangling from the skylights, not to mention the pieces installed outside the gallery—in front of the art building, in the small back courtyard and on the hillside facing the nearby parking lot. Some of them are artifacts from previous environmental art events, some are references to existing public art projects, others re-worked or new art works. Never, however, are these constructs singularities, standalones. They are social sculptures with interconnected directives for mitigating, mending and healing our habitats; they are (and bring) ‘art into life’.

Buster’s unique decisions concerning the exhibition’s layout and installation further reveal his affinity with Russian Constructivism. This mainly Russian (Soviet) revolutionary art movement was committed to an ideology of art in the service of society—as is Buster; they reinvented the artist as “engineer, agitator and constructor,”37 and even devised neologisms for ‘art.’38 Their intention was to diminish the white cube effect of the traditional museum space and instead create ‘real space for real materials.’39

Silt Fence Poetry, 2022 Student-produced concrete poetry on black silt fencing Installed on the Weber State University campusPurge at Hand, 1985, 2013/2022

Black and white photograph and remnant of the artist’s High Water pants with storm window frame

Nisqually Headwaters Purge, 1984

Black

white

Corner Construct:

In Advance of the Snow Shovel, 2010

Archival Inkjet print and hand-painted readymade snow shovel. Social action to enlist students to shovel snow for fellow students, College of Engineering, University of Maine, Orono, ME

Corner Construct:

Type Trigger Brooms, 2003

L.C. Smith typewriter keys and components (later re-engineered to serve as trigger mechanisms for Smith & Wesson guns), wood, and brooms Sandbags for Denial, 2022 Yellow sandbags

Buster’s corner-constructs are just that: real space for real materials. The artist has placed constructs into all four corners. A snow shovel (In Advance of the Snow Shovel, 2010), occupies the southwest corner of the gallery and is imprinted with an accolade to labor. The shovel is an artifact from a public event at the land-grant University of Maine where students enacted the university’s mission of combining “scientific knowledge and physical industry” by communally shoveling snow on campus. It is also a smart repartee to Marcel Duchamp’s readymade Dada snow shovel (In Advance of the Broken Arm, 1915). Buster cheerfully refers to it as a “Duchamp roundtrip”40—Duchamp wittily (and shockingly at the time) declared this functional tool to be as much a piece of art as any other sculpture, with Buster reinstating its ‘poetic utility’ almost a century later.

In the northwest corner are cousins of the snow shovel (Type Trigger Brooms, 2003), two brooms with handles reminiscent of wooden rubberband toy guns whose triggers are typewriter keys. (During installation, the brooms had been joined by a mop which has moved diagonally across the gallery into the southeast corner.) The two brooms and the lone mop reveal the artist’s love of loaded (pun intended)—puns. L.C. Smith not only refers to “one of the finest shotguns ever made,”41 but also to the Smith typewriter company (eventually Smith Corona), and to the fact that manufacturers of firearms also were the first to make typewriters, the mechanics of a gun trigger and type-writer key being closely related.42 If the use of the corner is ‘constructivist’, the constructs themselves have a delightful Dada aura.43

fashioned from electricians’ gloves, precariously seesaws above the viewers’ heads. Next to it, Crow, King of the Hill (1977/2013), a video shot by Buster, shows “crows fighting over a single perch—a finial on top of a flagpole—their territorial dance akin to the children’s game King of the Mountain.” Crows are significant for Buster, “because they have adapted in unique ways to the urban habitat as their natural habitat has been replaced by the man-made.”44 Crows are also “dumpster-divers— great urban foragers,”45 as is Buster’s reclaim-and-repurposing practice. With the sculpture Finial (2013), the artist has constructed a poetic, whimsical solution—and an artificial habitat—for the fighting crows in the video: the generous nose cone of a plane has replaced the slender flag pole and sprouts a multitude of finials for the crows to land on.

Which brings us back to ‘real space for real materials’ and Constructivism. Like the corner constructs, the silt fence that has replaced the gallery’s wainscoting rejects the conventional museum space and creates a ‘real’ space for Simpson’s constructs. As with everything Buster conceives, the silt fence evokes layered meanings: it immediately “dramatizes” the room and makes it appear to be “drowning in oil.”46 As a “sediment control device used on construction sites to protect water quality,” it “makes transparent” environmental issues. Its ambiguity as a fence, both protective and partitioning, may allude to the artist trying to “balance being a pessimist and an optimist,” and affirming the ever-changing character of social sculpture. In conversations, Buster also suggested a topical reference to the protective wrapping (and sandbagging) of Ukrainian public art from Russian attacks.48

In the northeast corner: crows—Crow Bar with Finial (1983-2004) and Documentation of Crow Bar Bottle Trap (1983-1984). A filmstrip-like black and white photo-documentation shows unsheltered people in a Seattle alley throwing empty booze bottles at metal cut-outs of crows. The event was a modest fundraiser for the Pike Place Public Clinic—and angertherapy at the same time, comparable to the current trend of ‘Smash-It’ venues. The sculpture of a crow (Crow Bar with Finial, 1983-2004), wings

Corner Construct:

Crow Bar with Finial, 1983-2004

Crowbar, glass, rubber gloves, tar, anodized aluminum finial, and stainless steel

Documentation of Crow Bar Bottle Trap, 1983-1984

Laminated black and white photographs

Finial, 2013

Life Jacket, 2002

Life jacket with stencils

Offering for homeless encampment on a flood plain, San Lorenzo River, Santa Cruz, CA

Luck, 1984

Vitreous china with iron lag bolts Kohler penitentiary toilet seat modified to resemble draft horseshoe

And let’s not forget the umbrellas (Umbrellas as Agitprop, 2003) and the lifejacket, suspended from ceiling spaces breaching the prescribed confines of the gallery. Three of the umbrellas are covered with pH indicator dyes registering the acidity in rain while two are covered with Kevlar, augmenting the objects’ protective function and referencing the 2014 Hong Kong so-called “Umbrella Movement,” when thousands of democracy protesters shielded themselves from police pepper spray with umbrellas. Their unconventional placements force the viewer away from their complacent eye-level vistas, transforming the gallery into a ‘real space’ of civic engagement while maintaining the “wonder and resonance of art.”49 Do not forget to look up as you leave the gallery and take in the amusingly suggestive Luck (1984) above the gallery

doors—a toilet seat made from vitreous china which has been modified to resemble a supersized horseshoe complete with nails.

Ironically, this segment, which began with affection for Russia, descends into a lament about that very same country. True to Buster. True to the complexities of life. True to social-artistic practice. Nothing is unequivocal, categorical, black or white. All is in flux, always. So how do you not use that as an excuse to give up creating, not use that as an excuse to settle on the creation of just one majestic ‘land-art’ gesture like Michael Heizer’s lonely, secretive, exclusive, obsessively personal City (finally finished after fifty years)50 in the Nevada desert, evoking the grand habitats of civilizations like the ancient Maya?

Umbrellas as Agitprop, 2003

Three umbrellas with pH dye to indicate acid rain and two umbrellas with Kevlar paint in support of the Hong Kong Umbrella Revolution

You are Buster Simpson.

improving mismanaged habitats.

Nature versus Culture?

Of course, epic pursuits like Heizer’s City, James Turrell’s Roden Crater (ongoing since the 1960s) or Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty are impressive, wondrous and certainly have their place in art(history). My indictment of Heizer, a hero of ‘land-art,’ was inspired by Scott Lawrimore who rectified the art historical canon of environmental art in a paragraph titled Canon Fodder: “When art devotees are planning future pilgrimages to the major works of Walter de Maria, Michael Heizer, Nancy Holt, Robert Smithson, James Turrell, and others, they should always consider Seattle, Buster’s city, a vital stop on their itinerary.”51 Though Lawrimore’s analogy is a bit like comparing apples with oranges, Simpson’s life-long commitment to social practice and exploring, in project after project, artistic solutions to environmental ailments, is more than deserving the same stature accorded to these already canonized artists.

There are many ways of creating awareness about the anthropogenic environmental crisis, and the jury is out as to what works best. Exhibitions like The Fragile Paradise, 52 which I visited this summer, with its huge, crisp, stunningly beautiful images of global environmental disasters, will punch your stomach, for a while, but ultimately wash over the viewer in this age of visual saturation.

Buster Simpson’s art eschews instant recognition and refutes the quick glance. It demands patience, reflection and finally asking questions. It is complex, complicated and stratified. It is an art of endurance, and has a “long view of history.” Buster does not propose quick fixes—”no hypothetical hypodermics with instant antidotes.”53 His constructs and projects reveal the six degrees of separation that dictate the climate crisis. They are site-specific, culture-specific and personal-specific; they are fragments, collages, combines (to borrow Robert Rauschenberg’s name for his own sculptures); they are interventions and solutions for

Buster Simpson has always worked with found materials. Instead of a tabula rasa attitude, he honors the source material at hand, for instance by “reorchestrating rubble”54 in the construction of a new park.

This also means that Buster does not work against dichotomies but with them.

The urban versus the rural, the city versus the countryside, nature versus culture, or for that matter nature versus technology—these clichéd dichotomies exemplify binary thinking that used to dictate our concept of the environment, for better or worse. When writing about the Spiral Jetty, Robert Smithson pointed out that “even the most advanced tools and machines are made of the raw matter of the earth,” and in that sense “not much different from those of the caveman.”55 In the same vein, Native American author Tommy Orange, in the prologue to his novel There There (2018), talks about “urbanity” and the fact that “the process that brings anything to its current form —chemical, synthetic, technological, or otherwise —doesn’t make the product not [my emphasis] a product of the living earth.” Nature is “not something you go to, leave the city for, and arrive at after a long journey.”57 Nature is everywhere. The longer we insist on ingrained dichotomies like ‘nature versus culture’, the harder it becomes to build bridges and take first steps to change and reclaim what is already there,58 and thus break down useless codified categories or ideological hurdles that only lead to resignation and stagnation.

If you cannot deconstruct the dam, improve it, mend it, mitigate its environmental impact, replace it with solar power [we have plenty of that], furnish it with poetic utility.59 The Monolith (2005) and Migration Blockade (2021) take on these very structures: their sometimes dubious functions (providing power for warfare—see below—or feeding our lust for bitcoins, computer chips and data clouds)60 as well as their obstruction

Migration Blockade, 2021

Photograph, diffraction grating, aluminum, plastic, solar panel, hard drive discs, and silicon

of fish habitats. The Monolith proposes the replacement of Shasta Dam with a solar energy panel—in the shape of the dam. The structure that would serve as a ‘plinth’ for the panel used to be part of the plant that processed the aggregate needed for the dam’s construction, which began in 1938; the plant-plinth—there is always embedded meaning in Buster’s ‘plinths’— with panel would effectively become a functioning agitprop sculpture. Shasta Dam became a significant provider of power to support WWII; its workers “knew the importance the dam would play in winning the war” and the dam was indeed put in service in 1944, 22 months ahead of schedule.61 Migration Blockade addresses the fact that for salmon and other fish depending on migration for their survival, dams often create unsurmountable barriers, no matter the availability of fish ladders or stressinducing bucket transports.62

Belltown, Belltown Pans, Bells

Apropos ‘urbanity’: it may be overdue to introduce Buster’s urban laboratory, his beloved Seattle Belltown neighborhood.

Despite Seattle being Buster’s favorite playground, let me reiterate: the local is global (and vice versa). Still, why should we desert-dwellers be concerned with shoreline habitats and rising oceans? Exactly because we live in a desert; exactly because ecosystems have no closed boundaries; exactly because the rising oceans are the result of global heating (not just warming), which is emptying the rivers (plus: there is consumer demand for ‘Divining Agrarians’); exactly because our Blue Planet consists of ‘interrelated ecosystems and habitats’; exactly because we are all connected by as little as six degrees of separation. But I was going to talk about Belltown.

The exhibition features a sculpture of Belltown Pans (1980-1983/20172020) mounted on an oil-drum and fanning out from a central pole—like pole dancers, or a playful whirligig, inviting interaction.

Belltown Pans, 1980-1983/2017-2020

Recycled aluminum

Community social action, Belltown, Seattle, WA

Since Buster Simpson is the most engaging and meticulous storyteller of the environment, I want to refer the reader to the delightful description of Belltown Pans63 on his website before selecting a few highlights from that site and other sources.

Buster Simpson has called the Belltown neighborhood his “laboratory.” The Belltown Café and Two Bells Tavern were the hangouts of Seattle artists in the 1970s and 80s.64 This is where Buster started his ongoing Urban Arboretum projects with the SRO Tree Guards (1978-2000), lovingly trying to preserve trees endangered by development as well as protecting new growth. Using discarded metal bed frames from Single Room Occupancy hotels as well as crutches—both icons of unsheltered people—he shielded the trees with the headboards or supported weak branches with crutches. In 1998 “a foundry pattern was created from original bed frames and crutches,” effectively merging the two, and “an edition of cast iron tree guards was made using melted down automobile engine blocks.”65 As mentioned in the introduction, Buster even barricaded himself on top of the cut-down cherry tree to protest its death due to reckless development. Unfortunately, he was unsuccessful66 but as we saw, a relic from this event has become part of Gubbio Dipstick (2014-2017).

Implicit in a bell’s ring to action, however, is also the ‘tolling of the bell,’ announcing imminent danger, even death, which is clearly the moment to act. The Palouse Campanile (2008-2013) in the building’s courtyard, are stacked-up disc harrows,”farming implements used to prepare the soil for planting by breaking up the clods and surface crust, thus improving soil granulation and destroying the weeds.”69 The disc harrows in the Campanile are held in place by yokes—ancient utensils summoning once again the agricultural beginnings of the Anthropocene. The artist also pointed out the quasi-homophonic similarity of ‘harrowing/heralding’ and invites the visitor to take action by striking the bell.

But there is not much time left for action and the fragile glass iterations of bells in Buster’s work emphasize the urgency of civic engagement. In 2018, the “Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had concluded that we had 12 years left to avert catastrophe”70—that leaves us with 8 years.

The Belltown Café was the “social hearth of the community [...]. Simpson designed the exterior sign for the café, a large baking pan in the shape of a bell [...]. A reclaimed copper sauté pan served as its clapper.”67 On his website, Buster lovingly describes the tradition of a community Root Pie Festival in the early 1980s, the pies all baked in bell-shaped pans and using many Indigenous root veggies. He concludes by referring to the pans as “symbols of community involvement [...] symbolic of bells as instruments, used to call people to action,” and “a bellwether for local civic urbanism.”68 A revival of the festival took place between 2017 and 2022, with multiple restaurants participating which connected a now rapidly changing neighborhood.

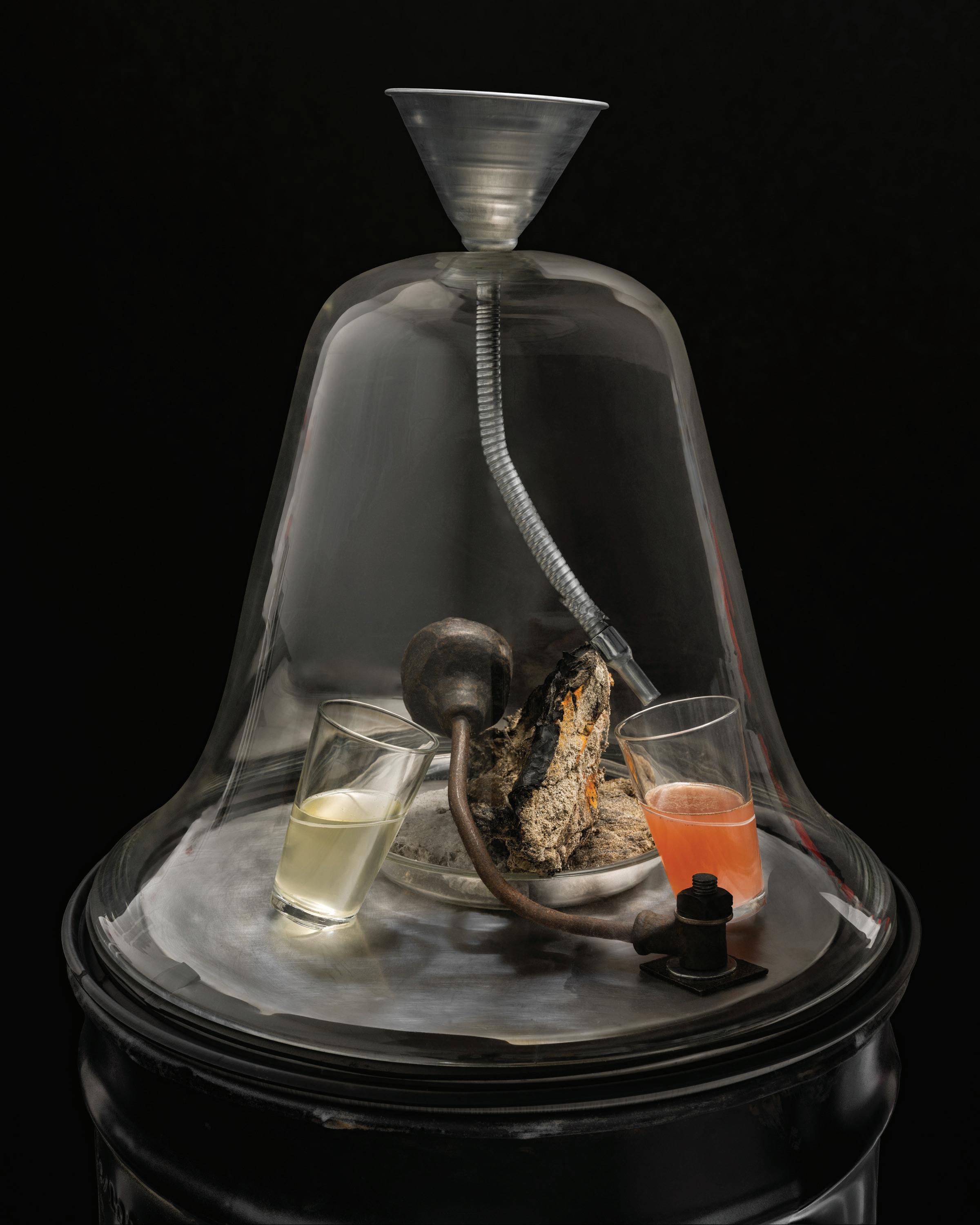

In one of several efforts to contextualize his constructs within ‘the local’, the glass Bell Jar/Reliquary (1993/2022), has been updated for this exhibition: it now contains “water from the northern [the pinkish liquid] and southern reaches of the Great Salt Lake, courtesy of the Great Salt Lake Institute”71 as well as a chunk of salt and tar from Rozel Point, the location of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty. Buster visited the Jetty during the exhibition installation and returned with an epiphany about the striking permutations associated with it (and its surroundings)—how the Jetty ‘keeps talking to us’ across time. Recently, the Spiral Jetty has become an indicator of the rapidly receding Great Salt Lake, crusty witness to the Great Acceleration. Fifty years ago, however, so the story goes, Smithson briefly contemplated raising the Jetty by fifteen feet to prevent weathering and rising waters from taking over his artwork. The Jetty is now becoming one with the rising salt and sand of the dry lake bed. The irony is palpable.

Bell Jar/Reliquary, 1993

Blown glass bell, oil funnel, bell clapper, pie plate, tipping pints with water from the northern and southern reaches of the Great Salt Lake courtesy of the Great Salt Lake Institute, and salt and tar from Rozel Point, UT

Dolos with Drum, 2011/2022

Steel form for 1-ton concrete dolos with 55-gallon drum

Dolosse, Sandbags, Life-Rafts and Umbrellas.

Safeguards. Mitigators. Barriers. Bulwarks. Protective devices. Anchors. Armor.

Dolosse, quoting from the introduction, are immense, concrete tetrapods which, in large numbers and arranged in a loose interconnected manner, function as barriers against coastal erosion. They are a “proudly South African” invention from 1963, when severe damage at the Cape’s coastline led a certain Eric Merrifield to the realization that a more “porous” freeform arrangement, “would be more resistant to the forces of nature [...] instead of bearing the full brunt of the force on one solid plane.”72

Dolosse are now used globally.

Buster Simpson has put dolosse to multiple uses and accorded them aesthetic, practical and metaphorical meanings. His most recent use in a public art project is the Anthropocene Migration Stage (2022), discussed earlier. For this exhibition, the visitors are greeted by Dolos with Drum (2011/2022), ominously lurking outside the Kimball Visual Arts Center, luring us—perplexed and intrigued—into the gallery.

There, the left panel of a dolosse diptych (Dolos as Mitigator/Armor, 2014/2022) shows part of the public art project Cradle (2014) in Portland, Oregon, where “four anthropomorphic concrete anchors cradle three ‘root wads’ awaiting the deployment of their woody debris-offering in support of habitat enhancement along the [Willamette] river’s edge.”73 In line with the ever-changing flexibility of social sculpture, the right panel is sadly topical: it shows the use of dolosse as armor against tanks in the ongoing war between Ukraine and Russia, radically different from its intended environmental usage. An image of the I-beam “hedgehog” obstacle-zone behind the Berlin Wall on the Cradle website page suggests further visual parallels with the dolosse.74 In conversation, Buster even compared the dolosse to hulking sumō-wrestlers—though I would not have immediately noticed that anthropomorphic simile, it is there, once pointed out.

The sandbags —lots of them— are imprinted with the names of Utah oilfields—”Utah has over 200 oil and gas fields and 5200 producing wells.”75 The letters following the names of the oilfields represent the specific types of extraction at each site. One such bag is resting at the base of Stick with Point (2016/2022) (more on this later), and includes, once again, the name Rozel Point.

Sandbags, just like Buster’s high water ‘Sea Rise’ pants, are of course used to alleviate flooding; umbrellas are used to keep (acid) rain at bay; liferafts, in a worst-case metaphorical scenario, may become the new and only habitat for shoreline communities.

Dolos as Mitigator/Armor,

Archival Inkjet prints

2014/2022

Dolos as habitat mitigation, deployed by the artist; Dolos as armor, deployed by Ukrainian defenses as tank mitigation

Photo (right): via Will Vernon, Twitter

Impending Landfill Leachate, 2016-2017

Archival Inkjet prints with hand-coloring on paper Collage suggesting the impacts of rising waters on septic fields and landfills located at sea level,east of Pine Island Sound, FL, Rising Waters Confab, Robert Rauschenberg Residency, Captiva Island, FL

The four striking inkjet prints of the brightly orange life-rafts—Engulfed (2013-present) and Climate Refugee Series (2015)—with their almost transparent chairs are sculptures resulting from the 2015/16 artist-led confab “Rising Waters” at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in Captiva, Florida. Rauschenberg’s love of creating art—his combines—from repurposed jetsam and flotsam coincides with Buster’s artistic practice and like Buster, Rauschenberg frequently used chairs in his artwork. The Anthropocene dependent on life-rafts—that is powerful agitprop, but it is photographed with a sublime ‘cool’ that belies the urgency of the situation. The one piece of vegetation suspended in a life-raft; the one chair held up by a life-raft—nature and culture, inseparable, trying to survive. Chairs may be read as an analogy for the human body: in one of the photos it remains ambiguous whether the life-raft is hauling humans to safety or whether humans are desperately dragging their ‘last straw’

into the climate endgame. The Rising Waters Confab at the Rauschenberg Residency generated much more than the life-raft projects and it is worthwhile, once again, to check out more details on Buster Simpson’s website.76 Also note the partial view of a life-raft in the nearby Impending Landfill Leachate, 2016-2017, one of Buster’s “mentoring boards” as he calls his eight-foot-long collages. Here, invasive sea snails are clinging to a life-raft for dear life, their natural habitat altered, evidence that everything on the planet is in constant flux where—in an almost paradoxical twist— even unwelcome, non-native species become endangered species. The subtle tilting of one of the photographs is perfect Buster Simpson guerilla tactic: there is the impulse to ‘correct’ the hanging, but as the viewer tries to do so visually, they realize that adjusting the frame would result in ‘rising waters’ on the horizon-line. The frame-tilting is a sly and effective gesture with poetic utility.

Engulfed, 2013-present

Archival Inkjet print

Climate Refugee Series, 2015

Archival

Discombobulated Discourse, 2015

Archival Inkjet print with storm window frame

Temporary installation with modified aluminum ladders and buoys, Duwamish Revealed, Seattle, WA

Photo: Joe Freeman Jr.

Photo: Joe Freeman Jr.

Chairs and Conversation.

Chairs are sites of conversation, of coming together as a community, to be social, talk, discuss, complain and even solve local issues. Take, for instance, Buster Simpson’s A Declaration of the Necessity for the Common Good (2004), featuring the Windsor chair, “the most democratic of chairs [...] produced throughout the thirteen original colonies that sent representatives to sign the Declaration of Independence.”77 The project—part of a workshop with students at the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia—also included a proposal for public art at Philadelphia’s Independence Mall (Constellation, 2000), where Buster Simpson saw a great need for creative seating. Apathetic tourists, just checking off yet another must-see item, could sit down and talk: “Independence Mall is a gathering place for the public to reflect on an event of which we are now trustees.” Buster proposed “an amenity as a conceptual framework, which, when engaged with by the public, becomes a social catalyst reinforcing our collective image of the signing of the Declaration of Independence.”78

Or the almost whimsical Discombobulated Discourse (2015) in which two high-backed, ladder-like chairs on buoys face each other, at times bobbing “erratically,” reacting to changes in the [Duwamish] river’s water quality, as if discussing the issues of climate change that are the cause of their bewildered conversation.79 In the film documentation Real to Reel (1968-present) which is playing in the Project Gallery, the viewer can also watch the piece ‘being performed,’ as actors climb Discombobulated Discourse in an effort to perhaps ‘calm the waters’ through conversation.

example, also relates to the life-raft photo documentation discussed in the previous section. Chairs, like the Belltown Pans, are symbols of community involvement. We barely talk to each other anymore in person, around a table—or around a life-raft, for that matter. These chairs are a reminder of the necessity to engage in civic (and civil) dialogue about climate change. Bells call for us to ‘take a seat’ and talk.

Barrels/Oil Drums, Plinths.

The oil drums (aka barrels) in this exhibition are metaphors for all that is wrong with the apex of the Anthropocene: our voracious appetite for energy and plastic products derived from crude oil; the human-induced climate crisis leading, here, to the shrinking of rivers and lakes, there, to rising oceans and flooded habitats; the rapidly increasing number of climate refugees.

The oil drums are the bedrock of this exhibition.

The components of the sculptural assemblage Stick with Point (2016/2022) reveal Buster’s complex thought processes once again—interconnected, nonhierarchical, fluid. The plumes of an ancient Roman centurion’s helmet are conjured up by joysticks, the main control in military (and civilian) planes, and in gaming, ready to be plugged in. They are mounted on a contemporary, carbon-fiber U.S. military helmet, which is mounted on a missile that doubles as a Modigliani-like elongated head.80

In Float with Three Chairs (2016-2022), a chair has actually morphed into a ladder—or is it the other way around? Is the ladder a cipher for ‘escape’? Escape from the rising waters, literally and metaphorically? And why is the upper rung of the chair-ladder broken? Eliciting inquiry, curiosity and yes, wonder—Buster Simpson’s art resoundingly succeeds. Not to mention that all of his constructs talk to each other: Float with Three Chairs, for

Leaning against the plinth is a sharply triangular, large piece of dichroic glass, that changes colors in response to varying light conditions. Buster explains that this piece of glass is an oblique reference to Ishi, California’s “last wild Indian,” who lived in the anthropology museum at the University of California, Berkeley for three years.81 There, he “spent much of his time on display for white museum audiences, fashioning obsidian and

Float with Three Chairs, 2016-2022

Painted oil drums and powder coated chairs from Robert Rauschenberg Residency, Captiva Island, FL with student-produced Sandbags for Acknowledgement displaying the names of Utah oil fields

Stick with Point, 2016/2022

Joy sticks, Army helmet, and jet engine base with laminated dichroic glass and Sandbag for Denial

colored glass projectile points and recording Yahi songs and stories.”82 In conversation, Buster also mentioned the use of dichroic glass in older missile guidance systems which ties back to the (joy)‘stick’ in the title of the piece. Finally, the glass is poised on a sandbag, with more Utah oil field locations, including, again, that of Rozel Point.

How do war, anthropology and oil synchronize? How do the inevitability and ‘joy’ of war since times immortal, the exploitation of humans by humans and Big Oil line up? The answer, implicit and with a long view of history, is on another plinth. One that may be considered the crux of the entire exhibition. It’s the powerful Tin Box barrel (1989/1993/2021).

Andrew Jackson Blackbird—”Late U.S. Interpreter”83— wrote a history of his people, the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan, which he published in 1887. It contains the only known account by an Indigenous person of the smallpox genocide, brought to Blackbird’s people in a small tin box.84 The text on top of the barrel cites the moment when Blackbird’s kin opened the ‘gift’ from the white men, only to find “nothing but moldy particles” in the last little box. The printed text stops ominously, with the people, perplexed, closely investigating the mysterious little box. In his book, Blackbird continues: “But alas, alas! Pretty soon burst out a terrible sickness among them. The great Indian doctors themselves were taken sick and died [...] nothing but the dead bodies lying here and there in their lodges—entire families being swept off with the ravages of this terrible disease.”85

Tin Box is a ‘burn barrel’ rather than a plinth, and in that role it evokes imagery of fire: burning with the fire of high fever that starts the smallpox sickness; the burning of scraps by unsheltered people, warming themselves around a barrel; the burning of the Kuwaiti oil fields and even the post-apocalyptic scorching of the earth by fracking. It is both primeval and apocalyptic, it is history and future.

Tin Box, 1989/1993/2021

Burn barrel, zip ties, Hirshhorn Museum Faceplate installation remnant, laser-cut stainless steel drum head, drum ring, and video projection

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”86

Tin Box represents, as Buster puts it, “self-genocide”: The small box we ‘gifted’ to the First Peoples has “turned on us”—we are “preparing our own demise.”87

Conclusions.

What does Buster Simpson want us to take away from this exhibition?

“Make art part of the solution, not only of the conversation!”88

This, he has practiced—project by project, construct by construct. For the non-artists that most of us are, he has more humble expectations:

“The reward for all of us who make art in any context, public or private, is to witness the engagement by others, and that they find it worthy of their curiosity and study.”89

Expressed not so humbly, I would add the need to be and get informed, to take a stance and act on it, to face the music that “anthropogenic climate change [may] result in worldwide societal collapse or even eventual human extinction”90—but not to use this doomsday perspective as a pretext for inaction. No quick fixes. Instead, incremental revolution. Adding “a little to a little, it will eventually add up to something.”91 Community action for the common good. Civic activities that bring neighbors together for a common cause. Caring about your habitats. How they function. How they could be mended, healed. Creating our own ‘constructs for the Anthropocene’ to the best of everyone’s individual abilities—modest solutions, small steps, even if only in our backyards.

Buster has made “groundbreaking contributions to dialogues about the health of communities and the societal obligations of the artist.”92 He is never preachy (unlike this writer) and his art is firmly grounded in science

and fact-based evidence, but with that enticing ‘poetic’ quality to beguile the viewer: “You should feel a piece and if you want to go deeper, do it.”93

The most fitting conclusion, I feel, to these reflections on Constructs for the Anthropocene, is a brief analysis of two more projects.

Offering Cycle (2014), is a public artwork that was installed at a popular fishing spot in Anchorage, Alaska. It is a fish cleaning table with a “stainless steel gargoyle trough” in the shape of a salmon, through which the “entrails [...] with their vital nutrients” are given back to the ecosystem whence they came: “The cleaning of fish becomes a pedagogical public art performance and an act of offering back to the cycle.”94 In conversation, the artist added: “This interconnected practice has been intrinsic in Native cultures: giving thanks and giving back” and is practiced in their potlatch ceremonies. Offering Cycle once again joins utility with poetry.

Host Analog (1991) is a remarkable success story of habitat exchange. A six hundred-year-old Douglas Fir was felled, cut into parts, but ultimately rejected as lumber sometime in the 1960s. When Buster brings the log from the Mt. Hood wilderness into Portland almost thirty years later, it is already functioning as a nurse log. “Over time, the forest landscape growing on Host Analog has been diversified with urban plants selfseeding and taking root,”95 thus creating a hybrid of the natural and the urban—but only because the artist has vigilantly ensured the continuous health of this public art project.

Documentation of Offering Cycle, 2014

Archival Inkjet print

Public artwork with functioning fish cleaning table, Anchorage, AK

Both Offering Cycle and Host Analog are about giving back to ecosystems—aquatic and woodland—from which we have profited in order to satisfy our consumption-driven Anthropocene. The conclusion: it is all about giving back. No quick fixes. Only small steps, adding up to a larger whole. We cannot turn off the Anthropocene like we turn off boiling water, but, metaphorically speaking, we can turn down the temperature. Buster Simpson states it best:

“The Anthropocene Epoch is of our making and will require us all to transition creatively to an adaptive future that is both life-sustaining and poetic.”96

Dr. Angelika Pagel Professor of Art History, Weber State University

Notes:

1 John K. Grande, Art Space Ecology: Two Views - Twenty Interviews (Montréal/New York: Black Rose Books, 2019), 57.

2 Scott Lawrimore, ed., Buster Simpson: Surveyor (Seattle: Frye Art Museum, 2013), 22.

3 “What is Ecology?,” The Ecological Society of America, 2022, https://www.esa.org/about/what-does-ecology-have-to-do-with-me/.

4 Buster mentioned this phrase in relation to the title of an exhibition catalog on Russian Constructivism: Art into Life (Seattle: The Henry Art Gallery, 1990).

5 Conversations with Buster Simpson and Lydia Gravis.

6 “Manhattan Project Glass”, Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Debra Wilson, 2020, https://carnegiemnh.org/manhattan-project-glass/.

7 Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 91.

8 Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 45.

9 Conversations with Buster Simpson.

10

Suzanne Lacy ed., Mapping the Terrain - New Genre Public Art (Seattle: Bay Press, 1995), 277.

11 Lacy, ed. Mapping the Terrain, 278.

12

Compare the documentation of “Vertical Landscapes” in the Project Gallery.

13

See “Public Art Works” and “Environmental Projects” on Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/.

14 See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/artmasterplans/. Category name change pending.

15 See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/seattlegeorge/.

16

See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/anthropocenebeach/.

17

Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 97.

18 See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/danube/pdf/bustersimpson-danube.pdf.

19 Quoting from brainstorming sessions for the exhibition concept and borrowing a partial essay title by Charles Mudede,”Buster Simpson and a Philosophy of Urban Consciousness” in: Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 16.

20

“Soziale Plastik/Soziale Skulptur - Die Kunst im Leben”, Kultur Komplizen, 2021, https://kultur-komplizen.de/was-ist-eine-soziale-plastik/.

21 Will Steffen et al., “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?” Ambio, vol. 36, no. 8, (2007): 614–21, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25547826.

22 “The Anthropocene: A New Epoch of Geological Time?”, The Geological Society, May 11, 2011, https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/anthropoceneconf.

23 Steffen et al., “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?”

24 Steffen et al., “The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature?” This study uses “atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration as a single, simple indicator to track the progression of the Anthropocene” and has established that there has been a “Great Acceleration” of atmospheric CO2 “which has risen from 310 to 380 ppm since 1950, with about half of the total rise since the preindustrial era occurring in just the last 30 years” [as of 2007].

25 Luke Kemp et al., “Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios”, PNAS: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, (March 25, 2022), https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2108146119.

26

“Mangroves: 11 Facts You Need To Know”, Conservation International, https://www.conservation.org/stories/11-facts-you-need-to-know-about-mangroves.

27

“Reproductive Strategies of Mangroves”, Newfound Harbor Marine Institute, https://www.nhmi.org/mangroves/rep.htm.

28 The reports about the shrinking Colorado River are pervasive. See for example: Ian James, “Tensions grow over lack of water deal for the shrinking Colorado River”, LA Times, August 15, 2022; Leila Fadel and Luke Runyon, “A Water Crisis on the Colorado is getting worse”, KUNC, NPR for Northern Colorado, August 17, 2022, https://www.kunc.org/2022-08-17/a-water-cri sis-on-the-colorado-river-is-getting-worse.

29 Will Steffen et al.: “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet”, sciencemag.org, (February 13, 2015), https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/ scence.1259855. See also: “The Planetary Boundary System”, Stockholm Resilience Center, 2015, https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html.

30 See also Buster Simpson’s large-scale sculpture Divining (2020) at the Latta Nature Center in North Carolina: http://www.bustersimpson.net/divining/. Special thanks to Dr. Michael Wutz who suggested this ‘reading’ of Divining Agrarian.

31 Thomas Gainsborough: The Blue Boy (1770) and Thomas Lawrence: Pinkie (1794), both at the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Buster also recalls seeing prints of Pinkie and Blue Boy on his grand mother’s living room wall when he was a little boy.

32 https://www.azquotes.com/quote/580512

33 ‘Plinth’ is the term Buster prefers; it signifies the importance of his messages more urgently than the rather pedestrian ‘pedestal’.

34 More about the atom bomb and nuclear power: https://www.atomicarchive.com/index.html.

35 Terri Cook, “Travels in Geology: Gubbio, Italy: A geologist’s mecca.” Earth - The Science Behind the Headlines (September 21, 2016), https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/travels-geolo gy-gubbio-italy-geologists-mecca/.

36 “Poetic Utility” is a phrase Buster Simpson uses frequently for his public art and environmental projects.

37 See for example: Jaroslav Andel et al, Art Into Life—Russian Constructivism 1914-1932 (Seattle: The Henry Art Gallery, 1990). And: Jodi Hauptman and Adrian Sudhalter, Engineer, Agitator, Constructor— The Artist Reinvented 1918-1939 (New York: MoMA, 2020).

38 Vladimir Tatlin, for instance, called his paintings and installations PROUNs, an acronym that translates as ‘Projects for the Affirmation of the New’.

39 I am taking some liberties here with a phrase by Vladimir Tatlin when speaking about his corner-sculptures to which he referred to as ‘real materials in real space’. The original Russian for “Real materials in real space” is cited in Jaroslav Andel: Art Into Life—Russian Constructivism 1914-1932, 170.

40 Conversations with Buster Simpson.

41

“L.C.Smith: The Gun That Speaks for Itself”, L.C. Smith Collector’s Association, https://www.lcsmith.org/.

42 Karen Y. Cooney, “Triggers to Typewriters: The story of L.C. Smith, Gunmaker”, The Central New York Business Journal 33, no.21 (2019), https://www.cnybj.com/triggers-to-typewritersthe-story-of-lc-smith-gun-maker/.

43 Incidentally, the L.C. initials (Lyman Cornelius Smith) also double as Buster’s given first names, Lewis Cole.

44

Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 22.

45 Ibid.

46 Conversations with Buster Simpson.

47 Ellen Stevens et al, “Filter Fence Design Aid for Sediment Control at Construction Sites”, Environmental Protection Agency, EPA 600/R-04/185, September 2004.

48 Conversations with Buster. For more on Ukrainian efforts to protect their public art see: Lauren Frayer and Claire Harbage, “Ukraine scrambles to protect artifacts and monuments from Russian attack”, NPR, March 15, 2022, https://www.npr.org/sections/pictureshow/2022/03/15/1086444607/ukraine-cultural-heritage-russia-war.

Jason Farago, “Rescuing Art in Ukraine with Foam, Crates and Cries for Help,” New York Times, August 8, 2022.

49 Curator and Gallery Director Lydia Gravis in conversation.

50 Sarah Rose Harp: “After 50 Years, Michael Heizer’s Colossal Desert Installation Is Finally Finished.” Hyperallergic, August 22, 2022, https://hyperallergic.com/755135/after-50-years-mi chael-heizers-colossal-desert-installation-is-finally-finished/.

51 Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 25.

52 The Fragile Paradise, Gasometer Oberhausen, Germany, until December 30, 2022.

53

Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 23.

54

Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 41.

55 Jack Flam, ed., Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 101.

56 Tommy Orange: There There (New York: Vintage Books, 2018), 11.

57

Charles Mudede: “Buster Simpson and a Philosophy of Urban Consciousness” in: Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 16.

58 Inspired by Charles Mudede’s essay (ibid), specifically page 17.

59 Two dams in Washington State have indeed already been decommissioned: Elwha Dam in 2011 and Glines Canyon Dam in 2014. As of summer 2022, there is also talk about decommis sioning Glen Canyon Dam in Utah.

60 Conversations with Buster Simpson. In Migration Blockade the gnome-like cone is actually the top of a machine that makes computer chips.

61 “Shasta Dam Construction”, Northern California Bureau of Reclamation, (3/24/22), https://www.usbr.gov/mp/ncao/dam-work.html.

62 John Waldman, “Blocked Migration: Fish Ladders On U.S. Dams Are Not Effective”, YaleEnvironment360 (April 4, 2013), https://e360.yale.edu/features/blocked_migration_fish_ladders_ on_us_dams_are_not_effective.

63 See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/showsandinstallations/pdf/bustersimpson-belltownpan.pdf.

64

Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 63.

65 See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/treeguards/.

66 Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 51.

67 Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 63.

68 See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/showsandinstallations/pdf/bustersimpson-belltownpan.pdf.

69

Ines Hajdu, “Disc Harrows: Powerful Farm Equipment for Soil Preparation”, AGRIVI, 2022, https://www.agrivi.com/blog/disc-harrows-powerful-farm-equipment-for-soil-preparation/. The Palouse is a distinct and significant wheat growing area in Eastern Washington.

70 Neil Gunningham, “Averting climate catastrophe: Environmental activism, extinction rebellion and coalitions of influence.” King’s Law Journal 30.2 (2019): 194-202. https://www.tandfonline. com/loi/rklj20.

71 See exhibition list item #45

72 Storm Simpson, “Proudly South African: The origin of the dolos”, cape(town)etc, (November 5, 2020), https://www.capetownetc.com/cape-town/proudly-south-african-the-origin-of-thedolosse/.

73

See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/cradle/.

74 Srishti Singh Sisodia, “What are Czech hedgehogs?: Homemade obstacles that can destroy Russian tanks”, WION, (March 5, 2022), https://www.wionews.com/photos/what-are-czechhedgehogs-homemade-obstacles-that-can-destroy-russian-tanks-459254#what-are-czech-hedgehogs-459228.

75Thomas C. Chidsey and Sharon Wakefield, “New Oil and Gas Fields Map of Utah - Just the Facts!”, Utah Geological Survey, vol.26 no.3 (July 2004), https://geology.utah.gov/map-pub/ survey-notes new-oil-and-gas-fields-map-of-utah/

76See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/risingwaters/pdf/bustersimpson-risingwaters.pdf.

77See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/showsandinstallations/pdf/bustersimpson-templegallery.pdf.

78Ibid.

79See Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/discombobulateddiscourse/.

80Amedeo Modigliani (1884-1920). During the installation, Buster also referred to the sculpture as “G.I. Joystick”. This title in particular lead me to think of Kubrick’s 1964 “Dr.Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb”—with its famous ending of Dr. Strangelove joyously riding the bomb, like a cowboy on a bucking horse, bringing atomic bliss to the world.

81Laura Smith, “Into the Ishi Wilderness”, California Magazine (Summer 2022), 26-31.

82“Ishi”, Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology (2017), https://hearstmuseum.berkeley.edu/ishi/.

83Andrew J. Blackbird, “History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan”, Project Gutenberg (November 1, 2004), https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/6988/pg6988-images.html.

84“While the quasi-homophone ‘small pox/small box’ works in English, in an ironic linguistic twist, the English word ‘small pox’ and the Ottawa word for ‘small box’ were considered to be identical and were thus translated by the same Ottawa word.” See: Christian Feest, “Andrew J. Blackbird and Ottawa History”, Yumtzilob 8 (1996), 114-123, https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/263851830_ssAndrew_J_Blackbird_and_Ottawa_Histors.

85Andrew J. Blackbird, “History of the Ottawa and Chippewa Indians of Michigan”, Project Gutenberg, chapter 1, fourth paragraph.

86William Faulkner: “Requiem for a Nun”, 1951, quoted in: Smith, Laura: “Into the Ishi Wilderness,” 27.

87Conversations with Buster Simpson.

88Conversations with Buster Simpson.

89John K. Grande, Art Space Ecology: Two Views - Twenty Interviews, 59.

90Kemp, Luke et al. “Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios.”

91Lawrimore, Buster Simpson: Surveyor, 23.

92John K. Grande, Art Space Ecology, 51.

93Conversations with Buster Simpson.

94Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/offeringcycle/.

95Buster Simpson’s website: http://www.bustersimpson.net/hostanalog/.

96From Buster Simpson’s Artist Statement for this exhibition.

Double Boiler, 2011

Glass salmon egg, double boiler pan, and metal hot plate

Exhibition acknowledgements:

This catalogue was produced and published on the occasion of the exhibition Buster Simpson: Constructs for the Anthropocene at:

Weber State University

Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery

September 2 – November 5, 2022

The exhibition was organized by the following individuals, in collaboration with the artist:

Lydia Gravis, Director of Art Exhibitions & Public Programs

Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery

Molly Painter, Exhibitions Manager

Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery

The following individuals made this exhibition possible through their help and expertise:

Molly Painter, Exhibitions Manager, Dr. Angelika Pagel, Catalogue Essayist and Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History, Lydia Gravis, Director of Art Exhibitions and Public Programs, Mariah Smith, Zayne Wilcox, Jessica Lewis, Ember Brandt, Claire Safeer, and Julianne Ramanujam, Shaw Gallery Assistants, Andrew Rice, Printmaking Instructor, K Stevenson, Professor of Printmaking, Paul Crow, Department Chairman and Professor of Photography, Jason Manley, Professor of Sculpture, Rachel Posadas, Graphic Designer, Jordan Howland, Curatorial Consultant, Joe Freeman, Exhibition Photographer and Installation Contractor, Starr Sutherland, Video Editor, Lynn Thompson, OJ Zamora, and Troy Bell, Facilities Management, Mark Ashby, Instructional Technology, Jeremy Stott, Digital Media Lab Director, Camela Corcoran, Art Elements Manager, Brooke Whitaker, Catalogue Designer, Dr. Michael Wutz, Copy Editor and Brady Presidential Distinguished Professor of English, Dr. Michele Culumber, Professor of Microbiology, Carly Biedul, Coordinator at the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College, Dr. Bonnie Baxter, Professor of Biology and Director of the Great Salt Lake Institute at Westminster College.

This exhibition was made possible through generous support from:

Utah Division of Arts & Museums, Weber County RAMP Tax Initiative, Mark E. & Lola G. Austad Endowment for Visual Arts, Val A. Browning Foundation, Lawrence T. & Janet T. Dee Foundation, Weber State University College of Arts & Humanities, Jim & MaryAnn Jacobs, and Jack & Bonnie Wahlen.

Fever to Tell (detail), 2014

Confetti & Distress / Honey & Suspicion

Thank you to Buster Simpson for sharing his work with the Northern Utah community through this timely exhibition at the Mary Elizabeth Dee Shaw Gallery at Weber State University.

September 11 - November 21

Public Opening Reception Sept 11, 7-9 pm

Buster Simpson. Voxel Frog as Environmental Action, 2022. Rozel Point, UT. Photo: Jordan Howland bustersimpson.net

Buster Simpson. Voxel Frog as Environmental Action, 2022. Rozel Point, UT. Photo: Jordan Howland bustersimpson.net