NEWARK SCHOOL OF VIOLIN MAKING

THE FIRST 50 YEARS | 1972-2022

Edited by Helen Michetschläger www.lutherieuk.org

Edited by Helen Michetschläger www.lutherieuk.org

1

·

| The history of Newark School of Violin Making

18 | Students at NSVM 1972-2023 38 | Life after Newark 40 | Map: Representation of former Newark students worldwide 42 | Staff at NSVM 1972-2023 44 | Timeline: Major dates in the history of the school

CONTENTS 04

by Ariane Todes

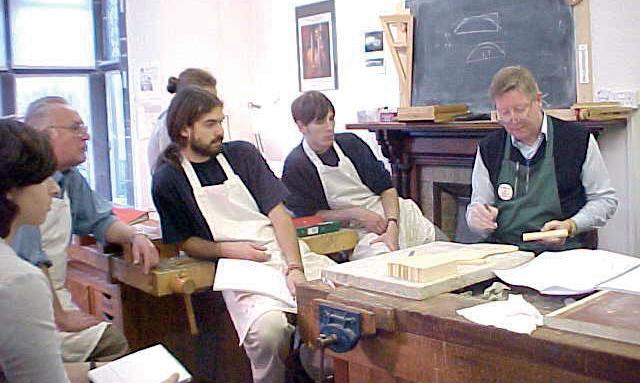

Autumn 1976 main workshop

The Lutherie 2023 conference in Newark celebrated 50 years of Newark School of Violin Making. This written history grew out of conversations with my friends Tim Southon and Nicky Terry as we were planning the event.

We wanted to put on record what the school has stood for over the years; the huge influence it has had on violin making in the UK, Europe, America and Asia. When I was a student in the 1970s, a professional violinist neighbour told my mother that you couldn’t make a living from making violins. Thanks to the opportunities offered at Newark, countless former students have proved her wrong.

The position of the school has had precarious moments through its history, as its management has passed between different institutions and there has been doubt about whether it could continue to use the beautiful former Westminster Bank. I hope that this booklet might provide some inspiration from the past, reminding us how Maurice Bouette helped raise the necessary funds to refit the building when the school moved into it in 1977.

Newark students are represented in every field of the violin world; as makers, repairers, restorers, dealers, bow makers. The majority are self-employed, some work for shops, and some have set up shops and dealerships, large and small, employing others. Some former students have moved sideways, making high quality accessories or in allied fields such as making harps, guitars or early instruments. But even those who have chosen a totally unrelated career remember their time at Newark with warmth and gratitude.

Many thanks are due to all the former students and tutors who have responded to my many emails and who have sent photographs, press cuttings and information; the list is too long to print.

Helen Michetschläger Editor, Manchester 2023

www.lutherieuk.org

50 years of NSVM · 3

THE HISTORY OF NEWARK SCHOOL OF VIOLIN MAKING

BY ARIANE TODES

BY ARIANE TODES

In the beginning, there was Newark – or Newerche as it was written in the 1086 Domesday Book. A town on the River Trent in Nottinghamshire, England – probably Roman – which grew as a centre of the wool and cloth trades in the 12th century and served as a battle ground between Royalists and Parliamentarians during the Civil War in the 17th. Indeed, many episodes in the great sweep of British history played out in the town. Perhaps the most surprising one is its role as the epicentre of British violin making and its influence on the entire world.

ORIGINS

Today’s school originated in the pioneering School of Science and Art, which opened on 5 September 1881, and which after several iterations and expansions, became Newark Technical College, or ‘The Tech’ in 1961. A growth spurt in 1970 led to many new courses and

in 1971 the Principal, Eric Ashton, decided to create the UK’s first ever violin-making school. An advertisement was placed in The Strad and in September 1972 The School of Musical Instrument Crafts opened its doors to 12 students, under the direction of Maurice Bouette.

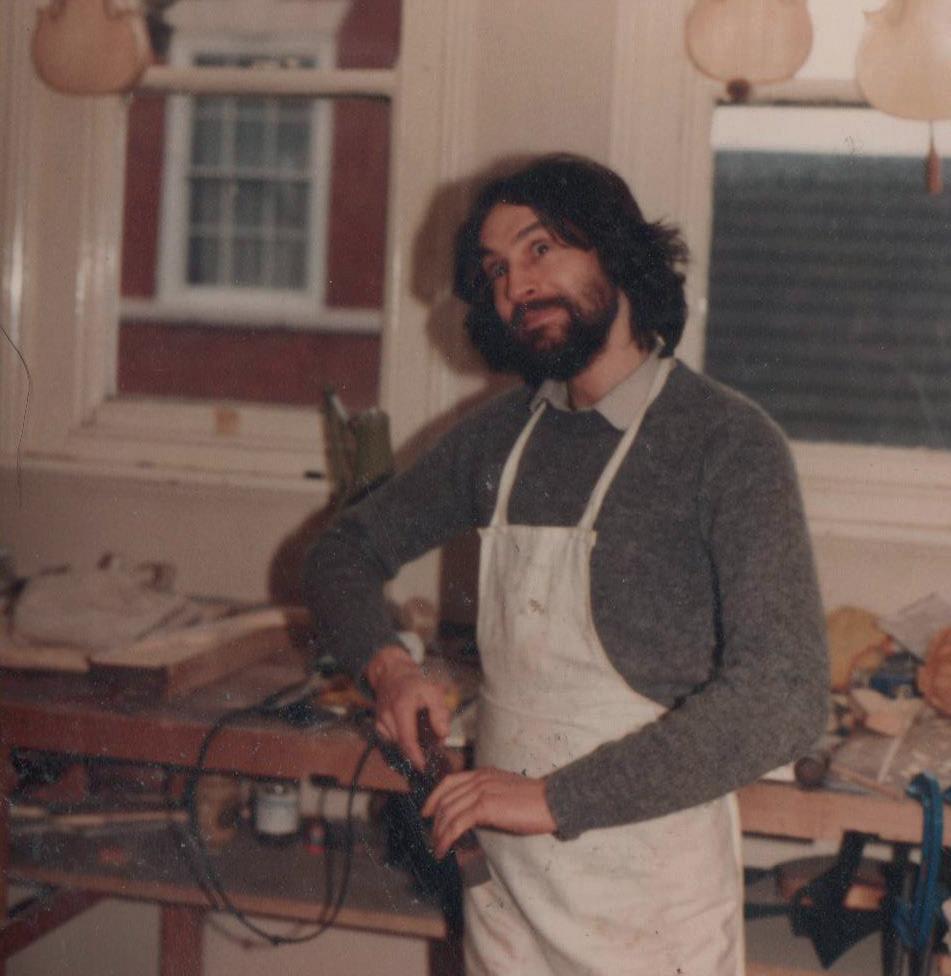

MAURICE BOUETTE

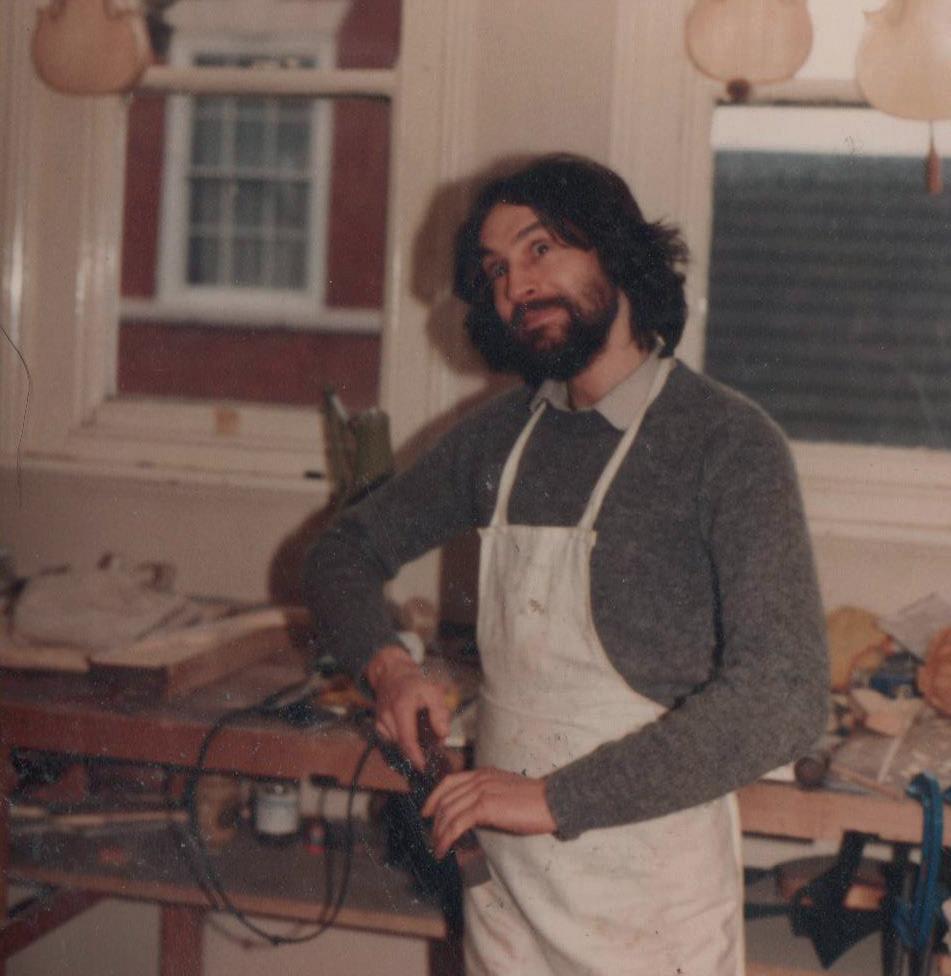

Maurice Bouette was born in 1921 to a musical family, his father a saddler. After the war Maurice ran a television show room and only became interested in violin making at the end of the 1950s, enrolling on William Luff’s evening classes in Ealing and Northwood. He eventually took over Luff’s class himself in 1962. He also had a business selling wood, fittings and tools, and was immersed in the violin trade.

Perhaps it was fate that he took on the job of creating the new school at Newark. According to what he told Mary Anne Alburger in her 1978 book The Violin Makers – Portrait of a Living Craft, he had already been thinking of something similar when he received a visit from Stephen Fawcett, Head of Music at

50 years of NSVM

Newark Technical College, scouting for him to take on the new school. Bouette was conflicted at the time, though: ‘I had felt for a long time that it was absolutely essential for England to have such a school, and had thought often of starting one for myself… The crux of the matter was that if Newark Tech. did start it, who would teach there? Anyone who was happy in his life and earning a reasonable living at violin making as I was would not want to relinquish all that to take up a teaching post elsewhere, so we just left it like that, with me still teaching at evening classes.’ It was only when he saw the advert that he resolved to make the sacrifice, applying successfully for the job and moving to Newark.

LOCATION

The first premises were in the disused Mount School, away from the main college, with only two workshops and a varnish room. The violin makers were on the first floor, above the piano tuning course and on the other side of a courtyard from the wind instrument course.

Eventually, a building belonging to Westminster Bank became empty – a three-storey Victorian building designed in 1886 by Watson Fothergill in early Italian Gothic style. In 1976 Bouette appealed to the Chairman of Nat West to lease it to the Education Authority. Having eventually raised the £8,000 required to develop the building, with the help of Yehudi Menuhin, Charles Beare and Desmond Hill, the Newark School of Violin Making opened in Kirkgate.

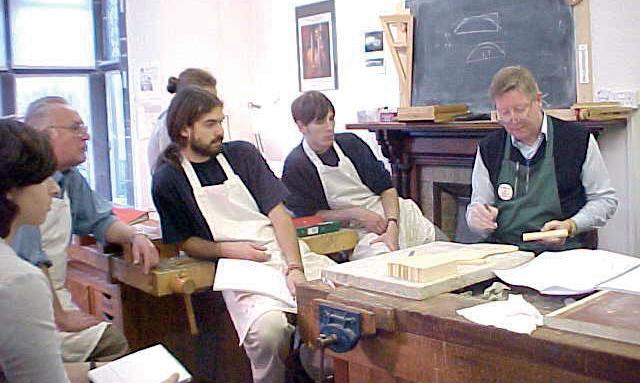

FOUNDING STAFF

Bouette initially brought in Glen Collins to help run the course. Collins was the nephew of William Luff and after working at Guivier’s for several years, he bought his uncle’s shop. When Bouette invited him to Newark, he sold up and moved north. The third member of the team, Wilfred Saunders, was largely self-taught, coming to violin making through joinery. He studied with Arthur Richardson, whose Tertis viola model he developed, going on to make instruments for Tertis himself, as well as Peter Schidlof.

50 years of NSVM · 5

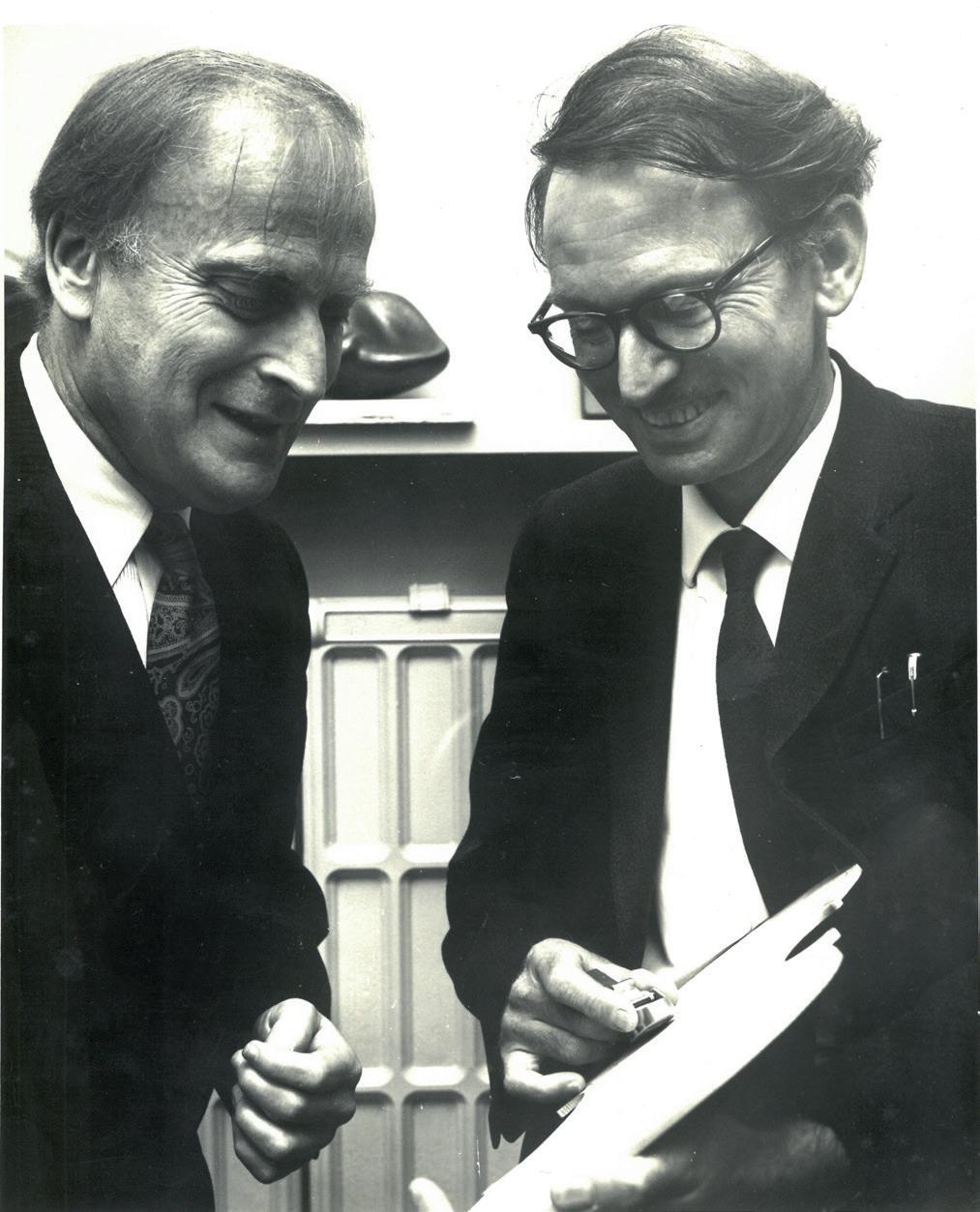

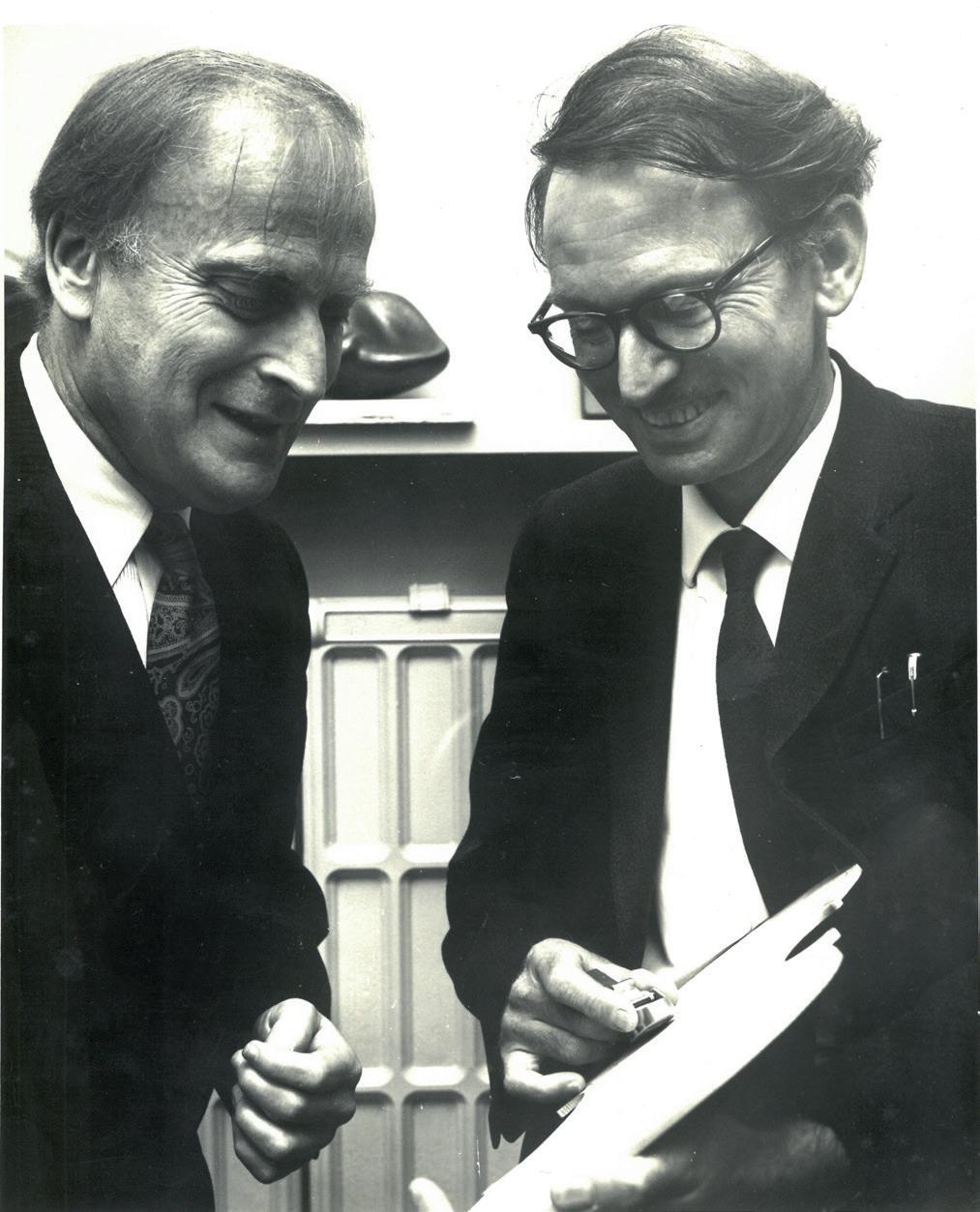

Maurice Bouette

Maurice Bouette & Glen Collins

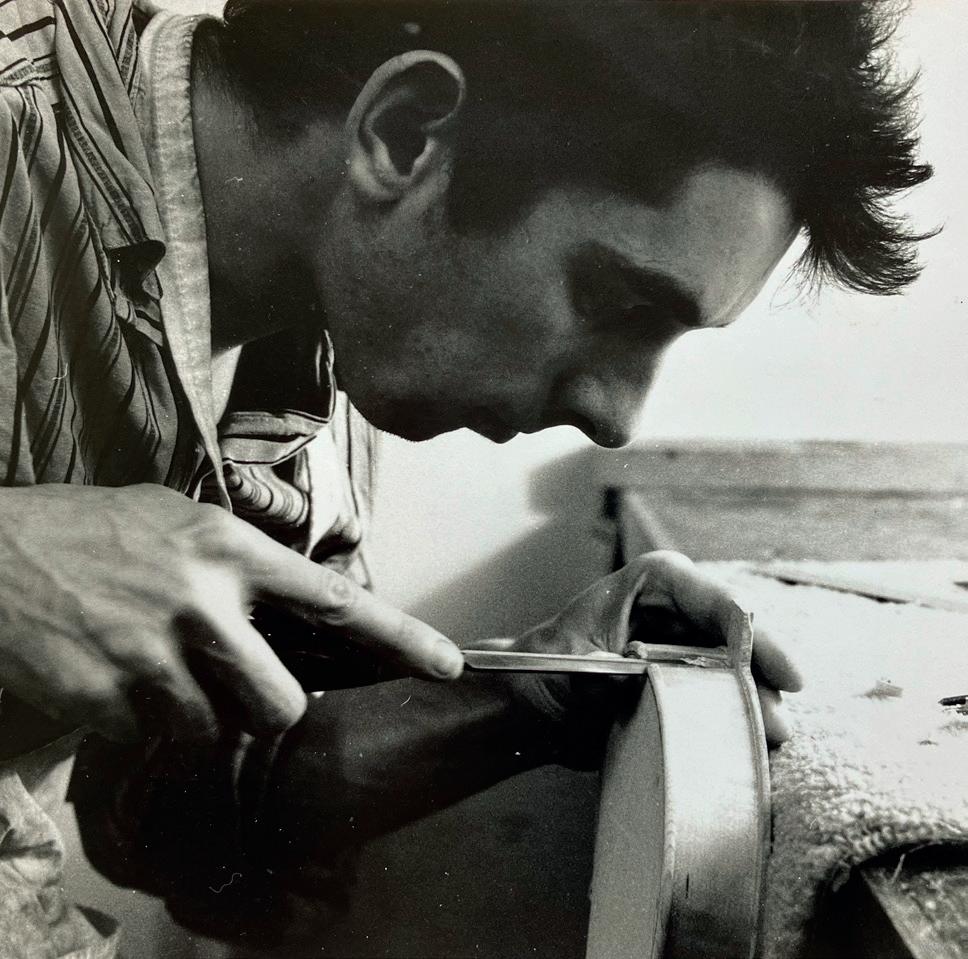

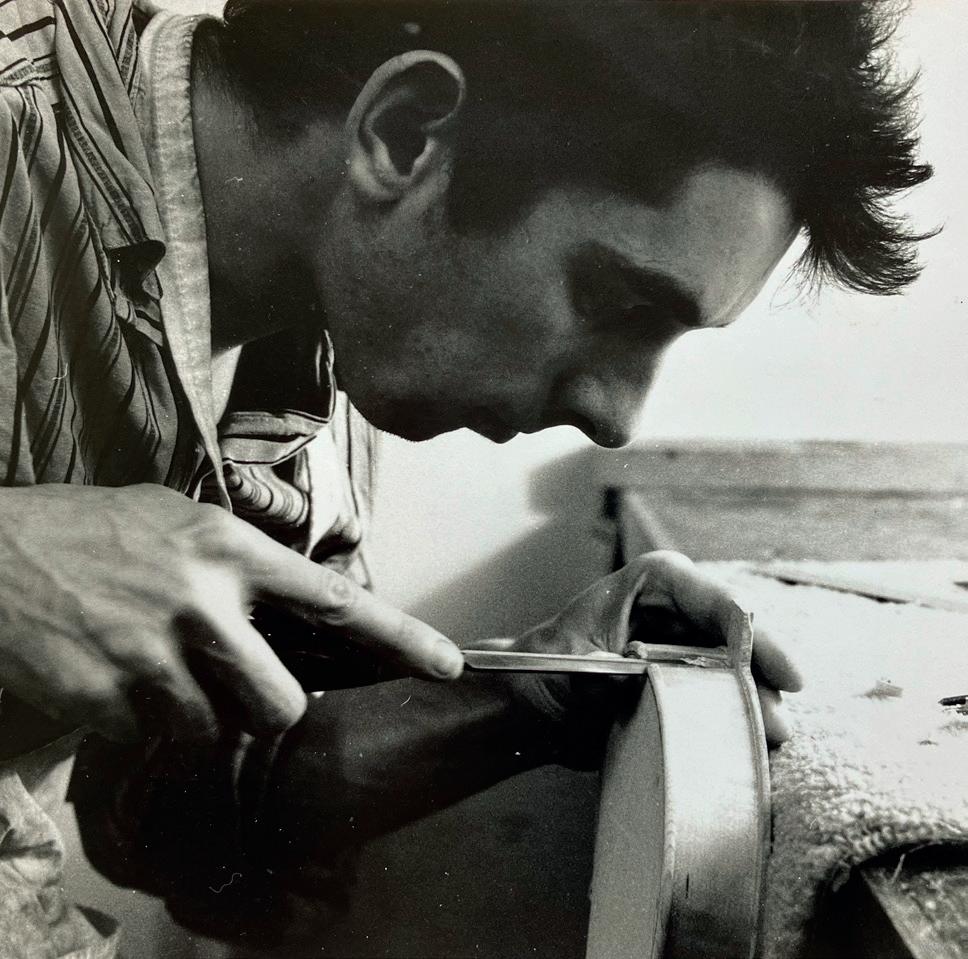

Wilf Saunders

Robert Payn

Bouette’s hopes for students were visionary but also pragmatic, as he described to Alburger: ‘When they leave us, if they are any good, they are capable of going out to any workshop and earning money for their employers immediately, which is what I want. I do expect everyone who leaves to be able to get a job and earn a living, and this has proved to be the case. I do not think that many are going to make their livings solely by making instruments, as they have to be exceptionally good to do that, but there are a few who will. I think also that with an increasing number of good instruments available, the world will become more selective about what it accepts and finally only the best instruments will be welcomed. These must sound good, look classical and be well finished, so that they look beautiful, with flowing lines; this will always give them the edge over something mediocre. Musicians are used to seeing instruments which look classical, and want to find something which looks similar, and I think that is what one should try to make.’

As The Strad put it in 1977, ‘The aims of the school are to furnish the trade with skilled craftsmen who can confidently restore any instrument from a genuine Italian masterpiece to a Chinese outfit, and to produce good hand made instruments. Thus the classical models of the past are preserved, the utilitarian needs of the present are satisfied and the foundation of a healthy stock of fine instruments for future generations of musicians are laid.’

TEACHING STYLE

Bouette espoused a certain discipline and precision of craft, as he described to Alburger: ‘At the school I must be able to say that something does not fit if it really does not, and there be no question about it, so that it is possible to demonstrate an error. I am not being awkward about this, it is just one of those things where one must learn to be absolutely precise. The method that we use lends itself to this kind of demonstration. If students can do a job functionally to start with, they can do anything they like afterwards. A student in his first year will make something that will look perfect to him. He will look back at it six months later and say that it is horrible, because he begins to see the bumps and irregularities. To educate the eye, you just keep looking, but you do need someone looking over your shoulder to point these things out.’

It was far from perfectionism, though: ‘Precise workmanship does not necessarily make the best instruments. In fact, something which is completely symmetrical does not appeal to me at all, and perhaps that is why I prefer Guarneri to Stradivari, who is so perfect. If one sits opposite the cathedral in Cremona and looks up at it, nothing is symmetrical. There will be five windows on one side and four on the other. The door is not in the middle and the statue over the top is just off centre. I have no idea how it happened, but it looks wonderful. When I first sat there I did not notice it, then after a while I just could not help looking at it because it was so beautiful. I think that it is the same with instruments.’

Is there a Newark style that can be detected just by looking at an instrument? Julie Reed Yeboah believes so and describes it: ‘The style was one of perfection in purfling corners and arches and all of these details. Instruments came out looking like 19th century French, with clean edges, nice purfling and uniform varnish, with an influence from the German school, although different from Mittenwald, but there was still this super-cleanliness.’

50 years of NSVM · 6

AIMS

50 years of NSVM · 7

Violin by John Molineux, the first violin to be completed at the school

CURRICULUM

The initial course ran for two years and as well as instrument making, students also took broader subjects such as Music Appreciation, Music History, Technical Drawing, Acoustics, Business Studies, Woodwork, Metalwork and Silversmithing, and learnt to play an instrument.

In 1974 the course was extended to three years. The first involved making violins to a specific pattern; the second introduced fitting up, varnishing, restoration, repair and bow rehairing; in the third year the students could opt to specialise in making or repairing, and then made their final Test Instrument in the six weeks during the summer term.

In 1992 a two-year baroque instrument course was introduced by the then course director, Robert Payn, running for a few years. The 1993 intake all opted to swap to the violin making course after one year, and the course largely evolved into the foundation course which started in 1994. This was an option for those who joined the course with no previous woodworking experience, and the students made a flat-backed viola d’amore as an introduction to the necessary skills, a development of the ideas from the early instrument course. 1995 saw a doubling of course numbers, an expansion that was opposed by the trade but in practice didn’t have a significant effect on the numbers who went on to get jobs, although there was a slightly higher dropout rate.

In 2017 Lincoln College turned the course into a threeyear BA (Hons) degree in Musical Instrument Craft validated by the University of Hull, as well as continuing the Foundation Course and evening classes. The first year of the BA offers modules on Anatomy and Design, Basic Techniques, Workshop Practice, Making Specialist Tools, and Historical and Contextual Studies. In second year students learn Applied Acoustics and Problem Solving, with optional modules on repair and finishing. In their final year, they work on Business Practice, Advanced Craft Technique, Professional Standards, and their Final Major Project.

EXAMS

Before the BA and its component exams was introduced, the final optional qualification was simply to make a test instrument set up in the white during the final term. Initially, this could be any model and was marked by the staff, but as the course became more formal, Charles Beare and subsequently Peter Beare came up to adjudicate, and and students would have to make a golden-period Stradivari for consistency. In recent years the students have also made a pre-test instrument in their third year.

ACCOMMODATION

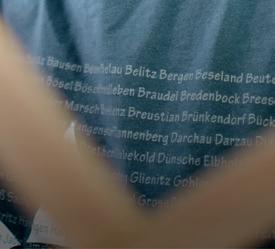

The student house at 28 Parliament Street was home to generations of violin makers. Julie Reed Yeboah was in the first year of tenants and recalls the cold and the once-a-week baths. It was she and her peers who bought the famous table, she remembers: ‘We had to buy our own furniture, and used to go to the Wharf, which was a weekly auction. We bought the table there for two pounds and used it as our kitchen table.’

Nearly 30 years later, the kitchen table was still there and had become iconic. Sally Mullikin lived in Parliament Street in her second and third years and remembers: ‘The table was in the kitchen and every violin making student who had lived there had carved their name or initials into it. I would eat breakfast every morning and look at names like Roger Hargrave or John Dilworth, and all these other people I’d heard of. It made me feel like I was part of this legacy of Newark, which was really exciting.’

The other main accommodation was the Presbytery. Andrew Finnigan spent his first year there and remembers: ‘It was like a villa, with lots of rooms. At any time there were about 12 or 13 students living there. It was very social and once a week we cooked a massive meal together. Everybody chipped in with ingredients and helped and we sat round the big table. It was usually some sort of tomato sauce and noodles –nothing special – but it was nice to be able to do that.’

50 years of NSVM · 8

THE FIDDLE RACE

The famous Fiddle Race goes back to 1979, when students had the idea of teaming up to make a violin in 24 hours. Helen Michetschläger recalls the first race, ‘The violins were made in a great rush and our team’s instrument was really rough. One student slipped with his gouge while cutting the scroll and had to go to A&E for stitches. In subsequent years the students learnt how to pace the work and the quality really improved. For a while they made small instruments to use up some of the undersized wood.’

In recent years, the rules have become more sophisticated, with each team led by a final-year student and including colleagues from different years. The brief now also includes a theme, allowing makers to experiment with ideas and materials – recent ones have included culture, radical design. At the 2020 race student Kyle Schultz told the Newark Advertiser: ‘The fiddle race is just pure fun. It is something extremely creative that we would not normally get to do. Usually our making is very precise and takes months, but this event forced us to think about what’s important, be it quality, overall finish or sound.’

50 years of NSVM · 9

Fiddle Race 2018

The first prospectus

Table from 28 Parliament Street, photo credit Aidan Closke Final year celebratory dinner at the Presbytery, 1989

IN THE MEDIA

IN THE MEDIA

The school has had a healthy relationship with the local Newark Advertiser, which often features stories about students and the school’s initiatives and problems. In the school’s first year, the paper published a story on the first instrument to come out of the school (above a review for the new James Bond film, From Russia with Love) which had been made by John Molineux and was played in Newark Parish Church by fellow student Ron Vaughan. College principal Eric Ashton was quoted as saying, ‘This is a significant moment in the history of music and in the world of violin making.’

Students have also been featured on television several times. In 2011, students from the school took part in Scrapheap Orchestra, in which they had to scavenge scrap to make instruments to be played at in a performance of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture in the BBC Proms, with the process documented on screen in Scrapheap Orchestra on BBC4. They made 12 violins and 4 violas as part of the challenge, using junk such as drainpipes, cutlery and CDs. Tutor Andy Wheeldon told the Newark Advertiser, ‘There were some times when things went really well and others when they didn’t. We were under a lot of pressure because we had only 11 weeks to make these instruments out of scrap. Usually it would take that long to make one clarinet. It was a very novel challenge, and also a fascinating insight into how TV programmes are made.’ Due to popular demand, the instruments went on to be played at Glastonbury.

In 2021, BBC’s Antiques Road Trip visited the school, with expert Catherine Southon being given a tour of the school and joining students learning how to bend a violin rib, and student Angelo Muller performing on one of his own instruments.

50 years of NSVM · 10

COMPETITIONS

A number of Newark students have taken part in international violin making competitions over the years. The first ever prize winner was Ian Clarke, who won silver for a viola at the Cremona Triennale in 1976. Roger Hargrave’s college cello won gold in 1979. The Manchester International Cello competition in 1992 saw Andrew Finnigan receive a Certificate of Merit, and the Student Prize at the 2004 BVMA International Violin Competition was won by Damien Sainmont.

CHARITY WORK

Students have often put their knowledge and time to the service of good causes. In 2008, seven instruments that were made during the Fiddle Race were sent to Haiti, under the auspices of Luthiers Sans Frontières, with Robert Cain and two students

spending two weeks there doing repairs and teaching repair skills. The relationship with Luthiers Sans Frontières has continued, with other countries including the Philippines and Antigua, and in 2013 Robert Cain spent two weeks in Kabul working at the Afghanistan National Institute of Music. In 2018 Cypriot student Marios Pavlou responded to the plight of Syrian refugees by setting up the Hope Project, a friendly competition for fellow students to team up to make four instruments that would be auctioned to raise money for Anera, a charity supporting refugees on the island. The finished instruments were played by Jennifer Pike and judged for craftsmanship and tone. The winning violin was sold at auction by Tarisio.

In 2019, the school hosted visitors from Music Fund, which collects spare musical instruments around Europe, repairs them and sends them to countries that have need of them.

50 years of NSVM · 11

Andrew Finnigan Cello 1992

LSF in the Philippines 2022

Hope competition winning violin

MAKING MUSIC

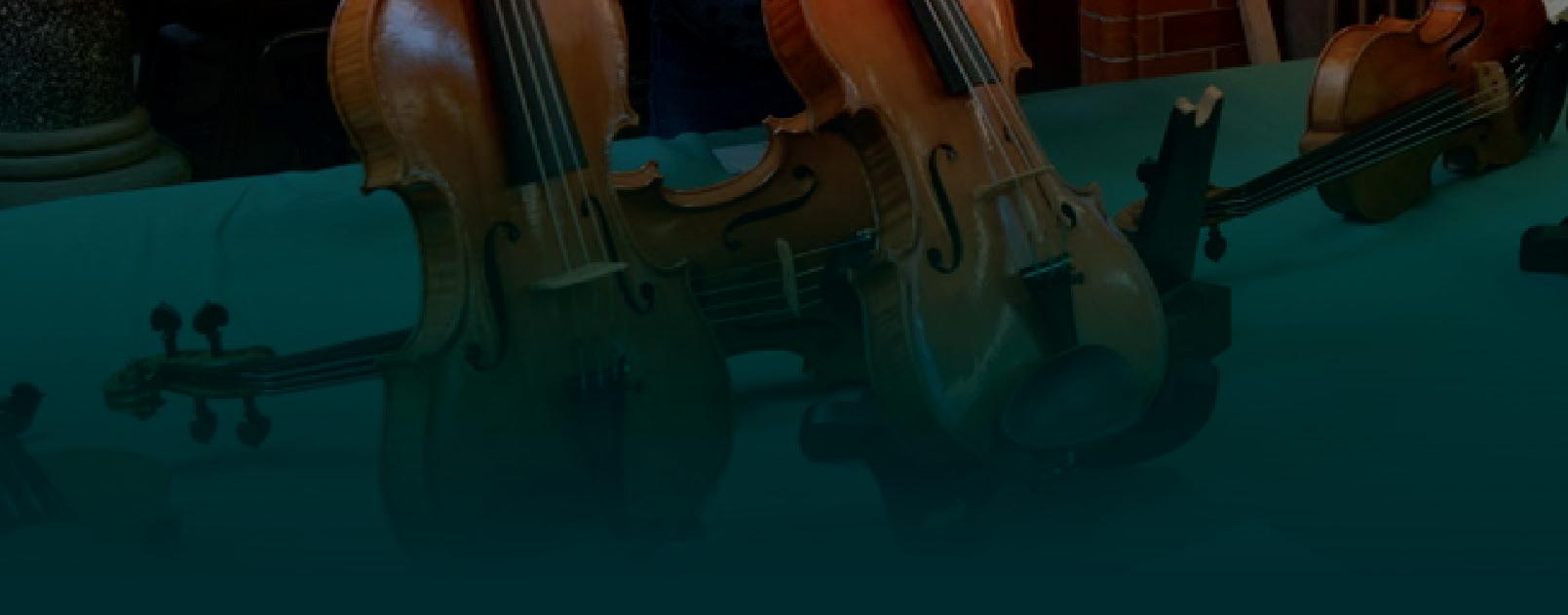

As one would expect from a community that produces noise-making machines, music performance has often been an integral part of the Newark experience. The initial syllabus included instrumental lessons and music appreciation classes. In the early days, the ground floor of the building hosted the Music Preparatory Course, for sixth-formers planning a career in music, so violin making students taking Music Theory and Acoustics classes mixed with the musicians. There was an orchestra for the whole college, in which some students took part. The students often took it on themselves to set up groups. In 2002, student Catherine Janssens set up the Trent Chamber Orchestra, with colleagues from the school directed by Roger Bryan, music director of Newark Parish Church. The orchestra was later renamed the Trent Chamber Academy. Ceris Jones remembers, ‘Most of the string section was from the violin school, so we developed the idea that we would all play an instrument that had been made in the school. Peter Smith called it “The Newark Sound”. We started putting on concerts every year for the Lutherie weekend, and during the interval all the instruments would be displayed showing the name of the maker and the player, often the same person. It was always a panic to get everything ready in time, and quite a few instruments were still in the white especially cellos! For me it just summed up the spirit of the school.’

Hanna Bozzetta (then Stumpfl) was in the orchestra and says: ‘After a full day working, you would grab something to eat quickly and then have two hours of rehearsal. It was intense, but people really wanted to make music together, which made it work, even if it was a long day. We’d usually find a solo piece with a young soloist from Birmingham conservatoire or from the violin-making school and a symphonic piece. We would hang posters all over town and everyone who was interested in classical music would show up. It only happened once or twice a year, so a lot of people in town were excited and also very supportive.’ As recent years have seen a sharp decline in student numbers, there are no longer enough players to support an orchestra.

50 years of NSVM · 12

OPEN HOUSE

The school often receives musical visitors, both to play students’ instruments and to demonstrate their own fine models. Yehudi Menuhin himself celebrated the opening of the Kirkgate building in 1978, touring the building and playing unaccompanied Bach on an instrument made by Michael Byrd. A newspaper report quotes him as saying: ‘It is a wonderful occasion to see the symbol, the temple of the contemporary world, a bank, turned to such idealism. It is almost on a par, but not quite, with the greater use of churches for music. This was Mammon. Now it is God… We need more people to spend their lives in this way rather than those who are always out to amass a fortune or get ahead of the next man and do not contribute their gifts to society. We live in a world that insists on having new things. This school is restoring the balance between things that are loved because they are beautiful and old and things that are required because they are new and serviceable.’

Students have also had a chance to see the 1695 ‘Lincoln’ Strad, owned by the City of Lincoln and on

loan to the leader of Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra. In 2008, then-guest leader Paul Barritt brought it to the school and remembers: ‘I was expecting to take it around the students one by one to let them see such a wonderful instrument at close quarters. When I arrived there was a full hall awaiting a talk and performance, and cameras too. I described the difference that such a violin makes to a player, which seemed the most relevant information, and the fact that it doesn’t sound particularly loud close to you, you knew it would carry to the back of any hall in any circumstance. This fact alone gives a player extra confidence. I found the place was full of energy and interest.’ In recent years, Jennifer Pike has visited the school, and played the final instruments of the Fiddle Race in 2019.

From the early days, there were also exhibitions and festivals, with Maurice Bouette opening up his house for the Festival of Violin Making. In 1998 Robert Cain started the annual Lutherie Day, held in the Barnbygate Methodist Church, which brings in experts from around the world to offer sessions on a variety of violin making topics for both students and the public.

50 years of NSVM · 13

Yehudi Menuhin and Maurice Bouette

Jennifer Pike

ROYAL RELATIONS

The School has had several brushes with royalty, including in 1982 with the then Prince of Wales. As part of celebrations for the centenary year of Newark Technical College, Glen Collins wanted to make the cello-playing Prince his own instrument, a historical echo of the cello made by William Forster in 1790 for the Prince of Wales, George Frederick. Following a performance on the cello as part of a concert in Newark Parish Church, the Prince was presented with the instrument, which was displayed alongside the Forster. In his speech, Charles said that he was touched and grateful for the gift and promised to cherish it for many years, and that ‘The cello produced some exquisite sounds and clearly has been made properly.’

A team of students spent 12 weeks making the instrument, based on Stradivari’s later cellos. According to a report in The Strad, construction followed a traditional English method of a full outside template and the rib structure was built on a board without a mould. The back length was 29 3/4 inches, and the varnish was based on a Cremonese recipe. Student Paul Harrild painted the Prince of Wales’ feathers on the back, and the tailpiece incorporates a silver badge with the motto ‘Ich dien’ made by Karsten Christensen.

Glen Collins also made a child-sized instrument for the new-born Prince William in 1984, which he presented to the Princess of Wales after a rehearsal of the National Children’s Orchestra.

50 years of NSVM · 14

STORMY WATERS

The past few years have not been easy for the school. In 2016 Ofsted (the UK government body responsible for inspecting educational establishments) changed its rating of Newark’s parent Lincoln College Group from outstanding to requiring improvement, without any reference to the school itself. One consequence was that international student visas were cancelled and for a while it seemed that four international students would be deported. A concerted campaign eventually led to the decision being overturned.

Converting the course into an accredited BA degree in 2017 was not a popular decision, turning a vocation into an academic discipline. In practical terms, it also means that UK students must now pay £8,500 a year, or £9,500 if international (in 1977, the course fee was £180, which was covered by local authority grants). Those who have already taken a degree are ineligible for a student loan, making it harder for older people who had already studied to come and jeopardising the diversity of the student body.

Ceris Jones, course tutor, says about the decision, ‘When talk of the BA course began the staff advised against it. People in the trade were invited to put their opinions forward, which they did, and there was plenty of opposition. The cost, content and student numbers would be adversely affected and similar models have already been seen to fail. I’m not sure what the benefits of the degree course were said to be, but it went ahead, and the first qualifying year was in 2020 under hugely mitigated Covid circumstances, so it didn’t have the best start, and we still don’t see an improvement in resources, for all the extra fees.’

Peter Smith, course coordinator, explains, ‘The course was very always physical and practical, all about learning to be a maker and a restorer. It’s now a BA and people have different views on that. We’ve done our best to keep it very practical. There is more writing and submissions than before, but we’ve tried to keep the majority of the awarding based on what you do, your skill and progress, and not about whether you can

put together a nice portfolio. But the BA has changed things and these changes have resulted in a reduced cohort of students.’

The effects of Brexit and Covid came as a double blow, affecting student numbers and what the school could offer students. Jones says: ‘Brexit is a problem because when students come from Europe now, they’re not allowed to work. Before they all had jobs in Pizza Express and behind the bars to get through the course, but they’re not allowed to do that now.’

Peter Smith agrees, ‘Brexit has made a big difference. It’s harder and more expensive for overseas students to get into the school and they have to pay for their visa. The expenses for all students let alone violin makers are more prohibitive now. And of course, there was Covid, which created a huge amount of disruption, as best as we tried to go on. Some did fine and were able to work independently, but others found it very difficult.’

Thijs Van Den Broek remembers lockdown: ‘We had some online lectures, which was okay for me because I have experience and I’m equipped to work at home so I could keep on working. For some students it was painful because they didn’t have the equipment to work or weren’t confident enough to proceed, and they got stuck when they just needed a few pointers. It wasn’t ideal, but somehow everybody managed to pull through. Everyone was happy to be back in school and to have the social side and teaching again.’

50 years of NSVM · 15

THE SECRETS OF SUCCESS

HOW DID A SMALL MARKET TOWN IN THE EAST MIDLANDS GIVE RISE TO A GREAT VIOLIN-MAKING TRADITION IN THE SPACE OF ONLY 50 YEARS?

The roll call of Newark alumni reads like a Who’s Who of violin making – not only from workshops around the UK but throughout the world. How has such a relatively small school in a town with no particular violin-making history essentially created its own tradition in the space of 50 years, and one that rivals some of the most ancient ones?

It seems to be a case of right time, right place. Maurice Bouette’s vision captured a certain Bohemian, creative spirit of the time, fostering an atmosphere of curiosity and individualism while also teaching the required skills and discipline. It’s tempting to characterise this as quintessentially English – a little eccentric and amateur, in the best senses of the words – but that would belie the fact that its students have always been drawn from all over the world.

Indeed, from the beginning, there was a mixture of nationalities and levels of experience – whereas other violin making schools only admitted school leavers,

Newark was open to all ages, leading to relatively large, mixed classes. Andrew Finnigan remembers being inspired by the conversations that came out of this chemistry: ‘In my year there was a 60-year-old man who had taken early retirement and several people in their 30s and 40s, so it was a good mix, which made for an interesting atmosphere. One man in the year above me had been a well-known architect in Munich. It was always interesting to listen to these people who had experience in other areas of the arts and crafts. It affects the conversations you have, compared with being with a bunch of 18-year-olds.’

The spirit of camaraderie engendered in the Newark workshop and the sharing of knowledge and perspectives has had a seismic impact on the whole violin world, according to John Dilworth: ‘In the postwar period violin makers in the UK were pretty isolated and didn’t communicate with each other to any great extent. They were so insecure that the idea of telling their secrets to somebody else was out of the question. It was all hard-earned personal experience. Now there’s so much good-quality expertise and

50 years of NSVM

information available, which has had a fantastic effect. Newark has certainly been a vital part of that. In the old days, you might go and work for a little firm somewhere and probably never meet another violin maker in your whole career. You’d just sit in a basement shooting fingerboards until your fingers dropped off. Newark followed a different concept, bringing apprentices or trainees together in one place in the spirit of sharing everything.’

Another key factor in the outlook of Newark alumni is the culture of looking at instruments, which is imbued early on with visits to auction houses and exhibitions, and instruments in the workshop for students to copy. Robin Aitchison explains the effect: ‘Seeing instruments and grappling with understanding them is so important. To understand the concept of style, you have to come into contact with instruments. They may not be Strads, but they may be great, even if for the students, it is not entirely obvious why. The actual elements of quality in violin making work can be mysterious and if people aren’t exposed to this breadth of stylistic culture, they may not be open minded.’

For this reason, Newark’s location is key, according to Aitchison: ‘The context of the school being in England is incredibly important. There are few places in the world with such a high density of musical activity. London was and still is an important centre for the violin trade and there are fantastic collections, so any student has access to a broad body of old instruments. It also means that the school draws on the trade for its staff and that there are people with very different outlooks. There are people with experience of the real world of the violin trade teaching there and that is extraordinary.’

This acknowledgement of the importance of the real world was baked in from the start, with Bouette enlisting Charles Beare, Yehudi Menuhin, Bernard Shore, Desmond Hill and Lionel Tertis to an advisory panel. Throughout its history, the range of celebrated players, experts and makers that has come through the doors of the school has been key in its success. From a practical point of view, they have offered business

connections and pragmatic wisdom; artistically, they have undoubtably inspired students in their aesthetic quest.

Indeed, it’s hard to imagine the school having made such an impact without the support of Beare, who has also provided instruments to study and jobs for graduates. Dilworth remembers: ‘There was always a violin in the workshop that Charles Beare had lent, which he thought was worth copying. We all had an open invitation to come and visit his shop in London. He was a huge influence. He wanted the violin to thrive, for more people to be making better instruments. He gave Peter Gibson a job at the end of his threeyear course, the very first year of graduates from the school, which was a huge inspiration for everybody. His confidence in doing that made it all seem worthwhile.’ Jones says, ‘Charles Beare always came to the school to oversee the marking of all the test instruments. This was somebody at the very top of the trade evaluating students’ work. He gave the school credibility within the trade, so that qualifying at Newark was kind of a professional benchmark.’

Behind all of this, though, was the original vision of its founder, Maurice Bouette. Maybe, therefore, we should judge the success of the school by the standard he set. As he told Alburger: ‘When the day eventually comes for me to retire, as we all must some time, I would like to know that the Newark School of Violin Making was settled and on its feet, ready to carry on for countless years, as the great schools on the Continent. I would not have any more worries. It would be something that I had done and was happy with. I could come back to my house, make instruments, surrounded by this lovely countryside, which is so very important, take the dogs out for walks when I felt like it, sell wood, go to the village pub at lunch time and all the rest of it... It would be grand.’

In his lifetime, it was certainly the case that Newark was settled and could compare with the great schools on the continent. More recently there has been cause for concern, but also reasons to hope that it will find its feet again. That would indeed be grand – very grand.

50 years of NSVM · 17

STUDENTS AT NSVM

This list has been compiled by contacting many former students, several from each year group, and from Internet searches. Recollections vary, and there are inevitably errors. Names of a number who left early could not be traced. If students repeated a year or had a gap in their studies, we have included them in the year group where they spent most time or graduated with.

The dates are for the first year of the course; student names from foundation show in the relevant first year.

1974

INTERVIEWS BY ARIANE TODES

Brian Maynard

Tim Miller

Alan Milner

Kevin Wilkes

Michael Byrd (deceased)

Ian Clarke

Peter Clay (deceased)

Matthew Coltman

Dominic Excell

Howard Hill

David Lee

Terry McCool

Andrew Riley

Charles (Chuck) Rufino

Norman Thwaites

Arjaan Westdorp

Hendrik (Hein) Woldring

Jurgen Baranzek

Bob Deeley

Guy Delaverde (deceased)

Peter Gibson

Richard Hague

Les McAllen

Andy Mills

John Molineux

Albert Nelson (deceased)

Nick Woodward 1975

Julianna Nicholls

Derek Vaughan 1976

Lionel Adams (deceased)

Peter Croll

John Dilworth

Melvin Frost

Roger Hargrave

Paul Bickle (deceased)

Paul Bowers

Adam Whone 1973

Elliot Brunton (deceased)

Kate Caldwell

Miranda Green

Michael Kearns

Penny Lucas

David Hodgson

Anne Houssay

Brian Lisus

Julie Reed

Malcolm Siddall

Ron Thewlis

Joseph Thrift

1972

JULIE REED YEBOAH

(1976–1979)

I lived in Parliament Street in my second and third years – we were the first makers in the house. We had to heat it with coal, which was very inefficient. I had been a Girl Scout, so I could keep the fire going overnight, but I was the only one who tried because I was freezing. I had to get used to taking a bath once a week because nobody wanted to turn the electricity – in the US everyone was used to taking a shower every morning, so that was a big transition for me. We had a communal workshop in the house, although I mostly worked in my bedroom because it was warmer.

The house was pretty rough and ready. It’s never easy to live with other people because everyone has different levels of cleanliness. Varnish would explode on the stove and nobody would clean it up. We were all thrown together – all from different countries, with different ways of being, and it was great. I still have longlasting friendships with most of the people I met there. We were good friends and we took care of each other.

I played the cello and was in Joe Thrift’s band in folk clubs, and I also had a trio with Helen Michetschläger and Julianna Nicholls, although we had to transcribe trios because we all played the cello. We also had a Palm Court trio with Ron Thewlis and another violinist, dressed in period clothes for our gigs around Newark.

I remember when Yehudi Menuhin came up. We had to do a lot of cleaning, and he was very gracious and played my first violin. He drank nothing but Perrier water, which was a surprise for all of us because you could only get it in France in those days.

There wasn’t a lot to do in Newark itself. We’d go to Nottingham, but our big trips were to London, to

the sales and to see Charles Beare. He welcomed us in his workshop, and we met the restorers, which was very valuable. At the end of our time, we had an interview with him and he placed us all in shops.

Places like Mittenwald were very strict but in Newark we were given more freedom – probably more than we should have had, but it was a great learning experience. We learned from each other. Everyone had something to bring to the table. If you go to Mittenwald you probably come out as a fantastic woodworker and can sharpen tools really well, but you get stuck in the Mittenwald style, which is regimented and doesn’t have any freedom or artistic aspect.

The teachers all had their own styles so we just kind of had to figure everything out ourselves, looking at photos and seeing as many instruments as we could, to get ideas. Three years is not long to put all that information into your head, but we all went out into the world and could start from there and move our way up.

After Newark I went to work in Bremen with Roger Hargrave. He brought many people from Newark so his workshop was basically the Newark School of Violin Making workshop in Bremen. We were creating high-level craftsmanship together. There was no hierarchy. You felt the camaraderie that was so important in Newark. That camaraderie has pushed violin making to much greater heights. There used to be a lot of secrets in the 1970s. The internet has opened it all up and there’s more openness now, for example at Oberlin, where people get together to share ideas. Newark started that whole spirit. It was one of the best times of my life.

50 years of NSVM · 19

JOHN DILWORTH (1976–1979)

‘I originally went to Newark on the general musical instrument repair course but within a few weeks, I realised it was impossible to learn everything in two years and I loathed the time we spent messing around with pianos, so I transferred to violin making. I had been collecting violins from junk shops for years, doing horrible repairs. Our local library had Heron-Allen’s book and other classic titles and I had immersed myself in those, but it hadn’t occurred to me there was a career to be made. Newark showed me it was possible.

‘When I transferred to the violin course, it was its own little world, in a little building attached to the woodwind workshop. The violin makers were looked upon as rather snooty by other students. There was a sense that people on the violin making course had a purpose, a vocation, whereas by comparison it felt as if people on the general repair course didn’t quite know what else to do.

‘Maurice Bouette was a wonderful man and the whole project was his initiative. He had run evening classes and an amateur instrument making course before, as well as a violin wood business, but he wasn’t a born teacher and wasn’t particularly proficient, technically. He was a good manager and Newark was ideal for him.

‘Glen Collins was a leading repairer and was supercompetent and professional. He showed us how to work and to keep everything sharp and accurate. Everyone respected Wilf Saunders because he was an independent violin maker, which we all aspired to be. He would demonstrate everything with consummate skill and ease. That caused some tension, though. Wilf was basically self-taught and had invented many of his own methods and techniques. Maurice and Glen would say, ‘Oh, don’t listen to him, that’s not the right way to do it,’ but Wilf showed us and it worked. It didn’t cause us any trouble because we absorbed it all and it was great to have different things to try, but I think there was some professional jealousy between the three.

‘When I started, the course structure was pretty crude. The first week was spent jointing backs and fronts for five instruments. Several people had never even picked up a plane before and cried with frustration, but the teachers said, ‘No, you can’t do anything till you’ve got all the backs and fronts jointed.’ We all got through it, but it struck me as a strange way of going about it.

‘In our last term, we had to make an instrument from start to finish and we either passed or failed, depending on whether we completed it. I don’t remember anybody failing. That was the only test

50 years of NSVM · 20

we had when I was there. It was only a diploma course and wasn’t recognised by any guild or trade union. But Maurice was trying to make the course more slick and decided we should all have a practical test halfway through. We had to cut a hole in a piece of plywood and then cut another piece to fill the hole exactly. Everyone was outraged. They found it insulting and let Maurice know. He ended up in in his little office in tears and we all felt rotten.

‘There was a lot of mutual teaching between the students, because there were only three staff and three years’ worth of students in the workshop at the same time, so contact with teachers was a bit thin. There was a shift system in the workshop, because we went away to do other classes – jewellery/silversmithing, woodwork and toolmaking. We also did music theory, although a lot of people resented that.

‘When I joined, the school was in transition between being a full-time evening class and becoming much more professional. There was very little information around at the time. To get an outline or even a Strad to copy an outline, let alone the arching, was impossible. What we had was more-or-less drawn on the back of an envelope. It got much better very quickly, though, mostly because the students shared things. Anything you could get hold of was immediately copied and handed around the whole workshop. The teachers

weren’t very imposing so the whole idea of doing research and finding things out for yourself became entrenched, which was great. If you weren’t prepared to do that, you probably weren’t cut out for violin making.

‘I’d led a very sheltered life and had never met a foreigner before, but there were Americans, French, Germans and Dutch, so I was thrilled to bits. There was a real spirit – mutually supportive and almost always helpful, with quite a lot of drinking, although occasionally people got their feathers ruffled.

‘I don’t think the school was intending to produce a whole generation of Stradivaris, but just to give people a way of making a living shooting fingerboards and fitting bridges, to supply shops up and down the country with competent repairers. That’s all most of us expected to do afterwards, making the odd instrument for our own pleasure and possibly profit. There wasn’t a market for new violins then. People didn’t trust modern instruments because there hadn’t been enough good makers in England for a while. It was all modern Italians, and old instruments still comparatively affordable.

‘Newark has had a huge impact. You can now make a living as a violin maker in this country because the standard of work has gone up. Musicians trust makers. They can go to someone who’s been properly trained and get a violin that works well and won’t collapse or burst into flames.’

50 years of NSVM · 21

Andrew Fairfax

Hans Johannson

John Johnson

Pat Jowett

Helen Michetschläger

Koen Padding (deceased)

James Rawes

Louise Round

Gordon Stevenson

Brian (Robert) Stone

Patrick Webster

Paul Weiss

Philip Archer

Neil Bagshaw (deceased)

Tim Baker

Joff Beilby

Catherine Favre

Daphne Hamilton (now Everett)

Andrew Hutchinson

Bill Poulston

Mark Robinson

Jaap Timmer

René Zaal 1979

Tim Bergen

William Castle

Karsten Christensen

Christopher Dungey

James Fawcett

Paul Harrild

Tony Johnson

Tim Littlar

Gavin Macalister

Roger Millichamp

Seng Kah Teoh

Alan Ward

1980

Martin Andrews

Stewart Bain

Béatrice de Haller

Terence Donavan (deceased)

Sylvie Flory (now Fawcett)

Emmanuel Gradoux-Matt

Mark Jackson

Chris Leslie

Thalia Savva (deceased)

Jan Shelley

Rick Batey

Nigel Bunce

Anneleen van der Grinten (now Fairfax-van der Grinten) 1981

Paul Collins

Geoff Denyer

Nicholas Hedges

Louise Moore (now Padday)

Tony Padday

Mark Pengilly

Patrick Robin

Julian Butler

Ian Dolphin

Marcus van der Grinten 1982

Andrea Frandsen

Lydia Friesen (now Rosetta)

Lisa Jørgenson (deceased)

Martin Oakley

Falk Peters

Jessica Tamsma

Simon Watkin

Jonathan Woolston

50 years of NSVM · 22

1977

1978

Frédéric Chaudière

Sonya De Sax

Lawrence Dillon (deceased)

Beata Dümling

Neil Ertz (deceased)

Paul Gosling

Eero Haahti

Marielle Leteneur

Ken McDonald

Per S. Oveson

Eric Put

Stepan Soultanian

Adèle Beardsmore

Sarah Beaton

Rob Cain

Jean-Pierre Champeval

Douglas Finlay

Kate Grundy

Michael Hill

Christopher Rowe

Russell Stowe

Jan Strumphler

Clive Wilkinson

Ute Zahn 1985

Kirsten Aaling

Thomas Bojesen

Kerry Boylan

Daniel Bristow

Phillip Cray (deceased)

Simone Escher

Mark Holden (deceased)

Paul Keys

Bharat Khandekar

Martin Schuster

Peter Smith

Tansy Southcombe (now Deitenbeck)

Colin Cross

Karin Grobel

Gordon Kerr

Daniel Kogge

John Langstaffe

Elspeth Noble (now Rowe)

David Munro

Kai-Thomas Roth

Dietmar Schweizer

Friedrich Alber

Martin Coath

Jan van der Elst 1987

Gilbert Cox

Caroline Crowley

Colm Gowran

Brian Laurence (deceased)

Paul Martin

Christopher Maynard

Ray Ramsey (deceased)

William Russell

Kelvin Steele

Ruben Collado

Ieuan Davies

Rachelle Turgeon 1988

Bas de Vries

Steve Gibbons

Peter Hall

Jim Jones

Gerard Kilbride

Klaus Klepper

Claire Nichols

Mark Russell (deceased)

Ewen Thomson

Aart van Kollenburg

Gijsbert van Ziel

Ching Wah

50 years of NSVM · 23

1983

1986

1984

Peter Biggs

Andrew Finnigan

Andrew Hay

Susanne Hess

Hella Insinger

Tiffany Marsden

Thomas Meuwissen

Huang Qing

Derek Shackleton

John Simpson

Michel Van Mulders

Viola Zieβow

Tanja Brandon

Nigel Crinson

Vincent Gasseling

Susanne Goehlmann

Andy Holliman

Laurence Hubert

Kolja Lochmann

Philip Monical

Wolfram Neureither

Yoshio Sugiyama

Nicholas Whitehead

Matthew Wing

Susanna Fenton

Jimi Glenister

Geraldine Grandidier

Klaus Grumpelt

Guy Harrison

Andreas Hudelmayer

Neil Johnson

Angela Li

Arthur Reus (deceased)

David Sherlock

Michael Snowden

Robert Zimmerman

Hartmut Betz

Paul Bridgwater

Marc Chavanneau

Nicholas Gooch

Mark Jennings

Chris Johnson

Ceris Jones

Andreas Kockerbeck

Constanze Kuchler

Damien Merrer

Thorsten Ramm

Susanna Sillberg (now Collins)

Paul Stanton (deceased)

Dota Theodoridis (now Williams)

Alan Williams

Ian Winspear

Eva Zurcher

Philippe Zurcher

Robin Aitchison

Hugh Armour

Kim Baker

Benoît Gervais

Georg Gschaider

Michael Hatting

Mark Helber

Barbara Höfele (now Gschaider)

Angelika Künzel

Margret Maria Leifsdottir

Togo Matsuda

Iris Mattes (now Carr)

Bernard McLean

Norio Ogino

Simon Rodyck

Nicole Rohrbach

Benjamin Rotem

Hagen Schiffler

John Simmers

Elaine Spicer

Philipp Stutely

Karen Timm

Eva Wal

50 years of NSVM · 24

1989

1992

1993

1990

1991

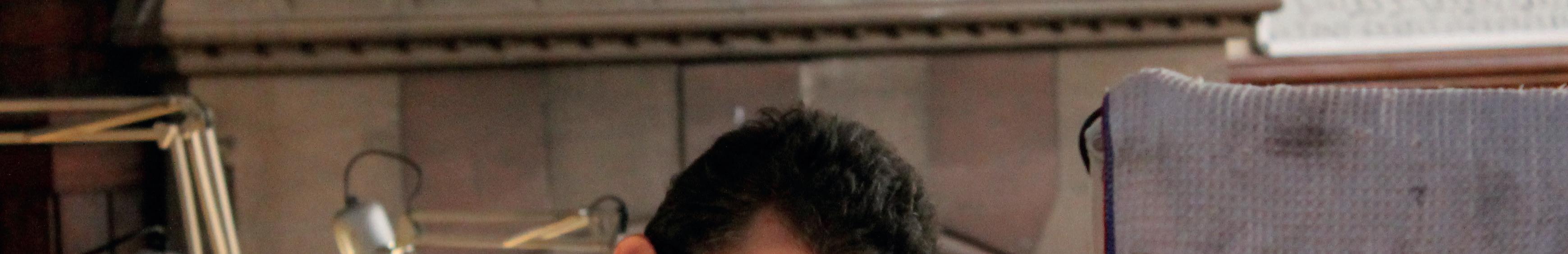

ANDREW FINNIGAN (1989–1992)

I was always fascinated by musical instruments and initially wanted to build a guitar. I went to the job centre and was given a very small list of addresses among which was The Newark School of Violin Making. I hadn’t considered making a violin, but it sounded fascinating, so I took a day trip to have a look. There were a couple of handmade violins hanging in the window, and I realised I had to go to this school. I was fortunate to get a place because at that time student numbers were very limited – it was only 10 or 12 people.

I had imagined there would be lots of formal business and introductions to the theory of violin making, but we arrived on Monday morning at 9am and by 9.10am I had a piece of wood in my hand to make a form. We just plunged straight in. There were theory lessons along the way, but it was nicely dosed – just the right amount of information to make the next step so you weren’t overwhelmed. My teacher was Paul Bowers, who was an excellent tutor – a fabulous craftsman with a sympathetic way of conveying information.

The atmosphere in the first year was a little bit tense. There were a few people who weren’t quite sure if it was what they wanted to do or were finding their feet. I was really happy being there. I’d been in industry for seven years before that and I knew it

was exactly the right fit for me. By the second and third years a few people had left or decided not to take the exams and it was more relaxed.

In the third year, we had Pat Jowett, with whom we discussed acoustics and varnish, and who encouraged us to think about alternative methods, which was a good counterfoil to being told what to do. In the second year, we learned repairs and how to set up instruments from Glen Collins, who’d been trained in the best shops in London.

Every Wednesday evening, we went to the Woolpack pub. The interior had obviously been white at some point in its life but was dingy yellow from all the cigarettes that had been smoked. Lots of people brought violins and guitars and there would be a jam every week.

50 years of NSVM · 25

Lothar Althaus

Pierre Burgos

Anthony Carr

Wilbert de Roo

Andrea Dürr

Barry Fettes

Nina Gygax

Pierre Helbert

Nele Jülch

Harriet Kjaer

Elke Kreck

Don Lawson

Mark O’Brien

Colin Adamson

David Alcock

James Beatley

Bertrand Bellin

Andrea Bischoff

Sylvie Bordenave

Paul Bradley

Nigel Briggs

Peter Busch

Benoit Charon

Benjamin Conover

Kai Dase

Matthieu Devuyst

Emmanuelle Fayat

Pierre Fournier

Fabienne Gauchet

Nicolas Gilles

Tanja Hidde

Melanie Kaltenbach

Oliver Kerth

Susanne Küster

Frédéric Lassuce

Anne le Foll (now Lévi)

Frédéric Lévi

Antje Linsmaier

Christiane Mitschke

Virginie Pezet

Sylvie Pham

1996

Mark Rice

Renate Schraag

Monique Tieman

Renate Wilfling (now Gök)

Gavin Wood

John Barber

Geoff Bowers

Jason Boyd

Agnes Chevalier

Giuseppe Gagliano

Peter Goodfellow

Joséphine Guédan

Liz Harrison (Now Gosling)

Pia Klaembt

Marine Loos

Johann Lotter

Sandrine Louvet

Matthias Menantau

Ulrike Menk

Jean-Patrick (JP) Moisy

Andrea Oldfield (now Green)

Ulrike Overhagen

Martin Penning

Mike Philpot

Tobias Pöhling

Guinevere Sommers-Hill

Jean Abel

Pierre Bauthier

Michaela Wedemeyer 1997

Scott Becker

Paul Belin

Cedric Bon

Charles Coquet

Sonja de Bruijn

Frederic de Moor

Francois Ettori

Edward Gaut

Louise Green

Ute Heim

Swantje Hirschmann

50 years of NSVM · 26

1994

1995

PAUL BELIN

I was 17 when I went to Newark. I played the cello and had visited a couple of violin makers, and although I didn’t have any experience, I was clear I wanted to be a maker. It was my first time away from home and it was wonderful. There was a lot of freedom. Going to school to learn something that I actually enjoyed was quite a difference. We were five guys in a house and we became friends very quickly.

In the first month we only studied the basics and it felt quite slow. I was eager to get on with making a violin, but we spent ages making templates and moulds, so there was a mix of joy in starting to do what I wanted to do but frustration that it didn’t go fast enough. The atmosphere was very friendly although it could be a bit competitive.

There was some set-up education, but not really enough. We made a few bridges, but when you come to a proper workshop, you have to cut a bridge in less than two hours and I wasn’t prepared. I was lucky to start in a small workshop in a small town, which was the time for me to learn, and when I worked in Paris I cut two cello bridges on my first day.

The thing that defines Newark is the liberty of trying everything – the diversity. Other violin making

schools seem to be quite fixed on one method and don’t allow students to try anything different. The major advantage at Newark was being able to try everything. There were students there from Mirecourt who had different methods and some students did work experience with different makers and they learnt other ways. This emulation produced something very positive.

50 years of NSVM · 27

(1997–2000)

Jean-Michel Ithurburu

Julie Jeanguillaume

Jon Jonsson

Marc Melchior

Jarkko Niemi

Dörte Oppenhorst

Sonja Pätzold-Schade

Stephane Rochefort

Armin Seebass

Jonathan Springall

Kuros Torkzadeh

Gaëlle Touchet

Aart-Jan van de Pol

Youenn Bothorel

Ingo Brinkmeier

Antoine Cauche

Marielle Collard

Yann Ecochard

Sophie Erdal

Antoine Gilles

Merle Gosewinkel

John Gosling

David Greeley

David Green

Peter Green

Ragnar Hayn

Alain Herard

Elie Hoffman

Martin Jones

Herfried Ludwig

Anna Luhmann (Now Ueberschaer)

Severin Morando

Tina Müller-Löffelholz

Yann Poulain

Stephen Quinney

John Ryan

Andrew Sutherland

Nicolas Vuillemin

Hugh Withycombe

Chaim Achttienribbe

Warren Bailey

Martin Banditt

Denis Barbier

Fany Bourel

Alexandre Breton

Sinhae Choi

Sören Dietrich

Thibaut Dumas

Tony Echavidre

Elodie Egret

Irina Feichtl

Narelle Freeman

Francois Guillaume

Javier Guraya

David Heckenberg

Adam Korman

Sabine Kuchelmeister

Damien Lagarde

Stefan Lindholm

Bettina Lindner (now Hayn)

Anna Maria Linemann

Ji Oh Sung

Rebecca Pierce

Uswin Ross

Thomas Weale

Frederick Yaro

Jérome Abriel

Astrid Bauer

Marie Bayle

Johannes Blackstein

Olivier Calmeille

Jenny de Jong

Becky Downing (now Springall)

David Doyle

Jimmy Fenlon

Colin Garrett

Martina Hawe

Lucy Heron-Johnson

Alexandre Hillairet

Gi Kwon Hong

50 years of NSVM · 28

1998

1999

2000

Guy How

Seunghyun Kim

Tetsuya Kimura

Rodrigo Lopez

Bas Maas

Christopher Manship

Frank Pedus

Marko Pennanen

Simon Peters

Eugénie Sainte-Cluque

Steffi Schneider (now Koplin)

Raphaël Thirion

Junko Yagi

Kevin Aussel

Alexandra Apenberg

Jeremy Ard (deceased)

Nicolas Binanzer

Alan Corbel

François Desprez

Gregory Dimanche

Samuel Dumbrill

Tanguy Fraval

Joachim Funck

Pierre Galbrun

Arnaud Giral

Catherine Janssens

Mark Keenan

Nigel Melfi

Solène Monmarché

John Outram

Jocelyn Papon

Andrew Quelch

Damien Rosenstiel

Daniel Ross

Damien Sainmont

Jens Towet

Usa von Stietencron

Samantha Whitaker

Christina Yankovitch

Patrick Barden

Mathieu Bricheux

Olivier Chabert

Paul Conway

Nick Cooper

Ian Devine

Sean Galvin

Jean-Charles Guillou

Guy Haws

Nanny Hergils

Ugo Janer

Grace Kang

Jay Kang

Markus Laine

Julien Lebastard

Amelie Melow

Chloé Michaud

Sally Mullikin

Fernando Muñoz Aladro

Brian Roche

Natanael Sasaki

James Stephenson

Alexandre Valois

Njål Bendixen

Marion Bennardo

Etienne Bergerault

Sandrine Boget

Quentin Bouvron

Philippe Briand

Marion Feuvrais

Arthur Frémont

Aurélie Georges

Eiko Ito

Eric Jackson

Anja Kuch

Sheena Laurie

Anne Le Bail

Gwenaël Le Page

Moritz Lingelbach

Douglas Macarthur

Marco Matathia

50 years of NSVM · 29 2001

2002

2003

SALLY MULLIKIN

I was looking at different schools and cold-called violin makers I had heard of, and many of them suggested Newark. At that time there were a lot of exciting new makers who had studied there. I graduated with a music degree with a concentration on viola, but alongside my studies I had also worked as an apprentice with a violin maker, sweeping floors, doing administrative stuff and helping to set up rentals. He guided me through building a viola and I was hooked. So I had a little bit of experience with tools and was able to skip the foundation year at Newark.

Americans have a preconceived stereotype of England, and in my mind it was going to be all Oxford and Cambridge. I was charmed by the school right away – I thought I had stepped into a Harry Potter book, but I wasn’t prepared for the gritty workingclass atmosphere in Newark. The first day I arrived, I found the flat where I was staying and I went to find a phone box to call home, and there were two men wasted in the main square, calling out to me, ‘You all right, love?’ One was peeing in the street. Eventually I got my bearings and once I started meeting the other students and the teachers I realised that it was going to be all right, but there was a little cultural adjustment at the beginning.

I would have lessons with one teacher and they’d give me one way to do something and the next day I’d have another teacher who would tell me that everything I’d learnt the day before was totally wrong. It was confusing, but eventually I realised it was good to have two different perspectives and approaches, even though when you’re first trying to learn a skill it’s overwhelming. I would go and cry in the bathroom those first few weeks, but eventually, I was glad I got

to study with both of them. There was an openness and a sense that it’s okay to mess up – it’s all part of a learning process. All the tutors had very different styles and expertise and we were encouraged to try lots of different things.

In the second year, we made a viola and learned some repair and set-up so I was able to get a job in Nottingham at Turner’s Violins. A few of us would go in on a Saturday to set up instruments and do basic repairs, which enhanced my education and got me hooked on repair work and restoration.

Part of the experience was just being abroad. I was right out of college and had never travelled or known people from different backgrounds. It taught me that you don’t have to come from a particular background to be a successful violin maker, which was a good perspective to take with me. It gave me a leg up in getting employment because they emphasised not just making the instruments but how to repair them. Repair experience is really what you need when you’re looking for your first job – nobody cares if you can build an instrument – they want to know you can fix a crack.

Everybody was supportive and there was a lot of camaraderie. When we took breaks, somebody would always have some biscuits and we’d have tea and chat and look at old Strad magazines. I kept busy with extra-curricular things – I took pottery classes, and we had a tiny garden and tried to grow tomatoes, but they never got enough sun, so they stayed green. There were always opportunities to play music in a social setting, which I really enjoyed and miss having access to now. I have so many great memories – it was a wonderful time.

50 years of NSVM · 30

(2002–2005)

Sandrine Osman

Marianne Ponz

Benjamin Ross

Tobias Seidl

Frank White

Gareth Ballard

Véronique Bereda

Manuel Di Landa

Marion Gauvrit

Becky Houghton

Morgan Jordan Fleta

Seisuke Kawamura

Peter Killingback (deceased)

Eun Ah Kim

Elisabeth Kunz

Heath Lavery

Garth Penner Lee

Daniel Mannel

Eggert Marinosson

Stéphanie Merle

Victor Ortiz

Filippo Protani

Suzy Schmitt

Simon Shaw

Kathleen Thomas

Thilde van Norel

Emmanuelle Vanstals

Laura Vick ( now Vick

Alaghbash)

John Bean

Victor Bernard

Romain Bertin

Frédérique Blanchard

Henry Britton

Gordon Burns

Kate Davis

Valentine Dewit

Katarina Dorotkova

Pål Ekeberg

Carole Feral

Florence Ford

Philip Harrison

Daoudi Hassoun

Wietske Leenders

Martin Lory

Alexandre Mallet

Genji Matsuda

Vincent Mouret

Pauline Peillon

Igor Przybylo

Hillary Rollings

IJmkje van der Werf

Benedikt van Gompel

Alain Vanpeene

Nicholas Acons

Bruno Barbancey

Marie-Ange Boureau

Pierrick Brault

Brigitte Brette

Jose Catoira

Emily Cruse

Ben Damon

Andres Enssle

Antoine Gourdon

Emmanuelle Guisse

Dennis Jones

Zoser Kahil

Lauri Kallinen

Jin Hyung Kong

Max Kretzschmann

Kathryn Lyus

Pierre Picard

Mariela Piette

Emilie Sabathier

Clement Salles

Charlotte Sanagustin

Stephen Silcock

Eduard Sitjas

Simon Tillyard

Tiffany Webb

Erik Wendrich

50 years of NSVM · 31 2004

2006

2005

Julien Bachellier

Silvia Beyer

Lorraine Bitaud

Kate Bomphrey

Charles Collis

Antonin Corbineau

Ursula Eidenmüller

Niall Flemming

Leslie Gandriau

Ian Greig

James Huckle

Je Hui Jun

André Keil

Jörg Koplin

Nao Kurata

Florence Le Mennec

Alisa Leube

Grainne McGee

Marcas O Bardáin

Julie Oberlé

Florian Paichard

Michael Phoenix

Peter Jeong-Woo Ryu

Pedro Santos

Stephen Silcock

Yumi Takada

Leslie Tenne Deux

Mette-Mari Vea

Hyun Bong Yang

Verity Atkin

Benjamin Becker

Verena Behrendt

Gabriel Bolliger

Francesca Bottone

Kenneth Chevalier

Rachel Copin

Francesco Coquoz

Adèle Debias

Isabelle Forissier

Thomas Gauvillé

Rose Handy

Keisuke Hara

Guillaume Jacotin

Guillaume Joanin

William MacKay

Neil McWilliam

Emmanuel Ouvry

Caroline Pasquet

Jean-Philippe Remuzon

Lucy Riou

Shelley Rodgers (now Aragoncillo)

Sueng Ho Ryu

Shinjiro Sada

Julien Surville

Hisako Tanabe

Patrick Toole

Rolf Waefler

Maximillian Zanders

Florian Bailly

Chung-Wei Chiu

Robert Davison

Brian de Boer

William Desquiens

Chris Emmett

Jake Foley

Floriane Forconi

Robert Furze

Magdalena Gabriel

Monica Gapinksa

Lucie Girard

Lise Gros

Thomas Jocks

Guillaume Kessler

Marie Paquet

Catherine Robertson

Antoni Ruschil

Shehada Shalalda

Aogu Shimasaki

Tim Sparrow

50 years of NSVM · 32 2007

2008

2009

Robert (Andy) Adams

Bastien Borsarello

Chiling Chen

Younjoon Chung

Charles Cousins

Emilio Kusi Crabbé

Alexandre Cremet

Eva-Marie Daino

Anne-Klervie Fichot

Laurentius Huige

Toby Jepp

Milan Klose

Olga Londe

David Luff

Anne-Laure Luiceanu

Elsa Mareau

Richard Moakes

Benjamin Molinaro

Tim Monstermann

Etienne Pavie

Fanny Prost

Pauline Riteau

Lauri Tanner

Eva Lotte von Zimmermann

Adam Winskill

Andy Wong

Clement Benoît

Pierre-Antoine Buffet

Matthew Cherry

Elià Fabré Capdevila

Pauline Franceschi

Hannah Frankowski

Kevin Harrington

Richard Hockney

Clement Le Quan

Marie Lequeux

Finn Liengaard

Ewen MacLaine

Mathieu Morando

Mathieu Penet

Paul Shelley

Robert Stepp

Nicole Terry

Laetita Vouillot

Colin Wyatt

Sam Brouwer

Eric Charpentier

Cyrielle Dantec

Ben De Wulf

Gergely Ficsor

Franziska Gerstner

Kira Hasche (now Buckow)

Ian Knepper

Pau Barnes Moreno

Robin Morris-Haynes

Leo Pastureau

Stuart Reid

Ben Schindler

Ben Torres

Francesca Vickers

Kevin Baslé

Helena Becht

Stuart Bell

Derrick Buckfield

Julien Comte

Robert Crooks

Alberto Dolce

Michael Donnerstag

Marie-Flore Dubost

Drew Evans

Julie Folio

Lea Fuentes

Neal Heppleston

Konstantinos Karadimas

Svavar Garri Kristjansson

Anne Mervant

Felepe Munoz

Julian Page

Cesar Sakellarides

Pierre Smets

Fried Van Doorslaer

50 years of NSVM · 33 2010

2012

2013

2011

Kit Worrall

Fu Cao (Frank) Yong

Emmanuel Alberca

Mathilde Baulin (now Rhimbault Baulin)

Pauline Bordes

Hsu-Yen Chan

Jonathan Derbyshire

Melody Ehlerding

Mathieu Fourrier (now Fourrier

Lecher)

Maximilian Franke

Alejandro Gomez

Jung-Hoon Han

Ashton Hicklin

Stephanie Irvine

Maja Kallen

Sebastian Le Fevre

Ines Lecher (now Fourrier

Lecher)

Carlos Libereros Rios

Arthur Molina

Noemie Moreaux

Brian Nielsen

Kay Park

Tom Ravon

Ruth Robertson

Michael Sheridan

Hanna Stumpfl (now Bozzetta)

Harry Twidale

Linus Andersson

Leonarda Auracher

Geoffrey Blohorn

Paul Chantre

Ling-tzu Chen

Daniel Chick

Capucine Denis

Clàudia Fité Piguillem

Cecilia Gonzalez-Gutierrez

Elisabeth Graml

Mark Healy

Ronja Heyer

Florent Hochet

Rocky Holman

Cesar Joughin

Jason Ludlow

Henry Mann

Pablo Otero

Sarah Padday

Jason Reitenberger

Julia Sarano

Harry Strong

Paul Touguesh

Raffaele Ansaloni

Elena Calabuig Benitez

Marina Castellanos Rubio

Laure Clément

Hannes Dreyer

Steven Ebbinghaus

Jahnava Gargallo

Alejandre Gonzalez

Alicia Goode

Julius Hennicke

Andrew Lennon

Massimilliano Muti

Yasuhiro Nakashima

Oliver Nicholson

Marios Pavlou

Sarah Pipala

Marion Pollart

Meng-Hsiu Tsai

Fabienne Arimont

Ludivine Brouillet

Nathan Colman

Lucas Coquelet

Alex Janonyte

Eloise Marin

Theo Parmakis

Roger Rosa

Jesus Garcia de Leon Rubio

50 years of NSVM · 34 2014

2016

2017

2015

HANNA BOZZETTA (2014–2017)

When I was choosing where to study, I went to several violin makers and asked them where they had trained. One of them said Newark and recommended it especially as I was an older student – I was studying German and sports for teaching. He said it was more open and less like a school, and ideal if you were self-organised and motivated. I went there for an open day, a year before I applied, and fell in love with the community. I really liked the atmosphere. It was a completely new scene for me.

The building is very small and cosy, but that makes it possible for everyone to go around and ask questions. The first-years work on the first floor and the second years on the second, and the pleasure of being in the third year was being in the big entrance hall and having lots of space and eight metres of air above your head.

The organisational part was not always perfect: if I was looking for a tool, for example, it wasn’t always there. There were a lot of us, so time with the teachers was precious, and the people who were the most pushy would get more time.

My highlight was the BVMA’s 20th anniversary celebrations, which included a hands-on exhibition of old English makers, hosted at Newark. I was the student representative at the BVMA at the time so I was doing a lot of organisational work between the school and the BVMA.

The orchestra was self-organised by students, ideally playing instruments that were built in school. After a full day working, you would quickly grab something to eat and then have two hours of rehearsal. It was intense, but people really wanted to make music together, which made it work, even if it was a long day. We’d usually find a solo piece with a young soloist from Birmingham conservatoire or even within the violin-making school, and a symphonic piece. We would hang posters all over town and everyone who was interested in classical music would show up. It only happened once or twice a year, so a lot of people in town were excited and very supportive.

Newark has made a huge impact on the violin making world and I’m sad that all the knowledge that has been carried between students and generations might be lost. Students talk about someone who used a particular method two years ago and you would pick it up and tell someone else, so there was a huge amount of crowd-sourced knowledge floating around. If you had a problem, you could always find two or five solutions from different people. The many excellent makers from Newark are proof that it worked really well, especially compared with other schools. I’ve been in contact with graduates from Mittenwald, and they don’t have the wide range of techniques and approaches. They only know one way very well, rather than having the broad approach to problems that Newark taught me.

50 years of NSVM · 35

Photo credit: Martin Hörmandinger

Caroline Schroyen

Miranda Scott

František Špidlen

Libby Summers

Finn Trucco

Andrew (Woody) Woods

John Wright

Sylvain Busson

Patricia Cela Rojo

Niam Chauhan

David Davies

Wilf Dell

Sophie Ekau

Tony Ferguson

Josanna Fielder

Steven Fletcher

David Gouthro

Simon Jones

Ellie McLay

Angelo Muller

Nina Poots

Saara Raita

Kyle Schultz

Diego Tazzari de Almeda

Sophie Wohlleber

Ioan Paul Bandila

Merrit Biesenberger

Inès Bulliard

Victor Camilleri

Lola Courtois

Sebastiano Goio

Elena Llanes Rebanal

Alma Michel

Mark Pestana

Thomas Smith

Steven Asquith

Alina Ehret

Hanna Hofstetter

Ethan Martin

Max Spence

Thijs Van Den Broeck

Craig Foster

Benjamin Jones

Muireann Ní Sheoighe

Eachthighearn

Aiden Bradley

Willow Laoutaris-Smith

Rebecca Montgomery

Louis Peterson

Miranda Bailey-Sharam*

Ruth Bunting*

Peter Horwich*

Charlotte Teoh*

*2022 foundation

50 years of NSVM · 36

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

THIJS VAN DEN BROECK

I chose Newark for its reputation, because many well-known makers had gone through the school. When I visited, I felt it had a very international character and an open learning atmosphere, with lots of enthusiastic people.

In the first year we had Antoine Gourdon, who’s very meticulous and systematic, which is perfect for making your first instrument – it’s easy to get lost in the many different techniques. He was also open for students to try other methods, though, if you really wanted. Each teacher has their own specialities –that’s one of the strengths of the school for me: if you want to know something about varnishing, tools or making specialised jigs or repairs you just ask a different teacher.

The atmosphere is very friendly and open. It’s a BA course but it never feels like an academic setting because everyone works together and if we want to talk, we talk. People encourage each other, and you often find first-years talking to third-years in their workshop, or vice versa. In our spare time students go for walks or bicycle rides or play music in the pub in the evening. Last Easter I set out to make a violin in eight days with another student over the holiday – we both learnt a lot.

The most important thing Newark teaches is to have a broader view. I’ve heard that other schools can be quite rigid in their approach and don’t allow people to develop their own interests. At Newark, when a tutor sees a student is developing a certain style, they always encourage it. That can be double-sided, though, because some people fit a more rigid structure.

50 years of NSVM · 37

(2020–2023)

50 years of NSVM · 38

Shehada Shalalda, 2009-12, Palestine

Yumi Takada, 2007-2010, Japan

Olga Londe, 2010-13, France

Charles Rufino, 1974-77, USA

Hans Johannsson, 1977-80, Iceland

Victor Ortiz, 2004-7, Ecuador

LIFE AFTER NEWARK

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

Alongside checking names of all former Newark students, we have tried to find where they went on to work. The results show that the employment rate is high, with an average of 77% making a career of at least a few years; either self-employed, working for shops or setting up their own shops. The majority of those have spent at least a large chunk of their working lives in the trade.

To analyse the information more closely, we split it into decades: 1972-81, 1982-91, 1992-2001, 2002-11. The final decade of students includes an extra year, 201222, but for analysis of where they went on to work, the final three years of intake have been disregarded as they are not yet seeking work.

The chart gives information about the countries where former students went on to work. You can see changes over the years as the intake of the college became more international, with France and the UK absorbing the highest number of former Newark students. When the school started, female students were very

much in the minority, only 14% in the first decade of the school’s existence. This rose to almost 40% in recent years.

As the balance between the sexes has improved, an increasing number of relationships have blossomed. At least two dozen couples have made durable marriages or long-term partnerships. A few children have been born during the course while their parents were students; test instruments made while pregnant and new parents valiantly juggling children and work at the bench. And in their turn, at least two children of Newark students have followed in their parents’ footsteps and taken their places at the college.

50 years of NSVM · 39

1972-1981 0 20 40 60 80 100 1982-1991 1992-2001 2002-2011 2012-2018

UK USA/Canada Germany Asia/Rest of World France Australia/New Zealand Rest of Europe

NEWARK STUDENTS ACROSS THE GLOBE

WHERE THEY HAVE MADE THEIR CAREERS

Up to 5 students: Czech Republic, Ecuador, Hong Kong, Hungary, Israel, Palestine, Romania, Singapore, Cyprus, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Iceland, Slovakia, Sweden, Denmark, Taiwan

6-10 students: Italy, Austria, Finland, South Korea, Japan

11-20 students: Spain, Australia, Republic of Ireland, Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, USA

21-50 students: Canada

51-100 students: Germany

101-200 students: France

201-300 students: UK

50 years of NSVM · 40 ROMANIA HUNGARY SLOVAKIA NETHERLANDS DENMARK SWEDEN

ICELAND ISRAEL PALESTINE SOUTH AFRICA CANADA FINLAND BELGIUM SPAIN R. O. PORTUGAL AUSTRIA ITALY FRANCE KINGDOM GERMANY SWITZERLAND CYPRUS

UNITED STATES ECUADOR