THE ONEOTA REVIEW

Ashley Imdieke

Janette Gowdy

Clara Wodny

Sea Orme

Edie Meehan

Jersie Benson

Ella Rowley

Martin Klammer

Just like Aurora Borealis, this issue is bursting with light and creativity. We feel so fortunate to be part of such an inspired community, and we have loved seeing the written and captured beauty that students generate. As seniors, it’s bittersweet to think about the vibrant and wonderful campus we are leaving behind. However, it’s comforting to know that artistry and resoluteness will continue to fuel the campus community for generations to come; it is woven into the fabric of Luther and shared by every student that steps foot on campus.

In the unpredictable world that we live in, it is crucial to hold tight to the things that bring us joy and keep our minds moving. The three of us are so proud of the student body for donating their passions and imaginations to this literary collective, so that everyone can enjoy their work. After all, there is nothing more human than creating and there is nothing more prolific than sharing. Thank you to every student that has submitted their work and put their work out into the world, and we hope that you continue to take this step for the rest of your life.

We also possess so much gratitude for you, dear reader. Thank you for taking the time to pick up this issue and for exploring the work of the talented student artists and writers on campus. We hope you enjoy this issue, and that like the Aurora Borealis, it fills your day with light and creativity!

With love, Jannie, Clara, and Ashley

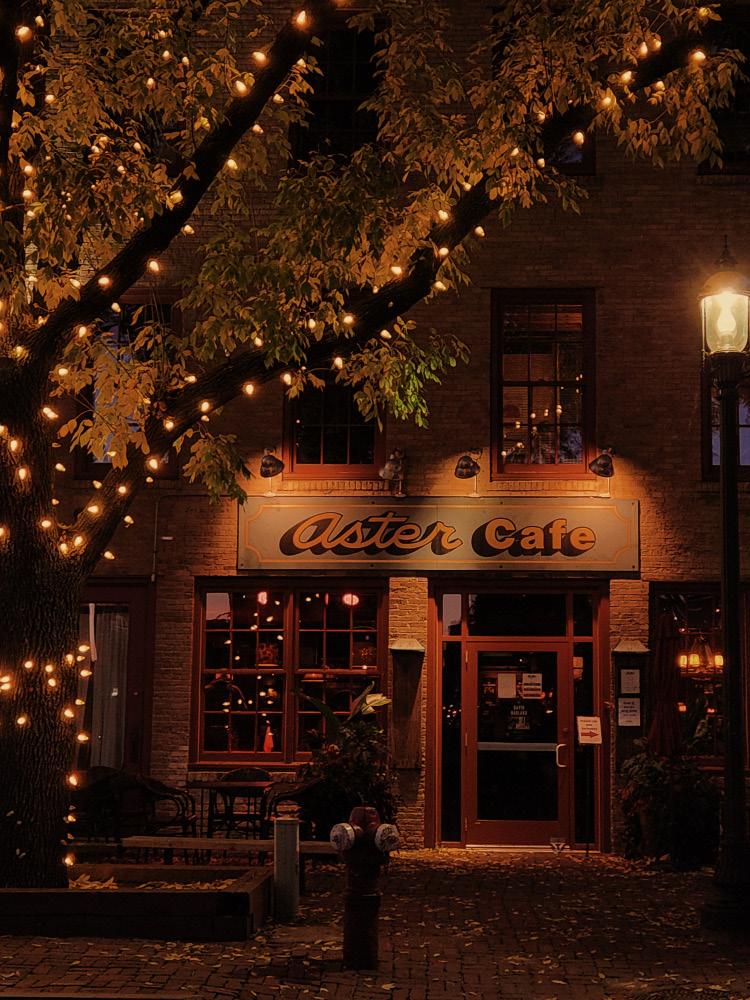

by Grace McIlrath

The Path to Baker Village by Michael Burns

Untitled by Resana Zayan

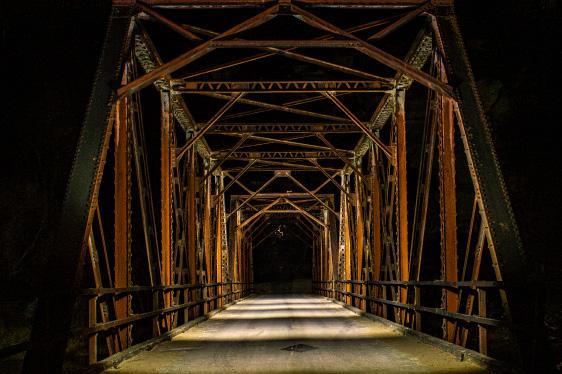

McCaffrey Bridge by Noah Arndt

Untitled by Resana Zayan

Decorah Lightning by Noah Arndt

Elijah Lehmann

Inspiredby“IAmOfferingthisPoem”byJimmySantiagoBaca

Could I offer something a bit sweeter, More childlike and innocent?

Like the old valentines, With the cheesy lines And the well placed candy.

I like you,

Could I offer something a bit lighter, With less weight and gravity?

Not daunted with complex implications. Soft, like the air in my lungs, Falling quiet as a feather.

I like you,

Could I offer something a bit cooler, Not inspired in Shakesparean flare?

Dressed in a cool breeze

That quells the bright passions of the sun And finds a home in peace

I like you,

In this, that I offer to you, There is no need for a response, Or guilt in an inability to reciprocate. These words are a truth That hold no bondage to the recipient.

I like you,

I have plenty more to give, And I could grow burdened With the mountains I’d try to move, For your sake, for our future. Yet all it takes is my simple statement,

I like you,

This is what I am offering: A conclusion that I enjoy existing with you, That you are funny and cool And I want to spend time with you. You are my friend.

I like you.

Maggie Bruck

Yes, I’d like to know a little about your noble act of writing: in pajamas, sliding me a new draft across the breakfast table.

I allow an oddment of your world in, because you allow it out, and the careful, clumsy reading we do is how art and friendship mend together. Isn’t this good because it isn’t done yet? Because before an artist can pin a needle to cloth, they must faithfully allow the winding thread to fall away from the spool?

I notice a curious knot in your brow when you believe I’ve reached the second stanza, in which you tell of a feeling that I also feel. On a snowed quilt of poetry, I too wish to lie down and spread my arms into the shape of an angel, settling my wings into a poet’s art, their dreams. An embroidery inspired, maybe, by a heaven.

But if the lines are not yet the picture you want, it’s still an honor to see just a thread of your dreams.

Grace McIlrath

Grace McIlrath

In a dark theatre, grey haired hippies raised their palms — sharp rays of light escaped through narrow slits.

Through cracking joints, rejuvenated, their bodies bobbed and swayed. The fountain of youth was on tap for ten ninety-five.

In the row ahead, a woman said, “The scarf’s from India,” to the gay couple next to her, trying to prove that she has lived a life worthy of the seat she occupies. My shoes were torn and the soles cracked. Beside me, the girl, whose ticket I bought so I may share her company, waited. With a patronising smile, a woman called us “Kiddos.”

Ill-equipped, we gripped each other tight and began our ascent.

Tears pricked my eyes when the light streaming in carried the image of a long haired woman — our guide to Mount Carmel.

Michael Burns

Sea Orme

I had a lot of firsts during my trip to Norway. First Lørdags Pizza (Respekt for Grandiosa!), first gay bar, first cross-country skiing experience, first cross-country crashing experience (x50), first time ordering in Norwegian at an actual cafe (Kan jeg ha en sandwich med ost og kylling? Takk!). First genuine urge to throttle a seagull around the neck (the bastard stole my croissant).

I certainly can’t say I’d ever had a wall wish me good morning before.

At first, I couldn’t even tell what the graffiti said. The letters were round, loopy creatures that snuggled into each other without regard for personal space. I squinted at this bewildering mass, until eventually an alien head with a single antennae became a lowercase d; an amorphous blob of squiggles became an m. God morn, it told me, tiny, white, and cheerful against an otherwise sad slate wall. The message was no larger than my hand. It would have been very easy for me to miss.

In Seattle, small graffiti isn’t really a thing. Near my neighborhood, there sits an abandoned yellow house, all sagging walls, its windows cracked cataracts. Tall dry grass grows in massive clumps along the base of the deck. I am frequently near it because my dog, tongue lolling, likes to wriggle through the tall grass. If you’re wondering, his breed is a brainless dolphin with legs.

Along the house’s peeling woodwork is the large, naked form of a woman in repose. She reclines streetside. Her eyes are dark as she watches us pass, the sun softening her sharp edges. Sometimes she is crying, water falling down her cheeks, and I wish I had thought to bring an umbrella. Her body’s vastness makes her a goddess, coiled muscles and strength laid out in loose leisure. She is a piece of graffiti made to be seen.

God morn: exclamation mark pointedly absent. The message wasn’t a request– it was a statement. I simply wasn’t allowed to have a bad morning. Or, rather, it didn’t matter if my morning was bad. Somewhere, someone’s morning had been good.

That afternoon, my school group was visiting the Nidaros Cathedral– a stupidly massive building and a built piece of art that has been crafted by thousands of hands, all across time. Few of the architects actually saw the project at its end. The infamous stained glass window alone contains at least 10,000 panes of glass, each pane individually crafted. Each piece of glass requires replacement every few years; the sun’s heat gradually warps their lead frames. Rather than change the frames to a more durable material, restoration simply coaxes the panes back into new lead. This process, free from machinery and reliant on the gentle precision of human hands, takes months.

When I entered the Cathedral, an intense smallness came over me. The marble space seemed to expand forever, each distant wall and ceiling possessing an impractical amount of detail. During the

Norwegian church service, I sat, awestruck. The deep peals of the church bell reverberated through my chest; I could feel the vibrations in my skull and the soles of my feet. The pure, clear tone of the choir had my eyes watering as much as the biting cold. It was just as Paul Simon prophesied: “He looks around, around, he sees angels in the architecture, spinning in infinity. He says Amen. Alleluia.” My poor soul was, indeed, crying out, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia– don’t bother with ascending; heaven is here.

I later learned from a documentary that the Cathedral’s most detailed ornamentation lives near the ceiling, unreachable with mere human eyes. The exact wording: “Humans may not see it, but god will.” That which took the most effort is not able– or meant– to be viewed by anything other than the divine. Logically, I could acknowledge this was perhaps an incredibly impractical architectural decision. Emotionally, spiritually, I was overcome.

The intricate ornamentation of the ceiling, the stained glass window, a piece of graffiti inked in miniature. It all uplifts the act of creating impractically beautiful things, simply for the sake of creating. Humans’ enduring belief in an unknown beauty takes my breath away. It’s natural to place faith in those things unseen, to pray to creation for the sake of creation; joy for the sake of pleasure.

On January 28th, I returned from Norway with a dragon curling down my spine. My first tattoo. He’s impossible to see, but I know he’s there. That is what matters. To those who know that our art breathes after we have gone: we understand that our presence does not necessitate art. It simply kickstarts it. It is lightning in a motionless heart, a stranger’s excellent morning. A rising sun on a portal of molten glass, glowing purple and blue.

Grace McIlrath

Sea Orme

I. Mythological and related uses.

I.1. Chiefly Classical Mythology. The food, drink, or anointing oil of the gods, often having the property of conferring immortality.

III. Zoological and ecological uses.

III.5. Bee bread. Pollen, esp. after it has been collected by honeybees, mixed with nectar and saliva, and stored as food for workers and brood.

Bare feet, Callused and tender, reddened skin sinking Grateful,

Into that pink-purple tongued softness– bewitched Blind to bloody sores–Dancing.

They bumble through my ribs and press their sticky sweet heads To my sunken heart, Swollen

Pollen-fat bodies idling striped. I am not mad,

For thinking myself a naturally growing thing. I hear The bees, I hear Their honeyed buzzing in my marrow. I hear Thistle is considered the devil’s clinging kiss, but I believe in the goldfinch. I believe in the snag and pull of thorns, The lonely stretch of prairie, An empty sky for song. My faith lives Soaring over that grassy space, I would fly,

A thistle stored in my bright believer’s beak.

Jannie Gowdy

The farmer begins his afternoon chores, haphazardly throwing sunflower seeds and wild seed mixtures into the bird-feeders for his wild friends. Before returning to his shed, he dumps the remains of his measuring scoop on the ground for the squirrels and birds who didn’t want to turn this mealtime into a conquest. Around him, a sad winter envelops the farm. Snow from the previous week is turning into a muddy and crusty mess underneath the bird-feeders, and the wind funnels low and sharply across the open yard. It’s been a long and desolate season, and all the critters on the farm are in desperate need of these regular meals that the farmer provides. And today, there is a new guest at the dinner table.

The young opossum waddles out from the stark grove of trees, blinking slowly in the sunlight. It is much too early for her to emerge from the tree hollow that she spent the night in, but the starving nomad needs to get to the seeds before the birds pick out the largest and crunchiest ones. Her pink feet, naked toes spread wide, barely leave imprints in the snow behind her as she reaches newly scattered seeds. Silently, she parts through the group of house sparrows that had descended from the branching treetops as the farmer turned his back.

There have been other opossums on this farm, but none so melancholic as this lovely creature. They all pass by alone, as it always has been, but this opossum is the first to mourn that. She is independent and resolute, yes, but evidently lonely. Her grey head swings low, and for now she doesn’t spare the others a glance or concern as she settles underneath the hanging oak bird feeder, a floor of food underneath her. She has showed up to the meal with no one by her side, and it feels awkward; like arriving at a party empty-handed, where you don’t know a single person. The birds and squirrels, and even the raccoons and barn cats all have their clans, their flocks, their families. Who does she have, this opossum that is set apart from the others?

As the only marsupials in the entire continent, opossums know what it is to love and lose. The females carry their babies close to them in warm, sequestered pouches until they grow big enough to cling to their mother’s back. With their small paws weaved deep in her yarned hair, the young joeys depend on their mother for everything. She carries them across streams and roads, forever moving forward and never looking back. Some babies fall behind, but the mother cannot risk the others. Some babies die, but there are more to live for. And eventually, all babies leave, sometimes before the mother even knows they’re gone. Such is love, but such is life.

This young opossum may have fallen off her mother at just three months old, and she has never relied on anyone else again. This would be her first winter, and there is no one to show her what to do or how to keep hunger at bay. She has slept through most of the freezing spells, alone, waiting for the

weather to relent slightly so that it would be warm enough to find a solid meal. How many days has it been since she had last eaten? Hunger has taken a toll on the precious young one, and the hair on her pink nose and ridge of her back are thinning. In a constant state of subtle trembling, her body is working as hard as it can to keep her warm by burning calories she doesn’t have.

The opossum is annoying some, scaring others. Two squirrels sit a couple feet away, their tails fully bushed and twitching. The birds’ anxiety has heightened; they don’t know this guest, and they don’t know how far her hunger would drive her to act. But the opossum, satisfied with the seeds in front of her, has no schemes–and no strength–to attack her fellow guests. As more birds cautiously arrive on the scene, stealing morsels from the outskirts of the seed drop, the opossum feasts. Her whiskers glow silver in the midday sun as she purposefully eats the seeds, using her pale, pointed nose to push small stacks together.

After she is satiated, she settles her abdomen down on the cold, packed snow. She might return to her tree hollow or find a new nook for the night. She might be fated to wander across the farm and the surrounding countryside aimlessly, foraging and trembling until the cold weather takes her. She could miraculously make it to spring, completing the feat that many young opossums could not, but what came after that? Possibly the creation and eventual crumbling of her own family, subjecting her joeys to the same loneliness that her experience has been full of.

For right now, she bows and feels the other animals interacting around her. None are so brave as to approach the opossum, but by now they seem to tolerate her presence. The birds chirp to each other and keep a watchful eye on the skies for a hawk, while the squirrels gorge themselves on as many seeds as they can fit in their mouths and play tag around the base of nearby trees. The opossum breathes it all in, eyes forward but aware of every guest around her. She is still lonely, but she is not alone, and that seems to be enough. Conversations and arguments, songs and warnings, and the indescribable sound of life fills her ears, and she is happy.

The next morning, the farmer returns to the bird feeders. He curses and fetches a rusted shovel from his shed. Gently, he scoops up the dead opossum and takes it to the ditch for the scavengers and coyotes to enjoy.

Michael Burns

Ruby Zorn

You can see it in the landscape, The way it arches and curves

Like a cat bathing in a patch of sunlight. Pines cluster together, Towering above.

Bluffs rise on either side of the highway, And miniature waterfalls cascade down, Weaving and flowing like the road ahead. The natural landscape soon flattens out, Giving way to flooded fields of rice.

Herons, geese, and ducks gather, Gossiping about the late arrival of the cold.

The farmland stretches for many miles, With decrepit barns crumbling to the ground, Horses and cows grazing in fields, Ghosts of former houses lost to blazing fires years ago.

Homes with junk overflowing in front yards

Appear more frequently, like the items within.

The packrats are always at work, Collecting Gathering

Storing. Rusted cars, Tractor parts, Old play equipment, Christmas decorations, Gardening tools, And piles of trash and yardwork to burn later; The yards never cease to be full.

Old gas stations, long in misuse,

Appear every 10 miles or so.

Places once well-known, likely, Now just a hint of their former glory. Even more frequently, yet, Are the churches.

Churches on every block, More than one church on every block.

Baptist, Methodist, Jehovah’s Witness, Catholic, And some more Baptist, And some more Methodist. I may not be Christian, But I know a beautiful church when I see one.

The silhouette of downtown emerges, City and nature embrace as one. The Natural State.

We truly do have the best sunsets. The time for family gatherings and parties Has arrived at long last. We’ll slip into a drunken stupor, Singing along with the speaker Which blares out the familiar warmth Of Hank Williams Jr., Otis, Aretha, Zepplin, Dylan; We cover the spectrum. Spinning, Twirling, Hugging, Swaying,

The night is chilly, but there’s a fire, There’s booze, There’s dancing, All enough to keep a Southern girl warm. Relationships and connections are rekindled, Stories are shared, Life updates are rattled on, And futures inquired about. The festivities are maintained All through the evening— Here comes Yokem and David Allen Coe! Sway by the fire!

Sing at the top of your lungs!

Don’t let your aunt fall into the flames! Grab her, hold her tight, and sway some more!

This moment will never end. We laugh, We cry, We have a moment of fear, But it all comes back ‘round. In another few days, Weeks, Months, Years, We’ll do it all again. Love spreads through the food, Through the question, Can I get you another drink? Why, yes you can! Through the hugs, the gifts, the bickering. In drunken passion, I dance in my socks under the starlight, Twirling between my mother, My cousins, My aunts, My grandma; Grasping each hand, knowing each one helped raise me, I wouldn’t trade the world for this one moment, This small blip in the universe Because this is home.

Resana Zayan

Elijah Lehmann

There is an articulate poem within the confines Of manual labor, in the sanguine sweat of digging. With dirt and dust, and its dismal displacement. I learned to hear this poem in the wails of my hammer, Which was covered in rust and had loose leather straps. It whispered to me in the obtrusive rattles of the jack hammer And ingrained itself in the grime that resided under my nails. This art was as malleable as the nails, bending to my will. It melted into the wood, the trees, and the unending ground.

Some days I lost it, in my hubris and hate filled pleas for rest, In my prayers for the sun to rise and then trip and fall. Time solicited my anger with its dragging and draining nature. Time was the enemy, carefully curated to distract and dismay me.

But there were full breathed, heart beating moments Where the conception of a clock subsided and truly I existed. I looked outside, truly searching the canvas outstretched before me.

It was beautiful and breathtaking. I worked some more. The shade became a blanket of rest and restoration, the breeze hit me

Like an ice cold glass of water. I worked some more. My task set before me was God ordained, I was Sisyphus, pushing my boulder in blissful contentment, I was Atlas, holding the world, and all the broken hearts.

To boldly exist was not written in any job, or any title. All it takes is the grip of attention and the consistency

To show up, again and again, amidst the desire for more. Love, glory, passion, anything worth the Lord’s attention Was mixed and settled in the firm resolution of “here am I.”

Edie Meehan

I woke up this morning with an ingrown toenail so painful I couldn’t walk. The same thing happened yesterday, but with a particularly gnarly leg cramp. It’s times like these I have to ask myself if I’m falling apart altogether.

Since I was a child, I’ve proudly told anyone who would listen that I’ve never broken a bone. It seems kind of silly when I remember everything I have hurt: stitches on my chin, scars painting both legs, a twisted ankle that made me see stars.

In pre-school, I once had a hangnail that caused my thumb to bleed – not even enough to flow down the finger, just a bright line of red along my cuticle. I remember gazing at my cracked thumb in morbid serenity, having accepted right away that I must be dying. I couldn’t tell you what that assumption says about my early childhood. I had a flair for the dramatic, clearly, but was there something deeper to that? Maybe for the best that I didn’t share these thoughts with my mother at 4 years old; I turned out just fine. Mostly. Like any of us have.

When I was maybe 10 or 11 – young enough to want to impress the older girls, old enough to have to try hard – I jacked up my wrist with an overly-ambitious cartwheel attempt. The others were just so good, so graceful as they spun through the air, their flat stomachs proudly exposed as they stood on their hands. I thought I could do it too, and I slammed my palm into the ground with my full bodyweight on top of it. The pain would come and go for months, sometimes forgotten until I bent my wrist wrong and couldn’t hold a glass of water for the rest of the day. Expecting a minor sprain at worst, I finally asked my doctor at my next regular checkup. “I don’t think it’s broken,” she said. I wondered if I had been undermining my pain all along.

There are other pains, too; some are invisible to the eye, known only to me. Some aren’t so physical. A sense of shame, for example, that has followed me since I was five years old. It’s truly impressive what a group of young kids can teach you to hate about yourself. My former speech impediment and lack of friends my age were only two such casualties. A neighbor used to have a hammock we would all fight over, the rules stating only two at a time. One older boy refused to let me on with him because I was, according to him, equal to five people in weight. Awful, I know, but so distant now I can only laugh at his absurd cruelty. The shame persists, regardless.

Another hidden pain is harder to describe. A mismatch, an isolating feeling of difference that has ebbed and flowed in me since middle school. You can call it dysphoria, but that almost minimizes it. It’s so much more, nothing so simple as to fit inside a word. The feeling is deeper, always changing but always there. I know who I am. I think I do. Labels have come and gone with the past several years, and I’ve all

but given up. The best way I can describe myself, lately, is not quite a woman. That term, that ‘not quite,’ sums up a lot of my experiences.

I see a group of girls my age, laughing amongst themselves, and I am not quite one of them. They talk about boys, they talk about girlhood, and I am not quite one of them. It’s hard, and it’s strange, to be among those who are meant to be my peers. Time spent in treble voice ensembles renders me an imposter among proud women. Using female bathrooms puts me in fear of coming off as predatory. Even small moments with my female friends leave me feeling out of place; do I belong here? Am I meant to laugh at their jokes? And always, always, I wonder how they see me. Sometimes I ache for it, sometimes I just want someone to understand, but I am never quite one of them. There are a number of reasons for this.

One is the poodle skirt I wore in a high school production, my crinoline falling down my hips. I had mandatory shapewear, too, which pushed my stomach flat and pulled me right out of my body. Like it was yesterday, I remember waiting backstage and feeling this insatiable itch underneath my skin, wondering if I would ever recognize myself in the mirror.

Another reason is the corner of the girls’ changing room, where I would fold in my elbows every time I had to take my shirt off. By the time each show was done, I was a shell of a person; full of joy, of love, of music, and with no clue who I was. Every night, I shed my costume for another. Off came the skirt, the scarf, the teased-to-heaven hairdo, but I could feel the crinoline still. It’s there even now –scratchy on my legs, never fitting right, a ghost of the mismatch that I’ve worked so hard to leave behind. When I make a prison of these memories, I remind myself how far I’ve come. I remind myself of how far we’ve all come, because we all have our crinolines. No one is free of that itchy reminder that we are human, in every way that limits and frees us. We’re all living in these vessels that crack and stretch, bend and break, settle and sigh. We are all bodies; we are all inside bodies. We do not control – not entirely, anyway – what happens to them. We are all, to put it crudely, sacks of meat just trying to make it through this funny little tragic life. We can assign meaning to whatever we want, we’re prone to do so, but the physical doesn’t change; we have one chance with this body. No one comes out unscathed. But no one comes out alone.

Last week, I went out dancing with my roommate and a few of their friends. I don’t tend to go to parties, I don’t tend to dance in front of others. But I went, and I moved my body, and it was imperfect, and it was splendid. The light of 50 glow-stick necklaces and the sound of my friends screaming the lyrics to our favorite songs; these are the details that stick with me, the only ones that matter. There was an air of discomfort, of uncertainty, but the music drowned it out in the end. I promised (to them, to myself) to go again soon.

Maybe it’s not meant to always be comfortable. Maybe my body can ebb and flow with those hidden pieces of shame, with every other feeling that maintains impermanence. Maybe we are not meant to ever be the same. I still think a lot, often when I don’t want to. My legs still get itchy. But I’m tired of worrying whether my stomach looks flat, whether my body language is socially correct, whether the way I walk looks cool. When it’s dark, and everyone is half-drunk, dancing really doesn’t have to be beautiful. You just have to keep moving.

Noah Arndt

Maggie Bruck

lost and trying spirit, marooned, yes, but shining like ruby

holding a locket: one last treasure for the journey deserted, to die between the burning sand and navy sky

you’ve searched the rolling dunes for another way deep within the cosmos you have seen a blue kind of heaven

through teary eyes your waning spirit seeps back into the stars.

so with trembling hands and fighting feet on desert sand, if your heart begins to whimper like a mourning dove

and you cannot lift your bag of bones, open your lonesome heart like that locket

and see the gold: the pane of old love, moving sweetly on.

Resana Zayan

Ashley Imdieke

There is a certain strength that comes from going to the gym And being the only woman in the free-weights section.

There is a certain strength that comes from being muscular, And in embracing it as feminine.

There is a certain strength that comes from being loud, And in not letting your voice be ignored.

It is a strength that cannot be expressed in numbers, A strength that comes from within.

It is a strength that is both bitter and sweet.

Choreography: Avery Wrage, Ashlynn Thorsen, Ava Johnson, Hannah Batterson

Videography: Finn Wallace

Dancers: Hannah Batterson, Annika Evanson, Ava Johnson, Rose Martinsen-Burrell, Ashlynn Thorsen, Lilly Timm, Avery Wrage

Artist Statement: With this piece, we wanted to emulate the perception we experience as young women, both from ourselves and others. These experiences bring about many emotions such as self-love, selfdoubt, anger, comparison, and empowerment.

Orchesis Dance Group

Choreography: Ashlynn Thorsen, Avery Wrage, Skyler Schneider

Videography: Finn Wallace

Dancers: Hannah Batterson, Lily Chen, Ava Johnson, Linnea Hedin, Skyler Schneider, Ashlynn Thorsen, Chalya Velander, Avery Wrage

Artist Statement: In this video, we aimed to bring dance to new spaces on campus and express feelings of joy through funky moves and aesthetics.

Edie Meehan

From the first gasp of life

To the very last sigh–This, too, can carry death.

I used to swim until I almost drowned, Gasping on the pool deck Like some sort of addict–Always pushing, pulling, Reaching for more than I have.

I sing until I’m bent over, Lungs caving in, Crawling top-speed through the barline. Everything I do, dependent on breath. You’d think I’d have enough to go around.

There’s a cactus in my bedroom; The first little green thing I got to call “mine.” It grows slowly, pricks my fingers, And like the rest of us, Sits there and breathes.

Clara Wodny

Teardrops like acid leave burns trickling down– who are you to cry? if you keep it up I will give you something to cry about you see your hurt is not valid if it means someone has hurt you you are being dramatic and making yourself sad only you control your emotions get a grip cover them with makeup but you are powerless everyone says you look just like me it is impossible to see a way out when you committed the crime I love you choke on your words then swallow the bile– it is what you deserve for your petulance I love you just a child but somehow you are destined to live wrong and fail everyone aren’t you going to say it back?

Sea Orme

Slumbering deep in the roots of trees, a lost tooth twitched.

It had long been cradled by sweet soft pine, bitten bitter by icy wind, steeped in snow. Over the years it had softened and stretched into a cocoon of human-shaped proportions– now, it cracked and split. The outer layer of enamel peeled fresh from its form as a soft, fleshy body clawed free. Writhing upwards, it strained into frozen air like a sprouting seed. Newly-formed fingers of fat and muscle dragged it from the soil; matted black hair clung to its scalp and blind eyes fastened on empty air. It gasped a breath, cheeks glistening red from the sting of wind and wet snow.

Norway’s winters were vicious creatures. All around, craggy mountains sported bruises of black and white rock, fjords bristling with spikes of ice. Clumps of trees clustered together in valleys and sprawled along sloping hills, scraggly giants reaching for the burning blue sky. The body could see none of this. Even if it could, it wouldn’t have mattered, because the body had no mind for anything but its hunger.

A ravenous emptiness ached hot in the very marrow of its terrible being, urging it forward on hands and knees. One particularly puffed-up squirrel decided to investigate this strange, new creature, only to promptly turn tail and scrabble for shelter in a nearby bush. The body was not offended by this, because it did not have room within itself to feel something so human as offense.

It was at this point that a crow entered the scene. It was not an elegant entrance, but a clumsy one, befitting the last surviving member of the Kråke clan.

Blinded by blood and rage-born panic, it was fortunate for both Kråke and the body that he happened to slam into the body’s unseeing face rather than a tree. Blood and feathers went everywhere, but mostly onto the body’s face. Kråke toppled backwards, plummeting into its lap, a bewildered mass of twitching feathers. It was a true miracle he wasn’t immediately devoured.

As Kråke recuperated, the body found itself at a loss for how to respond. Its hunger had been momentarily destabilized. Its smooth, featureless mask of a face contorted in a silent sneeze, the bloody smear of feathers dripping into its blank eyes. It sniffed, straightened, blinked, blinked, blinked. Pools of inky black coalesced into dark, bottomless pupils, set wide and wondering. She stared upward. Nothing but sky. Stars clustered in silver whorls, flashing like scattered coins in a fountain. They danced in a joyous riot around their silent, glowing queen. It seemed to the body– to whom we will henceforth refer as Kaia– that her head was full of bells. All she could hear was a bright ringing. All she could see was the moon’s light. Her hunger had been fully replaced with an odd, squeezing pain that seized her chest and tugged her up, up, until at last she was kneeling, gazing at the moon and plotting out how to grow wings.

“Who am I?” she murmured. Leaves flickered overhead like paper fire, rustling in soft applause.

“Well. Do you believe in God?” asked Kråke. He jutted his beak towards the moon. “Måna.”

Kaia silently sank further into her kneel, eyes awash in moonlight. Her lashes gave a light, flicking twitch of a startled cat’s whisker as Kråke nestled deeper into her arms. Softly, he began to sing, feathery throat bobbing:

“Den himmelske lovsang har rikere toner, mer liflig og sølvren en klang –enn all jordisk musikk, skjønt vårt hjerte seg fryder når skogen og dalen gjenlyder av sang.”1

–Revelations 7:9-12,” said Kråke, once the remnants of his verse faded into the dark, glittering landscape. “Do you know what a revelation is?”

Kaia did not, but she thought it sounded exactly how she felt. The throaty vibrations of the hymn had imprinted on her body, thrumming it to life, hot and urging. She gently set Kråke aside. Her heart thumped unsteadily with unfamiliar fervor, and she did not want to crush him by accident.

“Do you believe in God?” Kråke asked again from the ground, craning his head to the side. He hopped once, twice, before exploding in a flurried burst of wings from the frozen earth to the low limb of a tree. He peered down at her, eyes glinting like black marbles.

Kaia looked at her hands. They were good hands. Strong hands, thick and tough with layers of calluses, intimately familiar with the labor of digging. Her palms remembered the scrape of rock and scramble of many-legged insect, and it felt right to thrust them into the ground. As she dug, she patiently escorted an assortment of insects out of the deepening hole.

“If thou have all faith so as to remove mountains, but have not love, thou art nothing,” Kråke dictated, fluffing his feathers intently. “1 Corinthians. 13.”

“Do you not have anyone else to talk to?” Kaia asked, abrupt and rude, though not intentionally so. Squatting beside her half-finished hole, her fingers were caked with layers of dirt and gritty snow. She looked up. She squinted. Kråke was nothing more than a charcoal, feathered smudge against dead white branches.

“Perhaps.” Kråke sounded odd. She looked up.

“Are you crying?”

Head tucked beneath his wing, Kråke didn’t respond. Kaia peered at him for a moment before her gaze returned to Måna. Instantly she was gone. Her arms hung listless at her sides, fingers muddied and eyes aglow. Watching her from underneath his wing, Kråke felt the first dark itchings of unease.

1 The music of heaven has richer voice

More lovely and silver a sound–Than all earthly music, though our hearts rejoice When the forest and valley sing ‘round.

“Our light and momentary troubles achieve an eternal glory that far outweighs them all,” he muttered, sidling closer to the shelter of the tree trunk’s shadow. “Corinthians. Do not lose heart.”

He flinched at the confused cry that shot through the dark, piercing his breast with its intensity. On the ground below, Kaia had suddenly collapsed into herself, wailing and clawing at the ground. Kråke did not bother looking up– he already knew what he would see. Måna, veiled in clouds. Måna fraværende.

“Do not lose heart,” he muttered beneath a second scream. Soon the night would shift to morning and Kaia’s object of devotion would truly vanish. He knew it would be worse, then, and as spears of light splintered the trees, indeed it was.

Kaia’s screams splintered through the sun-dusted sea of trees; specks of scabbing blood shone like jewels on her lips, parted, cracked, dry, split from clawing nails. She’d torn out chunks of her skin and hair, too, rendered senseless by the sun. Lines on her arms and legs– stomach, chest, cheeks– oozed thick, dribbling pockets of blood. The snow glistened below her kneeling form. A lone leaf lay wet and dark atop the snow’s crusted surface.

Kråke watched her from a safe distance as she coughed up blood. Snot and tears dripped fat off her chin. Each breath was a raspy, rattling thing. Each exhale emerged on a sob. The hole was gradually darkening, snow and earth damp with muddy crimson.

“Do not lose heart,” Kråke murmured for the nth time– for the nth time, Kaia ignored him. It would’ve been more startling if she hadn’t, given the wordless, weeping beast that she’d become. “Do not lose heart.”

Kråke was quiet for a moment, before he said, “It is going to rain.”

Kaia ignored him.

“Fy faen,” Kråke muttered to himself, before taking off and vanishing into the trees like a wisp of smoke. Cutting beneath a pine tree, he clipped a branch with his wing. Snow exploded like ocean spray, suspended midair before cascading apart in glittering sparkles. He sneezed, shaking ice clumps from his feathers. Clacking his beak, he sent up a quick, thankful prayer to the LORD, warbling an unintelligible hymn as he continued on his way.

Unmoving, Kaia listened to his wingbeats fade. She stared at the ground, listening to the breathing of the trees; the rustle and rasping slide of their shifting roots beneath the soil. Her chest felt pinched. Her eyes itched with heat, salt stinging her numb cheeks. The vastness of her environment pressed down on all sides– she was alone– and her breath quickened. The sun was glaring down at her like some giant’s awful, yellowing eye. She kept her gaze pinned to her feet as she hurried over to the shade’s safety. Snow crunched beneath her feet, coolness slipping over her like a thin slip of satin. She fell against a tree, gripping the peeling bark. It reminded her of herself– skin bloodied and coming apart in chunks of clumpy, hardening scabs.

For no particular reason, she brought her lips to a low-hanging branch and kissed it.

Noah Arndt

Sorley Swanstrom-Arnold

taking a rest before it heaves another bucket over the lip of the sky. We’re resting too, before we heave ourselves to work again.

The birds outside our window invite the sun to reach down and grab small fistfuls of grass.

Let’s go for a walk, you say, Before it starts again.

The air is thick and it makes our skin and clothes damp with dew and sweat.

We jump over pools that form at low points of sidewalks and kick through rapids that flow through the gutters and into the drains and into the streams and into the lakes.

Thunder cracks and rolls a few miles away, in clouds too fast to tell whether they’re coming or going.

Ethan E. Nelson

I remember exactly how you were dressed, the way you stood, the look painted onto your face

The first time we shared our names.

Such a simple introduction there was, neither one of us understanding the exposition of us that came with our names relative to each other;

Like fish not realizing the importance of the ocean that surrounds them.

The first time we shared a laugh, our song’s first chords manifesting over a remarkably, yet hilariously, anserine thing;

The way your eyes opened wide, water lilies in full bloom.

The lines around your cheeks forming into a beautiful frame, inside of which was exhibited the gleeful smile of a 5 year old who gets to talk about their favorite dinosaur.

Your light, airy giggle carrying and growing like sound over water,

Whilst sun-warming my pale, lonely winter skin.

I remember most laughs we’ve shared since.

I remember the first time I shared my secret with the universe, the first time I gave it life in words which have resided since then in my head,

I want to share more with you, like how sun shares life with the plants,

I want to share the Shakespearean sonnets of sappy situations I romanticize with you.

I remember sharing exquisite journeys and experiences, unique and rare,

That only few ever get to see;

Rarer than snow on a beach, and more breathtaking than the northern lights dancing in the sky.

Most importantly though, I remember the first time we kissed.

The fuzzy glimmering waves of appreciation and understanding, rising, dancing, and swelling between us

Golden; which was untarnishable in spite of the world.

The warm feeling of your face sitting in the palms of my hands.

The shared eye contact after sheepishly pulling away,

Your sparkling eyes shooting down for a second, shyly, yet

The joy was unable to hide itself on your face.

Without moving or talking, I felt the tide pull me back in, you wanted to share more about us.

I remember sharing memories of previous stumbles and encounters,

As mine were fuzzied with age and ignorance, while yours were clearly in color and focus;

I clearly couldn’t see the beach and how it was formed, but you could,

You can describe how it was created, describe how the life began there,

Describing all the pastels, shapes., and forms

You’ve shared a beautiful image that I was blind to for so long,

It is wonderful.

I remember a lot more now.

All the ways we felt about each other, shared openly and freely, basking over us as we lay and look up at the sun;

Our handmade beach keeps us warm and makes us sleepy.

Now, we’ve shared a lot of materials and work in our joint construction of a sandcastle here,

And now the foundation is firmly set,

Let’s share some eccentricly ambivalent blueprints. We can make the best sandcastle ever seen,

It’ll be fun,

Constructing a gorgeous cathedral of parallel play. Sharing ideas separately and silently while it is built in Unison.

Trust instructs our architecting, like an albatross leading a lost ship to land.

You keep leading, venturing first to a new world,

Your sandy footprints easily visible all around us. I like looking back on mine that led me

Here to take your hand.

Edie Meehan

I bought you roses that you never saw. They sat in my kitchen, wilting While I waited for courage to find its way to me. Love’s just a feeling, they say, Chemicals in the brain, A drug like any other, maybe. But you and me, Christmas lights in the early dark, Laughing like we’ve never cried alone before–Maybe we can turn this thing around.

We are not easy people; We both know it.

We are not people who have had it easy. Salty tears staining my shoulder, Those tiny bulbs flickering as you promise I’m not crazy, But I feel it, oh, I feel it sometimes. Never enough time, never enough sun, Vitamin D popped like something stronger When the sky goes gray.

You told me once that I could never let you down. I try not to treat it like a challenge, But I can be something ugly. Call it a promise, call it a curse, Call it famous last words.

All I know is I like the way you look at me When no one else is watching. It’s enough, I think. To last forever. Longer than those Christmas lights, at least.

Sorley Swanstrom-Arnold

He built this garden a couple of years ago. While listless and unanchored he put a shovel to dirt and saw to wire. The beds are only a few feet from the RV that he slept in that summer. Now home to rats, mice, and boxes of abandonment.

The garden is made up of only a few beds, built with some of the excess 2x4s that scattered the acres of wood and lawn. In addition, there are a few aged tractor tires dropped on their side that serve as smaller homes for the hoped for tomatoes and peppers.

To keep deer out, he built a wire fence around the garden’s perimeter. Again, using leftover metal. He looped the chains around spiked metal rods and large craggly branches fallen from the trees killed by burrowing insects like the spruce budworm that are decimating the Northwoods. To further deter potential raiders, he fixed spoons and empty cat food tins that would rattle in the wind. Looking at the fort now, one side is caved in, evidence of a doe crashing her body against the wall to feed herself. The spoons didn’t work.

When he built this garden, it was lively, bright, and organized. Dark green vines curled around sticks and poles pierced into makeshift beds, bulbs of red, green and yellow beginning to form. Waxed and shiny leaves grew from the tractor tires, nurturing tiny red arrows that would burn your lips, the same kinds he tricked me into eating at a beachside restaurant when I was four. Running the lengths of one the 2x4 beds were the green bunches of carrot tops. Out of another sprouted the smooth leaves of potatoes that round to a point at their tips. Living alongside the vegetables were wildflowers. Asters with long, soft, watery purple pedals extending from yellow hearts. Hawkweed flowers jumped out at the edges of the small paths like red dwarf stars. He could have pulled some of these flowers, like we used to do when we got paid $10 for a day of pulling weeds and other undesirable plants from the grounds of tourist condos in Bayfield. But he didn’t. Perhaps, like his thoughts on fences, he didn’t want to keep out what wanted to be there. People say hawkweed hurts the growth of other plants, I don’t know, but that garden grew damn good carrots.

That garden was like a bustling city, but with much smaller residents, more efficient traffic, and less concrete. Bees floated from flower to flower, listing back and forth, encumbered by their abundance of pollen. Butterflies would dart past your face, land on a nearby stalk, and stretch its wings. Flared out like pages of a book, they would shake in the wind. Crickets jumped through the dry grass in between the beds. If you looked closely at the beds; mites, worms, and slugs could be seen tunneling through the dirt and climbing the green towers. Like a city too, there was always noise, incessant, infuriating, comforting noise. The hum of engines, cry of sirens, and hissing of buses was replaced with the buzz of crickets, the chirps of birds, and the shaking of leaves.

It had a smell of its own. In the mornings it smelled of fresh rain. Summer mornings on the lake always smelled like fresh rain, when the dew weighed on the green grass and gray clouds hung heavy at the level of beasts. By midday, after the sun had had its time to clear the fog, the garden was pungent and sweet. The soft, dark smell of dirt joined with the bright scent of flowers. Always, it held faint notes of rot coming from the compost pile in the back corner. Black coffee grounds, white egg shells, and browning banana peels stacked high on eachother, his food slowly becoming the foundations for his next meal.

Standing here now, the vision of what this garden used to look like doesn’t match what I see. The wire walls are caved in and sagging, rusted from just a couple years of Minnesota snow and spring. The tidy paths have been overtaken by thick crowds of grass that reach up to my knees. In the beds are a mix of unwieldy vines and assertive weeds, not a single grain of brown dirt is visible past the oppressive green. It is impossible for me to step into the garden. The grass, thicker than wild Iowa prairie, acts as a more formidable barrier than Finn’s fence ever did. The noise, always present at the garden’s birth, is now unrelenting. The buzzing of crickets and bees is amplified by their sheer number, although their forms are now hidden by the veil of emerald. I am also convinced of the presence of ground wasps, whose nests explode like landmines in a swarm of stings and bites when stepped on. Also, the potential of snakes to be hidden in the tall grass gives me pause. I am not bothered by snakes, when I can see them, but they may as well be a basilisk when hidden. Who knows, I think, maybe a timber rattlesnake made its way north, and is lying in wait to pierce my exposed ankle.

This isn’t the first overgrown garden this family has left behind. When our home split apart, the greatest tragedy wasn’t the anger, guilt, or hate. It was the lilac bushes that grew without guidance and now fail to flower. It was the terraced beds that once housed bright little suns that, with our care, prospered alongside the wild weeds. It was blackberry bushes behind the house that no longer give fruit, now swamped by grasses it never knew. We tried again in our new home, filled with a thick haze of confusion. For a few years, Mom put her hands into the dirt of the small plot in the backyard. She coaxed lettuce heads, pulled carrots, and held back the tide of the oncoming raspberry bush. But after those first few years, once we realized the haze wouldn’t lift, the blue tarp that protected the soil from winter’s freeze stayed over the beds once summer came. Now, if I went back to that duplex I’m sure the raspberry bush, with its tiny red stars, would be covering the entire garden, allowed to expand without resistance.

At one point, after Finn had left for school in Vermont, trading one deep woods for another, a thistle emerged near the garden. Neither of us, Mom or I, had noticed it until it was at least 4 feet high, with 5 inch blades sharper than any needle pushing out in every direction. Out of interest for the dog, Huckleberry, who I knew would eventually either try, I took it upon myself to remove the spiked tower. Armed with double layers of gardening gloves and industrial sized shears I cut the thistle at its base and dragged it to the compost. The gloves did next to nothing to stop the needles and I was losing tiny drops of blood from tens of little pin holes. For the next few days my arms, legs, and hands were red with marks of struggle. The thistle might have grown back by now, taller and sturdier than ever, ready for round two. I won’t

be in the ring though, I didn’t stick around long enough. Now, with a battery powered weed wacker in hand and clear protective glasses over my eyes, I stare at the wildness in front of me. The pause given to me by the thought of wasps and snakes has subsided, and I am ready to confront Finn’s garden. I have no desire to tame the uncontrolled jungle that was his work, I only want to nurture it. It’ll grow better, for myself and for the deer, if I take in some of these weeds. I also want to honor Finn, I’ll name it his Memorial Garden. He’s very much alive but I do think we should make more memorials for living people. This garden deserves better care than it has gotten since he left. I’ll cut the weeds back today, clear the paths between the beds, and start pulling tomorrow. By the end of the week I’ll have a blank slate to start the garden again. With weedwacker in hand, swinging back and forth, I enter the grass.

…

By the end of the day, the edges of the fence will be clear of towering weeds and a small beachhead will have been established at the garden’s gate. But I will get only so far. I won’t pick up the weed wacker again that summer; life, work, the stuff I have to do, will get in the way. The beachhead will slowly be swallowed by dandelions, hawkweed, and tall grass. Some mornings, I will notice the garden getting ever more out of control, other days I won’t see it at all. In three months I’ll be gone again, like Finn, to a place where fog hangs lighter; and his garden will grow wilder.

Ruby Zorn

The loss of a grandmother Is first —

Your childhood forever frozen in the past, Stored away in memories

That will eventually grow foggy with time.

How do you say goodbye

To one of the women who raised you? Who stoked the fire in your belly

For your passion and love?

How do you say goodbye

To the suddenly frail woman before you, Who can’t seem to remember you’ve grown; Your youthful blonde hair

Had since turned a mature brown, But she never could remember.

The loss of your family Is second —

You never realize how tightly you hold on to Something so invisible

Until it disappears before your very eyes.

How do you say goodbye

To not a person, but a concept?

To ghosts of laughter, Memories of embraces, Fading photographs, And the comfort of unity?

You should have seen it

When the arguments grew more frequent, But it only dawned on the final one.

You should have known better

When you saw the glimmer of hope

That it would be extinguished once more, Leaving your soul damp with despair.

How do you say goodbye

To the corpse of that past

Which you hold tightly onto In hopes that you have the power to reanimate it.

But you know that even magic couldn’t fix how you feel.