On Mentors and Mentorship: Remembering Nadine by NICHOLAS SHANEYFELT, Assistant Professor of Music

N

NOVEMBER 10, 2021

ovember is a month of remembrance—a time to honor those we have lost. Many of us haven’t had a chance to properly— publicly—acknowledge these losses since the pandemic began. Thankfully, I didn’t have to endure the loss of a family member during COVID, but it was the loss of my mentor, Nadine Shank, that shook me. I’d like to tell you about Nadine, and a visit I paid to her not long before she died. Nadine was a student of legendary pianist Menahem Pressler at Indiana University, and she began teaching at the University of Massachusetts in 1981, when she was just 25 years old. I met Nadine in 2009, when I was 22 years old, fully determined to be a pianist with a solo career. But I think she sensed all along that collaborative piano was my destiny, and her influence steered my career path toward a life of collaborative music making. Fast forward to 2020. It wasn’t a COVID diagnosis that claimed her life, but a rare degenerative brain disorder known as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, CJD. Think Lou Gehrig’s disease of the mind. It’s awful. Diagnosis to death is one year on average. For Nadine, it was seven months. When it became clear that her days were numbered, I resolved to visit her for the last time, in August 2020, when the world was still wounded by COVID. If we were given anything during the pandemic, it was the gift of time. On the drive to Massachusetts, I imagined how good it would be to reminisce with Nadine and to enjoy a long catching-up conversation. By the time I arrived, she communicated only in short, labored sentences, struggled with basic requests, sometimes resorting to gestures (like grasping her wrist for “where is my watch?”).

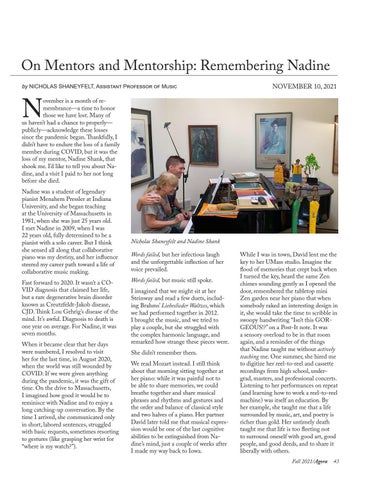

Nicholas Shaneyfelt and Nadine Shank Words failed, but her infectious laugh and the unforgettable inflection of her voice prevailed. Words failed, but music still spoke. I imagined that we might sit at her Steinway and read a few duets, including Brahms’ Liebeslieder Waltzes, which we had performed together in 2012. I brought the music, and we tried to play a couple, but she struggled with the complex harmonic language, and remarked how strange these pieces were. She didn’t remember them. We read Mozart instead. I still think about that morning sitting together at her piano: while it was painful not to be able to share memories, we could breathe together and share musical phrases and rhythms and gestures and the order and balance of classical style and two halves of a piano. Her partner David later told me that musical expression would be one of the last cognitive abilities to be extinguished from Nadine’s mind, just a couple of weeks after I made my way back to Iowa.

While I was in town, David lent me the key to her UMass studio. Imagine the flood of memories that crept back when I turned the key, heard the same Zen chimes sounding gently as I opened the door, remembered the tabletop mini Zen garden near her piano that when somebody raked an interesting design in it, she would take the time to scribble in swoopy handwriting “Isn’t this GORGEOUS!?” on a Post-It note. It was a sensory overload to be in that room again, and a reminder of the things that Nadine taught me without actively teaching me. One summer, she hired me to digitize her reel-to-reel and cassette recordings from high school, undergrad, masters, and professional concerts. Listening to her performances on repeat (and learning how to work a reel-to-reel machine) was itself an education. By her example, she taught me that a life surrounded by music, art, and poetry is richer than gold. Her untimely death taught me that life is too fleeting not to surround oneself with good art, good people, and good deeds, and to share it liberally with others. Fall 2021/Agora

43