DESIGNING ACROSS SCALES THE POTENTIAL OF OUR STREETS

DESIGNING ACROSS SCALES THE POTENTIAL OF OUR STREETS

exemplified by re-thinking munich`s old city ring road

table of contents

Preface / 01-08

designing across scales / 01 why do humans move / 02 history of the street / 03-06 the potential of the street / 07-08

City Scale / 09-12

analysis of public transport, bike infrastructure and climate hazards / 09-10 understanding the ring road / 11-12

Site Scale / 13-20

transformation in detail / 13 historical context / 14 aerial overview and key buildings / 15-16 deficits and potentials / 17-18 design proposal / 19-20

Neighbourhood Scale / 21-22

transition zones / 21 - 22

Site Scale / 23-26

transformation in sections / 23-26

City Scale / 27-30

design proposal / 27-29 masterplan / 29 design result / 30

Adaptable Scale / 31-32

generic toolbox for street re-design / 31-32

Conclusion / 31-32

re-imagine the status quo / 33-34

References / 35-37

Technical University of Munich

Chair for Building Technology and Climate Responsive Design

Streetless - Designing for a post-car city, Winter 2021-22

Luisa Amann & Alicia-V. Hergerdt

DESIGNING ACROSS SCALES

“Streets comprise more than 80% of public space in cities. How can we utilise them better so that they stop contributing to climate change, but become catalysts to transforming our cities in favour of people?”

Chair of Building Technology and Climate Responsive Design, TUM

Pondering about possible answers, another question arises: What do we actually mean when we use the term “street”? In order to acquire a more profound understanding of the related context, this project begins by performing a historical review: How have road networks, its function and meaning changed over the centuries? Was valuable knowledge lost and should be re-introduced? Were mistakes made that now need resolving? Based on the retrospective’s learnings, a vision is drawn up that explores the large potential lying dormant in all our cities: re-thinking the urban streetscape. Though intended as an

integrated system design, the project focuses on one site in particular: Transforming Munich’s inner city ring road (dt.: “Altstadtring”). Following an evidence-based design approach, existing deficits and potentials are analysed in detail. Generally, three thematic areas are distinguished: mobility, climate and urban fabric

The subsequent design evolves across different scales: from specific site scale, to neigbourhood and city scale. Finally, a generic toolbox is contrived, which can be applied anywhere (adaptable scale).

The most important goal to us, as aspiring architects and designers, is to communicate concepts in a way that is easy to understand, enjoyable and people-oriented. If anything, this project hopes to visualize opportunities, spark new ideas and start a knowledge-based discussion about the challenges that lie ahead. With this in mind, let us begin.

Why do humans move? Everything moves - from microbes, birds, continents, to trees and humans. In fact, locomotion has been the driving force of life on earth. From the very beginning, organisms with the ability to explore their environment had access to resources that others didn’t. In addition, they were able to move from place to place. Should any mishap befall them, they were more likely to survive. It has been argued, that the human brain is meant for locomotion, first and foremost. The nervous system is built to steer us around and navigate in unfamiliar surroundings. Movement allows us to find out more about our surroundings and ourselves. It causes us to employ our senses. Humans are bodies and bodies are movement. For those many reasons, motion can be seen as rather normal instead of exceptional. Physical activity oxygenates the blood. Memory is enhanced by motion, which links it inextricably with knowledge.

These key benefits are however all undermined by the car, which furthermore causes pollution, fatal accidents and is a major contributor to global warming. WHO estimates 1,25 Million people are killed in traffic accidents every year. This number does not account for deaths caused by pollution or inactivity leading to obesity. The car has changed the way we design our settlements. We live more and more distant from each other. Often, private life and work take place in very different locations. Family and friends are far away or even abroad. This makes us feel isolated and breaks the link with our biological heritage. In a National Geographic article, Matt Wilkinson, Cambridge evolutionary biologist states: “Travel time has become wasted time.” Can we not imagine a different world, where our modes of movement do not threaten, but positively impact life and health of everyone? After all, motion is essential as to what makes us human.

WHY DO HUMANS MOVE?

2 1

ZOOM-IN

everyday, we experience patterns of space that have been created by us, but not for us. time has come to acknowledge and change this fact. we have all the means to actively transform and shape our surroundings towards a world we wish for. the solutions are there. let’s do it.

RE-THINKING THE ALTSTADT(RING)

BLUMENSTRASSE

HISTORY OF THE STREET in

munich and worldwide

Have you ever wondered about what is the actual difference between a street and a road? Interestingly, though mostly used synonymously in day to day language, the two are differentiated in linguistics: While a road’s main function is to constitute travel and transportation, especially over long distances, a street only appears in cities or towns. Its etymology goes back to the latin “via strata”, a term which was exclusively used for paved (“made”) roads. According to Cambridge Dictionary, there are usually shops, stores or houses alongside a street, rendering its main characteristic to facilitate public interaction. But is this its only function?

Where does the history of the street start? The invention of the wheel in Mesopotamia made possible the earliest forms of transportation. With the rise of the Roman Empire, roads became an important means of warfare. Construction technologies were refined and a large street network was built. Even today, many motor- and railways run along the routes which back then were established by the Romans.

In the Middle Ages, Europe was divided into many small countries. Bad road conditions meant that blacksmiths profited by repairing broken wagons, innkeepers by accommodating travellers, the sovereign by collecting their taxes – there was no incentive for road construction. It came to a standstill.

Munich was founded in 1158 along with the construction of a bridge across the Isar, an important part of the salt trade route. An economic center emerged where tolls were collected and trade conducted. The city was surrounded by fortress walls and crisscrossed by streams and canals (divisions of the Isar) which earned it the nickname “Little Venice”. During the 30-Year War, a second city wall was built. The construction of the castle Nymphenburg established a new road axis that played a significant role in Munich’s future urban development.

In the 18th century the situation in Germany became more stable. Global trade flourished. New streets were built all over Europe, using gravel or early forms of pavement. The pedestrian path and first streetlight were invented. The founding of the French National School for Road Construction triggered a flood of systematic innovation and marks a historical turning point. In 1795, Munich was declared an open city. A new urban development phase started with the construction of several major streets.

The 19th century introduced new urban ideals. The quality of cities, the composition of green and public spaces came to the fore of discussions. Bavaria was proclaimed kingdom. The face of Munich was shaped into one that aimed to represent it being a “worthy” residency for the king: open plazas were built, the Maxvorstadt expansion and the Ludwigsstraße were commissioned. In Scotland, the first electric car and the “macadam” pavement were invented.

To take a detailed look at the timeline, please follow the link or scan the QR code.

4 3

MUNICH‘S INNER RING ROAD

Munich’s first railway connection changed the fabric of the entire city. Industrial operations relocated to the central station to streamline coal supply. Munich’s brooks, which previously had been the main source of water power, lost their meaning. Step-by-step, they were closed or relocated to the underground. Europewide, the massive expansion of the railroad network resulted in road development coming to a standstill. In America however, paving technology was perfected and the first road building machinery invented. By the end of the 19th century, the car had become so important for individual transport, that the road regained its meaning. Incentives were implemented to promote street expansion in Europe. In Munich alone, 1,200 hectares of land were given up solely for road construction, an area as large as 30x the Theresienwiese. Europe’s first highway was built in 1924 between Milan and the Comer Lake. The Nazi-regime extended the German road infrastructure. Similar trends are found in the US, where the Federal Highway Act commissioned the construction of 41,000 miles interstate highway.

After the Second World War, various ideas for the reconstruction of Munich and even relocation of the whole city to Starnberg were discussed. In the end it was decided to reconstruct Munich on the old grounds, since the underground network of supply pipelines had survived the bombardment and could be reused.

The new Munich was supposed to be “a city for automobiles”. Plans for three motorway rings in and around the city were realized. A wave of motorization marks the 1950s. Implementing traffic concepts was at the heart of urban planning.

Soon the downsides became apparent. In 1961 Jane Jacobs published her book “The Death and Life of Great American Cities”. Exactly concurrent, citizens in Munich for the first time demonstrated against further road extension. In 1963 Munich was the city with the most cars in Germany due to a lack of public transport. Traffic had turned into a problem.

Finally, policies shifted in the 1970s. Instead of subsidizing motorization, land was now being protected. A new traffic policy limited road construction to “the unavoidable necessary volume”. Numerous road projects were abandoned. In Munich, the S-Train was put into operation and public transport strengthened to reduce pollution. For the first time, public space was wrested from cars and regained by people.

Modes of transportation have changed over time, from walking to travelling by horse carriage, bicycle, automobile and tram. The street is a place for the public, for trade, commerce, socializing and play, facilitating movement between two places.

It serves military purposes and the transfer of information. Nowadays, these lose relevance with the rise of modern technology. In the 19th century, streets were named and organized to optimize taxation. They became a tool of urban planning, a place for public activism and art. Paving technology was optimized and today we mostly use concrete or asphalt to construct our streets.

Where we are today is the result of hundreds of years of development. History shows: the world is subject to constant change. Especially Munich’s inner ring road has had a many-faceted history. Unfortunately, it has turned into a traffic hotspot in the 60s and has remained so until this day. In the 21st century we are faced with challenges like climate change and mega city trends. To tackle these, urban space is required. Subsequently the question arises: Can we utilize the potential of today’s streetscapes, finally free them of motorized, individual traffic and re-design them to help solve the issues ahead?

6 5

v

historical development flooded town moat 1619 open fortification 1803 urban development 1827 traffic hotspot 1957 re-thinking today green belt 1806

THE POTENTIAL OF THE STREET

VISION

bicycle highway

By means of Munich’s citizen referendum “2019 Bürgerradentscheid” it has been promised to establish a continuous bicycle highway along the inner ring road. This has however not been realized yet. It is time to finally do so. water canal Below Munich’s surface many old city brooks flow that could potentially be resurfaced. Their cooling effect can be utilized to increase air humidity in the city center and thereby compensate heat stress in the summer.

flexible space

Substituting traffic allows for various flexible street usages, such as creating interactive shared public spaces for communities, sports, activities, leisure and much more.

What if we thought of the entire city ring as a forest? Trees provide shading, optimize air quality and minimize pollution Greenery furthermore enhances well-being, health and creates calming surroundings. Similar effects in regards to heat reduction can be achieved with artificial urban canopies.

8 7

forest

Unused public space Qualitative space that enhances livability, community and health. No°4 can be redesigned towards... today

a

provide access, facilitate movement and public interaction. A street‘s main function is to... No°1 today A noise, air and heat polluter. A tool and space for climate adaptation. But, unfortunately, over time it has also has also become... No°2 We can change this. The street has the potential to be... CO2 today Individual, motorized transport CO2-free and shared mobility modes. No°3 can be re-thought as... today

vision for change

CITY SCALE analysis

of public transport, bike infrastructure and climate hazards

Public transport connections are good in the city center and would only require little extension in a car-free scenario. S-train, subway, bus and tram connections ensure access for all ages and abilities. Various public transport hubs are situated within or near the ring road, including Munich’s central station, Stachus (west), Marienplatz (center), Sendlinger Tor (south) and Odeonsplatz (north). Bike frequency is high. Indicated below (red circles) are all areas in which over 5,000 bikes pass each day. The numbers refer to a study conducted by Intraplan in 2019 which was commissioned by the city in order to establish a comprehensive database of cycling traffic in Munich. Though demand is obviously there, quality of cycling paths

in and around the city lacks behind. Sometimes bike paths suddenly end or are so narrow that they do not allow overtaking. This renders especially dangerous, when paths are level with traffic lanes and / or cut through pedestrian zones. Regularly, hurried cyclists end up causing or becoming victims of accidents.

In regards to climate conditions, the analysis reveals that many hazards concentrate along the ring road. Large amounts of traffic contribute to high noise exposure and very poor air quality. Little greenery further promotes poor bioclimatic conditions. Most surfaces are flat and sealed, increasing risks of pluvial flooding.

NOISE POLLUTION analysis climate hazards

A lot of traffic along the inner ring road leads to high noise pollution. High density and little greenery further contribute to cause poor air quality along the edges of the old town.

HEAT STRESS & AIR POLLUTION analysis climate hazards

Temperatures have been rising significantly in Munich in the last decades. There are more and more days with > 30 °C and tropical nights. The densely built-up city is becoming a heat island

MOBILITY analysis of public transport and bike

SOIL PERMEABILITY analysis climate hazards

46 % of Munich are sealed, including most parts of the inner city, which gives rise to an increased risk of pluvial flood.

level bioclimatic situation & heat stress unfavorable

RISK OF PLUVIAL FLOOD analysis climate hazards

Buildings located on flat ground on the lower part of a slope or close to rivers are particularly endangered by heavy rainfalls. The large, flat and paved area of the inner ring is particularly exposed to pluvial flooding.

10 9

buildings green space forest buildings old town main bike route tram line bus line subway S-train mobility hub public transport high-frequency bike traffic > 5,000 bikes / day 500 m 100 m

500 m level of noise high low

sealed area

of pluvial flood high low

risk

favorable

infrastructure

CITY SCALE

understanding the ring road

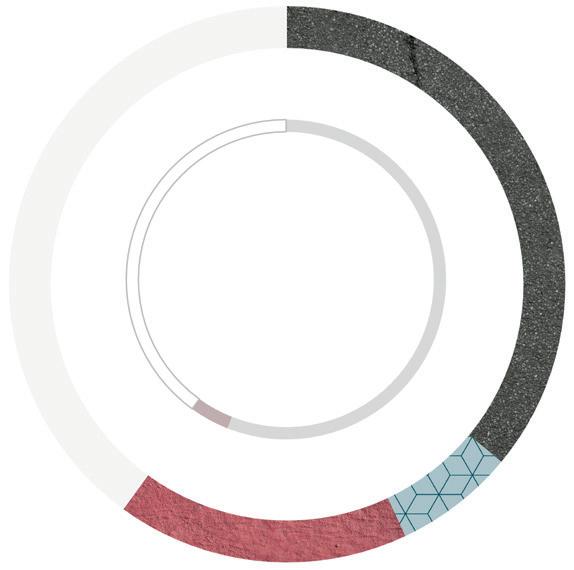

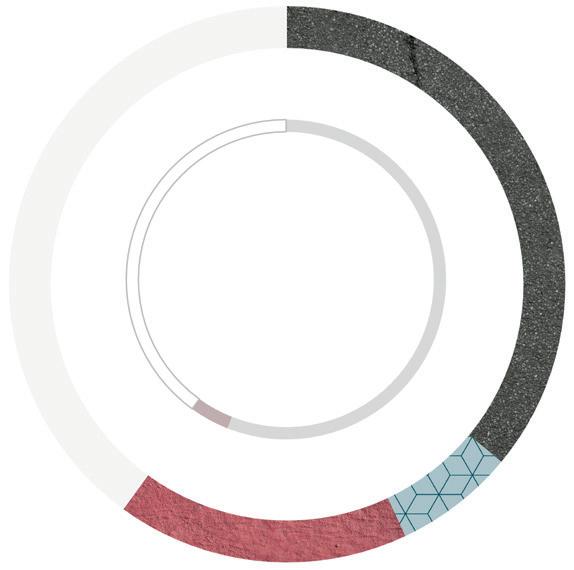

When trying to understand today’s ring road, valuable insights can be gained by looking at it in more detail. On the right page, an analysis of its current make-up and correlation between lanes can be found. The result is summarized in abstract diagrams shown below.

Up to nine traffic lanes accumulate next to each other between Stachus and Sendlinger Tor. Many street sections do not allow crossing and cut through the district. This is mostly because traffic directions are separated from each other by railings or concrete balustrades.

Pedestrians repeatedly have to walk several minutes to reach the next safe crossing possibility (such as a zebra or light-regulated crossing). When hurried, some people try to cross anyway, anywhere - thereby holding up traffic and putting themselves in danger.

According to the Accident Atlas, a source published annually by the

German Federal Statistical Office, over 200 accidents occurred along the ring road in 2019 to 2020 alone. This only includes accidents involving personal injury. Material damage accidents are not accounted for. The dataset is based on reports from police stations, thus unreported cases are overlooked in the statistic. What if we redesigned today’s parking spaces to increase safety, complete and optimize existing bike paths or enhance greenery?

Though many streets are tree-lined already today, connected green spaces only exist at Maximilianplatz in the northwest. Unfortunately, the park is of low quality, as it is surrounded by three-lane traffic from all sides. Noise and exhaust fumes pollute the site. What if we substituted motorized individual traffic and finally realized the Maximiliansplatz as a quiet and high-quality urban green space?

# of traffic lanes (both traffic directions accumulated)

# of secured crossings via streetlight or zebra crossing

# of accidents that caused personal injury in 2019 + 2020 (3 accidents / color)

# of parking lanes (both traffic directions accumulated)

# of cycling lanes (both traffic directions accumulated)

greenery (both traffic directions accumulated)

12 11

bicycle lanes pedestrian crossings traffic lanes parking lanes greenery accidents Analysis closer Altstadtring Große Variation verschiedenen Abschnitten

PRINCIPLE ANALYSIS

Zäh ung der ak ue en Spu en am A ts ad ng Bürgers e g Fahrbahn Parken pa ken+Grün Grüns re en Tram Fahr ad Baus e e 500 m 100 m AERIAL VIEW excerpt COUNT OF LANES abstracted V Zäh ung der aktue len Spuren am A tstadtring Bürgerste g Fahrbahn Parken parken+Grün Grünstre fen Tram Fahrrad Baustelle construction site bicycle lane tram lane greenery parking with greenery parking traffic lane pedestrian path

500 m 100 m

SITE SCALE

transformation in detail / zoom-in area blumenstraße

Where does one begin designing a transformation process when the total area is over 250,000 square meters large, comparable to the size of 35 football fields?

To address the issues stated, the decision was made to examine one zoom-in area along the ring road in particular: Blumenstraße and Prälat-Zistl-Straße (marked below).

The respective streetscapes pose special challenges, since they are rather narrow in comparison to other ring road segments. Furthermore, three particularly problematic situations are present:

1. The bike lane, coming from Sendlinger Tor gradually looses quality.

First, it is 2.8m wide and raised, then it becomes part of the road, gets thinner and thinner until it just arbitrarily ends in the middle of the zoom-in area. A car turning lane crosses the cycle path, creating a high-risk situation for cyclers.

2. The public square (dt.: Bunkerplatz) surrounding the architectural gallery, which recently relocated here and is creating a new cultural center, is surrounded by streets, rendering it very unpleasant and mostly unused.

3. 50 km/h traffic runs right beside Viktualienmarkt, creating a street canyon alongside one of Munich’s major tourist attractions. Pedestrians cannot see cars approaching behind the curve. Simultaneously, the site offers great potential. The surrounding urban fabric is rich and combines many functions. It is located right next to Schrannenhalle, Munich’s old grain trade hall that has been converted to a food and market hall today. The Jewish museum and Munich’s Stadtmuseum are located near-by, just like many other key buildings (as indicated on the next page). Overall, potential for a car-free transition design garners within the zoom-in area.

~1300

The city fortification ran along the axis where we know the Schrannenhalle to stand today. The street was located directly behind the wall and was connected to the „Taschenturm“, one of the city gates. Later, the city walls were torn down.

~1800

For many centuries, Munich‘s moat flowed through this area. With the opening of the city walls, the moat was closed and turned into green space The street was probably built in the 18th century. A name can be traced back to 1781 when it was first mentioned as „Scharfrichtergassl“. Since then, the street links old town and the Anger district.

Taschenturmgässchen, Anger Mauer

since 1984: Prälat Zistl Straße named after the city parish priest Prelate Max Zistl who was instrumental in initiating the reconstruction of old St. Peter‘s after its destruction due to WW II

„Schiffertor“

old city gate aquarell by Carl August Lebschée, 1724

Scharfrichtergassl

since 1874: Blumenstraße refers to the flower market which took place along the street next to Schrannenhalle back then

Schrannenhalle

14 13

construction history previous names today SITE PLAN zoom-in area

exterior view, sketch by Gustav Steinlein, 1920

Viktualienmarkt local farmers market, photograph, Stadtarchiv

Blumenstraße Street View photograph, Stadtarchiv

500 m 100 m buildings green space zoom-in area

context

zoom-in

Schrannenhalle seen from Petersturm photograph, Stadtarchiv, 1858

historical

/

area

/ “Maximilians-Getreide-Halle“ steel engraving, Bibliographisches Institut, Hildburghausen, 1855

SITE SCALE

aerial overview / key buildings

TheresaGerhardingerGymnasium

PRÄLAT-ZISTL-STRASSE

Jüdisches Museum Ohel-Jakob Synagoge Münchner Stadtmuseum

Architekturgallerie Bunkerplatz Elderly centre

Bürgerhaus Glockenbachwerkstatt

Schrannenhalle foodhall

Viktualienmarkt tourist attraction Bellevue di Monaco center for refugees

area length

No° lanes

ÖPNV

walking distance to next subway/train

No° trees

materiality

2,310 m2

0.22 km

#2 (à 3 m)

bus line No° 52, No° 62

4 min to Marienplatz station

7 min to Sendlinger Tor

#31

paved, trees on one side, cobble stone pedestrian path

area length

No° lanes

ÖPNV

walking distance to next subway/train

No° trees

materiality

BLUMENSTRASSE

4,570 m2

0.42 km

#2 - 4 (à 3.4 m)

bus line No° 132

4 min to Marienplatz station

1 min to Sendlinger Tor

#58

paved, partly tree-lined avenue

16 15

dESG c it lan os focus streets

1 1 2 3 4 5 2 5 3 4

SITE SCALE

deficits and potentials DETAILED

URBAN FABRIC potential No° 1

The existing urban fabric is of high quality. It offers a hint of how beautiful the site could become. Walkability is fantastic Various public squares are only a stone‘s throw away. Existing pedestrian zones could be easily reconnected by trafficcalming Prälat-Zistl-Straße. The area is in full use, pedestrians cross, tourists come by. When re-designing the streetscape there is great potential for the area to be transformed into a wonderful urban space

CLIMATE potential No° 2

There are very few green spaces. However, Blumenstraße is tree-lined with many beautiful old linden trees These should be preserved and can be integrated into future landscape concepts. Many old brooks flow underground, a microclimatic potential that can be resurfaced.

MOBILITY potential No°

Various public transport connections are provided, ensuring accessibility. The nearest station is always just a 2-min walk away. To minimize street space while maintaining public transport, it is proposed to slightly re-direct current bus lines as indicated below.

along Altstadtring re-direct effect: freed ring road two-directional one-directional effect: one lane less

THREE STREET TYPES analysis result

Based on the findings, three re-design street types arise: First, a flexible street that ensures continued access for public transport. Second, a bike focus street in line with the “2019 Bürgerradentscheid“. Third, the wide southern part of Blumenstraße offering new space for climate adaptation and urban life

bike focus climate / urban life shared street

18 17 Bus Bus

PLAN zoom-in area BIKE LANE ABRUPTLY ENDS deficit No° 1 LOW-QUALITY PUBLIC SQUARE deficit No° 2 STREET CANYON AND DANGEROUS

deficit No° 3 focus street 1min 2min 5min asis B S U B B B T T T T B B B B

SITE

CROSSING

GSEd c n V s o main walking route key building public square walkability

3

bus tram subway S B T U s-train

avenue green space old city stream

*if encircled = station / stop tree-lined

100 m 200 m

p r o posed

is

posed buildings 500 m 10 m

as

p r o

SITE SCALE

design proposal

STEP-BY-STEP

step No° 1

flexible street

Street space is minimized to a one-way shared space that ensures existing public transport connections can be maintained.

A two-way bicycle highway is implemented. Frequent, safe pedestrian crossings are planned.

Today, more than half of the zoom-in area’s streetscape is dedicated to individual motorized traffic. As indicated by the step-by-step design explanation (left page), the project proposes to transform the site’s DNA towards a space for modern micromobility modes, communities and social interaction, while at the same time contributing to establish a more climate resilient and lively city. As indicated in the diagrams above, asphalted street space is replaced by greenery and unsealed areas to allow slow infiltration of rainwater. Thereby the design reacts to the ring road’s high risk of pluvial flooding. Pedestrian zones are reconnected. The previously isolated square surrounding the architectural gallery is embedded in a high-quality urban context.

All existing trees are preserved. Level pedestrian crossings are ensured at least every 80 - 100 m, following a tried and tested recommendation by the Global Street Design Guide: “If it takes a person more than 3 min to walk to the next pedestrian crossing, the probability suddenly rises sharply that he or she may decide to cross along a more direct, but unsafe or unprotected route. (...) A pedestrian crossing should be as wide as the sidewalk it connects to and not be less than 3 m wide.”

The re-designed urban space can be experienced anew, by already 30,000 people who pass this area each day today in addition to local residents and working people within the area.

Along Blumenstraße an urban stream is resurfaced. Existing trees are preserved and enhanced. Remaining space can be regained by people.

urban stream

bike path

asphalted street

pedestrian zone

buildings and courtyards

space for people flexible space incl. public transport sidewalk

20 19 56 % 8 5 3 9 2m 24 % 6 ,479 m2 2%225 m2

PEOPLE / DAY = over 30.000 + residents + workforce current state enhanced micromobility climate and people

greenery

20,000 p/d Viktualienmarkt 8,000 p/d Schrannenhalle 200 p/d student housing kindergarden 120 p/d Glockenbachwerkstatt 1,000 p/d elementary and highschool 3 4 % 5 861, 2m 24 % 6 ,479 m2 17%2,529 m2 7%1067m 2 7%1, 06 7 2m %36 ,9 57 4 m2 13%1,893m2 17 % 2529m2

step No° 2 bicycle highway

THE

50 m 20 m 50 m 20 m

step No° 3 urban fabric

PULSE OF THE CITY

NEIGHBOURHOOD SCALE

transition zones

Having gotten a grasp of designing site-scale transformation, the question arises, what happens from here? How does an individual changed streetscape impact its surroundings and larger context?

In this project‘s case: How does a transformed Blumenstraße impact the adjacent Gärtnerplatz district? Below, an example of a possible transition scenario is visualized. It draws upon various tools, including dead-end street designs (D) realized in combination with a turning bay or resident-only regulation (neighbourhood street). Another possibility is is to extend the pedestrian realm until the next large traffic axis (B). Along Reichenbachstraße, the street connecting Viktualienmarkt and Gärtnerplatz, a car-free zone is in fact already being discussed, since a citizen petition with almost 1,000 signatures called for it in 2020 (dt.: „Petition Gärtnerplatz Fußgängerzone“).

These transition tools are not final, but are to be understood as options within a larger urban street re-design toolbox.

Similiar toolboxes can be created when addressing other questions, such as for example: How can it be ensured that cars are not simply replaced by fast-speeding bikes? There are various methods to tackle this issue, some of which are illustrated on the right. These include signage at pedestrian crossings (2), speed limits for electric bikes (6) and physical separation between zones (8). It has been shown by Jenny Eriksson (An analysis of cyclists‘ speed at combined pedestrian and cycle paths) that the thinner the cycle path, the slower the traffic. Thus, the design proposes to adapt bike path widths according to the needs of the immediate surrounding (7). When designing, it is not just relevant to consider different scales, but to also change perspectives - metaphorically and practically, horizontally (in site plans) and vertically (in sections). The following pages will thus take you through transformation design proposals in sections along the relevant zoom-in streets.

to ensure that individual, motorized traffic is not just replaced by speeding bikes TOOLBOX

to design the transition between trafficed and calmed neighbourhood zones

22 21

Pedestrian Priority 20 km/h Slow Down Speed Hump 1 2 3 change in colour pedestrian priority signage change of materiality (e.g. pebble stones) 4 change of elevation (e.g. speed hump) 5 night lighting 6 narrowing of road width 7 physical separation between priority zones (e.g. green stripe, posts) 8 speed limit for electric bikes D A B signage dead end street transition shared street transition pedestrian zone continued C turning bay dead end street

TOOLBOX 1

2

buildings and courtyards pedestrian zone asphalted street bike path urban stream flexible space incl. public transport sidewalk greenery

B A D 4 6 5 C 8 1 2 3 50 m 20 m

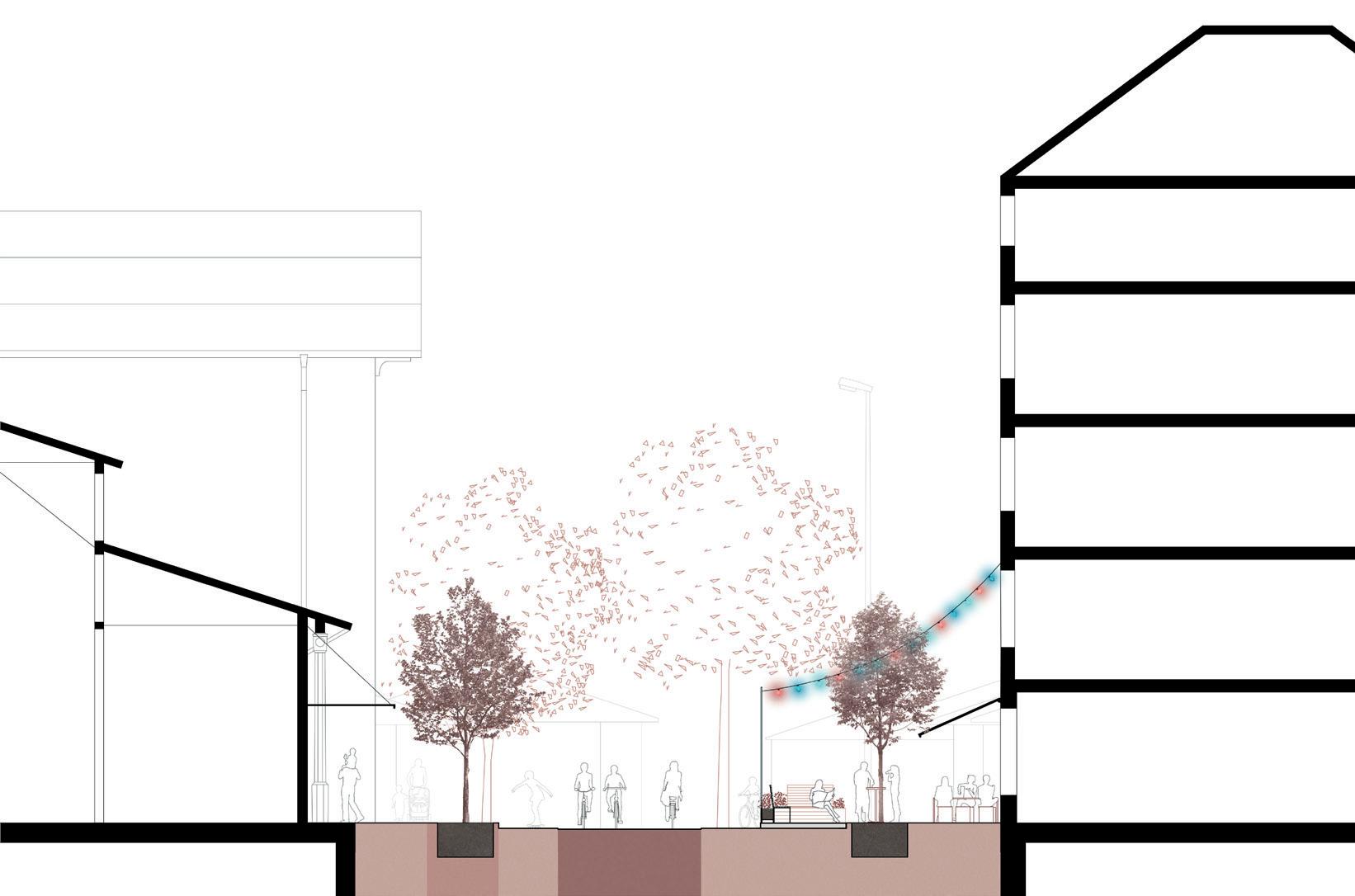

SITE SCALE

24 23

2 section No° 3

1

section No°

section No°

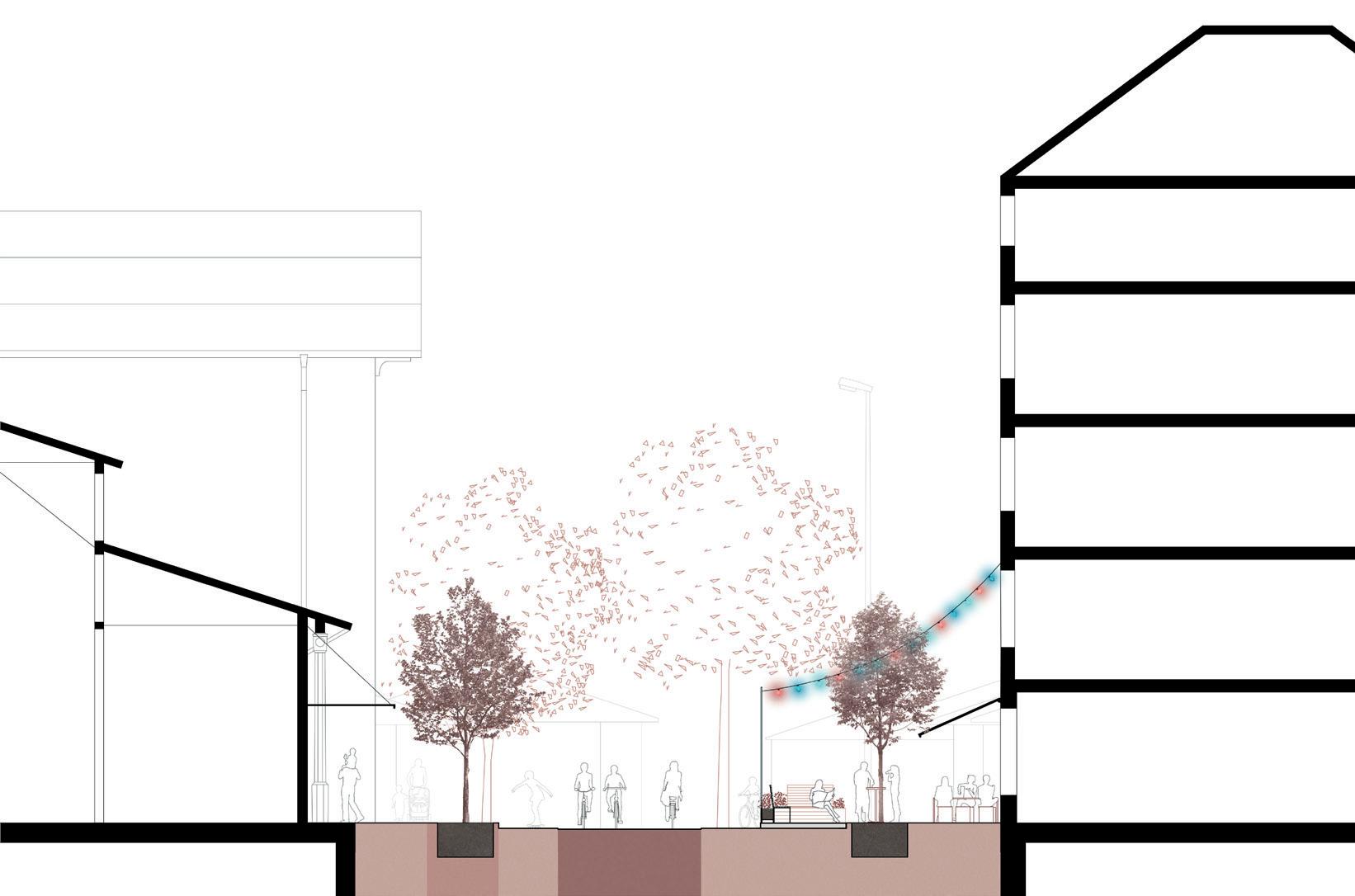

3.00 2.00 2.00 6.00 3.70 0.5 7.00 3.50 5.20 Restaurant Thai Eatery 1.5 pedestrian flexible bike pedestrian Schrannenhalle 20 SECTION No° 1

SECTION No° 1

state shared street

transformation in sections

design proposal

as-is

PRÄLAT-ZISTL-STRASSE

SHARED STREET section No° 1

20 m 50 m

BIKE HIGHWAY section No° 2 CLIMATE / URBAN LIFE section No° 3

26 25 climate / urban life BLUMENSTRASSE SOUTH bike highway BLUMENSTRASSE NORTH

No° 2

SECTION No° 3

SECTION No° 2

3.00 2.00 10.00 2.00 2.50 3.80 7.00 5.50 2.00 office use / retail Gymnasium 5.00 6.30 11.5 bike highway pedestrians pedestrians city stream 2.00 3.65 4.30 Schrannenhalle Restaurant Zum Goldenen Kalb 2.40 2.00 3.65 4.00 Schrannenhalle Restaurant Zum Goldenen Kalb 6.70 3.65 bike highway pedestrians pedestrians 1.65 1.65

SECTION

design proposal SECTION No° 3 design proposal

as-is state

as-is state

CITY SCALE design proposal

The sections visualize how a vibrant new eco-corridor could be realized along Blumenstraße. Areas for “Schrani” gardens, new pedestrian zoning along Viktualienmarkt, trails, greenery, art installations, space for chess players and table tennis are created. In the beginning, the project set out to re-think Munich’s inner ring road. From site to neighbourhood scale, the project now moves back to city scale.

In a car-free scenario, the current pedestrian zone (marked in gray below) will be enhanced respectively (see red extension). Car-free thereby implies the substitution of private, motorized traffic. In other words, essential infrastructure will of course be ensured further on (e.g. access for ambulances, logistics). As indicated in form of exemplary road signs below, there are various ways to design pedestrian zones to ensure all needs are met.

The inner ring is linked to various main traffic corridors (1). From here, parking houses are accessed (2). In a first re-design stage we propose to maintain these in place and allow a smooth transition before substituting them completely later on. For this, the design proposes restricted driving access that crosses the inner ring road (6). Access could be regulated by locating the parking entrance gate already at the edge of the ring.

A car-free inner ring road implies minimizing current traffic corridors. However, from North to South, the existing connection cannot be substituted entirely since the neighbouring streets would be flooded quickly. The design thus proposes keeping a two-lane street in place (see 5) with a 20km/h speed limit.

Bike infrastructure (3) shall be upgraded, designed as safe and continuous paths (7). The public transport network will be kept (4) with flexible street concepts where necessary, a new ring line (8) and bike sharing stations.

28 27 extension

e Anwohner e TAXI e L e erve keh re Mo - F 6 - 10 h 13 - 15 h 6 - 10 h Sa existing pedestrian zone parking house RESTRICTED ACCESS PARKING design proposal MAIN TRAFFIC CORRIDORS as-is state COUNT OF PARKING SPACES as-is state CONTINUED CONNECTION N/S design proposal continued slow traffic 20 km/h connection N / S traffic-calmed zone size of parking house CYCLING INFRASTRUCTURE as-is state existing bike path two-way accidents that caused personal injury in 2019 + 2020 (car / bike accident) CYCLING RING design proposal new bike highway ring route PUBLIC TRANSPORT NETWORK as-is state tram route bus route station / stop bike sharing spot PUBLIC TRANSPORT NETWORK design proposal new ring ÖPNV 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 PUBLIC TRANSPORT NETWORK AS-IS state buildings green space buildings old town tram route bus route station stop bike sharing spot traffic-calmed zone 73 Amann Hergerdt PUBLIC TRANSPORT RING LINE design proposal buildings green space buildings old town tram route bus route new ring ÖPNV station stop bike sharing spot traffic-calmed zone 74 Amann Hergerdt 500 m 500 m 100 m

CLIMATE as-is state

CLIMATE ADAPTATION design proposal

Wimmelbild take a flight

water

traffic-calmed zone

buildings old town

green space buildings

Existing greenery (9) is enhanced by resurfacing various urban streams and integrating rainwater retention to minimize risk of pluvial flooding. Green spaces are enlarged and connected to each other (10). The result is summarized in the masterplan that can be seen below as well as in abstract principle diagrams (right page). They display what could be achieved, that could be achieved if all proposed design elements are put into practice. Private, motorized traffic as well as parking space is reduced to a minimum,

enhanced / linked green space

urban stream resurfaced

only obtaining the smallest necessary volume. Risk of accidents involving personal injury is alleviated. Bike infrastructure is upgraded, paths are raised, broadened and continuous without sudden stops. Frequent and safe pedestrian crossings are ensured everywhere. The remaining space is regained by people and dedicated to climate adaptation, greenery, urban streams, social activities, leisure and much more. Diverse, resilient urban spaces of high-quality are created for everyone.

MASTERPLAN design summary

traffic lanes

For a visualization of the masterplan proposal and its manifold possibilities and opportunities, a video has been created that takes you on a flight over the transformed inner ring road. To access, use this link or scan the QR code below.

DESIGN RESULT

principle diagrams

new ring ÖPNV

bus route

tram route

continued slow traffic 20 km/h connection N /S

station stop bike ring route restricted driving to access parking house e.g. regulation via gate located at ring entrance

urban stream resurfaced

green space

water

traffic-calmed zone

buildings

urban streams

pedestrian crossings greenery

bicycle lanes

accidents & parking

# of traffic lanes

# of secured crossings via streetlight or zebra crossing

# of accidents that caused personal injury in 2019 + 2020 (3 accidents / color)

# of parking lanes (both traffic directions accumulated)

water resurfaced

# of cycling lanes greenery (both traffic directions accumulated)

30 29

500 m 100 m

9 10

ADAPTABLE SCALE

CREATING A DOMINO EFFECT

The tools applied throughout the different design stages so far can be summarized in form of a toolbox, considering mobility, climate and urban fabric.

This is to show that the project is not a onedesign. Though it does consider local needs and circumstances, the project overall really aims to work across scales and function as a system design.

32 31

toolbox

street

generic

for

re-design

... ... ... (LOCAL)COMMUNITY TEMPORARY INTERVENTIONS FLORA/FAUNA WATER/ COOLING RENEWABLE ENERGY URBAN CANOPIES SHARED SPACE

PEDESTRIAN ZONES

BIKEINFRASTRUCTURE PUBLICTRANSPORT EDUCATION CULTURE SPORT flexible street flea market local farmers art pavilions & installations urban gardening demonstrations & citizen engagement climbing wall table tennis basketball food trucks seating & hammocks social interaction new meeting points playgrounds and family fun shading trees urban canopies solarized walk- & bikeways pavegan sidewalks urban streams & squares cooling & drinking fountains rain retention, wet ponds trails, parks, natural infiltration wetlands, forest, drought-resistant species 20 20 km/h speed limit enhanced pedestrian zones bike transport in bus & tram public transport = free of charge bike station & repair bike sharing local & regional bikeways continuous journeys safe pedestrian crossings “el-e-ment” noun A distinct feature within a larger composition.

PEDESTRIAN CROSSINGS

urban fabric tools climate tools mobility tools

CONCLUSION

re-imagine the status quo

How many cars can we move down the street? (20th century) How many people can we move down the street? (21st century)

Asking the right question is the first step to finding the right solutions.The future of society lies in cities. Today already 56 % of the worldwide population lives in cities. This number is estimated to rise to 75 % in the future. Interestingly in the past, cities have always benefited from crisis - which is why we believe they will again. The great fire of London for example created fireproof construction methods and building codes. Modern sanitation in Munich was created as a reaction to the Cholera epidemic. Unfortunately, in the last decades, we have embarked on a selfdestructing path. 10 million people die of pollution every year. It is the biggest cause of children being hospitalized, because of environmentally induced Asthma. In the 21st century, urban society is faced with many challenges, among them one of the greatest: tackling global warming. Today’s challenges bring back the need for balancing local and global. To find solutions we need to run experiments, have the courage to lead and explore, find holistic design approaches that break down the silos of a city. We need to think across scales and classes and begin designing cities that are resilient, healthy, lively and

enjoyable for everyone - today and in the future. When re-designed, our public urban streetscapes have great potential to contribute to this endeavor.

To tackle the challenges ahead, we are all responsible. Only together can we create the future we and the ones who come after us want to live in. Every individual can contribute, but the bigger the movement, the larger its impact.

Our systems are self-made and thus, can be changed. The power of legislation is important when it comes to balancing out the city. However, processes are lengthy. We no onger have the time to “wait and see”. Today’s crisis, climate change, calls for immediate action. The barrier we are facing as a society is that politics shirks its responsibility.

This project is meant to stimulate discourse. It s meant to be both realistic and a heterotopia. It is meant to convey concepts and spark discussion.

It is a call to politicians to finally take the hands that are being extended to them from all sides. And to do so immediately. Today. The solutions are here.

TOOLBOX PUZZLE

Urban life and infrastructures around the world are impacted by rising temperatures. Concurrently, cities are a key contributor to climate change. Only with a coordinated approach and action at global, regional, national and local levels, can cities transform - from being a major contributor of, to becoming an integral part of the solution in fighting climate change. Some of the tools to do so have been contrived in this project and are summarized in the toolbox puzzle to the left. Of course, these are only an excerpt within a much larger set of possible tools and solutions. Everyone has the means to add to them or fit a missing piece.

34 33

sources

Designing Across Scales / 01-02

Chair for Building Technology and Climate Responsive Design (2021): STREETLESS. Designing for Post-Car Cities. Technical University Munich.

Immerwahr, Daniel (2021): We all move. In: The Nation. https://www.thenation.com/ article/world/sonia-shah-great-migration/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

LaMothe Kimerer (2016): Are Humans “Born to Move?” In: Psychology Today. https:// www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/what-body-knows/201611/are-humans-born-move, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Levitin, Daniel (2020): Exercise and the brain: why moving your body matters. In: Science Focus, https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/exercise-and-thebrain-why-moving-your-body-matters/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Worrall, Simon (2016): Why You Move the Way You Do. In: National Geographic. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/160228-motion-movementlocomotion-evolution-science-wilkinson-ngbooktalk, accessed: 22.02.2022.

History of the Street / 03-06

Archiv für Autobahn- und Straßengeschichte (2014): http://www.strassengeschichte.de/ afasgindex.htm, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Bayrisches Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst: Haus der Bayrischen Geschichte. Die Ruine München nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg. https://www.bavariathek. bayern/wiederaufbau/orte/detail/muenchen/2, accessed: 22.02.2022

Bayrische Vermessungsverwaltung (2022): BayernAtlas. Bayrisches Staatsministerium der Finanzen und für Heimat. https://geoportal.bayern.de/ bayernatlas/?lang=de&topic=ba&bgLayer=atkis&catalogNodes=11, accessed: 22.02.2022

Barfield, Rosa (2020): Who Invented the Wheel? A Brief History. https://blog.bricsys. com/who-invented-the-wheel-a-brief-history/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Cambridge Dictionary: Street. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/de/worterbuch/englisch/ street, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Franz Schiermeier Verlag München (2003): Stadtatlas München. Karten und Modelle von 1570 bis heute. https://www.stadtatlas-muenchen.de/Münchner_Stadtkarten, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Gehl, Jan (2010): Cities for People. Washington DC: Island Press. Grimm, Roland (2014): BaustoffWissen. Die Geschichte des Straßenbaus. https:// www.baustoffwissen.de/baustoffe/baustoffknowhow/garten-landschaftsbau-tiefbau/ strassenbau-geschichte-trampelpfad-asphaltdecke/, accessed: 22.02.2022

Groß, Gerhard (2004): München wie geplant: die Entwicklung der Stadt von 1158 bis 2008. 1. Edition, München: Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung der Landeshauptstadt München.

Jacobs, Jane (1961): Death and Life of Great American Cities. 1. Edition, New York: Random House.

Kappel, Marc (2020): Angewandter Straßenbau. Straßenfertiger im Einsatz. 3. Auflage, Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

Lampugnani, Vittorio Magnago (2019): Bedeutsame Belanglosigkeiten. Kleine Dinge im Stadtraum. Berlin: Wagenbach Klaus GmbH.

Münchner Stadtmuseum (1806): Brücke über den Entenbach in der Au. Johann Georg von Dilis.

Online Etymology Dictionary: street. https://www.etymonline.com/word/street, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Rädlinger, Christine (2004): Geschichte der Münchner Stadtbäche. 3. Edition.

München: Stadtarchiv

Rädlinger, Christine (2008): Geschichte der Münchner Brücken. Brücken bauen von der Stadtgründung bis heute. 1. Edition, München: Baureferat der Landeshauptstadt München.

Silver, Christopher (2000): New Urbanism and Planning History: Back to the Future. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Stadtarchiv München: Online-Archivkatalog des Stadtarchivs. https://stadt.muenchen. de/infos/recherche-stadtarchiv.html, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Stadtgeschichte München: Geschichte der Straßenbenennungen. https:// stadtgeschichte-muenchen.de/strassen/geschichte/geschichte.php, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Virginia Asphalt Association: The History of Asphalt. https://vaasphalt.org/the-history-ofasphalt/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Warta, Christina (2021): München unterwegs. Das neue Mobilitätsreferat der Stadt München. Aufbau, Herausforderungen, Projekte. Pressekonferenz 12. März 2021, München.

Winterstein, Axel (2017): München und das Auto. Verkehrsplanung im Zeichen der Moderne. Kleine Münchner Geschichten, 1. Edition, Regensburg: Verlag Friedrich Pustet.

The Potential Of The Street / 07-08

Google Maps (2022): Altstadtring München. https://www.google.com/maps/@48.12315

27,11.5745003,2160a,35y,38.79t/data=!3m1!1e3, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung (2019): Bürgerbegehren „Altstadt-Radlring“. https://www.muenchen-transparent.de/dokumente/5812684, accessed: 22.02.2022.

City Scale - analysis mobility and climate / 09-10

Bayrische Vermessungsverwaltung (2022): Lärmbelastungskataster UmweltAtlas Bayern. https://www.umweltatlas.bayern.de/mapapps/resources/apps/lfu_laerm_ftz/ index.html?lang=de, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Copernicus Urban Atlas (2018): The European Earth Observation Programme. Imperviousness Density. Versiegelungsgrad München (Stadt).

GDV Die Deutschen Versicherer (2021): Starkregengefährdungskarte München. https:// www.gdv.de/de/themen/schwerpunkte/naturgefahren, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Intraplan (2020): Verbesserung der Verkehrsdatensituation für den Radverkehr in München. https://www.intraplan.de/projectpapers/verbesserung-derverkehrsdatensituation-fuer-den-radverkehr-in-muenchen-2/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Landeshauptstadt München, Referat für Gesundheit und Umwelt (2014): Stadtklimaanalyse. Klima- und immissionsökologische Funktionen für das Stadtgebiet. https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/stadtklima-klimaanpassung.html, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Mobilitätsreferat Landeshauptstadt München (2019): Radverkehrsmengenkarte.

Radfahrten pro Normalwerktag (Di-Do). Münchner Verkehrsverbund MVV (2022): MVV-Pläne zum Download. Verkehrslinienplan Fahrplanjahr 2022.

City Scale - understanding the ring road / 11-12

Google Maps (2022): Altstadtring München. https://www.google.com/maps/@48.12315

27,11.5745003,2160a,35y,38.79t/data=!3m1!1e3, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Statistische Ämter des Bundes (2020): Unfallatlas. https://unfallatlas.statistikportal.de, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Site Scale - transformation in detail / 13-14

Bibliographisches Institut Hildburghausen (1855): Neue Schrannenhalle in München.

Saarbrücken: Antiquariat Martin Barbian & Grund GbR. Kick, Günther (2019): München – die befestigte Stadt. Zwei Rundgänge zu den ehemaligen Wehranlagen. München: Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung. München Wiki: Blumenstraße. https://www.muenchenwiki.de/wiki/Blumenstraße, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Stadtarchiv München: Online-Archivkatalog des Stadtarchivs. https://stadt.muenchen. de/infos/recherche-stadtarchiv.html, accessed: 22.02.2022. Stadtgeschichte München: Geschichte der Straßenbenennungen. https:// stadtgeschichte-muenchen.de/strassen/geschichte/geschichte.php, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Steinlein, Gustav (1920): Die Baukunst Alt-Münchens. Eine städtebauliche Studie über die Münchner Bauweise von der Gründung der Stadt bis Ende des 16. Jahrhunderts.

München: Bayrischer Landesverein für Heimatschutz.

Zentrales Verzeichnis Antiquarischer Bücher ZVAB: Schrannenhalle mit zahlreichen Pferdefuhrwerken. Eurasburg: Peter Bierl Buch- & Kunstantiquariat.

Site Scale - aerial overview and key buildings / 15-16

Google Maps (2022): Blumenstraße München. https://www.google.com/maps/place/ Blumenstra e,+München, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Site Scale - deficits and potentials / 17-18

Berktold, Ruth, Yes Architecture (2017): Machbarkeitsstudie Hochbunker Blumenstra e. Landeshauptstadt München Baureferat.

Münchner Verkehrsverbund MVV (2022): MVV-Pläne zum Download. Verkehrslinienplan Fahrplanjahr 2022.

Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung (2007): Innenstadtkonzept. Leitlinien für die Münchner Innenstadt und Maßnahmenkonzept zur Aufwertung. Landeshauptstadt München.

Site Scale - design proposal 19-20

Curi, Yael (2019): 40 Jahre Glockenbachwerkstatt – Kultur von allen für alle. Curt. Unser München im Blog. https://www.curt.de/muenchen/40-jahre-glockenbachwerkstatt/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Food Service (2012): Schrannenhalle, München. Positive Bilanz nach drei Monaten. https://www.food-service.de/maerkte/news/-Positive-Bilanz-nach-drei-Monaten-24675, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Guyton, Patrick (2018): Der Viktualienmarkt – eine Münchner Herzensangelegenheit: In: Der Tagesspiegel. 22.04.2018.

muenchen.de: Isarvorstadt: Alle Infos zum Münchner Stadtteil. https://www.muenchen. de/stadtteile/isarvorstadt.html, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Statistisches Amt München: Bevölkerungsdichte Gärtnerplatzviertel. https:// www.citypopulation.de/en/germany/munchen/admin/ludwigsvorstadt_isarvor/ M021__g rtnerplatz/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Theresie-Gerhardinger-Gymnasium am Anger (2022): Interview durch Verfasser. München, 26.01.2022. Phone call with secretary.

Neighbourhood Scale – transition zones 21-22

Eriksson, Jenny et al. (2019): An analysis of cyclists’ speed at combined pedestrian and cycle paths. Traffic Injury Prevention.

Global Designing Cities Initiative (2016): Global Street Design Guide. Pedestrian Crossings. 1. Edition, New York: Island Press.

openPetition (2020): Gärtnerplatz Fußgängerzone München. Stadtbezirk 01 AltstadtLehel. https://www.openpetition.de/petition/online/gaertnerplatz-fussgaengerzone, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Urban Street Design Guide (2013): Pervious Pavement. National Association of City Transportation Officials. 1. Edition, New York: Island Press.

City Scale - design proposal 27-30 meinestadt.de: Parkplätze und Parkhäuser in München. https://www.meinestadt.de/ muenchen/stadtplan/point-of-interest/parkhaeuser, accessed: 22.02.2022. Münchner Verkehrsverbund MVV (2022): MVV-Pläne zum Download. Verkehrslinienplan Fahrplanjahr 2022.

Parkopedia: Innenstadt München. https://www.parkopedia.de/parken/innenstadt_ münchen/?arriving=202202242330&leaving=202202250130, accessed: 22.02.2022. Stadtbranchenbuch München: Parkhäuser München und Umgebung. https://www. muenchen.de/service/branchenbuch/P/2764.html, accessed: 22.02.2022. Statistische Ämter des Bundes (2020): Unfallatlas. https://unfallatlas.statistikportal.de, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Adaptable Scale 31-32

Climate Resilient City Toolbox: https://kbstoolbox.nl/en/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Energie Zukunft: Erster Solar-Radweg Deutschlands eröffnet. https://www. energiezukunft.eu/erneuerbare-energien/solar/erster-solar-radweg-deutschlandseroeffnet/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Pavegen: https://pavegen.com, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Conclusions / 34

Climatelier (2018): REALCOOL – Really cooling water bodies in cities. http://climatelier. net/projects/research/realcool-really-cooling-water-bodies-in-cities/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Foster, Norman (2021): COP26 Climate Breakfast with Mayors: a dialogue with Norman Foster and John Kerry. UNCE. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aRGonrbe8rQ, accessed: 03.11.2021.

GDV Die Deutschen Versicherer (2021): Starkregengefährdungskarte München. https:// www.gdv.de/de/themen/schwerpunkte/naturgefahren, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Landeshauptstadt München, Referat für Gesundheit und Umwelt (2014): Stadtklimaanalyse. Klima- und immissionsökologische Funktionen für das Stadtgebiet. https://stadt.muenchen.de/infos/stadtklima-klimaanpassung.html, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Monheim, H. (2011): Evaluationsbericht der Fahrradmarketingkampagne „Radlhauptstadt München“.

muenchen.de: Statistische Daten zum Thema Verkehr in München. https://stadt. muenchen.de/infos/statistik-verkehr.html, accessed: 22.02.2022. München CoolCity: Fahrradkultur in München: Mitmachen lohnt sich – gemeinsam für ein gutes Klima. https://coolcity.de/jetzt-starten/mobilitaet/mobilitaet-fahrradkultur-inmuenchen/, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Statistische Ämter des Bundes (2020): Unfallatlas. https://unfallatlas.statistikportal.de, accessed: 22.02.2022.

The Guardian (2022): Copenhagenize your city: the case for urban cycling in 12 graphs.

36 35

UN Environment Programme: Cities and climate change. https://www.unep.org/ explore-topics/resource-efficiency/what-we-do/cities/cities-and-climate-change, accessed: 22.02.2022.

United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development. https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Additional Sources

ArkDes Think Tank (2021): Street Moves Manual.

Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt (2022): Vorläufige Jahreskurzauswertung 2021 für Stickstoffdioxid und Feinstaub. Lufthygienisches Landesüberwachungssystem Bayern (LÜB).

Bayrisches Staatsministerium für Wohnen, Bau und Verkehr (2019): Empfehlungen zu Planung und Bau von Radschnellwegen in Bayern. Arbeitspapier.

Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung im Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (2016): Standortsteckbrief Blumenstraße, München. Gefährdungseinstufung Naturgefahren.

European Commission: Climate-Neutral and Smart Cities. https://ec.europa.eu/info/ research-and-innovation/funding/funding-opportunities/funding-programmes-andopen-calls/horizon-europe/eu-missions-horizon-europe/climate-neutral-and-smartcities_en, accessed: 22.02.2022.

European Mission (2020): 100 Climate-neutral Cities by 2030 – by and for the Citizens. Report of the Mission Board for climate-neutral and smart cities. Independent Expert Report.

GreenCity. Der Verein: https://www.greencity.de/verein/, accessed: 22.02.2022. Hutter, Dominik (2019): Wie die Münchner Innenstadt autofrei werden soll. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/muenchen/autofreie-innenstadtmuenchen-1.4446274, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Mobilitätsreferat München (2021): Ergänzung zum Mobilitätsausschuss 22.09.2021. Radschnellweg Münchner Norden. https://www.muenchen-transparent.de/ dokumente/6799641, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Polizeipräsidium München (2021): Jährliche Verkehrsberichte des Polizeipräsidium München. Unfallbilanz. https://www.polizei.bayern.de/verkehr/statistik/005147/index. html, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung München, Beschlussentwurf (2020): “Autofreie Altstadt” Parkraumkonzept Innenstadt. https://www.muenchen-transparent. de/dokumente/6303326, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Referat für Stadtplanung und Bauordnung (2022): STEP 2040. MitDenken. Gemeinsam die Stadt verändern. https://www.muenchen-mitdenken.de/node/7369, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Schneider, Michael (2016): Konzept zur Anpassung an die Folgen des Klimawandels in der Landeshauptstadt München. München: Landeshauptstadt München, Referat für Gesundheit und Umwelt.

Sidewalk Labs: Pebble. A low-cost vehicle sensor to help manage parking and curb space. https://www.sidewalklabs.com/products/pebble, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Sidorova, Milota et al. (2016): How to Design a Fair Shared City? 8 short stories based on equitable urban planning in everyday life. Prag: Heinrich-B ll-Stiftung e.V. The City of Columbia Planning Department (2009): The Boulevard 2050 & Tomorrow. Town Planning and Urban Design Collaborative.

Street Lab: Programs for Public Spaces. https://www.streetlab.org, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Tom & Hilde (2020): 4-Fahrspuren und keine Busse. https://tomundhilde.de/aktuelles/

artikel/4-fahrspuren-und-keine-busse, accessed: 22.02.2022.

Immobilien Report München (2021): Altstadt: Hofbräuhaus Parkgarage Erövffnet. https://www.immobilienreport.de/gewerbe/Thomas-Wimmer-Ring-Tiefgarage.php, accessed: 22.02.2022.

van Hattum, Tim (2022): Climate resilient cities. Nature based solutions for future-proof cities. Wageningen University and Research.

Principle note: All site plans are oriented North. The words “street” and “road” are used synonymously throughout the project.

Special Thank you

Katrin Schultze-Naumburg, “Die Stadtflaneurin” / Historian for your expertise regarding Munich’s history and a wonderful phone conversation Hermann Grub und Petra Lejeune / Architects for your time, support and ideas

Ulyana Vynyarchuk and Judith O’Meara / EIT Urban Mobility for sharing your insights on European urban (micro)mobility trends Nicola Borgmann Head Architectural Gallery for providing us with inspiration in the very early-design stage

Our Families, Loved Ones and Friends for everything

The entire Chair: Bilge Kobas, David Selje, Sandra Persiani, Juan Romero Amaya and Professor Thomas Auer / TU Munich

37