Healthcare

Pharma

Life Sciences

Veterinary

Social Care

4

Healthcare

Pharma

Life Sciences

Veterinary

Social Care

4

8

Location, location, location...

The supply-side market forces that drive location selection and the patterns created in the retail pharmacy, veterinary and private medicine sectors

Adam Scott and Ty Lantz

Private equity healthcare IT deals slowed in 2023, but add-ons have continued to grow

Adam Scott and Johan Ottosson

Examining opportunities for pharmaceuticals in women’s health

Penny Sherlock and Adam Scott

14

19

24

30

32

38

44

Quality matters - a closer inspection of the CQC

The CQC has moved to a system of more targeted inspections ‒ what are the implications for investors?

Abhishek Patel

Managed markets

Comparing the German and UK private hospital sectors

Arne Berndt and Paul Fegan

Deals in the surgical ophthalmic equipment and products market reached a record high in 2022, with PE backed transactions also attaining new highs

Johan Ottosson and Dr Victor Chua

Prospects for private investment in Spanish and British hospitals

Spanish and British health services are remarkably similar, but where the countries differ is the scale and scope of private hospitals

Paul Fegan and Henry Elphick

Increasing diagnostics capacity is key to driving down waiting times in the NHS. But despite claims of success, imaging remains surprisingly constrained

Tom Atherton and Adam Scott

NHS waiting lists - behind the headlines

Waiting lists are likely to be a key factor in the next General Election and there is renewed government focus on reducing them

Adam Scott and Ali Bahram

Is there wisdom in investing in European Dentistry?

Examining the state of dentistry across the UK and larger European countries and delving into some of the big trends affecting dentistry everywhere

Ty Lantz and Stephanie Yeung

Where are the trends in the non-therapeutic antibodies market and how can investors create value?

Victor Chua and Will Johnson

No chicken feed

The global animal feed market is growing faster than the population at 4%. We consider the growing importance of this market

Arabella Zuckerman and Adam Scott

In 1987, VCA Animal Hospitals acquired its first independently owned companion animal clinic, sparking the beginning of a consolidation process

Freddie Evans and Adam Scott

Where next for independent fostering agencies and yhy there is room for optimism

Paul Fegan and Henry Elphick

We need to attract more people into social care and, importantly, retain them. What can be done to possibly transform the profession?

Paul Fegan and Ty Lantz

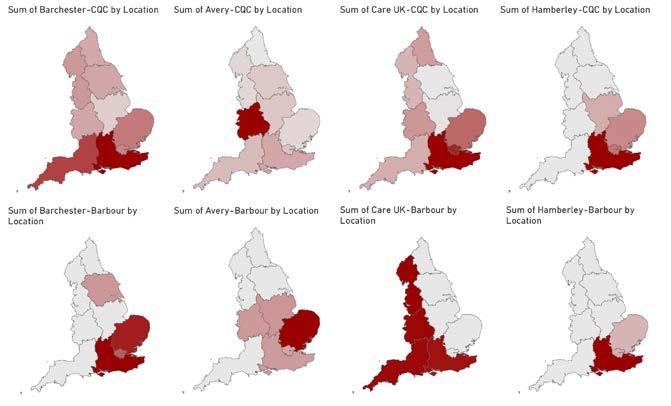

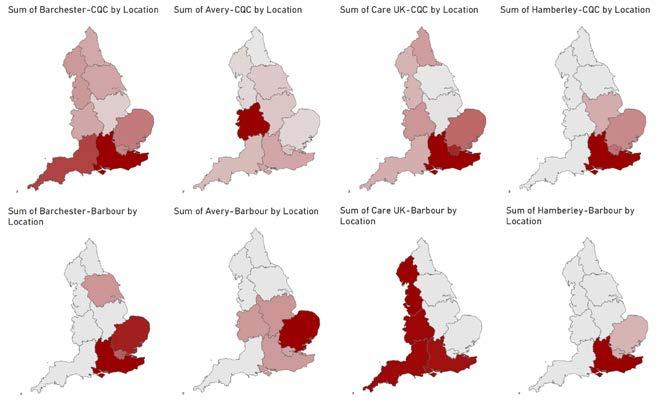

When it comes to care home construction in England, who is building what, where and for whom?

Johan Ottosson and Henry Elphick

48

52

58

64

69

75

79

Every sector in health and care has its own nuances. However, in all of them, location is critical all the way down from the broad national level to individual site selection. Regarding site selection, when speaking to a real estate advisor, one might hear ‘many things matter and the first three are location, location, and location’. But, at Mansfield, we are strategy advisors so what does it mean to be strategic about site selection for healthcare businesses?

The topic comes up in several contexts:

• Market entry which are the best markets to enter, and where within a market should one operate?

• Portfolio analysis how can we optimally meet the needs of our customers? How are individual sites performing relative to the suitability of their locations? Which sites should be combined or split?

• Mergers and acquisitions how do two companies fit together? Are the locations complementary or is there risk of cannibalisation? Should the merged portfolio be rationalised?

• Roll-up runway what are the limiting factors of consolidation? How much further can the industry or any individual company go?

In healthcare services, location selection typically hinges on four dimensions: supply, demand, funding, and access to staff. The importance and scope of each varies by sub-sector, and many industry veterans will have an intuition for finding good locations, but often the interaction of variables is complex.

For example, care home operators targeting the private-pay market might locate in affluent areas with an aging population, but staff costs can be 60% or more of revenue and many workers rely on public transportation. Care homes with few nearby transit links can go understaffed, become reliant on locum workers, and fall out of profitability quickly.

We recently encountered a care home positioned a 10-minute walk up a steep hill from the nearest bus station. This walk was so troublesome that the operator had tried hiring a private driver and aligning shifts with the bus schedule, and they eventually bought a van to shuttle employees to and from the station. The lesson is,

in care homes, access to staff is so key to profitability that well-connected homes near the boundaries between affluent and less-affluent areas often perform best.

One can develop heuristics like this via long years in industry, by speaking with experts, or via examining large portfolios to discover what works. However, even the savvy industry vet can learn something from intense data interrogation, and the application of geographical and social sciences, and advances in computing allow us to explain and discover location phenomena that drive access to care and sustainable growth.

Imagine a sunny Spanish beach in Menorca or Ibiza (you decide). The beach is butted on both ends by cliffs, and a boardwalk runs parallel to the sea. Two entrepreneurs, who are competitors, decide to sell sunscreen from rolling carts to the beachgoers who are distributed evenly along the beach. The competitors are the only sellers on the beach. Where do they choose to put their carts?

In the simplest case, if they both position themselves equidistant from the

ends, anywhere along the beach, they share the market evenly. Regardless of the initial configuration, eventually one of the sellers will realise that moving either toward the other or the centre will gain him or her incremental market share. The other seller will react in turn by moving similarly, and so it goes until the carts are next to one another at the midpoint.

Once there, the sellers reach a state of a Nash equilibrium, named after the mathematician John Nash, in which a unilateral move away from the midpoint would cost the mover market share. This scenario is described by Hotelling’s law and is one of the reasons you might see competitors like Starbucks and Pret a Manger sharing street corners.

Now imagine the beach is very long and the tourists prefer not to walk long distances for sunscreen. If the sellers recognise that the tourists bear search costs, a different configuration will arise.

The carts will distance themselves, and each seller will be able to charge a premium up to the cost a tourist bears by walking all the way to the other cart. If the sellers get particularly wise, they may also realise that they can further change the ‘distance’ to the next cart by offering differentiated products. In this case, a buyer’s preference for a product may offset some of the burden of a far walk and win the seller with preferred products additional share. This phenomenon was first discussed by economists Edward Hastings Chamberlin and Joan Robinson and is known as monopolistic competition because the sellers remain in competition despite having small local monopolies.

One may experience this market force when comparing prices between corner stores and supermarkets. In most cases, a shopper chooses the corner store for convenience so shop owners charge inflated prices for late-night snacks.

Let’s add yet another kernel of reality to the situation: imagine the sellers bear greater transportation and delivery costs the further they distance themselves from the beach access point. With this constraint, the sellers would place themselves at the points that balance the benefits and costs of distance. If the costs are significant, the sellers may end up next to each other once more. The sellers may even benefit from overall lower delivery costs because the other is nearby. In the field of urban economics, this network effect is called the agglomeration effect,

which posits that businesses can profit from returns to scale not only as a single competitor grows but also as an industry within a region scales – perhaps without any single competitor growing.

In the classical theory, the benefits come from transportation costs, labour availability, and knowledge distribution. As a knock-on effect of agglomeration, some regions become famous for particular goods or services and companies can benefit from the signalling they are there. Examples include old-world tailors on Savile Row in London and new-world tech companies in Silicon Valley.

IN MOST CASES, A SHOPPER CHOOSES THE CORNER STORE FOR CONVENIENCE SO SHOP OWNERS CHARGE INFLATED PRICES FOR LATE-NIGHT SNACKS

Thinking more broadly about network effects in location strategy, one may also consider the presence of participants in other industries. For instance, restaurants, coffee shops, and clothing retailers thrive in areas with high foot traffic and are often seen together because they benefit from the presence of customers drawn by the other types of stores.

So how does this work in real-life healthcare sectors?

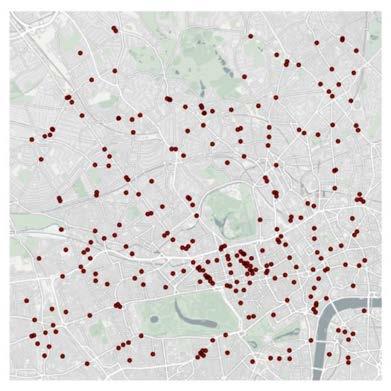

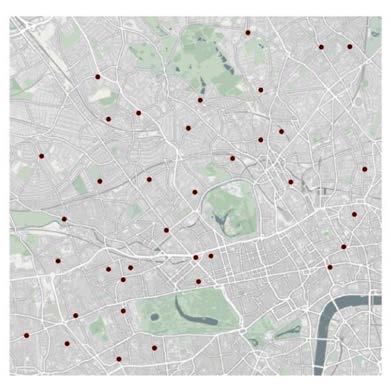

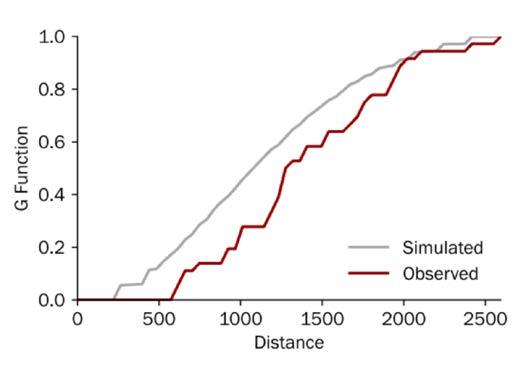

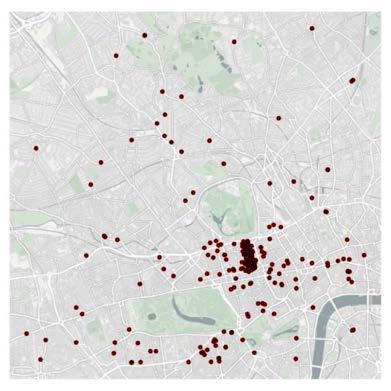

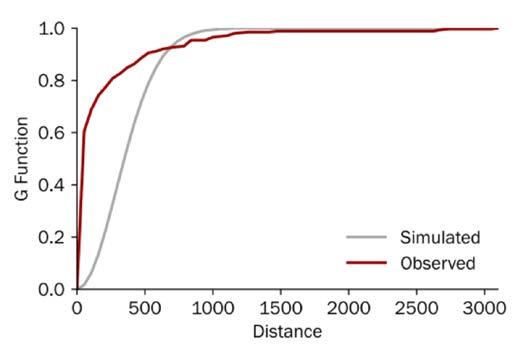

In the accompanying figures we examine the distribution of competitors in three healthcare industries, retail pharmacy, veterinary, and private medicine across a portion of London.

In the cases of veterinary clinics (see Figure Two) and private medical offices (see Figure Three), a visual inspection of each map can provide some quick insights. However, in the case of retail pharmacies (see Figure One), the pattern is more ambiguous.

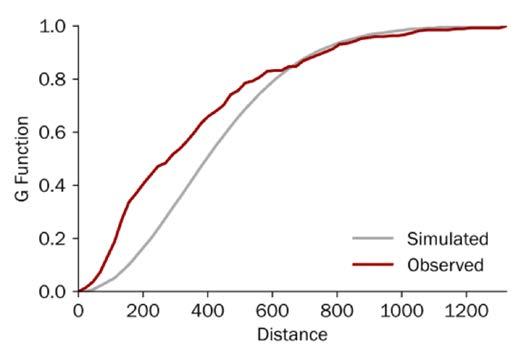

In general, humans are surprisingly bad at discerning patterns from randomness,1 so we lean on statistical approaches to identify and measure patterns. In this case, we use an analysis called Ripley’s G, which allows us to measure the level of clustering or dispersion for a range of sizes of ‘neighbourhood’ by measuring the proportion of locations whose nearest neighbour (think competitor) is within a given range. We then compare the observed distribution with a set of simulated random patterns: observed curves above the simulated curve exhibit clustering and curves below the simulated curve exhibit dispersion.

Retail pharmacy is a relatively undifferentiated industry, so the sector mostly follows Hotelling’s Law: chemists are often best off on high streets, where there is the most foot traffic, and they split the local market with co-located competitors. While the distribution of pharmacies around London may visually appear random, nearly all have a competitor within a very short walking distance (see Figure One).

The line graph demonstrates that chemists are more often very close to one another than they would be under a random process (c.40% have another store within 200m), so the industry is exhibiting Hotelling-like features.

Chemists are primarily fixed cost businesses, and sites can usually move within a few hundred metres without a change of license, so being subtle about exactly where the pharmacy is on the high street can be quite impactful.

Furthermore, because competitors are piled onto the same street, there is opportunity to extend the ‘virtual distance’ by investing in the environment or improving the service level to lure customers the

50 metres past competitors to a nicer experience.

Revisiting the chart, interestingly, the observed distribution mimics the random one in some cases, which indicates that there are some pharmacies that unexpectedly sit further apart from others. These more isolated locations may be on quieter streets with differentiated offerings, or they may be on streets with a supply/demand mismatch.

In contrast to pharmacies, and the simulated distribution, veterinary practices are particularly dispersed (see Figure Two). In fact, in this region, no first-opinion practice has another one within 575

metre as the crow flies, an approximately 12-minute walk.

In our own research, we found that proximity is the number one reason for choosing a first-opinion clinic and it ranked well above perceived value, which means that customers want convenience, and the market is likely exhibiting monopolistic competition.

Importantly, this does not mean that veterinarians are exerting excess market power, it just means that customers are willing to pay for convenience and for many customers their nearest practice is a bit closer than others. On the contrary, we have also found that pet owners are perfectly willing to travel for differentiated services, for instance specialist care.

On the other hand, one could also argue that general practice vets are distributed in urban areas because the purchasing decision is driven so much by proximity, the distances people are willing to travel are small, and the population density is generally low enough that there is only enough demand to support one practice within the range that pet owners are willing to travel. In either case, we primarily find veterinary clinics on quiet residential streets because vet clinics are actually damaged by an over-abundance of nearby activity – no one wants to walk their sick puppy through a crowded street – which is why there are no practices in the busiest parts of town (the gap near the centre and bottom of the map).

Now that we know the typical distribution of practices, we can programmatically scour similar areas around the country to identify gaps in supply that could be attractive places to build new practices.

While dispersion among veterinary clinics benefits many pet owners, dispersion among hospitals would benefit much of society.

Emergency care is, tautologically, urgent, and universal access is in the mandate of state-sponsored care. However, as one can discern from cursory analysis of NHS Acute Trust catchment populations, services are not optimally located, and this is due to the constraints of the built environment.

Veterinarians can open, close, and move clinics with ease, which allows market forces to promote an optimal configuration, but hospitals are huge and have important infrastructure requirements, which makes their location subject to path dependence, and the equality of an arrangement of services erodes as people and needs move.

Finally, private medical practices are intensely clustered, mostly around Harley Street, which has been a hub for private practitioners since the end of the 19th century.

In earlier years, the benefits of the agglomeration effect (knowledge sharing and so on) were likely more powerful than they

BUILDING MODELS THAT EFFECTIVELY EVALUATE WHETHER A LOCATION IS SUITABLE FOR A BUSINESS IS BOTH A COMMERCIAL AND ACADEMIC PROCESS

are today, but most practices on Harley Street are single-specialty or few-specialty groups and they benefit from the ability to refer patients to nearby practices.

Probably the greatest benefit of being on Harley Street today is the economic signal: most people in London assume that the best private doctors practice there. In addition to hefty lease payments, Harley Street doctors garner prestige from their choice of location.

Economics professors would argue that much of the signal comes from the high rents – the ability to afford the space means those doctors must create significant value for their patients. Anyone wanting to establish a premium brand would struggle to find a better place than Harley Street for a flagship clinic. Moving up a level, spontaneously creating these types of networks is very difficult, but local government, property estates, and landlords play a very important role in either limiting or fostering their development.

We have examined some phenomena and how we measure them, and you might be thinking this is all a bit academic. But building models that effectively evaluate whether a location is suitable for a business is both a commercial and an academic process. Much like in the beach example, we iteratively layer-in reality and theory and then test outputs using statistical methods. This requires deep understanding of how a market works, what makes a location good for a particular business, and the academic approaches to identify and quantify market opportunities.

NOTES

1 Williams, Joseph Jay and Thomas L. Griffiths. Why are People Bad at Detecting Randomness? Because it is Hard. (2008), princeton.edu.

Riding the Covid-19 wave, PE healthcare IT (HCIT) deals, including buyouts, add-ons, and growth investments, grew by a record CAGR of 18.6% between 2019 and 2021. That level of exuberance has slowed in 2023, but the run-rate for addons continues to grow and this year is set to become the second most active for such transactions in the past decade.

Recent deals have included CVC Capital Partners’ acquisition of UK-based System C Healthcare and its partner company Graphnet Health in 2021 (HCIT systems and services), ARCHIMED’s acquisition of Italy-based Cardioline in 2021 (cardiology diagnostics and cardiology-focused telemedicine), and Hg and TA Associates backed The Access Group acquisition of UK-based Servelec in 2021 (provider of healthcare and case management software, which the previous month had acquired Elemental, the most widely used digital social prescribing platform in the UK and Ireland).

We believe the HCIT space offers an attractive theme for investors combining defensive (healthcare) with growth assets (tech) and offering strong customer stickiness and attractive recurring revenue streams. We forecast the market to grow, driven by system pressures and new models of care delivery, underpenetrated markets, and strong public funding tailwinds.

Investors should focus on rolling-up solutions that are geared towards clearly defined and prioritised problems that can easily integrate into existing HCIT landscapes, and that offer high security standards. To pick the right assets, investors will need to really understand the clinical and patient models of markets in which target assets operate.

There is an ever-increasing number of digital health solutions, also covering apps and wearables, but we will focus on second generation technology in the care provider setting as this is a more mature market and hence more relevant for private equity (PE) investors. These assets include solutions for decision/risk analysis, enterprise system management, Electronic Health Records/Electronic Patient Records (EHR/EPR), outcome management, telehealth solutions, and other related HCIT services (see Figure One).

Grand View Research valued the European digital health market at US$45.3bn in 2022, expecting it to grow at a CAGR of 16.0% from 2023 to reach US$148.5bn by 2030.1

In the UK, LaingBuisson estimates that HCIT spend in 2020 was £5bn (US$6.33bn), of which c.33% went on clinical systems, c.30% to staffing and workforce, c.20% on infrastructure spending (e.g. hardware, networks), c.15% went on non-clinical systems (e.g. HR, finance, governance), and c.2% on so-called third generation technology (e.g. apps, patient facing services).2

Three players dominate the UK market with a combined c.40% to c.60% of the Electronic Prescribing and Medicines Administration (ePMA), EHR/EPR, and Patient Administration Systems (PAS) markets: Italy-based Dedalus (backed by Ardian), US-based Cerner (acquired by Oracle in 2022), and UK-based System C (backed by CVC Capital Partners). These markets differ slightly, however, in terms of exact make-up and who leads.

Remaining larger players in these markets tend to be US-based, and often listed. UK-based and privately held Nervecentre is a notable exception in the UK EHR/EPR market - the company has recently been chosen as the preferred

supplier for a new joint EPR system by two Derbyshire trusts.3

Some trusts have also constructed their own EHR/EPRs (c.8.3% or the market in England in 2022) and 10% of acute Trusts in England lack an EHR/EPR altogether. Further, c.30% lack an ePMA system, and c.50% lack a digital document management system.4,5,6

PE HCIT deals in Europe grew by a record CAGR of 18.6% between 2019 and 2021 (see Figure Two) and grew faster than PE deals overall (4.3% CAGR). HCIT deals as a percentage of the total also reached alltime highs of 1.5% in 2021 and 2022, and 1.6% in (year-to-date) 2023.

Although there has been a slowdown in the number of completed deals in the first three quarters of 2023 (see Figure Three), reaching its lowest point since Q3 2020. The current year is still positioned to be a strong year for HCIT.

For HCIT companies relying heavily on growth, inflation can diminish the value of future returns, especially for companies with lower pricing power. Inflation, coupled with a high interest rate environment impacting investor willingness to pay, has resulted in a decrease in both buyout and growth investment deals. Hence, Livingbridge’s investment in T-Pro (AI-powered speech technology and clinical documentation solutions) is the only growth investment in 2023 YTD. This is compared to five growth deals in 2022 and 2020, and three in 2021.

Add-ons have also been impacted, with the number of deals falling both in Q2 and Q3 this year, but these transactions remain at similar levels per quarter as registered in 2022.

Article focus

Setting

Main industry specific systems (nonexhaustive)

Supporting industry agnostic systems

Care provider Setting

Clinical systems

• Screening and diagnostics

• Telehealth

• Electronic Patient Records Systems (EPR/EMR/EHR)

• Picture Archive and Communication System (PACS), and Radiology Information System (RIS)

• Electronic Prescribing and Medicines Administration (ePMA)

• Patient Administration Systems (PAS)

Non-clinical systems

• Workforce management

• Facilities and supply chain management

• Regulatory and legal

• Contract management

Homecare setting

Communication and patient engagement systems

• Patient portals

• Referral pathways

Platform and infrastructure

Analytics

Other support systems

Remote and self-care systems

• Apps

• ‘Doctor on demand’ services

• Home monitoring

• Social prescribing

Run-rating all deals in 2023, this year is still positioned to be the third most active for PE HCIT deals since 2014 illustrating that investor interest remains strong.

Some 29.3% of all PE HCIT deals since 2014 have involved British assets, making it the most active market in Europe. The UK is followed by Germany (16.6%), and the Netherlands (12.7%)

Recent PE buyouts of UK HCIT assets include CVC Capital Partners’ acquisition of System C in 2021, Ardian backed Dedalus’ acquisition of swiftQueue Technologies in 2021 (healthcare appointment and patient engagement solutions), and Livingbridge’s acquisition of Nourish Care Systems in 2022 (digital care planning software).

The investor landscape is very fragmented, with c.66% of HCIT investors having only completed one deal, and c. 18% only two deals in the past decade.7

There have, however, been examples of PE asset roll-ups, with HCIT add-ons growing more than both buyouts and growth investments in the past ten years. A prominent example is RLDatix, a UK-based company that develops and supplies risk management and patient safety software (see Figure Six).

Since TA Associates invested in RLDatix in 2018, joining existing investor Five Arrows Principal Investments, the software company has proceeded to roll up multiple other healthcare software businesses in the UK and the USA. These include Verge Solutions in 2020 (credentialing software), Allocate in 2021 (human capital management solutions), and

Galen Healthcare Solutions in 2022 (implementation, optimisation, data migration and archival solutions for HCIT systems provider).

Another example is Ardian backed Dedalus, which acquired Agfa HealthCare’s IT business in 2019 (healthcare information solutions and integrated care activities) as well as Dosing GmbH (SaaS medication safety solutions) and swiftQueue Technologies, both in 2021.

HCIT roll-ups makes sense to investors as it represents a shortcut to expanding an asset’s offering; it can offer salesforce synergies and economies of scale.

According to Martin Bell, a former board CIO in the NHS, the former deputy MD of EMIS Health, and the author of the LaingBuisson Digital Health UK market report, private equity is particularly well suited for these roll-up plays.

‘Especially medium to large sized companies can benefit from PE roll-ups. These companies often have quite a few bits

FIGURE TWO GLOBAL PE HEALTHCARE IT DEALS ‒ ANNUAL

AFTER A SHARP INCREASE IN PE HEALTHCARE IT DEALS POST-COVID WE ARE NOW SEEING A SLOWDOWN NUMBER OF COMPLETED DEALS, EUROPE, 2014‒2023 YTD

WE ARE SEEING A STEADY DECLINE IN THE FIRST THREE QUARTERS OF 2023 NUMBER OF COMPLETED DEALS, EUROPE, PER QUARTER YTD

missing that can’t be filled by third parties who may or may not be out there. It makes the cost of operations, partnerships, delivery operations so much higher. The ability to acquire add-ons and integrate them is what PE is good at. It’s a consolidation play.’

Conversely, some providers may be too small to succeed on their own ‒ for instance lacking the salesforce or capabilities needed to compete in larger tenders ‒ and will therefore benefit from the scale offered by a consolidator.

Demographic changes and staff shortages have led to significant pressures on healthcare systems, which have often been made worse by the pandemic and subsequent backlogs. Care providers therefore need to find efficiencies, something that digitalisation can offer.

Models of care delivery are also changing, and patients will have a growing want and need for data accessibility to support care provision outside of, but linked to, a hospital setting.

Consequently, the volume of healthcare data has been growing rapidly, with RBC Capital Markets projecting a CAGR of 36% in global healthcare data until 2025.8 With increasing volumes, however, there is a greater need to store, transfer, and process this data. Here HCIT solutions play an important role.

The percentage of clinicians using digital technologies varies significantly between European countries. In a 2020 Deloitte survey, 97% of Dutch clinicians reported using EHRs, versus 77% of German clinicians, and 69% of Italian clinicians. Similarly, digital prescription was used by 97% of Dutch clinicians, versus 73% or Danish clinicians, and only 13% of German clinicians.9 Further, 10% of acute Trusts in England lack an EPR, and 30% lack an ePMA system.10

These disparities should provide significant headroom for HCIT companies to grow.

As the largest healthcare market outside of the US, Germany launched The German Hospital Future Act (KHZG) in 2020, making €4.3bn in funding available for investments into patient portals, electronic documentation of care and treatment services, digital medication management, and the introduction or improvement of telemedicine.11

In France, the Ségurdudigitalensanté programme, also launched in 2020, includes a €2bn (US$2.18bn) investment into development of digital health. The programme’s objective is to ensure the smooth and secure exchange of health data between health professionals and users.12

At the European level, the EU has committed €1bn towards digitalising healthcare over the coming seven years. This includes the creation of the European Health Data Space (EHDS), which among

THE INVESTOR LANDSCAPE IS FRAGMENTED, WITH c.66% OF HCIT INVESTORS HAVING ONLY COMPLETED ONE DEAL NUMBER OF COMPLETED DEALS, EUROPE, 2014-2023 YTD

Acc. Deals

other things, aims to digitise all medical records in the bloc by 2025, making it easier for individuals to access and share their data with medical professionals, particularly when in another EU country.13,14

In England, the Frontline Digitisation programme, launched by NHS England (NHSE) and the government in 2021, set a target that 90% of acute NHS trusts would have EPRs by December 2023. This was achieved in mid-November 2023. The remainder are to follow by March 2025.15,16,17,18

However, a NHSE guidance letter sent to trusts in November 2023 suggested that parts of the Frontline Digitisation programme could be pulled from all but the least digitised trusts to counter the impact of strike action. The programme had already been reduced from £2.6bn to £2bn in FY23.19

Funding will likely remain one of the key growth challenges in England. Hence, although 2020 digital health spending represented on average c.2% of NHS Acute Trust turnover (up from the c.1.4% a decade ago), this is significantly below, for instance, the Nordics at an estimated c.6‒8%.20

For HCIT solutions to be attractive investments, they need to be geared towards clearly defined problems, and ideally, should prove either substantial risk mitigation or improved patient outcome, improved efficiency and cost reduction, revenue increase (preferably in-year if targeting public sector clients), and/or enhanced clinician experience.

Solving a problem is not enough, however, as healthcare providers will often have constrained budgets and will need to prioritise their spending.

‘If you’re selling something that has ringfenced specific funding, and if it’s really fixing an urgent thing, then you can get traction,’ says Bell.

Further, solutions, unless stand-alone, also need to easily integrate into the end users’ existing technology landscape, the broader organisational structure and ecosystem, and existing care pathways (both digital and physical).

Finally, solutions need to have high security standards (both cyber security and patient data compliance).

Healthcare providers are typically risk averse when it comes to changing systems and will want to see robust evidence of safety and efficacy before adopting a new system; changing systems requires a lot of effort in what are often strained organisations.

‘The reason for stickiness is multifactorial,’ says Bell. ‘One of the biggest things is the amount of effort required - write a business case and go through procurement - while you have so many other priorities as a healthcare provider.’

This slow pace of technological adoption and long sales cycles/adoption means that investors sometimes find it hard to validate returns. Companies with a track-record of growth ‒ by either displacing competition or growing accounts ‒ and that have long customer relationships and can show surviving evaluation cycles, should provide attractive targets for HCIT investors.

Roll-ups enable investors to rapidly build their capabilities: gaining clear salesforce synergies and the possibility to provide scale to smaller assets.

Investors must consider the local conditions of markets in which the target assets operate. This includes understanding diverse and often fragmented commissioning landscapes, regulatory variations by region and country, clinical and patient models (such as patient access to care and patient pathways), interoperability challenges, and privacy and data security concerns (mainly regulatory limitations, but sometimes also cultural perceptions). Though not all these challenges will be specific to HCIT, these can significantly limit the scalability of HCIT.

There has been a lot of investor interest in the HCIT space in recent years, and we expect that to continue.

Favourable market drivers and strong funding tailwinds, coupled by underpenetrated markets leaving headroom for growth, make the HCIT space an attractive theme for investors. Interested investors should focus their attention on solutions geared towards clearly defined, and prioritised problems, and roll up assets with a proven track record of growth.

FIGURE SIX

RLDATIX HAS ROLLED UP MULTIPLE HCIT COMPANIES IN THE UK AND US CASE

SELECTION TA Associates invests in Datix Five Arrows Principal Investments, an existing investor, maintains a significant equity stake in Datix Datix acquires RL Solutions, a provider of healthcare quality and patient safety software and rebrands to RLDatix

RLDatix acquires Verge Health, a US based provider of credentialing software for healthcare sector

NOTE 2018 2018 2020 2021

RLDatix based provider of contract management solutions for healthcare, insurance, life sciences and other industries RLDatix acquires Galen Healthcare Solutions, a US-based implementation, optimisation, data migration and archival solutions for HIT systems provider

2022 2021

1 Grand View Research - Europe Digital Health Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Technology (Tele-healthcare, mHealth, Healthcare Analytics, Digital Health Systems), By Component, By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2023‒2030 - Press release

2 Digital Health UK market report – third edition, LaingBuisson

3 DigitalHealth.Net (3 November 2023): Two Derbyshire trusts pick Nervecentre as preferred supplier for joint EPR. Available at: https:// www.digitalhealth.net/2023/11/two-derbyshire-trusts-pick-nervecentre-as-preferredsupplier-for-joint-epr/#:c. :text=for%20joint%20 EPR-,Two%20Derbyshire%20trusts%20 pick%20Nervecentre%20as%20preferred%20 supplier%20for%20joint,patient%20record%20 (EPR)%20system. (accessed 27 November 2023)

4 Digital Health UK market report – third edition, LaingBuisson

5 Mansfield interview

6 NHS Digital (16 November 2023): 90% of NHS trusts now have electronic patient records. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/ news/2023/90-of-nhs-trusts-now-have-electronic-patient-records (accessed 21 November 2023)

7 Preqin

8 RBC Capital Markets: The healthcare data explosion. Available at: https://www.rbccm. com/en/gib/healthcare/episode/the_healthcare_data_explosion#:c. :text=Today%2C%20

ONLY SOURCE PREQIN – DATA UNTIL 30 SEPTEMBER 2023, MANSFIELD RESEARCH RLDatix acquires Allocate Software, a UK based provider of human capital management solutions for the healthcare sector

approximately%2030%25%20of%20the,for%20healthcare%20will%20reach%20 36%25.https://emerj.com/ai-sector-overviews/ where-healthcares-big-data-actually-comesfrom/ (accessed 20 November 2023)

9 Deloitte (September 2020): Digital transformation: Shaping the future of European Healthcare. Available at: https://www2.deloitte. com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/lifesciences-health-care/deloitte-uk-shaping-thefuture-of-european-healthcare.pdf (accessed 16 November 2023)

10 Digital Health UK market report – third edition, LaingBuisson

11 Healthcare IT News (22 September 2020): German hospitals to get €3 billion funding boost for digitalisation. Available at: https:// www.healthcareitnews.com/news/emea/german-hospitals-get-3-billion-funding-boost-digitalisation (accessed 20 November 2023)

12 Ministry of Solidarites and Health (Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention): Le Ségur du numérique en santé. Available at: https:// esante.gouv.fr/segur (accessed 16 November 2023)

13 Healthcare IT News (8 June 2023): European healthcare digitalisation at inflection point. Available at: https://www.healthcareitnews. com/news/emea/european-healthcare-digitalisation-inflection-point (accessed 16 November 2023)

14 European Commission: European Health Data Space. Available at: https://health. ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/

european-health-data-space_en (accessed 17 November 2023)

15 NHS England: Digitising the frontline. Available at: https://transform.england.nhs.uk/ digitise-connect-transform/digitising-the-frontline/ (accessed 21 November 2023)

16 NHS South, Central and West (SCW): Frontline digitisation programme supports ambitious Electronic Patient Records targets. Available at: https://www.scwcsu.nhs.uk/case-studies/ frontline-digitisation-programme-supports-ambitious-electronic-patient-records-targets (accessed 21 November 2023)

17 NHS Digital (16 November 2023): 90% of NHS trusts now have electronic patient records. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/ news/2023/90-of-nhs-trusts-now-have-electronic-patient-records (accessed 21 November 2023)

18 DigitalHealth.Net (25 July 2023): EPR frontline digitisation target declared ‘unachievable’. Available at: https://www.digitalhealth. net/2023/07/epr-frontline-digitisation-target-declared-unachievable/ (accessed 21 November 2023)

19 DigitalHealth.Net (15 November 2023): Frontline digitisation funds at risk to cover industrial action costs. Available at: https:// www.digitalhealth.net/2023/11/frontline-digitisation-funds-diverted-to-cover-industrial-action-costs/ (accessed 21 November 2023)

The CQC has moved to a system of more targeted inspections, designed to help accelerate improvement where it is most needed, but that can mean long gaps between inspections for the best performing facilities.

Abhishek Patel takes a deep dive into the impact of the changes on acute and mental health hospitals and discusses the implications for investors

t the forefront of any investor’s key priorities when assessing providers in health and adult social care, must be the topic of quality. Acquire a poor-quality service, and significant management time and resource will be required to turn things around; conversely, a good-quality service will be more profitable and more valuable.

In England all health and adult social care services are independently regulated by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), an arm’s length body of the Department of Health and Social Care which monitors and inspects sites and publishes quality reports with a simple 4-point rating scale (outstanding, good, requires improvement, inadequate). Other parts of the UK have equivalent independent regulatory bodies – Health Inspectorate Wales, the Care Inspectorate and Healthcare Improvement Scotland, and The Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority in Northern Ireland.

But while these reports provide a useful site-level proxy for quality, they mask the nuances behind ratings at a sub-sector and provider type level and are ultimately a ‘snapshot in time’ – the periods between inspections can be long and a lot can change. As a result, careful expert diligence is required to truly understand a provider’s real quality and their outlook.

This article analyses some key operational metrics for the CQC over the last five years, before taking a deep-dive into acute and mental health hospitals.

The CQC was established in 2009 to independently regulate all health and adult social care services in England, thereby consolidating its three predecessor organisations (the Healthcare Commission, the Commission for Social Care Inspection and the Mental Health Act Commission). Its primary aim is to ensure all services provide people with safe, effective, compassionate, high-quality care. More specifically, its key roles are to (1) register all health and adult social care providers; (2) monitor and inspect services to ensure they are safe, effective, caring, responsive and well-led, and subsequently publish quality ratings; (3) enforce changes through legal action when poor care is identified.

Ian Trenholm was appointed CEO in August 2018, taking over from Sir David Behan who had been in post since 2012. Whereas Behan had a strong social care background prior to joining the CQC, with executive positions at the Commission for Social Care Inspection and the Department of Health, Trenholm started his career as an Inspector in the Royal Hong Kong Police Service. He subsequently held executive positions at NHS Blood and Transplant, the Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), and the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead before joining the CQC. Under his leadership, the CQC has weathered the storm of Covid-19 which caused significant disruption to inspection activity, and

has moved towards a risk-based ratings approach where struggling providers are prioritised to drive improvement. In tone, the CQC is seen as moving from a more collaborative regulator seeking to help providers improve performance to a more proactive and assertive regulator, looking to prosecute more poor providers.

In 2021, the CQC set out four strategic priorities:

1. People and communities focus on the experience of people and what is important to them when they access, use and move between services

2. Smarter regulation provide up-todate and high-quality information and ratings, simplify interactions and ensure responses are more proportionate

3. Safety through learning prioritise learning and improvement to ensure stronger safety cultures

4. Accelerating improvement empower systems to improve quality of care where it is needed most

But how does this reflect in the numbers, and have we seen a change in activity since Trenholm’s appointment as CEO in 2018? We analysed some of the key operational metrics to understand how the CQC’s recent activity stacks up against its funding and resources.

NOTES FINANCIAL YEARS END 31 MARCH 1 THIS CONSTITUTES c.90% OF TOTAL CQC REVENUE; THE REMAINDER IS MOSTLY DHSC-PROVIDED GRANT-IN-AID FUNDING 2 INCLUDES HOSPITALS, COMMUNITY, SINGLE SPECIALTY AND DENTISTS 3 INCLUDES ENFORCEMENT, INDEPENDENT VOICE AND OTHER ACTIVITY NOT FUNDED FROM FEES (SUCH AS THEMATIC REVIEWS)

SOURCE CQC ANNUAL REPORTS, MANSFIELD ANALYSIS

The CQC receives c.£200m income from fees charged to registered providers (see Figure One), which constitutes c.90% of its total revenue; the remainder is mostly DHSC-provided grant-in-aid funding. Around half of its fee income is from independent sector providers, predominantly adult social care (c.40%), but also hospitals, community and single specialty providers, and dentists (together c.10%). Income and employee numbers have remained largely flat over the last five years, which indicates relatively stable resource capacity, although funding may have been hit by recent inflationary pressures – the average salary for a CQC inspector is now estimated to be £38,328.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, expenditure shifted away from inspection towards monitoring, given extreme pressures which prevented on-site inspections. However, while expenditure on inspections has somewhat recovered to pre-pandemic levels, a closer look at overall inspection frequency reveals a longer-term decline that predates the pandemic (see Figure

Two). Mansfield sent an FOI request to the CQC to segment inspection activity by provider type; the results show adult social care and primary medical services have seen the greatest decline since 2016 of 12‒15%, but hospitals have also seen a marked 7% drop in inspection activity. Given all health and adult social care services must be registered with the CQC, fees charged to providers is effectively a ‘tax’ on the independent sector to be appropriately regulated and for quality standards to be maintained. It follows that all independent sector providers might reasonably expect frequent monitoring and inspections (and more importantly re-inspections) to give a current and relevant quality rating.

However, while CQC employee numbers have remained around 3,000 over the last six years, the number of inspections per employee has declined by c.2x since 2016. Taken together, this indicates inspection activity has been in sharp decline despite relatively stable resources and is yet to return to peak levels. This trend cannot be explained by the Covid-19 pandemic given inspections have not returned to pre-pandemic levels and resourcing is similar, but by key changes

in the CQC’s inspection strategy.

Historically, if a service was rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’, the CQC aimed to conduct a full inspection within five years. However, since 2021 the CQC has been taking a more ‘risk-based’, targeted approach to inspection, and only inspects sites where there is a clear risk to safety (i.e. prioritising struggling sites). For all other sites, the CQC has conducted c.20,000 ‘direct monitoring activity’ (DMA) assessments over the last three years – these entail speaking to service users and analysing data directly from providers, without going on-site to conduct a full inspection.

The CQC is also rolling out its new ‘single assessment framework’ for reports, which replaces key lines of enquiry (KLOEs) with new, standardised ‘quality statements’. However, there is an even greater risk of losing context at the expense of striving for consistency.

Caroline Barker, non-practising solicitor at the law firm Ridouts points out: ‘While these new quality statements are better aligned to regulations compared to the KLOEs they replace, it remains to be seen whether the proposed ‘ongoing assessments’, rather than inspection, will

CQC INSPECTION ACTIVITY WAS DECLINING EVEN BEFORE COVID-19, AND REMAINS c.50% BELOW PRE-PANDEMIC LEVELS

‘000S, CQC INSPECTIONS

be used as a means to avoid the CQC’s statutory obligations to produce a full written report that a provider can review and respond to. We’ve also seen more enforcement action by the CQC over the last five years, and it’s become harder to get changes to reports than it used to be – so we might find more judicial reviews with the new system.’

So, while dedicating resources to struggling sites aligns with the CQC’s key strategic pillar to accelerate improvement where it is needed most, its implementation also creates uncertainty over the quality of services rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ in inspections that in some cases were six or seven years ago. Moreover, complaints and whistleblowing enquiries (see Figure Three) are on the rise and at their highest ever levels, so it is surprising this has not resulted in more inspections.

Private acute hospitals and mental health hospitals are two provider types that have seen contrasting trends in CQC ratings over the last five years.

THE QUALITY GAP BETWEEN THE NHS AND THE TOP SIX PRIVATE GROUPS HAS WIDENED SIGNIFICANTLY OVER THE LAST FIVE YEARS

%, SHARE OF LOCATIONS RATED ‘GOOD’ OR ‘OUTSTANDING’

The top six private acute hospitals have seen their CQC ratings increase consistently, whereas their NHS counterparts have seen a steady decline since Covid-19 (see Figure Four).

While these groups have always had superior quality ratings to the NHS, the gap has widened significantly. Roughly 95% of locations from the top six groups are rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ compared to just c.55% of NHS acute hospitals; a stark difference which not only articulates the extreme pressures faced by the public healthcare system, but also indicates how strong leadership and effective collaboration with the CQC in the independent sector can drive quality improvements.

Private acute hospitals saw more inspections than pre-Covid-19 in 2022 (see Figure Five), with c.25% of rated locations inspected (similar to 2019 levels), following reduced activity during Covid-19. Of the 44 locations inspected, only three decreased in rating; 11 increased, 21 saw no change, and nine were inspected for the first time.

In contrast, NHS acute hospital inspection frequency has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels yet and many rating for both NHS and private are out

ROUGHLY 95% OF THE TOP SIX GROUPS ARE RATED ‘GOOD’ OR ‘OUTSTANDING’ COMPARED TO JUST c.55% OF NHS ACUTE HOSPITALS; A STARK DIFFERENCE WHICH ARTICULATES THE PRESSURES FACED BY PUBLIC HEALTHCARE

CQC filtering methodology

• Location primary inspection category: Acute hospital

• Top six private groups:

o Circle Health Group (formerly BMI Healthcare)

o Spire Healthcare

o Ramsay Health Care UK

o Nuffield Health

o HCA

o Practice Plus Group

of date. As at August 2023, the average time since last inspection for NHS acute hospitals was 3.8 years for ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ sites compared to 1.9 years for ‘requires improvement’, and 1.2 years for ‘inadequate’; therefore, ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ sites were being rated c.2x less frequently.

However, for the top six private groups, the average time since the last inspection was 3.7 years for ‘good’, ‘outstanding’ and ‘requires improvement’ locations, so the rating appears to have no impact on inspection frequency.

Private mental health hospitals have seen a very different profile – five years ago independent providers had 14% more ‘good’ and ‘outstanding’ ratings than the NHS, while today they have 9% fewer. They have seen a steady decline in CQC ratings by 10 percentage points since Covid-19, while NHS mental health trusts have largely been unchanged (see Figure Six).

A number of leading private providers including St Andrew’s Healthcare, InMind and CareTech have had multiple services downgraded. A closer look at the key lines of enquiry (KLOEs) in inspection reports reveals safety and leadership concerns

FIGURE FIVE ACUTE HOSPITALS – INSPECTION FREQUENCY

INSPECTED MORE IN 2022, FOLLOWING REDUCED INSPECTION ACTIVITY DURING COVID-19

INSPECTED

FIGURE SIX MENTAL HEALTH HOSPITALS – RATINGS

‘GOOD’ OR ‘OUTSTANDING’

as the key drivers for lower ratings. The mental health sector as a whole has faced profound system pressures since Covid-19, with high staff churn and persistent shortages, and a lack of training often cited.

Nevertheless, it is clear that staffing capacity and investment is needed in a sector which faces increasing demand and that often deals with the most challenging of patients in the health system.

Without consistent monitoring and frequent inspections, can providers be credibly held to account over service quality? The CQC rightly provides critical and necessary regulatory oversight to ensure patients receive the best care possible. However, when investors are looking to buy assets, CQC reports and summary ratings mask the nuances at the sub-sector and provider type level.

A private mental health hospital provider with a high proportion of ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ sites should be considered particularly attractive when contextualised to the overall decline in ratings in this sub-sector.

Conversely, a private acute hospital provider with declining ratings should be approached with caution given the high and increasing ratings of the top six groups.

In addition, diligence now also needs to encompass how providers participate in an integrated health and care economy. Chris Day, director of engagement at the CQC, points out: ‘Six years ago, quality was about how well you manage inside your organisation – having good processes and workflows; what will define the next six to seven years will be how well they take part in that wider system, particularly in the NHS.’

Investors always require assurance on quality, but ratings from inspection reports are only a starting point - to truly understand quality, there is no substitute for in-depth site visits, conversations with key site-level personnel and the expertise of a commercial due diligence specialist.

Germany has a large private hospital sector in comparison to the UK. Arne Berndt, partner at WMC Healthcare, and Paul Fegan consider whether the differences in respective sectors are due to contrasting healthcare systems, and whether any of the conditions that result in Germany’s large private hospital sector are transferable to the UK

In April 2023, Mansfield Advisors compared UK and Spanish private hospitals, highlighting the significant differences in scale and scope of the two sectors, despite both having similar tax-funded universal healthcare systems with complementary private health insurance. Our article (see page 20) concluded that Spain has created the conditions for large private hospitals to thrive by having a far larger privately insured population and regional governments more willing to experiment with public-private solutions.

Germany has an even larger private hospital sector. Eurostat data shows nearly 60% of hospital beds in the €114bn acute hospital market are private , while only 40% are run by public hospitals. This is in marked contrast to the UK, where roughly 5% of beds are in the private sector, and Spain, with 32% in the private sector (see Figure One). Like Spain, German private hospitals include ‘full-service’ general hospitals, in contrast to the UK’s small sites offering a limited range of elective procedures.

Germany has a lot of beds, both in absolute terms (437,000) and relative to population (see Figure Two).

Excluding psychiatric beds, German federal statistics for 2021 show 33% of beds (146,000) are not-for-profit and 19% (83,000) are for-profit. The for-profit sector is highly concentrated, with the four biggest groups accounting for 61% of for-profit beds (12% of total beds). By contrast, the not-for-profit sector is much more fragmented (the top five have 15% of not-for-profit beds) and public hospitals

are even more fragmented (see Figure Three).

About half (48%) of all hospital beds are in large hospitals (>500 beds), and nearly two-thirds of these are in public hospitals. At the other extreme, 15% of beds are in small hospitals (<200 beds), and 42% of these are for-profit. The latter partly reflects the prevalence of highly specialised small hospitals, such as those focussing on sports surgery, which can be highly profitable.

Germany’s universal healthcare system is the original social insurance model. Employees and employers contribute to public health insurance funds, with the federal government setting a contribution rate for salaries up to c.€65,000. These insurance funds then reimburse providers on behalf of their members. All Germans are required to have insurance, and the funds cover family members, retirees and the unemployed.

Superficially, the German and UK systems look similar: instead of general taxation, Germans are, in effect, ‘taxed’ through social insurance. Unlike the UK, though, where private insurance is complementary (we cannot opt out of paying taxation), Germans who earn over €65,000 can choose substitutive private insurance and opt out of the public insurance system entirely. (There are controls on re-joining the public system to prevent adverse selection.)

However, the payor model is not the driver of Germany’s large private hospital sector per se. First, the proportion of the German population with private insurance

is not significantly greater than the UK. Around 12.5% have substitutive private insurance, compared with approximately 10% in the UK and c.25% in Spain covered by complementary private insurance, and this has been declining slowly as it becomes more expensive and relatively less attractive to Germany’s ageing population (see Figure Four). Secondly, private and social insurance payors are not limited to private or public hospitals exclusively.

The critical difference between the UK and German models is that the latter enables individuals to be consumers of healthcare (‘demand-led’), whereas healthcare in the UK is viewed as a public good/service (‘supply-led’). To be clear, Germany’s social insurance system does not in itself create a large private sector (France has a similar model, but only 38% of beds are private). It simply creates the conditions for healthcare markets to develop.

Theoretically, markets are self-regulating, but governments usually intervene where consumers and/or producers cannot make economically rational choices. For example, governments don’t directly control the market for cars, but do set safety and environmental standards. Similarly, Germany manages the market for hospital services, providing a level-playing field where patients choose where they are treated. Patient and payor can be agnostic about whether that is a private or public hospital.

Dual financing is a key component of the managed market, with frameworks

GERMANY HAS A LARGE PRIVATE HOSPITAL SECTOR (NOT-FOR-PROFIT) COMPARED TO OTHER EU COUNTRIES %, AVAILABLE HOSPITAL BEDS1 BY SECTOR, EXCLUDING PSYCHIATRIC CARE, 2018

Public

Not-for-profit

GERMANY HAS A LOT OF BEDS, BOTH IN ABSOLUTE TERMS AND RELATIVE TO POPULATION 000s BEDS, 20211

NUMBER OF BEDS1, PER 100,000, 2021

SECTOR CONCENTRATION

HOSPITAL BEDS BY PROVIDER GROUP AND SECTOR, 2020

Bremen

Munich

Rheinland

for supporting capital investment and to cover operating costs (see Figure Five):

• Capital investment funds (3% of hospital funding) administered by German states for new buildings and other projects. Public and private hospitals can bid for funding. States also plan hospital capacity, although this does not necessarily translate to explicit targets for bed numbers, nor the relative share of private and public sectors

• Operating costs (97% of hospital funding) German hospitals are reimbursed for activity delivered. A federal agency, the Institute for the Hospital Remuneration System (InEK), defines services and sets prices using a Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) system. DRG reimbursement covers around 80% of operating costs and is the product of a base rate and points per case, depending on complexity. It is used by all payors to reimburse all hospitals for inpatient services

There is a similar activity-based approach for reimbursing outpatient services, but different systems for social and private insurance. (Physicians receive 2.3 times more through private reimbursement.) Other services are generally billed on a fee-for-service basis.

In principle, the NHS in England is similar, and the architecture of hospital funding would be recognisable to German hospital operators. The National Tariff is comparable to the German DRG system, and private hospitals in England can contract to the NHS, receiving the appropriate tariff, just like their German counterparts. Capital funding for NHS hospitals is handled separately (although is not available to private operators). Yet, despite these similarities, we still do not have a large private hospital sector. What else is missing?

Different histories and cultures mean similar approaches to payment or organisation have different outcomes. When the NHS was founded in 1948, as an integrated, tax-funded service, there was still no reason why it had to own hospitals.

However, the existing patchwork of charity, church and municipal hospitals needed reorganisation, renewal, rationalisation and expansion, and centralised public ownership was seen as the best way to achieve that, as in other newly nationalised industries.

German charity, church and municipal hospitals have similar origins to the UK, but social insurance is much older than the NHS . Its decentralised separation of payor and provider meant public hospitals continued to be owned by municipalities and private hospitals remained independent not-for-profit institutions. However, with a demand-led system, Germans also became comfortable with choice. This is exemplified by supplementary private insurance which tops-up statutory cover for greater choice of consultant, private rooms, etc. Some 10% of Germans have supplementary private insurance and it has been growing. In the UK, there is resistance to anything which dilutes the idea of a universal ‘one-size-fits-all’ NHS.

It was the transition to dual financing which stimulated the growth of for-profit hospitals by forcing the privatisation of public and not-for-profit hospitals. The DRG system has been blamed for losses,

FIGURE FOUR

FIGURE FIVE

ALL

% OF HOSPITAL FUNDING BY SOURCE,

with smaller hospitals particularly vulnerable, since they struggle to generate case mix points to be profitable. Meanwhile, capital investment funds have left hospitals underinvested and, without sufficient resources, municipalities and even federal states have opted for privatisation. For example, Giessen-Marburg was sold by the state of Hesse in 2006 to become the first privatised university hospital. The number and share of private hospitals, therefore, continues to grow (see Figure Six).

There is another factor at work. As the government stimulates the development of outpatient, day patient and other ambulatory services to reduce reliance on inpatient services, the hospital system is consolidating. While there is no formal target for bed capacity, if Germany went as far as to converge on the EU27 average, there would be 173,000 fewer beds (almost as many beds as in the entire NHS across the UK). Hence, some hospitals will close.

Privatisation is seen as an alternative to closure. While the German public might be agnostic about who provides its healthcare, and is comfortable with choice and top-ups, they are perhaps still uncomfortable with the idea of making a profit out of ‘misfortune’. However, the private sector is also seen as a way to save hospitals which would otherwise be closed, and, for politicians, it is perhaps a way of shifting blame for those closures when they do happen.

Compared with the UK, Germany has a large private hospital sector because of a multitude of factors.

One is undoubtedly the fundamental difference between healthcare systems, creating the conditions in which hospitals of any sector could thrive within a managed market. However, the tools of managed markets, such as DRG reimbursement, also made it more difficult for public and not-for-profit hospitals to survive. In the UK – or at least in England – we have those same tools, but the

managed market still does not make large scale private general hospitals viable.

It is deliberate choice and culture which have played a much greater role. Culturally, Germans are accepting of their role as consumers of healthcare, and hence they are less concerned about whether the hospital is private, public, for-profit or not, as long as it meets their expectations on quality.

In terms of choice, the owners of loss-making hospitals have deliberately chosen to privatise as a way to sustain those hospitals that might struggle for investment or even close. The British are still a long way from seeing themselves as healthcare consumers, or accepting top-ups, and it would be a brave politician who decided to privatise a loss-making NHS trust. Mansfield Advisors and WMC Healthcare, together with Antares Consulting, form the Curis Alliance of specialist health and social care consultancies, with Europe-wide coverage.

Deals in the surgical ophthalmic equipment and products market reached a record high of 31 deals in 2022, with PE backed transactions also attaining new highs. Johan Ottosson and Dr Victor Chua see significant opportunities for this sector of the market

Global surgical ophthalmic equipment and products deals grew with a CAGR of 19% 2018‒2022 to a record high of 31 deals last year. PE or PE backed deals grew faster than the market overall with a CAGR of 26.6%, reaching a record 13 deals in 2022, almost twice that of the previous year.

Recent notable PE deals include Eurazeo’s acquisition of Dutch Ophthalmic Research Center International (DORC, led by CEO Pierre Billardon) for an estimated

€300m in 2019,1 and CVC’s acquisition of Rayner Surgical Group (led by CEO Tim Clover) for an undisclosed amount in 2021.

The most active investor in recent years however has been TPG Capital. Since its 2016 acquisition of US-based Beaver-Visitec International’s (BVI, led by president and CEO Shervin Korangy) TPG Capital has proceeded to roll-up multiple, mainly European, ophthalmology assets. Through this, TPG Capital has built a leading global platform estimated to have seen a reve -

nue growth of around 19% CAGR between 2017 and 2021.

Investor interest in the space is driven by attractive market fundamentals such as an ageing population, increasing treatment of pathologies, better access to healthcare, as well as stable public or insurance funding. Ophthalmic procedures tend to be inexpensive because they are almost always day-cases, and impactful because good vision is so important to normal productive life.

We therefore expect ophthalmic pro-

cedure growth exceeding growth in other surgical specialities. There are significant roll-up opportunities for investors in this space, notably in the US and Western Europe.

We estimate the global ophthalmology equipment and surgical products market to be worth around £20bn in 2023. Around 84% of this market is made up of equipment and products for the operating room (see Figure One).

The market for inside the operating room can broadly be broken down into products for the front of the eye, or the anterior segment (covering cataract, glaucoma, and refractive surgery), and products for the back of the eye, or the posterior segment (covering vitreoretinal surgery).

The anterior segment is by far the largest of the two, with a market size of

c.10x that of the posterior segment. It is also forecast to grow at a faster rate, with an expected CAGR of 6.5% 2023‒2027 (see Figure Two).

In this article we focus on the cataract and vitrectomy (VR) segments as the largest ones in the anterior and posterior segments respectively.

In the cataract space (the largest part of the anterior segment), intraocular lenses (IOLs) represent c.67% of the total market value. We forecast future market growth in this space to be largely driven by the multifocal (premium) IOL segment.2 Although multifocal IOLs are usually not covered by public pay healthcare systems, nor by statutory health insurance systems, we believe that growth in this sector will be driven an increasing global middle class willing to pay for these products in full (private pay), or in part (co-pay).3

FIGURE TWO

GLOBAL OPHTHALMIC PRODUCT MARKET, SURGERY SPECIFIC

FIGURE THREE

KEY PLAYERS IN THE CATARACT AND VR MARKETS

THE ANTERIOR SEGMENT IS c.10X LARGER THAN THE POSTERIOR SEGMENT, AND FORECAST TO GROW FASTER £BN, 2023F SOURCE

WE

We expect the market for monofocal lenses to grow at around 3.7% globally until 2025. We expect almost all the increase to be driven exclusively by volume growth, since these products are largely commoditised and are experiencing strong downward price pressures.

In the VR space, we expect growth to be driven by surgical pack sales, as well as - to a lesser extent ‒ by disposable instruments (despite being a faster growing segment).

Strong market growth in the sector is supported by solid fundamentals, including:

• An ageing population Age is one of the main drivers of both cataract and VR surgery and, according to data from World Population Prospects, 16% of the world’s population (or 1.55 billion people) will be over age 65 by 2050, up from 9% in 2019 (or 639 million people)4

• Increasing treatment of pathologies and increasing access to healthcare Cataract procedures in China, for instance, are estimated to have doubled in the period between 2014‒2019, from 1.5 million to 3 million procedures.5 Even so, this still means that only c.213 per 100,000 population procedures were carried out, compared to 1,310 in France, 1,049 in Germany,6 or 998 in England (FY22).7 We would expect a significant growth in the number of procedures over time in China and other similarly under-penetrated markets, notably in APAC

• Increasing prevalence of diabetes (mainly related to VR) Diabetes is a significant determinant of VR surgery, and the prevalence of diabetes around the world is expected to rise to 10.2% or 578 million people by 2030 (9.3% or 463 million people in 2019) and 10.9% or 700 million people by 2045. Prevalence rates are higher in urban areas and in high-income countries, meaning we expect to see growth even in currently highly penetrated markets8

• An expanding middle class willing to pay for premium IOLs (related to cataract surgery only) Market Scope forecasts the multifocal IOL market to grow with a CAGR of 11.7% until 2025 (compared to 3.7% for monofocal IOLs)9

In addition to these favourable factors, investments in this space will also benefit from stable revenue streams from public or statutory health insurance payors. We expect this market to remain attractive over the long term.

The cataract equipment space is dominated by large global players, whereas VR has some regional players.

The global market for surgical ophthalmic equipment and products is dominated by Alcon and Bausch + Lomb. These offer a full range of products, from equipment to instruments and consumables, covering both the cataract and VR segments.

Other global players have decided to focus primarily on the anterior segment (for instance Carl Zeiss Meditec and Johnson & Johnson). The larger players are followed by a tail of smaller more regional ones often focusing on IOLs (notably UK-based Rayner and Netherlands-based Ophtec) and consumables.

Players focusing on equipment for the posterior segment tend to be smaller and more regional, for instance DORC, in Western Europe and the USA, Oertli mainly in DACH, and Appasamy Associates in India.

FIGURE FIVE

CASE EXAMPLE ‒ TPG AND BVI SELECTED ACQUISITIONS

SINCE ACQUIRING BVI IN 2016, TPG CAPITAL HAS ROLLED UP MULTIPLE OPHTHALMOLOGY ASSETS

TPG Capital acquire Beaver-Visitec International, Inc. The company focuses on ophthalmic single-use devices in refractive, cataract and retina

BVI acquire Vitreq (Netherlandsbased ophthalmic company focused on minimally-invasive instruments for VR surgery)

BVI acquire Arcadophta (a France-based ophthalmic company specializing in silicon oils, gases and perfluorocarbons used in vitreoretinal surgery)

2020

BVI acquire Malosa Medical (a UK based manufacturer and supplier of single use surgical instruments with more than 400

BVI acquire PhysIOL s.a. (Belgium-based provider of intraocular lenses who in 2017 acquired a majority stake in Optikon (Italian provider of phaco systems, VR devices, and diagnostic equipment)

BVI acquire Benz Research & Development (a US-based manufacturer of contact lenses)

We believe this regionalisation is due to the smaller market size of the VR space compared to the cataract sector; the dominance of Alcon in the US (which until now has limited European player growth in that market); and the low priority historically placed on large Asian markets such as India (India instead is served by local, lower-cost players such as Appasamy).

Though a rough divide between players focusing on the anterior and posterior segments can be made for smaller players, several companies mainly focused on VR (such as BVI, DORC and Oertli) offer either dual-function machines, capable of performing both cataract and VR surgeries, or offer other products that span both segments. We have, therefore, included these in the Cataract and VR segment in Figure Three.

There is significant deal activity and the market for equipment, instruments, disposables and liquids is consolidating.

THERE IS SIGNIFICANT DEAL ACTIVITY AND THE MARKET FOR EQUIPMENT, INSTRUMENTS, DISPOSABLES AND LIQUIDS IS CONSOLIDATING

Deal numbers hit record levels in 2022 (see Figure Four).

There is an identifiable trend for consolidation of equipment providers with other providers of ophthalmic products, such as

consumables. Hence, under TA Associates ownership, Belgium-based IOL manufacturer PhysIOL in 2017 acquired Optikon, an Italian provider of phacoemulsification systems (used in cataract surgery), VR devices, and diagnostic equipment (PhysIOL/Optikon was acquired by BVI the year after).

Further, in 2019, Hoya (Public, TSE/ TYO) acquired Germany-based Fritz Ruck and US-based Mid Labs, providing the company with VR machines, probes, and surgical packs.

The most active investor in recent years has been TPG Capital, which since its 2016 acquisition of BVI, has proceeded to roll-up multiple regional, mainly European, ophthalmology assets into its platform. Targets have included Vitreq (Netherlands), PhysIOL/Optikon (Belgium/Italy), and Arcadophta (France) (see Figure Five).

Through these acquisitions, BVI has significantly expanded its portfolio from being a company primarily focused on single-use devices in refractive, cataract

Disposables

AMD IOL

Retinal Implant

and retina, to one now covering most of the areas covered by its global competitors (see Figure Six).

Because of this significant roll-up, BVI has almost doubled in size since the TPG Capital takeover, growing at an estimated CAGR of around 19% in the years 2017‒2021 to reach revenue of approximately €320m.

The ophthalmology product space is ripe for investment.

Prospective investors will benefit from several attractive market fundamentalssuch as an ageing population, increasing treatment of pathologies and increasing access to healthcare, as well as stable public or insurance funding.

We also see significant roll-up opportunities for investors interested in building ophthalmology platforms focusing on either cataract, VR, or both.

We believe that any platform play should initially focus on the US and

Western Europe where there are more numerous attractive assets. Any play should attempt to leverage the assets’ varying geographical presence to accelerate international expansion.

Once a platform has been established, additional longer-term growth should be achievable through growing the instruments and consumables space, expanding to geographies outside of the US and Western Europe (notably China, India, and the rest of APAC), and encompassing the refractive and glaucoma segments (which we estimate to be worth £4.4bn globally combined in 2023).

NOTES

1 https://www.eurazeo.com/sites/default/ files/presse/190313-DORC-Exclu-EN-1.pdf

2 Multifocal lenses allow for vision at a range of

distances. This contrasts with monofocal lenses which provide focus at only one distance.

3 Co-pay is where the patient pays the difference between the cost of a standard cataract procedure with a monofocal lens, and a premium procedure with a multifocal lens. This is allowed in some countries, though not for instance in the UK.

4 https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/ageing#:~:text=Globally%2C%20the%20population%20aged%2065,11%20in%202019%20 (9%25).

5 Market Scope ‒ 2020 IOL Market Report

Mid-Year Update

6 Eurostat Surgical operations and procedures performed in hospitals: cataract surgery 2019.

7 NHS Digital

8 Saeedi, et. al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition, Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, Volume 157, 2019, 107843, ISSN 0168-8227

9 Market Scope ‒ 2020 IOL Market Report

Mid-Year Update

Spanish and British health services are remarkably similar, but where Spain and the UK differ is the scale and scope of private hospitals. Paul Fegan and Henry Elphick consider the two markets and ask, can we ever expect to see the development of large ‘full service’ private general hospitals in the UK?

In the simple characterisation of health care systems as either ‘Bismarck’ or ‘Beveridge’, the Spanish and British health services are both examples of the latter. Both are largely funded through general taxation; both use primary care gatekeepers to manage access, and both rely to a significant degree on public provision. Sadly, both systems also struggle with waiting lists and a sense of chronic underfunding, and both rely on contracts with private acute hospitals to meet demand. Spain sustains large private hospitals, offering emergency treatment and maternity, whereas the typical UK private hospital is small and focused entirely on elective care.

Private equity is an active investor in both the UK and Spanish hospital markets – for example, in the UK, BC Partners and Centerbridge have owned BMI Circle, and Cinven Spire Healthcare respectively, and in Spain, CVC, BC Partners and Cinven all owned assets that are now part of Quiron Salud. Macquarie Infrastructure and Real Assets currently own Viamed Salud. Each market, whilst similar, has important differences.

Key differences between the private acute markets in Spain and the UK have implications for investment in the sector.

Spain has over 32,700 private acute beds in 295 hospitals. The UK has just over 7,600 beds in 190 hospitals. At an average of just 40 beds, the UK private hospitals are therefore much smaller than the average 111 beds per hospital in Spain, and Spain has more than six times as many private acute beds per million

population as the UK. LaingBuisson estimates that the UK private acute market was worth £5.5bn in 2019 (the last year before the pandemic skews market activity), compared with £7.9bn in Spain.

Moreover, Spain’s private acute hospital sector includes some very significant institutions. For example, Hospital Teknon in Barcelona has 285 beds, 14 intensive care cubicles, 20 operating theatres for high and low complexity procedures, and a 24-hour emergency suite, with resuscitation facilities. In fact, it is ‘normal’ for Spanish private hospitals to have emergency rooms, whereas in the UK, it is unknown. Even in London, only a handful of private hospitals offer urgent care, and none provide an accident and emergency service.

Undoubtedly one of the drivers of this difference is the penetration of voluntary private medical insurance (PMI). In both the UK and Spain, the Beveridge system assures universal coverage (you can’t opt out of paying tax), so PMI is duplicative – that is, it provides an alternative to the national health system, but doesn’t exclude anyone from using it. In Spain, around 25% of the population is covered by PMI, compared with around 11% of the UK population. That translates to around 11.8 million Spaniards and 6.8 million Britons, some 1.7 times as many people covered in Spain than in the UK. At least part of this may be because PMI is cheaper in Spain, but since neither country has community rating or risk equalisation, both markets are structurally similar.

Essentially this implies that, unlike the UK, Spain can justify and sustain large profitable ‘full service’ private general hospitals because it has a critical mass of people with PMI. Yet interestingly, the market for PMI is as skewed as the UK.