More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Music and How it Works The Complete Guide for Kids 1st Edition Dk

https://textbookfull.com/product/music-and-how-it-works-thecomplete-guide-for-kids-1st-edition-dk/

Complete CompTIA A Guide to IT Hardware and Software 7th Edition Cheryl A. Schmidt

https://textbookfull.com/product/complete-comptia-a-guide-to-ithardware-and-software-7th-edition-cheryl-a-schmidt/

Margin Trading from A to Z A Complete Guide to Borrowing Investing and Regulation 1st Edition Curley

Michael T

https://textbookfull.com/product/margin-trading-from-a-to-z-acomplete-guide-to-borrowing-investing-and-regulation-1st-editioncurley-michael-t/

Leading healthcare IT: managing to succeed 1st Edition

Susan T. Snedaker

https://textbookfull.com/product/leading-healthcare-it-managingto-succeed-1st-edition-susan-t-snedaker/

Wouldn t it be nice Brian Wilson and the making of the Beach Boys Pet sounds Beach Boys.

https://textbookfull.com/product/wouldn-t-it-be-nice-brianwilson-and-the-making-of-the-beach-boys-pet-sounds-beach-boys/

Malawi Culture Smart The Essential Guide to Customs Culture 1st Edition Kondwani Bell Munthali

https://textbookfull.com/product/malawi-culture-smart-theessential-guide-to-customs-culture-1st-edition-kondwani-bellmunthali/

The Complete Guide to Male Fertility Preservation 1st Edition Ahmad Majzoub

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-complete-guide-to-malefertility-preservation-1st-edition-ahmad-majzoub/

The Complete Guide to Personal Training 2nd Edition Couson

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-complete-guide-to-personaltraining-2nd-edition-couson/

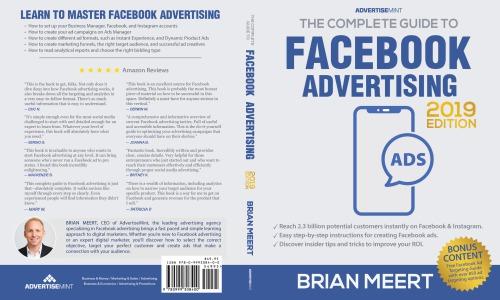

The Complete Guide to Facebook Advertising Brian Meert

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-complete-guide-to-facebookadvertising-brian-meert/

Copyright © 2016 by Mary T. Bell

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo credit: iStockphoto

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-1182-2

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-1183-9

Printed in China

Contents

Dedication

ForewordbyMonteB.Carlson

Introduction

Chapter 1: What Is It?

Chapter 2: Equipment

Chapter 3: Jerky Business: The Commercial Side

Chapter 4: Making It!

Chapter 5: Making Strip Jerky

Chapter 6: Making Ground Meat Jerky

Chapter 7: Using Jerky

Appendix:JerkyPetTreats

MetricConversionCharts

PhotoCredits

To all grandkids, including ours: Hunter, Alysse, Oliver, and Wesley.

May this collection encourage all of you to embrace the ways of our ancestors and be thoughtful, responsible stewards of our earth.

MForeword

A JERKY JUDGE

aking jerky is my hobby. It’s my diversion from the courtroom. I find it satisfying and fulfilling to take a hunk of raw meat and make it tasty. Some of us make jerky because we’re hunters. Not only do we want to consume what we kill, but we also prefer venison jerky to venison chops. For over thirty years, I’ve bow hunted deer and elk with the same loony partners and together we turned a zillion deer and twenty-three elk into jerky. With that kind of tasting experience, I think it’s fair to say I’ve become a pretty good judge of jerky.

Jerky has become a tradition in our family. While we were students with limited income, my wife and I practically lived on wild game. Then, as well as now, she prefers her big game meat made into jerky. For three and a half decades, we’ve been making jerky in a food dryer and more recently we’ve used a smoker. Ever notice that “he who controls food, is king”? Several years ago, I had to convince my nephew, who was doing nothing other

than waiting for college to begin, to backpack with me into Idaho’s mountain country for an archery elk hunt. This non-hunting six-footseven-inch lad from Kentucky became my pack mule, carried all my heavy camping equipment, and all he required was a slice of jerky every now and then. Like a trained seal being fed a fish, my nephew actually packed out my bull elk, with no reward other than a constant (but obscene) amount of jerky.

Some say that jerky makers are just a little off the plumb line. I make jerky for my odd assortment of wacko hunting pals, but I charge them one-third of the result—my ambulance chasing days die slowly. Once, while practicing law, I drove to Eastern Idaho to meet with a client in his home. The whole house was filled with smoke. Up above me, hanging from the rafters, were strips of raw meat. This guy had killed a deer and right there in his living room was making jerky.

Like most jerky makers, I always look forward to trying new recipes and tinkering with exotic flavor combinations. Mary Bell’s earlier book JustJerkybecame my jerky maker’s bible. Not only did she teach the art of drying hamburger (which, by the way, works perfectly well with ground sausage and ground turkey), she explained how to make traditional and even unusual tasting jerkies. Mary encourages her readers to be creative and blend unusual flavors. No book on the market is better. Mary fields more questions, solves more problems, and delivers better information than anyone else in the crowded jerky theater. I know—I’ve appealed to her wisdom more than once. Her book is filled with great stories, more recipes for us addicts, and it’s flavored throughout with good advice.

Jerky people are a goofy bunch that actually enjoy making jerky in their attics, basements, kitchens, living rooms, or garages—with or without food dryers, smokers, or ovens—and they even use such dangerous chemicals as liquid smoke. Jerky people experiment by smoking, marinating, grinding, drying, salting, and flavoring all kinds of meat. (I’ve made antelope and cougar jerky.) People keep searching for that one great bite of jerky that has the perfect flavor. I am personally grateful to all of those who shared their recipes, wisdom, and advice.

—Hon. Monte B. Carlson, Fifty Judicial District, Burley, Idaho

Introduction

True confession—I was once a vegetarian. In the early 1970s, I decided vegetarianism was a gentler, cheaper way for our family of three to live. We had been vegetarians about a year when my son, Eric, shouted out from the backseat of the car, “Mom I don’t care if you’re a vegetarian, I want a hamburger.” I heard him loud and clear and drove to the nearest burger joint.

This was at the time I was putting myself through college and trying to provide good food for my two kids, Sally and Eric. We had planted a large garden and I was experimenting with various methods of preserving food. Once Eric let me know he wanted meat in our diet, I knew I had to develop the skill to bag my own and joined an archery league. One night, my archery friends brought a deer over and we butchered it at my kitchen table. I quickly learned how to cook venison and began making jerky.

As my passion for food drying grew, I sold food dehydrators at home and garden shows, fairs and sport shows. I promoted food drying in North and Central America and wrote Dehydration Made Simple,MaryBell’sCompleteDehydratorCookbook,JustJerky, Jerky People, and Food Drying with an Attitude. I still teach classes and talk about food drying to just about anybody who’ll listen. Throughout the years, the more I learned, the more my curiosity was fueled.

In my travels, people often asked a lot of questions about how to make jerky. Is it hard? How can you tell when it’s dry? What’s the best marinade? Is it safe to make yourself? I learned that many people have purchased a food dehydrator just to make jerky.

If you buy a lot of jerky, if you hunt, fish, hike, or if you’re just looking for a healthy low-fat snack, or you’re one of those people who just took a new dehydrator out of the box and it’s sitting on the kitchen counter and your kid is yelling “Dad, jerky, please!” then this book is for you.

This book is more than just instructions and recipes—it represents a community of people. Throughout these pages, you’ll find people who like jerky and were willing to share their wisdom and experiences. Granted, they’re all characters who like to either hunt, fish, ride horseback, canoe, sail, backpack, run a ranch, or are involved in some sort of a jerky business. “What’s your story?” I’d ask them. “How did you get started making jerky? What’s unique or different about how you make it?” Their answers were both fascinating and useful. Others wrote, telephoned, emailed, or connected with me through my website. “I have this really great jerky recipe,” they’d say and I’d quickly jot it down. These innovative

and inventive sages gave good advice and sound instructions along with some pretty terrific recipes.

You will find information on how to make jerky out of meat, fish, and poultry strips and with various ground meats. I’ve addressed safety concerns, as well. For a broader understanding, I included bits of history and stories from the commercial end of the jerky business. Then, hold on to your taste buds, there are some really terrific jerky marinades, along with delicious and fun recipes to use jerky in cooking and baking. There are recipes for stew, bread, cake, frosting, and even ice cream. I’ve spent years collecting recipes, suggestions, tips, techniques, and ideas from a variety of sources and have dried jerky in dehydrators, smokers, woodstoves, campfires, and in various ovens.

It has been a long time since my son shouted for a burger from the backseat and, through all of these years, my determination to be self-sufficient turned into a life philosophy. Food represents our most intimate link and essential connection to the land. It’s our source of health and vitality, the centerpiece of family, ethnic, and community traditions. Food reflects who we are and what we value. I believe the more we assume responsibility for our food supply and reduce our dependence on the food industry, the more we lessen our impact on this planet. Taking food from the land around us and preserving it provides us with a thoughtful alternative. Making jerky is intrinsic to this approach.

—Mary Bell

The author with her dehydrator.

Our grandson Hunter Evans Gehrke was three days old when his mom and dad bundled him up, secured him in his car seat, and headed off to our place for Aunt Sal’s wedding. Less than a mile from our home, a deer rammed their car. After we were all assured that no one was hurt, except the deer, and we’d assessed the damage to the car, we looked intently at this brand new little man and commented that on his first outing he already bagged a deer.

MY TAKE ON FOOD STORAGE

“It’s a Good Idea!”

Throughout the years, many people have asked what I think about developing a food storage program. I believe that storing food is a good idea because it has always been and will always be a good idea. Our grandparents, many of our parents, rich or poor, regardless of where they lived, thought ahead to what they’d eat next week, next month, and even next year. Long-sightedness and survival were synonymous. Food storage was commonplace and expected. I believe that if each one of us looks back into our genetic pasts, we will find that our ancestors, regardless of where they lived, turned to jerky as a welcomed food.

If there is ever a time where our food supply, for one reason or another, has become limited, I think that having a full panty can relieve one from getting caught by fear and instead be able to embrace generosity.

KNOW THIS I am grateful for all of the wonderful people who contributed their jerky recipes and stories. I am hopeful that this collection will serve as a tribute to each one. Knowing that a recipe can be a coveted treasurer, I was delighted at how many people were willing to share. Businesses, of course, were not as disclosing with their recipes, but willingly gave tips, suggestions, and insights into their jerky world. This new, combined, and revised edition is a

combination of Just Jerky and Jerky People. And I am sorry to say that some of these friends are now smiling down from jerky heaven.

Many of these jerky marinades were first taste-tested by the staff of L’Etoile, a restaurant in Madison, Wisconsin, under the guidance of Chef Gene Gowan. I really got lucky when I started buying grass-fed beef from our neighbors, Leslea and Brad Hodgson, owners of Galloway Beef. Not only did they provide most of the beef used to finesse these recipes, but Leslea also deserves credit for creating many of the jerky recipes. As lovers of their herd, the land, and being true jerky fans, Leslea used her knowledge to honor her cattle’s ultimate gift.

Joe Deden, the author’s husband.

My husband, Joe, is a great guy with a good heart. As these recipes were tested and re-tested, he kept repeating how he was the lucky one who was constantly being offered another jerky to taste-test. I am also grateful to my dear friend Ray Howe, who, at every stage, willingly gave me support and encouragement to tackle this endeavor.

What I’ve learned about making jerky and drying food is that not only is it a way to preserve food, but it is a language. I have witnessed how it serves as a bridge and connects people to their pasts, regardless of the color of their skin or place of origin. If you stop and think, somewhere back, each one of our ancestors knew the blessings of having access to dried food.

Jerky taste-testing.

CHAPTER 1

What Is It?

J

erky has many meanings. As a verb, it relates to movement. To twitch is to jerk. A quick pull, twist, push, thrust, or throw is a jerk. An unexpected muscular contraction caused by a reflex action is a jerk. Convulsive or spasmodic movements and sudden starts and stops are known as jerks. Speech isn’t without its jerks. To utter anything with sharp gasps is to jerk out.

Jerkin sounds like slang, but in the sixteenth century, it was an article of clothing—a short, close-fitting, often sleeveless coat or jacket. In more recent times, a jerkin became a short, sleeveless vest worn by women. A jerkin is also a type of hawk, the male gyrfalcon.

The noun jerker has two meanings: one is a British customs agent who searches vessels for unentered goods. One who, or that which, jerks is also known as a jerker.

My favorite movie is The Jerk, starring Steve Martin. However, a real jerk, the kind we’ve all encountered, is a person regarded as stupid, dull, maybe eccentric. Jerks—and jerkers, for that matter— can come from jerkwater towns.

Jerky is most commonly known as meat preserved by slicing it into strips and drying it in the sun, over a fire, or in a dehydrator, smoker, or oven. It’s called charqui, pronounced “sharkey” in Spanish. In Africa, jerky is referred to as biltongand is generally quite thick and made with ostrich, python, and impala—in other words, any available red meat protein. In Central and South America, this portable ancient food was called tasajo. Eventually dried meat became known as jerkyor jerkedbeef. Caribbean cooks popularized a style of cooking that typically calls for a marinade laced with allspice, and that too is jerky.

For more inspiration, sing “Come On, Do the Jerk!” by the Miracles, or “Cool Jerk” by the Capitols, or “The Jerk” by the Larks. Then there’s “Can You Jerk Like Me” by the Contours and Rodney Crowell’s tell-it-like-it-is ballad “She Loves the Jerk.”

REAL JERKY

Making jerky can be as simple as sprinkling salt and pepper onto meat, fish, or poultry strips and drying them over a smoky fire. Although that’s a valid way to make jerky, this book will introduce you to a bolder dimension of flavor blending. Jerky can be like fine wine, a mingling of characteristics, some subtle, others robust.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Prognosis. The prognosis varies, according to the determining cause. In cases of accident and in temporary agalaxia, it is sufficient to change the food in order to restore the secretion. Cooked food and warm drinks, with an allowance of roots such as turnips or mangolds, have excellent results. Where restoration of the secretion is delayed the use of what are called galactogogues has been recommended, comprising fennel, carraway, cummin, aniseed, juniper, sulphur, etc., mixed in equal parts and given in doses of 6 to 8 drachms per day for a cow.

They act principally through the stimulating effects of their aromatic principles.

MICROBIC CHANGES IN MILK.

LACTIC FERMENTS.

Microbic changes in milk are much commoner than changes of a chemical nature. Milch animals differ very markedly one from another, and, according to circumstances, give milk of ordinary composition, milk of a very rich character, or watery milk; but the most important changes in composition are those due to microbic agents.

During the milking, and according to whether this is performed in a low, dirty byre, in a clean, roomy byre, or in the open air, various numbers of germs obtain entrance to the milking vessels, and develop there with extraordinary rapidity. The milk may even become infected by non-pathogenic germs while still within the udder, in the sinus and galactophorous canals. The cleanliness of the milking vessels also has a considerable influence on the number and variety of the microbes which may eventually germinate in the liquid.

Among the microorganisms usually found in milk there are some, however, which always preponderate and play the part of organised ferments, viz., the lactic ferments and the organisms which cause coagulation of the casein; these may be regarded as normal constituents. The others are more or less foreign, and may cause important changes in the milk or cream.

The lactic ferments are numerous, comprising the lactic bacilli of Hueppe and Grotenfeld, the micrococci of Hueppe and Marpmann, and the bacilli and micrococci of Freudenreich. These different agents act on the lactose of the milk, decomposing it into carbonic and lactic acids, which coagulate the milk.

Another group of microorganisms which were well studied by Duclaux comprises those acting on the casein, among others Tyrothrix tenuis, filiformis, turgidus, scaber, virgula, etc.

These organisms secrete principles having similar effects to those of rennet, and are capable of coagulating enormous quantities of milk. After a certain time, they also secrete a second diastase, viz., casease, which acts in the ripening of cheese.

Clotted Milk.—This term is used in dairies to indicate milk which coagulates in lumps immediately after being withdrawn from the udder, or which coagulates spontaneously a few hours later.

The change may be of a chemical nature, depending on conditions of keep or feeding. More frequently, however, it is related to a latent non-pathogenic infection of the udder, or to immediate infection of the milk after removal by lactic ferments contained in the milk vessels or the atmosphere.

It is necessary, according to circumstances, either to modify the diet or disinfect the milk vessels, and immediately pasteurise the milk.

Milk without Butter.—Less commonly the diseased condition is indicated by marked diminution in the quantity of cream.

Churning only produces a poor kind of butter, particles of which do not readily cohere. This peculiarity is due to the presence of microorganisms, which have not yet been fully identified. It can be prevented by disinfection of the milking vessels, as well as of the dairy itself, and by the use of centrifugal separators.

Putrid Milk.—This milk is characterised by its odour. It cannot be used for making butter. In fact, as soon as the cream separates, little bubbles of gas form at various points and break, leaving small cavities. These little separate cavities reunite very rapidly, and the cream becomes reabsorbed as fast as it is formed. Afterwards oily drops formed of butyric, capric, and caprylic acids appear in the depressions and give the milk a repulsive odour (rancidity).

This change is seen during mammitis, but most commonly results from uncleanliness in byres and dairies. In the latter case putrefaction occurs about twenty-four hours after milking, and is due to the growth in the milk of Bacterium termo, lineola, etc. These organisms are present in the dust which falls into the milking pails in the byre; when milk so contaminated is stored in the dairy the changes occur.

Putrid odour may also be due to the presence of ammoniacal gas in the byre, or to special toxins liberated by microbes which have found their way into the milk. It is most marked during the warm seasons of the year.

The occurrence of putrid milk can be prevented by disinfecting the dairy and the milking pails daily for a certain time.

Mucous, viscous, or thready Milk.—These terms are applied to a condition which usually appears twenty-four or thirty-six hours after the milk has been withdrawn. The milk seems thick and viscous, and can be drawn out into threads like mucus. It sticks to neighbouring objects, and adheres to milk vessels like molasses. It coagulates imperfectly on standing, gives little cream, and even this cream only furnishes a mawkish, ill-flavoured butter.

In certain parts of Switzerland the production of mucous milk is favoured, because it is employed in making cheeses.

The change is due to the presence of various microorganisms. Those which have been best studied are Schmidt-Mülheim’s micrococci, the Actinobacter polymorphus of Duclaux, the Bacillus lactis pituitosi of Löffler, the Bacillus lactis of Adametz, the Streptococcus hollandicus, and, finally, three others which are much commoner, Guillebeau’s bacillus, the Micrococcus Freudenreichii, and the Bacterium Hessii. These microorganisms act on the lactose, decomposing it and causing the formation of a kind of filamentous mucilage, which can be isolated by the addition of alcohol.

The mucilaginous change in milk can be prevented by ordinary methods of disinfection.

Red Milk.—Milk which becomes red some hours after withdrawal, or within forty-eight hours after milking, should be distinguished from milk which on withdrawal from the udder is tinted red in consequence of hæmorrhage within the udder itself.

When the milk is of a hæmorrhagic tint the blood corpuscles are soon deposited on the bottom of the vessel if the milk is allowed to remain undisturbed.

The tint which the milk assumes is due to the growth of chromogenic organisms, the best known of which are as follows:—1. B. prodigiosus, which produces large red patches on the surface. It grows readily on potato and gelatine, which it liquefies. 2. The Sarcina rosea, which develops first of all in the cream and afterwards invades the milk. It grows in sterilised milk, on alkaline potato, and on gelatine. 3. The Bacterium lactis erythrogenes, which liquefies gelatine and produces a reddish coloration. Casein can be precipitated and peptonised by means of its cultures. It develops in the milk below the cream, the serum alone becoming red, and only when shaded from the light.

Blue Milk.—In this case the milk appears normal when withdrawn, but some days afterwards shows blue patches, which gradually increase in size, and by uniting produce a distinct blue tint at the surface.

This change is connected with the presence of the B. cyanogenus. The organism grows in sterilised milk, but in this case merely produces greyish patches, the blue tint only occurring when a certain quantity of lactic acid is added or when the ordinary lactic ferments are present.

Yellow Milk.—A yellow tint occurs in ordinary milk and cream, particularly in certain breeding districts—in Normandy, for example, where the butter produced is greatly valued on account of this appearance. Pathological yellow milk is the result of the growth of B. synxanthus Schröter, which secretes a substance resembling rennet, curdles the milk, and finally dissolves the clot, at the same time producing the yellow colour.

Bitter Milk.—Milk which is of a normal character on being withdrawn from the udder may acquire a bitter taste some hours later. At rest, this milk produces a small quantity of yellowish, frothy cream. The organisms which produce the change have been studied in Germany, Switzerland, and Auvergne. We may mention Weizmann’s bacillus of bitter milk, Conn’s micrococcus of bitter milk, and Duclaux’s Tyrothrix geniculatus.

Medicated Milk.—Medicated milk may be divided into two kinds: Firstly, medicated milk proper, which differs from normal milk inasmuch as it contains a certain proportion of drugs, which, when swallowed by milch cows are partly eliminated through the udder. When taken by a young animal or child such milk has a distinct therapeutic effect, depending on the principles employed.

It does not appear, however, that up to the present any very great success has followed this system. It is possible to increase the richness of the milk in phosphates, but as regards mercurial or iodine preparations the failure has been complete.

Secondly, fermented milks, which in addition to their nutritive action are made more digestible.

Fermented milk is easily digested, and is better borne by the weakest stomachs.

In human practice the fermented forms of milk are two, viz., kephyr and koumiss.

Kephyr is prepared in Afghanistan and Persia from camel’s milk, but for some years past it has been made in England with cow’s milk. A certain quantity of cow’s milk is placed in a bottle and the ferment, consisting of kephyr grains, is added. The lactose is converted into carbonic acid and alcohol in consequence of the action of certain lactic microbes.

This milk after ingestion does not require to be coagulated and then digested before absorption, a fact which considerably diminishes peptic digestion.

Koumiss is a milk preparation resembling kephyr; it is made by the Kirghizes with mare’s milk according to the same principles, but the ferment employed gives more alcohol.

Preservation of Milk.—On account of the importance of preserving milk for use in large towns, in hospitals, and in the army during war, the question of its preservation has long been studied.

Chemical Processes.—The principle of preserving milk by chemical action consists in preventing, or at least retarding, the changes which inevitably follow exposure to the air. For this purpose, chemical substitutes are added which in themselves have no injurious action. Those most commonly employed are:—

Carbonate of soda

45 grs. per quart.

Bicarbonate of soda 45 grs. „

Boric acid 15 to 30 grs. „

Salicylic acid

Borax

12 grs. „

60 grs. „

Lime 20 grs. „

The results obtained are of comparatively little value; the milk only keeps for a few hours, or at the most for three or four days.

Cold.—Refrigeration, which is so valuable in preserving all kinds of animal products for long periods, has also been used for preserving milk. Unfortunately, although cold impedes the development of bacteria, it also has the grave inconvenience of causing the cream to separate from the milk, and it being impossible to mix them again satisfactorily, milk preserved in this way is more or less unfit for consumption.

Heat.—The principle of preserving milk by heat is based on the destruction of the microorganisms at a high temperature. In this respect again, one meets with obstacles, for, if the heat be applied direct, some of the principles of the milk are converted into caramel, and if the temperature rises beyond 157° Fahr. (70° C.) the composition of the milk is changed.

Preservation by Oxygen.—Within the last few years the use of oxygen at a pressure of about two atmospheres has been recommended. When the milk is to be used it is only necessary slightly to relieve the pressure and allow the oxygen to escape, the liquor which remains having all the characters and qualities of fresh milk. The method appears excellent, but is too costly for every-day use.

Pasteurisation.—The pasteurisation of milk aims at destroying the greater proportion of the ferments above mentioned. The milk is heated at atmospheric pressure, and is kept for a time at a temperature of between 150° and 157° Fahr. (65° and 70° C.). It preserves its properties and composition, but sterilisation is not complete, and the milk cannot be kept indefinitely.

Concentrated Milk.—Concentrated milk is obtained by prolonged heating to 157° Fahr. (70° C.) in a vacuum, when it becomes syrupy by evaporation and its composition is not greatly modified. It is then drawn off into bottles, which are hermetically sealed and subjected to a higher temperature to complete the destruction of all the germs. Condensed milk keeps for a very long time. To prepare it for use it is mixed with a certain quantity of water, and then yields a liquid similar to normal milk.

Sterilisation.—Sterilisation necessitates the use of special apparatus in which the milk is heated in a water or steam bath sheltered from the action of the air, the temperature rising to 212° to 240° Fahr. (100° to 115° C.); all the ferments are destroyed, and the milk will keep indefinitely, but its composition is slightly modified.

Diseases

Transmissible to Man through the Medium of Milk.

Tuberculosis.—The history of tuberculosis contains numerous facts proving the possibility of contagion by milk from cows suffering from tuberculous mammitis, though it seems necessary that the milk should be taken for a certain time to produce these effects.

Foot-and-Mouth Disease.—Observations recorded by veterinary surgeons prove that this disease affects the teats. It may be transmitted to man. The milker may be directly inoculated, but the milk is the ordinary vehicle of contagion. Chauveau saw an epidemic in a school at Lyons where milk was obtained from cows suffering from foot-and-mouth disease. In a similar way 205 persons were inoculated at Dover in 1884, and suffered from vesicles about the mouth.

Although foot-and-mouth disease is extremely benign in men, it is well to take every precaution against it.

Gastro-Intestinal Infections.—Cases have been recorded of gastrointestinal infection in young animals and children in consequence of consuming milk which had undergone abnormal changes. Milk containing various kinds of microorganisms may at first produce lactic indigestion and afterwards diarrhœic enteritis.