Violin 1

Linda Lin

Concertmaster

Jones-Saathoff Family Endowed Chair

Maja Maklakiewicz

Associate Concertmaster

Diekemper Family Foundation Endowed Chair

Abi Rhoades

Grace MarÍn Aguilar

Radman Rasti

Violin 2

Saikat Karmakar

Principal

Justice Phil and Carla Johnson Endowed Chair

Cassidy Forehand

Adan Flores

Shawn Earthman

Savannah Sharp

Viola

Gwendolyn Matias-Ryan Principal

Mary M. Epps and Ralph E.

Wallingford Endowed Chair

Israel Mello

Sharon Mirll

Ryellen Joaquim

Vivian McDermott

Cello

Michael Newton

Principal

Mary Francis Carter

Endowed Chair

Danny Mar

Madeline Garcia

Daria Miśkiewicz

Double Bass

Mark Morton Principal

Eugene and Covar Dabezies

Endowed Chair

Stuart Anderson

Flute

Kim Hudson

Principal

Crew of Columbia, STS-107

Endowed Chair

Antonio Herbert Piccolo

Antonio Herbert Oboe

Kathleen Bell

Principal

Lubbock Symphony Guild Endowed Chair

Jordan Hastings

English horn

Jordan Hastings

Janeen Drew Holmes English

Horn Endowed Chair

David Shea

Principal

Christine Polvado and

John Stockdale Endowed Chair

Mia Zamora

Basset horn

Aron Maczak

Hamed Shadad

Bassoon

Vince Ocampo

Principal

Nancy and Tom Neal Endowed Chair

Adam Drake

Horn

Quentin Fisher Principal

Anthony and Helen Brittin Endowed Chair

Esteban Chavez

Clark Hutchinson

David Lewis

Jack Mellinger

Trumpet

Gary Hudson

Principal

Stacey and Robert Kollman

Family Endowed Chair

Nathalie Mejia-Zec

Lisa Rogers

Principal

Lubbock Symphony Guild Endowed Chair

Percussion

Kyle Buentello

Lisa Rogers/Alan Shinn Endowed Chair

Sarek Gutierrez

Anthony Flores

Harp

Jennifer Miller

Principal

Rachel Jean

Armstrong Thomas Endowed Chair

Personnel Manager

Gary Hudson

Librarian

Israel Mello

Serenade No. 10 in B-flat major, K.361

“Gran Partita” W. A. Mozart (1756-1791)

Largo – Molto allegro

Adagio Menuetto Tema con Variazioni Finale

Symphony No. 96 in D major, Hob. I : 96

“The Miracle” Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Adagio – Allegro Andante Menuet – Trio Finale

Petite Suite Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

En Bateau Cortege Menuet Ballet orch. Henri BÜsser

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Serenade No. 10 in B-flat major, K. 361, “Gran Partita”

The word serenade evokes visions of an ardent young swain crooning beneath a rosetrestled balcony to the object of his affection listening attentively above. The warbling lover might accompany himself on lute or guitar under a shining moon on a warm summer night, with or without a backup instrumental group. From the eighteenth century onwards, the word “serenade” came to be associated with purely instrumental music, though the serenade with voice remained a cultural reference for many composers. In the twentieth century, composers as diverse as Arnold Schoenberg and Ralph Vaughan Williams wrote works with the title “serenade” that are akin to its more conventional meaning.

In the latter half of the eighteenth century, serenade denoted a multi-movement work for an instrumental ensemble. These works were light entertainment music – something to be played as dinner music, or for some special occasion such as a wedding or the birthday of a patron. They sometimes bore the title divertimento, promising music that would pleasantly divert and entertain. Divertimenti and serenades had at least three movements in the manner of a concerto or symphony, but often had as many as nine or ten. The ensemble could be small, such as a string trio or quartet (Mozart’s famous Eine Kleine Nachtmusik, K. 525, is a serenade for string quintet), but a serenade/divertimento could also be written for a full orchestra or a woodwind group.

Often the instrumentation of a serenade suggests a possible venue for the occasion. In general, serenades employing strings would be performed indoors in the more intimate parlors and drawing rooms of the time. Outdoor serenades were more likely to be scored for larger wind groups, since their louder and more penetrating tone would carry farther in the formal gardens and well-groomed lawns of 18th-century palaces.

More than 30 of Mozart’s serenades and divertimenti have survived to our time. For music that was intended to be heard once and then forgotten, it is notable that these works were copied and preserved. While some of them are of the “throwaway” variety, a number of these works transcend the bounds of light entertainment music and are notable for their beauty and profundity. We know that some of this is the result of the friendship that Mozart developed with particular patrons and their families. The “Haffner” serenade, K. 250, is written for a symphony orchestra and lasts about 40 minutes – longer than any Mozart symphony. Written for the wedding of Marie Elisabeth Haffner, it is a work that is both entertaining and profound. In all likelihood, Mozart wished to present his best work to honor his friend Sigmund Haffner and his family.

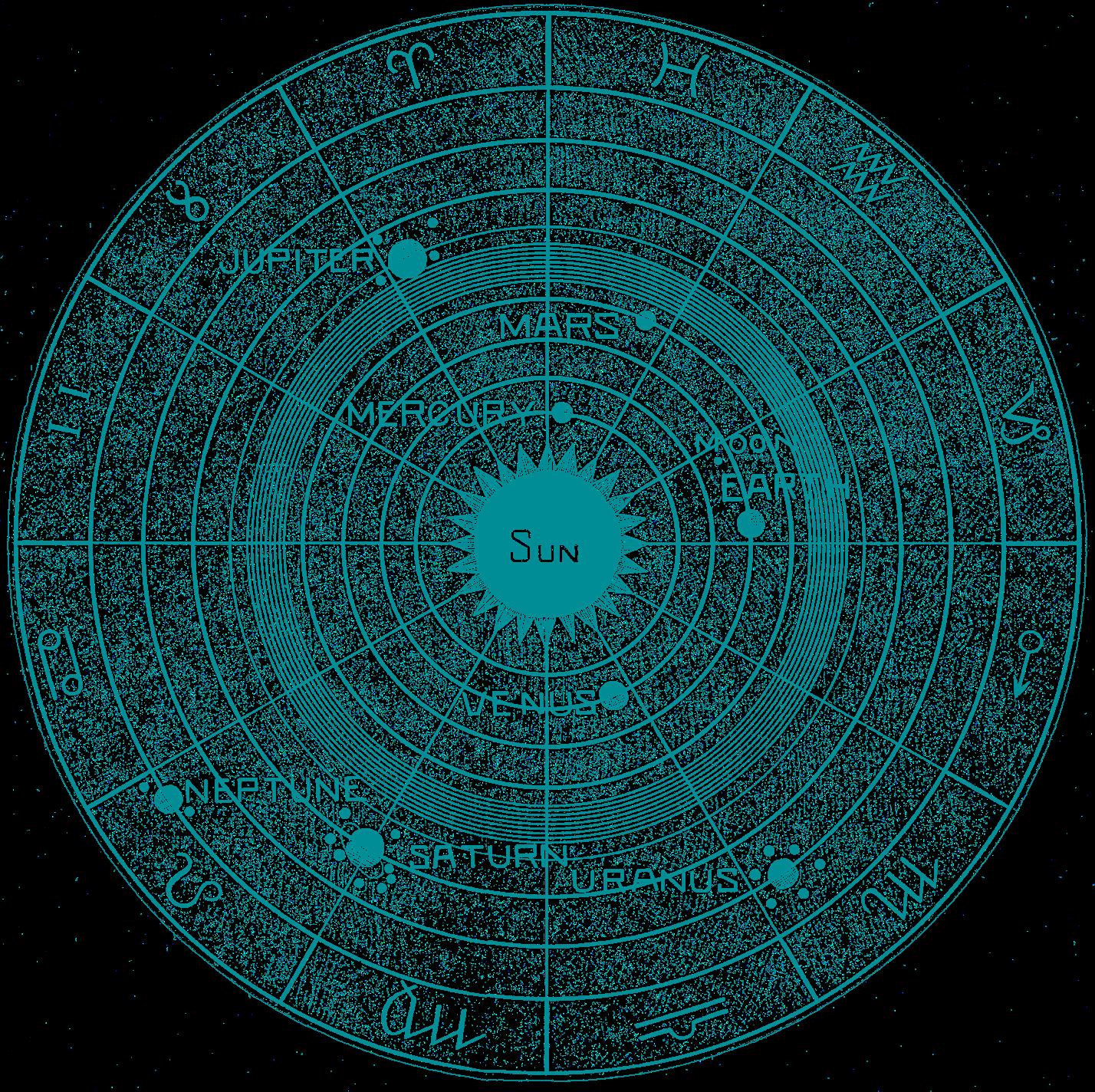

Among Mozart’s serenades, the three works for Harmoniemusik (wind band) come from his early years in Vienna (1781 – 1784). While it is tempting to ascribe them to the Viennese fad for wind band music that began in the 1780s, at least two of the three works predate the establishment of the Imperial Royal Harmonie by Emperor Joseph II. The Emperor’s wind ensemble consisted of pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons and horns and served as the template for other Viennese wind groups. Mozart’s briefer works in this genre (the Serenades in E-flat and C minor) conform to this instrumentation. The Gran Partita, however, is scored for the luxurious combination of two oboes, two clarinets, two basset horns, two bassoons, and four horns, with the addition of either a contrabassoon or double bass. It is the longest of Mozart’s works for winds and longer than any of his symphonies; the music is more symphonic than it is diverting, with a richness of texture and profundity of expression found in Mozart’s symphonies, concertos and operas.

The origins of the Gran Partita are shrouded in mystery. It dates from either 1780 or 1781, and the grand occasion for which Mozart wrote it is unknown; it is quite possible that the event was canceled. The title, too, is enigmatic – it is unlikely that Mozart gave it that name, and it is written on the manuscript in a hand that is not the composer’s. The idea that he wrote it as a wedding present for his wife Constanze has been safely debunked and we know that it substantially predates the only public performance in Mozart’s lifetime, a benefit concert for clarinetist Anton Stadler. Only four movements of

the work were performed on that occasion, so it is unlikely that concert was the première performance. It may be possible that Mozart had written it as a musical “resumé,” much like J.S. Bach’s B minor Mass – a work he could send to prospective employers to demonstrate his abilities in writing for a wind group.

The work is in seven movements. The stately Largo opens with majestic fanfares from the full ensemble, answered by the clarinet and the oboe. It ushers in an Allegro molto that employs very concise amounts of musical material, beginning with an insouciant four-note figure. Both minuets (movements 2 and 4) are five-part minuets with two trios; contrast is provided by one trio being in a minor key in each movement. The Adagio could be an instrumental version of one of Mozart’s opera ensembles, with oboe, clarinet and basset horn singing their heartfelt melismas over a serene accompaniment. The fifth movement Romanze is a companion to the third movement Adagio, but the serenity is here interrupted by a central C minor section (Allegro) where the clarinets and then the entire ensemble over a nervous staccato accompaniment in the bassoons. The Theme and Variations is an adaptation of music Mozart wrote for his Flute Quartet in C major, K. 285b. It presents a theme in the solo clarinet which is perky and lyrical by turns, which is answered by the entire ensemble. The theme develops through six variations, with the fifth an Adagio and the final variation an Allegretto. The final Rondo is the one movement of the work that can truly said to be in “serenade style.” It bubbles along in irrepressible high spirits, with many witty interchanges between all the instruments. Mozart teases us on how he’ll conclude the work; brief cadential fanfares suddenly dissipate into slithery chromatic lines. Mozart finishes his little joke, and a final rapid buildup in the woodwinds leads to fanfares that end the work in joyous celebration.

Franz Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 96 in D major, Hob. 1 : 96, “The Miracle”

Franz Joseph Haydn’s 30-year career with the Esterházy family proved to be a fruitful relationship for both musician and monarch. It is true that Haydn was treated as a servant – his contract specified that he and his musicians “appear in white stockings and white shirt, with either pigtail or tiewig, and thoroughly powered” – but his patrons, Prince Paul von Esterházy and his successor Prince Nikolaus, provided Haydn with all the resources he could want in order to make the Esterházy musical establishment one of the most renowned in all of Europe. Since Haydn had only one fairly liberal patron to please, without the need to entertain a fickle public, he could experiment to his heart’s content. In so doing, he forged the modern forms of both the symphony and string quartet. Haydn wrote of his time at Esterházy: ”I was cut off from the world. There was no one to confuse or torment me, and I was forced to become original.”

When Prince Nikolaus died in September 1790, Haydn’s sheltered creative life came to an end. Nikolaus’s successor, Prince Anton, severely cut the musical staff at his court. Rumors about these draconian measures have proliferated like modern conspiracy theories. Some have suggested that Prince Anton’s wife, Maria Theresa, greatly preferred clothing, jewelry, and furnishings to music. The most likely explanation appears to be that the newly elevated Prince had a spending problem, and the estate was put in the hands of a financial regulator, who reduced the Esterházy music establishment to a small wind band and a few singers for the family’s weekly devotions. Haydn and his concertmaster, Luigi Tommasini, were kept on but with reduced duties and diminished wages. Most of the musicians were given six weeks’ severance pay, and Haydn was given a pension, with almost no demands on him for new compositions. With over 90 symphonies to his credit along with numerous other works in all genres, no one could blame Haydn for contemplating a quiet (if austere) retirement at the age of 58.

Fortunately for Haydn and the history of music, fate had other plans. Shortly after the downsizing of his position, Haydn’s dull domesticity was shattered by the appearance of one Johann Peter Salomon, a violinist, composer and conductor who had made a very successful career as a concert impresario in London. Salomon made the journey from London to Vienna to entice Haydn to return with him to write music, give concerts – and make obscene piles of money. According to Haydn’s first biographer, Albert Christoph Dies, Salomon’s first words to Haydn were ”I am Salomon of London and I have come to fetch you; tomorrow we will establish an agreement.” While Haydn was initially skeptical and slightly apprehensive of undertaking such a long journey at his age, the lure both

of a new audience and much-needed financial security proved irresistible. With the contractual promise of 5000 Austrian gulden (roughly $65,000 in today’s currency) in hand, Haydn landed in Britain on New Year’s Day, 1791 after a two-week journey across Europe.

Salomon was as good as his word. Within days of setting foot in England, Haydn wrote “My arrival caused a sensation throughout the city and I went the round of all the newspapers for three successive days. It appears that everybody wants to know me.” His concerts were considered the most important events of the society season, playing to sold-out houses on almost every occasion. The musicologist and critic Charles Burney attended Haydn’s first concert in London and reported the sensation it caused:

“Haydn himself presided at the piano-forte; and the sight of that renowned composer so electrified the audience, as to excite an attention and a pleasure superior to any that had ever been caused by instrumental music in England.” He was awarded an honorary doctorate from Oxford, and was a frequent guest and performer for the Royal Family.

Haydn’s two seasons in London (1791 – 92) proved so artistically and financially successful that Salomon arranged a second London trip for 1794 – 95. For both of these sojourns, Haydn’s contract called for him to produce six new symphonies to be given their initial performances in London. These twelve works (numbered as Symphonies 93 – 104) have been collectively dubbed the “London” Symphonies, and you may occasionally see them called the “Salomon” Symphonies. Thanks to Salomon’s connections in London’s music world, Haydn had the best players of the time, and wrote accordingly. While today we are accustomed to performance practice with an orchestra of perhaps 30 musicians, we know from contemporary accounts that performing these pieces with large groups of players was also common practice. In one instance, Haydn heard one of his symphonies performed by an orchestra of over 300 musicians.

Haydn’s Symphony No. 96 acquired the nickname “The Miracle” through an astonishing incident that allegedly took place at its first performance. Haydn’s first biographer, Albert Christoph Dies, chronicled the event:

When Haydn appeared in the orchestra and seated himself at the pianoforte, to conduct a symphony personally, the curious audience in the parterre left their seats and pressed forward towards the orchestra, with a view to seeing Haydn better at close range. The seats in the middle of the parterre were therefore empty, and no sooner were they empty but a great chandelier plunged down, smashed, and threw the numerous company into great confusion. As soon as the first moment of shock was over, and those who had pressed forward realized the danger which they had so luckily escaped, and could find words to express the same, many persons showed their state of mind by shouting loudly: ‘miracle! miracle!’ Haydn himself was much moved, and thanked merciful Providence who had allowed it to happen that he [Haydn] could, to a certain extent, be the reason, or the machine, by which at least thirty persons’ lives were saved. Only a few of the audience received minor bruises.

If this account were listed on snopes.com, it would receive the label “Mostly True.” The event as described did indeed take place, but not at the premiere of Symphony No. 96, but at the first performance of Haydn’s Symphony No. 102 in B-flat. It is thought that the rope that raised and lowered the chandelier either gave way or was improperly secured, causing the chandelier to come crashing down. Nevertheless, Symphony No. 96 bears its unearned nickname to this day.

The symphony itself follows the standard format of his final symphonies. The opening movement begins with a slow introduction full of stark unisons and abrupt shifts of mood and. The ensuing Allegro starts with a sprightly, tripping theme which Haydn explores in all of its facets. Interestingly, where we would expect a contrasting idea, Haydn presents part of the first theme in a different guise. The development which follows deconstructs this melody, with fragments of the tune being flung all over the orchestra, transforming at one point into an elegant fandango. A sudden dramatic pause precedes the return of the opening idea for a concise summation of the entire movement.

The slow movement opens and closes as a graceful dance, with a startlingly dramatic and contrapuntal middle section acting like a thunderstorm in the middle of a bright sunny day. The clouds soon dissipate and dancing resumes, with the material decorated and made more elaborate. Haydn’s final surprise is a brief orchestral cadenza for the solo violin, assisted by the members of the woodwind section, before the dance concludes as serenely as it began.

The dancing changes from courtly elegance to athletic vigor in the Menuetto, with many parallels to the Austrian folk dance known as the Ländler, one of the predecessors of the minuet. The solo oboe in the middle Trio section adds to the folk atmosphere, singing above a simple string accompaniment.

The finale (Vivace) skips mischievously in ebullient high spirits, interrupted by more dramatic and contrapuntal contrasting sections. Even within the stormy interludes, the opening melody is rarely far away, cheekily peaking through the texture as an accompaniment or as a fleeting fragment of melody. Despite all the drama, it is the irrepressible high spirits that win the day, and the symphony’s coda exults in a cascade of string sound, exuberantly punctuated by horns, trumpets, and timpani.

Claude Debussy: Petite Suite (orchestrated by Henri BÜsser)

As a student at the Paris Conservatory, Claude Debussy, when asked by one of his professors what compositional rules he followed, replied “Mon plaisir (“as I please”). Though Debussy was a devoted Wagnerian in his youth, he soon concluded that he had to seek new paths, and he looked to other cultures for inspiration. He was fascinated by the Javanese gamelan orchestras (an orchestra of percussion instruments) at the 1889 Paris Exposition, and in his own music he began to employ pentatonic scales (scales of five notes) and whole-tone scales, where the pitch distance is exactly the same between each note. These six-note scales creates exotic chord sequences that are worlds away from conventional European harmony.

The France of Debussy’s youth was a hotbed of revolution in the arts. The Impressionist painters stormed the barricades of conventional art, beginning in the 1870s, but the earliest shots in France’s artistic revolution came from the Symbolist poets, led by Paul Verlaine, Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, and Stephane Mallarmé. Symbolists felt that emotions should be expressed indirectly, and that their poetic words were metaphors for other ideas. The Symbolists used words just for their sounds, much as Debussy used harmonies and textures, creating startling, imaginative, and sometimes even distasteful poetic images. While the Symbolists were well-grounded in poetic rhythm and meter, they were also unafraid to employ free verse and other avant-garde techniques in expressing their fantastical ideas. The result was an ambiguous, sensual, sexy and surreal poetry, full of double meanings and unconventional visions.

Debussy did not suddenly change musical direction, but gradually transformed his style over the course of nearly two decades. We see the very start of his musical journey in the Petite Suite, written in 1889. This work, originally for piano duet, was influenced by Verlaine’s poetry, most notably the collection Fêtes galantes, which served as the inspiration for the first two movements of the suite. Verlaine’s world of idyll aristocracy blissfully enjoying bucolic trysts (evoking the paintings of Watteau and Fragonard) finds musical expression in the first two movements of Debussy’s suite. En batteau depicts the idyllic rocking of a boat as it glides down a gentle stream, untroubled by the outside world. The subsequent Cortége is more comic than solemn; in Verlaine’s poem, it is a portrait of a noblewoman on a stroll with her pet monkey, followed dutifully by her attendant, who holds the train of her dress. The concluding Menuet and Ballet evoke this same decadent and carefree world, though they are not associated with specific Verlaine poems.

The orchestral version of the Petite Suite was created in 1907 by Debussy’s friend and colleague, Henri Büsser. Büsser was well known as both a composer and conductor, and ended up outliving Debussy by fifty-five years, passing away in 1972 at the age of 101.

The Texas Tech School of Music Presents

An unforgettable concert experience featuring the entirety of the School of Music

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 2024 | 7:30 PM Buddy Holly Hall—Helen DeVitt Jones Theater This concert is free and open to the public.

Eric Allen, LCO Artistic Director

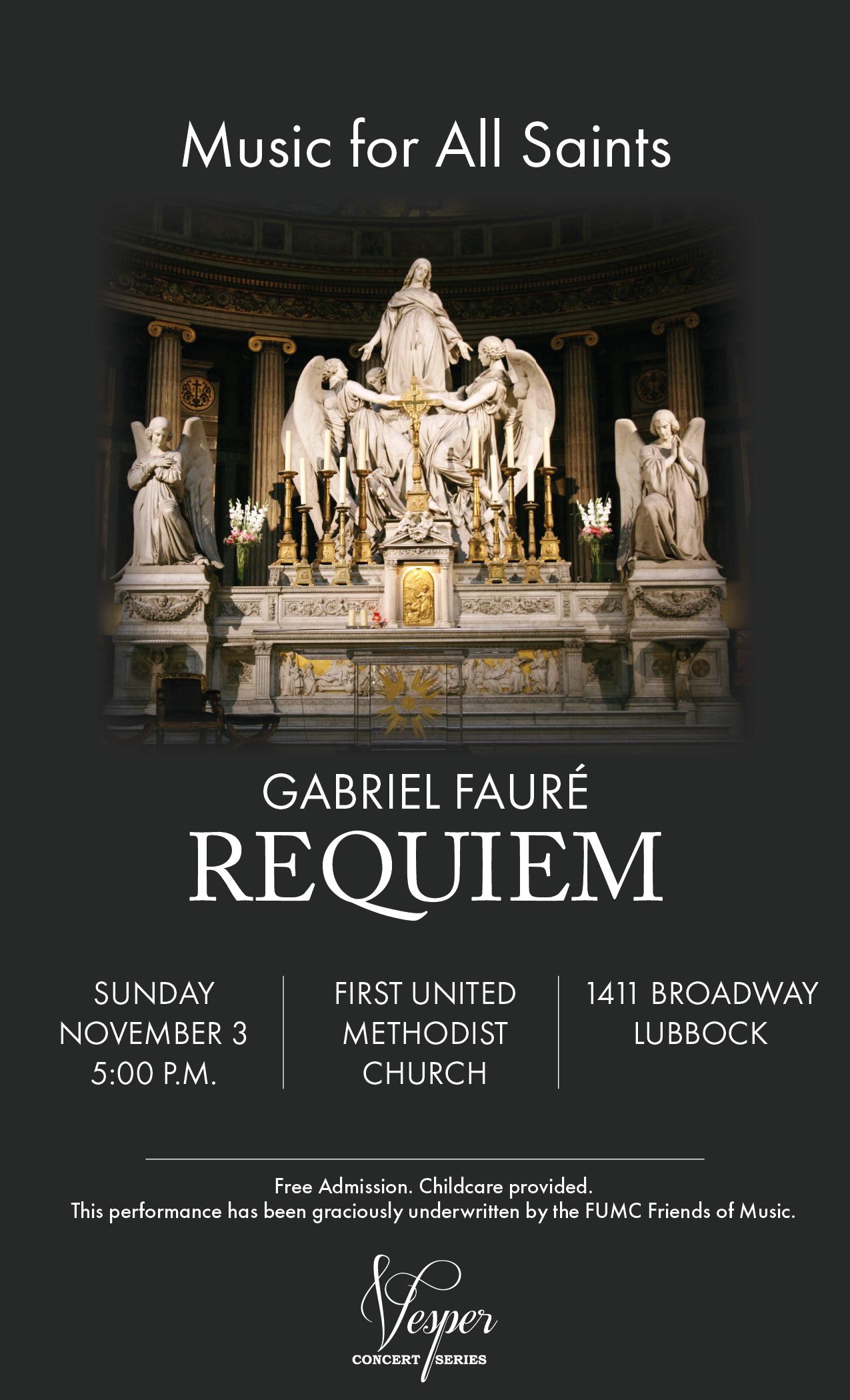

Eric Allen serves the Lubbock Symphony Orchestra as Artistic Director and Conductor of the Lubbock Chamber Orchestra. Allen has led the LCO through stimulating performances of a variety of repertoire including symphonic masterworks, choral collaborations and collaborative solo repertoire. He recently conducted the orchestra in recording D. J. Sparr’s Through Every Gust of Wind: Four Haiku as part of Sparr’s album titled Hard Metal Cantus, published on the Innova Label. Allen also serves as Director of Music Ministries at First United Methodist Church in Lubbock where he conducts the storied Chancel Choir.

In addition to his responsibilities with LSO and FUMC, Dr. Allen serves as Associate Professor of Music and Associate Director of Bands at Texas Tech University where his responsibilities include serving as conductor of the Symphonic Band, directing the Contemporary Music Ensemble, teaching conducting, and assisting with the direction of the Goin' Band from Raiderland. He also teaches courses within the Summer Master of Music Education program.

Under Allen's direction, the Texas Tech Symphonic Band has performed many engaging concerts with repertoire spanning nearly two centuries. The ensemble has also performed many collaborative performances with faculty solo artists and were praised in Fanfare Magazine for their fine accompaniment work on the MSR Classics release of Andrew Stetson's solo album, Rise Above. Further recognition came through their selection by jury to perform at the 2016 CBDNA Southwestern Division Conference in Boulder, Colorado, and the 2020 CBDNA Southwestern Divisional Conference in Norman, Oklahoma. In addition, Allen served as Artistic Director and Conductor for the TTU Contemporary Music Ensemble’s album titled Shifting Direction, scheduled to be released on the Navona Records Label in November of 2024.

A versatile conductor, Allen also serves as music director for the Texas Chamber Winds, an ensemble of university music professors throughout Texas. He will be conducting the ensemble through multiple performances in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in November of 2024.

Allen holds Bachelor and Master of Music Education degrees from Florida State University and a Doctor of Musical Arts in Conducting from the University of Minnesota.