The Grammar of Wood

Developed in response to a prompt to reimagine Tyndall Air Force Base using mass timber, this Clemson University Architecture Studio project reinterprets military design standards through the expressive lens of cross-laminated timber — crafting a language rooted in material logic and structural innovation in the process.

You know those projects that end up the way they do because of the people who did them? I mean, that’s kind of all of them, sure, but in the context of an architecture blog post this truism has a bit more context: there are projects that have a designer’s fingerprints, so to speak, all over them; we know who did what.

This “Grammar of Wood” design wasn’t really one of those projects. This project was a real technical and aesthetic soup, cooked up between friend and studiomate (and LS3P alum!) Ryan Bing and me along with our teammates and comprehensive studio professors. Or maybe it’s more of a stew, in which there are identifiable chunks of authorship that have been transformed after simmering in a hearty stock of teamwork in the architecture studio pressure cooker. Delicious! In short, this project was a hugely collaborative effort.

As many of the readers will know, there comes a time in architecture school when students have to get real, so to speak, and put together a project that is relatively resolved in terms of structure, code compliance, and general programmatic and aesthetic coherence: the comprehensive studio. Our studio took place at Clemson

components according to the directive of the studio, but in the context of our comprehensive studio and our knowledge that this might be our last chance to design, as students, an imaginary building unencumbered by budgetary (and many other) logistical constraints, that just didn’t feel like a project worth doing.

proposed and prescribed by USAF Facility Standards for these and similar projects, we established a new set of goals for our project: to maintain all of the stated schematic and programmatic requirements of these spaces while translating their hyper-efficient modules into a language of our own–not simply by

grammar and idiomatic expressions, so to speak, of mass timber’s design language and designing in styles and at scales that are directly informed by the assembly and tectonics of masstimber components.

Practically speaking, Ryan and I found ourselves with two complementary

small rooms that were difficult to justify building from mass timber. So we did an experiment and spent a weekend trying to determine how much of the auxiliary support building’s program we could “stack” in the walls of the hangars. Turns out, it was almost all of it, and so halfway through the semester, after

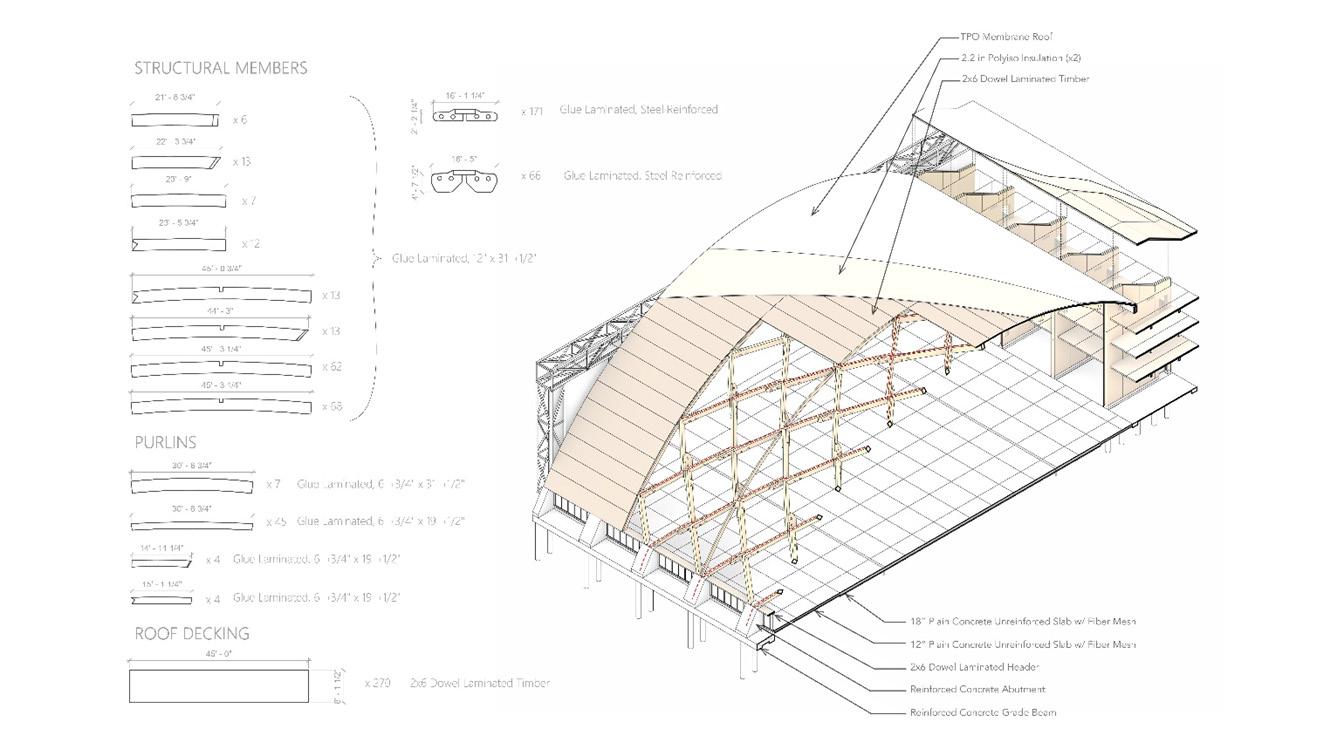

INHABITABLE SUPPORT STRUCTURE OF MAINTENANCE HANGAR

months quietly contemplating a moreinteresting, alternative design, Ryan and I combined our projects into what ultimately became our contribution to The Grammar of Wood: two mass timber hangars, each with an inhabitable wall that comprises both its physical and programmatic support structure.

An interesting by-product of this design process and logic is that the inhabitable wall structure can exist as a stand-alone building: it doesn’t

need to be tied to a hangar and is also just a prototype for a CLT building that can be assembled from a few components: large CLT bulkheads with pockets that support glulam beams that can be dropped in and removed with a crane. There are oversized through-holes in the bulkheads, or “baffles,” as we referred to them, that permit extra maneuverability of the beams during the construction process. The HVAC system is then plumbed through these holes.

INHABITABLE SUPPORT STRUCTURE AND STRUCTURALLY-INDEPENDENT “POPOUT” SPACE

LAMELLA-INSPIRED HANGAR ROOF WITH SUPPORT STRUCTURE

LAYUP AND COMPONENTS OF INHABITABLE SUPPORT STRUCTURE

Similarly, the “pop-out” attachment that we designed to accommodate the layout of the propulsion shop is also a structurally-and-systematicallyindependent CLT building, albeit one of a different flavor and comprising smaller CLT panels of repeating geometries wherever possible. Every panel in every building was designed according to the production capacity of SmartLam’s nearby Alabama facility.

This was a whirlwind of a project, and Ryan and I were really excited with how it turned out. Scrapping your comprehensive studio project and starting your spring break with a blank Revit project and a fresh Rhino file isn’t usually the super prudent thing to do, but there’s a magic that

happens when the dumb thing to do is the smart thing to do. Hopefully, it’ll capture the imagination of other designers and builders and inspire the use and sustainable management of the resources available to us in the American Southeast.

Meet Harrison

Harrison Floyd, a recent graduate of Clemson University with a Master of Architecture and Digital Ecologies certificate, also holds a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering from the University of South Carolina. Harrison’s strong foundation in engineering allows him to bring a dynamic perspective to the projects with which he is involved.

While at Clemson, Harrison won the AIA Henry Adams Medal and the Edward Allen Student Award in 2021 and the Martin A. Davis Award in 2020, served as a graduate teaching assistant for Architecture Foundations, and worked at LS3P as a summer intern. He is currently teaching a secondyear studio and a portfolio class at Clemson and is a Board Member of the Southern Off-Road Biking Association.