Nii SALMON SUMMER/FALL 2024 Haliis’maasaw

Design contributions from Kirsten Whitney, pages 19-25. krstndesign.com

Cover photo courtesy of KLRD. Illustrations by Amanda Key.

Photo, left: courtesy of Dwayne Ridler.

Photo, right: courtesy of KLRD.

© Kitselas Lands and Resources Department, 2024. All rights reserved.

Call for community photos! Enter your photos for a chance to have them featured in print. We’re looking for harvesting, landscape and nature shots! For questions, contact: Cedar Welsh LR.Manager@kitselas.com | 778-634-3517 kitselas.com

Copyright

15 Salmon: Long Distance Travellers Kitselas Lands and Resources Staff 21 Forest Gardens in Laxyuubm Gitselasu Guest article: Chelsey Geralda Armstrong 2 Message from the Director Cyril Bennett-Nabess 9 Fun Facts For All Ages: Mook! Madison Gerow, Kitselas Lands and Resources Staff 3 Mapping Our Values on the Landscape Kitselas Lands and Resources Staff 14 NEW! Sm’algyax Wordsearch Kitselas Lands and Resources Staff 19 From the Community: Smoked Moose Pepperoni Recipe Michael Seymour 25 Youth Connections: Life Lessons from the Kitselas Court Mercedes Seymour TABLE OF CONTENTS 1

Message from the Director

Welcome to the fourth edition of Nii magazine!

In this issue, we honor Kitselas perspectives on teaching and learning, which have been passed down through generations. We recognize the importance of respecting and honouring our elders and teachers, who have shared their knowledge and time with us.

As we celebrate the Salmon harvest and the dedication of our harvesters, we also highlight the progress of our salmon programs and other projects, such as the Kitselas Geospatial Classification System (GCS) mapping project and the Gitsaex Forest Garden. Our youth feature showcases the success story of Mercedes Seymour, who has thrived through basketball.

We also introduce a new feature, a Sm’algyax wordsearch puzzle, to promote language revitalization. This magazine is a testament to the strength of our community, and we encourage you to share your stories, photos, and experiences, which will enrich our publication and strengthen our community bonds.

Let us come together to celebrate our harvest, environmental stewardship, and the knowledge passed down from our elders. Contact us at the Lands and Resources department to share your contributions or discuss our articles. Thank you!

Wai Wah!

Cyril Bennett-Nabess

2

Mapping Our Values on the Landscape

KITSELAS LANDS AND RESOURCES STAFF

The Kitselas Geospatial Classification System (GCS) is a mapping tool developed by the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department (KLRD) to help review projects and their impacts on the Traditional Territory. The GCS stores important land use and cultural information that can be used to identify potential impacts to Kitselas values. It can also be used in consultation to ensure that Kitselas’ rights, interests and concerns are fully considered during regulatory approvals.

The Project

The GCS was developed to perform mapping analyses for Kitselas First Nation. The mapping tool can visualize the natural landscape (forests, flora, waterbodies) of the Traditional Territory, showing how the land was and is traditionally used by the Kitselas First Nation. As a living project, data for the mapping tool is continuously collected.

Photo courtesy of Chelsey Geralda Armstrong.

3

Traditional Use Studies (TUS)

Traditional Use Studies are comprehensive research projects aimed at documenting and preserving the cultural heritage and traditional knowledge of Indigenous communities. For the Kitselas First Nation, TUS identify and map areas of cultural significance, which can include sacred sites, hunting and fishing grounds, plant gathering areas, and historical landmarks. The methodology of TUS typically involves a combination of oral history interviews, ethnographic research,

Introduction to the TUS database

The most important part of the project was to merge information into a master TUS database. That included previously recorded survey data, articles, oral histories, books, and many interviews.

Each individual TUS record was linked to a place on the map. This master database covers the entire Traditional Territory. It gives a detailed reference of how Kitselas use the land and marine environments.

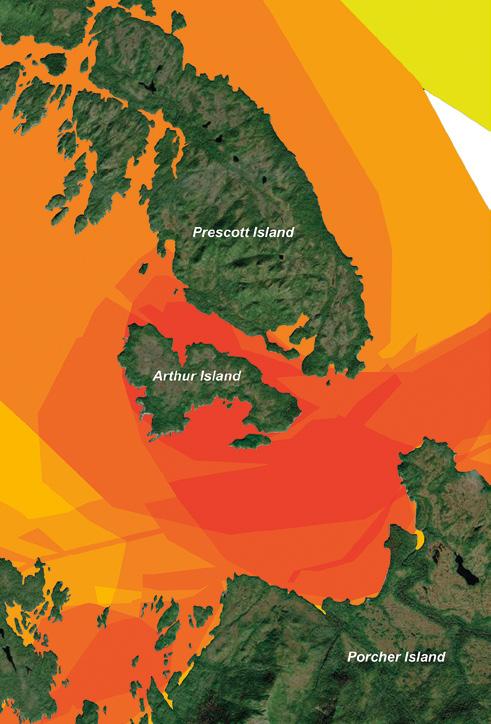

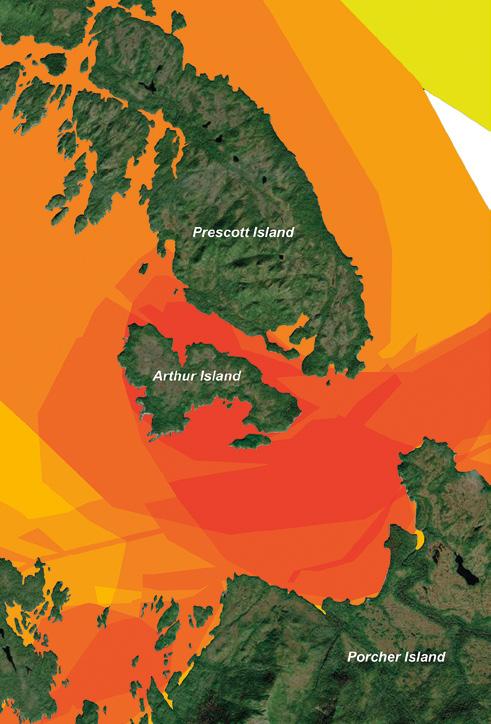

The map to the right shows how that data can be visualized like a “heat map.” The colours let you quickly see high-use marine areas for Kitselas near Porcher Island. The darker areas mean more traditional use by Kitselas in the past and today.

The TUS database also includes a new type of value for all data: The Value of Relative Importance (VRI). Those numbers are based on the Kitselas Values metrics being developed by KLRD with valuable community feedback over the last few years! This includes details like what a particular space was used for and how often.

archaeological surveys, and historical document reviews. Community elders and knowledge keepers play a pivotal role in providing the information that forms the basis of these studies. TUS are a vital tool for Kitselas First Nation, helping to safeguard cultural heritage sites, inform resource management, support legal rights, empower the community, and educate others about the rich traditions and history of the Kitselas people. All collected data is stored securely and confidentially.

TUS Density Level

Less More

Kitselas Marine TUS

TUS Density Level

Less More

Kitselas Marine TUS

4

Introduction to the landscape database

All of the processes modeled became a series of databases. These databases cover the whole Traditional Territory. The landscape database cuts the territory up into millions of chunks. Each chunk has important details about its landcover features.

Interesting information about each outlined chunk is identified, such as:

• the type of ground cover,

• the type of trees,

• the age of the trees,

• how steep the slope is there,

• which direction any hillside chunk faces,

• the type of bedrock,

• how moist the soil is, and so much more!

Introduction to landscape modeling

KLRD developed a series of models that were used to process data from many government agencies into seamless datasets. This was a special challenge because many of them were created for different departments with different needs. That meant that the datasets rarely matched each other. They sometimes had a different scope or didn’t match the size of the Traditional Territory.

The models were run on different datasets to create the landcover representation. That included numerous landcover and hydrological datasets used to develop riparian zones, and identify areas where human activity changed the landscape, including infrastructure and industrial activity like building roads, right of ways, housing, and logging. Together, the TUS database and landscape models can be used to inform KLRD’s work.

Below left is an image of the Kleanza Creek area. Below right is a map built from the landscape datasets. The map shows human activity, waterways, and many smaller outlined “chunks” of land. These chunks represent data on plants, geology, traditional use, and more.

5

Model validation in the field

One important element to complete was verifying the quality of the landscape datasets to validate its accuracy. In collaboration with Wai Wah Environmental Ltd. (WWE), several survey sites were selected. The field team visited the selected sites and cataloged what was there. The information the field team gathered was compared to the landscape datasets to check that the data reflected the reality on the ground.

One of the primary functions of the GCS is to serve as a comprehensive overview of all activities on the Traditional Territory. It is like giving a bird’s-eye view that helps the Nation plan and make informed decisions about land use.

How can the GCS be used?

The GCS is used by Kitselas First Nation to answer questions related to the landscape. What kind of questions? The map below shows the answer to “where are the old-growth forests in and around Gitaus?” The yellow areas outline forests that are over 250 years old. Using the landscape database and defining what can be called an old-growth forest, a user can identify such areas. That’s just one example of the questions that can be asked!

The GCS is always evolving as data is added, revised, or revitalized. Because the landscape constantly changes, updating the database will be an ongoing project.

Old growth forest

More than 250 years old

This type of information helps identify key areas important for Kitselas to preserve and protect.

6

Imagine another scene: What if a ship sank near the mouth of the Skeena? What if Genn Island and Little Genn Island were in the zone of floating debris from the ship? How would that impact Kitselas interests in the area?

Above on the left is an overview of the marine traffic for one year in the Skeena Estuary. Red means a very high-traffic area, yellow is moderate and green is low traffic. Genn and Little Genn Islands are inside the dashed boundary, right in the middle of the high-traffic area for ships moving through the Malacca Passage.

If you zoom into the area (above right) and use the marine part of the GCS, you can tell what species might be impacted by the ship’s debris. That helps determine how to clean up the area and minimize damage. Based on the current traditional use information, we can see that Genn and Little Genn Islands are very important for harvesting.

Traffic

High Medium Low

Marine

Density

Marine TUS: TUS Density Level 5 4 Kitselas value Number Seal 1 Rockfish 2 Octopus 2 Merganser 2 Halibut 2 Pacific cod 2 Ling cod 2 Chum salmon 1 Pink salmon 1 Chinook salmon 1 7

Kitselas

What’s next?

It will be important to keep collecting data on the ground and from the air to monitor how important features of the territory are changing. Most importantly, fleshing out the lowdata areas will improve the accuracy of the model, making queries like those described above more accurate and meaningful.

A new project being developed is the “Knowledge of the Laxyuubm Gitselasu” that will gather new information with the help of

Kitselas members. The information shared will further enhance the databases, especially to identify key areas and uses throughout the Traditional Territory.

This additional data will improve how the GCS works.

Stay tuned for future updates. There is more to come!

8

Photos courtesy of KLRD staff

FUN FACTS FOR ALL AGES

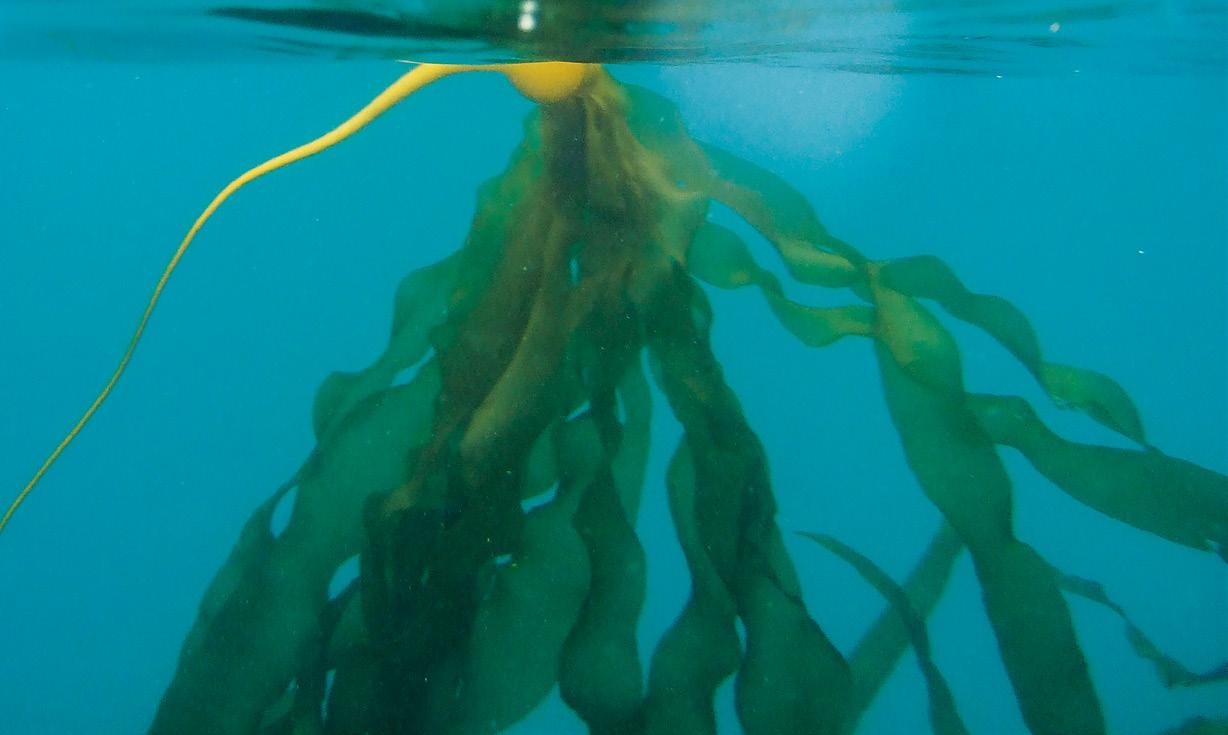

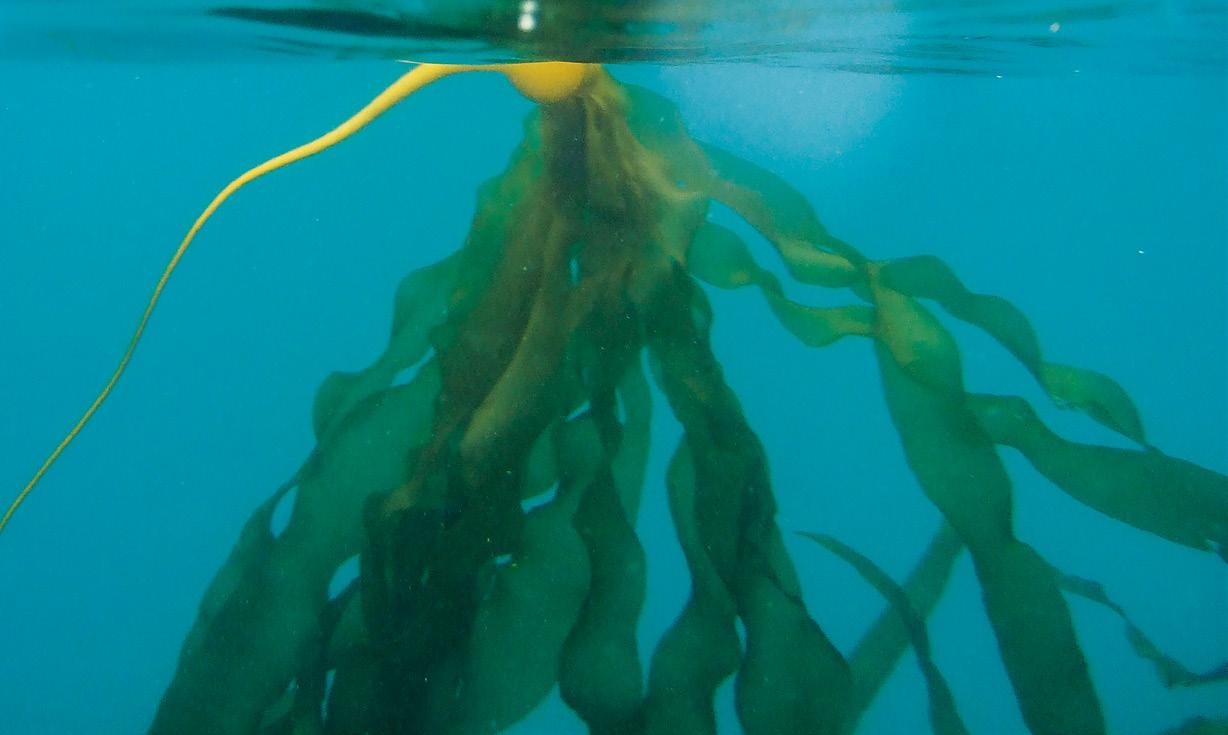

BULL KELP Mook

BY MADISON GEROW

Mook is a type of seaweed that thrives in the rough and tumble coastal waters from California to Alaska. It adds a rich and diverse marine ecosystem to our watersheds. Mook is often harvested for food products or aquaculture.

Kelp, in general, holds immense importance culturally and as an ecosystem indicator. Mook is bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) that provides rich diversity to our watershed’s ecosystem. It helps other species thrive, too. Fish, urchins, and sea otters, among many others, depend on mook! If mook is declining in an area, the impact most likely cascades onto other marine species in that area.

Mook is an annual seaweed: it matures from a spore in just one year. It quickly grows multiple blades from a single stipe before dying. Although mook growth peaks in summer to fall, some harvesters collect softer and younger mook in the spring while they are still in various stages of development, and the bladder is the size of a thumbnail!

Ha’mook

“drinking straw”

In this word, “mook” refers to the stipes of bull kelp, which are long and hollow, allowing them to be used as a straw!

Neil Banas / Flickr

9

Biology

Thefourmain parts of mook

Blades

The narrow and flat blades can collapse with the current — an adaptation to turbulent water. The bladder and several blades make up the thallus.

Pneumatocyst

The pneumatocyst, or bladder, is filled with gas and helps mook reach the sunlight by floating the blades towards the surface.

The gas inside the bladder is up to 10% carbon monoxide (CO). Once combined with water, the CO is turned into glucose used as energy for photosynthesis.

A stipe (plant stalk) grows vertically from the holdfast, reaching for the sunlight on the surface.

The holdfast anchors into a hard rock or sediment. In the holdfast, root-like structures called haptera hold the mook to the seafloor.

Stipe

Holdfast

10

Illustration by Amanda Key.

Mook grows 250 cm a day, on average.

That’s about 10 cm every hour!

Mook can grow up to 35 metres in a single year.

That’s as long as three school buses!

Within the blades are reproductive sori (patches) that fall to the seafloor once they are heavy and mature enough to propagate. Think of these as the ocean’s acorns! This usually happens in fall. The spores in the sori settle on suitable sediment that will encourage growth.

Ferns have sori

just like mook!

Detritus can wash up on shore and is known as wrack.

Stories recount how Raven and his brother were found in mook beds!

Although mook looks delicate, dancing in the current, it is strong enough that our ancestors used it in many ways:

• stipes were used as fishing lines

• gas-filled bladders were used for storage, cooking and as anchor lines

• floating thallus were used for navigation along “kelp highways”

10 cm

Kate Turner/iNaturalist

11

Alanah Nasadyk/Flickr

Ecosystems

Mook beds are biologically very productive. They are key to the health of other marine ecosystems and part of healthy biodiversity that serves as nutrients for a vast array of marine life. The constant shedding of blades creates a cloudburst of organic matter that is eaten by many organisms. This organic matter is called detritus. Organisms that eat detritus (snails, shrimp, crab, and more!) are vital food sources for larger organisms like herring. These fascinating mook forests are a protective home for fish, invertebrates (snails, crabs, sea stars, sea urchins, etc) and marine mammals like sea otters. These forests are prime fishing habitat! The thick and tall mook forests also slow down wave action. This protects the coastline from being pounded by heavy waves.

Unfortunately, mook forests from California to Alaska have declined. This is due to factors such as climate change, pollution, invasive species, habitat degradation, and even boating through them. Sea star wasting syndrome (causing mass mortality) has also caused a domino effect, adding to mook forest decline: fewer sea stars mean that invasive urchin populations they prey on can grow too fast. Urchins are known to fiercely eat large quantities of mook, depleting an entire ecosystem that once flourished.

Herring

Herring relies on mook for direct and indirect needs. An example of a direct need is their use of mook to deposit eggs (or roe). In spring, female herring lay thousands upon thousands of eggs on various surfaces including kelp, branches, and rock. Herring roe on kelp is an important traditional food for Coastal Indigenous peoples. An example of herring’s indirect needs include using the kelp forests to consume small invertebrates and detritus.

12

Photos courtesy of KLRD staff

Mook Monitoring Project

Integrated Marine Plan Partnership and Environmental Stewardship Initiative, North Coast Cumulative Effects Program

The North Coast of BC supports a range of ecosystems under pressure from many small and large economic activities. This includes commercial fisheries, nearshore development, forestry, port activities, and tourism. The potential cumulative effects of industrial activities in the North Coast are a concern for Kitselas and other North Coast First Nations.

The Nations partnered with the province of BC to assess and manage the cumulative impacts on environmental, social, economic, health,

and cultural values in the area. The program monitors estuary “values.” Values are the ecological and human well-being links to an estuary. The program monitors many different factors, including kelp amount and location. The reports from this program will help participating Coastal Nations (such as Kitselas First Nation) make management decisions about protected areas, ecosystem restoration, and what assessments of cumulative effects need to be done.

Mook bed mapping

Using a kayak at low tide, a technician maps the edges of the mook bed (depth and width) using a GPS tracker. Next, a rope is laid across the mook bed to create a transect (shown in red). A series of quadrats one square meter in size (shown in green) are laid out along the transect. The technician counts all the mook bladders and blades inside each quadrat.

The technician also collects data such as temperature and salinity. This survey work is done year after year. These surveys give us a baseline of the size and location of mook habitat. We can then watch for changes in the species over time in response to industrial development.

GPS track

Transect

Quadrat

13

Sm’algyax Wordsearch

See if you can find these Sm’algyax words in the square above!

Aas (soapberry)

Aatabiis (butterfly)

Amgan (cedar)

Gitsilaasu (people of the canyon)

Hon (salmon)

Kaw (thimbleberry)

Medeek (grizzly bear)

Misoo (sockeye)

Ptsaan (totem)

Sket (spider)

Smmaay (blueberry)

Hawn (fish)

Tlagots (rhubarb)

Tsilasuu (canyon)

Wooms (devils club)

A U A E T E O O M E D E E K A U H S M I S O O A E T E S K S S A T T A I M A I W O M O A I T U I K A A I N A M G S S L S M S G S A W M O Y D A E E T T A N S B M D K S N T S A I A I O K A G A K M S L S S A M U A I S L M A T E S I D M L T S T E O I P O A N O O A S L O A A S W S W S G I P L G A S G L A L A U N A A E A M S W M Y I M G S S T S I M A T G D T W S M K N T H O N Y T P T S A A N S B H A W N E U S A I N L A B T N A E M I M U A S A S I S U O 14

Salmon LONG DISTANCE TRAVELLERS

KITSELAS LANDS AND RESOURCES STAFF

The Skeena River is the second-highest salmon-producing system in British Columbia. It is home to five different species of salmon: misoo (sockeye), yee (chinook), üüx (coho), sti’moon (pink) and gayniis (chum). Each population of salmon is genetically adapted to their environment, which means they all exhibit unique migration routes, timing, and productivity.

Salmon are anadromous — they migrate up rivers from the ocean to spawn, allowing them to live in both freshwater and marine environments. Salmon are quite extraordinary as they return to their natal rivers to spawn, after spending years in the Pacific Ocean hundreds of kilometres away.

Indigenous communities across the Northwest have had a relationship with the Pacific salmon population since time immemorial; Kitselas is no exception. The deep spiritual, cultural, social and economic relationship we have with salmon is difficult to put into words. For many Indigenous Peoples, the preservation of salmon is integral to our way of life and the preservation of our Traditional Knowledge, ceremonies, and livelihood.

Unfortunately, the impact of commercial fisheries, decades of mismanagement, and climate change have created several challenges for sustainable salmon fishery management, and the number of salmon returning to their spawning grounds each year has been severely declining, including those closest to our community (Kleanza, Lakelse, Copper, etc.).

Today, Indigenous harvesting technologies, many of which were outlawed post-contact, provide an opportunity for sustainable co-management strategies and stewardship. The Lake Babine Nation (LBN) fisheries program, for example, has successfully co-managed the Babine counting fence with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) since 2007. The fence is located 1 km below the outlet of Nilkitkwa Lake on LBN’s Traditional Territory, and relies on traditional Indigenous harvesting technology to monitor and protect the thousands of salmon that return to the Lake Babine watershed each year.

Milton Love/Wikimedia

15

Kitwanga Sockeye Smolt Enumeration Facility

Kitwanga Salmon Enumeration Facility

Tyee Test Fishery

Singlehurst Creek Salmon Enhancement

SkeenaRiver

SkeenaRiver

SkeenaRiver

BulkleyRiver

Morice Lake

Lakelse Lake

Zimoetz River

Kitsumkalum Lake

16

Skeena Estuary

From Babine Lake to the Pacific Ocean and back again!

Salmon spend the first few months to years in the river beds of the Skeena River before making the long journey to the Pacific Ocean. There they typically spend one to three years feeding and mature into adult salmon. When they are ready to spawn, salmon return to the Skeena and travel to their natal rivers. Approximately 90% of returning Skeena sockeye travel to Babine Lake and spawn in the upper section of the watershed.

Salmon Migration Route

Kitselas Traditional Territory

Kitselas Reserves

Fisheries Management Facilities or Projects

Babine River Salmon Counting Fence

Babine River Salmon Smolt Counting Fence

Fulton River Spawning Channel

Pinkut Creek Spawing Channel

Babine Lake

17

Project Highlight: Kitselas Salmon Enhancement Program

Historically, salmon spawned in great numbers throughout Kleanza Creek and the adjacent Singlehurst Creek, which provided an important fishery for Kitselas. Over time, Kitselas has witnessed a decline in salmon and is concerned that habitat loss, climate change, and other factors will continue to suppress salmon returns.

In 2021, Kitselas initiated a multi-year salmon habitat enhancement project for Kleanza Creek

and adjacent watersheds, with funding provided by the BC Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund.

Nine potential salmon habitat enhancement options were identified. After a series of additional studies and comprehensive evaluation, a set of overwintering pools, located on Singlehurst Creek within IR #1 (between Kleanza Creek and Gitaus), was selected as the preferred project.

Singlehurst Creek Salmon Enhancement: Overwintering Pools

Benefits and rationale:

Constructing overwintering pools are a known salmon habitat enhancement method shown to successfully increase overwintering survival of juvenile fish.

These overwintering pools will be used by coho salmon that spawn in Singlehurst Creek, and likely other fish that spawn in Kleanza Creek and other streams along the Skeena River.

Project description:

• Three new overwintering pools were established along an existing groundwater-fed tributary to Singlehurst Creek.

• Pool sizes ranged from 20 to 50 meters in width, and up to 2 meters deep.

• Improved fish passage up the groundwaterfed tributary for year-round fish access to the overwintering pools.

Effectiveness monitoring:

• Initial monitoring of the salmon enhancement project began in the spring of 2024.

• Monitoring will include aquatic habitat, water quantity and quality, and fish community monitoring of the three overwintering ponds.

The goal of the program is to return a sustained abundance of wild salmon to the region

18

From the Community

Michael Seymour

Smoked Moose Pepperoni Recipe

6 lbs ground moose

4 lb ground pork butt

6 tablespoons kosher salt

4 tablespoons paprika

4 tablespoons sugar

2 tablespoons fine ground black pepper

2 tablespoons cayenne pepper

2 teaspoons crushed anise seed

2 teaspoons ground cumin seed

2 teaspoons dried oregano

2 teaspoons dried thyme

2 cups non-fat dry milk powder

2 teaspoons #1 cure (prague powder or Instacure)

1/2 cup ice cold beer

Cut the moose and pork into cubes, then grind it through the medium plate of your sausage grinder.

Make a paste of the milk powder and cold beer and mix it with the cure and all the spices in a small container.

Add the cure/dried milk/spice combination to the ground meat and mix it thoroughly, kneading it by hand until it is very well distributed.

Stuff the sausage immediately into casings (either collagen or natural sheep or pork), and refrigerate the links for 12-24 hours to let the flavors combine well.

After the aging, prepare your sausage pepperoni for the smoker, and smoke it until the internal temperature reaches 152°F. Place on ice in cooler to stop the cooking process and then refrigerate.

19

The Gitselasu: People of the Canyon. Come walk in the footsteps of our ancestors.

Kitselas Canyon is the ancient home of the Gitselasu people. Oral histories recount the arrival of Gitselasu ancestors to this abundant place, and archaeological research has uncovered evidence spanning at least 6,000 years.

Kitselas Canyon was designated as one of Canada’s National Historic Sites in 1972. Today, Kitselas First Nation has developed this naturally beautiful place of history into a cultural eco-tourism attraction and welcomes the world to see it for themselves.

Rich with history and natural beauty, Kitselas Canyon is a regionally significant site for education, recreation, and cultural connection. A user-friendly nature trail (approx. 2.5 km round trip) leads from the interpretive centre through a moss-covered forest to the four Tsm’syen crest poles and a viewing platform overlooking the mighty Skeena River. Interpretive signs highlight traditionally used plant species and tell the stories of the canyon’s villages.

New hiking trails and interpretive displays are being developed for the 2024-2025 seasons — come and learn about the changes we have in store!

Guided and self-guided tours

We welcome visitors of all ages and abilities to enjoy all that our beautiful canyon landscape has to offer. Admission fees allow access to interpretive displays, trails, and washroom facilities.

Guided walking tours available from July to August and start from the interpretive centre each day at 10:00 am and 1:00 pm.

(Please arrive early.) Visitors may opt to join a guided walk or enjoy the site at their leisure. Allow at least 1.5 hours for your visit.

Plan your visit

Kitselas Canyon is open from mid-May the end of September.

Located a short 10 minute drive east of Terrace on Highway 16

School group and corporate event rates are available upon request.

Visit www.kitselascanyon.ca for the latest opening hours and admissions information.

20

Forest Gardens in Laxyuubm Gitselasu

BY CHELSEY GERALDA ARMSTRONG

21

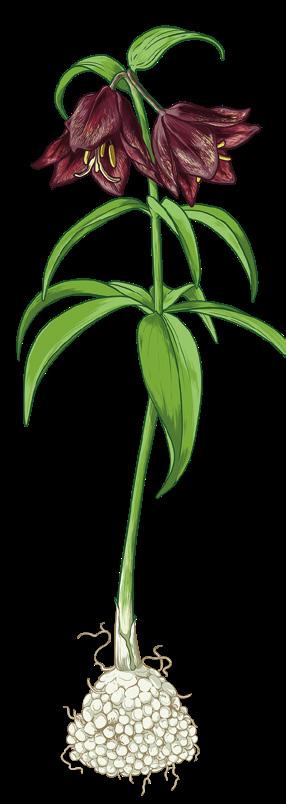

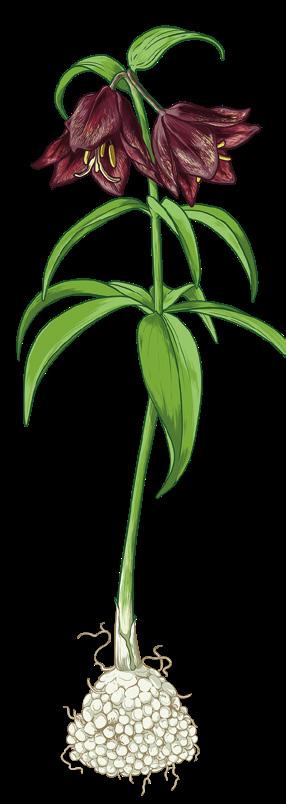

Photo: Gitsaex rice root. Courtesy of Chelsey Geralda Armstrong.

Plants found in forest gardens

• łaaya (highbush cranberry),

• moolks (Pacific crabapple),

• aas (soapberry),

• wineeym desx (hazelnut),

• gyem (saskatoon berry),

• saxsaasax (black hawthorn),

• miyuubmgyet (wild rice root),

• q’elámst (wild cherries),

• lo’ots (red elderberry), and

• wild ginger.

For thousands of years, Ts’msyen societies cultivated plants, soils, and lands across the laxyuubm. From ancestral cities like Gitangasx and Temlaxam, people spread throughout their Skeena and coastal homelands. Local land stewardship practices followed.

One of these longstanding place-making practices is forest gardening. Forests gardens aren’t like regular boxed or row gardens, they are broadleaf forests of berries, nuts, roots, and medicine plants.

Forest gardens are large swathes of land that have been burned, cleared, and maintained by people to support food and medicine plants, and to diversify diets. We cannot emphasize

enough, how important berries (maay) were to Gitselasu. Berries were both a food and a trade commodity central to their economies and lifeways. Since colonialism, forest gardening practices became secret. But today those traditions are coming back to life. Thanks to the labour and effort of Gitselasu ancestors, forest gardens in the Kitselas Canyon continue to push through the earth every year.

22

Northern Rice Root. Illustrations by Amanda Key.

Forest Gardening in Sm’algyax

Laxts’a’adzaks: Gardened landscape or farmland

Wa’naa: A verb paired with a noun to describe the act of planting the noun.

Heelda nah wa’naam siguussiidm = “We planted lots of potatoes”

S s’ndooyntk or si ndooyn: “Garden” in Gitxaała dialect.

sa = do/make/get; ’n = where; doo = put down/lie down/have; and the final n expresses an action that makes another action happen

Spaxgangan: A forest managed for food and medicines.

spa = place gangan = forest

The Gitsaex forest garden is one of the most well-known and most-studied forest gardens in all of British Columbia. Over the last eight years, researchers from Simon Fraser University (me) and, more recently, from the University of British Columbia (Jean-Thomas Cornelis and Jennifer Grenz) teamed up with the Kitselas Health Department’s Foods Systems Coordinator, Patsy Drummond, to study Kitselas Canyon forest gardens. Our aim is to bring them back to life and back to the community. With incredible support from Kitselas Lands and Resources Department and the Gitselasu Stewardship Society, we have been able to study the plant communities, archaeology, and soil ecology of forest gardens at Gitsaex.

TOGETHER, OUR WORK HAS FOUND THAT:

• Forest gardens provided important food stores for people in the past. Today they are still resources for animals and pollinators. (Bears love to hang out in the forest gardens, so be aware if you’re planning to visit!)

• Forest garden topsoils are more nutrient-rich and more able to store nutrients than most forests in the Skeena Region. This means ancestors were enriching soils, likely with fish scraps and charcoal.

• In the distant past, hazelnut was transplanted from the southern Interior (Shuswap) to the Canyon. That is evidence of long-distance trade relationships across the continent.

• Villages in the Kitselas Canyon are much bigger and much older than archaeologists previously observed.

Moolks (Pacific Crab Apple)

23

Moolks (Pacific Crab Apple) seeds. Courtesy of Chelsey Geralda Armstrong.

Forest gardens represent abrupt departures from the surrounding ecosystem. The dark, closed canopy of the conifer forest opens up and is replaced by a sunny, orchard-like spread of foodproducing trees and shrubs, such as crabapple, hazelnut, and cranberry. Forest gardens are usually close to village complexes.

Over the last five years, Patsy Drummond and her team has been building a flourishing community-based food program in Gitaus. This supports the Gitaus greenhouse growing delicious greens and veggies, and distributing food boxes and lunches. Now we are working hard to bring forest gardening to Gitaus with the support of SFU/UBC researchers and Kitselas Canyon experts like Darren Bolton, Travis Freeland, Sierra Spencer, Isaiah Bevan-Wright, and Desiree Bolton.

Our goal is to create the Gitselasu Pilot Forest Garden site in the community garden on Kshish Street. This summer we will build and amend soils that mimic soils in Gitsaex. We will transplant favourite forest foods and medicines, creating a citizen-science experiment zone. This builds a space for community to hang out and learn about harvesting and processing local foods and medicines. We will be in full swing this summer. So stop by the community garden and get to know your Gitselasu Forest Garden!

Periphery forest

Forest garden

Periphery forest

Forest garden

24

Village house platforms River

Life Lessons from the Kitselas Court

MERCEDES SEYMOUR

Mercedes Seymour, Kitselas Keepers Basketball Player, shares how the love of sport encourages her to reach further on and off the court.

Mentorship

My main mentors in basketball are my coaches: Sam Harris, Sara Squires, and Gerald Nyce. They sparked my interest and gave me a love for the game. They helped me so much these past six years; right from when I first started playing for the Kitselas teams. They helped me grow and improve. We notice the hard work they put into the Kitselas teams. I appreciate

all of them for putting in this time and effort to push us individually and as a team. Thanks to their support, I extended my basketball career beyond Kitselas to school teams such as Skeena Jr and Caledonia Sr. I played countless games and tournaments including the 2024 Provincial Senior Girls Championship Tournament in Langley and four Jr All Native tournaments. I am very excited for what the rest of my basketball journey brings me, as I am only in Grade 10! I am incredibly thankful that my coaches pushed me this far in basketball and continue pushing me towards bigger accomplishments.

YOUTH CONNECTIONS SERIES

25

All photos courtesy of Mercedes Seymour.

Confidence Boost

The Kitselas Keepers gave me the confidence to go further in sport. We uplift and inspire each other to keep improving, not only for ourselves but as a team. This team has become a second family to me. Without them, I don’t think I would be interested in the sport. Even through the off-season, we all keep in touch. We are always looking for ways to stay in shape and become better and stronger for the next season. Since we have been together for three years, I feel the most confident and comfortable around my teammates.

The Kitselas Keepers gave me the confidence to go further in sport. We uplift and inspire each other to keep improving, not only for ourselves but as a team.

26

Better Mental Health

In my experience, basketball is very important for youth development. Not only does it keep you physically healthy, it gives you an outlet for whatever is going on outside of basketball. I get a mental break any time I pick up a basketball. Life can get very stressful, especially in the first year of high school. Having practice every day calms my mind. Having a couple of hours each day where all I can think about is basketball improved my mental health.

Kitselas Culture

Basketball brought me closer to my family and culture because I feel supported. Before 2018, there were no Kitselas basketball teams. Being on the Kitselas team when it first started, we attended Jr All Native in Kitamaat. I was shocked to see so many Kitselas members come to all our games. They were there all the way to the semi-finals where we placed top four in the 13 and under category. As we attended more Jr All Native tournaments, the amount of support we received from our community brought us closer and closer to our Kitselas community. We enriched the culture every time we represented Kitselas.

From the Court to Life

Basketball taught me dedication in not giving up. There were many times I wanted to give up after a bad game! But those bad games gave me an idea of what I needed to work on. Each one was an opportunity to improve in the next game. Another life lesson I have learned through basketball is to have fun. Yes, it is nice to win, but it’s even better when you have fun! The games are more memorable when you focus on enjoying yourself. When you have fun playing, it shows how much you love the sport, and how it has shaped you as a player.

27

Participate in our Elder Connections series

This is an opportunity for youth to connect with Elders in their family by interviewing their family members and learning from them. We are providing the platform of this article series to demonstrate knowledge transmission from one generation to another.

Are you interested in writing an article for this series?

We are looking for Kitselas youth under 25 who would like to interview their elders and write about that experience in their own words.

We will provide the cost of a one-time meal to facilitate the interview.

We are looking for writing with a minimum of 500 words and a maximum of 1200 words for the article.

Suggested questions for your elders:

• How have you experienced material/processing change in harvesting traditional foods in your family?

• How have you experienced seasonal changes in the timing of harvesting?

• How have our cultural ways experienced change for the better/worse?

• What hopes do you have for your family or for Kitselas?

• Development on reserves: What amenities do you hope for on reserve?

• Knowledge transmission: What is the best way for younger generations to learn about Kitselsas Land Connections?

We recommend providing a sheet with these questions to each elder after the interview. If they forget to mention something and want to include it, they can write down their thoughts later.

Please contact Madison Gerow, LR.Reception@kitselas.com, if you would like to participate!

The next issue of the magazine will be published in the winter.

28

Kitselas Traditional Territory

Kitselas is a Tsimshian (Ts’mysen) Nation whose Traditional Territory stretches from the Pacific Ocean on the north coast, about 200 km inland, to the lower Skeena River Valley. Kitselas culture and history is deeply rooted in the land, as demonstrated by numerous archeological sites and the traditional land and resource management practices of the Gitselasu (People of the Canyon).

29

100% Environmental Benefits Statement By using paper made with 100% post-consumer recycled content, the following resources have been saved. Environmental impact estimates were made using the Environmental Paper Network Paper Calculator Version 4.0. For more information visit www.papercalculator.org 3 Trees Fully grown 1.4 Energy Million BTU 5 Solid waste Kilograms 1014 Water Litres 669 Greenhouse gases Kilograms kitselas.com 778-634-3517

Photo, top: Courtesy of KLRD staff Bottom: Courtesy of Chelsey Geralda Armstrong.

TUS Density Level

Less More

Kitselas Marine TUS

TUS Density Level

Less More

Kitselas Marine TUS

Periphery forest

Forest garden

Periphery forest

Forest garden