Haliisuuah Nii EULACHON WINTER/SPRING 2023

kitselas.com

Ptarmigans are hardy members of the grouse family that spend most of their lives on the ground at or above treeline. During the winter when it is snowy, these birds are white; during the summer when the snow has melted, they are brown or tan. Construction of the nest, incubation of the eggs, and rearing of the young are activities performed exclusively by the female. Nests (right) are sparsely lined with grasses, lichens, leaves, and feathers.

Photos courtesy of Dwayne Ridler

Front Cover:

Aerial photograph of a side channel of the Skeena River in January. The photo was captured using a drone by KLRD staff. Drones are a very helpful tool to capture higher resolution imagery than what is available from Google Earth. The greater detail allows for better project planning and site monitoring.

Copyright © Kitselas Lands and Resources Department, 2023. All rights reserved.

Call for community photos! Enter your photos for a chance to have them featured in print. We’re looking for harvesting, landscape and nature shots! For questions, contact:

Cedar Welsh LR.Manager@kitselas.com 778-634-3517

TABLE OF CONTENTS Letters from Chief Glenn Bennett and the Director of Lands and Resources ............................... 2 Kitselas Stewardship Education Centre ..................... 3 Eulachon Monitoring ..................................................... 7 Fun Facts For All Ages: Mountain Goats! ................ 12 Elder Connections: Seymour Family ........................ 17 Photos From the Community: Dwayne Ridler........20 1

Chief Glenn Bennett

For thousands of years, our people have had a unique and intimate connection to the land. Our oral histories, the stories of our elders, and even personal stories and experiences from our own pasts highlight the depth of this connection in different ways. Today we continue to practice our traditions and create new stories with our families as we explore, harvest, and learn more about the lands and resources of our Territory.

These lands and resources have shaped our community. The land has made us strong, providing a natural vantage point to build our community and take our place as the tollkeepers of the canyon. The resources have provided us with sustenance, feeding our people for millennia. Combined, these things have provided

something special: a spiritual connection to one another and our home.

We are hunters, gatherers, fishers, and trappers. We look for changes in the environment that tell us what we need to know. I am thrilled to see that the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department has created a magazine that showcases our traditional ways alongside our Nation’s stewardship.

I hope you enjoy this magazine and have a bountiful oolichan harvest season.

Thla bois k’m da luh! We are waiting for oolichans!

Message from the Director of Lands and Resources

Welcome to the first edition of Nii, a new magazine produced by the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department! In Sm’algyax, “Nii” means “see” and we couldn’t think of a more appropriate title.

With Nii, we are establishing interactive and entertaining publication that encourages Kitselas community members to participate by sharing their pictures and stories. Nii is not a report, but it will be a way that we can share some of KLRD’s work in a more engaging way.

Like the seasons, the release of new editions of Nii will not fall on the same date year-to-year. However, we aim to release subsequent editions during specific harvests, covering seasonally relevant topics. This edition, Haliisuuah, means the month of the oolichans, and features stories on KLRD’s eulachon eDNA monitoring project as well as some fun facts about mountain goats.

Nii is something we want everyone to see and enjoy a special place for the community to celebrate one another and the bounty that the Kitselas Lahkhyuup provides. In Nii, Readers will see the lands and the resources of the Kitselas Territory, but more importantly, they will see themselves, their friends, and neighbours. As we move forward with new editions, we want you to show off, and I encourage all readers to submit photos and stories and other ideas for us to feature!

Thank you to our extremely dedicated KLRD team, whose hard work forms the basis for some of our features this season. I also want to recognize our other contributors for this edition: Dwayne Riddler, the Seymour Family and Wai Wah Environmental.

2

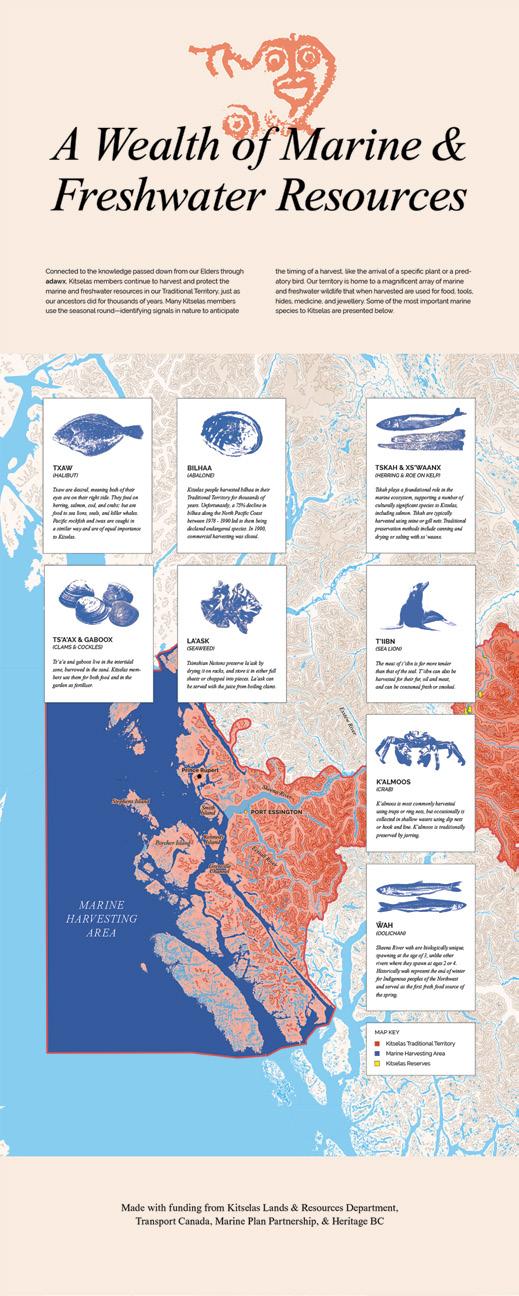

Kitselas Stewardship Education Centre

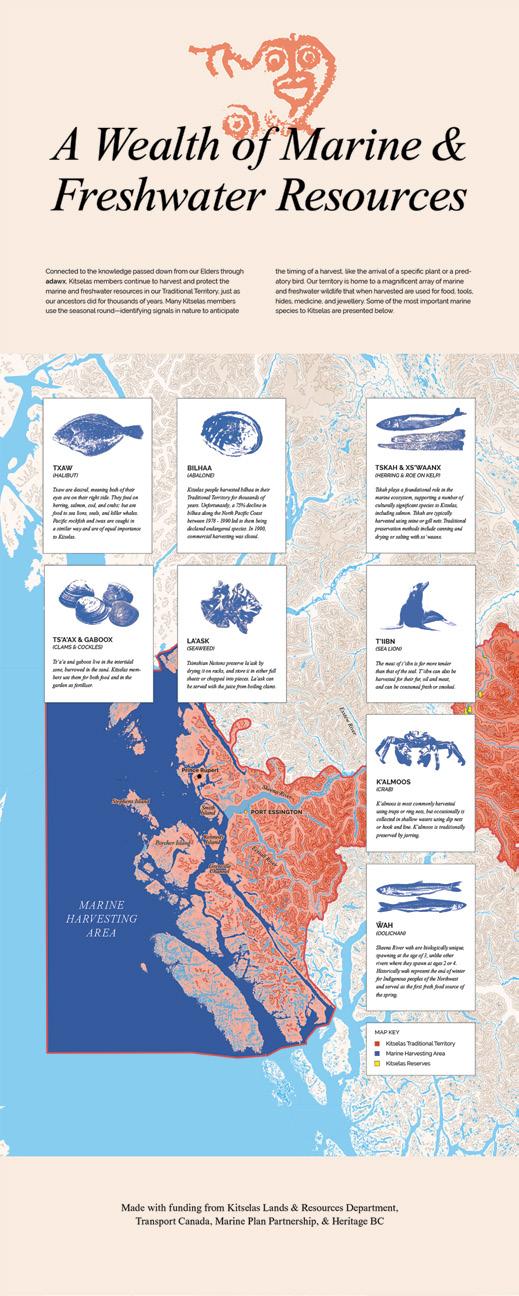

The Kitselas Stewardship Education Centre (or KSEC) is a mobile learning hub. It will make visits to schools, culture camps, and events to foster a deeper understanding of the marine and freshwater environments found within the Traditional Territory. The KSEC will offer immersive learning experiences and interactive activities focused on Kitselas’ connection to the coastal and inland waters. This project works to restore the cultural knowledge lost due to colonization.

The KSEC will be fully launched in 2024 and will be open for bookings for staff to bring the educational experience to learners. All ages will enjoy the experience!

3

The KSEC educational content focuses on five key themes:

Kitselas Culture

Kitselas’ proud history as a Tsimshian Nation, as the guardians of the Skeena River, and the tollkeepers of the Kitselas Canyon.

Salmon Connections

Describing the deep spiritual, cultural, social and economic relationship to Skeena River salmon.

Marine & Freshwater Connections

Showcasing the incredible diversity, productivity, and beauty of the marine and freshwater resources in the Traditional Territory.

Harvesting & Stewardship

Kitselas traditional harvesting technologies were built for sustenance, stewardship, sustainability, and reciprocity.

Rights and Title

Details on Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, a landmark ruling that affirmed existing Aboriginal rights and title, including the right to land, as well as the right to fish, to hunt, and to practice one’s own culture.

4

KSEC learning experiences

The KSEC provides fun and immersive experiences that promote learning about Kitselas culture, stewardship, and biodiversity of the Traditional Territory. KSEC activities include:

Marine Touch Tank

The KSEC touch tank will have several examples of marine plants and animals found in the Traditional Territory. The main aquarium will be housed and cared for at the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department. Smaller touch tanks will be transported in the KSEC for learners to enjoy. Learners can touch, feel, and examine live animals such as crab, sea stars, sea cucumbers, and more!

Traditional Technologies

First Nations have heavily influenced fishing technologies over the centuries. Replicas of many traditional technologies will be used as a teaching tool to introduce learners to cedar bark and spruce root fish traps, halibut hooks and gillnets.

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality is quickly becoming a popular tool to introduce learners to the surrounding environment. Get an underwater view of the Skeena River during the salmon run! Fly like the eagles to the tops of mountains! The virtual reality tool will also showcase short films that span several parts of the Kitselas Traditional Territory and people harvesting cultural resources.

5

Supporting and extending our learning with the KSEC

Curriculum development

We are also developing a curriculum that focuses on Kitselas culture, aquatic resources, and the traditional and contemporary use of those resources. This will support the KSEC educational experience.

Stewardship and traditional knowledge

The KSEC will help promote the marine and freshwater stewardship practices of the Kitselas people. This project can assist in the continuity of traditional knowledge transfer and provide an opportunity for the non-Kitselas community to learn about the Kitselas First Nation.

Example KSEC educational panel

6

Eulachon monitoring

The Skeena River is pulsing with life each year as the return of the Eulachon ushers spring into the valley. Thousands of gulls dip and dive above the river filling their bellies with glistening Eulachon. It is a reminder of the rich history of travel and trade that connects people from the Skeena to the Nass, and the stories of long canoe trips to transport grease to other coastal and upper Skeena communities.

Why monitor the eulachon run?

Once abundant, eulachon is now a species at risk of extinction.

Scientists estimate the Skeena River eulachon population has decreased by 90% since the 1960s. This decrease has greatly affected Kitselas nutrition and cultural practices. It has also reduced a vital food source for many birds, mammals, and larger fish. We don’t understand all of the reasons for the population declines. Habitat degradation, bycatch from commercial fishing operations, and climate change could impact the eulachon. Many First Nations are trying to understand why this has happened and bring the fish back to historic levels.

We are collecting data on the Skeena River eulachon to track how the eulachon run is changing. This research will help us identify the causes of

low (and high) returns. With this information our nation can make well-informed fisheries management decisions so that this resource can remain a part of Kitselas culture for generations to come!

How is the eulachon monitored in the Skeena River?

We collect data on the eulachon run size and timing in several ways.

eDNA

eDNA refers to “environmental DNA” or tiny particles of DNA that organisms shed. We can find these particles in the environment around that organism. Many scientists now use eDNA in ecological studies to determine if a species is nearby and estimate its numbers.

7

eDNA is a powerful and reliable tool for finding both common species and elusive or rare species.

Recently, eDNA has helped determine the run timing and numbers of eulachon in several areas. eDNA has been used in Southeast Alaska to monitor eulachon. The Haisla Nation is using eDNA to monitor eulachon on the Kemano River and other rivers in British Columbia. Because the eDNA technology is non-invasive and does not harm the fish, it is an ideal technology for detecting eulachon in the Skeena River.

In 2022, the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department began a pilot study to test whether we could use eDNA to monitor eulachon in the Skeena River. This study is the first time eulachon eDNA has been collected from the Skeena

eDNA

River to examine the abundance and location of the species. The study sampled the lower Skeena River, mostly between the Khyex River confluence and the Exchamsiks River confluence. Scientists identified a series of key sites to sample eDNA to find eulachon and determine their migration timing.

Our study confirmed that there was eulachon eDNA in the water samples. The data from the samples shows that eulachon entered the lower Skeena River and Khyex River in low numbers in early February 2022. The eulachon eDNA peaked at the Khyex River sampling site at the end of February. There was a peak at all upstream sites in early March, and then a steady decline at all sites by mid-March. We observed the highest peak of eulachon eDNA at Kwinitsa fishing location in early March.

Decomposition Shedding and waste Spawning Predators Our researchers collect water samples from different places and at different times. The eDNA can show there are eulachon nearby even if we can’t see the fish. eDNA or “environmental DNA” is tiny particles of DNA that exist in the environment. For example, eulachon DNA can be found floating in water where

swimming. Scientists can sample the water to find traces of eulachon

eulachon are

and Eulachon Eulachon DNA enters the water from: Everything that lives in or near the water adds eDNA to the water 8

Fish were being harvested at this location when eDNA was sampled. To our surprise, we detected eulachon eDNA as far up the Skeena River as the Exchamsiks confluence.

Right now, we don’t know how early eulachon arrive in the lower Skeena River. We also don’t know what affects the timing of the eulachon entering the river. But the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department has secured funding to continue the eDNA work and uncover answers to these questions.

Predator Abundance

Eulachon are an essential part of the food web, both in the river and at sea. Eulachon feed on plant and animal plankton (e.g., krill), other invertebrates, larvae, and fish eggs. In return, eulachon provide a food source for a wide variety of animals. At sea, eulachon are eaten

by deep-water fish, porpoises, seals, sea lions, and a few species of whale. Eulachon in the river are eaten by many birds and mammals. Common bird predators include gulls, terns, ducks, eagles, ravens, crows, and cormorants. Common mammal predators include otters, seals, sea lions, and wolves. A gathering of predators is a good sign eulachon are nearby.

Since 2018, the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department has been monitoring predator numbers in the Skeena River. We conduct yearround, monthly land- and vessel-based surveys of marine mammals and birds. We increase the number of our surveys in February and March alongside the eulachon run. The survey data will help us track how mammal and bird numbers change over time.

A scientist uses an eDNA sampler backpack. The backpack pumps water from the river through a small filter. After the sampling is finished, the filters are removed from the backpack and packed up. Then these filters are shipped to a laboratory for eDNA analysis.

9

year-round average number of seagulls

The bar chart shows the 2019 predatory bird survey results, which covers 12 days between February and March. We gathered the data at 13 land-based locations along the Skeena River. The horizontal line represents the average gull numbers over the entire survey period. The number of gulls varied in February but showed a gradual increase over time. Gull numbers peaked on March 5th. After this, there was a gradual decrease. The observations of gull activity might be linked to eulachon run timing and abundance.

Eulachon Catch Monitoring

Watching gull activity during the 2019 predatory bird survey

Catch monitoring for eulachon is very important to gather information on how the species is doing. Here’s how you can help:

1. Pick up Eulachon Monitoring Tool booklet from our offices for free.

2. Record the number of totes/buckets you caught, along with the time, place, weather and water conditions.

3. Return the data cards to the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department.

You may also give your catch information to our Kitselas Fisheries Technicians when you see them monitoring the run!

The data you provide will be used to inform national and provincial fisheries policy and help guide future research in the Traditional Territory. We will communicate all results back to the community so everyone can better understand the trends in the eulachon population. Our monitoring program will help us more effectively manage the species for the future.

200

800 1000 1200 1400

Feb 15 Feb

22

0

400 600

1600 13

21 Feb

Feb 28 Feb 1 Mar 5 Mar 8 Mar 14 Mar 19 Mar 21 Mar 3 Apr

Seagull observations during the Eulachon run

10

Our future monitoring goals

The Kitselas Lands and Resources Department plans to conduct a coordinated and ongoing data collection program. This will give us specific details about how eulachon are doing right now, and what the conditions are in the estuary and instream waters within the Kitselas Traditional Territory. This information will be our “baseline dataset” which we will enhance with eDNA sampling to confirm eulachon abundance, distribution, run timing, and spawning. Our goal with this program is to improve our understanding of eulachon migration and habitat use.

All results will be communicated back to the community so everyone can better understand the trends in the Eulachon population.

Eulachon Monitoring Tool

You can participate in monitoring the run, and help protect and sustain this important species!

Last year the Kitselas Lands and Resources Department launched a new Eulachon Monitoring Tool for community members. This is a short booklet with two sections: an educational section and a monitoring section.

The first section has information on eulachon’s biological, cultural, and ecological importance and provides a guide to eulachon predators. The second section has a field guide, maps of important monitoring locations, and tearaway monitoring cards.

We encourage you to bring your Eulachon Monitoring Tool when you go out fishing, or just to observe the run! Complete the included cards with your catch information and/or observation of predators.

11

FUN FACTS FOR ALL AGES

Mountain Goats!

They’re not really goats!

They are from another branch of the same family, known as “goat-antelopes.”

Takin Relatives

They’re unique to this area!

Mountain goats only live in western North America. Their ancestors probably came from central Asia.

in Europe in Asia

These species also live on steep, rocky cliffsides and mountains.

Life Cycle

Mountain goats mate in the late fall, mostly during the month of November.

Males will travel huge distances, visiting multiple winter ranges to find females. Males compete for dominance with aggressive posturing and sometimes fighting.

A male will burn much of his fat reserves looking for a mate in the winter. This leaves him with relatively little fat to last the winter when the mating season is over.

Females give birth in late May or early June, usually to one baby, called a “kid.” Each year up to 40% of adult females do not produce a kid.

Mountain goats usually live in two groups: females and young in the “nursery group” and adult males in the “bachelor group.” The females are the matriarchs and lead their herds as a matriarch elephant does.

Scientists believe they came to North America 40,000 years ago by the Bering land bridge.

Few mountain goats live past 12 years, but one is reported to have lived for 18 years.

Map: Festa-Bianchet and Côté 2008

All photos courtesy of Dwayne Ridler

Chamois

Map: Festa-Bianchet and Côté 2008

All photos courtesy of Dwayne Ridler

Chamois

12

Mountain goat hooves are made for climbing steep, rocky cliffs in all weather.

Each hoof is split in two, which means they can spread or contract to fit the terrain. The hooves have a soft, grippy texture on the bottom so they won’t slip on icy or wet rocks.

wool

Mountain goat horns can grow as long as 30 cm and are very sharp and dangerous. They are known to use them to gore predators or humans who threaten them.

Mountain goats grow a thick, heavy winter coat to survive the cold winters in the mountains.

The coat is made of two layers: an inner layer of thick, soft wool 5 to 8 cm long; and an outer layer of coarse guard hairs which can be up to 20 cm long. These guard hairs give them their well-known shaggy winter look.

Summer coat Winter coat shedding

A newborn mountain goat can begin running and climbing a few hours after birth!

13

The shed

has traditionally been gathered and woven by many First Nations people in BC and Alaska.

Predators

Predators of mountain goats include both grizzly and black bears, as well as cougars, wolves, and wolverines. Golden eagles have also been seen to prey on mountain goats, even in areas close to the Kitselas Traditional Territory.

Mountain goats generally live in areas that are hard to get to, but they are very sensitive to hunting and predation. In fact, if hunters or predators continually stress a population, the females will stop reproducing.

Mountain goats will stand up for themselves against predators and can even kill them. In 2021, a mountain goat in Southeastern BC killed a grizzly bear by goring it with its horns.

Mountain goats have a preference for steep, treacherous cliff areas. They often live high up in the mountains, but some are also found in low valley canyons and in some forested areas near the ocean.

Mountain goat groups have a “home range,” which covers a large area. They migrate around within it throughout the year.

This means that mountain goats sometimes will cross large valleys to access other mountain ranges. They have been seen passing through small mountain towns such as Smithers BC and crossing treacherous rivers. Mountain goats have even been witnessed walking on beaches in certain coastal areas of BC.

In the summer, the nursery groups usually travel much farther than the bachelor groups. However, there have been records of individual males travelling as far as 75 kilometres from their home range.

Mountain goats are herbivores, which means their diet is entirely plant-based. A study in Southern Alaska observed mountain goats eating over 80 species of trees, shrubs, and many other types of plants, including lichens.

Near the BC coast, mountain goats will spend the winter and spring in steep forested areas near or on cliffs within the alpine treeline. Mountain goats that live closest to the coast can spend their winters and spring within a few hundred feet of the ocean. The snow is too deep in the coastal high alpine areas for these goats to access plant food. However, sometimes coastal mountain goats will travel up high in the alpine to feed where the snow is shallower due to high winds.

In the BC Interior, such as in the Babines, mountain goats will stay in the alpine during the winter. The snow is usually much shallower in these areas, allowing the goats to access their food sources more easily.

14

Habitat and food Not food Delicious!

Dwayne Ridler

Mountain goats will go to great lengths to get a tiny bit of salt

Human impacts

If you encounter a mountain goat, you should stay at least 50 metres away. Mountain goats can be aggressive if they feel threatened, and their horns can be very dangerous. In 2010 a hiker in Washington State was killed by a mountain goat.

Mountain goats will travel long distances to visit natural salt licks. But in Washington State, some mountain goats started licking urine left behind by hikers because of the salt content! These mountain goats started following people and sometimes chasing them. They would also try to lick clothing and any other sweaty items. The One-Horned Goat

The taste of mountain goat meat has a dubious reputation. However, many people in BC regularly eat it and say the meat is quite tasty. Mountain goat meat can be very tough, so it is usually ground into burger, made into sausage, canned, slow-cooked, dried or even aged.

Many populations of mountain goats, especially in southern BC, have become extinct in the last century due to overhunting and industryrelated activities.

Mountain goats are found in many local First Nation oral histories. Walter Wright, Chief of the Grizzly Bear People of Kitselas, tells the story of L-La-Matte, the Feast of the Goats, in the book Men of Medeek. Some of the oral histories speak to rigorous systems to manage the hunting of mountain goats. These management systems have worked for millennia to continue the existence of local mountain goat populations.

•

•

Photo: Mountain goat licking a handrail for the salt left behind by sweaty human hands. (mining, logging, etc) •

Avenue / Wikimedia

Mountain goats are impacted by:

Overhunting

Industry

Climate change

15

AnetteWho / Flickr

Participate in our Elder Connections series

This is an opportunity for youth to connect with Elders in their family by interviewing their family members and learning from them. We are providing the platform of this article series to demonstrate knowledge transmission from one generation to another.

Are you interested in writing an article for this series?

We are looking for Kitselas youth under 25 who would like to interview their elders and write about that experience in their own words. We will provide the cost of a one-time meal to facilitate the interview.

We are looking for writing with a minimum of 500 words and a maximum of 1200 words for the article.

Suggested questions for your elders:

• How have you experienced material/processing change in harvesting traditional foods in your family?

• How have you experienced seasonal changes in the timing of harvesting?

• How have our cultural ways experienced change for the better/worse?

• What hopes do you have for your family or for Kitselas?

• Development on reserves: What amenities do you hope for on reserve?

• Knowledge transmission: What is the best way for younger generations to learn about Kitselsas Land Connections?

We recommend providing a sheet with these questions to each elder after the interview. If they forget to mention something and want to include it, they can write down their thoughts later.

Please contact Cedar Welsh, LR.Manager@kitselas.com, if you would like to participate!

The next issue of the magazine will be published in the summer.

16

As our Nation fights to revitalize the traditional “Kitselas Way,” Seymour matriarchs provided clear information during an interview on how their cultural ways have changed, and their hopes for upcoming generations.

ELDER CONNECTIONS SERIES: SEYMOUR FAMILY

The Kitselas Way: all about community

by Madison Seymour

by Madison Seymour

We are losing our elders, and with that, we are losing our knowledge and protocol, our history: our ways. Our resources are dwindling, bringing uncertainty for years to come. It is prevalent that not as many younger family members are involved in traditional and cultural practices such as hunting and harvesting, cleansing, and protocols (alongside many others). Fewer members are able to hunt or harvest seafood and if they are, they have lost touch with the cultural practice of sharing. This leaves the rest of their family relying on food sellers.

Growing up, we were taught to give and share; “If you give, you will get back in return.” Your wealth and status were measured in how much you gave to those who were in need. Oftentimes, the universe would return the favour by bringing more supply to your family. It is these protocols that have been lost in recent years. Can we blame it on the Covid pandemic, or are families drifting apart and losing the sense of who they are because we lost our elders?

17

It is no secret that our elders have gone through many traumas, leaving them scared to instill knowledge into their children and grandchildren. The knowledge that was shared was vital and cherished. For instance, the late Rhoda Seymour made sure each of her children were included in the harvesting of fish each year, leaving them to pass on family ways and recipes. Rhoda and Willard Seymour both passed down guidance and knowledge that they were taught. Although these conversations were informational, very few could be relied on or implemented in today’s society. With climate change, it is harder to use seasonal indicators of harvesting times. A well-known indicator of Eulachon is snowflake density. This snowfall was a signal of the run about to start. The wetness, size, and time all contribute to this seasonal gauge used for many generations. Even though this snowfall arrives each year, the eulachons are becoming delayed, much like the fish we harvest during summer. Our climate has become unpredictable, our rivers are becoming polluted and dry of resources. We have fewer fish than, say, 10-15 years ago, and we are seeing more fish being infested by parasites and growths. Late June used to be the peak for fish harvesting, and now we can expect this run to be around 3 weeks late. Due to the change in climate, vegetation is scarce and hard to grow and maintain. Construction and development increase leads to seeing less wildlife and habitat within our regions. Since there is a noticeable decrease of access to disappearing wildlife species, such as moose, hunting has become more challenging and timely, and the wildlife are becoming harder to find. A common worry amongst parents and grandparents is access to these resources that our culture heavily depends on. Will our children’s children enjoy these rich foods? Will they know how to preserve and where to harvest? Can they utilize the Traditional resources in our Territory? Our culture is endangered, and we need to ensure that we revitalize the Kitselas Way so our

ever-growing families can cherish and indulge in the same resources we were able to.

Our youth need help reconnecting to who they are. They identify with other societal cultures before their own, such as hip-hop. There is limited access for our youth to rekindle the love and acknowledgment of our ways. Our elders have passed down many valuable teachings, but unfortunately, many parents do not feel confident enough in their memories and understandings to pass on some knowledge. This leads them to rely on the very few elders we have or to guess. They know enough to carry on traditions but not enough to revitalize. When this family was younger, they had delegated tasks at a young age; they had to keep the fire smouldering, collect leaves to cover the fish, bring water for cleaning, and had a helping hand in the preservation process. Today, very few youth and adolescents take part in this tradition. An immediate fear of losing the family’s bologna fish recipe swooped over during this interview. “I know that if anything were to happen to me, my kids will have their aunts to rely on” — but if our youth continue to rely on our elders and matriarchs, they won’t be fully confident in their skills by the time they are the elders and matriarchs of our community.

Introducing more workshops and tours, similar to Culture Camps, will intrigue the generations

18

of today. A traditional wellness center or a traditional foods restaurant to get not only the kids but the adults who lost touch with their culture interested and excited about revitalizing. Nowadays, children are involved in many different extracurriculars that pull their attention in all different directions. Kids do very well with learning through osmosis which leads us to questions: are they learning more than we realize? Could we possibly integrate our culture into these activities that they are drawn to? Exposing our children to our practices in a way that excites them won’t be challenging. This family mentioned a traditional wellness center, which could teach our children to smudge, prepare, heal, protocols, and how to be prideful in being from Kitselas: teaching them our history.

Growing up, these interviewees mentioned their parents being able to go walk into the forest or along the river and grab something edible from the land. Norma Joseph recalled a memory of when her late father, Willard Seymour, climbed up a rock along the Kleanza Creek and grabbed what he called “liquorice root.” He then talked about how he would use it to keep him awake and to help with anxiety. This was not the first time their parents showed them what they can and cannot eat off the land. Today, we all depend on outside food sources and many do not know what is edible. Thanks to Chelsea Armstrong’s recent book, Silm Da’axk,

we are steps closer to reconnecting to the land our people come from.

Our elders have held our families together for the many generations we had with them. Unfortunately, we did not have enough time, talks, or guidance; there is no measure of “enough time” with our knowledgeable loved ones. It is imperative we soak up and learn as much as we can. One day, all we will have left to lead with is our memories. This is our time to stop the effects of colonization within our families and revitalize our cultural ways of language, protocol, respect, and our lands and resources.

The objective of this interview was to understand how culture and harvesting has changed within the author’s family. The author wrote everything in this article based on their personal experiences and opinions.

19

From the Community Dwayne Ridler

The snow-capped mountains in the background of the picture are framed in by the closer ridges of the Seven Sisters peaks. Where I took the shot you could stand at the source of the Legate creek watershed, the North Kleanza source and the most remote beginnings of the Chimdemash creek source.

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

20

Photos

A grey wolf at the headwaters of the Chimdemash watershed, about 4,700 ft elevation. He was in pursuit of the whistlers in the area and I watch him make his attempt on the denning area but he came up short on his effort. I’ve seen him in the same area when the snow was in the meadows earlier that year.

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

Chimdemash mountain, looking east up the Valley. Mount O’Brien is in the background, and the head waters of the Chimdemash valley. I’ve been told and believe some of the Kistselas elders used to goat hunt the range in the past: Ray Seymour, Mike Banek, Harry Ridler and many others.

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

21

2225 Gitaus Rd • Terrace, BC V8G 0A9 • 778-634-3517 kitselas.com

Map: Festa-Bianchet and Côté 2008

All photos courtesy of Dwayne Ridler

Chamois

Map: Festa-Bianchet and Côté 2008

All photos courtesy of Dwayne Ridler

Chamois

by Madison Seymour

by Madison Seymour

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler

- Dwayne Ridler