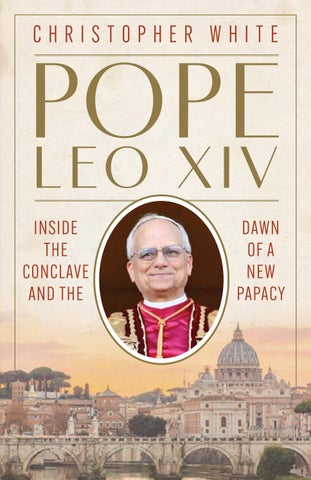

POPE LEO XIV

INSIDE THE CONCLAVE AND THE

DAWN OF A NEW PAPACY

I

NS I D E THE CONCLAVE AND THE DAWN OF A NEW PAPACY

“Christopher White embodies what a great Vatican reporter must be: wellsourced to provide inside knowledge but with a keen journalistic, outsider’s eye for detail. In print and on television, he makes the complex ecosystem that is the Catholic Church understandable, which makes him the perfect author to craft the absorbing story of Pope Leo XIV and the riveting conclave that elevated him.”

—Chris Jansing, anchor of Chris Jansing Reports on MSNBC

“There is no better source than Christopher White to find out what is happening at the Vatican. White has earned a reputation of trust, based on fairness, hard work, and character.”

—Joseph Donnelly, former United States Ambassador to the Holy See

“Christopher White is my go-to Vatican expert—an experienced reporter whose writing on the Catholic Church is nuanced and deeply considered.”

—Christine Emba, the American Enterprise Institute and The New York Times

“Christopher White is an exceptional Vatican journalist because he is indefatigable as a reporter, exceptionally well-connected, and learned about the Catholic Church, Christian theology, and the role of politics inside and outside the church. That’s why so many have relied on him and appreciate his work.”

—E. J. Dionne, The Washington Post and The Brookings Institution

“As a reporter, Christopher White has demonstrated his ability to render accessible even the most opaque complexities of the Vatican. A trusted, prescient correspondent, White is a treasure for those eager to understand the influence, impact, and importance of the Catholic Church.”

—Kerry Alys Robinson, president and CEO, Catholic Charities USA

“Christopher White’s incisive reporting on the Vatican gives readers unparalleled insight and access into the highest levels of the church, along with the keen insights and invaluable observations that could come only from an expert like him.”

—Jesuit Fr. James Martin, editor-at-large of America magazine

At the threshold of history, Pope Leo XIV appears on the balcony of the central loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica.

May 8, 2025

I

NS I D E THE CONCLAVE AND THE DAWN OF A NEW PAPACY

Copyright © 2025 Christopher White All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations are from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America.

Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

Cover art credit: (t) ALBERTO PIZZOLI/Contributor/AFP/Getty Images; (b) Alexander Spatari/Moment/Getty Images; (bg) fotograzia/Moment/Getty Images.

Interior art credit: p. ii Stefano Spaziani

Back cover author photo: Brittany Buongiorno.

ISBN: 978-0-8294-5947-0

Published in Chicago, IL

Printed in the United States of America 25 26 27 28 29 30

Preface A Hornet’s Nest: The Most Important Conclave in Sixty Years

WHILE MOST AMERICANS HAVE gotten used to hearing that the next presidential election is “the most important in the history of the country,” the same can’t exactly be said of papal elections, which go back two millennia. But before 133 cardinals entered the Sistine Chapel on May 7, several had told me they believed that the conclave of 2025 might be the most important in at least sixty years.

Pope John XXIII’s death on June 3, 1963, from stomach cancer at age eighty-one, presented a time of testing for the Catholic Church. Just one year earlier, the pope had presided over the opening of the Second Vatican Council, a landmark event in the history of Catholicism. This council promised to open up the Church to the modern world. To give this ambitious project context: The war in Vietnam had been grinding on for nearly a decade; Martin Luther King Jr. was leading the crusade for civil rights in the United States; and the threat of nuclear destruction loomed large. The Church was wrestling with the existential question of what role it was to play in a rapidly changing world.

When the council was announced on January 25, 1959, the news sent shockwaves through Rome and beyond. Councils are rare in the life of the Church. At the time of what would come to be called Vatican II, there were only twenty previous councils, and each was marked by both great promise and great trepidation. Speaking to nearly 2,500 bishops from all over the world at the start of the council in 1962, Pope John said that it was time for the Church to “look to the present, to the new conditions and new forms of life introduced into the modern world which have opened new avenues to the Catholic apostolate.”1 While many past councils, often concerned with suppressing potential heresies that arose in Catholic life, had been inward looking, the Second Vatican Council was decidedly outwardly facing.

During its first session, debates centered on renewing Catholic liturgy; how the laity might become more active participants in the liturgy; and whether Latin should remain the universal language or could the Mass be celebrated in the local vernacular. Discussions were also held on the Catholic Church’s stance toward other Christian churches, the relationship between the Church and secular society, and more.2 Beyond dealing with the particular issues, the council introduced a new style of operating within the Church. Bishops were speaking more frankly, drawing from their own experiences and backgrounds; theologians were integral participants in the debates; and representatives from other Christian churches were invited to be present in Rome.

1. Pope John XXIII, “Solemn Opening of the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council,” October 11, 1962, www.vatican.va/content/john-xxiii/it/speeches/1962/documents/ hf_j-xxiii_spe_19621011_opening-council.html.

2. Joseph Ratzinger, “The Second Vatican Council: The First Session,” The Furrow, vol. 14, no. 5, May 1963.

As one observer wrote after the first session, “I hadn’t realized that anything like this existed. I thought the Roman Catholic Church was a very closed, complacent and sectarian body that had nothing to learn from anybody else. I know that this is no longer accurate, if it ever was . . . the whole atmosphere is so different that, as Cardinal Bea says, it is a ‘real miracle.’ ”3

All of that was at stake following the death of Pope John early in the summer of 1963. Would the cardinals elect a new pope who would push ahead with the council as well as with the reforms it had set in motion? Or would they reverse course, afraid of the possibility that decades or even centuries of tradition could be undone? The conclave of 1963 would challenge all of this, leading The New York Times to declare that “in modern times, there has never been a papal election so important as that which starts in Rome tomorrow.”4

On June 21, 1962, when Giovanni Battista Montini emerged from the conclave, taking the name Pope Paul VI, it sent a signal that the reforms set in motion by John XXIII would continue. The former cardinal of Milan had been an ally of John XXIII and, though different in disposition (John XXIII had a winsome, extroverted, sometimes even comical personality compared to the more sober, contemplative Paul VI), Montini had been deeply engaged in the first session of the council. Even so, despite his support of the larger project, he knew the council would lead to a reckoning for the global institution. In fact, the night the council was first announced, Cardinal Montini called a friend and is said to have said of Pope John, “This holy old boy doesn’t realize what a hornet’s nest he’s stirring up!”5

3. Ratzinger, “The Second Vatican Council.”

4. C. L. Sulzberger, “The New Pope—Two Types of ‘Liberal,’ ” The New York Times, June 19, 1963, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1963/06/19/89537628.pdf.

5. Father Patrick Briscoe, “Through Study and Prayer, It’s Not Too Late to Get Vatican II Right,” Our Sunday Visitor, December 7, 2022, www.oursundayvisitor.com/throughstudy-and-prayer-its-not-too-late-to-get-vatican-ii-right/.

Fast forward to the end of the Francis papacy, when some of the pope’s own cardinals had begun to characterize it in similar terms, sometimes using even more pointed descriptions. Two examples will suffice: First, before his death in 2023, Cardinal George Pell had penned a secret memo labeling the Francis papacy a “catastrophe,” and was actively promoting candidates who would bring back an era of law and order to the Vatican’s governance.6 Second, there was the former head of the Vatican’s doctrinal office, German Cardinal Gerhard Müller, who went even further in his public criticisms, implying that Francis might have drifted into heresy for allowing priests to offer blessings to couples in same-sex unions.7

Yet for Francis, his entire papacy could be seen as trying— albeit fifty years later—to implement the reforms of the council initiated by Popes John XXIII and Paul VI, both of whom would be canonized during his papacy. The Second Vatican Council had unleashed tremendous change in the life of the Church. Among its landmark reforms were the greater participation of the Catholic laity in the life of the Church, the start of a new era in the Catholic Church’s relationship with other religions, and a deepened commitment to religious liberty and pluralism. The council explicitly called for a style of governance that was meant to be more collegial. Above all, the council committed the Church to be more engaged with the world around it. And yet the council’s embrace of these initiatives had been sluggish, met as they were with internal resistance and two popes who sustained a narrow understanding of the council’s aims. In his first major document as pope, Francis turned to the

6. Nicole Winfield, “ ‘Catastrophe’: Cardinal Pell’s Secret Memo Blasts Francis,” Associated Press, January 12, 2023, https://www.ncronline.org/vatican/vatican-news/catastrophecardinal-pells-secret-memo-blasts-francis.

7. Cardinal Gerhard Müller, “Does Fiducia Supplicans Affirm Heresy?” First Things, February 16, 2024, https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2024/02/does-fiduciasupplicans-affirm-heresy.

council and anchored his own papacy in its call for an “ecclesial conversion as openness to a constant self-renewal born of fidelity to Jesus Christ.”8

In the twelve years that followed, Francis pursued that vision by radically reorienting the Church’s priorities. He demonstrated his commitment to this reorientation in several ways: by redirecting the Church to focus less on sexual ethics, while at the same time showing equal commitment to the needs of migrants and refugees and those facing environmental disaster; by putting women into high-ranking positions of power in the Vatican for the first time ever; by dismantling the papal court that had long defined the institution; and by launching a global process meant to invite Catholics around the world to bring their joys and anxieties with the Church so that the Church might find a better way to listen to them. Outside the Church, these changes were overwhelmingly greeted with thunderous applause. Like Pope John XXIII, Francis was named “Person of the Year” (in 2013) by Time magazine, which hailed him as “the people’s pope” for his courage in changing the often archaic and antiquated institution.9

Inside the Church, a hornet’s nest had been disturbed. In 2025, just as had been the case sixty years earlier, the cardinals were effectively facing a referendum on whether to continue down an established path. It’s not often that “never has a papal election so important” happens twice in one lifetime. But on May 8, when Pope Leo XIV was elected to succeed Francis, it was clear that history seemed likely to repeat itself.

8. Pope Francis, Evangelii Gaudium, November 24, 2013, https://www.vatican.va/ content/francesco/en/apost_exhortations/documents/papa-francesco_esortazioneap_20131124_evangelii-gaudium.html.

9. Howard Chua-Eoan and Elizabeth Dias, “Pope Francis, The People’s Pope,” Time magazine, December 11, 2013, https://poy.time.com/2013/12/11/person-of-the-yearpope-francis-the-peoples-pope/.

PART II

Inside the Most Secretive Election on Earth

“The pope is dead. The throne is vacant.”

THESE ARE THE OPENING lines of the trailer for Conclave, the 2024 Hollywood thriller where film greats Ralph Fiennes, Stanley Tucci, and John Lithgow played cardinals wrestling with faith, secrets, and backroom dealings over the course of the election of the next pope. Now life was about to imitate art.

The film may have been fictional, but it provided much of the world with an inside look at the most clandestine election process of any head of state on earth. Even the name of the exercise hints at mystery—conclave literally means “with key,” a nod to the fact that, historically, cardinals are locked into a room together until they select among themselves the next pontiff.

The period between the death or resignation of a pope is known as sede vacante, meaning “the seat is empty.” During this time, cardinals from all around the globe travel to the Vatican to begin a series of meetings in anticipation of entering into conclave. While the eyes of the world are on Rome in these critical days, these meetings are private conversations where cardinals have open, free-ranging discussions on the needs of the Church and the world as well as who they think might be best positioned to lead the Church at this time. It is also a time when cardinals have frank conversations about the legacy of the last pope and offer opinions on what he did well, what should be continued, and what needs improvement.

“No sane man would want the papacy,” declares Stanley Tucci’s character, Cardinal Bellini, in the Conclave film.

For the most part, that’s true, even if the history of papal elections tells a more complicated story.

The Papacy and a Battle for Power

“Many papal elections involved violence, chicanery and corruption on a grand scale,” is how historian Jeffrey Richards describes some of the earliest contests over who became the bishop of Rome. “Blood ran in the streets of Rome, gold changed hands in the corridors of power, rival factions pumped out propaganda and ambitious men caballed around the deathbeds of the popes.”1 While blood or bribery hasn’t been a part of recent papal elections, even today the shrouded mystery of what happens before and during a conclave continues to grip the world.

For nearly one thousand years after Christ, popes were primarily chosen by the clergy and the laity (as were the bishops of most dioceses around the world). Catholic tradition recognizes Saint Peter, about whom Jesus pronounced, “Upon this rock I will build my Church,” as the first pope, and the Vatican is the hill where the remains of the apostle Peter were buried. Over the centuries, however, the process for selecting a pope became more formalized, with the creation in 1059 of the College of Cardinals, the body responsible for electing a pope. The rules that resemble the current rubrics for selecting a pope were established in the thirteenth century, but they came about after a now infamously messy papal election.

The year was 1268 and Pope Clement IV had just died after a brief but consequential three-year papacy, for which he is remembered as a crusader against corruption. The cardinals gathered in Viterbo, Italy, just north of Rome and where Clement IV had died, and set out to elect the next pope. There were twenty cardinals at the time, which is a far more manageable number than the

1. Jeffrey Richards, The Popes and the Papacy in the Early Middle Ages, as cited in Michael Walsh, The Conclave: A Sometimes Secret and Occasionally Bloody History of Papal Elections (Lanham, MD: Sheed and Ward, 2003), 1.

135 cardinal electors that were eligible to participate in the 2025 conclave, but it soon became clear that it would be impossible to come to a consensus.

For 1,006 days the See of Peter was vacant as the cardinals sat inside what is now known as the Palace of the Popes trying to elect a new one. When the election stretched out beyond two years, the townspeople had had enough and decided to take matters into their own hands. Their first effort was to reduce the cardinals’ rations to only bread, water, and, of course, wine and then lock the cardinals inside the palace to force them to reach a decision. When that failed to work, an even more extreme measure to hurry a decision was taken: The roof of the palace was removed so that the cardinals were exposed to the elements.

After nearly three years, when history’s longest papal election reached its conclusion, newly elected Pope Gregory X decided it was time to establish new rules for papal elections. Among those norms were requiring cardinals to live together in isolation during the election of a new pope, making cardinals cast their votes in person, and forbidding cardinals to participate in any bribery or politicking during the election process.

Immediately following the death of Pope Francis on April 21, 2025, cardinals and journalists began to make their journeys to Rome, although with wildly different priorities in mind. Some cardinals had been preparing for this moment for years, as when they spoke with their close cardinal friends at dinner parties during regular trips to the Vatican, some of whom had been plotting and waiting to wrest the papacy from Francis. However, others coming from the far reaches of the globe had been to Rome on only a handful of occasions and spoke no Italian. Navigating the days ahead would be a very different experience for these clerics. While we vaticanisti spend our whole lives covering the pope and preparing

for who might come next, other journalists dispatched to Rome are coming from war zones or from places where they’ve been covering natural disasters and are forced to become overnight experts on one of the most antiquated institutions and election processes on earth. Regardless of our background, however, each of us was presented with one document upon our arrival in Rome: a slender booklet printed by the Vatican’s publishing house, distinguished with gold and black lettering on the cover that reads Universi Dominici Gregis, Latin for “The Lord’s Whole Flock.”

The fifty-five-page document, officially a constitution that was written in 1996 by Pope John Paul II and modified in 2013 by Pope Benedict XVI, still governs how a pope is elected. For some cardinals and reporters, this was their only roadmap to guide them through and help them know what to expect in the days to come. Today, in order to be eligible to participate in a conclave, cardinals have to be under the age of eighty years old at the time of the death or resignation of a pope. When the cardinals enter the Sistine Chapel, the door is shut behind them after the Master of the Papal Liturgical Celebrations proclaims the words, Extra omnes!, which is Latin for “Everyone out!” During the election process, the cardinals are sequestered at a Vatican guesthouse and are completely shut off from the outside world, which means that all of their computers, phones, and tablets must be locked away for the duration of the conclave. Beneath Michelangelo’s stunning sixteenth-century frescoes, a total of four votes typically take place each day. As each cardinal elector writes down the name of their preferred candidate, they are swearing before God that they are casting their ballot in favor of the person they believe to be best suited for the job. And just to add to the drama, they do so while staring at Michelangelo’s painting of The Last Judgement, with graphic scenes of saints ascending to heaven and sinners being

damned to hell. Afterward, the ballots are burned. The outside world keeps a close eye on the chimney, for black smoke rising indicates no pope has been elected, while plumes of white smoke signal an election has occurred.

It takes a supermajority—two-thirds—to elect a pope. This rule was put into place to force the candidates to decide on someone not just as a compromise, but to arrive at as much of a consensus as possible. After a candidate reaches that threshold and accepts the job, they are then vested with the full authority of the papacy. The new pope is then asked, in Latin, “By what name shall you be called?” When Francis became the first pope to ever take the namesake of the thirteenth-century saint who renounced wealth and privilege, he did so in part because a close cardinal friend of his had whispered to him right after his election, “Do not forget the poor.” The new pope is then taken to a small room off the Sistine Chapel, where white robes in sizes small, medium, and large await him. This room is known as the “Room of Tears” because it is the place where newly elected popes are left to process in private the weight of their new office. After he has had this time alone, the new pope greets each cardinal one by one, and then it is off to the loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica to greet the many thousands who have come to hear words that echo around the globe: Habemus papam.

“We have a pope.”

But while those may be the official rules that govern a conclave, there are other unofficial rules—or at least local lore—that shape many of the discussions both inside and outside the Vatican when it comes to papal elections.

In his 1995 book, The Next Pope, longtime Vatican watcher Peter Hebblethwaite set out to identify lessons from past conclaves that could help make sense of future ones. Thirty years later his wisdom still holds up.

Hebblethwaite’s advice is succinct:

• don’t elect a sick pope;

• don’t elect a theologian—he will be unable to leave theology to others;

• the cardinals do not always get what they bargain for— they elect a man on one set of assumptions, only to find he does something completely different; and

• cardinals, even when created by the pope just deceased and on the whole admiring him, do not necessarily vote for someone in the same mold.2

To this day, age continues to be a major focal point in papal elections. When Pope Benedict XVI resigned in 2013, becoming the first pontiff to do so voluntarily in more than 700 years, he cited declining physical health as limiting his ability to keep up with the demands of the job. During the conclave that elected Francis, many people had written off the prospect of Cardinal Bergoglio becoming pope because they feared that at seventy-six he was already too old for the job. Few would have imagined the twelve-year papacy that followed, not least because Francis himself often predicted that his would be a short pontificate. This same debate roiled the conclave of 2025: Should, or could, the cardinals dismiss certain viable candidates because they were either too young or too old? The memory of Pope John Paul II’s almost three-decade papacy still haunts many cardinals, given that his final years left him unable to govern and the papacy in effect was managed by his top aides. It is a great gamble to give the lifetime

2. Peter Hebblethwaite, The Next Pope: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Forces That Will Choose the Successor to John Paul II and Decide the Future of the Catholic Church (New York: HarperCollins, 1995), 27–47.

appointment of the papacy to someone in their late fifties or early sixties, who, with the advancement of modern medicine, could reign for another quarter century.

Being a great theologian may boost one’s profile in Church circles, with much-discussed works of theology leading to lecture invites that take cardinals all over the globe, thus providing opportunities to get to know fellow Church leaders. But this doesn’t necessarily translate into leadership abilities. German Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was a prolific and highly praised scholar who served as Pope John Paul II’s doctrinal chief and right-hand man, and thus was viewed by many as a natural successor. When he became Pope Benedict XVI, he brought with him the great intellect that had fueled his ascendancy inside the Church. But upon landing the top job, this cerebral talent proved to be one of his real limitations. He often seemed aloof and unable to connect with average people. He may have been a great professor, but as has often been noted, it seemed as if the classroom was empty or, at the very least, the students were not engaged.

And after almost forty years of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI remaking the Catholic hierarchy with men who reflected their top priorities and styles, it seemed most probable in 2013 that a candidate would emerge among the cardinals who came from a similar mold. Instead, they opted for an outsider—someone who had never worked in Rome and, beyond that, the first ever Jesuit and first Latin American to be elected to the chair of Peter. He brought with him a singular way of doing things, insisting that rather than emphasizing doctrine, the Church had to be better at dialoguing with the world around it, particularly with those inside the Church who were living on the margins. This radical pope was not what many, including those who cast their ballots in his favor, had envisioned. Yes, many members of the College of Cardinals wanted a reformer, but the widespread consensus was that the focus

would be internal, as in restructuring the Vatican so that it operates more efficiently, balancing the budgets, and ensuring that the culture of corruption would come to an end. Francis, although he initiated reforms in these regards, had a much broader vision. When he told his brother cardinals in the 2013 pre-conclave meetings that he thought Jesus was knocking at the door of the Church from the inside and wanted to be let out, he was determined that these doors would be unlocked. On becoming pope and being invested with the keys of the kingdom, he would lead by example.

The Shoes of a Fisherman

Easter Sunday 2025 was tense at the Vatican. Less than a month earlier, Pope Francis had been discharged from Rome’s Gemelli Hospital following five-weeks of treatment for double pneumonia and a respiratory infection. Twice, he nearly lost his life. When the eighty-eight year old was released, his doctors said he would return to the Vatican to continue his recovery, but that it would require a strict two-month convalescence period of no interactions with children, no large crowds, and a limited number of visitors.

Francis, ever the maverick and always keen to be around people, bucked those doctor’s orders. There was a surprise visit with Great Britain’s King Charles III and Queen Camilla; there were unannounced trips to pray in St. Peter’s Basilica, where the pope stopped to greet children and hand out candy; and other flurries of activity that left Vatican officials unsure of what to expect as the Church headed into Holy Week, the most sacred period of the year for Christians.

The Vatican, for its part, would not comment on the pope’s plans and whether he would participate in the many liturgies during the week. But when Holy Thursday arrived, Francis left the Vatican and headed to Rome’s Regina Coeli Prison to continue his custom

of visiting with prisoners on that day. He was not able to celebrate the Mass of the Lord’s Supper and wash their feet, a tradition he began just weeks after his election, when he scandalized some Catholics for including women and Muslims in the service. “This year I cannot do it,” the frail pope told them, “but I can [be] and I want to be close to you. I pray for you and for your families.”3 In the days that followed, Francis did not participate in the Good Friday Passion liturgy, the Way of the Cross, or the Easter Vigil. What might this mean for Easter Sunday?

While Easter always brings an influx of pilgrims to the Vatican, 2025 is a Holy Year on the Church’s calendar, bringing an even greater surge of Easter Mass worshippers. Thousands of fresh flowers from the Netherlands adorned the outdoor altar in St. Peter’s Square on a picture-perfect day in Rome, but the pontiff was not present for the celebration. At noon, however, when the red velvet curtains on the loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica were opened, the crowd roared as Francis was brought out onto the balcony in his wheelchair.

“Dear brothers and sisters,” he said in a gravelly voice, “Happy Easter!”

While a priest read the rest of the pope’s annual Urbi et Orbi (“To the City and the World”) Easter blessing, the crowd couldn’t contain their enthusiasm, erupting constantly with cheers, applause, and shouts of Viva il Papa! (“Long live the Pope!”). It built to a crescendo when Francis boarded the popemobile for his first tour around St. Peter’s Square since his hospitalization. It was an extraordinary moment to absorb. As I stood with my colleagues on Bernini’s Colonnade overlooking the piazza, I was in awe of this octogenarian defying all odds to be close to his people.

3. Christopher White, “Pope Francis Visits Roman Prison on Holy Thursday,” National Catholic Reporter, April 17, 2025, https://www.ncronline.org/vatican/vatican-news/ pope-francis-visits-roman-prison-holy-thursday.

But another reality was also settling in: This was a very sick man, and he was giving it all he had. On the night of Easter, I asked a senior ranking Vatican official how they assessed the pope’s condition. “The pope is having good days and bad days as he recovers. Today was just a bad day,” adding that plans were still underway for Francis to travel to Turkey at some point in the coming months to take part in a major ecumenical celebration with other Christian churches.

The next day, my phone buzzed at 9:45 in the morning with a message from the Vatican’s press office saying that there would soon be a brief transmission from the chapel of the Casa Santa Marta, the Vatican guesthouse where Francis resided. Could this be a long-rumored resignation that had been discussed while the pope was in the hospital? It seemed unlikely, given that the timing—Easter Monday—is an Italian national holiday. Known as Pasquetta, this is a sacred day spent picnicking with friends and family.

The worst fears of many became clear when the brief streaming video began. The grim expressions on the faces of the four prelates tasked with sharing the news of the pope’s death told the story before I could even turn up the volume on my computer. Cardinal Kevin Farrell began the announcement of the pope’s death by telling the world that Francis had “returned to the house of the Father.” The news came as a shock but not necessarily as a complete surprise.

“His entire life was dedicated to the service of the Lord and of his Church,” Farrell continued. “He taught us to live the values of the Gospel with fidelity, courage, and universal love, especially in favor of the poorest and most marginalized.”4

4. Devin Watkins, “Pope Francis Has Died on Easter Monday Aged 88,” Vatican News, April 21, 2025, https://www.vaticannews.va/en/pope/news/2025-04/pope-francis-dieson-easter-monday-aged-88.html.