Volume 9.8 July2025

Volume 9.8 July2025

Editor’s Note

Featured Column: Culture in Flux

Spot of the Month: Nómaada

Interview Oshobor Odion Peter

Interview Uyi Raphael Aisien

TOP 10 RESTAURANTS OWNED BY NIGERIAN CHEFS GLOBALLY

Interview Wunika Mukan 49

FAST FOOD: THE WAY FORWARD FOR THE NIGERIAN FOOD INDUSTRY

Elvis Osifo Editor-in-Chief, Lost in Lagos Plus Magazine IG: @edo.wtf

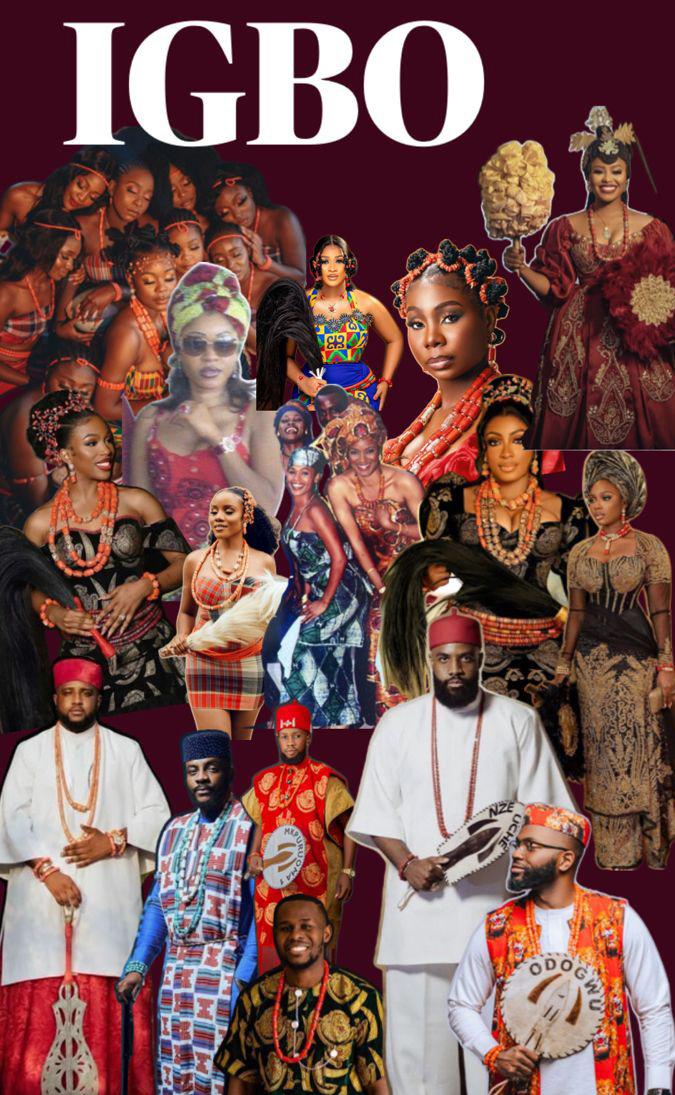

Yup! This is where we’re dropping now. It’s strange, isn’t it? That we live in one of the most culturally rich nations on Earth, yet feel so far apart. With over 250 ethnic groups in Nigeria, it’s almost understandable that we don’t fully grasp the nuance of one another’s lived realities. But it’s also no excuse.

How far na? Why have we become a people of parallel stories, brushing shoulders but rarely embracing, seeing each other’s colours but seldom feeling their weight. We know what NTA tells us, what Oshodi says in whispers, and what @Theasovilla curates. But do we really know each other? Do we know how a Kanuri family in Borno celebrates childbirth? How an Urhobo community mourns. What a Nupe love song sounds like. Why an Edo man must break the Kolanut in any gathering he’s in. Or why a Tiv stitch holds ancestral memory? And still, our culture is powerful. It is more than exportable. It is currency; hard, sexy, “to-die-for” currency. But before we package and ship it off to those willing to exploit everything “Afro,” we must first ask ourselves: do we know the weight of what we carry?

This landmark Culture Issue is our attempt to begin a necessary conversation. Through the lenses of fashion, music, food, and art, we tried to document our roots, our rhythm, our rituals, and our revelations. Culture in Nigeria. It’s a lot to talk about, so we will not rush, but take it slowly. Really thankful for this new theme.

LOST IN LAGOS 9.8 July2025

In this issue, we call on each Nigerian to feel one another again, deeply, truly, as Nigerians. As kin. Chef Fatmata Binta’s Fulani culinary traditions flows to preserve and promote the nomadic culinary traditions of the Fulani people, where Steven Tones’ traditional roots influence his sound. Gain an insider’s perspective on the business of Afrobeats with Toyin Ajewole, or experience profound cultural insights from music legends like Dantala Jatu Dewan. Oshobo Peter is weaving Edo heritage into every stitch, and Charles Oronsaye’s theatrical world of Nigerian couture is becoming a profound visual experience. Uyi Raphael Aisien will seduce you with Nigerian-flavored cocktails, and Sally Wazhi will immerse you in comfort-first designs that preserve Northern identity. Teejay Ameen is tracing Afrobeats’ roots and Ozoz Sokoh is tracing the diversity and history of Nigerian cuisine. Chiamaka Okwara is highlighting beloved Nigerian dishes, and Nentawe Aaron Gokwat is challenging monolithic cultural portrayals. Check out our list of top 10 places that hold Nigeria’s cultural memory and our list of top 5 Musical Influences that have shaped Afrobeats.

There’s no need to wait. E jeka lo!

#DiscoverNigeria

#ExperienceNigeria

#LostinLagosPlus #LostinLagosPlusMagazine

Title: ‘The Culture Issue’ FOUNDER Tannaz Bahnam PUBLISHED BY Knock Knock Lifestyle Solutions Ltd PRINTER Tee Digital Press

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Elvis Osifo EDITOR Pelumi Oyesanya DESIGN Ernest Igbes

CONTRIBUTORS Elvis Osifo, Ernest Igbes, Pelumi Oyesanya, Mona Zutshi Opubor, Joseph Mona, Leon Izegbu, Matildah, Chef Derin, Chef Takus, Fola Stag, Wunika Mukan, Ecstasy Museum, Sally Wazhi, Peter Oshobor, Charles Oghogho, Toyin Ajewoleo Oronsaye, Ozoz Sokoh, Fatmata Binta, Chiamaka Okwara, Steven Tones, Teejay Ameen, Aishat Adedire, Oluwaseun Deborah, Derry Dee Mbata, Timothy Kunat, Enemona Udile, Ajigheye EbruphiOghene (Reggie)

Every month, three products are selected from businesses in Nigeria and shared with you to appeal to your senses. They range from cool, functional items that become indispensable to intimate items that make thoughtful gifts to artefacts you can splurge on and everything in between. This month, I made three picks that will satisfy your tastebuds.

Erupe Armchair by Ile Ila Sunset and sandy beaches: a Nigerian woman.

The Erupe armchair, with its stunning yellow hue and flawless silhouette, is a radiant addition to any home. This statement piece exudes elegance and joy, bringing the warmth of the Nigerian sun into your living space. More than just furniture, the Ile Ila Erupe armchair is an experience, a touch of personal sunshine that whispers beauty and class.

Grey and White Multiprint Strip Culottes by Dye Lab Omoge on the go

This vibrant, smooth, and rich-textured print by Dye Lab Nigeria is surely a must-have in your collection this July. Its easy, breezy feel provides an easy transition from day to night. Made entirely of pure cotton with a touch of Aso-oke, it’s a statement piece that is heavily Nigerian yet heavily modern.

Ivory Butter by Arami Essentials The Achalugo of radiance

This softening whipped shea butter for body and hair targets dry skin, dullness, and scars amongst other benefits. It’s suitable for all skin types except oily skin. This ultimate hydrating body butter is your sure ticket to a lovey-dovey affair with your skin. Summer is approaching and there’s no better time to be wonderful than now.

I’m a 20-something-year-old living in Nigeria, so you know I’m constantly tired. I spend way too much time obsessing over self-care, food, tech, and anything else that makes my life easier, making me your perfect plug for anything! Like most people, I find randomly shopping online at odd hours therapeutic, so much so that if you look into your mirror and say “retail therapy” three times, I will appear.

Featured Columnist

Mona Zutshi Opubor

Ihave been involved with Lost in Lagos Magazine since the inaugural issue in 2017, when I joined as Editor and Featured Columnist. During the pandemic, I began my pivot from publication to education. My children–who were the centre of my world–started to leave home. As each one departed, I grew lonelier. I wanted the kind of structure and social contact that the solitary life of an artist did not provide.

I began working at a school in 2023, and my next chapter bloomed. Once my responsibilities as a teacher grew, I stepped away from editing, intent on saving my keen eyes for my students. I am fortunate

to now teach English literature at an International Baccalaureate program in Lagos, to young adults who are the age of Nigerian university students.

In all the years of writing for this magazine, this is my first column that is explicitly about culture, but culture fascinates me. We talk about it in the course I teach. It is one of the seven key concepts used to analyze and interpret texts. Students deepen their understanding of ideas by looking at the environment in which they arose. For example, you can’t understand how revolutionary Ibsen’s play A Doll’s House was unless you know a bit about gender roles in Norway at the end of the 1800s.

You need to study culture to see literature for what it is because nothing is created in a vacuum. My students love Chimamanda Adichie’s short stories, many of which are set in Lagos. They can relate to the experiences of the characters because no matter their country of origin, all of them have tasted aspects of Nigerian life.

Culture has been a preoccupation of mine since I was small. I grew up in the USA, the only daughter of immigrant parents. We spent our summers visiting relatives in Kashmir, the northernmost state of India. I shifted between cultures, trying to be American in America and Indian in India.

My parents were disappointed with me. They held beliefs rooted in an India that didn’t exist anymore. They wanted me to be an old fashioned, proper girl, yet they preferred to point out my flaws, not teach me about our culture. They had impossible expectations, and they didn’t know how to raise children. I don’t know how I could have been the shy, retiring daughter they dreamed of and also navigated life in America.

What they could not understand is that culture evolves. What worked for them would not work for me. If my existence had revolved around dutiful service to them–as they hoped–where would I be now? They looked back through the generations and saw culture as static, but that is incorrect. If culture was not meant to change, then why weren’t they speaking Sanskrit like our ancestors? Why did they immigrate to the USA? Why did my mom take aerobics classes, while my dad played golf? Their parents never did such things. Why was it okay for them to adapt to a new culture, but they were furious when their children did?

I have had experiences my forebears could never have dreamt of. I am married to a Nigerian man! That fact alone would make my ancestors turn over in their graves–if they weren’t cremated, I mean. But you know what? I don’t care. The imagined perceptions of long dead relatives were used as a cudgel to control me, but I have had enough of that nonsense. Culture should not be a shackle. The poet Walt Whitman wrote, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” I do, too. I can be a writer, an editor and teacher. I can be Indian, American and Nigerian. I am so many other things, and, and I am not done growing.

I am grateful to my parents for giving me life. Like 19th century Norway and Ibsen, I would not be who I am without my mother and father. I need to understand the environment where I was raised in order to understand myself. However, I will never let culture hold me back from evolving. I wish the same for all of you. Live your truth. If your culture stands in your way, plow through it and see what is on the other side. You are large. You contain multitudes.

Mona Zutshi Opubor is an Indian-American and Nigerian writer. She holds an MSt in Literature and Arts from the University of Oxford, an MA in Creative Writing from Boston University and a BA in English Literature from Columbia University.

Read more at www.monazutshiopubor.com

By Tannaz Bahnam & Elvis Osifo

Ever so often, Lagos experiences a new gem pushing the boundaries of flavor and experience. But it is rare that this occurrence includes a marriage between Latin American and Asian cuisines in a fusion like no other. With a focus on Nikkei cuisine, where traditional Japanese techniques beautifully blend with bold Peruvian flavors, and Chifa cuisine, a unique fusion of Peruvian and Chinese influences, Nómaada brings about the union of complex flavors that is truly distinctive. But it doesn’t stop there; it takes this love story even further, incorporating influences from across Latin America and Asia to deliver a culinary journey unlike any other.

Here, dining isn’t just about the food; it’s about the experience. Much like a nomad exploring the corners of the world, stepping into this restaurant is akin to that sense of adventure. Local Nigerian artists and artisans have played a pivotal role in shaping the restaurant’s design, with murals that blend Nigerian and Latin influences, creating a visual feast for the eyes. The name itself invites guests to explore new cultures and flavors, tunneling through a luscious

dining experience that would ordinarily not be pushed.

The menu at Nómaada is a masterful blend of sophistication and creativity. Signature dishes like the Acevichado Maki Roll would tantalize even the most discerning tastebuds. Its layers of tender salmon, creamy avocado, and a tangy ceviche-inspired sauce creates a perfect balance of freshness and zest that transports you from the bustling streets of Peru to the serene sushi bars of Japan. The Truffle Ponzu Salmon Belly Nigiri, with its melt-in-your-mouth salmon belly, earthy flavor of truffle and refreshing ponzu sauce citrus burst is another indulgent bite. For those seeking something with a little more fire, the Ajilo Fire Prawns smothered in a spicy garlic sauce would deliver a fiery, savory richness your palate will forever gossip about. And for something truly special, dishes like the Tunno Nikkei Tiradito with hints of Peruvian aji amarillo speaks to Nómaada’s concept.

The Chef’s Table offers a truly intimate dining experience where guests can enjoy a specially curated menu, with an unforgettable

and transportive culinary voyage. If you seek a more relaxed vibe, the outdoor bar invites you to have a cocktail, enjoying the courtyard and admiring the “Mr. Noma” statue, a nod to the restaurant’s wanderlust-inspired concept.

You could try the Mango Sticky Rice Cocktail, a creative masterpiece that captures the essence of the popular Thai dessert. With creamy coconut, tangy mango, and a small treat of sticky rice on a stick, this cocktail is a flavorful ode to Thailand’s beloved dessert. Feeling a bit more adventurous, The Popcorn Cafe Cocktail would challenge your senses, blurring the line between cocktail and dessert, while the Tatemado Jalapeno sour will make you wonder why anyone should really need dessert at all.

But when dessert calls, you must answer, simply not resisting

Grandma’s Nómaada’s Churros. This generous portion of crispy, sweet fried dough, dusted with cinnamon sprinkles, is the perfect way to end your journey at Nómaada.

With its unique concept and exceptional blend of Latin American and Asian flavors, Nómaada is quickly becoming a must-visit destination in Lagos. Whether you’re an avid food lover or simply looking for a place to enjoy a night out, Nómaada offers an unforgettable journey through both culture and cuisine. So come, embark on your own culinary adventure, and let Nómaada show you the world, one bite at a time.

Nómaada

4B Musa Yar’Adua Street, VI, Lagos IG: @Nomaadalagos

Interview

Moriam Ajaga

Serving as the Special Adviser to the President of Nigeria on Art and Culture, Moriam Ajaga, a cultural powerhouse, works closely with the Honorable Minister of Art, Culture, Tourism and the Creative Economy, Barrister Hannatu Musa Musawa. Over the years, Moriam has worked across public health, sustainable development, creative entrepreneurship, and cultural strategy—always with one purpose: to help build systems that empower people. Whether she’s shaping policy, supporting young creatives, or busy championing African design and global exchange through her role as a founding board member of Design Week Lagos, Moriam remains committed to the belief that culture is one of our greatest tools for connection and transformation.

How would you describe culture in Nigeria, and what aspects are your personal favourites?

Nigeria’s culture is everywhere. It lives in everything we do. It’s in how we cook, speak, gather, dress, and celebrate. It’s our music and movies. It’s fluid, resilient, and deeply expressive. Personally, I’m drawn to textiles and material culture. I have a deep love for Aso Oke, Adire, Akwete, Saki. I love how our textiles are living documents, each thread telling a story of people, place, and purpose. These aren’t just fabrics. They’re records of where we come from and who we are. I also find great joy in seeing how contemporary artists are using tradition as a launchpad for bold, new expressions of Nigerian identity.

In your role, what does cultural preservation and promotion look like at a federal level today?

Cultural preservation today is about more than protecting the past, it’s about safeguarding our identity for future generations. We are embedding culture into policy, infrastructure, education, and diplomacy. At the federal level under the leadership of the Honorable Minister Barrister Hannatu Musa Musawa, and in alignment with His Excellency President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, GCFR’s Renewed Hope Agenda, we are embedding culture into our national priorities. This means investing in the repatriation of stolen artifacts, capacity development, job creation, infrastructure, reviving the National Troupe, digitising the national collection, supporting craft hubs, and in spaces that celebrate our creativity. These efforts ensure that our past is preserved, our present is documented, and our future is secured.

With over 250 ethnic groups, how are you ensuring inclusive representation across Nigeria’s diverse cultural identities?

Inclusion is not a principle, it’s a practice. Through initiatives like the Renewed Hope Cultural Project, and the Reimagining Hope Residency, we are working across all six geopolitical zones to ensure that every Nigerian sees themselves in our cultural narrative. We prioritise underrepresented traditions, local languages, and grassroots-led initiatives. We’re not just amplifying diverse voices, we’re co-creating with them. We work closely with state actors, grassroots organizations, and independent creatives to ensure every community sees itself reflected in our cultural narrative.

What systems are being built for long-term cultural sustainability, especially around funding, archiving, and training?

We’re building systems that make creativity sustainable. The Honorable Minister’s 8-Point Agenda is focused on institutionbuilding. Key interventions include; the Creative Economy Development Fund (CEDF), with which we are unlocking funding for cultural entrepreneurs. The Creative Leap Accelerator Program (CLAP) provides mentorship and capacity-building for early-stage talent. And through the Creative and Tourism Infrastructure Corporation (CTIco), we are building world class museums, galleries, arenas and nationwide hubs for archiving, training, performances and exhibitions. Alongside this, we are developing a national Intellectual Property (IP) policy in collaboration with the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment, and Justice, along with other relevant MDAs, to protect the rights of creators and traditional knowledge holders. Each of these systems is designed to ensure that Nigeria’s creative sector is treated not just as a cultural asset, but as an economic engine to drive GDP growth.

From a policy lens, what is the vision for harnessing Nigeria’s cultural capital for national development?

The vision is clear: to make Nigeria the creative capital of Africa. This

means building the infrastructure, talent, and strategic partnerships that turn our cultural wealth into economic power. Under the Renewed Hope Agenda and the Honorable Minister’s leadership, we are investing in arenas, festivals, exhibitions, and global showcases. We are promoting creative exports, embedding culture into tourism and trade, and using cultural diplomacy to shift how Nigeria is seen in the world, via our soft power vehicle Destination 2030; Nigeria Everywhere. Culture, for us, is not just pride, it’s policy. It fosters unity, inspires innovation, attracts investment, and tells the world who we are.

What would you say to Nigerian artists, curators, and creative communities about their role today?

You are center stage. You are the custodians of our memory and the architects of our future. Whether painting murals in Mushin or curating exhibitions in Milan, you are shaping how Nigeria sees itself and how the world sees us. To every creative out there: be proud, be intentional, and be generous with your talent. Share your stories. Collaborate across borders. And know that we are working to build systems that not only celebrate you but sustain you and support your

‘‘

brilliance.

What legacy do you hope to leave? And what would success look like 10 years from now?

My legacy is to help deliver on the cultural vision of Mr. President. I do not see this work as mine alone, but as a contribution to a greater national mission, one in which culture is not decorative, but developmental. I want to help build systems that outlast individuals; systems that protect heritage, create jobs, support artists, and strengthen identity. If in 10 years we have a thriving creative economy, world-class cultural spaces, and artists who are recognised and rewarded at home and abroad, I’ll know we’ve succeeded. That is the legacy the Honorable Minister Barrister Hannatu Musa Musawa is building with clarity and courage. I’m honoured to contribute to that vision in service of His Excellency President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, GCFR, and his Renewed Hope Agenda for a united, creative, and culturally confident Nigeria. Then I will be proud to have played a small part in helping bring Mr. President’s cultural legacy to life. This work is about building the future Nigeria deserves, through culture— vibrant, united, globally respected.

I’m honored to support a Minister whose passion for Culture is matched only by her bold vision and to serve His Excellency, Mr. President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, GCFR, whose Renewed Hope Agenda places culture at the heart of national development.

Interview

Wunika Mukan

Director, Wunika Munika Gallery

IG: @wunikamukangallery

Meet Wunika Mukan, the director of Wunika Mukan Gallery. She has a significant background in the arts, and has been involved with various cultural and artistic projects. She has served as the Brand Director for the African Artists’ Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to the promotion of contemporary African art. Her work extends to major events in the art world, including her involvement with the Nigerian Pavilion at the 57th Venice Biennale, the Lagos Photo Festival, Art Summit Nigeria, and the Kadara Yoruba Heritage Festival.

Before the gallery, before the exhibitions, who were you? What parts of your personal journey shaped the vision behind the Wunika Mukan Gallery?

Before the gallery, I spent some transformative years at the African Artists’ Foundation, a non profit art organization that truly shaped my perspective on the art world through projects like LagosPhoto, The National Art Competition, Artbase Africa. My role there was about connection whether it was coaxing corporations to step up and support the arts during a time when it was far from trendy, or bringing together a diverse array of art organizations to collaborate on projects. There was also the dance of navigating government relations and the general public, trying to get them to understand what we were doing and why it was important.

After my time at the foundation, I took on larger projects like Recyclart with Sterling Bank, Art Summit Nigeria, and

It’s in the strange, out-of-the-box way of thinking, that I find true magic. ‘‘

the Nigeria Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2017. These experiences opened my eyes to the complex hurdles that artists face. It sparked a fire in me to create a gallery that goes beyond just showcasing art. I envisioned a community hub where artists can thrive, share their stories, and connect with one another. It’s about amplifying voices and providing a platform for innovative expressions.

Curating in Lagos requires both sensitivity and boldness. What drives your curatorial choices? Are there recurring themes or emotional undercurrents you find yourself drawn to?

Curating is a delicate dance of sensitivity and boldness, and honestly, it can be an emotional rollercoaster. I thrive on the honest stories that pulse with life and a quirky twist. There’s something irresistibly captivating about the peculiarities of African experiences, especially when those narratives march

to the beat of individual expression complete with chaos and charm.

I’m drawn to the unconventional. It’s in the strange, out-ofthe-box way of thinking, that I find true magic. I see beauty in the boldness of individualism, especially when it challenges norms or dances along the edges of societal expectations.

Recurring themes, for me, revolve around resilience, and unapologetic individuality fueled by a narrative style that embraces the quirks of life . After all, art isn’t just to be seen; it’s a visceral experience, something that resonates deeply and passionately.

What does a “Nigerian story” mean to you and how do you translate that into visual language through the artists you choose to work with?

A Nigerian story is that of the unbreakable Nigerian spirit. If you’ve lived it you recognize it. I love to share work by artists who continue to challenge themselves through their work using their own lived experiences. Drawing on their experiences with honesty and their own unique voice and flair, making us intern recognize parts of ourselves in the past or yet to come.

Your current show features muralist Ojooluwatide Ojo, exhibiting until June 30th 2025. How did you discover Ojooluwatide’s work, and what about it resonated with you as a curator?

I’d been fortunate enough to run into Tide’s work in Lagos. Her murals and previous exhibitions at Miliki particularly grabbed my attention. I love her textured works but beyond the initial beauty of her palette and the wool she uses to embroider

over parts of her works on canvas the subject matter she covers is always so tender, thoughtful and relatable. Because her work is so relatable the ideas seem easy to convey but it’s actually quite complex to convert such personal stories into artwork that the viewer can completely lose themselves in and also project themselves into.

There’s often a tension between preservation and experimentation. How do you balance showcasing traditional expressions of Nigerian culture with more radical or abstract contemporary forms?

In navigating the tension between preservation and experimentation within Nigerian culture, it becomes crucial to embrace authenticity. Our traditions are not static relics but dynamic expressions that can coexist with radical contemporary forms. To find equilibrium, we must honor what resonates with our identities, merging the old with the new in a way that feels genuinely representative.

The individuals I admire those quirky Africans embody this beautiful blend of tradition and innovation. They navigate life with an honesty that challenges societal norms, often creating art that is both reflective and avant-garde. By showcasing such expressions, we invite audiences to rethink their perception of beauty and identity.

In our gallery, we embrace this quirkiness, encouraging collectors to step outside conventional boundaries. Art should provoke, challenge, and inspire introspection. We aim to create a space where stories, both traditional and experimental intertwine, and reveal new worlds that resonate deeply with individuals. In doing so, we cultivate a richer understanding of ourselves and each other.

Interview Nentawe Aaron Gokwat

Art Curator and Founder, Ecstasy Arts Gallery Jos IG: @ecstasyartsgalleryjos

Nentawe Aaron Gokwat is a visionary visual artist and the driving force behind Ecstasy Arts Gallery, a beacon of modern visual arts in Jos, Plateau State. With a profound dedication to exposing the authentic spirit of Africa, his work is deeply influenced by the ancient Nok culture, and he champions inclusive art engagement through initiatives like “Sip and Paint.” A decorated artist and the esteemed Secretary of the Society of Nigerian Artists, Plateau State chapter, Nentawe’s gallery has become his most expansive and vibrant canvas.

Northern culture is often portrayed as monolithic, yet it’s incredibly diverse. In your experience, how has Northern cultural identity evolved especially among younger artists and creators? What are they reclaiming, reshaping, or releasing?

The unknown often attracts negative reactions or rejection mostly because people simply don’t know enough about it. For far too long, the North has been perceived as monolithic, especially by those who haven’t taken the time to experience it firsthand. As someone born in Zaria and currently based in Jos with the privilege of traveling across various northern states I can confidently say that Northern Nigeria is incredibly diverse. This diversity is reflected

in our festivals, celebrations, languages, and traditions. Events like the Durbar Festival, Argungu Fishing Festival, Nzem Berom, Pusdung, and many others showcase the vibrant cultural expressions of different ethnic groups. The discovery of Nok artifacts, the strong portrayal of royalty, and ancient architectural sites further emphasize the region’s rich heritage. Even the natural landscapes speak volumes, supporting the narrative of deep cultural exchange and long-standing values.

Recently, there has been a noticeable shift especially among younger artists and creators. They are more open, more intentional about telling original stories and presenting accurate perspectives of their people. They are reclaiming the role of storyteller, no longer outsourcing it to outsiders or foreign narratives. This generation has awakened. We are now able to speak more freely about parts of our identity that were once suppressed, misunderstood, or simply overlooked.

The philosophies behind art from this region have long been unexplored but that’s changing. There’s a quiet revolution happening, and I’m proud to be part of it.

What specific forms, symbols, or materials do you consider treasures of Plateau’s cultural identity? Are there practices you’re actively trying to preserve through exhibitions or education whether it’s dyeing, weaving, carving, or ceremonial performance?

Plateau State is a cultural goldmine. It holds a rich tapestry of ethnic groups, each with distinct traditions, symbols, and art forms.

Among the treasures I hold close are Pottery, Iron smelting, terracotta sculpting, and weaving practices that date back to the Nok civilization, which had one of the most advanced early artistic traditions in Africa. The Berom, Afizere, Anaguta, Mwaghavul, and Tarok peoples, among others, also carry strong cultural identities reflected in their architectural patterns, ceremonial performances, textile traditions, and body adornment practices. The symbolism in their beadwork, the addresses, musical instruments, and even in the use of earth pigments in wall painting, tells stories that go beyond words.

At Ecstasy Arts Gallery, we are intentionally working to preserve and reintroduce these traditional art forms in a way that speaks to a new generation. We host exhibitions that center indigenous techniques, and we offer community art sessions and Sip and Paint experiences that encourage younger and older audiences alike to reconnect with their roots. These are more than just creative exercises. They’re acts of cultural memory and resistance.

Across the North and Middle Belt, garments aren’t just decorative, they speak. How do you approach fashion and wearable art as a curatorial focus? And what traditional fashion elements from Plateau are most precious to you?

Absolutely fashion in this part of the world is deeply symbolic. In the North and Middle Belt, what we wear isn’t just about appearance; it’s a visual language. From bead arrangements that signify age and

‘‘

Our stories were never confined to paper. They lived in the architecture of shrines, in the carved figures, in ceremonial dances, in lullabies, and in the marks we wear on our skin.

marital status, to wrappers that speak of clan ties, to turbans and headpieces that carry spiritual or social significance every garment is a story. As a curator and visual artist, I see wearable art as a living archive. It carries memory, meaning, and movement. At Ecstasy Arts Gallery, we’ve begun to explore fashion not just as style but as cultural sculpture, something worn on the body but rooted in ritual, history, and geography. We’re interested in how traditional fashion can merge with contemporary design without losing its soul.

From Plateau specifically, I hold a deep reverence for the Berom and Afizere beadwork, the richly layered iron shells used in Ngas ceremonial dances, and the handwoven fabrics and body adornments found in communities like the Mwaghavul and Ngas. Each piece speaks of belonging, lineage, or purpose often made with materials that are sourced directly from the land. We’re currently exploring projects that showcase these elements through photographic storytelling, mixed media, and live exhibitions, where wearable pieces are displayed alongside the stories and practices they represent. It’s about preserving the message, not just the material. In a time when globalization threatens to erase cultural specifics, treating fashion as art and as heritage is one way we can protect and evolve these expressions.

Much of Nigeria’s ancient history isn’t written, it’s sculpted, sung, painted, or told. How does the gallery approach the idea of art as oral tradition in visual form? Are you curating works that document fading rituals or reinterpret ancestral

That’s the truth Nigeria’s ancient history lives in the body, in sound, in rhythm, in form. It has always been oral, performative, and visual. Our stories were never confined to paper. They lived in the architecture of shrines, in the carved figures, in ceremonial dances, in lullabies, and in the marks we wear on our skin.

At Ecstasy Arts Gallery, we approach art as a continuation of that oral tradition, a language that speaks even when words are absent. Many of the works we curate, whether paintings or sculptures are rooted in cultural memory. They reinterpret rituals, ancestral symbols, and native philosophies in a way that brings the past into conversation with the present.

We are especially interested in works that revive fading rituals or reinterpret myths and beliefs that younger generations may no longer know. Some of our artists explore themes like fertility rites, initiation ceremonies, ancestral worship, and seasonal festivals translating them into contemporary visual narratives. This kind of work doesn’t just preserve memory; it invites reflection and participation, especially for people disconnected from those roots. We also see the gallery as a space of cultural education. Through exhibitions, talks, and community events, we encourage dialogue around the meanings behind these visual traditions.

Every gallery has a quiet belief system. What philosophy drives your curation? Are you more drawn to bold provocation, quiet reflection, or cultural fidelity?

And how do you decide which artists or stories deserve space at this moment in Nigerian history?

At Ecstasy Arts Gallery, our guiding philosophy is rooted in truth, cultural relevance, and intention. We are driven by the belief that art should not only be beautiful, it should be meaningful. Our curation leans into cultural fidelity, but also creates space for bold provocation and quiet reflection, depending on what a piece is saying and how it engages with the present moment. We’re particularly drawn to work that feels necessary, not just trendy. That could be a sculpture echoing ancestral memory, a painting confronting political silence, or a visual expression of personal healing. What matters most is authenticity. We ask: Is the work saying something real? Is it contributing to the cultural archive of our time? Is it making someone think, remember, or question?

Curation for us is also an act of advocacy. In a country like Nigeria, where so many voices are unheard or erased, we intentionally give space to artists who are preserving endangered heritage, challenging norms, or redefining what it means to be Nigerian today especially from perspectives that are often overlooked, such as Northern, Middle Belt, or rural voices.

At this moment in history, when identity, memory, and meaning are being renegotiated across Africa, we feel a deep responsibility to hold space for stories that matter, and to do so with care, conviction, and cultural integrity.

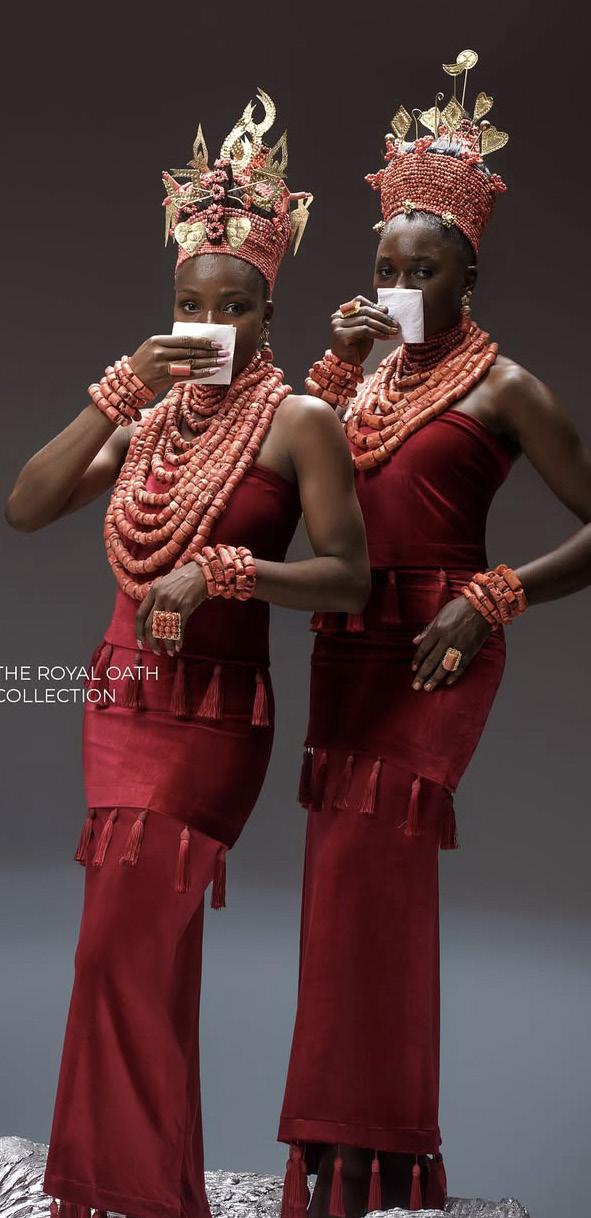

Interview Oshobo Odion Peter Founder & Creative Director, OSHOBOR

Your brand OSHOBOR is rooted in Edo heritage and inspired by the love between fathers and sons. Can you take us back to the very moment the idea of this brand was born?

It is inspired by love, yes, between fathers and sons, very true. So I had started the brand in 2020 and for what it was, I wanted to be a fashion designer and show people what I was capable of doing. But I knew that I wasn’t hitting the right spot when I initially started because I was trying to find my identity, find myself, a brand voice. Then it became a reality when, in 2021, I got on a platform called Design Fashion Africa, where, with nine other designers we were mentored by Adebayo Oke Lawal, the Style Infidel, Akin Faminu, Ituen Bassey and Godson Ukaegbu, amongst many others. We had the opportunity to speak with these people, get advice from them, and learn from them. We had them examine our brands and tell us what we’re getting wrong.

Godson Ukaegbu, though he didn’t want to talk to me at first, told me “you’re trying so hard to be international when you can be yourself, you can be indigenous and yet you will be global, they will look for you.” I was like, “I don’t understand.” You realize that the moment you’re African, the international

‘‘ Heritage can serve as both archive and prophecy

So changing the name before releasing the collection was a good thing; so the collection would now promote the new name. And that’s what I did, and it was so good.

Benin City, rich with culture and tradition, is not often at the forefront of Nigeria’s fashion capital narrative. Why did you choose to stay rooted there, and how does that decision influence your creative process and storytelling?

Meet Oshobo Odion

Peter, the Creative Director of the indigenously sustainable luxury fashion brand OSHOBOR. OSHOBOR has carved a niche for itself by creating pieces that are deeply rooted in Nigerian culture and narratives. The brand is known for its eccentric and vibrant designs, which often tell stories and aim to challenge societal norms, such as toxic masculinity. They have released several collections with evocative names like “EDO ODION” a tribute to the Edo people and the Benin Kingdom, and “NA MAN YOU BE” which critiques certain societal expectations of men.

market will look for you because you are what they do not have. When you’re trying so hard to be like them, you are trying to be what they already have, so they wouldn’t pay attention to you. It made sense. I wanted something so big for myself and for the brand, and I was going to put a name that had so much weight, power, legacy, influence, and history. And I settled with my surname. It didn’t take me up to two days, I got a logo. I set things rolling. Why? Because a month after I was to leave the Design Fashion Africa contest, I was supposed to launch a new collection.

I was in Lagos at the time when I started my brand. Two years later, I decided to move out of Lagos. First of all, I believe that you can be anything you want to be from any part of the world. I don’t think that location should be a hindrance to someone achieving greatness. I know the potential I have. I know what I’m made of. I knew that what I was or what I had in me was bigger than wherever I stayed. But then again, I needed to prioritize my mental health, my peace of mind, and I realized that Lagos wasn’t that place for me. So I studied in Benin, and I knew what it felt like to stay in Benin. I was born and brought up in Lagos, went back to Lagos after graduation. I knew what it was like to be in both cities. I thought, “you know what? Benin is peaceful.”

Benin is good for my mental health. I’d rather stay here. There were thoughts and worries and concerns from family and friends. People do things from anywhere in the world. Why should going to Benin change anything? In fact I just got back from a showcase I did in Paris. I just had this belief that I could move mountains all the way from Benin. Owing to the fact that I had the Edo collection in view right from the inception of the brand, I understood that being in a place that inspires the collection would make it more interesting. Plus, unlike Lagos, Benin market is untapped in so many areas. I knew I could get labor in Benin. I knew I could get a lot of things. I could expand my business better in Benin than in Lagos. Not because I have clients in Benin. I don’t. Neither did I have that many clients in Lagos. So there was really nothing keeping me there. Moving to Benin was the best option.

As we explore Nigerian culture through the lens of fashion in this issue, we’re interested in how heritage can serve as both archive and prophecy. What elements of your Edo culture do you

preserve intentionally in your work, and what do you hope OSHOBOR will say about Nigerian fashion 50 years from now?

Of course, heritage can serve as both archive and prophecy. In some of the pieces from this Edo collection, you see that I didn’t even shoot a look book for the entire collection. I only shot editorials in a very Edo-like setting. The reason is because I wanted to preserve these pieces, the culture, the tradition, the collection. And I’ve been able to do that successfully. Upon releasing this collection, I had two different people reach out to me to make an ‘Edo collection’ that can be displayed in an art gallery or a museum. These are good ways that we can promote our heritage in archives.

When it comes to prophecy, it means we are telling what the future holds. And with what we are doing, pushing the narrative culture through fashion, we know that we are giving people, future designers, a trail to follow. We are letting them know that the future is bright. Everything is going to look better, everything is going to get better. But one thing is certain, the Edo culture remains the same. Queen Idia, Coral beads, the Festac mask, and the Ada and Ebe are not going to change. Neither will the coral beads change. All of these things are permanent. They are archives that have been kept and preserved for years and will remain. But every other thing leading to that and compliments that, like: the fashion, how we are presented, how we are seen, how we are accepted and appreciated for what and who we are, will definitely evolve, change and get better. I think that in the next 50 years, Nigerian fashion will be very indigenous. A

lot of people would wear Nigerian. A lot of people would wear African. ‘Nigerian’ will be at the forefront of fashion in the world.

Sustainability is a huge part of your practice. In a country like Nigeria where access to sustainable materials and practices can be complex, what does sustainable design look like in reality for OSHOBOR?

Sustainable design for OSHOBOR looks like a three-month and five-month’s work on just a dress. Maybe I need to show a video of what it looks like to install wool on damaged fabrics, on lace fabrics, on dead stock fabrics, on every kind of fabric. It’s tedious. It requires patience. It requires time. It requires love. Yes, it requires love, most importantly. Sustainability is not only recycling, it is also upcycle, which we do here. Sustainability is slow fashion. Sustainability is taking your time to make garments that will stand the test of time. Sustainability is making pieces that are worthwhile, that you can keep and you can pass on from generation to generation. Why? Because every process, everything that went into that garment was carefully thought and made.

Who are you designing for? Describe the OSHOBOR wearer, not just how they look, but how they feel, move, and take up space.

We are designing for every man out there who dares to be different, every woman who is in touch with her emotions, for men and women who have roots and ties to their cultural heritage, and those who relate to our story: Love, culture, hurt, heartbreak,

survival. Those are the people we are designing for. People that understand our narrative, people that are ready to literally take up space with OSHOBOR, because OSHOBOR takes up space.

Finally, how would you define Nigerian fashion, not from the eyes of Lagos or global runways, but from the eyes of Benin, from your roots, and from the heart of OSHOBOR?

Nigerian fashion is evolving. Not from the eyes of the global stage, or Lagos, or from the eyes of Peter Odion that is based in Benin. I like to see that there is change, growth, and evidence in all that we do as fashion lovers, because it cuts across designers now.

We go back to our roots, dig up designs and refurbish them. We dig up stories and inspirations and come back to tell the world. It goes to show that we are evolving. And in evolving, we are not leaving our past, our history, our culture. We are carrying it alongside with us. This is something that means a lot to me. I just also like that we are doing it with so much intentionality. It’s almost as though we are not trying to impress anybody, we are doing it because we have to do it. I love that that is happening. People see that Nigerian fashion is evolving, even in Benin, because the things we couldn’t wear years ago, we can wear now in Benin. Places we couldn’t enter looking like fashion people, we can enter there now. People now understand that fashion can take you to places, whether as a wearer, a seller or a buyer. So yes, fashion is evolving, and with OSHOBOR we are taking our roots along with us.

‘‘

garaje ba, shine abin zai yi kyau.

Meet Sally Wazhi, the visionary founder and Creative Director behind the eponymous fashion brand based in Jos, Nigeria. Her brand crafts elegant, comfort-first womenswear, thoughtfully designed for Black women navigating the beautiful changes of motherhood, work, and womanhood. With a focus on modest, structured, and feminine designs inspired by the quiet strength of Northern women, Sally is dedicated to restoring confidence and helping women feel seen and beautiful without compromising on comfort.

Many Northern women learn fabric care, wrapper styling, and modest tailoring from mothers and aunties fashion as an oral tradition. What cultural lessons around fabric and femininity were passed down to you? And how do those teachings shape the soul of GlamGarments?

What made me pay particular attention to fabric was laundry time growing up. My mother treated her wrappers like royalty. She avoided harsh scrubbing, didn’t use strong detergents, and always added a pinch of salt to the water she believed helped preserve the colours and stop them from running. To her, the condition of the fabric determined whether an outfit was still wearable or had already become a rag. I remember her saying in Hausa: “Ba da garaje ba, shine abin zai yi kyau.” (It’s not by the exertion of force that a thing becomes beautiful.)

That simple sentence stayed with me. It taught me the biblical principle of tending and keeping that beauty isn’t forced. It’s preserved through deliberate, gentle care.

That same wisdom influences how I design today. I believe that no matter how much

a woman has laboured in life through childbirth, work, or personal battles her beauty can still be preserved. All it takes is clothing that honours her body with comfort and elegance. No pressure. No harsh standards. Just the kind of care my mother showed her wrappers.

In today’s world where global fast fashion often erases local aesthetics, do you see your work as a form of cultural resistance? How intentional are you about preserving Northern identity through your designs, even as trends evolve?

Trends come and go that’s exactly why I never feel pressured to follow them. Especially now, when revealing elements seem to be the new standard in design, I’ve chosen to walk a different path. In the North and Middle Belt, one thing that stands out culturally is modesty. There’s a quiet belief here that a woman is like a delicate rose, beautiful, soft, and worthy of protection from the harshness of the world if she’s to keep blooming. That belief has shaped my design philosophy. When you think of the SallyWazhi fashion brand, I want you to think: Modesty. Ease. Preserved beauty.

In many cultures, fabric can be a political statement about what you wear, how you wear it, and where it’s sourced from. Are there moments in your design journey where choosing a particular fabric or style felt like reclaiming a story, a people, or a voice?

Absolutely. One clear moment was in my Bouquet 35 collection created to celebrate the African woman’s blooming. Not just her beauty, but her process. Her becoming. I needed a fabric that could speak that language, something textured, rich, alive. But the available 3D options felt limiting. They weren’t telling our story.

So I created my own fabric. Every floral detail was placed by hand, not just for decoration, but to embody the idea that a woman’s bloom is not silent. It can be felt in her movement, in her presence. Just touch her, and you’ll know: She has stories. She has survived. And she’s still blossoming. That collection was a way of reclaiming space for our story.

In the Northern Nigerian context, fabric is never just fabric; it carries weight as

history, status, spirituality, and beauty. From the matte discipline of shadda to the celebratory shimmer of lace, every cloth speaks to something deeper. As a designer, how do you select fabrics that not only suit the silhouette but also preserve cultural meaning?

If given the choice, I’d always pick heritage over just elegance but when a fabric can carry both, I go for it. I believe every fabric is saying something. That’s why it’s easy to tell which ones feel luxurious, which ones carry culture, or which are soft enough to wrap a baby in. They all come with their own kind of message. One fabric I’ve really enjoyed working with is guodo. I call it the Northern Aso-Oke, and it’s been part of my collections for the past three years.

It’s rich, soft, but still holds structure just like the Black woman. It reminds me of the kind of strength that’s not loud but very present. When I choose fabrics, I’m not just looking at the color or shine. I’m asking: “Will this fabric match the kind of woman I’m designing for?” It has to carry her story, not just her shape.

Finally, is there a particular fabric you always return to one that, for you, holds spirit, memory, or grounding? What story does it carry for you as a Northern woman, and what do you hope others feel when they wear it through your designs?

One fabric I keep going back to is guodo, especially the type our mothers and grandmothers used to wear. I remember making a jacket out of my mum’s old Aso Oke/guodo wrapper. Honestly, that piece felt different. It wasn’t just a design, it was like I was carrying her with me. Her story, her strength, everything she had poured into raising us.

I’ve had this dream for a while now to reclaim those old wrappers from our mothers and grandmothers and turn them into modern, stylish outfits. Not just for fashion, but as a way of saying, “This is where I come from and I honour it.”

Guodo just feels like home to me. It’s soft, it’s structured, it’s steady like a woman who’s seen life and is still standing.

Interview

Chef Fatmata Binta Founder,

Dine on a mat & Fulani Kitchen foundation

M

eet Chef Fatmata Binta, a celebrated Fulani chef, storyteller, and the visionary founder of Dine on a Mat and the Fulani Kitchen Foundation. Born in Sierra Leone to a family with Guinean roots, her work passionately preserves and promotes the nomadic culinary traditions of the Fulani people across West Africa, including Nigeria. Through her initiatives, she collaborates with rural communities, particularly women, to document and celebrate these rich, indigenous food systems.

For us Fulani people, food isn’t just about nourishment, it’s a way of life, a reflection of our connection to land, livestock, and movement. ‘‘

As a chef who champions indigenous ingredients, what are some underutilized or lesser-known Nigerian ingredients that you believe have immense potential to be highlighted on a global culinary stage?

When we talk about underutilised ingredients, I’m immediately drawn to the grains, herbs, and wild foods the Fulani people have relied on for generations. Fonio (or Acha, as it’s known in Nigeria) is a perfect example, it’s one of Africa’s oldest cultivated grains, drought-resistant, nutritious, and incredibly adaptable. You’ll also find the Fulani using fermented milk in creative ways, incorporating nono, fura, and even millet to create balanced, energy-rich meals that are both sustainable and flavourful. Spices like sumbala (fermented locust bean) and wild leafy greens also play important roles. These ingredients have enormous potential to shine on the global stage, not just for their health benefits, but for the stories they carry.

Beyond the flavors, how do you see Nigerian traditional

meals contributing to the preservation of cultural heritage and identity in a rapidly globalizing world?

For us Fulani people, food isn’t just about nourishment, it’s a way of life, a reflection of our connection to land, livestock, and movement. Traditional meals like Fura da Nono are more than just refreshing, they carry ancestral knowledge. They teach patience, craftsmanship, and community. In today’s fast-moving world, our nomadic foodways remind us to slow down, to honour what’s local and seasonal, and to appreciate simplicity with depth. These meals hold language, ritual, and values, preserving our identity in the face of change.

Are there specific Nigerian traditional meals that you believe hold significant historical or spiritual importance, and what stories do they tell?

Absolutely. Many Fulani dishes are rooted in deep traditions passed down orally. Take Lakh (a millet porridge served with fermented milk or soured cream) it’s often associated with

hospitality and blessings. Preparing milk-based dishes is almost sacred in Fulani culture, especially among pastoralist families. It speaks to our spiritual connection with cattle, land, and the environment. These dishes are often part of ceremonies, harvest celebrations, or rites of passage, every ingredient chosen with intention.

In your work with the Fulani Kitchen Foundation and empowering women, do you see parallels or opportunities to support Nigerian women in preserving and promoting their traditional culinary knowledge and skills?

Yes, and this is something that sits at the heart of my work. I’ve seen first-hand the brilliance of Fulani women in Nigeria, how they preserve traditional knowledge, prepare foods with care and meaning, and pass down culinary techniques that are centuries old. There’s so much untapped potential. Through the Fulani Kitchen Foundation, I see opportunities to create

learning exchanges, support systems, and business models that centre these women, not just as keepers of tradition but as innovators and leaders in the food space.

If you were to introduce a traditional Nigerian meal to someone unfamiliar with West African cuisine, which dish would you choose and what narrative would you weave around it to convey its cultural significance?

I would like to introduce Fura da Nono. It’s simple yet deeply profound. I’d tell the story of how it’s made, how the millet is soaked, spiced, pounded, and rolled into balls, and how the milk is fermented naturally over time. It’s a dish of patience and pride. Sharing it is an act of generosity. It’s cooling, nourishing, and refreshing, but most of all, it’s a cultural emblem. It tells the story of movement, adaptation, and the Fulani people’s unique bond with the natural world.

Interview

Ozoz Sokoh

Author and Culinary expert

M

eet Ozoz Sokoh, a culinary explorer, educator, and author of the debut cookbook, Chop Chop: Cooking the Food of Nigeria. With a journey from geology to gastronomy, she masterfully documents and reclaims West African foodways, celebrating the joy of eating through her Feast Afrique platform. A professor of Food and Tourism Studies, Ozoz inspires with her passion for food and culture from her home in Mississauga, Canada.

Given your extensive work documenting Nigerian food heritage, what do you think is the most underappreciated or misunderstood aspect of Nigerian cultural meals by those outside of Nigeria?

The diversity, complexity, and strong history is the most underappreciated aspect of Nigerian cuisine. Nigerian cuisine has influenced food cultures across the world from Brazil to the American South. Ingredients, dishes, drinks, techniques and more have taken root outside of Nigerian borders, with a legacy that stretches back 400 years as a result of the transatlantic enslavement of Africans. Enslaved West Africans contributed a lot of intellectual knowledge that created successful crops in many parts of the world like how to grow rice in the American Carolinas.

If you had to introduce Nigerian food to a foreigner, which single dish would you pick to leave a lasting impression on their taste buds, and why?

I’d choose Pepper soup for its conversation starter possibilities, as well as its character, flavor, and possibility. It also showcases the unique way Nigerians name dishes, most cultures have a healing, spiced broth providing another layer of connection, it’s versatile, and it’s easy to give people the

spice blend to explore and make their own.

If you could give a “flavor high-five” to one aspect of Nigerian food culture for its impact on the world, which one would get it?

Yajin kulikuli, also known as Yajin kuli, is an aromatic and delicious nutty spice blend. Think sweet and smoky spice and heat, warm, earthy, with deep savory notes. It is incredibly versatile beyond its use as a dip for grilled pieces of suya (meat) added to sauces and dressings, sprinkle over salads, use with fruit and vegetables, and more. It isn’t only packed with flavor, it has a delightful texture. It speaks to the heritage of ingenuity, first with the pioneering transformation of peanut paste to kulikuli by the Nupe, and the knowledge and mastery of meat by the Hausas in the north of Nigeria.

You’ve often highlighted “Food Is More Than Eating.” Could you elaborate on what that means for us?

Every time we hold a plate of food, a glass filled with a drink, there’s more to it than nourishment. The ingredients tell multiple stories, of trade, agriculture, religion, history, geography, influences, culture, identity and more.

Take Nigerian Jollof Rice with tomatoes and peppers, none of which are native to the West African continent. The name? It links us to other places across West Africa and anchors us in the historic 14th century Jollof Empire, in today’s Senegambian region. The kind of rice we often use today? Parboiled long-grain rice, Oryza sativa. Growing up, my mum sometimes used the red-streaked rice from Ekpoma or Abakaliki, Oryza glaberrima, African rice. How did we go from one to the other?

We can learn so much by figuring out the stories the ingredients are telling us. They are saying much more than “fill your bellies”, they are inviting us to explore, go deeper, learn.

What’s a Nigerian meal that you think young Nigerians should absolutely master, not just for the taste, but because it lets everyone else know that “this is a Nigerian?

Stew.

Everyone should know how to make good Nigerian stew - it is delicious, can be used in so many ways, and is the base of so many dishes. So yes, stew, for sure.

Photograph by Oluwapelumi Bamidele

Interview

Steven Tones

Musician and Songwriter

M

eet Steven Tones, a talented musician and songwriter whose musical journey began in Edo State, Nigeria. Since 2015, the artist, born Omigie Stephen, has been professionally creating music, recently captivating audiences with his latest single, “ONE MORE NIGHT.”

‘‘Traditional Nigerian folklore can inspire the lyrics and narratives in today’s Afrobeats

Growing up in Nigeria, what was your earliest and most impactful exposure to traditional Nigerian music?

Hmmm, Growing up in Nigeria, I was exposed to traditional Nigerian music as a child and this became the foundation of my sound discovery as an artist.

The likes of Late Sir Victor Uwaifo, Bright Chimezie, King Sunny Ade, Young Bolivia, Pasuma wonder and many others were and still are my biggest inspiration. Back then I just wanted to sound like them. For example, I was so into Yoruba (Fuji) music that although I couldn’t speak or even interpret what was being said, I enjoyed the sound I heard and it became one of the blueprints for the creation of my own sound today.

Your single “Iyawo Mi” has a title deeply rooted in Nigerian culture. How do you consciously weave traditional themes and storytelling into your modern songwriting?

It’s natural for me to mix traditional sound and modern melodies together due to my exposure to both worlds from the very beginning. ‘IYAWO MI’ means ‘MY WIFE’ in English and it’s just a reflection of the sound within my soul that seeks expression daily.

If you were to create a “Nigerian Music 101” playlist for the world, which three traditional or foundational artists would be at the very top?

If i was to create a “Nigerian Music 101” playlist for the world, the likes of Late Sir Victor Uwaifo, Young Bolivia and Bright Chimezie would be atop the list.

How do you think the storytelling in traditional Nigerian folklore can inspire the lyrics and narratives in today’s Afrobeats?

Story telling is a major part of any music composition and it’s what truly makes a song meaningful. I believe that Music is not only a tool to entertain but also to inform and eventually transform the human mind for the better. So, in many ways, the storytelling in traditional Nigerian folklore can inspire the lyrics and narratives in today’s afrobeats. Afrobeats artists can leverage the story telling in traditional Nigerian folklore in their songs. For example, we have Shallipopi’s Obapluto, which is about the story of the late Oba of Benin, Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi, who was exiled to Calabar during the great benin massacre. The song turned out to be a monster hit both within and outside

Nigeria. This is a typical example of how storytelling in traditional Nigerian folklore can inspire the lyrics and narratives in today’s afrobeats

Looking ahead, what is your hope for the future of Nigerian music, and what role do you see cultural and traditional sounds playing in its evolution?

I see a complete domination of the global music space by Nigerian Music. In fact, this is already happening. A big shout out to Burna Boy, Davido, Wizkid, Rema and the many other distinguished Artists who have been working tirelessly to make this long dream a reality.

I see cultural and traditional sounds playing a very big role in the evolution of Nigerian music. As a matter of fact, this is happening. We are already seeing the infusion of traditional sounds in our contemporary music through devices such as sampling and interpolation. We saw the infusion of Bright Chimezie’s “Because of English” in Davido and Omah Lay’s “With You.” This is a major example of how our traditional sound is shaping our modern sound, which we are exporting to the world.

Interview

‘‘ We cannot use Western yardsticks to measure

Atowering figure in Nigerian cultural music, Dantala Jatu Dewan is a legendary musician and a revered icon of the Ngas people from Plateau State. For over four decades, he has been the driving force behind the preservation and popularization of Ngas traditions through his captivating performances. As the founder of the acclaimed Ndengdeng Cultural Music group since 1984, Dewan has masterfully used indigenous instruments like the Ndengdeng and Kulit to create a unique sound that is both a celebration of heritage and a powerful medium for storytelling. His enduring influence extends beyond the stage, making him a respected voice and a proud custodian of his community’s rich cultural identity.

When Dantala performs, it often feels more like a ritual than a show. There’s fabric, light, movement, sometimes even food or scent. How intentional are these elements in your performances, and what role do you believe they play in cultural storytelling?

Our Music or our Performance is always so because it is Indigenous, it has an origin, unique, spectacular and captivating. Above all, it is historic, informative, educative and entertaining worthy of presentation, preservation and promotion of our culture.

Northern Nigeria is rich with traditions of oral storytelling, call and response chants, and ceremonial rhythms. How does Dantala use music as a vessel for cultural memory and ancestral knowledge?

Most of our songs are Historical, while some are created by us. We get most of our songs from oral tradition and we preserve them to be bequeathed to the generations now and the generations yet unborn.

From turbans to kaftans, your visual presentation feels deliberate and culturally steeped. How intentional is your fashion as part of your musical identity, and how do you see traditional attire as a form of resistance or storytelling?

Most of our Songs are from the celebration of Heroes past, victories, some are for common people from moonlight games, folk tales/songs while others are for all purposes e.g. marriage,

hunting, circumcision, harvest, farming, festivals, etc, etc. While the selection of the Costumes is purposely to reflect the occasion eg from that of the Kings to that of the Common people.

You often sing or chant in Hausa and other indigenous dialects, resisting the pull toward global ‘mainstream’ sounds. What guides your decision to stay rooted in local language and sonic tradition even when that may limit mainstream appeal?

The issue of the “mainstream” is debatable. The Western mainstream is not the same as the African Mainstream. We cannot use Western yardsticks to measure African Music/Dance. Therefore, the issue of global mainstream does not necessarily apply in this case.

When people hear your music for the first time, what do you hope they feel not just emotionally, but culturally? Is it nostalgia, recognition, discomfort, awakening?

When anybody is hearing my music for the first time, I want him/her to be carried along with the rhythm from the fusion of the ensembled Musical Instruments, both traditional and modern, bringing back to memory our original and indigenous tradition. In addition, our songs are not typically in the native languages only. We have a few in English and Pidgin English.

Interview

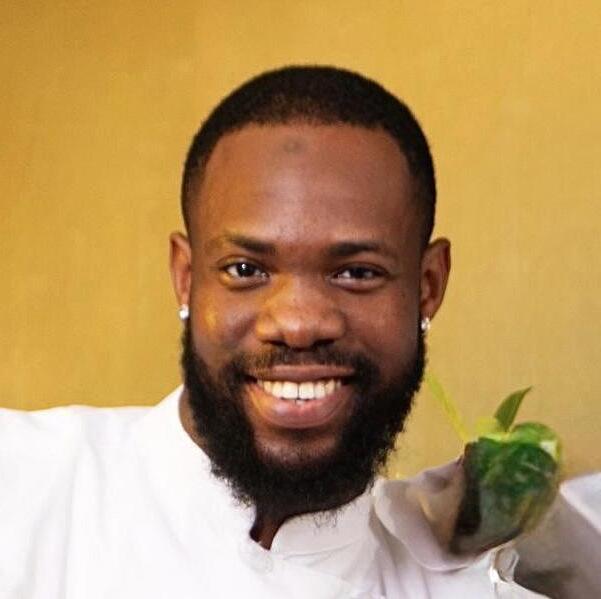

Meet Uyi Raphael Aisien

Founder, Ralph’s Cocktails and Mixologist

IG:ralphs_cocktails

Meet Uyi Raphael Aisien (“Mr. Ralph”) the founder of Ralph’s Cocktails, a leading cocktail catering brand based in Benin City, Edo State. A graduate of the European Bartender School, his expertise is backed by prestigious wins, including the Diageo Cocktail Challenge at Lagos Cocktail Week 2022 and the Angostura Cocktail Challenge. His brand has catered over 325 events across Nigeria. Beyond the bar, he is a dedicated content creator and mentor, training aspiring mixologists and collaborating with global brands to craft unique African cocktail recipes and engaging content.

Each local ingredient is a chance to put Nigeria on the map in a fresh, creative way.

What inspired all of these? Ralph’s Cocktails? Nice! What’s the story?

Ralph’s Cocktails started out as a simple hobby. I’ve always enjoyed mixing drinks and experimenting with flavours, so I often invited friends over to try out my creations, and they genuinely loved them. The turning point came when my wife’s sister was planning her birthday party. She casually asked if I could handle the cocktails for the event. At first, I was hesitant because I had never made cocktails on a large scale before, but with a bit of encouragement, I decided to give it a shot.

I got a few basic tools, sourced the ingredients, and prepared cocktails for the party. To my surprise, the guests were blown away. Their reactions made me realise that this wasn’t just a fun pastime, it had real potential. That’s when the idea of turning my passion into a full-fledged business was born.

You’re known for fusing local ingredients with classic cocktail techniques. What Nigerian flavours or spices do you feel are still underexplored in the global bar scene, and how are you showcasing them?

One of my biggest passions as a mixologist is celebrating Nigerian ingredients. On my page, @ralphs_cocktails, I’ve worked with flavours like tigernuts, zobo, pepper fruit, velvet tamarind, and even palm wineingredients that are deeply rooted in our food culture but rarely explored in cocktails.

I believe these flavours offer richness, depth, and a true taste of home, and they deserve a seat at the global bar table. In many of my recipes, I use these ingredients not just for flavour, but to tell stories, like combining palm wine with Hennessy VS to bridge local tradition and global taste, or infusing syrups with hibiscus and alligator pepper to create something truly bold and unforgettable. My goal is to shift the mindset from seeing cocktails as just a mere indulgence to viewing them as a cultural expression. Each

local ingredient is a chance to put Nigeria on the map in a fresh, creative way.

In a culinary world increasingly focused on storytelling, how do you craft a cocktail menu that not only tastes good but tells a story about where you’re from?

For me, cocktails are more than just drinks, they’re stories in a glass. Cocktails can be built to reflect where you are from, using local ingredients like tigernuts, scent leaf, pepper fruit and palm wine to craft flavours that feel both nostalgic and new. I usually love naming such cocktails after funny slangs, or shared memories that Nigerians instantly connect with. It’s my way of celebrating our culture and showing that cocktails can be a powerful form of storytelling and reliving memories. Through @ralphs_cocktails, I’ve seen how people light up when a drink reminds them of home or a childhood memory and that’s the experience I aim to create.

For example, I once created a cocktail using pepper fruit (a beloved local fruit in Benin) and named it “Pepper Dem.” The drink sparked nostalgia, reminding people of how their parents introduced them to the fruit growing up. The name itself, a playful Nigerian slang, tied it all together while capturing the spicy kick of the fruit and connecting with people’s own memories and stories. It’s more than a

drink, it’s a taste of home.

Your brand operates from Benin, not Lagos or Abuja. What has it meant to champion bar culture outside the usual hotspots? Have you faced unique challenges or found unexpected advantages?

Operating from Benin, instead of Lagos or Abuja, has been both intentional and rewarding. It’s proof that creativity and excellence aren’t limited to Nigeria’s biggest cities. At first, it was a challenge because cocktail culture wasn’t as mainstream here, and resources were harder to access. But over time, I saw that as an opportunity to build something unique. Through Ralph’s Cocktails, I’ve helped introduce and grow appreciation for crafted drinks in this space. It’s fulfilling to know we’re raising the bar and proving that great things can start from anywhere, including Benin.

Cocktails are often seen as indulgent or reserved for nightlife, but they’re also a medium for cultural expression. What role do you think bartenders like you play in shaping Nigeria’s modern food and drinks narrative?

As a bartender and storyteller, I see cocktails as a powerful medium for cultural expression - not just a nightlife indulgence. Through @ralphs_cocktails,

I’ve learned that every ingredient, from zobo to palm wine, carries a piece of our identity. Bartenders like me have the unique role of blending creativity with culture, showing that drinks can tell stories, spark memories, and even preserve tradition. We’re helping reshape how people see Nigerian flavours, not just as ingredients, but as experiences that belong on the global stage.

Lastly, what does “homegrown” mean to you in your craft? And how do you see Ralph’s Cocktails evolving to leave a legacy in the Nigerian (and African) beverage industry?

For me, “homegrown” means staying true to my roots, using what’s around me, drawing inspiration from where I come from, and proudly showcasing Nigerian flavours in my creations. It’s about proving that we don’t need to look outside to create world-class experiences.

With Ralph’s Cocktails, my goal is to build more than just a brand, I want to create a movement. One that uplifts local ingredients, trains and inspires the next generation of mixologists, and puts African cocktail culture on the global map. This is just the beginning. I see Ralph’s Cocktails evolving into a legacy that celebrates who we are, where we’re from, and how far we can go.

‘‘

Meet Teejay Ameen (born Ameen Olatunji Yusuf), a dynamic broadcast journalist and culture curator with over seven years of experience in the entertainment industry. He is celebrated for his compelling presence as a VJ and for his powerful advocacy on behalf of people with albinism.

From your perspective as a broadcast journalist and entertainment executive, how have traditional Nigerian music genres like Fuji, Jùjú, and Highlife contributed to the rhythms and melodies for what the world now knows as Afrobeats today?

Afrobeats, as a genre, is fundamentally a fusion of diverse sounds that is rooted deeply in popular traditional music genres. These traditional styles form the backbone of what we now recognize as Afrobeats. If you listen closely, you’ll notice distinct elements of Fuji, Highlife, and Juju woven into many of today’s biggest Afrobeats hits. It’s this blend, the influence and integration of these rich, indigenous sounds that gives Afrobeats its authenticity and has

propelled it to a prominent place on the global music stage.

How has the use of Nigerian Pidgin and local languages in lyrics contributed to the unique identity of Afrobeats, and do you see this as a barrier or a bridge for international listeners?

Language is a vital part of our cultural identity as Nigerians and Africans more broadly, this naturally reflects in our music. Take Despacito, for instance: one of the most streamed songs in the world, sung entirely in Spanish, yet it resonated globally. In the same way, Pidgin is central to the Nigerian identity, just like our many local dialects. Language only becomes a barrier when we’re seeking international validation at the expense of authenticity which I don’t believe is the case here. So, no, language is not a barrier. A song like Laho by Shallipopi is clear proof that music transcends language because true music knows no boundaries.

Can you remember the first time you heard a fusion of traditional Nigerian sounds with modern pop and thought, “Wow, this is the future”?

The first song that came to mind is Gra Gra by Lagbaja. The intro has this unexpected EDM vibe, and I remember hearing it for the first time thinking we’re in for a beautiful journey of musical experimentation in

the future. It was such a bold, refreshing sound, and it really stuck with me.

Looking back at the last two decades, what do you consider to be the key milestone moments in the journey of Nigerian music from a local sound to a global phenomenon?

I have what some might call an unpopular opinion. I don’t believe there are key milestone moments that marked the shift of Nigerian music from a local sound to a global phenomenon. Instead, I see it as a continuous evolution in each era, each phase, and every artistes’ contribution has played a vital role in shaping the sound we celebrate today. Every accomplishment, big or small, has pushed the culture forward. So, in my view, every moment in the journey of Nigerian music has been a milestone in its own right.

Imagine you’re a tour guide. What’s the one place in Nigeria you would take a foreign friend to experience the most authentic connection between our culture and music?

I’d start by taking them to Lagos, the heartbeat and melting pot of Nigerian pop culture. Then I’d bring them to one of my favorite spots, Freedom Park, for an evening of good music, the signature Lagos breeze, and laid-back, chill vibes.

Toyin Ajewole

Music Business expert and Art Curator

A number of today’s artists could sell out arenas, but those legends built economies

Meet Toyin Ajewole, a dynamic Partnerships Associate at Mavin Records, Africa’s premier record label, where she masterfully bridges the gap between artists and brands, transforming creative visions into impactful deals. Beyond her pivotal role in business development for Mavin’s stellar roster, which includes global stars like Rema and Ayra Starr, Toyin is a passionate advocate for visual art, running Kanvas9 to spotlight African artists and their incredible work. Her blend of sharp negotiation skills and a deep appreciation for artistic expression makes her a true force in both the music and art worlds.

From a business standpoint, what’s the one thing you think modern Afrobeats artists could learn from the way traditional musicians built and maintained their fanbase for decades?

This is a good question! As a business person, I love to treat everything as a breathing living thing, including fanbases. I mean, it is technically made of breathing living people, haha. But imagine your fan base as a person you’re trying to date. The biggest thing is communication (can I get an amen?). Communication looks like different things for different artists; sending or randomly replying DMs or tweets, having meet & greets, giving out free stuff, having a certain type of party or event, making videos to address them, giving them hints for your projects etc. It could be anything, as long as it’s consistent and your fans understand that as your communication language. It makes them feel special, like part of an inner circle. I think a couple of our modern artists get it wrong by thinking the fans are just there to convert to cash. Create amazing music and use great communication to build your fan base community.

If you had to explain the commercial appeal of a genre like Highlife, Juju or Apala to an international investor using only three words, what would they be?

Timeless, cultural, scalable. These genres never age, and they carry Nigeria’s cultural DNA (which the world is obsessed with), and can be reinvented continually. Just look at how Afrobeats sampled them

to dominate globally.

If you could time travel back to the golden era of any traditional Nigerian music scene, where would you go and what business deal would you try to make?