Ettore Scola The Social Power of Image

Lorenzo Bellacci

Lorenzo Bellacci

Preface

“I believe I have worked along this line: towards an Italian comedy in which, behind the legacy of neorealism and the magic of satire, transpired the civil apologue”1

Ettore Scola’s films take the form of civil apologues that seek to convey the reality of their time through the intimate stories of marginalised people. A minimal optic that seeks to explore the course of history through the telling of individual events.

This dissertation intends to demonstrate how the moral values of Scola’s apologues are directly contained within the visual language of his movies. Spaces, existing architecture and scenography intertwines with the narrative fabric becoming a parallel form of narration to the screenplay. Using a term coined by Juhani Pallasma, we are referring to a cinematic language that expresses itself through the use of poetic images. Images that “open up streams of association and affect”2

Adopting an innovative practice of film study outlined by Myrto Konstantarakos in his book spaces in European Cinema, this dissertation intends to carry out a spatial analysis of Scola’s cinematic work with a dual objective. On one side it will explore how the built environment is integrated in the narrative structure of the film becoming the medium that conjugate the private stories of Scola’s character with their time. On the other side, by looking at the way the space is handled and used in the cinematic work it will be possible to derive the ideology of the time discerning its politics and social classes.

As Walter Benjamin explains: “The audience empathizes with the performer only by empathizing with the camera. It thus assumes the camera’s stance: it tests”3. the camera reflects the subjectivity of a director, and more generically that of an individual belonging to a specific time in history. Therefore, the choice behind a particular location or the use of a specific architecture can be regarded as the consequence of a recognizing of the values contained within it. This will allow for the exploration of a specific time in history starting from its notion of space

This dissertation will focus on two specific movies that among the conspicuous body of work produced by Ettore Scola better testify the integration of space for the purpose of narration; Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi (1976) and Una Giornata Particolare (1977). In a similar way in which David Bass structured his essay Insiders and Outsiders: Latent Urban Thinking in Movies of Modern Rome, also

p. 6

of image: existential space in cinema (Helsinki: Building Information Ltd, 2001), p. 12

Walter Benjamin, The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction (London: Penguin Books, 2008), p. 16

the content of this dissertation will be organised according to three scales of urban thinking; the City, the neighbourhood/village and the house. While all the three scales are present in both movies assuming different symbolic values, their degree of importance is not always equal. Therefore, avoiding to force ideas for the purpose of categorization, the structure will only help to clearly organize the content of the work while each chapter will be investigated and expanded in direct proportion to its ideological value.

While Scola’s legacy as a director has been the subject of several film studies, in the realm of architectural literature his work remains marginal and scarcely explore. The existing body of work in this latter field is very limited and it only focuses on analysing the direct relationship between architecture and cinema, its functional aspect in relation to the screenplay. However, it never delved in exploring the political and social dimension contained within the spaces of Scola’s films and did not go far enough in order to derive from them a political and social understanding of the time.

Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi - Giacinto’s shack

The name of this movie, which literally translates to ugly, dirty and mean, wants to be a parody of the expressions used by the bourgeois to describe the marginalized, the derelicts and the different ones. These adjectives come to define the characters of Scola’s film, a large Apulian family living in a shantytown in the periphery of Rome. The patriarch Giacinto, masterfully interpreted by Nino Manfredi, received a million lire from an insurance company as a compensation for losing an eye. Because of is petty and stingy character he refuses to share any of his savings with his relatives who repeatedly attempt to steal his saving with no success until they commonly agree to murder him.

The plot is really simple and the film lingers on documenting with a grotesque style, aimed at highlighting its dirtiest and ugliest aspects, the state of misery where this family is confined to live. It is thanks to this simplicity in the screenplay that the movie is able to construct a very well-articulated visual language where locations, scenography and architecture become a parallel form of narration to the screenplay.

The story begins from inside Giacinto’s shack, built by his owner, brick after brick with his own hands1. This is the feeling that the scenographer Luciano Ricceri conveyed in his reconstructed set design for the shantytown located on the Monte Cocci, a hill in the periphery of Rome. For practical reasons all the interior scenes were shot inside the theatre since filming on location was too precarious due to the primitive nature of the slum2

As in the movie Una Giornata Particolare, also in Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi Scola exploits the private realm of the house in order to define the psychologies of his characters. Their ferocious behaviour can be read in accordance with the surrounding environment and many of their actions can be understood as a direct consequence of their living conditions (figure 9).

By rotating the camera from a central point inside the house, Scola begins to record the awakening of the family completing a 360° anti-clockwise turn (figures 4-8). While in the foreground the characters clashes into each other during their morning activities, the entire house is revealed in the background. Inside this room, where most of the floor plan is covered with mattresses, Giacinto

and his numerous family of approximately 20 people sleep and live next to each other. Because of the cramped nature of the shack, the characters are forced to fight with each other in order to affirm their own personal space. This gives rise to a conflict of interests between the inhabitants based on the rule of the survival of the fittest. In this environment of extreme promiscuity nothing appears any more as a scandal in the eyes of Scola’s character, not even the sexual relationship consumed between members of the same family.

The shack is so small and its population so numerous that the house becomes a functional place only for sleeping. During the day this space is evacuated by all his inhabitants who leave towards different directions. some of them earn their living from precarious jobs, such as disposing waste (figure 10). Others, more relentless towards the only low paid professions that society is willing to offer them, decide to procure their living from illegal activities as thefts and prostitution. The only character that never leaves the house is the surly grandmother, who confined on her wheelchair watches TV all day. (figure 11)

The latter is an important element in the story and it is used by Scola to portray the demoniac aspect of the Mass media3. the television becomes the medium through which a bourgeoisie culture based on the value of consume enter the private realm of the house. this effect is ironized by the grandmother who tries to learn English because she says that is important for the future4

Scola’s scepticism towards the mass media finds its roots in Pasolini’s philosophies as we will be able to see in the next chapter.

Antonio Bertini, p. 145 5

As the title suggests, the story takes place during the time frame of a specific day, 8 May 1938, the date of Adolf Hitler’s visit in Rome. The entire movie is set within the same apartment block, the Palazzo Federici, that because of this special occasion is evacuated from all its inhabitants except for the two main characters; Antonietta and Gabriele. Antonietta, interpreted by Sophia Loren, is a tired housewife confined inside her house, the only place that belongs to the woman in the society envisioned by Fascism. On the other side, Gabriele, interpreted by Marcello Mastroianni, is a Radio broadcaster at EIAR (Ente Italiano per le Audizioni Radiofoniche) who has lost his job because of his homosexuality and his alleged anti-fascist stance. Once again, we witness the story of two individuals marginalized from society whose destinies will cross path during this special day.

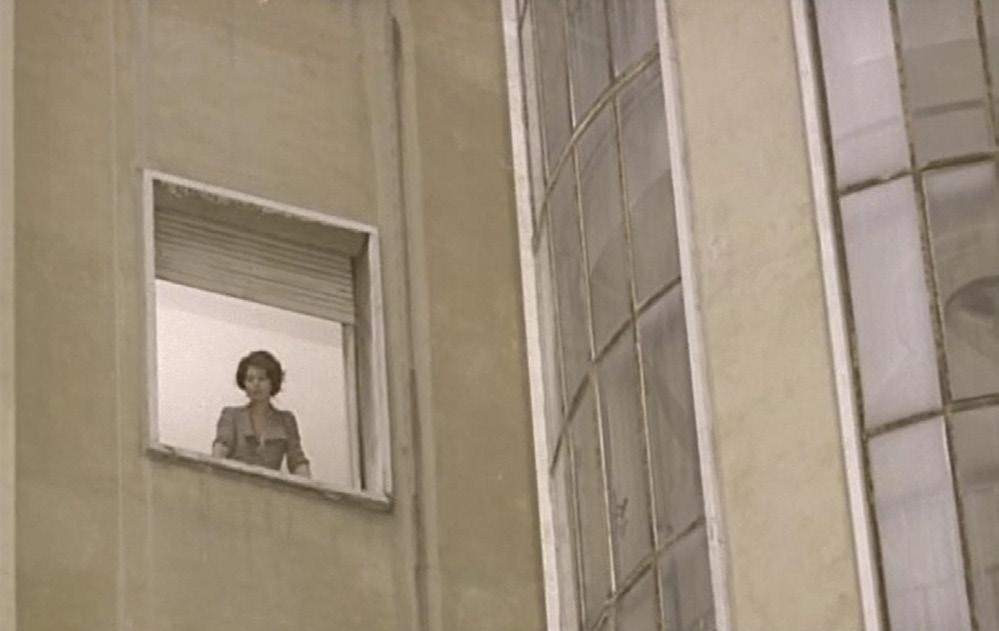

Antonietta’s social role is defined through the domestic environment of her house. this space is introduced through a long shot that “is a combination of different techniques: a dolly, an elevator, a trolley, one zoom; the camera starts from the real courtyard of Viale XXI Aprile and it raises with an external elevator. Then the camera stops. The scene starts again within the theatre from the reconstructed exterior of the apartment…”5.

From outside Antonietta’s window, the camera begins to enter her apartment with a slow zoom shifting from the public to the private sphere (figures 12-14). As the scenographer Luciano Ricceri recalls this was a very difficult shoot to execute as the camera did not fit through the window. This meant that the windowsill had to be removed just as it exited the cinematic field of view6

On this special day, but probably as any other of the week, Antonietta has woken up before the rest of her family to prepare coffee and Iron the clothes. With his camera Scola begins to tail her movements through the apartment as she wakes up her six children and her husband. Her journey reveals the entire floor plan of the house, a relatively small apartment for this numerous family. To allow the camera to move through the narrow spaces, Luciano Ricceri ironically explains that there were more doors than walls in the reconstructed interiors7

Dressed in their black shirts and leather boots the family leaves

the apartment joining the multitude of neighbours who are now reversing into the courtyard to go an assist the military parade. In a matter of a few minutes the lively apartment block is emptied of its inhabitants for the exception of Antonietta(figures 17-18). As she looks around and sees the mess left behind from her family she sighs and ironically points out “there is only one mum, but here we would need three”8. (figure 19)

In this initial sequence, Scola is able to construct a very detailed picture of Antonietta’s social condition through her domestic environment. From this space is possible to understand her role as a woman during fascism, excluded from the communal rituals and confined home to provide for her family. While this condition is presented through her private sphere, it becomes evident that her remissive behaviour is the consequence of a form of culture envisioned by regime. The body of the woman is objectified for the production of new babies for the fatherland and at the moment she is only missing one child to receive a natality price. Therefore, the role of the woman is stripped of any sexuality and while her husband satisfies his lust outside the home, spending more time at the whorehouse than in the office, the marginalised woman is only allowed to have one lover9; Mussolini. Antonietta pastes images of the Duce inside a notebook along with some of his quotes “Fascist women, you must be the custodians of the home”10 or “the man is not a man if he is not a husband, a father, a soldier”11

Left behind inside her apartment, Antonietta will meet Gabriele during the course of this particular day. As argued by Maria Antonietta Macciocchi12, The encounter between these two outcasts it is not based on the economy of exchange since their sexual preferences do not match,. This condition gives way to a genuine exchange where the characters are free to open up themselves allowing the viewer to delve inside their inner worlds, to explore the dignity and the humanity that the regime has detracted from them. In the process of knowing each other the characters also discover themselves, more specifically they become aware of the boundaries of their social confinement.

As if a woman and a homosexual were not enough at odds with the fascist culture of the time, the actors chosen for the film

8

Una giornata particolare, dir. by Ettore Scola (Gold Film, 1977)

Maria Antonietta Macciocchi, ‘nota su una giornata particolare’, in Una Giornata Particolare: soggetto e sceneggiatura, ed. by La Ginestra (Milan: Longanesi & C, 1977), p. 131

10 11

9 12

Una giornata particolare

Una giornata particolare

Maria Antonietta Macciocchi, p. 128

represented an equally challenging choice. Scola decided to work with two personalities, Marcello Mastroianni and Sophia Loren, that during their career came to impersonate respectively the role of the Hollywood Diva (figure 20) and the Italian Latin lover (figure 15). Scola was able to completely transform these mental images into a tired house wife, without make up and wearing worn clothes, and a Latin lover deprived of masculine character.

While this movie can easily be read as a critic against the discriminative character of the fascist regime, the success of this story relies in its universal applicability. As explained by Scola, the original intent was to tell the story of “A modest woman, without any cultural baggage, resigned to being a victim”13 in a special day of our time. This would have probably been a Sunday afternoon when the men go to the stadium leaving the mother behind. The idea of setting the story during fascism came only in a second moment, after discussing the screenplay with his collaborators Ruggero Maccari and Maurizio Costanzo14. By setting the story in a time when the tolerance towards different people was minimal, the director succeeds in making even more emblematic two themes that had characterised the politics of 70s; the emancipation of woman and LGBT rights.

Therefore, thirty-four years after the end of fascism, this movie questioned if the discrimination towards minorities had really ceased to exist within contemporary society.

13

14

Antonio Bertini, p. 140

Ettore Scola, ‘una giornata del 38’, in Una Giornata Particolare: soggetto e sceneggiatura, ed. by La Ginestra (Milan: Longanesi & C, 1977), p. 134

THE NEIGHBOURHOOD / THE VILLAGE

Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi - The village

From the ‘private’ realm of the house, the camera moves outside to show the context of Giacintio’s shack; an informal settlement on a hill facing the city of Rome (figure 23). This place recalls a prehistoric village, organized around a patch of dirt road with a water fountain in the middle. The only difference are the houses, that instead of being constructed from local vegetation are assembled with found waste materials (figures 24-26). In addition to these precarious constructions, to make the condition even more miserable is a common ground contaminated with rubbish, rats and excrements (figure 27).

After inspecting different locations, it was decided to stage the shantytown on the Monte Cocci, a hill in the periphery of Rome. As the scenographer Luciano Ricceri explains: “…it was an empty hill, I do not even remember why… so we had all the space to build this village and we did it all. I care so much to emphasize things like the kindergarten… where these children were locked inside”1

Unlike a Una Giornata Particolare, where the scenography had to be carefully planned in advance to allow all the interior camera movements, the Village of Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi was built with the same spontaneity that this place sought to convey. As Ricceri continues to explain:

“There was no design. I brought lorries filled with metal sheets, bricks, pieces of cardboard. All waste materials and we started to build. I was there and I used to say ‘put on a piece of sheet metal here’. it was all like that because you could not design anything in advance, it would have looked bad. It had to be done as if they had constructed it. If you designed everything you could not remotely imagine that a piece of cardboard put there would have worked. How could you tell in advance? We did everything by hand” 2

In line with the spontaneous spirit of the project, people coming from existing informal settlements around Rome were scripted either as actors or employed for the construction of the set3 People living in slums was not a novelty for the time, but simply a social problem relegated to its own geographical confinement; the outskirts of the city. This phenomenon had already been present during the fascist regime that sought to resolve it by subsidising the construction of new housing projects in the periphery of the

city. However, In the post-war period, following the devastation brought by the conflict, this social issue peaked becoming “Italy’s most practically and symbolically important architectural problem”4.

As a prove of how cinema and architecture address the same themes employing the different means of their professions, the housing crisis became also an important subject in Italian Cinema. One example is De Sica’s movie Miracolo a Milano (1951) that talked about the life of a group of people displaced by the war living in a slum in the periphery of Milan (figure 28). This city had suffered heavier damages with respect to Rome during the conflict especially because of its proximity to Salo’, the new capital of the Italian Social Republic instituted in 1943.

But there were also other important causes that led to the formation of this pressing social issue among which the Sventramenti carried out by the fascist regime and the emigration of large groups of people from depressed rural areas to the city. The expectations of a more prosperous future in the city were not always met and people began to settle at its edges. This is the story of Giacinto’s Family that came to Rome hoping “to participate in the great national banquet, but they do not even find a place at the table, they have to be satisfied with crumbs”5 .

In 1957, the city of Rome counted fifty shanty towns that housed approximately fifteen thousand families coming from Lazio, Abruzzo and different parts of southern Italy. During the sixties the ISTAT (the Italian Institute of Statistic) reported thirteen thousand families living in informal settlements that were reduced to three thousand two hundred in 1976, the same year when Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi Came out6

With this movie Scola sought to continue the discourse opened by Pasolini with the movie Accattone (1961) on the borgate romane (Roman slums). The latter movie (figure 29) announced the beginning of a process that Pasolini defined as the Genocidio Culturale (cultural genocide). the cancellation of the culture of the underclass, stripped from its rural traditions which were replaced with values belonging to the bourgeoise. Values based on consume and social conventions that did not belong to them.

4 5 6

Mark Shiel, Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City (New York: Wallflower Press, 2006), p. 76

Antonio Bertini, Ettore Scola il cinema ed io: conversazione con Antonio Bertini (Roma: Officina Edizioni, 1996), p. 131

Alberto Ricciardi, Le baraccopoli romane: brutte, sporche e cattive (2016), <http://www.inkorsivo. com/agora/le-baraccopoliromane-brutte-sporche-ecattive/> [accessed 6 March 2018]

Antonio Bertini, p. 129

Alberto Moravia, quoted in Comune di Reggio Emilia, Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi (2008) <https:// www.comune.re.it/cinema/ catfilm.nsf/PES> [accessed 10 April 2018]

Stefano Masi, Ettore Scola: Uno sguardo acuto e ironico sull’Italia e gli italiani degli ultimi quarant’anni (Roma: Gremese Editore, 2006), p. 55

7

8

“On this same process I decided to do a movie as well, about ten years after Accattone. I spoke about it with Pasolini, I told him that I wanted to continue his discourse on the underclass of a roman slum”7.

9

Pasolini was interested in the movie and he accepted Scola’s request of appearing in the opening scene. In a similar way the newsreel precedes the story of Una Giornata Particolare, Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi should have started with a preface. Here Pasolini standing among the houses of the village, dressed in a white vest, would have announced his prophecies regarding the effect of the consumer society. Unfortunately, this preface was never shot as Pasolini was assassinated on the 2nd November 1975 on the Roman coast, a few kilometres away from Torvaianica where Scola and his troop were filming. If Accattone had signed the beginning of a process, Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi was the same disease at its terminal stage.

While the two directors touch upon the same theme, they employ a different cinematographic style. This difference is stressed by Alberto Moravia’s, who reviewing the movie on L’Espresso in 1975 writes:

“In this remarkable film, the insistence on dirty and repugnant physical details could even speak of a new aestheticism in accordance with the times, which is added to the many already dead: that of the “ugly”, the “dirty” and the “bad”. However, we are in a climate of apathetic contemplation rather than dramatic intervention”8. (figures 30-31)

If on one side Pasolini tells the story of marginalised people through a poetic prose able to generate in the viewer a sense of empathy for his characters, Scola adopts a grotesque style that can only enhance the dirtiest and ugliest aspects of these individuals. Scola does not acquit any of his characters in a similar way in which Jonathan Swift in 1729, with his modest proposal, suggested to ease the Irish economic problems by selling their children as food9 With the same provocative attitude Scola sought to denounce the condition of a social class deprived of his culture and confined to perish in this village.

A Special Day - A neighbourhood movie

During his analysis of Italian cinema in terms of urban categories, David Bass defines Una Giornata particolare as a neighbourhood movie10 since the camera never leaves the realm of Palazzo Federici. (figure 32)

Designed by the rationalist architect Mario de Renzi between 1931 and 1933, this apartment block in Rome was conceived on the basis of a housing program ascribable to the “Piani di Edilizia Economica Popolare”11. This was one of a series of initiatives taken from the fascist regime to tackle the housing crises that Rome, as many other Italian cities, were experiencing at the time. Among its causes is important to recall the mobilization of People from rural areas to the city, the release of regulated rents proposed in 1927 and the need of rehousing people after the sventramenti. This Italian word refers to Haussmann-like urban interventions carried out by the regime to modernise the fabric of the city. In the case of the Palazzo Federici, it was constructed to house a specific social class which consisted in people working for government offices12 Therefore, during standard office hours, the building would have appeared empty as in the movie for the exception of the door keeper and a few women. Among the residential projects funded by the regime, Palazzo Federici certainly stands out because of its vastness. When it opened in 1937, the complex counted 29 staircases, 650 apartments, 100 shops and a cinema with 2000 seats13 (figure 33). This latter element comes to testify the importance given to the mass medias in the creation of a fascist culture.

Looking at the architecture of the Palazzo Federici, it compromises a mixture of stylistic features borrowed from the two main architectural trends of the time. On one side the intransigent rationalism typical of northern Italy, akin to European modernism and with a preference for the Latin character of le Corbusier’s vers une architecture. This stylistic influence can be found in the balconies wrapped around the corners of the building or the helicoidal staircases contained inside glass cylinder (figure 34). On the other side the more traditional and reactionary architecture promoted by Marcello Piacentini characterised by a strong classicism (figure 35). This type of architecture adopted simplified elements from the Roman tradition as in the case of the bricks wrapping the basement of the apartment block14

10

David Bass, ‘Insiders and Outsiders: Latent Urban Thinking in Movies of Modern Rome’, in Cinema & Architecture; Melies, Mallet-Stevens, Multimedia, edited by Francois Penz and Maureen Thomas (London: British Film Institute, 1997)

11

Christian Uva, ‘Un borgo nella Metropoli. Ettore Scola a Palazzo Federici’, The Italianist, 35.2 (2015), 284-290 (p. 284)

12

13

Luciano Ricceri, see appendix p. 62

Carunchio, Tancredi, De Renzi (Roma: Editalia, 1981) p. 14

14 Maria Teresa Cutri’, Casa convenzionata (Palazzo Federici) (2014) < http://www.archidiap. com/opera/casa-convenzionatapalazzo-federici/> [accessed 10 April 2018]

It is thanks to these stylistic traits, typical of their time, that the apartment block becomes a symbolic representation of the fascist regime. A ghostly presence that will haunt the characters for the entire length of the movie. Scola consciously uses the Palazzo Federici in all his fascist rhetoric highlighting with diagonal shoots its dynamic, severe and rigorous character (figures 36-37). By moving within its architecture, Antonietta and Gabriele not only interact between each other, but their stories clash with the values and moralities envisioned by the regime.

While Scola exploits the envelope of the Palazzo Federici in all its symbolic value, the interiors of the Apartment were reconstructed inside the De Paolis studios in Rome15. As the scenographer Luciano Ricceri explains, this was done because of the functional problems posed by filming certain scenes on location. The most important factor to consider was the relationship between the two apartments that had to face each other16 (figures 38-39). It was because of the morphology of this building that the characters encountered each other, when Antonietta’s bird flies away landing next to Gabriele’s window. In order to recreate the visual connection, the apartments were reconstructed inside the studios along with the portion of façade needed to convey the feeling of the courtyard in the middle. This was only made possible by renting two different theatres that could be connected outdoor through giant doors. The exterior space in between was used to reproduce the courtyard, while the apartments were built one inside each theatre17. This combination between reality and Mise-en-Scene is an interesting aspect of Scola’s work. The former confers to the plot a greater sense of realism and helps to define the historical context of the story. The scenography is then constructed in a strategic way in order to respond and deduce its meaning from the existing architecture. Under a stylistic perspective this technique inherits from neorealism the idea of faithfully portraying reality, while the use of the mise in scene represents a move forward from it. In this sense, the combination of real and fictional elements grants to Scola a greater control over the built environment in regards to his neorealist predecessors. This allowed him to exploit the existing architecture to a greater extent in order to obtain a visual language richer in references and meanings. At the same time, the greater control on how the existing is perceived meant a more subjective reality in the work of art of the director.

THE CITY

The image of the city

While in Una Giornata Particolare fragments of the city run fast in the images of the newsreel, in Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi this urban scale is a permanent element in the visual language of the film. Thanks to the elevated position of the Monte Cocci in front of Rome (figure 41), for the entire duration of the story it is possible to see the city acting as a backdrop to the village. Adopting an expression previously used by Ricceri, the shantytown can be compared to the Suburra in ancient Rome. You went through a stinking alley and at the end of it you could find a temple of white marbles1.

Continuing to talk about the film, Luciano Ricceri explains how, even before starting shooting “there was the need to relate the shantytown with a city that was basically Rome”2. By building the slum in front of this city, Scola manages to connect the private story of Giacinto’s family with the reality of his time. the image of the city intertwines with the narrative fabric and we begin to read this isolated reality in relation to current society and its form of government, indirectly stated in the background. The element of the city becomes the medium of connection between cinema intended as fiction and politics.

Peter’s Dome

In the view of Rome in the background, St. Peter’s dome, symbol of the power of the papal state, holds a role of primary importance (figures 42-43). This element frequently recurs in many scenes of the film and assists impassively to the situation of misery in the foreground. While we were able to verify that the idea of the city as a backdrop to the film was already present in the screenplay “…this thing of the dome came during the site inspections, discovering this place…the Monte cocci which is very close to the St Peter’s dome and this is what guided us. It was a deserted hill, there was nothing above but St. Peter’s dome was very close, very present, let’s say it was looming”3.

Recognized the expressive value of the architecture of San Pietro, the film set was built “according to the dome so that you could see it from many different angles. From this village of shacks, you could see the dome in the distance dominating this desperate place”4.

1 2 3 4

Author interview with Luciano Ricceri, set designer, 6 June 2018 see appendix p. 63

Luciano Ricceri, see appendix p. 61

Luciano Ricceri, see appendix p. 61

Luciano Ricceri, see appendix p. 63

This architectural component greatly enriches the semantic level of the film, especially in the last scene. As a testimony to how Scola’s “ endings are quite similar to the beginnings ... just because these are movies that resemble our lives”5 the film ends in the same way it was opened. In the final scene (figure 45), the camera follows Maria Libera on her way to the fountain to get some water for the house (figures 46-47). Her appearance has not changed, she is still the same child we saw at the beginning of the film (figure 44), but unlike the initial scene, she now bears the sign of a pregnancy. A womb that surely is not the result of a happy love but the consequence of a sexual abuse. At a certain point the final scene freezes and while Maria is portrayed in the foreground in front of the fountain, in the background, exactly at the centre of the screen the St Peter’s Dome appears in all its majesty. As Scola explained: “I wanted the “big dome”, the symbol of the power of the church and its high admonishment on life, abortion and on moral laws, to continuously loom over the slum and its miseries”6.

Without dialogues, Scola succeeds in telling through a careful composition of the image the co-responsibility of the church on the issue of abortion. A behavior judged highly hypocritical by the director in the face of a society that was changing. The historical period of the 70s, defined by Giovanni Canova as the long decade of the short century7 was a revolutionary moment in Italian history that saw several struggles on social rights materialize into laws. Among these achievements it is worth mentioning: Conscientious objection to military service (1972 law No. 772), divorce (1970 law No. 898), abortion (1978 law No. 194), vote extended to men and women over 18, decriminalization of drugs (1975 law No. 685). From these dates it is possible to see how Scola was directly involved with the politics of his time exploring in his cinematic work a social theme, such as abortion, which had not yet been legalized in 1976, the release date of his film.

This critical position towards the church can also be read as a proof of an historical period characterized by a government still far from being secular. Despite the end of the temporal power of the papal state with the unification of Italy in 1861, its influence on the Italian people remains a strong political force that must be taken into consideration by the current government; Christian Democracy

5 6 7

Bruno Palmieri (1963)intervista a Ettore Scola (2013) <https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=njb8rDunj8s> [accessed 10 April 2018]

Antonio Bertini, Ettore Scola il cinema ed io: conversazione con Antonio Bertini (Roma: Officina Edizioni, 1996), p. 133

G. Canova, Anni settanta, il decennio lungo del secolo breve, 2017, quoted in Uva, Christian, l’immagine politica; forme del contropotere tra cinema, video e fotografia nell’Italia degli anni settanta (Milano: Mimesis Edizioni, 2015)

The poetic image8 associated with seeing the city from outside is not a new subject in Italian Cinema. Before Scola, this theme had been explored by Rossellini in his movie Rome, Open City and by Pasolini in two of his movies Accattone (1961) and Mamma Roma (1962). But how does Scola’s image of the city differ in meaning with respect to the one used from the other two directors?

8 9

In the final scene of Rossellini’s Rome, Open city (1945), after assisting to the execution of Don Pietro, the young boys are portrayed returning home on the edge of a hill in front of Rome (figure 48). Also in Scola’s movie Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi a group of children is filmed running towards their kinder garden with the cityscape forming an evocative backdrop to the scene (figure 49). Even though both images were filmed from different vantage points, their composition is very similar.

In the case of Rossellini, the idea of the city seen from outside finds its roots in “Neorealism’s documentary-like preoccupation with the everyday life of a society”9. this understanding of cinema meant that the movie was primarily filmed on location in working class districts. These were the most plausible places where the ordinary Romans fighting against the German oppression were to be found. In recording the resistance of these common but heroic citizens, the camera follows the characters in many furtive journeys on the city streets. At the same time there are many interior scenes as in the case of the offices of the gestapo reconstructed and filmed in studio, the underground spaces where the communist newspaper L’unita’ is printed, the apartments where the romans hide their fellow citizens hunted by the Germans and Don Pietro’s church. Throughout the whole duration of the film we are fully immersed inside Rome’s urban fabric experiencing its different spaces and their respective activities. When the movie ends, all the location we have travelled so far through a process of Derive’, as Guy Debord would define it, are finally reconnected into a coherent urban form; the city of Rome. by ending the movie with this overarching image, Rossellini sought to give an identity, in the form of a single cinematic shoot, to the place whose reality he committed to tell.

Juhani Pallasmaa, The architecture of image: existential space in cinema (Helsinki: Building Information Ltd, 2001)

Mark Shiel, Italian Neorealism: Rebuilding the Cinematic City (New York: Wallflower Press, 2006), p. 17

From this perspective, Scola inherits from neorealism a preoccupation with reporting the reality of his time. As he explained: “To transform into images what I see around me, it is something that exalts me… I like to talk about reality because it is what I love the most”10 Therefore, In the same way as Rossellini, also for Scola the city represents an historical document of his time. it is a symbol of actuality that brings a sense of realism to the cinematic work. while the actors are deliberately acting, buildings are ultimately real.

At the same time the two directors do no project the same values on the image of the city. This stylistic inconsistency is the result of a different perception of the future that can be explained if we look at the foreground of both scenes. Manuela Gieri compared these two images in her book on Contemporary Italian Filmmaking

“Unlike the children in Rossellini’s neorealist masterpiece, these children are no longer ‘fighters for freedom’ but, enclosed in a ‘concentration camp’ have become the victims of a failed dream for freedom and social renewal”11.

Rossellini’s children are portrayed while marching towards the future and they come to represent a vision of hope. therefore, it can be argued that by filming his children in front of the city, Rossellini projects on the latter a sense of “liberty and unity”12 The vision of a society that after a tyrannical regime and the devastation of war is ready to rise again, united in the creation of a free and fair nation.

In his analysis of the movie Rome, Open City, Mark Shiel points out that while the movie can be considered a drama story because of the deaths of Manfredi and Don Pietro, it ends with a confident vision in a better future. This vision is professed through the words Francesco tells Pina “Spring will come, more beautiful because we’ll be free… we mustn’t be afraid now or in the future because we’re in the right, on the right road. We’re fighting for something that must come. It may be a long hard road but we’ll get there and we’ll see a new world, our children will see it”13 This feeling is then translated into visual form in the final scene of the movie where Rome seen from far offers a breath of fresh air from the violence contained within it.

10 11 12

13

Roberto Ellero, Ettore Scola (Roma: Il Castoro, 1996), p. 7

Manuela Gieri, contemporary italian filmmaking: strategies of subversion. Pirandello, Fellini, Scola and the directors of the new generation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), p. 183

Mark Shiel, p. 52

Roma città aperta, dir. by Roberto Rossellini (Minerva Film SPA, 1945), quoted in Mark Shiel, p. 52

In the case of Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi, the idealism that had characterised Rossellini’s cinema has now vanished and we become the spectator of a group of people deprived of any moral values. The characters of Scola’s movie are not any more the heroic but ordinary Romans who fought against the Nazis, but a group of people wrangling between each other in a struggle for survival. It is also important to notice that while Rossellini’s movie zooms out from the city only at the end, Scola’s character never leave its margins, secluded in a state of solitary confinement from the rest of society.

This different affiliation with the city between Rossellini and Scola represents also a shift of the position of leftist intellectuals within Italian society Starting from the post war years up to the period of the 70s. “For Pasolini, as for many others of the neorealist generation and their 1960s descendants, the end of the war, after a brief moment in which everything seemed possible, soon saw a disappointing return to power of Italian capitalism and the catholic church, but now backed by the silent partnership of the United States”14 The future society envisioned by Rossellini has grown but imperfect, shifting from one form of totalitarianism to the next. The geographical area of the city does not represent anymore a unified society, but the hegemony of a bourgeoisie culture and its zone of influence.

Therefore, Scola deliberately places his story outside its area of control in order to create a relation of antagonism aimed at denouncing this new form of power. The figure of the intellectual that used to be directly involved with the social progress of the country has now retreated exiting society, leaving the city.

Pasolini and Scola - same discourse, different style

Pasolini’s stories in the borgate are always set on the boundary between city and countryside. This idea of margin is reflected in the visual language of these movies that portray rural areas contaminated by rubbish and roman ruins against a distant view of the cityscape. This contrast between primitive foreground and urbanized background is also present in the movie Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi.

Scola’s disenchanted vision of society and its future finds a greater affinity with the work of Pasolini that focused on the destruction of the culture of the underclass, distorted and absorbed by the messages of the bourgeoise. While the cinematic style differs between the two directors, as we were able to see in the previous chapter, the city comes to embody the same set of values. it becomes both the symbol of the marginalisation of the characters as well as the cause of their social conditions.

City as synonym of marginality

As Myrto Konstantarakos argues reviewing Pasolini’s cinematic work “Those who live at the margins of the city are at the margins of society”15 This statement helps to understand the idea of margin both a physical and a mental state. This condition is represented by a distant view of Rome in the movie of Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi. While the city ties the village within the realm of his time, these two urban scales only share a visual relationship. Rome exists only as a two-dimensional background image that come to symbolize the social and geographical segregation of Scola’s characters.

The margins explored by Scola and Pasolini are neither city or countryside, but an in-between shapeless place of primitive character (figures 50-51). they are outside of the sphere of influence of the city, isolated from its modes of production and social norms. Their inhabitants, using a Marxist term, belong to the lumpenproletariat. Unlike the working classes, who have stable jobs and incomes, the lumpenproletariat is unorganized and unpolitical. Therefore, they represent no real value, either political or economical for the state hence their condition of confinement. This idea of marginality was a driving force in the articulation of the visual language of Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi. Luciano Ricceri explains that many scenes were filmed deliberately on the edge of the hill in order to highlight this condition of both physical and mental exile. “The alleys, the streets, the billboard where they make love were all built on the edge of this hill”16 (figure 52) One example is the encounter between Giacinto and his future lover Iside. This scene takes place exactly on the edge of the Monte Cocci, where it is possible to see the countryside adjacent to the city. Inebriated by alcohol, Giacinto finds himself at the foot

15 16

Konstantarakos, Myrto, ‘Is Pasolini an Urban Film-maker’, in Spaces in European Cinema, edited by Myrto Konstantarakos (Exeter: Intellect Books, 2000)

Luciano Ricceri, see appendix p. 63

of a giant billboard of which we can only see the structure behind since it faces the city. He begins to look around and sees as if it was a mirage a woman turned from behind. He slowly approaches her until the two begin to look at each other. At a certain point Giacinto, slightly embarrassed, turns around and with a hand gesture: “He donates her Rome that is standing at their feet: like if he was a monarch”17. (figure 53)

Giacinto alludes to the city as something beautiful, apparently so close but separated by an unbridgeable distance. Another intense gaze follows, the camera jumps cut and opens again showing the two characters after they made love directly in that place, apparently shabby but at the same time with such a romantic view. This scene ends with Giacinto who decides to take Iside back home with him. While the two are holding hands and begin to head back towards the village, the countryside in the foreground is invaded with a flock of sheep followed by two shepherds (figure 54). This encounter explains the idea of Scola’s margins as shapeless places where rural elements merge with billboards and rubbish produced by society of consume

17

Antonio Bertini, p. 135 Antonio Bertini, p. 136

Both Pasolini and Scola’s characters, are often pimps, prostitutes and thieves who live in the world of illegality. Their behaviors, which are frequently fierce and unscrupulous, are however the consequence of the social condition in which they are confined to live. As Scola explains, they are “blameless, because they are victims in turn”18. They are Victims of a system of which they are not part but whose bitter consequences they pay for. So, if the city comes to represent this system, it consequently comes to incarnate the very cause of this social condition.

In the cinematic work of Pasolini, this idea is transferred onto the screen in the final scene of his movie Mamma Roma With this civil apologue, Pasolini intended to tell the destruction of the culture of the underclass, absorbed and by the values of the bourgeoisie. While a middle-class family has the necessary economic means to support a lifestyle based on the values of consume, for a boy from the borgate the satisfaction of the same needs translates

into crime, prison and ultimately death. this is the story of Ettore, Mamma Roma’s son.

The eponymous heroin after being freed from her pimp decides to change her life by relocating within the periphery of Rome. She decides to bring with her beloved son who was raised in Guidonia, a village near Rome. Contrarious to Mamma Roma’s expectations, who believed that the expanding bustling city could provide a better future for her son, Ettore’s background is replaced with a new form of culture. He becomes always more relentless against ordinary low paid jobs and decides to earn his living from small crimes which he will pay with his own life. What kills Ettore are not Nazis as in the movie Rome, open city but a new type of culture; the consumerism society

After being informed of her son’s death, in a state of despair the eponymous heroin looks outside her window (figure 58). What she sees isn’t simply a view of Rome’s periphery where the St Peter’s Dome is mimed by that of the Basilica of San Giovanni Bosco that retains a similar central role. She sees the cause of his son’s death (figure 59). The city becomes the physical personification of the consumer society that Pasolini sought to denounce. The symbol of the corruption of the underclasses with a new form of culture that do not belong to them.

Also the film Brutti, Sporchi e Cattivi collocates the bourgeoisie culture in the geographical area of the city. As Ricceri explains “In the film there was the need of having the village related to this city that dominated and had created it. The idea that what was behind had created what was in the foreground was part of the story”19

While the city neglects the existence of Giacinto’s family, the survival of these individuals is strictly dependent from its economy. Stripped of their rural culture, during the day they venture inside its urban fabric to earn their living from provisional jobs or committing crimes. At night they return within their confinement but their dreams remain always inside that distant city. Dreams of affording new consumer goods that will provide them with a free pass to the communal party on the other side of that hill. (figures 55-57)

The city in ‘Una Giornata Particolare’

Before entering the courtyard of The Palazzo Federici, Images of the city are presented in the form of a newsreel in the opening sequence of the movie. This form of reportage, assembled by the director using historical footages20, documents Hitler’s descent towards Rome to meet Mussolini

Scola introduces the historical context of his story adopting a cinematographic medium that had been at the forefront of fascist propaganda. As Mark Shiel argues in his book on Italian neorealism “Cinema had become central to Italian Fascism’s political, economic and cultural agendas and its promotion of conservative social values”21. The regime was fast in realizing the power of cinema as an agent of social construction able to mould a common ideology in line with fascist ideals. This was definitely a much more effective way in the process of asserting power rather than political repression alone. Mussolini himself described cinema as “the most powerful weapon”22 and founded in 1924 the Instituto LUCE (L’Unione cinematografica Educativa). This organisation was created with the educative purpose of presenting to the Italian population, in the form of newsreels and documentaries, the achievements of fascism and the figure of the DUCE.

In these relative short videos created for the purpose of political propaganda, the visual image holds a role of primary importance. As Leonardo Ciacci explains in his essay the Rome of Mussolini “In a film, especially if particular short and insistent, words have an extremely marginal role in establishing links in the memory process. What count are the images, the overall effect, the emotional involvement, which the music and editing are able to produce in the audience”23

From the images of the historical footages that fills the first six minutes of the movie is therefore possible to extract the cultural ideology that the regime sought to promote, one that combined an epic prose of the past with modern ideals of speed and functionality. The first idea is expressed by the images taken within the historical centre of the city which will be defined as one of the most sacred areas for the vestiges of Imperial Rome by the voice of the commentator (Guido Notari)24. The historical monuments recall Italy’s glorious past that Fascism has now revived with its

20 21 22 23

Ettore Scola, ‘una giornata del 38’, in Una Giornata Particolare: soggetto e sceneggiatura, ed. by La Ginestra (Milan: Longanesi & C, 1977), p. 137

Mark Shiel, p. 22

Mark Shiel, p. 22

Ciacci, Leonardo, ‘The Rome of Mussolini: An entrenched stereotype in film’, in Spaces in European Cinema, edited by Myrto Konstantarakos (Exeter: Intellect Books, 2000), p. 96

24

Una giornata particolare, dir. by Ettore Scola (Gold Film, 1977)

new colonies in Africa and Albania (Figure 60). At the same time, the old city forms an evocative scenography for military parades enacted to show off Italian martial culture to the new German alley (Figure 61). On the other side ideals of modernity and functionality are portrayed through Hitler’s arrival in Rome by Train. From the camera located inside the Fuhrer ’s carriage, Hitler’s profile appears as a black silhouette (Figure 62) running in front of crowds of excited people who are greeting at his arrivals. As a backdrop to these multitudes appears the new infrastructures (figure 63) built by fascism to modernise the country as in the case of the Stazione Ostiense that was quickly designed by Roberto Narducci to receive the Fuhrer on that special occasion25 (Figure 64)

Using images of the city portrayed though the lenses of fascist rhetoric, Scola is able to reconstruct the state of mind and the values of a specific time in Italian history. It is against this climate of fervent nationalism and an immoral feeling of superiority towards other races and weaker people, that we start reading Scola’s story of two solitudes; Antonietta e Gabriele. As the director explained:

“At the end this is one of the themes that come back in my films: the comparison between the great story that passes above our heads and the small individual events. We are conditioned by decisions that we do not take part in, which are taken elsewhere, but which we suffer for, that change our feelings”26.