LONGWOOD CHIMES 306

Winter 2023

Features

Like a museum, a garden showcases collections. In a garden, those treasures and works of art are often living things. Regardless of their nature or where they reside, collections tell a story about an institution’s history, its commitment to preservation, its desire to share with and inspire the public—thus providing insight into what it values.

In this issue of Chimes, we explore some of the many collections of Longwood—from a generous infusion to our bonsai program, to the notable group of landscape architects who have created stunning works here, to our Meadow Garden “hotspot” where birds and birdwatchers gather—paying homage to the art of collections and the meaning they hold for the future.

6 A Place for Plants and People

Why gardens are important places beyond their plants.

By Amanda Hannah and Rae Vassar

16 Living Sculpture

A generous gift begins the next chapter of our storied bonsai collection.

By Jourdan Cole

8 Birds of a Feather Of ravens and rusty blackbirds: Longwood is a “hotspot” for birding enthusiasts.

By Lynn Schuessler

22

Of Gardens and Designers

A group of influential designers have left their mark on Longwood via a collection of significant garden spaces.

34

Public Enjoyment

Pierre du Pont passed away in April 1954. With his usual foresight, he had in place a well-funded and adaptable mechanism for Longwood to thrive into the 1960s and beyond.

By Colvin Randall

End Notes

44

All Aboard

Now in its 23rd year, our Garden Railway keeps chugging along. By Patricia Evans

3

In Brief No. 306

In Brief

A small sampling of engines, boxcars, tankers, and cabooses from the Garden Railway G-scale collection.

Photo by David Ward.

A small sampling of engines, boxcars, tankers, and cabooses from the Garden Railway G-scale collection.

Photo by David Ward.

A Place for Plants and People

Like museums and libraries, public gardens showcase collections, often touting the number and types of plants they house — numbers that are often focused on and shared by others. For example, Visit Philadelphia, the region’s official tourism marketing agency, highlights Longwood’s “9,000 species and varieties of plants” in the very first sentence of its entry on the garden. Public gardens, however, have an important second collection that goes beyond their number of plants: people. Gardens bring people together to connect with both the natural world and each other. Why is it important to think of gardens as collections of people, and how can gardens be more intentional in cultivating this collection?

In his 1989 book The Great Good Place, sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term “third places” to refer to informal public gathering places outside of the home (“first place”) and work (“second place”). Whatever their ostensible purpose, third places—community centers, bookstores, barber shops, coffee houses, gyms—collect people “easily, inexpensively, regularly, and pleasurably.” By serving as neutral ground for informal gatherings, Oldenburg situates third places not only as the “heart of a community's social vitality,” but as essential to a functioning democracy.

In a world that is increasingly politically polarized, economically stratified, and

By Amanda

racially segregated, public gardens remain neutral places that can welcome all visitors. Robert Putnam argues in Bowling Alone that organizations focused on civil and social engagement, from Rotary clubs to bowling leagues, have declined in America. Many groups that have persisted are now more partisan (for example, the Sierra Club or the National Rifle Association) and may lack the inclusive, informal, and enjoyable gatherings that build bridges within and between communities and create social cohesion. By collecting people across political, class, ethnic, religious, and generational divides, gardens can strengthen social networks (of the classic, face-to-face variety) and serve as critically needed third places.

From a history of drawing together seekers of scientific knowledge; to entertaining the well-heeled; to gathering the downtrodden masses seeking clean air, respite, and beauty; public gardens have always collected disparate audiences. And just as ideas about what constitutes a plant collection have changed over time—shifting from amassing genera to an ethnobotanical and ecological focus—so has the way public gardens think about what it means to serve as a collecting place for people. As important third spaces, gardens must be easily accessible and inviting to diverse groups. Today, gardens must not only highlight their plant collections, but also create

programs, from arts-related programming to community-minded events, that allow visitors to simply enjoy being together while engaging with horticulture. Affordable memberships and low-cost governmentsponsored admissions programs permit many more people to frequent gardens and transform them into true third places. The recently formed IDEA Center for Public Gardens (focused on advancing inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility) is helping the industry understand what it means to truly make gardens places for all people. Welcoming diverse communities is not a passive endeavor, but one that takes intentionality and shared purpose.

At its core, this work is joyful. Gardens thrive when they cultivate their collections of people with the same care and intention with which they cultivate their collections of plants. In doing so, gardens can gain so much more than just new visitors. What makes a garden delightful is not only seeing beautiful plants, but seeing other people enjoy them— watching a child’s wonder as they learn that the grapefruit they had for breakfast grew on a tree, seeing an elderly couple hold hands as they walk through the garden where they went on their long-ago first date, or witnessing memories being made by families whose children will one day bring their own children and tell the stories of how meaningful this “third place” has been to them.

6

Education

Why gardens are important places beyond their plants.

Hannah and Rae Vassar

Amanda Hannah and Rae Vassar are in the Longwood Fellows Program.

Illustration by Morgan Cichewicz

Birds of a Feather

Education 8

By Lynn Schuessler

Of ravens and rusty blackbirds: Longwood is a “hotspot” for birding enthusiasts.

Birders spot a Common Raven flying over the Longwood Meadow. This species has been found in southern Chester County only in the last decade.

9

Photos by Daniel Traub

When Kennett Square native Joe Sebastiani picked up a book on birds at the Wetlands Institute in Stone Harbor, NJ, during a trip to the beach in 1985, the teen simply wanted to expand his collection of field guides. But a family friend invited him to walk those Wetlands to get a real-life look at the birds in that book, and he was hooked—he wanted to see them all.

Thirty-five years later, he’s seen almost all the birds in his Peterson’s field guide. It has been his personal passion and his life work to collect sightings of birds throughout the mid-Atlantic, as well as in places like Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Trinidad.

“It’s meaningful to see a bird I’ve never seen before and add it to my life list. But a big part of it is watching and admiring a bird in its habitat.” For Sebastiani, one of the most important habitats is the one you can create in your own backyard.

As Director of Adult Engagement at Delaware Nature Society, Sebastiani assists volunteers with citizen science projects like Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s NestWatch, and leads nature programs like “Discovering Winter Resident Birds,” a walk he led last November through Longwood’s Meadow Garden in collaboration with our Continuing Education division.

During an online orientation, Sebastiani set the scene. We’ve lost three billion birds in the last 50 years—one in four North American birds—to threats like habitat loss, insect decline, house cats, and collisions with building glass —all compounded by climate change. “We have a responsibility to the birds,” Joe says, “because human activity impacts them.”

The good news is that conservation efforts since 1970 have increased populations of raptors (hawks, eagles, ospreys) and waterfowl. Now we need to expand those efforts to the highly impacted species we love to catch sight of, including Eastern Meadowlarks, Baltimore Orioles, and Barn Swallows.

“One thing you can do,” says Sebastiani, “is create bird food through native plantings.” Not only do native trees, shrubs, and grasses provide fruit, seed, and cover, they are year-round “insect factories” for birds and their young. “Birds like it messy,” Sebastiani says, describing how he turned a hard-to-mow slope from lawn (aka “bird desert”) to meadow. “Build it and they will come.”

And come they did, on November 16, 2022—birds and birders alike—to Longwood’s Meadow Garden, a wonderfully messy paradise of tall grasses

10

“We have a responsibility to the birds,” Joe says, “because human activity impacts them.”

Mary Hubner of Maryland enjoys a morning walk and a variety of birds in Longwood’s 86-acre Meadow Garden.

Joe Sebastiani of Delaware Nature Society listens to the flight call of a Cedar Waxwing.

and wildflowers gone to seed. In a public garden known more for its floral displays and fountains, the birds did not disappoint.

Participant Marla Edwards, an avid feeder watcher, enjoyed observing the relationship between birds and plants in a natural habitat. “The Cedar Waxwings were in their element and extraordinarily beautiful,” she says.

Mary Hubner loved the Waxwings, too, but admits to being a “big bird” fan. Both she and her sister, Nancy Close, were delighted to spot a variety of hawks, Bald Eagles, and even a Common Raven, which is somewhat of a novelty, having recently expanded its range to our area from the Appalachians. The size of a Red-tailed Hawk, the Raven is the world’s largest songbird, boasting a “deep primeval croak,” explains Sebastiani.

Other highlights included a rare Rusty Blackbird, which feeds at the edge of wetlands and whose population has declined 90% in the past 50 years; and Fox Sparrows, which Sebastiani tracked with calls as they rustled through leaf litter. Edwards also enjoyed checking out some nests, a clue to birds that are breeding in the area … “And they’re works of art!” she says.

For the morning’s total, Sebastiani submitted a count of 306 birds from 35 species to eBird, a database maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that tracks bird populations worldwide. Longwood has two eBird “hotspots” for which guests can submit bird counts: one in the general Gardens, and one specific to the Meadow; there is also a third nonpublic birding hotspot at Longwood’s Abbondi property.

Although Edwards still records significant sightings in the margins of her original Peterson bird book, she recently began using the Merlin app powered by eBird, which provides easy access to resources in the field—range maps, photos, and sound ID. Hubner, too, has used the Merlin app, to learn bird calls that help with identification.

“Ebird makes you an instant scientist,” says Sebastiani, “and makes it easy to keep track of your lists.” And yet, he gently plays down the science, especially with new birders. “I try to be contagious with excitement,” he says. “It’s an opportunity to make an impression about a wonderful pastime that can become lifelong.”

Sebastiani feels that birdwatching is more about being out in the beauty of nature … about relaxation … about doing something that’s actually good for

you. It’s about the “spark” bird that is so beautiful you have to learn more. It’s about seeing that single Rusty Blackbird and wondering what you can do to help, because it’s disappearing.

Sebastiani’s advice is to start from where you are. Step outside, see what’s in front of you … then let your interest grow. Add a pair of binoculars you can afford, a bird book, an app, maybe a camera. Try some native plantings.

Hubner hopes to plant some Eastern redcedars to invite those coveted Waxwings, along with some owls, closer to home … and she’d like to start drawing the birds that she’s photographed. Edwards hopes to get rid of some invasives in the mini meadow nearby, so the native plants and birds can thrive. Close, a photographer, would love to spot a Baltimore Oriole, look for Bald Eagles at Conowingo, and, well … she has her eye on that Kowa fixed 30 power scope that Sebastiani was carrying.

They all agree they’ll be back for more—perhaps for “the spring collection” of birds at Longwood. They’re hooked. They’ll want to see them all.

11

The group observes a pair of Eastern Bluebirds feeding in the Meadow.

Nancy Close, who has taken several photography classes at Longwood, captures a shot alongside her sister Mary Hubner.

Meadow Garden Bird Count

November 16, 2022

35 species, 306 individuals

QTY SPECIES

American Robin

Dark-eyed Junco

Canada Goose

American Goldfinch, Song Sparrow, Cedar Waxwing

White-throated Sparrow, Common Grackle

Turkey Vulture

Eastern Bluebird

Carolina Wren, House Finch

Northern Cardinal

Black Vulture, Bald Eagle, Northern Flicker, Carolina

Chickadee, European Starling, Fox Sparrow

Red-tailed Hawk, Tufted Titmouse, Field Sparrow

Sharp-shinned Hawk, Red-shouldered Hawk, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Hairy Woodpecker, Blue Jay, American Crow, Common Raven, White-breasted Nuthatch, Northern Mockingbird, Purple Finch, White-crowned Sparrow, Swamp Sparrow, Rusty Blackbird

60 40 30 25 15 10 8 6 4 3 2 1

Above: Eastern Bluebirds typically inspect nest boxes in the middle of winter, sometimes sleeping in them at night.

12

Top: A strategy to find birds in a tall-vegetation meadow is to look down the path where they frequently feed on the ground.

Longwood Gardens

eBird Hotspots

Data as of December 12, 2022

Outdoor Gardens

210 species observed 2,836 complete checklists

Meadow Garden

160 species observed 1,558 complete checklists

Right: White-throated Sparrow is a common winter resident of meadows, thickets, and even residential areas.

Below: Standing meadow vegetation left uncut for the winter is a paradise for many species of sparrows and other small wintering birds.

13

Features

The first seven bonsai gifted from The Kennett Collection take center stage upon their arrival at Longwood in October 2022.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

The first seven bonsai gifted from The Kennett Collection take center stage upon their arrival at Longwood in October 2022.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

A generous gift to the Pierre S. and Alice du Pont

Founder’s Circle begins the next chapter of our storied bonsai collection.

By Jourdan Cole

LIVING SCULPTURE

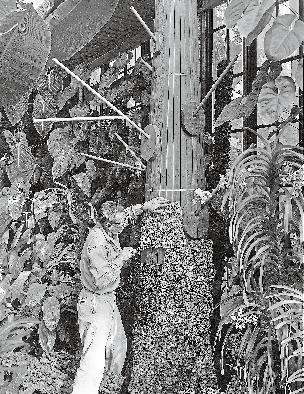

Below: More than 70 bonsai call Longwood Gardens home. When not on display, they spend their time in Longwood’s production greenhouse where Kevin Bielicki, bonsai curator, tends to them behind the scenes. Photo by Daniel Traub.

chinensis ‘Shimpaku’)

16

Horticulture

Opposite: A Chinese juniper (Juniperus

in the slant style, gifted from The Kennett Collection. Photo by Daniel Traub.

A rare example of Japanese white pine in the root over rock style, this specimen was originally trained in Japan by world-famous bonsai artist Masahiko Kimura, known as “The Magician.” During its journey to the United States it suffered damage that took years to repair. Marco

18

Left: Japanese White Pine Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’.

Invernizzi, Mr. Kimura’s first foreign apprentice, carefully restored the tree’s character and beauty, adding a new chapter to its storied legacy.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Above: Doug Paul, owner and founder of The Kennett Collection, continues to acquire and nurture awardwinning bonsai since purchasing his first in 1999.

Photo by Freshfly.

At Longwood, our collections are always growing and evolving … as are the stories we proudly tell about them. From the first bulbs that emerge to announce spring’s arrival to the 1,300-plus types of plants we grow in our production greenhouse—our work, and the beauty of Longwood, is amplified through the growth of people, plants, and spaces. And, once again, growth is at the heart of the most recent addition to our collections—a gift of 50 bonsai from The Kennett Collection, the finest and largest private collection of bonsai and bonsai-related objects outside of Asia. This incredible gift not only increases our bonsai collection’s diversity of species, variety of styles, and representation of works from bonsai masters around the world … it also transforms the way in which we can share the beauty of bonsai—and the story of this astounding artform—with so many.

Bonsai have a multi-faceted story— they wear their histories, preservation, and inspiration on their leaves. In order to create a masterpiece bonsai tree, countless hours of work and effort must be put in, often over several generations.

“Bonsai is created to be a thoughtful conversation between the art of the grower and the life of a tree,” says Kevin Bielicki, Longwood’s bonsai curator. “The new world-class specimens we’re adding are going to create a different sense of awe and inspiration for our guests.”

For many, viewing our bonsai is a usual facet of their visit to Longwood. Some marvel at the age of our oldest specimens, while others enjoy the unique design or find joy in a regular-sized pomegranate growing on a miniaturized tree. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder—anyone can appreciate the beauty that comes in their miniature forms, while a more trained eye looks at roots, trunks, branches, and leaves to see a story of intense training unfolding.

The practice of miniaturizing plants spans centuries—originating in China several hundreds of years before the Japanese began mastering the art sometime around the seventh century. Known as penjing in China, or “potted scenery,” this initial artform didn’t idealize nature, but instead aimed to capture the wild beauty of nature in tiny form. Around the 12th century, Japanese artisans had evolved the

art into the controlled form known today as bonsai, or “potted planting.”

Emphasizing this idealization of nature concept, many bonsai are trained to evoke the movement of blowing in the breeze, turning to the sun, or living in the elements of nature. To do so, a bonsai artist must understand each tree’s personality and characteristics—accentuating those traits.

“We use many of the traditional principles and elements of design—line, form, texture, and rhythm,” says Bielicki. “But what makes bonsai really unique is that bonsai is one of the few artforms that is really about time. It’s a responsive artform. It’s a give and take. We prune the tree, we see how it responds. We’re always working in response to the tree.”

For centuries, the art of bonsai and the secrets of its form remained in Japan. It wasn’t until the 1950s, after American military were stationed in Japan during WWII, that the artform began captivating Americans. In 1959, five years after Longwood founder Pierre S. du Pont’s death, bonsai would find its way to Longwood via renowned bonsai artist Yuji Yoshimura, who also crafted one of the first

Right: Tokyo-born bonsai master Yuji Yoshimura (1921–1997) was in residence at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden on a fellowship when he was invited to speak at Longwood on February 17, 1959, at the suggestion of Advisory Committee member Julia Bissell. His lecture was so well received that he was then asked to teach a five-week bonsai course from May 18 to June 22. Enrollment was 77, divided into eight daytime sessions and three evening sessions of seven students each (including seven Longwood employees), ensuring individual attention from the instructor. Reaction was so positive that Longwood decided to start its own bonsai collection and purchased 13 specimens from Yoshimura, who spent the rest of his life popularizing bonsai in this country. Photo by Gottlieb Hampfler.

19

bonsai books in English, revealing the intricacies of the practice to the western world. During his initial visit to the US, he was invited to speak at Brooklyn Botanic Gardens and then Longwood Gardens. Yoshimura performed a demo during that first trip and demand was clear—11 sections, each with seven students, quickly filled up. Thirty others had to be turned away. And that’s when it was decided Longwood would begin building a bonsai collection.

Longwood purchased 13 trees from Yoshimura that were shipped from Japan to Hoboken, NJ, before arriving at Longwood. Of those original 13 bonsai, four remain today—Japanese zelkova, ginkgo, crapemyrtle, and Chinese elm.

Since 1959, our bonsai collection has been managed by only six curators and its location has moved to accommodate and highlight the growing collection. Prior to the gift from The Kennett Collection, our collection included 78 trees with 50 species represented, notable for the prominence of flora from the local landscape.

Many bonsai collectors from near and far have visited our collection throughout the years; however, fate would have it that one of the most notable private bonsai collections was located nearby in Kennett Square. The Kennett Collection, which was started in 1999 by Doug Paul, now comprises 1,200 specimens that span the spectrum of bonsai in terms of sizes, styles, and species.

Bielicki also got his start at The Kennett Collection, working there in both full-time and part-time capacities for the past 18 years. There, he learned from the world’s leading bonsai experts who have tended the

collection and got a first-hand view of what makes a standout bonsai. Several of The Kennett Collection’s bonsai have been invited for display in the Kokufu Bonsai Exhibition and there are a number of trees that are “Registered Masterpiece Bonsai” by the Nippon Bonsai Association.

In 2018, around the time Bielicki began at Longwood, the Longwood bonsai collection also began displaying new specimen bonsai on loan from The Kennett Collection that included two to five bonsai rotating on a monthly basis. Now, we’re preparing for one of the most transformative gifts to our collections, of which we’ve already welcomed—and proudly displayed—a portion, sharing their beauty, and their stories, with our guests.

This generous gift from Doug Paul and The Kennett Collection is one of the first Longwood has received as part of the Gardens’ Pierre S. and Alice du Pont Founder’s Circle, which recognizes and honors individuals who make the thoughtful decision to include Longwood Gardens as part of their estate plans.

Received in two parts, the initial gift will include 50 bonsai given to Longwood over the course of the next two years, as well as a yearly stipend to support their care and maintenance. The second part of the gift is a bequest, which will gift 100 additional specimens—including kicho bonsai or Important Bonsai Masterpieces because of their beauty or rarity—and $1 million for an endowment for the continued care and expansion of the collection. The bequest will more than double the size of Longwood’s collection. Most significantly, it will add important

examples of rare Japanese tree species, making our collection the leading collection of bonsai trained in Japan on public view in the United States.

“I have spent many happy years stewarding these bonsai and sharing them with other bonsai connoisseurs,” said The Kennett Collection Founder and donor Doug Paul. “I look forward to a wider public getting to enjoy their beauty and splendor at Longwood.”

The first seven bonsai received as part of this gift were on display in our East Conservatory this past October, and they’ll return to display this spring. The majority of the 50 bonsai from the initial gift will go on long-term view in the new Bonsai Courtyard, being constructed as part of Longwood Reimagined, a transformation of 17 acres of the Gardens’ central visitor area. As part of this expansion, the new outdoor Bonsai Courtyard will be built alongside the new West Conservatory. Hedges and charred wood walls will create an intimate, gallery-like space, where dozens of bonsai will be displayed on free-standing pedestals against dark backdrops that highlight their forms, foliage, and seasonal bloom.

Until then, we are honored to be the recipient—and the steward—of such an amazing gift … and we are delighted to continue sharing the beauty—and the evolving stories—of these spectacular bonsai and our growing, storied collection.

To learn more about the Pierre S. and Alice du Pont Founder’s Circle, or to share your intentions, please contact:

Melissa Canoni / Director of Development

Top row, left to right: Satsuki hybrid azalea (Rhododendron ‘Kinsai’) in the informal upright style. Within the Japanese bonsai world, Satsuki azaleas inhabit a unique niche, and growers and enthusiasts specialize in their development, display and appreciation. Their natural growth habit is normally a shrubby clump but with care and the correct technique they can be developed into thick trunk specimens such as this.

Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii ‘Kotobuki’) in the slant style. Developed by the Chinsho-en nursery in Takamatsu, Japan. It is a very distinctive variety that has naturally short needles, a compact growth habit and flaky bark that develops down to the branch tips.

Center row, left to right: A variety of sizes of annealed copper wire used for wrapping around branches to hold them in place when they are moved into new positions. Each size is used with a different size branch.

Bonsai master Marco Invernizzi works with a Chinese juniper (Juniperus chinensis ‘Shimpaku’) at The Kennett Collection. Invernizzi, the first non-Japanese person to study under bonsai master Masahiko Kimura, regularly tends to The Kennett Collection. The tools of the trade for bonsai masters at The Kennett Collection.

Bottow row, left to right: Detail view of Marco Invernizzi pruning the Chinese juniper.

Trident maple ( Acer buergerianum) in the root over rock style. This specimen was developed by the Boston-based bonsai artist Suthin Sukosolvisit, who is considered by many as the best non-Japanese trained artist in the western world.

Photos shot on location at The Kennett Collection by Hank Davis.

20

mcanoni@longwoodgardens.org / 610.388.5216

21

22

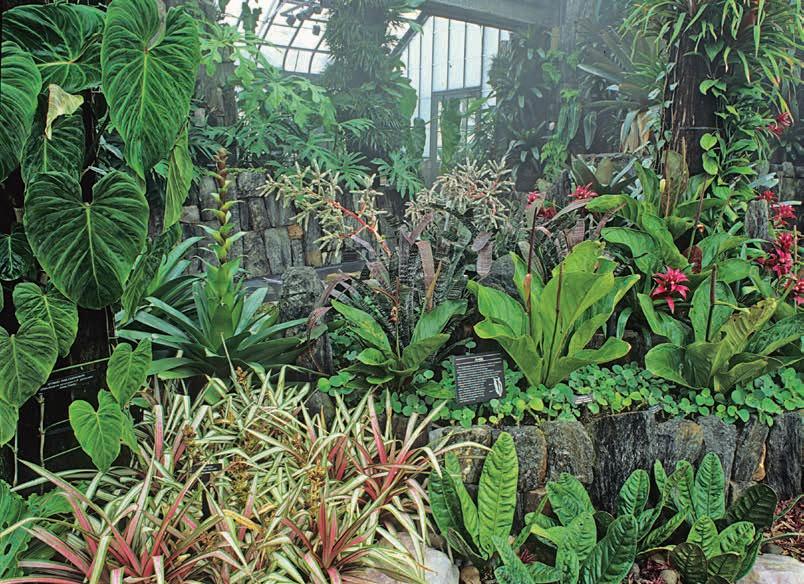

A group of renowned landscape designers have left their talented, visionary, remarkable mark on Longwood in the form of a collection of significant, storied spaces.

Of GARDENS and DESIGNERS

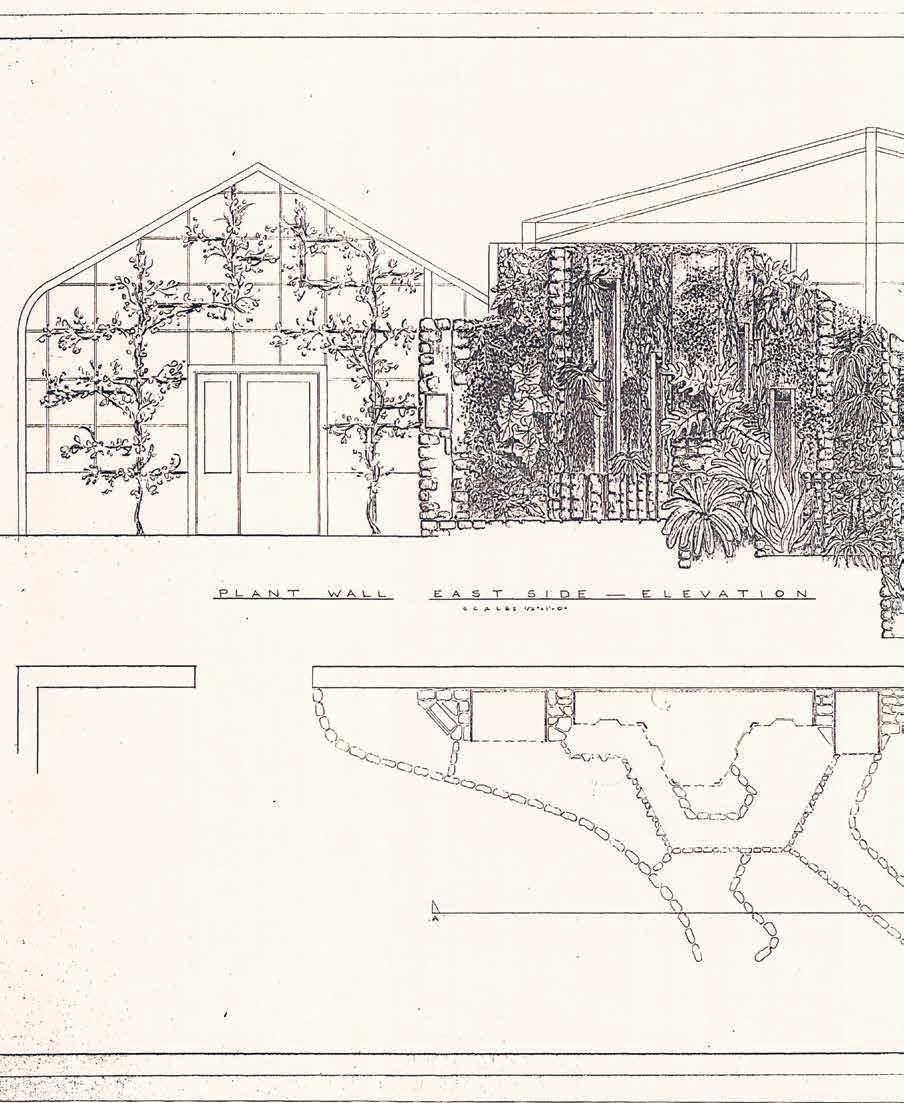

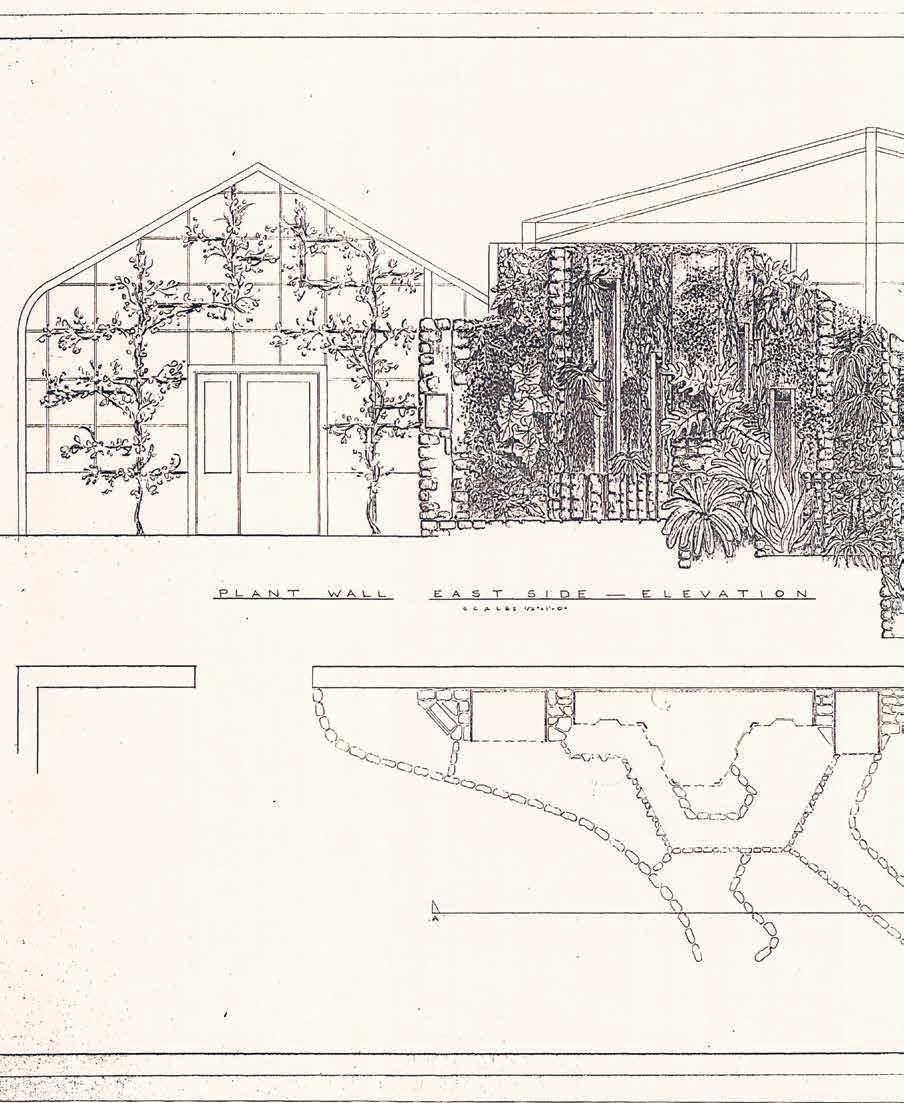

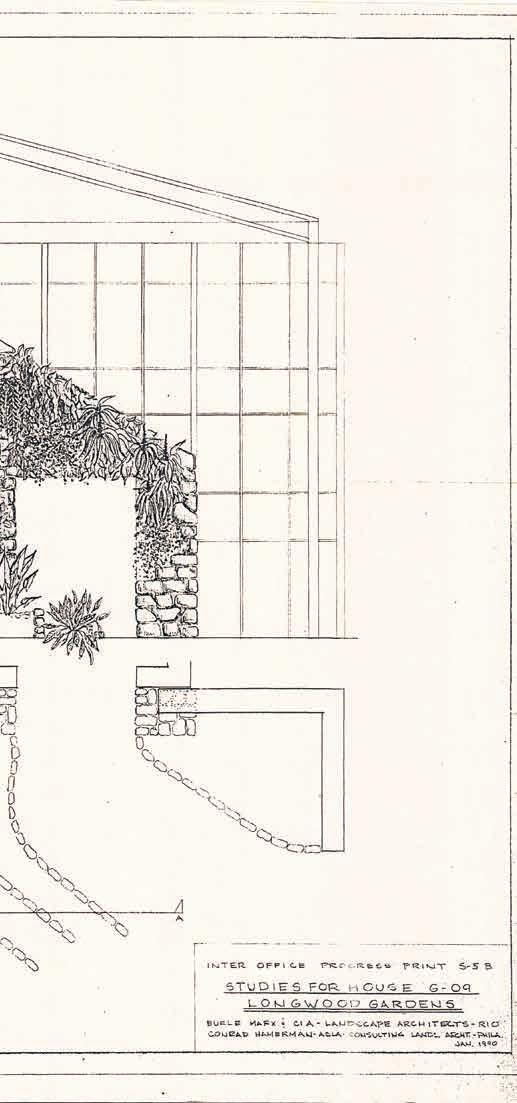

Preliminary east side elevation and plan views by Roberto Burle Marx and Conrad Hamerman, part of their design studies for glass house G-09 (the Cascade Garden). Longwood Gardens Library & Archives.

23

The Arts

Waterlily Display

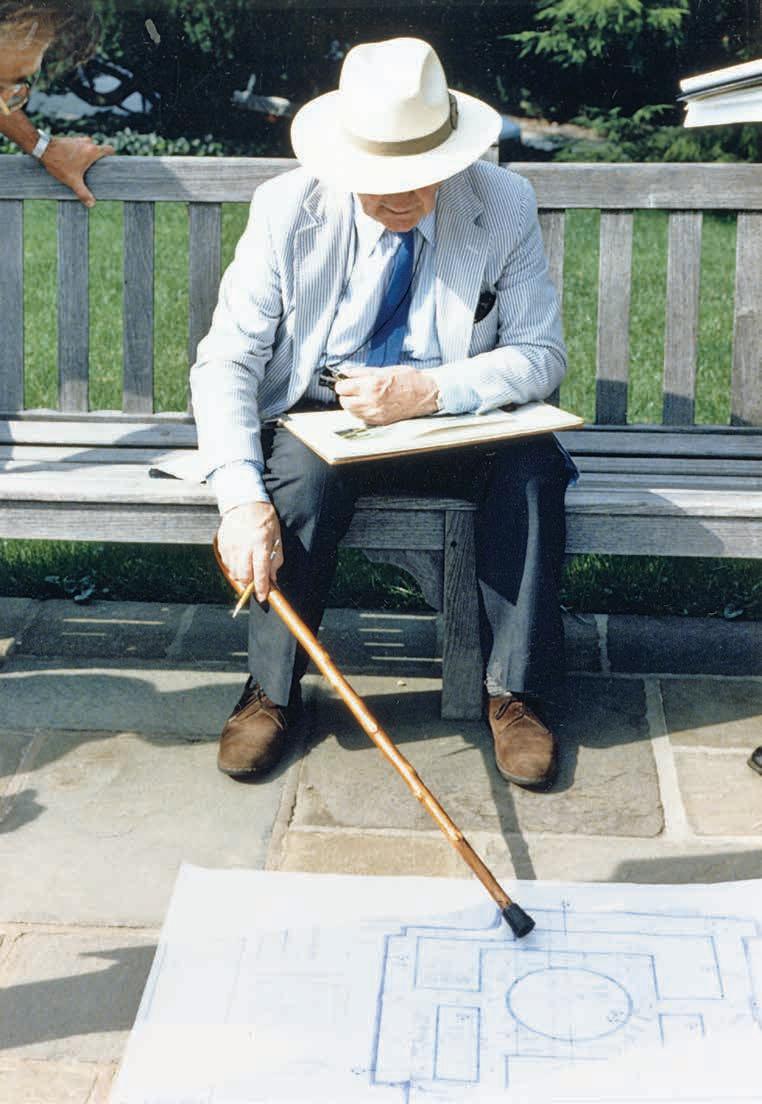

Sir Peter Shepheard

Tropical aquatics came to Longwood in 1957 with the opening of a 13-pool Waterlily Display. In 1989 the display was redesigned by renowned landscape architect Sir Peter Shepheard (opposite)—known for emphasizing the relationship between the landscape and man-made structures—into five larger, dramatic pools that showcase more than 100 types of day- and nightflowering waterlilies, our iconic Victoria

water-platters, and other aquatic plants. As part of Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience, this beloved garden will reopen as a renewed, enhanced Waterlily Court building upon its Shepheard design. The Waterlily Court will be redefined as an outdoor room and further strengthened as a central destination, while serving as a gateway to the new West Conservatory and relocated Cascade Garden.

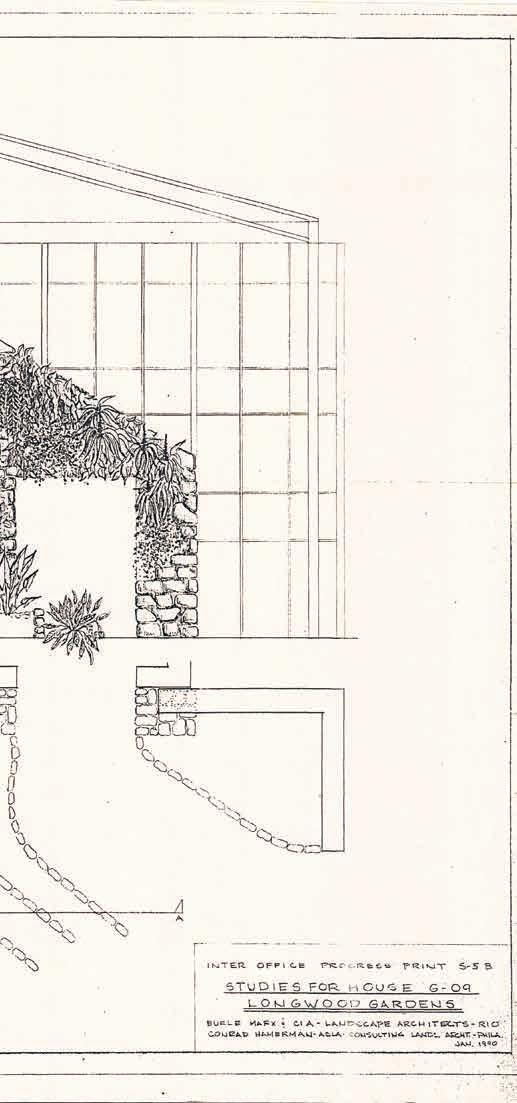

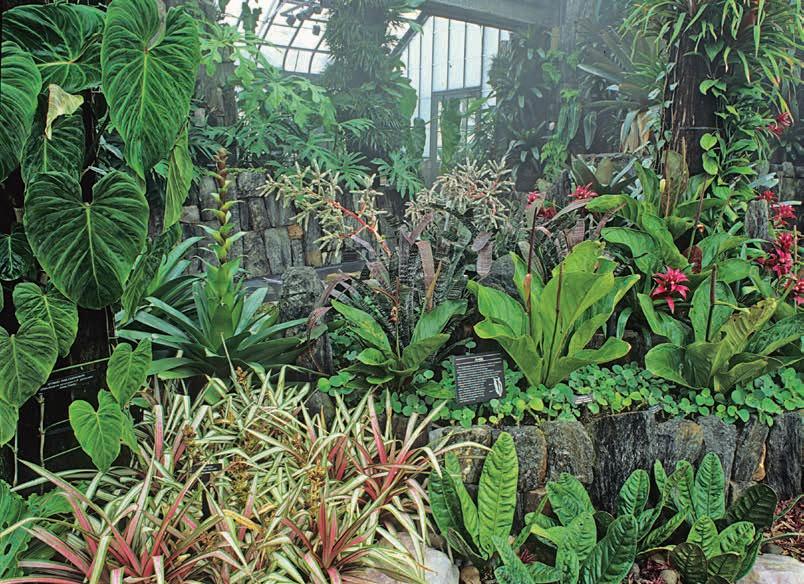

Cascade Garden

Roberto Burle Marx

Known for his signature style of using organic shapes combined with bold, sweeping geometric outlines, Roberto Burle Marx is widely regarded as the progenitor of the modern garden and one of the preeminent landscape architects of the 20th century. Working with landscape architect Conrad Hamerman, Burle Marx created the Cascade Garden especially for Longwood, opening in 1993. Today it serves as the only remaining garden of his design in North America. Named for its 16 waterfalls, the Cascade Garden enchants with its flowing

plantings and abundance, with Burle Marx’s focus on vertical design captured beautifully. This historic garden will be moved in its entirety into a new, custombuilt glasshouse that will give the plants more room to flourish, reopening with Longwood Reimagined. A historic garden has never been moved as a whole and preserved in this way, and we are honored to work with a team of scholars, landscape architects, preservation experts, and the Burle Marx Landscape Design Studio to realize this achievement.

24

Photo by Larry Albee

25

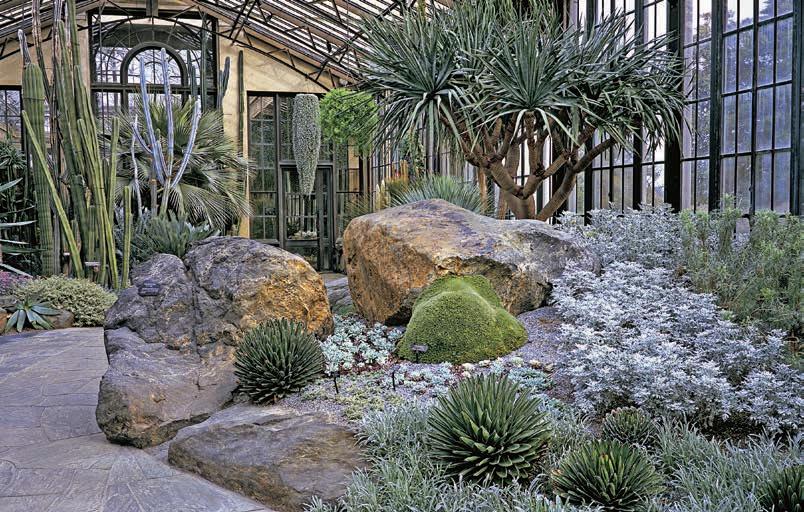

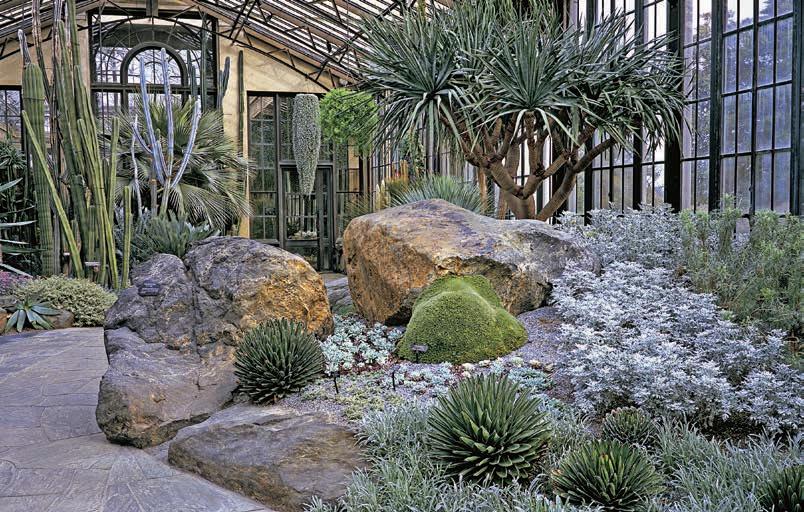

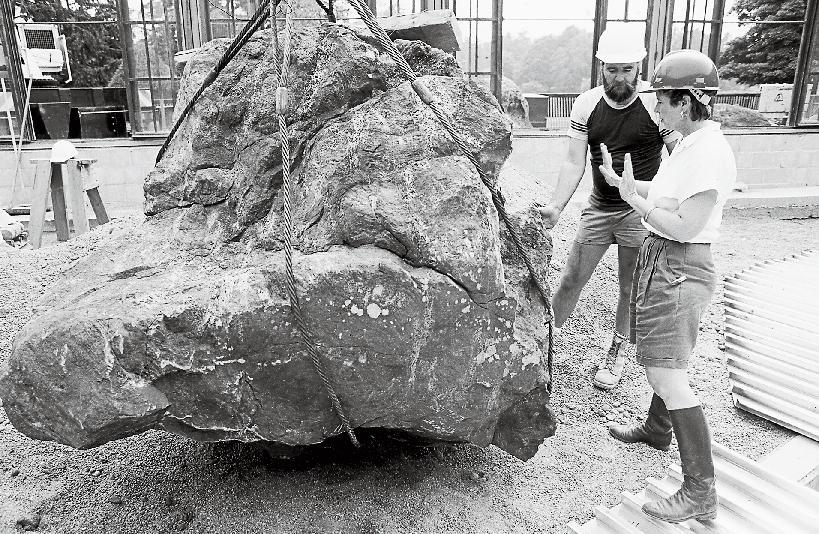

Silver Garden

Isabelle Greene

contemporary design, which conveys a realistic

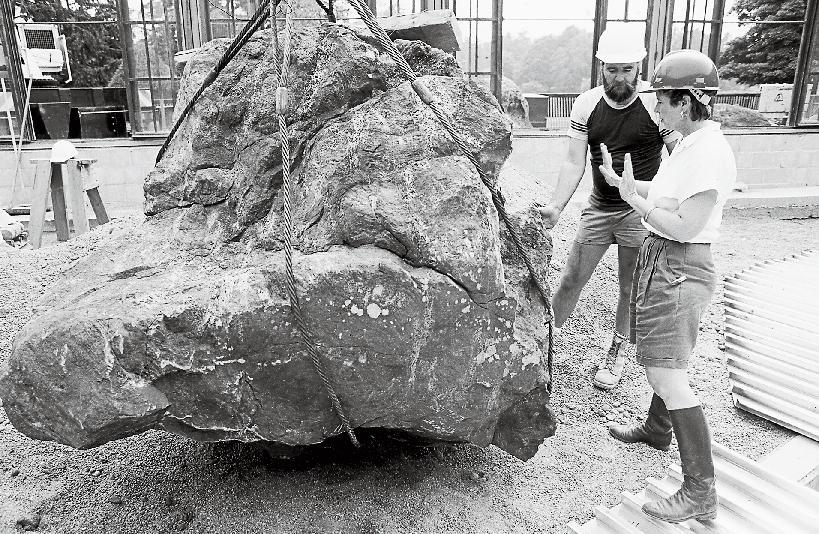

Right: Rock work consultant Keir Davidson (left) with Silver Garden Landscape Designer Isabelle Greene, during the installation of the garden’s distinctive large boulders.

Right: Rock work consultant Keir Davidson (left) with Silver Garden Landscape Designer Isabelle Greene, during the installation of the garden’s distinctive large boulders.

26

Photos by Larry Albee

California-based landscape architect Isabelle Greene created the Silver Garden, a modernist display of plants native to Mediterranean and desert climates—a palette for which she is best known. Opening in 1989, the Silver Garden’s

desert landscape experience, marked a groundbreaking moment for Longwood, as well as a visual departure from the more formal approach seen throughout the Conservatory.

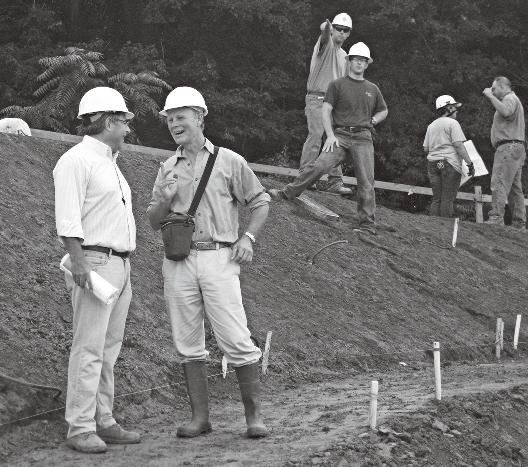

In 2014, Longwood debuted the present Meadow Garden, a gorgeous example of ecological design by landscape architect Jonathan Alderson—and a striking departure from the formal gardens from which we were known at that time. Not only is the Meadow Garden incredibly beautiful with its tapestry of texture and ever-changing color, it serves as a layered, complex physical representation of our commitment to the health and stewardship of the Brandywine Valley—and ecosystems beyond. By stewarding this land and its carefully managed wetlands, ponds, open fields, and forest’s edge, this 86-acre garden of designed natural landscapes provides a place to practice— and better—ecological science as a whole.

27

Photo by Daniel Traub

Meadow Garden

Jonathan Alderson Landscape Architects

28

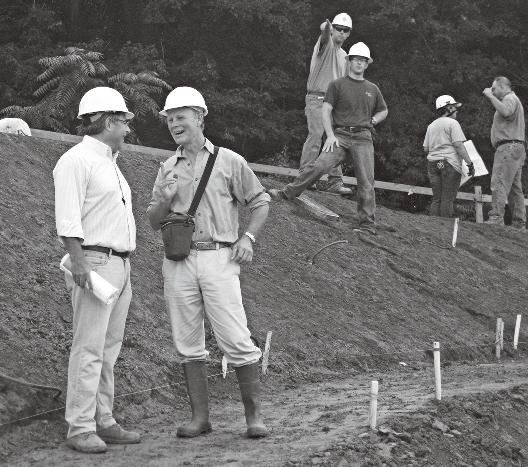

Below: Landscape architects Stuart Appel (1954–2012) and Kim Wilkie chat during construction of the East Conservatory Plaza. Photo by Sharon Loving.

Photo by Duane Erdmann

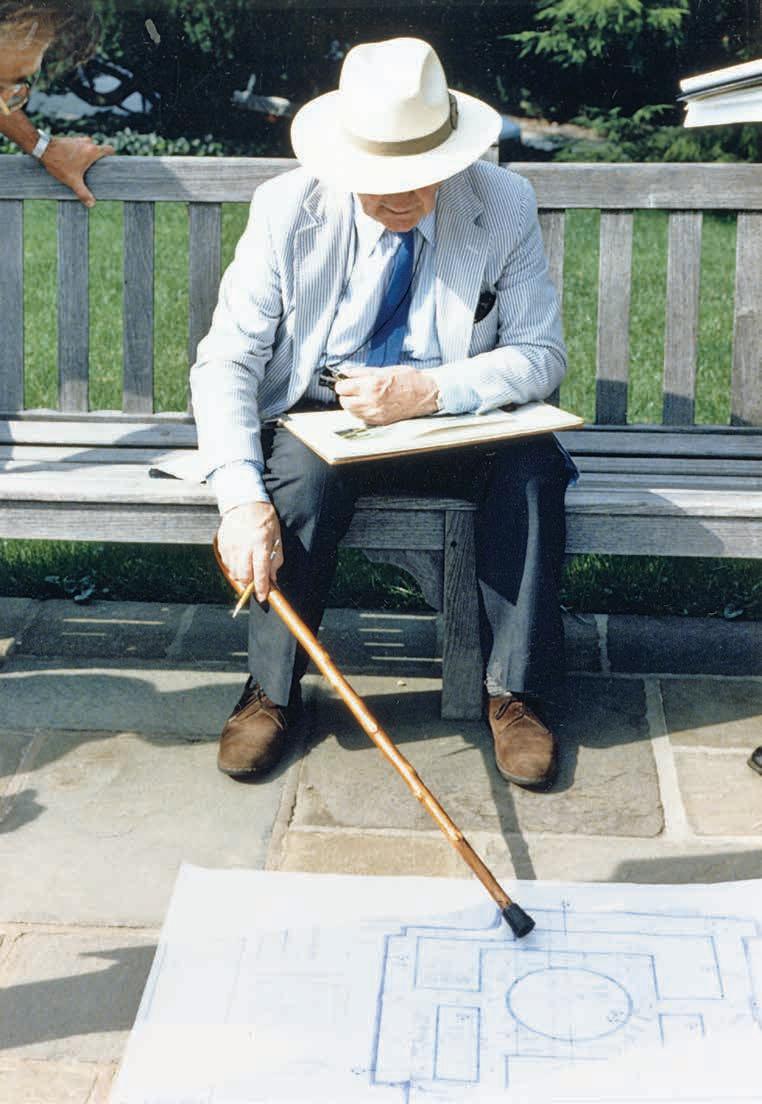

East Conservatory Plaza and Green Wall

Kim Wilkie

Opened in 2010, Longwood’s East Conservatory Plaza is home to the first terraced lawn in the United States designed by UK-based landscape architect Kim Wilkie, as well as Longwood’s one and only landform. Composed of five tiers of sculptural, grass-covered terraces—spanning 13,800 square feet—that emerge like steps, the space is a stunning visual experience, melding Wilkie’s modern design into the existing landscape with a curated collection of trees and shrubs.

In conjunction with the design and construction of the East Conservatory Plaza and landform, Wilkie designed the lush Green Wall, nestled just inside the East Conservatory and also opening in 2010. A 4,000-square-foot haven of vertical vegetation—with each and every plant numbered and assembled like a puzzle—the Green Wall and its complex habitat of woodlandsetting plants flourishes in this light-filled, glorious display of innovation.

29

Photo by Fred Zwiebel

30

Photo by Daniel Traub

Peirce’s Woods W. Gary Smith

Designed by W. Gary Smith, Peirce’s Woods focuses solely on native plants. Soaring oaks, ashes, maples, and tulip-trees look over this award-winning garden spanning 200 species and cultivars of small trees, shrubs, and large horizonal sweeps of groundcovers, boasting seasonal interest from spring through fall.

31

Photo by W. Gary Smith

Longwood Reimagined: A New Garden Experience

Weiss/Manfredi Architecture/Landscape/Urbanism

Reed Hilderbrand Landscape Architects

32

Photo by Daniel Traub

Blending the historic and the visionary, Longwood Reimagined is the largest expansion, reimagination, and preservation of our Conservatory and surrounding landscape in Longwood’s modern history. Defining a great garden of the world in the 21st century requires a design team of great minds, including Weiss/ Manfredi Architects and Reed Hilderbrand Landscape Architects. The centerpiece of

Longwood Reimagined is the 32,000-squarefoot West Conservatory with its curved steel reminiscent of tree branches and distinctive roofline that will house a garden resplendent with Mediterranean plantings. Preserving and enhancing our cherished spaces—many of which have been designed by world-renowned landscape architects—is core to showcasing the beauty of our collections and to the future of Longwood.

33

Public Enjoyment

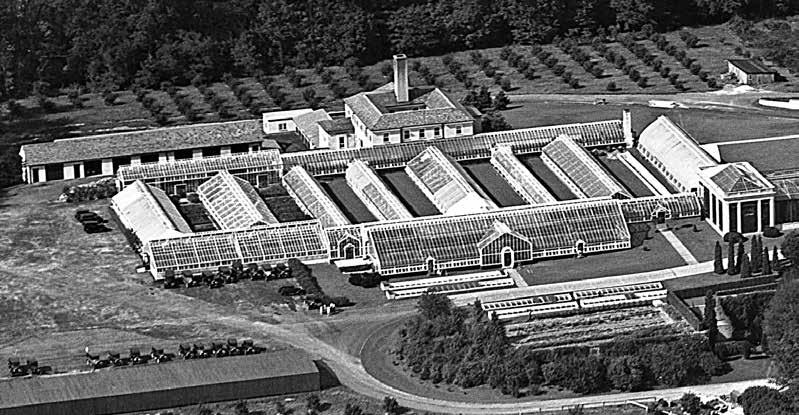

Pierre du Pont passed away on April 5, 1954. With his usual foresight, he had in place a well-funded yet adaptable mechanism for Longwood to continue. Five very experienced businessmen (his nephews) were already the trustees of the Longwood Foundation, and they soon started searching for a professional director. Dr. George Beadle, Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technology and the 1955 president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, suggested they consider Dr. Russell J. Seibert. Seibert was experienced in plants, farming, horticulture, agriculture, plant economics, government, and public garden administration. He was born on a farm in Belleville, Illinois, in 1914. After a youth spent plowing his father’s fields, he vowed “there must be a better way to make a living than looking at a horse's rear end all day.” Seibert received a bachelor’s degree in geology and a master of science and Ph.D. in botany from Washington University, St.

Louis, Missouri. He collected plants during the summers of 1935, 1937, and 1938 in Panama for the Missouri Botanical Garden, and he performed rubber plant surveys and established rubber plant stations in Central and South America as an agent for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) from 1940 to 1949. After a short stint as a geneticist with the USDA in Beltsville, Maryland, he became the director of the Los Angeles State and County Arboretum in 1950.

On July 20, 1955, Russell Seibert (1914–2004) began as Longwood’s first director (1955–1979). The charge from the Board of Trustees was to “transform a private estate into an internationally recognized horticultural display.” Within three months, Seibert had outlined a future for Longwood that continues to this day. As he noted to the Trustees: “In this age of mechanical, chemical, electronic and atomic miracles, we need not fear a decline

in the powers of Nature. Rather, a feeling of closeness to Nature through Horticulture and Gardening shall be one of the potent stabilizers of our civilization. The veracity of this statement is fully evidenced by the fact that home gardening is the ‘No.1’ hobby of the American public today. Through Longwood Gardens and its program of outstanding horticultural display, every visitor to the Gardens has the opportunity to gain, culturally and spiritually, a better peace of mind.”

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw tremendous change at Longwood, comparable to the building program of the 1920s except the emphasis was now on public comfort and education. Russell Seibert immediately proposed a course of action that has been followed in spirit, if not almost to the letter, to the present.

Three months after assuming the directorship, he offered numerous innovative ideas, including major thoughts

34

A Century of Floral Sun Parlors: Part Seven

The late 1950s and early 1960s saw tremendous change at Longwood; the emphasis was now on public comfort and education.

By Colvin Randall

“Through Longwood Gardens and its program of outstanding horticultural display, every visitor to the Gardens has the opportunity to gain, culturally and spiritually, a better peace of mind.”

—Russell J. Seibert, 1955

35

Russell Seibert (left) and Everitt Miller, 1960.

Electric-eye counters clicked loudly when guests walked through the turnstiles; kids (including the author) would sometimes up the count by

waving fingers to break the light beams. The building’s function was largely supplanted in 1962 by the present Visitor Center.

on the Conservatory. The indoors needed less espaliered fruit but new and expanded collections of orchids, plant curiosities, foliage plants, bromeliads, insectivorous plants, tropicals, and medicinal plants, with plants appropriately labeled. Also, a better visitor route through the Conservatory on crowded days would improve circulation.

In 1956, Everitt Miller (1918–2002) was hired to understudy John Marx, Mr. du Pont’s chief horticulturist who would retire in 1959. Miller was born in Brooklyn and educated at the New York State Institute of Applied Agriculture (today SUNY Farmingdale). He spent two years in the Army and was stationed in Italy during World War II. Before coming to Longwood, he worked for a commercial landscape concern then for 10 years as superintendent of the W. R. Coe estate, “Planting Fields,” in Oyster Bay on Long Island, New York. He was enthusiastic

Above: The Melon House in 1956 was fascinating to visitors, but Dr. Seibert thought that too many houses were devoted to food crops.

36

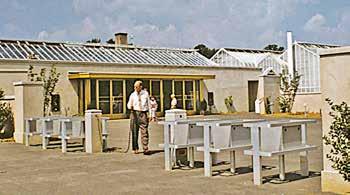

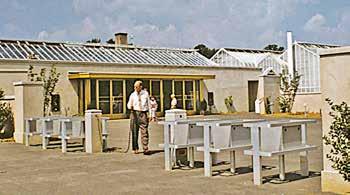

Above: The original Information Center (to the left as one walked in from the Conservatory parking lot) offered basic amenities.

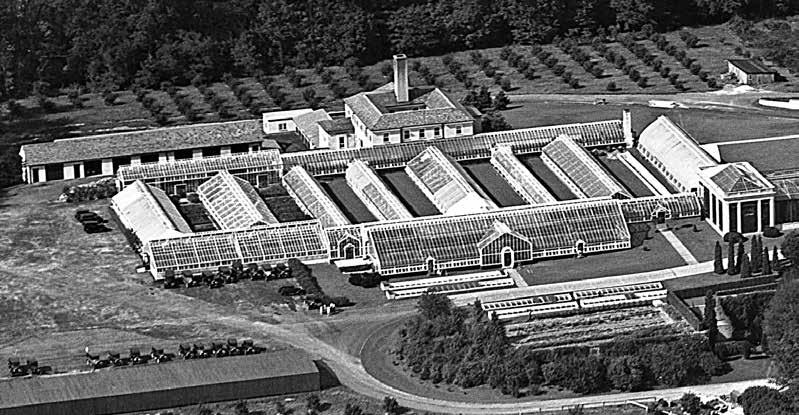

The Growing Houses west of the Banana/Orchid House (1) in 1931. A small greenhouse (2) connected to the Fern Passage on the north side of the Rose House (3), and another

2 3 4 1

small extension (4) held cacti, but this area was not designed to handle large numbers of visitors, plus there were steps from the ferns down into the Rose House.

about the florist industry and judged many flower shows in New York and New Jersey. Miller became the most influential staff player at Longwood other than Seibert and would eventually succeed him as director from 1979 to 1984.

The existing Departments of Horticulture (under Marx), Maintenance (buildings and utilities, under Russell Brewer), and Business (accounting and personnel, under Mr. du Pont’s former secretary George Thompson, Sr.) were augmented by a new Department of Education led by Dr. Walter Hodge, who, like Seibert, had worked in Latin America (and who had recommended Seibert for the Los Angeles job). Together, the staff carried Seibert’s vision forward with major improvements to the Gardens’ public display facilities, to visitor services and education, and to the science of horticulture as practiced at Longwood.

In 1956, the first Information Center, designed by E. William Martin, Pierre’s

favorite architect, opened at the west end of the Conservatory adjoining the original visitor parking area. The Center was small but offered simple publications, guide maps and brochures, personnel to answer questions, guided tours, and restrooms.

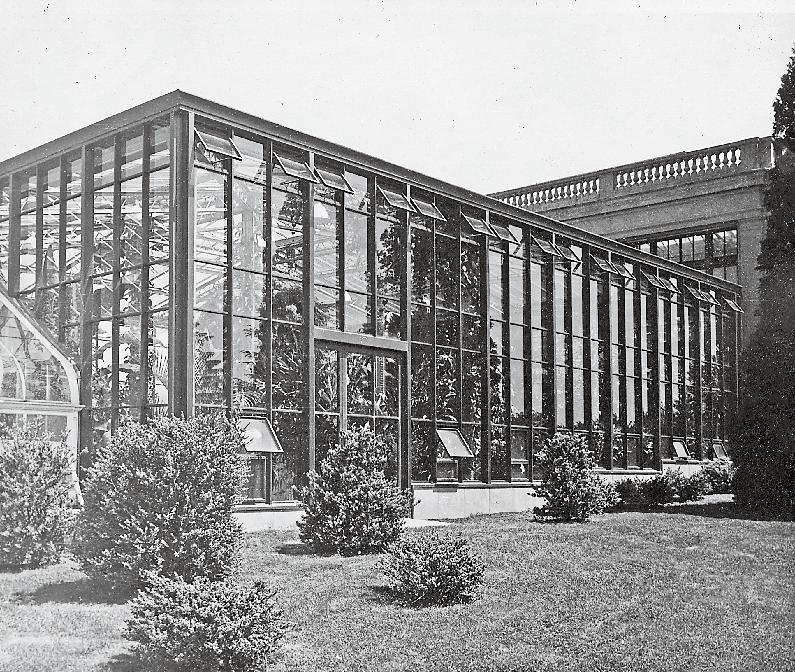

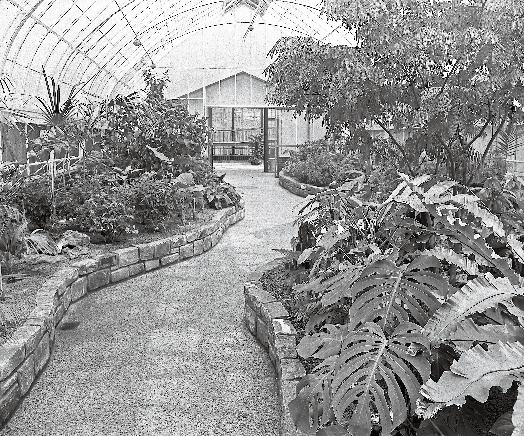

In the Conservatory, the visitor circulation problem was addressed by connecting the multi-level Fern Passage/Rose House to a new Desert House in 1957 and Tropical Terrace in 1958, allowing a smooth, one-way pedestrian traffic loop. Both were designed by the architectural firm of Victorine and Samuel Homsey, Inc. The choice of Homsey was no doubt due to family connections, but the firm was well respected. Victorine du Pont Homsey (1900–1998) was the greatgreat-granddaughter of E.I. du Pont, so she was Pierre’s second cousin once removed. She married Samuel Homsey (1904–1994) in 1929, and in 1935 they founded one of the first husband-and-wife architectural practices in the country. Their notable local buildings

include the residence at Mt. Cuba Center, the Delaware Art Museum, and Winterthur’s Visitor Pavilion. The Homseys and their son Eldon (1936–2020) worked with Longwood for decades, initially by preparing a preliminary master plan, and Eldon served on Longwood’s Advisory Committee from 1986 to 2000.

Russ Seibert was a tropical botanist, so it is not surprising that he wanted to expand Longwood’s minimal tropical collections, which were largely limited to the orchid houses and banana display, per Pierre du Pont’s preference. In 1929, Pierre wrote to the Washington, DC, Park & Planning Commission, then considering a conservatory (presumably the US Botanic Garden conservatory built in 1933), “No finer addition could be made to the points of interest in the National Capital…. I hope that the Commission will work out a large conception…to be devoted to plants and

(continued on page 40)

37

The Exhibition Hall, circa the late 1940s.

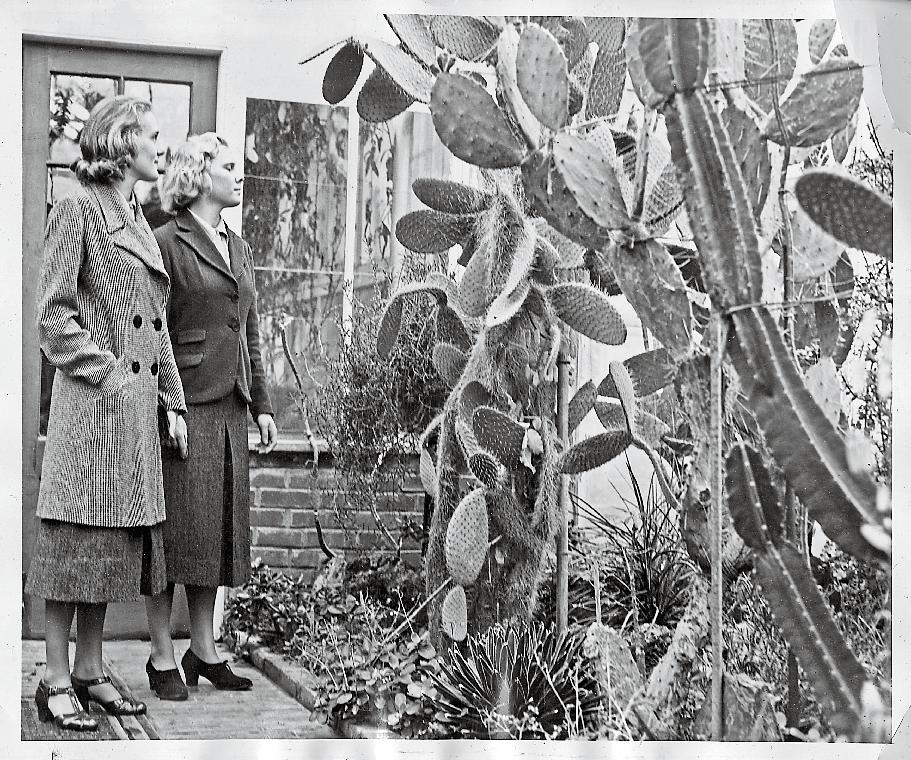

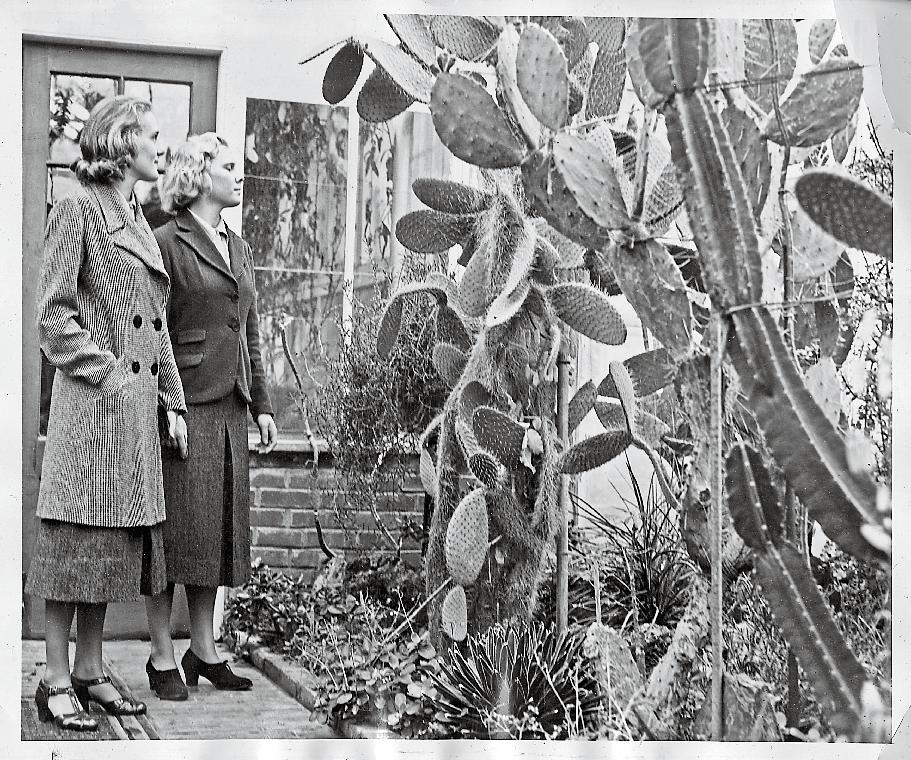

Below: There was a succulent collection in the small greenhouse west of the Fern Passage (in the background), shown here in April 1938 for a syndicated newspaper article.

Above: The new Desert House planting had matured when photographed in 1962. It reopened as the Cascade Garden in 1992.

Below: The sloping path in the Desert House, here in 1959, was an ingenious way to connect to the lowest level of the Rose House without steps.

Below: The Desert House in 1960. Specimens included desert plants of the Western Hemisphere (especially Mexico), Asia, Africa, and Madagascar, including agaves, night-blooming cereus, Easter/Christmas/orchid cacti,

prickly-pears, giant saguaros, ponytail-palm, spurges, kalanchoes, jade-plants, aloes, and senecios. It was noted that such a collection would never appear as densely planted or in such variety in a native arid setting.

38

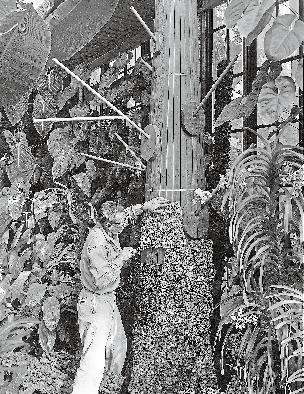

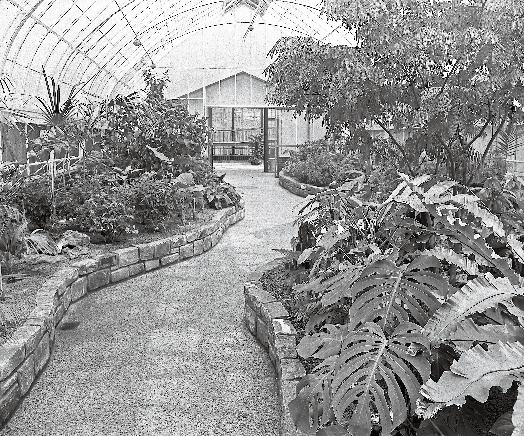

This 1959 photo of the Tropical Terrace shows the ascending path curving around a small pool (right) fed by a rocky stream that ran under the path. The upper level displayed anthuriums, monsteras, and philodendrons. The lower level had plantings of pelican-flower, royal

jasmine, stephanotis, passion-flowers, and waxplants. A ‘Giant Cavendish’ banana (shown in center) was a major curiosity when in fruit, along with the celebrated rabbit’s-foot fern hanging across the path (shown upper right); this fern still grows in today’s Camellia House.

The Tropical Terrace connected the Rose House to the Banana/Orchid House, with an inclined path to return the visitor to the normal walkway elevation. Photo

Above: An artificial tree “growing” around a structural column in the Tropical Terrace displayed epiphytic plants such as Spanish-moss, bromeliads, orchids, and ferns, shown here in 1959.

39

taken in 1958.

The “tree” was reconstructed (left) by gardener Horace Smith in 1965.

Above: Longwood’s educational classes were launched in 1956. This children’s art class, taught by Betty Collins, ran once a week from January 31 to March 13, 1957. The first session, shown here, was held in the service area behind the Ballroom—today the Organ Museum. Subsequent art classes, including for adults, were moved to the Meetinghouse.

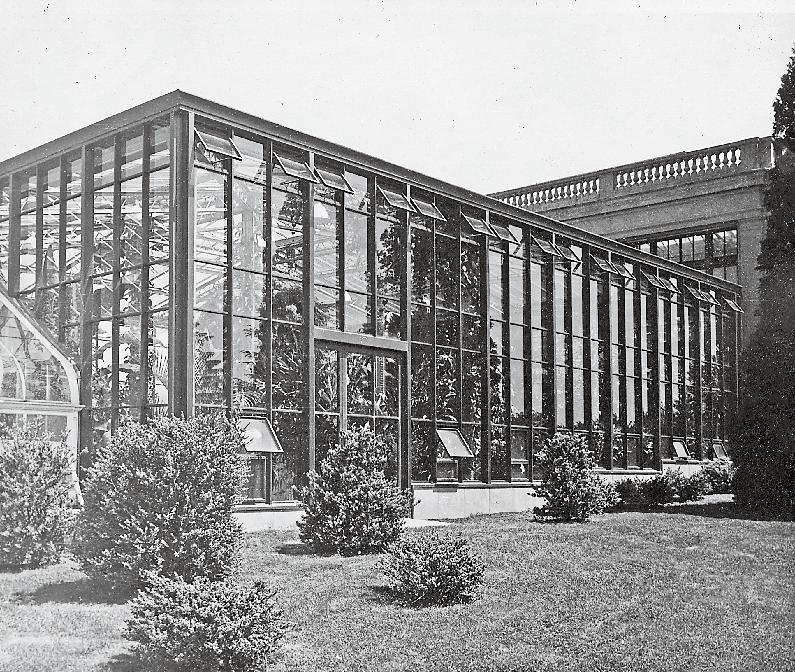

labs was designed by the Homsey firm. It opened in 1958 just behind the Conservatory, in which a smaller, older greenhouse had been previously used for experimental purposes.

Above: The site of the Palm House in June 1964. Notice the picturesque stepped gable at the end of the North Passage.

Left: In 1957, an Experimental Greenhouse complex with four glasshouses, a headhouse, and office

Above: The site of the Palm House in June 1964. Notice the picturesque stepped gable at the end of the North Passage.

Left: In 1957, an Experimental Greenhouse complex with four glasshouses, a headhouse, and office

40

Below: Planting the Palm House in September 1965.

Above: Gardener Pat Nutt watering the newly planted Palm House, April 1966. The house was 60 × 60 × 55 feet tall (from

House (in the distance) and planted with tropicals, which eventually included fancy-leaved begonias, Javanese rhododendrons, tropical pitcher plants, epiphytic and terrestrial

bromeliads, and spectacular columnea hanging baskets. Plantings evolved to include gesneriads and economic plants. It reopened in 1993 as the Mediterranean Garden.

Below, left to right: The Number 9 greenhouse in 1955 sheltered azaleas and rhododendrons, just like it had since 1920. The same view in April 1966 shows it connected to the new Palm

Below, left to right: The Number 9 greenhouse in 1955 sheltered azaleas and rhododendrons, just like it had since 1920. The same view in April 1966 shows it connected to the new Palm

41

outside ground level).

flowers of temperate climate. These are more interesting in their beauty and in the fact that the lower temperature is more satisfactory for visitors and reduces the coal bill tremendously. It would require very little fuel in Washington to maintain such a building.” Dr. Seibert obviously did not agree!

Both the Tropical Terrace and the Geographic House expanded upon the tropical flora (bananas, papayas, vanilla) growing in the Banana House (today’s enlarged Orchid Display). The Banana House was renamed the Economic House, where a coffee tree, papyrus, plantain and Manila-hemp bananas, pepper, vanilla, passion fruit, and steroid-rich Mexican yams were cultivated to show sources of food, fiber, and medicine.

Although outside, the Waterlily Display that opened in 1957 is an integral part of the Conservatory experience. Russell Seibert had seen at firsthand the beauty of tropical aquatics. It didn’t hurt that his father-in-law was George Pring (1885–1974), renowned waterlily and orchid expert and former

superintendent of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Pring helped Russell Brewer (who engineered Longwood’s fountains) design the 13-pool display. The Missouri Botanic Garden supplied the plants, and Pring mentored gardener Patrick Nutt (1930–2015), who went on in 1960 to hybridize Longwood’s giant water-platters. The aquatic collection initially featured 40 to 50 species and varieties of waterlilies and some 30 other aquatic plants such as water-chestnut, water-hyacinth, waterlettuce, papyrus, and lotus.

Facilities to grow everything needed for a prime horticultural display were lacking, so in 1956 a plant Nursery and in 1958 a new, expanded Experimental Greenhouse were established. A plant breeding program was initiated in 1960 under the direction of Dr. Richard Lighty. Additional production greenhouses were built in 1963.

Dr. Donald Huttleston was hired as taxonomist in late 1955 with the daunting task of identifying, recording, and labeling thousands of plants. A dual

Above: The Peach/Nectarine House adjoining the Acacia Passage was transformed into the tropical Geographic House in 1958.

Above: Entering from the Economic House, the visitor first encountered plants from Australia, Asia, and the Pacific islands. The center area was planted with Western Hemisphere cacao, sapodilla, and rubber plants. At the far end nearest the

42

Orangery were African coffee, mahogany, and the Madagascar traveler’s-tree. There was a gentle, raised “bump” in the path shown in the foreground, which added a subtle sensation as one walked over it. Today this is the Silver Garden.

system of labels for both public and staff use was devised. The response to a few trial lectures and classes in 1956 was so encouraging that an evening lecture series and short courses for the public were developed, followed by world-class training programs. Thousands of amateur enthusiasts and professional horticulturists have attended over the succeeding decades.

Palms were the most important group of tropical plants missing from Longwood’s indoor displays up to the 1960s. Palm houses were traditional in European botanical gardens, but not at Longwood. Drs. Seibert, Hodge, and Huttleston had assembled since 1956 a collection of about 100 species of palms, but there was no central place to display them. Finally, on Palm Sunday, 1966, the spacious Palm House opened with a landscape of 60 palms of all sizes and shapes best seen from an elevated walkway around the interior perimeter. The Palm House was designed by the Homseys and was the last new public “footprint” added to the Conservatory; all subsequent display greenhouses have

reused or replaced earlier structures.

Besides the horticultural arts, the performing arts had a place in the new scheme. Clarence Snyder became organist upon the retirement of Firmin Swinnen in 1956. The massive pipe organ in the Ballroom was rebuilt from 1957 to 1959 with a spectacular new console. Public organ concerts and evening musicales were regularly scheduled; the complete story is told in a new book, Garden of Music.

By the mid-1960s, Longwood had been transformed from a magnificent private estate into an outstanding public garden, thanks to the vision of Russell Seibert, a dedicated staff, and forward-looking Trustees. But the transformation was far from complete.

Above: Constructing the waterlily pools, 1956–1957

Right: A mermaid curious about the new waterlily display miraculously appeared in 1957.

Above: Constructing the waterlily pools, 1956–1957

Right: A mermaid curious about the new waterlily display miraculously appeared in 1957.

43

Opposite: Dr. Seibert with 18-year-old Crown Prince Constantine of Greece, March 1, 1959. Constantine was on an extended tour of the US, touring military bases and industrial plants, and visited Longwood with officials from the Department of Defense. (From 1964 to 1973, he reigned as King of Greece until the monarchy was abolished.) Three months later, King Baudouin of Belgium (on the throne 1951–1993) was entertained at a Ballroom banquet on May 31, 1959, for 140 guests, followed by a special fountain display.

A Century of Floral Sun Parlors: Part Eight will appear in the next issue of Longwood Chimes

All Aboard

What began as a relatively modest display of two trains (one diesel, one steam) traversing 150 feet of track in the fall of 2000, has become an intricate, beloved tradition among guests and staff alike. Today, our G-scale Garden Railway chugs along on four separate tracks totaling 500 linear feet. G-scale, or Garden Scale, is one of the largest scales in model railroading. It is known for its durability and for being well-suited to outdoor conditions. With a collection that grows each year and now boasts 212 engines, boxcars, passenger cars, tank cars, and more, our six engineers have plenty of options when it comes to assembling trains to hit the rails.

Over the years, the train display has expanded from the original Paul Busse design featuring a few notable Longwood and regional landmarks to now include trellises and bridges created by our metal shop, boxcars modified inhouse with sound boards to provide that quintessential “train sound” when the engine might not be equipped to, and picturesque landscaping courtesy of our Horticulture Department and track designs for the trains to travel through.

“Each year we try to bring new elements for guests to enjoy,” explains Guest Engagement

Lead Mark Kosteski, who for the last seven years has been part of the team of engineers, horticulture, and facilities staff who bring the railway to life each year. Kosteski shared that some recent additions to the collection include a school bus Eggliner engine and a Bachmann Denver and Rio Grande Steam engine with matching passenger cars and cattle cars that was “a big hit” with guests. New this year is a Longwood-branded engine featuring our iconic rosette mark on the complementary caboose.

Kosteski had no previous model train experience and has learned a lot in the past seven years through hands-on work and from experienced colleagues and enthusiasts about how to construct the railway, how to best operate it, and how to properly maintain the railway. “At Longwood,” Kosteski explains, “we strive to keep the trains running, and of course, on time!”

By Patricia Evans

End Notes

Now in its 23rd year, our Garden Railway keeps chugging along.

44

Young guests enjoy watching the Garden Railway travel through a stunning landscape complete with Longwood landmarks. The Garden Railway is on view September through the holiday season and boasts more than 200 engines, boxcars, tanks, and more.

“There is nothing more satisfying to see than the pure joy and excitement the trains bring to the children that visit each year.”

Guest Engagement Lead Mark Kosteski is a member of the talented team of engineers, horticulture, and facilities staff that keeps the trains running on time.

—Guest Engagement

Lead Mark Kosteski

45

Photos by Daniel Traub

No. 306

Winter 2023

Front Cover

Birds of a Feather:

Led by Joe Sebastiani (far right) of Delaware Nature Society, birdwatchers “flock together” in Longwood’s Meadow Garden, which has become a birding “hotspot.” Birders come to connect with nature, perhaps adding a fortuitous sighting to a life list, to a collection of photographs, in the margins of a guidebook … or to the treasury of moments best kept in hearts and minds. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Back Cover

Tracking down a historic collection of images:

In 2014, Performing Arts

Programming Associate

Director Emily Moody gave P.S. du Pont Fellow Colvin Randall a best-selling book, The Astronaut Wives Club, which a friend had given her. Colvin was immediately intrigued, because astronaut

Alan Shepard’s wife Louise was the daughter of Phil Brewer, Longwood’s master electrician who largely designed the Garden’s historic fountains. This led to further research that put Colvin in touch with Brewer’s granddaughters Laura and Julie, living in Colorado and Texas respectively. They loaned Longwood assorted documents and hundreds of priceless, historic slides from Brewer’s collection in 2017, from which Colvin scanned 318 for the Longwood Digital Archive in 2018. A selection of 35mm slide transparencies are shown here. Photo by Daniel Traub.

Inside Front and Back Covers

A sampling of vintage Longwood brass plant ID tags:

According to Plant Records Manager Kristina Aguilar, the labels have always been made of brass. Variations in the ratio of copper to zinc are the primary cause of variations in color and shade. The oldest labels were hand-embossed on long spools of brass, then cut to size based on the length of the plant name. The corners were snipped to reduce sharpness, then a riveted hole was placed at center left so they could be hung from a plant via a wire. The newer labels are a standard size and embossed using an automatic embosser.

The information on the accession tag is as follows:

The first line displays the accession number. Older labels show a 2-digit year followed directly by the order in which the plant was accessioned. Newer labels show a 4-digit year, a hyphen, then the order of accession.

The sequence of the remaining data has changed over time, but in most cases contains the plant’s scientific name, scientific family name, common name (in double quotes), and native range or nativity of a species.

Editorial Board

Jourdan Cole

Nick D’Addezio

Patricia Evans

Steve Fenton

Julie Landgrebe

Sarah Masterton

Katie Mobley

Colvin Randall

James S. Sutton

Kristina Wilson

Contributors This Issue

Longwood Staff and Volunteer Contributors

Kristina Aguilar

Plant Records Manager

Morgan Cichewicz

Sr. Graphic Designer

Hank Davis

Volunteer Photographer

David Ward

Volunteer Photographer

Other Contributors

Amanda Hannah

Longwood Fellow

Lynn Schuessler

Copyeditor

Daniel Traub

Photographer

Rae Vassar

Longwood Fellow

Distribution

Longwood Chimes is mailed to Longwood Gardens Staff, Pensioners, Volunteers, Gardens Preferred and Premium Level Members, and Innovators and is available electronically to all Longwood Gardens Members via longwoodgardens.org.

Longwood Chimes is produced twice annually by and for Longwood Gardens, Inc.

Contact

As we went to print, every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of all information contained within this publication. Contact us at chimes@longwoodgardens.org.

© 2023 Longwood Gardens. All rights reserved.

46 Longwood Chimes

Photo by David Ward.

Longwood Gardens is the living legacy of Pierre S. du Pont bringing joy and inspiration to everyone through the beauty of nature, conservation, and learning.

Longwood Gardens

P.O. Box 501 Kennett Square, PA 19348

longwoodgardens.org

“A collection starts as a protest against the passage of time and ends as a celebration of it.”

—Questlove

A small sampling of engines, boxcars, tankers, and cabooses from the Garden Railway G-scale collection.

Photo by David Ward.

A small sampling of engines, boxcars, tankers, and cabooses from the Garden Railway G-scale collection.

Photo by David Ward.

The first seven bonsai gifted from The Kennett Collection take center stage upon their arrival at Longwood in October 2022.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

The first seven bonsai gifted from The Kennett Collection take center stage upon their arrival at Longwood in October 2022.

Photo by Daniel Traub.

Right: Rock work consultant Keir Davidson (left) with Silver Garden Landscape Designer Isabelle Greene, during the installation of the garden’s distinctive large boulders.

Right: Rock work consultant Keir Davidson (left) with Silver Garden Landscape Designer Isabelle Greene, during the installation of the garden’s distinctive large boulders.

Above: The site of the Palm House in June 1964. Notice the picturesque stepped gable at the end of the North Passage.

Left: In 1957, an Experimental Greenhouse complex with four glasshouses, a headhouse, and office

Above: The site of the Palm House in June 1964. Notice the picturesque stepped gable at the end of the North Passage.

Left: In 1957, an Experimental Greenhouse complex with four glasshouses, a headhouse, and office

Below, left to right: The Number 9 greenhouse in 1955 sheltered azaleas and rhododendrons, just like it had since 1920. The same view in April 1966 shows it connected to the new Palm

Below, left to right: The Number 9 greenhouse in 1955 sheltered azaleas and rhododendrons, just like it had since 1920. The same view in April 1966 shows it connected to the new Palm

Above: Constructing the waterlily pools, 1956–1957

Right: A mermaid curious about the new waterlily display miraculously appeared in 1957.

Above: Constructing the waterlily pools, 1956–1957

Right: A mermaid curious about the new waterlily display miraculously appeared in 1957.