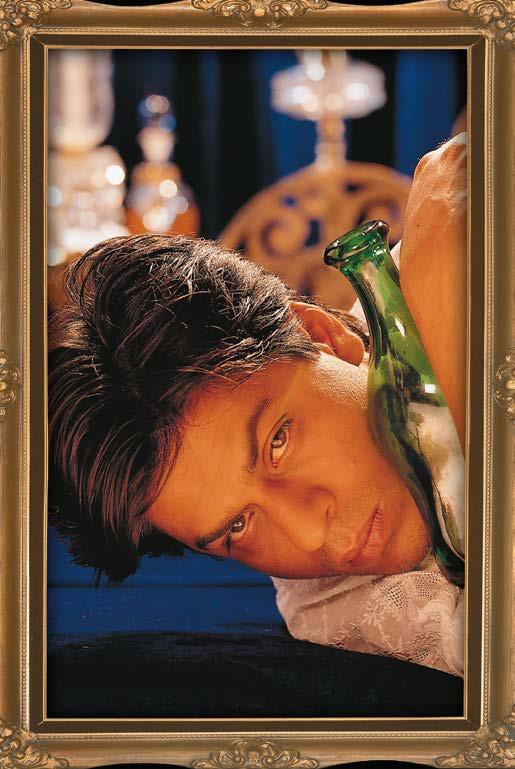

SHAH RUKH KHAN

King Among Men

King Khan Comes to Town

The Zürcher Brothers Speak on DER SPATZ IM KAMIN

Locarno Goes Green: Sustainability at the Festival

King Khan Comes to Town

The Zürcher Brothers Speak on DER SPATZ IM KAMIN

Locarno Goes Green: Sustainability at the Festival

A. Nazzaro ARTISTIC DIRECTOR

Il Locarno Film Festival è da sempre un osservatorio privilegiato per intercettare i movimenti del cinema italiano. Il più grande festival italofono del mondo, dopo ovviamente la Mostra d’arte cinematografica di Venezia, sin dalle sue origini ha intrecciato con il cinema italiano un rapporto profondo e fecondo. La retrospettiva locarnese dedicata a Totò, per esempio, inaugura la straordinaria stagione della riscoperta del lavoro dell’attore italiano, e restando a Napoli, è sempre a Locarno che si scopre Massimo Troisi e il compianto Salvatore Piscicelli. Non solo. La riscoperta di Mario Camerini parte da Locarno, e l’imponente lavoro dedicato alla Titanus è ancora oggi un modello di riferimento. Ma è soprattutto sul

nuovo cinema italiano che il festival si è impegnato e schierato. Basti pensare a Marco Tullio Giordana, la cui carriera –sin da Maledetti vi amerò (1980) – ha attraversato la storia di Locarno. Presentando a Giordana uno speciale Pardo alla carriera in occasione della prima mondiale del suo nuovo film, La vita accanto, scritto in collaborazione con Marco Bellocchio, intendiamo celebrare quanto di meglio il cinema italiano offre oggi e festeggiare una lunga amicizia che siamo sicuri proseguirà anche in futuro.

Buon cinema, e ci vediamo in Piazza Grande.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Christopher Small

LEAD EDITOR: Leonardo Goi

DEPUTY EDITORS: Hugo Emmerzael, Maria Giovanna Vagenas, Keva York

STAFF WRITERS: Laurine Chiarini, Savina Petkova

CONTRIBUTORS: Giovanni Marchini Camia, Cyril Cordoba, Stefan Ivančić, Sadia Khatri, Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer

TRANSLATORS: Tessa Cattaneo, Anna Rusconi

BRAND, EDITORIAL & MEDIA: Oliver Osborne

DESIGN: Joshua Althaus, Nadine Curanz, Alex Furgiuele

PHOTOGRAPHERS: Elia Bianchi, Julie Mucchiut, Ti-Press,

PARTNERSHIPS: Marco Cantergiani, Laura Heggemann, Nicolò Martire, Fabienne Merlet CROSSWORD DESIGNER: Nicholas Henriquez

English, Italian

RETROSPETTIVA

11:30 GranRex THE KILLER THAT STALKED NEW YORK by Earl McEvoy 76’ | o.v. English

21:30 GranRex

THE BIG HEAT by Fritz Lang 89’ | o.v. English

FUORI CONCORSO 14:30 PalaCinema 1 OPT ILUSTRATE DIN LUMEA IDEALĂ by Radu Jude, Christian Ferencz-Flatz 71’ | o.v. Romanian | s.t. English SLEEP #2 by

GranRex TROIS COULEURS : ROUGE by Krzysztof Kieślowski 99’ | o.v. French | s.t. English HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA LEOPARD CLUB AWARD IRÈNE JACOB

SUSTAINABILITY DAY

Piazza Remo

14:00 Forum @Spazio Cinema TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE EUROPEAN FILM INDUSTRY

“There’s no way you haven’t heard my name!” Shah Rukh Khan’s catchphrase is known to his billions of fans the world over. News that the Bollywood superstar was to receive the Pardo alla Carriera Ascona-Locarno Tourism had social media abuzz: the King was coming to Locarno! But if you’re someone who somehow hasn’t yet heard his name, Pardo has you covered: here’s a primer on his long and illustrious cinematic reign.

by Sadia Khatri

SRK, King Khan, Baadshah of Bollywood – no Indian actor has reset the limits of stardom like Shah Rukh Khan. To call him an ‘actor’ is not enough. In South Asia, the UAE, and parts of the Global South, SRK is a household acronym, a brand and an icon, and, as he himself claims, a god of marketing: his face is seared into an entire region’s memory – who does not know that messy shock of hair, the dimpled smile, the narrow eyes looking up mischievously? Khan is one of the most magnetic actors in India, if not the aspiration and blueprint.

On-screen, Khan is revered for his unparalleled range of romantic heroes. Thirty years into his career, he is the only actor of his generation still being cast opposite the up-and-coming heroines of today. Off-screen, the masses love the myth of the man. In interviews and public appearances, Khan has mastered walking the thin line between presenting himself as an approachable, relatable guy and owning his mega-stardom. One minute he jokes with easy familiarity; the next, he reminds his audience that he is the biggest star of Bollywood – incomparable, and at the end of the day, untouchable. “I’m not scared of being overshadowed by anyone in this world,” he has said. At the box office, it doesn’t even really matter if a given film does well or not – the man remains beloved.

SRK did not start off as a heartthrob. His earliest work cast him as a villain: in both Baazigar (1993) and Darr (1993), he played an antagonist who meets his own death. Khan himself didn’t think he had the looks to make it as a popular romantic lead – but then along came Aditya Chopra, the biggest producer in contemporary Bollywood. When he saw Khan in the ’90s, he told the young actor, “Your eyes have something that cannot be wasted on action [films].” Fans seem to agree: on YouTube and TikTok, there are endless compilation videos of SRK’s eyes. It was Chopra who first cast SRK as a romantic lead, in his directorial debut, Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayeinge (1995) – a now-classic musical about two star-crossed diaspora Indians. The film was an instant hit domestically and overseas too, and launched Khan as the heartthrob. Three decades later, it is the longest-running film in Indian cinemas.

Khan’s virtuosity comes through in the impressive range of romantic roles he’s taken on: he has played many a passionate lover in the vein of his DDLJ character, yes, but also lovers who are frightful stalkers, clumsy oafs, gangsters, and unwitting terrorists; earnest charmers, tragic heroes, heroes with a mission (and a savior complex), and noble citizens driven by a sense of duty to the nation and its people.

The most popular of SRK’s loverboys are the unswerving romantics of films like DDLJ and Dil To Pagal Hai (1997) – the ones destined to be with their beloved, no matter the odds. So what if her parents disapprove of him, or she has a fiancé already? Either by fate’s hand or through our hero’s persistence, love will find a way. The thrill is in discovering the movie miracle of how. Take Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), for instance: the ridiculous plot revolves around a mission to reunite a widower –our hero – with his high school best friend and true love, conducted by his dead wife through a series of letters.

Many of SRK’s films of the 2000s sold a particular kind of moral hero: the dutiful son, the honest worker, the loyal soldier forced to choose between his devotion to his family or country, and his lover. For love, of course, the hero will turn away from family and nation both. In the family saga K3G, or Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham... (2001), SRK plays Rahul Raichand, a doting elder son who is cut off from his millionaire family for marrying beneath his class. In Veer-Zaara (2004), he plays the eponymous Veer, an Indian air force officer who is unjustly imprisoned in Pakistan for 22 years under false allegations of being a spy – a sentence he submits to in order to save Zaara, his Pakistani lover, from a torturous marriage, because her husband-to-be threatens to treat her cruelly if Veer does not plead guilty. By the end of both films, of course, everything has worked itself out. The myth sold by this model of a SRK lover is that the right choice is the one grounded in honor, and that, if the hero just sticks to his moral guns, time will deliver justice and reconciliation – and the girl. The family will reunite; the borders keeping lovers apart will be bridged, and no one is offended: what makes this kind of hero so popular is in part the fact that he rebels when required by his principles, but he does not upend or challenge any social structures in a lasting way.

them to prolong an emotional scene – but there are other mannerisms too: his expressive use of sound, manifest in the abundant “mmms” and “heyys” that build emotional tension in lieu of language, especially in scenes where he’s flirting, teasing, upset, or irritated. Then there are the trademark “moments” or scenes: Khan exiting a train with a backpack slung over his shoulder in DDLJ, or dancing atop a moving train in Dil Se (1998). SRK’s mischievous, comic heroes, meanwhile, tend to be easily startled. They playfully dominate whatever space they’re in by tripping and bumping into things – right up until they ‘accidentally’ (wink, wink) succeed at whatever impossible goal they set out to achieve.

Khan’s appeal ultimately lies in repetition, not invention. It doesn’t matter what the role is, he always delivers those codified characteristics that audiences have come to associate with him and the joy of viewing is precisely in that familiarity; that recognition; that expectation being met. When he smiles with his head nodding, you know he’ll playfully lift a finger; when he ruffles his hair, you know he’s in love; when he throws his shoulder back, you know he’s about to strike his iconic pose, and passionately open his arms towards his beloved.

It’s no accident that so many of his characters have the same names. Dil To Pagal Hai and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai were the first to introduce SRK to viewers as “Rahul”, a name now almost synonymous with the actor. “I am Rahul. There’s no way you haven’t heard my name!” is Khan’s famous introduction in DTPH, memorable for its simultaneous confidence and nonchalance. So, every time SRK says, in yet another movie, “I am Rahul...”, the audience is delighted – we have heard of him before.

But Khan is not content with just imprinting on cinema history – he has said that he wants to stretch the limits of storytelling too. Through Red Chillis Entertainment, the production company he launched with his wife, Gauri, in 2002, Khan has surprised audiences with off-beat, experimental turns in films like My Name is Khan (2010), in which he plays an autistic Muslim in post-9/11 America, and as the titular 3rd century BC emperor in Asoka (2001). His appearance in Dil Se also came out of leftfield: the film is the final entry in Mani Ratnam’s trilogy on terror and communal violence, and mounts a scathing critique of the Indian state’s relationship with the insurgency in the North East. Khan stars as Amarkanth, a radio journalist who falls for a militant, and is subsequently torn between love and country. Nothing compares, however, to the epic tragedy of Devdas (2002), in which all of Khan’s romantic personas coalesce in a single role: Dev is both hero and anti-hero; the perfect lover on a path of self-destruction. The film depicts the unraveling of a man who commits to losing everything with the same intensity that he once committed to love – abandoning his lover Paro, his family, and chasing only the bottle. By the time Dev is reduced to a shell, SRK has given the character every emotion we have previously seen him perform on screen.

In the 2010s, Khan’s career dipped – but last year, he mounted a giant comeback, releasing three blockbuster hits, including the Red Chillis production Jawan (2023), which offers a spicy twist on the anti-heroic hero. In it, the righteous citizen standing up for his people – played by Khan, naturally – happens to be the son of an ex-army officer. The hero is out to expose the rotten system, and to fix it, too –but, unlike Dil Se, which openly pointed a finger at the Indian state, Jawan flattens the complex relationship between history and revolt, and does not lay blame upon any specific power structure beyond a generally “corrupt” system. Khan’s production company seems to be taking on political issues while treading a safe, neutral line.

Across roles, King Khan’s genius emerges in his trademark delivery, gestures, and on-screen habits, which have come to constitute an iconic style. Chopra, the producer, was the first to identify those puppy-dog eyes – and you bet Khan will use

But nothing really shakes his popularity. Today, King Khan is the fifth richest actor in the world – Indian or otherwise. Aside from his production company, he also owns four cricket teams. His house in Mumbai, dubbed Mannat, overlooks the Arabian sea and is said to be worth a whopping 200 Indian crores. At 58, reinvigorated by his 2023 comeback, Khan’s career is showing no signs of flagging. The media raves about him; journalists say he rarely has beef with anyone in the industry. On-and off-screen, the SRK brand appears unstoppable. No matter the time of the day, you can find throngs of fans gathered outside Mannat, hoping for a glimpse of the star. Sometimes – like a monarch playing to his adoring subjects – he steps out onto his balcony and strikes his trademark pose: throws his shoulder back, cocks his head to one side, and stretches his arms wide open. The crowd – you can see it in videos –goes berserk.

◼ Shah Rukh Khan will be awarded the Pardo alla Carriera Ascona-Locarno Tourism tonight, 10.8 at 21:30 before the screening of Sew Torn at the Piazza Grande

◼ Devdas screens tomorrow 11.8 at 22:00 at GranRex and will be introduced by Shah Rukh Khan

Ramon and Silvan Zürcher sit with Pardo to discuss their Locarno77 Concorso Internazionale entry, Der Spatz im Kamin

by Leonardo Goi

Der Spatz im Kamin (The Sparrow in the Chimney), Ramon Zürcher’s third feature film, is the last instalment in a trilogy of highly flammable chamber dramas. Produced by Ramon’s brother and close collaborator Silvan, it follows in the footsteps of 2013’s The Strange Little Cat (Das merkwürdige Kätzchen) and 2021’s The Girl and the Spider (Das Mädchen und die Spinne). Like those earlier projects, this too unfolds as a portrait of a dysfunctional family, whose intramural tensions and feuds make for a strident clash with the films’ minimalist mise-en-scène. Shot by Alex Hasskerl, who’s lensed the Zürchers’ previous works, Der Spatz again traffics in largely static shots within a contained locale, yet it also marks something of a departure for the siblings. Starring Maren Eggert as a mother who watches her life unravel over the course of a family reunion at her countryside home, the film flirts with the oneiric and the surreal to an extent neither of its predecessors did. Few things are more thrilling than watching a filmmaker venture into new, uncharted territory; Der Spatz im Kamin is the story of a liberation - of Eggert’s character, and of the Zürchers’ fervid creativity.

Leonardo Goi: I came across a few interviews where you said TheStrangeLittleCat began with one image: someone waking up, a cat scratching the bedroom door, and another person looking at the pet. Did the same happen with DerSpatzimKamin? Did you have a particular image in mind that set the whole script in motion?

Ramon Zürcher: I started writing the film in 2014, around the time when we were traveling with The Strange Little Cat I wrote a short treatment, then began to work on the script, while Silvan wrote The Girl and the Spider. Eventually I parked the script and joined Silvan as co-writer for that film. All of this to say it really wasn’t a linear process. There was no real starting point, I wrote it in a ten-month period spread out over many years – and it wasn’t an image that started everything. Rather, it was the desire to craft something that wouldn’t unfold as a static character portrait, but would show some kind of development, a movement. That’s classical storytelling, in some ways. But I think that modern cinema has a tendency to produce rather still character studies… I wanted to show how Karen would change through the experiences she undergoes. To tell you the truth, that idea was sparked by a friend of mine who once watched The Strange Little Cat and said they’d have found it interesting if the film had ended on a completely unexpected note – like if aliens or zombies had suddenly arrived and killed everybody. A huge something that wouldn’t necessarily fit into the film’s logic. That’s what intrigued me: to construct something and then change it altogether.

LG: It feels very different from anything you’ve made before. Sure, you’re still focusing on a dysfunctional family, on intramural tensions and feuds. But the film courts the oneiric and the magical in a way none of your previous ones did. Could you speak more about this surrealist vein?

RZ: I think to some degree that surrealism you talk about is something that’s always been part of me. Back when I studied art in Bern, I’d often paint very surrealist and expressionist things. I never liked painting naturalistic stuff, but inner images that I’d project on a canvas, so to speak. I don’t like to tell or show things as they are to the eyes; I much prefer to combine them to make fluid realities between everyday life and more dreamlike situations. When I first started writing The Strange Little Cat, there were so many oneiric and bloody things in the script, but I wound up erasing them in the end; I just thought they were a bit cheap, maybe a little trashy, like B-movie elements. But then in The Girl and the Spider, those flourishes were a little more pronounced. And here, they’re much more prominent still. You feel like you’re entering a realistic story… but is it really?

Silvan Zürcher: I think this also goes back to what and how we were taught at the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (DFFB, German Film and Television Academy Berlin). We were encouraged to follow a more observational approach, and [our professors] were a little bit suspicious of anything that strayed from reality. That’s why for a while we had this in-built censorship that stopped us from thinking of ways to bring in and visualize dreams, for instance. But once we moved to The Girl and the Spider, we included some nightmarish visions, and began to explore those, and continued doing so in this film. The possibility to combine everyday life with what were almost trans-real elements was something that really intrigued us. We wanted to know what it’d feel like to go even further towards the fantastical, towards horror, but we were also guided by more formal questions regarding time and space. The Strange Little Cat takes place over the course of a day; The Girl and the Spider spans two. Here, we wanted to widen the radius; to have more time and more space. Not to confine the action to one apartment or two buildings, but to increase our scope.

LG: How did it feel to finally let go of those rules, and plunge deeper into that surrealism?

RZ: It was liberating! Back in film school I always felt as if I knew which things our teachers would like and those they might not. It really did feel like censorship. But when I painted, I was always very free. I just let go, until it became a little bit automatic, and colors and shapes would flow out of me. But it was interesting as I moved to film to restrain myself a little and be more objective, in a way – to not show my characters’ inner lives so much as observe them. That censorship was also good, in some ways. Yet it felt like driving with the handbreak on, and once you remove that, everything flows freely, as it did here. To be honest, the first draft [of the script] was even richer in these surreal elements. The final party scene was originally much larger. And there was also meant to be a hot air balloon! We wound up deleting a few things here too.

LG: Do you still paint? And do you guys usually storyboard?

RZ: I don’t paint anymore, though I draw a little bit from time to time. For Der Spatz im Kamin, once we got the floor plan of the house, we started drawing everything we could on it: where the camera would stand, where and how the actors would move, their whole choreographies, basically.

SZ: And Ramon also drew a storyboard, which we shared with the whole team so that they all had a very concrete idea of what would be on- and off-screen, how the sets would have to be decorated, the costumes we would need, and the CGI and VFX components a few shots would require. A few of these were Ramon’s own drawings and others were digitally created by a piece of software. It was a mix of different sources, but it was all storyboarded.

LG: Where and how did you find the house? More broadly, do you scout for locations before you start writing?

RZ: That would be the perfect scenario: finding the location first, and then going there to write. Here, once I finished the script we went looking for the house with our location scout in the Canton of Bern. We found two or three that might have worked, but we fell in love with that one

because of its patina: it’s a house that looks like it has a rich past already, and it was important for us that the building wouldn’t be too new or recently painted. And of course, we wanted it to be idyllic, to contrast that beauty with the film’s dark family portrait.

SZ: It was great shooting there, but it was also a big challenge. The story required a few settings: the building, a field, a hut, and then a forest – and ideally, a lake – nearby. Landing on a spot that would meet all these criteria proved very difficult; that’s why the scouting took so long. The house was so central to the story that if these spatial relations hadn’t been believable or hadn’t worked out, we would have had to change the screenplay in some fundamental ways. In the end, we were pretty lucky.

LG: You’ve worked with the same cinematographer, Alex Hasskerl, in all your films, and I’m always stunned by the economy of your filmmaking: your films all traffic in static shots and a minimalist mise-en-scène. But the camerawork is different in DerSpatzimKamin: there’s more movement, more flourishes. I’d love to hear about your visual grammar, and if you think it’s changed in any way here.

RZ: The static camera has always been the starting point for us. But Der Spatz im Kamin certainly has more movement – there’s a few dolly shots, and a scene for which we used a Steadicam. Personally, what I like about the static camera is that it carries a certain strength; it’s as if it didn’t breathe, and it feels a little bit like a prison. But this is the story of a liberation, in some ways; and I wanted the camerawork to express this vitality. For the sparrow, the chimney is a cage, and for me the whole film is the story of a bird that struggles to escape and be free again – which is basically Karen’s story. I wanted the film to start in this very static way and then break that with some unexpected movements, as when Liv, the neighbor, enters the kitchen, and there’s a traveling shot that follows her across it. The first day, when Karen’s kind of exploding, the camera remains largely locked-in, but by the next, there’s a lot more movement. It’s as if she’s starting to gain her freedom back. That’s one aspect. The other is that, for me, Der Spatz im Kamin belongs to a trilogy of films that feel a bit like theater plays, and are beholden to the unity of space and time. That’s what the static camera can convey.

LG: What explains that interest in temporal and spatial continuity?

RZ: Maybe I’m into it because I like the contrast between the freedom I can enjoy in my storytelling – the kind of dialogue I can write, the characters I can build – and the rules through which I censor myself. You know the film will only feature thirty or forty minutes inside that house, for instance, and the challenge then is to craft those characters within that time without resorting to jump cuts or ellipses. As a writer and filmmaker, that’s like a straitjacket. Your characters can say and do whatever they want, but they’re still inside that house – as if it were a theater stage. My next film will be different in that regard; I won’t constrain myself to this unity of space and time. I want to be freer.

SZ: There’s also the fact that in Der Spatz im Kamin, these two poles of chaos and order anchor the whole narrative. The fixed camera certainly heightens a feeling of stasis, but as soon as more people arrive at the house everything gets chaotic. In a way, the goal was to create a cosmos that would hinge on these two impulses – and the characters also orbit those same forces. When we started developing them, they were these almost bipolar entities stuck between order and chaos, between stillness and energy. We were talking about surrealism just now, and how embracing it in this film felt liberating; one thing that didn’t feel liberating at all was the way we were forced to deal with space and time. In the editing, there was no freedom around how we could assemble the scenes. It was very much a given because of the continuity we had to stick to. It felt like a puzzle that allowed for only one solution.

LG: I’d love to hear more about your work with Maren Eggert – how and where you met, and how you went about directing her. Her character radiates this near-extraterrestrial quality all through the film; what informed your conversations as you started crafting Karen together?

RZ: We met Maren through a casting agent, who suggested a few actresses – and she was one of them. We’d been discussing lots about what her character’s personality would be, whether we wanted someone who could heighten Karen’s more domineering side or someone who would highlight her more sensitive and vulnerable qualities, and in the end decided on the latter. And Maren’s way of acting, her voice – they kind of went against how I’d originally thought of Karen’s character. I thought that would help us complicate her a little, and turn her into someone who isn’t just a monstruous, mean mother. Bear in mind that, because we couldn’t really change the scenes much due to the continuity, I had to edit the film as it was written. I couldn’t play with the story, but I could experiment with the rhythm. I could sharpen Karen’s character to make her more or less dominant by choosing takes when she came across as softer, or cutting some lines here and there.

LG: How collaborative is your approach to directing actors? Do you leave much room for the unexpected, or do you usually come to set with a very fixed idea of how each scene will play out?

RZ: Well, working with a static camera means your actors are forced to stand on certain spots. Which means the choreography is predetermined; I must be picky about their positions on the frame. But while their physical movements may be fixed, to some degree, the way they act, how they speak, and the few things they may add to their lines, that’s all quite free. I know there are actors who feel more comfortable sticking to the script verbatim, but I’m quite open to different approaches. And that also makes for an interesting clash between chaos and order,

now that I think about it, between your rigid, fixed camera and the chaos radiating from the characters and the situations they’re in.

LG: What about non-human characters? Here too, animals play a key role in the story, and I’m always impressed by the way your films never treat them as mere ornaments, but narrative catalysts. Could you speak about their function in the film?

RZ: Almost all the animals you see in Der Spatz im Kamin belong, in some ways, to the film’s characters. Karen has a nice rapport with the cat, for instance, and Liam, her son, knows that all too well – he watches her caress and love the pet, and almost grows jealous of that relationship. She doesn’t have as strong a bond with the dog –but the neighbor does. So while the animals may seem independent, they nonetheless help to flesh out their guardians’ relationships. We also wanted the film to have animals that could fly – the sparrow, the moths, the fireflies – and heighten the fairytale, dreamlike quality of it all. These animals may be very concrete fixtures of our everyday lives, but the way we integrate them into the film flirts with surrealism.

SZ: And it also goes back to this clash between prison and freedom, between wildlife and liberation. We brought in some domesticated animals, yes, but there are also other wild creatures – like the rat the children play with, or a fish seen swimming in an aquarium – that are deprived of their potential to live truly and fully free. They’re basically caged inside this house, which mirrors Karen’s own state.

LG: The film’s score makes for another stark departure from your previous works. You still rely on a few minimalist string and piano ditties, but this time you punctuate the action with a few needle drops. Could you talk about the score?

RZ: We knew we’d have some songs that would speak to Johanna, Karen’s teenage daughter, and her girlfriends, the kind that would be close to their generation. And we also knew we’d have a composer who’d work on the whole score. It was key for us to think carefully about the tone we would channel through the music, because the film itself can sometimes feel a little claustrophobic. Would the score undercut that and inject some light into the story, or would it only amplify that darkness? Eventually, we went for the former. And right at the very end, there’s a song that plays over the end credits, which we had never heard before. I was thinking back to my friend’s comment about The Strange Little Cat and the need to introduce something completely unexpected. And I like the idea of using music to highlight that things have changed, so that something new can blossom. The track doesn’t square with the musical language of the rest of the film – it feels like a whole new vocabulary, and that’s what intrigued us.

LG: As a way to wrap things up, I was curious to hear how you feel about unveiling your new film in Locarno, a festival you’ve long frequented – first as attendees, and now as filmmakers.

RZ: Actually, the first time I travelled to Locarno was in 1999; I took part in something called Cinema Gioventù, a youth jury, and ever since then we made it a point to come back as often as we could. We’d always be camping. After I moved to Berlin for school it all got more difficult, because over summer I’d have to shoot my shorts, and I never managed to travel. But I’ve been back for the past two or three years, and I love it – it’s a festival that has such a good cinema-life balance, and I really look forward to screening the film next to so many old friends. In a way, it feels like we’re going home.

◼ DerSpatzimKamin premieres today, 10.8 at 14:00 at Palexpo (FEVI) ReadGiovanniMarchiniCamia’sreviewofthefilmonp.14

In a conversation with Pardo, Lithuanian director Laurynas Bareiša reveals the inspirations and aspirations of his sun-drenched sophomore feature, Seses, premiering in the Concorso Internazionale.

by Savina Petkova

Savina Petkova: Do you see Seses [Drowning Dry] as a follow-up to your 2021 debut Pilgrims [Piligrimai]? I ask because some of the actors return, albeit in different roles: this new film features older characters, with a family of their own.

Laurynas Bareiša: I see my characters changing the way my own family changes: they have one kid; my wife and I have one kid. So yes, that nuclear family structure is based on my own and what I know, but Seses is about two sisters who each have a husband and a child, because I wanted to explore a sibling relationship and a rather small family dynamic. And writing Seses was also a way to cope with Pilgrims’s festival journey, because presenting it involved a lot of talking about its themes of violence and redemption.

SP: Is this why a feeling of joy is way more palpable in this new film?

LB: I wanted the happy moments of Seses to be really happy, silly, and fun. Of course, I realize that the film still has a menacing feeling – like it’s all too good to be true and something bad is about to happen. But I wanted to let the characters themselves be happy in this film. In Pilgrims, it was all very gloomy and I wanted to tell that story in a fairly rigid way. For this film, we spent a lot of time in one location [the summer house] and I had a lot of talks with the actors about how they saw their characters. We improvised a lot.

SP: What was improvised? Dialogue, blocking, camerawork?

LB: I see the film in three parts: day one is at the summer house, then the middle part is still summer, but we improvised it, and the third act covers autumn, and was all scripted. The second part we came up with together over a week on set, talking about what the characters are experiencing, their reactions, and coping strategies after a significant thing happens on that first day. It’s such a strange event – it’s a non-event even, but it impacts everyone in a different way.

SP: You directed and shot this film yourself….

LB: Yes, I did both. The staging was difficult because of the improvisation, so we ended up having three or four different versions of the same scene all trying to get to the core of this strange feeling. It ended up being very useful.

SP: Unlike Pilgrims, Seses uses editing to jump between present and future. Can you elaborate on the dislocated feeling it provokes?

LB: I always wanted the film to jump back and forth in time. Also, I always envisioned using the same scene twice at different points in the film but featuring different songs each time. It’s like we keep falling into different narratives or taking different paths, maybe even parallel universes – which is a thing now. Imagining things otherwise is a way to cope with tragedy.

SP: More than a coping mechanism, memory can sometimes change things in the past or morph on its own – even though there’s not much of “the past” in this film; it’s more about the present and the future. I was thinking about that relationship to time in your films.

LB: There’s a specific relationship to the present too, as I see it. The film starts from the “past”, when it’s summer and things feel kind of strange: you see the characters are flawed, but sensitive; there is nostalgia and there are jokes – yet not all the jokes land. Only later do we find out that the beginning is told in retrospect. There’s a scene where a character is resting in bed, and we, the audience, already know this will be the last time he’s in bed, but he doesn’t. You can only have this uncanny feeling to a situation if you’re not present in it. I like that about cinema: you as the viewer necessarily have a perspective on the present that the characters themselves cannot. They’re in the present, but you’re not.

Writing Seses was also a way to cope with Pilgrims’s festival journey, because presenting it involved a lot of talking about its themes of violence and redemption.

The Killer That Stalked New York (1950) opens with the image of a woman holding a gun. Cast in shadow and draped in a trench coat, her figure looms large over the Manhattan skyline – her firearm pointed at a skyscraper. It’s a powerful image that emblematizes the danger ascribed to femme fatales in noir films, but also an epigrammatic means of introducing the moral lessons on display in Earl McEvoy’s urban drama. As the film’s opening credits roll over this still, it’s as though the woman on-screen – a diamond-smuggler who accidentally sneaks smallpox into New York City and the very killer of the title – is assigned a judgment before her story is even told. McEvoy, who consolidates the wrongdoings of a diamond-smuggler, disease-carrier, and gun-swinger into the image of one beautiful-but-devilish blonde, typifies the savviness of his era’s popular entertainment, which tacked black-and-white messages onto storylines that often took place in moral gray zones.

Playing as part of this year’s 44-film retrospective, The Lady with the Torch – The Centenary of Columbia Pictures, The Killer That Stalked New York doesn’t stand out for any of its aesthetic or narrative choices, insomuch as it exemplifies a bygone mode of filmmaking. With its fast-talking actors, newsreel-like editing, and 69-minute runtime, the film reflects an industrial mode of production that is now démodé. Inspired by the real-life smallpox outbreak that struck New York City in 1947, McEvoy’s re-imagining is as much a creative enterprise as it is a commercial product. Its blend of real-life events with noir tropes and public health advocacy makes for

By Nicolas Pedrero-Setzer

a convoluted storyline, but it also gestures at the gusto of a cinematic moment when journeymen directors were required to think hard about how to accommodate dramatic stories of a popular bent to known formulas. It was an economic mode of filmmaking that required packing action into the punchiest of entertainment packages – and thus the only way by which you could end up with a lucid pandemic thriller that doubles as a marital drama and triples as a noir tragedy while also delivering a hearty message about the importance of public health in a rapidly developing postwar city.

The film is book ended by footage of New York and an omniscient narrator’s romantic commentary about the city – “New York, the biggest town in the whole world, and because I love it, I think it’s the best.” The plot that transpires between these moments involves Sheila (Evelyn Keyes), a singer-turned-criminal accomplice, her husband Charles (Matt Krane), who has Sheila smuggle diamonds in from Cuba while he begins an affair with her sister, and Dr. Ben Wood (William Bishop), a man-of-science who spends the entire film chasing Sheila once he realizes that she’s the source of the unprecedented smallpox outbreak. As McEvoy flips between each character’s perspective, he also seems to switch genres. Whenever Sheila is on-screen, the film adopts a noir look; when Charles shows up, things slow down as the film meticulously zeroes in on the many tricks he keeps up to maintain his deceitfulness out of sight. When Dr. Wood is the picture, the film either lurches into newsreel territory as it narrates the benefits of getting vaccinated, or steeps itself

in the procedural domain of an investigative thriller. The tonal whiplash of these transitions provides the film with much of its dynamism as genre tropes piling up in quick succession, ostensibly to meet studio demands and, intentionally or not, to reveal the volatile energy of a city populated by folks from all walks of life.

The only stable source of drama in The Killer That Stalked New York is Sheila. With Evelyn Keyes in the titular role, Sheila’s fall from grace is represented in high fashion, with Keyes giving her character unabated wide-eyes along with a slick gait – hers is a perfect balance of paranoia and confidence. It’s this very combination that also means the film diminishes her struggles, presenting Sheila as a woman unwilling to accept her fate; in this case, either prison, death due to smallpox, or both. The depth Keyes brings to her character – the rage she hurls at her sister after discovering her husband’s infidelity, the anguish she voices about her lapsed career in show business, and the courage that consumes her whenever she finds herself in a tight spot – counts for very little in the narrative. McEvoy seems only interested in delivering a message about how criminals always get caught and how to act in the case of a pandemic. Not so much person as placeholder, Sheila – and all her woes – are secondary to an insistence on fast action and high drama. Her role, like that of many femme fatales, is purely symbolic and pre-figured by the cultural myths of her time. Though frustrating, her character’s superficiality – a result of the film’s inability to slow down and probe her psyche – conforms to

Qualunque sia il luogo di vostro interesse, noi sosteniamo chiunque desideri una consulenza previdenziale e finanziaria personalizzata.

Per una vita in piena libertà di scelta.

Emozioni uniche al Locarno Film Festival con la Posta.

American-Swiss director Freddy Macdonald channels bleakness and thrills à la the Coen Brothers to introduce a seamstress sewing her way out of a dangerous stitch-up.

by Savina Petkova

Sometimes, a needle and thread are all you need to get out of a sticky situation. This statement, however peculiar it may seem, proves true for the headstrong protagonist of Sew Torn, Barbara Duggen. You’ll meet her in tonight’s Piazza Grande offering, a black comedy thriller debut by American-Swiss director Freddy Macdonald. Rich in action and allegory, Sew Torn is held together by its fascinating main character: Barbara – played by Eve Connolly, whom you may know from the TV series Vikings (2013-2020) – is a mobile seamstress, serving clients, though not many, in a picturesque valley in the Swiss Alps.

As she’s doing the rounds in her Volkswagen Beetle, one already suspects that her little car is more of a home than her physical one. Meanwhile, her house-slash-shop remains persistently empty. Connolly’s ever-serious expression conveys Barbara’s imposed independence as an orphan – through circumstances unknown – tending to a dying family business. She doesn’t seem to mind monotony, which is just as well, since the town’s Alpine calmness doesn’t allow for anything out of the ordinary to happen. And so, Barbara floats through life, working in isolation with no thirst for adventure at all. Until, that is, the day everything changes for her.

On the road, Barbara stumbles upon the site of a very fresh accident. What at first seems like a car crash was more probably, we gather, a shoot-out: there are two injured men sprawled across the asphalt and between them, a briefcase and a gun. Faced with this curious setting and nobody around, the seamstress must choose: she could just drive away, she could call the police, or – she could commit a perfect crime. Well, Sew Torn takes all three routes. Barbara is allowed to pursue each narrative path, one after the other, and the viewer to see how they unfold, what their outcomes are. “Choices, choices, choices,” she whispers to herself – and the viewer – while considering her next move.

This is not the first time Macdonald has put his protagonist at a metaphorical crossroad. Sew Torn evolved out of his 2019 short of the same name. The two share this crucial central sequence, which was actually born of a film school application brief which read simply: “a change of heart”. For his economic storytelling and expert buildup of suspense peppered with dark humor, the director draws inspiration from the work of Joel and Ethan Coen, like No Country for Old Men (2005) and Fargo (1996). Macdonald’s short quickly caught the attention of Searchlight Pictures, who acquired the film and screened it in theaters alongside the revenge horror-comedy Ready or Not (2019), by directors Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett. With this blessing, Macdonald could dream bigger and develop the story of Barbara in more depth.

To that end, he brought in his father Fred Macdonald to help write the feature-length script, and recruited cinematographer Sebastian Klinger – whose dynamic camerawork enables each version of events to unfold in increasingly thrilling ways. However, even before the criminal subplot kicks in, the film takes great care with its setting and props, using their materiality to foreshadow everything that is to come. As both a thriller and a dark comedy, Sew Torn relies on its thickness of atmosphere and its sense of impending doom, which at times cuts against its tranquil backdrop. The film was shot in Bad Ragaz – where the 19th century Swiss author Johanna Spyri wrote her infamous children’s novel Heidi (1880-81) – and it’s intriguing to see this landscape, as captured in wide shots, acquire an aura of dread. When it comes to interiors, the most intricately choreographed sequences are those that unfold in Barbara’s house slash fabric shop, her childhood home.

There, the mobile seamstress lives alone but is never truly alone; nestled amongst the impressive web of yarn spooled all across the ceiling are photographs of her younger self and her mother. This labyrinth of threads is so neatly organized that a single pull of a cord elicits a voice recording, making any picture ‘talk’ with the voice of mother or daughter. Hence the sign hanging on the wall proudly declaring this the “Home of the talking portraits”. With Barbara’s parents gone, this meticulously handcrafted approach to the family archive now makes the house seem more like a museum than anything else. Much as the yarn serves as a link, literal and metaphorical, to a past unknown, Barbara’s sewing kit helps her navigate the present. It is also a weapon that allows her to do extraordinary things – from triggering a gun without even touching it, for instance, to setting a given room with lethal booby-traps.

Multiple scenes across the three narratives depict Barbara in the process of building these webs and traps, just by looping her thread through furniture and expertly tying it to places one would never otherwise think of; she makes of it an artform. She has an engineer’s perspective when it comes to space, and the film does a great deal to show us the inner workings of Barbara’s mind through the unconventional use of her skillset. At the same time, the act of showing these convoluted processes toys with the viewer’s anticipation: we want to see the dominoes fall – the grandiose results of her painstaking labor.

The idea that a woman’s hands can just as easily craft a trap as fix what’s broken informs Sew Torn on a deeper, symbolic level. Barbara’s sewing skills and the unorthodox uses she puts them to draws attention to a lengthy tradition of female domestic labor – but what Macdonald’s film shows us is that women are wont to fight against domestication, even if they have to do it with a needle and thread.

◼ Sew Torn screens tonight at the Piazza Grande after the 21:30 screening of César Díaz’s Mexico 86

Il regista messicano-belga César Díaz esplora l’ambivalenza della Storia e le esperienze personali che si celano dietro al suo secondo lungometraggio, Mexico 86, proiettato stasera in Piazza Grande.

di Savina Petkova

Il protagonista del film d’esordio di César Díaz Our Mothers (Nuestras Madres, 2019) era un archeologo forense in cerca della verità sul padre, scomparso durante la guerra civile in Guatemala negli anni Ottanta. Oggi, con Mexico 86, il regista, nato in Guatemala, ritorna sullo stesso periodo storico di un Paese dilaniato dalla guerra. In questo suo secondo lungometraggio, Maria (Bérénice Béjo), una militante della resistenza divenuta madre recentemente, prende la dura decisione di lasciare il figlio Marco (Matheo Labbé) in Guatemala quando è costretta a fuggire in Messico. Una decina di anni dopo, il bambino, sperando in un futuro migliore, decide di rivedere la madre. Accompagnato dalla nonna e con un passaporto falso, la incontra in Messico, dove lei ha continuato a lottare sotto copertura per la giustizia e l’attivismo rivoluzionario.

Nelle opere toccanti di Díaz madri e padri sono più che meri riflessi di una patria travagliata, il Guatemala; le relazioni fra genitori e figli simbolizzano infatti la difficoltà di conciliare il proprio passato al presente, in cui la dimensione personale, politica e sociale s’intersecano. A prima vista Mexico 86 è un dramma storico dal ritmo serrato: Maria sarà in grado di mantenere la sua copertura in Messico? Lei e Marco potranno creare quel legame genitore-figlio rimasto irrealizzato per una decina d’anni? Durante la nostra conversazione con Díaz abbiamo esplorato gli aspetti meno evidenti del film, come la cura con cui il regista ha creato i suoi personaggi e la sua relazione ambivalente con il passato.

Savina Petkova: Dopo aver visto i tuoi due film, uno dopo l’altro, ho come avuto l’impressione che Mexico 86 esistesse nella tua mente prima di OurMothers, il tuo film d’esordio. È così?

César Díaz: In realtà sì! Our Mothers è nato come un progetto di fine studi, nel 2012. Come puoi immaginare, ci è voluto tempo per svilupparlo e finanziarlo. Alla fine abbiamo ottenuto dei soldi dal Belgio, ma comunque ci è voluto un po’ [per produrlo]. Nel frattempo, ho cominciato a scrivere un film intitolato Call Me Mary: una storia su una donna guatemalteca emigrata a Bruxelles che ha dovuto lasciare il figlio in patria. Dieci anni dopo lui va in Belgio a cercarla. Quello è sempre stato il fulcro di Mexico 86: due persone che, anche se madre e figlio, non si conoscono e devono imparare a convivere. In quel periodo però tutti i riscontri che ricevevo si riferivano al film come ad una storia di migrazione e non era ciò che volevo creare. Quando uno dei miei produttori mi ha chiesto da dove venisse l’idea di Call Me Mary gli ho raccontato di come mia madre avesse lasciato il Guatemala per il Messico, e di come io fossi cresciuto con mia nonna. Mi ha detto: “Perché non scrivi quella storia?”

SP: Sembra un invito a rendere la narrazione più personale. Come ti approcci a questi elementi quando si tratta di creare i tuoi film?

CD: È che, vedi, ho bisogno di un tema, di un personaggio al quale legarmi profondamente. Quando insegno, consiglio sempre ai miei studenti di scegliere un tema o un soggetto che sta loro a cuore, perché ci dovranno convivere per cinque, 10 anni, o più. Se non lo ami davvero lo abbandonerai. Per me, a dirla tutta, è un modo per conoscere meglio i personaggi in quanto persone e capire cosa provano in certe situazioni. Penso che sia in questo senso che la mia esperienza personale mi aiuti a fare film. La mia identità mista guatemalteca-messicana-belga inoltre mi è stata di grande aiuto per finanziare il tipo di film che voglio fare [grazie a co-produzioni e finanziamenti europei]. Viviamo un momento in cui il nazionalismo sta crescendo e le nazionalità si stanno allontanando, ma dobbiamo ricordare che il cinema è una lingua universale.

SP: Una cosa che mi ha colpito di questo film è il fatto che Maria e Marco non sono davvero madre e figlio, nel senso che loro non si rispecchiano in quei ruoli: lei è una militante alla ricerca della verità e lui un bambino di 10 anni. Dato che non sono legati da una relazione famigliare, come hai costruito una narrazione nella quale si avvicinano e si allontanano ripetutamente?

CD: La mia sfida dal punto di vista narrativo era di evitare che il bambino diventasse un fardello. Se mai lo fosse diventato lei avrebbe rinunciato ad instaurare un rapporto. Eppure, dovevano condividere quel sentimento indistinto di appartenere l’uno all’altra, senza sapere esattamente perché. Da un punto di vista narrativo, credo che questa sia una storia di formazione per Marco, ma per Maria è ovviamente diverso. La sua vita è guidata da un obbiettivo [l’attivismo rivoluzionario] e lungo la strada incontra molti ostacoli; Marco è uno di questi. È questo il motivo per cui la crescita di Marco è così toccante per me: arriva a capire le ragioni che hanno spinto la madre a lasciarlo. Prendere una decisione non perché non ami qualcuno, ma perché sai che non hanno spazio per te nelle loro vite è una cosa bellissima.

SP: Ed incoraggiante! Sempre più spesso nei film storici i bambini sono o una responsabilità o un sentimento astratto – “i bambini sono il futuro” – ma Mexico86va controcorrente. Come hai ideato la storia di Marco, un giovane ragazzo unico e al contempo qualcuno con cui ci si può identificare?

CD: Inizialmente, tutti quelli che hanno letto il copione hanno commentato il fatto che la storia non fosse narrata dal punto di vista di Marco. Penso che nell’immaginario collettivo ci possiamo identificare con quel tipo di personaggio-bambino facilmente. Basti pensare a I 400 colpi (Les Quatre Cents Coups, 1959), o il film argentino Infancia Clandestina (Clandestine Childhood) del 2011; siamo abituati a questo tipo di cose come spettatori. Per Mexico 86 sapevo che non avrebbe funzionato, perché il pubblico avrebbe finito con il giudicare Maria; sarebbe sembrata una “cattiva madre”, qualsiasi cosa questo voglia

dire, e avrebbe oscurato le complessità della sua causa e del suo sacrificio. Quando segui il suo punto di vista ne comprendi la posta in gioco, quanto sia importante la sua causa, e quanto profondamente lei creda nel trasformare la società.

SP: Il film è dedicato a tua madre: il personaggio di Maria è ispirato al suo attivismo durante la guerra civile in Guatemala o a conversazioni avute con lei?

CD: Sì, chiedevo a mia madre e ai suoi compagni: “Perché?”. È una lotta così difficile e dolorosa, soprattutto quando si insinua nel tuo contesto famigliare; sei continuamente costretto a prendere decisioni difficili. Ma loro mi rispondevano: “Perché volevamo creare un mondo diverso per te e la tua generazione”. Penso che ci sia qualcosa di nobile in questo, perché non pensi a te stesso e sei cosciente del fatto che una trasformazione sociale e politica richiede tempo. Potresti non vivere abbastanza a lungo per vederla con i tuoi occhi, ma puoi comunque affidare un mondo migliore a coloro che verranno dopo di te. Abbiamo bisogno di persone come il personaggio di Maria, se stiamo seduti in silenzio e poi andiamo ad una protesta di tanto in tanto non cambierà nulla.

SP: Come ha funzionato invece il casting? Hai preso in considerazione questi aspetti quando hai scelto Bérénice Béjo per interpretare Maria e Matheo Labbé per il ruolo di Marco?

CD: Bérénice mi è sempre piaciuta in tutto quello che ha fatto, ma all’inizio stavo cercando un’attrice guatemalteca. Nessuna delle persone che ha fatto il provino era in grado di restituire quell’intensità di cui avevamo bisogno e di interpretare il personaggio di Maria. Poi ho visto un film argentino in cui Bérénice Béjo parlava spagnolo e ho realizzato in quel momento che è argentina. È scappata dalla dittatura. È a quel punto, penso, che ho cominciato a immaginare il personaggio con le sue fattezze, ma non ero certo che quell’idea sarebbe andata in porto. Parlare con i produttori è stato stressante, perché in passato fu nominata per un Oscar, ma erano incoraggianti e volevano almeno provarci.

SP: Immagino che vi siate incontrati di persona e che forse le vostre storie di emigrazione vi abbiano aiutati a stringere un legame.

CD: Esatto! Ci siamo incontrati a Parigi dopo che aveva letto il copione. C’è subito stata una forte intesa e non abbiamo neanche nominato il film! Abbiamo parlato delle nostre esperienze per ore ed ore, da soli, e poi alla fine ho detto qualcosa come: “Ma ti piacerebbe davvero fare questo film?”. Al che lei ha risposto: “Certamente!”. Un sogno diventato realtà.

SP: E Matheo? Questo era il suo primo ruolo.

CD: Sì, per trovare il Marco giusto ci è voluto molto tempo. All’inizio tenevamo dei provini per bambini senza copioni o battute. Incontravamo i ragazzini, ci parlavamo, poi presentavamo loro delle situazioni per vedere come reagivano. Osservavamo anche il loro linguaggio del corpo, quanto riuscissero a concentrarsi e che cosa funzionasse per loro. Quello che ha distinto Matheo – e penso che sia stato in un certo modo determinante – è il fatto che ha il diabete da quando era molto piccolo. È ancora un bambino però allo stesso tempo, a causa dei suoi problemi di salute, è molto maturo. Per il personaggio di Marco avevamo bisogno di qualcuno che potesse crescere molto in fretta e Matheo, nella sua vita, ha dovuto farlo. Per quanto riguarda il lavoro sul set abbiamo concordato con i suoi genitori che sarebbe stato meglio non dargli il copione intero. Abbiamo lavorato quindi scena per scena: ogni giorno riceveva una nuova scena per il giorno successivo e un poco alla volta ha scoperto il film nella sua interezza.

SP: Hai girato il film in Guatemala e in Messico. Le due esperienze, da un punto di vista personale e dell’industria, sono state molto diverse?

CD: Girare in Guatemala era un po’ come essere a casa, perché avevamo la stessa equipe che per Our Mothers, le stesse persone. Era però diverso perché ci conoscevamo meglio e potevamo esplorare più in profondità certe scene, o lavorare più velocemente. È stata un’esperienza magnifica. Per esempio, la cinematografa [Virginie Surdej]

ed io non dovevamo neanche parlare perché avevamo lavorato molte volte insieme prima di allora e abbiamo gli stessi riferimenti. Questa volta eravamo lì insieme, camminando per strada potevo mostrarle i luoghi dove era successo quanto descritto nel copione, inclusi i massacri. È a quel punto che le cose si sono fatte vere per entrambi. Condividere quell’esperienza è stato molto speciale per tutti coloro che erano lì.

SP: Il Messico è stato diverso, suppongo.

CD: Come sai, il Messico ha un’industria cinematografica gigantesca. Un giorno eravamo 50 persone sul set in Guatemala, il giorno dopo 125 in Messico. Sinceramente per me è stato uno shock, vedere tutta quella gente correre in giro…è un modo molto diverso di lavorare. Non sto giudicando! Dico solo che è difficile passare da una squadra molto piccola, quasi una famiglia, a più di 100 persone da un giorno all’altro. Mi dicevano: “Sì signor Díaz, No signor Díaz” e rispondevo sempre: “Il mio nome è César, ok? Smettiamola con queste sciocchezze” [ride]. Ho certamente avuto bisogno di un momento per abituarmi. È lì che ho potuto imparare a girare scene d’azione, cosa che prima non avevo mai fatto. Per fortuna il mio primo assistente alla regia [Pierre Abadie] aveva girato molte scene d’azione e sapeva come lavorare su quel tipo di set. Era come avere un coach [ride] e ho davvero amato ogni lezione.

SP: La storia di Mexico86comincia nel 1976 in Guatemala, che è anche il periodo di cui tratta Our Mothers, anche se quel film è ambientato ai giorni d’oggi. In altre parole, il passato traumatico che fa da sfondo al tuo primo film diventa il tempo presente di quello nuovo.

CD: Beh, quello è stato il periodo più buio della storia recente del Guatemala. Onestamente è anche una mia ossessione e paura, ero terrorizzato durante quel periodo. Ricordo gli attacchi, la polizia e come il dittatore appariva in tv così spesso da essere diventato quasi un nostro amico. Ricordo anche come ho lasciato il Paese. Quindi per me ritornare è stato un modo per confrontarmi con il passato. Per quanto fosse oscuro e difficile, c’era pur sempre speranza, perché la generazione dei miei genitori, come ho detto, credeva davvero di poter cambiare la Storia e trasformare la loro società.

SP: Come è stato ritornare nel Paese nel quale sei cresciuto, il Messico?

CD: È stato davvero come tornare ai miei ricordi. Sono cresciuto in Messico ed essere lì mi ha certamente aiutato a ricordare come era all’epoca. Ma devi tenere a mente che la versione di Città del Messico degli anni Ottanta che ricordo non esiste più. In quegli anni era certo una città incredibile, ma era pur sempre…non so come spiegarlo, era umana, o almeno facilitava i legami tra le persone. Per esempio, quando andavo a scuola a 10 anni attraversavo tutta la città, da nord a sud, con i mezzi pubblici. Ma oggi nessuno lascerebbe mai farlo a un bambino di 10 anni e il tragitto è di due ore e mezza. Città del Messico è diventata gigantesca e fuori controllo, o almeno al di fuori del controllo dei suoi abitanti…

SP: Potresti invece parlarci della decisione di ritornare su quel periodo storico?

CD: Onestamente penso che questa sia l’ultima volta che ritornerò su quel periodo. È stato molto importante per me farlo perché penso che sia un modo efficace di confrontarsi con la storia recente dell’America Latina. I film storici oggi sembrano dirci: “Sai cosa? Noi c’eravamo 40, 50 anni fa. Non dovremmo essere tornati indietro!” Giusto la settimana scorsa ho visto alcune immagini di persone che venivano arrestate, in Argentina, e mi hanno ricordato un passato non così lontano. Se fossero state scattate negli anni Ottanta quelle immagini sarebbero state uguali. È terrificante, ma dobbiamo ricordare. La ragione per cui facciamo film è ricordare alle persone che questo può succedere di nuovo e non possiamo lasciare che ciò accada, perché abbiamo imparato dal passato –o almeno così spero.

◼ Mexico 86 screens tonight, 10.8 at 21:30 at the Piazza Grande

by Giovanni Marchini Camia

The wonderfully orchestrated films of Ramon Zürcher propose an image of the family that is far from harmonious. As such, it’s almost ironic that he should have made them with his brother – in fact, his twin – Silvan, who acts as the producer and sometimes also shares writing and directing duties. Home is the overarching theme of their first three features, a trilogy that comprises The Strange Little Cat (Das merkwürdige Kätzchen, 2013), The Girl and the Spider (Das Mädchen und die Spinne, 2021), and now concludes with Der Spatz im Kamin (The Sparrow in the Chimney). The house of Der Spatz im Kamin might appear idyllic, surrounded by nature and bathed in sunshine, but step through the front door and you’ll find yourself in a pressure cooker. Karen (Maren Eggert) grew up there, and moved back with her husband and children after the death of her parents. Her sister, who has just arrived with her own family for the weekend, can’t understand why she would want to live in that house again. Isn’t the whole place haunted by awful memories? The occasion for the visit is a birthday, but the past, in the form of unresolved conflicts and suppressed traumas, seems intent on ruining the festivities. As more and more people arrive, we slowly start to make sense of the constellation of characters and their complex backstories. Titular sparrow aside, a whole range of animals– including a dog, a cat, chickens, butterflies, fireflies, even a rare marine creature – appear as uncomprehending witnesses to (and, in one gasp-worthy instance, participants in) the drama, fuelling the general confusion and our own impression of being cast into an emotional whirlwind.

It could all make for an overly intense viewing experience if it weren’t for the grace of the filmmaking and the profound humanity conveyed by the performances. Despite the large cast, every character is finely drawn and given due space within the story, which allows the actors to embrace and explore their anguish, desires, and manifold contradictions. The house itself is instrumental and the film nimbly takes us from room to room, character to character in an intoxicating choreography. Then, gradually and almost imperceptibly at first, things start to shift. Surrealist elements creep into the narrative, small yet ominous events contribute to a mounting sense of foreboding, until what began as a naturalist portrait of a family suddenly swells into something very different and very exciting.

The surprise is best left unspoiled. Suffice it to say that the second half of Der Spatz im Kamin takes the Zürchers’ cinema into unexpected new territory, bringing their trilogy of troubled domesticity to a sensational close.

by Stefan Ivančić SELECTION COMMITEE

This is not Lithuanian director Laurynas Bareiša’s first time at Locarno: his short film Caucasus premiered in the Pardi di Domani in 2018. Since then, his career has been triumphant: he showed his short Dummy (2020) at the Berlinale before going on to win the Best Film award in the Venice Film Festival’s Orizzonti section with his debut feature, Pilgrims (Pilgrimai, 2021). With Seses (Drowning Dry), his sophomore feature, he’s stepping onto the stage of the Concorso internazionale, Locarno Film Festival’s main competition.

Bareiša’s films could be described as films of movement – precise movement articulated through the mise-enscène and an active camera – which comes as no surprise considering his background as a cinematographer. This movement is not a mere exhibition, but is crafted as to reveal something hidden, something that is present in the captured reality of the film, but still lies beneath the image’s surface. Movement, along with time (the rhythm, the pacing, the duration of the shots and the attention to something that might appear insignificant at a glance), makes this hidden thing lift up out of the background and come to the forefront. The movement in Caucasus revealed the ghost of fascism, come to haunt Europe (premonitory, indeed); in Pilgrims, what’s unveiled is the supressed but ever-present violence in all corners of the spaces we inhabit, and how the consequences of a crime that remains undefined affect the victims. In Seses, this movement takes another shape, an optical one – a tense and threatening zoom, that is. The zoom does not exist in reality – it is an illusion, a creation of cinema. It is as if Bareiša is telling us that the dislocation of his characters, their breakdown, is a temporary, unnatural state of mind. It will take them some time to reconstruct themselves and heal.

“Dry drowning” or “secondary drowning” is a term that denotes a rare complication that can develop after water enters the lungs. It is possible for a very small amount of water to irritate the mucosa, causing fluid to accumulate in the lungs and lead to a pulmonary edema. This medical condition, in which respiratory distress occurs some time after the initial event has passed, constitutes not only the film’s plot, but the axis of Seses’s narrative structure. Through a fragmented narrative, by going back and forth in time, Bareiša explores the interplay between the mundane aspects of life and pivotal, life-changing moments. Two sisters (Gelminė Glemžaitė and Agnė Kaktaitė) live according to an uninspiring routine, suffocated by their husbands’ toxic masculinity – until an accident shakes the foundations of their reality. At that moment, the film begins to question the nature of emotional trauma and how that can affect its very form, its structure. How to deal with shock, not only in real life, but also in cinema? How does life go on, and what kinds of changes are engendered within? How does one’s memory recall a distressing event – and is it remembered in the exact same way by everyone involved? By using discontinuity, little by little, Seses reconstructs the broken mosaic of memory that arises after a traumatic experience.

Read Savina Petkova’s interview with Laurynas Bareiša on p. 8

by Julia Schubiger SELECTION COMMITEE

Spanning four extremely diverse and powerful shorts, How Are Our Children Doing? is a program that aims to reflect on the state of our world as it is inhabited and experienced by young people today. Kids are our future, and what preoccupies them should be our priority; join us in exploring their stories!

After two features unveiled in the Un Certain Regard sidebar at Cannes, Personal Affairs (2016) and Mediterranean Fever (2022), Maha Haj comes to Locarno with a quietly shocking and heartbreaking story from Palestine. Her film may very well be set in a not-so-distant future, but it speaks to today’s tragedies in Gaza and Israeli-occupied territories, lending a voice to those who are struggling to be heard, as well as to those who can no longer speak.

The second film of the program is by Swiss director Samuel Patthey, who made his Locarno debut with ECORCE, which later won Best Short Film at the Annecy Festival. Now, he returns with Sans Voix (Voiceless), a hallucinogenic tale of a raver which swings between existential questions and anxiety. When his eyes meet those of a baby, everything changes.

Malaysian society conceals deep intramural tensions in WAShhh. Directed by Mickey Lai and set in a state-run camp for young women, the film chronicles some of these frictions as they reach a climax over different beliefs about the female body. The violence perpetrated against women in patriarchal societies is extreme, and is committed by both men and women—a product of tendencies learned from a very young age.

The program closes with Gender Reveal. True to its title, this comedy directed by Mo Matton tackles these prenatal parties by highlighting their absurdity with humor and through a queer lens. This need to dramatically and often extravagantly reveal a baby’s sex before birth underscores society’s obsession with binary gender norms.

So how are our children doing, really? Judging from these four shorts, while kids today face complex and often harsh realities, their voices and experiences are vital in shaping a more empathetic and understanding future. Let’s hear them!

By Savina Petkova

How often do you ask yourself whether you’ve done the right thing in a certain situation? Don’t worry – this is not the Morality Police knocking on your door, but Foul Evil Deeds by writer-director Richard Hunter will surely make you wonder. It would be fairly accurate to describe this British entry in the Concorso Cineasti Del Presente as an anthology of maleficence, since this debut is about people doing bad things – to each other, but really, to themselves. Despite the title, however, it’s not always easy to pinpoint what the “evil” is in Foul Evil Deeds. Firstly, because of its fragmented structure, and secondly, because each of the film’s short episodes are experiments in unease more than out-and-out atrocity. In the opening scene, a cleaner (Alexander Perkins) witnesses a rather brutal fight and just stands there, watching from a safe distance. Though quiet and unassuming, is complacency not a moral sin?

In another episode, an elderly couple is thrown into dismay as maggots appear seemingly out of nowhere in the closet of their house: the camera zooms in on two maggots writhing on the soft carpet. Wife Claire (Tracy Bargate) makes her husband Andrew (James Benson), a vicar, investigate the attic – where the camera discovers the dead rat in which the maggot colony is thriving. The rat is duly disposed, but an awful smell persists in the following scenes. It’s even strong enough to later interrupt Andrew’s clandestine jerk-off routine: without pausing the porn on screen, he leaves his seat to spray the room with air-freshener all over. The rot and the stench seem to imply a festering marriage.

The film’s multiple stories keep interrupting one another, with some of the fragments lasting less than a minute, others, a few, but they all share a home video aesthetic thanks to the mini DV camera used. More importantly, these interruptions serve a purpose.

The way in which Hunter punctuates each fragment with a cut to black, hold, cut back to image makes the film a living, breathing thing, while Matthew J. Brady’s rhythmic editing puts the spectator to work piecing each story together. Cinematographer John Fisher keeps the camera static and stagnant – and steady on those very few occasions when movement is necessary. Either a slow and controlled pan or more often a zoom are the only interactions between the camera and the mise-en-scène.

“We did the right thing,” Claire says to her husband after another ambiguously malign deed is done. Even when the characters justify their actions to others, Hunter himself does not pass judgment. It’s up to the audience to contemplate their own morality, and recognize that they’re no better, nor worse, than the people on screen.

Amongst online gamers, the phrase “skill issue” is used to denigrate those who struggle with the gameplay; who lack the know-how and/or precision required to keep up, let alone get ahead. In Willy Hans’s sun-dappled, somnolent first feature Der Fleck – following on from the filmmaker’s debut Locarno appearance in 2019, with his short Das satanische Dikicht – DREI (The Satanic Thicket – THREE) – the first interaction we see between gangly, green-eyed protagonist Simon (Leo Konrad Kuhn) and a group of his peers suggests that he might have something of an IRL skill issue. Spotting a loose group of teens dawdling on the high school grounds, he stares at them but keeps his distance, as if torn between approaching and moving on. A few raise their hands by way of reluctant or maybe just baffled acknowledgement, before then exiting the scene. Simon – who has just, in an act of pure caprice, bailed on gym class – ambles off too, his destination seemingly undefined. At an underpass, the camera lingers on the sole piece of graffiti, which doubles as the film’s English-language title: “SKILL ISSUE” it reads – affirming something we already suspected about the young man. Soon, Simon is intercepted by an old friend (Shadi Eck), who offers him a diversion in the form of a trip to a nearby river. There, a gaggle of young people have gathered in the name of wiling away a sticky summer’s day – but Simon does not quite gel with them either. He remains on the periphery, again oscillating between engagement and autarchy. Until, that is, he notices Marie (Alva Schäfer): with her headphones in, sporting bedraggled green hair and clad in artfully baggy layers, she also seems to exist as an outsider within the group. When the two of them peel off together – each curious about the other, but their overtures curtailed by a certain spiky skittishness – the film seems to enter a state of enchantment-tinged suspended time, as if Simon and Marie had wandered into a very low-key iteration of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. As bolstered by Paul Spengemann’s luminous and laidback 16 mm cinematography, there is something in Der Fleck of the woozy, moody poetry of Human Flowers of Flesh (LFF 2022), Helena Wittmann’s dialogue-light Mediterranean odyssey – and indeed, Hans’s film has come out of the same production house, Fünferfilm.

Der Fleck resists becoming just a budding romance, however; it is something stranger, less anthropocentric, even. Spengemann’s camera is prone to straying away from the film’s human subjects – sometimes, it seems a stand-in for Simon’s roving attention, as in one extended shot where the focus shifts from another character’s face, seen in close-up, to the greenery in the background; at other times, the camera seems a character in its own right, pursuing a line of inquiry along the river’s overgrown shoreline independent of the so-called ‘action’. So too will viewers pursue their own interpretation of Simon and his maundering stolen day.

Pierre Jendrysiak was at the press conference on Friday, 9.8 for Ben Rivers’s latest film

While Bogancloch might seem confusing and mysterious, it is everything but. Clear to the point of being almost self-explanatory, the film “is about feeling”, Ben Rivers said in his press conference while fielding questions about rhythm and music. Joyful and easy-going – a far cry from the austerity suggested by the conceit – the director happily addressed ambiguities in the film, revealing more about the past of its protagonist: his previous life as a seaman, his travels across the Middle East, and the strange audio tapes he’s always playing in his secluded house in the middle of the woods. “I like the idea of sequels,” Rivers said. He considers Bogancloch one to his short film This Is My Land (2007) and his first feature Two Years at Sea (2011). In his latest, Rivers again documents the daily routine of Jake Williams – as he had in Two Years at Sea – a hermit living alone in a remote corner of the Scottish Highlands. When asked about the idea of living in this area, Rivers said, “the Scottish wilderness is calling me,” even as he admitted that “adjusting” between London and these lands was getting “harder and harder”. Easy as it may be to write off Williams as a standoffish, unfriendly figure, Rivers quickly rejected that idea. “He is not at all misanthropic,” adding that the man’s life is “not utopian”, and not all that different from ours. In fact, it might just be a poetic distillation of our own existences. As Rivers beautifully put it, while suggesting that the song that’s sung late into Bogancloch, “The Flyting o’ Life and Daith”, might a metaphor for Williams’s lifestyle, it is “a battle between life and death, but at the end, it becomes hopeful.”

PIERRE JENDRYSIAK is a participant in the Locarno Critics Academy, the Festival’s workshop that prepares emerging critics for the world of film festivals and professional writing about cinema.

Grande cinema in Piazza Grande o a casa, con blue TV.

Pronti, insieme.

In the weeks leading up to the Festival, we reached out to some of Locarno’s most illustrious former guests and asked them to share their first memories of the fest – whether that meant impressions from their world premieres or casual walks around the lake. The result, Beginnings, is a treasure trove of anecdotes and recollections; a polyphonic mosaic of the Festival assembled by those who’ve shaped its history.

I came to Locarno for the first time to screen A Spell to Ward off the Darkness, a film that I co-directed with my good friend Ben Rivers. I arrived via Helsinki via Kittilä, having spent a few days traveling deep beneath the earth’s mosquito-covered surface in a series of Finnish gold mines, scouting out locations for a film called Good Luck that would bring me back to Locarno a second time four years later. I arrived on the day of our film’s premiere, which was in a cinema called PalaVideo that was memorable for its red seats and its incredibly steep incline – and for the tendency of its ushers to occasionally shine flashlights upwards onto the screen. I’m sure they did it just once or twice, directing late viewers to the rafters above, but after all of that nervous energy that comes with finally presenting a film to the public, I couldn’t help but think how those ushers were already doing our film’s job of pushing away the darkness, LOL.

It always takes me a while to properly see a film after I’ve released it into the world – my attention remains in the unresolved technical details, the uncertainty of proper sound levels, the collective exhalations of an audience that I’ve never been with in a cinema before. Our film was part of a new non-competitive section called Fuori Concorso Signs of Life that Carlo Chatrian had just created. Ben and I were of course honored to be among the new gatekeepers, happy to finally have the film out in the ether, excited and maybe a little bit disappointed that nobody in the audience booed after the closing, 25-minute long black metal sequence – which is a result that we’d imagined at some point during our editing process. I’m sure there was a Q&A but I can’t remember it – and I’m sure that we both felt relieved and excited, and a bit outside of everything.