A. Nazzaro

Benvenuti a questa questa 77esima edizione del Locarno Film Festival. E benvenuti a Locarno nel segno del cinema, della pellicola e del proiettore. In queste piccole conversazioni quotidiane lungo i giorni del festival, proviamo a ragionare su cosa significa - oggi - lavorare e condividere il piacere del cinema in tutte le sue forme. E iniziamo con una riflessione sulla pellicola e il suo fascino che resiste a tutte le mode. 35 mm. 16 mm. 8 mm. Chi se li ricorda più i formati tradizionali della pellicola cinematografica? Già. Una volta le pellicole, le “pizze” in gergo, erano la materia prima dei festival. Poi, con l’avvento del digitale, la pellicola è stata relegata in un angolo della memoria collettiva. Eppure, proprio come è accaduto con il disco in vinile a 33 giri, la pellicola non solo ha conosciuto una rinascita, ma è più che mai decisa a non abbandonare il campo. Il Locarno Film Festival, da sempre, sta al fianco del proiettore e della pellicola cinematografica, pur consape-

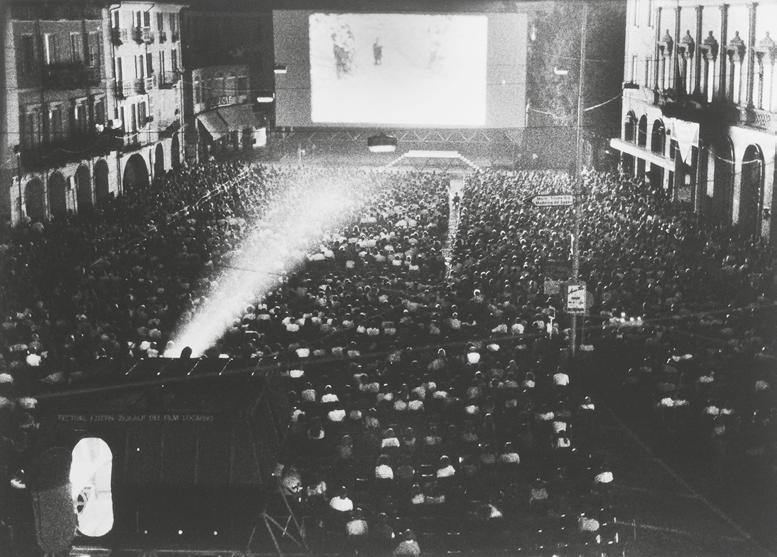

vole dei vantaggi introdotti dal digitale. Quest’anno, sin dal prefestival, è stato un fascio di luce “analogico” a illuminare la Piazza Grande: la magia di E.T. di Steven Spielberg, in omaggio al nostro Vision Award Ben Burtt, proprio come è stata vissuta per la prima volta nel lontano 1982. Per celebrare degnamente il centenario della Columbia, la nostra retrospettiva che ha già fatto storia, mostreremo ben 26 titoli in 35 mm. Altri sei 35 mm figurano nella sezione Histoire(s) du Cinéma. L’omaggio a Stan Brakhage, si compone di ben otto titoli tutti presentati nel loro formato originale in 16 mm (e non dimentichiamo che persino un Pardino di Domani sarà proiettato in pellicola!). Tutto questo a dimostrazione di come, qui a Locarno, il nostro viaggio nel futuro del cinema non prescinda mai dalle cose belle e importanti del suo passato.

Buon cinema, e come sempre, ci vediamo in Piazza Grande!

15:30 OPENING CONCERT Palexpo (FEVI) THE CROWD by King Vidor 101’ | o.v. Silent, English intertitles s.t. Italian inter titles With live accompaniment by the Orchestra della Svizzera italiana (OSI)

14:00 GranRex THE LADY WITH THE TORCH RETROSPETTIVA COLUMBIA PICTURES

MY SISTER EILEEN by Richard Quine 108’ | o.v. English

17:00 GranRex TOGETHER AGAIN by Charles Vidor 100’ | o.v. English

19:30 GranRex CRAIG'S WIFE by Dorothy Arzner 74’ o.v. English

22:00 GranRex PICNIC by Joshua Logan 115’ o.v. English

21:30 PIAZZA GRANDE OPENING FILM LE DÉLUGE by Gianluca Jodice 101’ | o.v. French | s.t. German, English Starring Mélanie Laurent

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Christopher Small

LEAD EDITOR: Leonardo Goi

DEPUTY EDITORS: Hugo Emmerzael, Maria Giovanna Vagenas, Keva York

STAFF WRITERS: Laurine Chiarini, Savina Petkova

CONTRIBUTORS: Mathilde Henrot, Christina Newland, Julia Scrive-Loyer

TRANSLATORS: Tessa Cattaneo, Anna Rusconi

BRAND, EDITORIAL & MEDIA: Oliver Osborne

DESIGN: Joshua Althaus, Nadine Curanz, Alex Furgiuele

PHOTOGRAPHERS: Elia Bianchi, Julie Mucchiut, Ti-Press

COVER PHOTO: Davide Padovan

PARTNERSHIPS: Marco Cantergiani, Laura Heggemann, Nicolò Martire, Fabienne Merlet

CROSSWORD DESIGNER: Nicolás Henriquez

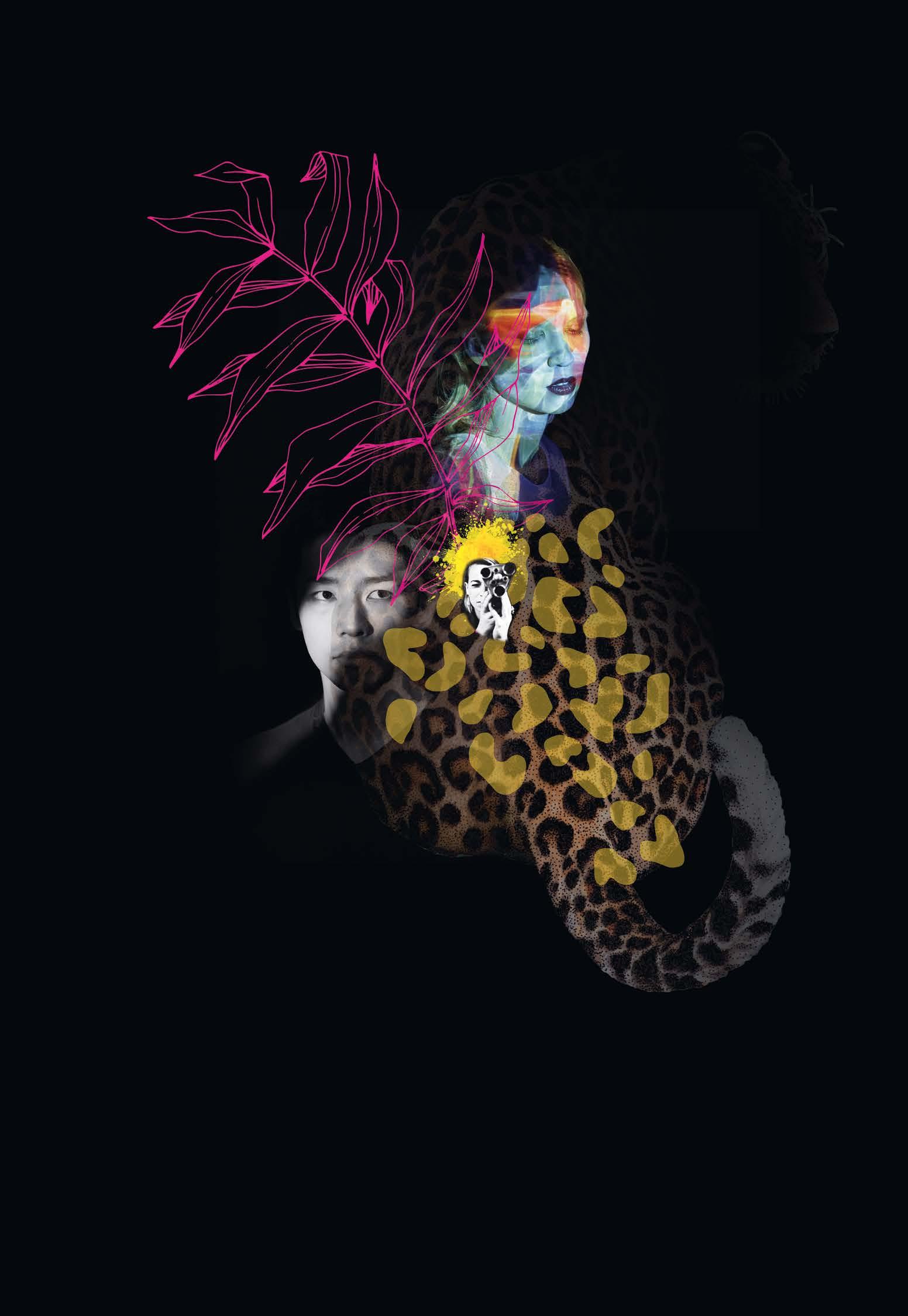

Joint recipients of the Davide Campari Excellence Award Mélanie Laurent and Guillaume Canet share insights from their acting and directing careers, lessons learned, and the joys of working together in the Festival’s opening film, Le Déluge.

by Savina Petkova

It’s easy to spot what Mélanie Laurent and Guillaume Canet, two French actor-turned-directors of the same generation, have in common. Laurent got cast, age 14, by Gérard Depardieu in The Bridge (1999) and has since starred in titles like Beginners (2011), Enemy (2013), and of course, Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (2009). Canet made his debut in 1997 and earned his first César nomination two years later. He then went on to star in Danny Boyle’s The Beach (2000) and, two years later, he directed his first feature, Whatever You Say ( Mon Idole , 2002). Since then, Canet has made eight features, the latest being Asterix & Obelix: The Middle Kingdom (2023).

Similarly, Laurent has experimented with out-of-the-box genres with coming-of-age stories (Respire, 2014), supernatural thrillers (The Mad Women’s Ball, 2021), and the Netflix action-comedy Wingwomen (Voleuses, 2023). Both filmmakers switch fluidly between French and English-language roles and scripts, and Locarno Film Festival’s Davide Campari Excellence Award celebrates the shared trajectories as much as their individual creative path.

But the prospect of success was never a given, say both Laurent and Canet, as they speak candidly about gaining artistic confidence through a long learning process. Le Déluge, the Festival’s opening film showing tonight on the Piazza Grande, is the third collaboration for the French filmmakers (after Voyage d’affaires in 2008 and Christian Carion’s Mon Garçon in 2017), but, in their own words, it presented another opportunity to connect over shared aspirations and the desire to keep working with increasing amounts of gratitude and passion.

Savina Petkova: You’re both accomplished actors and directors, recognized for your filmmaking work – now also with the Davide Campari Excellence Award here in Locarno – but if we go back to the beginning for each of you, what moment would you like to single out as formative?

Mélanie Laurent: I was 14 when I stepped onto a film set for the first time [in the romantic drama Un pont entre deux rives – The Bridge, directed by Gérard Depardieu and Frédéric Auburtin]. I remember being really nervous. Actually, when I saw the finished movie, I realized my voice in it sounds different, so shy and low, probably because I was too nervous! [Laughs] I was very lucky though, everybody was extremely nice and that helped with my confidence. I had a really amazing first experience as an actor, but I don’t think at that point I had considered directing as a possibility. It took me a little bit more, both time and courage.

Guillaume Canet: Perhaps it was when I won the most important prize that I’ve received – the César for Best Director [for Ne le dis à personne – Tell No One, in 2006]. I was touched and honored, and it gave me confidence to continue. Frankly, I’m someone who is not that confident in myself, you know, and I often have doubts about what I’m doing, what I should be doing, my choices, everything, and so it’s always reassuring to receive a major prize to help boost my confidence in that way.

SP: I get the feeling that you are both quite honest, and also in your work as directors and writers. How do you, as filmmakers, see the relationship between cinema and reality, or life?

GC: I place a lot of importance on sincerity, reality, and honesty – I’m someone who’s honest and straightforward in life and strives – as much as I can – to be as sincere and honest as possible while making a film, both as an actor and as a director. I, like all viewers, want to believe in the things I see on screen. Drawing from reality is very important, as well as being true to what you find.

ML: When I direct, I talk a great deal with my actors and technicians. I think that kind of dialogue is one of the keys to happiness! You have to make everything clear for all the amazing people you’re working with; they know their jobs, but you don’t want them to feel adrift or like they need to be guessing what to do next. When your ideas are really clear for everybody, then those people are free to do their best work. I also keeping the door wide open to improvisation, either with the actors or with the mise-èn-scene, because I love to follow my instinct on set, and to film it as I feel it should be filmed in the moment. Usually everything I’m feeling ends up in the movie at the end [laughs]. This is not a selfish job. Of course, there are selfish directors, but every time I was on the set of someone who didn’t communicate well, we would all, as actors, feel completely useless. That’s the worst feeling ever. You don’t know what to do with yourself, nor how to make yourself useful. In my mind, that’s about as far away from passion as one can get.

SP: Do you feel like you still have to negotiate the roles of actor and director within yourselves or in the perception of the public?

ML: ‘No, it was never a battle or even a contradiction for me, probably because I started acting at 14 and directed for the first time at 24. I had already worked [in the industry] for 10 years, so I guess my passion for directing had time to grow. In the meantime, I was observing everybody each time I was on set and absorbing it all. Having had the amazing chance of working with really great directors all around the world at a relatively young age gave me that strength and that crazy courage to just say: “I’ll do it!” But yes, I think I needed those 10 years. Once I started directing, it felt very normal and a logical progression for me to just extend that passion that I already had for cinema, to stand behind the camera and make use of it from that position.

GC: Frankly, I don’t really know how people label me and whether there is still an actor-director divide. I’m fortunate to have had local recognition within France as a director, as I mentioned already, but I sometimes wonder whether people really see me as an actor, and a good actor, too. Honestly, sometimes I feel like I’m more self-aware as an actor than as a director. I wouldn’t say I have doubts about my acting or anything like that – I trust myself and I like my work – but I can’t help but feel like people are only paying attention to me as a director and less so as an actor.

SP: Both of your careers in film began with acting, so it’s only natural for us to speak now about the transformations it entails. Guillaume, what’s the role of physicality in performance for you, between, for example, slimming down to embody the fragility of Maurice in IntheName of MyDaughter (L’homme qu’on aimaittrop, 2014) by André Téchiné, and the make-up and prosthetics in Le Déluge, the Locarno77 opening film in which you play King Louis XVI?

GC: Generally, I find the physicality of the characters very important. Most of the time, I like to compare them with animals and to imagine what kind of animal they would be; that helps you to think about the way that your character thinks, the way they move. I also like to observe the people around me and compare my character to people from real life, trying to guess what kind of person they would be. If there are some people I know personally who come close to what I imagine for the role I’m playing, I might take something from them as inspiration: the way they look, talk, or walk.

SP: I want to ask Mélanie the same question, since your role as Marie Antoinette in Le Déluge is, on the contrary, less exteriorized and more focused on her inner emotional life. With that in mind, how do you make the switch between registers and how, in your mind, do you approach comedy and drama differently?

ML: What can I say, France is a special country [when it comes to genre]… [laughs] We don’t often make anything out of the [genre] box. But then I directed [and starred in] a

movie called Wingwomen for Netflix, which was a first in many ways. For the first time, we had money and we could do something special, instead of a pure action film, comedy, or a drama. I think the craziness of that film helped me to pursue new things and to realize it’s fine to do something out of the box. The only thing that matters to me is the relationship between the characters and what they are going through collectively and individually. When you follow them and it’s dramatic, it’s a drama; when it’s funny, it’s a comedy, when there’s action, it’s an action movie. But there is no comedy without drama, if you want to make a film about human beings. People are so complex, and a good film should reflect that.

GC: Well, probably it’s not that strange for me or difficult to switch between registers. Yes, the energy is different: when you play a character in a comedy, they don’t often have the same reasoning and the same inner workings. A character’s reasons are a very important factor that distinguishes comedy from drama. Also, the way you express things in a drama is different, as there is a tendency to do more on the inside. I quite like that as an actor; I am able to switch from one job to another, you know?

SP: Before Le Déluge, you worked together in the short film The Business Trip (Voyage d’affaires) in 2008 and Christian Carion’s MySon(MonGarçon) in 2017. What’s your collaboration like, as I imagine, based on this conversation and from watching your films, that you may have a similar sensibility and shared approach?

GC: Mélanie is a really talented actor and director. I think we have a lot in common and in a way, I feel like she’s like me – a chronic workaholic. [Laughs] I see myself in her, in how much she works and keeps busy. At the same time, she’s capable of working very fast. It was great to be able to see each other before the shooting of Le Déluge, and we realized very quickly what it was that we wanted from this or that scene, and what we didn’t want. In every sense, she has always been very respectful and very kind to me. It was funny when she saw me in full make-up and costume for the first time [as Louis XVI] – she was visibly surprised [laughs]. It was nice to see her reaction because it felt like a certain kind of approval, as if we were doing the transformation into these parts right. When you change your face and look so much for a part, it can become scary once you start to believe that it might not work out. When you see an actor like Mélanie, somebody who you respect so much, instinctively believing in your character already, it helps a lot with that confidence I mentioned before!

ML: Yes, I was definitely shocked to see him transformed; it was so amazing and believable right from the get-go! If I remember correctly, there was another scene –perhaps the first one we shot together – of the day the King and the Queen arrive at the Tour du Temple. Guillaume improvised by taking a small rock off the ground, toyed with it, and putting it in his pocket. I was supposed to stand there and be emotionally cold, keeping my distance, but I remember, upon seeing him do that, just

wanting to take him and hold in my arms! [laughs] He brought so many little details to life, like all great actors do, and seeing that in action, as always, was impressive.

SP: You’re sharing the Locarno Film Festival’s Davide Campari Excellence Award and your careers also share some common trajectories. Is there anything you have particularly bonded over, professionally?

ML: It’s always very interesting to act alongside someone who is also a director, because we share what is an often complicated position. It’s a mix of letting the director do their work – we’re there to act, not to direct – and also of being there for them, if they need our input in any way. In Le Déluge, we had those two amazing characters that put us in a very serious state of mind and even when we had intense days and big scenes to shoot, it was always wonderful to draw from that. Most of all, I was amazed by the power of Guillaume manifesting a deep inner life in emotional scenes, by his open and effortless access to emotions, which he made look so simple! We did a lot of takes, over and over again, but he could keep up the same intensity, which in turn gave me so much strength to do the same. It felt like we were walking together, hand in hand, through the most challenging scenes.

GC: Also, it’s always fun to talk about the way we are always busy and working on different things. You know, I was joking around with her on set – she had just finished a movie – and while we were shooting, she was writing and preparing another film at the same time. Whenever I made a joke about that, she would turn it back on me, because of course I was also working on another film at the same time! We relate to one another because of that, and for sure I feel very close to Mélanie in that regard. We’re always working on various new projects even when we’re working together on something.

SP: And last, but not least: what does Locarno Film Festival symbolize for each of you and how do you feel about the event tonight at the Piazza Grande?

ML: It’s nicer to receive an award like this in tandem, no? And when I hear “Locarno”, I think of that huge screen and the big crowd at Piazza Grande, so I’m very excited to be in the middle of that! It’s the best celebration of cinema.’ Also, that vintage way of watching movies outside and feeling like you’re absorbed in a grand fantasy: it’s summer and you’re watching a big movie on a big screen with so many people at the same time. Especially in a period when going to theaters it’s still sort of a problem for a lot of people, and when we’re all fighting to keep making movies that will screen to large audiences in cinemas… It’s an important fight we need to keep on fighting. So, tonight is going to be very moving, I’m sure of it.

GC: I second that. I mean, I’ve been hearing about this festival for as long as I can remember and I’ll be very happy to finally see it for myself. I can’t wait to be there [on the Piazza Grande] and I just hope the weather will hold up, because I’ve heard stories about the Locarno storms [laughs]. Fingers crossed that our screening will be spared!

Read more about Le Déluge on page 12.

Like all viewers, I want to believe in the things I see on screen.

Drawing from reality is very important, as well as being true to what you find.

“Non si tratta di un film con la musica, ma di uno spettacolo totale”

Il direttore d’orchestra Philippe Béran ci parla del suo lavoro per La Folla (proiettato al Festival con il titolo The Crowd), lo straordinario film muto di King Vidor che l’Orchestra della Svizzera italiana accompagnerà dal vivo oggi al Palexpo (FEVI). L’evento è reso possibile grazie al sostegno di Fondazione Fidinam, AOSI, Leopard Club e eine kulturelle Stiftung.

di Leonardo Goi

Èl’appuntamento più emozionante del Festival, e grazie al sodalizio tra Locarno e l’OSI, si rinnova ogni anno. Diretta da Philippe Béran, l’Orchestra della Svizzera italiana tornerà questa sera ad accompagnare dal vivo un classico del cinema muto. Dopo Il Pensionante (The Lodger, 1927) di Alfred Hitchcock, di cui Béran aveva diretto la musica per il Festival l’anno scorso, tocca a La Folla di King Vidor, film del 1928 che a quasi cent’anni dalla sua uscita colpisce ancora per la sua critica all’idea dell’America come terra delle opportunità. Ma cosa vuol dire esattamente accompagnare un film muto? Come ci si prepara, specie quando la partitura è un testo di 650 pagine scritto da un mostro sacro tra i compositori per il cinema come Carl Davis? Alla vigilia del Festival, Béran ci parla della sua arte, e di cosa significa ridare vita a un film con la musica.

Leonardo Goi: Volevo iniziare questa nostra chiacchierata parlando del suo battesimo con il cinema – e con la musica per il cinema. Si ricorda il primo film che le ha fatto capire l’importanza della colonna sonora e mostrato come la musica potesse dialogare con le immagini, e amplificarne la forza?

Philippe Béran: Oh, facile: sono nato nel 1962, e ancora ricordo la prima volta che ho visto Il Libro della Giungla (The Jungle Book), di Walt Disney, al cinema. Avrò avuto sette anni, e fu un’esperienza incredibile – non solo perché la colonna sonora mi piacque moltissimo, ma perché tutt’a un tratto mi accorsi di come film e musica sembravano esistere in simbiosi, e di quanto questa fusione fosse qualcosa di incredibile.

LG: Com’è arrivato al cinema muto? Mi piacerebbe capire quando e come se ne è innamorato.

PB: Non si tratta di un amore per il cinema muto nello specifico ma per il cinema in generale. Il primo cine-concerto a cui ho lavorato fu nel 1997, e a quell’epoca ero davvero tra i pochissimi direttori d’orchestra che si prestavano a questo tipo di produzioni. Poi, trasferitomi all’Opera di Bordeaux, ne ho fatti moltissimi altri— soprattutto per i film di Chaplin, che credo di aver accompagnato quasi tutti. E poi ancora quando ho iniziato a lavorare con l’Orchestra della Svizzera Romanda, a Ginevra, e con tantissime altre orchestre. Alla fine degli anni Novanta i direttori che lavorassero a spettacoli del genere si contavano sulle dita di una mano; adesso le cose sono cambiate, e il numero è cresciuto… ma non di troppo. Sto lavorando proprio ora alla partitura di La Folla e le posso assicurare che si tratta di un lavoro enorme, che richiede una grande preparazione personale. Non dobbiamo soltanto conoscere alla perfezione la partitura che andremo a dirigere – e quella di La Folla è un’opera di 650 pagine! – dobbiamo anche sapere a memoria il film, ogni dettaglio infinitesimale di ciascuna sua scena. E poi, e questo è il compito più difficile, dobbiamo far combaciare la musica con le immagini. Si tratta davvero di un lavoro estenuante, ma mi piace moltissimo. Mi piace l’idea di poter essere preciso con la musica, con la pellicola… E la gente questa sincronia l’apprezza: ogni anno a Locarno le nostre proiezioni vengono viste da 2500, 3000 persone.

LG: Mi potrebbe parlare della sua collaborazione con il Festival di Locarno? Com’è nata?

PB: La mia relazione con il festival nasce dalla partnership tra Locarno e l’Orchestra della Svizzera italiana, che dirigo in questa e altre occasioni; il festival e l’OSI sono due tra le più grandi istituzioni artistiche del Ticino. Ormai per me lavorarci assieme è quasi normale. La prima volta che il festival reclutò l’OSI per un cine-concerto fu dieci anni fa, e da allora ho lavorato per Locarno a tantissimi progetti e produzioni – non soltanto cine-concerti. In quanto al film, La Folla, quello è stato scelto dal direttore artistico, Giona Nazzaro, che ha curato il programma anche negli anni precedenti. Lo scorso anno avevamo accompagnato Il Pensionante, di Alfred Hitchcock, e quello precedente Giglio Infranto (Broken Blossoms, 1919), di David Griffith… Ormai dopo tutti questi anni ho accumulato un certo repertorio, ma è sempre un piacere vederlo crescere e aggiungervi nuovi titoli.

LG: So che la partitura che utilizzerete è quella composta da Carl Davis, che lui stesso aveva diretto per una proiezione di La Folla al Pordenone Silent Film Festival di qualche anno fa.

PB: Esatto. Francamente non so se esista una partitura originale per La Folla; so che Davis scrisse la sua nel 1981. 650 pagine! E Davis era un vero specialista, una sorta di mostro sacro nel nostro campo – compose qualcosa come cento partiture per film, e questa che fece per La Folla è semplicemente fantastica. Il film uscì nel 1928, giusto un anno prima del collasso di Wall Street e della Grande Depressione in America. Siamo nel bel mezzo di quello che in francese chiamiamo les années folles, gli anni ruggenti, anni del delirio e degli eccessi, nonché l’epoca d’oro del jazz. Quello che rende la partitura di Davis magnifica è il fatto che è scritta sia per una grande orchestra sinfonica sia per una jazz band, perché è piena di pezzi composti per dieci, dodici musicisti all’interno dell’orchestra stessa. E c’è questa riuscitissima alternanza tra le parti per l’orchestra sinfonica e quelle per la jazz band.

LG: Un’alternanza che rispecchia un po’ la porosità della scena musicale dell’epoca. Se non erro fu proprio in quegli anni che uscirono pezzi rivoluzionari come la Rapsodia in blu, di George Gershwin, dove musica classica e jazz si fondono l’una con l’altro.

PB: Esattamente: era un clima molto fertile da quel punto di vista. Erano gli anni in cui il jazz iniziava a entrare nella musica classica, gli anni in cui maestri europei del calibro di Maurice Ravel, a seguito dei loro viaggi negli Stati Uniti, iniziavano a incorporare il jazz nella loro musica…

LG: E quanta libertà può prendersi al cospetto di una partitura come quella di Davis? Mi domando quanto fedele debba essere il direttore alla musica che dirige…

PB: Il problema è che di partiture ne esiste solo una – la sua – e che non è mai stata pubblicata. Ne esiste solo una copia, manoscritta, con la quale sto lavorando proprio in questo momento! [ride] Ma non è la prima composizione di Davis su cui lavoro. Ne ho già dirette tantissime; lo conosco molto bene, come conosco bene il suo stile. E quest’opera è davvero formidabile, proprio perché è in grado di ricreare tutte queste musiche e questi suoni di quegli anni pazzi.

LG: Le confesso che il suo lavoro è per me tanto affascinante quanto sconosciuto, e le sarei davvero grato se mi potesse parlare di alcuni degli aspetti più pratici. Cosa vuol dire esattamente accompagnare un film muto? Come ci si prepara?

PB: Come facciamo? Da che parte si comincia? [ride] Guardi, la prima cosa da tenere a mente è che La Folla è relativamente molto lungo – si tratta di una pellicola di un’ora, quarantatré minuti e dieci secondi. E l’orchestra suona durante tutta la durata del film, senza un attimo di tregua. Le lascio immaginare quindi quanto complesso e difficile sia suonare un pezzo così lungo, piccola o grande che sia l’orchestra. In quanto alla mia preparazione, per mia fortuna ho con me una copia del film con la musica di Carl Davis come colonna sonora già perfettamente sincronizzata, cosa che mi permette di osservare tutti gli elementi di cui ho bisogno, e come la musica venga abbinata a questa o quella scena. È tutto molto più facile, e poi naturalmente ci sono gli appunti che prendo sulla partitura. Solo dopo aver visto il film più e più volte comincio con la musica – analizzo tutte le 650 pagine per essere sicuro di non aver perso niente, e poi inizio a lavorare alla sincronizzazione. Ci sono 48 scene in La Folla, vale a dire 48 composizioni diverse; il mio compito a quel punto diventa calcolare alla perfezione come la musica entrerà a far parte di ogni scena – quando inizierà e quando finirà. E solo quando sono pronto al 200% posso passare all’orchestra vera e propria. È un grandissimo e difficilissimo lavoro; quasi tutti i buoni direttori d’orchestra possono dirigere per un’ora e quarantatré minuti, ma essere in grado di farlo in perfetta sincronia con un film è tutta un’altra sfida.

LG: E come raggiunge questa sincronia?

PB: Imparando la musica e il film a memoria, per prima cosa. Così facendo so esattamente tutti i tempi della partitura – e ce ne sono tantissimi, in La Folla. In altre parole, so come e quando passare da una scena all’altra, e aggiustare il ritmo al film. È un lavoro che richiede talmente tanta precisione che sembra quasi da computer, a dimostrazione della grandezza di Davis. Era veramente un maestro in questo: gli bastava vedere un film per capire che tipo di accompagnamento avrebbe funzionato meglio. Ed è questo il potere della musica, quello di cui si accorge chiunque assista a uno spettacolo come il nostro, un cine-concerto. La musica esiste in dialogo con le immagini, e le rafforza, così come le immagini rafforzano la musica. Anche in questo Carl Davis si è dimostrato sempre un vero compositore di stampo classico, al contrario della maggior parte di chi compone oggi, il cui lavoro viene in buona parte svolto da un computer. Era un compositore in stile Mozart o Beethoven, in grado di cambiare radicalmente la nostra relazione con le immagini a seconda della musica che proponeva come accompagnamento.

LG: Com’è cambiata la sua relazione con LaFollada quando ha iniziato a lavorarci?

PB: Devo ammettere che ho due tipi di relazione con il film. Da un lato c’è la mia relazione più emotiva, da semplice spettatore, forse la più importante. E La Folla riesce sempre ad emozionarmi – ho pianto più volte guardandolo, ci sono delle scene che sono davvero terribili. Dall’altro lato c’è un rapporto molto più razionale con il film, quello di chi deve abbinare la musica alle scene, e pensa alla pellicola in quei termini: come passare da una scena all’altra. Questa è una parte molto più cerebrale e analitica; la parte più professionale, se vuole. Una volta che entro in quest’ottica, ecco che non penso più al film in termini di emozioni, o di messaggio, ma di suoni che devono integrarsi alle immagini.

LG: Come se diventasse una sorta di architetto del film.

PB: Si, in un certo senso. O se preferisce, da direttore, divento il respiro del film. A essere sincero, condurre un’orchestra sinfonica è di gran lunga più facile che dirigerla per un cine-concerto – mi sento sempre molto, molto più libero in quell’altro contesto! La grande sfida quando invece dirigo musica per film è proprio quella di godere di quella stessa libertà, pur con tutte le limitazioni che mi vengono imposte dall’esercizio. Non posso essere né troppo veloce né troppo lento, ad esempio, perché altrimenti musica e immagini si disunirebbero. Ma trovo la musica composta per film molto più immaginativa e creativa di quella sinfonica – con questo non voglio certo dire che questa non mi piaccia, anzi! Stiamo semplicemente parlando di due modi diversi di essere artista: da una parte direttore d’orchestra sinfonica e dall’altra direttore d’orchestra per un cine-concerto. Il mio compito, in quest’ultima veste, è quello di dare il respiro musicale al film. E francamente penso che questo tipo di professione abbia un bel futuro, perché… lei ci ha già sentito suonare gli anni passati a Locarno?

LG: No, questa sarà la mia prima volta.

PB: E allora presto capirà che cosa intendo. È una cosa davvero molto emozionante, e sempre diversa. Non si tratta di un film con la musica, ma di uno spettacolo totale. C’è una simbiosi tra musica e film che rende entrambi ancora più straordinari, e la musica dal vivo aggiunge un’altra dimensione a quello che passa sullo schermo. Vedrà, è qualcosa di magico.

È questo il potere della musica, quello di cui si accorge chiunque assista a uno spettacolo come il nostro, un cine-concerto. La musica esiste in dialogo con le immagini, e le rafforza, così come le immagini rafforzano la musica.

The Crowd verrà proiettato quest’oggi alle 15:30 al Palexpo (FEVI)

Cinema is not a competition, but innovation and excellence in any field deserves recognition.

The main awards at Locarno – from the coveted Pardo d’Oro to the Pardo Verde, First Feature, and Pardino d’Oro – are bestowed by the Festival’s juries, their value enriched by the expertise of each member. Pardo asked this year’s crop of jurors to share with us their answers to two questions that go to the heart of their cinephilia:

What’s the first film you remember falling in love with, and why?

What is it that you look for when watching a film?

as a young filmmaker were Jane Campion’s Sweetie (1989) and Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943). Deren’s film taught me how to create a surrealist world merely by using the technique of editing and thus reinventing the reality of time and place. Deren connects places through editing that could never be connected otherwise and makes us believe the unbelievable. And she edits repetitions in time that remind us of our perception in dreams. Sweetie impressed me with its visual beauty and artistic style. And it meant a lot to my generation of female filmmakers, as Campion had her first feature film in Competition at Cannes and thus proved that women can make successful films. It was breaking news back then.

I can enjoy films for very different reasons – sometimes I like a character who is unusual, or I like the visual style or the consciously made decisions in cinematography, or I enjoy the originality of a story. In general, I would say I like to be challenged and irritated by films that leave the main road of filmmaking by showing life from an unusual perspective. This can lead to a deeper emotion than what is created simply through empathy with the lead character. This other emotion comes from an understanding of the human condition and it is the reason that I watch and make films.

CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE

There are so many films I’ve fallen in love with, but I’m going to mention two that bring me back to my family and childhood: Vittorio De Sica’s Miracle in Milan (Miracolo a Milano, 1951) and then of course Bicycle Thieves (Ladri di Biciclette, 1948). Honestly, I’d say all films from that period, of which I saw so many when I was little!

was behind the camera. I watched the film astounded by how we were never shown the so-called “evil dead”. Looking back, I believe this was when and how I fell in love with visual storytelling.

I look for two main things: imagination and courage. How much imagination flows through the film from scene to scene. From the directing to the dialogue, performances, production design, and cinematography, I want to see inventiveness, style, and vision. And courage, too, because I need to see and feel like the filmmaker is putting it all on the line. I don’t have to agree with their point of view, but I want to see and feel one the filmmaker is willing to bet on and commit to 1000 percent.

PRODUCER (BELGIUM)

CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE

Whoa, I have asked myself this question over and over. I can’t remember clearly; I recall the emotions I shared with an audience when I was a kid going to see Disney movies with my sisters in the long-gone ABC Cinema in Brussels. What has always fascinated me is the collective emotional journey one shares with strangers. But if I had to name two out of hundreds, I’d probably pick Robert Mulli-

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) and Sydney Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (1962), which I first saw when I was a teenager and could go and watch films alone at the Cinémathèque in Brussels. I remember the shock, my rage and tears, leaving the theater full of energy. It was then that I made a very naïve decision: to change the world...

I love to forget myself in someone else’s story, to lose the notion of time, space, place. I am eager to discover, to try and quench my curiosity. I am a patient spectator, ready to be transported anywhere emotionally and be surprised by a story’s journey.

I like to embark on a journey that begins at minute zero and finishes when the end credits roll; I like to escape everyday life and venture deep into the story I’m watching. I see a film in its totality. And I hope to establish a good dialogue with it, both intellectually and emotionally, so that it can leave me with a thought, a feeling, an emotion.

FILMMAKER AND ACTRESS (FRANCE, PALESTINE, ALGERIA)

CONCORSO CINEASTI DEL PRESENTE

It was The Night of the Hunter (1955), an American film noir directed by Charles Laughton and starring Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, and Lillian Gish. My father showed it to me when I was very young, and it impressed me with its beauty, poetry, the multiplicity of its characters, and its tension. Few films are as haunting as this timeless masterpiece.

FILMMAKER AND ACTOR (USA) CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE

When I saw Sergio Leone’s The Good The Bad and The Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, 1966) I understood for the first time what subjectivity was, and how a director could orchestrate aesthetic choices into a cohesive whole: photography, casting, locations, production design, music, sound, and costumes could all harmonize (or clash in interesting ways) to present not only a compelling narrative but a worldview as well.

I don’t look for anything specific, but I want to be moved, struck in the heart, immersed in a singular universe, a unique tale, a specific atmosphere. This usually happens when a film is made with authenticity.

I want to know that deliberate choices have been made in every respect – from how a movie sounds, looks, is cast, costumed, and designed – and that such determinations succeed in ways always subservient to the narrative. To me this is what directing is all about. As for story, a film must cohere, surprise, and pull off an ending that in retrospect feels as though it was inevitable even though I might never have suspected it would occur.

FILM CRITIC (FRANCE) CONCORSO CINEASTI DEL PRESENTE

FILMMAKER (INDIA)

CONCORSO INTERNAZIONALE

The first film that left me completely mesmerized was Věra Chitylová’s Daisies (Sedmikrásky, 1966). It was the first time I saw a film that could be so joyous, so playful with its cinematic language and still extremely political.

I always like films with which I find an emotional connection. These feelings lead you to something vulnerable, perhaps even truthful. I also look for films that challenge cinematic forms and make mistakes. It allows for a more open viewing process.

I fell in love with cinema very early on, at the start of the ’60s, because it showed me a world other than my own, other people who were my fellow human beings. It was through cinema, cinema alone, all cinema, that I felt the extent of the world. The film that made me fall in love with the medium, by showing me what it was capable of things beyond what I had imagined at the time, was Carl Theodore Dreyer’s Ordet (1955).

FILMMAKER (NIGERIA) CONCORSO CINEASTI DEL PRESENTE

As far as I can remember, Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead (1981) was the first film that came into my consciousness. I first watched it as a very young child, when I had no business seeing it; my elder siblings had built up this hype around how scary it was. I just remember the opening scene with the long POV shot roving through the woods and waiting to see what

When I watch a film, I always (politely) ask it two questions: What does it expect from me as a spectator? What does it expect from cinema itself? I’m often reminded of JeanLuc Godard’s austere but accurate phrase: “All filmmakers will tell you that, in making a film, they love cinema, but some only need to see their film to understand that cinema doesn’t love them.”

SCRIPTWRITER, DIRECTOR, AND PROGRAMMER (ITALY)

PARDI DI DOMANI

It was the first Pasolini film I ever saw, The GospelAccordingtoSt.Matthew (IlVangelo secondo Matteo, 1964); I discovered both a great filmmaker and a man of immense depth. And, for the first time, I felt a Christ that I could truly love unconditionally. It’s a film that I’ve seen at least four times, maybe five, like Blade Runner (1982) or Apocalypse Now (1979), and that I could watch again and again – like every other mythical film... but this was the first one.

Frankly, I’m not in the position to “look for something” when I watch a new film, otherwise I will surely be disappointed. I’m more concerned with understanding the director’s gesture. Sometimes it may seem accomplished: the relationship between subject and form fits perfectly; other times it doesn’t. And among all these “perfect imperfections”, I try to feel and understand the meaning, rhythm, force, formal proposition, performances, intuition, atmosphere, and the maturity of the work...

PRODUCER (FRANCE) PARDI DI DOMANI

It took me time to fall in love with a film, maybe because those usually shown to kids were not meeting my sensitivity and expectations.

I guess the first time I really felt hooked and enchanted was when I watched François Truffaut’s series of films centered on the mythical Antoine Doinel. For the first time, I was taken by a character’s trajectory, from childhood to maturity, and taking place in a Paris that was different from the one I was living in but still recognizable. I watched the four films hundreds of times.

I am more and more sensitive to the sound in films. Generally speaking, I guess what takes me first is what I’d call ‘the charm’, which depends on plenty of factors that are unique to each film, then the storyline, and finally the characters. These characters can be either a natural element, an object, or a human being – but I definitely need something or someone to relate to!

I want a film to take me away somewhere, and to allow me to connect with the heart and humanism of the filmmakers. If a film feels honest I also welcome being disturbed or shaken by it. I do appreciate integrity, when a film is true to itself and is not out to please... The best film experiences are the ones that change you in some way, even if just a little bit.

MAKE-UP DESIGNER (SWITZERLAND, ITALY) FIRST FEATURE

The first time I fell in love was with Ivan’s Childhood (Ivanovo detstvo, 1962) by Andrei Tarkovsky, and then with Andrei Rublev (AndreyRublyov, 1966). Just poetry. And passion.

I want to be dragged away, elsewhere. Only in a movie theater am I not disturbed by reality.

MANAGER (SWITZERLAND) PARDO VERDE

The first film I fell in love with is one that made me cry despite the fact that I never saw it. I was going out with some of my older friends to watch Winnetou, a new western starring Lex Barker and Pierre Brice, in my native city of Bern, Switzerland, in 1965. But I was not allowed into the cinema because the movie was restricted to 12+, and I was only going to reach that age a few weeks later. So I was left alone in front of the ticket office, crying my eyes out. Having read the book by Karl May that the film was based on, I envisaged what I was missing. And, of course, in my imagination the work grew bigger than life – the best feature film on earth. I guess I might be quite disappointed if I were to watch it now. So I better not..

DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER (MOROCCO) FIRST FEATURE

PROGRAMMER AND FILM CRITIC (FRANCE) PARDO VERDE

FILMMAKER AND CURATOR (MADAGASCAR)

PARDI DI DOMANI

The first film I remember falling in love with is Citizen Kane (1941) by Orson Welles. It holds a special place in my heart because it was the first film I ever watched in a cinema. Growing up, all the cinemas in my country were closed, so I didn’t have the chance to experience films on the big screen. That changed when I saw Citizen Kane for the first time at the Cinéma des Cinéastes in the 18th arrondissement of Paris when I was 16 and a half. The experience was unforgettable and deeply impactful.

When watching a film, I look for a compelling storyline that keeps me engaged, strong character development that allows me to connect with the characters, and visually striking cinematography that enhances the overall experience. Additionally, I appreciate a wellcrafted soundtrack that complements the mood of the film, and innovative directorial choices that bring a unique vision to life. I believe that films should capture the exceptional and challenge the audience, making them active participants rather than passive viewers. Cinema should, in some way, make the viewer uncomfortable, prompting reflection and deeper thought. All these elements combined create an immersive and emotionally impactful experience that stays with me long after the film ends.

Luis Buñuel’s TheYoungandtheDamned(Los Olvidados, 1950) for the director’s ability to treat a social realist theme/story with surrealist elements, which I later realized was his trademark.

When I watch a film, I like to be transported, one way or another, by a story that pushes me to think, feel, and question. I always seek a story with atmosphere, good acting, ideally, and good cinematic language – films that can trigger discussions and make me think… and rethink.

As a very young kid, my late father (who was a true film lover and an absolute eccentric inspiration for me) took me to see Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) in a cinema in Aix en Provence called Cézanne. It must have been the very first film I ever saw on a big screen. Despite my very young age, I vividly remember being blown away by its poetic and transfixing finale (that score!!!). Apparently when we got out of the theater, I told my father that, asan adult, I would have liked to become a scientist working with UFOs just like the man in the film... who was none other than François Truffaut, but his name obviously didn’t register back then! Little did I know both he and Spielberg would later become two of my absolute favourite directors.

ACTRESS (FINLAND) FIRST FEATURE

I remember seeing Fried Green Tomatoes (1991) in my early teens, and being completely blown away by it. The film confronted me with the challenges and blessings of womanhood, but also themes like friendship, justice, love, loyalty, loss, freedom... I fell in love with the acting, the humor, and how the story unfolded – seeing this film was empowering and I’ve watched it many times since.

As a programmer, I always rely primarily on intuition rather than any form of (film) ‘intellectualization’, for lack of a better word. I need to be transported, challenged and, pardon my French, moved (I know this is almost a taboo word these days in film criticism, but I don’t care), so I’m a rather simple spectator, ha ha ha! But I hate nothing more than films with a very clear structure that tell me a story from A to Z, which has gone through too many labs. Those end up feeling too polished for my liking. I like accidents, surprises, aesthetical hybridization; flamboyant and poetic cinema is my thing! I need to sense the vital urge of a director behind the camera.

I can enjoy a good documentary as much as a fiction film. The key element of my pleasure – for me – is when directors remain true to themselves, their story, and their subject matter. Each crew has its distinct language, and that’s what makes the experience worthwhile across all departments, starting from the scenario to the acting all the way to the first screening, including the communication and marketing strategies. What pushes me away from a movie is when I feel that it’s trying to please by employing clichés or that it’s just to meet preconceived expectations instead of questioning them. Then it loses me quickly. This is, for instance, a recurring pitfall of wildlife documentaries. I feel manipulated quite frequently, especially by conventional editing and soundtracks.

ARTIST, WRITER, AND DIRECTOR (SWITZERLAND, RWANDA) PARDO VERDE

It was Souleymane Cissé’s Yeelen(1987). I remember that the film punched me in the guts and moved me at the same time; isn’t that falling in love? I had not seen anything like it before, it was a different type of rhythm and narrative, and now I was yearning for more. Yeelen connected me with life’s energy, dreams, ancestral times and circularity; it resonated with a part of me.

I look for elation, for substance, for something that penetrates, that pierces my consciousness and my emotions. And these days, I also look for something that helps me re enchant the world.

Did you know that before the Pardo d’Oro became the Festival’s

And that multiple winners were

the

Locarno used to hand

across the ‘50s and ‘60s? Here’s a list of all the films that made the Festival’s history. Tick those you’ve seen!

Qualunque sia la formula che vi fa battere il cuore, noi sosteniamo chiunque desideri una consulenza previdenziale e finanziaria personalizzata.

Per una vita in piena libertà di scelta.

Il regista Gianluca Jodice parla del film di apertura di Locarno77

Intervista di Mathilde Henrot SELECTION COMMITTEE

Ambientato nel 1792, Le Déluge immortala Luigi XVI, sua moglie Maria Antonietta e i loro figli nella prigione della Tour du Temple fin dalla scena iniziale. Sequestrati in una sala priva di mobili, i reali attendono il loro imminente processo, ben sapendo che perderanno tutto. Guillaume Canet incarna il Re con tranquilla gravitas e pesanti protesi, mentre Mélanie Laurent è una Regina terrorizzata che rifiuta di accettare la realtà. I mesi passano, il processo si trascina, e le condizioni di vita diventano quasi insopportabili – proprio come il dolore di un ideale monarchico schiacciato. Gianluca Jodice inizia il suo dramma d’epoca Le Déluge dove altri film sullo stesso periodo storico solevano finire: con i monarchi in prigione all’alba della Rivoluzione francese. ◼ Savina Petkova

Mathilde Henrot: Può spiegare la scelta del titolo?

Gianluca Jodice: Beo di raccontare la fine dell’Ancien Régime in Francia? Vi sembrava forse che quel periodo storico avesse una certa risonanza con il contesto politico attuale?

GJ: A dire il vero, no. Resto convinto che l’unico modo per essere attuali è essere inattuali. Le risonanze sono l’humus, non devono essere inseguite o costruite troppo programmaticamente. Un’analogia con questi tempi… forse la sensazione che anche sopra le nostre teste oggi la Storia è sul punto di cambiare pagina.

MH: Ha scelto di raccontare la storia dal punto di vista dell’intimità di questa famiglia: può spiegare questa scelta di una storia (personale) che si fonde con la storia (di un Paese)?

GJ: Se non c’è privato, personale, individuo, non c’è la Storia, non la senti. Altrimenti fai un film che è la traduzione in immagini di un manualetto scolastico. Fai le figurine. Devi ricostruire e raccontare i sentimenti, i pensieri degli uomini, ovviamente storicizzati, figli di quel tempo, perchè ogni epoca ha il suo specifico modo di lottare, di amare. O di lavarsi. Poi mai come in questo caso la morte di un singolo uomo, il re, coincideva con la fine di un regime, di un’epoca intera.

MH: Nell’introduzione al film, si spiega che il film è basato sui diari di Cléry, il fedele valletto del re e l’unica persona a cui è stato permesso di stare al suo capezzale. Ha adottato quindi una visione soggettiva del clan reale? Si è mai distaccato da esso? Perché ha fatto questa scelta?

GJ: Più è importante e grande il periodo o il personaggio che racconti, più piccolo e parziale deve essere il tuo punto di vista. È una legge fisica, che spesso viene incontro alla drammaturgia. Avere un punto di vista specifico, ben perimetrato, è il modo più onesto e trasparente di guardare ai fatti, meglio, di costruire i fatti. È il modo più forte anche di far risuonare al meglio quello che escludi, quello che resta fuori campo. Se ti fai prendere dall’ansia di raccogliere ‘diplomaticamente’ tanti punti di vista differenti sei fottuto.

MH: Lei è italiano, cosa l’ha interessata di questa storia così francese?

GJ: La rivoluzione francese è l’archetipo di ogni rivoluzione. E ogni rivoluzione della modernità ha una componente edipica. E questo è molto interessante. Gli italiani sono molto edipici, non avendo mai tagliato la testa a un re. I francesi meno. Il 1789 è la nascita della contemporaneità, nel pensiero politico, filosofico, scientifico, nella vita sociale… E poi racconto un passaggio che neanche i francesi conoscono e hanno raccontato troppo bene.

MH: Dove colloca questa sua opera nel contesto dei film che hanno parlato di questo stesso momento storico così travagliato? Un altro regista italiano, Ettore Scola, ha realizzato IlMondoNuovo(LaNuitdeVarennes, 1982), interpretato da altri mostri sacri, tra cui Harvey Keitel, Marcello Mastroianni e Jean-Louis Barrault. Sembra che LeDéluge sia quasi il momento successivo?

GJ: Oltre ad alcune mediocri megaproduzioni televisive, ci sono i film di Rohmer, di Wajda, di Jacquot, della Coppola per non andare troppo indietro nel tempo… e tra i film che ho visto e/o rivisto durante la scrittura, sì, ho rivisto anche quello di Scola. Se devo essere sincero però, la direzione è sempre stata un’altra: fare un film più metafisico che storico. Dove le emozioni e il senso scaturissero più dalle scelte stilistiche e formali che da altro. I riferimenti sono stati più un certo Sokurov, il Lanthimos de La Favorita (The Favourite, 2018), e senza dubbio il meraviglioso La Morte di Luigi XIV (La mort de Louis XIV, 2016)’ di Albert Serra…

MH: Le tre parti in cui si snoda il film sono cronologiche. La prima: gli dei e il periodo della regalità. La seconda: gli uomini e il periodo della creazione della Repubblica. La terza: i morti e il periodo finale della condanna a morte.Perché questa scelta di inquadrare il film in una struttura tripartita?

GJ: Anche qui: cronologiche sì, ma più metafisiche. Mi piaceva. Mi sembravano i tre passaggi della vita di ogni uomo. Dal cielo alla caduta.

MH: Dove si sono svolte le riprese? L’arrivo della carrozza sembra indicare Versailles, con la grandezza simmetrica dei giardini, ma poi appare in lontananza la Prison du Temple.

GJ: Se si prendono le cartine e i disegni dell’epoca, prima di entrare a la Tour du Temple, che era un castello templare, medievale, si attraversava un edificio ‘nuovo’, settecentesco, dove i rivoluzionari fecero dormire la famiglia reale per i primi giorni. Successivamente salirono nelle celle della Torre del Tempio. Abbiamo girato a Torino, nella reggia di Venaria, e le celle le abbiamo ricostruite in studio a Roma sulla base delle piantine originali. Non è stato possibile girare alla Torre del Tempio a Parigi semplicemente perchè non esiste più. Dopo la morte dei reali il castello era continua meta dei nostalgici della monarchia e una bella mattina del 1808 Napoleone decise di demolirlo.

MH: C’è un certo classicismo anche nella regia: può parlarci della scelta di non inserire elementi di rottura?

GJ: Beh… non sono d’accordo. Il primo atto è classicista, diciamo così. Doveva raccontare proprio il canto del cigno del ‘700, gli echi dei fasti, della bellezza e della grandezza di Versailles… Tutto è bianco, ci sono campi lunghi, i movimenti di macchina sono sinuosi ed estetizzanti, abbiamo usato focali medie. Poi però cambia tutto! Il secondo atto è girato tutto con camera a spalla, con movimenti nervosi, con scatti e brusche frenate, con grandangoli spinti e deformanti e anche la luce si fa più buia, granulosa, sporca.

MH: L’Agnello di Dio: LXVI comprende la sua morte grazie alla Bibbia, ed è così che la accetta. Per lui la sua morte non è quella di un uomo ma quella di un dio, e non è solo un simbolo come la presenta il pubblico ministero.

GJ: Difficile dirlo. L’avrei tanto voluto capire meglio in fase di scrittura. Non ce l’ho fatta. Cioè… la domanda è: Luigi XVI la notte prima di morire aveva paura e faceva gli stessi pensierini che faremmo noi (qualora ci capitasse di sapere di dover morire il giorno dopo) oppure no? Oppure i pensieri di un uomo del 1793, del re poi (!), erano diversi? Non lo so. C’è il romanzo di Victor Hugo, L’ultimo giorno di un condannato a morte, (Le Dernier Jour d’un condamné) anche se è leggermente posteriore. Lo lessi proprio per cercare questa risposta. E i pensieri e le paure del condannato di Hugo sono le nostre. Ma vai a sapere…

7.8.2024, 21:30, Piazza Grande Opening Ceremony

EXCELLENCE AWARD DAVIDE CAMPARI to Mélanie Laurent and Guillaume Canet

| Got the chair? Go to vote! Prix du Public UBS »

“I

Simply Can’t Stop Watching Columbia Films” Pardo caught up with Retrospective curator Ehsan Khoshbakht to talk about the rationale behind the program, some of his stealth favourites, and how watching too many Three Stooges shorts almost drove him to madness.

By Christina Newland

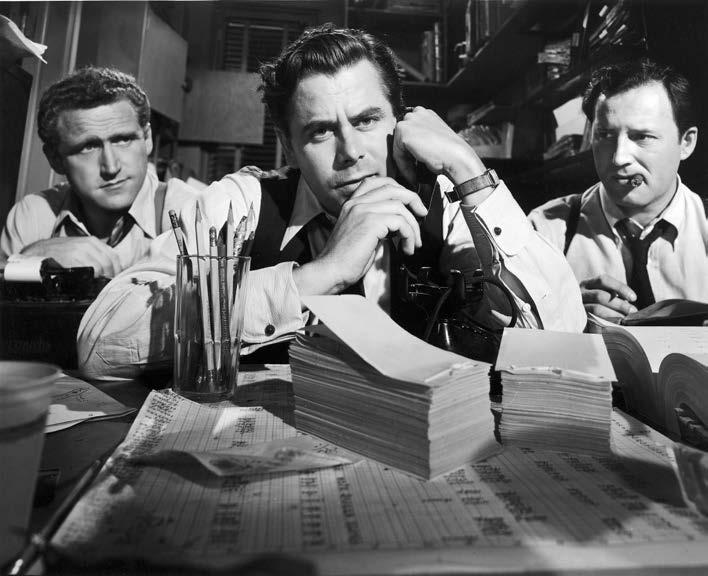

In 1924, a pugnacious businessman who grew up impoverished in a New York tenement co-founded a movie studio. That studio came to be Columbia Pictures, and that man its long-reigning mogul Harry Cohn. With humble beginnings and an economical eye for budget, Columbia had a knack for turning out ingenious motion pictures with talent on loan from other studios, from Cary Grant to Carole Lombard. Those films would become stone-cold exemplars of their genre – The Awful Truth (1937), for instance, or Twentieth Century (1934).

Programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht has dug deep into the Columbia vault to curate The Lady with the Torch: The Centenary of Columbia Pictures, the 40-film Retrospective showing here at Locarno77. Looking back at that studio’s golden age and beyond canonical titles like It Happened One Night (1934) and Gilda (1946), Khoshbakht unearthed the work of little-known B-directors and stumbled upon strange genre cycles, such as the delinquent girl flicks of the 1940s.

Christina Newland: Tell me a bit about your initial idea for the retrospective.

Ehsan Khoshbakht: The initial idea was a bit more radical – celebrating Columbia’s centenary through B-unit productions and forgotten films. No Frank Capra, no Howard Hawks screwball comedies. I gradually came to my senses. The current version of the program is a bit like the studio itself, made up of a quarter canonical classics, a quarter lesser-known films by masters (there’ll be a restored version of Gun Fury [1953] by Raoul Walsh, for instance), a quarter unseen films (Edward Dmytryk’s Under Age [1941]) and a quarter films by and about women, in front and behind the camera (Craig’s Wife, [1936]). So there will be Capra and Hawks. It is silly doing any retrospective on any subject without showing a Hawks picture.

CN: At a certain point, Columbia was well-known for screwball comedy, and then after the war for the B-noir, but of course the studio made all manner of genres. How did you approach wanting to curate films both in and outside of the genre parameters people might expect?

EK: I tried to avoid thinking of the studio output in terms of genre. Instead, I followed the directors’ trajectories. Let’s see where Lew Landers started in 1941 and what he did before calling it a day at Columbia in 1953. In between, you have 54 films. You have to find the meaning behind that man’s efforts. I must confess I was wary of getting too much into the Columbia noir, which is perhaps now the most famous and the most widely circulated of the studio’s postwar films. The reason was I wanted to focus on the underseen and the less obvious.

CN: In your research, how many films did you track down and view? And what patterns began to emerge, if any?

CN: Often, Columbia’s history is largely viewed through the prism of Harry Cohn and his personality. Were you interested in putting the focus elsewhere with this season?

EK: He was a fascinating figure. His instructions, notes, and involvement – often delivered in very crass language –shaped many of the studio’s projects. There are some independent projects in the studio that became enormously successful, but which Cohn hated since he had no say in them. He loved the control. Yet, Columbia was a freer studio compared to MGM or Twentieth Century-Fox. There was a great degree of flexibility and trust. And I think Cohn trusted the artists more than Zanuck or Selznick did. The biggest lesson I have learned, which should make auteurists very happy, is that at the end of the day, it is the director’s style – good or bad, original or imitative – that stands out at Columbia.

CN: What do you find are the biggest misconceptions about the studio and its history?

EK: Whenever somebody refers to “the genius of the system”. As I said, the directorial voices at Columbia Pictures are those heard most loud and clear, so giving all the credit to the studio doesn’t make sense. The studio provided the fertile ground upon which they worked, as well as the impeccable technicians and the improbable plots and scenarios. The rest was up to people – talented or mediocre – to make something of them. But if one looks closely at Columbia, it becomes clear that it completely differs from other studios because of the blurred line

EK: I started by printing out Columbia’s release calendar, 1929-1959, and viewing them and marking them as if a secret code to a parallel universe could be discovered. The idea was to watch a) a minimum of one release per month; and b) to identify trends, series, cycles, and go for the most representative titles belonging to that group of films. I think I have seen close to half of Columbia’s features from that period, excluding the foreign film releases, since they also distributed films like Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai, 1954). Another lifetime is needed to fully cover every Three Stooges short, even without mentioning the potential threat to one’s sanity that that entails. But even now that the program is fully assembled, I simply can’t stop watching Columbia films; I need to be committed to a rehab centre. The unpretentious and modest artistry of them simply appeals to me. Now when the characters open their mouths, I can roughly tell what the dialogue is going to be. So in a way, there is a parallel universe of Columbia Pictures and now I’m living in it. Regarding patterns in what I discovered, I can say that what actually caught my attention was the period when there was no pattern, as in the late 1950s when confusion reigned at the studio. Watching those films, you wonder, “What’s going on?” you can feel the studio was trying to hang onto anything it could before the eventual freefall due to changes in the economy of Hollywood.

between A and B films in their output, the hybridity of the genres they worked in, and the remarkable reliance on outside talents and independent productions. Experiments were allowed. Leftists and Communists were tolerated. All as long as things were kept under budget. The budget was Cohn’s eleventh Commandment.

CN: How much did the availability of films effect the selections you made?

EK: This has been the highest degree of freedom and ease of access I have so far experienced as a programmer. Sony Pictures Entertainment owns Columbia today, and the Sony/Columbia archive people are among the most respected in the cinema archive world. Grover Crisp and Rita Belda helped enormously.

CN: Talk to me about how you see women’s roles in the films you’ve chosen. What was unique in some of the depictions you chose to curate?

EK: Compared to other major studios, Columbia was the studio of women. Not only in the stories and characters, but also in the people involved in making the films. There were more women in the artistic teams and the crews than in other studios. At some point, Columbia was the only studio that had a female executive producer, Virginia Van Upp, who was also a superb writer. And there were many fine writers like Gertrude Purcell, Mary C. McCall Jr., and Fanya Foss. That aside, Columbia had some kind of girl-movie obsession going on. For almost every type of film made at other studios with men in the leading roles, Columbia would do an all-female version of it. If Warners did Wild Boys of the Road (1933), Columbia responded to it with Girls of the Road (Nick Grinde, 1940), about a gang of tough hobo girls. The gender reversal extended into prison movies and even war films and gangster films.

CN: Is there anything which we haven’t discussed and would like to point people toward as a recommendation?

EK: The book [The Lady with the Torch: Columbia Pictures (1929-1959)], which will be in English and published by Les éditions de l’œil. It features nearly 20 new essays and many rarely seen stills from the archives of Sony/ Columbia and Cinémathèque suisse, both partners of the Locarno Retrospective. In the book, which will be available during the festival, there’ll be, among other things, first-time studies of some of Columbia’s underrated contract directors, such as Roy William Neill, Nick Grinde, Alexander Hall, and Charles Vidor.

The biggest lesson I have learned, which should make auteurists very happy, is that at the end of the day, it is the director’s style –good or bad, original or imitative – that stands out at Columbia.

Grande cinema in Piazza Grande o a casa, con blue TV.

Pronti, insieme.

In the weeks leading up to the Festival, we reached out to some of Locarno’s most illustrious former guests and asked them to share their first memories of the fest – whether that meant impressions from their world premieres or casual walks around the lake. The result, Beginnings, is a treasure trove of anecdotes and recollections; a polyphonic mosaic of the Festival assembled by those who’ve shaped its history.

The first time I went to Locarno was in the mid-’90s, when I was still a student, as a participant in “Cinema e Gioventù” – the Locarno Film Festival’s Youth Jury. It was the art teacher with whom my brother and I always discussed films who drew our attention to the program. I remember the first time we made the pilgrimage to the Piazza Grande, with a group of around 15 people. We were all very excited, almost awestruck, to see this legendary place for the first time. I can still dimly remember that in the movie we watched afterwards – it was probably the opening film – a man swam through a stormy sea. I don’t remember whether he was fleeing or swimming to freedom, or whether he was an athlete looking for some kind of rush. This scene – a man crawling through untamed masses of water – is my oldest Locarno memory. Every now and then I decide to look up the movie – but something always stops me. Perhaps I like the fact that I no longer remember; that I no longer know the motive behind his swimming. It remains a mystery to me. And with all the blurriness and imprecisions this scene has accrued ever since, it now seems strangely rich to me... That first summer in Locarno was the beginning of a love affair that continues to this day: with the festival, with the festival experience, with films. Since then, countless other experiences have been indelibly etched into my memory and I look forward to the many more fires Locarno will ignite, and which will also blur from year to year – like the swimmer in the roaring sea

I went Locarno for the first time at the age of 17 to take part in the “Cinema e Gioventù” program together with my brother and a friend. Locarno cast such a spell over us that the three of us returned to the festival again and again in the years that followed. Fortunately, we soon got to know the person in charge of a public playground, who allowed us to pitch our two tents in an open tree house in the forest during the festival. He said we could do this every year from then on if we let him know in good time. I still remember well how we wrote a handwritten letter every year to announce our arrival. Email and cell phones weren’t common back then. And so Locarno became an adventure every year. We looked forward to swimming in the Maggia, to the little open wooden house and to the many films and encounters. There was something wild and free about life, but also something structured about the movie showtimes we didn’t want to miss. I still remember the sound of raindrops on the tents and the sound of the hedgehogs that once crept around our tents at night. I have never heard that strange sound since. The memories of our tents and the wooden hut come back to me whenever I walk from FEVI through the forest to the Maggia. I wander through the woods, happy and wistful in equal measure, and see three ghosts closing their tents to disappear into the world of the next movie.

By Cyril Cordoba

What we know today as the Locarno Film Festival was launched in 1941 as an event dedicated to Italian cinema – not in Locarno, but Lugano! When the fifth edition was cancelled at the last minute in 1946 – after Lugano’s population voted against building permanent structures for the event – it was hastily relocated.

On the evening of August 22, 1946, 1,200 spectators gathered for Giacomo Gentilomo’s O Sole Mio (My Sun) in the garden of Locarno’s Grand Hotel, and a new chapter in Swiss film culture was opened.

In its early years, the LFF was structured as a primarily social event, drawing tourists with commercial films such as the popular comedy Don Camillo (1952). However, it also featured the works of renowned artists such as Sergei Eisenstein and was a showcase for Neorealism, among other burgeoning film movements. Locarno would also become one of the first Western film festivals to welcome movies from the Socialist Bloc – particularly East Germany – earning a reputation for being a place of “peaceful coexistence” amid growing Cold War tensions, where the films of John Wayne could share billing with Chinese or Polish productions. Nevertheless, Switzerland was a deeply anticommunist country, and even the programming of films such as The Cranes are Flying (Letyatzhuravli) – Mikhail Kalatozov’s 1957 masterpiece, which received the Palme d’Or at Cannes – was deeply controversial.

Contrary to Venezia, Cannes, Berlin and many others, the Locarno Film Festival was not controlled nor funded by the government. Its creation was not a “top-down” political initiative, but a local, “grassroots” one. That meant that the LFF wasn’t constrained by diplomatic incentives in selecting or awarding participants – and yet the lack of governmental support also made things difficult for the organizers, who consequently lacked valuable leverage in their negotiations with industry folks. Commercial disputes with Swiss distributors and exhibitors resulted in the Festival being cancelled in 1951 and again in 1956. This apparent instability meant that there was a real threat that another town might successfully petition to “steal” the privately operated event – after all, as the people of Lugano knew, that had already happened once!

The Festival’s future was secured, however, with the Swiss government’s official recognition of Locarno as a “national event” in 1954. Moreover, in 1959, the LFF was “crowned” as an A-list festival by the FIAPF (International Federation of Film Producers Association), which ruled the international film festival circuit. This certification, together with the organization of UNESCO-sponsored youth cinema events and high-profile retrospectives of auteurs such as Akira Kurosawa (mounted in collaboration with the Cinémathèque Suisse, or Swiss Film Archives), proved that Locarno, over the span of its first 15 years, was slowly but surely becoming a Mecca for cinephiles.

Do you have any memories or anecdotes from

For this year’s edition of Pardo, we invited historians Cyril Cordoba and Lucia Leoni to take us daily on a tour through the Locarno Film Festival’s history, chapter by chapter. 1946—1959

Emozioni uniche al Locarno Film Festival con la Posta.

By Julia Scrive-Loyer

“HowcanIaskanyonetoloveme WhenallIdoisbegtobeleftalone” “Left Alone”, Fiona Apple

People often wonder how to make a perfect movie, but the answer is pretty obvious: you can’t. Why? Because you weren’t making movies in the ’30s, which has been scientifically proven (by me) to be the most perfect decade in moviemaking. You think I’m exaggerating? Just look at what’s playing during the Columbia Pictures retrospective here in Locarno. Or, let’s take an example: Craig’s Wife (Dorothy Arzner, 1936). It might not be the most perfect movie ever made, but it comes deliciously close and consists of ingredients of the finest quality.

Rosalind Russell talking as fast as she can? Check. John Boles’s soft looking mustache? Check – and add a pair of soft looking eyes. A satisfying chiasmus1 to bookend the movie? Check – and we’ll be getting into it in a minute. A supporting cast that adds tenderness and comic relief to the story? Triple check. And then of course the obvious: Dorothy Arzner. I was a bit intimidated by having to write about Craig’s Wife without her becoming the main subject, but it is important to celebrate the fact that she was the only woman director in Hollywood during that period. Moreover, we can thank her for the boom mic, Katharine Hepburn, Rosalind Russell, and Lucile Ball, for being a freelance queen, and for portraying unconventional and complex female characters. Characters who make mistakes and have to deal with the sometimes devastating consequences of their actions.

Craig’s Wife is based on a play, and it shows. In the best possible way. As a screenwriter myself, movies based on plays are always particularly thrilling because of their efficiency. Here we have very few settings other than the Craigs’ house, and the story happens in a timeframe of 24 hours. The only thing I regret is there not being a complete unity of plot. Even though a murder helps accelerate the central conflict, I feel its magnitude was unnecessary. I do understand though that the murder, the main plot, and the bland subplot of the niece and her fiancé present a range of different marriages.

What I do find very special is the chiasmus I was talking about. Craig’s Wife is a masterclass in how to introduce a character through their absence. When the movie starts, Harriet is not home, so we discover who she is by what the others say and do when she’s not there. The way the help around the house interacts with the vase Harriet keeps on the chimney; the way Walter’s aunt is happy for him to go hang out with his friends; the way the next-door widow feels confident bringing over roses. A myriad of details prepare us to know Harriet’s character, helping us judge her beforehand, warning us that it will feel suffocating as soon as she returns. When we finally meet Harriet, she tells her niece that she married to be independent, to have a house, her space, her things. Her niece is horrified, of course. When she returns home, we feel the sense of suffocation is mutual.

Yes, she controls everyone in the house with a passive-aggressiveness perfectly played by Russell – but it also feels as if her husband is suffocating her. In the end, she has the house all to herself, after admitting to Walter she never loved him, and after pushing away all those who tried to cater to her needs. Now the house is built through the absence of others.

The more I think about the movie, the more fascinating I find Harriet’s character. It’s difficult to love her. I still don’t know if I’m supposed to. I feel devastated for Walter, who actually loved his wife – how hard is that to find in movies! – and feels betrayed by the way she’s been using him. And I am bewildered by how matter-of-factly she defends her position. But there’s a tiny gesture I find absolutely heartbreaking towards the film’s conclusion. Once everyone’s gone and Walter has destroyed the vase on the chimney, Harriet fixes the position of the remaining ornaments with a defeated expression. She looks at them as her most prized possessions. And they are – everything in that house is a treasure for her. It makes me wonder about her childhood, how much she had to fight for that independence, for that joy of having her own things, taking care of her own place.

One of my pathologies is that I mention Éric Rohmer in almost every text I write, and this will be no exception. He also had a talent for creating characters that felt sometimes unlikeable but always relatable in their imper-

Lose yourself in the core of Locarno Film Festival’s pulsating atmosphere at Rotonda by la Mobiliare .

La Mobiliare is Main partner of the Locarno Film Festival. mobiliare.ch/locarnofestival

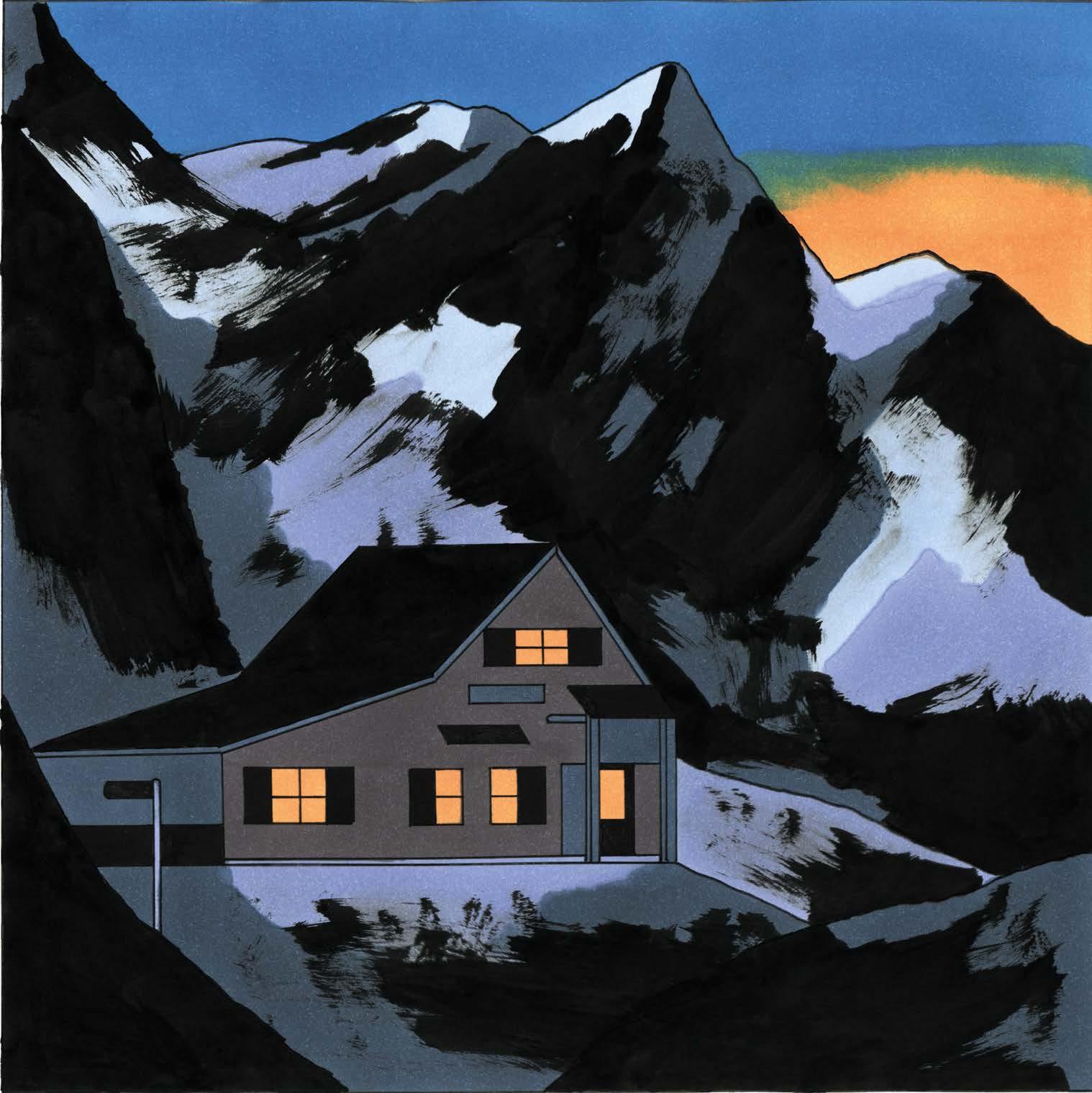

by Paolo Cognetti

◼

Switzerland

PROPOSTE IMMOBILIARI IN VENDITA

IMMOBILE CARATTERISTICO NEL NUCLEO

Meride | 8 locali | superficie totale mq 325 ca. | superficie loggia mq 80 ca. | giardino mq 107 ca. | tipici interni ticinesi d'epoca | residenza primaria | CHF 650'000.-

GRANDE VILLA CON PISCINA E DEPENDANCE

Novazzano | 11 locali | superficie abitabile mq 378 ca. | superficie terreno mq 1'300 ca. 2 posti auto interni e 4 esterni | vista aperta | CHF 2'350'000.-

VILLA D’AUTORE CON PISCINA

Novazzano | 8.5 locali | superficie abitabile mq 365 ca. | superficie terreno mq 1'730 ca. 2 posti auto interni e 2 esterni | zona tranquilla e ben servita | CHF 2'850'000.-

CASA PARZIALMENTE RISTRUTTURATA CON 2 APPARTAMENTI

Solduno | 6.5 locali | superficie abitabile mq 170 ca. | superficie terreno mq 625 ca. 3 posti auto esterni | zona residenziale con vista fiume | CHF 1'150'000.-

Per informazioni: +41 91 695 03 33 immobili@interfida.ch interfida.ch

by Gianluca Jodice

August 7th, 9:30 PM, Piazza Grande

◼ The voice of the audience is key for a film’s success. That’s why since 2000, the Festival’s most trusted jury – the audience – decides which film wins the Prix du Public UBS award.

◼ Vote for your favorite film at the Piazza Grande with the QR code or the link on your e-ticket.

◼ All participants

and