Sculpting (W)right

BRINGING THE LEGACY OF SCULPTOR AND SPY PATIENCE LOVELL WRIGHT TO LIFE BY REIMAGINING HISTORICAL WOMEN IN PUBLIC SPACES

BRINGING THE LEGACY OF SCULPTOR AND SPY PATIENCE LOVELL WRIGHT TO LIFE BY REIMAGINING HISTORICAL WOMEN IN PUBLIC SPACES

Using thorough research into the life of sculptor and spy Patience Lovell Wright, “Sculpting Wright” reimagines public spaces through digital renderings, proposing potential monuments. The intent is to show how underrepresented, revolutionary women can be properly acknowledged through accessible, visual means.

Patience Wright, Profile Bust of Benjamin Franklin, 1775. Wax, glass, wood, and paper. Metropolitan Museum of ArtThe Lincoln Memorial. Mount Rushmore. Marble renderings of George Washington just about everywhere. For many, these first come to mind when considering honorary statues in public spaces all men.

The sculpted monuments making up the United States’ landscape are predominantly male, despite women's vast accomplishments and contributions in American history. One may point to the Statue of Liberty in opposition to this, one of the most striking monuments in the country. However, Lady Liberty’s image, after a Roman Goddess, is one based upon a mythologized, symbolic ancient figure, not a woman who directly impacted the course of American History.

According to the Monument Lab, only 6% of the “Top 50” memorialized in monuments are women, a staggering number considering the influence of women in just about every sphere, despite the genderbased roadblocks they encountered. Frequently, statues of women are abstracted and feature fictional/mythological figures (such as Lady Liberty). According to a Gillian Brocknell piece for the Washington Post, there are more public statues of mermaids than congresswomen in America—an overall presence of female monuments far from the valiant, wisened depictions of men.

Just as the achievements of women have been overlooked and ignored in American history, so has their right to take up space in public spaces their right to be honored as their male peers have.

Patience Wright, c. 1782. Artist unknown. National Portrait Gallery.

When reflecting upon crucial players in the American Revolution, history’s celebrated patriots are overwhelmingly male: Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, and Paul Revere, to name a few. One might envision quintessentially “masculine” images of the fight for liberty, of soldiers valiantly carrying American flags on battlefields, or Leutze’s mammoth painting of Washington confidently crossing the Delaware. But, women also played important roles within the Revolutionary landscape, dedicating their efforts to the patriot cause.

Art can inspire and mobilize its viewers, causing them to take action. As sculptor and revolutionary spy Patience Lovell Wright proved, however, action can also physically exist within art itself. A staunch American patriot and wax sculptor living abroad in 1700s London, Wright used her status as the portraitist of Britain's elite to receive information about the British military movement— smuggling this information to figures such as Benjamin Franklin.

Like many aspects of Wright’s life, her spying took an unconventional form. She allegedly hid messages inside her wax sculptures before they were shipped to America chronicling tidbits she overheard when amongst British nobility. Along with this, Wright also subverted gender and class expectations of a farmer’s daughter American, living abroad and interacting with British high society.

Born in 1725, Patience Lovell belonged to a Long Island Quaker family, later residing in Bordentown, New Jersey. Her family also followed Tryon beliefs, such as vegetarianism—defying mainstream culture at the time. Wright and her sisters wore veils from seven onward and only white. Even from a young age, Wright defied larger social expectations of how a girl/woman should present herself. She was educated in spheres such as agriculture and was taught to read and write. Such an intellectual advantage was not endowed on many women in 1700s America: providing Wright with the confidence and academic backbone to exist in spheres that historically frowned upon women.

The nine Lovell sisters experimented with artistic forms in childhood. Using resources around them, such as herbs, tree gum, and earth, they created paints to make pictures. Patience, always the trailblazer, began using dough and clay to sculpt figures.

The left image is a rendering of a potential monument to Patience Lovell Wright outside of her childhood home, in her hometown of Bordentown, NJ, where only a plaque currently stands. It depicts a young Wright at home with her sister Rachel, sculpting figures from clay. Background image credit: Devry Becker Jones (CC0), November 14, 2020

Patience Lovell Wright was married in 1748 to an older man, a Philadephia farmer named Joseph Wright. They had four children together, and when Wright was pregnant with her fourth, Joseph died, leaving Patience a widow with few resources to support her family. Joseph’s finances had been declining since the death of his own father, leaving Wright in a difficult position. In the 1700s, perhaps other women would adopt the archetypal ‘helpless’ widow role. Wright defied gendered expectations, taking her childhood hobby of sculpting, which she also did in adulthood with dough to entertain her children, and turned it into a career.

Wright and her sister Rachel created commissioned work, mementos of the deceased for grieving families, or mythical/Biblical imagery. Such work defied Quaker notions regarding idolatry, but Wright created art nonetheless. Wright also made life-size wax figures, complete with hair and clothing. Due to the intrigue of these sculptures, Wright and her sister opened multiple waxwork studios in America. They were met with great success: a much more affordable and accessible way for people to see wax art than commissioned work.

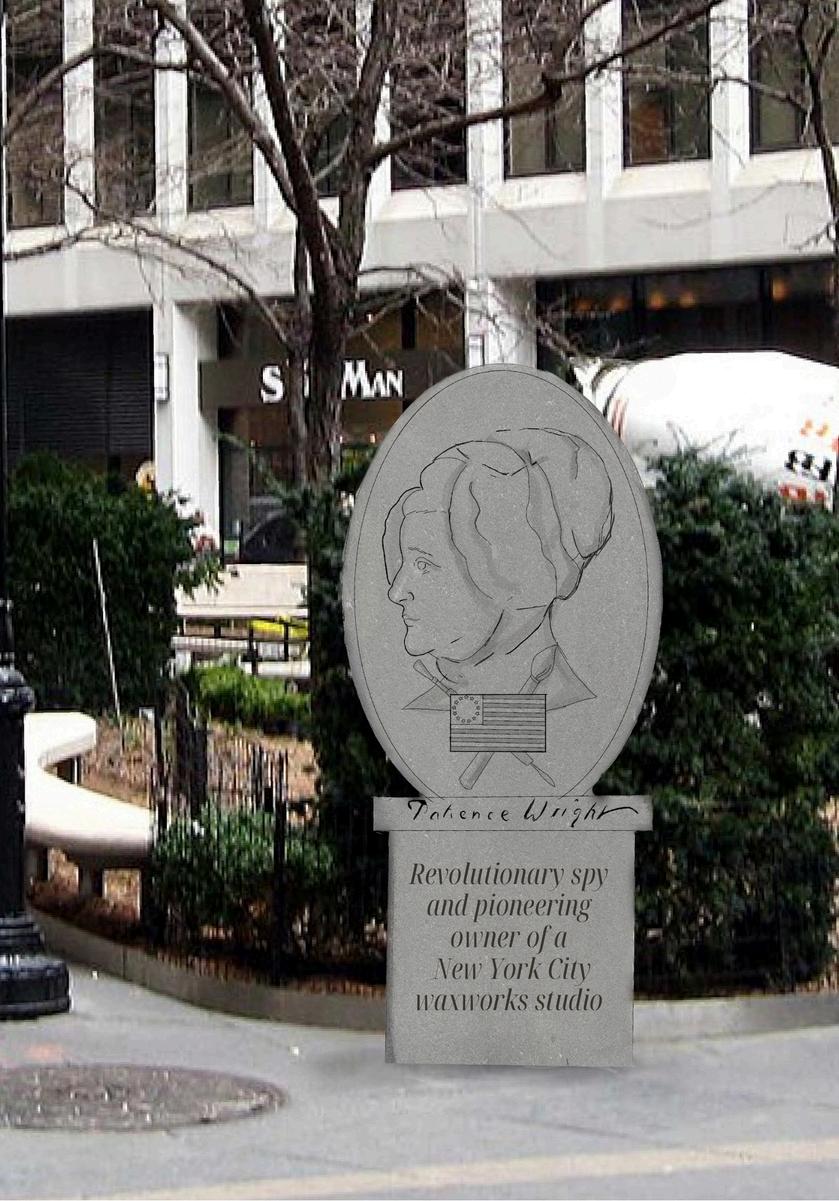

One of these waxwork studio locations was on Queen Street in New York City. Though Queen Street no longer exists, its location can be traced around the Wall Street/Pearl Street area on the south side of Hanover Square. The left-side image imagines a monument to Patience Wright in Hanover Square, depicting her profile similarly to her “Bustos” of sitters. Inspired by The monument is adorned with a “Betsy Ross” version of the American flag, sculpting tools, and a recreation of Wright’s own signature. The piece loosely references a surviving John Dowman 1777 study of Wright, copyright The Trustees of The British Museum. Amid the contemporary hustle and bustle of city life, Wright’s monumental image would serve as a testament to the women who came before.

Background image credit: Hanover square by Jim Henderson, March 2008 via. Wikipedia.

Wright’s successful waxworks studio was destroyed in a 1771 fire, and much of her work with it. Faced again with a tribulation, Wright persevered. With the assistance of friend Jane Mecom, Benjamin Franklin’s sister, Wright traveled to London and integrated herself within elite circles both as a talented wax portraitist and an allAmerican novelty. Her commissioned work soon turned into performance art. Wright would ramble and warm wax suggestively between her thighs. She would dramatically recall stories from American life and kiss each American she encountered abroad. Patience would outright critique King George (whom she merely called “George”) on his handling of the American situation as she sculpted him, making her patriotism known. Eccentricity was innate in Wright’s persona. Some, like Abigail Adams, found it offputting, while many found it entertaining. Wright’s list of connections during this time was extensive. King George III, Queen Charlotte, Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, parliament members, and lords, among other prominent Americans and Brits, made up Wright’s significant network.

The sculpture rendering on the lefthand side depicts Patience Lovell Wright amid one of her eccentric sculpting performances, a heap of wax and sculpting tool in hand. “Carved” into her skirt, inspired by the role skirts would play in her performance, is a quote found through Charles Coleman-Sellers' research. The sculpture’s proposed location is Folger Park in Washington D.C., a city that has many monuments to male revolutionary figures (a handful whom Wright herself corresponded with) but not as many of women.

Background image credit, NPS

PATIENCEWRIGHT revolutionaryspy

Smuggledinformationfrom LondontotheU.S.(hiddenin herhandmadesculptures) duringtheRevolutionary War.

Wright did more than vocalize her patriotic opinions when abroad. She is also believed to have taken action, smuggling information overheard from her time amid British aristocracy. Further, not only did she spy, she did so by hiding knowledge within her sculptures, sending them ‘across the pond’ to people such as (allegedly) Benjamin Franklin or the Continental Congress. Some have theorized that Wright’s first information-smuggle was through the Earl of Chatham’s wax head, sister Rachel Wells on the receiving end, handing off information to the Continental Congress (Coleman Sellers 69). In a surviving letter to a New York Reverend, Wright bluntly describes her disapproval of the British government: “All [the Parliament’s] schemes is to Inslave you all. Don’t be decevd. No honesty nor Honor is Expected from ths side of the watter — Stuped Ignorance is taken place, the Poor opresd, the Rich Proud and Impedent and [no] fear of god or men.” (Coleman Sellers 71).

As the severity of the Revolutionary War heigthened, however, Wright was effectively shunned from British high society, due to her continuously outspoken patriotism.

To the left, a rendering for a sculpture of Wright holding a bust of Benjamin Franklin and a scroll as a symbol for her informationsmuggling. Loosely inspired by a portrait of young Patience Wright, housed by the National Portrait Gallery, and Wright’s ca. 1775 profile Bust of Benjamin Franklin, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jefferson Square in Philadelphia, PA, as the backdrop, the location of one of her studios, and the receiving end of her spy information (i.e. Benjamin Franklin).

Conservancy.

"Ihavetravildthroughallthedifirentways ofprovidencetoBringaboutthegrandand mostExtrordaryRevolutionsbythemost unliklymeans[sic]."

-Patience Wright, in a letter to Franklin, via Kokai’s article

Project creared by Lena Bramsen, with the supervision and support of Professor Gina Luria Walker

Brockell, Gillian. “America’s 50,000 Monuments: More Mermaids than Congresswomen, More Confederates than Abolitionists.” Washington Post, 2021. Sellers, Charles Coleman. Patience Wright: American Artist and Spy in George III’s London. Wesleyan University Press, 1976.

Kokai, Jennifer A. "Molding a Heroine: Patience Wright and Transatlantic Notions of American Female Patriotism." The Journal of American Drama and Theatre 21, no. 2 (Spring, 2009):49-66,115. https://monumentlab.com/

Serratone, Angela. "The Madame Tussaud of the American Colonies Was a Founding Fathers Stalker." Smithsonian.com, December 23, 2013.

Images:

Dowman, John. Study for a portrait of Mrs Wright. 1777. Charcoal and black chalk, touched with red chalk, British Museum, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Patience Lovell Wright by Robert Edge Pine, c. 1782. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Patience Lovell Wright (née Patience Lovell) published for London Magazine, line engraving, published 1 December 1775, National Portrait Gallery.

Profile Bust of Benjamin Franklin, Attributed to Patience Wright, ca. 1775, Wax, glass, wood, paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art. Young Patience Wright. National Portrait Gallery.