LIGHTS & SHADOWS

Masthead

Editor-in-Chief and Designer

Manuela Ludolf

Literary Submissions Editor

Brooke Lunsford

Assistant Editor

Hayden Jordan

Faculty Advisor

Professor Daryl Brown

Logo Graphic Designer

Izzy Smith

Cover Art

Reminiscências V. 50x65cm. 2019. by Marcelo Spolaor

Letter from the Editor

Chapter I: The Comfort of Knowing

The First Step by Anna Hilb

Ascension Day by John Stevens

A Desert Memory by Charles Michelson

Florence by Hannah Myrick

Rhythm and Roots by JaKyra Phillips

Hurricane Gilbert by Vinnette Gibson

Who Shall Thee Look For? by Shamori Thompson

by Rebekah Jent

Chapter II: The Discomfort of Not Knowing

Cast

by John Stevens

L&S Spotlight

Chapter III: The Discomfort of Knowing

Ceaseless Cotillion by John Stevens

Being From Memphis by Averie Yeager

Staying Woke by Eric Morris

Cicadas Sing by Adam Rausch

Clinging by My’Chyl Purr

Girlhood by Lauren Daniel

Liberation by Hannah Green

Mnemonic Devices by Katelee Smith

The Last Unanswered Phone Call by Samantha Robins

Nature’s Unrelenting Reign by Anna Hilb

Pendulum by Elvie Skinner

Nothing But a Man by Zane Turner

Broken by Elvie Skinner

Chapter IV: The Comfort of Not Knowing

Ms Jane’s House by Eric Morris

Candle by Savannah Andrews

A Depiction of All the Things I Allow to Take My Peace, in the Form of a Chair by Jessica Bullock

The Bucket Theory by Rebekah Callahan

Keats Riffs on Homer by Charles Michelson

Are You Washed in the Blood? by Katelee Smith

Dear Reader,

Letter from the Editor

Welcome to the Spring 2025 issue of the Lights & Shadows, the University of North Alabama’s literary journal. What you will experience now is an amalgamation of Southern art made possible by UNA and regional writers and artists.

The (Dis)Comfort of (Not) Knowing, this issue’s theme, can be read in four different ways, and those constitute the four chapters that represent the shift from innocence to maturity–as well as their coexistence.

The Comfort of Knowing opens this journal with the certainty of good times. There, you will delight in friendship and rest in contentment. There will be no fear of falling or uncertainty because you are comfortable with the surroundings you know. You may relate to this section when you find the good in tepid or sorrowful times or simply recognize the grandiosity of certain fulfillments such as love, friendship, and success. You can think about the ephemerous aspect of those in real life, but there, they are eternal.

The Discomfort of Not Knowing shifts the journey to the previous chapter’s polar opposite. There, you do not know a thing, and that frightens you. Where did time go? Where did people go? Where did you go? It does not matter how much you prepare because life will come back to you in a lightning strike when you thought it was an earthquake you were about to experience. Should you embrace the

unknown, or should you dive in despair?

In The Discomfort of Knowing you may ask yourself if it is better to know or not to know. When you grow up and discover yourself, your family, and the whole world as not as great as you imagined, what do you do? Suddenly, you know about heartbreak, poisoning genes, structural issues, and death. You contemplate whether ignorance was always the true bliss because what is outside is too much for your comfort, and you know there is nothing you can do.

The Comfort of Not Knowing ends this journal at the beginning of life, and it does so for the reader’s own nostalgia. There is where ignorance is bliss; there is where you are before The Discomfort of Knowing. You do not have a glimpse of tragedy when you are a child, and you rest in your mother’s arms until you fall asleep. Funny enough, there is where you have the devilish wish of uncovering every mystery you have ever encountered.

Your editing committee is proud to present this issue to you. By flipping this page, know you have arrived at the comfort of home, but recognize comfort is truly ephemeral and that you have to arrive in Chapter II. Then, be thankful for all the despair you do not currently experience and for all that you do or do not know so you can finally delight yourself in the revival of your youth.

Enjoy the journey.

All the best,

Manuela Ludolf Editor-in-Chief lightsandshadows@una.edu

L&S Award Winners

Best Prose

Are You Washed in the Blood? by Katelee Smith

Best Poetry

Salt Six Feet Under by Mark Smith

Best Artwork

The Return of the Purple Menace by Brandon Underwood

Chapter 1

The Comfort of Knowing

Goodnight by Brandon Underwood

The First Step

by Anna Hilb

As I stepped off the bus to shouts of, “GET IN LINE!! GET IN FORMATION NOW,” the blazing Georgia sun blinded me, and the sweat dripped down my spine. My head began to pound, and I thought to myself, “What have I done?” For what felt like an eternity, I stood in a rigid line with my army-issued duffle bag held high over my head. The boy behind me was crying hard, his sniffling and whimpering did nothing to alleviate the ache between my brow–a preview of how rough this journey would be.

After graduating from college with my bachelor’s degree in dietetics at age 20, I was uncertain about which path to take. Ready for a break from academics, returning for my master’s degree was not in my immediate future. I felt lost. A friend I knew from the campus recreation center had recently enlisted in the Army, and I wondered if the military could give me the direction I needed. This question led me to my first step towards enlisting. I went the next day and spoke with a recruiter in the local Army recruiting office. He said I, Susanne, the unsure graduate, would be a great candidate for officer training school, and with his help, I began the process of enlisting. It was this path that eventually brought me here to basic training, surrounded by unfamiliar faces and the pressure to succeed.

Determined to survive, I made a promise to myself not to be the one who gave up. What seemed like daily, someone else from my reception platoon threw in the towel and went home. The lack of sleep weighed on us all, and for me, even breathing felt like a burden. The drill sergeants stormed in at random, sometimes in the middle of the

night, making us perform drills or checks. With wake-up calls at 0500 every morning and added sleep deprivation, each day felt like I had run a mental marathon. But the barracks turned into my pseudo home; the female-only quarters brought me back to sharing a room with my younger sister Maria. She made her bed each morning with a precision my drill sergeants would be proud to inspect. Each bunk bed in the barrack had to be made perfect according to regulations, or we all suffered the consequences of a trainee’s failure.

Jennifer was on the bunk above me, her determined eyes and friendly smile put me at ease, and she became a fast friend as we pushed through the grueling weeks. We shared the struggle to make it through each day–from perfecting the bed-making to learning how to keep hairstyles within regulations. In moments of shared laughter and homesickness, she reminded me of Maria, who was finding her path in college. That connection grounded me in ways I hadn’t expected, and Jennifer was much further from home than me. She came from the middle of nowhere Idaho and enlisted the day after she graduated high school. Her family was not supportive of her decision, and about that, she said, “I signed the papers, so there was nothing they could do to stop me from going, but at least I left on a good note.”

My family, in contrast, was excited about my new journey. I cherished their support–especially when reading their letters and opening the bulging care package they had so carefully put together. The moleskin my mom tucked in the box helped me through many painful rucks and runs. I cried reading the letter my sister had penned in her blocky handwriting, expressing excitement about pictures she had seen of my training on a military Facebook page and saying she missed me at home. Even far from everything familiar, I was never truly on my own.

Three times a day, my platoon filed into the chow hall for meals, but even eating became an exercise in discipline. On some days we sat briefly, savoring a few bites, but on others, we barely had time to taste our food before it was time to move. The strict timing echoed

the unpredictability of training itself, teaching us to adapt, stay sharp, and keep going–even with something as simple as a meal. Adding to the tension, the Drill Sergeants circled around screaming out, “CHEW YOUR FOOD,” and “EAT FASTER.” On one of these occasions, I made the mistake of looking a Drill Sergeant in the eye; resulting in my entire platoon’s removal from lunch to stand in formation until lights out. While the punishment lit a flame of anger in me, the constant adaptation sharpened my endurance, something I’d rely on more and more.

One morning, we were woken up at 0330 for an eight-mile ruck. My eyes burned as I swung my legs over the side of my bunk, the floor’s icy chill cutting through my sleepiness. I reached for my boots–laced up the night before to save time–and shoved my feet into them. My ruck rested at the foot of my bed. Its weight dug into my shoulders as I hefted it into position, but I pushed the thought far away. As we lined up in formation, no one around me said anything, for it was too early for words. Nerves gnawed at my gut as the fear of failing the ruck prickled in my conscience. My mantra that morning was the repetition of, “Just keep moving, don’t be a quitter.”

“Fall in!” came the throaty yell of the Drill Sergeant. The first steps were always the hardest; then I settled into a rhythm, going numb to the activity. My breathing became meditation–inhale, exhale slowly, repeat. The incline rose at four miles with a steep hill, and my calves burned like fire with each step. The Soldier’s Creed replayed in my mind to distract me from the pain, “I am an American Soldier. I am a warrior and a member of a team.” Eventually, the cover of darkness faded away to a sweltering sun. At six miles, the pooling sweat trickled down my brow in a steady flow, and I wished for the cool, fresh air and the blissful darkness. The last mile stretched endlessly, every step marching me further into an exhausted state. When the command to halt was shouted, my throat tightened, relief washing over me like a wave. I had finished strong, we all had. Another hurdle leaped over, and I could not wait to cross the finish line.

Days in the field were different from our usual training, a gru-

eling mental and physical test. By day three of five, exhaustion clung to me, and the lack of showers took a toll on all of us. The stench, the dirt, sleeping on the ground, and the intense humidity left me hanging on by a thread. The field was a parody of the campouts and bonfires with friends back home, but the reminder was anything but comforting. My hair was getting matted, but the standard low bun hid the mess well enough. I didn’t mind being a little dirty; however, the layers of sweat, dirt, and face paint became like a grimy second skin. On the fourth morning, I woke up to a swollen spider bite on my thigh, and each step I took sent a pulsing pain down through my foot. It wasn’t a poisonous spider, so I kept my mouth shut and cleaned it with alcohol pads during the remaining days. I could suffer through a few days of pain to avoid getting recycled. No one wants the embarrassment of repeating training.

The bathroom situation was another unexpected test. As a girl, I had squatted in the woods during family camping trips or peed behind a car at a bonfire, but none of these prepared me for field bathrooms. Pooping in the woods surrounded by a whole platoon of virtual strangers, and mostly men? This sucked on a whole different level. My body didn’t care where we were, though, so I found a wide-based tree far enough from the group to offer me some privacy and squatted over the shallow hole dug with my entrenching tool. I prayed no one would take a walk by my hideout. The first time was uncomfortable and disgusting, but I adjusted, even cracking jokes about shitting in the woods during field training while going through Officer Candidate School (OCS).

Eating an MRE (meal, ready-to-eat) at the end of the day was hardly a relief. The plastic pouch held surprises I’d rather forget. Though trading with others for a pack of peanut M&Ms softened the disappointment. My first MRE was exciting, as my military-enthused uncle had a stash of them for when “shit hit the fan.” Realizing it was dry crackers, rancid-tasting beef stew, and plastic cheese, quickly cured me of any lingering enthusiasm. MREs were supposed to give us the

calories we needed to properly perform our training. However, after choking down a pouch of chili mac, I was considering starvation a more pleasant alternative.

When we hit the range, all my years of shooting skeet in the backyard of my grandparent’s house in South Alabama had paid off. I excelled in the range. The steady breathing, the calm in high-pressure situations, and the shooting felt like second nature. The process was almost technical. I controlled my breathing, waiting until the exhalation before firing off rounds into the targets. The key was to stay calm. That was manageable for me, for I had never been one to lose my cool. The prone position was my strong suit, my body able to lock into a stable position for the supporting rifle. Moving positions from prone to kneeling to standing was muscle memory by the end of training. The kickback from my issued rifle got the better of me once. The bruise left behind was a pulsing reminder to not get distracted. Here, I realized that while the physical challenges tested me, the skills I learned reminded me that I was capable, prepared, and ready for the next step.

As graduation neared, our daily training included ceremony practice. Soon, we’d be marching out from the woods to the field where everyone’s friends and family would be waiting. Smoke bombs would be going off as we left the tree line, adding a dramatic effect to our entrance. My parents and baby sister were making the trip, as I learned from their last letter. She was born only a few months before I shipped out, and I couldn’t wait to see how much she had grown. The day after graduation, Maria was joining me to drive me to my first station. The anticipation consumed me, making it a struggle to stay focused on finishing strong.

When the day arrived, we stood silently, everyone dressed in uniform and waiting for the signal to march. The eagerness to see my family after nearly three months made me feel giddy, though my body was exhausted. Victory Forge Week had zapped the last of my strength, and I was running on fumes. But, despite the fatigue, I stood tall, proud to have persevered to the end. Suddenly, the drill sergeant’s sharp com-

mand of “MOVE OUT!!” cut through my thoughts, snapping me to attention. With that signal, we started forward through the trees towards the open field. As we broke the tree line, colorful smoke grenades ignited, filling the air with plumes of vibrant color. Adrenaline surged through me, filling my body with renewed energy as I heard the crowd cheering in the distance. By the time I left this field, I would no longer be a new recruit–I would be a United States Army Soldier. Everything came into sharp focus as I emerged from the smoke. Once we reached our position on the field, I scanned the crowd for my mom and dad, spotting them in front of the stands. I let out a breath of relief at the sight, a quiet smile forming as I saw their familiar faces. Tears welled in my eyes, but I held them back. Each second was a test of patience as I stood in formation, wanting only to sprint towards them and finally hug them again. Just a few more minutes, and I would be free.

The commander’s voice echoed across the field as he commended the entire battalion for our bravery, dedication, and commitment. Pride swelled within me because I knew I had earned my place with blood, sweat, and tears. It wasn’t just about recognition; it was the culmination of every challenge I faced over the past ten weeks. Each sleepless night, each grueling ruck, each moment of doubt fell away as I stood with a newfound strength and resilience. Holding my rifle at attention, the surreal realization settled in: I was a United States Army Soldier.

“Charlie Company… DISMISSED.”

Ascension Day

by John Stevens

He waved his hand through the air like a wand changing the room into a painting.

The artist’s touch in recluse clothes changing the world into whimsy.

Brush stroked bolero un pas de deux

In three-quarter time Steeped in sweet perfume.

if I could create with a magic wand I would grow Into a Neruda Poem Esa vez era como nunca, y como siempre.

15

Vamos tan allí, donde nada está esperando; encontramos todo el esperar allí.

That time was like never, and like always. So we go there, where nothing is waiting; we find everything waiting there.

16

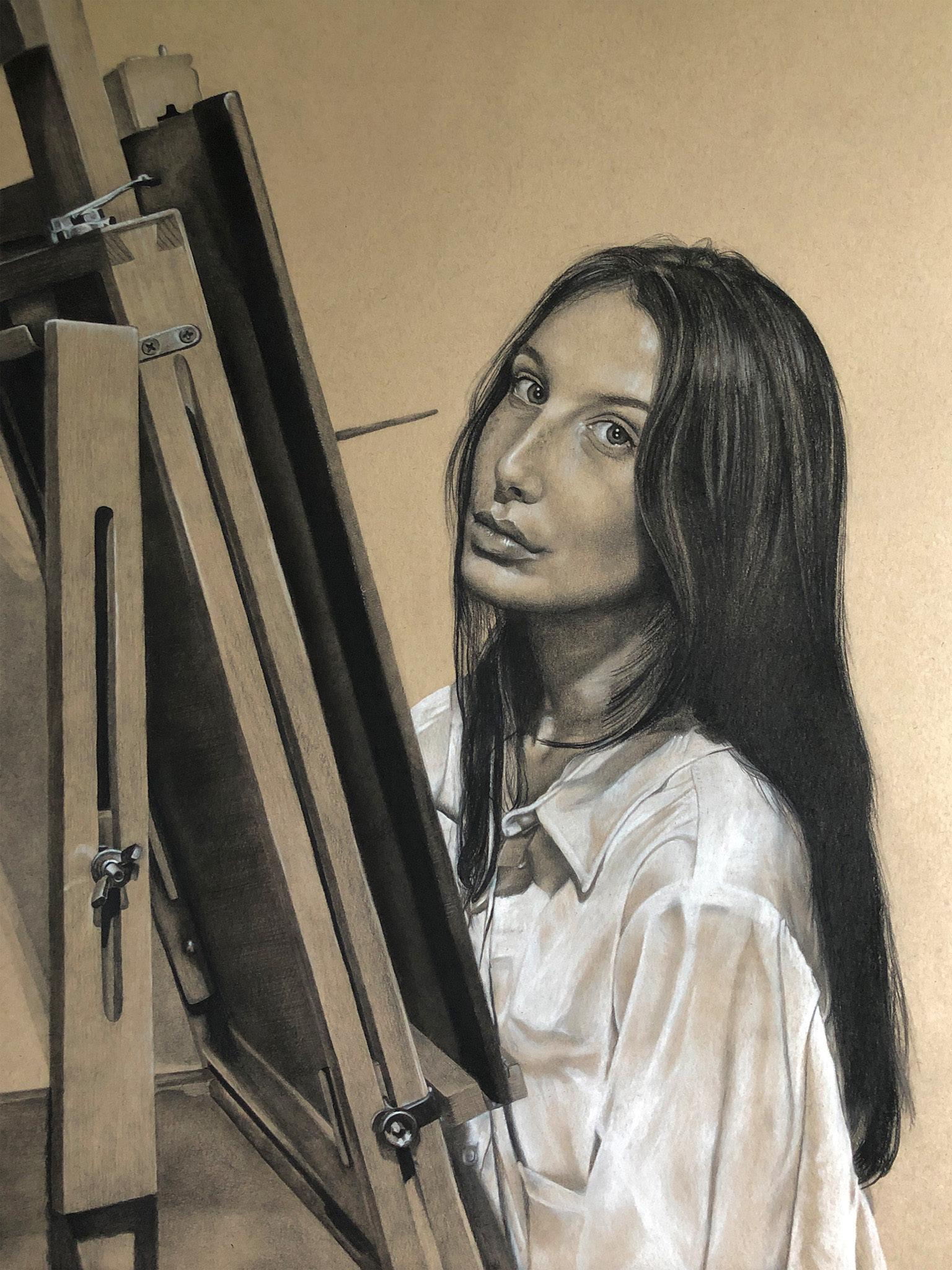

In the Eyes of the Beholder by Lacey Gross

A Desert Memory

by Charles Michelson

The rocks were shining in the sun, and there was a glimmer that could not be defined. That was always the way the stones shined. The heat as we looked upon some soft blue in the California desert was an inferno.

The steep slope of the rock face was like a mountain. Jagged, and of course, it was the middle of the day that we had embarked on our journey into the Anza Borrego. It was painted red and brown. As the light hit it, it became fiery orange. The All-American Girl Mine was not so much a mine as it was a giant dump site for blue kyanite. Its varying degrees of blue against the cooked earth were most striking and could be as penetrating as the blue sky above. We closely examined the ground for various samples. We picked up countless pieces of the blue rock, some larger than others. All were the quality one would expect to find in an abandoned mine.

It was the kind of heat where the drips of sweat formed instantly.

This was no ordinary heat. We smelled like pina colada. The use of sun-tan oil seemed counterproductive, but it served its purpose. The sun’s rays bore down like a wave.

Somehow, we managed to move all these rocks back to the car and return the car to the main road.

Off in the distance, we could hear men firing off guns. The drug cartels were not far from where we were, and they made their presence known. I was running a few minutes late; my previous meeting was over.

As we drove back to civilization, it felt like time had passed too

quickly.

Insufficient time was given, like the sand in the desert was being strained through a giant hourglass. It was as though the flash of the sun that day was telling me something. The smell of brush sage was still lingering in the car. It was a long ride from where we were in the desert. The destination was Coronado, a navy town. The Anza-Borrego is a combination of two aspects. The first is derived from the explorer Juan Bautista De Anza, and Borrego is Spanish for big-horned sheep.

I could only imagine what it must have been like to travel in the desert in 1774. Was it as hot as it was when I was in the desert with my father? Traveling to the land where these mineral samples were was tedious, as though we were walking a tight right. Sometimes, the road was not geared for vehicular travel. On one occasion, we almost got our car stuck.

These moments with my father in the desert are some of the most treasured. They, along with the mineral samples, are how the image of this man enters my mind.

He wears a sweatshirt in ninety-degree heat.

He wears a red band around his glasses to keep them in place. On top of his head, he wears a baseball cap with the Chicago Cubs logo.

It’s not as hot this time of year, but we are still dripping in direct sun. The lizard sticks out its tongue, perched on a rock beside me. With tiny fire ants, you must be very careful. The tarnished sand makes dust clouds as we trudge up to the site where fossil seashells are to be preserved. It’s frustrating, as you know that the best samples have been picked over by rock hounders too.

That’s why we call ourselves rock-hounders.

We yearn for connection, whether with the land or our flesh and blood. As I desired to get closer to the land, I was unaware I was becoming closer to my family.

Florence

by Hannah Myrick

The river flows near city streets so fair, Where memories fill the southern air, With cobblestone paths, and the sun ablaze, A quiet Sunday filled with praise.

Court and Cherry with bikers on, Tennessee and Seminary where dogs are drawn, The city’s shining people out, Leo’s roar is heard about.

The heart is beating loud and proud, Of Florence who keeps an ample crowd. I love this town with all my heart Born and raised, I dread to depart.

Untitled by Leon Ono

Rhythm and Roots

by JaKyra Phillips

Without glancing up, Louise calls out in the direction of the door chimes, “Welcome to Rhythm & Roots. Sit anywhere you’d like, and I’ll be right over.”

“Hey, Ms. Louise!” the woman greets her.

She returns the greeting with a warm smile and rushes over to grab her into a hug. “Hey, there, Pat! It’s been a month of Sundays. I almost didn’t recognize you with that cute new cut. It looks good!”

Patricia strokes her short pixie cut bashfully, “Oh, you know. Just thought I’d try something new.”

“How your momma ‘nem?” Louise asks, watching for any sign of an emotional tic.

Patricia grimaces, “Oh, she’s fine. Everyone’s good, considering…” Her eyes float away toward the floor.

Louise places a supportive hand on her shoulder. “I know how it is, sweetie.” In a lower voice, she says, “If you guys need anything, just let us know. Anything at all.”

“Thank you, Ms. Louise. We really appreciate it. For now, what I need is to get some of that good food in me.”

Louise nods, “What can I get for you? You want your usual?”

“Yes ma’am,” Patricia answers. “You know me well.”

Louise beelines for the kitchen, glancing at her husband across the way, her eyes dancing with a childlike giddiness, lingering on the salt and pepper sprinkles of his beard.

She reemerges with a full tray in tow and saunters to a table in the far corner of the restaurant. “We got George’s famous salmon croquettes and rice with a lemon remoulade for you, Sam, a summer salad with grilled chicken, pecans, and strawberries for the lady, and a hamburger with no tomatoes or onions and steak fries with poutine for Lil’ Anthony.”

He peered at her over the rim of his glasses. “Now, Ms. Louise, I’m not so little anymore.”

“Boy, I used to change your diapers. You’ll always be little to me,” she chuckled.

Beverly comments, “Louise, this looks amazing.”

“Well, you’ve got Georgie to thank for that.” She smiles warmly. “Enjoy your meal folks.”

She strides past two men, father and son, when one of them calls out, “Let me get a slice of that good ‘ole sweet potato pie!”

“I got you, Charlie! Coming right on up,” Louise responds.

The younger of the two adds, “And a side of fried green tomatoes to go. My wife’ll kill me if I don’t come home with some. ‘The baby’s craving ‘em,’” he says mockingly. They all burst out in hearty laughter.

George’s magnetic aura moves from table to table as he welcomes everyone, stopping when one of the regulars—to tell the truth, they were all regulars: friends, neighbors, church members, people they’d see on their everyday errand runs—asks, “Hey, what’s your secret man?”

George laughs, “Ah, man. You know I can’t tell you that. You and Della Mae’ll put me out of business. She’d give me a run for my money now!”

“Ain’t that the truth?!” the man agrees.

Laughter and chatter flow throughout the restaurant. Old friends catching up. Families sharing stories of their day. Couples

basking in each other’s presence. This place was as lively as it had ever been on a Saturday evening. Every weekend, the people from all over Atlantic Beach would come pouring in to feel that welcoming hospitality of George and Louise’s. The food came accompanied by a love and warmth that you just couldn’t get anywhere else. This was one of their few safe spaces left.

It was in danger of not being enough. It seemed like operations were slowing down every single day. Despite having every seat filled today, it was never enough and simultaneously too much. It took a lot to run one of the homiest family restaurants around town. It required a lot of courage, wisdom, and expertise, which they had; but they were growing older. They could barely handle the crowd on days like this. They definitely couldn’t handle it seven days a week. Not without any help. After cutting down the menu by a few of the less popular items, and even limiting the hours to a couple of days a week, they still found themselves struggling to manage and keep up with the times.

Louise walks Mr. and Mrs. Peters, the older couple that stays two doors down, over to the entrance, handing them a carryout plate. “Carry this home to the grandkids. I know those little ones got a sweet tooth. I remember how much they just loved my strawberry shortcake last time.”

The husband, Joe, regards, “Appreciate it. Though I also remember all that carrying on they did after, too. Made them happier than Cookie Monster in a bakery, only more hyper.”

Louise giggles. “I’ll take the blame. It has just the right amount of sweetness for us, but the children… they’re another story.”

Sharon, his wife, responds, “I know that’s right. Speaking of, where y’all kids?”

She comments, “Oh, they don’t get down here much anymore. Lives of their own, too busy since they grown now. You know Janelle just opened a new practice. She always has some big, new case. Uh, Michael’s got business up in New York. Last we seen him was just after

the wedding. And Lucy… I don’t know what that gal’s up to these days, but she’s over in Texas. Living her best life as she says.”

“You know kids these days. They run away from home and never look back,” Joe offers.

“I mean. Can you blame ‘em?” Louise asks. “Ain’t much left around here. That’s reason everyone is getting away while they can. Everything’s going down. The Black Pearl ain’t been the same in a minute.”

And they knew. From the saddened look on Louise’s face, they felt it too.

Sharon, attempting to encourage her, exclaims, “Well, y’all still here!” She declares excitedly, “As long as I can always stop in and get some of that delicious creamed corn, you always got a patron!”

“And they’ll have to pry that spatula from my cold, dead hands!” George yells behind them, as they turn to leave.

Waving off their last patrons, Louise smirks graciously, “We appreciate both of you guys. We really do. Take care now.”

George squeezes next to her, grabbing her waist to pull her into an embrace and presses a kiss upon her temple. He extends a hand, beckoning her toward the center table, now adorned with a single rose and candle stick. He gestures to an amazed Louise to take a seat as he pours her a glass of Sauvignon Blanc and Maker’s Mark for himself. He strides over to the vintage jukebox in the corner, and a soft jazz singer suddenly coos throughout the restaurant. Louise rests her head upon her hands as she admires her husband strutting over to her.

“May I have this dance, milady?” he asks.

She giggles, “I don’t know, Sir. What would my husband think?”

“I don’t know, but one dance wouldn’t hurt him. He’s such a lucky fellow. I’m sure he wouldn’t mind sharing the wealth.” George jokes.

Louise stands to take his hand. She falls into his arms and nes-

tles her head against his chest, melting perfectly into his embrace.

This had become their nightly routine. Sharing a candlelight dinner after a full day of catering to others. Her heart was full because of it. Tonight was a picture-perfect moment. If it all ended today, she couldn’t have asked for a better memory.

Louise glances around the room with tear-filled eyes, “You know… one of the most intimate things you can do with a person is share a meal. That was my favorite thing to do with George,” she giggled. “Whether we were staying in or going out, we just enjoyed spending that time together. We’d spend hours at a time, just searching for new recipes to try. Then, we’d go out and scavenge for ingredients. Fussing throughout the store over which brand of butter was better or which thing needed tweaking.

We’d stop by the liquor store because, of course, there were drinks involved. That man loves him a good bourbon.” She grinned and shook away a distant memory. “Then, we would dance around the kitchen while we were cooking and laugh about everything under the sun. I can’t tell you how many times we burned something up because we were too wrapped up in each other.” Janelle continued stirring the sweet potatoes and brown sugar mixture as she watched her mom drift off into memories. “And our nights out were even better. We just loved food, you know? We kept a list of restaurants we wanted to try. Then, every single week, we’d choose one at random. I’d get all dolled up in my sexiest dress—”

“Alright, now!” Lucille called from the other room.

“Your dad would put on one of his date night polos. My favorite was the black. Mmm. I loved it when that man was dressed all in black.”

“It didn’t even matter the restaurant. It could be the fanciest place or a regular ‘ole chicken joint. We’d still get dressed up for each other. And I swear we’d order everything on the menu. Just a hodgepodge of whatever they offered. Plus, drinks, of course.” Everyone

snickered. “Then, we’d swap plates back and forth, tasting a little bit of everything. Feeding each other.” A smirk spread across her face. “That’s why we opened this place, Rhythm & Roots. Because your father and I just loved to eat. And we’d cut a rug no matter where we were.” Louise drifted off into the distance.

“God, I miss that man,” she said. “I know, Mommy,” said Lucille softly as she joined them.

Michael followed, “We miss him too.”

Slowly, they inched closer, and she welcomed their embrace.

“I wish he could see all three of you together like this. Your dad loved you so much. More than anything, he wanted you guys to take over all of this.”

“That would’ve been good, except Lucy can’t cook to save her life,” Janelle joked.

“Oh, whatever!” said Lucille, flicking flour at her baby sister.

“Remember when we were little,” started Michael, “and we used to make breakfast on Sunday mornings? Lucy would go in there, call herself tryna help and we’d end up with soggy, lumpy grits…”

“Yeah, or she’d dump too much sugar in ‘em. Grits tasted like they were straight outta a candy factory,” said Janelle.

Pointing a finger at her siblings, Lucille yelled, “Hey! Y’all can get off of me. I was just trying to help.”

“Yeah, help send them to the hospital.” Louise laughed. “I remember your dad and I coming back in the kitchen trying to clean up behind y’all butts. He’d have to make the entire meal all over.”

Jazz music played in the background as they basked in memories. The room stilled as Louise spoke, “Too bad we have to sell this place.” A look of confusion graced the faces of each child.

“Sell it? Mom, what do you mean?” asked Michael.

Louise sat with a stoic look on her face.

“Mommy… say something,” coaxed Lucille.

She cleared her throat. “I’ve decided that it’s time to retire. I can’t do this on my own. Not without your father.”

“But Ma, you have us,” said Janelle.

“You guys have your own lives. Your own families to take care of. You don’t have time to watch over an old lady and a restaurant. Besides, if you did, you’d have been here a lot sooner.”

Lucille shook her head, determination in her voice. “Momma, you don’t have to do this alone. You’ve done enough for us. It’s our turn now.”

Michael looked at his sisters and nodded. “We’ve talked about it before, haven’t we? We’d always said we would step in when the time came. I can take over the business side of things. You know I’ve got the experience.”

Janelle chimed in, “And I can handle the cooking. Dad taught me enough to keep this place running, even if Lucy just sticks to pouring drinks.”

Lucille threw up her hands in playful defeat. “Okay, fine! I’ll leave the cooking to you, but I can help with everything else. Plus, you’re gonna need someone to keep this place lively.”

Louise’s eyes softened, her resolve weakening. “I don’t want to be a burden on y’all.”

Lucille moved closer, gently placing a hand on her mother’s. “Momma, you’re not a burden. You’ve always been the glue holding us together. Now let us hold you.”

Janelle squeezed her mom’s hand. “Besides, we could never let go of what you and Daddy built here. This place is home. Not just to us, but to our whole community. Dad was always talking about the need for more Black-owned businesses. We can’t let go of this one.”

Michael added, “We’ll make it work, Mom. We’ll figure it out, together.”

Louise wiped a tear from her eye and nodded, a small smile

creeping across her face. “You kids are something else.”

“Of course we are. You raised us,” said Janelle with a wink. They all shared a quiet moment, letting the weight of the decision settle in.

“So,” Michael started, “how about we make this place our project? All three of us, just like when we were kids—soggy grits and all.”

Lucille laughed. “I promise, no more candy-flavored grits.”

Louise chuckled softly. “Alright. If you’re all serious, we’ll keep Rhythm & Roots.”

Janelle grinned. “Good, because we’ve already got a long list of new recipes to try.”

Louise looked around at her children, feeling a deep sense of peace for the first time in a long while. “Your father would be so proud of you.”

The family embraced once more, the warmth of their shared memories filling the room. The soft jazz in the background continued to play, a comforting reminder of George’s spirit and love that would forever be rooted in their family and in Rhythm & Roots.

Mark Underwood on Flying by Brandon Underwoood

Hurricane Gilbert

by Vinnette Gibson

Hi Gilbert. Remember me?

I was there when you came on that dark September day. Uninvited and unwelcomed. We knew you were coming, and came you did, with a bang. We waited in anticipation and dread, gathering supplies and securing our homes. Knowing that you were coming with danger and wrath.

You came with fury unmatched. You roared through our cities, towns, and country places, demonstrating dominance that you rule the land and seas, the boats and trees intimidating them into submission and tossing them about like toothpicks and feathers.

Great and mighty trees uprooted themselves and bowed at your will. You howled like a wolf, ripping roofs from houses, snatching signs from shops, powerlines from poles and awnings from houses.

You moved in a path like a great bulldozer, transforming the landscapes, washing away dreams. And though we prepared and readied ourselves, you came with a purpose to show your power and might. You tossed outdoor furniture, cars and trucks, and airplanes. You were just a bully showing your power, showing your might, commanding control, making bare our plight.

But why so angry, dear Gilbert? I know. It’s the way you were. Acting like a child, spoilt to the core, throwing a tumultuous tantrum.

But even as you raged, we still did not cower. We huddled for

refuge and prayed against your destruction. With minds cautious, but without fear and without sorrow. And finally, a few moments of relief. You roared, raged, and stormed but then you began to wane.

Oh, dear Gilbert, we got a breather. We dared to peek out and breathe a sigh, but you turned around, gave us a second dose. But that’s okay because we understood. Just as you came, you had to show yourself out.

You left our island. Your roars softened, turning to growls, then from growls to grumbles, and grumbles to whispers, then silence. We breathed a sigh. Relief. We made it. Slowly, one, and then another, we opened our doors and windows to survey. No electricity, no telephone, but that’s alright, for running water, we had, and coal burning stove we used. Pots and pans and food in cans stored aplenty for days to come.

But Gilbert, who knew? You gave us a surprise, for though unkind to some, you were generous to others. Like Robin Hood, you took from the rich and gave to the poor. “Look, look,” they bellowed with glee, “I have a new TV; Gilbert gave it to me. I have a new luxury car; Gilbert gave it to me. I have a satellite dish; Gilbert gave it to me. My new diamond ring, Gilbert gave it to me.” It doesn’t matter that you broke store windows and tore down their doors. Many people got goods that you gave them for free.

So, Gilbert, I was unhappy with your presence for a moment or two, but I guess I must thank you that spite is not your only flair. For though you brought apprehension to some, you showed generosity, gave fortune to others. We treasured the notion of $10 for a bottle of beer. Weeks of drinking beer for water, the joy of eating canned corned beef daily for weeks upon weeks. Are you rolling your one eye, Gilbert?

Such good pleasure, dear Gilbert, strengthening bonds, bringing family members together, replacing television and videos with each other. Who would have thought it, oh mighty Gilbert, even in your anger, when you brought prosperity to some, you added music, dance, comedy, and laughter to all our lives. That was a great reprieve for the

damage you’ve done.

But just because we’re not mad anymore, doesn’t mean we want to welcome you back, Gilbert. Don’t expect thanks for your generosity, Gilbert, for it is our character to look at the bad but appreciate the good. So, Gilbert, my good ol’ friend, now that we are happy again, and we remember your brilliance, if you ever plan to visit once more, we want you to remember just this one thing. Please don’t.

Fractured by Braden Potter

Who Shall Thee Look For?

by Shamori Thompson

One must seek out a friend to assist with a foe. To turn the tides of love and war for their home. Where their people work and room to roam, Living in peace never causes such a woe.

Wings above the peaceful sight, Lies a trouble like no other that shatters comprehension. One that grows and shrouds cities with blunder and tension. One that leads its victims to a dark light.

Yet, one must know who to seek out, In order to have assistance with such a scrimmage. One must understand that to seek one of such image, They must not hold themselves to doubt.

So, traveler, who shall thee look for?

Before the battle becomes a bloody war?

What’s at the Top

by Rebekah Jent

You grab onto the sharp rock, ignoring the bite of the stone into your chalked hands. Your chest aches, and your legs tremble as you rest. You begin to pull yourself up. The piece breaks in your hand and falls to the ground. You watch as it crashes down. Plink. Your breath hitches in your throat. The bottom is so far. Much farther than when you began. Is it only twenty-five feet tall? That should be nothing to you. You’re used to thirty and above, but that was indoor and not outdoor. Why did you decide to do this?

You’re not ready for this. Maybe you won’t ever be ready. Let go of the rock, you think to yourself. You need rest, and you can’t finish this.

Just as you are about to give up, familiar voices fill the air. Your friends! You forgot about them at the moment. You can do this! You’re so close! We’re so proud of you! Their shouting forces you to look up. Through the glare of the sun, you see them waiting for you. Not just waiting but hoping you will succeed. You catch their encouraging smiles and coaxing hand motions. You can do this. For them and for yourself.

You grip a new piece and test its strength. It will hold. You can do this. You pull yourself up above. Your arms scream in pain, but you can’t give up now. The rope holding you shifts by the movement. Your foot slips off the ledge. You stumble to hold on. It catches on a stone below your waist. You’re trapped until you move. You glance up. Three moves left. You breathe, even as your hands sweat and your body shakes. You can do this.

Your right hand rubs against the stone, looking for an edge. It locks around one right below the top of the hillside. You can almost touch your friends. Their shouts of encouragement win against the growing rush of wind in your ears. You’re so close to the end. You can do this.

Fighting against your natural judgment, you push your body upward. Your other leg finds a cranny large enough for your foot to step on. One more move, and you can grab the outstretched hands of your friends. This is the end. Starting over is not an option. Not when you’re this close.

Slick with sweat, your hand loses its grip on the ledge. You’re going to fall. You catch yourself at the last moment, crying out in relief. You must not fall. The rocks protrude out more here than at the bottom. Most people don’t make it all the way up. You’re special. You’re different. You can do this.

This motivates you for the final push. Your other hand stretches forward. You can almost latch on to your friend’s hand. Push. Push. Your fingertips brush the open palm. Come on. You can do this. You strain your body just a little bit more. Almost.

There! Your friend grips your tired hand, and everyone pulls you up. You barely notice the jagged edges scratching through your clothes to your skin. You don’t care. You made it to the top.

Your friends embrace you in a tight group hug. You lean on them, completely exhausted. They let you go after a while, and you collapse on the ground. The harsh winds freeze your wet skin, while rocks stab your back and legs. Could we just stay here a little longer? You breathe.

Take your time. We’ll stay here however long you need. Your friends sit beside you.

Chapter ii

The Discomfort of Not Knowing

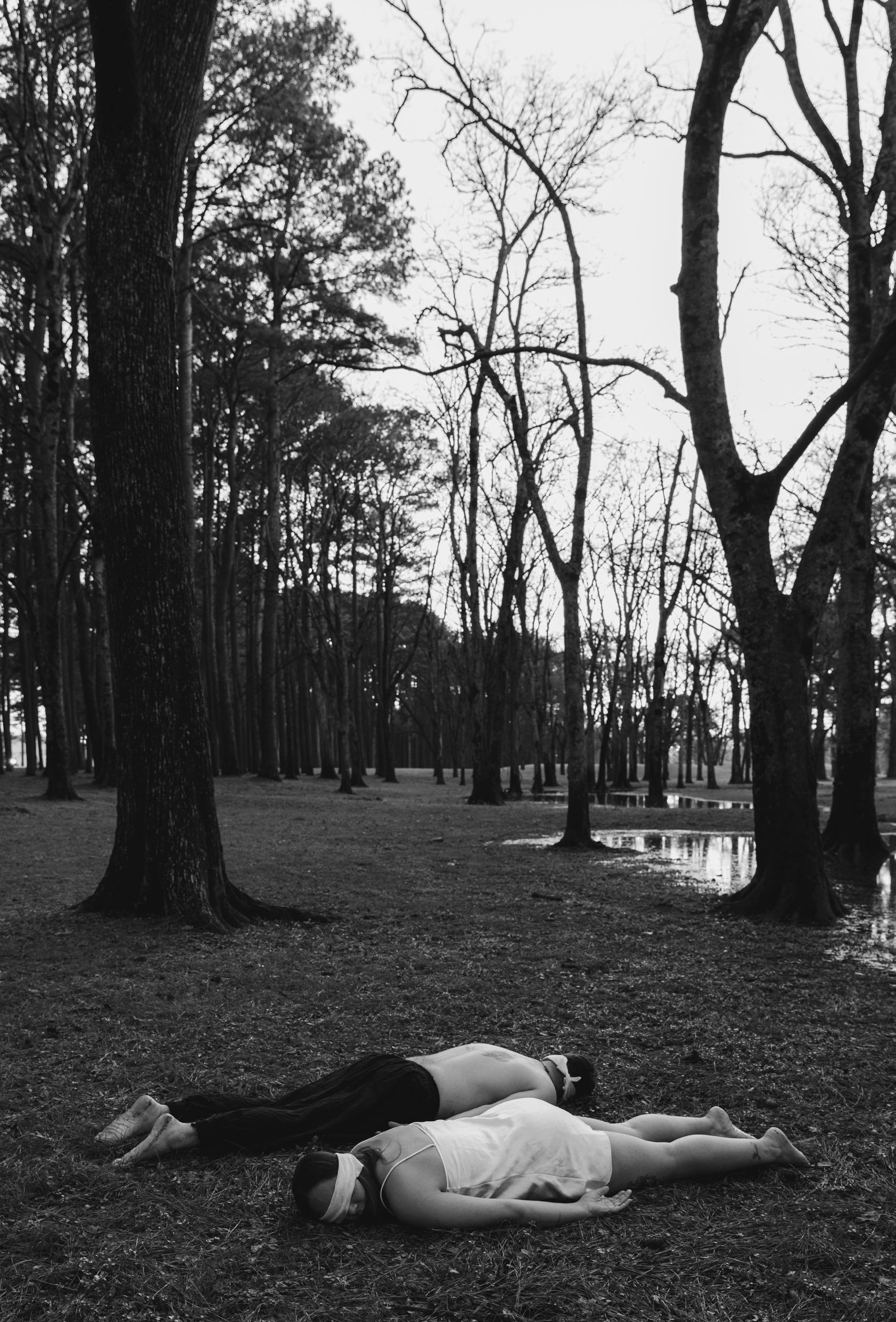

Sightless Reverie by Kaitilyn Jacobs

Cast of the Dice

by John Stevens

I reached to touch his shoulder,

A hastily made pencil sketch of a man.

A picture sat on the ledge by the window;

Handsome, dress blues, WWII, I guess.

Dark wavy hair and a broad smile,

Now, the disappearing shadow of the man lies before me.

His wife sat at the bedside chair leaning

To catch every breath

As if a lover’s kiss.

A worn Bible on her lap

Mementos of their love

Marking out the passages.

His dimming eyes shifted away from her

As I touched his shoulder.

A once muscular arm struggled to reach out

And stroke my forearm.

I glanced up at the IV fluids running into tired veins.

He mouthed incomprehensible words.

My hand on top of his.

The skin paper-thin and torn.

A

plumber?

A devoted father?

A leader of his community?

Inconsequential at this moment.

Tears welled in his wife’s eyes

Revealing an odd combination of denial and acceptance.

Emotions shaken

Like the toss of dice

Cast a lifetime ago

With numbers now revealed.

eurydice

by Dylan Keffer

my dearest, I have not forgotten you I grieve at the mere thought of you everything reminds me of you the sun’s warmth mimics your body’s heat pressed against mine and sparkling gems try their best to capture the beauty of your light emerald eyes yet, they cannot do it justice nothing could ever compare to you, my dear

I wait for the sweet sting of death to finally see you once again to hold you and never let go my dearest without you, this world could never be home

Veiled Perception by Kaitilyn Jacobs

Galaxies in Everyday Still Life

by Charles Michelson

I

Maybe every drop

Is a tear

But it holds within it

The stardust DNA of the Ancestors

Which have become infinitely Beautiful now

II

Days of you have slowly faded by

As though it is coming into clarity

A more well-rendered picture in the Darkroom

With the arm around me

Its moment burned like a flat iron

III

Coltrane is playing his sax

And I look out a window with tint

Of aqua and gray as water runs down

Catching up with earth

But oh, your whispers still fill the room

To Be Mortal by Lacey Gross

Goatee

by Natalie Franks

Don’t trust men with goatees.

I have heard it recently from the movie The Invitation, And it has been alluded to in poetry. There is something oddly foreboding about a man who wears a goatee with pride.

But,

What about before they grow the goatee? He didn’t have a goatee when we were younger. We were children.

But, He was old enough to know. I was 4, My sister was 6, I believe he was 10, But he could have been younger, Older than us, though.

Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe he didn’t know better.

But, The things we had to do felt wrong to me.

I was only 4.

Our family acts like it didn’t happen. Did it?

Do they know?

I don’t know anymore.

I constantly double-checked with my sister to ensure it wasn’t my imagination.

I’m angry.

He didn’t have a goatee then, But he grew one.

I still stay away from him,

Even though that was years ago. He hasn’t done anything since we moved away.

But still,

I don’t trust men with goatees.

Rekindling

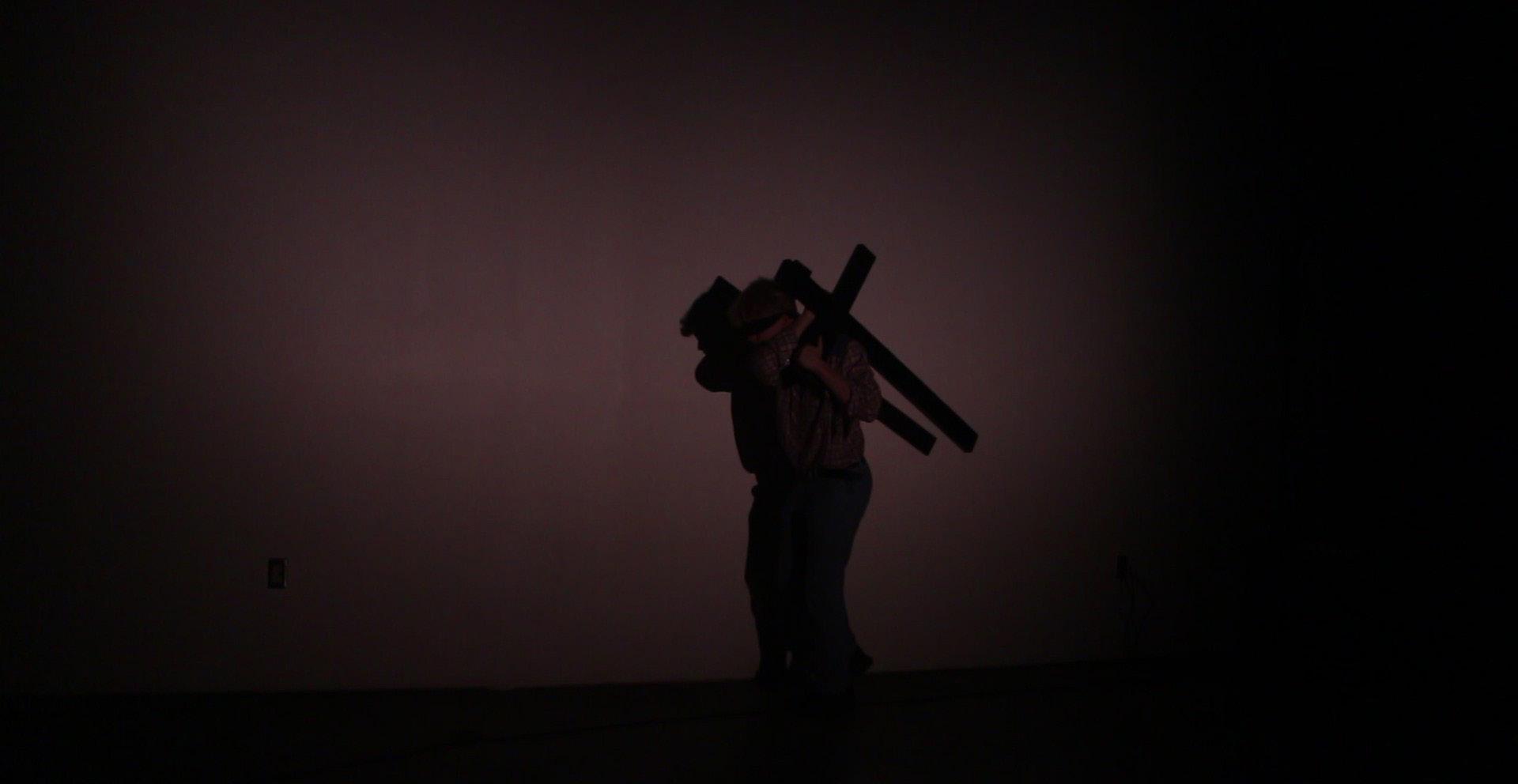

by Dylan Keffer

the pastor looks into my fifteen-year-old eyes and prays as his hand touches my forehead. church. extend your hands to pray for this man who God is telling me that he will lead nations to the light of your kingdom. favor and blessings. let him be baptized and renewed in your Holy Spirit. do not let him waver but let him walk the straight and narrow path as you intended. glory to glory. this young man has a fire within him that cannot be quenched. the double portion of Elisha is upon him. Lord, we thank you for what you are doing for your people! and we thank you for this young man’s life! amen.

I sit and reflect years later. if only the wick of my candle would still burn as it did in my youth. I used to be excited about going to church, but now I oversleep because of work. the stress of life is so overwhelming that it hurts. depression is knocking at my door and God is quiet. He is still and I am questioning if He really is real. it is hard to light a candle when the weight of wax is hiding the spark of rekindling. the weight of all of this. pastor, where did I go wrong? what did I miss?

Almost Cut My Hair by Brandon Underwood

Dirt of Decay

by Jason Armstrong

The rolling hills surrounding the house now sprout trees and weeds instead of the previous century’s acres upon acres of fertile crops that fed both the plantation itself as well as the community around it. Behind a few groups of messy, unkempt bushes, one can barely make out the creaky, wrap-around porch lurking behind, slumping and peeling away from the house in a few areas. You might not expect Georgia high school legend and former All-American wide receiver, Charles ‘Speedy Cholly’ Jones, to be sitting in the dimly lit family room, looking out crusty, dirt-caked windows, drowning his sorrows in Wild Turkey. Cholly’s lifted ¾-ton diesel truck sits at the head of the long driveway, next to the rundown family house. Although the truck’s paint faded years ago, the engine runs far better than the new ones coming off the assembly line. Those four oversized tires form the base of Cholly’s own welding business, his latest career path since finishing college. This job and the derelict property around him are his only meaningful possessions, as his family has been gone for a few years now. The small inheritance was barely enough for him to cover the final semester of school.

This land has been in the Jones family for longer than even his parents could remember. Sitting on his father’s lap while he rode the tractor and mowed the endless rows or running through the acres— probably where he developed the speed that brought him his own little taste of gridiron fame—until his feet blistered, and climbing through, in, around, and over the various buildings and rusty pieces of equipment, this former Yellow Jacket does feel somewhat tied to this ground, regardless of its current state.

Cholly drinks a good bit more whiskey these days. Though he remains at the homestead, the only home he has ever known, he has more or less given up on making a go of the adjacent farm and is torn over selling his family acreage altogether, especially now that his entire family has all passed, and putting that money down to buy a new place closer to Atlanta for a corporate job, versus keeping his old place and struggling to get by.

Bourbon and brunettes are his only real weaknesses, the former is much less costly than the latter if you were to ask him, but it is only after a few shots that he can muster the courage to log into the dating apps he otherwise shuns when level-headed. Swallowing a few doses of liquid courage, Cholly swipes left and right and eventually settles on a sophisticated-looking blonde named Janice. 5’10’’, smallframed glasses, a former Division 1 volleyball player with a Masters in social work. He sends her a message and, not realizing her icon is green, is surprised by her quick reply. She lives in an ATL suburb and invites him out to a bar halfway between them.

One more shot for the road and Cholly heads out, not bothering to lock up the old house. Climbing up into his truck, he is pleasantly surprised by the handful of light-colored pheasants taking off from his lawn as he cranks up the loud turbocharged diesel. He heads down the driveway and leaves town on his way to the hastily scheduled date, taking the beautiful birds as a good omen for the night ahead.

Passing under the trees that connect overhead, his radio turns up on a country tune, he is a few miles down the country road when he sees Miss Molly on the roadside and pulls over. Although it will put him behind schedule, what are neighbors for? She has broken down on the side of the old country road and is struggling to fix her rig. Cholly peeks under her hood and realizes she is not going anywhere without first replacing the broken belt. Fortunately for her, she already dropped off all her horses and their big gooseneck back at her ranch before heading back out, so Cholly agrees to tow her old dually to his garage with his own truck and to swing by the parts store on their way

there.

Once they hitch up Molly’s truck, they turn around and head down the road. Cholly thought she might be interested in his recent find and told her first about tilling up an old musket action a few weeks back. When she shows no surprise, he goes on to tell her he is considering selling his old place, but Miss Molly is again not surprised.

“There is a lot more than that old gun part buried across that land of yours,” she says, “and you are not the first Jones to try and rid yourself of the property.”

She continues, starting in on the sordid history of the property from the late 1700s through the early 1900s, beginning with slaves working the originally rock-strewn fields, continuing through a pair of brutal, bloody Civil War battles. When she finally gets through her tales, culminated by her saying there were more than a few disappearances over the years, he was even more shocked to hear about the appearances, corpses, and partial bodily refuse being disgorged from the earth, seemingly being excreted by the past into the present. She mentions there are even rumors that the sinkholes on his property are rumored to connect to the North Wolf Island Harbor, a seaport that previously hosted slave ships, but that has since become a large modern seaport bustling with international trade activity; it stands just a handful of miles or so away from this very spot.

Miss Molly takes a deep breath as they pull past the faded wooden fence and continue past the freshly mowed half-acre of lawn leading up to the dilapidated two-story house.

“It has been years since I last saw this place. Can’t say as I approve of the lack of upkeep,” she advises.

The house itself is in dire need of paint, shutters dangling from the sides of the windows, half of which are broken or missing altogether. Out past the house, decaying carts, really nothing more than rusted axles and frames mixed with a few pieces of rotten wood, failed animal pens, and a long-collapsed slave quarters, show some of the history of

the place if one were inclined to look, including its time where his ancestors made a go of running the back plots for a few decades during and immediately after Reconstruction.

Pulling into the barn, he stops the truck, hops out, and nods at the back porch, where Miss Molly heads up to the back porch and flops onto the old couch. It only takes about twenty minutes to swap the belt, start the truck, and then ensure the battery is properly charging. Miss Molly is over his shoulder as he unclips the jumper cables. She thanks him, smiles, and proffers up a twenty-dollar bill, which he promptly refuses before she climbs into her cab, backs the truck out, and heads down the long driveway.

Dripping sweat from working in the sweltering barn, Cholly washes up and pops a top on a fresh beer. It is now pretty late, so he texts Janice, apologizing that he will not be able to make the trip after all. Instead, he grabs a pair of cold spare beers and then climbs up onto his old tractor next to the barn and sets them into his ‘custom’ two-cup cup holder. He starts up the reliable old diesel engine of his late-50s tractor. Its faded red paint always reminds him of his father, who died at just age 42, when Cholly was only 14 years old. His father collapsed after working one too many 14-hour days on this farm. He puts along, out past the well-worn path and among the overgrown crop rows. A handful of sinkholes dot the perimeter of the property, most of them on the country paths now overgrown with weeds. The property goes on for quite a ways, the back couple of acres ringing a murky pond, its depths covering maybe a quarter-acre in total area.

An hour later, he winds up at the old swamp in the back, where he grabs his old cane pole that has been cached in the same spot since he was five, tosses it out and cracks the top on his last beer, then sits down on a flat oak stump, kicking his feet up on a chunk of firewood. The pond is isolated and has an infrequent stream of foul-smelling bubbles, likely sulfurous in nature and byproducts of decades of sloughed pine needles mixed with agricultural run-off. A dark red clay rim forms its banks; nothing seems to have happened here in quite some time—oth-

er than regiments of mosquitoes living and dying.

Tucking his jacket behind his head and enjoying the last of his final beer, Cholly’s eyes start to close as he stares at the red eyes of a large possum eyeing him from across the opposite shore of the pond, maybe 50-60 yards away. He dreams of a new life in a new city with a new girlfriend, his old life far behind, but is instead awakened by a half-dozen squawking crows.

He slowly rises from his slumber and goes to head home, but, in the dark, trips on his way to the parked tractor. Looking down, he sees the twilight sparkling off the white of an adult skull, a fist-sized hole disturbing its back half. Stumbling back, he gains his composure, heads back to his tractor, and mashes its accelerator until he reaches the safety of his house. He calls Miss Molly first thing in the morning. After telling her that he found something strange out by the pond yesterday, she advises him that the library will have a bit more information. Cholly grabs his keys and heads off, stopping only for fuel and take-out on his way out.

After a day spent sifting through old library records, Cholly has learned that human remains seem to bubble onto the red clay bank every decade or two going back at least a century, where the local library’s records seem to end. He also learns more about the nearby harbor and its network of tunnels. These tunnels may or may not connect to his own plot of land, sufficiently piquing his interest, such that he heads back out to his truck and drives the few miles down the road to visit the harbor, where he immediately sees foreign cargo ships now flooding into the same ports occupied by slave ships a century and a half prior, their imported goods trucked across the long-since pavedover auction blocks.

The massive docks welcoming these ships are surrounded by considerably thick concrete walls, but out a few hundred yards beyond the wall boundaries, just before the channel opens up and starts giving rise to the jetties defining the end of the harbor, you can still see the muddy banks of the original port. There are a few small holes in these

banks, each not much larger than the size of a tortoise den, where folks used to sneak and smuggle through the underground passageways beneath. Though most of these tunnels have collapsed, the holes still visible are clearly marked with permanent ‘Stay Out’ signs, their steel posts mounted in concrete, for whatever purpose these signs might serve.

A state-of-the-art recreational park sports safe, kid-friendly playgrounds with padded equipment and cushioned bounce pits has replaced the horrific site from a century ago, where kidnapped people were once auctioned to the highest bidder. The holding pens were replaced by a series of businesses, most recently an ice cream stand offering dozens of different flavors. There are many roads heading inland from the seaport into the great state of Georgia, many of them multi-lane highways, but the oldest path now appears as only a pair of parallel deer trails. Though wagons carved the path a long time ago, only the ATVers prevent Mother Nature from completely covering it back over. A small sign designates the historical marker, which is located about twenty yards into the little trail, and designates the location as the entrance to the ‘Great Port of North Wolf Island,’ once the largest seaport in Georgia.

Cholly looks down at the sign and walks a few yards down the path. Looking further into the trail, he sees overgrowth, lots of red clay, and a few gigantic puddles, indicating it is likely swampland and therefore probably full of mosquitoes. Peering down into the closest puddle, Cholly sees the water is murky and the soil around it dark and sticky. Looking closer, he finds a chipmunk that did not make it out and apparently became something’s lunch.

“Enough adventure for a day, I have plenty of this nonsense at home,” he thinks before heading back to his truck.

Feeling a bit guilty for having missed their date the night before, he decides to seek forgiveness and calls Janice. He can tell from her voice that she is a bit disappointed at being blown off the night before. Cholly mentions helping his older neighbor, who was otherwise stranded, and quickly charms Janice into agreeing to meet up at

a local waterside bar twenty minutes away. Having been there many times during his playing days, he leverages its smaller-than-regulation volleyball net as a convenient hook to seal the deal.

Cholly drives his truck out of the harbor facility and merges onto the interstate. It is a smooth drive, at least as much as it can be for a crowded highway, and he pulls into a parking lot a half-hour later. After requesting an outside table from the hostess, he freshens up in the bathroom and grabs a beer while waiting for Janice to arrive. Ordering a second beer, he sees her car pulling into the lot in the open spot next to his truck and orders one for her as well.

Janice sees him sitting there on the balcony and walks up the steps, flashing him a big smile, and leans in for a hug. They sit down, order an appetizer, and start chatting, regaling each other with their respective day’s events. While Janice has been primarily focused on work and tells of the heart-breaking stories about foster kids, Cholly is drawn in by her giant heart. She seems to care for each of these kids as if they were her own. Feeling foolish, as his story suddenly seems far less important, he recounts his days working on the farm and seeing the harbor earlier in the day, though he leaves out the bit about the half-eaten chipmunk. Agreeing to split a large sampler platter, the next thirty minutes’ conversation makes the time disappear. It has been over a year since his last real relationship, and Cholly cannot seem to keep himself from staring into her gorgeous green eyes, dreading the minute the check ends their date. Their waiter appears and hovers over Janie’s shoulder just five minutes later. Cholly picks up their check and walks Janice out to their vehicles. Not anticipating the awkward goodbye with her, especially with them being parked side-by-side, Cholly is surprised when she leans in, kisses him warmly on the mouth, and then opens her own door and drives away, leaving him standing there wanting more.

Two dates on and Janice asks him about where he lives. She wants to see his place, so invites her over the next night. She pulls up the driveway and sees him sipping a beer on the porch. He offers her

one and after an hour of talking and drinking a few more beers each, she asks him to walk her around and show her the farm. They walk hand-in-hand for about a quarter mile before she has seen enough, the growing darkness and rustling in the bushes telling her it might be a good time to go. After they head back to the house, Janice mentions having to be up early for work, thanks him, and serves up a passionate kiss before heading over to her own truck.

Cholly wakes up at a reasonable hour the next morning and starts towing the mower deck around to knock down the highest weeds. After the lawn is finished, he starts repairing the shutters and finally adjusts the squeaky front door that had been torturing his ears for longer than he cares to admit. With Janice busy until the weekend, he plans to spend the next few days scraping, sawing, painting, and hammering whenever he is not out on a job. He is disappointed when she does not call or text him all night, but figures maybe she had something come up. When it continues through the next two days, he becomes concerned that she is not answering his calls or texts but, not knowing her friends or her address, tries to contact her through the dating app to no avail.

He eventually grows annoyed at Janice, figuring she probably moved on after seeing his crumbling house and rundown farm. He gives up on all the messages, texts, and calls and sends a final pleading email, hoping to hear back from her. His cute blonde has seemingly disappeared without notice. When it grows beyond a week without word from her, his hope finally fades away.

Without a date or any work scheduled, Cholly continues fixing up the house before he turns to the fields. He spends the next two weeks tilling, mowing, and cutting well into the twilight hours. It unfortunately seems that every issue mended results in a few new ones to fix. Like his father before him, Cholly continues to plod on, riding his tractor in long lines, back and forth across the near plots. When he finally gets these rows under control, he turns his efforts to the back plots. Straightening the house at night and in the early morning and

farming the rest of his waking hours, Cholly feels a renewed vigor he has not felt since his college days.

Working, then working, and working still more, he gives up on dating, at least for the short term, having grown disgusted over the last dating experience, and focuses only on the property. The house, though still spartan, has become quite livable and solid against the outside world, the near plots now looking presentable. Happy with his progress to date and with the fridge stocked full of groceries, Cholly takes the night off from his toils and pours himself a celebratory whiskey, the bourbon a solitary party to toast his progress. After a few bourbons, Cholly starts up his old tractor, climbs up, and begins meandering around the farm’s periphery. Deep in thought, he drives and drives until he sees the fuel gauge reading beneath a half-tank. Feeling the sudden urge to urinate, he pulls over at the pond and relieves himself next to an old live oak. He is suddenly overcome with exhaustion and feels drowsy, needing to sit down and rest for a minute.

Feeling himself falling, Cholly awakes submerged in mud. Blind, choking, and struggling for his feet, he paddles his legs and flails his arms until he bumps up against something solid. Gripping it with both hands, he finds that it is a thick tree root, which he uses to pull himself from the wet earth and slide onto firmer dirt. It is so tight that he cannot stand up, and he can barely crawl. Almost like being born, the red clay womb nearly drowned the life from him. Gaining his breath, Cholly clears the mud from his eyes and looks out to see darkness. It takes several minutes for his eyes to adjust to the near-blackness. Calling out for help, he is answered by his own garbled voice, trapped in an echo chamber of mud. The sour, damp air leads him to understand that he is underground.

Feeling his way along the walls, Cholly scoots and pulls and slides and eventually crawls. He works for several hours before coming into a larger opening, more of a main passageway. Standing up, he reaches all around and feels nothing but more mud. Dripping and slippery, Cholly shuffles along, pushing his body up to and then past

physical exhaustion. He passes out a few times and awakens each time with a start, then plods on even further. Cholly pushes through pain, exerting everything he has, and, just before passing again, he screams out, “Hello! Can anyone hear me?” but no answer comes.

Cholly falls against the wet clay wall, trying but failing to ward off sleep, and feels something solid by his hand. Pulling it out of the mud, he moves it around and looks at it for a few long seconds before realizing it is a human femur. Just before closing his eyes, he vows not to die in the tunnel like those before him.

Knowing he is gone, Miss Molly walks up to the door, calling out for anyone who might be inside; appearances matter after all. Glad for the sufficient silence, she proceeds back to the fields, slowly trekking through the rows. On and on she walks, going eventually on to the back lots and through the trees, onto banks of the pond. There, she looks down the bank and pleasantly smiles, happily observing the scene before her: claw marks tracing from the bank down to the edge of the pond, ten laser-straight lines in the sand, about the same width apart of the spacing between Cholly’s fingers. Twenty yards or so from the lines sits a partially decomposed female body, a wet line of dirty blonde hair trailing back toward the water’s edge, just another friendly gift from the pond. Beaming, Miss Molly scratches out the lines and nudges the body back into the water with her heeled boot. Satisfied with her work, she turns and heads back up the bank and begins her long walk back to the house. She makes her way up the steps and sits down on the same couch she had occupied just a week or two earlier and pours herself a tall glass of Cholly’s bourbon. Enjoying the burn, Miss Molly is thrilled that she can now inhabit the Jones’ land without interference, as Cholly was taking far too long for her liking. She lifts her glass and nods toward the old swamp, “A toast to you, Cholly. The place does not look too bad, but I am glad to be home, back where we belong.” The sun sets, and the whole moon shines bright, its light decaying in the pond’s waters.

At the same time, and just a few yards beneath, Cholly opens

his reddened eyes and struggles ahead, pushing through the mud and slowly but surely moving toward the source of the light.

Menace Explores His Surroundings by Brandon Underwood

The Wanderer

by Toxey Chance

My name doesn’t matter

I’d forgotten it after so long

Years spent wandering

Searching for a place to belong

Going from here to there

Riding the rails

Never staying long

Always hoping

That one day

I’d finally belong

Yet

As the years wear on

As I travel alone

I fear I’ll always be on my own

But as the years drag on

As I grow old and start to gray

As the seasons wear on

I will carry on

Always looking For a place to belong

Where I’ll never be alone

A place where I’ll belong

Superstition by Kaitilyn Jacobs

Salt Six Feet Under

by Mark Smith

I stand with one foot between the devil and a brutal grave

Drunk on blackberry moonshine with feet dangling off the cliff edge

I feel smaller than a pebble thrown into the grey sea foam

I feel tired, torn, weary, worn...

The harsh waves slam against the rock as winds increase even more

Everything feels cold as the chilly gusts sting my face and hands

Feeling sharp, stinging like her hands

Dark clouds conceal the angry sky

I consider diving, down into the depths below

Deep into the midst of the saline sea, pure instant peace

From this height, the water would hit like concrete

It would all be over

I will die in the darkness, the icy abyss below

I hear my mother’s voice; she is calling me back home

But I wonder as the thunder cracks and the storm builds

If this cliff is safer than my mother’s embrace

When can I close my eyes and rest?

When can I feel the calm of the fall?

Bowl from My Kitchen by Brandon Underwood

The Storm

by Leah Littrell

The storm is coming. The sky darkens as the wind howls. The man is chopping wood for the fire. It’s getting colder, so his hands are burning with each swing of the axe. His back starts to ache as he lifts the axe over his head and slams it back down into the wood. He’s running out of time. He picks up the next piece of wood and puts it on the block. Sweat starts to bead on his eyebrows, then runs down his face as he swings. His legs ache as he bends over and picks up another piece of wood. He swings the axe once again over his head and into the wood. He feels a sharp pain in his hand. He looks down, grabs the splinter, and pulls it out. He wipes the blood on his pants and picks up another piece of wood. Hopefully, he’ll soon have enough to keep him warm. A few more pieces, and he can relax. His body burns as he cuts through these last pieces. As the last slice of wood hits the ground, his shoulders slump in relief. One task is done. He moves to the next project required for his survival. His weary legs ache as he bends over to pick up the wood. If only he had gotten a new wheelbarrow when he had the chance. The red one propped against the side of his shed won’t do with the rusted-out hole in the middle. If only he had prepared better. He quickly cuts off this line of thinking. Now is not the time for regrets. Now is the time for action. He must keep moving if he wants to survive. He carries the wood armful at a time into his cabin. Worry creeps into his chest each time he steps back outside and sees the sky a little darker. After he carries the last pieces of wood into the house, the man jogs out to his shed to grab the brown canvas tarp, along with nails and a hammer. He must cover as much of his cabin as he can. If only

he had patched these holes in the summer. No! No regrets. Only steps forward. Pinning the tarp against the cracked frame of his window, he starts pounding at the nail stuck in the wood. Over and over again, he swings. The wind beats against his back as the tarp is thrown wildly in the wind. When he feels the first snowflake on his skin, he knows that he has run out of time. The man slams the last nail into the wood and retreats into the house just as the barrage of icy snow hits the front door. Lighting his lantern, he looks around at his meager belongings and prays that he has enough food and supplies to keep him alive. It has to be enough. The storm is here.

Pg. 63

Forest in a Storm by Eli Rainey

L&S Spotlight

Poet Ashley Massey

Ashley Massey is a fourth-generation cattle farmer managing a small herd and land in beautiful Middle Tennessee, an entrepreneur with a successful indie jewelry brand offered online and in retail stores nationally and internationally, and a poet with publications in Beyond Words Magazine, Untelling Magazine, and The Red Branch Review. She is also the founder of a menstrual equity organization. She has worked as an instructor in the University of North Alabama’s Restorative Justice program held at Limestone Correctional Facility. She has additionally taught a correspondence course to men on Alabama’s Death Row. Her academic research focuses on carceral representations in Southern literature. She is a published writer and has volunteered teaching creative writing in a Tennessee county jail. She is a graduate of the University of North Alabama (M.A. English: American Literature, B.A. English: Literature) and the former Critical Prison Studies graduate assistant.

Interview

What was your biggest influence to put this poetry collection together?

I see writing poetry as a way to keep memory. This book is essentially a scrapbook of many familial as well as personal memories distilled into poems. Besides memory keeping, this collection also serves as a way to write to and through death and to turn harms into poems. This book was developed during a time of experiencing intense grief as my father suddenly passed away in 2021, a year when so many others were also facing immense loss. In the year following my father’s death, I also experienced the deaths of other family members, close friends, and pets. The losses plagued me, and I spent the next two years in survival mode, constantly feeling anxious about whether or not the next phone call I would receive would be telling me someone else had passed. I thought that during that time I did not write at all, that I was purposely hiding from writing, afraid of what may be released. But as I began to organize some poems I had written in my early 20s, I found dozens of notes in my iPhone that I had jotted down during those initial months after my father passed. Those notes turned into new poems that greatly influenced my poetry collection, resulting in a work that shares not just the pain that comes from death, but the growth and resilience that comes after too.

What role do farm-related language and the idea of city vs. countryside play in your poetry?

I think about the duality of city vs. country quite often as I was raised in the country but quickly left for the city right after high school. After sev-

eral years of living away from home, I found myself visiting our family farm whenever I had a spare moment. I realized it was the place I was most myself, so I ended up moving back to the farm around the same time I transferred to UNA to finish my undergraduate degree. The poem “The Returning” deals with this theme of leaving for the city and then returning back home through the image of Canadian geese that return to our same muddy cow pond year after year. In returning to the earlier theme of memory keeping, in a way the language I use is also a way to collect and archive things I have heard and learned on the farm. I realize that farms are becoming scarcer by the day, with Tennessee in particular losing 10 acres of farmland every hour, which will amount to over a million acres lost by the year 2040. This book is my way of standing firm in preserving not just what I have heard and learned on the farm, but also the farm itself.

The three following poems are featured in Massey's collection "Keep the gate open."

Keep the gate open

by Ashley Massey

Time is swallowed whole by Death. He does not stop to chew.

When He came down our driveway, flanked by barbed-wire fences, He didn't stop to admire the porch you had just swept off.

Momma and me had to swim through the mud, had to get scraped and cut. We know what they don't. That the creek will still rise. While the town will still remain stagnant like a festering pond overcome with green scum.

But I am not from the town. I am from these forty acres. And I will keep the gate open like you told me to. I will keep the time. I will keep waiting on you.

About “Keep the gate open”

What is particular about “Keep the gate open” that made you title the book with that name and place it as the last poem?

When given the opportunity, I like to share about my reasoning for not capitalizing the title, even though I am usually a stickler for those type of things. I purposely did not capitalize the full title because I see it as not an end but a continuation, much like how I choose to see my father’s death as not an ending but a continuation of his legacy and our memories of him. When I helped my dad on the farm, he would often need me to open the gate for him as he made his way on the tractor into a pasture. When he would say “keep the gate open” to me, it was usually followed by another request like, “keep the gate open and watch that the cows don’t get out.” There is almost an invisible ellipsis to the title, showing that death can catch us when things are not done, when we aren’t quite finished yet, when we have just swept the porch off, when we still have work to do…

Death is capitalized as a proper noun, why did you choose to personify it?

I think in a way by personifying Death it takes some of its power away, making it more like a person, maybe more understandable and maybe even more likely to be disempowered and defeated.

Can the metaphor of the gate being open refer to Death coming into the house to take someone to their forever “home?”

I think the meaning of the gates could definitely have multiple interpretations for the reader. It could mean Heaven’s gate, a prison gate, or an old rusty gate on a farm.

Rusting Here

by Ashley Massey

I want to melt down Iron City. Let the metal pour down the streets. Let it cover me. Let me rust there, by the train tracks. Let me be.