LifeArk:

Disaster-Resilient Housing from Recycled Plastic and 100-year-old Technology

By Dawn Killough

When architect Charles Wee saw what passed as housing along the flood-prone Amazon River, it changed the trajectory of his career. Within a year, he founded a new firm called LifeArk, where he began developing a unique solution for durable, modular, disaster-resilient housing. The resulting design is resistant to fire, floats on water, provides excellent insulation, is seismically strong, and is made using 100-year-old technology and recycled plastic.

Image of the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Tohoku, Japan and LifeArk’s mission diagram

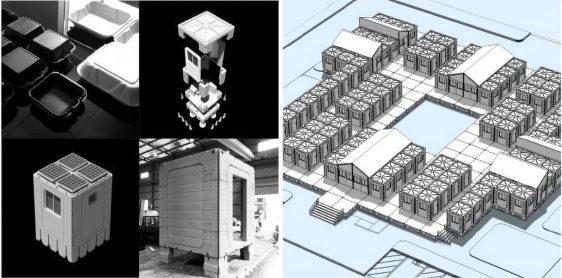

LifeArk Kit of parts diagrams and illustrative rendering

It all started in 2015, when Wee visited the area where Peru, Colombia, and Brazil meet in South America. His cousin, a missionary,

had asked Wee to visit to see if he could help the indigenous people living along the Amazon. The river floods annually to a height of 25 to

30 feet, and the people along it live in homes on stilts because they can’t afford to move to higher ground. “I asked myself, ‘What am I doing as

Left: Rotomolding machine in LifeArk factory in Madera CA. Right: Images of single raw modules, hardware, and molds

an architect?’ I saw an opportunity to do something about it, and the rest is history.”

His initial goal was to design a basic shelter that could float. He worked on a design for three to four years until he saw a picture of the aftermath of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan. The photo showed a mass of debris floating in water, including water and fish tanks that had been located

along the coast before the disaster. “They were the only thing that really survived the tsunami. I thought if someone had just crawled into one of them, they could have survived.”

A ’Cool’ Design

From that inspiration, Wee designed a unibody, plastic structure that’s built using rotational molding, the same process used to make water and agricultural tanks. Because

the technology is over 100 years old, factories specializing in this type of manufacturing are already established worldwide, particularly in developing countries, where this type of housing is most urgently needed.

Wee compares LifeArk’s housing units to Yeti coolers, as they are built similarly. A master mold is created for each piece, encompassing both the exterior and interior of the structure, with a hollow cavity

Image of a LifeArk floor coming out of the rotomolding machine in the LifeArk manufacturing factory in Madera, CA

between them for insulation. A plastic polymer is heated in a mold that rotates bi-axially inside a large oven to coat all sides. The cavity in each piece is then filled with polyurethane foam, much like a cooler. Each component takes 15 to 20 minutes to manufacture, has an R-value of 40, and includes molded slots and chases for wiring, plumbing, fire sprinklers, and other utilities.

The components are shipped from the rotomolding manufacturing facility to LifeArk’s Housing and Community Development (HCD)-certified assembly factory in Monrovia, California. There, the modules are assembled and packaged to ship. Once the modules arrive at the site, the site contractor completes the assembly and connects all the factory-completed modules to their designated

Images showing a fire test and structural test of LifeArk parts and a rendering of LifeArk home floating capability

Aerial drone image of LifeArk project in Azusa, CA “Azusa Resource Center” during onsite assembly

configuration, including making all necessary connections to the site’s infrastructure.

Structural connections are made using 2” x 2” steel tubes that are attached to the exterior of each unit and friction-fitted plates on the floor and roof. The unit base is also anchored to a concrete slab using expansion bolts and epoxy.

LifeArk units are inherently raised above grade creating a 28-inch crawl space underneath for utilities. Utilities are run on top of the concrete slab, through the crawlspace, and into each unit from there. No trenching or digging is required, and the units can be easily dismantled or relocated without impacting the site.

The plastic Wee uses is high-density polyethylene, similar to that used for

cutting boards, medical equipment, and plastic bags. He sources approximately 30% of the polymer from recycled plastic in Malaysia and is working to increase this amount. A recent project redirected 150,000 pounds of recycled plastic into a housing development.

Unmatched Performance

LifeArk’s units have been tested and certified to show their durability and

Images of LifeArk’s Tyler project in the city of El Monte, CA showing exteriors, interiors, and close ups

insulating properties. In long-range temperature tests, the units internally maintained a comfortable 68°F to 78°F while external temperatures ranged 21°F to 107°F. In California, units are required to have both air conditioning and heating according to the building code, but many residents find that they don’t use them much, instead relying on circulating fans that help keep the inside air circulating.

The units have been tested and certified by the International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials (IAPMO), one of two bodies that certify building materials in California. LifeArk is also certified by California’s Housing and Community Development’s Factory Built Housing and Commercial Modular Programs, making it compliant with International and California Building and Residential codes. The roof and exterior structure have also been certified as Class A for fire resistance (the highest level) and as meeting Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI) requirements, ensuring that the entire roof system (including underlayment and assembly) is compliant and creates a fire-safe zone around the structure.

They have also undergone structural testing, including cyclic testing equivalent to a 9.0 earthquake, and have been shown to withstand wind speeds of up to 200 miles per hour through finite element analysis. Wee believes it is one of the first housing units of its kind to be certified to withstand fire, flood, earthquake, and wind.

Cost-wise, the units average about half the cost of traditional construction, saving on both materials and labor. Owners also save on maintenance

costs, as the durability of the plastic structure requires little ongoing maintenance.

Meeting a Pressing Need

Despite entering the modular housing sector with a unique product that required almost seven years for certification, LifeArk has established itself as one of the leading providers of modular housing for California’s homeless housing market. They’ve completed a total of seven projects, from navigation centers to permanent supportive housing, with almost 200 beds across various sites in the state.

Their most recent project is an 88-unit permanent supportive housing project in Ventura County. The county is using $28 million it received from California’s Housing and Community Development Homekey+ program to construct the project, in partnership with Dignity Moves, a California non-profit developer, Swinerton, and operator Many Mansions.

They’re also wrapping up a project providing transitional housing for 34 homeless individuals in Watsonville, California. It’s a partnership between Santa Cruz County, Monterey County, Westview Presbyterian Church, and Dignity Moves. Swinerton is providing general contracting through its affordable housing division.

Image of the 4 bedroom congregant unit at the LifeArk Tyler project

The development is being built on an existing parking lot owned by the church and was challenging because it’s located within a 100-year FEMA

floodplain, requiring the structure to be elevated 36 inches above the plain. When the project began, the idea was to use another modular

Modular Building Solutions

product for housing; however, the cost to elevate the structure was nearly $1.5 million. The developer contacted LifeArk, knowing that their standard units are already 28 inches above grade. The cost to raise them an extra 8 inches with shims was just $50,000 extra, a significant savings.

The center is currently slated for removal and return to the church in five to ten years, making the trenchless utility system an ideal solution for this arrangement.

Something Different

Wee started his architectural career in 1985, working with well-known architect Tony Lumsden at DMJM

Eye level image of the interior courtyard area of LifeArk’s Midvale Project in Los Angeles Council District 5

Mendenhall), which is now AECOM. Wee and Lumsden then started their own firm and designed high-rises in Asia throughout the 1990s.

But when it came time to start LifeArk, Wee wanted something different. “I wanted LifeArk to be something that could help save lives, and maybe at the same time help the planet.” He believes that it will take “a different material and a different method” to address the affordable housing crisis and provide disaster relief housing on the scale it’s needed. Maybe he’s found it.

Dawn Killough is a freelance construction writer with over 25 years of experience working with construction companies, subcontractors and general contractors. Her published work can be found at www.dkilloughwriter.com.

Aerial image and eye level image of interior space during site assembly of LifeArk’s Watsonville Navigation Center Project in the City of Camarillo

Rendering of the 88 unit Lewis Homekey+ Permanent Supportive Housing Project in Ventura County, CA

Map of the Santa Rosa area and images of the town