2025 Liberal Arts Commencement

Thursday, May 8, 2025, 6pm Moody Center

Dean’s Message

This is the final issue of Life & Letters that we’ll publish during my tenure as Dean of the College of Liberal Arts. Like those that preceded it, the spring 2025 issue of the magazine showcases the profound range and depth of the work that our faculty, students, and alumni are doing every day to make our campus and the world a richer place. What you’ll find in these pages is exceptional on its own terms, but it’s not exceptional for the college. It’s what we do.

Scientists are often categorized as doing either “basic” or “applied” science, and that imperfect dichotomy can be stretched to fit our work across liberal arts as well. There is the “basic” humanities and social science research that you see, for instance, in anthropologist Becca Lewis’s work on drought adaptation in lemurs; literary critic Jennifer Wilks’s new book on how Bizet’s opera Carmen has been adapted to reflect the experience of people in the African diaspora; and classicist Andrew Riggsby’s use of cognitive science to understand how the ancient Romans thought. There is also the “applied” work, like historian of photography Steve Hoelscher’s curation of an Ansel Adams exhibition for the Harry Ransom Center and psychologist David Yeager’s new book on getting the best from our youths, 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People

In our case, however, we have to add some additional categories. We make art, like Bret Anthony Johnston with his new novel We Burn Daylight. We plumb the mysteries of baseball and ancient wisdom literature, like Bruce Wells in the latest installment of our “Highbrow Advice for Life” column. We serve as stewards of the land and the communities who live upon it, as alumna Maria Farahani does in her native Nicaragua, where she and her husband own coffee farms. And we enrich democracy, as alumni Carl and Tamara Tricoli have done with their gift to incentivize civil discourse in the college.

This is all work that makes the world a richer and more humane place. It’s testament to why the liberal arts, and its habits and virtues of nuance and complexity, are worth fighting to preserve and expand.

It is difficult to say good-bye to colleagues and alumni engaged in and believing in this amazing work, but it is easier with the knowledge that so much of what I’ve loved about the college will continue and grow. Our alumni will provide unwavering support. Our exceptional staff in the college, departments, and centers will keep things moving forward. Our brilliant faculty will plumb the depths and crannies of human existence. And our bright young students will keep asking questions and looking for ways to change the world.

Ann Huff Stevens Dean, College of Liberal Arts David Bruton Jr. Regents Chair in Liberal Arts

Photo by Wyatt McSpadden

ON BASEBALL AND WISDOM

LITERATURE

By Bruce Wells

“I guess there’s more to life than baseball.” That was my older brother’s conclusion after the coach at his small college cut him from the team. My father thought it was rather funny that he was just now coming to this realization. My 10-year-old self was horrified. If my star-athlete brother hadn’t made his college baseball team, there was absolutely no hope for a middling player like me. And how on earth could there be more to life than baseball?

Figuring out what’s important in life is not for the faint of heart. I imagine that most of us can remember a time when we discovered, sometimes painfully, that there was more to life than, well, whatever it was that we thought there wasn’t more to life than. And while we can always learn this from experience, it’d sure be nice to have a little help along the way.

So, forget the self-help books of today. Let’s go back some 3,000 years to the world’s original selfhelp texts, to what’s usually called the “wisdom literature” of the ancient Middle East. You find it in ancient Mesopotamia, in ancient Egypt, and even in certain biblical books like Proverbs. A few scholars now argue that we should stop calling it “wisdom literature,”

mainly because my field has its own issues figuring out what’s important in life, but whatever you call it, this literature tries to offer advice on how to pay attention to the stuff in life that really matters.

One of its favorite things to say is that there is more to life than wealth. For example, the Egyptian “Instructions of Amenemope” say not to “cast your heart away in pursuit of riches . . . for they will make themselves wings like geese and fly away to the heavens.” In the Book of Proverbs you find, “Don’t struggle to gain wealth . . . You might see it, but then it’s gone. It sprouts wings and flies away like an eagle into the sky.” I admit I’ve never actually seen my money fly off above me, though; I find it just sneaks out the back door when I’m not looking.

The false allure of material success shows up in ancient stories as well. Take the biblical character

of Jacob, a major figure in the narratives of Genesis. He knows what he wants out of life and is determined to get it. If you know the stories, then you know that he gets the inheritance he wants, the fatherly blessing he wants, the woman he wants, the children he wants, the security he wants, and all the wealth he could possibly want. When he’s old, he moves to Egypt to be near his favorite son. At the ripe old age of 130, he has an audience with the Egyptian king, who asks Jacob about his life. “The years of my life have been few and hard,” he says. That’s not at all what you expect him to say. I wonder how someone like him would fill in the blank: “There’s more to life than .”

In the end we all have to decide for ourselves what there isn’t more to life than. But here’s what I can tell you. Stories like Jacob’s can help, and even some of those

pithy sayings from that formerlyknown-as-wisdom-literature literature — and meeting people that are like Jacob or maybe a little like Jacob or not like Jacob at all. Stories and people. And experience and history and poetry and art and a little philosophy and maybe a few more pithy sayings.

I think the stories are the best. They don’t offer us concrete

answers so much as an array of insights into what might be important. From the ancient Middle East to our own modern time we have loads of stories, fictional and factual, about all kinds of different people. A lot of them are sad because — not to put to fine a point on it — our ilk has never been great at figuring this out. But many of them have happy endings, where people zero

in on what really matters and live meaningful lives in accordance thereto. The more stories we read, the better our chances of getting it right.

Now if I could find a place not too far away that would let a bespectacled middle-aged man play a little baseball, I could finally put paid to the notion that my brother had any idea what he was talking about.

Gate of Life

by Kyle Okeke

Quiet, says the officer walking me to the office, after I flashed my knife in school— the footsteps scuffing, shuffling—rain-like.

All of it moving because I am moving.

After the flood, a quiet rose

like a shirt off a body of land.

Bruce Wells is an associate professor of Middle Eastern studies at UT Austin. He specializes in the study of the Hebrew Bible and the Ancient Near East.

Kyle Okeke is a graduate student on the New Writers Project and has been published in Poetry, Four Way Review, and Foglifter His chapbook is forthcoming from The Poetry Society of America in 2026.

Photo by Jose Morales via Unsplash

COLLEGE NEWS

Sociologist Receives Lifetime Achievement Award for Education Research

Emerita Professor Wins 2024 Pulitzer Prize in History

Emerita professor of history Jacqueline Jones won the 2024 Pulitzer Prize for her book No Right to an Honest Living: The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era (Basic Books). The book examines how Black workers were systematically denied access to skilled trades, factory work, and public works projects, revealing the stark contrast between Boston’s antislavery reputation and its treatment of Black residents. The Pulitzer committee lauded her work as a “breathtakingly original reconstruction of free Black life in Boston” that transforms our understanding of the city’s complex abolitionist legacy.

This is Jones’ third Pulitzer recognition, following two previous finalist nominations, and adds to her distinguished career honors, which include a MacArthur Fellowship and membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The American Sociological Association has awarded its highest honor in education research to Chandra Muller, professor of sociology at UT Austin, whose groundbreaking studies examine how schooling shapes life outcomes across decades. Muller received the 2024 Willard Waller Award for lifetime achievement in sociology of education research. Muller currently leads two major longitudinal studies tracking high school students into later life, including a $50.3 million National Institute on Aging project — the largest grant ever awarded to UT’s College of Liberal Arts. Her research has significantly advanced understanding of educational disparities related to gender, race, ethnicity, social class, disability, and immigration status, while influencing both academic scholarship and policy development.

Inaugural Arrow Prize Goes to UT Austin Economist Research that fundamentally reshapes how we understand pricing, regulation, and taxation has earned UT Austin economics professor Vasiliki Skreta the inaugural Arrow Prize from Econometrica, one of the field’s most selective journals. The biennial prize recognizes the best economic theory paper published in the journal over a four-year span. Skreta and Columbia University professor Laura Doval were honored for their 2022 paper “Mechanism Design with Limited Commitment,” which offers powerful new insights into how markets and policies evolve over time. The prize is named for Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow and aims to encourage high-quality theoretical contributions to economics.

Diehl Prize Supports Student’s International Education Mission

The University of Texas at Austin awarded its 2024 Randy Diehl Prize to psychology and rhetoric double major Neerul Gupta for her commitment to postgraduation public service. The selective, merit-based award recognizes graduating College of Liberal Arts seniors dedicated to serving the greater good. A member of both the Liberal Arts Honors and the Dedman Distinguished Scholars programs, Gupta will use the prize to support her year teaching English to underserved students in Madrid through the Council on International Educational Exchange. The award will allow her to focus fully on teaching and volunteer with education nonprofits rather than seeking supplemental employment.

Government Professor Named to AAAS Professor of government Christopher Wlezien has been elected to the American Academy of Arts & Sciences (AAAS), one of the country’s oldest and most prestigious scientific societies. A first-generation college student, Wlezien joined the faculty at UT Austin in 2013 and is known for developing the “thermostatic” model of public opinion and policy. He has also made significant contributions to understanding electoral systems, policy responsiveness, and the role of mass media in public policy engagement. His current research examines how political institutions influence electoral preferences across more than 300 elections in over 40 countries.

UT Austin Scholars Win Fulbright Awards to Study Climate Crisis and Wildlife Parasite Ecology

Linguist and Philosopher Awarded Schock Prize Hans Kamp, professor at the University of Stuttgart and UT Austin, has been awarded the 2024 Rolf Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy, sharing the honor with MIT’s Irene Heim. The prize, awarded every three years by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and the Schock Foundation, recognizes the scholars’ independent contributions to dynamic semantics in natural language. A pioneer in logic, linguistics, and philosophy of language, Kamp is renowned for developing Discourse Representation Theory.

National Endowment for the Humanities Awards Major Grants to Two Faculty Members

The National Endowment for the Humanities has awarded grants to two UT Austin researchers for groundbreaking projects on Black history. Associate professor Danielle Clealand will create an open-access digital archive documenting Black Cuban immigrants’ experiences from 1959-1980, exploring how they navigated discrimination in Miami. Associate professor Ashanté M. Reese’s “The Carceral Life of Sugar” will investigate connections between the Imperial Sugar Company of Sugar Land, Texas, and the prison system, sparked by the 2018 discovery of 95 unmarked prisoner graves. Both projects aim to illuminate overlooked aspects of Black history and experience in America through innovative research approaches.

Professors J. Brent Crosson and Anthony Di Fiore have received Fulbright U.S. Scholar awards for 2024-25. Crosson will study the Caribbean’s role in climate crisis history at the University of the West Indies, while Di Fiore will research primate microparasites in Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest, focusing on wildlife disease transmission between humans and animals. Danielle Clealand, associate professor of Mexican American and Latina/o studies, and Ashanté M. Reese, associate professor of African and African diaspora studies.

Jacqueline Jones, emerita professor of history at UT’s College of Liberal Arts.

RESEARCH NEWS

ENDANGERED LEMUR SHOWS RESILIENCE TO DROUGHT CONDITIONS

Verreaux’s sifaka, a critically endangered species of lemur found in the seasonally dry tropical forests of western Madagascar, demonstrated remarkable resilience to long periods of drought and resource scarcity, according to a 13-year study published in Integrative Conservation by scientists at The University of Texas at Austin, Midwestern University, and University of Arizona, Tucson.

Working in Madagascar’s Ankoatsifaka Research Station from 2010 through 2023, the team collected data on rainfall, tree survival, and the availability of the sifaka’s major food sources (tree leaves, flowers, and fruit). For this same time period, they observed sifaka feeding behavior and measured their weight, body mass index, and subcutaneous fat levels as well as their rate or reproduction and infant survival.

suffer. We studied a species that experiences extreme seasonal variation in resources every year and found that they weren’t really worse off during times of severe drought,” says Lewis. “What this means is that as we attempt to understand and plan for how the world is changing due to global

warming, it is important to keep in mind that not all species react the same to increasingly harsh environments.”

The authors note that, in the long run, the sifaka’s adaptations may not be enough to assure their survival in the face of increasing

extreme weather events, along with other threats such as deforestation and poaching. But for the moment, their ability to adapt to drought may protect them from the negative effects of climate change.

“This started out as a project exploring the effects of drought on sifaka health,” says lead author Carrie Veilleux, who earned her Ph.D. at UT Austin and is now assistant professor of anatomy at Midwestern University.

“I expected to see their health decline during drought periods, so it was really surprising that not only did their health not decline, but the sifaka actually got fatter!”

This increase in fat was due to a change in the sifaka’s eating behavior exhibited during drought years. As trees withered during long dry periods, the sifaka consumed fewer leaves and instead focused their foraging on trees’ fruit and flowers, an adaptation that allowed them to survive despite the scarcity of water.

“There weren’t more fruits or flowers available during the drought, so the lemurs were clearly seeking out these sugar- and waterrich foods,” explains Rebecca

The researchers found that during three years of severe drought during the study period, the sifaka not only maintained their weight and health but also increased their subcutaneous fat levels.

Lewis, professor of anthropology at UT Austin and co-author of the study. “Why do they normally eat leaves instead of fruits and flowers? Why make this dietary switch during droughts? We think that they are putting on the fat as a means of storing water rather than for storing energy.”

The study also found no negative impacts on sifaka reproductive output or infant survival during severe drought.

In normal years, the sifaka’s environment experiences seasonal dry periods between June and November. This regular variation in resource availability may have led to the adaptive behaviors that helped them weather longer spells of scarcity. As extreme weather events such as droughts increase, the sifaka’s adaptive strategy may help them survive amidst changing conditions.

“Most of the time when we think about animals experiencing severe drought in their habitats, we think that they surely must really

A Verreaux’s sifaka. Photo by Rebecca Lewis.

RESEARCHERS USE AI TO TURN SOUND

RECORDINGS INTO ACCURATE STREET IMAGES

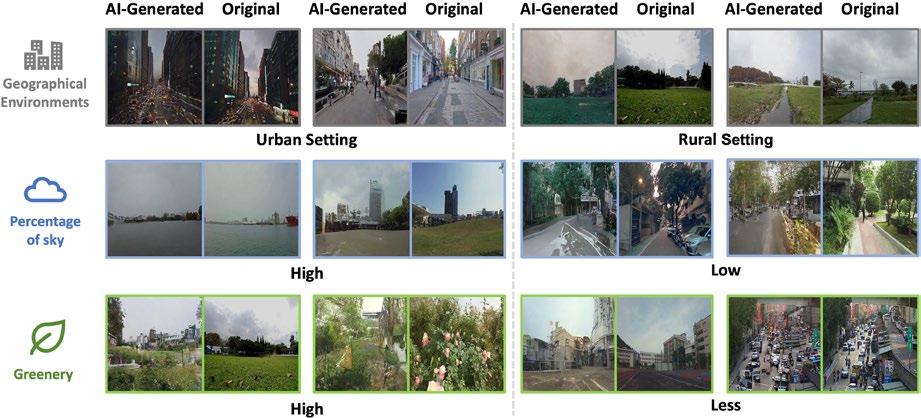

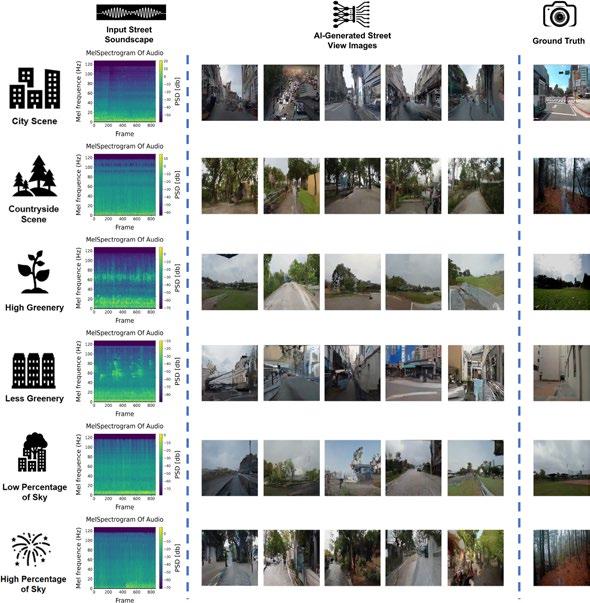

Using generative artificial intelligence, a team of researchers at The University of Texas at Austin has converted sounds from audio recordings into street-view images. The visual accuracy of these generated images demonstrates that machines can replicate human connection between audio and visual perception of environments.

In a paper published in Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, the research team describes training a soundscape-to-image AI model using audio and visual data gathered from a variety of

urban and rural streetscapes and then using that model to generate images from audio recordings.

“Our study found that acoustic environments contain enough visual cues to generate highly recognizable streetscape images that accurately depict different places,” says Yuhao Kang, assistant professor of geography and the environment at UT and co-author of the study. “This means we can convert the acoustic environments into vivid visual representations, effectively translating sounds into sights.”

Using YouTube video and audio from cities in North America, Asia, and Europe, the team created pairs of 10-second audio clips and image stills from the various locations and used them to train an AI model that could produce high-resolution images from audio input. They then compared AI sound-to-image creations made from 100 audio clips to their respective real-world photos, using both human and computer evaluations. Computer evaluations compared the relative proportions of greenery, buildings, and sky between source and generated images, whereas human

judges were asked to correctly match one of three generated images to an audio sample. The results showed strong correlations in the proportions of sky and greenery between generated and real-world images and a slightly lesser correlation in building proportions. And human participants averaged 80% accuracy in selecting the generated images that corresponded to source audio samples.

“Traditionally, the ability to envision a scene from sounds is a uniquely human capability, reflecting our deep sensory connection with the environment. Our use of advanced AI techniques supported by large language models demonstrates that machines have the potential to approximate this human sensory experience,” Kang says. “This suggests that AI can extend beyond mere recognition of physical surroundings to potentially enrich our understanding of human subjective experiences at different places.”

In addition to approximating the proportions of sky, greenery, and buildings, the generated images often maintained the architectural styles and distances between objects of their real-world image counterparts, as well as accurately reflecting whether soundscapes were recorded during sunny, cloudy, or nighttime lighting

conditions. The authors note that lighting information might come from variations in activity in the soundscapes. For example, traffic sounds or the chirping of nocturnal insects could reveal time of day. Such observations further the understanding of how multisensory factors contribute to our experience of a place.

“When you close your eyes and listen, the sounds around you paint pictures in your mind,” Kang says. “For instance, the distant hum of traffic becomes a

bustling cityscape, while the gentle rustle of leaves ushers you into a serene forest. Each sound weaves a vivid tapestry of scenes, as if by magic, in the theater of your imagination.”

Kang’s work focuses on using geospatial AI to study the interaction of humans with their environments. In another recent paper published in Nature, he and his co-authors examined the potential of AI to capture the characteristics that give cities their unique identities.

Sample street view images in the three groups (urban vs. rural; high and low greenery; high and low sky visibility). Image courtesy of Yuhao Kang.

DIGITAL THERAPY VIA SMARTPHONE IS COST-EFFECTIVE

For patients across the world with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the treatment of choice is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, or CBT. But accessing therapistprovided CBT can be prohibitively difficult, and many individuals with an anxiety disorder do not receive adequate treatment. This results in a lower quality of life for patients as well as an economic burden for both individuals and their employers. A new study from university researchers has identified a promising solution: fully automated digital CBT provided via smartphone.

The study, recently published in PLOS Mental Health and funded by Big Health, the developer of digital CBT program Daylight, modeled anxiety treatment for 100,000 patients in the United States. The international and interdisciplinary research team behind the study — including UT Austin professor of psychology Jasper Smits — found that automated digital CBT was costeffective and cost-beneficial for both private payers and society at large. In fact, when measured against other treatment options for general anxiety disorder, including medication and therapist-delivered CBT as well as no treatment, their model

AND BENEFICIAL

identified automated digital CBT as the most cost-effective.

“The results showed that Daylight had similar benefits to therapistdelivered CBT but at a lower price and that it generated more value than medications due to strong clinical benefits and reduced need for ongoing anxiety management visits,” says Smits. “Individual CBT has been identified as a firstline treatment option for GAD, so we were comparing digital CBT here to a really efficacious standard in the field.”

To establish the cost-effectiveness of treatment options for GAD, the researchers first calculated the total cost of each option as well as the costs of living with an anxiety disorder both for patients and for their employers. These costs can be substantial: total direct medical costs associated with GAD has been estimated to be around $38 billion a year, and workers with GAD may require more healthcare spending and take more sick days, driving up total costs. The researchers also accounted for the ability of various treatment options to improve patients’ overall quality of life.

In their model, which tracked 100,000 patients for 12 months,

digital CBT was found to have the lowest overall cost and to be as effective as other, more expensive forms of CBT in improving patient quality of life.

“The cost-effectiveness of Daylight is striking,” says Michael Darden, the lead researcher on the study and an associate professor of economics at Johns Hopkins University. “Under a range of treatment effect assumptions, our economic modeling shows that Daylight may provide considerable value to the healthcare system. This could have major implications for how we allocate resources in mental health care.”

The researchers say their study should encourage healthcare providers to consider digital CBT for patients with anxiety. Doing so would make CBT more accessible and affordable, with significant benefits for individual patients and for society more generally.

“Our findings demonstrate that digital CBT offers a highly effective and accessible treatment option for generalized anxiety disorder,” says Smits. “This has the potential to significantly expand access to evidence-based care for those who do not want traditional therapy.”

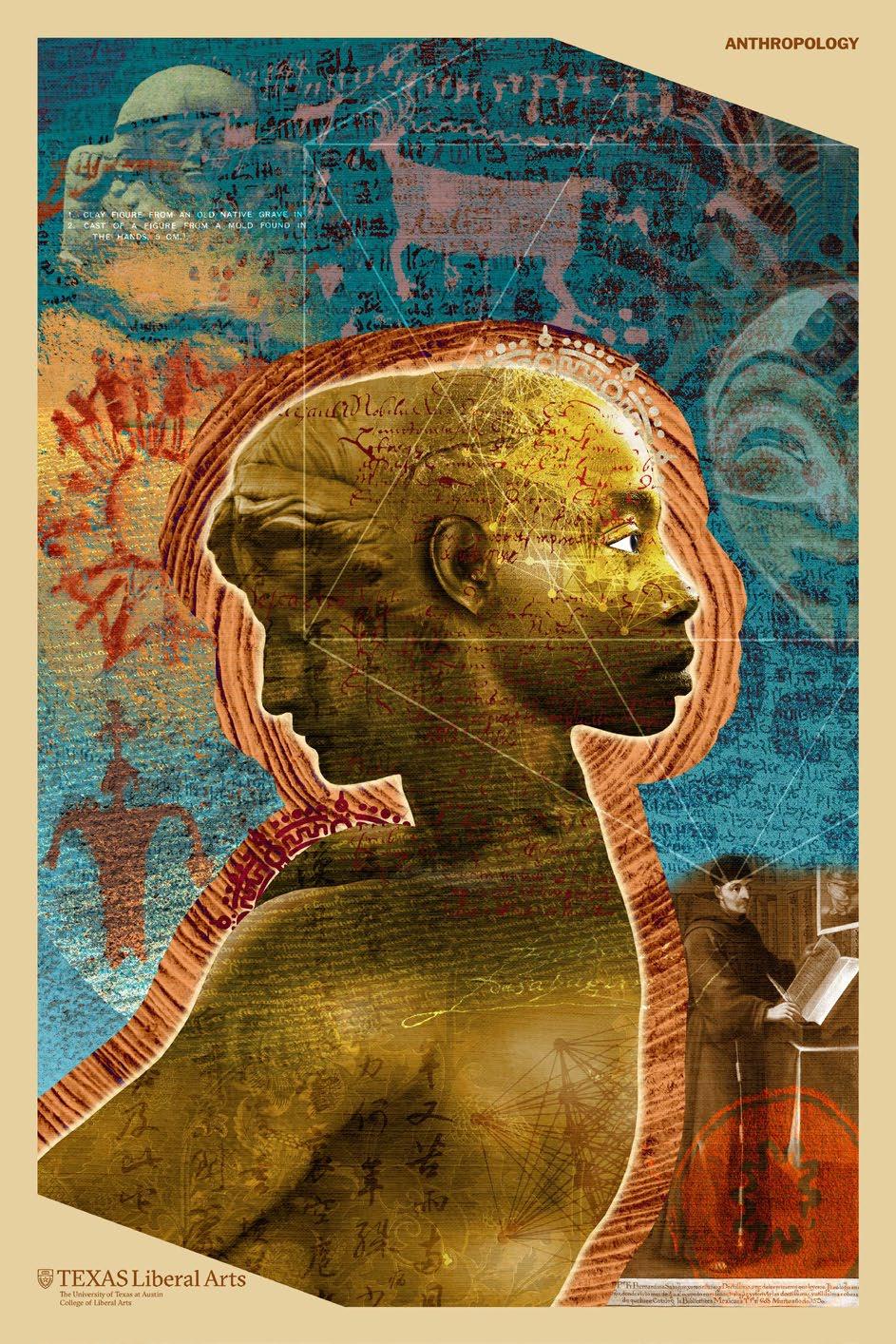

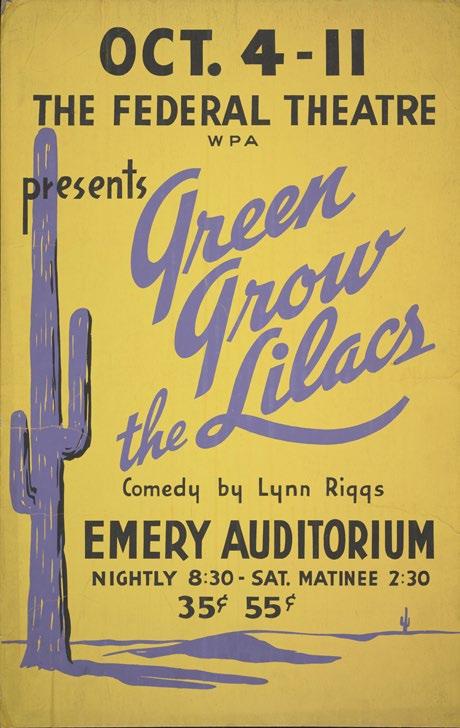

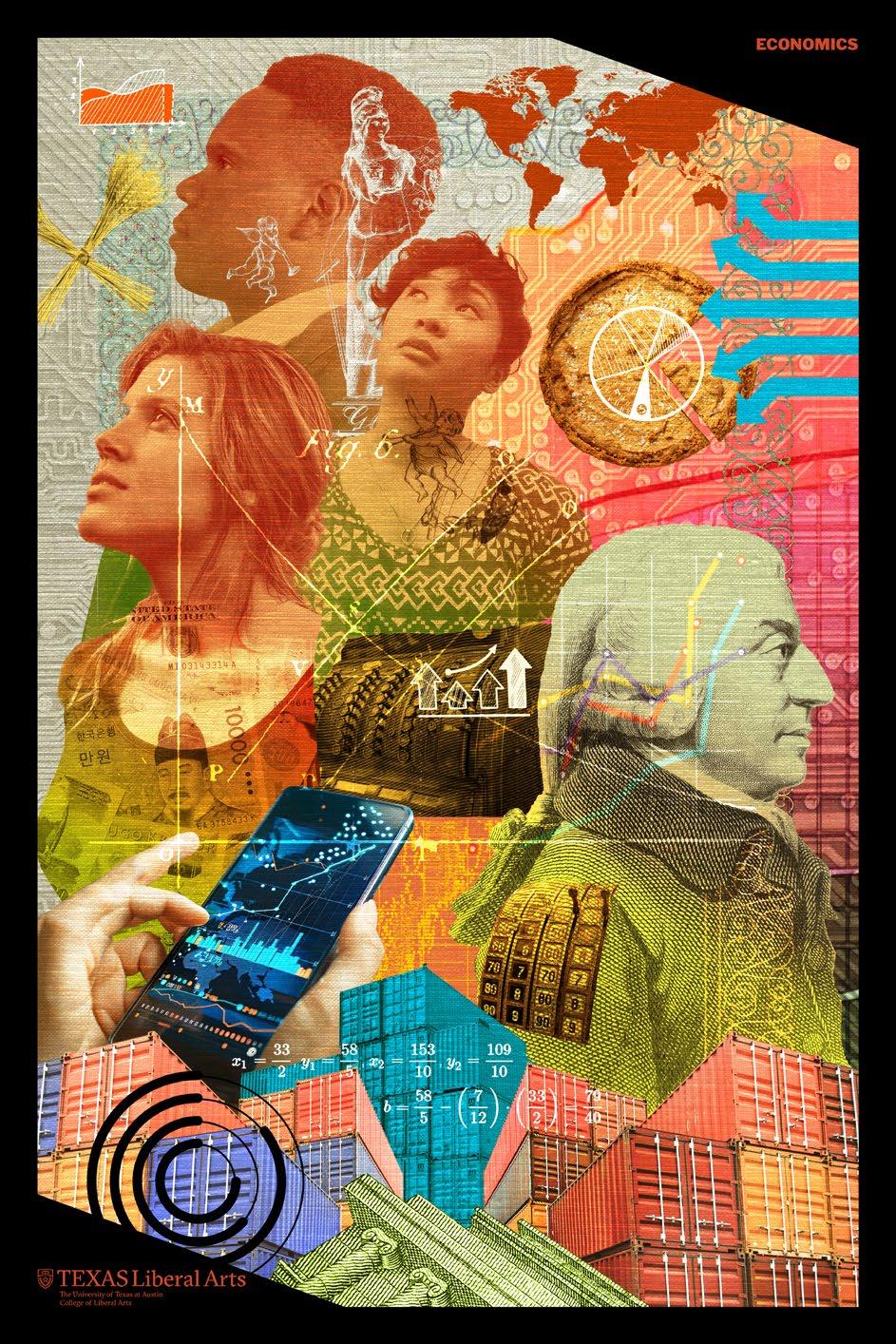

The posters you’ll see throughout the magazine are part of a larger forthcoming project by artist Dave McClinton that will feature a poster for each department and select interdisciplinary programs in UT Austin’s College of Liberal Arts. The posters will be displayed in the Dorothy Gebauer Building. Stay tuned for information about the opening.

RECRUITMENT SEASON

By Daniel Oppenheimer

Oneof the most fundamental dilemmas I face as head of communications for the College of Liberal Arts is that many of our undergraduates didn’t choose to be here. Right now, about half of the students in each incoming class identified our college as their first or second choice when they applied to UT Austin. They want to be here, in other words, and not just at UT. The other half of our first-year class didn’t list us as a preferred college, but decided to come here anyway because they want to be at UT.

We’re happy to have these students, of course, and in fact their presence is a significant factor in why our college of liberal arts hasn’t seen the same drastic declines in certain majors as many of our peer institutions. From a brand perspective, though, this is not an ideal situation. It’s also not ideal for the students themselves, who (according to a recent analysis we conducted) are 16% less likely to graduate in four years than the students who chose specifically to be here.

Because of the way UT Austin admissions work, we’re always going to have some of these students. There is the potential, however, to drive up both the number of overall applicants who are interested in the liberal arts and the number of admitted liberal artsoriented students who choose to matriculate to UT. Moving the needle on either of these numbers would result in a college with more students who really want to be here. That would be good.

This is the background to a campaign we’ve been developing to market the college to both prospective and admitted-but-not-yetmatriculated students. We’re far enough along that I can share some initial concepts with you as well as the fruits of the research that went into developing our campaign.

The research had three main elements. I did a scan of how other universities are pitching themselves to prospective students. I conducted small, informal focus groups with students and relevant staff

and leadership. And I just lived my life as the father of a daughter in her senior year of high school, watching the flood of mailings and emails pass through her inbox and our mailbox (usually on the way to the real and virtual trash).

The global takeaway from each path of inquiry was the same: It all kind of blends together after a while. Colleges and universities are all drawing from the same bucket of core themes: connection, opportunity, warmth, selfdevelopment, tradition, innovation. We all feature the same kind of photography of happy and engaged students, passionate-looking teachers, and idyllic campus landscapes. We’re all telling versions of the same story, which is that you should come to our school to discover yourself and build your exciting future.

I don’t take this to mean that there’s no point in doing such marketing, but it’s useful to have this broad view in mind. It helps to clarify what the point is and what a set of realistic expectations should be. For

lesser-known schools, the goal may be to put yourself on the radar of students who otherwise wouldn’t know about you. For many of the elite schools, it’s clearly to artificially juice their selectivity by driving up applications from students who have little chance of getting in.

For every school, of course, the point is to increase applications and matriculations, but there are other goals as well. It’s our first communication with the students who will eventually attend our school, and it’s an opportunity to get them excited about and acculturated to our community. There’s also the much longer-term project of developing and reinforcing loyalty to the institution that will persist beyond graduation..

So the marketing matters, if often at the margins, and it’s interesting to observe how schools sell themselves. A&M

is warm and familial (“Join the Aggie Family”). MIT’s main admissions site is a feed of blog entries from current students, each of whom gets a cute custom illustration. Sewanee sells the natural beauty of its environs. Texas Tech is selling tradition and spirit (“Be a Part of the Legacy”). If I had to characterize our current prospective student landing page, which features the tag line “Choose COLA,” I’d say it’s pretty median: bright and colorful, happy students, cool-sounding classes, etc. Its message is that this is a place where students are engaged and upbeat.

Our prospective student brochure features the tagline “Your Story Starts Here,” and the vibe is communal and warm. This is a place, it’s conveying, where you can find yourself, where you’ll have support, and where your

experience is valued. It’s a beautifully designed brochure, and the message is a solid one, but the tone is a bit softer than what we plan to implement. The conclusion we’ve come to is that we need to increase the emphasis on achievement and ambition in order to better compete for students who might otherwise choose a STEM discipline, a business degree, or a liberal arts degree at another college or university.

The heart of our new campaign is what I’m calling, informally, the wheel of destiny. You can see one iteration of it, “For Future Leaders,” in the graphic above. The point of the wheel is that it can land on many different futures, depending on each student’s interests and talents. Whatever your destiny, in other words, the College of Liberal Arts is here to help you discover it and then give you the skills and support to launch into it. We’re large and many-splendored and dynamic and well-resourced.

We’re not laboring under the illusion that this is a oncein-a-generation marketing concept. Our sense is that it’s a good one, and that it will serve to anchor a more strategic, more coordinated set of communications across the varied platforms. We’ll produce a video, a social

media campaign, a new brochure, email graphics, etc., and it will give more efficacy and consistency to both our prospective student campaign and our communications with current and former students.

It’s often the case, in branding and marketing, that simply having a consistent message across platforms and repeating it over time is more important than optimizing for the most brilliant message. Repetition and consistency tend to prevail over an extra 4% of creativity.

That said, if you’ve got a brilliant idea, please share it with me. My inbox is open: oppenheimer@utexas.edu.

The vibe on the A&M admissions page is warm and familial.

The AI students in this image will be replaced with real UT students.

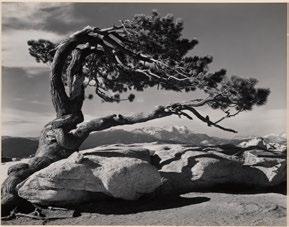

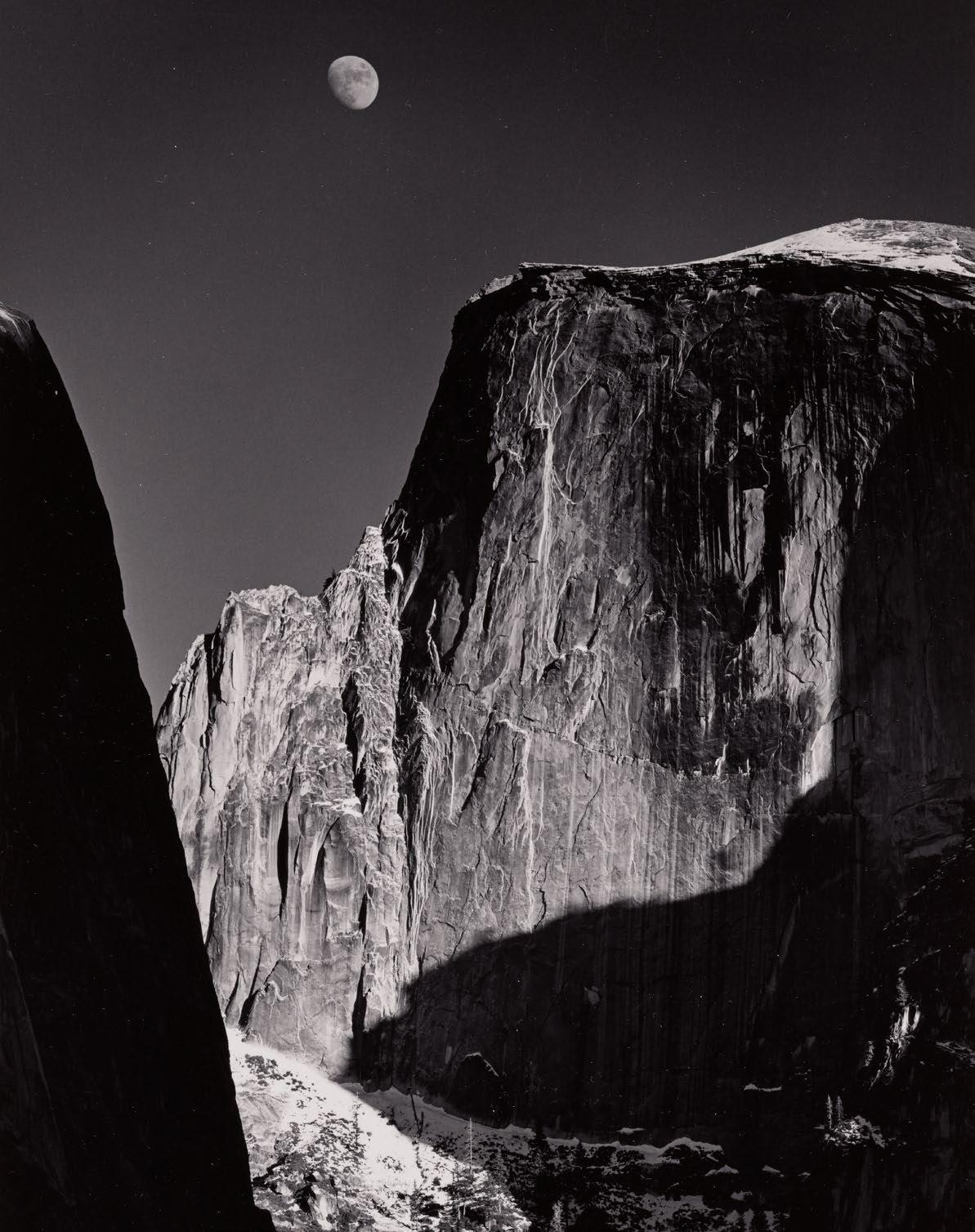

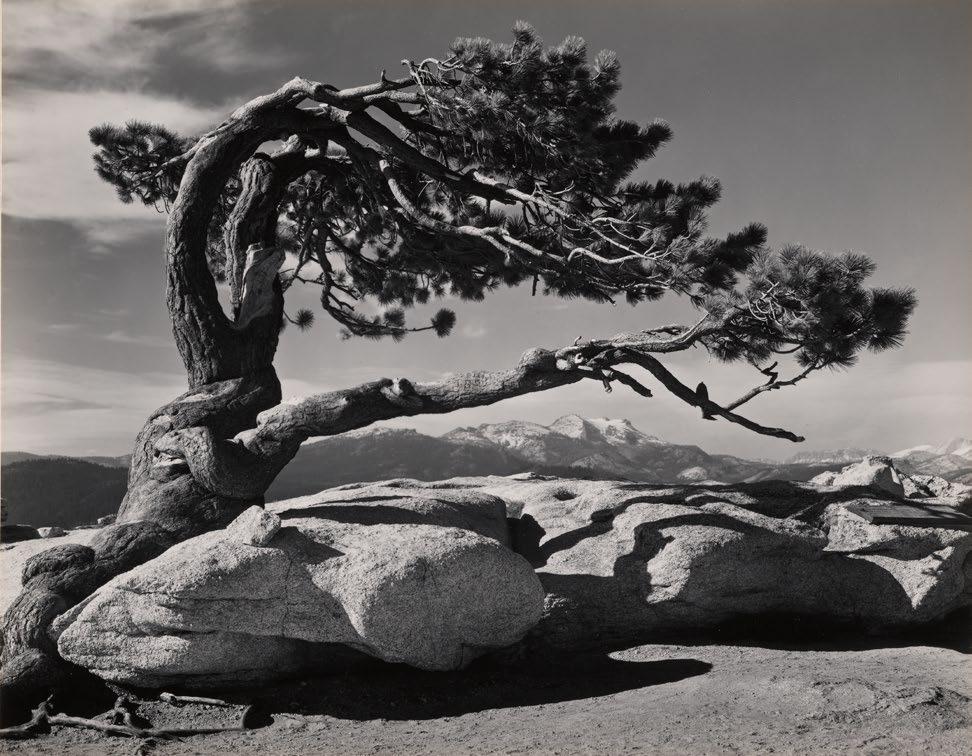

Ansel and Me

An American studies professor’s adventures in curating

BY STEVEN HOELSCHER

The first time I encountered the photography of Ansel Adams wasn’t in a museum gallery but during a college course. I remember the moment well. The course, “Wilderness and the American Mind,” introduced me to a wide range of memorable texts. In good American studies fashion, we dove into writing by Thoreau, Willa Cather, Rachel Carson, William Cronon, and more — and also the photography of Ansel Adams.

As much as anything that I read in that course, the 35 mm slides that I viewed affected me in far-reaching and unpredictable ways. I became aware, probably for the first time, of photography as an art form. I was seeing images that inspired me and made me want to explore the natural world in a way that art previously hadn’t.

I’ve learned a lot about Ansel Adams since “Wilderness and the American Mind,” and I have a much better sense of why his photographs moved me so profoundly. I understand how his work both fit into the canon of photographic history and served as an inspiration for the environmental movement. And I’ve seen the magical power of Adams’ original prints: how they, more than any other format, present his photographic images in exquisitely wrought detail that demand attention.

Over the past year, in my role as faculty curator of photography at the Harry Ransom Center, a major humanities research center and museum here at UT Austin, I’ve worked to put together

“Visualizing the Environment: Ansel Adams and His Legacy.” During the process of curating this exhibition, I’ve often reflected on the experience of conceiving, researching, and mounting pictures. While I’m familiar with the role of critical scholar from my faculty position in the Department of American Studies, curating is relatively new for me. I’ve found that creating an exhibition is a lot different than critiquing it.

From the beginning of the curating process, when I began reviewing all the prints by Adams that we had at the Ransom Center, several specific themes emerged, including Adams’ change over time as he developed as a photographer, the powerful sense of place he felt in Yosemite, and the role of photographs in environmental conservation. Other themes began to emerge as I dug deeper into the center’s photography collections. It became clear that Adams’ belief in the power of photographic visualization to inspire reverence for the natural environment set him apart from most of his 19th- and early-20th-century precursors, whose photographs often focused on presenting views of the landscapes for corporate or governmental interests. Other photographers, especially those connected to the important journal Camera Work (1903-1917), presented photography as a fine art, but they did so from different aesthetic perspectives.

For photographers who have come after Adams, his legacy looms large, and for many contemporary photographers it represents both a debt and a burden. The photographer Mark Klett, for example, describes how Adams helped raise environmental consciousness and prove that photography could be a powerful medium for that project. At the same time, by removing evidence of the human impact on the earth, Adams presented a romanticized vision of a lost world. As Klett puts it, “The landscape is not so much a paradise to long for (some say a paradise lost), as it is a mirror that reflects our own cultural image.”

The resulting exhibition explored both Adams’ work and that of the photographers who came before and after him. I ultimately selected nearly 100 objects to be included in the exhibition and, together with the Ransom Center’s preservation and conservation teams, made decisions about how to present each photograph and where it would be placed in the gallery. The “identity” of the exhibition began to take on firm shape as the Ransom Center’s creative director, Leslie Ernst, helped me think through the interplay of images, colors, fonts, and layout of wall texts. I also considered the materials that would extend the reach of the exhibition beyond the gallery. With the assistance of Stephanie Zeller, a graduate student in UT’s Department of Geography and the Environment, we created an online GIS story map to accompany the exhibition. By mapping and generating three-dimensional renderings of the sites of many

of the photos in the exhibition, it gives viewers a sense of what the landscape might have looked like to the photographers.

The installation process itself was an enormous task, with the inevitable hiccups and unexpected complications. For the better part of two weeks, at least twice each day I visited the galleries as the exhibition came together, making final decisions about object placement and text revisions. The entire experience felt like a three-dimensional set of page proofs that authors receive from publishers; it’s both your last chance to make modest corrections and where all the hard work becomes real.

The exhibition opened in late August 2024 and ran through February of this year. Dozens of university classes visited every week and, I was told, attendance for exhibitions at the Ransom Center went

up 110%. It’s humbling to realize that, as measured by public engagement, organizing this exhibition will probably be more impactful than any book, article, or chapter than I’ve ever written.

As my experience over the past year has demonstrated to me, organizing an exhibition at a place like the Ransom Center is itself a form of scholarly activity. Even if that work does not appear in one of the data platforms that are often used to measure faculty productivity, the creative, logis-

tical, and intellectual labor necessary to produce an exhibition is substantial and should be recognized as such. This kind of public humanities work is also deeply collaborative. The number of people who contributed to this exhibition is staggering, and never have I worked so closely with so many ultra-competent and devoted colleagues dedicated to enlightening, engaging, and inspiring as many people as possible. For me, this experience has been a career highlight — and it’s all thanks to Ansel Adams.

Steven Hoelscher (left) and Ransom Center creative director Leslie Ernst supervise the installation of “Visualizing the Environment.”

Photo by Ashley Park.

Ansel Adams (American, 1902–1984), Jeffrey Pine 1945; Yosemite Special Edition Print ca. 1970. Gelatin silver print, 17.9 x 23 cm (image).

Harry Ransom Center, Photography Collection, gift of Stephen and Joyce Latimer Hunt, 2015:0036:0007. © Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust.

Steven Hoelscher is professor of American studies, associate dean for academic affairs for the College of Liberal Arts, and faculty curator for photography for the Harry Ransom Center.

HIKES FOR TYKES

There is a pretty direct line, or maybe we should say a not-so-direct line, between the work that sociologist Nina Palmo does at The University of Texas at Austin as an assistant professor of instruction and her new book. On campus, she teaches courses on topics like “Health and Society” and “Economic Sociology of Health.” In her book, she spreads the gospel of health and nature to the families of Texas. 50 Hikes with Kids Texas, published last year by Timber Press, highlights the most kid-friendly hikes in the Lone Star State, including the one-mile hike in Big Bend below. The book includes all the essential details, including the length of hike, the elevation you’ll have to cover, nearby bathrooms, and where you can go to get the kids a snack.

Who’s Counting?

Anat Schechtman on non-quantitative notions of infinity

By Alex Reshanov

The German mathematician David Hilbert proposed a thought experiment about a hotel with an infinite number or rooms. Even at full capacity — its infinite rooms occupied by infinite guests — the hotel could always accommodate more. If, say, four new guests arrived, the hotel would move each of its existing guests to a room four numbers higher. The guest in room one would move to room five, room two to room six and so on, freeing up rooms one through four for the newcomers. Impressively, the hotel could even find space for an infinite number of additional guests. In this case it would move its existing guests to the double of their current room numbers (one into two, two into four, etc.), thus freeing up all the odd numbered rooms, an infinite amount of them. A clever system if we overlook the inevitably high turnover rate among the cleaning staff.

I describe Hilbert’s hotel to demonstrate two points. The first is that pondering infinity is entertaining, at least if you’re

the type who enjoys brain teasers and paradoxes (and if you’re not, I probably lost you at “German mathematician”), and the second is that discussions of infinity often focus on quantity. Whether it’s the infinite years of eternity, the infinite space of our boundless universe, or the infinite amount of shrimp Red Lobster audaciously promised you could receive for only $20, we tend to think about infinity as a limitless amount of something.

But according to associate professor of philosophy Anat Schechtman, there are multiple ways to conceive of infinity, and

some have nothing to do with counting. Schechtman — who specializes in early modern philosophy, a period encompassing the 17th and 18th centuries that gave us influential thinkers like Descartes, Locke, and Kant — is writing a book on notions of infinity from this era and has uncovered several distinct philosophical approaches. Some will be familiar to contemporary sensibilities while others require us to stretch our imaginations...

Continue reading at https://lifeandletters.la.utexas.edu/2025/01/ whos-counting/

by Nina Palmo and Wendy Gorton, photographs by Wendy Gorton.

Associate professor of philosophy Anat Schechtman. Photo by Alex Reshanov.

make parents proud and those that horrify them).

THE MENTOR MINDSET

PSYCHOLOGY PROFESSOR

DAVID YEAGER ON HOW TO SPEAK SO YOUNG PEOPLE WILL LISTEN

By Imani Evans

If the headlines are to be believed, it’s never been harder to motivate young people. The reasons abound: they’re too soft, too sensitive, too overwhelmed, too entitled, too stressed, too social mediaaddicted, too lacking in work ethic.

Psychology professor David Yeager takes on these contentions and more in his new book, 10 to 25: The Science of Motivating Young People (Simon & Schuster, 2024).

“The idea for this book grew out of a simple observation I made about a decade ago,” writes Yeager in the introduction, “that many beloved programs to promote youth health and well-being were shockingly ineffective.”

Yeager’s work belongs to the intellectual lineage of books like Angela Duckworth’s Grit,

Carol Dweck’s Mindset, and Mary Murphy’s Cultures of Growth. His major purpose is to lay bare the secrets of what he calls the “mentor mindset,” with its careful balance between high standards and support. The book provides numerous examples of mentor mindset in action, through profiles of successful coaches, managers, teachers, and parents who — sometimes after trying other approaches that didn’t work so well — learned how to get the best from their pupils or mentees.

The “10 to 25” in the title refers to the age range during which, Yeager argues, puberty-linked changes in the brain start to cause the palpable status anxiety we see in teens. Yeager defines status in terms of young people’s longing for prestige, a kind of social currency that young people gain through impressive acts (both those that

Yeager sympathizes with parents — after all, he is one. But, he argues, parents will flail when not taking into consideration young people’s desire for status and respect. Importantly, both authoritarian and permissive parenting styles suffer from this basic flaw.

“Any time young people interact with socially powerful people — managers, parents, educators, or coaches — status and respect come to the foreground,” Yeager writes early in the book. “Because young people feel sensitive to differences in status, they are subtly reading between the lines with each thing we say, trying to interpret the hidden implications of our words, to find out if we are disrespecting or honoring them.”

Why is it so important to understand motivation in young people? Most obviously, the stakes are high. They include, for instance, young people’s academic achievement, future job prospects, and emotional well-being. Sadly, young people will often follow adults’ lead by either underestimating themselves or seeing themselves as broken when they struggle.

The principal adversary in this story is what Yeager calls the

“neurobiological incompetence model” of adolescence. It’s a familiar story: young people’s underdeveloped brains are what cause them to behave impulsively and make poor choices. The model has evidence behind it, including an abundance of neuroscientific findings that the prefrontal cortexes of young people, crucial for decision-making and planning, are still developing.

Unfortunately, argues Yeager, it doesn’t tell the whole story, and it leads to two faulty approaches to young people. One is what he calls the “enforcer mindset,” which is oriented around the threat of consequences for not meeting a given expectation. If a young person’s brain is underdeveloped, what’s the point of reasoning with them? The other is the “protector mindset,” which is sort of the opposite. It prioritizes young people’s self-esteem at the expense of real flourishing.

The mentor mindset, on the other hand, strikes the right balance. Yeager writes, for instance, of a group of students assigned a history project that involved interviewing surviving

World War II veterans. There were real stakes to doing a good job; these were veterans whose stories have never been told, and the students were entrusted with capturing those stories faithfully.

“The Enforcer or Protector would never consider giving that kind of assignment,” says Yeager. “Because the Enforcer thinks that young people are only responsive to material incentives or threats of punishment. That’s why the Enforcer walks around yelling at everybody, threatening them, or bribing them.”

The protector mindset fails by coddling young people, says Yeager. “When you’re the Protector you’re like, ‘Oh, no, your life is too hard. I can’t ask you to put the weight of the world on your shoulders. It would cause you stress. It would cause you anxiety. I need to protect you until your thirties and then you can go make a difference.’”

“What I argue is that the Mentor way to do it is to be like, ‘Unfortunately, the world is totally messed up, and there’s a lot of stuff wrong,’” says Yeager. “‘But you, young person, have an asset, and the asset is that moral clarity that comes from being young and seeing problems in the world, and the energy that you bring to making a difference.’” 10 to 25 is a work of social science. It is also a work of journalism. Yeager credits a friend, Austin journalist and writer Paul Tough, with nudging him in this direction.

“But you, young person, have an asset, and the asset is that moral clarity that comes from being young and seeing problems in the world, and the energy that you bring to making a difference.”

“Paul wrote a great book about higher education that features UT as a success story,” says Yeager, referring to Tough’s book The Years that Matter Most: How College Makes or Breaks Us “And I helped him a ton in that reporting.”

His friend’s story-driven approach rubbed off on Yeager.

He contrasts himself with an imagined psychologist who, writing a similar book, might only look for stories that support a predetermined conclusion. But Yeager soon realized that the story told by his science alone was insufficient.

“I actually learned a lot from these people,” says Yeager. “And I changed my hypothesis. So, it really was a theory that developed partially through experimental research and partially through a systematic approach to reporting on real people’s experiences.”

An example of one of the book’s illuminating case studies is physics teacher Sergio Estrada, who teaches at Riverside High School in El Paso. His courses are demanding, sometimes just on the verge of overwhelming his students. But Estrada engages his students around some core principles at the heart of 10 to 25. He tells them that struggles are normal and not a reflection of students’ innate ability. He delights in answering questions. He gives hard assignments and tests, but allows them to be re-done. And he makes sure his students know he will always be there for them. Faced with a frustrated student, Estrada’s approach is to coax the student to explain their thinking on a problem — not just giving them the answer — followed by

collaborative problem-solving. Through learning such challenging materials, students gain a sense of mastery and the prestige that comes with it. In a school where 2% of students are college ready, according to SAT scores, 95% of his students pass college-level physics.

But Yeager doesn’t just want a model to admire. His goal is to turn the science of youth motivation into interventions at scale. In that spirit, he launched the FUSE Fellowship at UT Austin. The two-year fellowship is a partnership between Texas math teachers and the university’s Behavioral Health Science & Policy Institute. Enrolled teachers receive coaching and exposure to science-based practices, access to the FUSE Library of Practices, and a $1,000 honorarium. Estrada is one of the facilitators.

“We have over 200 teachers and over 40 districts in our program right now, reaching about 12,000 students,” says Yeager. “And we want to be at one thousand teachers a year. My vision is for every single kid in the state of Texas to be taught by a teacher who knows the principles and practices in the book.”

The “mindset” concept has caught on further, too. Yeager just launched a course with Masterclass — the famous streaming service where anyone can subscribe to learn from the world’s leading experts — along with his longtime collaborator Carol Dweck. It’s called “The Power of Mindset.” The class is designed to help students turn challenges into growth and to optimize performance, just as it’s doing in schools across the country now.

David Yeager, professor of psychology. Photo by Justin Leitner.

HOW TO THINK LIKE A ROMAN

IBy Alizeh Kohari

f classicist Andrew M. Riggsby had to give a speech about his dog Elmer — an extensive and rousing one that he’d need to recall without effort or external aid — he would first visualize the strip mall near where he lives.

“I’d memorize all the stores, lock that layout down in my memory,” he explains. These are his loci. “Then I’d place an image of Elmer outside the first store; that’s where I tell the audience I’m going to speak about him. The second image, in front of the second store, might be of whipped cream, because there’s this great story of him jumping up on our dining table to get into a bowl. Then maybe an image of a tennis ball because he likes to play with us...” These are Riggsby’s imagines.

What Riggsby is describing is the loci method, a millenia-old mnemonic that can help you recall pieces of information (imagines) by mentally situating them in a location (locus) that you know well. It’s how orators like Cicero and Quinitilian were able to hold forth for hours on end in high-stakes settings — funerals, political assemblies — without veering off script. The technique is well-known. You might have

Rather than togas and aqueducts and gladiatorial battles, Riggsby mostly thinks about how ancient Romans thought.

come across a version of it without even realizing it, in the TV series Sherlock or the Booker Prize-winning novel Wolf Hall. Riggsby is describing it to me, however, to make a finer point. The method, he says, is strictly useful for recalling information in a precise order, not if you’re looking to improvise a little.

It’s an argument he’s exploring in his current book project, Reading Roman Minds, an eclectic set of case studies that he describes as “an attempt to write the history of the ancient world with help from cognitive science.”

Like many men — a startling number if a viral TikTok trend from last fall is to be believed — Riggsby thinks often and at length about ancient Rome. Unlike most men, however, the

Lucy Shoe Meritt Professor in Classics (and professor of art history) has devoted his life to its study. Rather than togas and aqueducts and gladiatorial battles, Riggsby mostly thinks about how ancient Romans thought. Along with the loftier aspects of classical knowledge, such as rhetoric or philosophy or literature or antiquity’s other formalized disciplines, he also studies the more mundane: lists, tables, weights and measures, maps, and political advice letters. Riggsby, simply put, is interested in the different ways in which ancient Romans processed information on the page — or on walls or wax tablets — and in their heads. Riggsby hasn’t yet delivered a lecture using the loci method, but “I really should, just for the practice,” he says, chuckling. “In class, I’m usually projecting an outline so my students can see it.” He pauses, before adding, “But it’s remarkable to read the technical literature where people are introduced to this technique and 30 minutes later it has a measurable impact on their ability to memorize things in order.”

When Riggsby began work in this area a decade and a half ago, he spent a year as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome. “Conversations there always began with, ‘What are you working on?’” he recalls.

Riggsby’s dog Elmer in a real-life version of a scene that could be used to help remember a speech about him.

Photo by Andrew Riggsby.

Wall painting from the House of M. Lucretius Fronto in Pompeii. The element highlighted in red on the left, which suggests that the painting is expanding beyond the frame, is an example of a recurring motif in such paintings that Riggsby is studying. Photo courtesy of Andrew Riggsby.

Andrew Riggsby blends classics with cognitive science

“And I found myself saying over and over, ‘Well, it’s this and also this.’ One part was about how ancient Romans deliberately organized information, usually in writing, that could be studied in sort of a technological way. And the other part was about how their brain was doing the organizing for them.” These projects, he realized, were separate ones. He set to work tackling them one by one, in that order.

The first line of inquiry culminated in Mosaics of Knowledge: Representing Information in the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2019), a book that casts a fresh look through the lens of the history of technology at inscriptions, artworks, and other small artifacts originating in the Latin-speaking world between 200 BC and 300 AD. Riggsby studied how and when Roman administrators used an index or a table of contents, for instance, or how muralists conceptualized space in landscape paintings.

Reading Roman Minds is the second part of his now bifurcated project, currently in progress with the help of a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. The book is being built around a set of specific examples from the ancient Roman world, which Riggsby considers in conjunction with modern scientific findings. The loci method is one of them, which he examines as a plausible solution to the cognitive challenge of “serial memory.”

The production of Roman jurisprudence is another, which Riggsby considers through the contemporary framework of “distributed cognition.”

A different example considers the many words in Latin to describe fear, which Riggsby is examining through the lens of modern linguistics, amid ongoing debates over whether the words all mean exactly the same thing. Another explores seemingly odd motifs in Roman wall paintings. The diverse assortment of cases is unified by the classicist’s overarching interest in “how modern science can both resolve old questions and open up new lines of inquiry,” as well as what history can offer back to cognitive studies.

First articulated in 1995, the distributed cognition theory proposes that thinking doesn’t just take place within the brain of a single person but can extend over time, space, objects, and other people.

First articulated in 1995, this theory proposes that thinking doesn’t just take place within the brain of a single person but can extend over time, space, objects, and other people. An often-invoked example of distributed cognition is the navigation of ships before the advent of satellite systems, which involved many sailors above and below deck working together to decide how to steer the vessel. Ancient Roman jurists and their writings, Riggsby argues, produced answers to legal questions in a similar manner.

Riggsby credits much of his interest in crossing back and forth over the seemingly daunting divide between the humanities and the sciences to his background. It was just in the water growing up. His great-grandfather and grandfather were both psychology professors. His father was a scientist and his mother had science degrees. Once he decided to become a professor — “I didn’t even really decide that; it just never occurred to me to do anything else” — he considered math but ultimately opted for classics. As a graduate student at UC Berkeley, his department was housed in the same building as linguistics. “They were really into all this cognitive stuff. It’s where George Lakoff taught,” he recalls. “And so,

“I think this sort of work would be very hard to do if you were 30; you just wouldn’t have enough time to acquire this kind of knowledge in a lot of different places.”

just by hanging out with those students, I was picking up a certain amount of that.”

Riggsby, who is nearly 60 now, is finding it easier than ever to think flexibly and work experimentally. “I think this sort of work would be very hard to do if you were 30; you just wouldn’t have enough time to acquire this kind of knowledge in a lot of different places,” he reflects. He often ends up writing two versions of the same paper, one aimed at classicists, one at cognitive scientists. A recent publication in a cognitive science journal, “What Kind of Cognitive Technology is a ‘Memory House’?” will appear, slightly modified, in his forthcoming book aimed at classicists.

“You can get a fair amount done by a fairly narrow case study structure. I know a lot about serial memory now,” he says.

Along the way, he’s learned to be adventurous in a way that is unusual for a classicist.

“When should you take a chance and say, ‘The best current thinking is this and I’m going to go with it?’” he muses.

“The scientists live with it, right? They publish papers they know could actually be refuted. If we’re going to move in these directions, maybe we have to be just a little more tolerant of the possibility that something better will come up later.”

Riggsby hopes other historians will move in this direction,

despite all its attendant challenges, and that Reading Roman Minds will serve as introduction, encouragement, and guide when they do so. “My real hope here is not so much that I will then do a sequel but to get other people to jump on the bandwagon,” he says.

“Whether you work on France in the 1700s or the Congo in the 12th century, many of the questions are the same.”

Alizeh Kohari is a writer and editor who divides her time between upstate New York and Karachi, Pakistan.

Andrew Riggsby, Lucy Shoe Meritt Professor in Classics. Photo courtesy of Riggsby.

NEW CODE FOR THE SAME OLD DREAMS

Iván Chaar López decodes border technology’s

by Lauren Macknight

past and future

Adecade ago, when Iván Chaar López first began researching drones, his Tumblr webpage served as a kind of makeshift digital archive filled with images, articles, reports, and videos he came across online. Some were cheerful depictions of drones delivering pizzas and presents, but a few more sobering pieces detailed drone strikes and deployment for surveillance in the Global War on Terrorism. The striking contrast between the two aesthetics would ultimately prove to be an impetus for his work examining the intersection of technology and border control.

“I’m less concerned about neat continuations of cause and effect over time,” he explains. “I’m more interested in moments of disturbance or emergence, moments when things congeal and come together to create a slight shift, and moments when things fall apart.”

Now an assistant professor of American studies at The University of Texas at Austin, Chaar López studies how drones and other information technologies have evolved from

tools used in aerial defense into instruments of border control. And while contemporary policy discussions around border enforcement often center on whether AI-powered systems can outperform physical walls, Chaar López poses a more fundamental question: What values and politics are embedded within these technological systems themselves? We tend to believe that a virtual border is a contemporary conception made possible by things such as drones, computers, and artificial intelligence, but in his recent book, The Cybernetic Border: Drones, Technology & Intrusion (Duke University Press, 2024), Chaar López argues that the roots of automated border control run deeper than we realize.

Growing up in Puerto Rico and in a family divided between those who advocated for statehood and those who wanted independence Chaar López experienced politics not as an abstract concept but just as life as he knew it to be. The debates that often broke out at family dinners were about politics, but they were also about competing visions of

belonging and sovereignty, and from these discussions Chaar López gained an intimate understanding of how political frameworks shape personal lives. This understanding would in turn inform his scholarly work on border technology.

Chaar López traces the first major attempt to digitize border enforcement to an experimental “electronic fence” built along the U.S.Mexico border in the 1970s. This network of ground sensors, computers, and radio transmitters emerged during a period of mounting anxiety about unauthorized migration one not so unlike our current time following changes to immigration law that led to a dramatic increase in apprehensions of “deportable aliens.”

But the electronic fence represented more than just a technical response to what was seen as a failure of the immigration system; it fundamentally transformed how the border itself was conceptualized, says Chaar López. By converting human movement into data points footsteps becoming seismic readings, body heat translated into infrared signals the system reduced complex human migration into abstract information flows to be monitored and controlled and a territory produced through the policing of its “intruders.” Notably, this technology was adapted from the “McNamara Line” used in the Vietnam War, an

artificial barrier across the demilitarized zone between North and South Vietnam consisting of listening devices and sensors alongside traditional defenses such as land mines and barbed wire. The McNamara Line example, he says, highlights how domestic border control borrowed from military operations abroad and how the U.S.-Mexico border functioned as a laboratory for the U.S. military. And despite frequent malfunctions, with sensors triggering false alarms or failing to detect actual crossings, Chaar López shows that official enthusiasm for automated enforcement remained high in government and tech circles.

These early border technologies were never neutral tools for processing migrants more efficiently. Instead, Chaar López says, they

Photo by Jonathan McIntosh via Flickr, remixed by Lauren Macknight.

were deliberately designed to transform individuals into “data bodies” that could be more easily categorized, tracked, and managed. His research also demonstrates how these systems specifically targeted Mexican migrants, embedding racial bias, he argues, into their fundamental architecture.

This fusion of race and technology persists, he says, in today’s border surveillance systems. Chaar López points to Anduril Industries’ current work with U.S. Customs and Border Enforcement, including their Lattice surveillance system an AI-powered sensor fusion platform as a contemporary example of how networked technologies reproduce and maintain borders. In many ways, he says, today’s AI-powered border surveillance is simply executing code written half a century ago, continuing the ideal of automated control — and its inherent biases that became embedded in America’s approach to border enforcement long before the digital age.

At UT Austin’s Border Tech Lab, which he directs, Chaar López continues to examine how these historical patterns manifest in modern border enforcement alongside broader research on computing in the Americas and digital technology and precarity. The lab investigates the technopolitics of digital systems and information infrastructures and is presently tracking the full scope of Texas’ computing infrastructure — from the mining of earth elements to the construction of semiconductors, data centers, and platforms. This work parallels Chaar López’s focus on technopolitics but employs more traditional methods of technological analysis.

Chaar López’s research methodology is deliberately unorthodox a hybrid of media archaeology and ethnic studies. He draws from an expansive list of artifacts, including promotional documents, government memoranda, surveillance footage, and protest art. The goal, he says, is to allow him to decode something essential about how border technologies function, to expose the gap between how these systems are sold to the

public and how they actually operate on the ground.

“When you hear about advances in digital technology at the border or in our daily lives it’s with a language that emphasizes the immaterial, the ethereal, the cloud,” he says. “As if it’s something that rises above, away from us. But I’m interested in grounding understandings in physical matter and material relations.”

Drawing from years of research, Chaar López argues something deeply unsettling: the future of border enforcement is less about efficacy than the illusion of it. While tech companies pitch ever more sophisticated systems of digital walls powered by machine learning and AI surveillance, Chaar López points to what he sees as the most telling part of this story how little the actual success of these systems matters to those in power. In his studies of automated and artificial barriers used in military defense to his analysis of contemporary border technology, Chaar López identifies a consistent pattern: sensors can misfire, algorithms can fail, and drones can crash, but the imperial promise of perfect technological control remains irresistible to those who wish to maintain power. “Technology, after all, includes the desires of control programmed into hardware

and human practices,” Chaar López explains. This seductive vision persists not because it works, but because it offers the illusion of clean, automated authority without the messy reality of human movement and resistance. And until we confront this fundamental political reality or imagine our way toward creative alternatives, Chaar López says, we’re just writing new code for the same old dreams of empire.

Iván Chaar López, assistant professor of American studies. Photo courtesy of Chaar López.

Image created using Adobe Photoshop AI/Adobe by Lauren Macknight.

CARMEN,Chameleon

Jennifer Wilks tracks an opera heroine’s many guises, from Bizet to Beyoncé

By Michael Agresta

Jennifer Wilks began her newest book project with a seemingly simple question: “Why are there so many adaptations of Carmen set in African diasporic contexts?”

George Bizet’s 1875 Carmen, one of the most-performed operas of all time, is based on a far lesserknown 1845 novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. In neither of those 19th-century texts, however, does the lead character Carmen, by now a globally recognized archetype

of an alluring and self-possessed woman living outside both the law and romantic conventions, have African ancestry. Instead, Mérimée and Bizet situate the character in Seville, Spain, among the Roma community, a group with a complex diasporic history of its own, tracing back to the Indian subcontinent.

How, then, did Carmen — a cigarette factory worker (and later outlaw smuggler) who embarks on a tragic affair with the dragoon corporal Don José,

ultimately dying at his hands when he realizes he can never permanently possess her — become a Black icon?

Wilks’ new book, Carmen in Diaspora: Adaptation, Race, and Opera’s Most Famous Character (Oxford University Press, 2024), approaches that question through a series of deep dives into performance analysis and cultural history across France, Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States. Along the way, Carmen herself comes into focus as a historical character with a life of her own, appearing again and again across epochs and continents, enticing us and challenging us to measure the great changes in our notions of freedom and female power.

“I became interested in how performers were taking on this role and applying it to different cultural contexts,” Wilks says. “Also, how this role has played an important part in the careers of so many of the women who have performed her — for good and for bad.”

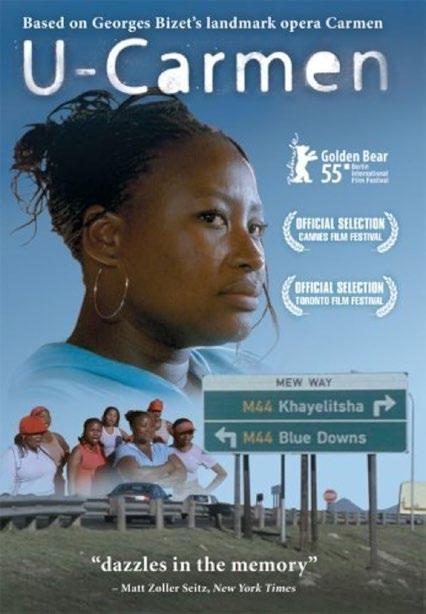

The subject first occurred to Wilks, now an associate professor at UT and director of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, when she was living and teaching in France in 2006. At a Paris independent cinema, she caught a repertory

“ I became interested in how performers were taking on this role and applying it to different cultural contexts.”

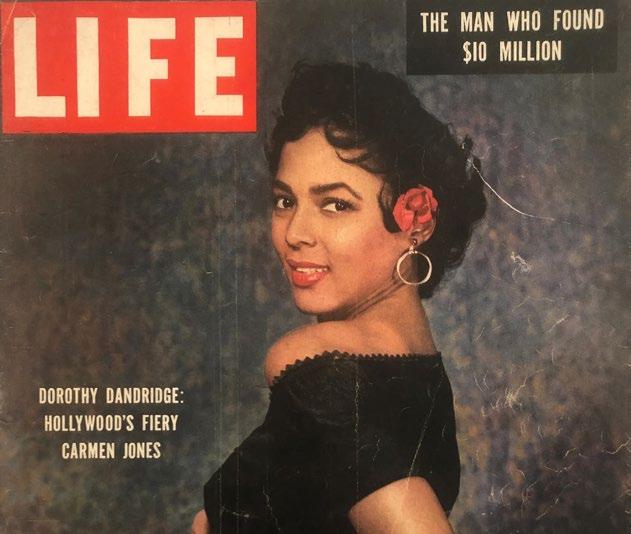

Playbill of Carmen Jones . Image courtesy of Wilks.

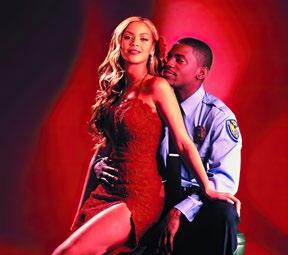

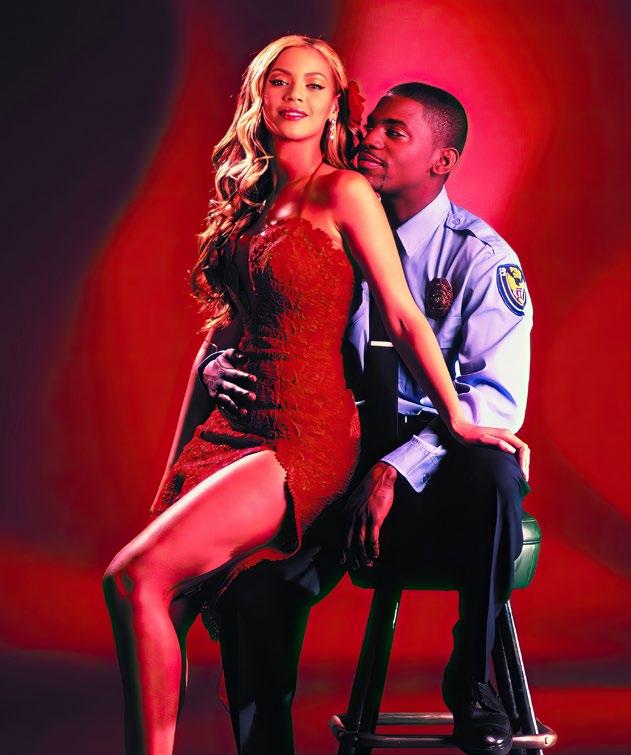

Publicity photos of Beyoncé Knowles and Mekhi Phifer for MTV’s Carmen: A Hip Hopera , from New Line Television.

screening of the South African film U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, which had won the Golden Bear — that is, top prize — at the 2005 Berlin Film Festival. Wilks was blown away by the depth of cultural exchange and reinterpretation on display in the film.

“It was such a stunning juxtaposition of contemporary

1954 film version of the Oscar Hammerstein II stage musical, which uses some of Bizet’s music and stars Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte. Another example that came to mind was Carmen: A Hip-Hopera, a 2001 TV movie starring a young Beyoncé Knowles, which aired on MTV to much fanfare about its firstof-its-kind blending of hip-hop and operatic musical tropes. Both films are set in Black milieus in the U.S.

Wilks found a key to understanding Carmen’s resonance in America in an introduction that Hammerstein wrote to the libretto of his stage musical in 1943.

South African culture, because it’s set there in the early 2000s, and 19th-century French culture, because it is sung through to Bizet’s score,” she explains. “And it just worked brilliantly.”

After the show, Wilks thought back to other adaptations of Carmen she’d seen. These included Carmen Jones, the

“Hammerstein has this phrase, ‘The Gypsy is to Spain as the Negro is to the U.S.,’” Wilks says. “There are some problematic stereotypes that he leans into as he expounds on that idea, but what he is tapping into are very real similarities and resonances between the history of Roma populations in Europe, especially Spain, and African Americans in the U.S. and people of African descent more broadly.”

“They’re not shared histories, but they’re resonant histories,” Wilks says.

For instance, Wilks points out, Roma have had an uneven rela-

tionship to citizenship in Spain and elsewhere in Europe and have been subject to negative stereotypes. Also, Roma women are sometimes exoticized as a desired “other.” In the book, Wilks describes Carmen’s body as “one that tantalizes in its deviation from the presumably white standard and threatens because of its revelation of the fundamental instability of that standard.”

Here in America, the parallel but unequal careers of Dandridge and Beyoncé, an almost-A-lister of Golden Age Hollywood and the present-day genuine article, provide one of the most moving storylines of Wilks’ book. She includes a reproduction of Dandridge’s 1954 Life magazine cover — the first time a Black woman had ever been featured on the cover of that periodical, which was central in defining the values of postwar U.S. culture.

In this image, Dandridge stands angled away from the camera, glancing back enticingly over a bare shoulder. She wears a red flower in her black hair, a hoop earring and jangly bracelets, and places one hand on her back hip, as if mid-step in a flamenco. The cover text describes her as “fiery.” In the costume of Carmen, whose indominable charms eventually drive her jilted lover Don José to violence, Dandridge

“ It symbolizes this moment of opening, of possibility.”

enters American living rooms as both an exotic flavor and a pathbreaking studio star in the making.

“To land a Life magazine cover for any performer was a huge deal in the mid-1950s,” Wilks says. “It means you are all-American, you are at the top of your game. And then for a Black woman performer to land

a cover was even more significant. It symbolizes this moment of opening, of possibility. It means that Dorothy Dandridge as a performer has arrived, but it also points to broader strides that African American performers were making, in fits and starts, but in a significant way in the 1950s that they had not been able to make previously in the film industry.”

Associate professor and Warfield Center director Jennifer Wilks.

Detail from Nov. 1, 1954 cover of Life. Photo © Time Inc.

Carmen Jones earned Dandridge an Oscar nomination for Best Actress, another historic first for a Black woman. Yet for several reasons, including an explicit line in the Motion Picture Production Code (not removed until late 1956) forbidding interracial romance onscreen, her career never reached the heights envisaged by the Life cover. Dandridge died of a possible overdose 11 years later, performing in nightclubs to make ends meet.

As Wilks compares Dandridge’s career trajectory to that of Beyoncé a half-century later,

able to do after the Hip-Hopera speaks to the agency and the ingenuity that the character of Carmen exhibits,” Wilks says. “It’s interesting to think about the breadth and depth of the career that she has gone on to have, and the ways in which the early 2000s was another moment of opportunity in U.S. pop culture, but one where the window stayed open. Whereas in the ‘50s, with Dandridge, because she wasn’t able to access that agency and flexibility, that window closed for her quickly after Carmen Jones.”

“ Carmen has become an eternal, almost infinitely adaptable figure since the 19th century.”

directed by men, do lean into those complications in many ways, but I would be curious to see how more women interpret this work.”

Wilks describes Carmen as, at its core, the story of a woman with boundaries, one who sings in her first and most famous “Habanera” aria, “If you love me, beware!”

a major shift is evident. The mononymous mega-star was beloved by fans of her girl group Destiny’s Child in 2001, but she was not a big enough name to even earn Carmen:

A Hip-Hopera a theatrical release. Today, Beyoncé might be bigger than Carmen herself in terms of global recognition and legacy. Wilks attributes her success to both good historical timing and an ability to dictate the rules of her game in a way that Dandridge could not.

“I wouldn’t say that Beyoncé created a Carmen playbook for her career, but what she was

Much of the heft of Carmen in Diaspora is devoted to lesserknown adaptations of the source story. Wilks came to the topic as a scholar of Black modernism in the U.S. and Caribbean, and she begins her investigation with an analysis of “echoes of Carmen” in the novels of Wallace Thurman and Claude McKay, two writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance. This section underscores from the start the fact that it was Black creatives as much as those of European descent, like Hammerstein, who built the connection between Carmen and the African diaspora. Wilks also devotes serious attention to Carmen la Cubana, a 2016 musical which readapts Carmen Jones’ story back to the stage and connects her to the story of the Cuban Revolution.

Wilks says the most fortuitous moment of her research was discovering Karmen Geï, a Senegalese film that first premiered at Cannes Film Festival in 2001. This adaptation finds a way to make the Carmen story sing in a fully Senegalese setting, using none of Bizet’s music; instead, the filmmakers employ a mix of traditional Senegalese music and American jazz. Wilks describes it as a sophisticated work that is the product of a post-colonial culture steeped in the French classics yet confidently speaking to a homegrown as well as international audience.

“It’s a testament to how people in Francophone societies that were colonies of France know French culture, but their work can be wholly Senegalese,” she says. “It is not a subordinate relationship to French culture. It is a peer relationship, and Senegalese culture is just as prominent. The richness of

Senegalese culture is absolutely center-stage in that work. It’s probably my favorite adaptation.”

While Wilks sees many reasons to celebrate the role of Black creatives in claiming and transforming the legacy of Carmen, she does note with some disappointment a lack of female creative voices in the examples she’s found to write about. While the South African film U-Carmen eKhayelitsha credits female co-writers, most of the authors and directors she writes about are men.

“That’s important, because for so long Carmen has been known as this femme fatale,” Wilks says. “She’s the woman who lures men, in particular Don José, to their ruin, and she’s been reduced to that. That certainly brings dramatic tension to the work, but it’s a much more complicated story. The adaptations that I write about in the book, those

Fortunately, woman-directed productions of Bizet’s Carmen — like the one at Austin Opera in May 2024, or the Metropolitan Opera’s New Year Eve 2023 production — are becoming more common, Wilks says. What remains is to see more women, particularly in the African diaspora, carry on the rich tradition of adaptation.

“Carmen has become an eternal, almost infinitely adaptable figure since the 19th century,” Wilks writes in her book’s introduction. We can only expect that entrusting Carmen’s story to new generations of female storytellers and directors will reveal further, unexplored aspects of what Wilks calls her “unruly, powerful womanhood” to the world.