Tracing Home 寻 家

《寻家》是陈立于2024年在云南贡山雾 里村驻地创作的艺术实践集。

Tracing Home is a collection of artistic practices by Li Chen, based on her artist residency in Wuli Village, 2024.

《寻家》是陈立于2024年在云南贡山雾 里村驻地创作的艺术实践集。

Tracing Home is a collection of artistic practices by Li Chen, based on her artist residency in Wuli Village, 2024.

10幅照片构成的摄影系列,每幅100x100cm。

Series of 10 archival inkjet prints, 100x100cm each.

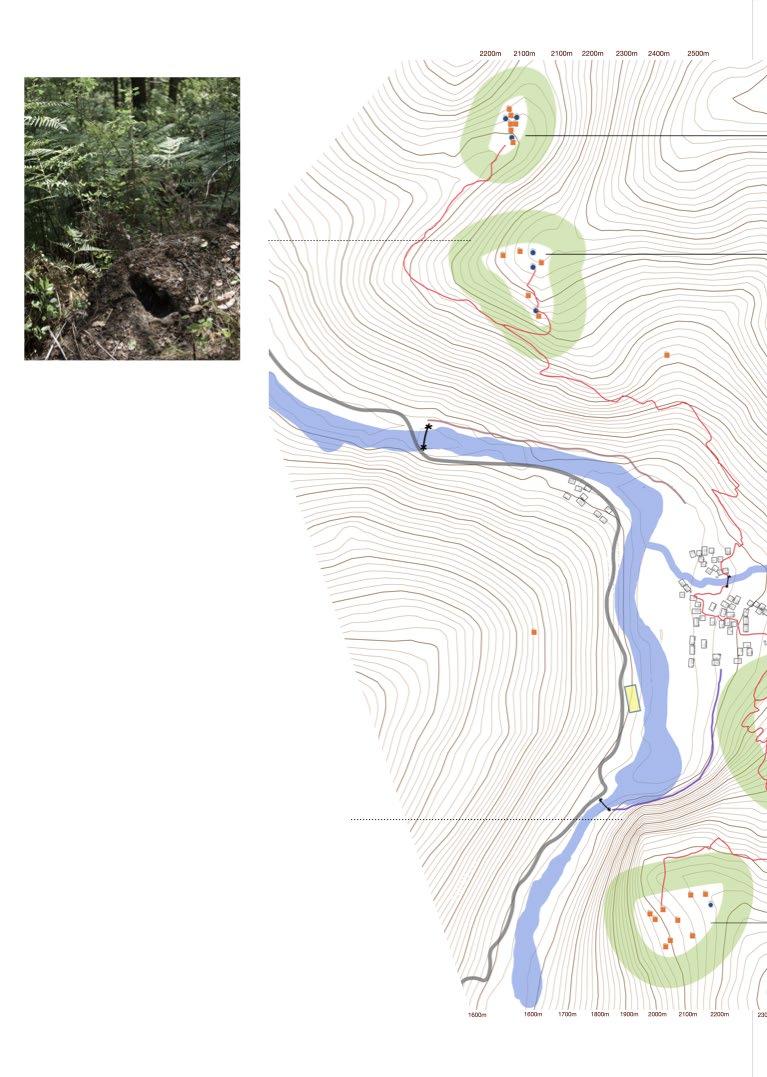

《曾经的家》纪录了雾里村山上的家宅废墟。本系列用一个特定的构图方 式,即把(曾经存在过的)房屋置于画面中心,不论它们的现状如何。这 些安静的照片揭示了一种矛盾的状态,一方面是家宅之不在的存在,另一 方面是地点作为记忆与归属的场域,尽管已经被自然淹没。

Once Home (2024) documents the ruins of mountain houses in Wuli Village, a small Nu ethnic village located in the Nujiang Grand Canyon in Yunnan. Taken in a composition that centralises the (former) houses regardless of their current state, the quiet images reveal the paradox that exists between the absent presence of the houses and the place as a site of memory and belonging, albeit overtaken by nature.

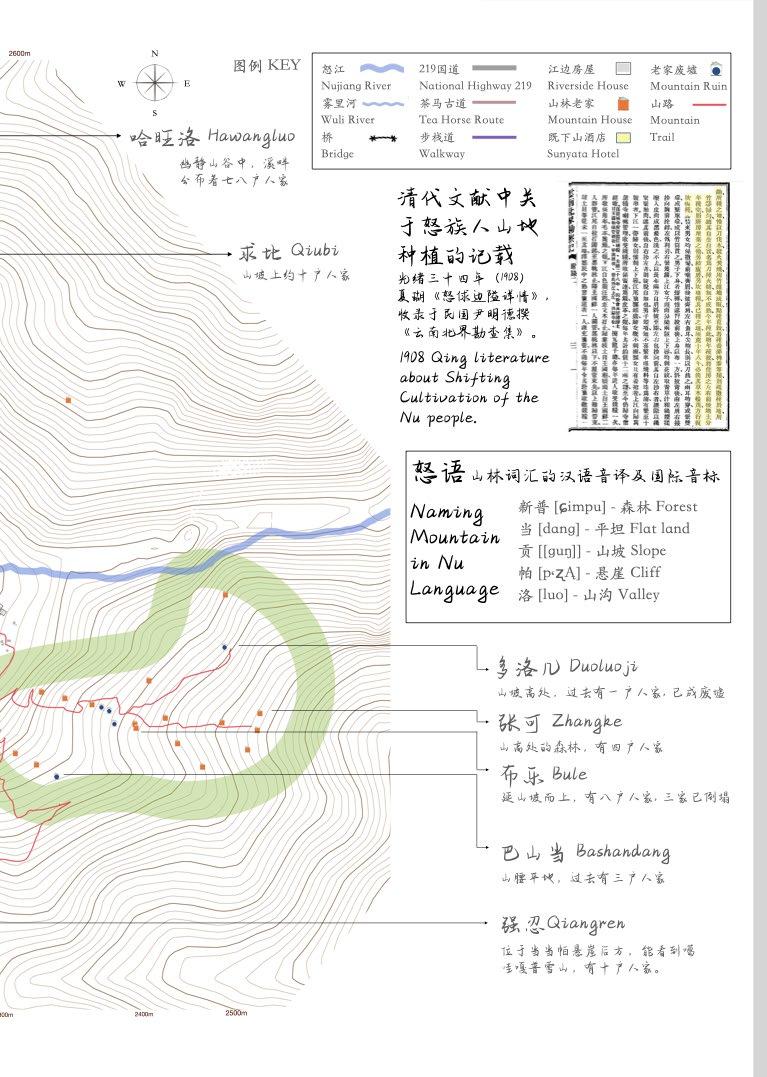

陈立随着村民前往山林中,过去的家屋所在,它们有些在卫星地图上房屋 已经消失。经过五天的徒步,她重新绘制了雾里村的地图,借助GPS工具标 记了村民们山上的家的地点和路线;并把村民们的山上生活的记忆,糅合 在摄影与书写的实践中。

Li Chen followed the villagers into the mountains, where their past homes once stood, some of which had already disappeared from satellite maps. After five days of hiking, she re-mapped Wuli Village, using GPS tools to mark the locations and routes to the villagers’ mountain homes. In addition, she wove their memories into her experimental practice of writing with images.

求比那里,有一块有脚印的石头。脚 印是一位很厉害的猎人留下来的。他性 子古怪,别人叫他去打猎,他自顾自地 吹笛子。等到别人都出门了,他一步跨 到噶哇嘎普雪山,猎到两只动物,一只有 一个头两个屁股,另一只有两个头一个屁 股。然后他一箭射到了家里的中柱,箭到 人也到。家人回来,他已经把肉煮上了。

In Quibi,there is a stone with the footprints of a legendary hunter. This hunter had a weird temperament. When others asked him to go hunting, he ignored them and played the flute himself.After everyone else had gone out, he took a step to the sacred snow mountain and hunted two animals. One had one head and two butts, and the other had two heads and one butt. Then he shot an arrow into the center pillar of the house, and the arrow hit everyone. When the family came back, they saw that he had already cooked the meat.

以前有一位能干的女子,干活、打猎都和男人一样厉害,因此别人都 觉得她看不上男人。有一次她在当当帕悬崖采岩峰时,她的兄弟把她 的绳索砍断了。她坠下怒江而死。

There once was a capable woman who could work and hunt just as well as men, so others thought she looked down on men. One day, when she was harvesting honey from the rock hives at Dangdangpa Cliff, her brother cut off her rope. She fell into the Nu River and died.

我原来在山上有一栋房子,是结婚以后自己盖的。当

时 办 砍 伐 证 花

冬天山上暖和也不用种地,到处下扣子。

我夏天住江边冬天住山上。

都来帮忙,杀了 一

头猪,肉分给大家。

以前年轻人要到处种地,老人 ,多较比的上山在住

要 放 牛

,还要防着老熊。小时候我也常常住在山

,白天帮忙割猪草、背水,晚上和奶奶一起睡在火塘边。

你在秋天的山上,砍下一百二十棵松。每一棵都带着三 十圈年轮,见识过春夏秋冬的山景,因栖身地不同,有着各 自的洞见。它们将躺在地上争论三个月,直至口干舌燥,达成 一致成为我身躯的骨架。你请老人带路,翻过两座山,挖出深埋的 页岩——蜥龙的足印,万年前雨落下的痕迹,被压实的硅基记忆如书 页细密。古老的故事将被晾晒在我的头顶,成为我的智慧。你 向山神献祭苞谷、松枝和烧酒,请喇嘛诵经。沾染过来自所有 村民手掌和肩膀的汗水,我渐渐成型。天窗下,你铺上泥巴,垒 起三个小石柱,置上黑铁锅,给予了我的心脏。你和客人们围 着主柱唱歌跳舞,泼撒面粉,再点燃松枝给火塘升起火,为我取 名,家。我有一只朝圣的眼睛,一扇凝望噶哇嘎普雪山的小窗; 我也有世俗的耳朵,村里的闲谈、命运起伏,都不对我隐瞒。

你日复一日地让我的心脏跳动,于是我分享着你的丰收、猎 获、爱情、亲情和友情,也见过你的饥饿、贫穷、苦难。你越 来越老,你把房子传给你的小儿子,他后来又传给他的儿子。

日子就这么过着,有人在的时间越来越少。直到某一天,你的 最后一个曾孙再也没有回来。我在漫长的等待中日益沉重, 终于俯身向大地。一棵冬瓜树, 从我裂开的胸口, 探出嫩芽。

就像 最初

我诞

这

生于

片山

林, 也终

将 归于 它。

尽管

无人 与我 告 别。

Home, Place, Memory: Reflection on Artist Residency in Wuli Village

陈立

Li Chen

贡山县雾里村,位于云南怒江峡谷深处。我从上海出发,搭飞机经昆明到保 山后,又再坐车延怒江行驶440多公里,才到达。从219国道眺望对岸,怒江东 侧缓坡上的村庄如同世外桃源。几十栋木楞房错落有致,核桃树、桃树点缀 在房前屋后和田埂边,山间云雾缭绕,十分符合城市游客对原生态村落的浪 漫想象。

Wuli Village of the Nujiang Lisu Autonomous Prefecture is located in the Nujiang Grand Canyon in northwest Yunnan. Departing from Shanghai, I flew to Kunming to take a train to Baoshan. Then, I took a car ride of 440 kilometres along the Nujiang River. After two days of travelling, I stood by the side of National Highway 219 and looked across the river at the village I was about to visit, overwhelmed by its beauty. About sixty wooden houses were scattered on the gentle slope, with walnut and peach trees adorning the front and back of the houses and the farmland. Mist swirled between the mountains above the village, creating a sense of mystery. From such a vantage point, Wuli fit perfectly into the urban tourist’s romantic notion of unspoilt village settlements.

然而,我计划以乡村废墟作为线索来展开驻地创作。于是第一个障碍就 是,看起来雾里村似乎没有废墟。村里曾经闲置的房子已经被既下山重建改 造成用于艺术驻留和民宿的木屋。花了好几天在村子里兜兜转转,跟能说汉 语的年轻村民聊天,我才知道,废墟在山上。对于的村民来说,江边的村庄 只是他们的生活半径中很小的一部分,其背靠的高山和悬崖上,有他们的老 屋。

However, as rural ruins had been my long-term interest and my proposed theme for the artist residency, the first obstacle I encountered was that there seemed to be no ruins in Wuli. The abandoned houses had been rebuilt and converted into luxurious guesthouses. It took me several days of wandering around the village and talking to the villagers who spoke some Mandarin to find out that the ruins were up in the mountains. I realised that, for the local people, the riverside village was only a small part of their lives; their old houses were located on the high mountains.

原来村中一户人家,往往有至少两处房子,分别在江边和不同的深山 处。这种双宅居住模式是峡谷生活所需。数百年来,怒族人散居在山上,狩 猎采集、轮歇式地旱坡耕种。怒人与山的和谐关系在1960-70年代被打破。在 人民公社的高度集体化生产模式下,

全村人被编成生产大队,每天同时出

工,不仅大量开荒,还把轮歇地变为固定耕地,致使山地土壤无法修复,坏 境遭严重破坏。直到1980年代再次改革,推行农村包产到户政策,怒人得以 自行安排生产,重拾传统。进入21世纪后,人与山的关系彻底改变:2000年, 怒江峡谷被列为国家保护区,狩猎被禁止;2016年怒江反对建坝运动胜利, 怒江国家森林公园建立,随之而来的是退耕还林和集中搬迁。现在,村民们 仅在山下耕种,把牛放养在山上,每隔几周上去看看,当天往返。他们山上 的家被规定只能作为“生产用房”保留,供他们在山上放牧或采集时歇脚。因为 不再需要在山上居住,村民们拆掉了山上的房子的卧室和客厅,只留下一间 厨房——火塘和中柱,是怒族人家里最重要的精神象征。随着村里人口的减 少,山上房子无人管理而倒塌的,也越来越多。

In the past, a Nu family often had at least two houses, one by the river and one in the mountains. This dual residence model was necessary for life in the Nu River Gorge. According to historical records, the Nu people lived by hunting, gathering, and practising shifting cultivation until the 1950s. This harmony between man and mountain was first disturbed in the 1960s and 1970s when the People’s Commune was enforced. The mountains were over-cultivated by the highly collectivised production mode, causing severe environmental degradation. After the 1980 reform, the Nu people re-adapted their traditions. It is only in recent years that their relationship with the mountain has changed completely: in 2000, hunting was banned; in 2016, the Nu River anti-dam movement was successful, and the Nu River National Forest Park was established, leading to “Grain for Green” reforestation and centralised relocation. Now, the villagers can only live and farm at the foot of the mountain, while letting their livestock roam on the mountains and checking on them every few weeks. Their houses on the mountain can be kept for “production use”, serving as a resting place while they graze or gather on the mountain. Since they no longer need to live on the mountain, the villagers have demolished the bedrooms and living rooms of their mountain houses, leaving only the kitchen — the fireplace in it has functional and spiritual significance in a Nu household. As the village population declines, more and more mountain houses are abandoned and collapsing.

我随着村民前往山林中他们过去的家屋所在。当村民指着一片石墙基, 告诉我,以前他来过这家串门,我想到了自己童年的家——另一堆碎瓦砾, 在巨大的都市更新工地中。和城市的规划拆迁以大型机器推倒住宅群,把构 成家之建筑的材料变为垃圾相比,山林中无人居住的木楞房逐渐瓦解回归自 然是一个更慢的过程。村民们每次上山找牛或采药时还能看到它们,恍如与 曾经的山林生活进行漫长的告别。

I followed the villagers to where their old houses used to stand. As my guide, Duoji, pointed to a stone wall foundation and told me he had visited this house

before, I thought of my childhood home - another pile of rubble in the middle of a vast urban renewal site. Compared to the massive demolition of urban housing estates by large machines that turn the building materials that make a house into rubbish, the gradual collapse of uninhabited wooden houses in the mountains is a slower process. Every time the villagers climb to check on their livestock or gather herbs, they can still see them, as if bidding a long farewell to their former mountain life.

过去生活的家屋变成废墟,消失在卫星地图上,回忆仿佛失去佐证,漂 浮了起来,变得可疑。但是,关于家的回忆里不仅仅有建筑物,更包括了其 所在的地点。德国文化记忆理论家阿莱达·阿斯曼将承载了家族记忆的地点称 为“代际之地”,它可能是某个人居住的地方,或是其祖父居住的地方。在那 里,个人的记忆与更普遍的、跨越世代的共同记忆融入在一起。雾里村山上 的还剩下的房子和废墟所在的地点都是这样一种代际之地。

The houses of the past have become ruins, disappearing from satellite maps. It seems that memories are also losing ground. However, memories of home are not only about buildings but also about the places where they are located. Aleida Assmann, a German cultural memory theorist, referred to the places that carry familial memories as ‘generationenorte’ (generational places), which could be where a person lived or where their grandparents lived. Whether or not the building still exists, the place matters because it is where individual memories merge with more general, cross-generational collective memories. In this sense, the mountain ruins are also generational places.

有着复杂迁徙历史的怒族人,也在自己的民族历史记忆建构中强调地点 的重要。怒语没有文字形式,他们通过代代口耳相传的口头传统来传承。民

俗学家刘薇在论文中记述了发生在福贡县另一村庄的一场怒族葬礼。老人们 先回顾祖先迁徙的传说,然后祭师站在亡者家门口,面向东方念唱怒族神歌 《送魂词》,“你去的路线由西向东,你千万莫走错了去路;你从此地起

程,到诺拉甲歇歇脚;由拉谷底起程,到然先洛歇歇脚;……你就会到丙鸠 岩,你就会到丙鸠峰;丙鸠岩是阿爷住的地方,丙鸠峰是阿奶住的地方。”神 歌中共有提到二十八个地点,为亡灵指引回到祖先居住之地的路线。

With a complex history of migration, the Nu also emphasise the importance of place in constructing their ethnic historical memory. Without a written language, the Nu memory is passed on through oral tradition. In a 2020 paper, ethnologist Liu Wei recounted a Nu funeral ceremony. The elders first retold the legend of their ancestors’ migration, then the priest stood at the deceased’s door, facing east, chanting the Nu ritual song “Soul Sendoff,” “The road you take goes from west to east, don’t take the wrong path; you start from this place,

rest at Nora Jia; you start from the bottom of La Gu and rest in Ranxianluo; ... you will arrive at Bingjiu Rock, you will arrive at Bingjiu Peak; Bingjiu Rock is where grandfather lives, Bingjiu Peak is where grandmother lives.” The song mentions a total of 28 locations, guiding the souls back to their ancestral homeland.

随着山上不再是可以居住的地方,那些存在过的木屋会渐渐消失,但家 所曾在的地点,可以不被忘记。只要还记得过去的家的地点,记得“回家的路” ,那么或许对于族群、家庭和个体来说,对于自身的历史与认同可以多一些 连续性,少一些断层。

As the mountains can no longer be home, the wooden houses that once existed will gradually disappear, but as long as one remembers the place of the past home, remembers the “way home,” perhaps for the ethnic group, the family, and the individual, there can be more continuity and integrity in their own history and identity, and fewer ruptures.

于是,我的创作大体有两条交织的线索。 一条线索是记录记忆的地点, 包括以山上废墟为拍摄对象的 《曾经的家》,以及重绘雾里村地图、标记山 上老家的地点与“回家”的路线。另一条线索则是用写作(writing with image) 的实验,探索记忆叙述素材与图像的可能互动方式,用这种互动尝试打开更 深的情感维度: 我把从村中听到的猎人传说与清代文献并置作为地图的一部 分;把村民对于山上已经倒塌的老家的回忆,排成回家路线的形状,串联江 边与山上、火塘和老人的图像;把村民告诉我的造房过程用废墟的口吻进行 重述,书写废墟的回忆并搭成房子的形状。

Thus, my practice is composed of two strands. The first focuses on documenting places tied to the idea of home, including the photo series Once Home, which captures the mountain ruins, and the re-mapping of Wuli Village, tracing both existing and disappeared mountain homes and the routes of “returning home.” The second strand takes an experimental approach to “writing with images,” exploring the interplay between memory and visual language to reveal deeper emotional layers. For instance, I transform the villagers’ recollections of their former mountain homes into a mapped journey, linking images as if retracing memory itself. I also give voice to the ruins, allowing them to narrate their own story.

这些关于家、关于家的地点的追溯与不完整的记忆建构,便是我用创作 来对抗遗忘的行动。

These two interwoven threads of tracing home through place and memory, are my small act of resistance against forgetting.

传说故事来自: 李彭华, 李顶天 山上老家的记忆片段来自: 李忠全, 刘春星

与我分享故事的其他雾里村民: 李仕英,王小山,怒秀妹,李志珍, 李玉莲,李文新,古则,陈佳鑫,张平

怒语翻译 :

李仕英, 和勇,李顶天

特别感谢既下山·雾里团队的协力。

Source of folklores: LI Penghua, LI Dingtian.

Source of memory fragment: LI Zhongquan, LIU Chunxing.

Ohter people of Wuli who kindly shared their stories with me: LI Shiying, WANG Xiaoshan, NU Xiumei, LI Zhizhen, LI Yulian, LI Wenxin, GU Ze, CHEN Jiaxin, ZHANG Ping.

Nu-Mandarin Translaters: LI Shiyiing, HE Yong, LI Dingtian.

Special thanks to the assistance of SUNYATA Wuli team.