EDITOR IN CHIEF

Audrey Bohlin

FICTION EDITORS

Clara Oyanguren (Lead)

Allison Cho

Andrew Tinaz

Claire Ireland

Flora Konz

Katlyn Saldarini

Mason Maynard

SECRETARIES

Elsah James

Cole Erickson

POETRY EDITORS

Eliana Burgin (Lead)

Robin Glass

Claire Louise Poston

Savannah Vonesh

LAYOUT EDITORS

Cole Erickson (Lead)

Elsah James

Julia Carey

David Montes

This issue is dedicated in memory of Zac Lacy and Isaac Scharbach

FACULTY ADVISORS: Alan Michael Parker, Zoran Kuzmanovich (emeritus), Scott Denham (emeritus), Ann Fox (emerita)

PREVIOUS EDITORS IN CHIEF : Elsah James, Max Shackelford, Samantha Ewing, Hannah Lee, Ben Caldwell, Raven Hudson, Madeleine Page, Quinn Massengill, Alyssa Glover, Samantha Gowing, Meg Mendenhall, Michael DeSimone, Jordan Luebkmann, Will Reese, Emily Romeyn, Vincent Weir, Mike Scarbo, Vic Brand, Ann Culp, Erin Smith, Scott Geiger, James Everett, Lamar Clarkson, Andrew Haupt, Jimmy Newtin, Catherine Walker, Elizabeth Burkhead, Chris Cantanese, Kate Wiseman, Lila Allen, Jessica Malordy, Nina Hawley, Kate Kelly, Zoe Balaconis, Rebecca Hawk, and Hannah Wright

ALUMNI CONTRIBUTORS: Emily Drew, Russ White, Vic Brand, Scott Geiger, Erin Smith, James Everett, and Ann Chow

By Kathryn Helms

[Photo 1: four girls stand together in their swimsuits, beaming at the camera, a strikingly blue lake behind them on a gorgeous summer day.]

Dear Me of the Box,

I remember how we decided to add this one to the box to preserve our senior summer, like we could capture this moment in time and keep it forever. It hasn’t preserved anything, though, not really. It’s just a reminder of how bad my bleached hair looked.

You’re laughing at the camera. I don’t remember what was funny, but right now, it feels like you’re laughing at me. Ha-ha, I imagine you saying, they like me so much better than you, can’t you see? They did. They do, I mean. They still exist outside of this photo, but you don’t. You don’t exist outside of this box, and I don’t want you to. They probably don’t think about it anymore, and it’s probably for the best.

I still love you inside the box, though. Stay there, but keep being you. Without you, there would be no me.

Yours truly,

You

[Photo 2: a middle aged man and woman with two girls, one in her late teens and one kindergarten-aged. All four have ice cream in front of them and spoons in their mouth, eyes shining with mirth and mischief.]

Dear Me of the Box,

In opening this box, am I exposing you to the real world? Do its contents cease to be a preservation of a time once it becomes the object of my reminiscing?

She’s still alive to you. Do I ruin that if I cry now?

I won’t. I won’t ruin that for you. She’s still alive to you, and you don’t have to be me, not yet. You have a lot of life to live before then. I won’t shed any more tears for her than I shed for you. Neither of you are still here, and I love you both, and because I love you, I won’t disturb the captured moment of time in which you live. I won’t bring you any of my pain before its time.

Yours truly,

You

[Photo 3: one of the girls from the first photo reading a book to the younger girl from the second photo. The teen girl from the second photo is taking a selfie of all three of them.]

Dear Me of the Box,

This was such a sweet moment. What a good friend. I guess we’ve found yet another person in this box who doesn’t exist anymore, haven’t we?

Yours truly,

You

[Photo 4: the teen girl from the second photo holding up a box with a new pair of red shoes with white laces inside.]

Dear Me of the Box,

Something that still exists, huh? The red shoes. They serve me well just like they served you, though I didn’t remember how white the laces used to be until now. The laces aren’t as white and the canvas isn’t as red and the soles are so worn out that sometimes when I wear them I almost slip and fall, but replacing them feels like giving up. It means something to me that after having been so worn down, they haven’t broken to the point of disrepair. I can still wear them, and they still take me where I want to go. I won’t give up on them for as long as I don’t want the people in my life to give up on me.

Mine truly,

Me

By Andrew Tinaz

I ripped your soul out

And made you play with it in front of me. Taut breathing and I Plucked your eye, so attentive To align too many discordant moments,

Then trespassed on quiet grounds so loose I rounded lumps, I rubbed, pushed love to a waist which made you grunt a line. Really, to waste time, watch you turn. Really, to conduct in time those dulcet cries, So the shadows on your walls writhed to collapse and dance and shake with cupped hands over mouths smiling shattered tips of lips, too creased. I covered your eyes

melted hand, drawn tongue to taste I was so happy for you in that echoing place, I watched you fling happy, love that echoing place.

I watched as there was satisfaction on your face. I watched, with my own hollow face.

By Anne Mason Roberts

For old time’s sake, Trace your finger across the rough skin of the football Laying out the route for me to run Across the front yard.

For old time’s sake, Sit with me around the Christmas tree Staring wistfully at unopened presents On the floor in the living room.

By Jade Juana

Skin kissing skin--touching. Sweat glued our arms together, pain and heat filled the room. It was the first ime. Slow penetration, I guess that was the passion. Deep inside, I guess that was the pain. The blissful kisses, I guess that was the pleasure.

Ripped open with no regard for my emotions. Trespassed on sacred grounds without perfomring rituals. A blood sacrifice made us one. You held me, squeezed my hips enough to secure me. Our breathing began to synchronize.

In--ahhh--out

In--ahhh--out

In--ahhh--out

Our movements like waves unbothered. A tsunami not caring what it destroyed in its path. We climaxed like Canon in D Major, a rising symphony of strings at every hearteat, a steady basso continuo. The strings compliment each other. Fingers perfectly placed on the neck ot make harmony as butterflies fill my stomach. And ..then...then...you caught my eye.

A fire sparked a volcano erupted lava flowed down our side and melted our souls into one.

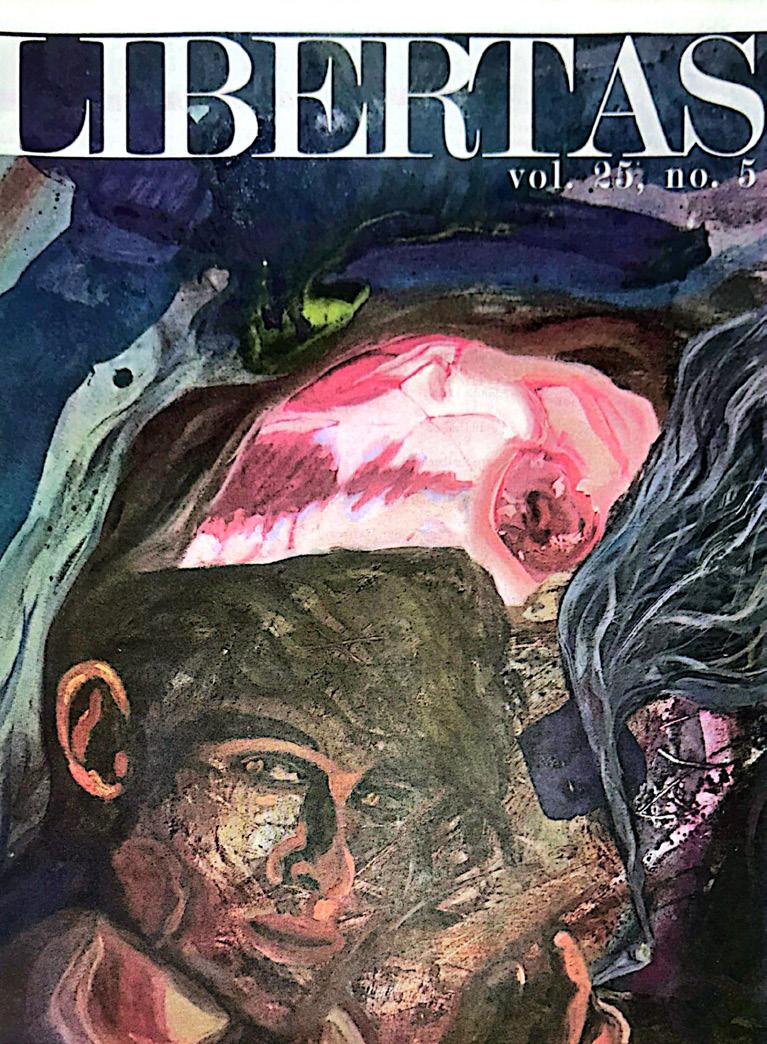

from the Libertas archive

For old time’s sake, Spin me around my room Waltzing to that old record Without a care in the world.

For old time’s sake, Pray with me in the dusty pews in the old church Pray for me, for us, & that God is actually listening.

And please, God, for old time’s sake, Take me back to the time that I was myself. When I was so blissfully confident of Who I was and who You were.

When I could stand up straight and Look people in the eye and smile Because I was happy. And that’s all that mattered.

By Selin Deniz Akdogan

At the side of the busy street, carved into the old wall, was a small door. I stepped into the threshold and the first thing that welcomed me was the laden smell of nostalgia and death. However, there was nothing repellent in it; rather, it smelled beautiful, like old books, ancient churches, and dead roses.

A man, in his sixties, came running. He was limping on his left foot slightly. He halted in front of me, a shallow, wheezing breath escaping his lips.

“You must be the new teacher.”

An intense awareness struck me: if a rat could walk upright, it would have been this man. He had black irises - orbs of voidmoving rapidly from one corner of the eye to the other. His dull gray hair was short on the sides and on the top, yet it was quite long at the back, reaching the bottom of his neck. His lips were cracked, drawn tight over yellowed, crooked teeth, which he revealed in an uneasy grin. He was wearing a clean white shirt and black trousers, which indicated that he put in the effort to look presentable. He looked friendly, yet I could sense the cunning and maliciousness from him, possibly suppressed by his lack of wit and courage.

“I am.”

“Arnfried.” He extended his hand—clean but marked with calluses, a strange mixture of roughness and care. I met his handshake with equal firmness.

“Eunice. Pleased to meet you.”

He nodded with a smile and turned around towards another wooden door behind him.

“Nice to meet you Eunice. Follow me, let me show you around.”

“Aren’t I supposed to complete paperwork? Sign something?”

With a quick, dismissive wave of his hand, he replied, “No, not right now. You will, of course, but no rush, sweetheart.”

As he spoke, the weight of a thick German accent vibrated through each word. With a slow, labored gait, he limped toward the wooden door. His hand disappeared into his pocket, and when it returned, it held a tangled bunch of tarnished keys. He began rifling through them, his lips moving in a low, resentful mutter, the sound rising with growing frustration as if he was quietly cursing each key that wasn’t the one he needed.

At last, he gave a triumphant “Ah!” and slid the right key into the lock. The door gave way with a long, reluctant groan, opening onto a small but hauntingly beautiful garden. A narrow stone path laid before us, its surface weathered, winding under the shadow of trees on either side. At the heart of the square rose a tall, spiraling stone pillar, crowned by a large cross. Around it, stone flowers coiled, and water cascaded down the spiral’s curve, its gentle sound whispering as it echoed faintly against the enclosing walls.

“This is not what I imagined.” I said quietly.

Arnfried smiled knowingly and said: “It is an old place. The more time people spend here, the more old-fashioned they become. This school has that effect on people.”

I looked at him curiously, “It looks like an old hospital.”

“It is, if you think about it,” he answered, his face softening with an unexpected warmth. “We take in kids who lost their families, we give them a home, education, and love. We heal them, in many ways.”

Arnfried spoke more intelligently for someone who reminded me so much of a rat. But then, I thought, rats are clever creatures after all, are they not?

“As you can see, this is the main garden,” Arnfried said, his voice softening. “The children’s favorite place. If they aren’t in class, eating, or sleeping in their rooms, they’re here.”

I murmured, almost to myself, “I can see why. It’s… beautiful.”

“It’s not much, really. But it’s full of silence and safety.”

I nodded, observing him with a curiosity I couldn’t quite suppress.

“How long have you been here, Arnfried?”

“Ah! Let’s see… twelve years now, I think. Yes, quite some time, isn’t it?”

“Twelve years is a long time. Why did you start working here?”

“Well, when I was thirty-three, I left Germany. I had a girlfriend back then. Wrote her a letter that simply said, ‘I’m leaving Germany. Take care of yourself.’ That was all.” He chuckled, shaking his head at some distant memory. “I wasn’t much for sentiment, you see.”

Something sharp twisted in my chest. Here was a man who had been loved, and he’d left it all behind without a second thought. The thought made me inexplicably resentful.

“Why did you leave?” I asked, the words slipping out more harshly than I’d intended. Arnfried didn’t seem to mind.

“I wanted a different life. Anyways, I came here but when I did, it wasn’t very bright for me. I didn’t have much savings when I left Germany. I used to be a violinist, you see… played for the Northern Symphony Orchestra.”

I looked at him with surprise.

“There is not much money for classical musicians,” he chuckled. “I truly underestimated how hard it would be to leave my country. Not a day went by that I didn’t feel the ache of homesickness. I couldn’t find a job here, and I started living as a homeless. I barely spoke English and it took me a while to learn. It’s a hard thing, you know—being without a place, without anything. I spent years in the streets, but then, I found a job here as a groundskeeper, and later as a German teacher. Been here since.”

I nodded, feeling the weight of his words settle between us. After a moment of silence, filled only with the soft rush of water from the spiral and the distant chirping of birds, Arnfried spoke again.

“Why are you here? I heard you studied journalism. What made you decide to become a literature teacher?”

“Is it unorthodox?”

He laughed heartily. “Not unorthodox, no. But certainly unwise. The pay is pitiful.”

“I am well aware,” I smiled.

I walked over to a nearby bench and sat down, and not two seconds later, Arnfried was next to me, lighting a cigarette.

“In high school, I tried smoking once,” I said, almost absently. “A couple of cigarettes with friends. I thought I was immune to it—like it couldn’t take hold of me. Back then, I was certain I was immune to all addictions.” I smiled at the thought, the memory strangely nostalgic.

Arnfried chuckled. “Good for you,” he said, holding his cigarette between his fingers like he was examining it. “I tried one of these damn things, and that was it. Hooked for life.”

I smiled and kept going. “Of course, I realized eventually that no one’s immune. Everyone’s addicted to something—cigarettes, alco hol, people, places. In my case, I just ended up addicted to isolation. It became… comfortable, like a cozy cottage in the woods.”

Arnfried listened closely, and suddenly, the background sounds of the water and birds faded.

“The real problem came when that habit collided with another feeling. People, you know… they yearn for isolation and yet crave love, and those two desires don’t mix well. They’re like opposing forces, constantly clashing, and the chaos they cause in your mind… it drives you a little mad. Eventually, you have to pick one. Either you give up the isolation, or you give up wanting to be loved.”

I took a breath as I felt my mouth go dry.

“I had the deep need to be loved, Arnfried, and just as strong, I had this pull toward being alone. I was too proud to relinquish my isolation, yet too human to relinquish love. So what choice did I have?”

I glanced at him, seeing his curiosity, and somehow, that gave me a strange satisfaction.

“I decided to write, Arnfried. I poured my wants, my frustrations, and all my contradictions onto the page. I came here to finish my book in a peaceful place, and maybe help students learn to write.”

“I can sense that from your words, sweetheart. There is something writerly about the way you talk. You speak in a weird, fancy way.” “Do I?” I asked, flattered. “Thank you.”

By Cole Matthews

And I can imagine it like it was yesterday

The smell of warm pancakes

Wafting up those well worn stairs

The calls of my parents

Beckoning for breakfast’s beginning

The whole day ahead

Play soccer and lunch

watch football with dad

then homework (of course)

It all seemed so simple

The life I was gifted

But as time’s worn on

The more duties I carry

It seems so confusing

Always left asking

“What am I doing”

But I can forever look back

On those days not so long ago

And remember that smell

From my warm, comfy bed

And the smiles of loved ones

As I trekked down those stairs

By Michael Weiland

“In times when nothing stood, But worsened or grew strange, There was one constant good, She did not change.” - Larkin

Had at once I loved, And revealed to life’s pestilence, my soul To which my sentiments vestiges were emptied, Soon followed a void, the toll

Why should loves tongue be burdened To evade, and elusive as to evade sight, And my sentiment be cordoned? (Why should Cupid speak so pervasive, And evade his psyche?)

From the chest, the heart is pulled through broken bones,

Into the stale snow blood drips And sinks in where the heart was thrown (Can you ask a solid heart to beat, And expect affectionate diction through cold lips?)

Through this dark night Stands you, a monolith, A welcome sight in this long plight

So should you find my heart (From which I feel doubt), Bring it out of the cold outside And warm it throughout.

In times when nothing stood, And I leave out to rot;

Things worsened or grew strange, But my sentiment stays true;

There was one constant good, She did not change.

By Robin Glass

A camera flash

A moment frozen, forever framed by white plastic: Fall’s faint chill, The breeze that chases everything away, The warmth of your palm while I spill my soul, The cobbles beneath stained in trust and heartache— Your breath on hallowed promises, Remnants of home trickling behind us, Rustling leaves lost to our ephemeral world. Headlights half blocked by the trees, Your temporary halo, My drumming pulse, Your glowing smile. A breath.

Flash

A polaroid tucked behind a Dave & Buster’s card

By Mary Herdelin

A few rented stugby in Rattvik Hugged by a colonnade of wise spruce

Blooming in the distance

Out of the humble porch

Her elbow is made of metal

she will let you know

Her family history, her anamnesis

And if not, the trees will whisper it through the wind

A spray of gentle purple wildflowers

Tiny blossoms, forged shakily to their stems

Left behind from midsummer flower reapings

All overlooked by her gentle wave

The specifics of her face are unapproachable

Left to be filled in by memory

He never liked painting human subjects

The form he could dissect, diagnose, and diagram never could he make subject

Their young love is memory to

Their progeny in the foreground

Blooming, uncontrollable, among the strong tall grass

They cannot control these these wild and tender things

Their young love is memory to Their progeny in the foreground

Blooming, uncontrollable, among the strong tall grass

They cannot control these these wild and tender things

By Nate Green

Steve Taylor is talking about the earthquake in California. His stupid, handsome face is making all the wrong expressions. He’s supposed to be somber, but his eyes are shining, and his mouth is upturned —just at the corners. And he’s dressed all wrong, like he’d rather be in California: sleeves rolled up and strong, tanned forearms glowing under the studio lights. In my opinion, a local newscaster shouldn’t try to be anything he’s not, and Steve Taylor is nothing close to a Californian. It’s a good thing, too. He’s a nice, homegrown boy. I met his mother once—in the supermarket. I’ve never been to California, even if Uncle Scooter went to college there and never shut up about it.

“The trees!” he’d say. “The weather! It never rained, Sherry. Not like here. The sun would come out and stay out, and the world was brighter and easier. And the people, God, the people. So much nicer and prettier and cultured. It’s nothing like Oklahoma.” And he was probably right; it’s nothing like Oklahoma. They have sex, sin, and movies. We have God, cattle, and family. It’s an easier life, a simpler life, here. Which is why I never left. That and I couldn’t have, since I married young and Rob, bless him, never wanted anything to do with the rest of the world. We went to the Florida panhandle once. That was nice.

Rob put his toes in the white, white sand, stretched out on his back, and sighed deep sighs. His stomach reddened in the sun, and Lord help me if I touched it after. “Jesus, Sherry!” he’d yell. “Don’t touch me like that. You know I’m burnt. If you’d have gotten the sunscreen, I wouldn’t be in this mess. Sun blistering. Jesus.” He’d left the bag back home, on the kitchen table. But I’m not one to cause trouble, so I didn’t say anything and never did. If it could be my fault, if he could blame me and feel a little lighter, then that was fine with me.

“Carry the burden,” my mother always said. Sometimes I think it broke her. Sometimes I think it let her go happy. She died well before Pa, before I left home, and the burden she’d carried crashed down on us. Wham! And we fought, and fought, and Pa became a drunk and never went to church again, Poppy found her way to Georgia and then God knows where, and little Davis, fleeing all this disorder, ran onto the highway chasing his cat. His cat, he called her Button, mewed and mewed and mewed until someone stopped on the side of the road, called the police, and gave Button a new home. That’s what the officer said when he knocked on our door. Pa didn’t believe him. He never did trust cops, but when this one pulled out a piece of bloody fabric from his pocket, he came around to it.

“My boy! My boy!” Pa cried. And he bawled tears of whiskey and moonshine, right there on the flaking porch, and the cop stood there awkwardly, wished him a good day, and scurried away. Maybe that’s why I married Rob. When he started courting me, I told Leslie that he was ugly and uptight, that I’d be damned if I ever gave him more than the time of day. But he wore me down, and time wore me down, and eventually it seemed nice to have a home, no matter who I made it with.

We made it well, had a couple of kids, saw them off into the world, and then saw each other into obscurity. Only, he left me a decade ago, the kids rarely call, and dumb Steve Taylor is most of my company. It’s almost nine. They’ll switch to Jeopardy reruns soon, and I’ll turn the TV off and go to bed. I can’t stand Jeopardy. They all think they’re smarter than me. Better than me. But none of them did what I did. Not one of them. If I had had an easy life, maybe I could’ve studied useless facts all day. But I didn’t.

I’m on the couch. There are old photos all along the walls. Memories, mostly. If I look at a portrait long enough, I forget who they are, and then I dream and dream of all the wondrous things they might’ve done, had they been born somewhere else, sometime else, as someone else. They might’ve been on Jeopardy.

By Clara Oyanguren

Beep. Beth is surrounded by the smell of disinfectant and a steady stream of beeps, letting her family know she’s alive. Her mom gently holds her hand while crying while her dad argues with the doctor. Both are scared to death for their baby girl.

She was just getting some miscellaneous items at her local CVS. She needed toothpaste, floss, Cheerios, Protein breakfast bars, and some Claritin. The weather had been getting colder, and her nose kindly made her suffer the consequences. That Black 2020 Subarro shouldn’t have been in her way, but it was 1 AM, and she forgot to look twice at the road. She didn’t know her latenight cravings and failure to restock her allergy meds would land her in the hospital.

Two days later, she finally opened her eyes. Next to her friends and family, she opened her eyes and said raspily, “Mom, where am I?” As she looked down and noticed the oximeter on her finger—the bruises and cuts—she reached to touch her head and felt the hard material of gauze wrapped around her forehead.

“Sweetie, you had an accident. You’re in the hospital. Everything is ok. You’re ok. God, you scared me.” She said while tears trailed down her cheek.

“Car accident? What happened? Am I ok? Why do I have gauze on my head?” She asked, agitated.

“Beth, calm down. You just hit your head a little too hard, but the doctors are taking care of it.”

“Ok. Were you there?”

“No, sweetie.”

“Mom, who are these people?” she exclaimed as she studied the room and saw two other people sitting by her bedside: a brunette girl with messy hair and sweatpants and a blonde girl with five empty coffee cups around her.

“Sweetie. Beth, these are your friends Lily and Sarah. Do you not remember them?” she inquired worriedly.

“Mom, I don’t remember anything.”

The doctors explained that amnesia is typical of brain injuries. To help her remember, they brought some mementos from her life: a Made In the AM vinyl, a macaroni friendship bracelet, and a worn-out brown leather journal—a time capsule of their time together.

Lily came to visit with the macaroni bracelet. Desperate to get her friend back, she showed her the bracelet and said, “Do you remember when we made this? It was the first day of kindergarten. I was so scared; I knew no one, and none of my daycare friends came to our school. I had no friends. I was already crying by recess when you came, took my hand, and told me you would be my friend. We spent the rest of the day making these bracelets. You were my first friend. ” Holding back tears, she moved to grab Beth’s hand and prayed she remembered.

“Lily? You were my first friend, too.” She said as they embraced each other in a hug.

“You scared, asshole.”

“Sorry. I’m here now.”

Sarah, with Lily’s help, got the courage to visit Beth for the first time since she opened her eyes.

“Hey, Beth.”

“Hi. Sorry about the–”

“No, it’s ok.”

“I bet I liked you, though.”

“Oh, yeah. We had some fun times together.”

“Like what?”

“Well, I brought you this Made in The AM vinyl. The first album we ever bought and listened to together.”

“Really. You helped me stand up from the floor when Jack and his friends pushed me. I guess you heard the music coming off my headphones, and you heard Diana by One Direction playing. You told me you loved One Direction that your favorite song was–”

“Where do Broken Hearts Go? We bought the Target Vinyl the weekend Made In the AM came out.”

“Exactly. Welcome back.”

“Glad to be back.”

overstimulated English and History majors with a poor grasp of copyright law.

The year before I took over, 1997, was devastating for many of us, when founding editor Zac Lacy died. But working on the paper merged into our grieving process. My impression at this distance is that ultimately the experience was one of great joy, that kind of joy that sparks from the friction of smart people working fast and, frankly, just fucking around. (They really should not have let me play with the photo software.) I hope it remains joyful too in the memories of my very smart, talented collaborators. If those issues are any good at all, it’s in spite of me and due entirely to them; and if there are things in there that are best forgotten, I take the blame — assuming the byline is not already mine. One does not dwell in provocation without making some mistakes. To name one: We did our best not to be insular and aimed to do more than simply entertain ourselves, and maybe we did all right but we might have done better.

I’m looking at those old issues now. Once I set aside the overwhelming embarrassment I feel when I read my youthful, blearily edited prose, the joy is there. I can see it. I hope it’s a foundation that has lasted.

We were a rag. A tabloid. An experiment. We were sanctimonious. We were too serious. We couldn’t take a joke. We made everything a joke, turned everything into a joke; how very dare we make that joke. We cared too much and not enough depending on the critic, the topic, the issue—picked up on our fortnightly rocket into Charlotte, brought back bundled in stacks and shoved under your dorm room door.

I was recruited first semester my first year at Davidson at an event fair on Chamber’s lawn. Vic Brand said, “You should come write for us,” so I did. For three and a half years. We ate and drank weekly at Davino’s until we didn’t, went from old Student Union office to new. Covered our windows with back issues until told we couldn’t. We weren’t so much an event or club or frat or community as an identity. Libertas was what we did. Libertas was a part of who we were, and possibly still are. I was once recognized at an alumni gathering as “that Libertas guy.”

And you could have been a part, too! Something bothering you? Need a platform, a bull horn, a void to scream from? Got a bear to poke or protect? Come on. We’ll print you—just not that title. Seriously, I’ve got a better one. You won’t like it though. I’ll call your abortion piece “They’re Popping Out Like Chickens.” That carefully constructed political analysis you wrote will go to print as “Even Skeletor Hates Arch Conservatives.” So much for the mitigation of bias.

I like to think we didn’t punch down, but there’s no doubt that we tried to punch. We wanted to hit out at every bad thing we thought was bad, every dumb thing we thought was dumb, every cruel hypocrisy we saw lurking in the hall, scribbled on a wall, posted on a flyer, screamed at a passerby. And when we were guilty of hypocrisy ourselves, we called that out in the next issue. We were more than game to publish letters calling us idiots and hypocrites. We were, quite often and unambiguously, assholes.

We sang out the good, too. I am proud of the stances we took, standing up for queer rights, calling out sexual assault, requesting some basic common sense, all in pithy black and white, in agonized-over layouts, messy but sincere, eight to twelve pages every other week. I went digging for my stash of Libertas in my garage and found, among the many I have saved and lugged around over two decades, I only had a single one from my run as senior editor. I was hoping to find the 9/11 issue. I remember thinking it was the best cover I made. I remember thinking what the fuck can we possibly say?

I found instead Vol. 7, No. 4, November 13, 2001: “Constructing Service-able Students: A Look at the Nature of Outreach.” It must be my worst cover. On the back, the first words of my afterglo (the editor’s column at the end of every issue): “Jimmy Carter, when it comes down to it, is my hero… Put in a position to do great things, he did them.” I reread that this morning, twenty-three years to the week it came out, the same morning The Bitter Southerner showed up in my Instagram feed asking, on a sweatshirt for sale, “What Would Jimmy Carter Do?” Some things never change.

Indeed. The looming second Trump administration has me longing for my Libertas compatriots, my college family, my forever friends. The attempted good trouble we would try to cause. The warmth from exhausted hugs. The company of emptied lungs. What I want you to know is this. My indelible memory of Libertas is that it was a labor of love, of late nights and heartbreak, of crazy joy and nonsensical exuberance, not just for us, but for our friends, our school, our country, our world. I guess, after all, we did care too much. Every issue we made on the cheap newsprint we could afford stained our fingers as we read, becoming the fingerprints left behind of those who tried, in the silliest and stupidest and most rushed and chaotic way possible, to make the world better than how it was handed to us. Don’t forget the fucking stars.

ByScottGeigerwithErinSmith,editors-in-chief,2000

After dark at a springtime house party at 541 Concord, Ann Culp took them aside. “I want you to edit Libertas,” she said. They all smoked cigarettes then. “Together.”

Much light and heat still radiated from the magazine’s founding when Erin (Atlanta, Georgia) and Scott (Cleveland, Ohio) came to campus Fall 1997. That fall Mike Scarbo was editor. Zac Lacy was also still around campus, though. He was a presence for that first month, then he was gone. A sense of urgency came out of Zac’s death, a mission channeled differently through the editors, first Mike, then Vic Brand, then Ann herself. Erin and Scott contributed writing and research, they edited sections, they hosted events. Each editor evolved Libertas, they knew, making it their own while also trying to maintain the flame. This is the assignment they accepted, May 1999, smoking cigarettes with Ann.

You should know something good. One evening twenty-five years later — Sunday, January 28, this year — Erin and Scott drove out of the Catskills to Brooklyn in a nighttime snow storm. Their families had met up for a ski weekend. Scott’s returned to Western Massachusetts while he traveled down with Erin’s family to fly to San Antonio from JFK the next morning. Thick wet snow had just begun to freeze over the mountain roads. Erin’s husband and son were immediately asleep in the back. As they set out, one or maybe even both of them together said, “This will be just like Libertas!”

What Erin and Scott were doing at the climax of each issue — to keep that flame lit — was driving by Erin’s Saturn into Charlotte to place a ZIP disk in the hands of the printer. This took place early every other Friday. The files were packaged Quark documents, black and white JPEGs or TIFs linked. What they were doing were all-nighters, of which their drive into Charlotte made the final act. And around these deadlines for this 16-, sometimes 24-page magazine, a whole scene of friends, guest writers, staff grew up, collaborated, argued, fell in and out of fascination and/or love. Libertas worked from a mezzanine office overlooking Concord Road in the Old Union (now Sloan). Staff met Sundays at 9:00 pm at the Outpost for postmortems and editorial meetings.

The magazine’s 2000 volume addressed a campus community that was socially conservative, mostly. Perhaps this was a default setting? Intelligence sizzled everywhere, and work ethic united everyone. So, Erin and Scott sensed room for ideas, especially well-dressed, charismatic ideas. To make accessible and charming Libertas features on marriage, on race relations, on sex, on voting in the 2000 election, and more they overhauled the publication’s graphic identity, dug deep into use of collage, and held up nonfiction in Rolling Stone and the Village Voice as precedent. That fall Erin, Scott, and most of the staff enrolled Alan Michael Parker’s Italo Calvino seminar, and that Italian writer’s prose and politics and sense for technology centered Libertas.

Maybe twice the staff or friends found Libertas issues delivered to certain floors in the dorms shredded and scattered. The office received a few crank voice mails, a few angry emails. But within that expanded universe of friends for the magazine were first-years (shout out to Ian and Grant!) who coded and launched what was in its time a sharp website for Libertas. The British design writer Jonathan Bell found the site, liked our pieces. That winter UK culture magazine Wallpaper*, where Jonathan was books and architecture editor for many years, named Libertas in a global round-up of campus publications. Crushing this triumph and pride over Wallpaper* recognition was Al Gore’s concession.

Erin and Scott arrived in Prospect-Lefferts Garden that night last January without a scratch. Next morning the city started over cold and brilliant.

There’s a plastic tub in my basement full of newsprint that I’ve been lugging around for the past two decades. It’s been on every moving truck and in every apartment and every house since I graduated from Davidson. Inside the tub, alongside a pair of nunchucks (unrelated), is every issue of Libertas I ever worked on, from being a writer, art contributor, and section editor my freshman year to being senior editor in the spring and fall of 2003 — some 40-odd issues full of the strangest, funniest, dumbest, seriousest stuff we felt compelled to print.

Back then, Libertas was a biweekly alternative newspaper, an 8- to 16-page tabloid that served as a bully pulpit for snarky liberals, creative weirdos, and burgeoning writers, and it was my home at Davidson. That paper was my frat, my job, and my family all in one, and looking through those stacks now, the black ink rubbing off on my fingertips, all I remember is what a blast we had putting it together. God, it was fun. So many all-nighters in that office. The art and poetry of today’s Libertas were there, but also student journalism about a whole range of topics: the lack of accountability for sexual assault on campus, racial inequalities in the prison system, jingoism after 9/11, philosophy, religion, that time Kappa Sigs murdered a goose, the advent of Segways (they were supposed to change everything), the narrative potential of video games… you name it.

Going through that tub’s got me talking like an old man now, remembering stories that nobody else cares about, like the time we got called into the dean’s office over complaints about our cussing and put out “The Profanity Issue” two weeks later (it was much more thoughtful than it sounds). Or at the Student Activities Fair, setting out a bowl of loose Camel Lights as our freebies (this was at the tail end of smoking being both cool and affordable, neither of which it still is, thankfully). Or driving blearily down to Charlotte early in the morning to pick up the latest issue from the printer and coming back to slide a copy under every dorm room door. Some folks loved it; some folks hated it; and some folks complained that their copy smelled like cigarettes (my bad — again: don’t smoke, kids).

There was no better feeling than seeing the funny headlines and silly pictures and serious writing we’d laid out on our clunky old computers — in PageMaker, no less! — appear in our hands as a physical object, a newspaper that we could share with our friends and our teachers and anyone who’d pick it up. Twenty years later, I’ve cobbled together a career as an editor, writer, and graphic designer — all skills I first learned in that little Libertas office upstairs in the Union, sneaking vodka, cracking jokes, and stirring the pot with people who are still some of my best friends to this day. I’m proud of the work we did, and I hope students today are finding ways to be publicly angry and silly and thoughtful and assertive about the world in which we find ourselves. George W. Bush was bad enough (the worst, by many metrics, in fact); Lord only knows what kind of trouble we would be getting into if we were up there cranking out issues in the Trump era.

As all things do, Libertas has evolved into something different. I’m just thrilled it still exists. At the end of every article, our style guide called for a single black star — capital H in MonoType Sorts for you font nerds out there — as a way to signal to readers that the article was over (in case our goofy page layouts didn’t make it clear). Our mantra in the office was simple: “Don’t forget the fucking stars.” It was a call to pay attention to the details, to check for column alignment and grammatical errors, to make the best damn paper we possibly could. It was also, I’m realizing, about finality. The issues were coming back one way or the other, with all of our mistakes and all of our triumphs right there in black and white for everyone to see. And then it was time to do another one, and then another one, and then another one, until eventually, it was someone else’s turn. Someone else’s tub to fill.

aka Letter from the Editor to our young readers

Dear Readers,

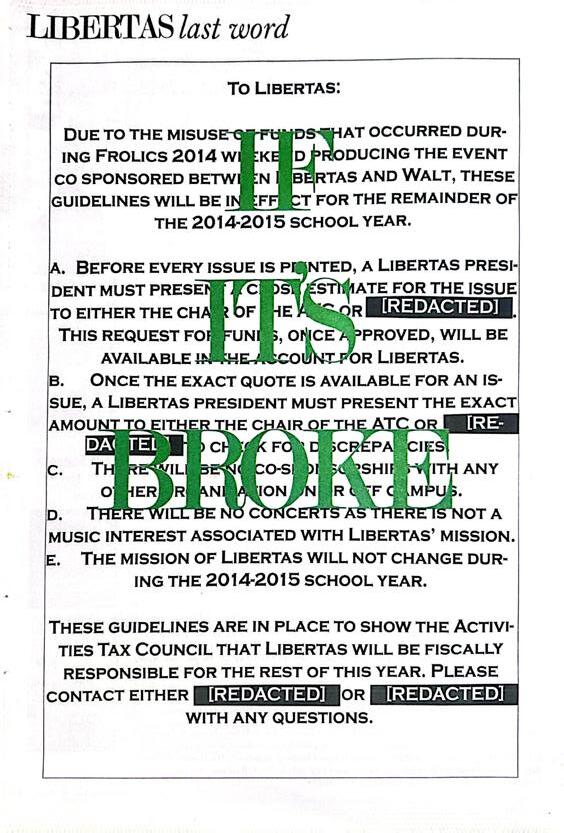

This theme has been my baby since I took over Libertas last spring. Something about the existential dread that clutches seniors as we realize just how short instutional memory actually is. How could I let all my silly fun facts that I’ve acquired through tireless work all four years just go to waste so that children (adults) born in 2006 could forget it all overnight.

So here is a record of how quickly things can change and how everything has a past and how for Davidson clubs most of those pasts involve being founded out of spite (and some passion).

Going back through that archives for this issue I was impressed by the creativity, artistic skill, dirty minds, journalistic integrity, and overwhelming horniness that has been poured onto the Libertas pages for almost three decades.

This will be my last issue in charge, but Libertas has been a green velvet couch that has heard more than its fair share of secrets. It has given me the best friends to sit next to. I’ve also probably lost some eyesight from many hours of editing, but I have gained a new network of artists.

Though Libertas now looks completely different, and who knows what the future holds, I am proud to be leaving Davidson with a bathtub full of Libertas editions.

Stay weird, whimsical, and peeved (just make sure to write it down).

Yours truly,

Audrey Bohlin Editor-in-Chief

Credit to all the past Libertas Contributors whose work from the archives is featured within this issue