Todas las imágenes / All images: ©Boris Lurie Art Foundation

Print run: 600 copies

Este catálogo comenzó con sus primeros bocetos a finales de 2019, y se desarrolló durante 2020, 2021 y 2023. Fue creciendo mientras el mundo atravesaba las etapas de la pandemia Covid-19. Esta extensión en el tiempo dio lugar a que los diversos participantes reflexionaran más profundamente sobre la vida y obra de este singular artista. Una tarea reconfortante y alentadora que se apreciará en las siguientes páginas.

Thiscatalogbeganwithitsfirstdraftinlate2019 andcontinuedtodevelopin2020,2021and2023. Itgrewasthewordwentthrough thestagesoftheCovid-19pandemic. Theprolongeddevelopmentallowed thevariousparticipants toponderdeeplyonthelifeandwork ofthisexceptionalartist. Thiscomfortingandencouraging laborthatwillbeapparentinthefollowingpages.

Dear friends:

We wish to share with you the work of Boris Lurie and explain some of the reasons it is so important. Boris loved so many of the Argentinian painters and writers whose work traveled around the world and influenced the culture of the United States and Europe.

Boris grew up in Latvia and had the translated works emanating from Argentina available to him in the libraries at his German speaking school.

After four years in a concentration camp with his father and the loss of his mother, sister, grand-mother and first love in the Rumbula massacre, he emigrated to the United States with his father. At this time he spoke and read Spanish, having learned the language from another prisoner in the camp. He was then able to read the originals, which he greatly admired. These writers were well represented in the States, as were the Argentinian painters.

Argentina was a haven for many people stranded in Europe during and before the Holocaust.

This exhibition has been handled with great care, and we wish to thank both institutions for their special work in envisioning and organizing what you will be experiencing at the show.

Thanks for your cooperation and I hope that you will enjoy the show.

Gertrude Stein President BorisQueridos amigos:

Deseamos compartir con ustedes la obra de Boris Lurie, y explicar algunas de las razones por lo cual es tan importante. A Boris le encantaban muchos de los pintores y escritores argentinos que tenían obras viajando alrededor del mundo e influenciaban en la cultura de los Estados Unidos y Europa.

Boris se crió en Letonia y en la biblioteca de su escuela de habla alemana tuvo a su alcance aquellas obras traducidas provenientes de Argentina.

Después de cuatro años en los campos de concentración con su padre, y de la pérdida de su madre, hermana, abuela y primer amor en la masacre de Rumbula, emigró a los Estados Unidos con su padre. En ese momento ya hablaba y leía en español, habiendo aprendido la lengua de otro prisionero en el campo. Él estaba entonces capacitado para leer los originales que tanto admiraba. Estos escritores estaban bien representados en los Estados Unidos y allí había exposiciones de pintores argentinos en las galerías de arte.

Argentina era un refugio para mucha gente retenida en Europa antes y durante el Holocausto.

Esta exposición fue preparada con gran cuidado y queremos agradecer a ambas instituciones por su especial trabajo en proyectar y organizar lo que se podrá apreciar en esta presentación.

Gracias por su cooperación y espero disfruten de la exposición.

With great honor, the Jewish Museum of Buenos Aires takes pride in presenting the extraordinary exhibition of Boris Lurie. We extend our profound gratitude to the Boris Lurie Art Foundation for choosing to collaborate with us, along with the Borges Cultural Center, to bring these masterpieces to life and offer a moving testimony about the memory of the Holocaust from the perspective of an artist who, through his work, gives voice to the experience of surviving the unimaginable tragedy that was the systematic and massive extermination of six million of our brethren under the Nazi regime.

In a world that becomes increasingly sophisticated, yet has not progressed towards a humanity capable of responding to the magnitude of the destruction inflicted upon those deemed different, our mission is to remember, to keep alive the awareness that the past cannot be overcome without facing the lessons that prevent its repetition. Each act of extermination among fellow beings invokes the Jewish memory of the Holocaust, becoming a universal echo of all genocides and violent acts, an echo that resonates in the ontological memory of Cain facing the first fratricide, a sorrowful narrative that, with biblical roots, persists in new geographic forms, unacceptable justifications, and reminds us of the shared responsibility to be guardians of our brethren.

The act of eradicating the life of a fellow being, in constant transformation throughout human history, confronts us. Despite having believed that we had learned the lesson after the Second World War, a new tragedy ravages Europe, with Ukraine devastated by the brutal Russian invasion. While in different parts of the world, the same horror expressed in this exhibition repeats itself in various proportions, our commitment urges us not to forget.

In Buenos Aires, a city marked by two terrorist attacks on our streets and amid the impunity generated by the lack of justice, this situation calls us to remember, to honor the historical truth that some try to erase or conceal, and to demand justice. From the unique perspective of the Holocaust tragedy, our "Never Again" resonates as a universal plea in the silence of those who can no longer raise their voices, but whose voices narrate their pain, with the hope that they will not be forgotten and that the hatred that took their lives will finally be eradicated from the face of the Earth.

Con gran honor, el Museo Judío de Buenos Aires se enorgullece en presentar la extraordinaria exposición de Boris Lurie. Extendemos nuestra profunda gratitud a la Fundación Boris Lurie por haber elegido colaborar con nosotros, en conjunto con el Centro Cultural Borges, para dar vida a esta obra maestra y ofrecer un testimonio conmovedor sobre la memoria de la Shoá desde la perspectiva de un artista que, a través de su trabajo, da voz a la experiencia de sobrevivir a la inimaginable tragedia que fue el exterminio sistemático y masivo de seis millones de nuestros hermanos bajo el régimen nazi.

En un mundo que se torna cada vez más sofisticado, pero que aún no ha avanzado hacia una humanidad capaz de responder a la magnitud de la destrucción infligida sobre aquellos considerados diferentes, nuestra misión es la de recordar, para mantener presente que el pasado no puede ser superado sin enfrentar las lecciones que previenen su repetición. Cada acto de exterminio entre semejantes evoca la memoria judía de la Shoá, convirtiéndose en un eco universal de todos los genocidios y actos violentos, un eco que resuena en la memoria ontológica de Caín frente al primer fratricidio, una triste narrativa que, siendo de raíz bíblica, persiste en nuevas formas geográficas, inaceptables justificaciones y nos recuerda la responsabilidad compartida de ser guardianes de nuestros hermanos.

El acto de erradicar la vida de un semejante, en constante transformación en la historia de la humanidad, nos confronta. A pesar de haber creído que habíamos aprendido la lección después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, una nueva tragedia asola Europa, con Ucrania devastada por la brutal invasión rusa. Mientras en distintos lugares del mundo se repite, en diversas proporciones, el mismo horror que esta exposición expresa, nuestro compromiso nos insta a no olvidar.

En Buenos Aires, una ciudad marcada por dos atentados terroristas en nuestras calles y en medio de la impunidad que genera la falta de justicia, esta situación nos convoca a recordar, a honrar la verdad histórica que algunos intentan borrar u ocultar, y a exigir justicia. Desde la perspectiva única de la tragedia de la Shoá, nuestro "Nunca Más" resuena como un clamor universal en el silencio de aquellos que ya no pueden alzar su voz, pero cuyas voces narran su dolor, con la esperanza de que no sean olvidados y que el odio que les arrebató la vida sea finalmente extirpado de la faz de la Tierra.

Seventy-five years have passed since the end of World War II, leaving a tragic record of 50 million casualties, of which 6 million Jews, including 1.5 million innocent children. They were massacred and incinerated in the crematoriums of Auschwitz and other concentration camps, simply because they were Jewish.

We have known about those who were indifferent to these terrible events, but recently there have been intense efforts from Holocaust deniers who try to erase facts, history and monuments which remind us of these atrocities and who persist in encouraging violence.

This is the reason the Jewish Museum of Buenos Aires, part of the Libertad Synagogue, is proud to present this collection of works by the outstanding artist Boris Lurie, who is also a survivor of these camps. We would like to thank the Boris Lurie Art Foundation, especially Ms. Gertrude Stein, President, Mr. Anthony Williams, Chairman of the Board, and Mr. Rafael Vostell, Senior Advisor, for choosing us, together with the Centro Cultural Borges, to host this exhibition in Buenos Aires.

We have learned that one of mankind’s objectives is to love. In these difficult times that we are living in, another objective should be to teach how to banish hate.

As for those who preach hatred, let the Eternal One allow what the Psalm 20, vs.9 proclaims: “They shall bend and be defeated, we instead will stand erect”.

Han pasado 75 años desde el fin de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, que dejó un saldo de 50 millones de víctimas. Entre ellas 6.000.000 de judíos, incluidos 1.500.000 de niños inocentes, masacrados y quemados en los crematorios de Auschwitz y demás campos de concentración, por el solo hecho de ser judíos.

Hasta hace pocos años, sabíamos de los que eran indiferentes a estos hechos, pero en los últimos años han surgido con intensidad los llamados "negacionistas", que desmienten y tratan de borrar hechos, historia y monumentos que hacen a estas infaustas calamidades que azotaron a la humanidad, con el corolario de tanta violencia que todavía nos aqueja.

Por eso, el Museo Judío de Buenos Aires, perteneciente al Templo de Libertad, se honra al presentar esta colección de obras del excepcional artista Boris Lurie, sobreviviente del Holocausto y agradece a la Sra. Gertrude Stein, Presidenta de la Fundación Boris Lurie, al Sr. Anthony Williams, Presidente de la Comisión Directiva de la Fundación Boris Lurie y al Sr. Rafael Vostell, Principal Consejero de dicha Fundación por habernos elegido, junto con el Centro Cultural Borges, para exponer la obra del insigne pintor.

Hemos aprendido que el objetivo del hombre es el amor; en estos días álgidos que estamos pasando, quizás debemos aprender también que otro de los objetivos del hombre es el "educar" para desterrar el odio.

En cuanto a los que propagan el odio, la xenofobia y el racismo, quiera el Eterno que se cumpla lo que dice el Salmo 20, Vers.9:" Ellos se doblan y caen derrotados, nosotros en cambio seguimos erguidos".

El Museo Judío de Buenos Aires le da la bienvenida a la obra de Boris Lurie, un artista que fue testigo y víctima del mayor horror de la historia del pueblo judío. De una brutal honestidad, tomó posición a través de su arte y su compromiso con la verdad.

El primer contacto con la obra de Boris Lurie lo menos que produce es malestar, no ya en el sentido freudiano, sino una reacción que remite a lo escatológico, visceral, ancestral y primitivo. Esta experiencia impulsa a abandonar nuestra zona de confort y adentrarse en las profundidades de un alma dañada por algo que nunca llegaremos a comprender. Esa no comprensión posiblemente sea el punto de contacto con el artista, se siente el latigazo de su experiencia, la cual no podemos nombrar ni explicar. Los campos de concentración, las masacres, la muerte de su madre, abuela, hermana y primer amor marcaron su existencia.

La palabra trauma se presenta con una vehemencia tal que deja perplejo al observador y aun así es difícil dejar de mirar. Freud consideró como trauma a un acontecimiento cuyo caudal pulsional excesivo sobrepasa la capacidad de tramitación del aparato psíquico. La “Serie de la guerra” de los años 1946/1950 revela al artista con vocación de reportero gráfico, descarnado, ya vacío, teñido de horror y tormento. Resalta las figuras fantasmagóricas con tiza y pasteles acentuando el carácter sombrío de las escenas. El trazo desmaterializado y desnudo de algunos dibujos y bosquejos se posiciona en el papel de una manera lateral, dislocada. En estos el enguaje plástico es austero, contenido, pero impacta ciertamente haciendo ecos de la experiencia de la angustia que tan bien describe Heidegger en la noción de Stoss: este'choque' queproduceenelobservadorlaobradearteestárelacionadoíntimamenteconlaexperiencia de angustia. La angustia sobreviene al Da-sein cuando registra la insignificancia del 'mundo' -comoaquelloquenoremiteanada-.

Entrar en el mundo de Boris Lurie podría ser un acto de voyeurismo, sin embargo es un acto de fe. Una promesa de purgatorio, expiación del pecado de ser, de existir, de sobrevivir y continuar la vida en un mundo banal vaciado de sus afectos más tiernos y profundos. El desafío de vivir en la sociedad consumista neoyorquina de la post guerra, donde no había lugar para hablar del Holocausto, fue modelando su personalidad poco afecta a complacer. El espanto había limado sus pulsiones hasta que lo vano se volvió insoportable. Su derrotero es sincrónico con la historia del arte, tributario del expresionismo alemán, sus trabajos de la primera época exultantes de densidad gráfica conforman un estilo acorde a los tiempos de una Europa azotada por desatinos y flagrancias.

Con la serie de Mujeres desmembradas comienzan sus preocupaciones relacionadas al cuerpo femenino. La sensualidad cede su lugar a cuerpos inmóviles, estáticos, distorsionados, en tortuosas poses carentes de naturalidad. Todavía está muy fresco en su memoria el recuerdo de los horrores padecidos en los campos donde se daba la batalla de Eros y Tanatos. La socióloga Dominique Frischer expresa que los sobrevivientes se sumían en un “silencio estructurante” no durante los primeros meses, o siquiera los primeros años. Durante décadas. Porque, dice ella, es el que ha permitido la continuación de la vida. Ese silencio en Boris Lurie, no aplica en el sentido literal, sin embargo es más que evidente que la opción de callar encarnó una

rebelión silenciosa mediante su proceso creativo y la gestación de la alegoría y símbolo del NO Art!. Ese slogan que hace callar enfáticamente descomprime su trauma encapsulado en las profundidades de su ser e invade el territorio pictórico ya emancipado de cualquier intento de representación.

Desmarcándose del arte que promovían los grandes críticos, entre ellos Clement Greenberg muy cercano a Jackson Pollock, Lurie, en 1959 junto a Stanley Fisher y Sam Goodman funda el movimiento NO! art al que se le sumaran, entre otros los artistas Rocco Armento, Isser Aranovici, Enrico Baj, Herb Brown, Allan D´Arcangelo, Erró, Dorothy Guillespie, Esther Morgestern Gilman, Allan Krapow, Yayoi Kusama, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Suzanne Long, Michelle Stuart, Aldo Tambellini y su gran amigo Wolf Vostell. Este movimiento se formó como pièce de ressistance ante la consolidación del Expresionismo Abstracto y el Pop art como el arte dominante en el mercado del arte americano. Su propuesta era eminentemente política y anti estética, el NO aparecía en las obras despuntando una entidad que se desmarcaba de las corrientes en boga. No a la guerra, no a las mujeres objeto, no a la cultura consumista americana, no a las instituciones del mercado del arte. Es un NO performativo, hace lo que dice.

Se ha dicho que la obra de Boris Lurie es pornográfica. En sus investigaciones la psicoanalista Adriana Abeles1 propone que el problema es el dispositivo capitalista “pornografía” que secuestra toda posibilidad liberadora de la profanación, saturando el valor expositivo hasta la banalidad. La pornografía tiene un particular tratamiento de la imagen del cuerpo, incorpora lo real del acto sexual privilegiando la cara femenina. Irrumpe sin velo. Abeles dice que la obra de Boris no es pornográfica, es testimonial. Afirma, que, según Giorgio Agamben hay dos instantes de la desnudez: Adán y Eva estaban desnudos antes y después de pecar. La vida desnuda o “la vida nuda” es la vida en cuanto fenómeno biológico, la vida aislada considerada solamente como un pedazo de materia, un elemento individual de la naturaleza que existe solamente de una manera física. En la modernidad, esa vida es la que forma la “materia prima” de la política, de un cuerpo –“elhomosacer”- que es el objeto originario de la política, y que, mientras se encuentre en ese estado –puede ser tratado de cualquier manera (incluso se le puede dar muerte impunemente). Su planteo nos remite al tratamiento que, los sistemas políticos incluyendo los autoritarismos han hecho del “Hombre sacer”.

Lo obceno no es más que ausencia de gracia: un modo de ser para el otro que pertenece al género de lo no agraciado (disgracieux). Como reportero de guerra, Sam Goodman documenta las escenas de la liberación de los campos de exterminio al final de la guerra. Estas fotografías fueron la materia prima con la cual Boris Lurie dio origen a la serie Saturation paintings. En Railroad Collage (Railroad to America) vemos la imagen escalofriante de miles de cuerpos apilados en un vagón de tren a la cual superpone una chica pinup mostrando su trasero desnudo en actitud desafiante y vergonzosa. El artista se anima a echar mano esas imágenes. No es pornografía, lo “disgracieux” está a la vista.

Boris Lurie apeló a la superposición de pinups (imágenes de mujeres con poca ropa y actitud pícara) produciendo obras que remiten a los moodboards o tableros de las campañas de publicidad durante los años 60, a los armarios metálicos de los soldados americanos enlistados y, en un sentido extendido, a las pizarras con fotos de los desaparecidos buscados por sus familiares al final de la guerra. Este regodeo de imágenes desparramadas en su modesto estudio constituye el repertorio de recursos con los cuales Boris Lurie evoluciona hacia la consolidación de su identidad artística en un ejercicio de exorcismo que le es vital.

Es relevante destacar que en el año 1961, el nazi Adolf Eichmann, que comandó la logística en la Oficina de Asuntos Judíos de la Cancillería del Reich, fue capturado por el Mossad en Buenos Aires, llevado a Jerusalén donde se lo juzgó, se lo declaró culpable de delitos de lesa humanidad y fue condenado a muerte. Hannah Arendt fue corresponsal por la revista The New Yorker, asistió al juicio dando a luz a “La banalidad del mal”, documento de sus impresiones del juicio que despertó feroces críticas dentro de la comunidad judía. En este contexto, la estupenda obra Oh Mama Liberté tiene una trascendencia iniciática. El nombre de Eichmann con la leyenda Stand Up! tiene una presencia inusitada en la composición. La ferocidad con la que acomete el lienzo nos habla de su enojo e impotencia. La Caja de Pandora se había abierto, exponiendo sus heridas, comenzó a perfilarse la apoteosis de su producción. Boris Lurie había encontrado su voz.

En estas latitudes, la Cancillería Argentina llevó a cabo una política restrictiva para el ingreso de refugiados judíos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial a pesar de ser el país con la 2 segunda población más numerosa de judíos en América. Victoria Ocampo, fundadora de la revista Sur, escritora y protectora de la intelectualidad de la época, había partido a Alemania en el año 47, como testigo de los juicios de Nüremberg. Se percibe a sí misma como un testigo anónimo e irrelevante, su condición de única mujer tampoco le facilitó su reconocimiento como periodista y mantuvo sus impresiones en el estricto ámbito familiar. Años más tarde, respecto del caso Eichmann, Ocampo se hizo escuchar: “que Argentina (al parecer tan aferrada a la “legalidad” hoy día) haya servido de refugio a criminales de esta calaña y les siga sirviendo de segunda patria,escosaatrozparaquienesqueremosanuestratierra.”En el año 1985 Jorge Luis Borges asistió al Juicio a las Juntas Militares que gobernaron nuestro país entre 1976 y 1983. En ese período desaparecieron miles de personas. Luego de escuchar los testimonios del testigo Victor Basterra lo único que pudo decir fue: “qué horror!” Nuestro mayor escritor se había quedado sinpalabras.Mástardeyantealgunosperiodistasdijo:“sientoquehesalidodelinfierno.Este hechonopuede,novaaquedarimpune”

El 17 de marzo de 1992, en un ataque terrorista una bomba destruyó la Embajada de Israel y edificios aledaños en Buenos Aires causando 22 muertos y 242 heridos. El 18 de julio de 1994 un auto bomba (se presume) hizo explotar la sede de la AMIA (Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina) dejando un saldo de 85 muertos y al menos 308 heridos.

Hasta el día de hoy no se han encontrado a los culpables.

In Buenos Aires, Argentina, we welcome the work of this artist who was a survivor of the greatest horror of the history of the Jewish people, who took a stance through his art and his commitment to truth.

After first contact with Boris Lurie’s work, the viewer at least feels discomfort, but not in the Freudian sense, but rather, a reaction that refers to the scatological, visceral, ancestral, and primitive sense. This experience forces us to abandon our comfort zone and venture into the depths of a soul damaged by something that we will never manage to understand. That nonunderstanding is possibly the contact point with the artist, feeling the lash of his experience, which we cannot either name or explain. The concentration camps, the massacres, the death of his mother, grandmother, sister and first love, all left their marks on his existence.

The word trauma is presented with such vehemence that it leaves the observer perplexed, but even so, it is difficult to look away. Freud considered as trauma an event whose excessive impulse flow exceeds the processing capacity of the psychic apparatus.

The War Series from the years 1946/1950 shows the artist as graphic reporter, stark, devoid of horror and torment. He highlights the phantasmagorical figures with chalk and pastel colors, emphasizing the shady nature of the scenes. The dematerialized and bare lines of some drawings and sketches are placed on the edges on the paper, dislocated. In these drawings and sketches, the plastic language becomes austere, restrained, but it has a certain impact, echoing the experience of angst that Heidegger so well describes in the notion of Stoss. This ‘impact” that occurs to the observer of the artwork is intimately related to the experience of angst.AngstovercomesDaseinwhenitregisterstheinsignificanceofthe‘world’-assomething that takes us nowhere-.

Entering Boris Lurie’s world could be likened to an act of voyeurism; but, however, it is an act of faith. A promise of purgatory, expiation of the sin of being, of existing, of surviving and continuing to live in a banal world void of its most tender and deepest affections. The challenge of living in the post-war New York society, where talk about the Holocaust was a forbidden topic, gradually molded his personality, never keen on pleasing. Fright had ironed out his drives until the vain became unsupportable. Lurie was route is synchronous with the history of art, a tributary of German expressionism, his first works, exultant with graphic density and shapea style in harmony with the times of a Europe afflicted by blunders and flagrent errors.

With the Dismembered Women series, his concerns about the female body begin. Sensuality gives way to immobile, static, distorted bodies, in tortuous poses lacking naturality. The reminder of the horrors experienced in the camps, where Eros and Thanatos battled it out, are still very fresh in his memory. The sociologist, Dominique Frischer, expresses that the survivors fell into a “structuring silence”, not during the first months, or even the first years. But for decades. Because, she says, this is that has enabled the continuation of life. That silence in Boris Lurie does not apply in the literal sense, but however, it is more than obvious that the option of keeping quiet incarnated a silent rebellion by means of his creative process, and the

gestation of the allegory and symbol of NO!art. That slogan that emphatically imposes silence, decompresses his incapsulated trauma in the depths of his being, and invades the pictorial territory, now emancipated from any attempt at representation.

Distancing himself from the art promoted by the great critics, including Clement Greenberg, who championed Jackson Pollock, together with Stanley Fisher and Sam Goodman, he founded the NO!art movement in 1959. Other artists would later join the movement, such as Rocco Armento, Isser Aranovici, Enrico Baj, Herb Brown, Allan D´Arcangelo, Erró, Dorothy Guillespie, Esther Morgestern Gilman, Allan Krapow, Yayoi Kusama, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Suzanne Long, Michelle Stuart, Aldo Tambellini and his great friend, Wolf Vostell. This movement was established as a pièce de résistance against the consolidation of Abstract Expressionism and Pop-Art, as the dominating art in the American art market. Their proposal was mainly political and anti-aesthetic, the NO appeared in their works, sprouting an entity that stood apart from the mainstream. No to war, no to women as objects, no to the American consumerist culture, no to the art market institutions. It is a performative NO, it does what it says.

It has been said that Boris Lurie’s work is pornographic. In her research studies, Adriana Abeles1 proposes that the problem is the capitalist mechanism “pornography”, which sequesters any liberating possibility from profanation, saturating the expositive value to banality. Pornography treats the image of the body in a singular manner; it incorporates the real side of the sexual act, favoring the female face. It bursts out without a veil. She says that Lurie’s work is not pornographic, it is testimonial. She states that, according to Giorgio Agamben, there are two instants of nudity: Adam and Eve were nude before and after sinning. The bare life or “thenude life”is life insofar as its biological phenomenon is concerned, the isolated life, considered solely as a piece of matter, an individual element of nature that only exists in a physical manner. In modernity, that life is the one that makes up the “raw material” of politics, of a body -“the homo sacer”- which is the original object of politics, and which, whilst it remains in that state - can be treated any way (even killed with impunity). Her proposal refers us to the treatment that the political systems, including the authoritarian ones and even the killing machinery, have made of the homo sacer.

The obcene is no more than the absence of grace: a way of being for the other who belongs to the gender of the unfortunate (disgracieux). As a war correspondent, Sam Goodman had access to the scenes of the liberation of the extermination camps at the end of the war. These photographs inspired the raw material that Boris Lurie used for his Saturation paintings series. In Railroad Collage (Railroad to America) we see the horrific image of thousands of bodies piled up on a train, on which he superimposes a pin-up girl showing her naked bottom in a challenging and shameful attitude. The artist encourages looking at those pictures. It is not pornography, the “disgracieux” is in plain sight.

Boris Lurie resorted to the superimposition of pin-ups, producing works that refer to the moodboards of the advertising campaigns during the 60s, to the lockers of enlisted American

1 Psychoanalyst, founder and president of the Fields of Psychoanalysis Foundation.

soldiers, and in an extended sense, to the blackboards with photos of missing people, sought by their relatives at the end of the war. This dalliance with images scattered about in his modest studio is the repertoire of resources with which Boris Lurie evolves towards the consolidation of his artistic identity in an exercise of exorcism which, for him, is vital.

In 1961, the Nazi, Adolf Eichmann, who commanded the logistics in the Jewish Affairs Offices of the Chancellery of the Reich, was kidnapped by Israeli forces, sent to Jerusalem where he was placed on trial, declared guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death. Hannah Arendt, correspondent for the magazine, The New Yorker, attended the trial, which resulted in the “Banality of Evil”, a document of her impressions of the trial that awoke ferocious criticism among the Jewish community. In this context, the fantastic Oh Mama Liberté has an initiation transcendence. The name of Eichmann with the legend "Stand UP!" has an unusual presence in the composition. The ferocity with which he undertakes the canvas transfers to us his anger and impotence. Pandora’s Box had been opened, exposing his wounds; these were beginning to close, and the apotheosis of his production began to take shape. Boris Lurie had found his voice.

In these latitudes, the art of Boris Lurie relates to our recent history as well— the Argentinean Chancellery carried out a restrictive policy for the entry of Jewish refugees during the Second World War despite being the country with the second largest population of Jews in The Americas. Victoria Ocampo, founder of the magazine Sur, writer and protector of intellectuality of the time, had set off for Germany in 1947, as a witness of the Nuremberg trials. She saw herself as an anonymous and irrelevant witness, her status as the only woman did not help her acknowledgement as a journalist, and she kept her impressions within the strict familiar environment. Years later, with respect to the Eichmann case, Ocampo spoke out: “thatArgentina (seeminglysoentrenchedin“legality”today)hasbeenarefugeforcriminalsofthisnatureand continues to be their second country, is an atrocious thing for those of us who love our land.”

In 1985, Jorge Luis Borges attended the Trial of the Military Junta that governed our country between 1976 and 1983. During this period, thousands of people disappeared. After hearing the testimonies of the witness, Victor Basterra, the only words that came out of his mouth were: “how awful!” Our greatest writer was lost for words. Later and in front of some journalists he said: “IfeelasifIhavecomeoutofhell.Thisactcannot,isnotgoingtobeleftunpunished”.

On 17 March 1992, in a terrorist attack, a bomb destroyed the Israeli Embassy and adjacent buildings in Buenos Aires, causing 22 dead and 242 wounded. On 18 July 1994, a car bomb (presumably) was made to explode at the headquarters of the AMIA (Mutual Israeli Argentinean Association), leaving at least 308 dead.

As at today, the culprits have still not been found.

Encontrarnos con la exposición de Boris Lurie en las salas del Centro Cultural Borges, es antes que nada un enorme placer, ya que esta exposición tiene lugar en un espacio que desde el año pasado reabrió sus puertas bajo la órbita del Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación y por tanto, se trata de una institución cultural que recupera su estado público y gratuito en la que todas y todos podrán visitar la obra de este artista que nos invita a reflexionar sobre la memoria, tema que hace eco profundo en nuestra cultura. La obra de Lurie se presenta en diálogo con otres artistas de la escena artística argentina que tuvieron lugar en esta misma sala, como Renata Schussheim, reporteros y reporteras gráficas de ARGRA, las fotografías de Pablo Piovano, entre muches otres que formaron parte de la programación del Centro Cultural hasta aquí. Esta misma sala, que hoy es escenario de la confirmación de un compromiso asumido por el Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación y nos permite profundizar al menos en tres ejes centrales.

El primero está ligado a la recuperación del Centro Cultural Borges por parte del Estado. Desde marzo de 2022 el Borges reabre sus puertas luego del restablecimiento y puesta en valor de su infraestructura, sus memorias y sus proyectos tanto pasados como a construir. A tal fin, se integraron salas de exposición, auditorios, biblioteca, salas de talleres, de baile, más de 10.000m2 tejidos para dar lugar a la expresión de las más diversas voces artísticas. Tienen lugar en este Centro Cultural desde la música contemporánea, el jazz, el tango, hasta las danzas urbanas en espacios comunes que invitan a la experiencia compartida del cuerpo en el espacio público. También las letras, desde la obra de Jorge Luis Borges hasta la poesía contemporánea en lecturas, colectivas o individuales, silenciosas en nuestra biblioteca pública o amplificadas en auditorios para la presentación de libros que reúnen debates actuales. La danza en el Borges recupera salas y escenarios permitiendo que el tango sea la lengua del encuentro cotidiano, dialogando con otras expresiones que también tienen historia común en nuestro campo cultural. Por características propias del espacio pero principalmente por criterios curatoriales que permiten recuperar esas memorias que acompañan este Centro Cultural, donde tuvo lugar la primera sede del Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes hacia fines del siglo XIX y hasta 1909, junto a talleres de artistas como Ángel Della Valle, Eduardo Sívori, y los murales que pintaran en la cúpula de aquellas Galerías Bon Marché, Antonio Berni, Lino Enea Spilimbergo, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Demetrio Urruchúa y Manuel Colmeiro, que continúan siendo emblemáticos en este mismo edificio. En este sentido son las artes visuales una presencia central de la programación de este Centro Cultural.

En esta oportunidad tenemos el agrado de recibir la obra de Boris Lurie retomando un proyecto que forma parte de la historia del Borges, una gran exposición que recupera diálogos interrumpidos por un hecho que sucedió en todas las puntas del mapa, la reciente pandemia. Recuperar ese diálogo asumido como compromiso desde el Ministerio de Cultura de la Nación nos trae hoy a las salas del Borges una participación internacional diseñada en aquellos años y repensada ahora para situarse en este nuevo contexto de institución cultural pública. De allí surge el segundo eje de reflexión si nos detenemos a pensar en los equipos que permiten

llevar adelante este proyecto, siendo que, desde aquel entonces, la curaduría está pensada y desarrollada por Cecilia González Souville, parte del equipo del Centro Cultural que se incorporó al empleo público a partir de los últimos años y que trabajó arduamente en la readecuación de la exposición de Boris Lurie en las salas renovadas del Centro Cultural Borges. Los equipos de montaje, iluminación, mantenimiento que llevan adelante los trece espacios de exposición desde planta baja hasta el tercer piso, Yaya Firpo, Mariano García, Fabián Crespi, Leandro Rovallo, Clara Quartino, Fernanda Lita, Gabriel Pérez, Javier Dolagaray, Marcelo Ibarra, y el resto de los equipos de programación y producción, bajo la dirección de Ezequiel Grimson hoy reciben la obra de Boris Lurie en un proyecto de cooperación internacional con la Fundación que lleva su nombre.

El tercer lineamiento que resulta fundamental para el abordaje de esta exposición, en este contexto particular de nuestro país, es el de la memoria. Las memorias que habitan el Centro Cultural y se construyen como pilares sobre los que el Borges reabre sus puertas, las memorias de los proyectos artísticos que lo transitaron, las creaciones que lo desearon y lo defendieron, las memorias que sus trabajadores y trabajadoras continúan hoy llevando adelante en su construcción cotidiana. La propia historia de Boris Lurie, víctima del Holocausto y de la pérdida de su familia bajo el régimen nazi, en su subjetividad se transformó en proceso creativo y fue plasmado en estas obras que trabajan sobre hechos de la cultura que forman parte de la historia universal. Dichos trabajos resuenan en momentos particulares por estas tierras, con los atentados a la Embajada de Israel en 1992 y el atentado a la AMIA en 1994.

En un contexto en el que nuestro país cumplirá 40 años de democracia el próximo diciembre, resulta indispensable mantener encendida la memoria por lxs 30.000 compañerxs detenidxs desaparecidxs en la última dictadura cívico militar que sufrió la Argentina. Por Memoria, Verdad y Justicia junto a Abuelas y Madres de Plaza de Mayo, exigimos nunca más.

Profundo agradecimiento a los equipos que sostienen este y todos los proyectos del Centro Cultural Borges así como a Rafael Vostell, en él a la Fundación Boris Lurie, con quien trabajamos conjuntamente para que esta exposición pueda presentarse al público en Buenos Aires.

It is with enormous pleasure we welcome you to the Boris Lurie exhibition at the Borges Cultural Center, this exhibition is being held in a space that just last year reopened under the auspices of the National Ministry of Culture, making it a cultural institution that has renewed its commitment to being free to the public, where everyone will be able to view this artist’s work that invites us to think about memory, a theme with profound echoes in our culture. Lurie’s work is presented in a dialogue with other artists on the Argentine artistic scene who are exhibited in the same hall, such as Renata Schussheim, ARGRA graphic reporters, photographs by Pablo Piovano, and many others who have long been part of the Cultural Center’s programming. In this same hall, which today contains confirmation of a commitment assumed by the National Ministry of Culture, we can focus in depth on at least three significant aspects.

In March 2022, the Borges reopened its doors after the restoration and update of its infrastructure, its collections, and its existing and upcoming projects. To this end, exhibition halls, auditoriums, the library, the workshop and event rooms, more than 10,000 m2 of space, was developed to accommodate the expression of the most diverse artistic voices. This Cultural Center has hosted events ranging from contemporary music, jazz, and tango to urban dances in common spaces inviting audiences to share the experience in the public space. The center promotes literature as well, from the works of Jorge Luis Borges to contemporary poetry in readings, group or individual, silent in our public library or amplified in auditoriums for presenting books involved in current debates. Dance at the Borges has returned allowing the tango to be the language of our daily encounters, dialoguing with other expressions that also have a common history in our cultural field. This can be credited to the characteristics of the space itself, but is primarily due to curating criteria allowing the recovery of memories linked to this Cultural Center, which was the first site of the National Fine Arts Museum from the end of the 19th Century until 1909 and hosted workshops by artists like Ángel Della Valle, Eduardo Sívori, and the murals painted in the domes of the Bon Marché Galleries by Antonio Berni, Lino Enea Spilimbergo, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Demetrio Urruchúa, and Manuel Colmeiro, which are still emblematic in this same building. In this sense, the visual arts are a central presence of this Cultural Center’s programming.

And now we are lucky enough to receive the work of Boris Lurie, resuming a project that forms part of the history of the Borges, a grand exhibition that returns to dialogues interrupted by the recent global pandemic. In resuming that dialogue, the National Ministry of Culture is committed to bringing international participation to the halls of the Borges, designed during those years and now reshaped to fit into this new public cultural insitutional context. This leads us to the second aspect of focus, if we stop to think about the teams that made this project’s progress possible: since that time, curating has been

conceived and executed by Cecilia González Souville, part of the Cultural Center’s team incorporated into public employment in recent years and who worked arduously to resume the Boris Lurie exhibition in the renovated halls of the Borges Cultural Center. The installation, lighting, and maintenance teams who prepared the

three exhibition spaces from the ground floor to the third floor, Yaya Firpo, Mariano García, Fabián Crespi, Leandro Rovallo, Clara Quartino, Fernanda Lita, Gabriel Pérez, Javier Dolagaray, Marcelo Ibarra, and the rest of the programming and production teams, under the direction of Ezequiel Grimson, today are receiving the work of Boris Lurie in a project of international cooperation with the Foundation that bears his name.

The third fundamental aspect of appreciating this exhibition, in our country’s particular context, is that of memory. The memories that inhabit the Cultural Center and stand as the pillars on which the Borges has reopened its doors, the memories of the artistic projects that have passed through it, the creators that desired and defended it, the memories that its workers are still fostering today in its daily construction. The history of Boris Lurie himself, surivior of the Holocaust who lost his family under the Nazi regime, is transformed through the creative process and depicted in these works that focus on cultural facts that are part of universal history. These works have resonated at particular moments in our country, with the attacks on the Israeli Embassy in 1992 and the Argentine Israeli Mutual Association (AIMA) bombing in 1994.

Our country will reach 40 years of democracy next December, therefore it is vital to keep the memory alive of the 30,000 people who were detained and disappeared during the last civic military dictatorship that Argentina endured. Through memory, truth, and justice together with the Plaza de Mayo Mothers and Grandmothers, we say never again.

Our heartfelt thanks to the teams supporting this and all projects of the Borges Cultural Center and also to Rafael Vostell of the Boris Lurie Foundation, who worked with us to make it possible for this exhibition to be presented to the public in Buenos Aires.

Conocer la vida y obra de Boris Lurie es una experiencia reconfortante e inspiradora. Su compromiso con la verdad, sobre todo aquella que nos ha sido vedada, se manifiesta a través de toda su obra y no debe pasarse por alto.

…”He feels that the ivory tower cannot substitute for real involvement in life; art is an instrument of influence and stimulation”….

Gertrude Stein (1963)

[…”Elsientequelatorredemarfilnopuedesustituirelcompromisorealenlavida;elarte esuninstrumentodeinfluenciayestimulación”…]

Boris Lurie fue un artista revolucionario comprometido con la humanidad.

A pesar de haber padecido lo peor que le puede suceder a un ser humano que es vivir el asesinato de sus seres más queridos, la tortura y la esclavitud, salió adelante viviendo con la dolorosa premisa de no olvidar y luchando contra todo aquello que no quería volviese a suceder nunca más

Habiendo sobrevivido a los horrores del Holocausto, vivir en New York representaba una confrontación muy fuerte para el artista. Por eso dedica su arte a la verdad. Verdad del comportamiento humano y sus drásticas consecuencias que conoce a un nivel impensable como testimonio encarnizado de la tragedia más grande de la humanidad. Sus obras no sólo referencian su cautiverio, sino que se extienden y reafirman denunciando las miserias de la posguerra. Todo el dolor que no quiso ocultar y que a su alrededor parecía ocultarse en una sociedad hipócritamente triunfalista.

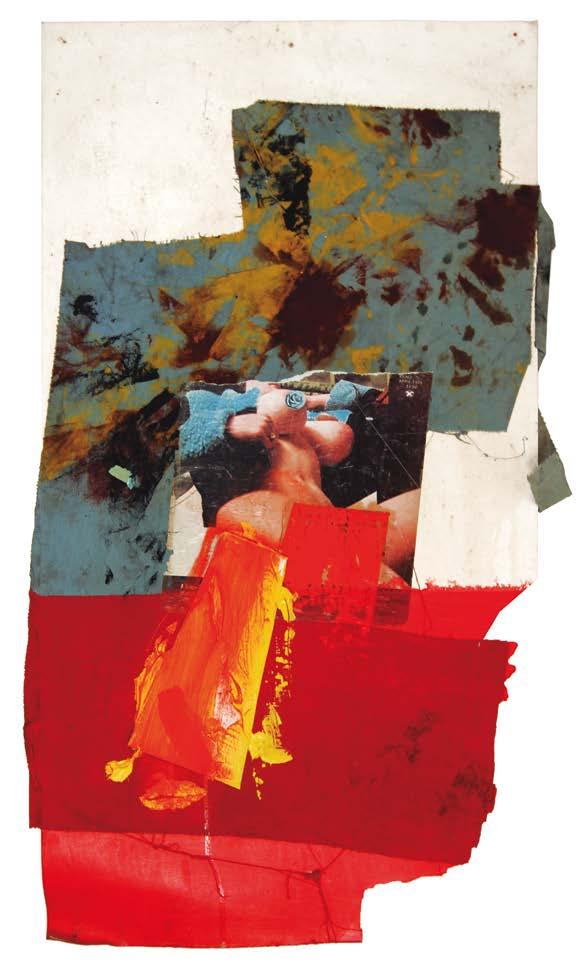

Para romper con aquella fachada, Lurie mostraba la peor cara de la humanidad. De forma transgresora mostraba todo aquello que, cubierto bajo un velo de normalidad consumista, contribuía a la destrucción del individuo. Utilizaba la superposición de imágenes y la fragmentación como una explosión, piezas rotas superpuestas unas sobre otras. Para sus collages recorta publicidades y noticias de diarios y revistas, las piezas de esa aparente “realidad” que parte en mil pedazos para deconstruirla y presentarla desmembrada como realmente estaba.

Entre sus obras se encuentran Mujeres Desmembradas– que remiten a la mujer como víctima del Holocausto -, las Pinups– que remiten a la mujer objeto, víctima del consumo -, por otro lado Hombres Alterados – que remiten al político, al hombre viciado de poder, al hombre alienado por el consumo -, y por último escenas de sadomasoquismo – remitiendo a la dominación y al tabú de la sociedad -, y muchos NO.

El NO de Lurie, es un NO a la negación, un NO positivo para la construcción de un mundo mejor a través de la verdad. Un NO con mayúsculas, como un grito que dice: Despierten!

Su obra era fuerte, contemporánea y confrontativa. Como Lurie, mostraba duras e indeseables realidades y no formaba parte de las corrientes artísticas de su época como el Pop Art y el expresionismo abstracto, no tuvo el reconocimiento por parte de los críticos de arte que solo promocionaban a los artistas cuyas obras eran políticamente “correctas”. Además, como sobreviviente representaba lo que no querían ver. Y él mismo se manifestaba como firme opositor, declarándose Anti-Pop.

Boris Lurie creía en la libre expresión, y el arte al servicio de la verdad, no para la venta, no al arte al servicio del poder, no al arte oprimido por el esteticismo.

Por ello funda el Movimiento NO!art, junto a los artistas Sam Goodman y Stanley Fisher en el año 1959. Al que se suman, compartiendo los mismos ideales, importantes artistas como Rocco Armento, Isser Aronovici, Enrico Baj, Herb Brown, Allan D'Arcangelo, Erró, Dorothy Gillespie, Esther Gilman, Allan Kaprow, Yayoi Kusama, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Suzanne Long, Michelle Stuart, Aldo Tambellini y Wolf Vostell.

Este colectivo artístico no solo recuperaba en las obras los hechos de la vida real sino que denunciaba y decía NO a las injusticias y los males de la sociedad, oponiéndose al consumismo, capitalismo, políticas colonialistas, armamentismo, guerras.

Lurie y los artistas del NO!art también se manifestaban en contra de esta elite del arte en la que se beneficiaban mutuamente siempre a los mismos miembros de un círculo cerrado estableciendo las pautas de un “único” y “buen” arte. Testimonio de este pensamiento es el escrito de Lurie “MOMA as a Manipulator” (MOMA como un Manipulador)

Las declaraciones de los estamentos del colectivo artístico ya se manifestaban y revolucionaban desde sus títulos: TheVulgarShow (1960), Doom Show (1961), NO! Show (1963), NOSculptures (1964).

…We are not playful! We want to build art and not destroy it. But we say exactly what we mean–attheexpenseofgoodsmanners.Youwillfindnosecretlanguagehere,nofancy escapes, no hushed, muted silences, no messages beamed at exclusives audiences. Art is a tool of influence and urging. We want to talk, to shout, so everybody can understand. Ouronlymasteristruth…

[Noestamosjugando!Queremosconstruirarteynodestruirlo.Perodecimosexactamente loquequeremosdecir–aexpensasdelosbuenosmodales.Aquínoencontraránlenguajes secretos, ni escapes imaginarios, no hay silencios, acallados silencios, ni mensajes dirigidos a exclusivas audiencias. El arte es una herramienta de influencia e impulso. Queremoshablar,gritar,paraquetodoelmundopuedaentender.Nuestroúnicomaestro es la verdad.]

Gracias a la colaboración de la mecenas Gertrude Stein quien desde un principio supo ver el valor de sus expresiones, comenzaron las exposiciones de arte más vanguardistas.

En el año 1963, en una exposición compartida con el grupo del NO!art en la Galería Gertrude Stein de New York, Lurie presenta una obra que causa gran impacto en el público y en la crítica. En un collage superpone una fotografía de los cuerpos sin vida del campo de concentración (fotografiados por Walter Chichersky) con la imagen de una revista de una mujer desnuda (Pinup: desnudo erótico para el consumo de las masas): el mensaje de Boris se vuelve muy contundente.

Lurie nunca dejó de involucrarse a través de sus obras y en sus escritos, y ese era su mayor valor.

A Boris Lurie lo ocultó la historia, y ese ocultamiento es parte de la historia de nuestra humanidad. Ha llegado el momento de difundir este gran legado en favor de la verdad, que será siempre actual porque es relativo al comportamiento humano.

No podemos olvidar que nuestro país vivió el Proceso de la Dictadura Militar con miles de desaparecidos, que hemos sufrido dos grandes atentados a la Embajada de Israel y a la AMIA, que la mujer ha sido y sigue siendo maltratada, que hay racismo y sexismo. En la medida que cada uno no exprese su pensar y mire para otro lado, la verdad puede ser fácilmente manipulada. No seamos indiferentes.

Knowing the life and work of Boris Lurie is a very comforting and inspiring experience. His commitment to the truth, especially to that truth which has been hidden from us, is manifested through all his work, and should not be overlooked.

…He feels that the ivory tower cannot substitute for real involvement in life; art is an instrument of influence and stimulation…

Gertrude Stein (1963)Boris Lurie was a revolutionary artist committed to humanity. He materialized this commitment through his art, leaving an important legacy with his artworks. Lurie suffered the worst that can occur to a human being, which is experiencing the murder of the one’s dearest to you, followed by torture and slavery. He pulled through, living with the painful premise of not forgetting and fighting against everything that he wanted never to happen again.

Having survived the horrors of the Holocaust, living in New York represented a very intense confrontation for the artist. This is reflected in all his work, and that is why he devoted his art to truth: the truth of human behavior and its drastic consequences, which he experienced at an inconceivable level, as a bitter testimony of the greatest tragedy of humanity. His works not only refer to his captivity, but they also go further and reaffirm his beliefs, denouncing the miseries of the post-war era. All the pain that he did not want to hide but seemed to be hidden around him, in the triumphalism of a hypocritical society. To break down those walls, Lurie showed humanity at its worst. He was defiant in the manner he displayed all of that contributed to the destruction of the individual and that was shrouded by consumerist normality. He used the superimposition of images, and their fragmentation as an explosion, broken pieces superimposed on each other. For his collages, he cut out advertisements and articles from newspapers and magazines; the parts of that apparent "reality", which he tore up into a thousand pieces to deconstruct it, presenting it as it truly was, dismembered, just like his spirit, which could not be shown whole, because it was not whole.

Among his works, we can find Dismembered Women, referring to women as victims of the Holocaust; Pinups, referring to objectified women, victims of consumerism; and on the other hand, Altered Men, referring to corrupt politicians, men with power, men engaged by consumerism; sadomasochism, referring to domination and to taboo; and many NOs.

Lurie's "NO" is a NO to denial, a positive NO for the construction of a better world through truth. A NO in capital letters, like a shout telling us: Wake-Up!

His work was powerful, contemporary, and confrontational. Like Lurie, it showed harsh and undesirable realities. It did not form part of the artistic trends of his time, such as Pop Art, or abstract expressionism. He was not recognized by art critics, who only promoted artists whose works were "politically correct". And as a survivor, he represented what they did not want to see, declaring himself to be a firm opponent, and Anti-Pop Art.

Boris Lurie believed in free expression, and art at the service of truth, not for sale; not art at the service of power, not art oppressed by aestheticism. That is why he with Sam Goodman and Stanley Fisher founded the NO!art movement in 1959. In which he was joined by important artists who shared his same ideals, such as Rocco Armento, Isser Aronovici, Enrico Baj, Herb Brown, Allan D'Arcangelo, Erró, Dorothy Gillespie, Esther Gilman, Allan Kaprow, Yayoi Kusama, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Suzanne Long, Michelle Stuart, Aldo Tambellini and Wolf Vostell. This artistic group not only depicted real life events in their works, but they also denounced and said NO to the injustices and evils of society, opposing consumerism, capitalism, colonialist policies, arms build-up, and wars. Lurie and the NO!art artists also declared they were against the art world elite that created guidelines of what was "unique" and "good" art and the artists it favored. Testimony of this thought is Lurie's writing "MOMA as a Manipulator". The statements of the artistic collective were already manifested and revolutionized since their titles: TheVulgar Show (1960), The Doom Show (1961), The NO! Show (1963), The SHIT show (1964)

… We are not playful! We want to build art and not destroy it. But we say exactly what we mean–attheexpenseofgoodsmanners.Youwillfindnosecretlanguagehere,nofancy escapes, no hushed, muted silences, no messages beamed at exclusives audiences. Art is a tool of influence and urging. We want to talk, to shout, so everybody can understand. Ouronlymasteristruth…

Boris LurieThanks to the collaboration of their patron, Gertrude Stein, who acknowledged the value of their expressions right from the start, the most avant-garde art exhibitions started to be put on. In 1963, during a joint exhibition with the NO!art group in the Gallery: Gertrude Stein in New York, Lurie presented an artwork that caused great impact on the public and critics alike. In a collage he superimposed a photograph of the lifeless bodies in the concentration camp (photographed by Walter Chichersky, a member of the Signal Corps) with the image of a nude woman (pinup: erotic nude for mass consumption): Boris's message becomes very categorical.

Lurie never stopped getting involved through his works and his writings, and that was his greatest value. History concealed Boris Lurie, and that concealment is part of the history of our humanity. The time has come to disseminate this great legacy in favor of truth, which will always be topical because it concerns human behavior.

We cannot forget that our country experienced the Process of Military Dictatorship with thousands of people missing, that we have suffered two devastating attacks on the Israeli Embassy and the AMIA; that women have been, and still are, abused; that there is racism and sexism. As long as each person does not express their thoughts and turns a blind eye, the truth can be easily manipulated. Let's not be indifferent.

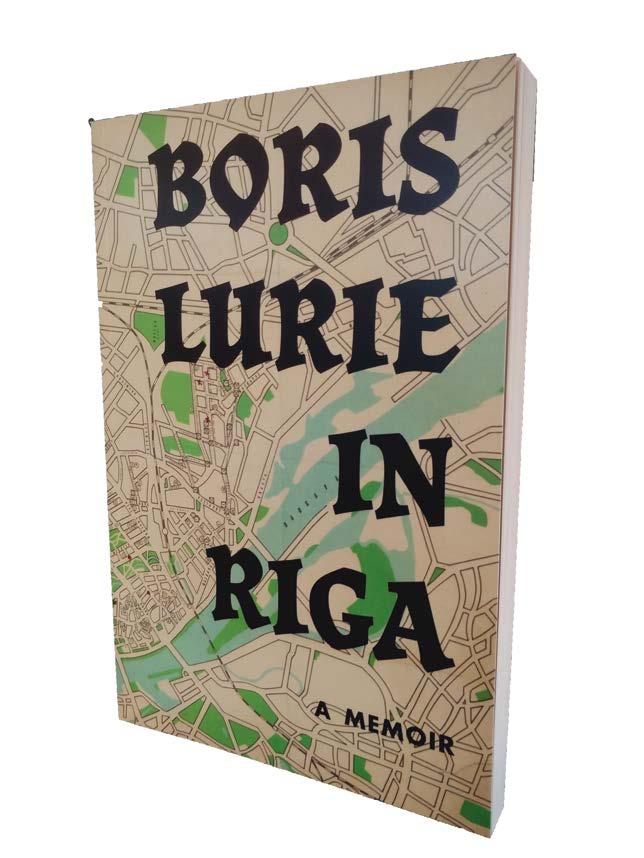

En Arte aprendemos que pintores podemos ser todos, artistas algunos y creadores muy pocos... Boris Lurie (1924-2008) artista y escritor, fue un verdadero creador. Jamás pudo recuperarse de las atroces experiencias vividas. Nacido en Leningrado y encarcelado entre 1941 y 1945 en el Ghetto de Riga, el Arbeitslager de Lenta y los campos de concentración de Salaspils, Stutthof y Buchenwald. Separado de las mujeres de su familia, los nazis asesinaban a su madre, su abuela, su hermana y a su primer amor; así volcó el horror indeleble que nunca pudo borrar de su corazón en el curso natural de su obra.

Su historia de vida fue un viaje a través del dolor, pero al mismo tiempo sembró una semilla que esparció un nuevo humanismo. En las principales ciudades del mundo se crean museos de arte Contemporáneo que coexisten con museos del Holocausto, así es cómo, una de las tragedias más grandes del mundo moderno convive con la exaltación de la creación artística. Los hechos más tremendos de eliminación de la vida humana y el tránsito por esa experiencia aterradora como sobreviviente del Holocausto, impulsaron a Boris Lurie al desafío de la experiencia pictórica determinando un propio y personal lenguaje plástico. Quizás el concepto que pregonaban los surrealistas, sobre “lo que está afuera no está adentro”, le permitió a Lurie encontrar su camino y entregarse a una intuición creativa que promovió el desarrollo de una nueva tendencia en el arte contemporáneo.

Al final de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, después de haber estado cuatro años en campos de concentración, Lurie emigra a los Estados Unidos. Mientras tanto en Europa, tras la capitulación alemana, se inició un proceso de “desnazificación” de la sociedad generando programas de reeducación de la población a través de exhibiciones de documentales sobre los campos de exterminio y otras degradaciones sufridas por los ciudadanos judíos, que daban cuenta de lo vivido. Muchos intelectuales apoyaron esta política a través de su arte, como el poeta y ensayista Werner Bergengruen, que publicó "La última epifanía" en 1946:

“Toquédenochealapuerta,comounpálidohebreo Fugitivo,acosado,conloszapatosrotos. Llamaronalosespías,meentregaronalosverdugos YcreyeronserviraDios”.

En ese mismo año Bertold Brecht escribió:

“Mientras los asesinos estén entre nosotros seguiremosviviendotiempossombríos, enlosqueunaconversaciónsobreárboles escasiuncrimenporqueimplicacallarciertoshorrores”.

En ese mismo año Bertold Brecht escribió: “Mientras los asesinos estén entre nosotros seguiremos viviendo tiempos sombríos, en los que una conversación sobre árboles es casi un crimen porque implica callar ciertos horrores”. A partir de 1948 esta actitud se fue modificando, ante el bloqueo de Berlín Occidental por parte de la Unión Soviética; comenzó así lo que muchos historiadores denominaron Guerra Fría. Los aliados comenzaron a ver a Alemania Occidental, como un partidario potencial en la confrontación con el Bloque Soviético. Los programas de reeducación frente al pasado fueron cambiados por todo lo que apoyara la reconstrucción del país destruido. Ya no era conveniente confrontar “excesivamente” a los alemanes con su culpa. Ante esa nueva realidad reaccionó Theodor Adorno: “Escribir poesía después de Auschwitz es un acto de barbarie”.

En 1946 Lurie, recién llegado a Nueva York, comenzó a realizar pinturas figurativas basadas en su experiencia en los Lager, (Campos de Concentración). Una actitud poco frecuente entre los rescatados del infierno Nazi, ya que la reacción natural mayoritaria fue guardar el horror en el rincón menos frecuentado de la memoria, allí donde se ocultan las cosas que nos espanta recordar.

Las pinturas de 1946 PrisonersReturningfromWork (Prisioneros regresando de trabajar), Roll CallinConcentrationCamp (Toma de lista en el campo de concentración), y Russian Prisoners Being Punished in Stutthof (Prisioneros siendo castigados en Stutthof) exponen las rutinas del horror cotidiano, cuya pavorosa naturaleza estaba planeada para aplastar hasta el menor vestigio de dignidad humana.

Influenciado hacia el final de los años cincuenta por Picasso, De Kooning y más tarde por las obras de Pollock y el expresionismo abstracto, Lurie abandonó la pintura figurativa para desarrollar nuevas direcciones a las que llamó Feel Paintings (pinturas de sentimientos). Eran demostrativas de la fascinación que le inspiraban las bailarinas del teatro de variedades y las “pinup”, chicas sensuales, alegres y desenfadadas que entre los años ’20 y ’50 del siglo pasado poblaban las populares ilustraciones que llegaron a ser un símbolo de la cultura estadounidense.

Lurie procuró siempre la defensa de los sentimientos, el resguardo de una memoria dolorosa, la unión entre la emoción y la acción. Subconscientemente creó una nueva generación de obras buscando promover que el Homo Sapiens, vuelva a encontrar la esencia de su humanidad. Al mismo tiempo que la mano y el ojo de Lurie se alineaban con su sentimiento. Similares emociones inspiraron a Jorge Luis Borges a escribir el poema “Ajedrez” en 1960, poniendo palabras a la fatalidad de la vida, a la muerte, a la guerra, a la libertad, describe un momento entre la noche y el día que transcurre sobre un tablero:

“Nosabenquelamanoseñalada deljugadorgobiernasudestino, nosabenqueunrigoradamantino sujetasualbedríoysujornada”.

(…)

“Diosmuevealjugador,yéste,lapieza. ¿QuéDiosdetrásdeDioslatramaempieza depolvoytiempoysueñoyagonía?”.

En 1959 Boris Lurie, Stanley Fisher y Sam Goodman fundaron en la March Gallery de Nueva York el movimiento NO!art, en rechazo al contenido para ellos deleznable o trivial del pop art y el expresionismo abstracto. En una de sus últimas conversaciones con la prensa, ya octogenario, Lurie explicó que el accionar de NO!art, comenzó por desesperación frente a lo que estaba sucediendo en el mundo del arte: “nuestro impulso ideológico y estético básico era la autoexpresión total y la inclusión en nuestra obra de cualquier tipo de actividad social o política que hubiera en el mundo, recurriendo a cualquier cosa que pudiera considerarse una expresión radical, que no coincidía necesariamente con la expresión permitida bajo las corrientes estéticas del momento. Nuestra estética era reaccionar fuertemente contra cualquier cosa que nos molestara”.

Inseparable de su experiencia en los Lager, la búsqueda artística de Boris Lurie ya había adquirido un perfil definido en la litografía de 1962 titulada Flatcar Assemblage 1945 by Adolf Hitler (Carro plano ensamblado por Adolf Hitler, 1945), que mostraba una pila de cadáveres amontonados. A través de un montaje fotográfico creó en 1963 Railroad Collage (Railroad to America),donde superpuso a la pila de cadáveres la fotografía recortada de una atractiva mujer mostrando sus glúteos. Abierto a múltiples interpretaciones, el fuerte choque de dos mundos extremos, vida y muerte, erotismo y aniquilación, Eros y Tánatos, logró que Railroad Collage

(Railroad to America) provocara una ola de indignadas protestas, demostrativas de que el propósito de NO!art estaba cumplido. En un momento dominado por la trivial celebración de la sociedad de consumo encarnada en el Pop Art, reintrodujo en el mundo del arte la bandera de los sentimientos, pasiones y delirios esenciales de la condición humana, para recordarnos que la felicidad es un bien incierto, pero la tragedia es inseparable de nuestra vida. El Holocausto, un infierno que Boris Lurie y los sobrevivientes de los Lager nunca pudieron desterrar de su memoria, fue lo más atroz, lo que empujó al siglo XX hacia el abismo más horrendo de la historia.

El arte que surgía de la mano de Lurie pasó a ser un territorio de ataque, una trompada al mentón de una estética que exaltaba lo que el sistema ofrecía para su consumo. “Comprar es mucho más americano que pensar”, repetía una y otra vez Andy Warhol, celebrando con sus latas de sopa. Por ese entonces, Lurie trabajaba intensamente en sus obras comprendiendo que la carrera hacia la promoción del nombre y no al desarrollo de la obra desviaba el sentido del arte.

En la serie Altered Man realizada en 1963, Lurie aniquila con el arma del arte a un ser despreciable. Lo priva de su rostro dejándolo fuera de la historia. Se puede rastrear en las pinceladas de Lurie el gesto, el trazo de impotencia ante estos seres de apariencias normales que, con la complicidad fría de su rutina cotidiana, llevaron a la muerte a cientos de miles de personas. Estas mismas características fueron descriptas por Hannah Arendt en Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, escrito después de haber presenciado el juicio a Adolf Eichmann.

Lurie incomodaba con sus pinturas que albergaban una memoria dolorosa. Intuitivamente, creó una nueva generación de obras buscando rescatar para la memoria el oprobio del nazismo. Al mismo tiempo resignificaba el controvertido mundo del arte, rechazando un mercado superficial, pero a favor de un coleccionismo que pudiera comprender la necesidad de unir el arte con “los temas de la vida real”, su preocupación por el colonialismo, el racismo, el consumismo.

NO!art es un fuerte cuestionamiento al mercado del arte y rechazo del arte como inversión. NO!art es anti-mercado del arte mundial.

Lurie definía al arte contemporáneo como “un revoltijo de varios ítems, todos prácticamente bajo la conducción del peor mercado del arte de todos los tiempos. (...) Antes, los artistas no tenían grandes ambiciones financieras, se conformaban con muy poco, querían madurar lentamente. Ahora los precios altos y ridículos, basados en modas emocionales e inversión/ especulación, pretenden enloquecer a los artistas jóvenes”.

Dolorosamente lúcida y aparentemente impiadosa, la mirada de Boris Lurie no nos ahorra ninguno de los males que aquejan a la sociedad contemporánea: episodios de represión, devastación, invasión, colonialismo, totalitarismo, racismo y sexismo se complementan con las espantosas escenas del Holocausto para sacudir la conciencia del espectador y plantear un angustioso interrogante sobre el destino de la humanidad.

Al igual que Viktor Frankl, Lurie encontró sentido al sufrimiento que a través de su arte pudo sublimar. Con la idea de un arte social para todos, Lurie creó la Fundación que lleva su nombre, dedicada a difundir la visceral y esclarecedora saga de NO!art. Hoy día permite que toda la fuerza de su concepción se divulgue en todo el mundo como un mensaje de rebeldía inconformista y creadora.

In Art, we learn that all of us can be painters, some of us artists, but very few creators Lurie (1924-2008), artist and writer, was a true creator. He never truly recovered from the atrocious events he experienced. Born in Leningrad, he was imprisoned between 1941 and 1945 in the Riga Ghetto, the Lenta Arbeitslager, and then the concentration camps of Salaspils, Stutthof and Buchenwald. Separated from the women in his family, the Nazis murdered his mother, grandmother, sister and his first love; he poured this indelible horror that he could never erase from his heart into the natural course of his work.

His life history was a journey through pain, but at the same time it sowed the seed that spread a new humanism. Contemporary art museums occupy the major cities of the world, coexisting with Holocaust museums. Thus, the remembrance of one of the greatest tragedies of the modern world co-exists with the exaltation of artistic creation. The most horrific events related to the elimination of human life, and the transit through those terrifying experiences as a survivor of the Holocaust, drove Lurie to challenge the pictorial experience, determining his own personal plastic language. Perhaps the concept touted by the surrealists, about “what is outside is not inside”, allowed Lurie to find his way and to surrender to a creative intuition that fostered the development of a new tendency in contemporary art.

At the end of World War II, after having spent four years in concentration camps, Lurie emigrated to the United States. Following the surrender of Nazi Germany, a “denazification” process of society began, generating programs to re-educate the public through exhibitions of documentaries on extermination camps and other degradations suffered by Jewish citizens. Many intellectuals reflected on this policy through their art, such as, the poet and essayist, Werner Bergengruen, who published “The last epiphany” in 1946:

“AtnightIknockedonyourdoor,awhite-faced Jew,arefugee,hunteddown,intornshoes. Youcalledtheauthorities,tippedofthespies,and thoughtwelldone,allintheserviceofGod”.

In that same year, Bertolt Brecht wrote:

“Whatkindoftimesarethese,when, A conversation about trees is almost a crime Becauseitimpliessilenceaboutsomanyatrocities!”

In 1948, this attitude started to change, faced with the blockade of Western Berlin by the Soviet Union; which began what many historians would call the Cold War. The Allies started to view Western Germany as a potential ally in their confrontation with the Soviet Block. Re-education programs regarding the past were exchanged for anything that supported the reconstruction of the destroyed country. It was no longer advisable to “excessively” confront the Germans with their guilt. Theodor Adorno reacted to this new reality: “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”.

In 1946, Lurie newly arrived in New York, began to carry out figurative paintings based on his experience in the Lager (Concentration Camps). This attitude was not frequent among those rescued from the Nazi hell, as the natural reaction of the majority was to store the horror in the least-visited corner of their memory, where things that we are frightened of remembering are hidden.

The 1946 paintings, Prisoners Returning from Work, Roll Call in Concentration Camp, and Russian Prisoners Being Punished in Stutthof, show the routines of the daily horror, whose dreadful nature was to crush what remained of human dignity.

Influenced towards the end of the fifties by Picasso, De Kooning, and later by the works of Pollock and abstract expressionism, Lurie abandoned figurative painting to develop a new direction, which he called Feel Paintings. They were demonstrative of his fascination for variety show dancers and pin-ups, sensual, happy, and light-hearted girls who, between the 20s and the 50s of the last century, populated the illustrations that became symbolic of American culture.

Lurie always sought the defense of feelings, the preservation of a painful memory, the union between emotion and action. Subconsciously, he created a new genre of artworks, seeking to foster a return of the Homo Sapiens to the essence of humankind. Whilst Lurie’ hand and eye were aligning with his feelings, similar emotions inspired Jorge Luis Borges to write the poem “Ajedrez” [Chess] in 1960, putting into words the fatality of life, death, war, and freedom. He describes a moment between night and day that occurs on a chess board:

"Theydonotknowthatthe Appointedhandoftheplayer governstheirfate, Theydonotknowthatan adamantinerigor. Subjectstheirwillandtheir journey.(…) Godmovestheplayerandtheplayermovesthepiece.

WhichgodbehindGodbegantheweaving of dust and time and dream and the throes of death?

In 1959 Lurie, Stanley Fisher and Sam Goodman founded the NO!art movement at the March Gallery in New York, rejecting the content of pop art and abstract expressionism, despicable or trivial in their eyes. In one of his last conversations with the media, Lurie, then in his eighties, explained that the activity of NO!art arose out of desperation for what was happening in the world of art: “our basic ideological and aesthetic thrust was total self-expression, and inclusion in our work of any kind of social or political activity that was in the world, that took place in the world, resorting to anything that might be considered a radical expression, that doesn’t necessarily coincide with the expression that was permitted under the then current aesthetics. Our aesthetics was to strongly react against anything that’s bugging you.”

Inseparable from his experience in the Lager, Lurie’s artistic search had already acquired a profile, defined in the c. 1962 lithograph, entitled FlatcarAssemblage1945byAdolfHitler, which shows a pile of stacked corpses. He created Railroad Collage (Railroad to America) in around 1963, superimposing a cropped photograph of an attractive woman showing her buttocks on a pile of corpses. Open to many different interpretations, the strong impact of two extreme worlds, life and death, eroticism and annihilation, Eros and Thanatos, led Railroad Collage to cause a wave of indignant protests, showing that the purpose of NO!art was satisfied. At a time dominated by the trivial celebration of consumer society incarnated in Pop Art, he reintroduced the banner of feelings, passions and deliriums, all of them essential human conditions, into the world of art, to remind us that happiness is an uncertain asset, but that tragedy is inseparable from our lives. The Holocaust, a hell that Lurie and the survivors of the Lager could never banish from their memories, was the most atrocious of these tragedies, driving the 20th century towards the most horrendous abyss in history.

The art that emerged from Lurie’s hand became a territory of attack, a punch to the chin of an aesthetic that exalted what the system offered for consumption. “Buying is much more American than thinking”, repeated Andy Warhol over and over again, celebrating with his soup cans. By that time, Lurie was working intensely on his works, understanding that the race towards the promotion of the name and not to the development of the artwork deviated from the meaning of art.

In the Altered Man series carried out in 1963, Lurie annihilated a despicable human being by using art as a weapon. He deprived him of a face, leaving it out of the story. One can trace in Lurie’ brushstrokes his feeling of helplessness before those human beings of normal appearance, who, with daily routines, led hundreds of people to their death with their cold complicity. These same characteristics were described by Hannah Arendt in Eichmann in Jerusalem:AReporton theBanalityofEvil, written after witnessing Adolf Eichmann’s trial.

Lurie inconvenienced with his painful memory paintings. He intuitively created a new genre of artworks, one that seeks to rescue the opprobrium of Nazism. At the same time, he challenged the conventions of the art world, creating his own that rejected a superficial market, but understood the needs to combine art with the “topics of real life.” Art that concerns itself with colonialism, racism, and consumerism.

NO!art is strong questioning of the Art Market and rejection of Art as an investment. NO!art is anti world art market.

Lurie defined contemporary art as “a mishmash of various items, all practically under the guidance of the all-time-worst art market. (…) Earlier, the artists did not have great financial ambitions, were content with very little, wanted to mature slowly. Now, the ridiculous auctionprices, based on emotional fashions and investment/speculation, attempt to drive the young artists out of their wits.”

Painfully lucid and apparently impious, Lurie’s art may not save us from any of the evils that affect contemporary society: episodes of repression, devastation, invasion, colonialism, totalitarianism, racism and sexism, but these evils are combined with the frightening scenes of the Holocaust, to wake up the viewer’s consciences and pose a distressing question about the fate of humankind.

Like Viktor Frankl, Lurie found meaning in suffering, which through his art, he could sublimate. With the idea of a social art for all, Lurie created the Foundation that bears his name, dedicated to disseminating the visceral message of non-conformism and the creative rebelliousness of NO!art.

Los inicios de la vida judía en la Argentina no tienen una fecha precisa. De acuerdo con la memoria oficial, elaborada por las instituciones centrales de la comunidad, el punto de partida es rural. A fines de 1889, más de ochocientos inmigrantes aldeanos, llegados de la opresiva Rusia zarista, se establecen en campos de la provincia de Santa Fe para trabajar la tierra. El deseo de transformarse en agricultores tenía una dimensión redentora, y se alineaba con las políticas de productivización de las masas judías del este europeo, compartidas por miles de personas. El nombre que eligen para la colonia agrícola es sintomático: Moisés Ville, un homenaje al máximo redentor del pueblo judío. Sin embargo, esa narrativa ha sido discutida por historiadores que detectaron arribos más tempranos, ocurridos desde mediados del siglo XIX, a partir de que la Constitución de 1853 habilitó la libertad de culto. Producto de ese flujo, a comienzos de la década de 1860, un pequeño grupo de inmigrantes centro europeos creó la primera sinagoga de la historia nacional, germen de la Congregación Israelita de la República Argentina, cuya sede actual es el Templo de la calle Libertad 769, contiguo al edificio del Museo Judío de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Esta segunda versión recupera aristas previas a la llegada de los colonos agrícolas, como por ejemplo la voluntad explícita del gobierno argentino de atraer "israelitas" al país: en 1881, al enterarse de los pogromos en la Rusia zarista, el presidente Julio A. Roca firmó una invitación por decreto. También designó a un agente oficial en Europa y lo proveyó de recursos.

Aun así, existen dos versiones más. Distintos emprendedores culturales aseguran que el punto de partida debe ubicarse mucho antes del siglo XIX, es decir, antes de que existiera la Argentina, ya que durante la época colonial llegaron al Río de la Plata y al Alto Perú numerosos marranos o criptojudíos. Otros, más osados, llevaron la cronología todavía más atrás, argumentando que los indígenas americanos serían descendientes de las Diez Tribus perdidas de Israel.

Así sea que consideremos cualquiera de estas cuatro teorías, en septiembre de 1939, cuando comenzó la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el largo ciclo de la inmigración judía a la Argentina estaba cerca de llegar a su fin. Para esa fecha, en el país vivían alrededor de 270.000 judíos, de los cuales el setenta por ciento residía en Buenos Aires, y cuyo peso demográfico sobre el total de la población cuadruplicaba al actual. Provenientes de distintos países, imperios y regiones, los inmigrantes habían traído consigo diferentes lenguas, bagajes culturales e ideologías políticas, e incluso diversos puntos de vista acerca de eso que supuestamente los conectaba entre sí: el judaísmo. Al estallar la guerra, la comunidad se encontraba bien organizada. La vida institucional había resultado fortalecida como consecuencia de la reciente creación de la DAIA y del Vaad Hajinuj (el Consejo Escolar), dos instituciones techo que permitieron unificar criterios respecto de temas clave, como la lucha contra el antisemitismo y la educación. Numerosos clubes, periódicos, sinagogas, círculos culturales, editoriales, cajas de crédito, cooperativas, hospitales, asilos y mutuales completaban un paisaje institucional capaz de cumplir con un objetivo central para el judaísmo moderno: sostener la identidad en un mundo abierto y secular. En la

La Experiencia Judía en la Argentina y el Impacto de la Shoá

Argentina de entreguerras, adeptos a las distintas ideologías judías construyeron sus propios espacios y manifestaron sus visiones del mundo a través del libro, la prensa, el mitin político y el teatro, participando de la querella por la identidad en la víspera de dos acontecimientos que transformarían la vida judía para siempre: la Shoá y la creación del Estado de Israel.