NOVEL ECOSYSTEMS: Interview with Dr. Marcus Collier

ECOCIDE AND COLONIALISM

Analysing Israel's Ecological Practices in Palestine

THE PRIMORDIAL WILD Are Humans a Part of Nature?

NOVEL ECOSYSTEMS: Interview with Dr. Marcus Collier

ECOCIDE AND COLONIALISM

Analysing Israel's Ecological Practices in Palestine

THE PRIMORDIAL WILD Are Humans a Part of Nature?

Editor’s Note

Welcome to another exciting year of Evergreen Trinity! I’m honoured to serve as Editor-in-Chief this year and can’t wait to share the wide range of stories our team has put together.

This edition was made possible by an incredible group of contributors — including recent graduates who wrote for us last term and generously allowed us to feature their work here.

A huge round of applause goes to our wonderful editorial team: Rachel Doyle, Ellen Duggan, Roisin Dolliver, Jane Freyer, and Darragh Doyle. Despite my ambitious expectations and tight deadlines, they worked tirelessly to bring this issue to life, and I couldn’t be more grateful for their dedication and creativity.

Evergreen Trinity was first published by the brilliant Aoife Kiernan and Faye Murphy with the goal of improving environmental literacy within the Trinity community. I’m proud to say this marks our fifth year of publication and third year as an officially recognised magazine under Trinity Publications.

If you’re interested in joining the Evergreen team in Hilary 2026, we’d love to have you! Reach out to editorevergreentrinity@gmail.com. I’m an obsessive email checker and will happily respond to any question, comment, or idea.

With all that said, I hope you enjoy this edition of Evergreen Trinity. I might be biased, but I truly think it’s our best one yet.

With love,

Maria Langworthy

Editor-in-Chief

VOLUME V, ISSUE I

Editorial Team for Vol. V, Issue I

Maria Langworthy, Editor-In-Chief

Rachel Doyle, Deputy Editor

Darragh Doyle, Treasurer

Copyeditors for Vol. V, Issue I

Ellen Duggan, Head Copy Editor

Roisin Dolliver, Layout Editor

Jane Freyer, Social Media and Outreach

Ellen Duggan Rachel Doyle Maria Langworthy

Photography & Artwork for Vol. V, Issue I

Bonnie O'Farrell

Genevieve McDonnell

Verdiana Di Maria

Jinxi Zhang

Kieran Lunn

Danna Dekay

Natalie Wynn

Quintin Lawlor Maher

Hannah Hung Sum Yuet

Contributing Writers for Vol. V, Issue I

Elise Zacherl

Roisin Dolliver

Charlotte Ledwidge Varvara Vasylchenko

Ruairí Goodwin

Bríon Ó Conchubhair

Maia Mulligan

Maria Langworthy

Merve Sahmaran

Rosemary Fogarty

Clara Gleeson

Max Lara Leonard

Emilie Higgins Charlotte Fox

Cherie Nicole Salo Kavin Aadithiyan

Disconnection in an increasingly connected world

IKEA: A "Fast Furniture" Reckoning Past Due?

ChatGPT in Academia: Plagiarism is Just the Tip of the Iceberg

Secret Social Network: What We Don’t Know About Trees

The Silent Killer of Europe: A continent threatened by heatwaves and the changing climate

Ecocide as a tool of Colonialism: Analyzing Israel's Ecological Practices in Palestine

Novel Ecosystems: Interview with Dr. Marcus Collier

The Truth Behind So-Called “Pollinator Friendly” Plants: What Garden Centres Don't Tell You

Green Labs: Interview with Dumitru Anton

The Primordial Wild: Are Humans a Part of Nature?

BRÍON Ó CONCHUBHAIR

In a rural Vietnamese town, one might buy a Venti latte from Starbucks. In Drumcliffe, Co. Sligo, king prawn satay is only one click away. The spread and proliferation of information, resources, population, and medicines across the globe is increasing at a rapid rate. Even in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic that grounded international travel and halted global trade, a study jointly undertaken by the NYU Stern School of Business and the shipping company DHL found that, by 2024, globalisation had returned to an all-time peak.

Despite its long history as a realised phenomenon, globalisation remains divisive; it is impossible to claim that it is entirely a positive or negative force, yet people do take a side. Multinational organisations, such as the European Parliament and the International Monetary Fund, maintain stances that encourage the acceleration of ‘global growth’. In many regards, there are immense benefits to increasing global connectivity, including improved medicines and access to health care, more variety and lower costs of goods, and “higher” standards of living. However, are medically prolonged lifespans and the automation of our l

daily lives unquestionably improvements to existence as a whole? Is it only our own hominid wellbeing that is deserving of nursing or longevity and care?

It is clear that the environment and our natural world are losing out in our increasingly globalised world. There are no quality-of-life improvements felt by a flamboyance of flamingos when clean drinking water is pumped from Lake Naivasha, nor are there enhancements to the mental wellbeing of a solitary platypus when underground ethernet cables are linked. The environmental impacts of globalisation are nearly impossible to quantify given that they encompass an acceleration of almost every facet of environmental decline through increased transportation of goods, heightened greenhouse gas emissions and interestingly, economic specialization. These points are fairly well understood by many of us, in spite of our lack of agency to make any impactful change to the ongoing devastation our planet endures at the hands of our ever-expanding anthropogenic empire.

However, there remains an aspect of the impact of globalisation on nature that receives much less critical understanding or attention. As we connect

further and faster via technology, we may well lose contact with what is right under our noses.

How many species can you distinguish in a chorus of birdsong in the morning? How many trees can you identify based on leaves or bark? Odds are if you are reading this article, more than most, but even as someone who has dedicated four years of their lives to the study of the natural world I don’t know nearly enough. What then can be said for your average commuter on their way to work? A separation seems to have emerged between ourselves and the world which we inhabit.

To exemplify, it has been observed that when Starlink

connects Indigenous peoples to the revealingly named World Wide Web, there is a subsequent decline in traditional practices both cultural, through dance and song, and in terms of survival, specifically hunting methods. Publications such as The New York Times remarked extensively upon the Marubo people of the Amazon basin who became “addicted to porn” and “lazy” following the advent of the internet. Many of these issues were later debunked or tempered. However, we need not look so far afield to see this bastardization of culture through globalisation.

Here in Ireland, we have a rich history of festivals and practices tied to the land and the changing of

the seasons. St. Patrick’s Day had its origins in the pagan festival of Ostara, held on the spring equinox to celebrate renewal, rebirth and the balance of both day and night. I would venture to guess though that this is not what most would associate St. Patrick’s Day with today. Through invasions by the Vikings and the English alongside the assimilation of the holiday by the United States, St. Patrick’s Day has lost all connection to the seasons and cycles of natural life.

"The same can be said for St. Brigid’s Day, Samhain, and many other traditional celebrations that are rooted in seasonal change and natural phenomena, having been lost to abstract religious, cultural and commercial interests, and reduced to days off work and hollowed out symbols."

Ironically, as we aim to improve our connection to the world at large, we seem to be falling more and more into a spiral of disconnect, individualism, and dissonance. These traits are, in my eyes, potentially more damaging for the future of our natural spaces than the transport of goods or other economic activities. Once we begin to think of ourselves as individual actors, only looking out for our own kin, we begin to forget our place as small parts of a holistic system. How can we expect humanity to repair and replenish that which we have destroyed if we lose the traditions and rituals that connect us to the earth and what it provides.

In Ireland we have slowly begun to reclaim our traditional celebrations and people seem to be making an effort to return to their roots. This shift is a slow process and an esoteric one at that; looking forward, globalisation is only accelerating and now reaching even the most remote communities and environments. There is no return, but perhaps we can attempt to harness some of the power in this interconnectedness to counteract its negative effects; to help spread ideas and information that more meaningfully and sustainably connect us to each other and to the world around us. Think about nature, speak about nature, write about nature, and represent nature.

ELISE ZACHERL

As we look behind the curtain of how afford able goods are made, we are increasingly forced to confront the ugliness behind our purchases.

There is a general consensus now that purchasing fast fashion, mass produced, and low cost clothing à la Zara, H&M and Penneys, is a decision that carries newfound weight. Unsafe working conditions, overconsumption of water, pollution and microplastics associated with the fast fashion industry coupled with ever decreasing quality of product has entered the public conversation pit.

Consumers began to demand increased accountability, or at least acknowledgement of impact, from fast fashion retailers. Government market watchdogs began investigating false sustainability claims, and consumer attitudes increasingly softened to the idea of a ‘capsule wardrobe’ which features items that can be worn again and again, or to ‘deinfluencing’ videos explaining how poorly garments are made.

The next reveal behind the mass production curtain? Furniture.

The general shift towards hybrid and work-fromhome policies and the spread of microtrends be-

yond clothing and into home furnishings come in the wake of the 2020 pandemic, bringing with them an increased demand for cheap, impermanent, instant furniture.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Americans discarded over 12 million tons of furniture in 2018, a 485% increase from 1960. In the 60s, however, discarded furniture was generally made of simpler materials.

Today, the aim to keep prices as low as possible has pushed manufacturers towards less robust materials such as particle board, composed of wood chips and sawdust mixed with glue.

"Think of the classic white IKEA desks. This material cannot be sanded or refinished as it ages and cannot be recycled due to the mixed materials, making the journey to landfill inevitable."

Over 50 years ago, Garrett Hardin, a biologist, published the incredibly influential essay The Tragedy of the Commons in Science. Hardin puts forward a simple parable: Herdsmen graze their cows in a shared pasture, but out of fear that the best grass will be eaten by another’s cattle, they all increase their herd without limit.

Hardin sees this as an inevitability, with self-interest driving all individuals towards ruin, destroying the benefits of the shared resource. Despite being generally refuted on account of the author being a known eugenicist and white nationalist, this rhetoric has been the weapon of choice in the modern culture war dance we engage in with major polluters.

Oil companies shifted from flat out climate change denial in the later 20th century, to the growing assertion that we all have a share of blame in the face of current environmental crises. In the context of fast furniture, this stance seems like the omnipres ent threat to our scattered attempts to establish a

circular economy. Direct to consumer furniture providers such as Wayfair and Amazon can shirk their responsibility so long as there is a framework which focuses on individual consumer behaviour rather than corporate accountability.

However, the deflation of post-pandemic fast furniture sales has pushed certain retailers to reconsider their approach. Now aware of changing consumer preferences and the ever salient boycott approach in our morality driven internet discourse, there is greater economic incentive to convince us that flatpacks are sustainable.

Leading the charge is fast furniture megagiant

IKEA, which established its “People and Planet Positive Sustainability” strategy in 2012, promising to make all products from recyclable and renewable materials by 2030. Since then, their promises have expanded to cover the full breadth of the IKEA value chain and franchise system. Operating in over 63 markets with an annual revenue commonly exceeding 40 billion, the IKEA strategy has always depended on their global footprint. IKEA sources materials from over 1800 suppliers across 50 countries, signing long term contracts on the condition that business partners abide by their IWAY Code of Conduct. This ensures the lowest possible prices for consumers and peace of mind for IKEA, most of the time.

Despite their best in class reputation, IKEA has battled continued scrutiny from environmental groups such as the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), a non-profit based in Washington, D.C., regarding concerns about their wood supply chain. Wood sourced from protected forests in Ukraine, Romania and Russia has been traced to popular

IKEA products as recently as 2024, but has avoided widespread outrage thanks to the general handDespite countless examples of unsustainable practices in FSC certified forests, the continued treatment of such scandals as isolated incidents has steered the conversation away from any meaningful structural reform leaving a fundamentally flawed organisation with the power to misguide well-meaning consumers at a premium price.

Verifying the sustainability of complex, multinational raw material supply chains underlines the necessity of vigorous, independent systems that will credibly report information, a need that extends beyond the fast fashion and furniture industries.

Voluntary certification schemes such as the FSC expel the responsibility to evaluate the quality and impact of a product squarely on the consumer. Governments must develop a comprehensive legislative framework to address supply chain issues and set rules that ensure no product presented to consumers comes from harmful practices, sustainability related or otherwise.

CHARLOTTE FOX

College students and staff today are poised on the brink of a critical technological frontier. Since Chat GPT’s initial release in 2022, all students have had to adjust to a new academic landscape, whether or not they have personally used the program. At Trinity, college staff have scrambled to keep up with the rollout of Chat GPT and the many dubious AI-detection sites that have followed in its wake. In the last two and a half years, students have received a confusing mix of threats, ethical talks, cautionary jokes, and supportive messages concerning our own use of the platform. Some students have had to attach statements to their essays acknowledging that Chat GPT may be used when cited, but for others, the statements warn, “Just as AI tools are evolving, so too are AI-detection tools. Turnitin has announced new capabilities to appear by the end of this year. Improper use of chatGPT now could come back to haunt you later.”

The growing consensus seems to be that lecturers should attempt to work with Chat GPT, rather than against it. More and more classes have purported the site as a helpful tool, wagged their fingers once more about the issue of plagiarism, and simply moved on. Many lecturers have been instructed to “Chat GPT-proof” their assignments, by

changing up their questions or requesting writing styles that are harder for the chat-bot to replicate. With all of the warnings, ethical debates, and semi-conclusions Trinity has reached on the regulations and morality of AI platforms like Chat GPT, it is shocking how often the most lethal component is left out of the conversation completely. The environmental cost of using models like OpenAI’s Chat GPT is under-discussed in our classrooms. Alongside the AI-centred plagiarism warnings that accompany almost every module’s set of guidelines, should Trinity’s lecturers be just as responsible for reminding students of the environmental risks that come with using AI?

The uncomfortable fact is that artificial intelligence is not artificial at all: it relies on a tangible substructure that has extreme planetary consequences. The argument could be made that colleges have as much responsibility to keep students informed of these as they do of the academic consequences.

In a step towards mapping out what exactly Chat GPT’s role should be in the scholarly landscape, we must outline one of its more concealed features: AI’s material basis, and its environmental cost. Open AI

itself does not disclose the number of servers and computers needed for its models to run, the number of data centres it uses, or any specific information regarding the amount of energy these data centres consume. However ambiguous the exact ecological impact of Chat GPT specifically is, it cannot be removed from the impact of AI models in general. Machine learning models require significant electricity during their training phase to power servers and cool data centers.

Beyond training, it is known that AI systems like ChatGPT need substantial amounts of energy for daily operations. Data scientist Kasper Groes Ludvigsen has estimated that ChatGPT produces approximately 522 tCO2e (greenhouse gas emissions) per search query. That is equivalent to the greenhouse gas emissions from about two million kilometres driven by the average car. Given the high volume of user interactions, this means the model could generate up to four tons of CO2 (carbon dioxide) per day. Since the internet largely depends on fossil fuel-generated electricity, there is a high probability that AI operations are fueled by non-renewable sources, raising serious questions of the sustainability of frequent Chat GPT use.

The “Birthplaces of AI” are described by political scholar Kate Crawford as the places where minerals needed to build and power computerised systems are found. One example is the Silver Peak lithium mines in the US state of Nevada - an expansive underground lake in a spot somewhere between Death Valley and Yosemite, swallowed by desert. Lithium is an essential component of rechargeable batteries,

though an even more essential element in our ecosystems. Once made, these batteries don’t live forever. They die, more lithium is mined, and the battery carcasses pile up. Tesla, for example, is responsible for half the planet’s total lithium consumption. Smart devices, with their lifespans, see a similar fate as they degrade over the course of just a few years and then are tossed into vast technological dumping grounds in countries such as Pakistan and Ghana.

More ‘Birthplaces of AI’ include lithium mines in Bolivia, tin mines in Indonesia, more mineral mines in Congo, Australia, and so on. Rare earth minerals are needed for everything from earphone speakers and camera lenses, to GPS satellites and military drones. Not only is the mining of these minerals depleting our planetary resource bank, but it is also a source of great local conflict and global violence. The world’s top financial powers vie for control over the zones that contain these precious minerals, bringing war and devastation to the target and surrounding areas. In Congo, mineral mining funds militias, which have kept the region at war for years. The labour practices in the mines themselves have been referred to as modern slavery. The site of an artificially created ‘black lake’ in Mongolia contains toxic chemicals that have poisoned and polluted the area, forming mass quantities of ammonium, acidic water, and radioactive residue. These mineral mines and toxic lakes existing in deserted, remote locations contribute to the idea that the cloud is an intangible, artificial creation. Distancing the data centres from populous areas furthers public ignorance about the real, material basis of artificial intelligence.

As we know,

”AI only profits some because the cost is shunted onto others, in both present and future generations.”

Think of the data centres moving to Ireland en masse (there are currently 95 and counting), and tech giant offices that have cropped up in the Dublin Docklands, driving rent prices through the ceiling. Or similarly, the ‘titans of tech’ that have infiltrated San Francisco and the wider Silicon Valley, pushing thousands of people out of their homes with no rights to basic services, resulting in a massive human rights violation condemned by the United Nations.

An AI system cannot function without a battery, and so it can not function without the mining of precious minerals, sending the planet into further degradation with each extraction. So much of modern existence has been crystallised into data, and backed up to ‘the cloud’, without much consideration for the material cost of such a process. Kate Crawford explained in an environmental impact essay: “The cloud is the backbone of the artificial intelligence industry, and it’s made of rocks and lithium brine and crude oil.” In their article “Dark data is killing the planet – we need digital decarbonisation”, Professors Jackson and Hodgkinson explain the notion of ‘dark data’ – digital photos, files, and recordings used once or twice, and then forgotten in a vast cyber-abyss. Our data that piles exponentially by the day has a corporeal counterpart, requiring more and more energy to store. They link all of this digital litter

to its large carbon footprint, explaining: “Even data that is stored and never used again takes up space on servers – typically huge banks of computers in warehouses. Those computers and those warehouses all use lots of electricity.”

All over the world, forests are bulldozed, miners are worked to death, and animals are driven to extinction - all to feed the bottomless appetite of AI’s expansive supply chain. ‘The cloud’, despite its atmospheric namesake, relies not only on earthly minerals but copious amounts of fossil fuels to keep itself running. AI, and in fact the entire tech industry, maintains a public image of environmentalism and hopeful, tech-based climate solutions. In reality, electrical energy is consumed by the bucketload for these computational systems to function, and they spit carbon emissions back out. How much energy exactly the AI system consumes is not public information - the corporations involved are the close-fisted gatekeepers of this data. Meanwhile, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon all licence their AI models, engineering labour forces, and infrastructure to fossil fuel firms.

Finally, there is the logistical factor. Global tech commerce comes at a cost of its own. The cargo shipping fuel, toxic waste in the oceans, and the

low-paid employees who do the dirty work– all of this adds to the earthly, physical trail of destruction platforms like Chat GPT leave behind.

Students are increasingly given the choice to use AI platforms for their assignments, which is undoubtedly a complicated and difficult situation to navigate for school faculty and administrators. But students should be given the opportunity to make informed choices about using AI, which includes the environmental costs of generative AI’s many systems and models. Trinity’s official website includes lengthy chapters for both staff and students surrounding the use of AI and its ‘limitations and capabilities’, including many links to further research and guidelines on the topic.Yet, not a single one of these pages contains any information on the environmental, or material, side of the equation. Trinity, like many institutions, has grappled with the ethical and academic implications of AI, yet the environmental consequences of generative AI remain largely absent from the conversation - an omission that must be addressed if students are to make truly informed choices about their use of these powerful new technologies.

VARVARA VASYLCHENKO

Trees possess the extraordinary ability to tackle multiple environmental problems at once. Known as Earth's oxygen generators, they absorb carbon dioxide, improve air quality, cool the environment, prevent soil erosion and provide habitat for countless species - from birds and squirrels to insects and microorganisms. Yet trees in modern, human-managed forests often appear to be less resilient than those in ancient, untouched woodlands. So what secret do natural forests hold?

For a long time, trees were seen as solitary beings competing for water, sunlight and nutrients. However, recent research has completely overturned this view. It was revealed that trees are not isolated at all; instead, they form an underground network, helping each other to survive. Their communication is made possible by a remarkable symbiosis with another species - fungi. The thread-like vegetative body of fungi, known as mycelium, acts like a cable, linking trees by weaving around and through their roots. This “wood wide web” allows trees to share resources, warn each other about pests and balance nutrient distribution. In essence, it functions like a “social support” system that ensures no struggling members of the tree community are left behind.

Remarkably, despite differences in age, access to sunlight, amount of water and composition of soil, trees in ancient forests photosynthesise at nearly the same rate. This would be impossible in a purely competitive environment because weak and sick trees would never match the performance of strong plants. In the natural environment, cooperation overrides competition. In contrast, commercially exploited forests show large differences in performance. Clearings create physical gaps that disconnect the root systems, making it harder for trees to exchange nutrients. Therefore, the redistribution is less evident because trees cannot reach each other.

Research by María A. Crepy and Jorge J. Casal has shown that trees can even behave altruistically in favour of their family members. When an Arabidopsis plant is located close to its genetic relative, it adjusts its leaf position to allow its neighbour more sunlight. This kind of considerate behaviour is particularly evident in ancient forests, where generations of related trees have been living side-by-side for centuries. By giving space to each other, trees maximize the total leaf area exposed to sunlight, benefiting all members of the tree community. As a result, trees growing among their kin produce more seeds and biomass.

Even more astonishingly, trees can recognise and nurture their own offspring. Through underground root networks, “mother” trees identify their seedlings and send them water, nutrients and sugar solutions. This support is vital for young trees, whose roots are too short to access deeper groundwaters, making them more vulnerable to droughts. In a packed forest, most water from the rainfall also never reaches the ground, becoming trapped in a dense leaf canopy. As a result, small trees would barely satisfy their thirst with scarce summer droplets. Without parental care, most saplings would not survive harsh weather conditions.

Unfortunately, the modern forestry industry rarely considers these natural bonds while planting trees. Some saplings are lucky enough to have a large tree nearby, but those growing with no trees around become unprotected “orphans,” left vulnerable to storms, devastating droughts and hungry herbivores. Greater “social” distance also limits their access to the underground network, reducing their chances of receiving support from neighbouring trees.

Forests composed entirely of young trees are also less efficient at saving water for the future. Shallow saplings’ roots cannot physically uptake as much water as mature trees would, so most of the liquid seeps underground. The absence of older trees weakens one of the tree community’s climate-regulating functions: cooling the temperature. Mature trees store huge amounts of water, evaporating it during the hot season and acting like forest’s natural air conditioners. Small trees cannot absorb the same volume, so newly planted young forests do not regulate the temperature as efficiently as intact woodlands do.

Nonetheless, it should be admitted that growing in dense forests comes at a price. Large trees create a shade, which prevents most of the sunlight from reaching the sapling. Parental supply of sugar solutions does not fully compensate for the lack of sunlight, which makes young trees grow extremely slowly, often remaining under the mother’s shade for decades or even centuries.

Sometimes poor nursery practice can also harm the most delicate and intelligent part of a tree - its roots. Roots do not just transport resources and store water - they are sensory organs used for detecting dozens of parameters, including temperature, moisture, soil chemistry, gravity and the presence of other plants and bacteria. Based on this input, trees alter their water intake, cooperation with other organisms and growth direction. In the wild, a 40-centimeter beech extends its roots to 1 square meter, striving to access as many locations as possible. This makes replanting a tree that has a developed root system nearly impossible without causing damage. This would imply transporting a block of soil as well, so nursery trees are often trimmed before planting.

While pruning does stimulate root growth, serious harm prevents future roots from growing as deep and wide as they could have. This leads to reduced water and nutrient absorption, slowing down the growth rate. Damaged roots also produce less root exudates (sugars used for interaction with soil microorganisms), which disrupts communication and symbiosis with other species. Such trees with less developed root systems are poorly attached to the ground, which affects their stability and increases the likelihood of being blown down by strong winds. Therefore, storms might have a more devastating impact on modern forests than untouched ecosystems.

All in all, forests are not mere collections of trees

In forestry, restrained growth is generally seen as a problem. In order to accelerate it, the industry came up with thinning - a practice of removing “competing” trees so that the remaining ones receive more sunlight. Appreciating the opportunity, survivors grow faster and taller, reaching maturity within several decades. However, speedy development comes with its hidden costs. A slow growing pace in the shade allows trees to develop strong wood, making them more resistant to storms. Their solid trunks leave little room for fungi to invade, so they are also less susceptible to disease. In contrast, trees that expand rapidly have lighter and more porous wood. They are structurally weaker, break more easily, and live shorter lives. Reaching maturity sooner, they exhaust their resources quicker and die sooner as well. Their shorter lifespans undermine one of the forest’s crucial functions: long-term carbon storage. Trees expand in diameter with every passing year, taking up more carbon as they become older. Beeches and oaks, for instance, sequester carbon dioxide at the same rate for 450 years before slowing down for a little. In fact, one large tree stores more carbon than a lot of small saplings taking up the same space. Unfortunately, fast-growing trees rarely reach old age, which significantly limits the amount of carbon they can store.

- they are living communities that need cooperation to thrive.

“Ancient woodlands remind us that true power lies not in the vicious cycle of competition but in reciprocal relationships.“

If we hope to restore self-sustaining and climate-resistant forests, we must look beneath the surface and acknowledge their invisible networks.

Some insights are from ‘The Hidden Life of Trees” by

Peter Wohlleben

CHARLOTTE LEDWIDGE

European history can be traced by many different landmarks in time: world leaders, conflicts, Eurovision winners, language, and, now, extreme heatwaves. In the 1950s, Europe faced its first major heat wave event, where Stalingrad reached temperatures of 37° Celsius for the first time on record. Since then, the continent has been plagued by heat-related disasters. The 2003 heat wave shocked the world when 14,800 temperature-related deaths were recorded in France alone. Similar events have occurred in 2006, 2007, 2010, 2014, 2015, 2022, 2024, and now 2025. This is not just a pattern, but a climate crisis. Europe has consistently experienced scorching summers for over a decade, and the effects of these heat waves are only expected to worsen as we progress into an unstable future.

The entire planet is warming up as the web of the Anthropocene thickens, yet Europe remains the fastest-warming continent in the world. This summer, two main heat wave events targeted Europe, one in mid-June and one occurring between late June and early July. This prolonged heat is caused by a heat dome, a high-pressure system that traps heat over a certain portion of the Earth’s surface, preventing the

build-up of cloud coverage and rainfall. Recent research from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimates that approximately 24,000 people across 854 European urban areas died from heat-related events across the summer of 2025, 68% of which can be attributed to climate change.

Like most things in nature, the human body can only withstand so much damage before it begins to fail. In recent summers, there has been a pattern of increasing heat stress days, where the body is pushed to its limit. The sheer levels of heat and humidity on these days can cause exhaustion, heat stroke, and now death. A 2024 study published by the journal Sustainable Cities and Society shows that the effects of extreme heat and heat stress days are worst experienced by vulnerable people in society. Due to unequal distribution of social resources and varying degrees of heat wave resistance, people with chronic health conditions, older people, pregnant individuals, disabled people, and often those with a lower educational level, suffer the physiological and psychological effects of extreme heat on a much worse level. Compound heat waves can worsen the effects of cardiovascular and respira-

tory disease. Similarly, with increasing temperatures comes the threat of increased heart attacks and strokes, as the heart is forced to work harder to keep the body alive. Chronic illnesses such as asthma are also worsened due to the links between increasing heat and increasing ozone pollution.

Coping with extreme heat demands the body to function in ways it might not have had to before. For older people, this is often hard as their bodies lack the heat-adaptive behaviours to do so and struggle to regulate themselves. On the other hand, while young people can often cope with the physiological aspects of heat waves, the psychological impacts are long-lasting. The same 2024 study highlighted how high heat wave exposure in young people has brought about depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress syndrome in our younger generations. Social isolation for all age groups is a major issue during extreme heat waves, and the need for support networks is becoming more prevalent. A degree of heat wave preparation, stockpiling resources, and first aid knowledge is now perceived as standard in many European countries, especially in cities where the urban heat island effect comes into play. Not all people have access to these things, and therefore, there is a need for continent-wide “heat injustice mitigation strategies”.

This summer’s heat waves saw a massive disruption in the daily lives of millions across Europe. A June 2025 article in the Guardian highlighted the experiences of European countries: evacuation orders

were established in Greece due to wildfires, Sicily was forced to ban outdoor work during the hottest hours, and all public swimming pools in Marseille became free for residents. In other areas of France, schools were closed, and the Eiffel Tower also shut its doors. These measures hugely impacted the social lives of people but also saw a cessation of income for some workers and disruption to tourist activities. For many European countries, a significant sector of the economy works in tourism, with reliance on seasonal weather patterns attracting people to visit. Due to global warming, there has been decreased snow coverage in the Northern Hemisphere for many winter seasons, and now, with extreme heat in the summer, the face of tourism across Europe could be met with major changes in the future.

The July heatwave of this year extended up to Northern Europe, causing major implications for Scandinavian countries. Norway, Sweden, and Finland were previously protected from these extreme heat events, with their higher latitudes and colder, mild climates.

However, this pattern has broken as the 21st century has progressed. Global warming has put these countries under immense ecological and social stress according to research by the World Weather Attribution: Finland experienced a record 22 consecutive days of temperatures higher than 30° Celsius this summer. The surge in temperatures across Scandinavia this July saw an increase in algal blooms, wildfires, hospital overcrowding, and overheating, as well as at least 60 deaths due to drowning. Fauna across the Scandinavian peninsula also suffered, namely the native reindeer population. These reindeer have never experienced temperatures like this before, or for so long.

Some died as a result of the heat, while others ventured into towns and road tunnels in search of shade and protection. These heatwaves are expected to become five times more frequent by 2100 according to current global warming patterns, a major concern for the Scandinavian population whose buildings and resources were not designed to withstand such weather conditions.

All across Europe, the increased heat has meant electricity grids are put under immense stress. As temperatures increase, so does the demand for power, and with increased demand, increased prices follow.

Air conditioning units, hospital machinery, and communication devices require electricity to keep people alive during intense heat waves.

“According to a 2025 report by global energy think tank Ember, the 2025 heatwaves increased daily power demand by up to 14%.“

This saw an increase in the average daily electricity price by 106% in Poland, 108% in France, and 175% in Germany, according to a report by EMBER. Power outages occurred across the continent as grids overheated and shut down. The cooling of these grids can be heavily reliant on water supply, and in times of heat and drought, this can prove difficult when the demand for power and the de-

mand for drinking water are racing against each other. Several nuclear power plants across France operated under reduced capacity while one, the Golfech plant, was forced to shut completely.

A 2025 study published by Nature Medicine estimates that an additional 2.3 million temperature-related deaths in Europe can be expected by the end of the 21st century if current warming patterns continue. Global greenhouse gas consumption is now responsible for tens of thousands of deaths each year, to both humans and wildlife. To minimise the number of fatalities, it is essential to convert to renewable, clean, and adaptive systems worldwide that can not only save us but also the planet.

ROISIN DOLLIVER

Palestine lies on the Great Rift Valley at the crossroads of Africa and Eurasia, a landbridge between the two which is home to five major ecological zones. Despite its small size, Palestine has been home to over 2500 wild plant species, 380 bird species , 91 reptile species and 130 mammal species. This rich biodiversity directly contradicts the terra nullius narrative proposed by the Zionist State, depicting the region as empty, barren, and ownable. Despite the Zionist slogan of “Making the Desert Bloom”, anthropogenic and colonial activities have resulted in 50 percent of the mammals, 20 percent of the local birds, and 30 percent of the country’s reptiles adopting endangered status (Braverman, 2023).

The “Draining the Swamp” project, is an example of the damage the Zionist project has wrought on the Palestinian landscape. Under this scheme the wetland ecosystems of the Huleh Valley were destroyed to create agricultural land. Zionist geographer Yehuda Karmon described the region as “malaria-infested, largely swampy and endangered by floods almost every winter; its people, poverty-stricken and led a wretched life in reed huts and mud hovels”. As Mazin Qumisyeh noted in his 2024 visit to

Trinity, “Draining the Swamp”, has resulted in the disappearance of 218 species (Qumsiyeh, 2024).

The Zionist settler state views nature management as a central aspect of their project, claiming that actions taken in the name of environmental protection are apolitical and justifying their operation beyond Israeli territory. Uzi Paz, a founder of Israel’s nature administration states that “The protections [we established] came from the love of nature, without even a drop of politics in it. It was pure and totally clean of such thoughts.” (Braverman). Qumiseyeh, alternatively, claims Nature Reserve boundaries are drawn purposefully to exclude and dispossess Palestinian communities. Critics of the Zionist regime claim the true motivation for Nature Reserve delineation hides in both the strict legislation and regulations that can be imposed on an area once it has been established as a Nature Reserve, and in their strategic placement preventing the development of Palestinian settlements.

Under the Oslo II Accord, the Israeli-occupied West bank was organised into three administrative divisions, Area A, subject to Palestinian authority, Area B

administered by both Israel and Palestine and Area C under Israeli authority. Area C comprised 61% of the occupied west bank and the majority of nature reserves and parks, two thirds of which were later declared military firing zones .

“In 2020, Naftali Bennet, who was the Israeli Defence Minister at the time declared seven new nature reserves and the expansion of twelve others in Area C, around 40% of which were on privately owned Palestinian land.“

These reserves then come under Israel’s Wild Animal Protection act of 1955 and its Nature and Parks Protection Act of 1998, legal protections which apply even to privately owned land, constraining cultivation and access without compensation. In occupied territories this declaration is made through military order, authorising enforcement from park rangers. The order allows the demolition of any structures built without written permission from the military commander. Ori Linial, the head of Wildlife Trade and Maintenance Supervision Unit and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority (INPA)’s Law Enforcement Division describes the brutal efficiency of military law in the occupied West Bank, boasting “Here, the head of the Civil Administration personally knows all our staff… I would tell him that I wanted to remove a Bedouin neighborhood that was built in my reserve, and he would personally give me the manpower to do that” (Braverman, 2023). Another exemplar of the severity of Israel's

approach to environmental management are the Green Patrol, a special unit of the INPA which does not operate under the police nor answer to them.

One of the Green Patrol’s objectives has been to intimidate Bedouin campsites into moving, even by a few meters, to reset the ten year occupation period after which Israeli law stipulates that ownership of land is established (Falah, 1985). They also police “dangerous overgrazing”, by Bedouin flocks under the 1950 Plant Protection Act, which prohibits the grazing of black goats “outside one’s own holdings”.

Another case study is the Wadi Qana valley, also referred to as Nahal Kana. In 1926 the British Administration declared a 7,400 acre forest reserve in the area, followed by the creation of the 3,500 acre “Nahal Kana Nature Reserve” by the Israeli Civil Administration in 1983. The entrance to Wadi Qana is in close proximity to the Jewish Settlement of Karnei Shomron and the Palestinian Village of Deir Istiya, who have used the land for agriculture and recreation for centuries. A baseline study conducted by Qumsiyeh identifies five freshwater springs in the valley, a habitat characterised by mixed Mediterranean forests and red clay soil, and six rare plants not found elsewhere in the West Bank; Overall 253 plant species occur in Wadi Qana, with a particular abundance of Phillyrea latifolia, the green olive tree (Qumsiyeh & Al-Sheikh, 2023).

Braverman describes first-hand the methods employed to dispossess Palestinian residents at Wadi

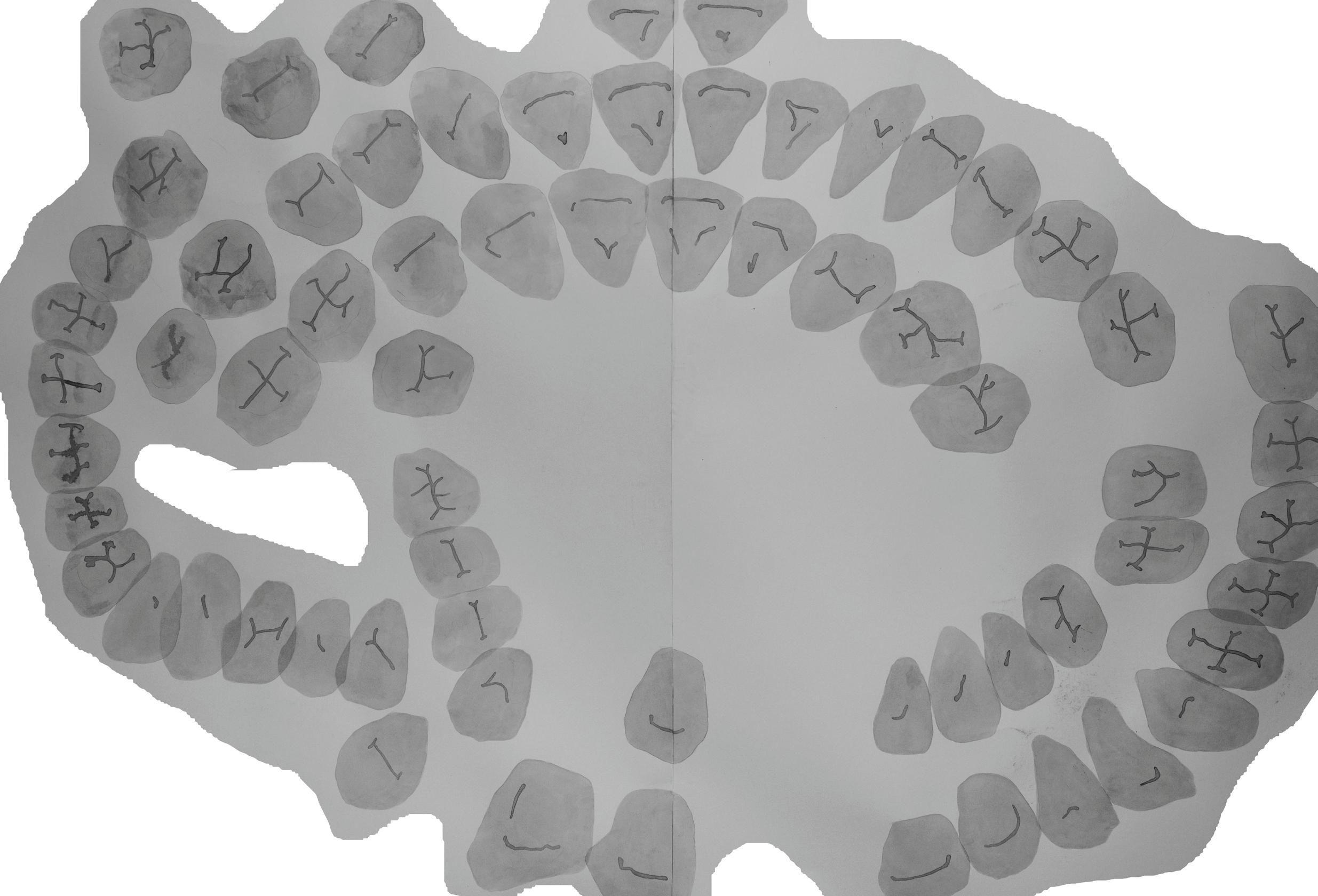

MAX LARA LEONARD

The tents from TCD BDS encampment left indents in the grass. This piece maps the impression we leave on the land.

Qana, including constant surveillance, the prohibition of new settlements, demolitions and olive tree uprooting. She spoke to Nazmi Salman, a member of the Deir Istiya council, who described a recent ban on staying overnight in the Wadi. Palestinian families had been ignoring the ban in fear that upon leaving the Wadi they would not be allowed back in. As such they were subject to regular military raids. Movement is monitored in the Wadi by drones and INPA employees. As noted previously, in occupied Nature Reserves, under military order rangers are permitted to demolish any structure not present at the formation of the reserve or built without permission of the military commander. The alteration of any settlement characterises it as a new structure. Salman added a tarp to the roof of his hut, which

justified the demolition of the building. Salman also describes how demolition orders, which are supposed to be issued ten days prior to action and subject to appeal, are hidden beneath rocks or behind trees to make them more difficult for farmers to find.

The uprooting of olive trees has been a source of great contention between the INPA and Palestinian residents in the Wadi. The INPA claims that the terrace building, irrigation, ploughing and water resource use of the olive tree planting is damaging to the reserves and other flora and fauna. On one occasion they applied for the uprooting of 1,500 olive trees, which was protested by the tree owners who brought the case to Israel’s High Court of Justice. They protested the allegation that the ol

ive trees were damaging to the landscape, having existed for centuries, and argued that their uprooting was discriminatory when compared to the environmental degradation caused by the licensing of dozens of Jewish permanent structures. The conclusion reached was that only trees under two years of age would be uprooted. However, Palestinian owners claim trees were marked for removal arbitrarily and over 800 were eventually removed. This is one of many instances of uprooting in the Wadi and across Palestine. Overall since 1967 over 2.5 million olive trees have been removed from the West Bank. In addition Palestinian communities have had their access to the Wadi’s springs restricted, and the Jewish presence in the Wadi has been solidified by the marketing of the reserve as an ecotourism destination. Braverman also notes that the entrance to Deir Istiya has on occasion been blocked for weeks in response to alleged rock throwing or tyre burning by its inhabitants. As a final note, the proposed expansion of the separation wall in Wadi Qana would separate the residents of Deir Istiya from their lands in the Wadi, placing those lands on the “Israeli” side.

The concept of Nature Reserve delineation to prevent Palestinian development is described by Amro and Najjar, who claim the Israeli government has misused green and open landscape concepts, and their associated planning tools to expropriate Palestinian Lands in East Jerusalem. They posit that to achieve the Zionist ideal of a constant Jewish majority, green areas are declared around Palestinian settlements and later developed into Jewish settlements that prevent the aforementioned Palestinian areas from

developing or expanding. They use the example of Abu-Ghneim Mountain, declared a protected green space in January 1997 and developed into the Israeli settlement of Har Homa in 2005 (Amro & Najjar, 2011).

Joanna Claire Long similarly suggests that the extensive pine afforestation projects of the Jewish National Funds (JNF) are primarily used to naturalise the Zionist colonisation of Palestine (2005). She posits that the perception of trees as positive additions to an environment was utilised by the JNF to disguise the political nature of their work. The afforestation of Israel has been a key component of the Zionist ideal. Long theorizes that not only do the projects have no true ecological motivations and are the product of ecologically unsustainable green propaganda, but represent active efforts to displace Palestinian settlements and disguise the remnants of those villages destroyed during the 1948 war. She notes the work of Joseph Weitz, the JNF Director of Lands and Afforestation Department from 1932 to 1967. Weitz, a Zionist, has been praised for his establishment of the Yatir Forest, a conifer plantation in an area that receives less than two hundred millilitres of precipitation a year . Weitz believed the success of the Jewish population in Israel was dependent on the complete “transfer” of all Arab communities. In 1940 he wrote, “Amongst ourselves it must be clear that there is no room for both peoples in this country… With Arab transfer the country will be wide open for us” (Long, 2005). During the 1948 war thousands of Palestinans fled to avoid the violence or were expelled by Jewish forces. To capitalise on this exodus and prevent their return Weiz proposed the creation

of a “Transfer Committee”, whose purpose was to prevent the return of Arab populations.

“Long notes that of the 418 villages depopulated and demolished during 1948, only 71 are not tourist and recreation sites managed to some degree by the JNF, and half of these are covered or surrounded by JNF forests.“

Professor Qumisyeh notes that not only are pine forests poorly suited to the mediterranean environment, but that their acidic leaf detritus prevents the propagation of the undergrowth, and increases risk of forest fires: the JNF disregards this ecological damage in favour of quick growth rates (2024).

Long also discusses that the intensity and defense of the JNF forestry projects are driven by a deep rooted association between the Jewish people and those trees. Many of the forests are dedicated to victims of the Holocaust, and embody both the Jewish history and future. Similarly the Israeli population has come to associate the Palestinian people with “problem species” such as the black goat, camel, olives, and feral dogs. These species are subject to many of the same restrictions imposed on human communities in the Nature reserves, and are targets of confiscation, quarantining, mass poisoning and extermination (Braverman). The Zionist leader Theodor Herzl felt such antipathy to the Palestinian archaeophytes that he praised the idea of “driving the animals together, and throwing a melinite bomb into their midst” in

his manifesto, The Jewish State (Braverman, 2023h). The Israeli Plant Protection (Damage by Goats) Law of 1950, more commonly known as the Black Goat Act, limits the number of goats allowed to graze in an area to “one goat per 40 dunams in unirrigated land, and one goat per ten dunamns of irrigated land”. This inhibits the black goat, once ubiquitous with the Palestinian landscape and means of production (Tanous & Eghbariah, 2022). Conservationists praise the ecological benefits of goat grazing for fire prevention. This benefit has now even been recognised by the INPA (Braverman, 2023i). As such the Plant Protection Law has been cast aside, but the damage it caused is not easily reversible.

Other species populations have prospered from biblical associations. The Zionist state sees the return to biblical analogues as another essential step in its formation. As such they have prioritised the reintroduction of species with biblical significance, including the Persian fallow deer, the Asian wild ass, and the Arabian or white oryx. These introductions aim to help connect the Israeli community to their environment and “eliminate from the landscape the former Palestinian presence”, as stated by Palestinian scholar Edward Said (Braverman, 2023n).

The settlers' approach to environmental management and its role in colonialism is not novel to Palestine-Israel, and is mirrored across history, for instance in the eradication of Bison in North America, another species of great importance to their indigenous community. In 1986 Alfred Crosby coined the term “ecological imperialism”, to express colonisa-

tion as a form of environmental terrorism. Concurrent with this idea Qumsiyeh states that the ethnic cleansing of Palestine was not limited to its people but extended to the greater environment and species associated with them. Braverman goes so far as to claim that any form of land management, unless explicitly anti-colonial, runs the risk of supporting its ideal. “Much Western nature management is so entrenched in colonial forms of knowledge and modes of thought that, unless intentionally resisted, its administration innately promotes their underlying structures” (Braverman, 2023e).

The restoration practices undertaken by the Israeli State, particularly in relation to nature reserves, afforestation projects, and the management of protected areas, reveal a complex intersection of environmental conservation and colonial objectives. The Zionist State’s conservation strategies often align with broader political goals, particularly the dispossession of Palestinian communities and the establishment of a settler colonial state. Critics such as Qumsiyeh and Braverman highlight the inherent political motivations behind these conservation practices, emphasizing their role in the broader Zionist project.

“These efforts reflect a pattern of ecological imperialism, where land management and restoration are not neutral acts but are deeply intertwined with colonialism and the erasure of indigenous presence.“

icies underscores the importance of recognizing the political dimensions of conservation and the need for an anti-colonial approach to environmental restoration.

Ultimately, the analysis of Israel’s environmental pol-

RUAIRÍ GOODWIN

Marcus Collier, the associate professor of sustainability science in the discipline of botany — where he also serves as head of discipline — joined Trinity College Dublin in 2017 for Connecting Nature, a project on nature-based solutions. In 2021 he received a European Research Council Consolidator Grant for NovelEco, a study examining how society perceives wild spaces in cities.

Q: What are novel ecosystems?

“It's a very new term and controversial term. It's not considered a scientific term per se. It's still a concept, theoretical in nature, of ecosystems that are created by people. We know that humans have a huge impact on the planet and on ecosystems, and in the vast majority of cases these ecosystems retain some of the footprint of human activity with invasive species, garden escapes, or crops that have gone into the wild. When we talk about restoring an ecosystem, it may not be possible because there's all these residual plants and animals that we brought in and transported all over the world. So, the ecosystem is considered a novel ecosystem in the sense it can never be restored to its original form. We can make a facsimile of an earlier ecosystem, but even those were impacted by early humans. For example, an urban area could never simply be torn down and replaced with forest. And even if we did, we'd still be left with all those human remains of plants and animals that were brought in. It contains plants and animals that would never normally be found together in an analogous ecosystem outside the city or somewhere else.”

Q: Where might we see these ecosystems around Dublin or Trinity?

“We’ve created a couple of wild spaces in Trinity, but they're not necessarily novel ecosystems, it's more of a rewilding effort. There are quite a lot of locations where, for example, abandoned lots, buildings in dispute because of our housing crisis, or toxic areas such as parts of the Docklands. As it would cost a tremendous amount of money to rehabilitate the land, they're just left there as brownfield sites, doing their own thing. There you’ll see plants like escaped crops — oil-seed rape, tomatoes, onions — alongside native species, animals and insects. There is one embankment out near Kilmainham, just outside the Royal Hospital, which in recent decades contains a lot of plants that are escaped garden species and so on. There are little pockets and corners of abandoned gardens and areas behind hoarding where no one can actually see them. So, there's a surprising amount. We haven't been able to map them because they change. One year, someone will come in and see all this stuff, and the council will come up with a sprayer or with a strimmer and strip it all down to the bare. And then they leave it there, and then in about five years’ time, it'll all be back again in a different combination of species.”

Q: Speaking of monitoring sites like these, how do you use citizen or participatory science in your research?

“There's a lot of apps out there for recording and identifying plants. The National Biodiversity Data Centre, for example, is a great resource because people voluntarily upload unusual things they might see. It's a very good way of keeping track of invasive species in real time. As you might have seen in the news, the Asian hornet is a very good example of citizen recording. But what I'm doing is asking citizens not just to identify what species they see, but what those plants and animals mean to them. We have an app that people can use when going out looking at nature. It asks how close and connected they feel to nature. During their walk, they can identify and upload plants, contributing to an ecological database. At the same time, we ask how the experience changes their feelings. Using an emoji-style system, they record their relationship and their sense of connection to nature before and after the walk. Usually, we see that as people become more focused on plants or animals, often plants that will be sprayed or removed, they tend to feel closer to nature. So, we're able to say quite clearly that by engaging with these wild species and spaces, in an urban setting, it brings you closer to nature. This is important because for years people have been removing themselves from nature, becoming distant from it. And we know that this disconnection from nature is fundamental to our unsustainable behaviour. So, if we bring people closer to these wild spaces, like novel ecosystems, we can bring them closer to nature. It means they change their viewpoint, their emotional relationship with nature, and they're more likely to be more sus-

Q: Where do you see the future of this research?

“We’re nearing the end of the project, but not a lot of people have uploaded data yet. We've had a couple of hundred people use it so far in different countries, which means we get two datasets. Dataset number one is simply a record of what is growing in cities. That dataset, because it's geolocated, will be available for other researchers to use. The social science data is completely protected under GDPR, so that goes into a different type of system where it's anonymized. For that dataset, we need an awful lot more people to start using it in order to get a representative sample. But so far, it's going in a particularly interesting trend. We can see that people of all age groups will become more connected with nature when they see a plant or animal at the side of the road, for instance. As it's more citizen-focused, those papers that we produce will have citizens as authors. They'll be offered the opportunity to not just participate in the research, but also to author it. At the beginning of the project, we also asked them to develop the research questions with us. We had an idea of what we wanted to do, but within that realm, we asked people what they would like to discover about plants or animals in their area. Amazingly, we got 80 or 90 different research questions, for example, are plants different in different social classes? Are the weeds that grow in a working-class neighbourhood different? We were getting also some race issues in terms of different parts of where we were doing our research in New York, and also in Melbourne. In Australia, we were getting questions about indigenous people's relationships with wild spaces versus Europeans' relationships. Very different and possibly quite controversial questions, but wonderfully articulated, and incredibly important.”

In Ireland, one-third of wild bee species are threatened with extinction. While campaigns to protect pollinators are becoming more and more common, misinformation and misleading marketing is muddying the waters. Pollinator-friendly gardening is much more than just choosing the plant with the most flowers.

The State We’re In Insects, including wild bees, are the most important pollinators in Ireland. Ireland’s insect pollinators include one honeybee species, 21 bumblebee species, 77 solitary bee species, and 98 wild bee species. Bees are responsible for the bulk of this pollination. A variety of both indirect (human population growth, urbanisation, agricultural intensification) and direct drivers (habitat loss, disease, and exposure to toxins) has led to the decrease of over half of Ireland’s bee species since the 1980s. Today, one third of our wild bee species are threatened with extinction. This isn’t just a problem for bees, it's a problem that has far reaching effects for us all.

EMILIE HIGGINS

Why Pollinators Matter (Hint: It's not just because they're cute)

Pollinators are essential to life as we know it. In Europe, 78% of plants are animal-pollinated and nearly all (84%) of Europe's crops are animal-pollinated. In Ireland alone, this key ecosystem service is valued at over 50 million to the economy. In fact, up to 59 million per year is produced in animal-pollination dependent food crops.

The benefits of pollinators reach far beyond economics, pollinators play critical roles in ecosystems-supporting food webs, promoting biodiversity, and helping up to 95% of flowering plants reproduce. However, these types of benefits are much harder to give a monetary value to.

As public awareness has grown, many garden centres have been quick to hop on the bandwagon. Rows of brightly coloured, flowering plants proudly labelled “pollinator friendly” dominate store displays. But here's the catch: just because a plant is labelled “pollinator-friendly”, it does not mean it is. Many of these plants have been sprayed with harm-

ful insecticides. One of the most concerning types are neonicotinoids, neurotoxins which disrupt insect nervous systems, and often lead to the death of beneficial pollinators such as bees. While many neonicotinoids are banned for the use on food crops in the EU, loopholes remain for garden plants. Regulations are much less strict for greenhouse-grown ornamental plants. In addition, many plants may have been treated with insecticides prior to being imported into Ireland, meaning harmful residues may still remain. Basically, if the label does not explicitly say it is ‘pesticide free’, assume it's not.

Big, beautiful exotic flowers may look perfect for pollinators, but in reality, native plants usually outperform exotics when it comes to attracting and

supporting pollinators. This is because native plants and local pollinators have coevolved over thousands of years to be specialised for each other. Worse still, some of these plants are invasive species which outcompete native flora, reducing the available native plants for pollinators.

Good news: you do not need a big budget or an expansive garden to help pollinators. It doesn’t matter if all you have is a window box, you can make a difference.

Choose native plants which have not been treated with insecticides. Some common native wildflowers include daffodils, bluebells, and even foxgloves.

Many of these native plants are FREE. Seeds and cuttings can be shared among neighbours or found growing in the wild. Other plants will appear in your garden all by themselves, including many so-called ‘weeds’ like dandelions, so do not be so quick to weed.

Pesticide-free plants genuinely good for pollinators will often already have hungry customers so look for signs of insect life. Read the fine print. Remember, if it does not say it is pesticide-free, assume it's not.

” Biodiversity should be both the goal and the method.”

There are many different species of pollinators which vary in size, shape, foraging and habitat preferences. They also feed at different times of the day and the year. This means to achieve biodiversity in pollinators, we need to strive for biodiversity in vegetation.

Planting for pollinators may seem daunting, especially with so much misinformation going around, but there are also plenty of reputable sources too. Once you know what to look for, it is much easier to make a big difference to save our pollinators.

Statistics taken from the National Biodiversity Data Centre's ” All Ireland Pollinator Plan ” , and the EU Pollinators Initiative.

KAVIN AADITHIYAN

How can labs become more sustainable? We spoke with Dumitro Anton, Trinity’s Green Labs Officer, about the rollout of the Green Lab Certification Programme and what it means for researchers across campus. Edited highlights from our interview follow.

Q: How did Green Labs come about?

So, it started as a student-led initiative. Around 2019, a bunch of undergraduates, PhDs, and post docs got together and made a small working group. They set in process the Green Labs certification, starting with labs in the Institute of Neuroscience. But as students and researchers tend to graduate or move on, it sort of petered out.

In 2021, when Trinity hired Jane Hackett as Sustainability Manager, it became a priority again. The sustainability team developed a sustainability strategy followed by an action plan, leading to the creation of the position of Green Labs Officer to oversee the development of the programme.

Q: What is the aim of the programme?

The aim of the programme is to bring about behavioural change in labs impacting sustainability. Things such as lighting, waste segregation, water consumption, intensity of equipment use, mode of transport taken by researchers, and so on - these are some of the areas where we try to effect change.

Q: What does the process entail? What role do you play?

The Certification is awarded by My Green Lab (MGL), an external organisation. My role in the process is to bring awareness, help labs enrol, and guide them through the process. But the certification, the platform that it’s done on, all that is taken care of by MGL.

The process has changed a bit over the years. Earlier, it used to be primarily survey based, but recently My Green Lab 2.0 features an online platform which allows labs to better manage their progress and have more control over the certification.

Q: How do you approach labs about this, or do they approach you themselves?

So the biggest challenge of my job so far is how we reach out to labs. But to take a step back, it’s also tricky to classify what a lab is. It sounds ridiculous when you think about it, but in a research setting, a single room might be shared by multiple Principal Investigators (PIs), so then you can’t call that one lab. We decided that for research groups, a lab is its PI and the group. And for teaching labs, it’s the teaching space.

The next step is onboarding. It’s not a lot of work, but it requires commitment from someone in the team to go through with the process, which would be about an hour or two a week over the course of six months. When we started, there was a lot of enthusiasm and I think we’re still on an upward trajectory of interest, but I feel like it’s starting to plateau. And to be honest, it’s hard to tell if the plateau is because of a lack of interest or of knowledge. My guess is that it’s somewhere in the middle. For the ones that are aware and haven’t joined, we will have to engage with them about the benefits. But the college has committed to the process, so it’s a question of how we get everyone on board.

tified labs and funding secured for 37 more. We’re now at 45 certified labs, with another 100 or so in the process. In the last few months, I've secured funding for 50 more labs, of which we have about 25 slots left. So, if you're in a lab in Trinity and want to get certified, you can reach out to the Sustainability Office or to Green Labs, and we can assess for suitability and help get your lab certified.

Q: That brings me to my next questionwhat do labs gain from this?

A sustainable lab operates more efficiently through reduced energy consumption, water use, and waste generation, resulting in lower bills. But also as important is that sustainability is becoming a key criterion in research grants. Funding bodies such as Welcome are already requiring sustainability certification for applicants.

This signals a shift in how research is evaluated – not just on scientific merit, but also on environmental responsibility. Labs that are certified demonstrate a proactive commitment to sustainability, which can strengthen their position in competitive grant applications.

Q: What has progress been like?

When I started in 2024, there were about 20 cer-

Q: How do you collect data in terms of the savings that labs are able to achieve?

That’s actually one of our ongoing challenges, but we’ve made some meaningful progress. A key initiative is the TTMI project, which focuses on the energy consumption of cold storage units, a rather energy-intensive component in labs. Led by PI Adriele Prina-Melo and the TTMI Green Labs team, it explores how sustainable lab practices can reduce energy use in these units. We’ve also looked at fume hoods, where even small things like closing the sash when not in use can lead to measurable energy savings. However, collecting robust data across labs remains difficult. Many labs are shared spaces with multiple research groups, each operating differently. Shared resources like waste bins and water lines further complicate data collection, as usage isn’t always tracked at the group level.

Q: Would it make sense to collect data from a building perspective?

It does make sense, and that's the easiest way to do it but it doesn't actually tell a lot. For example, we can compare the energy use of buildings against previous years. The problem is that not all labs in them might be certified and so it’s difficult to measure the certification’s impact. And energy consumption might reduce or increase purely because the number of people using it has changed. Despite these challenges, we’re committed to improving data transparency and have made progress in identifying key metrics and done pilot projects. Ultimately, having reliable data is essential not just for demonstrating impact, but also for informing future sustainability strategies.

Q: Finally, where do you see the programme in the future?

Our long-term goal is to have all Trinity labs Green Lab certified. Right now, our primary focus is on wet labs, but we’re expanding our scope to include digital sustainability, ones that work exclusively with data and computing. I’m currently developing a digital sustainability certification, which may be delivered in-house through the Green Labs office.

While we focus heavily on behaviour change, infrastructure also plays a critical role. That part is largely managed by Estates and Facilities, particularly through the Carbon Reduction Manager, but we collaborate closely to ensure our efforts are aligned. Looking ahead, we want to embed sustainability into the culture of research by integrating Green Lab practices into academic curricula. We’re exploring the development of a 5 credit module that PhD and postgraduate students can take, helping them integrate sustainability into their research from the start. There’s a wealth of relevant information out there, and we want to make it accessible and actionable.

I also hope we maintain the momentum we’ve built. We’ve got the early adopters on board, and now the challenge is to bring everyone else along. But that’s the real work, creating a culture shift across the research community. And that’s exactly what I’m here to do.

CHERIE NICOLE SALO

If you asked an ecologist, a biologist, or even the average person on the street whether humans are a part of nature, most would likely reply: “Technically, yes. Humans are animals, animals are a part of nature.” But does this understanding truly translate into the way we study and engage with ecology?

Anthropocentrism, defined by Dr. David Keller in his book Environmental Ethics: The Big Questions, as the belief that “human beings, and human beings only, are of intrinsic value… and that non-human nature is valuable for human purposes,” has long shaped

Western attitudes toward the environment. One example of these values in practice, even if not consciously, is the terminology utilised in restoration ecology. Terms such as “intervention,” “interference,” and “disruption” are often used to describe human activity. Although ecologists may consciously agree that we, as humans and animals, are a part of nature, such terminology more so likens humans to be an intrusion upon her, and a disruption to her natural processes. Similarly, the idea that ecosystems are best “left alone” reinforces the notion that nature exists separately from us. Yet it is easy to understand

Industrial exploitation of natural resources has made humanity’s relationship with the environment difficult to view positively. Though ecologists and corporations often clash, both tend to share the same underlying belief that humans and nature are separate. While their goals may differ—protecting the environment to maintain ecosystem services versus exploiting it for economic gain—the overall belief that some kind of boundary exists between humans and nature is shared. This is, of course, a generalisation of western environmental philosophy (which can hardly be described as a monolith), but it is not difficult to understand why such a generalisation exists. Human populations worldwide have long become disconnected from the wild, and emphasis on maintaining a symbiotic and constant relationship with the natural environment has been lost in many cultures. American historian Lynn White Jr, in The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis, attributed this dualism between humans and nature to Christianity. His interpretation provoked controversy, yet he made a broader observation: the loss of animism. In antiquity, every tree or stream was thought to possess a genius loci (guardian spirit). Before cutting a tree, one first sought to appease its spirit.

It has been argued that dualism allows for apathy towards and exploitation of the environment. This logic largely applies to members of the public unaware of ecosystem services, as well as industrial businesses whose apathy stems from prioritising economic gain.

“In contrast, the assigning of spiritual identities to non-human organisms—seen in past European paganism as well as contemporary indigenous cultures—means decisions to manipulate natural environments are done with careful consideration and respect.“

Thus, ecosystem functions are maintained regardless of whether the individual’s goal was environmental stewardship or self-preservation from offended spirits. While animism faded in many western civilisations, its echoes remain, and holistic worldviews have continued to re-emerge in modern environmental thought.

A major turning point came with ecologist Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac. Leopold wrote: “when we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.”

His concept of the Land Ethic — the idea that soils, waters, plants, animals, and humans are all members of one moral community— helped define the philosophy of ecocentrism. Ecocentrism values the health of the entire ecosystem, granting intrinsic worth to all its living and non-living components.

Yet ecocentric values are hardly new. Many Indigenous and non-Western cultures have long upheld similar beliefs. The M āori of New Zealand, for example, consider features of the land such as rivers and forests to be living ancestors with their own personhood. In Japanese Shintoism, 神 (kami, gods/spirits) inhabit all living and non-living things, from crows

and foxes to trees and rocks. Several Native American traditions revolve around reciprocity, specifically balancing what is taken from and given to nature to maintain kinship. Each worldview embeds respect for the non-human world within spiritual and moral frameworks.

If anthropocentrism enables exploitation and ecocentrism fosters respect, could embracing ecocentrism solve the environmental crisis?

Not entirely. Ecocentrism, too, has its critics. Some may define the philosophy as one which promotes equal intrinsic value of all components of an ecosystem (thus, humans would be equally as important as all other members of a community), others define it as prioritising the health of the wider ecosystem over humanity. From this argument stems concerns of misanthropy, as well as infringement on human rights under the guise of conservation.

Examples of conservation occurring in tandem with social injustice has already been seen numerous times throughout history. One such example was the forced displacement of Native Americans to establish U.S. national parks, like Yellowstone, throughout the 19th century. This displacement contributed to the loss of treaty rights for hunting, cultural erasure, forced assimilation, and served the Europeans’ broader goal of ethnic cleansing.