WHAT IS YOUR STORY?

WHAT IS YOUR STORY?

Welcome to the very first edition of Legacy Literature magazine. Since 2015, my team and I have been quietly helping some of the country’s most prominent individuals preserve their life stories through exquisitely written biographies. Our clients have spanned the spectrum, from a major network television executive who oversaw the Super Bowl, to an Italian immigrant who came to work as an engineer on the Space Race, to a serial entrepreneur who founded a dog food company in his early seventies and sold some years later for $8.1billion. (It’s never too late!)

As fascinating as these books are, not a single one of them can be found on Amazon, in book stores, or in your local library. They were written strictly for posterity, destined for

future generations of their family to convey life lessons, guiding principles and collective wisdom. And so it is that these riveting, often inspiring stories have remained out of the public eye—until now.

A select group of our clients have given their blessing for us to share glimpses of their remarkable lives with you through chapters of their books. Some of their stories bring us into the world’s most historic moments. Others reveal the seeds of inspiration behind their remarkable success. These exclusive excerpts from their private biographies make up the bulk of what you are about to read in this inaugural issue of Legacy Literature.

Along with these feature stories, we breakdown how and why we write these books. We tell you about the genesis

of Legacy Literature and what makes our service the gold standard in private biography. We also introduce you to some of the talented service providers we’ve met while working with this very discerning caliber of clientele, be they wealth advisors, real estate professionals, even private art curators.

Just like our books, not everyone can get their hands on this magazine. There’s a

specific reason why this has landed on your doorstep. Something about your story—how you came up, what drove you, why you ended up here, who you met along the way—will make these stories resonate particularly with you. Perhaps after you read some of these stories you might ask yourself: How will I be remembered?

Robert Cocuzzo Founder & Chief Biographer

WRITTEN BY ROBERT COCUZZO

How Chad Gifford and his family survived one of the worst maritime disasters in American History

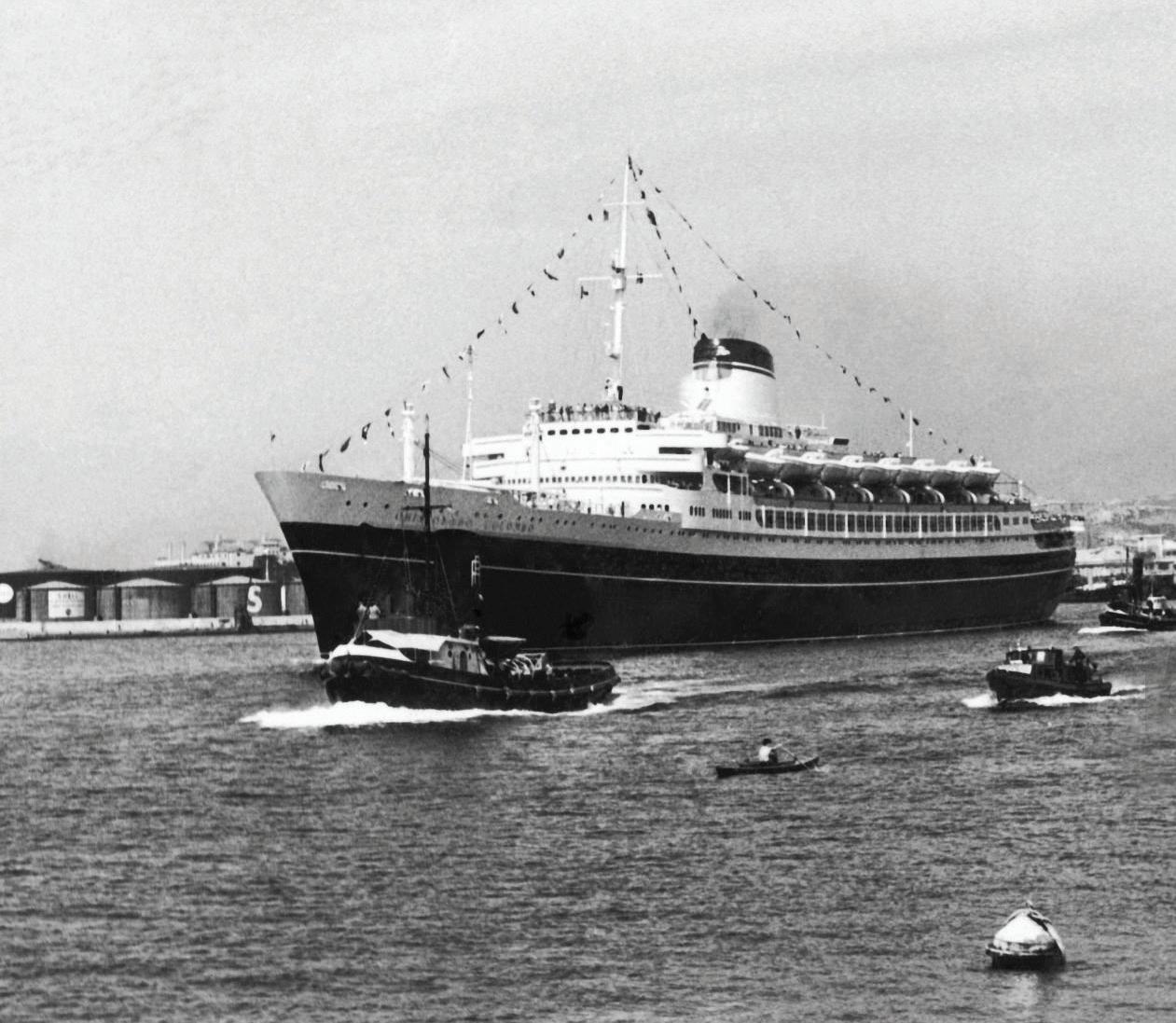

There was simply nothing like her in all the oceans of the world. If the Queen Mary represented the old guard of ocean liners, the Andrea Doria stood for its big, bold, beautiful future. Named after one of Italy’s most celebrated mariners, a ruthless tactician of the sea who famously fought off pirates in protecting Genoa as the world’s maritime superpower in the fourteenth century, the Andrea Doria became the pride of post–World War II Italy. Emerging from the long, dark shadow cast by Mussolini, the 697-foot, 29,100-ton Doria reclaimed the country’s historic identity as master of the sea—and did so in incomparable style.

When its interiors were first revealed, the Andrea Doria’s designs had not been seen before or since. Instead of commissioning a single designer to create a unified look and feel, contests were held in which Italian master artists and designers submitted proposals for rooms and salons throughout the ship. The result was an abrupt jettisoning of the traditional aesthetic of the Queen Marys of the sea for a contemporary reimagining of an ocean liner. The Andrea Doria was a floating tribute to all that was good and beautiful in Italy. Rooms were replete with nods to Renaissance masters. These classic paintings, sculptures, and murals were juxtaposed by art deco interior design and minimalist furniture crafted by the likes of Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen.

Contending with the rise of aviation that cut the transatlantic voyage down from days to mere hours, the Andrea Doria leaned into the philosophy that the journey was more important than the destination. To this end, all classes of the ship, from first to the tourist—traditionally referred to as “steerage” or “third class”— offered passengers luxuries such as their own swimming pools. Amenities abounded, but nowhere more than in first class. Stretching over seven decks, first class offered swanky bars like the Belvedere Lounge, reading rooms, game rooms, gymnasiums, and salons. The glamorous mystique of the Doria was enhanced by Hollywood passengers like Cary Grant, Orson Welles, and Joan Crawford. Writers Tennessee Williams and John Steinbeck also made the voyage aboard the Doria.

The glamorous mystique of the Doriawas enhanced by Hollywood passengers like Cary Grant, Orson Welles, and Joan Crawford.

35,000 horsepower. With the tragedy of Titanic still looming large in the collective imaginations of passengers—Walter Lord’s international bestseller A Night to Remember was published in 1955—the Doria was divided into eleven watertight compartments. In the unlikely event of a collision, two of these compartments could fill completely with water and the Doria would have no trouble staying afloat. In fact, while most vessels were constructed to be able to withstand seven degrees of list—the Doria could theoretically manage fifteen.

Little if any of this information was swirling in Chad’s thirteen-year-old mind as he entered the Andrea Doria by way of the First Class Foyer on the afternoon of July 18, 1956. He and his family were boarding the Doria at her second stop in Naples since leaving Genoa. This would be her 101st crossing of the Atlantic Westside Pier in Manhattan.

Behind the glitz and glamor was a steadfast vessel equipped with all the advancements in modern maritime technology. The bridge benefited from the latest radar, sonar, radio, and navigational devices. Two giant bronze propellers spanning sixteen feet each powered the liner ahead by way of steam turbines packing

While Priscilla preferred the traditional and measured aesthetic of the Queen Mary, Bud was enthralled by the exotic aura of this exciting new vessel and was willing to fork over a sum of around $700 for two first class cabins. Bambi would stay with her parents in cabin 98, while the boys would share cabin 96, both on the starboard side of the vessel. Meanwhile, their Volkswagen bus joined nine other vehicles—including a Rolls-Royce and a state-of-the-art concept car developed in Turin that was being delivered for the Chrysler Corporation—in the ship’s air-

conditioned garage on B-deck. Making his way down the long, oval-shaped first-class foyer, Chad marveled at the space-age design with uplighting illuminating the ceiling of the long hallway. To the right, the walls were decorated with ornate murals reminiscent of the ones they toured in Florence. They made their way up a grand staircase and onto the starboard side, where they found their rooms. Jock claimed the upper bunk, while Chad took the lower bunk and Dun his own twin bed. With their luggage stowed, they set off to explore the ship.

The Andrea Doria was a city unto itself, offering passengers every amenity imaginable. There was a chapel that held daily services, a fully functioning hospital staffed with doctors and nurses, a barber shop and a hair salon, a spa with steam baths and tanning beds, a gym with stationary bikes and rowing machines, a kennel for passengers’ pets, multiple bars,

libraries, lounges, and plenty of open deck space to soak in the summer sun on the long, leisurely ride to the States. Chad found his way on to the promenade deck just as the Doria’s whistle sounded and a refined voice came over the intercom announcing the ship’s departure. With that, the Doria vibrated awake as the steam engine began turning those giant props through the black water below until a white wake began frothing behind the ship.

Evening soon came, and the Giffords dressed for dinner. As was indicated at the bottom of the daily itinerary that was slipped under their cabin doors, the dress code was formal.

Clarence donned a black bow tie and black tuxedo, while Priscilla wore a flower gown, white stockings, white shoes, and a light shawl. The Gifford boys all wore matching tuxedos with black bow ties, white pocket squares, and cummerbunds. Meanwhile,

Bambi, with her bob haircut and bangs, wore a white dress that a little girl might wear for her first Holy Communion, along with bunched-up white socks and black shoes. With Clarence toting a pipe and Priscilla holding her Nantucket lightship basket, they were the picture of genteel refinement as they entered the first-class dining room.

For the ship’s overall grandiosity, the dining room was noticeably restrained, with low ceilings and tightly arranged circular tables dressed in white linens. Bud found their assigned seating and they all sat for the meal. Priscilla studied the elegant china, the plates’ rims adorned with hand-painted red rope around the ship’s logo. While white-coated waiters fluttered from table to table, a crew of sixty cooks, sauciers, bakers, butchers, and ice sculptures were fastidiously at work in the stainless-steel commercial kitchen preparing every imaginable

cut of meat, filets of fish, roasted and baked vegetables, pastries, cakes, souffles, and ice cream. Their waiter swooped in and delivered an assortment of hors d’oeuvres of smoked ham, olives and mushrooms, caviar, and shrimp cocktail.

After finishing dinner, Chad and his siblings filed into the adjoining lounge, where a wall displayed mechanical horse races that the passengers could bet on. Each of the Gifford children fished out a few dollars of their allowance to make a wager. “All right, all bets in,” the clerk announced. “The race is about to begin.” He then started spinning a wheel that brought the horses to life, galloping across the wood panel wall. Everyone hooted and hollered, trying to coax their stead to the finish. When the dust settled, it wasn’t Chad in the winner’s circle but Bambi, who earned herself nine dollars and a fine Italian leather purse.

As the night wore on, Dun broke away from Chad and the rest of his siblings and made for the first-class ballroom.

Purple and silver couches lined the perimeter of the dimly lit

dance floor, where he noticed an attractive brunette standing alone and went over to speak with her. Sixteen-year-old Barbara Bliss had boarded the Andrea Doria along with her mother and stepfather in Genoa. Unbeknownst to Dun, Bliss’s

family was very likely the wealthiest on board. Barbara’s mother, also named Barbara, was the heir to a department store fortune. But as far as seventeenyear-old Dun was concerned, young Barbara was just an eligible girl for him to romance over the coming days. Meanwhile, back at the lounge, Chad studied the horses being returned to their stables on the electronic board. He was committed to winning the race the following night.

The next morning, July 19, Chad rose to the sounding of Andrea Doria’s whistle, followed by an announcement that all passengers should report to what was known as their muster stations, a designated meeting point for emergencies. “Bring your life jackets found in your cabins,” the announcement concluded. Chad, Jock, and Dun retrieved their bulky orange life jackets and made their way to their muster station along with their parents and Bambi.

The Andrea Doria was equipped with sixteen aluminum lifeboats, eight on the starboard, eight on the port. The boats ranged in capacity, from two motorized boats that could carry

No one actually believed that this sturdy ship would ever need to lower her lifeboats.

seventy-eight passengers to twelve Fleming lever boats that could hold nearly two hundred. Despite the importance of the drill, and despite the fact that this would be the only emergency drill that the Andrea Doria would conduct for the duration of the journey, neither the passengers nor the crew, for that matter, appeared to take the operation all that seriously.

Some passengers sipped coffee while they dragged their life jackets behind them as a child would a stuffed animal. In some muster stations, crew members did not even bother to show up to provide instructions. The drill seemed more like a formality, a charade, a box to check. No one actually believed that this sturdy ship would ever need to lower her lifeboats.

The following day, Chad stood out on the railing under a pristine blue sky as he watched land come back into view. The Andrea Doria was making its final stop at the Rock of Gibraltar

before heading through the Strait of Gibraltar and continuing on to the United States. As giant anchors splashed down in the water below, Chad spotted a flotilla of smaller boats motoring toward them. Along with tenders ferrying the last of the Doria’s passengers aboard, there were rickety merchant vessels bringing mail and other goods for the ship. Then more smaller boats appeared and began buzzing around the hull, their pilots calling up to passengers and hawking watches, clothing, and perfume. After all the new passengers were safely on board and the Doria’s crew finished hauling up the last of the supplies and mail, the whistle sounded again and the engine thundered alive.

Returning to his cabin, Chad noticed a boy his age checking into a room down the hall.

Thirteen-year-old Peter Thieriot was coming aboard the Andrea Doria with his mother, Frances,

and his father, Ferdinand, after an extended stay in Europe. A Princeton graduate, Peter’s father was the heir to the San Francisco Chronicle, the newspaper his greatgrandfather founded. Despite his pedigree, young Peter had just been put to work at a family friends’ farm in Somerset, England, where, among other skills, he’d learned to roll cigars. Peter had then joined his parents in touring Europe, a trip that culminated in watching the running of the bulls in Pamplona, Spain. The Thieirots had originally intended to fly back to the United States, but after the harrowing news broke of two passenger planes crashing into each other in midair above the Grand Canyon, Frances insisted to her husband that they steam across the Atlantic instead. Ferdinand booked them on the Andrea Doria

Coming aboard, Peter checked into Foyer Deck Cabin number 186, while his parents stayed in what was known as the

Zodiac Suite, fifty feet further to the stern in number 180. Ferdinand had originally tried to reserve one of the deluxe suites that would have allowed the entire family of three to bunk together but was disappointed to learn that they had already been taken. Happy to have a room of his own, Peter then went off to explore the rest of the boat, where he eventually bumped into Chad.

The two boys became quick friends. They tagged along behind one of the Doria’s staff, who was giving a tour of the ship, before breaking off and sneaking into the engine room, which was less a room and more like a castle of mechanical parts.

As Chad and Peter were getting to know each other as well as the rest of the ship, the Andrea Doria departed from the Rock of Gibraltar and began its journey to Manhattan. On the bridge, Captain Piero Calamai stared out to the sea, extending forever

under a cloudless sky. With 1,134 passengers and another 600 crew under his watch, the captain steered his ship along the Southern Route. Passing by the Azores, the Southern Route typically offered fair seas and sunny conditions for passengers to fully enjoy the summer temperatures.

With a Roman nose and steely eyes set beneath his white captain’s cap, Calamai commanded respect from crew and passengers alike. He possessed one of the finest records in Italian maritime history, having commanded dozens of vessels and been highly decorated in both world wars. Slow to anger—his crew never witnessed him raise his voice— Calamai also shunned the fanfare normally associated with his command and only reluctantly participated in glad-handing A-list passengers who clamored for him to sit at their table for dinner. The captain spent most of

his time on the bridge, steadfastly navigating the Andrea Doria across the Atlantic as fast and as safely as possible. This 101st crossing was to be his final voyage before retiring after a lifetime at sea.

In first class, Chad continued to relish the fun and freedoms of life on this luxury liner. He watched as his new friend, Peter, shot skeet off the top deck. Afternoons were spent swimming in the pool, splashing into the water by way of a slide. Each day concluded in the first-class lounge cheering on his mechanical horse and indulging in the lawlessness of international waters, where a thirteen-year-old could gamble.

After the Doria reached the Azores, some 1,100 nautical miles from the Rock of Gibraltar, the normally calm seas of the Southern Route began to churn. Soon the Doria was pitching and rolling between waves and chop. he crew issued Dramamine

along with other concoctions, but still droves of passengers retreated to their cabins with seasickness. A family of sailors, none of the Gifford boys were troubled by the rough seas and instead enjoyed having the run of the ship as a third of their fellow passengers prayed for calmer seas in their bunks.

Their prayers were finally answered by July 24, when the ocean mercilessly settled. However, the rough seas were soon replaced by an impenetrably thick blanket of fog. On the bridge, Calamai and his crew kept a sharp eye on their two radars in search of other ships in their path. As with all captains, Calami needed to meet a strict deadline and only slightly reduced the Doria’s speed as she continued to cut through the murk.

On the evening of July 25, Chad again donned a shirt and tie along with his brothers and father and made for the first-class dining room for the much talked about Captain’s Dinner, the final meal before docking in New York City the following day. As they settled into their assigned seats, Chad scanned the room, like everyone else, waiting for the illustrious captain to enter and grace them with his

presence. “I’m sorry,” they overheard one of the waiters say after a few minutes, “but the captain will not be joining us tonight. He is needed on the bridge.” In the fog, Calamai had not left his post in more than a day, and now, with the end of the voyage in sight, at least theoretically, the captain was committed to remaining at the helm until they were safely docked in Manhattan.

Nevertheless, the Doria’s kitchen did not hold back for the final dinner of the voyage.

Clarence and Priscilla sipped melon cocktails in marsala wine and the kids cold Coca-Colas, as the waiters delivered appetizers of Parma ham, foie gras, stuffed olives, and Waldorf salad. Entrees included Maine salmon served in a Jell-o stock, roasted beef accompanied by french fries and bacon, and asparagus with hollandaise sauce. Some diners perused the well-stocked cold buffet with its roast veal, venison, roasted lamb with mint sauce, and chicken-and-celery salad. Chad and his brothers and sister were pretty well stuffed when the waiters emerged from the kitchen with generous slices of what they described as “a special farewell cake,” a Baked Alaska.

After finishing their desserts, the Giffords continued to the lounge, where a line of chairs were set up to watch the mechanical horse races. Clarence, Priscilla, and Dun ordered crème de menthe cocktails while Chad, Jock, and Bambi

each sipped another Coca-Cola. When the races concluded, a Bingo match ensued, which Bambi won. “She’s always lucky,” Chad scoffed. Meanwhile, Dun was making a match with Barbara Bliss and her friend Nancy Coleman, whom he sat between watching the games.

Wearing a tweed jacket and a red tie, Dun had successfully sweet-talked Barbara. The two were sorry that their journey on the Doria was coming to an end. At ten thirty, all the games in the lounge concluded. Clarence and Priscilla went out to the deck for a walk before bed but were quickly turned around by the thick fog. While the parents were outside, Chad, Jock, and Bambi discovered a table that held fancy, colorful drink stirrers, all customized with the Andrea Doria’s logo. They each pocketed handfuls as keepsakes just as their parents wrangled them to head back to their bunks to pack and retire for the night. Dun stayed in the lounge with Barbara and Nancy.

Returning to their

cabin on the starboard side, Chad and Jock dumped their swizzle sticks on their beds like pirate booty and got to packing. The crew indicated that all passengers’ luggage needed to be outside their doors by midnight. Jock climbed into his top bunk in his underwear to clear the items from the shelf up while Chad began yanking off his necktie. In the morning they’d land in New York and then it would be back to Nantucket before returning to St. George’s. This had been a perfect vacation, a trip they would never forget. Chad had just freed his tie from around his collar when BOOM!

The sound of it was ungodly. Jock was thrown off the top bunk onto the floor. Chad stumbled to his knees. They got to their feet and burst out of their cabin. The hallway was filled with smoke. “It must have been an explosion,” Jock shouted to his brother. “Maybe the boiler.” A second later, their father emerged from his cabin. His normally measured demeanor appeared shaken. Through the smoke, he spotted his sons. “Go get your life jackets,” he shouted to them.

Back in their room, Chad located his life jacket while Jock hastily threaded his naked legs into a pair of pants. Chad scanned the room, thinking about whether he should grab anything else. He thought about taking his wrist watch, but snatched a handful of the Andrea Doria stirrers instead. Meanwhile, Bud was mobilizing Priscilla and Bambi in their stateroom. Moments earlier, he had received a glass of milk to relieve the burning in his stomach due to an ulcer. Now that glass was shattered to pieces on the floor. All three of them had been thrown to the carpet by the blast. Priscilla slipped Bambi’s dress back over her head and then grabbed her Nantucket lightship basket before they returned to the smoky hallway.

The normally soft, elegant light in the hallway had been replaced by stark hazard lights. The power of the ship had failed and was running off the generator. The smoke smelled acrid of blown electricity panels. Chad and his

family climbed over the suitcases that had been placed outside passenger doors as they made their way down the hallway. But it was not just the suitcases scattered about that made the walk difficult; the boat was now tilting drastically to the starboard side.

Chad grabbed the railing and hoisted himself up the slanted stairs. Passengers above and below him kept stumbling on the awkward steps and dropping personal effects they had brought with them, along with their life jackets. Priscilla fumbled her Nantucket lightship basket, which tumbled to the bottom of the steps. “Mom, your basket!” Bambi shouted.

“Just leave it,” Priscilla said. “We have to go.”

“No, we can’t leave it!”

“We’ll get it when we come back to our rooms.”

“No,” the nine-year-old insisted before turning around and climbing back up the stairs and retrieving it.

After reclaiming her bag, Priscilla locked eyes with Betsy Drake, the wife of actor Cary

Go get your life jackets! “

”

Grant, who had also dropped her overnight bag down the stairs, except hers was full of priceless jewelry given to her by her Hollywood husband. “I wish I had a daughter to get my bag,” she lamented.

Chad and his family reunited with Dun at the top of the Grand Staircase. Minutes earlier, Dun was sitting on a sofa in the First Class Ballroom between Barbara Bliss and Nancy Coleman. The three

We’ve hit another ship! “ ”

of them had left the lounge in hopes of dancing in the ballroom, but the band had already packed up their instruments when they arrived. Instead, Dun pulled out an address book to take down the two coeds’ contact information. He had been gazing out the starboard windows when an unusual sight caught his attention.

A glimmer of light shown through the tall starboard-side windows. Dun’s immediate thought was that the beam belonged to a lighthouse. “A lighthouse in the middle of the ocean?” he muttered to himself. The words had barely left his lips when BOOM! Bottles smashed to the floor. He and the two girls were thrown onto a coffee table. The room went black for a moment, then the emergency lights flickered on. Dun looked down to his hands and saw that he was bleeding. “Oh my God!” Barbara yelled. “We’ve run aground!”

“To hell we have!” Dun said. “We’ve hit another ship!”

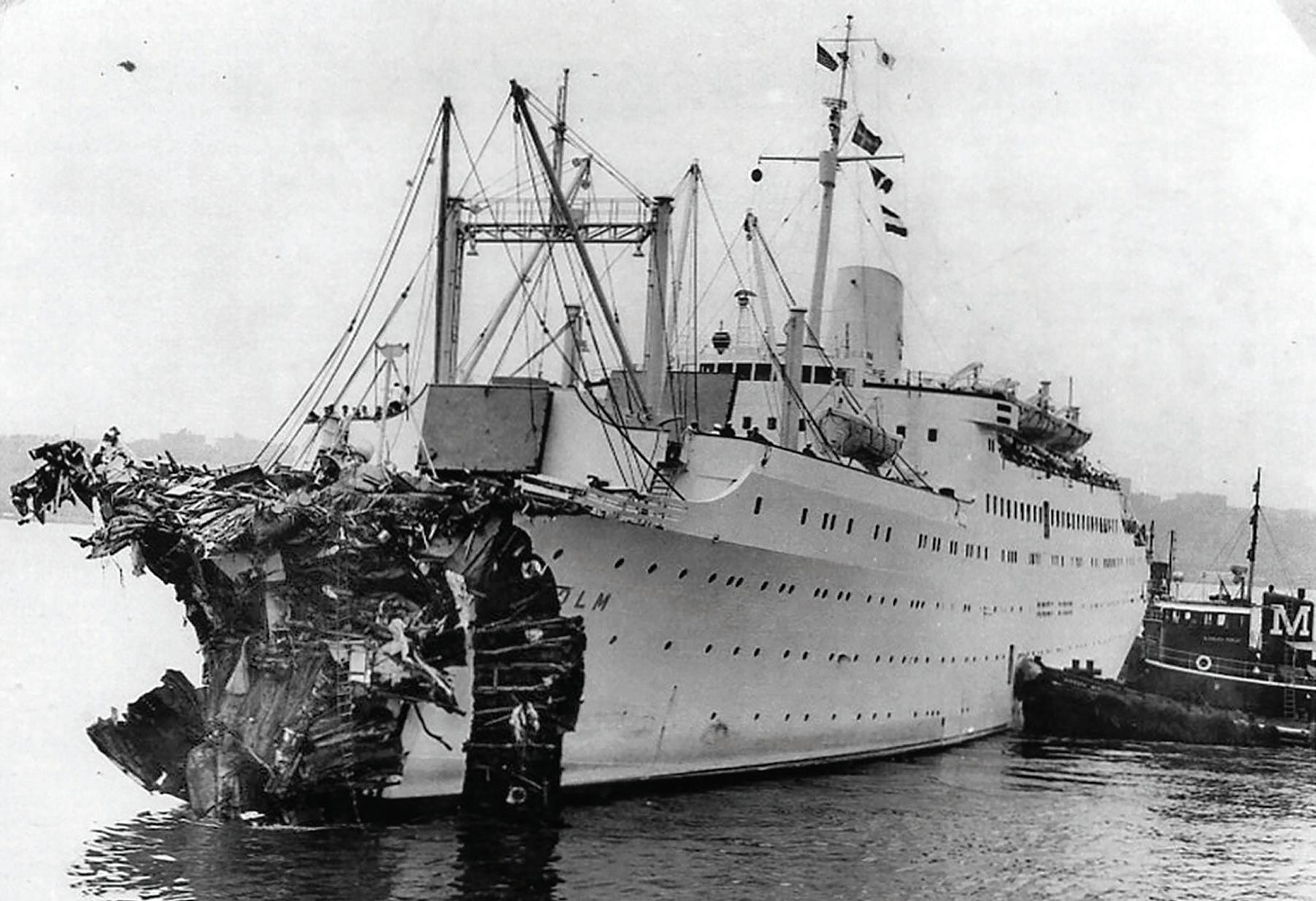

Dun wasn’t the only one who spotted the Stockholm before it crashed violently into the starboard side of the Andrea Doria at 11:11 on the night of July 25. Up on the bridge, Captain Calamai and his crew had been tracking the 524-foot liner for the better part of an hour. At first, Calamai assumed the blip on his two radars— which gave no indication of the size of the ship—was nothing more than a fishing

vessel cruising the waters around Nantucket. Part of this supposition was based on the fact that Stockholm was steaming in the opposite direction in a lane designated by the North American Track Agreement for westbound traffic on the Southern Route.

Unbeknownst to Calamai, the captain of the Stockholm—a bullish Massachusetts native named Harry Gunnar Nordenson—had defied that agreement in an effort to expedite his journey from New York City’s Pier 97 to Gothenburg, Sweden. At ten p.m. under a still, clear sky, Nordenson turned over command of Stockholm to his twenty-six-year-old third officer, Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen, who had never commanded the bridge on his own and never navigated in fog. Nordenson gave his third officer strict instructions to wake him from his cabin if he encountered any other ships, but even after the Andrea Doria blipped on the Stockholm’s radar, Carstens-Johannsen did not rouse the captain.

Instead, he kept steaming full-speed ahead at 18.5 knots into a fog bank while also monitoring the radar, which he had never operated before. To make matters worse, at ten thirty, CarstensJohannsen put Peder Larsen—one of the three men with him on the bridge—in charge of steering the ship, despite the fact that this was Larsen’s very first voyage on the Stockholm. Blinded in the fog, struggling

with the radar, and unfamiliar with the controls, Larsen began taking an erratic track off course.

On the Andrea Doria, Calamai continued to watch the progress of the mysterious vessel on his radar. The two ships were still some seven miles away from each other, but with each passing mile, the time to act became shorter. Based on their current trajectory and speed, Calamai’s crew estimated that the oncoming vessel would pass them about a mile from their starboard. For safety’s sake, Calamai ordered the Doria steer 4 degrees to the port to perform a port-to-port passing, furthering that distance between them.

As the two ships came within a couple of miles of each other, Calamai and his crew scoped the fog with binoculars in search of the lights of the oncoming vessel. When Stockholm’s lights first came into view like ghostly apparitions in the fog, the liner appeared to be steaming directly forward parallel to their course, but then they saw the red port light indicating that the ship was turning toward them. “She is coming right at us!” yelled one of the crewmen on the bridge. Calamai ordered the helm to turn hard to port at its current speed of 21.85 knots in an attempt to turn away and outrun the oncoming vessel.

But it was too late.

Stockholm’s bow slammed into the starboard side of the Andrea Doria just below the bridge like a battering ram. Designed to crush ice during arctic voyages, the bow was made of reinforced steel and jutted out from the water severely at nearly 45 degrees. Still moving full speed ahead, Stockholm dealt a mortal blow to Andrea Doria. Though the watertight compartments had already been sealed while the Doria steamed through the fog, she immediately began to list after the collision. Water gushed into the gaping wound on her starboard side from the first-class upper deck all the way down to the cargo deck and hull. Cabins 42 through 58 on the upper deck were decimated.

Had any multitude of things happened differently—had Calamai sped up, or turned slightly less to port, had Stockholm reduced its speed–the Gifford family, except for Dun, would have most surely been killed by the collision. However, even after Stockholm pulled away from the Doria, the family’s survival, as with

everyone on the ship, still hung in the balance.

After reuniting with his parents and siblings at the top of the staircase, Dun realized he was missing an essential piece of survival gear: his life jacket. “I’m going down to get it,” he told

OK, children, if we have to jump in the water, we will get in acircle and hold hands. “

his father. Dun then scrambled down the slanted stairs against the upcoming traffic until he reached the upper deck. The list of the ship had worsened. Navigating around the luggage splayed all over the hallway under the flickering emergency lights, Dun tried to

quell his fear and slid across the cabin on his stomach to retrieve his life jacket.

Chad and his family reached the promenade deck, where the list of the ship appeared much more severe. Furniture slid down toward the windows on the starboard side. The Giffords climbed up to the high portside of the ship where the windows were blinded by fog and stood until their legs tired and forced them to take a seat in a circle on the ground.

Exchanging glances with Jock, Chad felt excitement coursing through his veins. Oblivious to the carnage below deck, he thought all the chaos was an adventure. And from what he could tell, so did his father. Bud jumped up from their encampment on the deck to caucus with other men. Announcements in Italian were intermittently bellowing from the speakers overhead, but no one appeared to know definitively what had happened.

Contrary to her husband, Priscilla appeared anxious. “Let’s play a game,” she said to Bambi, Jock, and Chad, trying to create

a distraction for her children and, perhaps, for herself. “Let’s name all our favorite places from our trip in Europe. Our favorite hotel. Our favorite dinner . . .” The three children joined in, with Bambi naming Venice as her favorite city. Meanwhile, Dun had returned and found a seat on the deck adjacent to his family, as well as with Barbara and Nancy.

The promenade deck became more and more populated with passengers. A few minutes after Chad and the rest of the first-class passengers arrived, those in the tourist and cabin class appeared up the Grand Staircase. Some were wet, others were bloody or soaked in black oil. The sight of them conveyed the severity of the situation. Apart from Chad’s romps with Peter Thieirot throughout the ship, this was the first time he encountered the passengers from the lower classes of the ship. Huddled in pajamas and life jackets, they were indistinguishable from the other classes. They were all humans gripped with fear.

Minutes ticked into hours as the Giffords waited anxiously

with everyone else for instructions on what to do next. Jock got up from the group and went to the bathroom. He was disgusted with what he witnessed. With all of humanity seemingly clinging to the boat on the Promenade Deck, the once immaculately clean facilities had been overrun with passengers vomiting and defecating out of fear. Shaken by the disorder of it all, Jock returned to his family with an increased anxiety. This wasn’t an adventure after all; they were in the midst of an emergency. A priest came by and muttered a litany of prayers to them in Italian. They did not know it at the time, but they had just been given the last rites. “OK, children,” Priscilla said, “if we have to jump in the water, we will get in a circle and hold hands.” The message was sobering. Bambi began to cry, but not for her own plight. “What is going to happen to all the dogs in the kennel?” she asked her mother. “Please tell me they’re going to be OK.”

“Of course they are going to be OK,” Priscilla reassured her. “The crew will get them.”

Sitting next to Barbara and

Nancy on the deck, Dun tried to buoy everyone’s spirits by breaking out into song, performing his own rendition of “A Little Bit of Luck” from My Fair Lady. “‘The Lord above made man to help his neighbor,’” he sang. “‘No matter where on land or sea or foam. . . the Lord above made man to help his neighbor. But, with a little bit of luck, with a little bit of luck . . . when he come around, you won’t be home.’” Barbara joined him in singing. When the song was complete, Dun leaned over and kissed her on the cheek.

Around one thirty in the morning, word reached the Giffords that women and children

were being loaded into lifeboats. Chad looked up to see angst flash across Priscilla’s face at the news. She clearly did not want to leave her husband on board a sinking vessel, but Bud insisted. Chad got to his feet and followed his family climbing down to the starboard side. The list of the Doria had worsened, and passengers struggled to cling to any fixed items to descend. The teak floor was wet and greasy with oil. The slightest misstep sent passengers

sliding down across the lounge. Chad and his family inched their way to the first-class lounge and then to the Grand Staircase to reach the Boat Deck.

Priscilla When Chad finally arrived at the railing, he was enveloped in darkness. Only spotlights cut through the ominous black. Rope ladders and makeshift Jacob’s ladders hung from the railing down into the darkness below. Chad looked up and shuddered at the

unnerving sight of the Doria’s funnel and mast lording precariously overhead. At any second he could picture the portside folding on top of them and drowning them in the sea.

PriscillaChaos raged at the railing as women and children struggled to make their way down the ladders to the lifeboats. No one appeared to be directing the evacuation; certainly not any members of the Doria’s crew, who had mostly disappeared after initially lowering the ladders. The passengers were on their own. Some leapt into the water, while others fell from the webbing. Babies wrapped in blankets were lowered down like little packages. Dun watched a woman fall from the rope ladder and badly break her arm landing in the lifeboat. One father was climbing over the railing with his four-year-old daughter hanging from his back when another passenger leapt into the water and knocked her off. The little girl fell off her father’s back and slammed her head gruesomely off one of the lifeboats below—ultimately killing her.

Priscilla At the railing, Chad climbed over and gripped the rope ladder. Jock, Bambi, and Priscilla did the same, with Jock helping Bambi down. But Dun refused to go. “I should be staying with the rest of the men,” he insisted to his father. “I should stay with you.”

Bud, who was helping shuttle women and children to the railing, looked sternly into his

eldest son’s eyes. “You’re going,” he said bluntly. “You’re the man of the family now.”

Priscilla Chad clung to the rope ladder, which was wet and oily and swaying in the darkness. When he reached the lifeboat below, he was startled to see that most of its passengers were members of the Andrea Doria crew.

Facing difficulties launching the lifeboats from the Doria’s damaged starboard side, Captain Calamai had ordered each boat be manned by five extra crewmen. However, this wellintentioned command led to many other members of the crew—who were not seamen, but frightened waiters, bartenders, cooks, and bellboys—to swarm the lifeboats, some jumping into the water and needing to be rescued. The first lifeboats to be reached by the Stockholm, which had since turned around to help in the rescue effort, were occupied by hundreds of members of the crew who were still wearing their Andrea Doria uniforms.

Chad sat with his mother on one end of the lifeboat, while Jock and Bambi plunked down on the other. Dun settled in the middle. The water was flat calm and still encased in fog. Chad looked up at the horrifying sight of the Doria cresting over them like a giant wave. He felt an immediate sense of urgency for them to move out of its path, but more and more people continued to climb into the lifeboat. Person after

person, every square inch of the boat was packed, exceeding its fiftyperson capacity by more than 50 percent. As more and more people loaded on and the boat got tighter and tighter, Chad watched the waterline creep up the gunnel. If any more passengers boarded, or if the slightest wave were to come, the lifeboat would be consumed by the sea.

Finally, the crew pushed off the Doria and began rowing carefully over the placid surface. There was nowhere in particular to go but just away from the sinking leviathan. Within twenty feet, the fog enclosed around them completely. They were totally blind. There was no way to tell how close they were from the Andrea Doria, or how far they were from the nearest landmass, which happened to be Nantucket, some forty-five miles to the north. In the fog, the fear intensified. Gentle swells rolled beneath them. The slightest wave would do them in. Then all of a sudden—clarity. Complete clarity. The fog disappeared. Chad looked up to see ILE DE FRANCE in

big, bright letters. Three or four hundred yards away, the whole ship shone brightly, every one of its lights burning full watts like an angel from heaven. Having left New York City earlier that day with nearly 2,000 passengers and crew, the 739-foot Ile de France responded immediately to Andrea Doria’s SOS. Steaming full speed at 22 knots through the fog, the Ile de France’s crew readied their infirmary, lifeboats, and provisions to assist in the rescue, which five other ships had also responded to.

Reaching the Ile de France,

the lifeboat unloaded one by one, careful not to tip the overloaded boat. Chad and his family climbed aboard and were led to an elevator that delivered them to the Promenade Deck. The crew of the Ile de France hurried to them with coffee and doughnuts. Chad and his siblings nibbled at the doughnuts while Priscilla remained stoically quiet. All of a sudden, she was sitting in the kitchen on Nantucket all over again, listening to the radio about the war, worried about her husband’s survival.

“Stay with me, children,” she said. “Don’t go exploring . . . we’re waiting for your father.” While they were waiting, Chad watched his mother accept a cigarette. She smoked it intensely. Then smoked another. And another. It was the first time he had ever witnessed her smoking.

They had no idea what was happening on the Andrea Doria. Had the men been evacuated yet? And if they had, where had Bud ended up? There were now six ships responding to the tragedy. Bud could have ended up on any one of them, leaving his family in suspense as to his safety. Chad looked over to his mother, whose face was unmistakably tense. Suddenly, men started coming aboard from the elevators down the way. “Mom, I’ll go get Dad,” Chad offered. “I’ll bring him back here.”

“You remember where the elevators are?” she asked nervously.

“Yes,” Chad said. “Right over there.”

Priscilla nodded in agreement. Chad sprang to his feet and made his way to the elevator bay. The doors opened and a load of men walked out. Their faces were stricken in a range of emotions; some relieved, some still bewildered. Chad waited to spot his father’s face, but it never came. The elevator doors closed again. Chad waited. The doors opened again, and standing right before him was his father.

“Dad!” Chad yelled out.

“Chad!”

The two embraced briefly, and then Chad looked up to his father. “Come on,” he said. “Mother is just over there.” Chad led him back to the rest of the family. He locked eyes with his mother. The relief in her face was radiant as the Ile de France’s lights piercing through the murk. The Giffords were together again. Chad sat on the deck. He looked at each member of his family’s faces and then out to sea with a whole new sense of mortality. •

Legacy Literature client Chad Gifford is the Chairman Emeritus of Bank of America. Gifford’s family contracted Legacy Literature to document his life for future generations of their family. “Rob has a talent that immediately establishes a sense of trust,” said Gifford.

“This in turn created an openness and willingness to recall all sorts of memories, many that I had long since forgotten. Rob’s research helped guide events that impacted my career. I found that the more we talked the more past events came to life.” Read Gifford’s entire testimonial at legacyliterature.com.

WHAT IS YOUR STORY?