New Nottingham Journal

Illustrations by April Seaworth

VOLUME 1

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF - Andrew Tucker Leavis

ASSOCIATE EDITOR - George Newton

MANAGING EDITOR - Martin Fitzgerald

EVENTS COORDINATOR - Kibrina Davey

PR & MARKETING ASSOCIATE - Hannah Cox

COVER DESIGNER - Jim Brown

EDITORIAL DESIGNER - Karen Constanti

ADVISORY

BOARD

Amy Acre-Hall

Hongwei Bao

Becky Cullen

Jim Leaviss

Hannah Trevarthen

Rory Waterman

Matthew Welton

Robert Weston

Jared Wilson

© 2025 New Nottingham Journal Ltd. All rights reserved.

‘The Stone Dead’ by Alison Moore first appeared in Eastmouth and Other Stories. Copyright © 2022 Salt Publishing. All rights reserved. Reproduced by permission of the author.

The New Nottingham Journal is bound and printed in Cornwall by TJ Books. This journal is printed on paper that has been certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC).

New Nottingham Journal Ltd. - registered in England and Wales 16346485.

The Phoenix and the Sieve

A letter from the editor

It might have escaped your attention, but there’s an uncanny moment in the Italian version of Peppa Pig. In need of escape, the jovial porcine family have booked a holiday to give themselves a fresh start – they opt for Italy, but, unable to speak the local language, they flounder. In the English version, this plays as a gentle farce.

But in the Italian translation, this makes no sense: as Italian Papa Pig gestures to the Italian reindeer behind the information booth, everyone is speaking Italian. Somehow, though, nobody can understand one another. Language is unreliable like that.

Watching Peppa Pig is a vice I’ve developed this year, not because my frontal lobe has so atrophied that it can only digest five minute cartoons (although: possibly) but because on grey days I can console myself with that, by learning the language, that there’ll always be a warm, boot-shaped country to which I can escape.

I love Nottingham more than anywhere in the world, but it is prone, like anywhere in this country, to get drizzled upon; grumpy, under the grey end of a rainbow, shuttered away from itself. The Meadows here, for all their charms, are very un-Mediterranean.

DH Lawrence escaped from Nottingham to Italy in 1912, to get married on the white-shingled shores of Lake Garda. Through his intense charisma, Lawrence convinced his new

wife to abandon her family – to leave England, to run away from wartime mistrust of his radical writing.

In 1915, Lawrence published The Rainbow. Perhaps his best novel, it was quickly withdrawn: in one chapter, the teenage character Ursula begins a lesbian affair with her schoolteacher. For this unforgivable obscenity, the book was yanked from the shelves, and every one of the thousand printed copies was pulped. His effort to communicate had been frustrated.

Lawrence only doubled down. His next novel, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was to be even more inflamed and infamous. He decided to publish it first in Florence, away from his prohibitive home country – dedicated British readers could subscribe to import the book from Italy. When it arrived in their hands, it had stamped on it the author’s new logo: it was a phoenix.

Of course it was a phoenix. At the beginning of the 20th century, the mythical bird was everywhere: ‘Phoenix Cottages’ could be found in Lawrence’s native Eastwood, or you could caffeinate yourself at the nearby Phoenix Coffee Tavern. Insurance companies used the bird for their logos. You can imagine the significance to DH: the uncouth son of a miner could never stay down for long. A century later, he’s still regarded as one of the finest modern writers, far along the path to immortality.

Eternal life is the Unique Selling Point of the phoenix, but when you think about it, it’s a strange sort of continuance. It doesn’t, strictly speaking, live forever. It burns down and is reborn, cremates and un-cremates itself. In this myth, immortality isn’t just the avoidance of death, but having the wherewithal to keep being born.

So perhaps worthwhile things don’t have to go on forever – they can vanish, recollect themselves, and begin again. That’s the case with Nottingham’s history of print publications: there have been so many, and there are so few left. Just one example is the Nottingham Quarterly, a literary magazine created in the seventies by John Sheffield, featur-

ing at least one new story by Alan Sillitoe. In the introduction to the first issue, John memorably compares launching a new journal to launching out to sea in a sieve. To the founder of a new journal, that gives a very visceral sinking feeling. New publications have always been a risky voyage.

The original Nottingham Journal is another publication that’s long since disappeared. In its lifetime, from the 1700s to the 1970s, it offered daily news to the city, and writing experience for J.M. Barrie, Graham Greene, Cecil Roberts and many more. I should be clear that the book that you hold in your hands is not a continuation of that daily newspaper. But it is inspired by, and borrows some spirit from, the journals that have ceased to be, and the ones now fighting for survival against stiff competition from social media and the sort of digital infotainment that wants only to entangle you.

The New Nottingham Journal is by no means an obvious formula for success. And so our thanks is unreserved now to everyone who has backed and supported this project — whether with your money, your time, the strong scaffold of your encouragement, or by sending your work to our thankfully jam-packed email address. This journal exists in your hands because you saw this as a gamble worth taking.

Deeply in your debt, we’ve been working hard pulling it all together. In this first volume, you’ll find stories set on ocean trawlers, poems from the edge of…, essays about stuttering and longing, and photography that reframes some places we know and some that we don’t. Some of it is rooted in Nottingham, and some of it comes from elsewhere, from six continents. All of it is gathered here under the idea that print culture and our stubborn city in the Midlands are suitably matched — neither have yet come to the end of their many lives.

I have no illusions here. Creating a new journal of writing in 2025 is still, as John Sheffield said, like launching out to sea in a sieve. But it’s also Papa Pig speaking Italian to a cartoon reindeer. By which I mean that all communication is a process

of mischief, of a wide-eyed optimism, of bizarre persistence. The phoenix lives forever by refusing not to begin again. Lawrence knew this. When England turned its back on him, he went abroad to pull himself from the embers. He printed what he needed to print, and sent it flying to the people who needed it. Whatever headwinds blow across Nottingham –however wrenching it is sometimes to be an underlooked city – I am massively proud of this place. We are untrampleable. You’ll read this in our native writers, in the ones we bring in; in our old, shuttered publications, and, I must now hope, in this new one.

On those grey days in a city like this, sometimes there’s a smoke that clears, and you can see a new thing standing there. It’s always the same old bird, alive again, singed at the edges, but ready in its beak to sing.

I hope that makes some kind of sense.

Dear friends near and far,

Welcome to the New Nottingham Journal.

Andrew Tucker Leavis - Editor in Chief

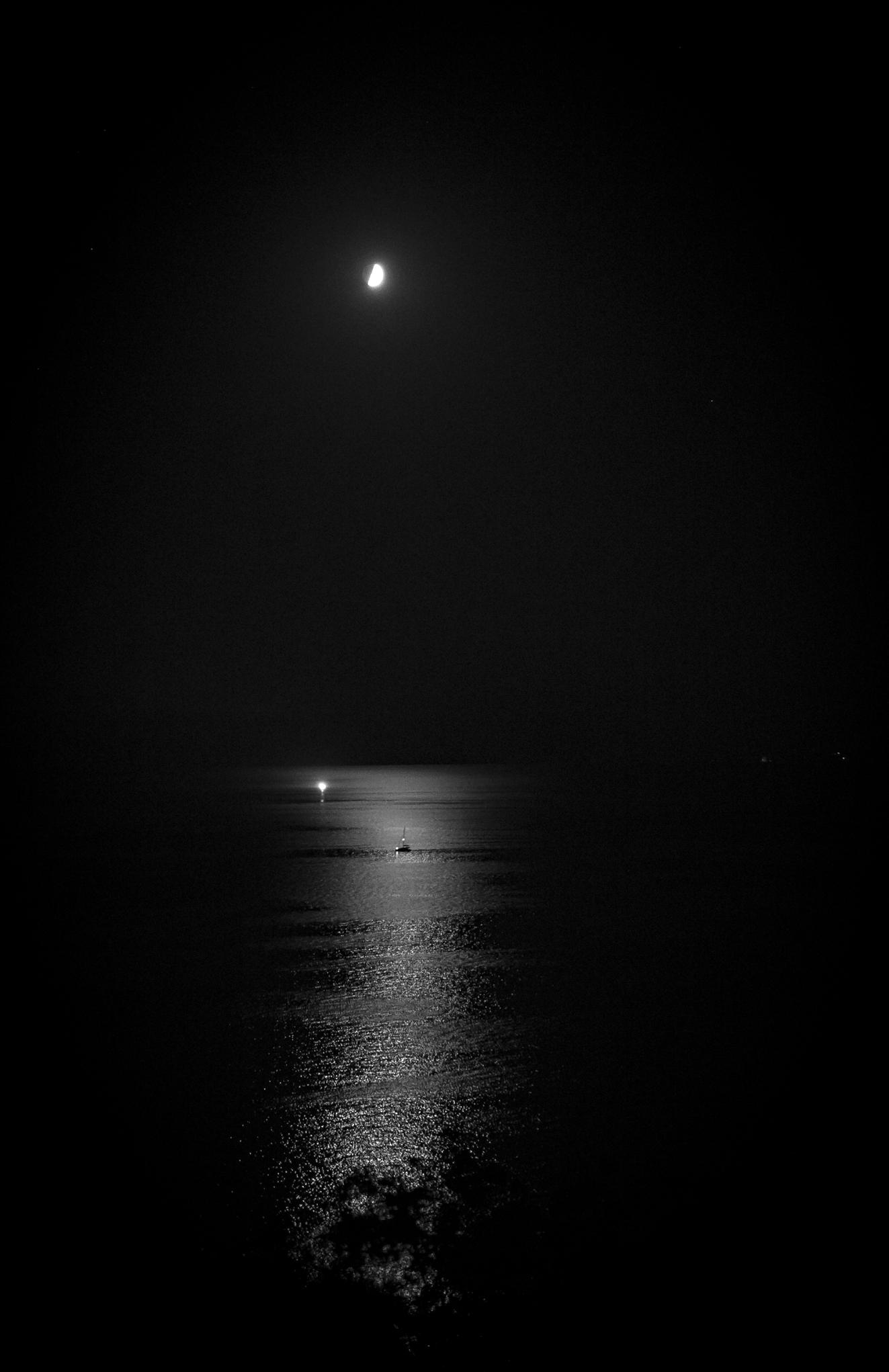

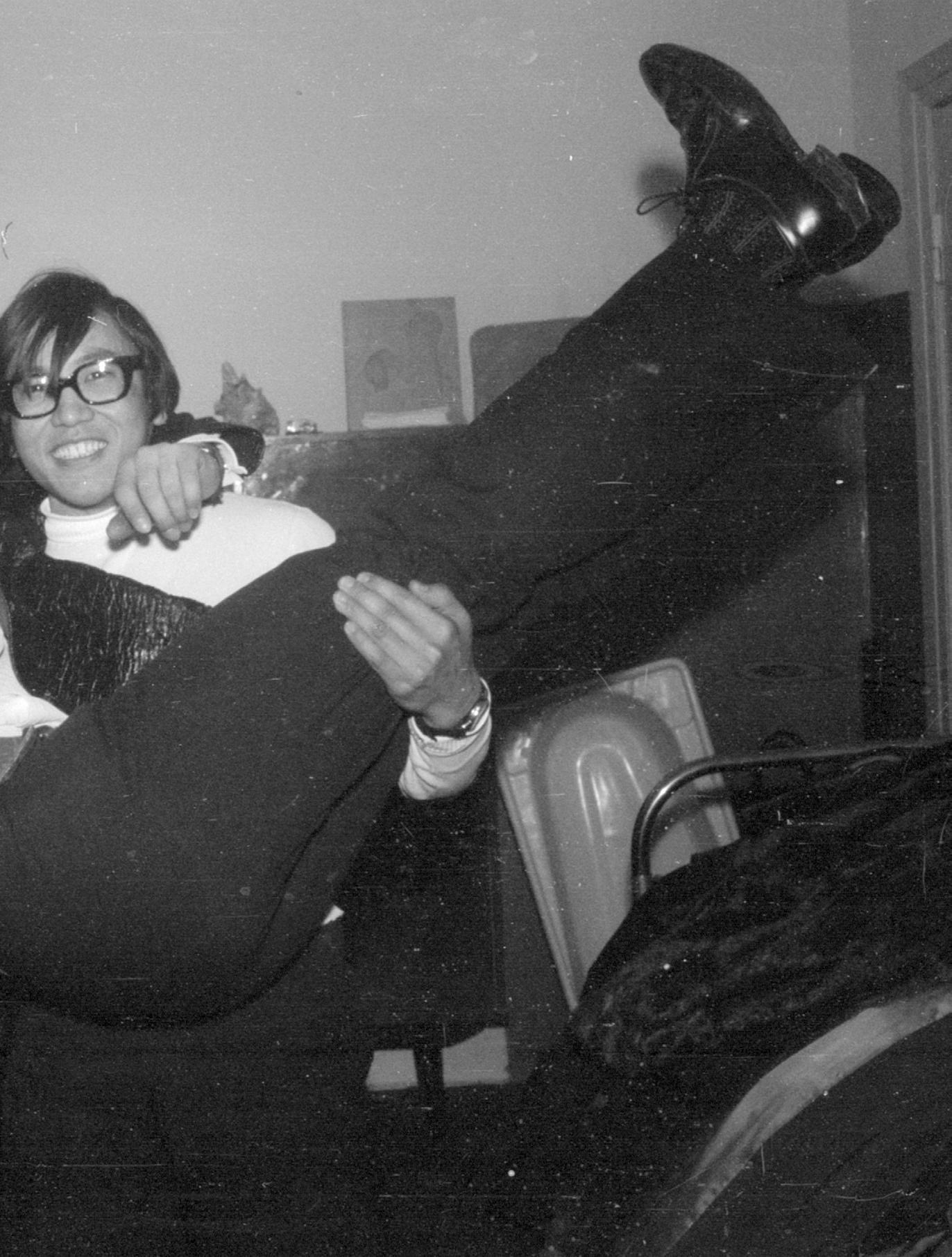

Photo by CJ Deocareza

Cussed City Benedict Cooper

Is it in the blood? The history, the culture, even the geography? Where does it come from, I often wonder – this city’s tendency to produce or attract rebels and rogues, mavericks and misfits?

It’s not just the outlaws, literary bad boys, machine-smashers, castle burners, England’s most outspoken football manager, even one of the few documented 17th century female highway robbers. The Rebel City has a way of producing rebel politicians as well.

At least, there are plenty of examples to help make that case – from the recent past alone.

There’s Alan Simpson, former MP for Nottingham South, who clashed with the Blair government over many issues, not least the Iraq War. There’s Tory maverick and rebel Ken Clarke, a lifelong thorn in the side of many a Conservative Brexiteer and free market nut. Fellow Europhile Tory Anna Soubry, as MP for Broxtowe, was so loath to support Boris Johnson’s Brexit that she quit and helped form a new pro-EU party, which Nottingham East MP Chris Leslie also joined, partly in rebellion against Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership.

And these days we have Nadia Whittome, who went against the Labour whips nine times in the first 10 days of July alone, over votes including PIP legislation and the proscription of Palestine Action. Ashfield MP Lee Anderson has certainly taken the rogue’s route through politics, switching from Labour to the Conservatives to Reform to become the latter’s first ever MP.

‘A golden thread of rebellion’ runs through the city’s history – so John Hess, veteran BBC political reporter and editor, tells me over a coffee. ‘There’s a cussedness to the city,

Photo by Ash Wroughton

a bolshiness. It goes back beyond Alan Sillitoe, back to the frameworkers and smashers’.

Anna Soubry also thinks I’m onto something with my ‘Rebel City – Rebel MP’ theory. Soubry’s back serving as a barrister – a KC no less – but her formidable parliamentary presence, and her refusal to take refuge in consensus, are still renowned in Westminster.

‘It’s true Nottingham has a history of producing people who are just, you could say, a bit difficult,’ she tells me when I catch her in between court appearances. ‘People who are rebels and they’re not afraid to be rebels.’

‘There’s that sense of independence. It might be in the water. There’s a strain of courage there. Or maybe we don’t have a fear gene.’

She ought to know. As well as being a fearless rebel against Boris Johnson’s pro-Brexit Tory government, which she eventually quit to form a breakaway rejoin party, Soubry, who grew up in North Notts mining country, has never been one to cravenly follow a crowd.

‘If I look back at my own life, I am not good with authority,’ she tells me. ‘I don’t like being bossed about.’ Boris Johnson wasn’t approached for comment, but I have a feeling he’d verify that.

Soubry admits that she could have made life far easier for herself. She could be a comfortably-off member of the Lords with a peerage and a pension by now, had she been willing to go with the flow. But she wasn’t; that’s not her style.

It certainly hasn’t been the style of another Notts Tory rebel, who still thunders away in the House of Lords as Lord Clarke of Nottingham, but is better known as Ken Clarke, the whisky-drinking, cigar-smoking, jazz-loving Chancellor. Lord Clarke is to politics, perhaps, what Brian Clough was to football: the man who never quite made it to the top, but could – perhaps should – have done. Cloughie was ‘the best manager England never had,’ and, Soubry tells me, ‘Ken is one of the greatest PMs we never had.’

There are easier ways to get along in life than being a

principled rogue, certainly in politics. You can climb the greasy pole much more easily if you drop your principles on the way up.

But for another great figure from Nottingham’s political history – who also didn’t like being bossed about – principles and the terrible toll of war meant that simply wasn’t an option. Alan Simpson wasn’t born in the city. Like other big Nottingham names he moved here as a young man and has stayed ever since; there’s something about Nottingham that gets in people’s blood. Arranging our interview, Alan tells me how much he’s looking forward to getting into the theory. Is there a book in this? I wonder, as I head off to meet him. And over coffee Alan agrees about the culture of radicalism in the city that adopted him – he cites figures such as 19th century Nottingham MP and firebrand workers’ rights campaigner Feargus O’Connor, whose statue stands in the Arboretum.

But it’s not about rebelliousness for the sake of it, he says. The reason Nottingham has always been a ‘slumbering radical giant,’ as he puts it, woken into bursts of angry activism, is that there are people like him (though he would be too modest to admit it), who ‘keep to their political roots’ and don’t back down.

To Simpson, rebelliousness is left radicalism: not a general loathing of what Soubry describes as ‘excessive authoritarianism wherever it raises its head’, but of a specific left wing kind. Yet Soubry applies the label of ‘rebel’ to the miners who didn’t strike in 1984, against the orders of the ‘authoritarian’ National Union of Mineworkers. Not a view popular on the left.

So you see that even in this short journey we find disagreement, strong opinion, maybe even a touch of bolshiness. Of course we do. It’s Nottingham.

Photo by CJ Deocareza

An Honest Politician Reneges

Emma Neale

You walk in on the headline news and it’s as if you’ve discovered a favourite, self-contained child crouched over a concealed treasure to see the glint between fingers and thumb is neither his new glasses, nor toy microscope, but your embroidery scissors, the miniature set with blades like the fine gold beak of a merciless bird and he snaps, snips, clips, dexterous in his focused, ferocious intelligence; there is a cold, opalescent drift from a radiant blizzard as he forges a technically brilliant creation: the model of a chemical compound, say, or of a supercomputer’s inner circuitry, all fashioned from something as unlikely as tissue-paper, bright as persimmon and what you see in his soft-yet hands is a species of elusive moth its zinnia-red wings with fluted blue and yellow trim, its owl-feather brown thorax, antennae as curved as ferns and multi-stringed as harps, now bisected, folded, cut and twisted into a result complex, terrible and dead.

Night Shelter

Emma Neale

A man in a concrete alcove downtown raises his bottle of whisky and calls across the street to three of us, ‘Girls’ night out, is it? It is, isn’t it? ’ey! Look at me when I’m talking to you!’

We try to ignore him the way we would the one lasso-necked seagull in every flock, the self-elected General who stalks and bawls out all the others for some petty, manufactured dissent.

Yet hours later, in the hard, split core of a cold snap I wake as if to the sharp knock of trouble and I can see him there, hunched small in the doorway, like a child who wet his sheets lost in his dream where he became a body torn as light across the sky as a discarded till receipt, his bones browned as windfall apples suckled on by flies and wasps and I want to know, who was there when he first cried out from the deep, bricked well of fever, night terrors in his head like blood-laced water?

Did anyone draw him, rocking, back up to the surface, dry him, murmuring, I’m here, you’re safe now, there was no well; on either side of a wide, shared bed, did anything like love ever raise its doubled covers, strong as a soffit, paired as wings?

Photo by CJ Deocareza

Sky-Clad Indu

Menon

Trans. by Nandakumar K.

The day my brother married a Kannadiga Muslim girl from Moodabidri, I opened out all the windows of my room, flouting all the restrictions placed upon me. In the shimmering heat, the train – its windowpanes still unsullied – sped through the day’s blinding light like a glistening, red-hot catfish. The smoke from the chugging blue trains, smelling of metal, had blackened the walls of my husband’s childhood home.

During the afternoons, when my husband went out for his party activities and my mother-in-law lay asleep, I would stretch out my thick neck through the window like an overweight tortoise, keep my head out, and watch myriad types of people and things as the trains trundled past. Everything that my window provided was a revelation.

Although he was fair and slim, my husband resembled a Hindu god. He had eyes that sloped up on either side of his face, and the wide, fan-like ears of Ganesha. Every night when he returned from his work in the RSS Shakha paramilitary group, my mother-in-law and I would be watching a Jai Hanuman serial on the TV. Quivering with devotion and excitement, my mother-in-law would keep chanting devoutly: ‘Hare Rama, hare Rama’, whenever Hanuman or Rama appeared on the screen.

One evening my husband reached home early, very flustered and bothered. Holding my hand, he took me into our bedroom and bolted the door.

‘Our Jayakrishnan has goofed up.’

Flashes of lightning lit up my brain. My palms became sodden with sweat.

‘Don’t be scared. But he’s gone and married a Muslim.’

‘I thought something had happened to my amma.’ I had been picking jasmine flowers to make a garland for the deity. My amma, my mother, was an inmate of Gandhi Ashram, the hermitage in Kamala Sevagram.

‘When I think of your mother...with all the infirmities of old age...’

I looked at my husband sympathetically. I made him understand that father, bapu, valued every religion equally – and

that for my amma, faith was never important.

‘As for bapu,’ he said, ‘whatever. I’ve been promised a seat at the next election...’ With a distracted look he lowered the jasmine branch so I could pluck the flowers.

I was getting irritated. It put my back up that my man knew nothing about bapu.

‘It’s no use shouting Bharat Mata ki jai,’ I said, ‘“Victory to Mother India” – she is not what you think she is. How is it that every time my brother has seduced a Muslim girl, then debauched her and left her, you haven’t warned him?’

My husband himself had informed me about this side of my brother. He’d told me that Jayakrishnan had understood the essence of Hinduism. When I’d heard him say that, I had looked at him in shock.

‘Each girl’s debauchery,’ he said now, ‘means the ruination of her community.’ According to my husband, Jayakrishnan had a hardline agenda. Annihilation, razing, extermination. He is doing it in his own fashion, my husband said.

‘But doing such things?’ I said, ‘What is to be achieved by causing dishonour to anyone?’

‘I’ve been cautioning him. This time, though, like the monkey in the Panchathantra, he has pulled out the wedge and his nuts are in a tight spot.’

The news had stunned me. Every time my brother seduced a girl, humped her and left her in the lurch, I was scared that my yet-to-be born children, and even the generations to come, would be visited by his sins.

‘When the people caught him red-handed,’ said my husband, ‘it was all much of the same. He was grabbed without a stitch of cloth on him.’

Whatever the circumstances – even a shotgun wedding – I was happy that my brother had finally married. I knew that a fervid kind of feminine love was essential to mellow his hard, firing heart. But as a person, I was never able to really understand him. The slightest provocation was enough to distress him.

The squeak of chalk on the blackboard in the Malayalam

class used to be enough to make him have an epileptic fit. The moment the teacher finished writing ‘nga, nja, na, na, ma’ on the blackboard, Jayakrishnan would shriek, pull out a clump of his own hair, and keel over onto the floor. He would curl into himself, like a millipede taking protective action.

When our parents fought, he would roll his eyes and scream his head off. On the day the court granted their divorce, Jayakrishnan had gone to throw stones at the state road buses and trains.

When the court gave my father custody of Jayakrishnan, he made a scene and went away with my amma to the Gandhi Ashram instead. All through the journey he lay against her chest, gnashing his teeth.

When he was twelve, he was taken away to Sevagram, Gandhi’s residence in Wardha. Once, amma and I visited him at the Ashram. He was working in the village, cleaning the overflowing public toilet – he went down into the pit and shovelled shit into basins. His body and face smelt of the black shit, and he resembled it too; the nauseating reek saddened me. But Jayakrishnan’s transformation made amma happy. Pulling up the hem of her khadi saree and tucking it into her waist, she too helped carry away the shit, just like the villagers. At that moment I recalled that my mother was a high-caste Brahmin woman.

I hated Gujarat. My mother sought an alliance for me early, and at nineteen I was married off. The trip to Wardha after my wedding was fun; my new husband was enthusiastic about the trip as well, since his party was ruling the state. As soon as we disembarked at Wardha, a group of men garlanded us with saffron-coloured flowers.

‘Bholo Sri Ram ji ki...’ Chant Lord Shree Ram... ‘Jai.’ Hail.

‘Bholo Bharat Mata ki...’ Chant Mother India... ‘Jai.’ Hail.

I found my mother’s behaviour odd when we reached the Ashram. She spoke to me secretively, caressing my head with

her fingers, which smelt now of groundnut oil, where once they had the fragrance of herb-infused coconut.

One day Jayakrishnan blew in, ranting and raving, after being sent to Sabarmati Ashram for a week of voluntary service that he had not completed. His right hand had become spastic. His tongue, on which he had bitten down in a frenzy, looked bloodshot like the Kali’s. He went to the apiary and, using his left hand, threw down and smashed all the honey bottles. Then he yanked out the charka spinning wheels from inside the Ashram – he trampled on them, smashed them, and threw them in the fire.

‘Kanthi, Kanthi, Konthi...’ he was ranting, wilfully mispronouncing Gandhi’s name as he threw stones at Gandhi’s framed photo. When my mother started to bawl, he emerged from the Ashram building and started to tear up and throw away his own clothes. Finally, naked but for a string girdle at his waist, he strode towards the city.

‘He has now become a sannyasi ascetic,’ my mother said, ‘I’m told he’s in the Dulai cremation grounds. But I’ve never been to see him.’

So the next day my husband and I went. On either side of the road were Sadhus and ascetics. I watched with curious awe a Sadhu who was doing penance, standing on one leg – in his matted hair, sparrows had laid their eggs.

The ascetics wore no clothes. I found their nudity gross and abhorrent.

‘Nimala, they are Digambaras. The sky-clad. And now look at those over there, they are Shaivites.’ My husband pointed out a few Sadhus with dreadlocked hair and bodies covered in ash.

Near the cremation grounds I saw a Digambara ascetic with a group of women in front of him.

‘Physicality is what the Digambara school follows,’ he said. ‘But it’s not meant for women.’

I realised that I knew the voice and its owner. It was Jayakrishnan, my kid brother who, in his childhood, would

cover his nakedness shyly with his tiny palms. Now the hair of this shameless man was expressed like the sinuous, gnarled roots of some ancient tree. In between all this hair, his white organ dangled down with the liberation that comes only from detachment. His nudity stared at me with a cruel joy.

‘Please...’ I broke down and cried. I thrust my towel at him and said, ‘Eda! You better wear it!’

‘My child, I am a Jain who has renounced everything.’

‘Eda...’ In my anger I tried to grab my brother. ‘We can meet a good doctor,’ I told him.

‘Our flowing asravam is what leads to the endless cycle of births and rebirths. Samvaram – to shut the world out – is what liberates us. Anger is one of the asravams, my child.’

Even after returning home, the vision of Jayakrishnan the ascetic continued to trouble me.

It was a while later, when my husband had been to Gujarat and returned, that he told me with obvious relief: ‘Your brother has got his marbles back. He’s with us now in Gujarat. He told me that he has realised the greatness of Hinduism.’

The only consolation I derived from it was that he had started to wear clothes again and that, if we ever met again, I would not have to listen to his lunacies.

Four years later, one early morning after the Wardha Passenger train had gone by, someone knocked vigorously on our door. It was my brother again. He entered without the least amount of hesitation or embarrassment.

‘Amma had given me this address a long time ago. There are a lot of problems in Gujarat. I managed to get away without the police or neighbours being any the wiser. Now Karnataka will be the land of my karma.’

He said that he had found a job in Moodabidri, near Mangalore, and he would be leaving the same day. That was to be the last time I met the absconder, my brother.

My mother-in-law insisted that, since he was now married

to a Muslim girl, we should not have any relations with him. Since I valued peace and stability in my life, I did not disobey her. A year and a half passed, during which my mother-in-law fainted in the bathroom, I became pregnant, and my husband was nominated as a candidate in the state elections.

When the doctors declared that my pregnancy – conceived after many years of cohabitation – was problematic and that I must have bed rest as a result, I kept the windows open boldly and watched the sights outside.

Then, one Friday evening, my mother called me. Weeping and indignant, my amma let fly a few imprecations from the other end of the line.

‘You two were so close...but even you didn’t tell me.’ She said that and continued to cry. ‘Isn’t he your sibling? My poor, sick child.’

‘Ammae...’ I was at a loss, ‘What has happened to Jayakrishnan?’

‘He’s no more.’ Her tone was wrathful again. ‘Today is the seventh day,’ my mother’s voice quivered down the line, as though she had the chills.

My body arched and I fell back heavily, the receiver still in my hand.

Three days later, showing no embarrassment at having lost in the polls, my husband came home to console me. I got the distinct feeling that he already knew that Jayakrishnan was dead.

He took me to my brother’s home. The passers-by and neighbours gave us looks of surprise as we approached. They all hung around expectantly beyond the fence, as if waiting for something momentous to happen. Jayakrishnan’s wife and child were home. Holding my swollen belly, I went up the steps, gingerly, carefully. My husband waited outside. Inside I found my amma.

‘You knew everything,’ she said. ‘You and your husband’. Her face looked like thunder. Then the storm began to pass

from her eyes. ‘Forget it now – everything’s over now. Which side does the baby kick?’

‘The left side.’ I touched my belly and stared at my mother.

‘Oh, God! It looks like you’re going to deliver a boy. He will have to bear the burden of all your brother’s sins, the poor thing.’ Amma used the edge of her khadi mundu to hide the nakedness of Jayakrishnan’s own baby, who was with us now too.

‘Now this, another burden,’ she said. ‘It’s a good thing that your brother died. There’s no accounting for all his wickedness – if he were alive, I don’t know how many girls like this baby’s mother would have had to suffer. People are scared of this disease. She and the child must have it now as well. Because of him.’

My head snapped to the side as if I had been slapped, and darkness entered my eyes. My words were licked away in an ocean of saliva.

I felt that I heard my mother’s voice say that she did not plan to return to the Ashram, that she would stay there until she died – since the mother and child would be orphaned otherwise, and because in my condition I should not exert myself. I could hear Jayakrishnan’s wife wailing softly in an inside room. I walked out to my waiting husband. Ignoring the eyes of the curious crowd around us, I hugged him close.

At that same moment, the rolling and twisting inside my womb felt like a storm breaking upon the left side of my belly. The baby kicked me brutally, in anger, in resentment and protest.

He was wrapped only in sky, and from the inside he stared at me with a vicious joy.

The Box

Amy Acre

Hold this box

Hold it in your lap and let the busy heat of its contents warm your crotch your drumstick thighs

You may think the weight impractical but if you stay perfectly still you will soon see how easy the assignment Allow yourself to stroke the silky pink ribbon with the pad of the thumb you use to signal approval so silky against the rough industrial card of the solid box

Don’t open it that would ruin everything There you go good girl

Now stay like that for the rest of your life

The Rainbow

Amy Acre

Although not a woman of faith, you know – as we all do –about the flood, the dove, the rainbow, so when you saw it on the wall – trick of the morning light, colorific and spectral –you thought he was coming home, god saying enough of this madness, I just wanted you to stop sweating the small stuff, I wanted to shock you back into the faith you left in the nineties, but – and here, god exhales, finger on forehead – rainbows, I’m sorry, are fickle. It’s easy to believe when you want something and that’s why I had to keep him with me.

Photo by Nicola Davison Reed

Fragrant Bananas

Hongwei Bao

When I first came across the English word ‘banana’, I was surprised by its simplicity. Its rhythm and rhyme bring a weird tone of musicality, like singing, like humming, like whispering. And its spelling invites the association of a bunch of fruits hanging down from a branch, waiting to be handpicked. The Chinese name of the fruit is equally as tempting: 香蕉 – literally ‘fragrant banana’. It is common for fruits to be named in double syllables in Mandarin, although the second character usually suffices to convey the meaning. The person who first decided to add the word ‘fragrant’ to the word ‘banana’ must have had a touch of genius: the sound of the exotic, tropical fruit immediately conjures up a sensory experience associated with an inviting smell. Not to mention that the character 蕉 is idiographic – resembling a big tree, with a bunch of banana fingers hanging down among its leaves.

I was ten, living in a northern Chinese town located in the middle of the Gobi Desert near the China-Mongolia border. I was sitting beside a hospital bed accompanying Mum, watching transparent liquid dripping slowly and steadily from a bottle into a plastic IV tube connected to her arm. Earlier that day, Mum had been sent to the hospital following a heart attack. Now, she was sitting on the hospital bed against a white pillow and a blue wall. Her face looked pale and her arms skinny. She smiled at me, as if to say she was alright. She gestured to the bedside table and told me to help myself. On the table lay some presents brought by an earlier group of visitors: boiled eggs soaked in wet tea leaves, spam sausages, pears and apples. There was also a bunch of bright-yellow, curvy-shaped fruits. They looked like big hands wearing a yellow glove with fingers pointing to the air.

I knew they were called ‘bananas’. Although I had never eaten them before, I had seen them on television and knew that they were a delicacy for city people, especially those from the south. In this small, northern town, bananas could still only be spotted in big glass fridges at the largest department store. They would also crop up on special occasions such as weddings, birthdays and hospital visits.

I picked up the bunch, tore one finger from the other, and offered it to Mum. Mum shook her head and asked me to eat it.

I held the smooth skin in my hands, unsure about where to start. Its bright, yellow colour looked very tempting. As I was playing with it, my fingers made a few dents on the peel. I held the two ends of the banana and bent it with both hands. The peel opened. The white fruit with some strings popped in front of my eyes. I caught the fruit just in time before it flew into the air.

I picked up a small piece and put the white fruit in my mouth. It was soft, smooth and slippery. Not sugar-cane sweet, but mellow and with a lingering aftertaste. Without much chewing, the flesh slid down my throat and melted like candy floss. The sweet aftertaste soon spread in my mouth, throat and stomach.

Mum looked at me with a contented smile. The liquid from the bottle continued to drip quietly and rhythmically. We were not well-off, but Mum always wanted to give me the best in the world. I became the first one in the family to eat the ‘fragrant banana’, and later the first to go to university. I didn’t tell Mum that I liked boys instead of girls, in case it would disappoint her. The worst thing that a son could do to his mother.

I moved to Beijing to attend university and, after graduation, got a job in the city. The banana was a more common fruit in the capital. To afford the high rent and living costs, I had to do several jobs to make a living. My weekend schedule was packed: in the mornings I taught a group of school kids

English in the eastern part of the city, and in the afternoons, I hurried to the western part of the city to give private lessons to a student. In between I was in transit, navigating the city’s complex public transport system. There was often no time for a proper, sit-down lunch. Bananas became my favourite snack. The reason was simple: they required no washing or cleaning, and they were easy to peel. Besides, they contained plenty of sugar and starch. They could stop hunger and get one reenergised immediately.

Before I left the flat every morning, Ming would put two banana fingers in a reusable food bag and place them in my rucksack. He was from southern China and bananas were common in his hometown. We had been seeing each other for six months. He was several years older than me and was a junior doctor working at a big hospital in the city. He was ambitious, capable and hard-working. ‘This young man has a bright future,’ his senior colleagues said. They probably wouldn’t have said so had they known that he was gay, or that the man who often visited him was not his old schoolmate but his current boyfriend. He lived, without much privacy, in the hospital staff dorm. Most of the time, he would come to stay overnight in my flat. Our relationship worked reasonably well until, one day, I announced my plan to study abroad.

I didn’t have to leave Beijing. But having worked there for five years, I could already see my predictable future. I was fed up with living a closeted life. I didn’t want to act straight and pretend to be ‘normal’ in front of others. I had done it long enough. I wanted to escape from the city and start a new life, in a country where I could be myself.

‘What am I going to do?’ he asked. I wasn’t sure whether this was rhetorical, or a question for me. I said he could apply for a university to study abroad. He shook his head. He wasn’t confident about his English. He had just secured a permanent position at the hospital and was expecting a promotion soon. For a person without the right family connections, he had done extremely well through hard work. It would be

difficult for him to simply leave everything behind and start a new life. ‘What are we going to do?’ he asked. I realised that he was asking about our relationship, our future – if we had a shared future at all – and I fell into silence. In a grand plan of pursuing dreams and sexual freedom, our relationship was not my highest priority. We had been together for six months, and already I could feel our personalities straining apart.

The day I got my offer from a UK university, I shared with him the news over a text message. After some silence, Ming texted back – ‘congratulations’. That evening, I was waiting for him to join me for a celebration. He didn’t turn up. I called. His phone was switched off.

I didn’t have bananas in my rucksack the next morning, or the mornings after. Years later, he would become a senior doctor and head a clinic in that hospital. He would marry a woman and have a daughter. He would occasionally think of me, as I would think of him, whenever he’d see a bunch.

It was cold and wet in the UK. It was difficult to settle down, but I managed to, eventually. The biggest challenge about living in a different country was not the food or language; it was the feeling of loneliness on those long, dark winter nights. There were plenty of international students from China, but most of them acted very straight. ‘Have you got a girlfriend?’ was the common question. I didn’t know whether there were any gay students among them, and it would have been risky for me to disclose my own sexuality for fear of being alienated. Meanwhile, there was a large queer community in London. Rainbow flags were everywhere during Pride Month, pastelling the city’s skyline, but I couldn’t see many Asian faces underneath. I was alone and lonely.

Even on gay dating apps, there were mostly white men, often known as ‘gay Caucasians’. A few of them had ‘No Blacks, No Asians’ or ‘Asians don’t bother’ clearly specified in their profile. Occasionally I had banana emojis thrown at me on the app. I came to learn about racism within the gay community. On the other hand, there were people exclusively

attracted to gay Asians – a fetish, almost. A ping on the app: ‘I love Asian boys. You all have such smooth bodies and nice bottoms’.

Then I came to relearn the word ‘banana’. ‘Are you a banana?’ a person of East Asian heritage asked me. I didn’t understand his question at first, so I asked for clarification. He explained that in colloquial English, ‘banana’ refers to Asians born in or living in the West, especially those who have adopted Western lifestyles or internalised Western values; in other words, ‘yellow outside and white inside’. The phrase is based on stereotypes, referring to the historical discourse in which Asian people were seen as racially ‘yellow’ and the ‘Yellow Peril’ anxiety that was said to threaten Western societies, because of Asian people’s distinct looks and values. That question made me wonder whether I was a banana. What were my cultural values? But this encounter raised more questions than I could answer: are Asian people and cultures intrinsically different? For whom, and according to whose criteria? Do gay and straight people share the same cultural values? And is there a cultural heritage that is particular to queer East Asian people? I can think of stories such as the rabbit god, the ‘shared peach’ and the ‘cut sleeve’ – classical references to queer intimacy in ancient China – but how difficult and impossible it would be to recover those things and retain them in a globalised world! My queer cultural heritage is as much from Leslie Cheung as the rabbit god –from Oscar Wilde and Freddie Mercury. Perhaps having a mixed heritage is no bad thing.

Almost all modern cultivated banana plants are cross-bred. They began in the mismatched pairing of two South Asian wild plant species: musa acuminata and musa balbisiana, both of which are seeded. But their hybrid, cultivated form does not have seeds and is therefore sterile. It has a mixed heritage itself.

We queer Asians who have been denied our cultural inheritance, who have been trapped between cultures, are good

examples of hybridity. Being a banana doesn’t have to carry a negative connotation after all.

The English phrase I like the most is ‘go bananas’, which I soon learned is a colloquialism for ‘becoming very excited or angry’, as if bananas were highly emotional fruits themselves. The first time I encountered the phrase I didn’t know what it meant, but I thought it was cute. In my mind, I imagined myself becoming a banana, or a bunch of them, braving the world with my queer Asian siblings until the entire sky would turn bright yellow – and utterly fragrant.

Phoenix Trees

Janet Gunter

There is a row of cherry trees in the Forest Recreation Ground, leading to the playing fields. They are generously sized – clearly the oldest in the park, their flowers heavy and humid when cupped in the hand. The trees form a canopy, this tunnel of petals that I imagine being like Kyoto. These cherries bloom during a certain week or fortnight in April.

In 2020, when I got up from my Covid sick bed for the first time to leave the house, they were in full bloom. It was Easter Sunday. While I’m not Christian, I did feel a certain new start that day, fancying myself free of the frightening new virus that loomed over us. I didn’t know then that this feeling – rising from my sick bed and coming back to life –would become familiar.

Five cherry blooms later, I am still sick. My energy is severely limited; I spend most of the day with my feet up. As I’ve come to learn in outings on good days, there are other notable cherry trees in the Forest Rec: the big one at the café, which creates a big pink corona over the space, and the white cherry grafted on top of another pink one. Or the row that runs near the park-and-ride car park, where they’ve been interplanted with delicate birch trees.

But the other cherry trees that marked me are the ones just outside the wall of the Rec, in the Rock Cemetery. They’re found in a sunken, walled section of the burial ground, where the victims of the 1918 influenza pandemic are buried.

These trees are massive, perhaps the size of a gigantic tropical ficus – the ones with the hanging aerial roots. When their leaves come in, the cherries provide shade for the massive stone markers made to honour those stricken by the flu. Names had once been carved on the markers, but are no longer clearly decipherable.

There is no gentler way of putting it – this is a mass grave, and it was designed to be hidden from view. To reach the space, you wander to the back of the cemetery and take a set of stairs – each one tall but spaced widely apart. The place feels like an imagined hypnosis prompt. One cherry flowers early, the other waits until April. They rise above the cemetery wall and, as we walk in the Forest Rec between January and April, they wave to us with their thousands of bright hands. Besides the cherries, the centennial oaks are the other trees that mean the most to me in the Rec, and recently I found myself discussing them online. This was unexpected. I’d joined the ‘Queerdos’ Zoom for disabled queer people in the Nottingham area, and towards the end, our facilitator Evie proposed an exercise where we’d give voice to trees. She sent a photo of eight tree types – oak, chestnut, spruce, and so on. Then she floated off to the next breakout room, and there was a long silence. I think perhaps everyone had expected to give voice to an individual tree, a lone witness to our world, not a variety – a tree stereotype!

Somebody expressed this thought, which was greeted with nods. I said I often imagined the oaks in the Forest Rec had harboured chats between Luddites. The person who’d spoken replied that their ancestors were Luddites. Then they talked about a conker tree from their childhood that had fallen but remained alive, recumbent – a phoenix tree. Their siblings used to climb up and down it, practicing key tree-climbing skills.

That sparked a discussion about these trees, which only need a couple of roots in the ground to live. I mentioned I’d just seen a mature birch like this – with perhaps 90% of its roots just floating in the air, dried out and inert. But while it lay down, the birch was thriving.

There were nods, and an unspoken recognition about the symbolism that such a tree had for us. The Descendant of the Luddites interjected that the exposed roots of these trees can unearth archaeological treasures – as if the tree were performing a grand reveal, just for us. Then they mentioned the

Photo by CJ Deocareza

massive tree in the Arboretum that’s supported by sturdy iron braces. Oh, I chimed in, the fig tree. We were the only ones in the room who seemed to know what we were talking about.

I had immediately remembered the Scottish Covid Memorial, the work of Alec Finlay, an artist with ME-CFS and Long Covid who I’d met in an online support group in the early days of my illness. Despite being unable to walk beyond his garbage bins, he had conceived and created the memorial in Pollok Country Park called I Remember, which is made up of 40 ‘tree supports’ – wooden braces made for oak trees which have begun to lean. Some look like stick figures, pushing back against the trees leaning onto them. Others look like utilitarian objects. Each one has been custom-designed and imprinted with a short phrase: ‘I Remember’.

Here in Nottingham our Covid memorial is one hornbeam tree, still-juvenile, planted in the Forest Rec. The dedication took place on a grim March day; there were maybe fifty people there, bearing daffodils. Some brought printouts in memory of their loved ones, in plastic sleeves to resist the rain. It was such a profoundly lonely event.

Not far from this young hornbeam tree, there is an old recumbent oak, which fell over just after the Covid tree was dedicated. It’s part of a line of oaks that I figure are between 150 and 200 years old. It might have heard the Luddites’ conspiratorial conversations.

After the online discussion I found a paper called ‘The Ecology of Scotland’s Wonderful Recumbent or “Phoenix” Trees’. It suggests that only older trees tend to fall and stay alive; it is not uncommon for a 200-year-old tree to fall and then live for another fifty to eighty years. The authors aren’t sure why none have been found to live longer than this: whether it’s because they die off naturally, or because people use them for timber.

The paper argues for an effort to raise awareness about phoenix trees, and the ‘value and significance’ they hold. It says that professionals and landowners need to be brought along so that they don’t just consider them waste and chop

them up. I was pleasantly surprised, I confess, when our park staff didn’t dismember and remove the recumbent oak.

‘Phoenix trees,’ the paper reads, ‘combine several compelling elements: their enigmatic sculptural beauty, their compelling efforts to survive against the odds, and the unlikely stories of how they adjust themselves to their recumbent positions.’

On days when my health allows me to walk to the Rec, we visit this oak, taking the dog up the reclining trunk, mining its bark with treats. My partner complains, justifiably, about the litter and used condoms at its base. We often talk about leaving a sign in the voice of the tree, asking people to respect it. Still, I have no doubt that – if the chainsaws are kept away – the sideways phoenix will outlast me.

In This Version of the Story

Vanessa Bell

Trans. by Chase Cormier

in this version of the story I’m five the light stages a perfect choreography of dust from which I invent secret worlds the open door leads to the balcony where thousands of leaves dance in the hot summer air bécaud finds his country as I walk the beach whose belly has never been touched I discover what an olive tree is and the right way to fall asleep beneath it my father grinds coffee beans the flat fills with promises a slow day lies ahead

in this version of the story I’m seven my alcohol-soaked father sinks into the bed I walk alone, chin-waving to each of the massive trunks their many arms brush against each other above my head I live in the most deprived part of town a cement area modelled on new york made up of a dozen quadrilaterals except for the path I take to get to school it follows the course of the dried-up stream a plaque with the name of a bird bears witness I am a poor child sated with stories and wild beasts whose bites I don’t know yet the trees are parents pointing towards my destiny under their protection, I learn to breathe

in this version of the story I’m nine my great-grandmother is a cascade of laughter in front of full pails the thaw pays off we sink our legs into what snow remains open a path from the wood to the cabin simmer, sing, celebrate the syrup, its return a prayer to end winter in this version of the story I’m 26 the oak veils the ardour of a kiss long as desire a slow crossing of my body makes me a mother I emerge glorious in iron effluvia adorned with sutures my name is a song from which my daughter draws milk I exchange my pain for a life crowned with lilac a whispered vow they both reach for the sky in this version of the story I am ageless my mother is a bear who calls me up north I choose the forest, lick its resin recite aloud the essence of each tree their exhale – a hymn a lullaby lying against the lichen I invoke the ancient course of things that long before the churches carried the mysteries sanctified, you appear under the canopy our bodies dance in the liminal space of our memories rain and a hundred raging fires could not erase the beauty for our songs are the guardians of the land I return to the place of my birth the trees are a mother gifting truth in the hollow of a closed fist sleep my child sleep as long as I stand there will be tomorrows

Photo by Ashley Gallant

Palilalia Rich Goodson

My tic began when I was six. And it began because of one of my realisations:

The words people speak are not the same as the ones they write.

I realised that while spoken words were messy and unfinished and ten-a-penny, written ones were a lot more predictable and reliable – plus, they got you gold stars if you got them right. And I wondered: could spoken words get me gold stars too?

From that moment on I went about checking every sentence before I spoke it. It came from a fear: that a sentence might exit my mouth unfinished or ungrammatical or poorly enunciated, or in the Nottingham dialect – or falling short of what I might put on the page. It might be unfit for purpose. And from this there was only a miniscule conceptual leap to dirty. The words that left my mouth might be dirty, because they came out of my mouth, and my mouth was part of my body, and my body was dirty…

Wasn’t it? My mother had told me that once: that I was dirty. I think I was two. So of course I believed her, and thought that it was an unimpeachable statement. A foundational statement. That’s dirty, she’d said, in a tone of aggressive disgust, and she’d walked off into the kitchen. A moment of tiredness, probably. She was twenty-three. Nothing more. A moment she probably soon forgot. After all, I probably was being dirty.

The shamer can shame as an act of love. The shamer says: I shame you to let you know that this tribe and all its ancestors does not do the thing you just did. You will be exiled from this tribe if you do that again. I shame you to let you know that you have crossed a line into something I do not

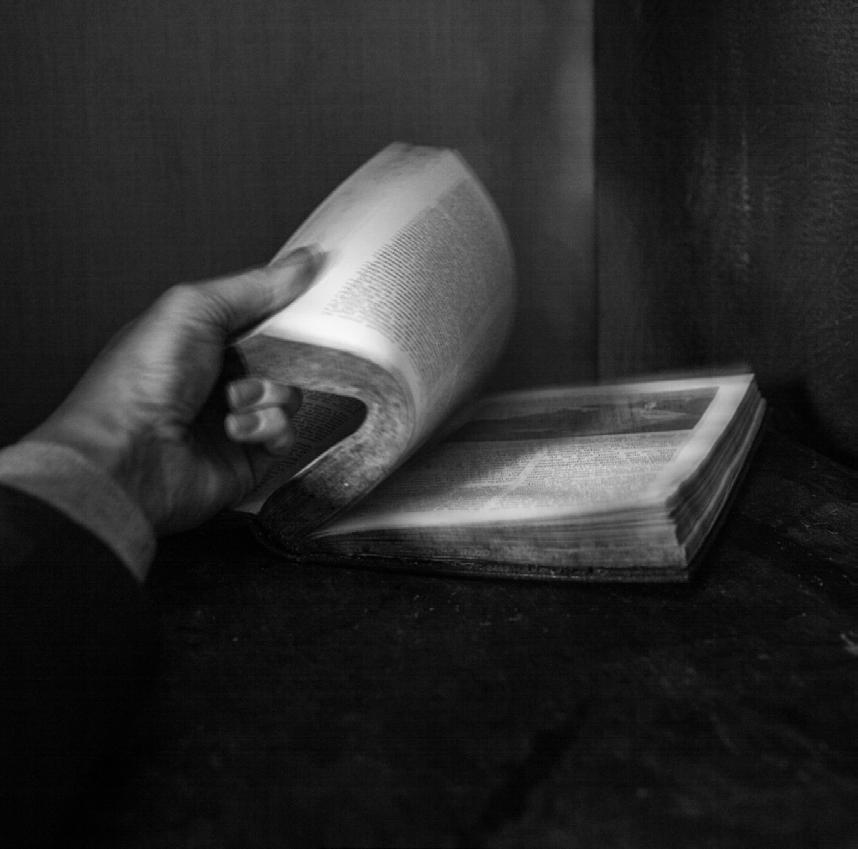

Photo by Shashank Dhongadi

understand, and which this tribe will not understand, and which its ancestors will not understand, a line which divides the civilised and the uncivilised, the moral and the immoral, the clean and the dirty, the halal and the haram, the kosher and the un-kosher: the trefah.

Trefah means: torn apart by a wild beast.

The shamer says: I shame you to let you know that I want you to stay on this side of the line: whole, safe, not torn apart by a wild beast.

The shamer says: I shame you as a warning, as a teaching. I shame you to protect you, to prevent you from being ridiculed or exiled.

The shamer says: I shame you out of love.

But it depends what tribe you’re born into and where you find yourself. One tribe’s wild beast, ready to tear you apart, could be another tribe’s pussycat, ready to lick your earlobe.

When my mother said I was dirty, she left my simple, two-year-old self stupefied. Horrified. Because it was at that moment that I decided that her love – her very presence –depended upon me being clean.

So I got with the programme, as they say. I would not be left at the river’s edge, in a basket, in the bulrushes, like Moses, where the wild beast might be a crocodile. I would not be taken away by the Dirt Police with their flashing blue lights and durr-durrs. I began to rehearse each sentence under my breath, a second before I said it out loud.

A second before I said it out loud.

So this became my tic. My happy glitch. My safe little trap of repetition. I’ve since learnt that it has a name:

Palilalia.

The first time I found myself doing this – being palilalic – I was holding Mum’s hand as we crossed the high street in Beeston where we lived. She was wearing a maroon mac. I remember a nearby boutique thumping out ABBA’s ‘Mamma Mia’. I remember bus fumes and yellow sunshine, and her looking down at me and listening to me, looking a little worried and a little proud, and me realising that this was a way of always being safely angelic in her eyes. I imagined seeing all the words in the sentences I was about to speak, lining up like I’d seen in the pages of books at school (because there were no books at home). I imagined the words of each one moving smoothly across the moist curve of my eyeballs from right to left. Fit, clean and orderly. Of course, this got in the way of seeing things.

Of course, this got in the way of seeing things.

It got in the way of ever saying anything spontaneous. It got in the way of ever saying anything spontaneous.

But with this tic I had a chance of being safe. From bulrushes, from the durr-durrs of the Dirt Police, and from being Moses. And I realise now that I thought I was keeping her safe too. Because if I was dirty, she was dirty. Whereas if I got gold stars, she got gold stars too.

I was saving her. What a precocious, narcissistic hero I was! Sons – especially only sons – are such complicated monsters. Later, I learned that sentences don’t save anyone. No sentence can have any kind of completeness. No utterance, no representation, no statue, no poem, no art of any kind, can make any claim to be whole or perfect, nor make any claim to convey any kind of total truth.

But Michelangelo believed that Art might, in his hands, do all of those things. Michelangelo once carved a marble ribbon – a diagonal assertion between The Blessed Virgin’s breasts – in his Pietà of 1500, and he carved it with the following words:

MIHEL.A(N)GELUS.BUONAROTUS.FLOREN.FACIEBA

Michelangelo Buonarroti of Florence was making this.

Pliny tells us that classical artists signed their works with ‘faciebat’ – ‘he was making’ – ‘he was in the process of making’ – NOT with ‘fecit’, meaning ‘he made’ – thereby suggesting that the work in question, though apparently finished, was still in process, not yet complete, not yet perfect. It could never be so in the eyes of the gods. It was a gesture of humility. Michelangelo goes one step further and leaves off the final ‘T’ of ‘FACIEBAT’ – wryly drawing attention to the work’s

‘unfinishedness’, and therefore to his own humility before God. Even the word he’s carved stops short of being perfect. As everything, in the end, stops short. But how humble is he being? Michelangelo was the first Renaissance artist to write ‘faciebat’ on a work. By doing so he’s making an explicit connection between himself and those artists of ancient Rome and Athens whom he so admired. So, he’s making a show of being humble. And he’s also saying:

I’m Michelangelo. I’m 25 years old. This is my family. A once-noble family which will be noble again. This is my proof.

Let the sensuous depth of this drapery deepen your devotions! I have learned all I can from Leonardo and now behold! How I surpass him!

I’m the inheritor of the glories of our glorious past. Look!

This is my legacy. I’m here. I’ve arrived. Look!

Michelangelo’s mother died when he was six. I wonder if, as he carved the Virgin Mary of the Pietà, first with the point chisel, perpendicularly into her heart, making stone burst out from it and become space; and then with the tooth chisel, obliquely teasing softness and form into what was left, and then with a metal rasp, finely grinding that illusion of serene pliancy into the texture of her skin – I wonder if, as he was doing all of these things, he was becoming a little boy again.

A little boy resurrecting his mother. Bringing her back.

A little boy resurrecting his mother. Bringing her back.

Yes, I’ve been broken-hearted Blue since the day we parted Why, why, did I ever let you go?

Photo by CJ Deocareza

If I See A Lone Magpie, There’s Another Nearby Gail Webb

One for sorrow, he says, to keep me still, expressionless. I yearn for another, a silver-white, black-jacketed partner in abandoned towns, or ivy-clad ghost tree.

Two for joy, they tangle and twist in rhyme, cling on the deadwood like eager devils, then gone in proverbial puffs of smoke. Praters, short-lived darts, mercurial shots.

Three for a girl, alive or dead. Often they saunter into view, glisten blue-black, jewels, feathers, found bright things, then darkness catches up, scythes time from under locked feet.

Four for a boy, fanfares full of new hopes, a future faces forward, faces backward, sorrows are swept along in joy’s current, we’ve got this, our grief becomes time to change.

River Trent Bridie Squires

I mistake the sound of a fire engine for a waterfall.

A single magpie crosses my path for the fifth time this week.

My phone tries to turn my words into an emoji; I feel frustrated because I know what I am talking about.

A passing runner’s breath is deep and heavy. My sweat slowly gathers on the inside of a fresh jumper.

Faint voices chatter behind, talking about school and life and being big enough to manage all these things eventually.

When I die, I won’t be dead. I’ll be swimming in the pools of whisky on the Big Rock Candy Mountain, catching joke flipping bottles with Grandad, picking at a plate of salmon with Cleo, listening to the sparrows from Iremongers Pond in their migration chorus.

The purple flowers I don’t know the name of are blooming full today hanging over the edge of the concrete walls clinging to hope like springtime.

A Night on the Channel

Paul Liedvogel

Darkness fell upon the English Channel much as it had for as long as Sid remembered – slowly but without hesitation, black pulling down from the sky, pulling up from the sea, until the two merged, shyly, at an invisible horizon.

Yes, Sid thought, he would miss the nights on the Channel most of all; miss the trawlers solemnly drifting behind their searchlights; miss the glimmer of distant coasts like velvet stitching; miss the waves furiously, incessantly pounding against the ship’s steel carcass – he could guess at them now, looking down without seeing, far below, could sense them under the engine’s subtle vibrations, travelling through his legs and into his body and on to somewhere beyond.

He felt whole then, uniquely whole, and he would forget about an aching back or worn knees or the foul smell of scallops fresh off the Channel’s bed, the kind that you might never rid yourself of again.

Sid was sixty-six years old.

With a sharp whine, the winches atop the deck began to move, signalling the end of another towing cycle and, from out of the dark, the dredge appeared, water trailing its nets.

Sid tugged hard on the rope connecting to the dredge, the hemp burning hot underneath his gloves, steering the nets to where they would be emptied.

Soon, scallops flooded the deck and with them came that old familiar scent of sediment, and tang, and brackish waters, deep and without light – Sid often wondered about this place below, where the scallops fed and the Channel bore its secret scars.

He hunched down as the dredge circled away. He felt water enter his boots, and his gloved fingers dug into the scallops, shucking the shells, chucking the meat, the muscle,

through hatches into the ship’s hungry belly.

Fifty years, Sid thought, fifty years, and soon: no more.

But even as he thought it, even as his fingers worked through the scallops with the experience of a young man grown old, he could not imagine himself away from the trawlers, and the rain, and the cold, and the chilling clattering of scallop against scallop on the trawler’s open deck.

He did not truly believe ‘Sid’ existed away from the trawlers, and if he had voted one way or another in the past, then only because of the scallops, and the Channel, and the integrity of British waters, and he had nothing against immigrants, not he, but, o, the scallops!

The regular rhythm pulsing through Sid’s body, the crashing of waves and grinding of machinery, suddenly changed.

Sid looked up from the scallops and through the ship’s railing onto the darkly undulating sea. A cool breeze blew off the land that, tonight, lay invisibly in the far distance, spurring the waves – they began to lap against the side of the ship strangely and erratically.

Like something is drifting in our wake, Sid thought, like two waves running counter to each other.

He narrowed his eyes, concerned.

Then, he caught sight of the dinghy – it tottered on the edge of darkness, entering and exiting the world of the trawlers and scallops every other second. An onboard motor ran at the dinghy’s back, but it struggled in the trawler’s wake.

Figures huddled together on the dinghy; shadow and sluggish motion, and the blink of an eye in some rogue ray of light.

Sid called out to the other deckhands; the dinghy was pulled over the dark edge; somewhere up in the wheelhouse, a radio began to broadcast.

Listening to the radio’s crackle, to its waves bouncing off the night sky and deep Channel floor, travelling, travelling, travelling home, he felt, with certainty, this dinghy would not be found, would not arrive anywhere, and again his thoughts drifted, as by themselves, to that place below, where

the scallops fed. He closed his eyes, and in the dark he found the single eye still looking at him. It blinked – hopeful – then shut closed.

Tulip Thieves

Nathan Curnow

Touching tulips is a sadness

– Claire Miranda Roberts

Now all the garden’s overcome with dark the tulip thieves return, cursing themselves forever cultivating botanical doom. Like propellers through the flower beds, cows in the orchestra, they tramp at night, digging misery, strong-arming their haul of petals, vandalising for the glory of what they must deserve – sadness, as inevitable as war, suffering as self-cure.

To arrest themselves in wanting they choke the Orphean flame, sowing soil with absence –a tropism they can’t escape. They know frost in the morning means sun in the afternoon.

A hole freshly discovered is certain to be filled. Sabotage is never-ending as dip-darting microbats watch with ears, sound boarding plunder beneath the figs. The woe can be no winning, a stripped prize as their torches fade and they bundle back toward their cars before the traffic starts. At dawn they will remove their coats,

rest their spades beside the door, to mull again the broken cups. The stigma and the pistil.

*The first line of ‘Tulip Thieves’ comes directly from ‘Naming the Stars’, a poem written by Judith Wright in 1963.

Arecibo Observatory

Nathan Curnow

Because they were scared they put 10 million dollars into a karst sinkhole in the jungle.

They built a giant dish 1,000 feet-wide for tracking nukes in the ionosphere.

Cuba had happened, who could blame them? The eye stared up and out, its rim skirted by a teeming canopy –the coqui called and the coqui called back.

Meanwhile the stars in their bingo, the stars in their radio play, shone into the dish as the Gregorian dome rode the length of its azimuth rail.

They saw pulsars, asteroids, gravitational waves, ice on Mercury and mountains on Venus. They sent a message in binary that takes 25,000 years to reach whoever’s not there to read it.

Their fear chanced them upon an awe machine that stared past the threat they invented, into chaos, order and deep time until it snapped and the cathedral crumbled. The jungle was waiting, not waiting, not impatient for 50 years, its gravity dropping back into the hole, mealing on itself.

Now – the fruit bats, woodpeckers, the Wild Wist the mongoose and Emerald birds.

A diamond-eyed boa smells its long way out on a branch above the broken rim, its magnificence snaking the dense air, reaching a long, dead end.

It nests in concentric knowledge, folded like space and time. The coqui call. ‘Co’ is a warning, the ‘Kee’ means the call goes on.

The Dream Audit

Andrew Tucker Leavis

David Pashton MP had posted something overnight which –to judge by the panicked apology now pinned to his timeline – he firmly insisted he had not written.

‘Hacked,’ the note said. ‘Appalling content. Not me at all. Deeply sorry.’

He sat in the conservatory watching his favourite robin in the birdbath, waiting sombrely for the call from Comms.

‘Which final straw is this?’ said the spin doctor, when the call arrived.

‘Fourth or fifth, I should think,’ said David, ‘though for once, I wasn’t actually conscious.’

‘When are you conscious?’ said the spin doctor. ‘The trouble is, they believe it’s the sort of thing you’d think. And, in a way, they’re not wrong.’

‘But I don’t think it,’ said David, helplessly. National Scandal was towering over him: he felt like a man starting to towel-dry a shipwreck.

‘Can I remind you that this is exactly what we’ve been trying not to do?’

‘I know it is. I’m aware, so go on then. Throw me your life jacket.’

There followed a cough, dry and procedural.

‘We’ll need to prove you don’t have unconscious bias. The Danish Social Democrats are doing this thing — it’s clever and Nordic. It’s called dream auditing.’

‘Very funny!’

‘No. Earclips arrive Monday. You wear them at night and they analyse your dreams for unconscious bias. Transparency is how we do things. That’s very us.’

‘Hmm.’

‘Not very you, but there we are.’

The earclips did arrive on the Monday, in a tightly sealed box. They were amniotic white, faintly anatomical, like cockle shells or something dredged from the seabed. David read the instruction booklet in English, then French for good measure. They would, he was informed, analyse both his theta and delta waves, and crossreference any troubling patterns found therein against the National Intolerance Database. It all seemed fairly kosher.

‘Very dashing,’ said Barbara drolly, as he checked in the bathroom mirror that they were properly affixed.

‘They’re cutting-edge.’

‘So were lobotomies,’ she said, ‘once upon a time.’

Blameful phone calls had wearied him. He sat on the bed and glimpsed a memory of his hand resting on Tony Benn’s shoulder at the Hucknall Men’s Club, the air hot with embassy smoke. The fight had escaped him. He rationed two glasses of Château Pontet-Canet for himself and fell into a blameless sleep.

In the morning he forgot to take the clips off until he caught his reflection in the gleam of the Guardian homepage.

‘OPINION: Pashton apologised. The problem is, the left heard him the first time.’

News of his blunder had billowed outwards and upwards, and he was now being condemned to a kitchen-based exile. He digested the thinkpiece, then replied at length to a constituent who was convinced of alien life in Basingstoke. Both matters remained unresolved.

His secretary turned down most interviews, but he was finally sold on ‘Good Morning With E. J. Velassi’.

‘Mr. Pashton,’ said the quiffed presenter, ‘just last week you said you were “proud to represent one of the most progressive constituencies in the Midlands.” Is there a sense that you’re letting your voters down?’

‘Only in that I didn’t set a strong enough password. I shouldn’t have put my birthday in it, I’ll give you that. As you can tell by my birthday, I’m old enough to have known better.’

Photo by Claudio Arnese

Afterwards, David scratched the make-up out of his jowls. He had joined the movement in his teens to strip the smug look off the face of his piano teacher…well, there had been some other impulse. Where was it? He took a taxi from the studio; the radio station was in Arabic; his shoulders felt heavy.

But the white earclips were weightless. They played music to him, his daughter’s recording of the Goldberg Variations. He wore the earclips every night for a week. Whatever dreams they appraised – like the vivid image of his father watching him on television through his binoculars – were, by morning, forgotten.

On Sunday, David was in the conservatory again, sitting in his handwoven wicker chair, when the dog started barking at the front door. He put down the Sudoku compendium, walked through the hallway and grabbed the cockapoo’s collar with a penitentiary grip.

A striking man stood in the rain which was falling upon the doorstep. He had a clean buzzcut and an off-the-rack suit worn over a white T-shirt with a picture of a turtle in the centre. Straightening his cuffs, the man smiled at the crusading snout poking through the door.

‘Sorry,’ said David, gesturing dogwards, ‘she doesn’t know what to make of strangers.’

‘No worries at all. My name’s Adam,’ said the person in the cheap suit, ‘I’m the dream auditor.’

‘Oh come in, come in.’

David led the auditor past the landscape paintings to the conservatory, where he offered his guest a lemon balm tea and the broad rustic panorama.

‘I’m from nearby,’ said Adam, ‘Barnby, actually.’

‘What a dairy they have there,’ David replied, ‘And I like the farm shop. With the honesty box.’

‘It has its moments. I don’t come back often.’

The kettle boiled and they watched the robin submerge itself partially. Adam extracted a white laptop from his bag

and rested it on his knees. Then another device emerged, an aluminium cradle which the auditor plugged into the wall.

‘Right-o,’ said David haltingly, ‘what do you need from me?’

‘I can take a reading from the clips,’ said Adam, scratching a cheekbone, ‘and your neural responses will do some ballet with our bias-weighted interpretive model. Then I’ll compile some early data to give you an impression. Won’t take a minute, then you’ll be in the “tofu-eating wokerati” with us again, in no time.’

David gave a shielding smile. He took the box, which seemed heavier than before, from the mantelpiece, then handed the white earclips to the auditor and returned to his chair.

‘And so you have my soul to weigh,” said David with mock portent, ‘omnia mea mecum porto. Now who said that? I can’t remember,’ He sat and rapped two fingers on the wicker. Adam’s fingers rapped too on the laptop keys. In the kitchen, the dog was coughing.

‘Have you ever taken your own medicine then, Adam?’ said David, ‘Your dreams are audited, I suppose?’

‘I guess it’d be hypocritical not to,’ Adam blinked heavily.

Outside, the pigeons had returned to the fence, assessing the favoured robin in the birdbath.

‘And just what form of report should I expect? A slideshow? Interpretive dance?’

‘I mean, there are a range of output displays. You can get as granular as you like with it. It’s modelling your nighttime activity now.’

‘I have to confess some scepticism on my part,’ said David, ‘though I’ve been sleeping as well as ever – or better.’

‘Good. We’d always try to be non-invasive.’

‘Although I’m still damned if I know how what you’re doing is of any use.’

‘My job is to provide your employer,’ said Adam, now looking up at David over the laptop, ‘with a professional opinion as to whether you have an unconscious bias against a marginalised group. It’s not a trivial thing to do. That was

a hell of a tweet from someone on our side.’

Two more pigeons flew down from the roof. David took an alleviating sip of hibiscus and let the powerlessness wash over him for a minute.

‘Marginalised,’ said the MP, ‘is a funny word, isn’t it. It seems that you read about the marginalised all the time. So then it seems that the margins are actually in the middle of everything…’

‘Should we not be?’ said Adam, with a studied neutrality, resting his right hand briefly on the breast of his suit jacket.

The pigeons were now crowding the birdbath, eating all the food that David had thrown.

‘You see, I didn’t quite mean…’

David noticed again the screenprint on Adam’s shirt, and the auditor saw. He pinched a switch on the cradle, then pulled his blazer to one side and pointed to the image of the turtle swimming.

‘Have you heard of Urashima Tarō?’ said Adam.

‘No. Is he on the bench at Chelsea?’

‘He’s a Japanese fisherman, from mythology,’ said Adam. ‘A hero who goes to save a sea turtle. And his reward for this is a box of forbidden jewels.’

Harried by the larger birds, the robin flew up to the fence.

‘...when Urashima opens the box of jewels, there’s a catch, of course: he turns instantly into an old man. Then the story ends very suddenly.’

‘I like those lessons in being humble,’ the young auditor continued, his head turning towards the subject of his study, ‘you see them across all cultures. That’s always a struggle I have; knowing when to keep the box closed.’

In his mind David saw his father beating his fist at the Trade Union Conference. He had fought four elections to be remonstrated like a child, by a child.

Two of the pigeons spread their wings and tussled with each other. The robin had seen enough – it took off from the fence back into the sky.

Then the MP, red in the face, got up swiftly and walked

to the French window, sliding it open with such gusto that it set the dog off barking in the next room.

‘Damn pigeons! You’ve scared him off again.’ He clapped twice and the grey birds fled. ‘Of course, I shouldn’t say damn, Adam. I oughtn’t be insensitive to those who’ve had their souls condemned.’

Adam tilted the laptop lid down. ‘Everybody’s read your message, David. Our one selling point is that we’re supposed to be better than them. Do you know how long it took me to get out of a place like this?’

‘This village is quite lovely.’

‘Yes, well, people said things like your tweet to me. Every day of the week, people I knew. It made me sick to read it. And here I am again: on the cusp of the technological singularity, dragged out into the fucking countryside.’

‘It was a hack,’ said David, ‘I didn’t write anything.’

‘Nobody does! “It was an AI forgery, an impressionist from Channel 4.” That doesn’t mean shit,’ said Adam, ‘because people believe that you wrote it. And what do you think that says about you?’

A noise of breezy completion came from the laptop’s speaker. David felt himself coursing with the adrenaline he’d had as a younger man, when he’d gone against the whip on Iraq.

‘And suppose I had written it, Adam. You’re young; I’m not. We built this country on turn-the-other-cheek. You say “we” with your hand to your heart, but so do I. We were gentle, but we could stand to hear words we disliked. There was a place for you, even with your background. There was a place for everyone. Was there not?’

David’s throat was tight. Adam’s face settled in sober triumph.

‘Except – no place for me it seems, and it does seem like I’m old news and that I’m on the way out. All of this is on the way out. And I didn’t tweet it, but people believe that I would, and that’s because it’s true – that I don’t see anything wrong with saying it. There wouldn’t have been, twenty years

ago, or even ten. And you’re going to end my career, aren’t you, because this me, me, me-too tedium crept up on this party, and I was surrounded in the night. Goodbye, David Pashton.’

He sat down. He had opened the box and he was ancient now. There was a pause, in which both of them felt the cold air drawn in from the open window. A moment fell upon the room: of gentle understanding, in which they watched over one another, father and son after a row. The wind stirred the garden grass and the silence became softly-marked with foreboding, with fingerprints on a guillotine. The birdbath was empty.

‘Out with it then, Adam,’ said David, finally. ‘Give me the verdict.’

Difficult rainbows filled the screen: measurements and opaque readouts. Adam studied these entrails, consulted his professional expertise, then closed the lid softly.

‘Oh, David. I can’t tell you. But the party will be in touch.’

Cash for Bombs

Nicholas Hogg

The Army offered cash for bombs in Kandahar, buying up rockets and rounds from the locals, the anti-tank missile

Made in Britain, gleaming off the line in Bolton. Once the venture had launched, an old man came to the base with a fire extinguisher painted green. The guard tapped the casing with his gun, the cardboard fins glued to the metal. Good bomb, said the man, plying his wares. Very big bang. The squaddie at the gate got nervous, feathering a trigger. The man smiled. How many Dollar? The guard laughed. Bring us a real one first, mate. They waved him away with a muzzle, watching as he walked down the hill. Fucking chancer, said the lad from Bath. Two days later on patrol, the ordinance buried in the road, beneath the armour-plated chassis. The inch-thick steel that would rip like tin.

Torvill and Dean Nicholas Hogg

Jane Torvill and Christopher Dean are not married, explains my mother, as they stand on the ice together. She talks and cooks, peels back the lid from a tin of sardines. The telly glows. My father eats dinner at another house.

When they kneel, and the Bolero plays, Jane circles Christopher, a centrifuge in lilac. Their sleeves begin to ripple, like wings in flight, and Jane, like a chiffon scarf, wraps her body around his chest.

Yet she is the one in control, even when she is held above the cold hard rink, as they lean into the dance, and into each other, attaining something (I am told) more lasting and precious than love.

Satellite

Nicholas Hogg

I was skipping down a rock like a goat in Nike, when I stepped off a drop into clear blue space. I waited for the fall, for the sound of bones that snap like cane. I saw the Old Town frieze, the chock-a-block streets now hushed and still. As if I had time enough left for a look towards the peak. Sitting in the air like a man might read in a wingback chair. Flying in a poem on a page. Not smashing into shale that broke like glass, crashing on a hill like a drunk. Before I got up dazed and held my head. Baffled by it all. The position of feet and sky.

Photo by Ashley Gallant

And Still, the Sun Shines

Jib Tran