2023 — 2026

2023 — 2026

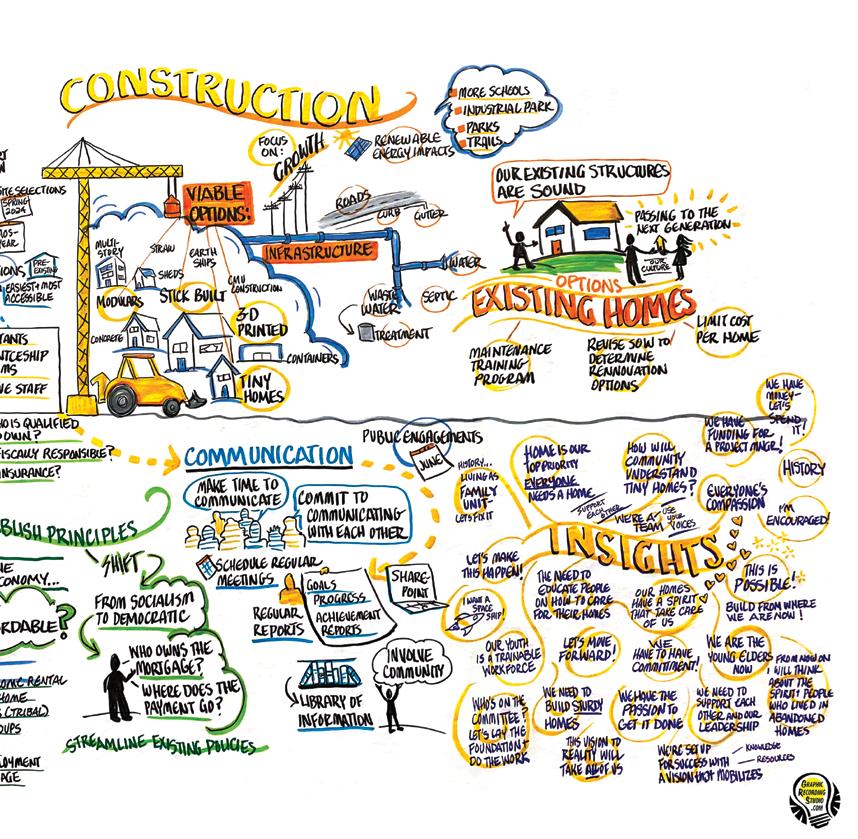

The three-day “NUCHU: Planning Our Vision” event was held in August 2023, with tribal representatives, funding partners, and consultants brainstorming opportunities to sustainably blend need and opportunity while honoring and respecting tribal culture and traditions.

According to tribal histories, the Ute people have lived in the mountains and vast areas of present-day Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arizona since the beginning of time. Today, the Ute are divided among three reservations, the Uintah-Ouray in northeastern Utah, the Southern Ute in Colorado, and the Ute Mountain Ute in Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico. Sharing common heritage and ancestry, but separated by hundreds of miles, the three Ute groups have established separate “sister tribes” that are independently governed but coordinate to support all Ute whenever possible.

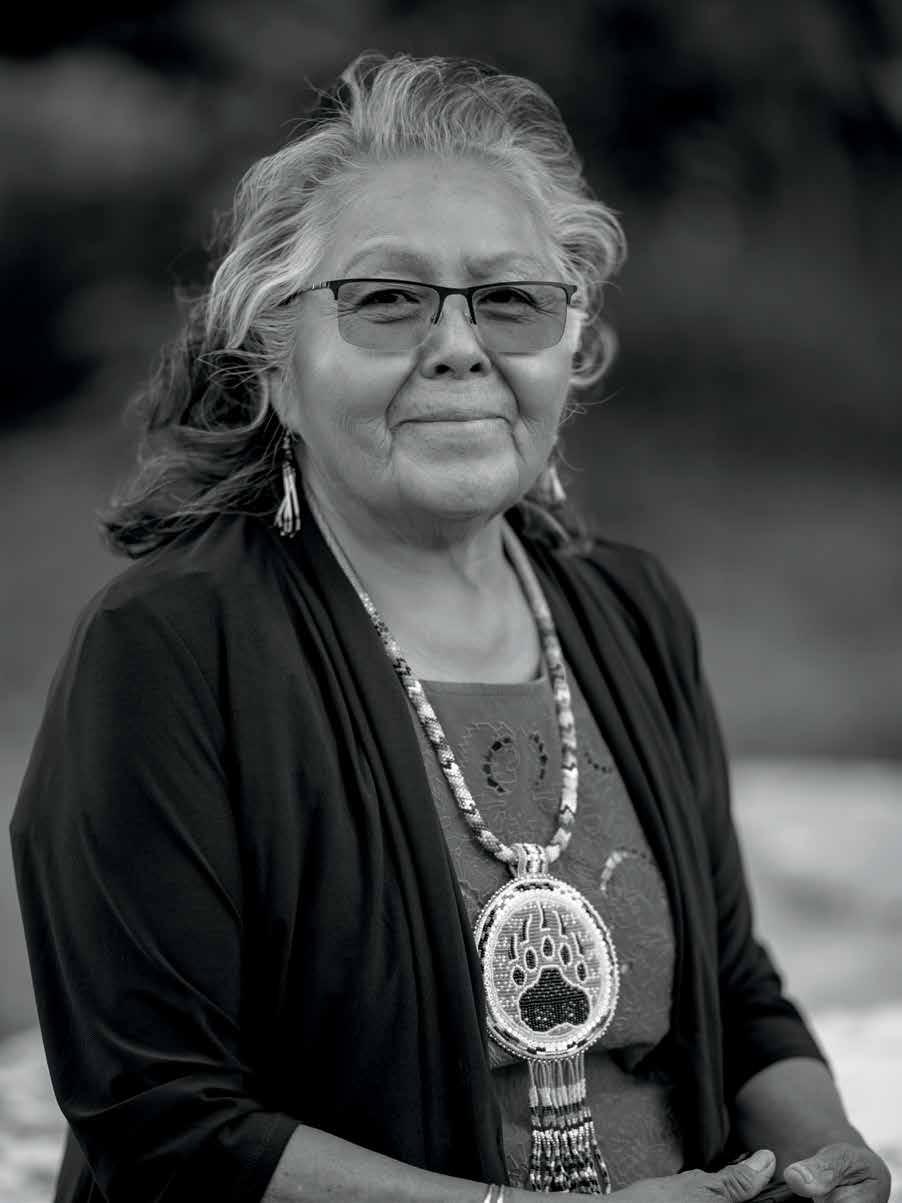

Like many tribal communities nationwide, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) reports high levels of poverty, low levels of education, and unemployment rates that double state averages. Teen birth rates are among the highest in the nation, addiction and behavioral health challenges are serious social ills, and the average life expectancy continues to hover at just 55 years. The 2,100 UMUT members face a severe housing shortage, and a shortage of water, healthy food, quality healthcare, educational opportunities, and high paying jobs. The UMUT believes that the most effective and sustainable pathway towards a brighter future is the reclamation of the rich and nuanced traditions, history, and language of the Ute People.

To proactively seek partnership and funding to address deep-rooted economic and social challenges, UMUT hosted the firstever Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Native National Partnership Retreat in 2015, bringing state, federal and private funding partners together to understand the comprehensive needs of the Tribe and help refine tribally designed solutions to align with current funding opportunities. Forty funding partners attended the event, and UMUT has leveraged their active participation into more than $140 million in new grants over the past eight years.

As recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic continues to realign priorities and needs, it was time again to meet and coordinate with state, federal, and private partners.

NUCHU: Planning Our Vision was held in August 2023, with over 50 funding partners in attendance. The three-day event allowed UMUT leadership and tribal members to explain current priorities and potential strategies. Together, the assembled group of tribal representatives, funding partners, and consultants brainstormed opportunities to sustainably blend need and opportunity while honoring and respecting tribal culture and traditions. UMUT hopes to generate $240 million in new funding over the next five years as a result of this important work.

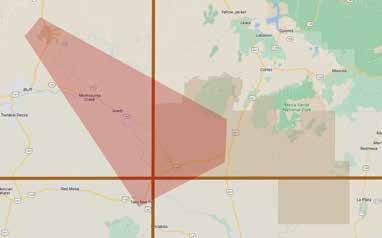

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s reservation is in Montezuma County, Colorado and San Juan County, Utah. The Ute Mountain Ute people have lived on this land for over 100 years. Today, the homelands for the Weeminuche, or Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, total about 600,000 acres. The tribal lands are on what’s known as the Colorado Plateau, a high desert area with deep canyons carved through the mesas. Towaoc is secreted away southwest of Mesa Verde National Park and northeast of scenic Monument Valley. Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) has a membership of about 2,100. Most Tribal members live on the reservation in Towaoc, with a smaller population in the White Mesa community. This is a harsh, isolated land, with no nearby cities to provide specialty services for the residents living on tribal lands. There is a severe housing shortage, widespread poverty, a shortage of water, healthy food, quality healthcare and educational opportunities and high paying jobs. Over 40% of the population live in poverty and the average

life expectancy is only 55 years in comparison to 76 years in the United States. The purpose of the 2023 Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Native National Partnership Retreat called NUCHU: Planning Our Vision was to build relationships with state, federal, and private funding partners to help identify resources to address these challenges. Eight major capital projects were prioritized and planned to be “shovel ready” in preparation for funding opportunities that will become available in the next five years.

As Planning Director for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Interim Economic Development Specialist, my job is to plan major infrastructure projects that will benefit our tribal members. One of my job responsibilities is to administer a five-year Partnership Planning Grant funded by the U.S. Economic Development Administration (EDA) and produce a Comprehensive Economic Strategies Plan (CEDS) that serves as a means to engage community leaders, leverage the involvement of the private sector, and establish a strategic blueprint for regional, state, and federal collaboration. As such, I was honored to work with Chairman Heart, Reiner Lomb, and Beverly Santicola to design and develop the Tribe’s second Native National Partnership Retreat called NUCHU: Planning Our Vision. We designed NUCHU: Planning Our Vision to produce a tribally-driven plan to build capacity and guide the economic prosperity and resiliency of the Tribe and its neighbors. Since a large percentage of UMUT members live in poverty, all eight projects included in this 2023-2025 CEDS and planned at our Retreat on August 1-3, 2023 address the following ten root causes of poverty and their unique impact on the members of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and their children: 1) lack of employment opportunities; 2) lack of quality in education and workforce development; 3) unaffordable and unattainable housing; 4) insufficient transportation options; 5) disproportionate health access and outcomes; 6) lack of consistent access to nutritionally adequate and safe foods; 7) inaccessible and unaffordable childcare; 8) unsafe environments; 9) imbalanced outcomes in the criminal justice system; and 10) lack of recognition and access within a community.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) is a federally recognized tribe. The UMUT Tribal constitution was adopted in 1940. The Tribe is governed by a seven-member elected council including a Chairman. One council member represents White Mesa, and the other members are elected at-large. The Chairman’s council seat is one of the seven seats elected through popular vote for a three-year term. The position of Vice Chairman is held by an elected Councilman, which is selected every year by the Chairman. The Tribal Council Treasurer is an elected Councilman voted annually by the Tribal Council members. Current members and officers of Tribal Council are:

Chairman manuel.heart@utemountain.org

Darwin Whiteman, Jr. Secretary darwin.whiteman.jr@utemountain.org

Turtle Treasurer alston.turtle@utemountain.org

Selwyn Whiteskunk Vice Chairman selwyn.whiteskunk@utemountain.org

Lyndreth Wall, Sr. Counciman lyndreth.wall@utemountain.org

Malcolm Lehi White Mesa Councilman malcolm.lehi@utemountain.org

Conrad Jacket Councilman conrad.jacket@utemountain.org

The tribal government administration is headed by a Tribal Council–appointed Executive Director, Chief Financial Officer and Legal Counsel. Government offices and facilities are concentrated in and around the community of Towaoc, although there are some government offices in White Mesa. The Tribal Administration Department provides administrative support services for tribal members and employees of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. Members of the Executive Leadership Team include:

John Trocheck Executive Director jtrocheck@utemountain.org

Ronald Scott Chief Financial Officer rscott@utemountain.org

Peter Ortego Legal Counsel portego@utemountain.org

In all matters, the Tribe is a sovereign nation and determines its own course of action. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council, subject to all restrictions in the Constitution and by-laws and the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, has the right and powers to oversee the following:

■ Executing contracts and agreements

■ Engaging in business enterprise development

■ Managing Tribal real and personal property

■ Negotiating and agreeing to Tribal loans and financial instruments

■ Enacting and enforcing ordinances to promote public peace, safety and welfare

The Tribe is structured as a Federal Corporation that may be used for business purposes in developing financial growth and Tribal economy. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Government Offices are headquartered in Towaoc, Colorado, 15 miles south of Cortez, Colorado, on US Highway 491/160 in Montezuma County, Colorado. The fact that the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation lies in different states can add complexity relative to political dealings, however, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is a sovereign nation and has an agreeable relationship with the states. All Tribal lands are trust lands, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council has full authority and jurisdiction regarding all issues in the political geography.

Bernadette Cuthair Planning Director bcuthair@utemountain.org

John Trocheck Executive Director jtrocheck@utemountain.org

Ronald Scott Chief Financial Officer rscott@utemountain.org

Lee Trabaudo

UMUT Public Works/ Broadband ltrabaudo@utemountain.org

Dyllon Mills

Kwiyagat Community Academy Dmills@utekca.org

Dan Porter Kwiyagat Community Academy Dporter@utekca.org

Nicki Green Legal Counsel ngreen@utemountain.org

Scott Clow Environmental Director sclow@utemountain.org

Patrick Littlebear Grants & Contracts Administrator plittlebear@utemountain.org

Marie Heart Staff Development Coordinator mlansing@utemountain.org

James Melvin

Weeminuche Construction Authority jmelvin@wcaconstruction.com

Miles Sturdevant

Weeminuche Construction Authority msturdevant@wcaconstruction.com

Joe Lopez

Weeminuche Construction Authority jlopez@wcaconstruction.com

Ben Elmore

Weeminuche Construction Authority belmore@wcaconstruction.com

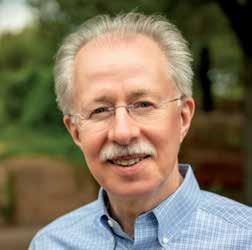

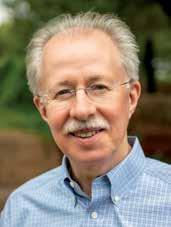

Beverly Santicola is an award-winning film producer, social entrepreneur, idea generator, problem solver, program developer, project facilitator, public speaker, and grant writing consultant. Over the past ten years Santicola has focused her expertise and energy in the arenas of community development and collaborative partnership building for Native American Tribes. Working with a team of professional grant writers that have generated more than ONE BILLION in grant funding for clients and more than $140 million for the UMUT, she has been nationally recognized for social innovation and leadership excellence by the US Department of Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs, as well as Encore. org as a 2010 and 2014 Purpose Prize Fellow sponsored by the Atlantic Philanthropies and John Templeton Foundation.

Amanda Shepler has more than seventeen years of grant writing experience working full time with a wide variety of clients including Tribal Governments, School Districts, Institutes of Higher Education, Charter Schools, Municipalities, Community Based Agencies and more. She has personally won more than $100M in grants and assisted the Santicola & Company Team to win over one billion in grants. Amanda earned a Master’s Degree in History from Buffalo State College in 2006 and Bachelor of Science in Social Studies Education in 2003. Past work experience includes Substitute Teacher (2 years); Program Coordinator of Boys and Girls Club (8 years); President of Kiwanis of Tonawanda (2 years); and Board Member for Boys and Girls Club of the Northtowns (2 years). She is married with four school age children and lives in Tonawanda, New York.

Anthony Two Moons is an Indigenous artist and photographer of Arapaho, A:Shiwi and Diné lineages. Following his studies he started his career in New York City as a fashion photographer, and continues today as a photographer and director based in New York and working everywhere. His work has appeared in publications around the world. He is the author of multiple award winning books, including Growing Ute: Preserving The Language and Culture, volumes 1 & 2, and Wíssiv Káav Tüvüpüa (Ute Mountain Lands). Anthony recognizes the extraordinary privilege and abundance of knowledge he has gained while working with exceptional talent and experienced individuals throughout his career. As an Indigenous professional photographer and artist, equity plays a vital role in Anthony Two Moons’ work with Indigenous communities.

Sara earned a Master Degree of Public Administration from the University of Colorado in 2015, and a Bachelor of Science Degree in Business Management from Oklahoma State University. She worked for Colorado Health Foundation from 2010 to 2022 where she created multi-million dollar funding initiatives for strategic priorities. She brings her passions for health equity, building organizations, and creative problem solving. She began working with CROPS in 2016 and led the first partnerships between CHF and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. Sara currently serves as Executive Director of CROPS — a nonprofit 501c3, that helps the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe in its capacity building efforts.

Marc H. Santicola is a retired Financial / Accounting executive with over 40 years of experience in manufacturing and the energy industry. He held various Controllership and Director of Finance positions with Fortune 500 companies (Schlumberger, Cameron International, Cooper Industries, Smith International) at the corporate, divisional and plant levels working in executive leadership, project management, financial planning, systems implementation, organizational restructuring, and divestiture. Marc holds a MBA degree from the University of Pittsburgh and is now working as a consultant with NeoFiber on the Tribe’s $40M Broadband Initiative..

The Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) contributes to effective economic development in America’s communities and regions through a place-based, regionally driven economic development planning process. Economic development planning – as implemented through the CEDS – is not only a cornerstone of the U.S. Economic Development Administration’s (EDA) programs, but successfully serves as a means to engage community leaders, leverage the involvement of the private sector, and establish a strategic blueprint for regional collaboration. The CEDS provides the capacity-building foundation by which the public sector, working in conjunction with other economic actors (individuals, firms, industries), creates the environment for regional economic prosperity.

Simply put, a CEDS is a strategy-driven plan for regional economic development. A CEDS is the result of a regionally-owned planning process designed to build capacity and guide the economic prosperity and resiliency of an area or region. It is a key component in establishing and maintaining a robust economic ecosystem by helping to build regional capacity (through hard and soft infrastructure) that contributes to individual, firm, and community success. The CEDS provides a vehicle for individuals, organizations, local governments, institutes of learning, and private industry to engage in a meaningful conversation and debate about what capacity building efforts would best serve economic development in the region.

From the regulations governing the CEDS (see 13 C.F.R. § 303.7), the following sections must be included in the CEDS document:

■ Summary Background: A summary background of the economic conditions of the region;

■ SWOT Analysis: An in-depth analysis of regional strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats; (commonly known as a “SWOT” analysis)

■ Strategic Direction/Action Plan: The strategic direction and action plan should build on findings from the SWOT analysis and incorporate/integrate elements from other regional plans (e.g., land use and transportation, workforce development, etc.) where appropriate as determined by the EDD or community/region engaged in development of the CEDS. The action plan should also identify the stakeholder(s) responsible for implementation, timetables, and opportunities for the integrated use of other local, state, and federal funds;

■ Evaluation Framework: Performance measures used to evaluate the organization’s implementation of the CEDS and impact on the regional economy.

www.eda.gov/resources/comprehensive-economic-development-strategy

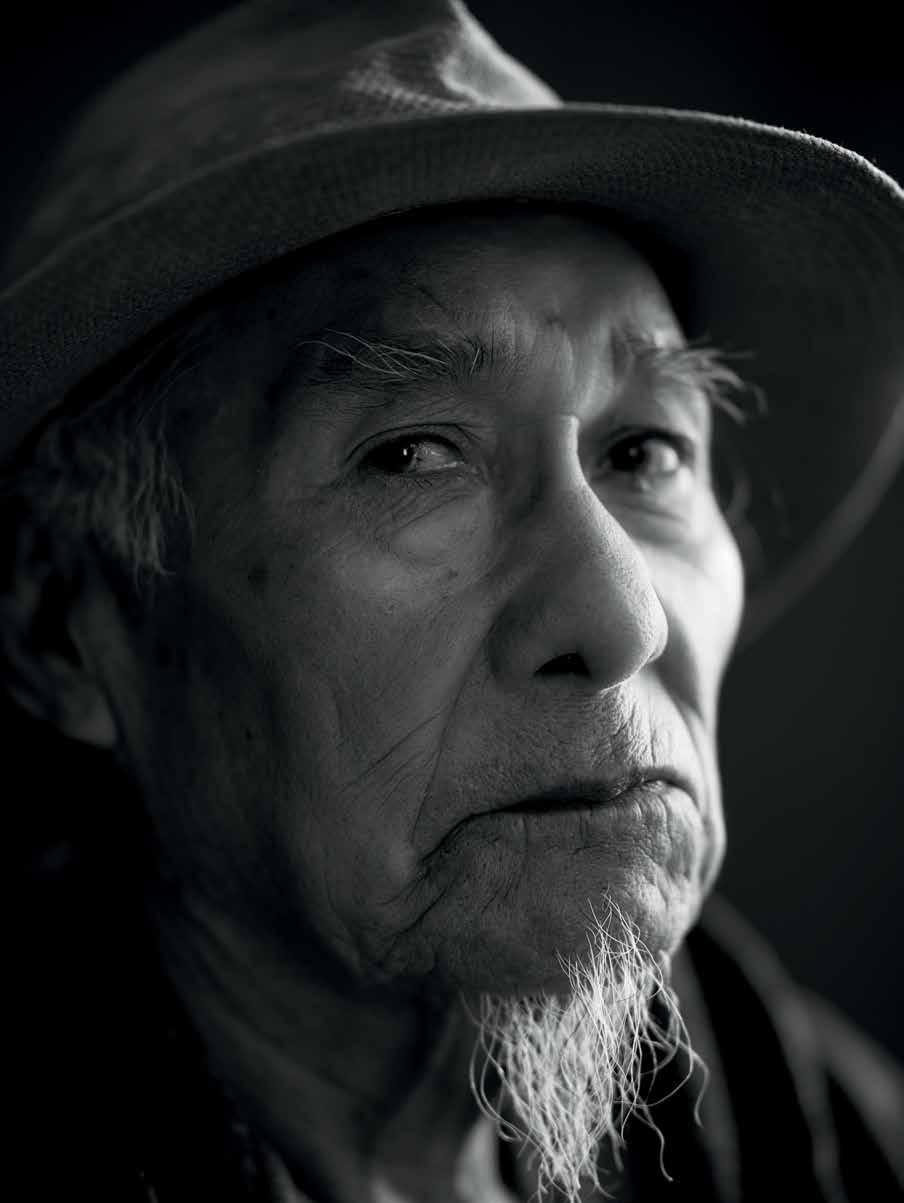

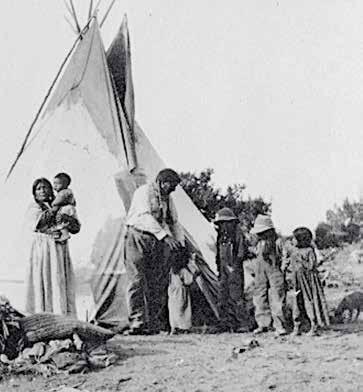

Historically, the people of the Ute Nation roamed throughout Colorado, Utah, northern Arizona and New Mexico in a hunter-gatherer society, moving with the seasons for the best hunting and harvesting. In the late 1800’s, treaties with the United States forced them to move into Southwestern Colorado. Currently there are three Ute tribes— the Northern Ute Tribe in Northeast Utah, the Southern Ute Tribe in Southwestern Colorado and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe (UMUT) in Montezuma County (Towaoc), Colorado and San Juan County (White Mesa), Utah.

The UMUT people have lived on this land for over 100 years. Today, the homelands for the Weeminuche, or Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, are slightly less than 600,000 acres. The Tribal lands are on what’s known as the Colorado Plateau, a high desert area with deep canyons carved through the mesas. Towaoc is located southwest of Mesa Verde National Park and northeast of scenic Monument Valley.

In addition to the land in Colorado and New Mexico, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe also has a presence in southeastern Utah, on allotted trust land. These lands, or allotments, cover 2,597 acres and are located at Allen Canyon and the greater Cottonwood Wash area as well as on White Mesa and in Cross Canyon. Some of the allotments in White Mesa and Allen Canyon are individually owned and some are owned by the Tribe as a whole. The Allen Canyon allotments are located twelve miles west of Blanding, Utah and adjacent to the Manti La Sal National Forest. The White Mesa allotments are located nine miles south of Blanding, Utah. The Tribe also holds fee patent title to 41,112 acres of land in Utah and Colorado.

Tribal lands also include the Ute Mountain Tribal Park, which covers approximately 125,000 acres of land along the Mancos River. Hundreds of surface sites, cliff dwellings, petroglyphs and wall paintings of Ancestral Puebloan and Ute cultures are preserved in the park. Native American tour guides provide background information about the people, culture and history who lived in the park lands. National Geographic Traveler chose it as one of “80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century,” one of only nine places selected in the United States.

Topographically, the UMUT Reservation is characterized as a high desert plateau, with the elevation ranging from 4,600 feet along the San Juan River to 9,977 on Ute Peak. Vegetation ranges from sagebrush shrubs in the lower elevations to ponderosa pine forests in the higher elevations. The Reservation includes six vegetation zones, including semi-desert grassland, sagebrush savanna, pinyon juniper woodland, mountain, chaparral, and ponderosa pine-fir-spruce-aspen. Approximately 3,800 acres of noncommercial timber forests are represented in these vegetation zones. The Reservation contains verified or potential habitat for several federally listed species of plants and animals.

National Geographic Traveler chose the Ute Mountain Tribal Park as one of “80 World Destinations for Travel in the 21st Century,” one of only nine places selected in the United States.

Reports indicate that the Ute Mountain Ute land, as late as the 1870s, contained grasses, harvestable as hay in non-wooded areas, with sagebrush sparse or absent. This condition was changed by heavy grazing, in part due to encroachment from non-Indian livestock. Overgrazing resulted in serious range depletion, with invasion or increase of sagebrush and other undesirable species, the cutting of gullies and arroyos in the lowlands, and severe erosion in the uplands.

Later reductions in livestock numbers have resulted in partial recovery of some reservation and surrounding rangelands. The Livestock Grazing Program within the Natural Resources Department was established to assist Tribal member cattlemen in developing and maintaining the best possible herds for their families.

The climate of Four Corners region is classified as semiarid and is characterized by low humidity, cold winters, and wide variations in seasonal and diurnal temperatures. Temperature varies with elevation. The average monthly maximum temperature ranges from 39°F to 86°F, and the average monthly minimum temperature ranges from 18°F to 57°F. The highest and lowest temperatures occur in July and January, respectively. Precipitation also varies with elevation, with average annual precipitation amounts of 8 to 10 inches in the lower elevations of the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation and about 13 inches at Cortez (Butler et al., 1995). The 50-year (1948 through 1997) annual precipitation minimum was approximately 5.2 inches at Cortez (1989) and the 50year maximum was 30.8 inches at Mesa Verde National Park (1957) (EarthInfo, Inc., 2000). Average monthly precipitation varies from 0.65 inch in June to 2.00 inches in August. At the higher elevations, the monthly precipitation totals are relatively constant throughout the year with the exception of the dry season, which occurs in April, May, and June. At lower elevations, a relatively drier season occurs from April through June and a relatively wetter season occurs from August through October. Summer precipitation is characterized by brief and heavy thunderstorms. The snowfall season lasts for 7 to 8 months with the heaviest snowfall occurring in December.

Source: www.weatherwx.com/climate-averages/co/ute+mountain+indian+reservation.html

In the Four Corners region, rangeland and forest account for roughly 85 percent of the entire area, as well as the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe reservation. Primary land uses on the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation include housing for tribal members, tribal offices, natural gas, sand and gravel extraction, grazing for Tribal livestock, and business enterprises that provide jobs for its people including the following:

| www.utemtn.com

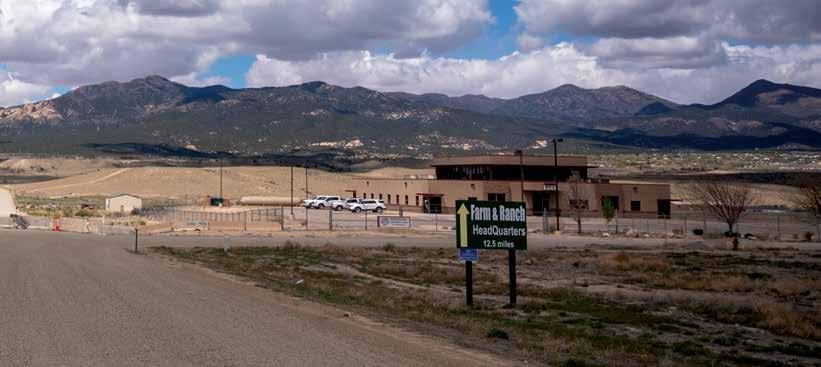

Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Farm & Ranch Enterprise is a 7,700-acre productive, modern irrigated agricultural project nestled below the Sleeping Ute Mountain on Ute Mountain Ute Tribe Land in the southwest corner of Colorado. As good stewards of the land, the Tribe practice sustainable farming and use state of the art technology to grow and mill corn without GMOs. Cattle, alfalfa, and more is also raised. A majority of the farm has been dedicated to the production of alfalfa for hay. Farm & Ranch Enterprise has an excellent reputation for producing and delivering high quality alfalfa hay. All alfalfa hay produced is tested for quality enabling the customer to receive exactly what was ordered. Alfalfa bales are 3/4-ton 3x4x8 foot bales and are either stored in hay barns or under tarps immediately after baling. Care is taken in selection of good hybrid varieties of corn that thrive in this climate. Farm & Ranch has consistently ranked high in both state and national corn yield contests sponsored by the National Corn Growers Association. A modern 500,000-bushel storage facility enables Farm & Ranch to store and market grains as market situations become favorable. Ute Mountain Farm & Ranch’s source of irrigation water is the McPhee Reservoir, Colorado’s second largest man-made reservoir. Irrigation water travels 40+ miles in open canals and through siphons to reach the Farm. The reservoir is fed by the Dolores River, a tributary of the Colorado River. Although the Ute Mountain Ute, as a tribal nation, has principal water rights to this water, the Colorado River is currently overallocated and experiencing a steady long-term decline in annual flows that is affecting the entire region. This is additionally impacted by ongoing climate trends predicting warmer, drier seasons for the Four Corners area due to the geographic and meteorological location west of the Rocky Mountains. It then is guided through underground laterals to a total of 109 pivot sprinklers. Because of the elevation difference between the canal and the fields, pressure is developed as it travels to the fields enabling the use of pivot sprinklers. Modern technology enables us to monitor all irrigation systems by use of computers and cell phones in real time. Water in the southwest is a precious commodity and the efficient use of this resource is of top priority.

| utemountaincasino.com

Ute Mountain Casino Hotel is a property of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. Located in Towaoc, Colorado it’s the state’s first tribal gaming facility. The casino gaming floor is packed with over 700 slot machines, Vegas-style table games, the best Bingo Hall in Colorado, and a brandnew Sportsbook. Located 20 minutes from the entrance to Mesa Verde National Park and nestled in the shadow of the legendary Sleeping Ute Mountain, the Hotel offers Southwestern hospitality, great food, and gaming excitement! The Hotel at Ute Mountain has 90 comfortable and newly renovated rooms including Full Suites, Junior Suites, Spa Suites, a swimming pool, and a workout facility.

| wcaconstruction.com

Located in Towaoc, Colorado, WCA Construction (WCA) is a wholly owned economic enterprise of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. As a Tribal enterprise WCA is dedicated to the employment, training, and development of vocational skills for tribal members and Native Americans. This policy has resulted in approximately 70% of WCA’s total workforce being Native American. WCA is a certified Indian Small Business Economic Enterprise, HUBZone, and 8(a) contractor. Additionally, WCA is a licensed contractor in civil and building trades in Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. WCA’s aggregate bonding capacity is $100 million dollars with projects typically ranging in size from as small as $250,000 up to $50 Million. As a general contractor, WCA provides construction and design/build services for the public (Federal, State, and Tribal), and private clients throughout the Southwest. Our construction management team and Colorado-based support staff have diverse experience in all phases of construction and related engineering disciplines. In addition to our construction management team, WCA staff also includes a licensed civil engineer, licensed land surveyor, and WCA holds an explosives license with the ATF. WCA’s crews have completed a wide range of construction projects including heavy civil, water resources, commercial and residential buildings.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe are the Weenuche band of the Ute Nation of Indians. The two other bands, the Mouche and the Capote became the Southern Ute Tribe. The Northern Ute Bands (the Uncompahgre band, the Grand River band, the Yampa band, and the Uinta band) are located on the Uinta Ouray Reservation near Vernal, Utah. The Ute Indians are distinguished by the Ute language, which is Shoshonean, a branch of the Uto-Aztecan linguistic stock (Garcia and Tripp, 1977). Other Indians in the United States that speak Shoshonean are the Paiute, Goshute, Shoshone, and several California Tribes.

The Ute are proud and resilient people. They have an intimate knowledge of the land and a strong connection to their ancestors. An unbridled spirit and optimism drive them to address the challenges they face utilizing the assets, resources and power they have as a community.

According to the US Census, the population of Towaoc, Colorado in 2020 was 1,140 with 61% female and 39% male; the median resident age was 22.6, in comparison to 36.9 years for the rest of Colorado. The town of White Mesa, Utah is home for just 138 residents and is demographically similar to Towaoc, with local residents being characterized by high degrees of poverty and rural isolation (the nearest city with a population of 50,000 or more is nearly 200 miles away). Youth under age 18 constitute more than half the resident population at the UMUT Reservation, virtually double the proportion found in most American communities. The number of children and youth tribal members and non-tribal members is 600. The total UMUT population between the two regions is 1,318 (63% of total UMUT membership).

In 2010, the population in Towaoc, CO was 932, representing a 22% increase over the last ten years. The population of White Mesa decreased from 228 to 138 people. Total UMUT membership remained fairly stable at 2,100.

The overall Tribal population on the UMUT Reservation is expected to remain consistent for the foreseeable future. The current blood quantum requirement for tribal membership is 50%. Considerations for lowering the blood quantum requirement for membership have not yet been decided.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe people are determined to preserve and protect their culture and language. Two ceremonies have dominated Ute social and religious life: the Bear Dance and the Sun Dance. The former is indigenous to the Ute and aboriginally was held in the spring to coincide with the emergence of the bear from hibernation. The dancing, which was mostly done by couples, propitiated bears to increase hunting and sexual prowess. The theme of rebirth and fertility is pervasive throughout.

The Sun Dance was borrowed from the Plains tribes between 1880 and 1890. This ceremony, for men only, is held in mid-summer, and the dancing lasts for four days and nights. The emphasis of the Sun Dance was on individual or community esteem and welfare, and its adoption was symptomatic of the feelings of despair held by the Indians at that time. Participants often hoped for a vision or cures for the sick.

Consistent with the emphasis of this ceremony was the fact that dancing was by individuals rather than couples as was the case with the Bear Dance. Both ceremonies continue to be held by the Ute, although the timing of the Bear Dance tends to be later in the year.

The Ute enjoy singing and many songs are specific to the Bear Dance and healing. The style of singing is reminiscent of Plains groups. Singing and dancing for entertainment continue to be important.

Over the past eight years the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has produced award-winning books, films, language apps, and websites. In all the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has won more than 50 Telly, Anthem, and Webby Awards for these productions.

Ute Online E-Learning nuuwayga.com/

Ute Online Dictionary dictionary.utelanguage.org

Ute Language Google App play.google.com/store/apps/ details?id=org.utelanguage. dictionary

Ute Language Apple App apps.apple.com/us/app/ute-mobiledictionary/id1594696386

AND LANGUAGE BOOKS

Growing Ute I

issuu.com/a2moons/docs/ growingute_issuu_1028

Growing Ute II

issuu.com/bevsanticola/ docs/growingute2

Land Changes

issuu.com/bevsanticola/ docs/wi_ssiv_ka_av_tu_ vu_pu_a_08sept

Grocery Store Capital Campaign

issuu.com/bevsanticola/docs/ cc_14june

issuu.com/bevsanticola/docs/ ceds_2022_0601_digital

Retreat Report

issuu.com/bevsanticola/docs/umut_ nuchu_report_prf10

“Our Culture is Our Strength” Film vimeo.com/516856356

“We Are Nuchu” Film vimeo.com/617401273/6cb4761591

“Escape” Film

www.centerforruraloutreach.org/projects-gallery/ escape-film

“The Strength of Siblings” Film

www.centerforruraloutreach.org/projects-gallery/ the-strength-of-siblings-film

PSAS

Suicide PSAs | vimeo.com/661599488 vimeo.com/661599524

Language PSA | vimeo.com/624082360/c1bf5dddb3

Culture PSA | vimeo.com/521216390

The UMUT annual operating budget, approved September 28, 2023, for FY 2024 is $104,555,097, of which 79% comes from grants and contracts and the balance comes from other revenue sources. Revenue from business enterprises has been lower in recent years following COVID and the severe drought.

The Farm and Ranch Enterprise was operating at 20% capacity for an extended period. Increasing costs for materials and labor has adversely affected Weeminuche Construction Authority and the Tribe lost significant revenues from gas and oil. Tribal revenues from its business enterprises are expected to increase in 2024-2025.

Each revenue source contributes to the Tribe’s ability to function as Tribal government. Any increase in revenues results in an increase in services and improves the quality of life for Tribal members. On the other hand, any decrease in revenues severely limits the Tribe’s ability to provide Tribal members with adequate services and social programs, basic living assistance and improved living conditions. Current Grants and Contracts represent over 79% of the tribe’s revenue. The Tribe is listed by the Internal Revenue Services in Revenue Procedure 2002-64 as an organization that may be treated as a governmental entity in accordance with Section 7871. As such, the Tribe’s income is not subject to federal income tax.

Since 2015, following the first Ute Mountain Ute Native National Partnership Retreat, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has generated more than $140 MILLION in new grant funding. The Tribe contracts with Santicola and Company to assist in the development of award-winning proposals.

One quarter of UMUT residents live below the poverty level and unemployment is more than double the state’s unemployment rate. Nearly one-in-three children on the UMUT reservation live in poverty. The estimated median household income in Towaoc is $27,656 in comparison to $75,231 in Colorado. The per capita income of $22,558 in White Mesa is about three quarters of the rest of the state $30,986 and unemployment is more than double the state rate (10.1% versus 4.8%).

One-in-three children on the reservation live in poverty

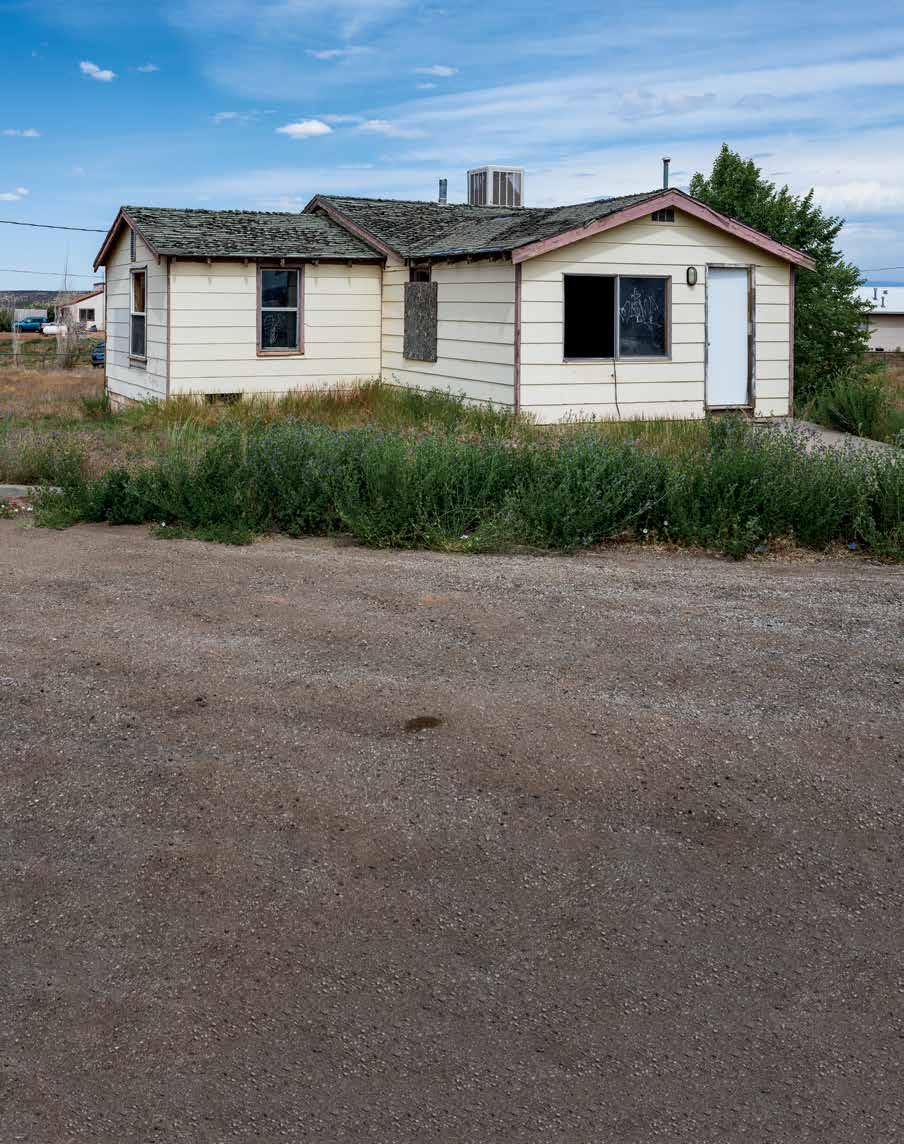

The housing shortage on UMUT lands is devastating. Families WANT to live on the reservation to take advantage of tribal benefits such as proximity to family support systems and tribal services such as health care, social services, and cultural programs. As of April 14, 2023 there are no properties to buy or rent at any price on the UMUT reservation. Housing in the communities immediately

surrounding UMUT lands are beyond the financial means of Tribal members. To solve this challenge, families “double up,” sometimes reaching four separate families living in the same structure. The current list of families awaiting affordable housing opportunities includes applications from 2008, 2009, 2011, and 2013 – families that have been living in unsafe, overcrowded conditions for over a decade. The aging housing stock of the UMUT reservation further complicates this issue, leaving families in homes with leaking roofs, faulty wiring, broken gutters, and plumbing challenges that lead to mold. In 2019, the Colorado Health Foundation (CHF), Colorado Housing and Finance Authority (CHFA), and Colorado Department of Local Affairs (DOLA) donated $300,000 each for a total of $900,000 in hopes the tribe could make emergency health and safety repairs to 12 homes at approximately $75,000 per home. The Bureau of Indian Affairs Tiwahe Initiative also granted $734,604 over three years for housing improvements. Eighteen homes were renovated for a total of $1.3M and one additional home will be completed in FY 2023. The average cost per home is $80K and some have exceeded $140K. See table below:

The Tribe envisions prioritizing building high-quality, multi-generational housing to retain elders/disabled persons in their home through a Tribal Care System. This is expected to bring additional cost advantages considering it costs $5,000+ per month to maintain an elder or disabled person in a nursing or rehabilitation facility.

The USDA defines “Food Desert” as a tract in which at least 100 households are located more than one-half mile from the nearest supermarket and have no vehicle access, or where at least 500 people or 33% of the population live more than 20 miles from the nearest supermarket, regardless of vehicle availability. Both UMUT Reservation communities of Towaoc and White Mesa qualify as food deserts, which the USDA defines as parts of the country with low levels of access to fresh fruit, vegetables, and other healthful whole foods, usually found in impoverished areas. Tribal residents in Towaoc must travel 20 miles or more to reach the nearest full-service grocery store. This distance is difficult for all Tribal members, but particularly devastating for the 32% of residents who utilize SNAP benefits to purchase groceries. The only option for food in Towaoc is the Travel Center, which sells food typical of an interstate truck stop, or at the Casino Hotel.

People with diabetes have 2.3X higher annual medical costs than people without diabetes, with an average of $9,601 in diabetes-related expenses per year.

The Center for Disease Control reports Native Americans have a greater chance of having diabetes than any other US racial group.1 The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe serves a Native American population battling obesity, prediabetic conditions, and Type II diabetes at rates far greater than any other subpopulation in the nation. Across the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation, obesity impacts entire families and burdens children with unhealthy lifestyle habits before they reach their 10th birthday. Young adults are diagnosed with preventable Type II diabetes before they reach middle age, and Elders struggle to self-monitor and maintain healthy A1C levels. Without access to fresh foods and healthy ingredients needed to prevent and address diabetes among the older generations, younger generations do not build the knowledge, skills, and habits they need to prevent diabetes, creating an intergenerational successive pattern that continues to intensify.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe reports a life expectancy of 55 years – more than 20 years fewer than the average American. The 2016 UMUT Community Health Assessment states one in four tribal members have Type II Diabetes. Over 70% of adults and 50% of youth are struggling with obesity.

The best practice to prevent and manage Type II diabetes is to maintain a healthy diet. Research shows that grocery stores with abundant fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, and low-fat dairy products result in healthier choices for consumers. Diabetes Journal reports that a person diagnosed with diabetes at age 40 will have $211,400 additional lifetime medical expenses. The estimated lifetime cost of treating and living with diabetes for an individual who has had diabetes for 50 years is $395,000. In 50 years, 500 Tribal members with diabetes will spend a collective $197.5M on treatment alone. This robs the Tribe of collective resources which could be better spent on healthy food, education, and higher quality of life.

The root causes of health disparities related to diabetes among the Ute Mountain Ute are complex and intrinsically linked to the history of Native Americans in modern America. Solutions must be equally comprehensive and culturally specific. Devastating health challenges related to widespread obesity, prediabetic conditions, and diabetes can be overcome.

1 https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aian-diabetes/index.html

In Fall 2021, 63% of parents of Native American students indicated they do not believe “All student’s cultures are acknowledged and respected in school.”

On a national scale, Native Americans lag in attainment of higher education. For example, only 16% attain a degree compared with 33% country wide. Similarly, only 5% of UMUT Tribal members have a bachelor’s degree or higher compared to 35% in the state of Utah and 42% in Colorado. Further 76% of Tribal members have a high school diploma compared to 93% in the state of Utah and 92% in Colorado. Though a substantial number report having attended some college, the graduation rates remain stagnant (SWCAHEC).

At this time, the vast majority of UMUT children are bused to Montezuma Cortez schools, a journey that can take nearly an hour in each direction. Against all standard measures, Ute students demonstrate a desperate need for culturally aligned educational options. For generations, traditional public-school assessments have shown Ute youth are far behind non-tribal peers in academic performance. The Montezuma Cortez School District RE-1 Report on the Progress of American Indian Students from October 2021 shows the following statistics:

ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF UMUT CHILDREN ■ VERSUS NON-TRIBAL AFFILIATED STUDENTS ■

of all student suspensions

Although Montezuma Cortez School District RE-1 offers K-12 education, approximately 33% of UMUT high school students attend various boarding schools around the county, such as Riverside Indian School in Anadarko, Oklahoma, due to suspensions and a need for alternative options. The Kwiyagat Community Academy (KCA) Charter School provides an alternative to the county’s schools by offering a curriculum interwoven with Ute history and culture. The school is focused on individual connection in small classroom settings with many outdoor experiences and hands-on learning practices.

Students at public schools say they are bullied and treated as second-class citizens. The public school system is primarily interested in “using the tribal students or tribe” as a number to substantiate a need for more grant funding and programs rather than providing real help. Native American students who are failing will often drop out or in some cases, actually pushed out, whereby they have little alternative except to pursue GED certificates rather than pursue high school diplomas and must contend with the dropout stigma in pursuit of higher education. Caught in the stigma of low self-esteem, many Indian students continue their downward spiral applying for entry-level jobs at either the Tribal casinos or one of the other enterprises/departments within the Tribe. Individuals and families suffer from the effects of educational under-attainment, extensive drug and alcohol abuse, domestic violence and crime. UMUT Tribal Human Resources reports show that Tribal workers are too heavily under-educated. Of the 657 Tribal members and other Native Americans currently working full-time for the Tribe, approximately 250 have not completed a secondary diploma. Based on temporary worker intake forms, the number of adults lacking a secondary-level diploma in Towaoc is as high as 600. Poor overall academic proficiency levels and extraordinarily low high school graduation rates among UMUT youth are further indicators of this critical lack of college and career-readiness.

There can be little doubt that the current educational system is failing Ute children.

As noted, both UMUT Tribal communities are highly rural with no nearby population centers that offer college degree or industry certification opportunities. While 2017 survey results show that community members are nearly unanimous (91%) in agreement that some form of post-secondary education is essential for personal and/or Tribal economic uplift, the lack of public transit and too few personal vehicles (estimated at one operable vehicle for every four work-age adults) make commuting to a college or training center unusually difficult, costly, and stressful. Further, 80–90% of high school graduates don’t have the financial means or transportation to attend college. And while the Tribal Council provides fully funded scholarships, many students are emotionally or academically unprepared for it. The distance from the Tribal reservation to qualified post-secondary institutions, workforce centers, or educational nonprofits are in the range of 25 to 65 miles — with no intermediary services between. The nearest accredited internship program is more than 70 miles away in New Mexico. Even when these facilities are reached, the resources often prove extremely limited in scale or reliability, due to fiscal starvation. To combat these challenges, the UMUT is coordinating with the Statewide Transportation Advisory Committee (STAC), the Southwest Regional Transportation Planning Commission (SWTPR), and the Colorado Department of Transportation ti identify opportunities to support transportation to local colleges for tribal members.

80–90%

of high school graduates don’t have the financial means or transportation to attend college

According to a 2015 education-related survey of UMUT Tribal residents 43% say that lacking funds for childcare has prevented their efforts to further their education. The most frequently cited reason from students who drop classes or trainings in Towaoc, according to follow-up calls, is “having to work so we could eat.” Among adults using Ute Mountain Learning Center resources, 92% of “currently-employed” participants reported they were seeking classes to improve their earnings potential and/or job standing (promotability). Fewer than 18% of respondents indicated that they were prepared for collegiate reading (and concomitant critical thinking) and less than 5% were ready for collegiate math.

Approximately 41% of Tribal members do not have health insurance. Teen birth rates are among the highest in the nation, and the likelihood of low birth weight is significantly higher than averages for other regions. Teen suicide has reached epidemic levels among the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. In August 2016, just one week into the new school year, the Tribe lost a high school Junior — a popular young man with a bright and promising future. In November 2016, the community lost another child to suicide, a young lady just beginning her high school career. In early 2020 there were two completed suicides and five attempts by teen girls and boys. Historically, UMUT sees an average of 2-5 youth suicides per year, but this doesn’t tell the whole story. Reported rates do not consider UMUT youth living OffReservation attempted suicides, drug overdoses, or those did not rule an “obvious” suicide.

Towaoc is a Medically Underserved Population (GOV MUP) and is also a designated Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA). Similarly, White Mesa is also a designated HPSA and MUP (score of 41, ID #03535) According to County Health Rankings and Roadmaps website www. countyhealthrankings.org, in terms of overall health outcomes, social and economic factors, both Montezuma County, Colorado and San Juan County, Utah rank poorly in comparison to other counties in their respective states. Key indicators are shown in the table above. Montezuma County and San Juan County report risk factors that are higher than state and national averages across a wide range of indicators. Ute Tribal Members live in communities where residents are far more likely to be in poor health, and to be without health insurance. For those who are insured, coverage doesn’t guarantee access to needed services. Living a long distance from providers, not being able to find providers who accept some insurer’s relatively low reimbursement levels or navigating the system to attain a referral and prove challenging to receiving treatment. The alarming concerns surrounding Native American child and adolescent health came into the spotlight upon President Obama’s visit to South Dakota’s Sioux tribe in 2014. The Department of Justice followed up with a report on his findings noting Native children’s unhealthy exposure to violence. This, combined with a toxic collection of pathologies — poverty, unemployment, domestic violence, sexual assault, alcoholism and drug addiction — has seeped into the lives of young people living on the UMUT Reservation. The report was followed by the White House’s 2014 Native Youth Report on the state of education in Indian Country. Combined, the reports reveal trends of overwhelming poverty, epidemic suicide, combat-level rates of PTSD, and low educational attainment amongst UMUT youth. To exemplify the severity of the issue, suicide is the second leading cause of death for Native youth aged 15-24 and occurs 2.5 times the national rate; 1 in 5 Native youth report having considered suicide.

Suicide among Native youth is 2.5 times the national rate.

Access to high-speed broadband internet on the UMUT Reservation is limited, at best. Accessibility issues are similar in both Towaoc and White Mesa. According to data obtained from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2017, 54.71% of the UMUT Reservation does not have access to any providers of broadband internet.

FCC figures show that only 45.29% of the UMUT Reservation has access to one or more broadband providers. No area of the Reservation has access to multiple providers. According to the FCC, the term broadband refers to high-speed Internet access that is always on and faster than the traditional dial-up access. Broadband includes several highspeed transmission technologies such as:

■ Digital Subscriber Line (DSL)

■ Cable Modem

■ Fiber

■ Wireless

■ Satellite

■

It is important to note that in 2015, the FCC tasked with overseeing the rules that govern the internet raised the standard for broadband to 25 megabits per second from 4 Mbps, while raising the upload speed to 3 Mbps from 1 Mbps. Using these new standards, no area of the UMUT Reservation has access to high-speed broadband internet. The lack of highspeed internet further exacerbates poverty, health and educational inequities because it limits access to distance learning and telemedicine services.

During COVID-19 UMUT students had to sit in cars in a parking lot to get homework assignments. A Comprehensive Broadband Plan was developed in 2020-2021 and is included in the Covid-19 Recovery and Resiliency Plan section of this Plan.

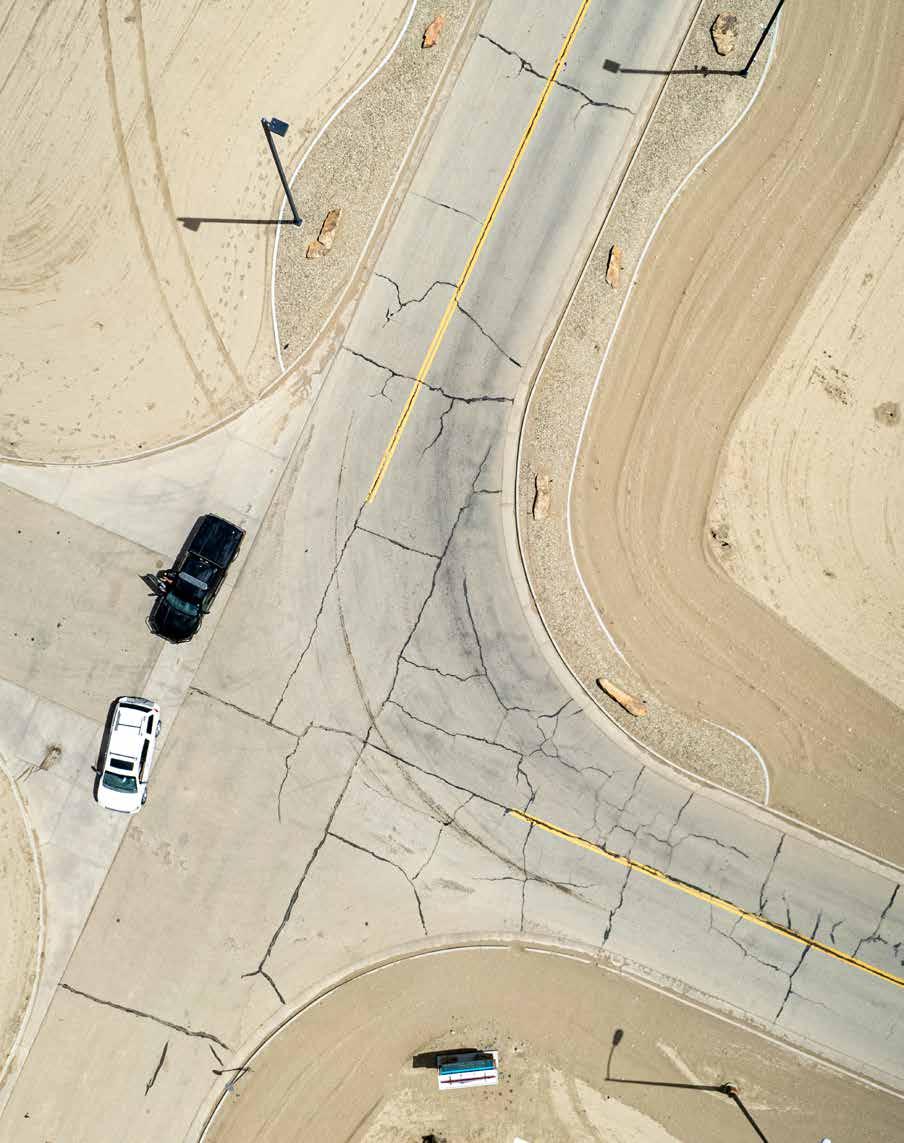

Transportation is limited on the Reservation with the main mode of transportation being the personal car and the Tribal transit system. The transit system consists of one van run on a fixed five-day schedule and the casino shuttle that delivers riders for employment purposes.

There is no easy way to get to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe reservation, and no easy way for tribal leaders to get to Denver or Washington, DC to meet with state and federal legislators and funding partners. In addition, there is no easy way for the Tribe’s 2,100 members to access many vital resources, specialty medical care, or educational opportunities. Even travel to the tribes Farm and Ranch Enterprise for employees and residents is more than 20 miles one way on a dirt road.

Towaoc is located in the southwest corner of Colorado, near the Four Corners Monument connecting the four states of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico and Arizona. The transportation network serving the region is limited due to topographical constraints, sparse population and the distance between urban areas. No interstate highway systems traverse the area; however, several interstate highways connect urban areas that have secondary feeder roads that serve the rural areas. These include Highway 491 north to Cortez and south to Shiprock and Gallup, New Mexico; Highway 160 to Teec Nos Pos, Flagstaff and Phoenix, Arizona; and Colorado Highway 41 to White Mesa and Blanding, Utah. Currently, no major railroad lines serve the region; the nearest being Gallup, New Mexico, 124 miles to the south. Small commercial airports are located in Cortez, Durango and Farmington, with even smaller limited-service airports located in other communities.

The Reservation is serviced by several logistically placed sewer lagoons and all wastewater is disposed into these lagoons. Recent expansion of the lagoons has increased service and long-term capabilities of the wastewater program. There were five major main supply breaks in 2016 alone along the 27 miles of pipeline connecting Towaoc to the water treatment facility in Cortez. Because the three-water tower/tanks in Towaoc can only store approximately 24 hours’ worth of water, this is a critical health issue on the reservation and served as a spark for an array of large and small-scale planned water infrastructure improvements.

The people living on the reservation in White Mesa, Utah have it even worse. On a highdesert bench overlooking Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah, what began as a mill built to break down rock and process natural uranium ore has become a commercial dumping ground for low-level radioactive wastes from contaminated sites across America and the world.

Haul trucks headed for the mill have splattered radioactive sludge along the route the children of the nearby Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s White Mesa Reservation community travel to school. Plumes of contaminants, including nitrate and chloroform, have been detected in the groundwater beneath the mill. The mill also emits radioactive and toxic air pollutants that can travel off-site, including radon, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxide.

For decades, the mill’s unconventional business model — pocketing $ millions in exchange for processing and disposing of hundreds of millions of pounds of radioactive waste — has

flown largely under the public’s radar. Piecing together the public records of these wastes connects the White Mesa Mill to some of the most infamously contaminated places in the country.

At the recent NUCHU: PLANNING OUR VISION Native National Partnership Retreat, one resident of White Mesa told over 50 funding partners the story of how the water in White Mesa has caused him and his wife serious health problems.

“My health and life expectancy has significantly been adversely impacted by the water in White Mesa and I worry that I won’t live long enough to see my children graduate from high school or dance at their weddings. My wife and I both have lumps on our bodies we never had before. I’ve had two back surgeries recently and need to use a scooter to get around.”

Although the Ute Mountain Ute, as a tribal nation, has principal water rights to this water, the Colorado River is currently over-allocated and experiencing a steady long-term decline in annual flows that is affecting the entire region. This is additionally impacted by ongoing climate trends predicting warmer, drier seasons for the Four Corners area due to the geographic and meteorological location west of the Rocky Mountains.

The following infrastructure initiatives were included in our Disaster Recovery and Resiliency Plan and have progressed significantly since our last CEDS report. These projects were prioritized to address the most critical issues on the reservation that are ‘shovel ready’ and can be implemented immediately with completion or partial completion in 12 months. Prioritization factors included the following:

1. Number of jobs created and retained

2. Environmental and sustainability factors

3. Number of people who will benefit from these improvements

There has been a family housing shortage on the UMUT Reservation of approximately 200 homes for over 20 years. The estimated $1M in funding allocated annually does not keep up with the growing needs of the Tribe. Many of the existing homes are in major disrepair. Multiple generations are living in one household in unsafe and unhealthy living conditions. The Tribe needs an estimated $25 million to build 100 new homes and repair 100 existing homes for its members. In the DISASTER RECOVERY AND RESILIENCY PLAN, the Tribe prioritized housing and began aggressively seeking funding to 1) repair homes; 2) construct new homes; and 3) build a housing factory on the reservation. In 2022 to 2023, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe decided to move the Housing Authority (TDHE) to a Housing Department under Tribal Council and the Executive Director. The table below shows grants awarded (or pending) to build homes in 2024-2025:

HUD

$2,000,000 5 duplexes (10 homes)

HUD $2,000,000 5-6 single family homes

CHFA

CHF

$500,000 Match for 5 duplexes above

$500,000 Invitation for housing funding in 2024

HUD $2,000,000 Congressional Directed Spending Request for Sober Living * * Pending but forwarded to Congress to be included in 2024 budget.

This project is ‘shovel ready’ and will create and retain at least 20-50 jobs.

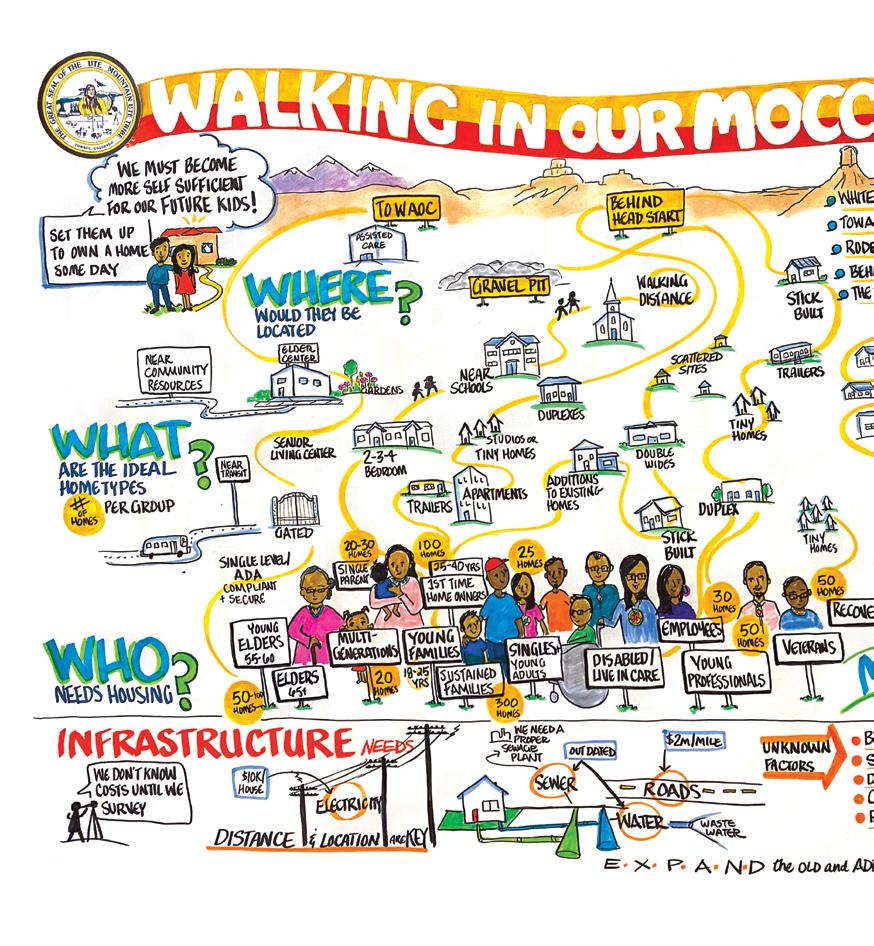

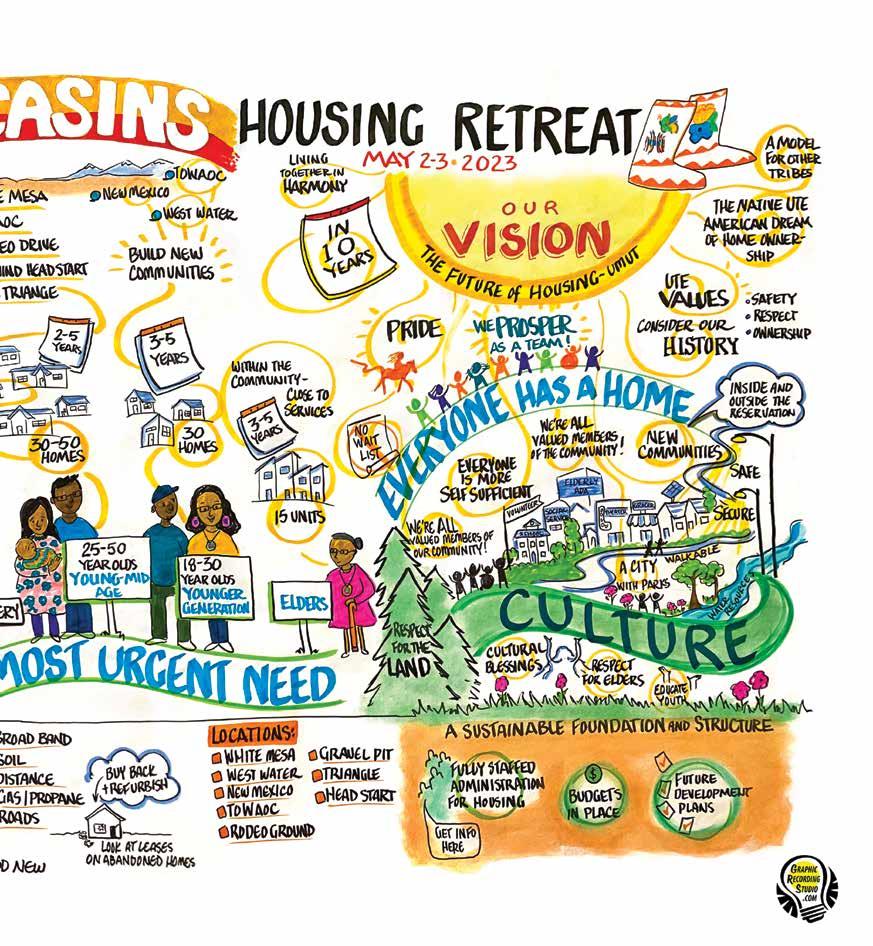

A Housing Retreat was conducted in May 2023 and the graphical recordings are below.

Kwiyagat Community Academy (KCA), a new charter school authorized by the Charter School Institute (CSI) in November 2020 and approved by the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Council in January 2021, opened in August 2021 with 27 kindergarten and first grade students. The opening of KCA marked the first time since the Indian Boarding School era of 1940’s a public school operated on the Ute Mountain Ute reservation. The school has a mission to “ensure an educational program where the Nuchiu (Ute) culture and language guides the educational experience and is characterized by small class sizes with an interdisciplinary, indigenous, and project-based approach that results in high academic expectations and desired character skills, personal wellness, and community involvement.”

KCA plans to grow by 15-20 students each year, adding one grade each year, until the school has between 90-120 students by the 2025-26 school year. Plans have been designed to not only build the school, but also construct an entire educational campus.

The project is ‘shovel ready’ and will create a minimum of 50 jobs.

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe developed a Broadband Plan and began applying for broadband grants during and following COVID. To date, the Tribe has generated over $40M with the technical assistance of Diane Kruse, CEO of Neo Fiber, Inc. The grants, purpose and maps for the broadband projects are below:

The project is ‘shovel ready’ and will create a minimum of 25 jobs.

Completed and led to nearly $40M in additional funding

• NDN Collective $50,000

• BIA/IEED National Tribal Broadband Initiative $49,800

• Economic Development Administration (EDA) $3.2M — Fiber from Cortez to Towaoc, CO

• State of CO Broadband Grant $3.5M — Fiber to all homes, businesses and Tribal facilities in Towaoc, CO

• Colorado Health Foundation $1.1M — Fiber to all homes, businesses and Tribal facilities in Towaoc, CO

• State of Colorado $9.8M — Fiber construction from Towaoc to the Tribal Visitor’s Center, and fiber to Mancos Creek, Rodeo Grounds new development and UMCE Building Improvements and Carrier Neutral Location facilities.

• National Telecommunications & Information Administration (NTIA) $22M — Fiber expansion in the 4 Corners Region, from the Tribal Visitor’s Center to Teec Nos Pas, Aneth UT, Farm and Ranch and fiber to all homes, businesses and Tribal facilities in White Mesa Utah.

State of CO/CHF — Fiber built to 424 homes, businesses and Tribal facilities within Towaoc

As a result of COVID-19 when it was challenging for members to access food off reservation, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe began working on a grocery store, workforce innovation center, and cultural space. The entire facility will be constructed in two phases. Phase I will break ground in fall of 2023 and will be resemble an open air market constructed of repurposed shipping containers. The market is anticipated to include the grocery store units along with WIC/SNAP/EBT registration, a makers space/cultural artifact museum, space for interaction with the Ute Language, Tribal Parks Tourism Office, a coffee shop, a commercial kitchen, and space to develop and support small, native owned businesses. Phase I construction is also envisioned to have vending locations for traditional vending activities and a large plaza for cultural activities and generational blending.

Once the Phase I grocery store is fully established and shows the anticipated growth potential, the Tribe will fund raise for the Phase II grocery store. The Phase II grocery store is anticipated to be approximately 6,000 SF and will function exactly like a small local grocery store. The units that contained the Phase I groceries will be repurposed into addition small business incubators.The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe has won over $5M in grants for Phase 1 of the Project and submitted a request of $2M to complete Phase 1 with Indian Community Development Block Grant. Groundbreaking and ribbon cutting events are scheduled for fall 2023.

CHF

$1,000,000

USDA LFPP

$198,112

Support for a food and economic incubator hub located on the reservation in Towaoc. The hub will be a source of healthy food, workforce training and entrepreneurship development, serving as a pathway to building a full-service grocery store. The hub will tart and grow Native-run businesses, including a produce stand/grocery, market provision, commercial ditchen, coffee shop, butcher/deli, classroom space, and a fabrication lab featuring light manufacturing equipment.

Support the development of a regional and native food supply chain through a feasibility study, implementation plan, and pilot project. It will also support the UMUT’s collaboration with producers and food system organizations in the Four Corners Region to source local healthy food for its members.

EDA

FNDI

Gates 1

Gates 2

USDA CFP

Harris & Frances

Reinvestment Fund

USDA RBDG

$2,929,574

$32,000

Develop a shipping container food and economic incubator hub to launch and grow many of the businesses that could later become pillars of the future grocery store.

Establish operations team for the Food and Economic Incubator Hub, hire Food System Coordinator and Program Manager, establish partnerships with food and farm businesses, begin Hub construction and design.

$15,000 Predevelopment planning support for the UMUT grocery store.

$75,000 FEED Towaoc food and economic incubator hub support.

$354,528 Develop grocery store, launch FEED Business Accelerator and Incubator Program, and strengthen community food system in Towaoc, surrounding region, and native country.

$25,000 Support the UMUT Food Sovereignty: Grocery Store, Native Food Incubator, and Indigenous Agriculture project.

$200,000 Pre-development for the grocery store, including community engagement, store design and layout, grocery store workforce development program design, and architectural designs.

$270,000

Total $5,099,214

Funding will support two major business development goals including 1) comlete a business plann for grocery store, 2) support organizational development in the form of technical assistance in marketing, store layout and eesign, and supply chain development, 3) conduct site planning and design for grocery store, and 4) conduct site engineering and environmental review for grocery store.

Phase I grocery store is in need of $1-2M to complete the designed build out and have operating capital.

Phase II grocery store can be ‘shovel ready’ with $15M in funding and will create an estimated 20-30 jobs.

Poverty rate: 22.8% (Utah 9.1%)

As noted, the town of Towaoc is in Montezuma County (Colorado) while the community of White Mesa is in San Juan County (Utah). A profile of the two counties is below.

The economy of San Juan County employs 5,702 people. San Juan County’s economy includes mining, quarrying, oil & gas extraction, agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, arts, entertainment and recreation. The largest areas of employment are in business, management, science & arts (1,850), service occupations (1,267), sales & office work (944), natural resources, construction & maintenance (868) and production, transportation & material moving (773). The median household income is $49,690 which is roughly twothirds of the amount in the state of Utah ($74,197).

Poverty rates are 22.8% which is more than double the rate in the state of Utah (9.1%). The income inequality of San Juan County (measured using the Gini index) is 0.48 which is higher than the state of Utah at 0.43.

The economy of Montezuma County employs 11,492 people. Montezuma County’s economy includes mining, quarrying, oil & gas extraction, agriculture, forestry, fishing, hunting, arts, entertainment and recreation. The largest areas of employment are in business, management, science & arts (3,703), service occupations (2,572), sales & office work (2,554), natural resources, construction & maintenance (1,603) and production, transportation & material moving (1,060). The median household income is $50,717 which is roughly two-thirds of the amount in the state of Colorado ($75,231).

Poverty rates are 12.4% which is twenty-seven percent higher than the state of Colorado (9.8%). The income inequality of Montezuma County (measured using the Gini index) is 0.42 which is lower than the state of Colorado at 0.46.

total land area: 2,029.53 square miles

population density: 12.6 individuals/square mile

population 2010: 25,541

population 2020: 26,266

population growth: +2.84%

The Southwest Colorado Region is also home to hundreds of nonprofit organizations. Annually, more than 450 tax-exempt organizations in Southwest Colorado file a Form 990 with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This number includes both organizations that are not 501(c)(3) and those with no revenue. Of these, about 180 501(c)(3) nonprofits in the region report annual revenue. Some organizations had millions in revenue, while others drew in a few hundred dollars. No matter the amount, each revenuereporting organization contributes to the regional economy. Collectively, these nonprofits have more than $20 million deposited in local banks and earned a combined $106,405,627 in revenue last year. Nonprofits in the region collectively employ more than 1,400 local residents.

Poverty rate: 12.4% (Colorado 9.8%)

AGE & GENDER DEMOGRAPHICS

Through its Farm and Ranch Enterprise (FRE), the Tribe currently has 7,640 acres under irrigation.

Deposits of sand and gravel are prolific and widespread throughout the reservation. Gravel is being extracted from several large operating pits for use as an aggregate source on the reservation for Tribal road construction. Production from these pits averages about 50,000 cubic yards per year. The Tribe is exploring the feasibility of developing a sand and gravel enterprise that could take advantage of the reserves commercially. Sand, gravel and bentonite reserves offer immediate economic rewards for such a Tribal enterprise. However, an inventory of Reservation reserves, a management program and a rotation of site use is necessary for planning and monitoring of these extractions to protect this valuable resource.

The Ute Mountain Ute range land resources are significant. Of the 553,008 acres of reservation lands in Colorado and New Mexico, approximately 429,234 acres are classified as range land suitable for livestock and approximately 123,774 acres are considered non-range land (barren land or river wash) or habitat for game only (rough, broken and very steep lands). The fee patent tract lands are defined as mountain ranches and provide summer range for livestock. The White Mesa and Allen Canyon allotments are classified as range land. The actual production value of Tribal range lands depends upon climatic condition, soil type, availability of water, and management practices.

Agricultural uses of the range land have been traditionally limited on the reservation. With the completion of the Dolores Water Project, water has been delivered to the Ute Mountain Reservation after decades of only sparse ground water availability. Through its Farm and Ranch Enterprise (FRE), the Tribe currently has 7,640 acres under irrigation. This marketoriented agricultural enterprise is one that maximizes successful commercial ventures in addition to providing year-round employment for Tribal Members. As completed, our state-of-the-art farm features 109 center pivot sprinkler plots, ranging in size from 40 to 140 acres each. The FRE is always at work testing and experimenting with new crops. Currently, a new sweet corn production facility has been developed, it will allow the FRE to add value to this product and market it directly to retailers. Thus, developing a stronger agricultural product with a higher margin will ensure future income.

On August 1-3, 2023, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe conducted its second Native National Partnership Retreat called NUCHU: PLANNING OUR VISION, modeled after the first retreat in 2015 that produced and community development plan and $140M in new grants over 8 years. Over 90 planning partners attended the CEDS strategic planning retreat in August with 21 tribal leaders (CEDS Planning Team),

Rehabilitation, Multi-Family, Single Family, Service Based

Workforce Innovation Center

Kwiyagat Community Academy

HEALTHCARE FACILITY EXPANSION

Primary, Vision, Dental, Behavioral Health

10 consulting partners, 11 facilitators, and 50 funding partners. In the first two days of the retreat UMUT leaders that comprise the CEDS Planning Team refined goals and objectives, and on the third day presented the plans to funding partners to help align projects with funding opportunities. The NUCHU VISION is below:

Housing Factory for Jobs, Housing, Revenue

Solar Energy for Independence, Jobs, and Economic Development

Paving UMU 201 Anneth Road to Farm & Ranch

Housing and Community Development

Richard Fulton Fort Lewis College fulton_r@fortlewis.edu

Matt Balka FSA Advisory Group mbalka@fsa-ag.com

Kate Kowalski Horrocks kate.kowalski@horrocks.com

Colin Daly Souder Miller Associates colin.daly@soudermiller.com

Hillary Fulton Horrocks hillary@hopeful.consulting

Heather McDaniel Horrocks heather.mcdaniel@horrocks.com

Tim Reinen Reinen Consulting, LLC tim@reinenconsulting.com

Carlos Romo

Souder Miller Associates carlos.romo@soudermiller.com

ADMINISTRATION FOR CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

Varonica Wagner varonica.wagner@acf.hhs.gov

AMERICORPS MOUNTAIN REGION

Amy Busch ABusch@cns.gov.

Jill Sears JSears@cns.gov

BIA DIVISION OF ENERGY AND MINERAL DEVELOPMENT

Albert Bond albert.bond@bia.gov

Kevin Carey Kevin.Carey@bia.gov

Duane Matt duane.matt@bia.gov

BIA DIVISION OF WATER AND POWER, SAFETY OF DAMS BRANCH

Chad Krofta chad.krofta@bia.gov

COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND SOUTHWEST WORKFORCE CENTERS

Ray Lucero ray.lucero@state.co.us

COLORADO ENERGY OFFICE

Christine Berg christine.berg@state.co.us

Ida Mae Isaac Idamae.isaac@state.co.us

COLORADO HEALTH FOUNDATION

Emilie Ellis EEllis@coloradohealth.org

Issamar Pichardo issamar.pichardo@state.co.us

Khanh Nguyen knguyen@ColoradoHealth.org

COLORADO HOUSING AND FINANCE AUTHORITY

Jerilynn Francis jfrancis@chfainfo.com

Chris Lopez cslopez@chfainfo.com

COLORADO RURAL WORKFORCE CONSORTIUM

Suzie Miller suzie.miller@state.co.us

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ADMINISTRATION

Caleb Seeling cseeling@eda.gov

Trent Thompson tthompson@eda.gov

HEALTH RESOURCES AND SERVICES ADMINISTRATION

Cherri Pruitt Cpruitt@hrsa.gov

HUD

Cheryl Cozad Cheryl.R.Cozad@hud.gov

INDIAN HEALTH SERVICES

Naomi Azulai Naomi.Azulai@ihs.gov

KEYSTONE POLICY CENTER

Ernest House, Jr. ehouse@keystone.org

Lori L. Roget Lori.L.Roget@hud.gov

NATIONAL HIGHWAY TRAFFIC SAFETY ADMINISTRATION REGION 8

Gina Espinosa-Salcedo gina.espinosa-salcedo@dot.gov

ROCKY MOUNTAIN HEALTH FOUNDATION

Julie Hinkson julie@rmhealth.org

SOCIAL SECURITY ADMINISTRATION

Shayla Hagburg Shayla.Hagburg@ssa.gov

STATE OF COLORADO BROADBAND OFFICE

Ivy Heuton Ivy.Heuton@ssa.gov

Kristen Perry kristen.perry@state.co.us

STATE OF COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL AFFAIRS

Jacquelyn Stanton jacquelyn.stanton@state.co.us

STATE OF COLORADO DIVISION OF HOUSING

Shirley Diaz shirley.diaz@state.co.us

STATE OF COLORADO OFFICE OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE

Jeff Kraft jeff.kraft@state.co.us

Greg Thomason greg.thomason@state.co.us

SUBSTANCE ABUSE MENTAL HEALTH SERVICE ADMINISTRATION

Traci Pole Traci.Pole@samhsa.hhs.gov

US CENSUS

Kimberly Davis Kimberly.Ann.Davis@census.gov

Dr. Charles Smith Charles.Smith@samhsa.hhs.gov

US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE —FARM SERVICE AGENCY

Brandon Terrazas Brandon.Terrazas@usda.gov

US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE — RURAL DEVELOPMENT

Irene Etsitty irene.etsitty@usda.gov

Robert McElroy robert.mcelroy@usda.gov

Amy Mund amy.mund@usda.gov

Debby Rehn Debby.Rehn@usda.gov

Allison Ruiz allison.ruiz@usda.gov

US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Lily Griego lily.griego@hhs.gov

US DEPARTMENT OF LABOR — EEOC

Patricia McMahon patricia.mcmahon@eeoc.gov

US FOREST SERVICE

Sherry Fountain sherry.fountain@usda.gov

US SENATE

Max Hayes

Senator Bennet’s Office max_haynes@bennet.senate.gov

Amy Horrell amy.horrell@hhs.gov

Kristin Schmitt kristin.schmitt@usda.gov

Helen Katich

Senator Hickenlooper’s Office Helen_Katich@hickenlooper. senate.gov

Dr. Melita

“Chepa” Rank Center for Rural Outreach & Public Services cheparank@gmail.com

Jessica Thurman Montezuma County Economic Development jthurman@co.montezuma.co.us

Laura Marchino Lewis

Region 9 Economic Development District laura@region9edd.org

Caleb Seeling Economic Development Administration cseeling@eda.gov

Marc Santicola Santicola & Company mhsanticola@outlook.com

Trent Thompson Economic Development Administration tthompson@eda.gov

Naomi Azulai Indian Health Service Naomi.Azulai@ihs.gov

The Ute Mountain Ute Tribe is one of the largest employers in Montezuma County. As such, our commitment is to support economic development throughout Southwest Colorado, UMUT maintains contact with and collaborates with a range of local stakeholders, including:

Montezuma County

Southwest Colorado Small Business Development Center

Region 9 Economic Development District of Southwest Colorado

La Plata County Economic Development Alliance

In addition, UMUT collaborates with dozens of local, regional, statewide and national nonprofits and governmental agencies as shown above.

BEFORE

INCREASE THE AVAILABILITY AND QUALITY OF HOUSING STOCK ON THE UMUT RESERVATION

1.1

By the end of Year 1, complete Comprehensive Master Plan and Housing Plan for Towaoc and White Mesa.

1.2

By the end of Year 1, rehabilitate a minimum of 7 unsafe and unhealthy homes.

Horrocks

HDR

Native Strategies

Reinen Consulting Planning Department

Region 9 CROPS

Tiwahe Initiative

WCA Planning Department Housing Department

30, 2024

1.3

By the end of Year 1, construct at least 5 multi-family homes (duplexes) for 10 families.

1.4

By the end of Year 2, rehabilitate a minimum of 7 unsafe and unhealthy homes.

1.5

By the end of Year 2, construct at least 5 single family homes for 10-30 members based on 2-6 people per household.

1.6

By the end of Year 2, construct 1 Sober Living multi-unit facility to serve 5-10 clients returning from substance rehabilitation.

Housing Department

Reinen Consulting Horrocks

WCA September 30, 2024

Tiwahe Initiative WCA

Housing Department

Reinen Consulting Horrocks WCA September 30, 2025 $2,000,000 HUD (CDS) $500,000

Mógúán Behavioral Health

Housing Department

Reinen Consulting Horrocks

WCA September 30, 2025 $2,000,000 HUD (CHS)

2.1

By the end of Year 1, begin groundbreaking for Nuchu Cultural Center and Market/ Workforce Innovation Center.

2.2

By the end of Year 1, complete the business plan and begin construction Phase 1.

2.3

By the end of Year 1, hire Value Chain Coordinator.

Horrocks

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2024

Horrocks

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2024 $5,099,214 From Above

Horrocks

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2024 $5,099,214 From Above

Horrocks

2.4

By the end of Year 2 hire 20-30 operational staff.

2.5

By the end of Year 2, install shelving and stock inventory.

2.6

By the end of Year 2 begin selling fresh foods on the UMUT reservation.

2.7

By the end of Year 2 open Workforce Development Center and Cultural Center

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2025 $7,000,000 For Phase 1 Completion

Horrocks

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2025 $7,000,000 For Phase 1 Completion

Horrocks

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2025 $7,000,000 For Phase 1 Completion

Horrocks

Reinen Consulting Native Strategies Planning Department September 30, 2025 $7,000,000 For Phase 1 Completion

INCREASE ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT FOR K-16 STUDENTS OF THE UMUT

3.1

By the end of Year 1, identify site location and complete architectural design for Kwiyagat Community Academy. (KCA)

3.2

KCA Staff

By the end of Year 1, complete the fund development plan and business plan. KCA Staff

3.3

By the end of Year 2, begin groundbreaking KCA.

3.4

By the end of Year 2, begin construction of KCA school for 100 students.

3.5

KCA Staff

By the end of Year 2, increase student attendance and decrease suspension rates for K-12 students by 10%. KCA

3.6

By the end of Year 2, increase distance learning opportunities for K-16 students in Towaoc and White Mesa by increasing broadband access.

3.7

By the end of Year 2, identify location and complete architectural design for UMUT educational campus for cradle to grave learning.

KCA Staff

Tiwahe Initiative Broadband Team September 30, 2025

Tribal Council Planning Department Tiwahe Initiative

4.1

In six months determine services, partners, and potential renters/ service providers to provide primary, vision, dental and behavioral health services.

4.2 By the end of Year 1, confirm site location.

Tribal Council

AAIHB Planning Department

Indian Health Services

Mógúán Behavioral Health

Tribal

By the end of Year 1, complete the design and engineering. Tribal Council

4.4 By the end of Year 2, begin construction.

4.5 By the end of Year 2, pursue 638 designation.

Health

Behavioral Health Contractors

By the end of Year 2, secure sustainability through grant writing, third party billing, and other revenue streams. Tribal Council

4.7 By the end of Year 3, open dialysis clinic

the end of Year 3, relocate Mógúán Behavioral Health for Expansion

Health

Mógúán Behavioral Health

Consultants Financial Experts by CHF

HIGH

Tribal Council