Green Blotter 2023

Green Blotter is produced by the Green Blotter Literary Society of Lebanon Valley College, Annville, Pennsylvania. Submissions are accepted year round. Green Blotter is published yearly in a print magazine and is archived on the following website. For more information and submission guidelines, please visit:

www.lvc.edu/greenblotter

i

GREEN BLOTTER

EDITORS

Managing

Gillian Wenhold ’24

Art

Angelica Fraine ’23

Poetry

Alexandra Gonzalez ’23

Prose

Isaac Fox ’24

Assistant Prose

D.D. Deischer-Eddy ’23

Design

Annie Steinfelt ’24

READER BOARD

Katherine Buerke ’26

Carley Herndon ’25

Lindsay Keiser ’24

Brielle Krepps ’26

Katelyn Price ’25

FACULTY ADVISORS

MC Hyland

Holly M. Wendt

ii

Shelby Moyer

Coyla Bartholomew

Maya Salem

Caitlyn Kline

n.l. rivera

Nate DeChambeau

Caitlyn Kline

Julia Irons

Caitlyn Kline

Dylan Rossi

Jaeyeon Kim

Em J. Sausser

Kalani Leblanc

Kira M. Dewey

Julia Wawrzynski

Savannah Parker

D.D. Deischer-Eddy

S. G. Smith

Sophia

D.D.

J.

Abbie Hoffer

Ashley Pearson

Bryan Alvarez

Isaac Fox

Madeline Timerman

Caitlyn Kline

Halle Kibben

Angie Alberto

Jaeyeon Kim

CONTENTS

The Duckling and the Peacock

Sweat and Success

FIRE MAN

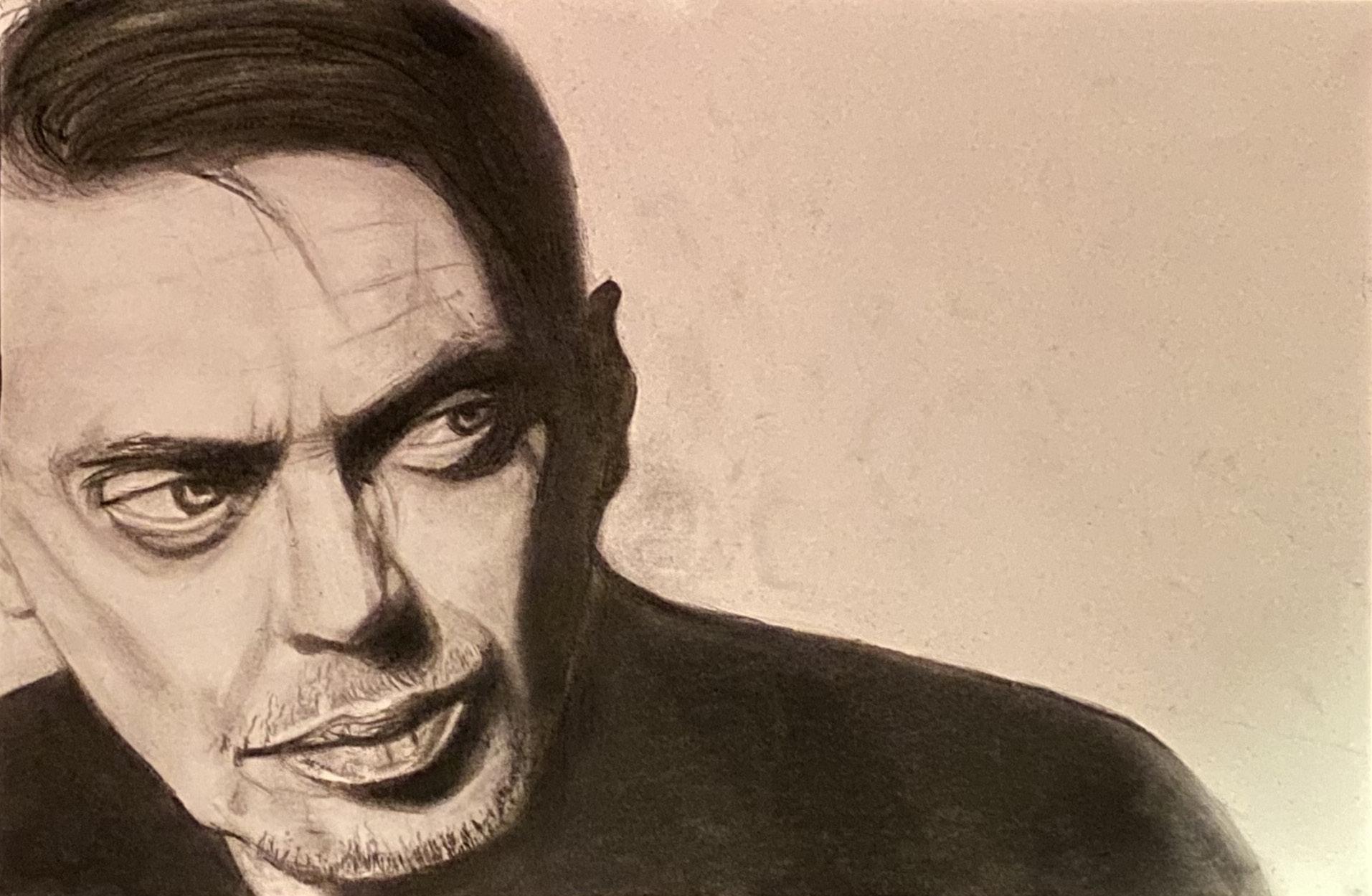

Charcoal Study (Steve Buscemi)

thoughts on turning twenty

Pressure

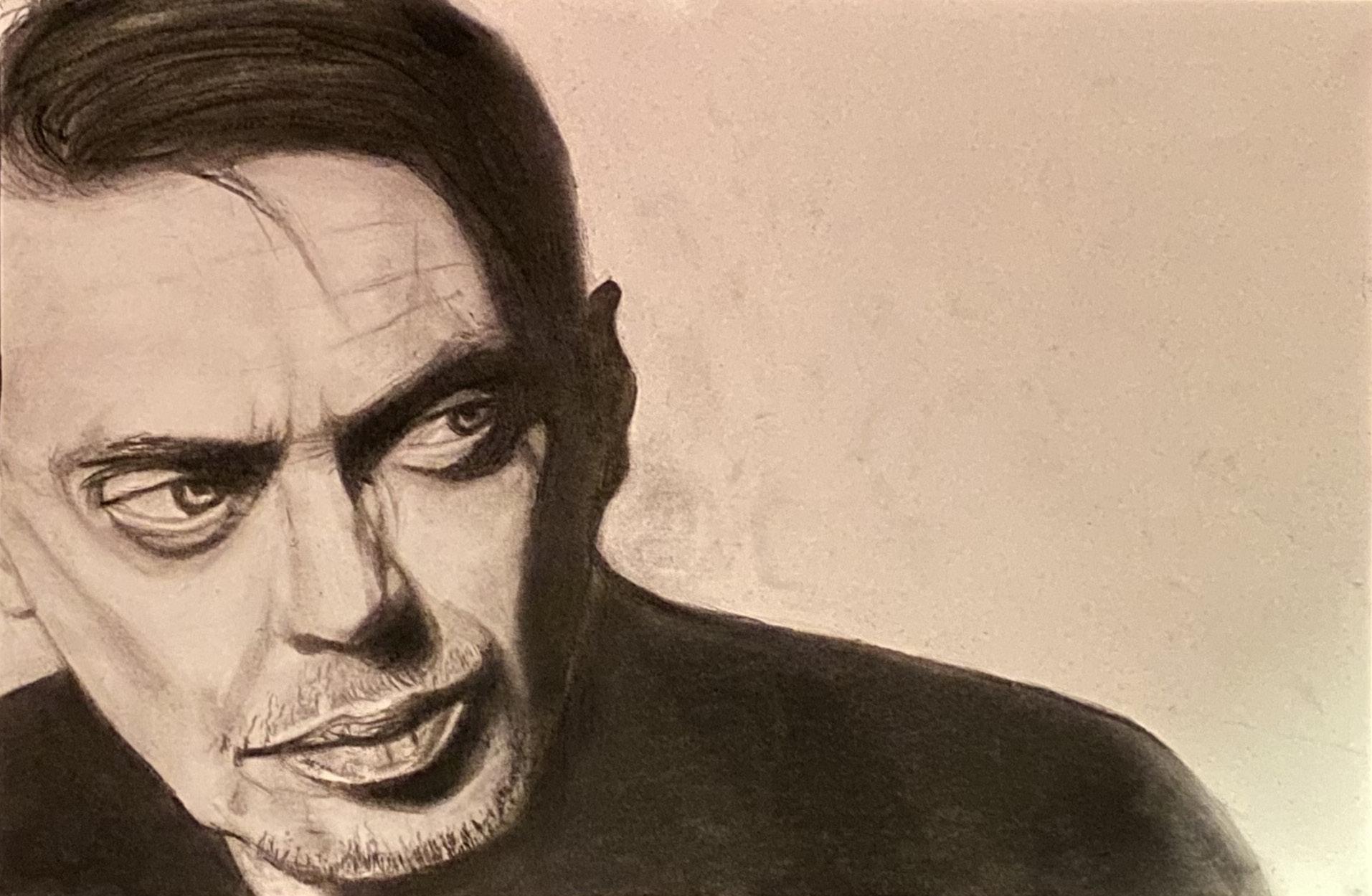

Charcoal Bust Study

Less

The Boy From A Land Where Sun Never Set To

iii

Bunting

Dalto

Paige

Deischer-Eddy

Keji Akintunde

Nassan

A. Kamara

Bunting

Olayioye

Naheda

Alyssa

Sophia

Polhill

Joseph

to Offer Liquid Acrylic Study (Marina Diamandis)

album

moondance Small Faces Assortment of [Villainous] Traits Cowboy Years Assaulting Gaze Untitled A Conversation with Icarus Who’s There? Terrestrial Macaque Goddess of the Moon womanhood Morte

how to love an

/ in the car my dad plays

my father who will never reconcile with the country that raised him

Reflection from a Communal Dorm Bathroom

Study

It Takes In Which

Grandfather

Drinks Together Navas Dry Leaf on a Creekbank The Lovebirds Peace Garden Watercolor Inlet Daybreak Slipped Away Scent of Love Cover 1 2 6 7 8 15 16 18 19 22 23 25 26 27 28 29 31 35 36 38 39 40 41 46 47 48 50 52 53 54 56 57 59 61

Self

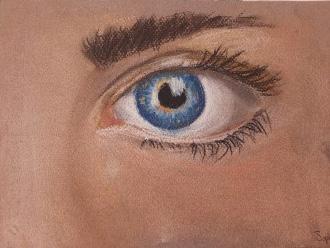

Human Eye

Left

My

and John Wayne Gacy Have

1

and Success

Bartholomew

Sweat

Coyla

FIRE MAN

Maya Salem

ember: noun. 1. a small piece of burning or glowing coal or wood in a dying fire (Oxford Languages);

2. a man

1. fire fighter

“Ember!” cries the captain as orange licks the space. Dark outlines kick, flip, punch as they avenge the beast.

A well-rehearsed orchestra they play, uniformly ablaze a matinee masquerading, while wretched lies burn the stage.

With their heads screwed on tall and their shoulders puffed out wide, Fighters descend on their work: a crumpled wooden pyre.

The helpless crowd around, bundled up in proofed blankets, cheering, crying, cursing how the alight beast covets.

They celebrate the extinguished flames, but from fright, never utter its name.

But somewhere in the back, Ember pulls off his hardened helmet, a single streak of orange hiding among braided chestnut.

A spark seems to burst from his woven hairs, soon as it lights, it aptly disappears.

For within his translucent skin, a fire has always turned. But, like the Fighters on his team, the glow begets concern.

Beneath the fibrous muscle and the curved rows of bones, his soul is black and charred by the teachings of his foes.

In a society where half-truths are doled so casually how is history written when framed by endless tragedy?

2

Fearful of what they don’t understand the Leaders treat Fighters as if they were damned.

This is a tale of a man who believed the myths he was told. This is a man who was burning beneath his armored soul.

He’d put out flames, save the one he grew, until the world he saw became the one he knew.

2. spark plug

“Fire!” stares seem to shout, judgment shaped like a spear. Ember’s head hangs, strings slackened by his puppeteer.

Driving back to the station, he watches signs pass by: “Wood is Not the Enemy!” “Good Citizens Comply!”

At the end of the week, he packs and waves goodbye to the station, past slatted houses, gridded streets–utopian ideation.

Once beyond the short meadow, he begins to slow his pace, this part of town looks like an entirely different place:

no wood to be seen, very few trees an endless lake, floating mirages, and breeze.

A fading entrance: “Home of our Brave Fighters” is chiseled in flint. In water stretched before him, kaleidoscopic reflections glint.

Ember makes his way down a jetty lined with boats, before unhitching one and setting out afloat

past buoyant containers made of retired industrial steel, Ember paddles to dock home, a heavy sigh capping the ordeal.

Next to the entrance, he fetches a ring with a singular key where a miniature extinguisher hangs–alien to the sea.

3

Colors dim on the horizon; the light in the boat clicks on. Within the darkened waters echoes a foreboding swan song.

3. a flame

It’s darker now, isolated lights dot the water. They’re like twinkling stars–if they lost their armor.

Atop an iron chamber, Ember’s eyes reflect the sky: a floundering abyss, a burrowed black and white magpie.

A match strikes paper. Ember’s brows furrow, chest starts to glow gentle ripples turn to waves, creaking and bowing below.

Orange sweeps across the hills with raging ferocity, thick gray billowing above, beckoning the fire team.

A fuzz envelops the sun, blinking into sepia, water bleeds into the sky, a bath of blue ambrosia.

Quilted clouds clot over sage spires and treetops, together awaiting fate as flammable crops.

Ember’s team streak past him, rooted where he stands, open jacket billowing out in the wind, helmet in his hands.

The orange wall surges through him, as it has always done, but this time, he’s not protected–there’s no chance to outrun.

And so it comes: the roaring rushing rousing ravaging wrath that has no call but to burn through everything in its path.

White floods his vision before being clouded with ash, remnants of a non-grayscale world rest on his eyelash.

Ember falls to his knees as wind escapes the forest, thunder rolls beneath him, skies pouring out in earnest.

4

Moments ago, a fire lit deep in his bones. Now he lays empty, dull, nothing aglow

Raindrops drizzle, splash, then sizzle. He closes his eyes the world muffles.

They don’t see the insects infesting the wood, nor do they see that prescribed burns are good.

Instead, they play a game before it all goes kaput, driven by the fear of their lives caked with soot.

For the carbon-combusting triangular traction, we’ve all been taught the way to kill the reaction.

But what do you do when you’re confronted

With the truth?

With killing the best part of you? With killing your core-most value?

When you are chosen to fight only because of your differences, the ash wings you’ve been given are as durable as Icarus’.

but–

beneath blackened ground, new life is fumbling little green sprouts shoot out, the soil rumbling

Ember pushes off the ground and breathes into the storm stretches out his fingers, and atop his hand, a lick of fire is born.

5 4.

fire man

6

Charcoal Study (Steve Buscemi)

Caitlyn Kline

thoughts on turning twenty

n.l. rivera

i have lived my life like it had a deadline, trying to do everything at once, everything in time.

each day has felt like an undeserved extension–it must be why i rush the way i do

i know that, just around the corner, is the apology, the rug pulled out “i’m sorry, i’ve given you all the time i can” from under my unsteady feet.

yet here i stand, on the cusp of a new decade and i realize i was rushing for nothing.

all i have earned is a whirlwind past, and a life lived more like a 2am cram session than a life at all.

7

Nate DeChambeau

Content Warning: Nonconsensual sexual encounter.

A boy and a girl meet in a World History class, junior year. He likes the band sticker on her laptop.

They exchange numbers after the teacher accuses him of plagiarizing her essay. Anxious texts between classes assure each other it’s some mistake. He isn’t sure what to do and considers taking the zero. She meets the teacher after school to sort it out. It was a machine error. They make jokes about it later.

Their texting increases as the year goes on. She alters her path to the lunchroom to walk a little longer with him after class. He listens to her favorite band after she talks about it with such lightning in her eyes.

She wants him to ask her to junior prom. He doesn’t. But he does see her, glowing in the cheap blacklights, trying not to laugh at his dancing. They smile at each other, and for a moment his head empties, all thoughts overpowered and forced away by that smile.

After weeks of missed moments and lost nerves, he asks her out. Over text. She jokes that she’ll never forgive him for it but says yes regardless. They go to an ice cream place, then a movie, then a small, vintage record store on a whim. She asks him out on a second date before the night ends.

They kiss right before she leaves for a cruise. It’s his first kiss, but he doesn’t tell her that. He buys her chocolates on their one-month anniversary, at his friends’ encouragement. Having expected nothing, she is honest with him: “I didn’t think that was a thing we did.”

Embarrassed, she wonders if he’s too clingy. Or perhaps it was normal, and she should have gotten him something as well. She grows distant for a few days, conflicted. He worries she might be upset. But afraid of messing things up further, he says nothing.

A new school year starts, and they get busier. Her afternoons are dominated by jazz band, his by lacrosse. He works three days a week, the same retail job he’s had since sophomore year. She gets hired as a cashier but quits before Christmas.

College applications weigh on them both. Essays and SATs loom like wraiths, gatekeepers of

8

Pressure

their futures. But they still find time for each other, during lunch periods and weekends and the rare afternoons when their schedules align.

She goes to her dad’s for Thanksgiving and shakes her head vehemently when her stepmother asks if she’s still dating that one trumpet player. Information is wheedled out of her, despite several attempts to change the subject.

“Well, be careful, honey,” and the endearment is an expletive in her stepmother’s mouth. “Especially with guys that age. I’d hate to see you get hurt.”

When she gets back, she kisses him, hard. Falling onto the couch, they curl and tangle themselves into a position they’ve never been in before.

Afterward, she pours the humiliation at her need into an apology text, and waits for his anger, his righteous outburst after what she did. Her phone rings, and she nearly drops it.

“Hey,” he says. “Look, I appreciate what you said. But like, you don’t need to apologize. What happened was good. You didn’t do anything that I didn’t want you to.”

A snake unravels from around her heart as she sinks back into her chair. She wants to thank him, to apologize again, to explain the poisonous blend of shame and hunger roiling within her.

Pacing his room, he struggles to find the right words. For the first time in his young life, he feels wanted, desirable, and for reasons he doesn’t understand that might be slipping away. “Maybe we can do something like that again?” He rolls his eyes. Even to him, that sounded stupid.

On the other end, she smiles.

Their friends fall into relationships and split out of them. But as autumn wanes into winter, they stay constant, barely an argument to disrupt the status quo.

Eventually, she relents and allows him to drag her to the newest superhero movie. He loves it, child-like glee in the curl of his grin. She sees what she expects.

Both have parents that work from home. But she has a pool table in her basement, a clever excuse to hide away from parental eyes. Any sounds from upstairs yanks them apart like magnets, sending them scrambling for shirts and less entwined positions.

On the drive back from a lacrosse game, he asks his dad how his marriage has worked out so well. “What’s the secret?”

His dad chuckles. “I don’t know if there is a secret; everybody’s just kinda winging it. I know communication’s important. Being open about what you want, listening to your partner, all that. But I think the thing that’s helped your mom and I the most is that we’re willing to make sacrifices for each other.”

His son nods. Sacrifices, he thinks, and that sticks with him.

9

For their six-month anniversary, they go to the record store they visited on their first date. They play a game, each picking out a record to buy for the other. Both of them choose a record from her favorite band.

Sometimes he makes fun of her playlists and the almost obsessive repetition of that one band’s songs. But he likes the consistency, the frequency with which they appear. He finds a certain surety in the change from “hers” to “theirs.”

The band plays at the ice-skating rink when they go for her birthday. He smiles at the coincidence, not knowing she requested it.

The band plays when they slow dance at the winter formal. She looks up at him with lightning in her eyes and imagines spending her life with him.

The band plays the first time they find the abandoned parking garage. There, without the threat of parents upstairs, they can do more than either had done before.

The boy and the girl don’t have sex for a long time. She doesn’t want their first time to be in a car. She has a fantasy of it being something special, something perfect. So, they wait. The parking garage becomes their hold-over sanctuary, a timeless Elysium of everything-buts and whispered soons.

They make a point to go to as many of each other’s events as they can. Her coat is a puffy maroon beacon in the bleachers of his lacrosse games, catching his eye. After her jazz band performances, he waits for her outside the auditorium, always with flowers. Then one day he doesn’t have time to get any before the performance and gives her a box of sushi instead. She loves it. That becomes their thing for a while, giving food instead of flowers.

Their first time isn’t romantic. It’s on a cold Thursday after school when her mother is out for the day. It’s in their guest bedroom. It’s painful and awkward and mildly embarrassing. But they lie entangled afterward and laugh about it, and the lazy afternoon sun alights on a small moment of perfection.

Lying in the warm bed, she watches his breathing slow, the sunlight turning the hairs on his arm into strands of gold, and she asks what he first noticed about her. He takes a moment to respond, not wanting to say how pretty she looked. That felt too shallow. “You seemed really confident, I guess,” he says, and she clings to that answer like a lost toy.

No longer content to catch rides with her friends, she finally gets her driver’s license. A week later, she runs over his mailbox while backing out of his driveway. He finds it hilarious. She finds excuses to avoid his house for a little while.

She gets rejected from her top two colleges on the same day. He calls in sick to go comfort

10

her, and she cries on his shoulder. Her tears run dry before her emotions cease their unbalanced riot, and she pulls him to the couch. He’s surprised at the timing but lets her kiss him for a while, to make her feel better.

His parents invite her to stay for dinner every so often. She sees their easy rhythm when they set the table, the way she refills his water glass unasked, the interest in his tone when he asks about her work.

As they began to clear their places, his father steps out to smoke. His mom sighs. “Every time. He could have at least waited until the dishes were done.”

Later, she asks him why his mother puts up with it. He shrugs. “She was mostly joking. As long as he doesn’t do it inside, Mom’s okay with it.”

She nods and hates that her first assumption had been weakness. The last few months of high school are a blur in their minds. Final projects, college visits, jazz band performances, work, and the darkened parking garage, whenever they can make time. He asks her to prom. Acceptance letters come, and they make college decisions: her first, to a big city school for chemistry, and him to a small liberal arts school an hour away from hers, undecided major.

As a graduation present, her mother gets them tickets to see their favorite band live. They go with two of her friends, singing and dancing until their ears ring. Worn out from the exertion, she asks him to drive on the way home. He’s tired as well, but he agrees.

“You know, y’all are like the gold standard for relationships,” says one of her friends in the car, making him laugh uncomfortably. “Seriously. You guys are what we compare everyone else to.”

“It’s all an act,” he says, pretending to drop her hand in disgust. “We secretly hate each other.”

She giggles and snatches his hand back, pulling it off the steering wheel.

“Hey, question,” her friend asks after a moment. “What do you guys usually talk about? When you go out together, I mean.”

Another joke covers his embarrassment. He can’t remember the last time they had a proper date. Or much of a conversation, really.

The summer passes quickly, as that season often does. Their parents make jokes about them getting sick of each other, for how often they’re together. The route to the abandoned parking garage is engrained in their minds, branded there by the frequency of their visits. After the shared clumsiness of their first time, they get better, until they wonder how they ever managed to wait so long.

11

Sometimes he finds himself thinking back to the previous summer, how different they had been then. They had seen each other less but done more. Both too shy to move too fast, their dates had been creative, always new places, new activities. He misses that sometimes, the variety, the excitement.

He doesn’t talk to her about it. Easier to keep things the same, rather than risk losing what they have. And a measure of guilt complicates things. He proposes the parking garage as a destination just as often as she does. He enjoys their time there, enjoys what they do there. He doesn’t want that to go away.

A week before she leaves for college, his parents take a weekend trip to Cincinnati. The empty house is an open invitation. She tells her mother she’s having a sleepover with her friends, and they spend the night together for the first time.

They lie together, legs interlaced, when they both decide they are too tired to continue the evening’s activities. As they lull into silence, a thought slips unbidden through her mind. She remembers asking her mother why Dad didn’t live with them anymore. “I asked him to leave,” her mother had said. “We didn’t make each other happy.”

She tightens around him in the darkness. “You make me happy,” she whispers.

He works a seven-hour shift the next day, returning to the empty house drained and spent. His parents aren’t due home for several hours yet, and she already texted him, asking if she can come over.

He sighs before answering her knock.

She kisses him in the doorway, unable to wait until they get fully inside. He can feel her urgency, her desperation in the cling of her hands. His own hang limp by his sides. “I’ve been thinking about this all day,” she whispers in the few, breathless moments when their lips are separated.

Without response, he allows himself to be led up to his bedroom. After a minute, she notices his lack of involvement.

“Do you not want to…”

He shakes his head. “I’m sorry. I’m just tired.”

“Oh,” she says. “Okay.”

He puts on the first episode of a new superhero TV show he’s been excited about. She sits next to him, apathetic towards the explosions and action onscreen. She doesn’t give voice to the storm of disappointment swirling through her head. All the excitement of the day now curdles into frustration. This was a one-time chance: an empty house, a bed, a space other than the cramped

12

backseat of his parent’s car. A perfect opportunity that they were wasting. And in a week, they’ll be off to college anyway, unable to see each other.

She curls closer against him. Even the thought of college spawns a black haze of worry in her mind. She pushes it away, letting her hand strokes his chest. Maybe she can tempt him to change his mind. No harm in that. He probably just needs a little push.

He feels her lips on his neck and lets out a weary breath.

“Sorry,” she says. “Forgot you don’t want to do anything like that.”

He can sense her pulling away. He wishes he could want what she does. But for whatever reason, today the thought of it makes his stomach clench. He doesn’t know how to tell her this, and so says nothing.

Onscreen, one character runs out of the room, overcome with emotion. The protagonist follows, reassuring, and together they come up with a plan to beat the villain.

“Are you sure you don’t want to do anything?”

He looks at her, arms interwoven with his own, head resting on his chest. In her face, he sees flickers of resentment. But he also sees hope, dwindling but persistent. She’ll keep asking, keep pushing. He doesn’t want to, but maybe they should just get it over with. Then they can get back to watching the show.

“Yeah, okay. We can.”

“Really?” She perks up, excitement awash in her eyes. The fire and hunger in her blood force away her annoyance.

He shrugs listlessly. “Sure.”

She smiles, kisses him again, and begins tugging off his shirt.

He doesn’t remember much of their sex that day; just flashes, tiny instants frozen like photos, burning in his mind. Discomfort. Longing for it to be over. Her eyes staring up at him, unseeing, filled with lightning. The passage of time marked only by the short cycle of songs crooning out of her speaker on loop.

He remembers thinking that it was a sacrifice. She wanted this, and he made a sacrifice so she would be happy. That’s what people do. That’s what makes relationships work.

After a long time, she realizes he isn’t enjoying himself. She asks if he wants to stop, and he nods.

They collapse on opposite ends of the couch, naked and distant. A song fades out, and the guitar of her favorite band spits out an opening riff. He snaps the speaker off. It startles her. She wants him to reach out, to crack a joke, any respite from the soft pressure closing around her throat.

13

But he doesn’t. So they lie there, in the devastating, crushing quiet. He gathers his clothes from the family room floor. He doesn’t feel angry, or sad, or hurt. His relief that it’s over is a tiny drop in an empty well.

But something must be wrong, because why else would she look like that? Head hunched, arms clinging tight around herself. And her eyes, in the thin splinter of time she’ll meet his own, so filled with guilt.

He hugs her, and she crumples in his arms. “It’s okay,” he says blankly. And she leaves.

They break up a month into college. Long distance wasn’t working out.

14

Charcoal Bust Study

15

Caitlyn Kline

Less to Offer

Julia Irons

“We rip out so much of ourselves to be cured of things faster, that we go bankrupt by the age of thirty and have less to offer each time we start with someone new.”

- Mr. Perlman, Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me By Your Name [Film]

Last night, when I watched the movie, I realized it was the eighth time I had watched it in four years. Eight times hearing the same monologue that now hangs next to my mirror as some sort of affirmation. Only a certain type of pain can bleed words into reality, in the way that their overconsumption can easily be a rock tied to my ankle.

One of my professors said the syllabus didn’t accommodate for the “quiet kids.” God, why must my inner struggle be made external in the hands of the unenlightened.

I used to think my anxiety would make it hard for me to function in college but now I know I had nothing to worry about. Over and over

told to push myself because I could do it, and almost every time I did. But in retrospect school picked me apart like a vulture would to roadkill, ripping into my flesh because that is the only thing they know how to do. Some might say I’m being dramatic,

I care about people too much and feel things too intensely, and I have friends that I will never speak to again.

“Is it better to speak or to die?” listening from the fire escape to the cryptic murmurs of Richmond’s back-alleys I wonder if they are really that different—

16

sometimes speaking feels like dying, but I also think too much about people I shouldn’t

but then remember that Sylvia Plath said “wear your heart on your skin in this life”

so I relieve the pressure of my limbic system and I write poems about how people make me feel, because they seem to listen more when my pain sounds pretty.

At a small jazz show on the next street over, an older woman turns to her husband and attempts to speak softly over the guttural belts of the saxophone. This isn’t real music, she said, I like the guy last year better.

Yet I had been hypnotized for the last fifteen minutes—the steady beat

of the bass guitar ricocheting around my skull like a syncopated bouncy ball, for music had always been there for me. The other day I picked up an apple from the counter and with my thumb I felt a bruise, so I cut it out and threw it in the trash—

it was then that I wished to cut out the soft spots for people I had grown out of

if it meant I wouldn’t have to feel them again. Although, the thought of losing them as pieces of myself would keep me up at night in a way that wouldn’t have before—

now I have holes in my nose and my dad’s handwriting on my wrist, and to my cat I’m the best person in the world.

How could there ever have been a time that I did not know who I was, thank God I found the words.

17

Liquid Acrylic Study (Marina Diamandis)

Caitlyn Kline

18

how to love an album / in the car my dad plays moondance

Dylan Rossi

This is beach date. I stand on the ocean with you above the drift. But on beach date my head gets heavy, like a weight on a hook. suddenly i am still and sinking. I want to flail around but something possesses me, a straightjacket, so i try to write about it.

I scribble out a few words, passion, jukebox, fish meat. I remember the time my dad took us on the boat and we didn’t catch a thing. I remember the sun but in no particular position, breaking or fading out, in the cloudless sky.

I remember the fish that ate me. over and over. overboard the hook that flayed me. i remember my dad unaffected. untangling my line. showing me how to grip

19

a fish and gut it and scale it and throw it on the grill and eat it back.

I’m slow to learn these things. It’s so hard to stand on the ocean above the fishes and just pretend like you never knew them, watching them swim by. and you know, (now i’m really thinking,) how many times have i sat on docks and stoically gazed at the horizon fishing for the more-to-life?

(there’s a tug.) love has only slipped the cracks, those glimmers are somewhere underwater. (again.) will it find me, when I’m engulfed in the sea? or do I chase it—

I was in the car, thinking about this. My dad was driving. I remember when he told me about rock and roll, i was in the backseat. he was playing all these songs and they all sounded the same. everyone sang about the end, the end of love, the end of the road, the end of putting up with the man. (i laughed,) it was all so self important, it was all i wanted, for these moments to have meaning simply because they were passing. (We pull over at a rest stop) (and we eat together).

20

To love an album you have to love someone. Get caught in transition. Hung up on threads. You have to kill yourself at least once and mourn for years after. You have to remember that time when you grew your hair out Or when you met her. To love a girl you have to love an album. Know unending passion. Gaze into night’s crushing hook And sink your teeth into its fruit. Remember being force-fed Reconciliations with your past selves and understanding How you came to be this way. Tell her this, In some restaurant by the seaside where you’ve decided You belong. Let a song skip or fall asleep for a year and Struggle to find your bearings on the other side. To love Someone you have to lose your bearings. Your By The Seaside Album or Your Past Selves or Love And Its Many Threads, It’s almost arbitrary, what song follows The last, until it ends—

you’re under my arm now. beside you van morrison— i am still. you held it in the doorway and you cast i am thinking of far away against the pointed island breeze / said your time was and there’s so much of it. open, go well on your merry way / Past the brazen you are naked on a beach and footsteps of the silence easy / You breathe my hands are floating. in you breathe out you breathe in you breathe out you adrift, asleep breathe in you breathe out you breathe in you breathe out / And you’re or dreaming. high on your high-flyin’ cloud / Wrapped up in your magic shroud as ecstasy surrounds you / This time it’s found you.

21

Small Faces

Jaeyeon Kim

22

Assortment of [Villainous] Traits

Em J. Sausser

My mother created me in her image, having perfectly crafted each feature on my face and each ability I had. Before I could think, before I could feel, she smiled as she came to know me. I remember her eyes, even the slight smile that pulled at her lips as she spent days working over me. Though I wasn’t yet functional, I began to connect these hours of hard work with the idea of love. Time spent with mother was a treasure, but the time she put into creating me was love. It had to be love.

She parted the deep black hair from my eyes and smiled as she breathed life into my body. I looked at her, locking eyes with hers. Perfect was a word incapable of describing her—her dark hair framed her face in a comforting way, her lilac eyes shined, a slight dimple formed by her smile when I blinked. Her face seemed to tell the story of a long history, one in which I may have lived before. Perhaps, we were happy once a long time ago.

We searched each other’s faces, getting acquainted silently.

I felt everything in that moment: I felt the love of the hours spent together, joy as I could feel the wind embrace me, even humbleness at coming face to face with my mother. Yet, I felt weighed down by the fear that swept over me suddenly. The perfection that my mother represented—the eternal constant she was—had been touched by a cruel world. I reached out to feel a light scar that spread across her shoulder, noting her smile dissipate. Her eyes lost their wonder, and they suddenly seemed weary. I began to weep.

The sight of my tears disgusted her. She stood quickly, putting an endless space between us. My outstretched hand reached to try to fill the gap.

“Mother,” I squeaked with the voice she gave me. “Mother, don’t back away.” She drew her sword—a long silver blade that crackled with blue lightning.

“You are not who I thought you would be,” she spat, “and never call me that.”

My face twisted in pain at the sting of her words. Perhaps I had done something wrong. Her smile only left when I spoke—when I wept. I drew my hand back, searching my mind for the next step. I sniffled and, despite my best efforts to stop them, my tears continued to fall. Mother was upset with me. But a mother who put so much time into me, who crafted every aspect of me, could never despise me… right?

23

“Who did you think I would be? I could be them instead,” I blubbered, wiping stinging tears from my eyes. Her brows furrowed, her teeth poked through her lips as if they were the fangs of a wolf.

“You could never be her,” she scoffed. “And clearly you cannot be strong.”

Her words pierced me more painfully than her sword ever could. My chest ached as she turned and walked off, abandoning me where I was created. I reached out for her, I tried to chase after her, but my new legs were weak. I fell onto the cold ground, watching helplessly as she turned into a silhouette, then vanished on the horizon.

My mind began to wander as I pondered if she smiled at me before I ever drew a breath, or if I’d dreamt it as a comfort.

24

Cowboy Years

Kalani Leblanc

Fast air feels best on hair when you know there will be no morning consequences.

The closest thing we have to canters is driving over speed bumps.

Alcoholics love to introduce themselves, shake your hand as they take your soul. They’ll take that soul And sell it for another Modelo.

Cowboys aren’t easy to love, harder to hold or so I’ve heard. That’s why Mom stresses “Come home early.”

25

Assaulting Gaze

Kira M. Dewey

Oil paintings lit by fluorescents

That illuminate each canvas bouncing off the golden ring glittering on my great-aunt’s finger

Bare skin like polished ivory glows defiantly against chiaroscuro backdrops

shameless unconcerned by probing eyes

My great-aunt studies Psyche shining lamplight on her husband’s hidden face

elderly gaze unwavering at gods exposed

“Let’s go,” my chaperone demands “And cover up next time— I won’t be seen with you in that.”

26

27

Wawrzynski

Untitled Julia

A Conversation with Icarus

Savannah Parker

Tell me something, he says. Okay.

Do they remember me?

Yes. You’re a cautionary story.

Why?

They say you died to disobey.

Tell me something else. Okay.

Why do you want to write about me?

I want to know if my death is an affordable price for autonomy.

28

Who’s There?

D.D. Deischer-Eddy

Knock-knock!

Who’s there?

Loneliness.

Loneliness who?

Don’t you know that if you don’t find someone now, you never will?

I have plenty of time. That’s what they all say before they buy 20 cats and live alone forever. You’re bluffing.

Of course I am. We’re not living in the Middle Ages, you know. Although… with your diet? You might not have much longer. At this rate, no one will want you, dear. Go away, please. What? It’s just a joke.

Knock-knock!

Who’s there?

Stress.

Stress who?

You will NEVER get anything done, finish all those books before you die.

I’m still young. They all say that! And then they get sick, or they get murdered, and you don’t want that, do you?

Don’t you want to say you finished something? Please leave. I’m trying to work.

I warned you!

Knock-knock!

Do I want to know?

It’s the abyss. Not you again.

I see you’re lonely and stressed. Looks like you need some company. No, not today. Please, any time but today. Sorry, I don’t make the rules. You do. I never asked for you. No one does, sweetie.

29

Knock-knock! No.

Won’t you ask who’s there?

Won’t you let me in? No. Go away. Why? I want to help.

I’m tired. Let me sleep. Let me not think. Let me pretend at least until tomorrow.

Not even for hope?

Not even for you.

Knock-knock!

(No answer.)

30

Terrestrial Macaque

S. G. Smith

Content Warning: Painful sex, purity culture.

Everyone in the 9th grade told me that first kisses were bad. They said that kissing always sucked at first, but eventually it got better. Just the thing a recently-diagnosed-with-anxiety perfectionist needed to hear. I wanted to be a good kisser. I needed to be a good kisser for my own sense of selfworth. But I had to start somewhere.

“Just get it over with,” said my friend Mackie. We were on a class field trip to Chicago. A bunch of raging horny young teenagers on an overnight trip—a great idea on the administration’s part. The whole trip I had been seatmates with my new boyfriend as of a week ago. We had spent the entirety of the bus portion hungrily clasping each other. I had even let him touch my butt. But the trip was coming to a close, and I knew it was time to do the deed. We sat down next to each other on the bus, waiting to head back to the hotel on the last night.

“We need to kiss,” I said stoically. For once, I wasn’t nestled up against his chest. I sat straight in my seat, staring forward. My eyes fixated on the faux leather of the seat in front of me. I didn’t want this moment to happen. It wasn’t romantic. Teenagers laughed and screeched around us. The bus smelled like body odor and cheap perfume. But I needed this kiss in my past.

He wrapped his arm around me. “Hey hey,” he tried to soothe me. “It’ll be okay. Trust me.” He tilted my head towards his with two of his fingers and tried to look me in the eyes. I avoided them, already starting to cry. He leaned forward and we smashed lips against each other, hard. There was no space between our lips. Just pursed lip pushing against pursed lip. I could tell it wasn’t how movie stars did it, but I didn’t know what to change. We broke away, and I buried my head in his chest, my heart welling with embarrassment.

While most monkeys live in the trees, macaques spend the majority of their time on the ground. I see myself like a macaque. During my first kiss, I should’ve been on cloud nine. Despite it being sloppy, despite my lack of knowledge about kissing, I should have been smitten, so crazy infatuated that none of it mattered. Instead, I spent my time down on the ground, staring into the reality of the situation: I was going to have a first kiss, and it would not be good, so I would not enjoy it.

31

#

Two years later, the same boyfriend gave me oral herpes, more commonly known as cold sores. I knew he had one, so, as any rational being would, I refused to kiss him. I stayed on the ground, not allowing myself to even dream of kissing him. But that boy did not live on the ground with me and the macaques. He had grown up in the trees, unbothered by consequences. Sure, he faced hardships and ramifications, but he wasn’t afraid. He could easily swing past on a vine while I trudged my way through, dreading every moment of it.

One day, forgetting he had a cold sore, he kissed me goodnight (we had become much better kissers at this point thanks to experimentation with tongue and a decent amount of alone time). I immediately pulled myself away from him in shock—not the good kind. I was so mad at him. He knew I didn’t want herpes. Who did? My mom had been able to avoid contracting them in a 20-year-marriage with a man who had them, and I couldn’t last my boyfriend’s first contraction.

A week later, a cold sore crept up the corner of my mouth in the crease between my lips. I felt devastated. I was now permanently infected, I was spoiled, and there was no going back. Technically, I had an STI, the very thought of which made me cringe.

The cold sore was painful, especially because of its positioning. Every time I smiled or ate, it cracked open, blood trickling down the side of my chin. The internet said it would go away in twothree days. It lasted two weeks.

The cold sore brought me closer to the macaques again as most of them also have oral herpes. Macaques are just a bunch of silly primates, walking around on the ground, picking the cold sores on their lips while the other monkeys rush by, and I had joined them in their solemn march.

When mating, the male macaque rushes at the female, humping her from behind. The female usually stands still, maybe leaning into it. She accepts it, but she doesn’t look too enthusiastic. As she ages, she may become more participatory in the act, but not as much as the male.

The first time I had sex, I was in pain. I had wanted it, craved it even, and now here it was: uncomfortable and painful. But maybe this pain was the good feeling women always talked about, and eventually I would reframe this pain into pleasure in my mind.

The next year and a half, sex was painful. Each time I’d think maybe I’d finally enjoy it, because, surely, I thought, that’s how sex worked. I told him it was okay, that this time it would be better. It never was. I lay in his dorm, holding my breath as I clenched my jaw against his shoulder, praying for him to finish quickly. I was often still and not active, hoping that by doing the work himself he

32

#

would maybe enjoy it more and finish faster.

I see myself in the blank stares of the female macaques. I am brought back to the nights staring at the ceiling, wondering what’s wrong with me. I wanted to have sex. I wanted to enjoy it. I wanted to please him. But instead, I gritted my teeth upon entry and mentally blocked out the pain.

Eventually, I went to a doctor and pelvic floor therapist. My sex life improved tenfold. I finally had pleasure in sex, and I could mentally stay in the moment. My boyfriend noticed a difference too, and he was so relieved I enjoyed myself. I was like a middle-aged macaque, finally learning how to work her own body to the rhythm of the male against her.

A little after we started having sex, my boyfriend and I joined the same campus religious organization. We met in small groups where we dove deep into the Bible with other Christians. We loved the community, and we talked to each other about our great experiences. We formed tightknit friendships with others over our shared faith, and we went to a church-like service on Sunday nights with an awesome live band.

But one weekend, on a spiritually intense retreat, I made the mistake of telling a leader that I was having sex. I had wanted their support as I was going through a difficult time, having painful sex over and over in the hopes that it would improve. I bet you can tell what happens next. Surprise surprise, large Christian groups don’t react well to women having premarital sex.

The next semester, the organization took many different strategies to reclaim my purity. Although I had only told one leader, suddenly the entire leadership team knew and wanted to talk to me about it. I was excited to be selected for discipleship, until I found out it was only to make me pure. I wanted Jesus and friends. Instead, all I got was shame.

My boyfriend was wise enough never to tell his leader, but I’m sure they found out through the grapevine. He was never approached. He wasn’t asked to coffee weekly by different leaders to discuss “life and relationships.” Once again, he was swinging in the trees while I was stuck on the ground, looking up at him, desperately wanting to join.

We have the burden of responsibility and shame. The knowledge that, if we make one mistake, it will all fall on our shoulders, not the men’s. All the firsts are supposed to be magical. But they aren’t. Coming into your sexuality is weird, gross, confusing—and yet we are expected to be experts the moment we slip into bed.

33

#

#

When I visit the macaques at the zoo, I watch the females. I sit silently as they carry their babies on their necks, as they endure mating with males, as they try to survive. It’s disheartening to say the least. Facing setback upon setback, only to see the other monkeys breeze past on the vines. Sometimes I catch them looking at the trees and even climbing across them, but they know where they belong. The females wear a grounded gaze, as if they have seen the troubles of the world and made it back. But they stay alive, trudging across the zoo terrain one step at a time.

34

Goddess of the Moon

Sophia Bunting

35

womanhood

Paige Dalto

i wanted a microscope to search for life within the puddles on the street adjoining mine

i wanted rain boots every April season to live in the downpours

to revel in temporary ignorance

i was given summer dresses and heeled sandals that rubbed my ankles raw

i noticed that my sibling four years younger wore ladybug rainboots these gifts did not come from my family

i was told “grow your hair, you look like a man”

i was shown to apply mascara to coat my skin in acids reaching for a perfect porcelain

36

an appearance for a particular gaze

you must put in more effort not to your well-being but your physical self no one will seek a woman who does not care for herself who has her own opinions a trojan horse of expectation

“shut up” he said to me and silence began a lack of voice no it has been taken a theft from multitudes and if we reach past the shame and dust to grasp at that self a repossession is met with ridicule a scoff

there is no congratulation for reclaiming what is ours

37

D.D. Deischer-Eddy

She’d gotten blood on her dress again. It was her own fault for insisting on dressing like a maid whenever she disposed of the corpses. But she was cleaning up a mess—and wasn’t that what maids did? Citrus cleaning solution and mops weren’t this maid’s tools, though perhaps they would’ve kept the smell of iron and violence out of her nostrils. Yes, she wouldn’t stop dressing like a maid, no matter how ridiculous she looked.

The bodies were never the same. Gunshot wounds all over a scarred chest; brains spilling out of a hole hidden among a head of auburn hair; bruises around a thick throat and blue, puffy lips; even some that were completely torn to shreds, with limbs scattered among the dusty ground. Those were the corpses that were the most challenging to hide. These bodies would never receive funeral rites or burn to ash on a pyre. Families, if they had them, would never know what had become of their child or spouse or sibling. Yet here she was, hiding the evidence for the organization and cursing them to suffer, even in the afterlife. It was a job, it was a burden, but she’d long gone numb to the “what ifs” that came with each new death.

Countless years had passed since she’d taken on this occupation. Countless years of arriving just after a brutal murder and pretending it didn’t bother her that nobody knew who took care of the deceased. She was an apparition, a specter—she might as well have been Death. So she took on the name Morte and made herself Death. It mattered not to these gangs and mafias and serial killers who she was, only that the evidence of theirs disappeared by the time she was done. So be it. She would give the bodies the care and decency every human deserved.

After each burial, she held a rite of her own, sticking her shovel into the mound of freshly packed dirt and grass seed and lighting a cigarette she wouldn’t smoke. The vapor spiraled and disappeared into the midnight sky, hopefully reaching the souls of those she’d buried long before and tonight. Her nose twitched at the sharp smell of tobacco and the tang of dried blood. Somehow, she knew the smell of blood and smoke would never go away, no matter how many times she washed this dress. This new stain would fade, like all the others, but the memory wouldn’t. She refused to erase the memories of these people the organization forgot as soon as they died.

Perhaps she wasn’t the one who should offer an apology to the deceased, but the very least she could do was stay by the grave until the earth had fully accepted its new offering.

38 Morte

The Boy From A Land Where Sun Never Set

Olayioye Keji Akintunde

where the bleating of goat echoes the barking of disgruntled dogs. birds no longer warble love songs but caw that brimming with immense sorrows. fiery sun hangs before the pale face of heaven. emitting yellowish red flames. ubiquitous eyes of heaven weep. the mother earth overflowing with tears. yet no one notices or we just no longer care. the

tranquil days, where mother wake to the giggling of her child & husband to the

chuckling of his doting wife, have become nothing but fairytales. mother now is so deaf to discern deafening cries of her child

from that of flying bullets. husband busy dashing beyond grasp of death to pause & relish his wife’s curvaceous brown body. hitherto dreaded forbidden forest now asylum for the folks. now where kids practicalize

hide & seek from the khaki boys. fidgety spirits of brethren whose bodies forever

kiss the ground unburied let out doleful wails & chant ẹdágunró

let war be still let war be still let war be still

39

ẹdágunró ẹdágunró

To my father who will never reconcile with the country that raised him

Naheda Nassan

to the lemon slushies around the corner for ten lira and the Superman chips baked into swirls dipped in The Laughing Cow to the cat that chased the mouse for my brother and I and the orange kitten we found behind the mosque and kept

to the shop owner selling notebooks with gems i begged dad for and the uncle who traced my palms while i sat in his lap

to the cousin twisting tissues tickling my nose and to Wageeh and Waseem and Mazen whom i lost before i could hold

peace be with you.

40

Self Reflection from a Communal Dorm Bathroom

Alyssa A. Kamara

I look exactly like my father. In fact, as I use my towel to wipe the fog off of the mirror to inspect my face further, I find that I am a mirror image of him—younger, softer, but undeniably him. I feel my heart drop to my stomach at the realization. I have no reason to be ashamed to look like him—he is all full of laughs and intelligence, pictures of Africa eagerly sent to share experiences I have never had the opportunity to see. Yet I am upset that I am not my mother’s daughter, that I had not inherited enough from her side. I want to find something more of her.

Upon further inspection, I find that my face is indeed my father’s, but my bone structure is undoubtedly my mother’s to my initial delight; I have her high eastern European mountain cheekbones. Yet, to my misfortune, I quickly find that their protrusion is offsetting, almost alien when I smile. I am very alien, as the product of two of them; if my parents had intersected a century earlier they would not see one another as people. They would look into one another’s very human eyes and see nothing but difference—not that the plights of African and Jewish peoples are completely estranged, but such slight differences in traits set people into binary identities— unrecognizable as human to some. Yet, I am still some fiendish amalgamation of their two separate worlds; my traits, haphazardly needle-sewn together like some social experiment.

My mother’s bone structure makes my eyes look sunken into my skull; I must’ve inherited the centuries of starvation and genocide behind both their histories as well because my eyes recede back into purple pulpy purses that juxtapose with my father’s warm skin pulled taut over my mother’s cheeks. This setup makes the whites and deep black-browns of my eyes more prominent; like increasing the clarity on a poorly taken photo, without the ability to undo it after realizing that the effect makes the picture look strange. I note that this is all set over my irritatingly dry skin— without attention, the valley between the peaks of my cheeks and the hollows of my eyes become devastatingly ashy. My mother’s ex-partner used to point this out to me, and when I was younger, he would rub cocoa butter on my face with his rough hands—you don’t want elephant skin, you’ll regret not doing this when you are dry as a desert.

Even now, I attend to my skin in the same way he told me to but my T.J. Eckleburg eyes still shine big and bright over my valley of ashen cheeks. I find it funny how, in none of the rhetoric about the Great Gatsby I was subjected to, no one talked about how Eckleburg is such a Jewish last

41

name; no one discussed with me how profoundly wrong it could be to analogize the eyes of a Jewish doctor as the omnipresent God of a corrupted wasteland, bordered by unimaginable wealth and social power. Maybe it’s because I am not Jewish enough for this talk to be had with me, just like I am not black enough to be spared the subtle secret racist confessions of people I know, or woman enough to look more like my mother. I briefly think it would be funny if I could recreate the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg when I become a doctor myself, except replacing the eyes with perfect pictures of my ovaries to make it more gynecologist-appropriate. I would do it in the same way some women have reclaimed “bitch” or “bimbo,” to twist the stereotype on its head by choosing to subject myself to it. However, the Ovaries of (First initial). (Second initial). (Generic African last name) has less of a ring to it, not to mention I don’t think people would get—or like—the reference, even if I interchanged my ovaries to my eyes to make it more obvious.

Between my eyes is a new protruding bump; I’ve had my girlfriends approach me, deeply upset with the mere thought that their skin could be flawed even temporarily. I wish I could sympathize with their complaints, but my face has been an ever-changing map since puberty; I grow little stepping stone mounds and white-capped mountains to compliment my valleys and deserts. Like the Little Prince, I take pride in taking care of my little planet of a face, raking out newfound volcanos and plucking out invasive baobab baby hairs; each day I go through the motions of my skinscaping routine in this same bathroom mirror. However today this bump is especially distracting and placed precisely where I could be receiving a delicate forehead kiss later in the day; covering it up would be useless as lips could feel the mound, so I decide on popping it. Ideally, I would remove this ordeal with a syringe needle, one I could insert directly into this inconvenience and watch as white turns to pink then red as my skin would deflate from this release-relief. Something quick and sanitary, easily disposable, so I could hide all evidence of ever having this sort of blemish in the first place. Yet, I am forced to get my own blood on my hands and risk a scab because I am choosing to make a molehill into a mountain. So I place my second fingers around and squeeze inward, with my thirds to brace the rest of my hand.

A small eruption, a little white followed by a small stream of red, and the deed is done; all this fuss over the possible promise of a kiss from a man. Should he be so wrapped up in his affections to grace my world, he would not care, but I feel obligated to. To please him, I did exactly what my pediatrician warned me against doing when an adolescent version of me asked what to do with my topographic skin. Now, the rounded tips of my fingers are stained apple red. I know that immediately upon eating the forbidden fruit, Eve felt regret the same way as I do now because I feel like a fool with this absurd amount of blood snaking down the bridge of my nose. If women were

42

actually made from the rib of a man maybe it could justify why I feel compelled to throw myself at him, like my body is trying to return something that is not mine; maybe that is why I am screwing around with my own face on an early Wednesday morning, but now I am forced to rectify having torn my own skin instead of tending to my face’s gardens with the gentle touch I usually use for the slight chance at another’s.

Being a woman (yet, I am clearly not wholly woman) sometimes feels like wearing a flat cheap sticker across a fast-fashion blouse: I donated blood. Of course, the blood from my forehead is going to waste but whenever it actually is donated, the sticker is a nationally recognized free pass to complain about the discomfort—I’m not supposed to donate blood myself, I now know that I lack the iron and the strength. Every time I need to get mine tested though, the doctors complain about my small rolling veins evading them; I need to drink water until I am supersaturated and have my arm held down. Regardless, even though I do everything right, my veins still evade them. It would be so easy to be like my sister, her veins are a delicate forest green that dances up and down her tan arms that invite doctors and their needles. She always goes before me when we go to these sorts of appointments, so quick and easy that I momentarily wish I was her, or at least had her veins. I wish I could avoid the ordeal, not the action but the struggle with it; I tried donating blood once at school. I didn’t even need a doctor’s note. I subjected myself to it, the feeling of myself being sucked out while the rest of the students—in their respective cubicles—eagerly donated and snacked on their free Oreos.

If someone were to pester me about getting my blood drawn now, I know reiterating this lengthy response would be insignificant. It’s like complaining about womanhood itself— I could talk about the blood: the catty cat scratch conversations, the periods and cramps, the raping and plundering, the abortion-politics and genitalia mutilation, the way that I look so unlike my mother, but I don’t have the tenacity to explain myself more than once. My answer to an overzealous red cross volunteer asking me why I don’t want to donate and one of my male friends asking why I complain so much about my relationship with womanhood: I just don’t like it. An answer to which any red cross volunteer would assume me to be lazy, lardful, uncaring—I am supposed to do it, it makes me “good.” However, this is an answer to which any of my male exes who pride themselves in their love of math rock, being an “ally,” and/or neoliberalism, would be a courageous declaration instead of being the avoidant pass I mean it to be. It would raise me on their matron/martyr/ madonna-whore/manic-pixie-dream-girl pedestal, where they can shout up chants of praise: “you’re not like other women and I like that (insofar that you are not like other women in the narrow binary I believe women should be in!)” Maybe one day, when I inevitably let one of them

43

hold my arms down over my head again, he will realize that he is my needle and I will subject myself to him as many times as it seems fit for me to be “good.”

As the blood pools between my eyebrows and dribbles down my face, I follow it with my eyes to the arch of my nose. I recall being offered a nose job by my mother on the way to school one morning. If I really wanted one, I could get one when I was 18—I was promised this (empty promise) entirely unprompted. She might’ve been projecting onto me but if the roles were reversed I would do the same. I wish I had her no-nonsense nose; hers is straight, stern, sharp, serious. It’s a mother’s nose. Mine is shaped almost like a “J,” a gentle upward slope: perfect for a miniature man to roll up a miniature boulder up until it falls down to the base—only for him to repeat the trek up my face again. I had an English teacher in high school who related all of our daily societal expectations to Sisyphus’ torment; I had a friend who told me that if that is the case then the only relief I could have from this analogy was to imagine Sisyphus as in some way happy, or at least content… at bare minimum: satisfied with his righteousness. I said that I could imagine him being so (I couldn’t, as I wasn’t with my own daily toils). I can now imagine, however, how satisfying it would be for some rich cosmetic doctor to take some shining steel medical tool and smash the bridge of my nose until it was a shape I was at bare minimum, satisfied with.

And suddenly I notice how my whole face is like a balloon laying on its side, a taut brown rubber pulled and tied at the end, a small protrusion at my nose. My face, with all of its delicate juxtaposition, is not strong enough to take a cosmetic beating; I can imagine just one surgical needle being able to puncture and pop it. If my head was a balloon, if it was filled with air: the place that I have been all this time was only containing me—this beige cement block boxy bathroom that smelled oddly of wet cardboard and cheap shaving soaps was keeping me from floating away; my eyes locked with my reflection’s connected me to a chain in the floor. However, if I managed to unlock my eyes and managed to get my bobbing brown balloon head outside, maybe I would be able to float up and look down instead of at myself; looking down at perfect mountain slopes and boulders, hospitals and valleys of ashes; looking at alien architecture nestled in jungles and the other planets in this vast nebula, maybe I would learn that there are things much larger than me— that my skin is the earth’s and the traits that I have are from people who have traveled across the world instead of just their eyes and fingers travel their individual faces.

Yet, my head is not a balloon and I am not floating. If my head ever was a balloon, someone must have popped it with a tool so sharp I didn’t even notice because I am still in the bathroom with my eyes shackled to myself. But maybe, I will leave soon. I have my daily toils to attend to and the blood on my forehead and hands have dried; my daily cosmetic routine has been very much done. I

44

often spend far too long in the bathroom, fixated on myself, doing nothing. At some point I will be startled out of my self-fixation by a roommate knocking, needing their time alone in our bathroom. So, I will leave and I will notice that a bit of my hair had escaped me and was clinging to the carpet only after I had the misfortune of allowing the curly tendril to wrap itself between my second and third toes—grossly lodged between what a podiatrist once told me is called the “toe webspace,” so a simple shake of the foot will not rid myself of it. Maybe then, I will bend over to free myself from my own hair and regret not having looked down before to prevent it from ever inconveniencing me in the first place.

Until then, I’ll sit in wait; staring at myself in the reflection in the fogged-up mirror of my communal dorm bathroom.

45

Human Eye Study

Sophia Bunting

46

J. Joseph Polhill

I left things behind at home

I left my eye on home

She stayed

I took my eyes from home

I took eye and I from home

She stayed

I wrote my heart out of home

I wrote my heart away from home

She stayed

I left Eyes left

She stayed

47 Left

Abbie Hoffer

Content Warning: Domestic violence.

Big Louie’s head lay in my lap as I watched The Little Mermaid for the millionth time. We weren’t allowed to go to Family Video and get a new movie until my sister got paid, and that wasn’t until Friday. Every time Amber peeked in from the kitchen to look at me, I crossed my little baby arms and scowled. She wouldn’t let me play in the swamp like I’d asked, and I’d asked so many times she eventually screamed at me that I wasn’t allowed to step one foot out of the house until she said so. It wasn’t like her to get angry with me like that, she’d raised me since I was just a baby and told me every day that I was her very favorite person in the whole wide world. She was only my big sister, but she acted like a mom too. I knew she worked hard to afford our crummy trailer that backed right against the swamp, and I knew every cent of her paycheck that didn’t go toward paying bills was spent taking care of me. Amber clanked around in the kitchen, making my favorite dinner, chicken nuggets and mac and cheese, as an apology meal. It wasn’t her fault that Johnny had threatened to kill us both that day when he’d come into the diner. Her punishment was meant to keep me safe from him, but I wanted the relief of being able to dip my toes into the cool, murky shallows of the swamp more than anything.

Amber never liked the swamp; she said it smelled bad and there were too many mosquitoes and crawly things that lived there. She was especially nervous about me being near the water, which I couldn’t understand since I was a stronger swimmer than her. I wanted to jump in and swim with the frogs and feel the slimy crawly newts skittering over my toes. But Amber was always afraid that she’d lose me in there somehow.

“It takes things,” she’d explained once, “that’s what everybody says. The swamp takes from everyone here, things they love and things they hate. And I love you so much that if it got the chance, it’d swallow you up and I’d never see you again.” I thought Amber was just telling stories like she did sometimes to scare me into things, but she’d refused to let me near the swamp ever since I’d first asked. Her reasoning that day had more to do with Johnny than anything the swamp could do to me, that I knew.

Johnny, Amber’s newly ex-boyfriend, was a scrawny freckled kid with a loud car and a bad

48

It Takes

attitude. He’d come to the diner and threatened Amber until Bo the line cook jumped over the counter and chased him out. Amber tried to sort things out with the police before she came home, but they didn’t care when he split her lip, bruised my neck, or hit us any other time. She couldn’t expect any help from them, so she’d borrowed Big Louie from Bo, who also promised to drive by a few times that night to make sure everything was okay. I liked Bo, he was a big solid man who always saved me the burnt fry bits when I had to go to work with Amber. Big Louie was as sweet as could be, but he was big even for a Mastiff and his bark made the hair on my neck stand straight up. I hoped he’d be tough enough to scare Johnny off.

Amber let me sleep in bed with her that night. Normally she would outright refuse, claiming I kicked in my sleep and kept her up. But that night after quadruple-checking the door and window locks she read me a bedtime story and bundled us both in her floral comforter. It was the three of us heaped in her bed, Amber holding me to her chest and Big Louie curled up at our feet. His loud breath and the sounds of crickets and frogs eventually lulled me to sleep.

I woke up in the dark to Big Louie barking and scratching at the door. Amber jolted awake and told me to stay put until she came back for me. I started to cry, and she cupped my face in her hands and promised me a strawberry popsicle for breakfast if I did what she said. She opened the door and Big Louie charged toward the kitchen, and Amber followed soon after. I listened in the dark for what seemed like hours, jolting at every little noise. I couldn’t have fallen back asleep if I’d tried. A few thuds and strangled moans traveled through the thin walls of our trailer. Big Louie quit barking, and the silence that followed was more horrible than any of the noise. The screen door squeaked, and a few minutes later I heard the shower turn on. Finally, my sister returned to bed, shaking slightly and smelling like her cherry blossom shower gel. I pretended to be asleep since I knew she’d be more upset if she knew I’d stayed up listening. Big Louie never came back to bed.

The police came to the trailer park looking for Johnny first thing that morning, but no one had seen him. His car and gun were found in his favorite fishing spot, but there was no sign of him anywhere near the bank of the stream. Amber talked to the officer, explaining that Bo and Big Louie had stayed the night on the couch for protection and hadn’t seen or heard anything. The officer seemed skeptical at first, but he peeked under the fluffy collar of Amber’s bathrobe and was suddenly much more interested in whether she was free Friday night than if she’d seen Johnny. I knew Bo hadn’t been there when I went to bed, and from my seat at my pink plastic breakfast table, I could see flecks of blood on the underside of the kitchen counter. But I kept quiet, because I knew Amber and Bo hadn’t done anything wrong. The swamp had taken Johnny, the worst thing in Amber’s life. The two of them had just helped it along.

49

In Which My Grandfather and John Wayne Gacy Have Drinks Together

Ashley Pearson

I do think my grandfather wasn’t the type of man to light another man’s cigarette. There’s something phallic about holding a lighter to another man’s pursed lips. But, these cigarettes were but a prop in a film noir: with sins and banter and sweat being extinguished as quickly as a faulty lighter.

In this scene, John Wayne Gacy smokes an erected cigarette, fire plucked from my grandfather’s calloused hands: burning.

It’s a sticky summer night on the South Side. I stand adjacent to the wrong side of the tracks in a bar on First Avenue.

Sometime around July of ‘72, Grandpa is clothed in the overalls he’ll die in, the ones he’s buried in, the ones I saw him in: too tall, too drunk, too old for Gacy’s taste. The light illuminates

50

a hulk of a man hunched over a cracked, stained counter fondling his last cigarette with yellowed fingernails.

Gacy asks for a light; says he’s from out of town on business.

Grandfather takes another swig of the sweaty glass bottle in his hand: stagnant.

There’s an attempt by Gacy to try to engage him in conversation about politics and Chicagoland and God, but grandfather scoffs and downs another fifty: Too far gone now. Too far gone now.

51

Navas

Bryan Alvarez

In my youth, family seemed perfect. Full of laughs, joy, and the illusion Of lifelong friendship. I wish I could say I missed it.

This last name belongs to a family that Fills me with more pity than anger. Generational cycles of the same vices And temptations. Generational cycles of anger.

My first beer was at 8, at a party they hosted. The patriarch was a drunk mess that night, While the sons watched in admiration for their hero. Even that young, I felt pity and disgust.

The matriarch is my aunt. She is divorced. She dates men half her age. No judgement.

I think I felt the most pity for the youngest daughter, She had the most hope. Even she caved in.

It’s been years since we’ve all been in the same room. I can’t help but think about the small children that will Grow up in that home. Some days I want to try my best To adopt them, so they grow up with actual toys And not empty bottles to play with.

52

Dry Leaf on a Creekbank

53

Isaac Fox

The Lovebirds

Madeline Timerman

“Do you want to see my toe fungus?” Annette bends to untie her shoelaces. Luckily, she can no longer touch her toes.

“That’s alright, Annette.” I place my fingers over hers, folding her hands back into her lap. “I’m sure it’s spectacular but I’m just doing fingernails today.”

“Make sure the color pops.” She leans back in her wheelchair. “I want to look better than Evie.” Annette darts a superior glance at the woman to her left, who is scowling at the floor tiles.

“Rouge, vert, ou bleu?” I channel my seventh-grade French teacher as I turn to Evie. The Quebecois eighty-year-old does not speak English and seldom interacts with the other residents.

“She wants blue!” Annette pipes up. Evie glowers.

“I’ll give you some time to think.” I smile at Evie, although I doubt that she understands me. Max passes me a pair of latex gloves. We are supposed to be volunteering together, but he is clearly uninterested in massaging Aveeno into Annette’s wrinkled skin. Boys can be so squeamish sometimes. I am finishing the last coat of neon green on Annette’s pinky when they walk in: Arm in arm, the woman leans on her husband for support as he leans on his cane. They stroll—shuffle— through the door and around the perimeter of the room.

“Aw,” Max sighs. I nod.

“That is so cute.” The man is sporting pressed blue trousers as though he has dressed specially for this date. His wife wears a cream cardigan, the same as yesterday but special in her husband’s eyes. I imagine that instead of weaving around their geriatric neighbors, the couple is winding their way through a shaded park. The park has maple trees and a crystal blue pond where ducklings wait to devour the bread crumbs tossed their way. The couple stops in the far corner of the room. The husbands leans down and kisses his wife affectionately.

“Tom! You stop that right now!” The nurse in Winnie the Pooh scrubs stomps into the room, looping her arm through the wife’s and steering her to a nearby chair. “We’ve talked about this. Jane is not your wife!” The man, abashed, retreats through the door and back to his room. “There you go, dear.” The nurse tucks a blanket around Jane’s lap. I feel my eyes widen and search Jane’s face for a sign of emotion: Relief, disappointment, shock—anything. But her eyes are clouded over and I see she has already forgotten. The nurse turns to us, her hands on her hips. “Tom is married, and so

54

is Jane. Just not to each other.” She rolls her eyes at the fluorescent ceiling lights. “He’s convinced that Jane is his wife, though, and she certainly doesn’t know the difference.” The nurse shakes her head, the messy brown bun on top bobbing back and forth. “Nice nails, Annette,” she calls over her shoulder as she exits the room.

Max and I lock eyes. His mouth twitches up at the corner, and so does mine. Only in a nursing home, his eyebrows seem to say. In the back of my mind, though, I am unsettled. I don’t realize as I laugh quietly with Max that this fluorescent-washed afternoon will haunt me eight years later. I wonder if Tom and Jane are together right now, wandering the beige-painted halls arm in arm. I wonder if they’re dead. I wonder if anyone else remembers them, or if it’s just me. God, I hope someone remembers me, I think as I watch Jane in her chair. She smiles quietly at the ceiling. For the first time, I am afraid of growing old.

55

56

Peace Garden Watercolor

Caitlyn Kline

Inlet Daybreak

Halle Kibben

The inlet is quiet. The sun, barely risen, sends soft light glimmering at a steep angle over the surface of the crystalline water. Cattle egrets and night herons wade silently among the tall prop roots of mangroves at the edge of the water, and an osprey wings its way to a perch in a towering dead tree. The peace, however, is not complete for us. As Mom and I unload our paddleboard, we slap at no-see-ums not yet sunburnt into hiding. We rush to the water’s edge, I hold the board steady as Mom gets on, and I kick the board coasting out into the empty water, pulling myself up to kneel on the board. Mom takes the paddle and steers us towards the back end of the inlet, where the blue seawater pulled in by high tide meets the warmer, muddier brackish water in a distinct line. Here the beachy sand bottom is replaced by decomposing fallen mangrove leaves and old pieces of the overhanging Australian Pines, needles and branches settled to the inlet floor. I peer over the edge of the board, trying to see past the reflection of the water’s surface. After a few minutes, I spot what I was looking for: a nine-armed sea star, sprawling out over more than a square foot of space. “Hold up, Mom.”

I roll off the edge of the board, careful not to capsize it, and duck under the water, turning upside-down to kick to the bottom for a closer look. From here, the creature looks otherworldly, tiny black and white tiles seeming to armor its back, its underside bristly with sharp yellowy spines. Closer to the bottom, I notice something I didn’t see from the board. Hidden among the muck rests a dark scarlet sea urchin, its spines clutching leaves and twigs and shells in an effort at disguise. I swim to it, scoop it up gently between my fingers, and allow myself to float up to the surface. As my head breaks into the air, I gulp in a breath and my free hand rubs the water from my eyes. I draw my prize up and onto the paddleboard, where it rests, spines waving in slow exploration, as Mom admires it. After a minute or two, I escort the creature back to its home, resupplying it with the disguises it lost during its journey, and rejoin my mom on the paddleboard, where the summer air warms my wet skin. As we paddle out of the brackish water, we catch a glimpse of a baby nurse shark, about a foot long, swimming into hiding among the mangroves.

In the blue seawater, the inlet floor becomes white sand, from which the animals stand out more vividly. Eagle rays glide by, their deep blue, white-spotted wings gracefully undulating as they make their way from a night in the inlet to a day in the open ocean. Lone barracudas travel swiftly

57

through the deeper channels, and parrotfish swim aimlessly in the shadows. We explore the inlet until we see the first visitors drive up. As they begin to unload their SUVs, we haul our board out of the water and leave the inlet to the tourists, like the creatures that already swam away for a day in the sea.

58

Slipped Away

Angie Alberto

Flickering phosphenes of rainbow glass, Burning vanilla and smoking chocolate; Hot like the night we pretended was not. With the oven occupied, A stale house on the counter, And merry voices, mostly dead, In the room of towering green, We abscond into the night

Like star-led men on a mission.

The car, lined with blankets, has its Trunk popped for perfect viewing, Moving theater of glowing homes In a dull community full of ghosts.

We rate their effort, Quiet competition, But there are rules

To receive a grade:

Projectors are lazy and overdone, An ever-growing plague on effort. The more, the funnier; too much is too much; Too little is too bad, but better than nothing:

Aunt Kathy has eight nativities on her lawn: 2/10. That guy with the bionic arm Put out one string light bulb.

59

In the grass by itself.

One bulb, not one strand: 10/10.

Dr. Adelstein has an inflatable Snoopy

Holding a hanukkiah by her door: 10/10. When we return, jolly and judgmental, We put on that movie that nobody likes: The one about kids on an infinity train, Where Hanks plays angels, hobos, and saints.

There’s beauty to me in that Motion capture locomotive, Phantom tickets to unsought lessons; After watching comes the waiting, With closed eyes and open ears:

“We were dreamers

Not so long ago

But one by one

We all had to grow up.”

60

61 Scent of Love Jaeyeon Kim

CONTRIBUTORS