Awe in the Urban Fabric

Can we induce pro-environmental values through urban design? Léonie Bouget Le Bailly . 19028604 BA(Hons) Architecture and Planning University of the West of England February 2022 Word Count: 5485 Figure 1. Awe in Monochrome

Thank you to the people talked with me about my work and helped me grow my ideas. Thank you mum, Amz and Fidel for the encouragement and the support.

Abstract

Copyright

This study was completed as part of the BA(Hons) Architecture and Planning at the University of the West of England. The work is my own. Where the work of others is used or drawn on, it is attributed to the relevant source.

This dissertation is protected by copyright. Do not copy any part of it for any purpose other than personal academic study without the permission of the author.

This discursive dissertation is a theoretical inquiry into the experience of awe in the built environment and the potential of awe-inspiring design to evoke proenvironmental values. Conclusions are reached via logical argumentation after assessing three interlinking areas of research: primarily, the experience of awe and its effects on cognition; the importance of and approaches to value systems and worldviews, focussing on pro-environmentalism; and finally, implementation of these ideas through the lens of urban design, integrating strategies that may induce or create opportunities for awe.

Based on Value-Belief-Norm theory and the conviction that a deeply personal paradigm shift is needed as the prerequisite to effective and meaningful political and practical climate action, I propose that the experience of awe, integrated into urban design, has the ability to catalyse this cognitive shift and accommodate for inner change. My intention is to ascertain whether the experience of awe, when designed into our cities can encourage pro-environmental values and a society more responsive to the demands of sustainability.

Léonie Bouget

1 2

“TRUE AWE RAISES MORE QUESTIONS THAN IT DOES ANSWERS AND CHALLENGES FAITH MORE THAN CONFIRMS IT... AWE IS WHEN LIFE GRANTS US THE CHANCE TO THINK DIFFERENTLY AND DEEPER ABOUT ITSELF ... BEING IN AWE CAN MAKE A REAL MESS OF OUR LIVES BY DISRUPTING OUR CERTAINTY ABOUT OURSELVES AND THE WORLD, BUT IT ALSO ENLIVENS AND INVIGORATES OUR LIVING AND CAN CHANGE HOW WE DECIDE TO LIVE” (Pearsall, 2007, p. xviii)

“IN ORDER TO PREVENT A GENERALIZED ECOSYSTEMS COLLAPSE BEFORE THE MID-TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY, HUMANKIND MUST EXPERIENCE A CHANGE IN CONSCIOUSNESS COMPARABLE IN ITS INTENSITY AND COMPREHENSIVENESS TO THE CULTURAL SHIFTS ACCOMPANYING THE AGRICULTURAL AND INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION.” (Brinkerhoff and Jacob, 1999, p. 557)

5 9 10 11 17 27 29 Introduction Definitions Method Literature Review Discussion Conclusion References 3 4

“CULTURE SHAPES VALUES, AND THOSE VALUES SHAPE HISTORY.” (LENT, 2019, p.27)

This dissertation investigates an alternative approach to environmentalism; one that recognises our values and worldviews as being determining factors of intent and action in our undertaking of a more conscious and sustainable life (De Witt, 2021). I believe that experiencing awe could lead to profound changes in the cognitive processes, value systems and beliefs held by individuals.

Motivation to write about awe came from personal experience and a gratitude for having grown up in the Black Mountains where I am frequently in awe of my surroundings. This upbringing has led me to consider life in a way that honours its natural complexity and my connection to it, but I struggle to maintain this sentiment in cities. I was driven to explore how we can replicate profound experiences such as awe in an urban setting and to question whether this exposure could foster pro-environmental values. Architecture and urban design carries a heavy responsibility in taking appropriate measures to reduce carbon emissions – but in my opinion we have a far greater task than that. We must design a future that is not only technically better, but that allows us as deeply complex individuals and societies, to be better.

Environmentalism is not just about technological solutions and technocratic interventions (O’Brien, 2018). The majority of sustainability discourse, focuses on emissions as the problem, and technology and investment as solutions (UN, 2021). It is accepted by many that the dominant worldview of capitalism is one of the root systemic causes of environmental damage (e.g. Dominick, 1998; Lent, 2017), and yet it is rarely addressed. Addressing emissions is undoubtedly critical but ultimately inadequate without paralleled scrutiny of our organising systems, to identify important drivers and barriers to change (Zhao etal, 2018). We have been deploying purely practical, political, piece-meal solutions for decades to little avail. “The persistent degradation of the biosphere despite growing scientific knowledge suggests that there is a need for sustainability science to take a look at some of the deeper drivers of anthropogenic planetary change” (Ives, Freeth and Fischer, 2019, p.215). We must dig deeper and address the root causes. Inward reflection is crucial and “the deepest driver of … behaviour change” (Ives, Freeth and Fischer, 2019, p.212). Thus far, we have merely been skimming the surface.

Figure 2. Blue Marble(NASA, 2012)Introduction

“ARCHITECTURE IS AN EXPRESSION OF VALUES” (FOSTER, 2014)

Figure 3. Mist in the Mountains 5 6

“I USED TO THINK THAT THE TOP GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS WERE BIODIVERSITY LOSS, ECOSYSTEM COLLAPSE, AND CLIMATE CHANGE. I THOUGHT THAT WITH THIRTY YEARS OF GOOD SCIENCE WE COULD ADDRESS THESE PROBLEMS. I WAS WRONG. THE TOP ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS ARE SELFISHNESS, GREED, AND APATHY, AND TO DEAL WITH THESE WE NEED A SPIRITUAL AND CULTURAL TRANSFORMATION” (Speth cited by Schorsch, 2021)

The design of the cities where 68% of humanity will live by 2050 (UN, 2019) should respond appropriately to the climate crisis. By shaping our environment, we are inviting it to shape us and our path forward. Our cities should manifest the principles that benefit us and our planet in the long-term, rather than perpetuating the damaging principles that dominate today. A growing body of research demonstrates that awe has a profound effect on cognition and subsequent behaviour. It is a process that diminishes our sense of self while increasing our feelings of connection to others and to nature (Yang et al, 2018), and it triggers a cognitive process of accommodation whereby individuals become more open to change (Shiota, Keltner and Mossman, 2007). In short, I believe that by designing for awe, we can encourage the kind of thinking that should lead to more pro-environmental values in our society.

With climate issues perpetuating, there is growing support from sustainability and social science researchers for an alternative approach to finding solutions that focus on the root causes of our problems. Taking a deeply personal look at our values and worldviews, I suggest that shifting these habitual and unconscious systems of thought can and should be critically considered in order to alter our trajectory. As the science of awe evolves further, research highlights its potential to improve emotional, spiritual and societal wellbeing, not to mention the value of its mediating roles that have been suggested to influence pro-environmental behaviour regarding materialism (e.g. Wu, 2022), connection to nature (e.g. Yang et al, 2018) and pro-social values (e.g. Piff et al, 2015).

There is a wealth of research discussing the components of my dissertation individually, but very little that connects them. To me, the term ‘sustainable architecture’ conjures images of green walls and heat-recovery diagrams, but I believe this term should better encompass the philosophy behind it. It is not my intention to condemn prototypical, sustainable architecture or environmental policy and technical innovation, but rather to suggest that we have been ignoring a key ingredient in what makes us think and behave as we do: emotion. Efforts should be made to address the values that shape the systems that keep us looping on an unsustainable course and to encourage a different prioritisation and worldview, from which could develop pro-environmentalism and holistic, long-term cognitive and behavioural traits.

Figure 4. The Continuous Monument by Superstudio: a critique on culture represented through urban design

7 8

Awe :

Accommodation : Vastness: Pro-environmental Values: Urban Design:

A “SELF-TRANSCENDENT” (YANG ET AL, 2018, P.1) “EMOTIONAL RESPONSE TO PERCEPTUALLY VAST STIMULI THAT CHALLENGES A PERSON’S ORIGINAL CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK” (YAN, 2019) VIA A PROCESS OF ACCOMMODATION. “REFERS TO THE NEUROPHYSIOLOGICAL PROCESS OF UPDATING EXISTING MENTAL ARCHITECTURE WHEN THE CURRENT SCHEMA FAILS TO MAKE SENSE OF A VAST EXPERIENCE” (HOFFMAN, 2020)

MethodMy research will take a transdisciplinary approach to understanding the complex relationship between architecture, experience and resulting values, looking at environmentalism, psychology, and urban design in combination. My research topic requires this approach because it is qualitative and discursive, explored using logical argumentation which does not aim for quantitative results but for a theoretical analysis of ideas asmy topic focusses on social theory and emotion - things not easily quantitatively evaluated.

1. Conduct a literature review divided into three sections: Awe: Identify the origins, triggers, processes, and effects, focussing on the results of psychological experiments in this field to frame my research

Pro-environmental Values: Identify what pro-environmental values are and develop an understanding of current dominant approaches as well as alternatives to pro-environmentalism.

STIMULI THAT IS “…MUCH LARGER THAN THE SELF, OR THE SELF’S ORDINARY LEVEL OF EXPERIENCE OR FRAME OF REFERENCE” (KELTNER & HAIDT, 2003, P. 303)

Design: Ascertain aesthetic principles of awe based on literature, history, and experiments to establish how design can strive to induce this kind of emotional response. This will help build a foundational understanding of strategies to evoke awe that can be implemented in urban design.

2. Consolidate findings by discussing how awe can achieve pro-environmental values, utilising relevant literature to support the case for awe-inspiring urban design.

CONCEPTS OR BELIEFS THAT GUIDE PERSONAL PHILOSOPHY IN FAVOUR OF THE PROTECTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND PLANETARY HEALTH. EXPERIENTIAL ELEMENTS OF THE URBAN FABRIC AND THE ECOLOGICAL INTENTIONS AND STRUCTURES THEY MAINTAIN, FROM ARHITETURE TO LANDSCAPING AND URBAN FORM.

3. Demonstrate how awe can be evoked by suggesting a summative set of design principles to be integrated into urban design.

4. Conclude by discussing the potential of this endeavour, the limitations as well as suggestions of future research.

Definitions Forthepurposesofthisdissertation...

9 10

Awe

Primordial awe is thought to derive from a social context, primarily associated with a threat-based variant of the emotion that was rooted in society as a mechanism for establishing and maintaining social hierarchies (Weber. M, 1978; Keltner and Haidt, 2003; Jones. L, 2020). Gorden et al (2016) highlight that such threat-based variants of awe can induce feelings of anxiety and a perception of reduced control and certainty, however, interestingly it has been noted in other research (Piff et al, 2015) that awe, even if threat-based, still produces positive effects, such as prosocial behaviour.

Though this more threatening “dark side” (Gorden et al, 2016) of awe is still present in certain contexts, in democratic Western societies, awe typically has more positive connotations (Shiota, Keltner and Mossman, 2007), for example with nature or impressive craftsmanship (Keltner and Haidt, 2003) and there are alternative theories suggesting awe was originally a response to nature, which is plausible, as nature remains the most prevalent elicitor of awe (Chirico and Yaden, 2018, p.226).

The cognitive and behavioural effects of awe are extensive and overwhelmingly positive. Those who experience awe are more likely to endorse more ethical decisions and display decreased entitlement as a result of experiencing a smaller sense of self vis-à-vis something greater than themselves, shifting the individual towards wider social collectives (e.g. community, culture, humanity, or nature) (Piff et al, 2015). This could also be due to increased feelings of connection or more collective definitions of the self. Shiota, Keltner and Mossman (2007, p.246) state that thoughts and feelings associated with awe are other-orientated, “stimulusfocussed and self-diminishing, emphasising the perception of the greatness outside the self” which allows people to pay attention to and identify with a larger group.

Shiota, Keltner and Mossman (2007) also explain the process of accommodation: one of awe’s defining features, and highlights that it is not always successful. There may be instances whereby a person’s current mental structures are challenged but not altered to accept the new information being presented, though the paper doesn’t delve much further into the results of this eventuality. Some important points are highlighted: that awe is elicited by information-rich stimuli and that individuals predisposed to awe have an increased ability to alter their schemas and modify mental structures, revising their outlook on the world. Rudd et al’s paper (2012) confirms this and also discusses how awe can expand people’s perceptions of time and increase patience.

Awe has been categorised as a self-transcendent emotion and in some cases, transformative (Chirico and Yaden, 2018). The process of accommodation and the subsequent changes in understanding of the self and the world can give way to profound experiences capable of reshaping the cognitive framework/worldview of an individual. This is reiterated by Maslow (1962) who identified awe as a potential catalyst in a personal process of change. Further research into the potential of awe to impact values shows that awe, when elicited by nature, can encourage ecological behaviour by evoking feelings of CN (connectedness with nature) (Yang etal, 2018). It is assumed that this is thanks to the , 2017) process whereby attention is oriented away from the self and therefore broadens self-concept towards the individual’s current environment . “Awe ... prompts a broader existential approach of life that leads to the inclination to take into account the welfare of other people, the broader community, and nature” (Yang etal, p.1).

LITERATUREREVIEW

Figure 5. Neural Networks (NeuroscienceNews, 2010) 11 12

Pro-environmentalism is a multi-faceted combination of attitudes and behaviours that can be looked at in terms of actions, identity, beliefs, and sacrifice (Zhao et al, 2018). Generally speaking, it is the will and action of people acting not out of self-interest but for the benefit of the environment. Zelenski and Desrochers (2021, p.2) suggest that most pro-environmental values are intrinsically pro-social in that they “require cooperation and they benefit others”.

Though there is much debate surrounding the impact of individuals on climate change since we know that 71% of emissions since 1988 were produced by 100 companies (Griffin, 2017) and governments continually value profit and growth over sustainability, there are also many theories of social transformation that argue for an approach to the climate crisis as a personal challenge (O’Brien, 2018). Far from suggesting that it is up to us as individuals to respond to the damage caused by corporations, O’Brien (2018) points out that as a society we must address the climate crisis from a place of meaning and strong intention.

Ives, Freeth and Fischer (2019, p.208) also argue that sustainability discourse has been too focussed on the “external world of ecosystems, economic markets, social structures and governance dynamics” and neglectful of the “emotions, thoughts, identities and beliefs” believed by many to be the fundamental root to the environmental challenges we face. O’Brien (2018, p.154) explains that the current dominant approach favours technical and behavioural solutions, the output of which are easier to define, mandate and manipulate, and that may be technically feasible but that downplay the complexity and common barriers to effective implementation [figure 6].

Increasingly, environmental researchers are calling for a recognition that our “inner worlds” (Ives, Freeth and Fischer, 2019, p.215) shape our society’s behaviours and systems and that in doing so “might just locate the transformative capacity to bring about the change necessary”. The significance of values and worldviews in the context of environmentalism has been promoted by many who realise that our mindset is crucial when challenging current paradigms and guiding principles (Gopel, 2016; Lent, 2019) as it can be used to “justify ideologies, policies and actions, which in turn may reinforce existing beliefs and worldviews” (O’Brien, 2018, p.165). They should therefore be directional and appropriate rather than unconsciously sustaining negative systems.

“IT IS MORE OFTEN THE CASE THAT CHALLENGING ASSUMPTIONS, QUESTIONING BELIEFS, AND EXPLORING ALTERNATIVES LEADS TO MORE EXPANSIVE AND INCLUSIVE WORLDVIEWS THAT CAN POTENTIALLY TRANSFORM DOMINANT PARADIGMS AND MODELS OF REALITY ... BEING ABLE TO ‘LOOK AT’ RATHER THAN ‘LOOK THROUGH’ ONE’S BELIEFS AND TO QUESTION WHAT IS SOCIALLY OR CULTURALLY GIVEN, RATHER THAN TO CONSCIOUSLY OR UNCONSCIOUSLY ACCEPT THEM AS FILTERS THROUGH WHICH THE WORLD IS VIEWED” (O’Brien, 2018, p.156)

Also in the realm of social transformation, Meadows (1999) describes points of intervention within systems, known as leverage points. The most important are: identifying the rules by which a system works and the goals it follows, the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises and the power to transcend paradigms. The latter two promote addressing at a deeper level, the unconscious societal beliefs and habits that “constitute that society’s paradigm, or deepest set of beliefs about how the world works” (Meadows, 1999, p.17). In order for the entire system to shift, it is these beliefs that must be challenged.

“SHALLOW LEVERAGE POINTS FOCUS ON EXISTING SYSTEM PARAMETERS. THEY ARE EASILY ACTED UPON BUT UNLIKELY TO BRING ABOUT TRANSFORMATIVE CHANGE. IN CONTRAST, DEEP LEVERAGE POINTS TACKLE UNDERLYING WORLDVIEWS, PARADIGMS AND VALUES - THEY ARE MORE DIFFICULT TO WORK WITH, BUT HAVE MUCH STRONGER TRANSFORMATIVE POTENTIAL.” (Ives, Freeth and Fischer, 2019, p.213).

These authors speculate that inner change can influence sustainability by bringing an “awareness of our deepest motivations and experiences” (Ives, Freeth and Fischer, 2019, p.212), though recognise that this alone is unlikely to be enough - it is an approach to be integrated rather than replace current strategies. Meadows (1999, p.18) reiterates that individuals experiencing such a paradigm shift “can happen in a millisecond. All it takes is a click in the mind [...] a new way of seeing”, but for this to effect or be reflected in wider society is another, far more complex matter, that would overshoot my own goals for this dissertation.

Values

“[IT IS THE] DEEPLY INSCRIBED SOCIO-ECONOMIC, POLITICAL, CULTURAL, AND SUBJECTIVE SOCIAL RELATIONS AS WELL AS SOCIETAL NATURE RELATIONS THAT NEED TO BE TRANSFORMED.” (Brand, 2016)

“OUR BELIEFS PLAY IMPORTANT ROLES IN PERCEIVING A CURRENT SITUATION, IN IDENTIFYING APPROPRIATE ACTIONS, AND IN PREDICTING THE EFFECTS OF THESE ACTIONS.” (Nilsson, 2014, p.14).

Figure 6. Spheres of Transformation (O’Brien, 2018)

13 14

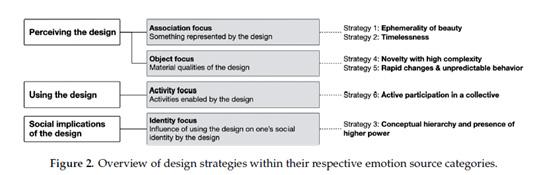

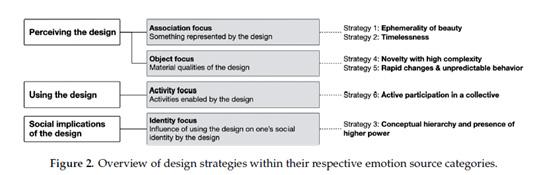

Ke and Yoon (2020, p.1) recognise that “awe is being increasingly explored for its transformative potential and is considered highly relevant to design regarding its effect on users’ behaviors”. This experiment into awe and its elicitors diverges from the majority in that it isn’t conducted in a lab setting but instead relies on a richer qualitative evidence base, using participants’ reports of personal experiences of the emotion to build a set of design principles. Figure 7 summarises the results of the experiment.

Vastness, in terms of height, as an elicitor of awe in monumental architecture was explored by Joye and Dewitte (2016). While awe and ‘smallness’ were reported as the most significant effects, it was also suggested that feelings of entrapment and behavioural or perceived freezing could occur. This can lead to ‘passivity’ in participants (though conversely, Danvers and Shiota (2017) contend that while experiencing awe, we are actually in a state of increased attention and awareness as we try to absorb information from the stimulus).

It is also worth noting that this paper identifies that sheer height is one of many potential triggers, but that ‘vastness’ can be interpreted in a range of ways and could be manifested in detail, craftsmanship or complexity.

Figure 7. Design Strategies for Awe (Ke and Yoon, 2020)

Similarly, Yan (2019) investigated principles of awe-inspiring design from a cognitive neuroscience approach, by identifying elicitors and developing psychological explanations and support of certain aesthetic principles, their efficacy and how this might be beneficial to mental health. Infinity, silence, ‘safe threat’ and nature were the four main themes identified, with each explored in turn. Though investigated differently, the themes identified in both aforementioned papers are similar, with the exception of silence, suggesting that there are indeed certain explicit principles, some tangible, some more abstract, that induce awe. Although Yan’s research (2019) was the result of an extensive literature review rather than having the additional reliability that Ke and Yoon (2020) have in using participants in their experimental research, both make a compelling case for the principles identified.

Nazi architecture [figure 8] reflects the historical exploitation of awe in architecture, using threat-based variants of awe to manipulate and control the beliefs, behaviours and emotions of citizens (Hoffman, 2020) e.g. with the intention of subordinating the population and asserting dominance (Lane. B, 1977). The process of behavioural freezing was exploited to “decrease the body’s capacity for action by overwhelming it” (Gordilla, 2014 ) “to make individuals both physically and psychologically helpless and small, in an effort to weaken (potential) resistance against Nazism” (Joye and Dewitte, 2016 ). Some authors believe that this element of threat is important in in achieving awe (Yan, 2019) while others suggest that it is wiser to avoid elements of design that can trigger it (Joye and Dewitte, 2016). The Nazi party had “a fully developed program of architectural propaganda” (Stuart, 1973, p.253) that drew on neo-Classicism and “traded on simple, emotional impressions created primarily by size” (Stuart, 1973, p.263). The dangers of emotional, symbolic design is made stark by this reflection, though the actual effects and contributions of architecture on the population at the time is difficult to establish, it highlights the way architecture and urban planning can be manipulated to be an expression and “servient instrument of the state” (Stuart, 1973, p.263).

Design

“BUILDINGS ARE NOT SIMPLY EXPRESSIVE SCULPTURES. THEY MAKE VISIBLE OUR PERSONAL AND OUR COLLECTIVE ASPIRATIONS AS A SOCIETY.” (Murphy, 2016)

Figure 8. Volkshalle Interior by Albert Speer (cited by Counterlight, 2009)

15 16

The exploration of literature in these three domains suggests that a relationship could be fostered between the design of cities, the experience of awe and the resulting reflection and psychological change required to appropriately respond to the climate crisis. The case was made for an alternative approach to environmentalism and in the ensuing sections I will discuss how the experience of awe could promote this process in the context of urban design, picking up on the themes discovered in my literature review, and guided by the AWE-S scale developed by Yaden et al (2018). In the final chapter I suggest ways in which awe could be designed into our cities.

Awe and Pro-environmental Values

“AWE, ALTHOUGH OFTEN SCARCE AND FLEETING, SERVES A VITAL ECOLOGICAL FUNCTION.” (Yang et al, 2018)

Awe as a transformative emotion provides experiences that “affect the way people perceive themselves and the surrounding world, thus acting as potential drivers of a personal transformative change” (Chirico and Yaden, 2018, p.227). The multifaceted effects of awe have the potential to provide entirely new perspectives on identity, beliefs and priorities, providing a tool that encourages the cognitive process of a paradigm shift without dictating what the ideal state should be, thus avoiding any unethical manipulation of personal values. This is powerful as it is the values we each maintain that shape the systems we respond to and uphold. This emphasis on values is often understated in more mainstream current approaches that usually take a practical stance that depends on innovative new technologies or policies. It is hoped that the positive effects of awe, as demonstrated through psychological experimentation, lead to the types of changes that align with proenvironmentalism and climate action, and can allow individuals to look at rather than through their worldviews. “This implies

less attention to altering or manipulating people’s behavior, and more on creating the conditions that promote the development and expression of social consciousness” (O’Brien, 2018, p.157). With the intention of these inner most values being altered, perhaps we can break down the systems that bind us in such damaging habits from the inside out.

Vastness and accommodation are respectively the primary and secondary appraisals of awe identified by Keltner and Haidt (2003). The perception of immensity, whether literal or conceptual, leads to the need for the individual to assimilate the experience, so as to understand and process it. This constitutes a central concept of my dissertation in exploring the potential of this powerful emotion to encourage more environmentally aware and responsive mindsets. The neurocognitive process creates new structures to comprehend the world, as well as creating new neural networks and ways of thinking. The more this happens, the easier and more likely it is to occur (Shiota, Keltner and Mossman,

2007, p.947). Assuming a Piagetian theoretical foundation, whereby our understanding of the world, beliefs and value systems are structured with schemas, the ability and willingness to alter these schemas to accommodate for new experiences is fundamental to my proposal. This, as a literal practice triggered by awe, could strengthen a person’s ability to alter their beliefs and actions to better suit the reality of a fundamental need for pro-environmental attitudes.

Interestingly there is also evidence to suggest that self-transcendence can also suppress materialistic, welath or power related values (Zhao et al, 2019) which would further aid in guiding a cognitive shift away from capitalism, which I previously identified as being one of the most damaging worldviews in the West.

These initials facets of awe give rise to other phenomena such as selfdiminishment or transcendence, resulting from the perception of vastness which reduces ego-centric prioritisations of the self and allows the individual to direct more care and attention to others, diminishing one’s own needs and desires (Shiota, Keltner and Mossman, 2007).

In this sense, self-identity is broadened to include more, or in some cases all, of humanity (Cheung, Luke and Maio, 2014). Self-transcendence has been identified as an important factor in the development and adoption of pro-environmental values (Zelenski and Desrochers, 2021) as “climate change is a bigger-than-self problem [and] the key values of interest to climate change campaign are the communal, self-transcending values” (Zelenski and Desrochers, 2021, p.498). It has become standard for most to prioritise short-term personal needs over the needs of the wider community or the planet. The aforementioned paper concludes that those who hold self-transcendent values cultivate strong ecocentrism and proenvironmental intention and behaviour.

CN (connection to nature), a desire to belong to nature rather than dominate it (Zhae et al, 2018), is also enhanced as a result of awe. Accommodation expanding self-concept makes it more likely individuals begin to identify with nature, leading to minimised unecological values (Yang et al, 2018). Personal short-term sacrifice has been identified as a factor in ecological behaviour (Miniero et al, 2014), which awe can foster as it “prompts a broader existential approach of life” (Yang et al, 2018, p.1. citing Cheung, Luke and Maio, 2014). The ability of awe to make an individual feel connected to something larger than themselves has huge power in evoking a desire to prioritise nature and think holistically about the impact of one’s own intentions and actions. Research suggests that CN has a direct positive relationship with ecological beliefs and behaviours,e.g. Mackay and Schmitt, 2019; Whitburn, Linklater and Abrahamse, 2020) and Abrahamse, 2020), so it follows that this connection should be nurtured in the places most deprived of nature – cities.

Awe tends to make people feel as though time is more expansive, which influences their decisions and values and increases patience (Rudd et al, 2012). There is no explicit evidence suggesting such states/

DISCUSSION

17 18

experiences encourage pro-environmental values specifically, though this does not mean it doesn’t contribute. Speaking from intuition, I believe it could in that slowing down has a meditative quality that can lead to existential thinking. In traditional Eastern meditation practice, the purpose is more pro-social than individualistic and can therefore help heal and strengthen connections outside the self, such as to nature (Lent, 2018). As previously mentioned pro-environmentalism is prosocial (Zelenski and Desrochers, 2021) and a connection to nature is essential for strengthening pro-environmental values. I believe there to be a strong spiritual element to environmentalism that is encapsulated by the ability and opportunity to slow down and be present, grounded in reality without distraction or stress. This sentiment is reflected in some studies of awe with statements by participants often referring to feeling in the presence of something greater than the self (Piff et al, 2015). Not only this but Rudd etal’s (2012) experiments found that people who felt awe were more generous with their time, which on a practical level could encourage the individual to volunteer for an environmental cause, especially if nature is the trigger of that awe experience.

Awe and Design

The following design principles, based partly on personal experience and partly on the literature reviewed, suggest ways in which awe might be designed into the urban fabric.

Nature & Biophilic Architecture. Nature, or references to natural situations and elements (e.g. natural/organic forms or fractals) is a primary elicitor of awe (e.g. Stellar etal, 2017). Wilson (1984) suggests that humans are particularly sensorially receptive to forms of nature, making this a powerful elicitor of awe in an urban context. Figures 10-17 demonstrate how natural elements could be incorporated into architecture and urban design.

Nature-informed design: Materiality and Construction Processes. Neri Oxman’s work on ‘material ecology’; a concept/practice that uses natural compounds and processes to build structures.

Figure 10. Chitin (Oxman, 2013)

Figure

Figure

9.

Figure 11. Silk Pavilion 2 (Oxman, 2020)

Figure 12. Aguahoja (Oxman, 2020)

19 20

Plants [figure 13] and trees [figure 14] incorporated into architecture and urban design could elicit awe by bringing diversity, ephemerality and surprise; while incorporating natural elements like water [figure 15] into architecture or through sculpture can create movement and lead people to wonder at the sight of something not usually part of the urban fabric.

Natural Elements.

Nature also provides unique moments that may never be seen again, which can trigger the appriasal of vastness. Urban design could provide space for experimentation; moments for elements such as water vapour and light to play in unexpected ways [figures 16, 17].

Figure 15. Water reflection ceiling in scene from Bladerunner 2049 (Jonni’s creation, 2017)

Plants and Biodiversity.

Figure 14. Bosco Verticale by Boeri (Simon, 2021)

Figure 13. Sheffield Grey to Green Scheme (Susdrain, 2016)

Figure 16. Free-standing waterfall installation (Eliasson, 2016)

Figure 15. Water reflection ceiling in scene from Bladerunner 2049 (Jonni’s creation, 2017)

Plants and Biodiversity.

Figure 14. Bosco Verticale by Boeri (Simon, 2021)

Figure 13. Sheffield Grey to Green Scheme (Susdrain, 2016)

Figure 16. Free-standing waterfall installation (Eliasson, 2016)

21 22

Figure 17. Beauty- water vapour and light (Eliasson, 1993)

Vastness.

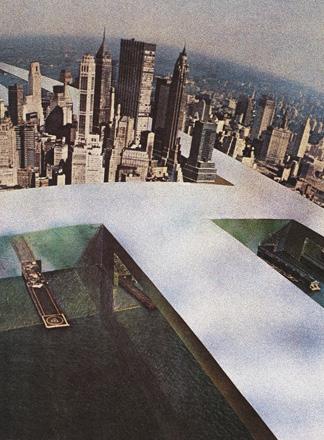

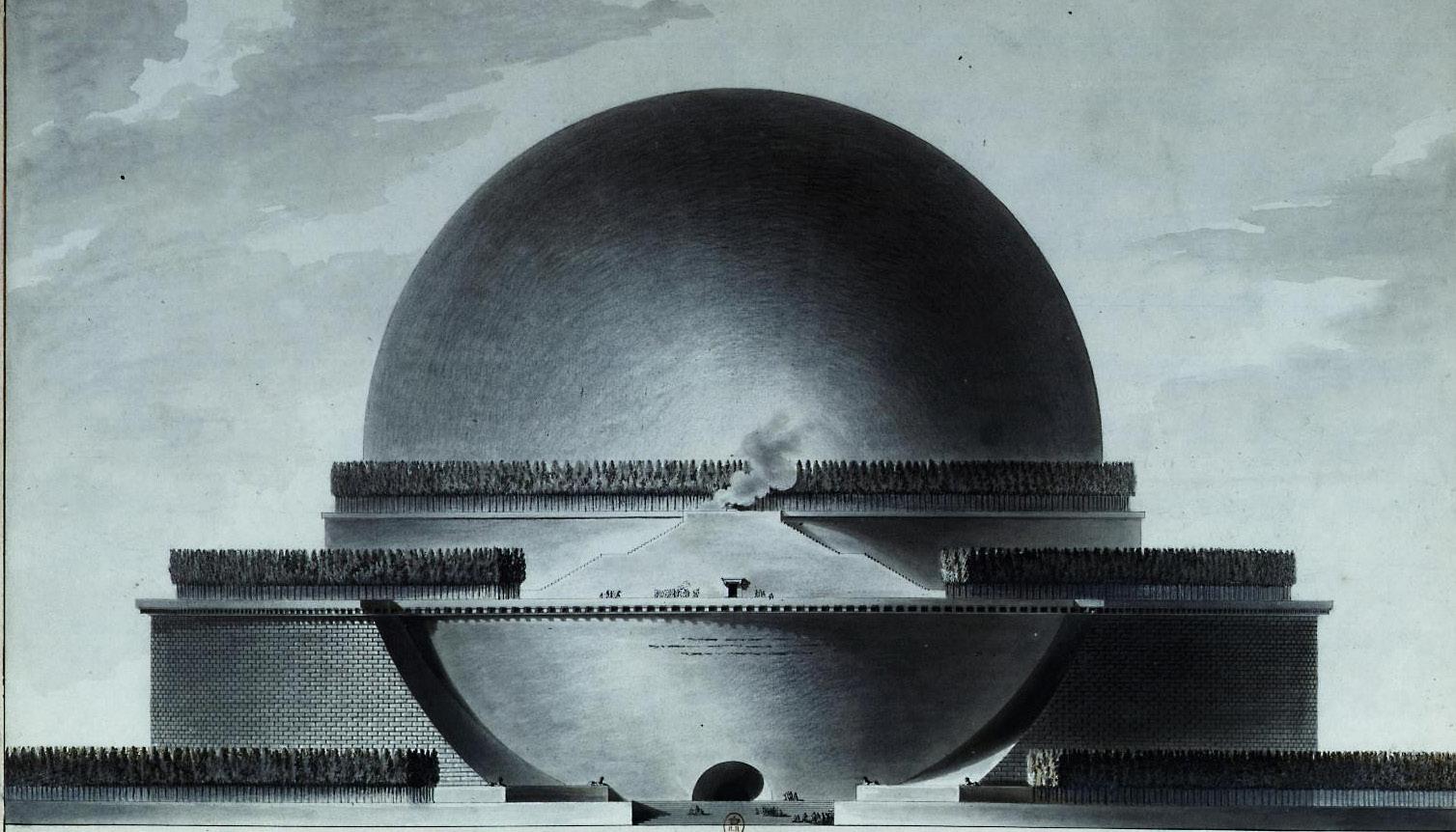

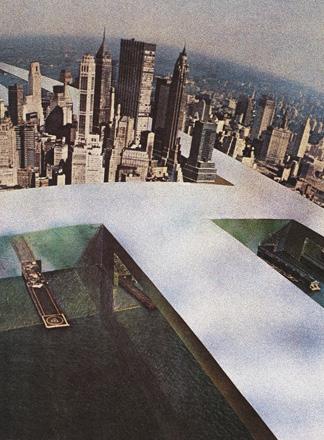

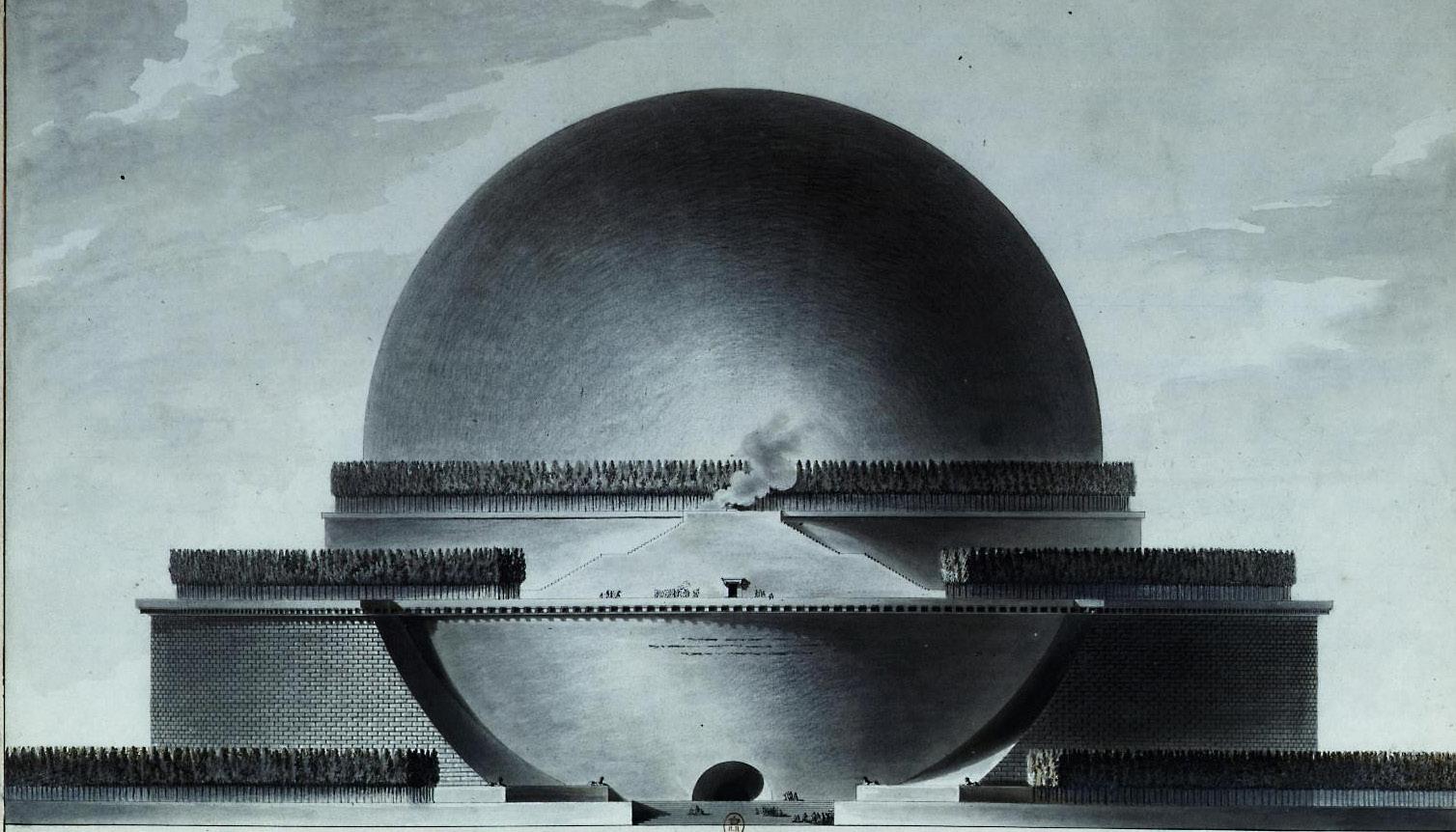

Vastness in its literal ‘macro’ sense can be physical or implied, using scale, perspective, distance and height. It is both an elicitor of the emotion and an actor/reflection of the individuals inner experience and is therefore a key principle, though its application in the real world must be handled thoughtfully, as monumental architecture is not the ideal end goal just because it is vast, as often there are connotations of fear or oppression, not to mention potential wastefulness. Evoking the feeling of an encounter with something vast was a central theme of the Sublime [figure 18]; awe tinged with threat but percieved from a place of safety, that has the power to hurt but does not care to (Burke, 1757). There are opportunities to design for this experience in creative ways, avoiding prototypical monumentality. I believe, based primarily on personal experience, that vast views are a strong elicitor of awe. In cities, they can be provided by infrastructure, walkways [figure 19] or buildings that give inhabitants opportunities to rise above street level. These views could be either over the city [figure 20], to the land or sea beyond it [figure 21] or the sky above it. Efforts could be made for example, to reduce light pollution spilling upwards into the sky so that stars are more visible at night, for people to be reminded of the vastness of the universe.

Richness and detail.

Shiota, Keltner and Mossman (2007) identified that information-rich stimuli can evoke awe by raising the need for accommodation. One way of achieving this could be detail and craftsmanship in the urban fabric, on building facades [figure 22], street furnature or infrastructure [figure 23]. Another method could be through multi-sensory design, for example auditory. Sound sculptures [figure 24] could be exhibited in parks, in the streets or as parts of public spaces and buildings, better protection against noise pollution might allow the sounds of nature to be heard more clearly and even creating spaces of complete silence could provide a profound opportunity for awe (Yan, 2019) in what is typically a noisy and busy environment.

Figure 22. Building facade in Bordeaux.

Figure 23. Rolling Bridge (Heatherwick, 2004)

Figure 19. Kew Gardens Treetop Walkway

Figure 20. View over Paris from the Centre Pompidou

Figure 24. Sound study of Richard Serra sound sculpture (artbykia, 2013)

Figure 19. Kew Gardens Treetop Walkway

Figure 20. View over Paris from the Centre Pompidou

Figure 24. Sound study of Richard Serra sound sculpture (artbykia, 2013)

23 24

Figure 21. Mountains beyond Rijeka

Figure 18. Cenotpah for Newton by Etienne-louis Boullée 2018 (Miller, 2018)

Performance.

Based on the theory that awe may have originated and evolved as a social emotion that was primarily felt in response to other people, their character or actions (Keltner and Haidt, 2003), I feel opportunities for performance and social connection are a vital source of awe in the city. Performance could include people-led direct action [figure 25], street art [ figure 26], exhibitions [figure 27] and performance [figure 28+29] and all can be facilitated by quality open space, active streets dedicated to people rather than vehicles and creative re-use of underutilised or defunct urban spaces.

Meditative Space.

Places of pause, where awe can come from within, is to me something most important to provide in cities where life moves fast, but is often overlooked. Personally, awe has always been somewhat meditative, and has also been studied for its spiritual impact (Van Cappellen and Saroglou, 2011). The triggers for this experience will vary among people but some examples of meditative situations include nature, silence, or the act of walking. For example, forest bathing [figure 31], known as Shinrin-yoku is a traditional Japanese meditative practice that “specifically hones in on the therapeutic effects ... of awe” elicted by the forest (Hansen, Jones and Tocchini, 2017). In cities, meditative spaces are often religious buildings, which tend to focus on spatial qualities, light, shadow and acoustics to create an environment that invites an awe response [figure 30]. I think it would be beneficial to provide more spaces like this, without the religious connotations or justifications.

Figure 28+29. Ice Watch outside the Tate Modern by Olafur Eliasson (Forgham-Bailey, 2014)

Figure 25. BLM protest in Bristol city center

Figure 26. Metelkova (Becki, 2020)

Figure 27. The Cube at bassin des lumières, old submarine base in Bordeaux turned light gallery

Figure 28+29. Ice Watch outside the Tate Modern by Olafur Eliasson (Forgham-Bailey, 2014)

Figure 25. BLM protest in Bristol city center

Figure 26. Metelkova (Becki, 2020)

Figure 27. The Cube at bassin des lumières, old submarine base in Bordeaux turned light gallery

25 26

Figure 30. Tadao Ando’s Meditation Space (King, 2018)

Figure 31. Melbourne urban forest (City of Melbourne, 2022)

ConclusionI have argued that through certain design principles, our cities could better evoke awe to provide a profound experience that could lead to a shift towards the adoption of pro-environmental values. My investigation was highly theoretical, relying on qualitative evidence to ascertain the possibility of this relationship being fruitful. I believe there to be huge potential, as well as recognising these are complex domains and ideas that require a much more in-depth analysis to establish the link suggested.

The literature review suggests that there are some negative consequences of awe, primarily feelings of smallness or a lack of control, in some cases anxiety. This highlights the complexity of an emotion “steeped in paradox” (Bonner and Friedman, 2011) and suggests that it should be applied with caution and a deeper understanding of its effects, though I don’t think these risks outweigh its value. There are many things yet to be explored and some specialists (e.g. Shiota, 2021) warn that to exploit awe’s effects could be a precarious pursuit:

“AWE SEEMS TO PRODUCE A LITTLE EARTHQUAKE IN THE MIND, A MOMENT OF MALLEABILITY OFFERING A CHANCE TO EXPAND AND RECONSTRUCT ONE’S MENTAL MODEL OF THE WORLD. THE MODEL THAT EMERGES DEPENDS ON WHAT HAPPENS IN THE MOMENTS DURING AND AFTER ENCOUNTERING THE AWE STIMULUS. WE STILL KNOW FAR TOO LITTLE ABOUT THAT PHASE OF AWE”. (Shiota, 2021, p.87)

“…WORRIES ABOUT THE ROLE OF AWE AS A POTENTIAL TOOL OF MANIPULATION, A WAY OF CIRCUMVENTING DELIBERATIVE PROCESSES, AND A FORCE THAT UNDERMINES DEMOCRATIC AND EGALITARIAN SOCIAL RELATIONS. IT CONCLUDES THAT WHILE AWE CAN INSPIRE ENVIRONMENTALIST ATTITUDES AND COMMITMENTS, THERE ARE ALSO LEGITIMATE CONCERNS ABOUT USING IT AS THE BASIS FOR ENVIRONMENTALISM.” (Shapshay, Tenen and McShane, 2018)

While in theory the repetition of a certain cognitive process should strengthen it, there are no long-term studies of other aspects of frequent experiences of awe. Little is known about the longevity, as one of its defining features is the novelty and immediacy of the experience. What happens if we begin to experience awe daily? Do the triggers lose their efficacy? Do the benefits accumulate? I would argue based on my own experience that the triggers are varied enough that awe could never be lost for being too common and that the benefits do in some ways accumulate as your mind begins to change as a result of the repeated exposure to the emotion and the cognitive effects it can bring. Some researchers promote the cultivation of it in everyday life (Rudd et al, 2012), and similarly Shiota et al (2007), with support from Thiermann and Sheate (2020), suggests that as the experience becomes more frequent, individuals’ ability to reconfigure their preconceptions is strengthened, meaning repeated exposure and ‘practice’ strengthen our ability to accommodate.

However, there is little empirical evidence to suggest that (beyond my own anecdotes) people who experience awe frequently or intensly have altered perspectives or attitudes regarding their worldviews and specifically, their attitudes towards environmentalism, though I feel strongly that it does. To me awe is a spiritual emotion that deeply influences these inner most values and because it is so often triggered by nature, that is the direction in which my attention and appreciation goes.

There is so much awe present in the world already, some of the design principles are about cultivating the trigger, though many are about making pre-existing opportunities available and accessible, for example giving people the chance see the horizon line or promoting contact with others and nature. Common to all the strategies is novelty, in the form of ephemerality and change, or in the element of surprise, detail, intelligence or originality. Anything ‘vast’ that diverges from ‘the every-day’, that is impressive and contains the general principles identified is likely to trigger awe. I would in future like to delve deeper into the integration of awe in urban spaces, looking more closely and designing specific situations. This work has provided me with a rich foundation from which to do that.

The intersection between the domains of psychology, sociology, urban design and sustainability raises important questions and vast possibilities for further investigation. Prompted by this endeavour, there are some areas of interest to me that I believe could constitute further research, for example: the role of learning, assimilation and accommodation in the context of societal attitudes towards environmentalism; traditional Eastern worldviews and those that typically take a more holistic and interconnected approach to life (looking in particular at Liology and Neo-Confucianism) and how such worldviews could influence an individual’s view of sustainability; conceptual and cognitive revolutions throughout history; the real-life potential and consequence of aweinspiring design; cultural differences in the experience of awe and attitudes towards the environment...

Writing this dissertation has been awe-inspiring in itself at points, triggered by the vastness of ideas and memories of my own encounters with this emotion. It has led me to ask a lot of questions that have no straightforward answer. There is so much more I could say, and even after a year of thinking, reading and writing I still struggle to communicate quite what this emotion means to me. It is one part of a far wider exploration of humanity, philosophy, architecture and sustainability, and I look forward to following where this takes me.

27 28

Figures

Figure

Awe in Monochrome. Own photo from an Olafur Eliasson exhibition, 2019.

NASA (2012) Blue Marble [photograph]. At: NASA [online]. Available from: https://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/imagegallery/image_feature_2159.html [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Mist in the Mountains. Own photo from Wales, 2021.

Figure

ArtReview (2016) Superstudio Il Monumento Continuo. Available from: https://artreview.com/september-2016-review-superstudio/ [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Neuroscience News (2010) Neuroscience researchers discover internal coordinated movements within neurons when connections are strengthened. Available from: https://neurosciencenews.com/two-steps-during-ltp-remodelinternal-skeleton-of-dendritic-spines/ [Accessed 22 February 2022].

O’Brien, K. (2018) Figure 1. Spheres of Transformation [diagram]. In: O’Brien, K. Is the 1.5C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Norway: Elsevier, 30 April 2018, p. 155.

Ke, J. and Yoon, J. (2020) Figures 2 and 3. Design strategies for awe [diagram]. In: Ke, J. and Yoon, J. Design for Breathtaking Experiences: An Exploration of Design Strategies to Evoke Awe in Human–Product Interactions [online] New York: Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 24 November 2020, p.6 [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Figure

Counterlight’s Peculiars (2009) Photomontage from about 1936 showing the interior of Speer’s Volkshalle model. Available from: http:// counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.com/2009/01/monster-dome.html [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Figure

Robertson, G. (2021) General Sherman Tree. Available from: https://www. travelawaits.com/2560344/visit-general-sherman-worlds-largest-tree/ [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Oxman, N. (2013) Shrimpshell derived citosan through deacetylation. Available from: https://oxman.com/projects/water-based-digital-fabrication [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Figure 11. Figure 12. Figure 13. Figure 14. Figure 15. Figure 16. Figure 17. Figure 18. Figure 19. Figure 20. Figure 21. Figure 22. Figure 23. Figure 24. Figure 25.

Oxman, N. (2020) Silk II Video. Available from: https://oxman.com/projects/ silk-pavilion-ii [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Oxman, N. (2020) Aguahoja I Video. Available from: https://oxman.com/ projects/aguahoja [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Susdrain (2016), Fig.6 Seasonal interest is maintained throughout the year – Autumn in the 2nd year of establishment SCC [photograph].

At: no place: susdrain [online]. Available from: https://www.susdrain.org/ case-studies/pdfs/006_18_03_28_susdrain_suds_awards_grey_to_green_ phase_1_light.pdf [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Simson, A. (2021) The Bosco Verticale In Milan in spring, West side. Available from: https://www.zmescience.com/ecology/urban-forest-treetopias-9532/ [Accessed 22 February 2022].

Jonni’s Creation (2019) Caustic Corridor - Blade Runner 2049. Youtube [video] 24 December. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zpFpe_ Heo1w&ab_channel=JoeRaasch [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Eliasson, O. (2016) Waterfall [sculpture]. At: Versailles: Palace of Versailles.

Eliasson, O. (1993) Beauty [installation]. At: London: Tate Modern.

Miller, M. (2018) AD Classics: Cenotaph for Newton / Etienne-Louis Boullée. Available from: https://www.archdaily.com/544946/ad-classics-cenotaph-fornewton-etienne-louis-boullee [Accessed 24 February 2022].

Kew Gardens Treetop Walkway. Own photo from London, 2019

View over Paris from the Centre Pompidou. Own photo from Paris, 2021 Mountains beyond Rijeka. Own photo from Croatia, 2018

Building facade in Bordeaux. Own photo, 2022

Heatherwick, T. (2004) Rolling Bridge. Available from: http://www. heatherwick.com/project/rolling-bridge/ [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Artbykia (2013) Sound study drawn while in Europe. Available from: https:// artbykla.tumblr.com/post/56162473372/sound-study-drawn-while-in-europethis-is-of-the [Accessed 22 February 2022].

BLM protest in Bristol city center. Own photo, 2020.

References

1. Figure 2. Figure 3.

4. Figure 5. Figure 6. Figure 7.

8.

9. Figure 10.

29 30

Figure 26. Figure 27. Figure 28+29. Figure 30. Figure 31.

Becki (2020) No Title. Available from: https://meetmeindepartures.com/ metelkova-mesto-street-art-ljubljana/ [Accessed 23 February 2022].

The Cube at bassin des lumières. Own photo from Bordeaux, 2021.

Forgham-Bailey, C. (2014) Ice Watch by Olafur Eliasson. Available from: https://olafureliasson.net/archive/artwork/WEK109190/ice-watch [Accessed 23 February 2022].

King, L. (2018) Light and Design Strategies. Available from: https://www. laurenceking.com/blog/2018/07/09/atmospheric-light/ [Accessed 23 February 2022].

City of Melbourne Council (2022) Our Profile. Available from; https://www. melbourne.vic.gov.au/about-council/our-profile/Pages/our-profile.aspx [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Aguilar-Luzón, C. et al. (2020) Values, Environmental Beliefs, and Connection With Nature as predictive Factors of the Pro-environmental Vote in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology [online]. 11. [Accessed 16 February 2022].

Ambrose, L et al. (2021) Images of Nature, Nature-Self Representation, and Environmental Attitudes. Sustainability [online]. 13(14). [Accessed 30 January 2022].

Bai, Y et al. (2017) Awe, the Diminished Self, and Collective Engagement: Universal and Cultural Variations in the Small Self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology [online]. 113(2), pp. 185-209. [Accessed 26 November 2021].

Barry, J. and Healy, N. (2017) Politicizing energy justice and energy system transitions, fossil fuel divestment and a “just transition”. Energy Policy [online]. 108, pp.451-459. [Accessed 11 January 2022].

Beddoe, R et al. (2008) Overcoming systemic roadblocks to sustainability: The evolutionary redesign of worldviews, institutions and technologies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences [online]. 106 (8), pp.2483-2489. [Accessed 17 October 2021].

Bethelmy, L. and Corraliza, J. (2019) Transcendence and Sublime Experience in Nature: Awe and Inspiring Energy. Frontiers in Psychology [online]. 10. [Accessed 26 January 2022].

Bonner, E and Friedman, L. (2011) A Conceptual Clarification of the Experience of Awe: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. The Humanistic Psychologist [online]. 39 (3), pp.222-235. [Accessed 22 December 2021].

Brand, U. (2016) How to Get Out of the Multiple Crisis? Contours of a Critical Theory of Social-Ecological Transformation. Environmental Values [online]. 25. [Accessed 20 February 2022].

Brinkerhoff, M. B. and Jacob, J. C. (1999) Mindfulness and Quasi-Religious Meaning Systems: An Empirical Exploration within the Context of Ecological Sustainability and Deep Ecology. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion [online]. 38(4), pp.524–542. [Accessed 10 January 2022].

Burke, E. (1757) A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful [online]. London: R. and J. Dodsley. [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Cheung. W, Luke. M and Maio. G (2014) On attitudes towards humanity and climate change: The effects of humanity esteem and self-transcendence values on environmental concerns. European Journal of Social Psychology [online]. (44), pp.496-506 [Accessed 28 December 2021].

Chirico, A and Yaden, D. (2018) Awe: A Self-Transcendent and Sometimes Transformative Emotion. In: Lench, H. (2018) The Function of Emotions: When and Why Emotions Help Us [online]. No Place: Springer International Publishing, pp. 221-233 [Accessed 01 February 2022].

31

32

De Groot. J and Thøgersen. J (2018) Values and pro-environmental behaviour. In: Steg, L., second ed. (2018) Environmental Psychology: an introduction [online]. New Jersey: Wiley Blackwell, pp.141-152. [Accessed 08 January 2022].

De Witt, A. (2021) World-views as entry-point for personal, cultural, and systems transformation [lecture]. 01 June. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=7gtU4349mF0&ab_channel=ASPRSchlaining [Accessed 31 January 2022].

Dominick, R. (1998) Capitalism, communism, and environmental protection: lessons from the German experience. Environmental History [online], 3(3), pp.311-332. [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Elredge, N. (1995) Dominion: Can nature and culture co-exist? New York: Henry Holt.

Essebo M. (2013) Lock-in as Make-Believe Exploring the Role of Myth in the Lock-in of High Mobility Systems [online]. PhD, University of Gothenburg. Available from: https://gupea. ub.gu.se/bitstream/2077/33724/1/gupea_2077_33724_1.pdf [Accessed 10 January 2022].

Feola, G., Kortwskaya, O. and Moore, M. (2021) (Un)making in sustainability transformation beyond capitalism. Global Environmental Change [online]. 69. [Accessed 20 January 2022].

Foster, N. (2014) Architecture is an expression of values. Interview with Norman Foster. The European, 15 October [online]. Available from: https://www.theeuropean.de/en/normanfoster/9114-the-role-of-architecture-in-todays-society?utm_medium=website&utm_ source=archdaily.com [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Frentz, C. et al (2005) There is no “I” in nature: The influence of self-awareness on connectedness to nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology [online]. 25, p.427-436. [Accessed 11 February 2022].

Goncalves, A. (2021) Perception crisis: why we must question our worldview to achieve sustainability. Available from: https://youmatter.world/en/perception-worldviewsustainability-climate/ [Accessed 03 January 2021].

Gopel, M. (2016) The Great Mindshift: How a New Economic Paradigm and Sustainability Transformations Go Hand in Hand. Switzerland: Springer. [Accessed 10 January 2022].

Gorden, A et al. (2016) The Dark Side of the Sublime: Distinguishing a Threat-Based Variant of Awe. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology [online]. 113(2), pp.310-328. [Accessed 11 November 2021].

Gordillo, G. (2015) Nazi architecture as affective weapon. In: Lambert, L., Vol 2. (2015) The Funambulist Papers [online]. Brooklyn: The Funambulist + CTM Documents Initiative, pp. 54-63. [Accessed 6 February 2022].

Görg, C. et al. (2017) Challenged for Social-Ecological Transformations: Contributions from Social and Political Ecology. Sustainability [online]. 9(7), pp, 1045-1066. [Accessed 24 January 2022].

Griffin, P. (2017) The Carbon Majors Database [online]. London: CDP. Available from: https:// www.cdp.net/en/reports/downloads/2327 [Accessed 2 February 2022].

Grilli, G. and Curtis, J. (2019) Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches. The Economic and Social Research Institute [online]. 645. [Accessed 11 November 2021].

Güsewell, A. and Ruch, W. (2012) Are only emotional strengths emotional? Character strengths and disposition to positive emotions. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being [online]. 4(2), p.218-239. [Accessed 14 February 2022].

Hansen, M., Jones, R. and Tocchini, K. (2017) Shinrin-Yoku (Forest Bathing) and Nature Therapy: A State-of-the-Art Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health [online]. 14(8) [Accessed 23 February 2022].

Hedlund-de Witt, A. (2013) Worldviews and their significance for the global sustainable development debate. Environmental Ethics [online]. 35 (2), pp.133-162. [Accessed 10 January 2022].

Hedlund-de Witt, A. (2014) The Integrative Worldview and its Potential for Sustainable Societies: A qualitative Exploration of the Views and Values of Environmental Leaders. Worldviews [online]. (18), pp. 191-229 [Accessed 28 October 2021].

Hoffman, M. (2020) Exploring the Role of Awe in Architecture as a Pain-Disrupter – A Call for New Research. Journal of Science-Informed Design [online]. Available at: https://theccd. org/article/15/exploring-the-role-of-awe-in-architecture-as-a-pain-disruptor-a-call-for-newresearch/ [Accessed 27 November 2021].

Hummel, D. et al. (2017) Social Ecology as Critical, Transdisciplinary Science –Conceptualizing, Analyzing and Shaping Societal Relations to Nature. Sustainability [online]. 9(7). [Accessed 24 January 2022].

Hurtado, P. S. (2018) From Sustainable Cities to Sustainable People – Changing Behaviour Towards Sustainability with the Five A Planning Approach. In: Filho, W.L., (2018) Handbook of Sustainability ad Social Science Research [online]. London: Springer, pp. 419-434. [Accessed 25 April 2021].

Ives, C., Freeth, R. and Fischer, J. (2019) Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio [online]. 49, pp. 208-217. [Accessed 20 January 2022].

Jones, L. (2020) Losing Eden. London: Penguin Books.

33 34

Joye, Y. and Dewitte. S. (2016) Up speeds you down. Awe-evoking monumental buildings trigger behavioural and perceived freezing. Journal of Environmental Psychology [online]. 47, pp.112-125. [Accessed 26 November 2021].

Kaiser, F. and Byrka, K. (2011) Environmentalism as a trait: Guaging people’s prosocial personality in terms of environmental engagement. International Journal of Psychology [online]. 46(1), p.71-79. [Accessed 9 February 2022].

Ke , J., Yoon, J. (2020) Design for Breathtaking Experiences: An Exploration of Design Strategies to Evoke Awe in Human-Product Interaction. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction [online]. 4 (4). [Accessed 10 May 2021].

Kellert, S. R. and Speth, J. G. (2009) The Coming Transformation: Values to Sustain Human and Natural Communities. Connecticut: Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies. [Accessed 12 January 2022].

Keltner, D., Haidt, J. (2003) Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion [online]. 17 (2), pp. 297-314 [Accessed 01 May 2021].

Knox, P. (1984) Symbolism, Styles and Settings: The built environment and the imperatives of urbanized capitalism. Architecture and Behaviour [online]. 2(2), pp. 107-122. [Accessed 25 January 2022].

Lane, B. (1977) Interpreting Nazi Architecture: The Case of Albert Speer. In: Magnusson, B. and Nylander, C. (1997) Ultra terminum vagary [online]. Rome: Quasar, pp.155-169. [Accessed 15 February 2022].

Lench, H. (2018) The Function of Emotions: When and Why Emotions Help Us [online]. Germany: Springer International Publishing, pp. 221-233. [Accessed 22 December 2021].

Lent, J. (2017) The Patterning Instinct: A cultural History of Humanity’s Search for Meaning. New York: Promethus Books.

Lent, J. (2021) The Web of Meaning: Integrating science and traditional wisdom to find our place in the universe. Canada: New Society Publishers.

Livingtone, L. (2019) Taking Sustainability to Heart – Towards engaging with sustainability issues through heart-centred thinking. In: Filho, W. and McCrea, A. (2019) Sustainability and the Humanities [online]. Switzerland: Springer, pp. 455-467. [Accessed 08 January 2022].

Mackay, C. and Schmitt, M. (2019) Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology [online]. 65. [Accessed 14 February 2022].

Maslow, A. H. (1962) Lessons from the peak-experiences. Journal of Humanistic Psychology [online]. 2 (1), pp. 9-18. [Accessed 23 December 2021].

Meadows, D. (1999) Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. The Sustainability Institute [online]. Available from: http://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/ Leverage_Points.pdf [Accessed 11 January 2022].

Miniero, G. et al (2018) Being green: From attitude to actual consumption. International Journal of Consumer Studies [online]. 38, p.521-528. [Accessed 11 February 2022].

Murphy, M. (2016) Architecture that’s built to heal. TED [video]. February. Available from: https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_murphy_architecture_that_s_built_to_ heal?referrer=playlist-the_emotional_impact_of_archit [Accessed 5 January 2022].

Nilsson, N. J. (2014) Understanding Beliefs [online]. USA: The MIT Press. [Accessed 10 January 2022].

O’Brien, K. (2018) Is the 1.5°C target possible? Exploring the three spheres of transformation. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability [online]. 31, pp.153-160. [Accessed 10 January 2022].

O’Brien, K. L. and Selboe, E. (2015) Climate Change as an adaptive challenge. In: O’Brien, K. L. and Selboe, E. (2015) The Adaptive Challenge of Climate Change [online]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press., pp.1-23 [Accessed 10 January 2022].

Pearsall, P. (2007) Awe: The delights and dangers of our eleventh emotion. Deerfield Beach, Fla: Health Communications.

Piff, P. K. et al (2015) Awe, the Small Self, and Prosocial Behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology [online]. 108 (6), pp. 883-899. [Accessed 07 April 2021].

Piff, P. K. and Moskowitz, J. P. (2018) Wealth, poverty, and happiness: Social class is differently associated with positive emotions. Emotion [online]. 18(6), p.902-905. [Accessed 14 February 2022].

Rivera, G. et al (2019) Awe and meaning: Elucidating complex effects of awe experiences on meaning of life. European Journal of Social Psychology [online]. 50 (2), pp. 392-405. [Accessed 22 December 2021].

Rudd. M, et al. (2012) Awe Expands People’s Perception of Time, Alters Decision Making, and Enhances Well-Being. Psychological Science [online]. 23(10), pp.1130-1136. [Accessed 26 November 2021].

Schlitz, M. M., Vieten, C. and Miller, E. M. (2010) Worldview transformation and the development of social consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies [online]. 17 (7-8), pp. 18-36 [Accessed 10 January 2022].

35 36

Schorsch, J. (2021) A call for green sabbaths. Resurgence & Ecologist [online]. (326), pp.2429 [Accessed 17 October 2021].

Shapshay, S., Tenen, L. and McShane, K. (2018) The Role of Awe in Environmental Ethics. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism [online]. 76(4), pp.473-484. [Accessed 6 February 2022].

Shiota, M. (2021) Awe, wonder, and the human mind. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences [online]. 1501(1), pp.85-89. [Accessed 30 January 2022].

Shiota, M., Keltner, D. and Mossman, A. (2007) The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion [online]. 21(5), pp.944-963. [Accessed 27 November 2021].

Speth, J. G. (2021) A New Consciousness and the eight-fold ways towards sustainability. Spotify [podcast]. January. Available from: https://open.spotify.com/ episode/0QW82H0tBlf8z35YDoBMdI?si=895d9ebf769d4601 [Accessed 12 January 2022].

Stone, T. (2021) Design for values and the city. Journal of Responsible Innovation [online]. 8 (3), pp.164-381 [Accessed 12 January 2022].

Stuart, C. (1973) Architecture in Nazi Germany: A Rhetorical Perspective. Western Speech [online]. 37(4), pp.253-263. [Accessed 03 February 2022].

Sweeting, A. (2015) The Value of Temporary Urbanism in Creating Responsive Environments. MA, Oxford Brookes University.

Thiermann, U. and Sheate, W. (2020) The way forward in mindfulness and sustainability: a critical review and research agenda. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement [online]. 5, pp.118139. Accessed 5 January 2022].

United Nations (2019) World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision [online]. New York: United Nations. Available from: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/ WUP2018-Report.pdf [Accessed 7 February 2022].

United Nations (2021) COP26 Glasgow Climate [online], Glasgow, 31 October – 12 November 2021. United Nations. Available from: https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/ uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf [Accessed 7 February 2022].

Van Cappellen, P. and Saroglou, V. (2011) Awe Activates Religious and Spiritual Feelings and Behavioural Intentions. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality [online]. 4(3), pp.223-236. [Accessed 17 February 2022].

Wahl, D. (2006) Design for human and planetary health: a transdisciplinary approach to sustainability. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environmental [online]. 99, pp-285-296. [Accessed 2 January 2022].

Weber. M (1978) Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology [online]. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Accessed 17 December 2021].

Whitburn, J., Linklater, W. and Abrahamse, W. (2020) Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and pro-environmental behaviour. Conservation Biology [online]. 34(1), p.180-193. [Accessed 14 February 2022].

Wilson, E. O. (1984) Biopilia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Witherspoon. B, Navarrete. D (2017) Mind Over Matter: The Restorative Impact of Perceived Open Space. Conscious Cities Anthology 2018 [online]. 4. [Accessed 06 November 2021].

Wright. O (2010) Envisioning Real Utopia [online]. London: Verso. [Accessed 23 January 2022].

Wu, Q. et al. (2022) The relationship between adolescents’ materialism and cooperative propensity: The mediating role of greed and the moderating role of awe. Personality and Individual Differences [online]. 189. [Accessed 5 February 2022].

Yaden, D. et al. (2018) The development of the Awe Experience Scale (AWE-S): A multifactorial measure for a complex emotion. The Journal of Positive Psychology [online]. 14(4), p.474-488. [Accessed 9 February 2022].

Yan, W. (2019) Neuroscience Informs Design, Now What? Towards an Awe-inspiring Spatial Design. In: Palti, I (2019) Conscious Cities Anthology 2019 [online]. London: The Centre for Conscious Design. [Accessed 29 April 2021].

Yang, Y. et al (2018) From Awe to Ecological Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Connectedness to Nature. Sustainability [online]. 10 (7). [Accessed 07 April 2021].

Zelenski, J. and Desrochers, J. (2021) Can positive and self-transcendent emotions promote pro-environmental behaviour? Current Opinion in Psychology [online]. 42, p.31-35 [Accessed 14 February 2022].

Zhao, H. et al. (2018) Relation Between Awe ad Environmentalism: The Role of Social Dominance Orientation. Frontiers in Psychology [online]. 9. [Accessed 9 February 2022].

Zhao, H. et al. (2019) Why are people high in dispositional awe happier? The roles of meaning in life and materialism. Frontiers in Psychology [online]. 10. [Accessed 8 February 2022].

37 38

Figure

Figure

Figure 15. Water reflection ceiling in scene from Bladerunner 2049 (Jonni’s creation, 2017)

Plants and Biodiversity.

Figure 14. Bosco Verticale by Boeri (Simon, 2021)

Figure 13. Sheffield Grey to Green Scheme (Susdrain, 2016)

Figure 16. Free-standing waterfall installation (Eliasson, 2016)

Figure 15. Water reflection ceiling in scene from Bladerunner 2049 (Jonni’s creation, 2017)

Plants and Biodiversity.

Figure 14. Bosco Verticale by Boeri (Simon, 2021)

Figure 13. Sheffield Grey to Green Scheme (Susdrain, 2016)

Figure 16. Free-standing waterfall installation (Eliasson, 2016)

Figure 19. Kew Gardens Treetop Walkway

Figure 20. View over Paris from the Centre Pompidou

Figure 24. Sound study of Richard Serra sound sculpture (artbykia, 2013)

Figure 19. Kew Gardens Treetop Walkway

Figure 20. View over Paris from the Centre Pompidou

Figure 24. Sound study of Richard Serra sound sculpture (artbykia, 2013)

Figure 28+29. Ice Watch outside the Tate Modern by Olafur Eliasson (Forgham-Bailey, 2014)

Figure 25. BLM protest in Bristol city center

Figure 26. Metelkova (Becki, 2020)

Figure 27. The Cube at bassin des lumières, old submarine base in Bordeaux turned light gallery

Figure 28+29. Ice Watch outside the Tate Modern by Olafur Eliasson (Forgham-Bailey, 2014)

Figure 25. BLM protest in Bristol city center

Figure 26. Metelkova (Becki, 2020)

Figure 27. The Cube at bassin des lumières, old submarine base in Bordeaux turned light gallery