When we began publishing The Lawrence Business Magazine, our goal was straightforward: to tell the stories of the people and industries that make a positive impact on Lawrence and Douglas County, and to highlight its unique character. Few industries capture that spirit more fully than agriculture. It is both our history and our future, and in this issue, we are proud to focus on the ways farming and agribusiness continue to shape our community.

HONORING OUR ROOTS

For generations, families in Douglas County have cultivated the soil, raised livestock, and built businesses that supported not only their neighbors but people around the world. The image of a field at harvest or cattle grazing along the Kansas River is part of our collective identity. But beyond the images is something even deeper: a commitment to caring for the land and passing it on in better condition for the next generation. That stewardship is a legacy worth honoring.

AGRICULTURE IN TRANSITION

Like so much of our economy, agriculture is evolving. The tractors may be bigger, the science more advanced, and the technology more precise, but the values remain the same. Today, local farmers are balancing tradition with innovation; using data to monitor soil health, drones to oversee crops, and community-supported agriculture to connect directly with consumers. These changes are not simply about efficiency; they are about resilience and sustainability in the face of new challenges.

LOCAL IMPACT, GLOBAL RELEVANCE

It is easy to forget, in the middle of downtown Lawrence, how much of our economy still depends on agriculture. From the fresh produce at the Farmers’ Market to the beef raised on family ranches, agriculture fuels our local economy. Partnerships with the University of Kansas and Kansas State Extension help ensure that innovation and education are part of the equation, keeping Douglas County connected to global conversations about food, climate, and sustainability.

AGRICULTURE AS COMMUNITY

What inspires us most is that agriculture does more than sustain us materially; it connects us. It links farm families to new entrepreneurs, young people to seasoned producers, and all of us to the food on our tables. Agriculture builds community in ways that remind us how dependent we are on each other.

LOOKING FORWARD

As publishers and as Lawrencians by birth and by choice, we are proud to celebrate agriculture in Douglas County. This issue honors those carrying forward a rich tradition while embracing change. Agriculture is not just a part of our past; it is essential to our future.

Please note that all our advertisers have a stake in the local economy. Whenever possible, shop locally and resist the temptation to order online. If you find something online, see if one of our local businesses has it.

When we Shop Local - Shop Baldwin, Eudora, Lecompton, and Lawrence (and use Local Services)

- we are supporting those businesses, giving back to our community, and building a future together

Ann Frame Hertzog Editor-in-Chief/Publisher

ON THE COVER LONE STAR 4-H CLUB (L-R)

Back:

Front:

Featured

Copy

Contributing

Contributing Photographers:

Chrystal McWhirt

Peaty Romano

INQUIRIES & ADVERTISING INFORMATION CONTACT: editor@LawrenceBusinessMagazine.com LawrenceBusinessMagazine.com

Lawrence Business Magazine, LLC 3514 Clinton Parkway, Suite A-113 Lawrence, KS 66047

© 2025 Lawrence Business Magazine, LLC Lawrence Business Magazine, is published quarterly by Lawrence Business Magazine, LLC and is distributed by direct mail to businesses in the Lawrence & Douglas County Community. It is also distributed at key retail locations throughout the area and mailed to individual subscribers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reprinted or reproduced without the publisher’s permission. Lawrence Business Magazine, LLC assumes no responsibility for unsolicited materials. Statements and opinions printed in the Lawrence Business Magazine are the those of the author or advertiser and are not necessarily the opinion of Lawrence Business Magazine.

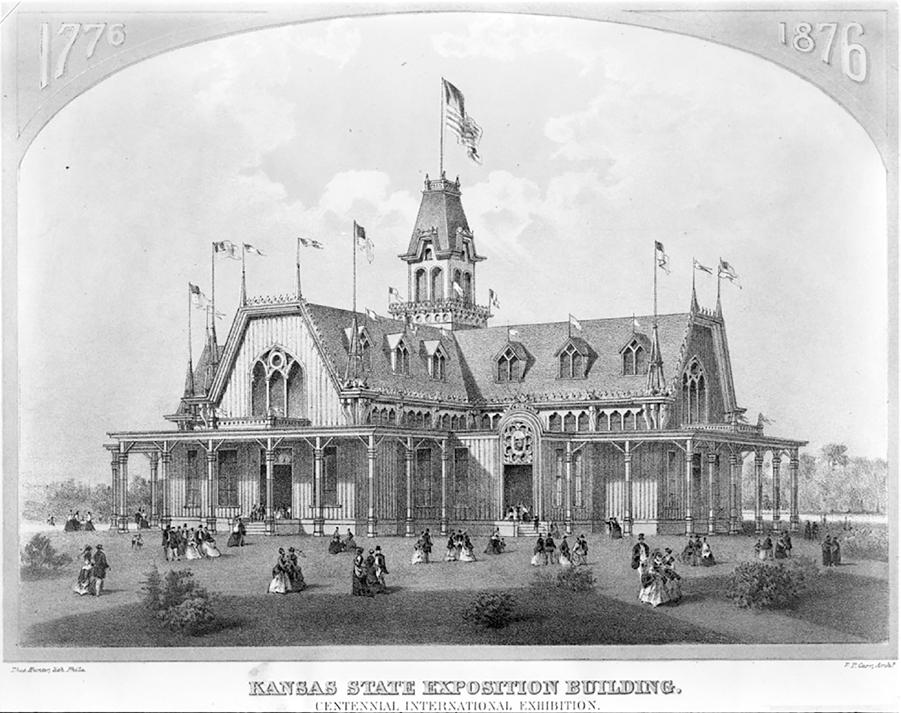

by Pat Michaelis, Ph.D., Historical Research & Archival Consulting

image provided by Kansas Memory, kansasmemory.org

In 1876, the United States celebrated the 100th anniversary of its independence from England with what was commonly known as the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. Its official name was the International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and Products of the Soil and Mine, and it was held from May 10 through Nov. 10, 1876. Approximately 10 million people visited the exposition, with 37 countries participating in the event. Kansas leaders felt it was important to participate and show the manufacturing and agricultural products of Kansas as a way to encourage settlement in the young state. They also thought a positive Kansas presence would offset the negative impression it held because of the recent grasshopper plague.

States that participated built their own buildings, with Kansas’s designed to showcase the state’s exhibits. It had broad verandas that gave it an engaging appearance and was shaped like a cross, with each arm at 132 feet long and 40 feet wide. The building was described by an 1876 Board of State Managers report as follows:

… in each of the angles was a room 30 x 30 feet—giving a total floor surface of 12,560 square feet, about 9,500 square feet of which was devoted to exhibition purposes, the remainder to offices and the necessary private rooms. The total length of the building each way, through the transepts, including verandas, was 160 feet, and the whole height to the top of the cupola, 80 feet. The peculiar construction of the inside afforded a central or rotunda space 80 feet in diameter with a total height of 43 feet, leaving four transepts 40 feet wide by 30 feet deep, with height the same as the central portion; and, as the light came from above, the whole wall-space (368 lineal feet) was left for exhibition purposes.

In 1875 and 1876, the Kansas Legislature appropriated a total of $30,000 for the collection of products to be displayed in the building.

Kansas shared the west wing of the building with Colorado Territory and the north wing with the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

The Kansas Building had a reading room where Kansans and other visitors to the structure could relax in comfort. The floor was carpeted and had sofas, chairs and tables for reading the 150 Kansas newspapers contained in the room. Many of the issues were from July 4, 1876, when publishers were encouraged to include a history of their cities and counties, as well as illustrations. The room was decorated with photos from The University of Kansas, as well as other Kansas locations. The most popular objects in the reading room, however, were tumbleweeds. Several large specimens were on exhibit and generated great interest from Eastern visitors who had never seen them before.

The building had large porches on all sides of the structure that provided shade. Each porch contained a bench that went around the exterior wall so visitors could rest. It also had indoor toilets—one for the “gents” and another for the ladies, which was furnished with a carpet, chairs and sofas.

The exhibits in the Kansas Building were diverse. Several cases contained geological specimens collected in Kansas, while three contained taxidermized birds. One exhibit had silkworm cocoons and silk ribbons from Silkville, a commune located in Franklin County, Kansas.

The report of the state managers contained the following description of agricultural products that were on display:

Above the door a great pair of elk horns were filled with millet, flax, and a huge “tumble-weed.” Antelope heads on either side held wheat. Broadhorns, supporting millet, represented the Texas cattle trade. Directly above the door were pendants of ears of corn, in clusters. A triple gothic window, reaching nearly to the roof, was

lattices with a trailing vine. On each side, tall stalks of corn, reaching nearly to the top were set like pillars. Beneath was a buffalo head, arched by a half-circle of corn pendants. On its either side were other heads, and sheaves—some on buffalo horns. … The opposite doors leading to the office and reading room, were supported by columns of corn on either side, and arched with sheaves set in wreaths over the buffalo head. The arches of the roof were supported by columns of corn in the stalk, and there were pendants of corn ears in profusion.

In addition, the Kansas Building contained all sorts of displays of Kansasgrown agricultural products.

The two most spectacular displays were apples shaped like the U.S. Capitol dome and a Liberty Bell. The dome of apples was 19 feet tall and more than 8 feet in diameter. The apples completely covered the frame that supported them. The replica of the Liberty Bell was popular with Philadelphia residents and hung from the ceiling. It was over 8 feet high and nearly 9 feet in diameter, and made of broom corn, millet and stalks of wheat. The clapper was a gourd that was 8 feet in diameter.

As indicated earlier, the Kansas Building was one of the most popular exhibits at the Centennial Exposition, with thousands of visitors viewing all sorts of Kansas agricultural products. It was a great showcase for the young state. The “Kansas Board of Agriculture Report” included reactions from eastern newspapers to the Kansas exhibit. At the end of the exposition, Philadelphia’s The Times on Nov. 22 wrote that Kansas was “The State That Showed The Best,” and that its exhibit was the largest and best of the state displays, as well as one of the most artistically prepared displays. The July 18 issue of the Kansas City Times contained the following praise for the

Kansas efforts at the Centennial Exhibition:

Of all the places of interest, the grand centers of attraction upon the grounds, none draw more enthusiastic crowds than the Kansas Building, or, more properly speaking, the Kansas-Colorado Building, the Centennial State having one of the four wings. Kansas, however, honesty and justly wears the laurels, the Colorado exhibit being mainly confined to minerals and animals . … Of the contents of the Kansas Building, the grand display of the wonderful resources of the young commonwealth books might be written, while of the glowing encomiums and expressions of delighted surprise encyclopedias might be compiled. It is perfectly safe to say that no one feature of the Centennial has called out more genuine surprise or has bestowed upon it more enthusiastic praise that the Kansas exhibit . … of products that all heartily concede the world cannot equal. In a single stroke Kansas has lifted herself head and shoulders above every State here represented, no other State exhibition being worthy of mentioning on the same day.

The Michigan Farmer ’s reporter at the Centennial wrote on June 16:

The exhibit from Kansas shows what a prairie State can do, and that from Colorado shows forth the wealth of a mountainous region, and the two show a combination of advantages in proximity to each other that, of themselves, independent of any other State or Territory, would make a wealthy and prosperous commonwealth of almost unlimited natural resources. In fact, Kansas and Colorado have shown all the older States how to make an exposition that shall secure to the State the full measure of advantage and distinction occurring from its concentrated labor. p

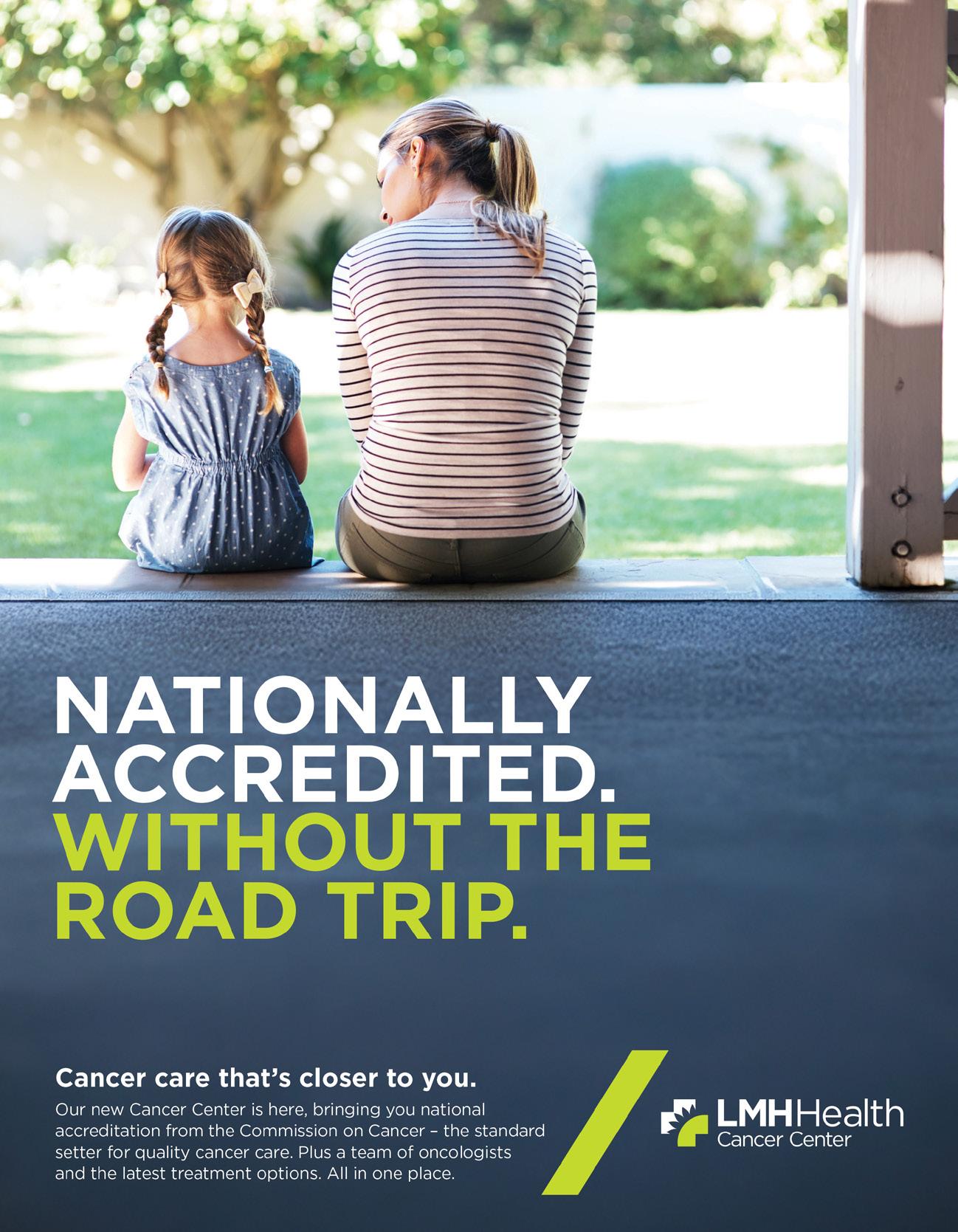

by Autumn Bishop, LMH Health, photo courtesy LMH Health

"Breast cancer, right? You know, there’s not a day that goes by that I am not grateful that I had cancer. Now, I appreciate every day in a way that I never did before."

LMH Health Foundation Board President Gail Vick shared these words she heard during her own cancer journey. I caught my breath when I heard them, not because I was shocked but because it finally put words to the jumble of feelings that had been weighing in my chest.

Now, don’t get me wrong, I didn’t wake up one day and think, “Self? You know what would be great? Cancer.” Trust me when I say that having breast cancer isn’t something I’d put at the top of my to-do list.

I was at the right place at the right time.

"Are you getting your care at LMH? It’s kind of cramped, and you’ll be getting chemo in a room all by yourself."

Honestly, it never occurred to me to look to a different oncology clinic until someone brought it up. I enjoyed the small, private room I inhabited for a few hours each week—sometimes with a companion—and the team of nurses and oncologists breezing in and out. Let’s face it: Not everyone feels the same.

The truth is, the space didn’t reflect the extraordinary level of care the oncology team provides. It was dark. Offices meant for one person had multiple people squeezed in. It could feel crowded. The team was caring for more than 19,000 patient encounters each year in a space that was built to serve 2,400 in 2001.

"Our facility was great, but the needs of our patients simply outgrew our space,” says Dr. Jodi Palmer, hematology and oncology. “We want to provide a pleasant, low-stress environment that’s conducive to healing throughout the entire cancer journey."

It was time for an upgrade.

Renovations to the Cancer Center began in 2024, but the vision and planning started long before that. The LMH Health Foundation began a major fundraising initiative, and the community stepped up. Donors, foundations and community partners contributed more than $7.2 million to support the renovation and expansion.

The transformation is stunning. Side-by-side photos of the old space and the new are like night and day. The Cancer Center expansion and renovation is beautiful. It is bright, filled with light and radiates hope. Improvements to the clinic include:

y more treatment and exam rooms

y a larger waiting room

y an expanded laboratory area

y patient education and consultation rooms

y a dedicated family lounge area.

If you’re getting an infusion, you’ll see the improvements immediately. The treatment bays face large windows, providing natural light and a connection to the outdoors, helping patients to feel less isolated. And let’s be honest, a good view can be a great distraction when you want to escape the reality of cancer treatment.

"I’m proud to say that cancer patients have always been able to find outstanding oncology and hematology care at our hospital, and they’ll continue to find it here in this new, outstanding setting," oncologist Dr. Jodie Barr says.

Cancer brought me through the highest highs and the lowest lows. I made it through and finally saw the light at the end of the tunnel. (No, not that light. This is supposed to be inspirational, remember?)

Life is filled with moments—big and small—that shape who we are and who we become. They stack together to form a beautiful, sometimes tragic and always meaningful symphony.

If cancer fills some of those moments for you or someone you love, trust that you’ll get world-class care close to home, right here in Lawrence at the LMH Health Cancer Center. They fought day and night to save my life, and they’ll do the same for you. p

by

Paula Martin, Founding Board Member and Chair of the Board of Directors and Bev Turner, Executive Director, Children’s Advocacy Center of Douglas County photo by Steven Hertzog

The Children’s Advocacy Center of Douglas County (CAC) provides a safe, child-friendly environment to receive services when there has been a report of child abuse. Our mission is to ensure that children and families affected by child abuse receive a compassionate, community-based intervention through a multidisciplinary team approach to prevent, identify, investigate, prosecute and treat child abuse.

Without a CAC, a child must report his or her experience of abuse multiple times to multiple agencies. The CAC coordinates a multidisciplinary team that works collectively during the investigation. This improves outcomes and reduces stress and further trauma for the child. The multidisciplinary team is comprised of professionals from various fields in Douglas County, including Baldwin City, Douglas County, Eudora, KU and Lawrence law enforcement; the Douglas County District Attorney’s Office; Kansas Department for Children and Families (DCF); Children’s Mercy Hospital and LMH Health; Bert Nash Community Mental Health Center; and The Sexual Trauma and Abuse Care Center. This team meets monthly to review all pending cases, ensuring that nothing falls through the cracks in the investigation and prosecution of child maltreatment cases. Each case begins with a forensic interview conducted by a professional trained in trauma and child development. This one-time, age-appropriate interview is designed to minimize stress while gathering the information needed for an investigation. Meanwhile, a family advocate meets with caregivers to connect them with vital services. We provide trauma-focused therapy to help children and families begin healing from abuse. Medical exams are facilitated to assess injuries and provide treatment. The CAC connects the family with community resources and provides emotional support. Appointments are made, and if necessary, transportation is provided. All services are free for the child and his or her family members. At the end of the initial visit, after the completion

of the forensic interview, each child is invited to choose a comfort item, a small but meaningful part of the healing process. Popular items include Squishmallows, stuffies, games and journals. For family members, there are educational books about sexual abuse and how to talk to your child.

Additionally, a family advocate provides guidance throughout the legal process to ensure families are not navigating the system alone. This advocate meets with the district attorney’s Victim-Witness Coordinator, helps prepare the child to testify against the alleged perpetrator and attends hearings to provide a known and friendly face in the courtroom, since often family members are witnesses and are excluded from the courtroom except when testifying. District Attorney Dakota Loomis says, “The Children’s Advocacy Center of Douglas County is an invaluable partner who serves families affected by child abuse while also helping hold accountable those who target children. Our community is a better, safer place thanks to the tireless work done by the CAC.”

One in 10 children will be sexually abused before the age of 18. To put this in perspective, in a classroom of 30 children, three will be sexually abused during their childhood. Ninety percent of victims are abused by someone they or their family know and trust. Because of factors such as shame, confusion or fear, only about 40 percent of victims report their abuse. Since its establishment in 2021, The CAC has delivered services to 743 children and families.

In addition to the above core services, CAC is expanding its services. It will soon provide Problematic Sexual Behavior Therapy, an evidenced-based program for children who are exhibiting inappropriate or harmful sexual behaviors toward other children. This early intervention helps children understand healthy boundaries, reduces risk and promotes safe behavior moving forward. The Children’s Advocacy Center of Douglas County will be the only provider of this therapy in our community.

Funding for all services is through a mix of federal, state and county grants, as well as donations from private foundations, generous individual donors and community fundraisers.

Our vision is to break the cycle of trauma by restoring lives and futures of children and families impacted by child abuse. If you would like to support the work of the Children’s Advocacy Center of Douglas County or learn more about our work, visit cacdouglas.org

If you are concerned about a child’s safety or suspect abuse, contact the Kansas Department for Children and Families at 800-922-5330, or reach out to local law enforcement. p

by Tara Trenary, photos by Steven Hertzog

Agriculture is key to a healthy economy, and its constant transformation has a big impact on local farms and communities.

Agriculture is fundamental to the American economy, permeating communities well beyond just fields and farms. It nourishes local and worldwide populations while supporting jobs across all sectors. The agriculture industry fuels the nation daily while substantially contributing to its economy. Throughout generations, farming has been a story of community, innovation and resilience.

American novelist, poet and essayist Wendell Berry, also an environmental activist, cultural critic and farmer, once said in an essay that “eating is an agricultural act.” Margit Kaltenekker, agriculture agent with Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service (Douglas County Extension), wholeheartedly agrees. “Fundamentally, we all eat. And if you eat, healthy, robust, sustainable and regenerative agriculture is the sine qua non and the foundation of our economy. This has been true for millennia and was a key vision of our founding fathers, foreseeing a healthy, robust economy based upon agrarian smallholders reaping abundant harvests across this continent.”

The United States is one of the world’s largest agricultural exporters, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, with food and agriculture supporting more than 34 million jobs. People working directly in the agriculture and food sectors contribute nearly $3.8 trillion in economic output and earn wages amounting to nearly $1 trillion. Those working indirectly with the agriculture and food sectors comprise more than 12 million additional jobs, contribute nearly $3.1 trillion in economic output and earn wages amounting to $915 billion.

In 2023, the U.S. Dept of Commerce Bureau of Economic Analysis indicated agriculture, food and related industries contributed $1.537 trillion to the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP), or 5.5 percent. Direct farm output ($222.3 billion) represented only a fraction of that total since valueadded manufacturing, forestry and fishing are part of this economic sector. They also provided 10.4 percent of U.S. employment. Expenditures on food accounted for 12.9 percent of U.S. households’ spending, on average.

In Kansas, agriculture is the largest industry and economic driver, according to the Kansas Department of Agriculture, with 73 agriculture, food and food-processing sectors combining for $61.89 billion in direct output in the Kansas economy and supporting over 260,000 jobs.

Locally, Douglas County has more than 210,000 acres of land use devoted to agriculture, according to Douglas County Extension website. Acres dedicated to crops include 60.4 percent, while 26.6 percent is pastureland, 6.7 percent is woodland, and 6.2 percent is in other uses.

Douglas County figures reported in the 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture and the 2024 Kansas Department of Agriculture Economic Analysis indicate agriculture and agriculture-related sectors contributed a total estimated impact of $663 million in output, or 4 percent of the GDP to the local economy. They also support a total of 2,758 jobs, or 4 percent of the county’s entire workforce.

The good news for Kansas farmers, according to Douglas County Extension, is that economists and others project a $2.6-billion increase in total farm income in 2025, spurred by one-time government payments meant to blunt the effects of recent economic- and disaster-related losses.

However, according to the Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank, even if input prices are softening or yields are in the average to normal range in 2025, commodity prices remain low. Without drought disaster relief expected in 2026, concerns of declining farm income do exist.

“

Farming looks mighty easy when your plow is a pencil, and you’re a thousand miles from the cornfield. ”

– President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Tom Buller, executive director of the Kansas Rural Center, says agriculture is a key innovation for the economy of not only Douglas County but every Kansas community, and doing what they can to make sure it is not only a solid foundation but one that is responsible is extremely important. He says the Center aims to build communities around agriculture, and in turn, agriculture serves the communities it surrounds.

“We really try and support some of those farmers doing things a little differently, trying to sell their food locally rather than the large-scale … folks selling to export markets or moving into more of the commodity streams.” He believes Douglas County is a good example of local innovation: “Douglas County is a leader, so we are trying to share that model across the state.”

Buller says agriculture is the largest industry in the state and “has impacts in every county across the state. And in many rural communities, it is the key driver of the economy. Compared to many other parts of the state, Douglas County has a larger number of smaller farms, and especially those growing fruits and vegetables, and diversified homestead operations. We also have a smaller average farm size than many areas of the state, especially further west, where substantially larger operations tend to dominate.”

He says agriculture can mean different things to different people. “The impacts on the community will be very different if we are talking about small, diversified farms growing and selling products through a local farmers market, or a 40,000-animal confined hog-production facility that pollutes the air and groundwater of a region. The impacts and benefits depend on the localized mixture of what is going on,” he adds.

“The county has somewhat of a mixed production,” Buller continues. He says down in the river valley and in the south are row crops such as corn and soybeans. In the hillier transition areas, there’s more hay ground grazing and livestock. “It just kind of depends on exactly where you’re at, but I think compared to a lot of other counties in Kansas, Douglas County has a more balanced economy. It isn’t dominated by agriculture; there’s a lot of other things going on.”

Douglas County Extension’s Kaltenekker says agriculture, representing 4 percent of the GDP in the county, may seem like small peanuts compared to other economic sectors, but we have to consider that a majority of the production includes grains like corn and soy, which are raw materials that contribute to larger agricultural markets, such as ethanol and feedstuffs for poultry farms or dairies out West.

“When considering the overall importance or ‘value’ of agriculture in Douglas County, we must consider the greater positive impacts that go beyond the economic impact alone, since the value of a healthy agriculture is rooted in the community of relationships across all sectors of the local economy,” she explains. When looking at the entire economy as an ecosystem, with producers being a cornerstone or “keystone species,” within that economy, there are many more metrics that aren’t being factored into the related sectors—marketing, software, banking and finance, trucking or technology industries—that are needed to sustain family farms, she continues.

Kaltenekker says the intergenerational traditions and contributions being sustained through agriculture in Douglas County are invaluable, with many farm families being fourth, fifth or sixth generation and counting. “There’s been a resurgence of interest amongst the next generation of youth to step into agriculture, even more ‘first-generation’ beginning farmers across the country, and it’s up to our community to ensure there is room for them—literally and figuratively.”

Farmland preservation policies and succession planning are essential to keeping agricultural land in production for future generations, she continues. The value of agriculture goes beyond the “homegrown” human, family relationships that are sustained by the land. “It truly begets the culture. That provides depth to our community that’s priceless.”

Traditionally in the past, agriculture fed local communities. “I think we’re seeing a return to that …” Kaltenekker explains. “There are some aspects of people demanding more local produce and wanting a connection to their land and to the community that’s feeding them. I think we’re seeing a return to those roles in our own community. There’s an increasing awareness in Douglas County and demand for locally grown produce.”

Another important aspect of agriculture in Douglas County is the employment it brings into the community. Buller says agriculture can be a driver of job creation, especially smaller scale, diversified farm operations. “Farms are employers. They’re community members. I think a lot of them do a good job in that area,” he says.

Kaltenekker agrees. She says most of the local farms are operating as family farms. “It might be one family farm, but they’re going to be employing other farm workers that are local people … local residents, local citizens, that will be employed by some of the bigger family farms or larger operations.”

Some local specialty crop farms also pull in H2A workers, a program that allows U.S. agricultural employers to bring foreign nationals to the United States to fill temporary or seasonal agricultural jobs when there are not enough qualified domestic workers.

Buller believes one of the key responsibilities for any farmer is stewardship of the land. “And the way they handle that, of course, is different from the kinds of products they’re producing. It not only impacts their own farm productivity over time but also has a lot of impacts on the community in terms of water quality or what kind of runoff is happening from their fields.” He says most farmers strive to be good stewards but warns that paying attention to the best techniques out there is important, as well. Kaltenekker agrees, adding that soil, air and water quality are of great importance. “We have to look at the fact that our social responsibility in agriculture is to take care of the environment and to take care of each other. It’s all interrelated,” she explains. Agriculture provides other net value, such as pastureland that provides carbon sequestration for our air quality and soil health, which leads to better water quality, while water infiltration requires good soil health and good functioning agricultural systems. “It’s all tied together,” she adds.

The World Economic Forum (WAF) explains that the global agrifood system needs to adapt to the impacts of climate change and figure out a way to feed a growing population of over 8.2 billion people. With the agriculture sector being the second largest global emitter of greenhouse gas emissions and responsible for 70 percent of all freshwater withdrawals globally with more than half of agricultural land being degraded, it’s no wonder global productivity losses have gone up to $400 billion per year.

So how are those in agriculture trying to reshape the way it works to make it more profitable? Technology. The wide range of technologies—sensors, drones, robotics and data analytics that optimize resource use, enhance crop yields and improve worker safety—can make ag more efficient, sustainable and profitable, according to WAF. Integration of some or all of these technologies can boost productivity and minimize environmental impact, creating new economic opportunities.

“A key advantage of precision agriculture [technology and data analysis to optimize resource management and improve crop production efficiency] is that it allows farmers to target very precisely applications of things like pesticides and fertilizers,” Buller explains. “It allows farmers to do things like gridsampling of the soil, loading the results into their equipment and applying more or less fertilizer or pesticides, depending on the needs of each area of the field. That information can by synced with harvest data to figure out additional information for tailoring the following years’ applications.”

While precision ag equipment can be expensive, he adds, it can save farmers money by preventing them from overapplying inputs, which are also expensive. “This has a positive downstream (literally) impact in that there is less pollution in runoff that would impact waterways.”

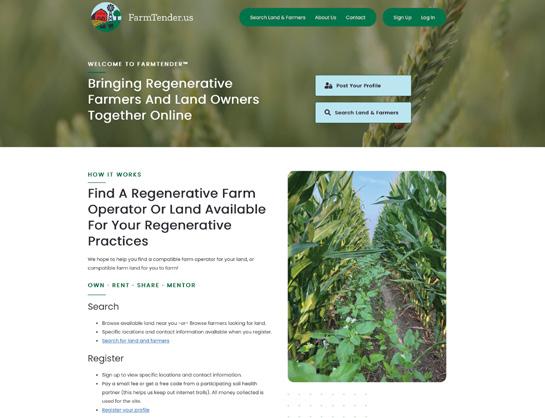

Kaltenekker believes on-farm trials and the use of data in agriculture are key to moving the dial and transitioning more of the production into full regenerative production, allowing for a net benefit on the environment as well as farmers’ pocketbooks. Gabe Brown, South Dakota farmer and author of “Dirt to Soil,” defines the term “regenerative agriculture” as “farming in synchrony with nature to repair, rebuild, revitalize and restore ecosystem function, beginning with all life in the soil and moving to all life above the soil.”

“Part of my vision of what I’m trying to work on,” she says, “is building a peer-to-peer network with on-farm research so that we have more trials in the fields here in Douglas County, where farmers can come and see and meet and talk to each other about what they’re doing with these practices.

“It’s a win-win, it’s just a matter of getting that flywheel going, whether it’s mindset or the biology in the soil, and the rest will take care of itself, because the markets are there.” She believes education and getting the information out there, offering support to those farmers who are listening, are vital. “Farmer-to-farmer education, a support network—behavior change happens best when there’s support.”

However, when asking farmers to make any kind of a change, there are always questions, she explains. What might they need to adjust? What’s the payoff? Is it either going to save them money or help them make money? Is it going to cost money or require new equipment? Therefore, cost-share payments for cover crops help a lot.

Kaltenekker is working with agronomists at Kansas State University and others to create a network and make these on-farm trials happen locally,

“because farmers are putting crops in anyway.” She says it’s just a matter of coming up with a trial that doesn’t cost a lot to put on and then cooperating with farmers to help collect the data. There’s a lot of potential to learn about simple agronomic practices that can have a positive environmental and economic impact,” she says.

“I’m trying to build that network and then collaborate, pull together the farmers who are willing to participate—give up maybe 10 or 20 acres, then deciding, ‘Where can we take this? Listening to farmers and asking, ‘What else could we do to improve soil biological function?’”

Once producers understand how their agroecological systems function and the principles of soil nutrient cycling revealed by new scientific insights to plant nutrition, she explains, they can tweak their existing cropping systems, integrate more livestock and run with it. “It takes a little more ‘whole farm’ planning, but farming becomes more fun with potential for significant payback through reduced input costs alone.” Just as it’s always been, “Farmers are continually going to have to reinvest in new technology to stay ahead of the curve,” Kaltenekker adds.

Douglas County Extension has worked diligently to build relationships with local producers and private ag businesses, while collaborating with local organizations, community leaders and individuals to understand local priorities and build support for Extension programs. Some of Douglas County Extension’s close partners include Douglas County Conservation District, Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Kansas Alliance for Wetlands and Streams (KAWS), Wetlands Restoration and Protection Strategy (WRAPS) and Kansas Forest Service, among others. These agencies help provide technical and cost-share assistance to farmers and ranchers.

In Douglas County, Kaltenekker works closely with the Douglas County Sustainability Office, Douglas County Food Policy Council, Lawrence Farmers Market, Growing Lawrence and the newly formed Kaw Valley Prescribed Burn Association. She says, “We all have a close working relationship promoting soil and water conservation, and building a constituency amongst farmers and ranchers, since preserving water quality in the Clinton Lake Reservoir is essential for our municipal water supply.”

Despite all the challenges in agriculture, Kaltenekker believes the recent renaissance, or recognition, of the value of farmers resurfacing is refreshing. “We have to recognize how hard farmers work to provide these goods, services, food, inputs … and we need to value that,” she says. We in the United States have some of the lowest food prices in the world, even though we are feeling it in the pocketbook right now because of inflation, she adds, “but when it gets back to who’s getting that money, why not pay the farmer direct as much as possible?”

So where is the money going if not to the farmer? According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, when a consumer spends $1 on food produced in the U.S., just 7 cents of that dollar goes back to the farmers. The rest supports the wrap-around industries that deliver, sell and market food products to consumers. This ripple effect of the food dollar stems from agricultural activities and directly benefits local restaurants, supermarkets and other Main Street businesses.

Kaltenekker believes the intergenerational traditions and contributions being sustained through agriculture in Douglas County are invaluable. “There’s been a resurgence of interest amongst the next generation of youth to step into agriculture, and it’s up to our community to ensure there is room for them both—literally and figuratively. The value of agriculture goes beyond the homegrown human relationships that are sustained by the land.”

And there’s so much that can be gleaned from other people and other communities, she continues. “When we recognize agriculture is global and that we’re all trying to take good care of our families, to feed our communities, we all have the same goal. That builds unity, not only in our community but in the whole world.”

Kaltenekker says building networks not only in the state of Kansas but nationally and internationally is extremely important on the local level and something she strives to do every day. “Just participating in those conversations as much as possible is key.”

What does she foresee for the future of agriculture? Increased use of AI (artificial intelligence) and trends away from costly, input-heavy production, opting for “cleaner” biological solutions. “Quality matters from the seed to the table,” she explains. “We need a greater understanding that the future of agriculture production depends on functioning soil biology to produce nutrient-dense, mineral-rich food.”

Kaltenekker says more technological and nutritional research in “food as medicine” is needed to prove the saying “We are what we eat.” “A return to the profitable, well-managed, diversified family farms that support multiple generations will create a prosperous, diverse, robust agrarian economy that benefits a healthy, prosperous populace.” p

The physical work involved in larger-scale farming can be taxing, but so can the less-seen mental struggle going on behind the scenes to keep the business profitable.

by Emily Mulligan, photos by Steven Hertzog

When the work is 24/7/365, then it’s a lifestyle and not just a job. Large-scale crop farming both literally and figuratively covers so much ground that it can be hard to come to grips with the scope of the work for someone who has never done it.

Cultivating and harvesting crops on hundreds to thousands of acres involves physical labor, to be sure. But the mental anguish of risk-taking and decision-making occupies far more of any farmer’s time than the physical work, farmers say.

Trenton Reavis and Lee Broyles are local crop farmers whose families’ farms are in Douglas County and neighboring counties. Steve Wilson’s family owns Baldwin Feed Co., in Baldwin City. All three are integral to Douglas County’s farming community and economy.

Farms with operations the size of Reavis’ and Broyles’ have been on the decline for decades, as 1980s movements such as Farm Aid brought to light.

That isn’t just a 40-year-ago story, though: Between 2001 and 2016 alone, 11 million acres, or about 2,000 acres per day, were converted to nonfarm uses, according to the American Farmland Trust.

With less land, though, demand is still paradoxically high at times, here and abroad, for crops such as wheat, soybeans and corn. So, how do they do it? And how will they keep doing it?

Reavis and his father-in-law farm about 1,300 acres of corn, soybeans, wheat and hay. He moved to the area in 2011 from Indiana with his wife to take on the leading role in the family operation.

Broyles says he has been farming since he was in junior high, when he first helped a neighbor plant oats. “It’s the only permanent job I’ve ever had,” he says. Now, he is in business with one friend and another neighbor, who, together, farm about 2,200 acres of soybeans, corn, wheat, hay and pasture in Douglas and Franklin counties.

Wilson has run Baldwin Feed for 33 years and has seven employees, including himself, most of the year.

“Life on a farm is a school of patience, you can’t hurry the crops or make an ox in two days. ”

– Henri Alain

So many variables factor into a farm’s inputs, outputs and profitability that when combined, they read like the most nightmarish, unsolvable math-class word problem. With wild unpredictabilities that are outside of any one person’s control, the scientific method can’t unite or isolate the variables in any logical way.

The farmers themselves control factors such as whether to till the soil, which seeds to plant and how many, what machinery to employ, when to plant, how to fertilize, how to control weeds and how often to water. All of those things involve costs, both financial and physical, so budget and time constraints guide and affect how decisions are made.

“There is no guaranteed right answer. You have so many factors that are uncontrollable,” Wilson explains.

Indeed, even the soundest logic and reasoning can be obliterated in an instant when the work is directly affected by weather, demand (or lack thereof), market prices and other government decisions at the national, state and local levels.

“Every year, you plan for the best crop you can make. And what happens happens. You worry about what you can change and not about what you can’t,” Broyles says.

Through the past few decades, machinery costs have skyrocketed, wages have risen dramatically, and land costs have increased. Yet some market prices for crops are almost the same dollar amount as they were decades ago.

“The crop price has not appreciated proportionate to what the cost of ground has. We’re able to make it work by increasing yields with hybrids,” Reavis explains.

Broyles says farmers begin every year not having any idea whether they will make any money at all. It isn’t until about December, when the harvest is done and equipment is put to bed, that he knows. And even then, “a lot of years, I turn my cash flow into the bank, and it’s negative,” he adds.

Wilson has a front-row seat to local farmers’ struggles and victories.

“The price they’re getting for their grain hasn’t gone up, not like wages and other costs. It’s pretty tough for them to make ends meet,” he says.

There’s another pressure on farms with Douglas County locations that has nothing to do with crops or equipment: the value of local land.

Reavis says that being near Lawrence and in eastern Kansas, in areas that continue to grow, makes businesses and local governments scrutinize the farmland more closely. The University, other business and residential development from Kansas City have affected land values. With steady market prices that haven’t adapted over time, he says the returns per acre of farmland don’t justify their use compared to what the land could pay out with other development.

“The statistics are sobering. This is prime soil for feeding the world, and some of it is going under concrete,” he explains.

They can’t control the market prices, so what can the farmers do? For one, they can get their arms around their input costs and engage in a strategy game to maximize crop yields on their land, aiming for the lowest input costs for seed, fertilizer, equipment and labor.

Reavis says part of his approach is to focus on soil health. He has planted cover crops to keep the soil in place, restore carbon to the soil and help its microbial life.

“I’m trying to be a student of the soil and place nutrients underneath the plant. When margins are tight, you’ve got to balance this long view to stay in business,” he says.

He also chooses hybrids and varieties of plants that do well in a drier climate, and he applies tactics such as strip-tilling the corn to retain the soil’s natural moisture.

Focusing on his technology and machinery are what Broyles says works best to keep his operation running efficiently.

The technological advancement he says has affected his farming the most is a planter that plants each seed only where there hasn’t been a seed planted before. Computer programming in the tractor records the yield in the field, in every location. The next year, Broyles uses software to program the fertilizer to apply more or less fertilizer in the field according to the data of the previous year’s yields.

“It’s unbelievable what has happened with the technology,” he says.

Number-crunching has helped Broyles and a cofarmer to coalesce around a strategy for upgrading machinery, particularly the combines.

“We don’t buy new. Combines usually have five owners over the lifespan of the machinery. We like to be the second owner in that five. We keep the machinery upgraded but are able to pay for it,” he explains.

Similar to Reavis, Broyles and his farming partners have moved toward a notill approach for the soil alongside the technology and machinery strategies.

Running the feed store, Wilson must stock and offer all the tools, equipment and supplies for farmers taking an infinite number of approaches to their farm inputs. He has become well-versed in a range of tactics and has stayed upto-date through interactions in the store about what farmers need and use.

“We try not to advise, just provide support for what they need to do,” he says. “Nothing ever stays the same.”

Baldwin Feed has a feed mill, grain elevator and building. Wilson says the operation is versatile enough to make as large as a 16,000-pound order of feed, or it can make as small as a 300-pound custom batch of feed—or anything in between.

The DeLong Co. businesses in the Logistics Park intermodal facility in Edgerton have drastically affected farm traffic and operations in the area around Kansas City and Emporia, which Wilson says used to be its own sort of district. Many farmers now have semitrucks for carrying loads and can supply directly to their end users, which has affected businesses like Baldwin Feed. Wilson says he and his staff appreciate their customers and strive to be an integral part of every farm’s team.

About 2 percent of Americans are farmers, but every single American, 100 percent, relies on a farmer each day, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation. The supply chain for farmers, from land to grocery store, comprises about one-seventh of the U.S. economy.

As outlined above, though, profit margins are razor-thin and depend on factors as capricious as the weather. Farming is too big to fail, and that is just from the financial angle. With every American dependent on a farmer every day, failure would mean a lot more than a spending deficit.

“Everybody gives windmills a bad time, but, well, farmers are subsidized, too. It’s good for the economy for farmers to do well,” Broyles says.

Only about 7 cents of every dollar consumers spend on food goes directly back to the farmer. The other 93 cents of each dollar reaches all the wraparound industries that deliver, sell and market the products— from retail and wholesale operations to transportation and finance/insurance sectors, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Farmers and the farm industry are integral to the U.S. economy for the way their dollar moves through it.

“We’re thankful for crop insurance, because it gives us a floor. Even if we grow a reasonable crop, it protects us,” Reavis says. “The objective is to keep production agriculture on a solid foot. The government wants to keep farmers, and that’s part of our equation that gives us peace at night.”

Choosing who they are in business with is crucial to a farmer’s success, Broyles says. Wilson knows his store and his staff are part of each farmer’s and customer’s teams. Broyles says farmers must choose the right sources for seed, fertilizer, feed, etc., to even have a chance at a decent crop.

“Everybody has to be at the top of their game, and they have to care about your game,” Broyles continues.

The same goes for hired help on the farms, which he says has gotten increasingly difficult because of retirements and farm consolidation.

Finding good help is going to be a real problem for all farmers, Broyles says, because people will be able to make the same wage doing work that doesn’t involve extreme heat or as intense of physical labor.

“It’s either what you want to do, or you won’t do it. If you get up in the morning, and you don’t like farming, it won’t work,” he says.

Looking at the broader philosophy of farming, Reavis says he hopes there will someday be a way to recenter farming around rewarding nutritious food. He says it is a noble and worthy cause.

“I would like to see the market pay attention to quality, but it’s going to take some time to come to fruition,” he explains.

Both Broyles and Reavis emphasize that farming comes with rewards alongside all the hard work and challenges.

“People drive an hour and a half to get to their workplace. I take one step outside in the morning, and I’m at work,” Broyles says.

For Reavis, farming is part of his spiritual purpose.

“I’m fortunate to have the opportunity to farm. We want to be profitable and care for the family, but ultimately, I view the land as the Lord’s. I’m just a steward of the land right now,” he says. p

by Jesse Fray, photos by Steven Hertzog

Stressed, uncertain and hopeful. That’s how Scott Thellman, 34, describes farming in Kansas right now. The first-generation farmer runs Juniper Hill Farms north of Lawrence, one of the largest organic vegetable operations in the state.

With 70 acres of produce and a 13-person crew, Thellman has achieved what few young producers have: a sustainable, full-time farming career. But that livelihood is growing harder to maintain.

“We’re being asked to plan out our whole season the year before, and then what was planned out and known either dries up or disappears,” Thellman explains. “The most difficult part right now as a farmer is the uncertainty.”

That uncertainty is driven not only by weather and market fluctuations, but also by new national policies. The recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed by President Donald Trump, revises key provisions of the 2018 farm bill and redefines agricultural priorities through 2031.

And with it come positives and negatives.

OBBBA strengthens the safety net for farmers and ranchers by updating crop insurance rules and expanding commodity support programs. One key change allows farmers who earn more than 75 percent of their income from agriculture to bypass previous income limits, unlocking larger federal subsidies, especially for full-time, large-scale producers.

“Overall, this bill enhances risk management for both small and largesized farms,” says Robin Reid, an Extension economist at Kansas State University. She notes, however, that most payments won’t be distributed until October 2026.

Kansas has approximately 56,000 farms, but the bulk of production comes from a relatively small number of those. In Douglas County, there are nearly 1,000 farms, and 87% bring in less than $100,000 a year, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Yet most federal subsidies go to the largest operations. Since 1995, Douglas County

farms have received approximately $55 million in federal aid, 78% of which has gone to the top 10% of recipients, according to the Environmental Working Group.

That trend is likely to continue, says Tom Buller, executive director of the Kansas Rural Center. He believes OBBBA’s benefits are skewed in favor of the most prominent players in agriculture.

Under the new law, annual payment caps for commodity programs were raised from $125,000 to $155,000. Farmers who previously exceeded the $900,000 adjusted gross income limit are now eligible as long as most of their income comes from farming. The government also increased price guarantees for crops such as corn and soybeans, but these changes primarily benefit traditional commodity growers.

Crop insurance support was also expanded, with the government now covering a larger share of premiums. However, Buller notes that access to affordable insurance remains limited for smaller, diversified farms, particularly those that grow fruits and vegetables.

“There weren’t really any provisions that would help smaller farmers unless they’re growing those [commodity] crops,” he says.

The new law also includes tax breaks designed to help family farms remain in the family. It keeps the federal estate tax exemption at $15 million per person, which means most farms won’t owe estate taxes when passed down to the next generation. It also lets farmers immediately deduct up to $2.5 million in equipment or infrastructure purchases, a big help for those investing in new tractors, barns or other improvements.

A bright spot for farmers of all sizes is the continuation of conservation funding from the Inflation Reduction Act, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation. Programs such as the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) will maintain enhanced funding through 2031. That matters because these voluntary programs help producers implement practices that improve soil health, reduce erosion, conserve water and build long-term resilience to climate and weather extremes. Unlike commodity subsidies, these programs are accessible to both small and large farms, regardless of the crops they grow.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of OBBBA is its $180-billion cut to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP.) These reductions come through tightened work requirements and a freeze on how often SNAP benefits can be adjusted for inflation.

“If this cost is not allowed to increase with inflation, we will see fewer people able to afford the most basic meals for themselves and instead have to make the most thrifty and simplified food decisions, often which end up being highly processed meals instead of fresh, whole foods,” says Emily Lysen, director of development for the Lawrence Farmers Market.

That worries farmer Thellman.

“We have a farm bill that is kind of promoting … specialty crop production, better access to food,” he says, “but then on the reciprocal side of that, we are also facing the largest cuts to SNAP in our nation’s history.”

In Douglas County, where 6% of the population is enrolled in and 30% are eligible for SNAP, Lysen says the cutbacks could deepen food insecurity.

“With cuts and changes to eligibility requirements ... we anticipate fewer SNAP users,” she explains. That translates to less money spent at local markets and with local farmers.

The Lawrence Farmers Market had been a model for success. Its Double Up Food Bucks program, launched in 2016, matched SNAP purchases dollar-for-dollar and recently added a similar match for protein items. Each week, up to $2,000 in SNAP dollars are redeemed at the market, representing about $66,000 in local food sales that could now be lost.

“All SNAP and matching dollars go directly to farmers,” Lysen notes. “That’s $66,000 in fresh, local food not being eaten by our community members.”

Grocery stores like The Merc Co+op (The Merc) are bracing for ripple effects.

“Cuts to SNAP, particularly at this scale, will be deeply felt,” says Seth Naumann, general manager.

“When families lose access to those benefits, it’s not only a personal hardship but a loss of purchasing power in stores like ours and less revenue circulating in the local economy.”

The Merc plans to expand its discount program for low-income customers, MercShare, but private efforts can’t replace federal funding.

“Decreasing access to SNAP harms the families who rely on support, the farmers who grow that food and the community as a whole,” Naumann says.

For now, Kansas farmers continue to plant, harvest and hope.

“We always like to think on the bright side and look forward, not back,” Thellman adds.

Even in uncertain times, that optimism may be farmers’ most enduring crop. p

“Farm to School programs bring healthy, nutritious foods to our school cafeterias, teach our students about the importance of agriculture, and help establish lifelong healthy habits for the next generation.”

– Phil Scott

A trend toward getting to know where food comes from has taken hold, with several farm options for locals to choose from in the Douglas County area.

by Bob Luder,

Most people make weekly trips to a grocery store and purchase meat, poultry and eggs without a single thought given to where it came from. There never is a thought about how it was harvested, processed, packaged and shipped, or how the animals that provided the products were raised. That’s a normal process most of us have been raised on and, most probably, take for granted.

But in these times where words like sustainability, community and organic have become burgeoning concepts that appear to be evermore omnipresent and popular, there’s a growing number of folks who have gained an appreciation for knowing and even having personal relationships with the farmers who grow and raise their food. Lucky for them, there are a handful of options available in the Lawrence area to purchase anything from farm-fresh eggs to rib-eye steaks to summer sausage and jerky. All are raised and sold by farmers on family-owned farms, some of which have been around for generations, others newer, all within a short drive from town.

“Agriculture is the most healthful, most useful and most noble employment of man. ”

– George Washington

Lone Pine Farms, just west of Stull, has been around for six generations of the Wulfkuhle family but didn’t delve into livestock until Lloyd A. Wulfkuhle began raising hogs in the 1960s. After a 25-year break from the late 1990s to the 2020s, Lloyd’s grandson, Jason, restarted the hog business. Today, Lone Pine sells everything from pork shoulders to pork chops to brats, even ice cream (that comes from an outside vendor) through its retail storefront located on the 125-acre family farm.

Amy’s Meats raises beef cows, dairy cows, heritage pigs, meat birds and egg-laying birds, and sells all the harvested product through what owner Amy Saunders calls her “member farm,” in which people purchase monthly subscriptions where they can drive out to the farm about eight miles north of Lawrence and pick up bags of meat, eggs and milk.

Bauman’s Cedar Valley Farm takes a little more effort to get to, as it’s located just outside Garnett, but owner Rosanna Bauman undoubtedly believes the drive is worth it for the homegrown chicken, eggs, turkey and pork she sells mostly through direct marketing. The three-generation, 120-acre farm claims it “works to produce quality food, meaningful work and a better world.”

Though some might not recognize a difference after shopping at the local grocery store their entire lives, these community farmers argue that locally grown livestock, sold at the farm, tastes appreciably better than beef or pork from mega farm-factory feedlots or industrial hatcheries.

“Our typical customer ranges from young families, dads … ” Bauman says. “Fifteen percent of our business comes from single-household natives who remember how good food used to taste. They come for flavor, nutritional impact. And some come just because they know us and know how we raise and harvest our animals.”

Whether better taste or greater nutritional value can be had from shopping for meat, poultry and eggs from local farmers might be subjective, it might be worth a short drive if, for nothing else, to check out the experience of being on the farm, getting to know farmers and learning the story of how the businesses started.

The first thing you’ll notice before even stepping foot into the retail space at Lone Pine is Lady.

Lady is a 2-year-old, 600-pound gilt that resides in a pen sitting just adjacent to the south of the store and is the official mascot of Lone Pine Farms. Hand-fed by Jason Wulfkuhle or one of his employees each and every morning, when Lady doesn’t have her snout sticking through the wire fence entertaining visitors, she’s lying in a bed of mud under a shaded overhang to escape the summer heat.

“We don’t breed her because we want to make sure she sticks around for a long time,” Wulfkuhle says.

At one point back in the day, Lloyd Wulfkuhle had up to 600 sows on the farm, and his wife sold processed pork out of freezers in her dining room. Today, Jason Wulfkuhle raises a more modest 30 sows, along with six boars, and operates out of the much more convenient farm store. He says a pig can “farrow”— or, give birth—2½ times a year. A typical litter for a sow is eight to 12 piglets, which can grow from 2 pounds at birth to 300 pounds in six to seven months.

Wulfkuhle says he sends his hogs to a U.S. Department of Agriculture-certified processing plant in Smithville, Missouri, and the pork returns packaged and ready to sell.

“We supply a restaurant in Lawrence,” he says. “Everything else is sold here in our store. We go through 300 to 350 hogs (per year) through our freezers in here. We cut everything but the organs. We have pigs feet, hocs, everything you can imagine.”

Lone Pine also has two chicken pens—an outdoor pen and indoor nesting pen—and has around 70 chickens. Wulfkuhle says the farm sold 1,200 dozen eggs last year.

People come from far and wide to Lone Pine Farms for an opportunity to purchase top-grade pork, eggs and more.

“People come all the way from Alma (Kansas), Topeka, Lawrence, Kansas City,” he says. “We average 30 to 40 customers a day.”

Wulfkuhle says Lone Pine strives to keep prices competitive with local grocery stores.

“Our prices may compare to the grocery store,” he says, “but our quality is not comparable.”

Outside vendors sell other goods at the farm store, including beef, milk, cheese, honey, handmade goods and, one of the most popular offerings, ice cream from Flint Hill Pints, out of Alma.

Wulfkuhle also farms crops and sells seed in Douglas County and seven surrounding counties. Lone Pine is part of the Kaw Valley Farm Tour, which takes place Oct. 4 and 5, and the farm will offer hayrides, pig-viewing and grilling pork.

“We’re just going to keep doing what we’re doing,” Wulfkuhle says. “Riding the wave.”

Amy Saunders can’t help but laugh at herself sometimes.

“If there’s a hard way to do something, that’s what I do,” she says with a chuckle inside the small still-under-construction building that houses several coolers of all sizes along with hundreds of cloth bags that hold meat for members of her food subscription service, Amy’s Meats at the Homestead.

In addition to running the farm, Saunders is mother of six, five of whom she homeschools (her oldest is grown, has his own farm and raises lamb offered by Amy’s Meats). All meals for the family of eight—her husband is a pipefitter for a local union—are cooked at home. So she understands busy and knows how to budget.

In addition to the cows, pigs, birds and two horses roaming the pastures and hillsides of her 53-plus acres, she rents more land to supplement needs— she has two hives of bees on the property.

“They’re the pollinators,” Saunders says. “They keep everything growing and going.”

She takes great pride in raising her livestock humanely. She says it can have a positive impact on the flavor of meat postharvest.

“We’ve always raised our livestock differently,” she says. “We focus on quality of life. They graze on grass. They’ve got fresh water and hay. We’ve always done it this way.”

Buying feed also gives Saunders an opportunity to support fellow neighbors, she says.

She also has three hoop houses where she grows heirloom vegetables.

“They’re beautiful and extremely hard to grow,” Saunders explains. “We have tomatoes that are purple and jet black inside that have a whole different flavor. And we have lettuces that aren’t green but red and purple.”

The beauty of her member farm model, she says, is that every customer

owns his or her buying power. They simply pick a bundle size and pay that corresponding amount monthly. And they can pick and choose what kind of product they want in the bag.

“It’s just like a grocery cart,” Saunders says. “It’s a year membership, so people can buy $1,000 worth of meat but not have to pay it all up front.”

There are three levels of membership, she explains, all paid monthly on an annual basis: $50, $150 and $250. She says most families join at the $150 level, which is not enough to feed a family of four for a month, but it’s a start.

She says she currently has 75 members, feeding 300 people.

“My customers are my bank,” Saunders says. “Everything’s on a cash basis. I know I have X amount of money every month. I know I can meet expenses. The consistent thing is, those who think food is important, they’re in.

“Doing this 19 years ago was a leap of faith, but I’m really glad I did it,” she adds.

The farm also has hosted weekly “farm-to-fork pizza nights” on Friday nights during mild-weather months, but that was put on hold temporarily after the weight of snow from January’s blizzard collapsed the roof over the pizza oven.

The Bauman family has been on its farm, seven miles west of Garnett, near Cedar Valley Reservoir, for 25 years, having replaced a family of displaced farmers at the turn of the century. In addition to raising chicken and duck eggs, turkey, beef and pork, they operate two processing plants, one in Ottawa and one in Garnett.

Absolute numbers are a challenge to determine, but Bauman reckons she has somewhere between 500 to 1,000 “layers” (chickens relied on for egg production) and around 5,000 “broilers” (those harvested for poultry products). She says she also has around 60 pigs and 40 head of cattle.

Bauman’s Cedar Valley Farms also is a sustainable enterprise, but Bauman is first to admit the reasons for that are entirely practical.

“We couldn’t farm that many acres, and the only option we had really was sustainable farming,” she says. “We couldn’t afford any of the fertilizers or chemicals a lot of farmers around here use when we started.”

All Bauman’s livestock grazes on pastureland, she explains. Most of their acreage also is tillable, meaning it’s ready to be worked and planted without any removal of trees or rocks.

“Organic farming was the way to go,” she says. “We have all non-GMO (genetically modified organism) crops and plants. It’s all natural.”

Bauman says she sold her products mainly through wholesale during the first 10 to 15 years on the farm but grew frustrated with the corporatization of pasture-based products. So she switched to direct marketing, which seems to be going well, at least for now.

“One thing we’ve learned after so many years is that we just don’t give up,” Bauman says. “It never gets any easier, but we don’t quit.

“Nature is diverse, people are diverse, and we’ve been fortunate to capitalize on those strengths. We believe this farm has been a work of God. That keeps us pushing forward,” she adds.

During the regular market season, people can shop the Bauman’s Mobile Meat Market at the Overland Park Farmers’ Market on Wednesday and Saturday mornings, as well as The Olathe Farmers Market on Saturday. There is also a preorder shop where customers can reserve meats, dairy and baked goods, which sometimes do sell out. p

Douglas County’s 4-H club introduces young farmers not only to the value of hard work but also to the world of business.

by Julie Dunlap, photos by Steven Hertzog

The land that makes up Douglas County, Kansas, has a rich history of supporting crop farms and livestock stretching back centuries before European settlers began planting their own roots in the area. Today, many families currently farming in and around the county work the same land their ancestors cultivated since first arriving in the Kansas territory.

For a special group of future farmers, this deeply rooted talent and affinity for growing the vegetation and animals that nourish hundreds upon hundreds of people each year germinates at an early age and lasts a lifetime. These young entrepreneurs are feeding, cleaning and caring for livestock up to 10 times their own size as they prepare for fairs, shows, livestock auctions and other buyers in the market for quality, locally raised animals.

Raising livestock isn’t just a hobby for these youth. It’s a serious introduction to the world of business, complete with startup costs, long-term investment decisions, scientific discoveries and invaluable life lessons.

Douglas County’s 4-H club has provided support and mentorship to young agricultural entrepreneurs for generations as they hone their skills and find their passions within the business of agriculture.

“Most farmers know that their children’s future will probably not be in agriculture, but they have a hard time imagining a different life.”

– Abhijit Banerjee

“When kids find their spark, you find them really wanting to be with that animal—it’s what they look forward to first thing that morning and when they get home from school,” says Nickie Harding, 4-H youth development agent for the K-State Research and Extension Douglas County with Kansas State University, of the steadfast draw of area youth to the livestock projects.

The 4-H Youth Livestock program fosters responsibility, time management, community and financial literacy as kids work under the guiding values of Head, Heart, Hands and Health (the four “H”s central to the organization) to raise their animals.

Harding lights up as she describes the joy and self-confidence these kids find in connecting with their animals, “learning more about that animal, not just to exhibit but really knowing and learning about that animal and the benefits of taking care of something other than yourself.”

This past summer, 173 kids in Douglas County participated in the Douglas County Fair’s livestock competition. While some participants chose to raise their various livestock—cattle, horses, pigs, poultry, goats and more—for show, many chose to raise them for the business of breeding or selling, with 118 animals being sold at the end of the week.

Sisters Ruby Hill (age 13) and Molly Hill (age 15) raise their own livestock on their family farm, representing the third generation of their family tree to compete through 4-H in the Douglas County Fair.

“We’ve always grown up doing this, we would go to the nearby farm and help them out with their cows,” says Molly, citing the joyful memories she has as a young girl. “I remember when [my brother] was at the fair, we would lay on my brother’s steer, running around like we had no care in the world.”

Now responsible for their own half-ton animals, the carefree days of playing with their brother’s cattle are long gone. Today, their daily regimen includes morning and evening feedings, twice-daily washings and groomings, clearing droppings from the pens, pouring fresh water into the drinking basin and working with their cattle to exercise and halter them—no matter what the Kansas weather presents. The joy, however, remains.

“It’s not easy, but we love doing it,” Molly beams.

Siblings Jasper Clark (age 14), Evie Clark (age 13) and Jett Clark (age 9) raise and show cattle year-round, selling select steers and heifers at the Douglas County Fair auction. Like the Hill sisters, this trio of siblings rises early every morning to maintain their cattle rain or shine. The workload is large, but the bond they share with each other and with their animals is priceless.

“We work together way better than most siblings,” Evie says of the kids’ family business.

While the dozen or more shows they participate in throughout the year might spark some healthy competition among the siblings, Jasper emphasizes that family comes first, saying, “A win for one of us is a win for the family.”

Makenzie Fishburn (12) with Pua, her Berkshire Pig, a gil and Charlie Fishburn (8) with Maybe, his Duroc Pig, a barrow

Families may breed their own animals or purchase their animals from trusted ranchers, who sell calves for people like the Hill and Clark kids to raise for show. The calves are usually 6 to 8 months old at the time of purchase, weighing in at roughly 500 pounds.

“I get a new steer every year,” says Ruby, who feeds and cares for each calf herself each day as part of her business plan until it has nearly tripled in weight. “I sell him at the fair, and I get money, and then I save that money to buy another steer.”

As of press time, the price per pound for live cattle is hovering around $3 per pound. For Ruby’s roughly 1,300-pound steer, this would likely result in a sale worth about $3,900.

There is plenty of overhead that goes into raising livestock. Expenses vary greatly by species with food, facilities, grooming supplies, utilities, transportation, veterinary care and training gear—and it adds up quickly, with an animal’s health or lifespan not guaranteed.

Still, the payout can rival or surpass any part-time job many young teens are able to find thanks to the generosity of the county’s dedicated 4-H supporters, who finance special “add-ons” for the kids bringing livestock to auction. Patrons of the Douglas County Fair are given the option to bid on the show animals, offering a premium on top of the market rate for the seller. More than 100 area businesses and individuals donate to the fair to help cover these premiums and encourage local agricultural entrepreneurs in training to continue learning and working the industry.

Cattle aren’t the only animals in this business world.

“Poultry is our largest enrollment,” Harding says. “You don’t necessarily have to live outside of town—the space requirement is small, everything

is pretty minimal, plus you can create an egg business. We have kids who sell eggs.”

Meat chickens can sell at the fair for $500 per set of three, while swine currently sell for just under $1 per pound and typically range from 220 to 320 pounds.

Makenzie Fishburn (age 12) and her brother, Charlie Fishburn (age 8), have been raising swine as part of their 4-H livestock projects, taking in 30-pound piglets and helping them grow into 250-pound, prize-worthy swine in roughly six months.

Makenzie says she has learned new skills and adopted different practices over the five years she has been raising swine, modifying nutrition, exercise routines and training techniques along the way.

“Definitely walking my pigs every day,” Makenzie shares of one of her most impactful discoveries in training her animals for shows, “because anytime you don’t work with the pigs, they won’t listen very well.”

Jett, who is in the early years of raising cattle, has been able to take on more responsibility as he grows taller and is more capable of performing some of the physical labor.

“I thought, ‘Whoa! There’s a lot of new things happening here,’” Jett says of his current project versus last year’s. “You have to work with your cow every day, or it’s not going to be a good cow.”

In addition to raising swine, Makenzie has a special interest in raising cattle and looks forward to devoting more time to the steers and heifers (and their progeny) she has become attached to over the years.

“There’s quite a bit that I like to do with the cattle and spend time with them,” she says, adding with a laugh, “I like to lay on my animals and snuggle them.”

Just as managing the profits and losses associated with raising market animals provides hands-on experience in the world of business ownership, parting ways with a beloved animal as it heads to market provides a unique experience in the life cycle.

“It is very hard. It doesn’t matter if it is a 7-year-old or an 18-year-old, it never is easy. But they know that is what they’ve decided to do,” Harding says. “If you walk around as you get closer to the end of the fair, you will see kids saying goodbye to their animals. Often, once they go through the ring (for exhibition), they will leave from the fairgrounds and are transferred to a location for market.

“I live in the moment and then deal with it afterwards,” Makenzie says.

Jasper agrees. “You create a connection with them for so long, and you’re with them every single day, but then they’ve got to go. It is sad, but it’s also …”

“... a life lesson,” Evie finishes for her brother.

The kids who struggle with the final farewell often find breeding to be a more gratifying business venture than raising livestock for market.

“I showed a steer one time, and I bawled my eyes out,” says Molly, who now raises breeding heifers and is learning the science of artificial insemination (AI) to be able to breed her own. At this point, Molly says she is too short to be able to perform the AI procedure on her own, as it takes a great deal of physical strength to administer the insemination straw. But she can be hands-on in the selection process, learning an entirely different aspect of the life cycle through her animals.

“I’ve gotten to see eggs through a microscope, which is really cool,” she says, adding that she is able to assess the expected progeny differences (EPDs) of potential parents to breed a more ideal animal. “If the dad has a really clean neck, which is what you’d really want in a show cow, and the mom is a really big build, maybe I want to put those two together.”