ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

“‘The problem was “What shall we do with the Negro?…now the problem is “How can we get more of them?”’

Andrew Carnegie, Howard University, 1907

My work has always looked internally, through the lens of my immediate community. And in my community, basketball is king. Difficult to assess or analyze statistically, it is something taken for granted. Both an "if you know, you know" accepted truth within the community, and a well-worn stereotypical trope outside of it. Teenagers and twenty-somethings maintain a connection to the game, either through direct play, or aesthetic cultural references. Middle-aged men who grew up playing the game, continue their allegiance as ticket holders and coaches of children who play. Elders, who “used to be a beast back in the day”, will tell anyone who listens how the game was so much better back when. Meanwhile, the jaws of high schools and universities, local governments, law enforcement, sneaker corporations, non-profit founders, coaches, scouts and common citizens alike all salivate to watch who's next. But what does it all REALLY mean?

In 1891, Luther Gulick tasked his young assistant James Naismith with creating a game that could bring young, white boys back to Christianity. A game that could reverse years of "Victorian domesticity" and promote manliness by utilizing physical fitness to enhance spirituality. This philosophical concept would become known as "muscular christianity", and Naismith would fasten peach baskets to a beam randomly 10 feet high, merge the teamwork necessary in football, with the finesse and passing necessary other so-called primitive games, and ask players to toss a laced, leather ball into the basket. Several rule changes later, basketball was born.

Today, basketball is one of the most popular sports in the world. As recently as 2022, The Fédération Internationale de Basketball, better known as FIBA, estimated worldwide players at 450 million. In American high schools, over 892,000 student athletes played. A whopping 55,498 student athletes played basketball for the NCAA that year. Even fewer make it to the pros, with 720 players playing at least one game in the NBA and WNBA during the 2022 season. These numbers are impressive, indicating a global game once thought incapable of replacing football or baseball in the hierarchy of American sports. Anywhere in America where Black people form a majority, the game is even more ubiquitous. Possibly the biggest cultural force after music and food, basketball has arguably become a pillar of Blackness.

In the sixteen years between its inception and when the first referee and spectator basketball game between all Black teams took place in Washington DC, basketball belonged to white society. Endorsed by President Theodore Roosevelt, a sport once thought “for sissies” became a focal point, and universities, churches and athletic clubs created a world around it. Black teams were banned from the Amateur Athletic Union and NCAA, while Black players were not eligible to play or coach against white teams in city leagues. Through the determination of Naismith’s only Black protege, John McLendon, and the actions of a handful of entrepreneurial Black leaders in New York, DC and Pittsburgh like Will Madden, Edwin Bancroft Henderson and Cumberland Posey Jr. , basketball would slowly spread through Black communities. It would not be until 1907 that basketball would become a mass-scale tool for physical education, Black collaboration and collective economics. Today, the hold that basketball has on the “imagined community” as a whole, remains formidable. But lost in the frenzy of AAU tournaments, endorsement deals, hip-hop shoutouts and celebration dances are the political obstacles of a sport dominated by the Black body.

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

continued from page 1

The nature of basketball as a cultural machine is complicated by historical structures of slavery, racial segregation and white supremacist terrorism. These realities are well-documented and widely accepted. But less visible forces include the "segregation of risk", created by the racist housing convenants, lending practices, renting preferences and home valuation protocols that created the white middle class and the Black underclass. These forces combined with low-wage occupations, second-class educational infrastructures, and a hostile police presence to further alienate predominantly Black communities from everyone else. As a direct result, basketball becomes much more than a game, or an opportunity to participate in the aforementioned physical fitness craze that took over the country. Basketball became the newest "way out", an industry for corporations to exploit the growing ambitions of upwardly mobile Black Americans to depart the communities systemically left behind. Talented athletes from these communities are often confronted with a choice between escaping or engaging in the struggle. Become a Black Panther, or work on your jumpshot and become a Blue Devil?

In her book Black Scare/Red Scare : Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States, author and activist Dr. Charisse Burden-Stelly theorizes the merging of both Cold War era anti-communist paranoia and Jim Crow era fear of a Black rebellion with the consistent suppression of Black radical left and anti-capitalist politics. These ideas were understood as a necessity to protect "American patriotism", deeming anything in opposition as communism, and therefore, anti-American. Any and all Black citizens could be reprimanded or worse for anti-Americanism, but the Black leaders, entertainers, athletes and celebrities would face a special kind of treatment. From the Black Panthers and their anti-capitalist, self-defensive ideology, to Dr. Martin Luther King's non-violent, economically equal pacifism, Black political agitation of any kind would be targeted, neutralized and eliminated. Basketball and its players, with a large platform in Black culture, would not receive immunity. Elite athletes, like Paul Robeson, Muhammad Ali, John Carlos and Tommie Smith would have their athletic careers taken away in their respective primes. The path forward for Black politics would be littered with landmines, traps and sniper fire. The social opportunities for the Black basketball player would expand and widen, promising a future of social currency, privilege, and wealth…as long as you were willing to "shut up and dribble". Left behind are large Black communities, over-policed, underemployed, and economically divested as evacuation zones. Low-income Black communities only became useful to the greater society as fertile gardens for hungry athletes, "cool culture" and predatory Black capitalism and non-profit interference.

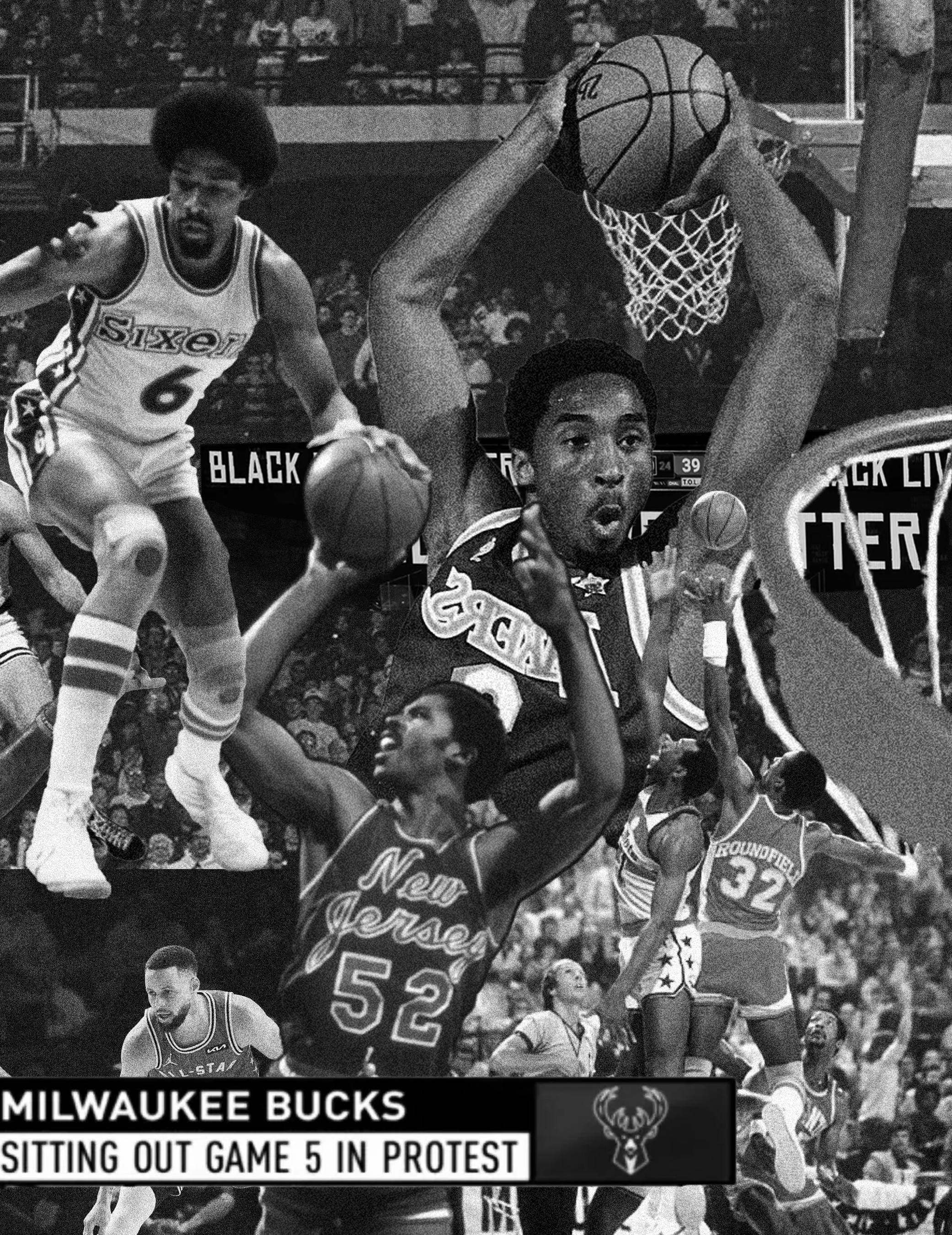

Within A Friendly Game of Basketball, a solo exhibition at Lawndale Art Center, I conclude several years of research and art engagement surrounding the racial and political material within the sport of basketball. Comprising installation, painting, drawing, photography, collage, soundscape and performance, viewers are welcomed into a multi-sensory environment mirroring elements of pre, post and in-game play. By taking the game and examining its historical archives and advertisements, identifying both its historical and contemporary anti-Black phenomena, and reintroducing the isolation, punishment and systemic oppression of radical elements, I am thinking critically about where the sport currently exists, brainstorming new applications for the sport within the community, and imagining how the sport can do more to serve the community that loves it so much.

-Tay Butler, Multi-disciplinary Artist

I’ll Die Happy Knowing I Left It All on the Court.

By Zora J. Murff“All you want is Nikes, but the real ones

Just like you, just like me...”

—Frank OceanOne of my earliest memories involves basketball. My Momma asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, and I responded, “A basketball player.” She wrinkled up her face and laughed slightly, “You’re too sensitive for that.” Looking back, it’s hard to distinguish nature versus nurture. I’m not into sports because competition has always turned me off. Is that an inherent response or a self-fulfilling prophecy?

Even though I never really had hoop dreams, basketball has a significant presence in my life. It exists innocuously: one of the few surviving pictures from my childhood is of Momma, my brother Andre, and I playing in our bedroom. A Michael Jordan poster hangs on the wall above us. Profoundly, the sport has shared adjacency to essential moments in the development of my masculinity. Dad tugged the tongue of my fresh-out-the-box Nike Air Flight Huaraches (released in 1992). He tied the laces until they fit just so. During our square-off, I tripped over my feet and onto my knees; my skin and eyes turned liquid. Dad scoops me into his arms, and I tell him I want mommy. He pulls his face back from mine and says, “You a sissy, huh?”

Do not show your pain. Do not externalize your fear.

On long summer days, Roxy and I would meet at the court behind school to play one-on-one. I walked through the heat carrying my Nike Air Garnett IIIs (released in 1999). Our awkward bodies would dance against one another across cracked asphalt, playing until that delightful sting of exhaustion filled our lungs.

continued on page 7 5

WHO SAID MAN WAS NOT MEANT TO FEEL.

I’LL DIE HAPPPY Knowing I Left It All on the Court.

continued from page 5

We never kept score. Sometimes, we’d sit under the hoop to hold hands and steal kisses. It wasn’t a romantic love, but that curious exploration of the concept with someone safe. At the beginning of the school year, I asked her to go out with me. When the guys caught wind, they teased me mercilessly because she was a “dusty.” One of them said I had to pick a side. Roxy and I met at the courts because we came from the same place: lonely latch-key kids looking for a connection to pass the time. I can’t forget the devastation in her eyes when I said I didn’t pick her.

It’s supposed to be bros before hoes.

I was standing near the free-throw line wearing my Nike Shox BB4 OGs (released in 2000). I watched, mesmerized, as Antonio took off, weaving the ball singlehandedly and in a serpentine fashion. He effortlessly glides and rolls the ball off the tip of his fingers into the hoop. Hydrating from a shared bottle of Gatorade, I mention how graceful he is. “Nigga you gay? That’s some faggot shit.” I was confused and looked at Andre, who casually shrugged and kept sipping. The rest of the guys break out into laughter. I giggle a bit because I don’t know what else to do. I feel shameful for the rest of the game and keep running Antonio’s words through my mind; I jam my finger catching a hard chest pass I wasn’t prepared for. As we walk home, limping in the blue light because of our heavy, over-exerted legs, I ask Andre what those words mean. I don’t get the joke. He tries his best to explain, but I still don’t understand. He tells me to gently pull on my finger to alleviate the pain.

Pause. Exchange of affection isn’t welcome between us.

It’s the day before my first solo exhibition in New York City. I’m thankful, and I call Momma to tell her I’m appreciative that she allowed l me to be my sensitive self. My sensitivity is where my creative drive lives. My wife, Rana, and I stop at Kith to kill some time. She sees them first: the Nike LeBron 18 Low in Mimi Plange Daughters Floral (released in 2018). The cashier asks me if I ball as he slips the box into the bag.

Not really, but in a way...

Murff – I’ll Die Happy Knowing I Left It All on the Court.

A FRIENDLY GAME OF BASKETBALL

EAST ALL STARS

TAY BUTLER

multi-disciplinary artist & EDUCATOR

Tay Butler is a multi-disciplinary visual artist based in Houston, TX. He received his BFA in Photography and Digital Media from the University of Houston and completed his Photography MFA at the University of Arkansas. After retiring from the US Army and abandoning a middle-class engineering career to search for purpose, Tay reignited a rich appreciation for Black history and a deep obsession with the Black archive. Through collage, photography, drawing, video, sound, performance and large-scale installation, Tay utilizes past histories and imagery to create new understandings of the present while imagining a brighter future.

ZORA J MURFF WRITER, ARTIST & EDUCATOR

Zora J Murff is an artist and educator living in Rhode Island. Murff’s work is dedicated to understanding the complexities of racialization. He is Black; therefore he is.

1980 . . . Milwaukee, Wisconsin

1980 . . . Milwaukee, Wisconsin

ABOUT THE ARTIST STUDIO PROGRAM

HEAD COACH - Tay Butler

Assistant Coach - Jeremy Johnson

President - Anna Walker

Vice President - Emily Fens

Director of Creativity - Tamirah Collins

Strategy Manager - MaeLea Williams

Operations Manager - Ashley Everette

Senior Consultant - Ayanna Jolivet McCloud

Senior Consultant - Sol Diaz

Consultant - Ian Gerson

Established in 2006, the Lawndale Artist Studio Program offers residencies to Texas-based artists who are developing a practice in the visual and performing arts. Lawndale awards residents with access to a welcoming and vibrant community of working artists, curators, critics, and patrons of contemporary art. Throughout the nine-month residency, the artists work closely with each other and Lawndale staff on the development and production of new work that will be exhibited in the spring. Lawndale is pleased to announce Tay Butler as one of our 2023/2024 Artist Studio Program participants. Major support for the Artist Studio Program is provided by Kathrine G. McGovern/The John P. McGovern Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts.

INDEX

Works listed in appearence of catalogue:

Hyperinvisibility 2, 2023

Photomontage inkjet print on matte canvas

Image courtesy of the artist

Magicians 2, 2024

Analog collage, acrylic, watercolor, watercolor paper on canvas

Image courtesy of the artist

Larry, 2024

Oil pigment on watercolor paper, found basketball floor wood

Image courtesy of the artist

George, 2024

Oil pigment on watercolor paper, found basketball floor wood

Image courtesy of the artist

Catalogue designed by Tamirah Collins

Supporters

Lawndale Art & Performance Center receives generous support from The Brown Foundation, Inc.; the Garden Club of Houston; Elizabeth Firestone Graham Foundation; The Joan Hohlt and Roger Wich Foundation; The John M. O’Quinn Foundation; The John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation; Houston Endowment; Humanities Texas and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) as part of the federal ARP Act; Kathrine G. McGovern/The John P. McGovern Foundation; The National Endowment for the Arts; The Alice Kleberg Reynolds Foundation; The Rose Family Foundation; the Scurlock Foundation; the Texas Commission on the Arts; the Vivian L. Smith Foundation; and The Wortham Foundation, Inc. Additional support provided by Lindsey Schechter/Houston Dairymaids, Saint Arnold Brewing Company, and Topo Chico.

Funding for Lawndale’s exhibitions is provided by presenting sponsors John Bradshaw, Sara and Bill Morgan, and Scott Sparvero; with additional support from sponsors Mara and Erick Calderon, Jereann Chaney, Alexa Clements, Piper and Adam Faust, Mary Catherine and Bailey Jones, Emily and Ryan LeVasseur, Meghan Miller and Jeff Marin, Adrienne Moeller, Winnie and Nic Phillips, Teresa Porter, Aaron Reimer, Stephanie Roman, Nicole and Joey Romano, and Jessica and Blake Seff; and generous gifts from the Friends of Lawndale.

Forward all inquiries on available artworks, studio visits and artist opportunities to afriendlygameofbasketball@gmail.com