ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Lo que me queda de tu amor (What’s Left of Your Love for Me) considers how artists from distinct backgrounds carry and pass on personal, familial, cultural, and communal histories from one generation to another. Mainstream American culture tradition ally values and presents these stories di erently from the community members themselves. Curated by Francis Almendárez and Mary Montenegro, this exhibition highlights how artists use, contest, and rework traditional notions of an archive.

Through movement, text, sound, performance and improvisation, these artists conjure intergenerational and cultural histories. In doing so, they reflect how their respective cultures and histories have been maintained and their communities have thrived, despite the odds against them. Collectively, these works question the accessibility of archives, since those who have historically shared them are rarely from the communities that produced them.

The title of this exhibition is inspired by Selena’s Fotos y Recuerdos (Pictures and Memories), with lyrics that consider memory, loss, and love. While on view, this exhibition will evolve, with artists activating, modifying, and responding to their work. Ultimately, Lo que me queda de tu amor reconsiders its own format and function as an exhibition to challenge who and what archives tradi tionally serve. A written response to the exhibit will be given by Dr. Stalina Villarreal as both object and performance.

FRANCIS ALMENDÁREZ

is an artist, filmmaker, and educator from Los Angeles, CA. His work takes on many di erent forms including collaborations, performances, screenings, workshops, and exhibitions that have been presented in museum, university, arts nonprofit, artist-run, virtual, and DIY spaces both nationally and internationally. Through the merging of history, autoethnography, and cultural production, his works o er ways to navigate and reconcile intergenerational trauma and reclaim diasporic identities. Writing on his work has been featured in Moving Image Art London, D Magazine, and The Invisible Archive among many other publications. He has also contributed images, interviews, and texts to publications including Burnaway Magazine, Strange Fire Collective, and La Horchata Zine. Almendárez received his MFA in Fine Art (with Distinction) from Goldsmiths, University of London, and his BFA in Sculpture/New Genres from Otis College of Art and Design.

MARY MONTENEGRO

is an art historian and curator whose expertise is in Philippine post-colonial history. Born in the Philippines, raised in Qatar, and now residing in Houston, TX, she explores di erent ways in which Philippine history is told, fostered, and collected through her fellow Filipino migrant workers. She is a member of the Filipinx Artists of Houston, where she continues to learn about shifting cultural identity formations and document the many untold histories of her people through shared diasporic experi ences. She earned her Bachelor’s degree in Interior Design at the De La Salle-College of St. Benilde in Manila, Philippines in 2017. Here, she conducted research on Filipino residential spaces and how Filipino diaspora and migration culture has influ enced placemaking. In 2019, she earned her MA in Art History at Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD). Specializing in post-colonial and feminist studies. Montenegro is the recipient of SCAD Art History Department’s Outstanding Thesis Award for her formative graduate research, “Recontextualizing the Twentieth Century Photographs of Manila Carnival Queens,” where she identified the first Filipina beauty queens from 1908–1930s and their embodiment of precolonial matriarchal power through the continued activism observed in their portrait photographs.

STALINA EMMANUELLE VILLARREAL

lives as a rhyming-slogan creative activist. She is a Generation 1.5 poet (mexicanx and Xicanx), an essayist, a translator, a sonic-improv collaborator, and an assistant professor of Creative Writing. Her debut hybrid collection Watcha is forthcoming from Deep Vellum Publishing. Her poetry can be found in the Rio Grande Review, Texas Review, Spoon River Poetry Review, The Acentos Review, Defunkt Magazine, and elsewhere. She has published translations of poetry, including Enigmas by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Señal: a project of Libros Antena Books, BOMB, and Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015), Photograms of My Conceptual Heart, Absolutely Blind by Minerva Reynosa (Cardboard House Press, 2016), Kilimanjaro by Maricela Guerrero (Cardboard House Press, 2018), and Postcards in Braille by Sergio Pérez Torres (Nueva York Poetry Press, 2021). She is the recipient of the Inprint Donald Barthelme Prize in Poetry.

This project is made possible with the support from The Idea Fund. The Idea Fund is a re-granting program administered by DiverseWorks, Aurora Picture Show, and Project Row Houses and funded by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

“... they reflect how their respective cultures and histories have been maintained and their communities have thrived, despite the odds against them.”

FEATURED ARTISTS

Anthony Almendárez

Emily Areta

JB Baladad

Julia Barbosa Landois

Liyen Chong

Sonia Flores

Bennie Flores Ansell

Xavier Gilmore

Jessica Carolina González

Brandon Tho Harris

Matt Manalo

Gabriel Martinez

Stephanie Concepcion Ramirez

Jamie Robertson

Andre Samano

Andrea “Vocab” Sanderson

Sindhu Thirumalaisamy

Erick Zambrano

A Houston Homecoming of Art

After the exhibition Lo que me queda de tu amor (What’s left of your love for me), curated by Francis Almendárez and Mary Montenegro

3

As I enter, inkjet transparency film flutters and lands propped against the wall

like flying insect taxidermy that could be handheld but isn’t. Bennie Flores Ansell’s mostly magenta or black mini-sculptures speak on migration, sanctuaries, and the process of gathering—or consumerism. The moment freezes flight capturing both figurative yet abstract beings mounted on butterfly collection pins.

The titles Morpho Manolo Mary Janes and Manolo Blahnik Collection for Nieman

Marcus suggest that fancy high heels can shrink and flatten from horizontal to vertical motion.

2

Flora my abuelito would call “yerba,” us unknowing what kind of green plants grow, surrounding a young woman in a green field, her black tank top indicates summer heat. Stephanie Concepcion

Ramirez filmed Por Amor, this rite of handwashing motion—her hands, waterless in the air. Did you know,

friction does not kill germs? The chlorophyll creates oxygen for her— breath—her palms and fingers tickle the air.

A vision of a hand but caption of the body, and a question of “me?” Sindhu Thirumalaisamy’s black-and-white

film oon interrogates el cuerpo, ¿cómo estás? With stainless steel cutlery and a sense of loss —conexión interrupted— yogurt rice, rasam rice licked, slurped from fingers, implying an intimacy of eating with the hands, a culture clash of etiquette against rules, norms,

and restlessness, in favor of being tactile, texture, freedom, joy to nourish rather than to limit and poison.

4

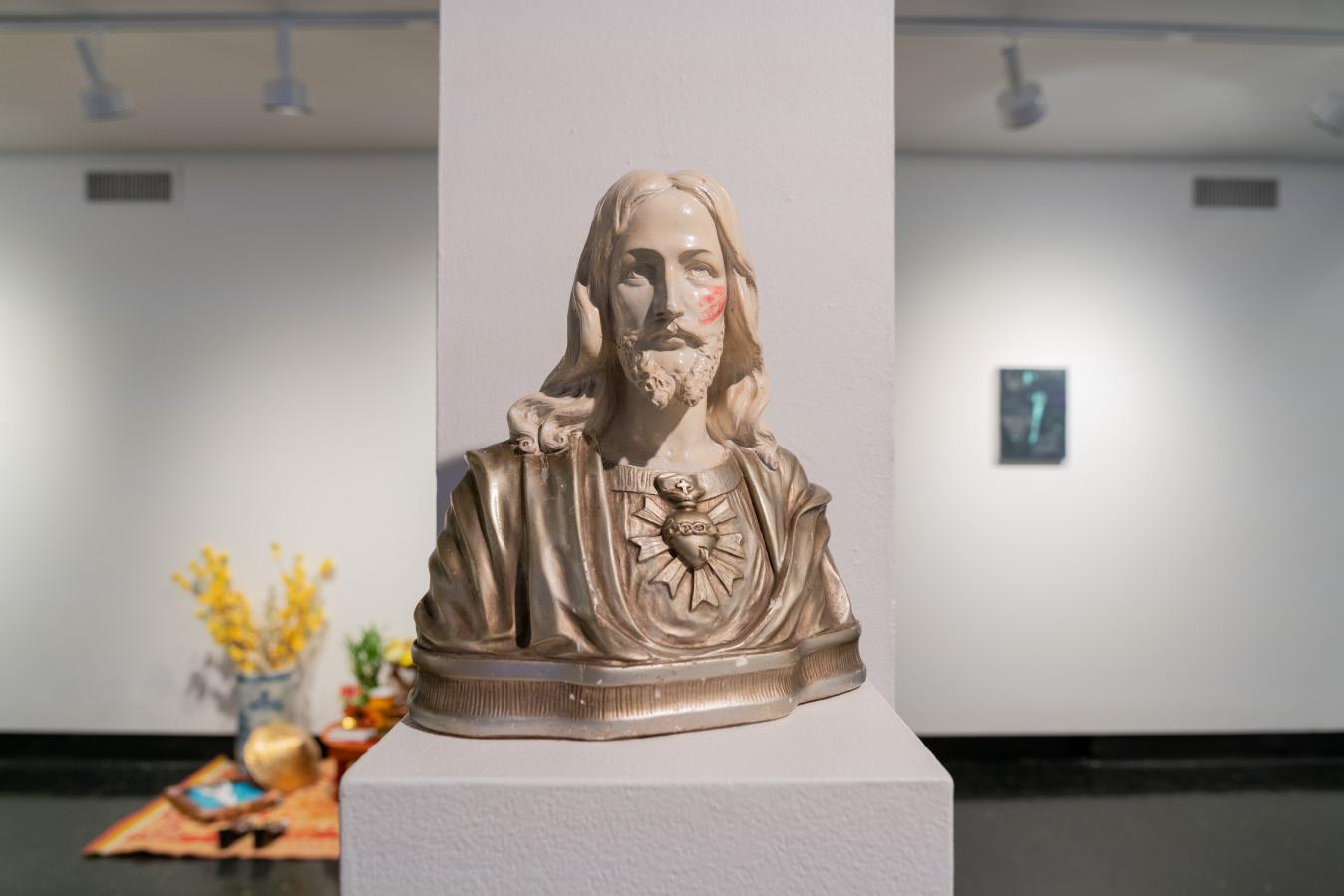

With lipstick on the cheek, a Jesus bust faces Julia Barbosa Landois as she sings about fleeing a divine spouse who rapes.

Star-Crossed II aborts almost middle-aged fetuses. The agency of a woman not to learn how to make tortillas as a form of feminism.

The womb becomes a powerhouse que comprende that independence y amor coexist. Sometimes

I only hear—whistling— a veces—the lyrics scroll up— I listen—to the contralto’s robust voice.

7

Jamie Robertson’s feet and hips dance to “Coupe Cumbia.” A bouncing, and swaying of the hips in a shiny red skirt, the swift movement of nimble feet on one, a veces dos, sometimes three screens, plus occasional hands. Painted nails. The film Flat Red projects scarlet monochromatic motions of emotion and selfconcept of the body, I see a feminist femme body.

6 Annotations marking artists’ activism as a collective for social change. I read quotes of memory, community, the resistance of a colonized body. A photo of clutter, what’s left of a grandfather’s possessions after his passing, to prompt a granddaughter’s dreams.

An installation of books, words, photos, Liyen Chong’s Note and Objects from a Personal Archive integrates family photos, more recent photos she took, intergenerational migration narrated, explored, and thoughts transcribed on paper. I view a photo of her schooling in Malaysia and her curiosity: a teacher.

The macramé by Sonia Flores in Nebula I knots cerulean, pink, purple, teal, gray, vermillion, and baby blue strings with a twist of fuchsia, peach, navy blue, pastel purple, and hot pink tulle, meticulous yet abstract, the repetition of hitching knots, textile hanging from a long, curved stick, visual stimuli, I want to touch the draping fibers.

8

Gabriel Martinez finds fabric on the street and stitches an abstract composition on canvas. He challenges the economics of canvas art. The black and gray fabric looks like it wrinkled in the fading sun but is stretched flat, stitched with a steady drummer’s hand. Dark violet fabric contrasts with the fluorescent cools of a floral pattern. Without my touch, mysterious texture.

9

In Memory Of ancestors, Brandon Tho Harris commemorates his dead loved ones with o erings like co ee, flower lamps, fruit, incense, and money on a wooden altar table. Flowers and plants. Shoes and suits made of joss paper. Most objects lie or stand on a rug, but one suit protrudes from a wall. The process of looking forward and also down invites me to lower myself to the floor and pray.

In a poem on the wall, Anthony Almendárez narrates In lieu of green grass, the questioning of attitudes toward labor.

I summarize: his various jobs como un obrador get stereotyped as “unskilled,” homeless, yet his coworkers encourage him to move on because of his degrees, despite the arts job prospects being bleak. He critiques the entitlement that comes with degrees.

His installation includes a sheet of three floral fabrics sewn together, attached to the wall and slightly on the floor;

por el piso, a multicolored rain stick, and a tiny container with seeds, a shelf with jars of mostly seeds, and a dried pepper, a tradition: growth, spice, nutrition, maturity.

11

The film documenting Ambulante, a performance by Erick Zambrano indoors at a gallery in which he encircles a paper bag; he tapes what looks like a receipt to his shirt, and takes bananas out to give to the audience.

He yells, “Guineo,” a scream of rite. He eats a banana while screaming, though the food mu es him some.

Banana strings hang from his lips. He walks outside to another paper bag, which has pesticide. He pours

it into a pump. He undresses, starting with his shoes, socks, shirt, shorts. Pero sí trae su ropa

interior. He sprays himself with pesticide while still chewing the banana and yelling I find entrancing. Finally, he gets dressed.

12

A repurposed found hand drum I want to play hangs from a wall. Matt Manalo’s Exotification of a Marked Skin narrates in concentric circles of words on paper how language is misunderstood, with wax and gel medium covering the words in semi-opaque layers; desire from colonial powers to overpower individuals mishandles the drum, and the illegibility of the words become a conversation in itself about how communication can be a trauma, but art can be healing.

13

A large inkjet print documents a performance by Jessica Carolina González—all that is left is a hanging machete and black splatter on the floor. The recording of a machete sharpening. What happened? The notes say, amantes se amenazan como armas

y sus sonidos pueden tener filo and the dead can rest in peace. The handwriting obstructs the print.

14

After viewing the artists’ work on the second floor of Lawndale, I sit on the bench and close my eyes,

hearing the alternating singing, whistling, and instrumental music, the repetitive “Guineo,” the blade sharpening. Together

the sounds combine to what might be cacophony for some, but harmonious to me. I don’t want to walk out, ever.

Lawndale is a multidisciplinary contemporary art center that engages Houston communities with exhibitions and programs that explore the aesthetic, critical, and social issues of our time.

Supporters

Lawndale’s exhibitions and programs are produced with generous support from The Anchorage Foundation of Texas; The Brown Foundation, Inc.; David R. Graham; The Joan Hohlt and Roger Wich Foundation; The John M. O’Quinn Foundation; The John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation; Houston Endowment; Humanities Texas and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) as part of the federal ARP Act; Kathrine G. McGovern/The John P. McGovern Foundation; The National Endowment for the Arts; The Alice Kleberg Reynolds Foundation; The Rose Family Foundation; the Texas Commission on the Arts; The City of Houston through Houston Arts Alliance; and The Wortham Foundation, Inc. Additional support provided by Lindsey Schechter/Houston Dairymaids, Saint Arnold Brewing Company, and Topo Chico.