TRAFFICKING IN CAMBODIA

TraffickinginCambodia: AGlanceat(Mis)RepresentationsofSexWorkers

LAURA KUN

TraffickinginCambodia: AGlanceat(Mis)RepresentationsofSexWorkers

LAURA KUN

Dear Readers,

Firstly, I would like to respectfully acknowledge that this zine was created on the traditional, ancestral, stolen, and current lands of the Monacan Tribe My ability to create this zine here in Charlottesville and at the University of Virginia (UVA) is predicated on the dispossession and displacement of the Monacan Tribe. As an Asian American discussing colonial and gender politics within this zine, I recognize that the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) movement for social justice may not align with the struggles for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination. Furthermore, while a land acknowledgement is not enough, I believe it is an important decolonial practice that promotes Indigenous visibility and reminds us that we are on unceded Indigenous land I urge you to also reflect on the histories of the lands you occupy.

This zine serves as my final project for WGS 4500: Identity Politics, taught by Professor Denise Walsh With this zine, I intend to answer the following research questions: How do foreign actors of humanitarian intervention (i.e., anti-trafficking non-governmental organizations (NGOs)) reinscribe the marginalized statuses of sex workers in Cambodia through their media representation? How do anti-trafficking NGOs harm the very populations they claim to protect? How do Cambodian sex workers repudiate and resist this portrayal? While these are a few questions I attempt to answer throughout my zine, my collected research and subsequent analysis may beget more questions than answers.

Drawing from Michel Foucault and Didier Fassin, I interpret NGOs’ (mis)representation of Cambodian sex workers as a biopolitical technology used to control and discipline misfit populations. By misrepresenting sex workers, NGOs further deepen their marginalization. In this media ethnography, I specifically examine the depictions of Cambodian sex workers and their parents in the documentary, “Nefarious: Merchant of Souls,” and within the antitrafficking NGO, Agape International Missions. I trace how individuals in “Nefarious” cast moral shame on the parents of trafficked children and construct sex workers as devoid of agency. I contrast this perception of Cambodian sex workers with those voiced by the sex workers themselves in the documentary, “(Sex Workers Cry) Rights not Rescue in Cambodia.” Here, we find that sex work is fulfilling, satisfying, and consciously chosen by many women.

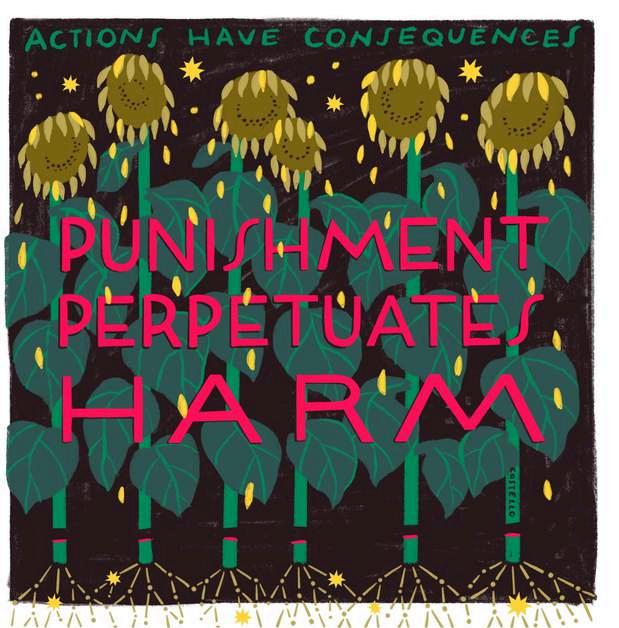

In “Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison,” Michel Foucault offers an in-depth examination of punishment, genealogically tracing its origins as a public spectacle to its contemporary form in imprisonment. For Foucault, punishment is a form of power itself, in which it administers and disciplines the bodies of offenders. However, power is not simply the direct repression of individuals, but also a discreet matter that circulates within social and political relations to enforce norms in a disciplinary manner (Foucault 28). As the power to make live and let die, biopower describes the power to administer and shape the conditions of life at the level of the population and individual body.

Foucault notes that power is also intimately connected to the body and knowledge (24). These three interconnected concepts power, body, and knowledge ground Foucault’s understanding of punishment, but can more broadly describe the foundation for many modern systems of domination. Throughout this zine, I aim to critique anti-trafficking NGOs as a form of domination, because they leave many Cambodian sex workers susceptible to the scrutiny and violence of police officers.

I will first elaborate on the three bases of any structure of domination: power, the body, and knowledge. The body is the docile

“object and target of power” (Foucault 24) that may face subjection, normalization, transformation, and improvement into a productive subject. Meanwhile, to successfully exert control over a subject implies an understanding or knowledge of the body (Foucault 26). Knowledge not only constitutes power, but power also produces knowledge Foucault terms this mutually beneficial relationship as “powerknowledge” (27).

With bodies as “the effect and instrument of a political anatomy” (Foucault 30), I find that the disciplinary nature of punishment cannot contain itself within the prison system it haunts the entire society. Punishment constitutes the stable order of society, generates means of sociality, and enacts meaning-making of rational actions. The prison is merely an exemplary instance of a political anatomy that constantly and persistently surveils its subjects through the dispersion of disciplinary norms. Like prisoners, other individuals of such a surveillance state begin to internalize the disciplinary mechanisms of punishment Subjects find themselves under an omnipresent and disciplinary gaze that compromises one’s agency for the alleged benefit of normalization. While he does not explicitly say it, Foucault alludes to this idea of modern society replicating the interior of a prison He analyzes many other societal

institutions (e.g., education, health) that reproduce the logic of domination and discipline implicit within prisons. Notably, while NGOs promote shelters as a possible solution to trafficking, sex workers frequently describe them as “prison-like” (Surtees 197)

In relation to biopower, Foucault argues in “The History of Sexuality” that the state maintains an interest in regulating sex. Foucault believes sexuality remains of focal interest to the state for it “represents the precise point where the disciplinary and the regulatory, the body and the population are articulated” (72). That is, through punishing those who fell outside the norms of acceptable sexual behavior, sexuality became the ideal strategy for disciplining the individual and regulating the population

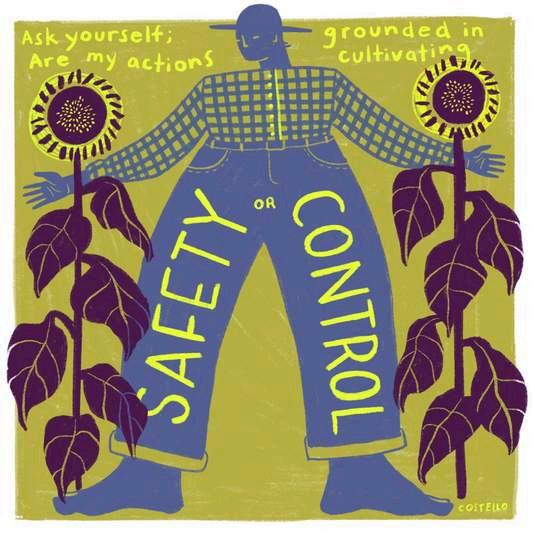

For the state to exercise adequate control over its population, it must then rely on the individual’s internalization of biopower and its sexual norms. One way for NGOs to facilitate this internalization is to usurp knowledge production processes and construct misleading narratives of Cambodian sex workers as one-dimensional victims. The work that NGOs do protecting victims, shaping health policies, intervening during humanitarian “emergencies” assumes the logic of biopower.

With the help of large pools of funding, organizational and management capacities, and intricate networks, NGOs create a direct form of nongovernmental diplomacy, “allowing them to act in parallel to [the] state” (Pandolfi 372) Biopower reduces subjective individuals to “indistinct, displaced, and localized” (Pandolfi 374) bodies that come to be classified and thus controlled under the normative categories determined by humanitarian management, such as “traumatized victims” or “bad parents ”

While definitions of sex trafficking vary, they usually contain three common elements:

1) the recruitment and/or transportation of a human, 2) for work or service, and 3) for the profit of the trafficker.

The United Nations has defined trafficking as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring of people through force, fraud or deception, with the aim of exploiting them for profit” (“HumanTrafficking”).

Such broad definitions can lead to increased policing and surveillance of all individuals involved in trafficking, leaving those who consensually participate in prostitution susceptible to the whims of police violence.

Cambodia has one of the fastest-growing sex industries in the world.

90%ofprostitutesin Cambodiaenterthe industryagainsttheir will.

40% of prostitutes in Cambodia test HIV positive 35% of prostitutes in Cambodia are children under the age of 16.

TheCambodiangovernmentin2008passedthe“Lawon SuppressionofHumanTraffickingandSexualExploitation,”which criminalizesallformsoftrafficking.

Inkeepingwiththe1949 ConventionfortheSuppression oftheTrafficinPersonsandof theExploitationofthe ProstitutionofOthers,this2008 lawholdsthattraffickingcan occurevenwiththeconsentof thetraffickedperson.

Itisbelievedthatthosewho allowthemselvestobe traffickedarenottruly consenting,butrather surrenderingtothe exploitativeconditionsof theirsituation.

“Ramona(Californian)woman fightshumantraffickingin Cambodiawithbakedgoods”

“ExposingtheChildSexTraffickingEpidemicin Cambodia”

“sex traffickingin cambodia”

“Thewomenwhosoldtheir daughtersintosexslavery”

Giventheirpresumedprofessionalismanddirectengagementwithvictims, NGOsholdacertainkindoflegitimacyinbecomingthe“voice”ofthose trafficked.Thevictimstoriestheysharewiththepublicareeasilyacceptedasthe “truth.”

Fromapostcoloniallens,however,Ichallengethisunquestionedrepresentational authorityofNGOs.“Postcolonialism”doesnotsimplydenotetheliteraltime frameaftercolonialism.Rather,itmorebroadlyrefersto“thecontestationof colonialdominationandthelegaciesofcolonialism”(Loomba16).Postcolonial scholarsrecognizethatlegaciesofcolonialismcontinuetoinfluenceandshape currentsocioeconomicconditionsandpoliticalideologies(Loomba).A particularlyinsidiouscomponentofthiscoloniallegacyis“theEurocentricorientedproductionofknowledgeaboutnon-westernpeopleandtheircultures” (Hu).BuildingonEdwardSaid’scompellingargumentin“Permissionto Narrate,”Icontendthattheasymmetricalpowerrelationsbetweenwesternand non-westernsubjectsenabletheformertodominatetheproductionof knowledge.Thesilencedgroupslacktheepistemologicalresourcesandpowerto self-expresstheirexperiencesandviewpoints.Theresultingknowledge producedbythedominantgroupisusuallyonethatmisrepresentsnon-western subjectsandculturesas“singular,monolithic,andinferiortothedominant westernculture”(McEwan).Thus,acentraltaskofpostcolonialscholarship one Iundertakeinthiszine istochallengesuchknowledgeproduction.

In“CantheSubalternSpeak?,”GayatriChakravortySpivakreferstothesilenced, non-Westerngroupasthesubaltern.Notably,theproblemisnotthatthe subalternrefusestospeak,butrathertheirvoicesandtheirmodesof communicationareignoredbythedominantsociety.

Forthoseofuswholiveattheshoreline standingupontheconstantedgesofdecision crucialandalone

forthoseofuswhocannotindulge thepassingdreamsofchoice wholoveindoorwayscomingandgoing inthehoursbetweendawns lookinginwardandoutward atoncebeforeandafter seekinganowthatcanbreed futures

likebreadinourchildren’smouths sotheirdreamswillnotreflect thedeathofours;

Forthoseofus whowereimprintedwithfear likeafaintlineinthecenterofourforeheads learningtobeafraidwithourmother’smilk forbythisweapon thisillusionofsomesafetytobefound theheavy-footedhopedtosilenceus Forallofus

thisinstantandthistriumph Wewerenevermeanttosurvive

Andwhenthesunrisesweareafraid itmightnotremain whenthesunsetsweareafraid itmightnotriseinthemorning whenourstomachsarefullweareafraid ofindigestion whenourstomachsareemptyweareafraid wemaynevereatagain whenwearelovedweareafraid lovewillvanish whenwearealoneweareafraid lovewillneverreturn andwhenwespeakweareafraid ourwordswillnotbeheard norwelcomed butwhenwearesilent wearestillafraid

Soitisbettertospeak remembering wewerenevermeanttosurvive.

Anti-trafficking documentaries are far from powerless forms of entertainment or unbiased depictions of reality, particularly those produced with the assistance of NGOs. Carole Vance argues that anti-trafficking documentaries rely on “the [video medium’s] seeming authenticity of the real” (201) to mask their ideological and political work. Namely, the oversimplified representations of trafficking in antitrafficking documentaries foreclose the possibility of imagining more nuanced and useful policies and understandings. By creating impenetrable regimes of truth and narrow definitions of truth, anti-trafficking documentaries deploy biopolitical technologies that promote a normative understanding of sexuality and other aspects of human life, such as parenting.

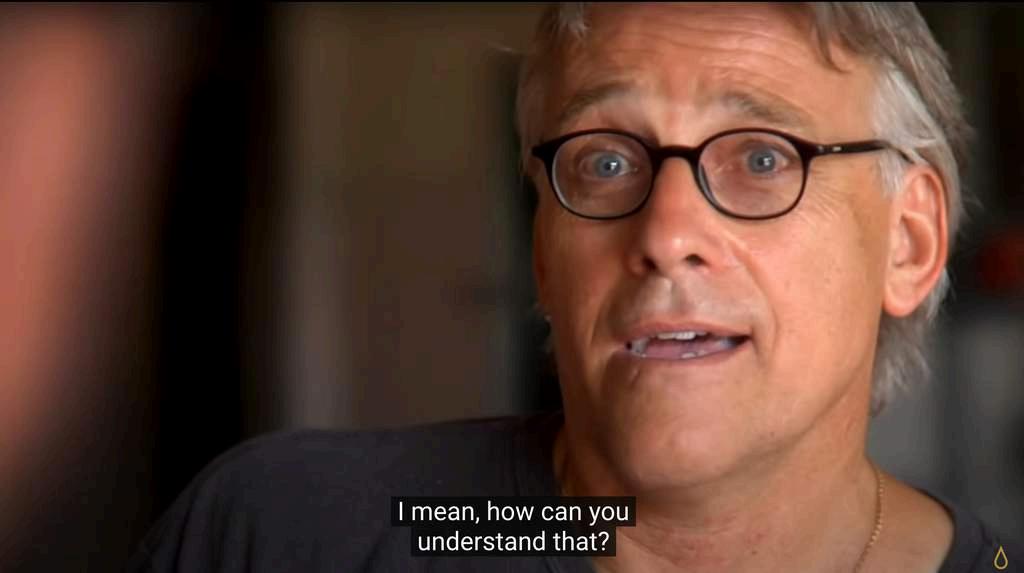

Nefarious: Merchant of Souls is a documentary written, produced and directed by Benjamin Nolot, the CEO and founder of Exodus Cry, an American Christian nonprofit organization dedicated to the abolition of the legal commercial sex industry. Nefarious is interesting to study because of its public accessibility and prominence in transnational conversations about trafficking in Cambodia. Currently, it has amassed 2.7M views on YouTube. Nefarious follows Nolot as he travels to nineteen different countries one being Cambodia and “ exposes the disturbing trends of modern-day slavery.”

“When we drove into the city today, we were coming down the street and we actually saw a pedophile. Older, probably in his 50s, and we were able to track him down, to chase him down, and to warn him not to come back to this city” (39:16).

In Nolot’s interview with Don Brewster, the Director of Agape International Missions (AIM), silences are quite revealing. Brewster recounts an intervention where he attempted to rescue Cambodian prostitutes from a karaoke bar:

“‘We have a place. You can get out of this. We have a place where you can come, and we can make sure you get healthy, and you’ll get good food. You’ll get an education. We can help you to have a brand-new life’”

“There was only one thing we needed to do to be able to take them. They needed their mothers to say it was okay. We called all three moms. All three moms said, ‘No.’ All three mothers said, ‘No, we’re not gonna –they can’t do it. We need the money’” (42:43).

Neither Brewster nor Nolot explicitly blame the mothers, however, it is clear that judgment has been passed upon them. After Brewester’s story, Nolot claims “We could see that poverty had been an underlying factor driving girls into the sex industry, but what we didn’t understand was how a parent could sell their own child into sex slavery” (44:38).

Nolot’s inability, or rather, unwillingness, to understand parents suggests his moral censure of their decision. In other words, Nolot implies that no parent would ever sell their child if they loved her and if they were “good” parents in a normative family unit.

Further, Brewster notes, “across the way there’s six men that sit there every day, smoke cigarettes, gamble, and drink beer all day long. From 10 o’clock in the morning to 10 o’clock at night, that’s all they do. And so how could they afford to do that? Because they all traffic their daughters. They’ll sit there. They could work, but they don’t work. And they traffic their daughters every single day” (45:34). As material considerations fall short of justifying the act of selling one’s daughter, blame is shifted onto parents and their moral depravity.

Instead of speaking to parents themselves, Nolot captures a shaky perhaps even non-consensual video of them lounging around. Though Nolot admits that he “didn’t understand was how a parent could sell their own child,” his next line of action is not to speak to parents but rather he follows this sentence with “So we talked to Helen Sworn” (44:53) a white woman and the founder of the NGO, Chab Dai Coalition. The absence of a parent’s perspective in Nefarious contributes to the continued silencing and ignorance of the “subaltern.”

Like Brewster, Sworn minimizes the role that material poverty plays into trafficking: “So we carried out research [and] saw in some of these communities, it wasn’t actually the poorest families that were selling their daughters. It could be that some of the families that wanted to sell them for more luxury items like mobile phones, televisions, that kind of thing” (44:59). Since it was conducted as “research,” Sworn’s observation carries the authority of being factual truth, compelling us to view parents that sell their daughters as moral wrongdoers, rather than individuals driven by material necessity.

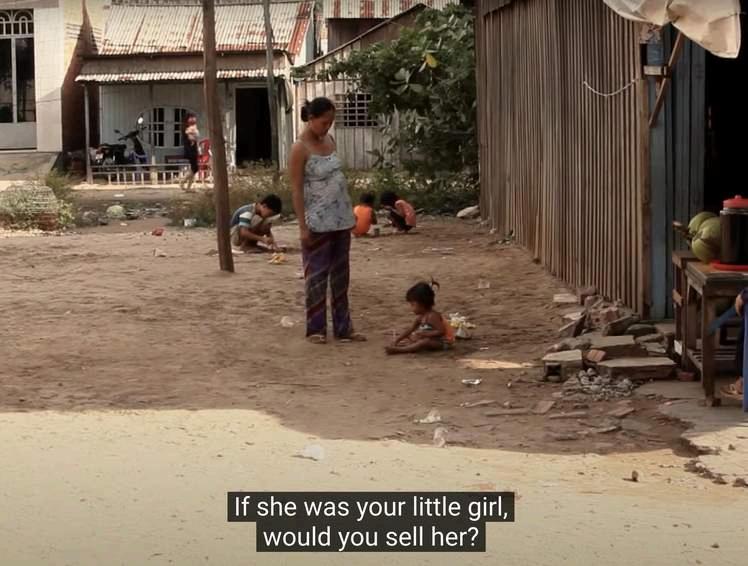

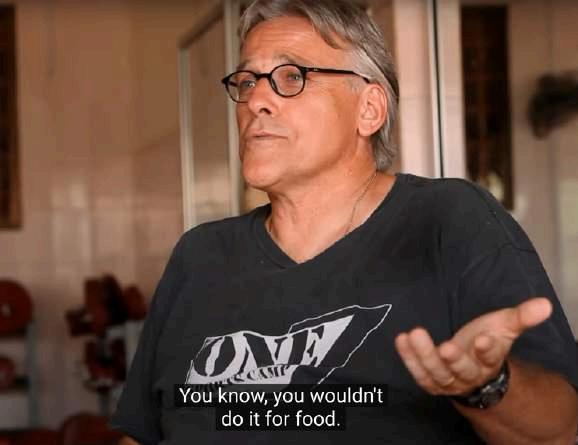

Accompanied by the following frames, Nefarious ends with solemn comments by Brewster:

“LOOK AT THAT LITTLE GIRL OUT THERE. IF SHE WAS YOUR LITTLE GIRL, WOULD YOU SELL HER?

IF YOU DIDN’T HAVE ENOUGH FOOD, WOULD YOU SAY, “OH, I CAN AFFORD TO GET RID OF HER SO I CAN HAVE FOOD?”

YOU KNOW, YOU WOULDN’T DO IT FOR FOOD. YOU WOULDN’T DO IT FOR MEDICINE, RIGHT?

SO I MEAN, THAT WHOLE IDEA THAT POVERTY IS AN ISSUE REALLY, REALLY TAKES A BIG LEAP. HOW COULD THAT REALLY BE AN ISSUE, THAT YOU CHOOSE YOUR DAUGHTER? YOU CHOOSE TO SACRIFICE YOUR DAUGHTER” (49:43).

What seems like an innocuous and heartwarming moment between daughter and father now begs the question: is her father taking her somewhere to sell her?

Infavorofnarrativesthatdepictmorallycorruptparentsastheculpritoftrafficking, Nefarious obfuscatesbroadersocioeconomic considerationsTheminimizationofpovertyhasnegativerepercussionsonsexworkers,whose“problem”isnolongerpoverty,but rather,“badparenting” thusrequiringtheadoptionofpaternalisticpoliciesthatwouldrescuewomen(orshouldIsaygirls?)

(Indeed,throughout Nefarious,sexworkerswereallreferredtoas“girls,”regardlessoftheiractualage)Sincesextraffickingin Cambodiaisconstructedasanissueofbadparenting,theonlysolutionthatcoherentlyfollowsisonethatwillinfantilizesexworkers anddismisstheiragentialcapacitiesInsteadofadvocatingforsolutionsthatwouldattacktherootcauseofsextrafficking(ie, providingresourcestoamelioratepoverty),thisviewfurthermarginalizessexworkers

Inthenameofhumanitarianmorality, Nefarious assumesbiopoliticaltechnologytoshapeourperceptionoftraffickinginCambodia, highlightinghowitthreatensnormsofparentingandsexualitythataresupposedlymorallyuniversal.Theimplicitpigeonholingof Cambodianparentsas“bad”or“immoral”parentscanactivatemechanismsandproceduresofrescue(i.e.,fundraisingandpolicy suggestions),whichexertfurtherdisciplineovernon-normativepopulations.

I will now briefly analyze Brewster’s NGO, Agape International Mission (AIM).

Since 2005, they have taken drastic measures to “ rescue, heal, and empower survivors of trafficking” (Agape International Missions) in Cambodia One such measure is the creation of their own SWAT team, which the Cambodian government authorizes.

AIM SWAT conducts investigations, raids brothels and other indirect sex establishments, and arrests traffickers in collaboration with Cambodian law enforcement. On their website, AIM boasts of “train[ing] local police to be successful in the fight against trafficking” and “involv[ing] police at the earliest opportunity” in “ every case ”

AIM’s mission is “to free hearts, lives, and communities from the evil of sex trafficking in Jesus’ name and in Jesus’ way ” (Agape International Missions)

The pride with which AIM speaks of their SWAT team is deeply unsettling. The endorsement of policing as a solution to trafficking is problematic, because it fails to consider women’s agency and their ability to consensually become sex workers. Since all iterations of commercial sex are criminalized as sex trafficking under Cambodian law, police raids and rescue interventions are often enacted on sex workers who do not want to be rescued.

AIM’s creation of a SWAT team reflects Didier Fassin’s concept of the military-humanitarian nexus, which describes the intertwining and sometimes conflicting relationship between military and humanitarian efforts in crisis situations. That is, humanitarian actions can be influenced or co-opted by military strategies or objectives. As Fassin writes, “Even dressed up in the cloak of humanitarian morality, intervention is always a military action in other words, war” (14). Humanitarian aid provided by NGOs like AIM, then, instigate the very violence they claim to be curbing. The biopower of NGOs draws its strength from militant action, a particularly visceral way to monopolize control and surveil actors of trafficking. Indeed, the existence of a SWAT team for trafficking helps justify the “necessity” to surveil female bodies. Under the banner of protection and rescue, NGOs like AIM harmfully surveil and police female bodies.

“(Sex Workers Cry) Rights Not Rescue in Cambodia” is a collaborative documentary made between filmmaker Paula Stromberg and the Cambodian grassroots sex worker-led organization, Women’s Network for Unity (WNU). In the documentary, sex workers express a desire to hold various stakeholders of the rescue industry NGOs, donors, government officials accountable for the abuse and exploitation that occurs under their “ care. ”

Given that “Rights Not Rescue” is made by/from sex workers and “ sex workers are the experts on their own lives” (5:49), I believe this documentary is a truthful counternarrative one that challenges the misrepresentations of them in dominant discourses. However, the effectiveness of counternarratives is questionable, as mentioned in the documentary: “ no matter how articulate sex workers are as consenting adults who want the right to work, their rights and their wishes are often ignored by the people trying to save them” (13:23). How can we help the subaltern speak and ensure they are actually heard?

The first step is, of course, to listen to their stories and let them sit with us:

In response to the rise of police raids, sex workers express discontent and frustration. Firstly, police do indeed arrest sex workers, which leaves their children hungry at home and forces them to sacrifice schooling. When one woman was arrested and did not have sufficient funds for bail, she solemnly said, “police make me clean toilets and call me filthy names ” (20:48).

ghts Not Rescue” is also concerned with uncovering the ot causes of harmful sex trafficking responses. For one, “root cause ” is “the neoliberal capitalist structures that re harming Cambodia.” Meanwhile, another mentioned hat “society is underpinned by misogyny anxieties about women ’ s access to power including sexual and economic power ” (12:07). I can’t help but recall Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic As Power,” where she ues for the transformative potential of the erotic. When women can reclaim and honor the erotic as a capacious and fulfilling feeling, Lorde argues, we can begin cultivating resilience, joy, and transformative change. Perhaps this is what is missing from anti trafficking courses overshadowed by NGOs a serious reflection of e promise and peril of eroticism and an interrogation of one ’ s own biases against it.

ghts not Rescue” ends with a claim that sex workers are rt of the community. By asserting their belonging to the political, ethical, and religious community of Cambodia, x workers are also demanding to be respected and cared for as equal members of their community. This claim to belonging is also a call for us to recognize their dimensionality, to refute biopower mechanisms that reduce them to the stigmatized label of “victim,” and to, above all, honor their dignity and agency.