Volando Bajito Latinxpresión

Dear Reader,

Dear Reader,

Welcome to this year’s issue of Latinxpresion! We are an art and literary magazine run by the Association of Latin American Students (ALAS) at Washington University in St. Louis. Our mission is to showcase the endless talent within the Latine community and foster unity and pride through our art.

This year, our title is “Volando Bajito: Flight Home.” This expression roughly translates to “flying low”, and evokes the idea of flying close to your destination but never touching down. As university students, we share the experience of leaving home and discovering how to make it anew. Entering adulthood means forging an identity, and learning how we carry and share remnants of our past. Volando Bajito considers how our homes have shaped us through the present moment, and what the future holds as we create space for ourselves.

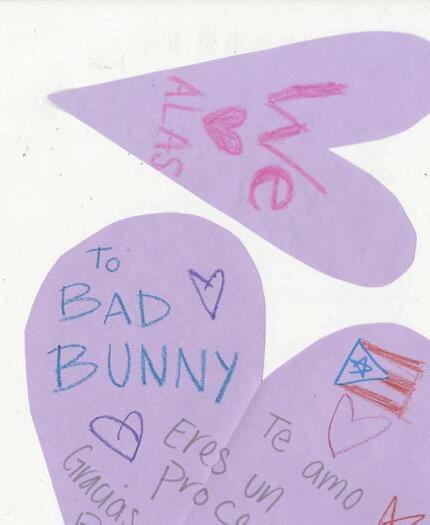

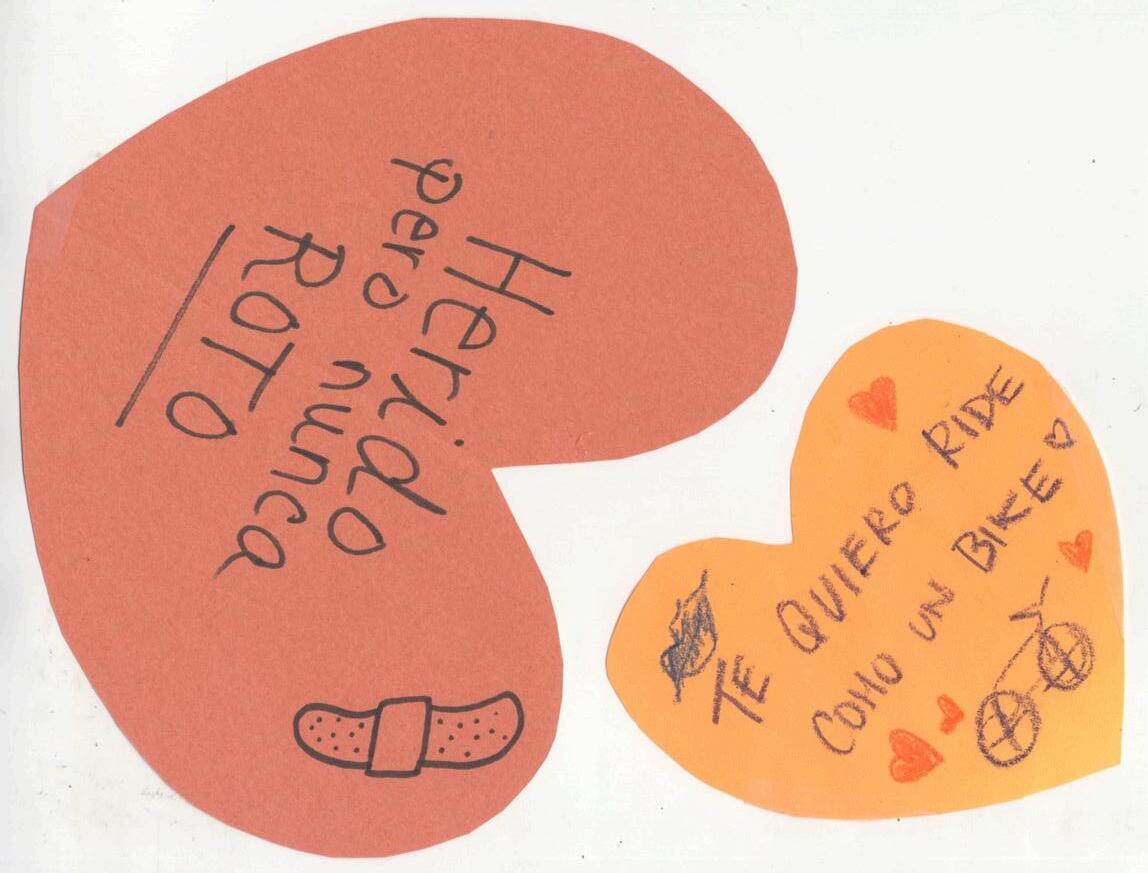

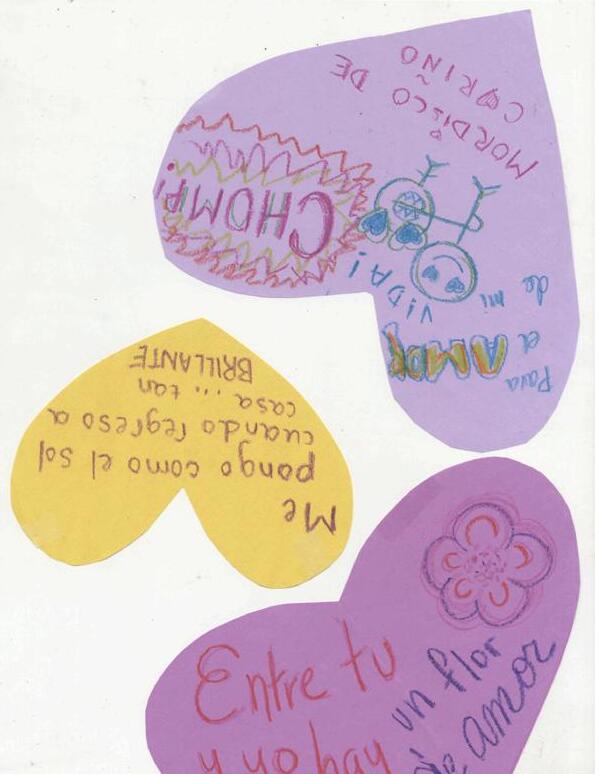

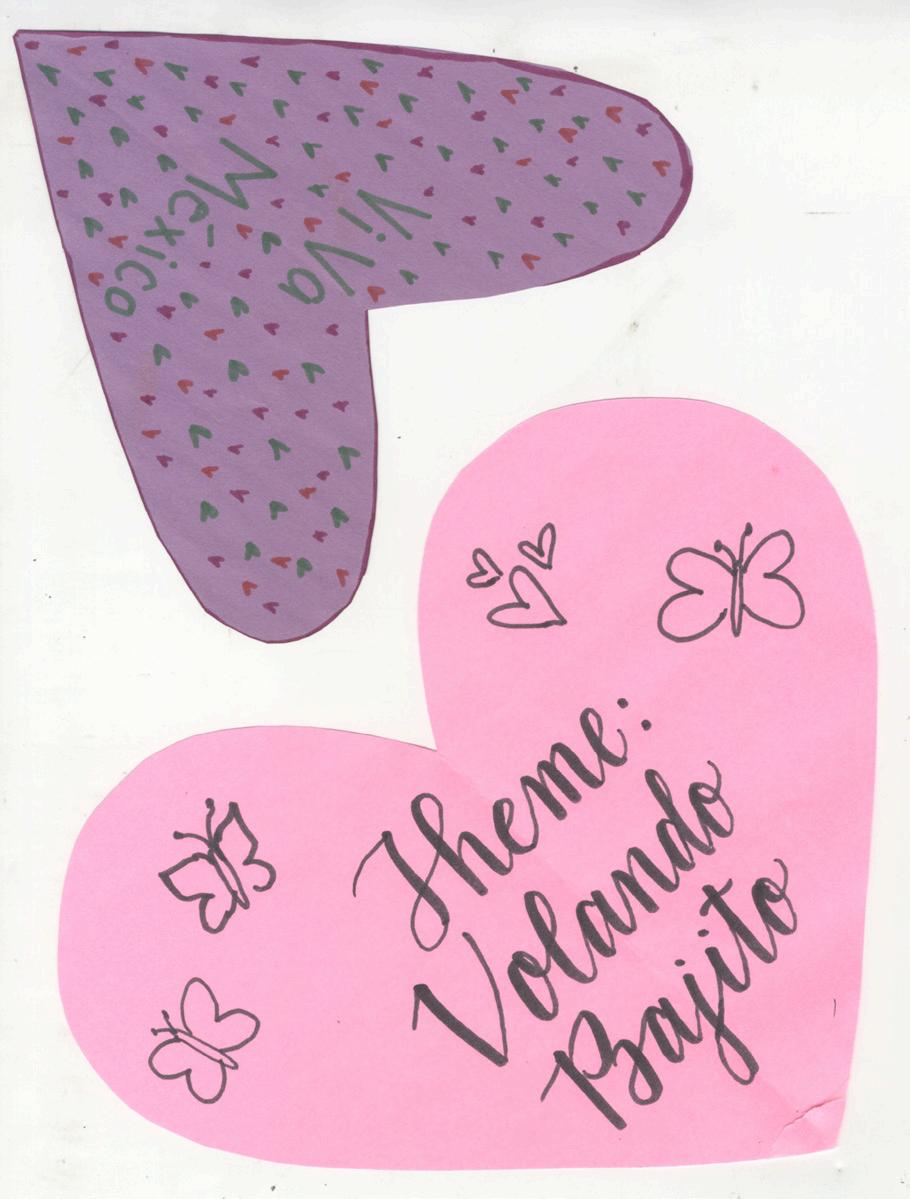

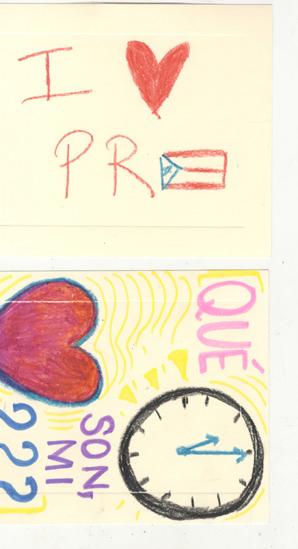

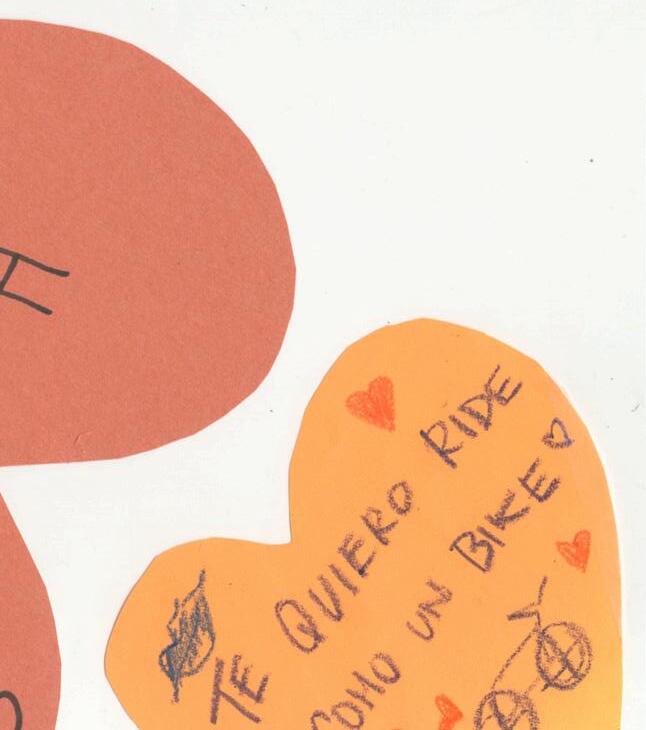

Throughout the year, Latinxpresión hosted multiple events to promote creative expression from the WashU Latine community. Our February event, Love Letters to Latinxpresión, was a huge success. In March, the Melting Pot was an interactive event where students responded to questions like, “What is a tradition from home you like to share?” and “What are you most proud of?” by sharing drawings together. Pieces from both of these events are included in this magazine, and we hope you enjoy them.

We are excited to present wonderful pieces from WashU students from a variety of mediums, including painting, poetry, and digital collage. We are so grateful to everyone who decided to submit to this issue and share slices of their life with us. We are also thankful to our amazing team who has worked arduously throughout the year to make this issue possible.

Sofia Angulo-Lopera & Maya Torres Colom Latinxpresión Directors 2022-2023

Omaha, NE / Mexico City

Maya Torres Colom 2025 Guaynabo, Puerto Rico

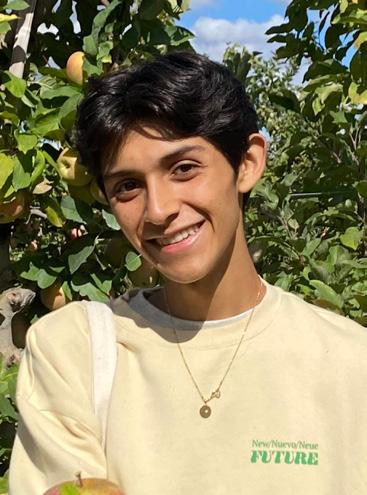

Emillio Parra-Garcia 2026

Sofia Gutierrez 2025 St. Louis, MO

Sofia Angulo Lopera 2024 San Antonio, TX

Kayla Guzman 2025 Houston, TX

Dani Morera Di Nubila 2025 Guaynabo, Puerto Rico

Ariella Uribe 2025 Garfield, NJ

Van Cardenas Garcia 2026 Tucson, AZ

Maya Torres Colom 2025 Guaynabo, Puerto Rico

Emillio Parra-Garcia 2026

Sofia Gutierrez 2025 St. Louis, MO

Sofia Angulo Lopera 2024 San Antonio, TX

Kayla Guzman 2025 Houston, TX

Dani Morera Di Nubila 2025 Guaynabo, Puerto Rico

Ariella Uribe 2025 Garfield, NJ

Van Cardenas Garcia 2026 Tucson, AZ

Marcelle is a student at WashU pursuing a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering. She is very proud to call Ponce, Puerto Rico her home.

Sebasstian Adriano is from Puerto Rico and his family is Mexican. He’s currently studying in the US and will graduate from college in 2025. He enjoys reading, writing, and meditating.

Voy contándome cuentos y voy llegando a un sinfin.

Voy contándome cuentos y voy llegando a un sin fin.

Voy quitándome primero por no quitar el cuarto.

Voy pintándome de negro por no quedarme en blanco.

Voy creando una casa y destruyendo el hogar.

Voy pensando en si merezco volverte a nombrar.

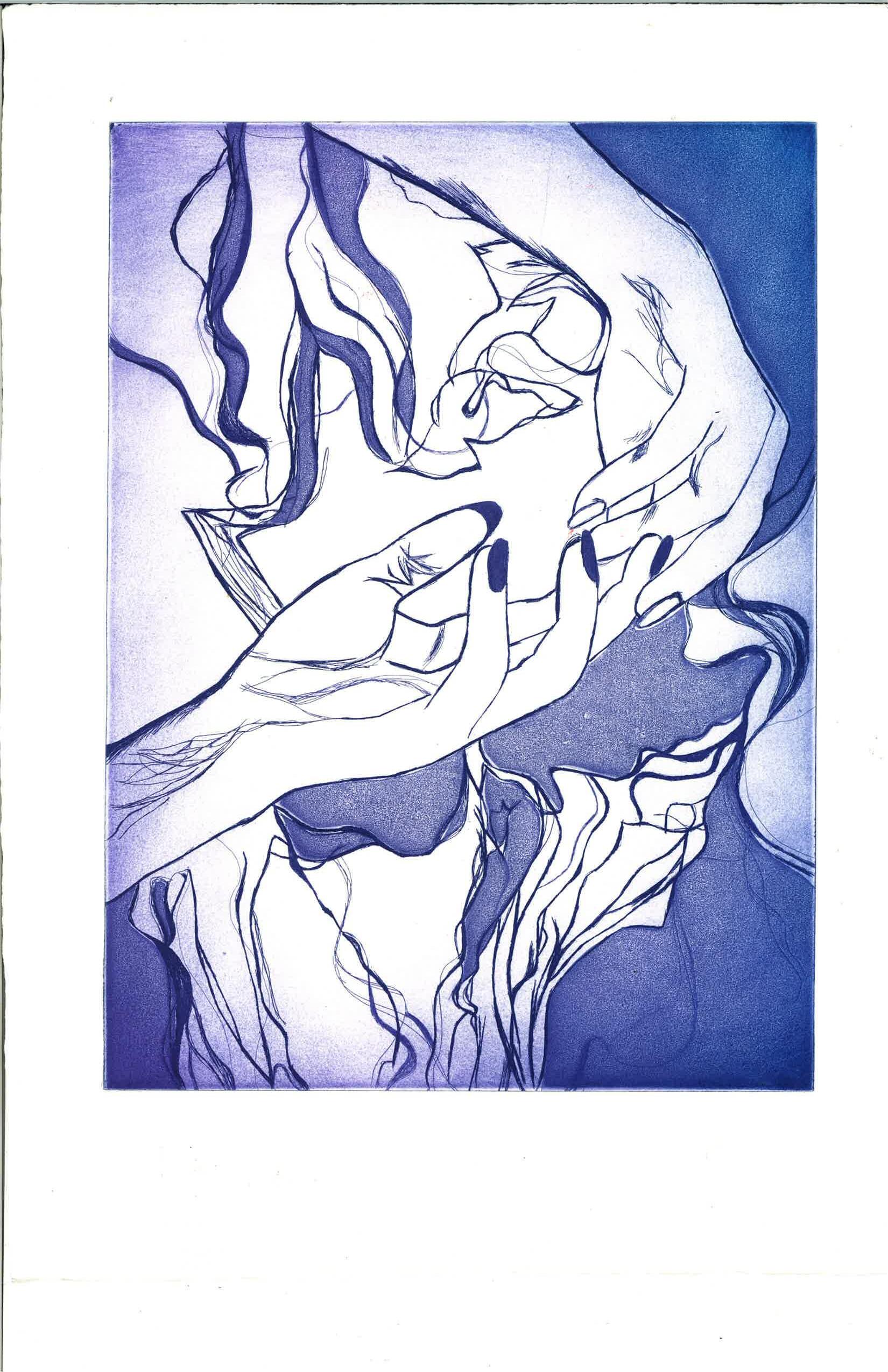

spread by Van Cardenas Garcia

spread by Van Cardenas Garcia

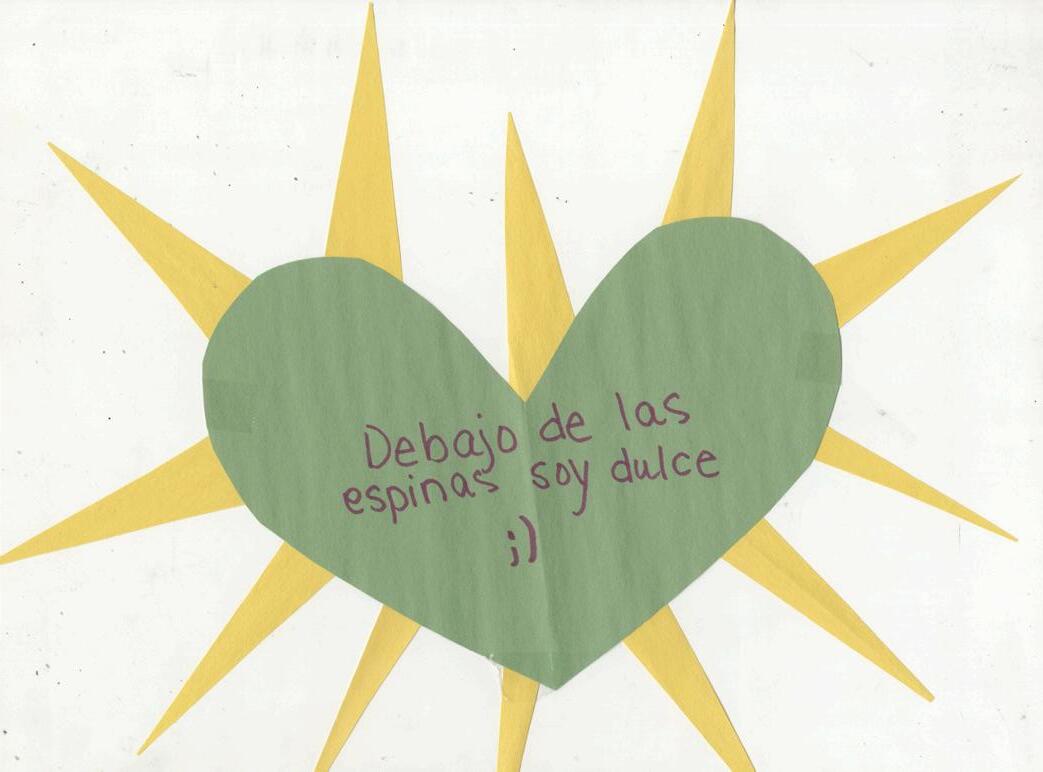

Is there really any better way to start a food-named event than with empanadas? Our Melting Pot event drew a sizable crowd, and it was clear from the beginning that people were eager to get creative. Our lovely directors, Sofia and Maya, read prompts that were meant to stimulate memories from home and culture, and we got the chance to channel our amor for ourselves and home with drawings on construction paper. We then would share with the person next to us and switch papers at the end. Collages of beautiful depictions of culture and home, all encapsulating the essence of “Volando Bajito”, were the end results of this event!

Veronia Lee

Veronia Lee

Veronica is an undergraduate at WashU in the class of 2024 majoring in Cognitive Neuroscience on the pre-medicine track. She is a daughter of Colombian and Brazilian immigrants and her family spent seven years in Singapore, moving to Miami last year. She has written extensively since childhood in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, and her favorite genres are creative non-fiction and poetry. She hopes to call herself a writer professionally someday, but for now enjoys using it as a creative and expressive outlet in her free time.

I want to scream the words to this song in hopes that, if only for one second, the sound will surround me enough to carry my body back to the feeling of frosty pavements in late february.

Snowfall outside the window, calling over the people I don’t know all too well but who show affection through baking and nodding and make me feel safe. Nights on the tousled couch, coming back home day after day to love and snacks and chaos, pink comforter and desolate coffee machine and friends I’ll gladly share my little world with;

Fluorescent showers in a bathroom brimming with joy and anticipation mixed with hip hop and reggaeton; Notes of solidarity and love and the truest definition of family; Misty afternoons, tree-lined walks, a sense of peaceful urgency; Bagels on sunday mornings and lunch at the law school; Schedules running their track in my head, comfort in knowing where I’m going.

So quickly, familiarity spills into newness; routine into readjustment; we adapt before we know we’re adapting and we long for feelings we didn’t digest consciously even when they were on the tip of our tongue. I’m enamored by the changing seasons and coming home, whatever that means and when.

I hope february never leaves the palms of my hands and march never leaves the dimple in my left cheek and april never leaves the crest of my temple.

I hope gray mornings and my inner monologue and my friends’ laughs never leave the base of my throat and that late night rehearsals never leave the soles of my feet. I hope many things. Most of all, I hope nostalgia never ends and that the love I have received and experienced will live on so boldly that I can all but wrap my arms around it and breathe it in whenever its familiar song plays back in my head or in my ears. Oh, I hope so.

Sebasstian Adriano is from Puerto Rico and his family is Mexican. He’s currently studying in the US and will graduate from college in 2025. At age 16, Sebasstian published a poetry book with Ediciones Situm titled: “Cartas en Mano, Dosis de Tinta.”

¡Nosotros somos juventud!

Nos cansamos de ser el futuro.

¡Nosotros somos el presente! Nos cansamos de ser inmaduros.

¡Nosotros tenemos buen diente!

Nos cansamos de ser los impuros.

¡Pecado, peligro, serpiente!

¡Nosotros somos juventud!

Queremos derechos de vuelta.

¡Nosotros somos juventud! Queremos también a la tierra.

¡Nosotros somos juventud! Queremos ondear la bandera.

¡Profanan, bohemios, bohemias! Ésta joven juventud tiene mucho que aportar, fuimos muchos a marchar entre aquella multitud y entre la vicisitud del horrible huracán, fuimos muchos con afán a dar lo necesitado, mas por lo que hemos mostrado ni una décima nos dan.

Carlos Cepeda is a creative whose practice centers around collage-making, architecture, and design arts. They are originally from Venezuela and many of their works revolve around community, immigration, and connection.

Artemisia is a Chicana poet and artist. Her writing has appeared in publications such as Inlandia Literary Journal, Subnivean Magazine, Magma Poetry, and Fifth Wheel Press (from whom she received a 2022 Pushcart Prize Nomination). In 2022, she won the James Merrill Prize for Poetry and the Howard Nemerov Prize in Poetry from Washington University, where she is currently studying Studio Arts and Latin American Studies. She also goes by Arte.

The Mayor, white, balding leaning over a polished wood table to tap on a microphone. ()()

An event from 157 years ago stumbles into the room and begins pushing over chairs.

Two minutes. La Virgen De Muerte. Two Minutes. Thank you Councilor. The noise gets caught

in the air conditioning vents and seat padding (can you still call it a seat if it’s been pushed

on to its side and can’t be sat on? anyway) A veteran and a Hispano, he steps on stage and mutilates himself. He takes a ceremonial knife that he bought on E-Bay and carves out his own heart like believes his Aztec ancestors would do. He is not Aztec and they wouldn’t.

Then he places the still-dripping red bundle of sludge that was his life force on the laminated wood. It is still beating and splurting. Little wet screams. Thank you Councilor.

The piece focuses on the writer’s displacement of ‘home’ as a college student, particularly her journey of adapting, her unstable emotions, and yearning for family. Through anecdotes and afterthoughts, the writer gives insight as to what ‘home’ may be and where it can be found, and ultimately, suggests her own existence itself as the answer. As a first-generation student and queer woman, the writer is interested in exploring identity and relationships, usually familial ones, within her works.

I tend to make a home in what is malleable.

In the lifeless yellow walls of my dorm room that I try to revive with posters and pictures, on the walks to and from campus that are often made alone, drudgingly, silently, save for the sound of human traffic and the music blaring in my ears.

(Sometimes I forget to play music, sometimes I call my mom and her voice is what keeps one foot in front of the other until I reach my dorm room).

I find home in takeout boxes when dining hall food makes me want to cry at the mere sight of it, in the meticulously planned grocery runs with my roommates and bummy laundry days, in the late night laughter of my friends when work has us delirious and ranting is the most accessible kind of therapy.

Sometimes I forget home is supposed to be 330 miles from here. Never for long. It doesn’t take much for my thoughts to wander, for a yearning to build up, aching to escape my body and pleading to go back to the house that witnessed me morph into the young adult I’m supposed to be.

(Sometimes on bad days, on most days, I feel every age before 13 all over again.)

When the fabric softener smells like washed sheets on Saturday mornings and my mom’s embrace, when the coffee I make doesn’t taste the same despite being the same grinds and creamer, when the person in the mirror looks a little too familiar but it’s because I grew up with her. (I cry when I see my mom’s face in the reflection of dark lips and brows I’ve painted on.

I wonder if she cries the same way I do, if she ever sees me in her vanity.)

Maybe home is routine, complacency, the familiar.

Maybe home is in the memories I unknowingly carry with me until they burst through my skin and color everything I see with feelings: scathing and lovely and everything in between, chanting mutely, desperately, ‘remember remember remember.’

Maybe home is wherever my heart desires to be at a given moment. Or maybe what makes home is simply me.

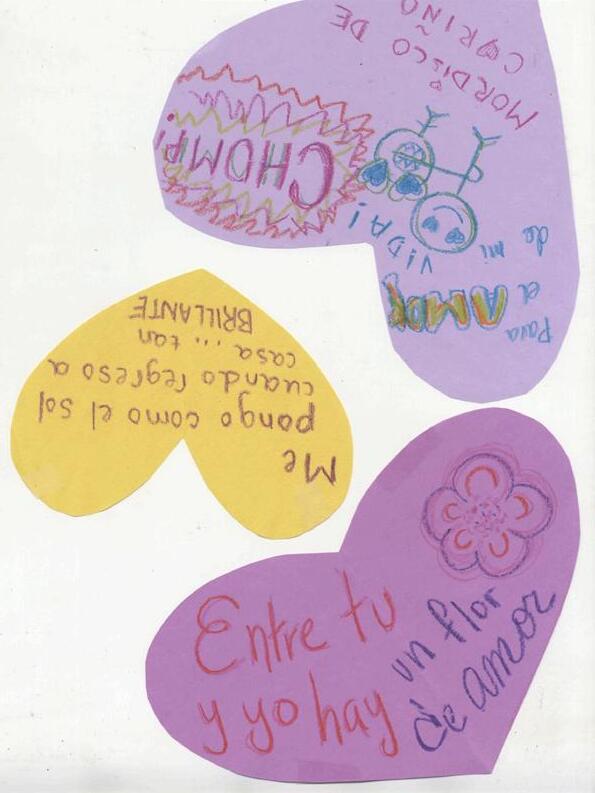

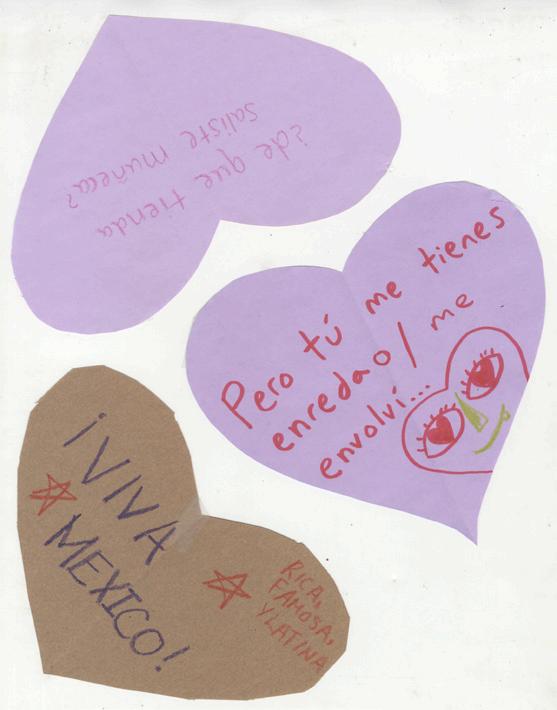

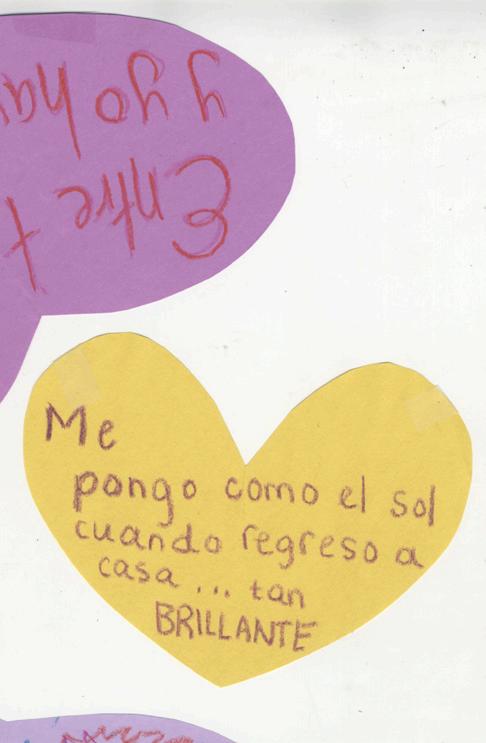

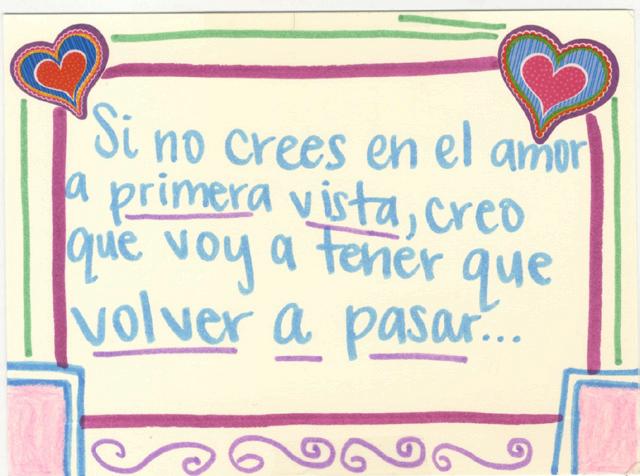

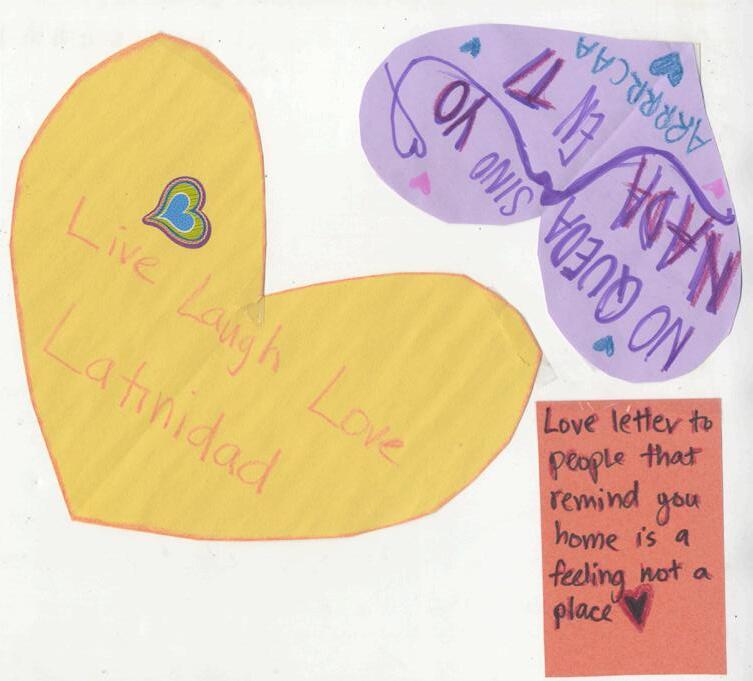

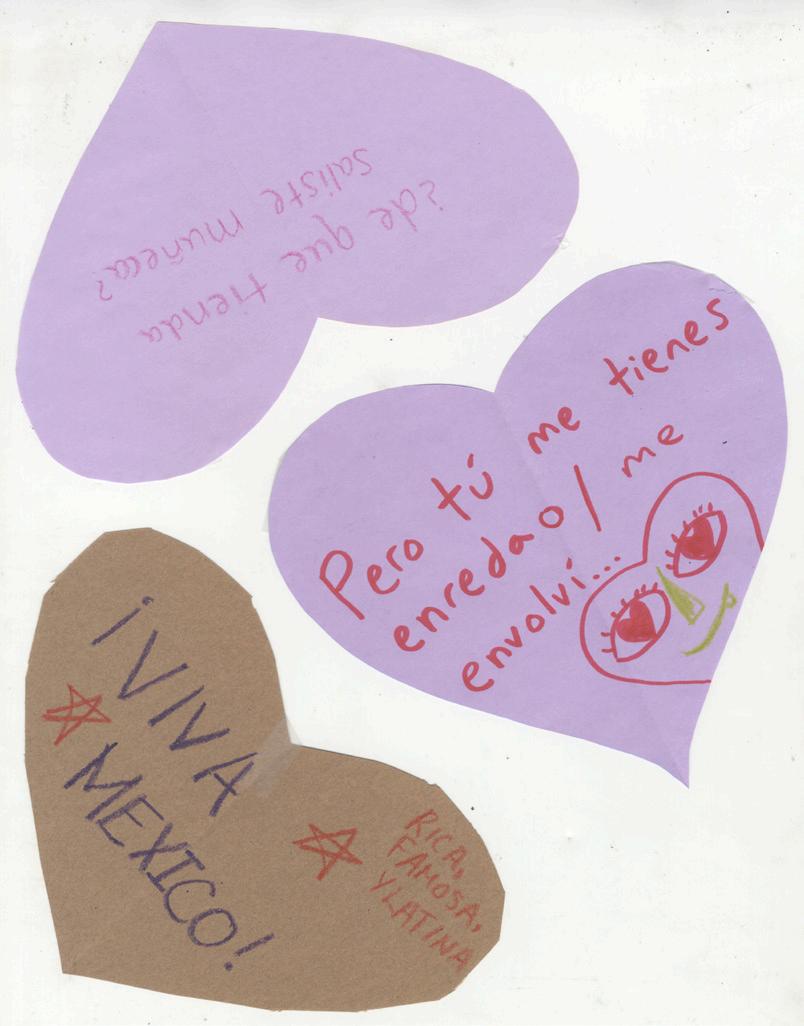

In honor of Dia de San Valentin, Latinxpresion decided to host our very own love letters event, during which people could craft their own corazones and write any message on them. To honor our theme of “Volando Bajito,” many culture, though any messenges were welcome! As people crafted their love letters, they taped the end result on one of the walls in the ALAS suite. By the end of the event, the wall was covered full of corazones that showed recuerdos of home and the beauty of culture.

Now that Carnaval is over how have the experiences of being assistant-director and performing Rumba/Salsa impacted you?

Yoana: I think the way it has impacted me is that I’ve been able to see what truly coexisting with other heritages within Latin American contexts looks like, how much fun it can be, and how rewarding it is! Being able to do both roles made me feel like I had much more commitment and involvement than what one role would’ve given me. I felt I was contributing even more to being able to showcase our cultures to WashU and people in the neighborhood that came to Carnaval.

What does this year’s Carnaval theme, Esperanza”, mean to you?

Yoana: In the past few years, so much has been going on in Latin America when it comes to politics and uprisings. So, being here, it can feel like you are not empowered because you are away and can’t do much. But Esperanza is a way of giving control back to us and being able to ask: “How can we help?” – even if it is though discourse and discussions on these different issues, in addition to recognizing the Western context that we are in. Therefore, “Esperanza”, which means hope in Spanish, is all about that, and giving each other hope even if we are in the United States.

How do you think Carnaval’s theme and Latinxpresión’s theme of “Volando Bajito” relate to each other culturally?

Yoana: It is just about being able to connect to a place even if you are not present. Volando Bajito is all about being able to connect home through different meaningful ways, so I feel like, in Carnaval you are also able to do that. In between the shows we ate food that connects to our own culture, and we are speaking in our languages. Culturally, they definitely amplify each other’s meanings!

Why do you think it is important for all Latine individuals to celebrate difference while simultaneously showcasing their cultures together?

Yoana: Latine countries are very different, including food types, languages and slang, clothing, and I think something I noticed in Carnaval is that we are all very different. It is also something I am learning more about. It is also very important to transmit this message to Washu and other people in general that all Latine individuals are not one homogenous group. So, when we are together in one space it is when visually you can see that come to life!

What was your favorite memory of Carnaval?

Yoana: Definitely making the hype video for Rumba/Salsa, which is the dance that I performed in. Some late nights hahah – very late nights during rehearsals – and when we recorded our video it was about creativity and showing our personalities; we really wanted that to come out in the video. It really helped us feel more confident in ourselves to prepare for the show!

Relating to that, how do you think that the experience of being in Carnaval has expanded your sense of creativity, and why do you think creativity is so important aside from academic while in a college setting?

Yoana: I think in a college context, it can be very demanding to focus solely on academics. Even if there is creativity within your courses, it can be very time consuming and you are always appealing to your professor’s expectations. So, being able to do something that is mostly student-run gives you the opportunity to share ideas openly and truly collaborate. Something we did in our choreography for Rumba/Salsa is that our choreo was always asking for our feedback and asking “Does this work for you?” or “Are you wanting to do this move with this song?”. Therefore, with this entire process, coming up with the shows theme and choreo, and at the end, our show’s order, it gave us flexibility and creativity, which is very important. Although these past few weeks have been very demanding with Carnaval, it has been rewarding and I am coming back to my academics stronger than ever!

Yoana: REMEMBER TO DO CARNAVAL NEXT YEAR!!!!

Before 1978, state child welfare and private adoption agencies preyed on Indian children. Forced removal under the false premise of abuse and neglect resulted in 35% of Indian children taken from their families and communities, and 85% placed in non-Indian homes. Widespread forced removal resulted in Congress implementing the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) in 1978. The intent of Congress under ICWA was to “protect the best interests of Indian children and to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families” (25 U.S.C. 1902). What makes ICWA different is it gives tribes the right to intervene at any time in child custody proceedings, the right to make recommendations regarding the placement of Indian children, and state welfare and adoption agencies must provide active efforts for possible reunification and placement of an Indian child. One of the biggest limitations of ICWA is the fact that it is a federal act which is often not complied with on the state level, specifically where Indian populations are low.

States regularly do not comply with ICWA, and judges are still able to choose a non-Indian home, even when a Certified Indian home is available. Currently, Texas, Louisiana, Ohio, and Indiana have openly challenged ICWA and represent a past of noncompliance. These states also have significantly lower Indian populations. Even as we are discovering hundreds of unmarked children’s graves at Residential schools, ICWA is still not complied with and challenged regularly. Research shows even now, Indian families are still four times more likely to have their children removed than their White counterparts.

My experience as a Coordinator in Indian Child Welfare was a shocking one. I worked for the Delaware Tribe of Indians; a very small tribe located in northeast Oklahoma. As a Coordinator, my role was to act as the Tribal Representative in court proceedings, assist and advocate for families, and ensure ICWA was complied with. Oklahoma has a strong partnership with ICWA due to 43% of the state being on Indian land. While I was a coordinator, I was faced with many obstacles. Limited financial resources provided by the federal government prevented the tribe from providing adequate care for their Indian children and families. I was faced with decisions on which child to help, and which child to ignore. Tribes also transcend state jurisdiction, so I was challenged with Indian children as far as California needing our assistance. We did not have the resources to help those children and they were lost in the system.

Culture is the root of Indian people. It keeps us grounded. Breaking that connection leaves children lost. ICWA is about our recovery after centuries of historical trauma and genocide. Indian children need a connection to their communities, culture, and require more than a nuclear family. Indian communities take care of each other, and our non-nuclear families have a significant impact on child-rearing. ICWA embodies this community effort and understands that reunification should always be the goal. This belief has somehow been lost in the welfare system.

Currently, Big Oil is challenging the premise of ICWA, calling it racist towards White US citizens. Tribal sovereignty is at stake, with Tribes owning 1/3 of land rich in natural resources. This challenge to the Supreme Court has nothing to do with the welfare of our children, but more to do with the dismantling of tribal sovereignty and access to our resources. As history shows, children were once one of those valuable resources. We must do better and advocate for Indian people, especially our most vulnerable; Indian children.

Ashlyn Newcomb, MSW

Ashlyn Newcomb, MSW