FEIRA PRETA

The Festival of Black Empowerment

The Festival of Black Empowerment

From the vibrant energy of São Paulo to the captivating rhythm of Salvador de Bahia. Madrid with Air Europa.

From samba schools and Baile Funk parties to Jiu-Jitsu classes and feijoada Sundays, Brazilian culture is everywhere in London. It’s reshaping the city’s sound, taste, and rhythm. The slang, the music, the food are all part of a growing cultural exchange that makes London one of the most vibrant, inclusive cities in the world.

This special Brazil Edition of Latino Life is your guide to that energy. You’ll find the �lavours of Bahia in London’s kitchens, the beats of our songs in the city’s dance�loors, and the voices of artists, entrepreneurs and educators who are shaping a new generation.

But to understand Brazil, we must also honour its roots. As writer Conceição Evaristo teaches in Escrevivência; turning lived experience into words, our stories begin with those who lived, felt and transformed them. To tell Brazil’s story through our Black and Indigenous voices, is to resist erasure and to rebuild.

And for this reason I chose to interview two incredible Black Brazilian women for the issue: Luedji Luna, one of the brightest gems of contemporary Brazilian music, and Adriana Barbosa, the entrepreneur and visionary behind Feira Preta - the festival celebrating the global Black diaspora. MEET

To love Brazil is to love its roots, to recognise that our beauty was born from struggle, that our rhythm is resistance, and that our joy is political. Whether in São Paulo or Shoreditch, Salvador or Brixton, our drums beat to the same pulse: one of resilience, remembrance, and reinvention. From bom dia to saudade, this issue celebrates the language, love, and spirit

Gabriela Vallim, Editor

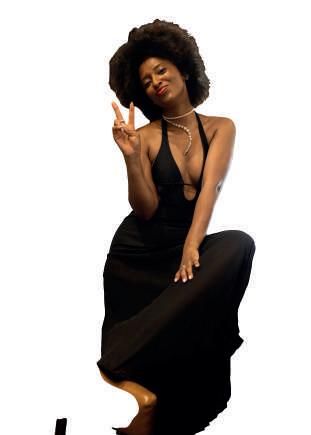

One of the brightest gems of contemporary Brazilian music, Luedji Luna fuses Afro-Brazilian rhythms, jazz and soul with poetry that honours her Bahian roots. Having just picked up two Latin Grammies, one for Best Brazilian Popular Music Album (MPB) for Um Mar Pra Cada Um, Luna is fast expanding the global reach of Brazilian music while staying deeply connected to her heritage, ancestry and collective creation. Gabriela Vallim speaks to the Brazilian artist on everybody’s lips.

It is a cold October day in São Paulo, Brazil’s largest city, as winter breaks into spring. In a Jeep Compass parked outside a shop selling Afro-Brazilian religious items

sits Luedji Luna, the stage name of Luedji Gomes Santa Rita, one of Brazil’s biggest stars at the moment, hot o�f a phenomenal Tiny Desk performance. “The police have stopped right in front of the shop. My husband and son are inside,” she tells me. “I want to see if the police will do anything, because then I’ll get out of the car and make a scene.”

It is the only tense moment during my interview with Luedji Luna, which has unfolded with ease - a calm, melodic exchange carried by the rhythm of Luedji’s voice. Her slow, lyrical cadence oozes the spirit of Salvador, the capital of Bahia, where she was born and where Afro-Brazilian culture pulses through everyday life

Only two weeks later, clad in a stylish suit, Luedji would �loat seamlessly through the glamour, glitz and applause of a Las Vegas ceremony to receive her Latin Grammy for her album Um mar para cada um. She will thank her parents. But it is clear in our interview that she doesn’t need an award to tell her who she is:

“At this moment in my career, Lued Gomes Santa Rita and Luedji Luna are aligned. They’re no longer so separate. She’s the closest to who I truly am, to what I truly want,” she tells me, going on to explain: “Sometimes, as artists, we find ourselves having to play the game of the industry, meeting expectations that aren’t necessarily our own, desires that aren’t completely genuine. But right now, I feel that I’m showing the most human version of myself, and that’s what I want the world to see. It’s about the possibility of an artist being �lawed, doubtful, vulnerable. Not a perfect or untouchable diva, not beautiful all the time, just human.”

And yet, Luedji did not look like an ordinary human up on that Grammy podium. The epitome of elegance and grace; she represents Bahia - the heartbeat of Black Brazil. As one of its strongest pulses, she carries the energy of its streets, its tides and its terreiros - the sacred community spaces in Afro-Brazilian religions like Candomblé and Umbanda, where music, dance and ritual connect people with their African ancestry. When Luedji sings on stages in London, Paris, or New York, her voice reminds us Brazilians that, however far from Brazil we are, there is always a drum calling us back.

“Have I not the right to exist without asking permission?”

Dressed in a hoodie and wearing a cap, the singer’s concern is palpable. I can see her eyes scanning her surroundings to ensure the safety of her family — all of them Black, like her.

When I received the news that I would be interviewing Luedji Luna, the scent of the trees, the voices singing and the rhythm of the atabaques replayed in my mind like a film: women in long white and yellow dresses walking alongside running children, men carrying fruit, drums, baskets and �lowers, moving together towards the river, in a procession both silent and vibrant.

Luedji’s art is like a river, pouring into the ocean, crossing the Atlantic. There are no linguistic barriers to the poetry in her music; it is something you feel. Fluid, powerful, serene. Sacred and accessible. She is a body in the world, Um Corpo no Mundo, that needs space to breathe, to tell her story.

“Even here in Brazil, I always make a point of a�firming my place as a Black woman. I don’t have a tragic story, which is o�ten what people expect from a Black woman. I had both my parents. They're still alive. I had education, love, and a good upbringing. My parents valued education deeply; they invested in it. So I make a point of showing that there are Black families with both parents, families that are functional and loving. Fathers who raise their children, who care for them. It’s important that we tell those stories too.”

“I’m not a mainstream artist in Brazil, but international artists and audiences still find me.”

A daughter of Salvador, the city where the Atlantic whispers stories of crossing and survival, Luedji carries in her voice the Axé, the vital energy that moves and transforms. In Candomblé, axé means spiritual energy or life force, the sacred power that connects all living beings and the orixás (deities). It represents strength, balance, and the ability to create and transform, to tell a di�ferent story.

“There’s a line in philosophy that says ’truth is a lie told many times’ . So let’s keep retelling stories of love, success, tenderness until they become the norm. Bell Hooks also speaks of these functional Black families, and that they must cease to be seen as exceptions,” Luedji says. “As a Black Brazilian singer, I don’t conform to what’s expected of me. Traditionally, the Black woman in Brazilian music is associated with samba. For many years that was the image. What’s expected of me musically, I don’t deliver.”

Luedji’s music is made of faith and memory. Her verses remind us that faith is a form of survival - not the kind of faith that demands silence, but the kind that sings, dances, and invites healing. In her lyrics, beauty is political; African spirituality intertwines with tenderness, everyday life and resistance. It is a kind of prayer made with the whole body.

Of course, the issue of representation is a complex one: “The ideal would be for

every Black person to be able to speak for themselves, without carrying the burden of representation. Can my story really encompass all the complexity of what it means to be a Black woman in the world?” sighs Luedji. “When I first came onto the scene, the idea of representation was something very present; people spoke a lot about it, and for good reason. We live in a country that still lacks our presence in spaces of power, in places that aren’t defined by violence, servitude, or vulnerability. Because we are so absent from positions of in�luence, from institutions, from politics, whenever one of us reaches those spaces, that person becomes precious, almost symbolic, and ends up carrying the heavy responsibility of speaking for everyone else who couldn’t make it there.”

To represent is not always something you choose, however, and you can’t always choose who you are representing, or control who feels represented by you. Luedji’s songs have become a meeting point for my students in the UK: young artists, DJs, dancers, capoeira players and jiu-jitsu practitioners from di�ferent parts of the world who find in Brazil a second home. They are moved by our resilience, that invisible strength which makes Brazilians keep smiling despite inequality, lack of opportunity, police violence, and racism.

“But that space of representation is limiting,” Luedji continues. ”For instance, Seu Jorge doesn’t need to be the only handsome one, the only heartthrob of his generation. There are so many beautiful Black men, not only in appearance but in essence.”

In recent years, Brazilian music has captured renewed international attention, with producers and artists looking to Brazil for inspiration.

“I’ve noticed this happening for quite some time now, I think Brazil is having a moment. It's kind of hype,” says Luedji, aware that she herself is now the focus of this attention, her inbox filled with messages from global names eager to work with her:

“Oddisee has already reached out to collaborate and shared some productions with me. John Key, who works with Solange Knowles — Beyoncé’s sister — has also sent me two productions.” She says, “I actually feel that people abroad are more atuned to this other Brazil beyond the samba stereotype than many Brazilians. They research more, they pay attention to what’s happening in the underground scene.”

Luedji has always resisted lending herself to being a Brazilian export. For Black musicians in particular, being constantly associated with samba has o�ten limited visibility and opportunity, and excludes innovative, quality art.

“My parents always listened to a lot of jazz and blues at home, and we travelled a lot too,” she tells me. ”That was my foundation. I think it’s re�lected in the kind of music I make today, music that speaks to the world, or at least intends to, rather than this idea of ‘exportable Brazil’.”

Fortunately, there’s a growing audience abroad seeking exactly this kind of music,boundary-breaking and deeply rooted in identity, and Luedji Luna has found listeners who genuinely seek depth and authenticity.

“I’m not a mainstream artist in Brazil, but international artists and audiences still find me, they listen to my music, and they see value in what I do,” she says. “Beyond the pop everyone knows, my Brazil is already being accessed abroad by people who genuinely love music, especially producers and DJs. I’m already reaching that market.”

It’s no surprise, then, that Luedji Luna’s second-largest audience, a�ter Brazil, is in the United States. And, as much as she hasn’t looked for fame and glory, it has now come, between our interview and its publication, in the form of a Latin Grammy.

Awards or no awards, Luedji will continue doing what she does. In a country that insists on silencing Black and female

bodies, Luedji refuses to be just a beautiful voice. She is a�firmation, protest, and self-care. Turning love, motherhood and Blackness into poetic trenches, she transforms the body into a political territory but also into a space of pleasure and freedom. And when audiences listen to her — especially Black women — they find mirrors. Luedji reminds us that resistance also means allowing oneself to feel.

Without having to create a persona or inventing a tragic backstory, Luedji is a woman with purpose, carrying in her body and soul a deep African ancestry that pulses through much of her music. Her album Bom Mesmo É Estar Debaixo D’Água (The Best Place to Be Is Underwater) feels like a deep dive into feminine waters vast, mysterious, and ancestral. “From carrying the world for so long, I learnt to �ly.”

“There’s no greater violence in history than what was done to enslaved peoples. If we’re still here, it’s because of an invisible, ancestral force that sustains us. The project is still ongoing. We do not die. We don’t end. We don’t disappear. Because we have them, our ancestors, the orixás,” she continues. “It’s in them that I find the courage to have a Black family, a Black husband, a Black child. It’s in them that I place my trust, because the State cannot be trusted.”

As I finish editing the interview, messages begin �looding in from Brazil a�ter yet another massacre in the favelas of Rio. Over a hundred Black bodies, including kids, fathers, students, even church people, killed. And once again, I am reminded of Luedji Luna’s words: “We don’t end. We don’t ever disappear.”

“We don’t end, we don’t disappear, because we have them, our ancestors, the orixás.”

Luedji Luna symbolises a Brazil that insists on reinventing itself, that keeps dancing even in the storm. A woman who understands that the act of creating is also the act of healing. “My music is healing for me and for those who listen. It’s a prayer.”

As I ask about what it means to inhabit a Black body in a violently racist society, Luedji’s audio begins to crackle. Through the screen, I can still see her glancing out the car window as if speaking to someone nearby. For a few seconds, the connection freezes and momentarily, as the background of Halloween merchandise fills the screen, my thoughts turn to how Black bodies were hunted just like “witches” were hunted in the Middle Ages. To my relief Luedji’s voice returns, though, unfortunately, not her face.

“We are vulnerable, exposed bodies. Black bodies living in an anti-Black country that wants to annihilate us,” she says in answer to my thoughts. “So, if we don’t hold onto something not necessarily the African-based religions, but to spirituality and to God we wouldn’t even have made it this far.”

What Luedji ‘holds onto’ is in her music. She sings to remember. To remember where we came from, who we are and where we wish to go. She sings of love that heals, that stitches colonial wounds and rebuilds belonging; the love that crosses oceans, connecting Salvador to Lagos, Kingston and London. Her verses touch the pain of a people, but also their joy. And it is in that fusion between pain and celebration that revolution dwells.

The sacred lies precisely there: in the one who sings, in the one who listens, in the one who allows themselves to feel. Perhaps that is what Luedji teaches us: that singing is also praying. And that, deep down, we are all made of water, Axé, and hope.

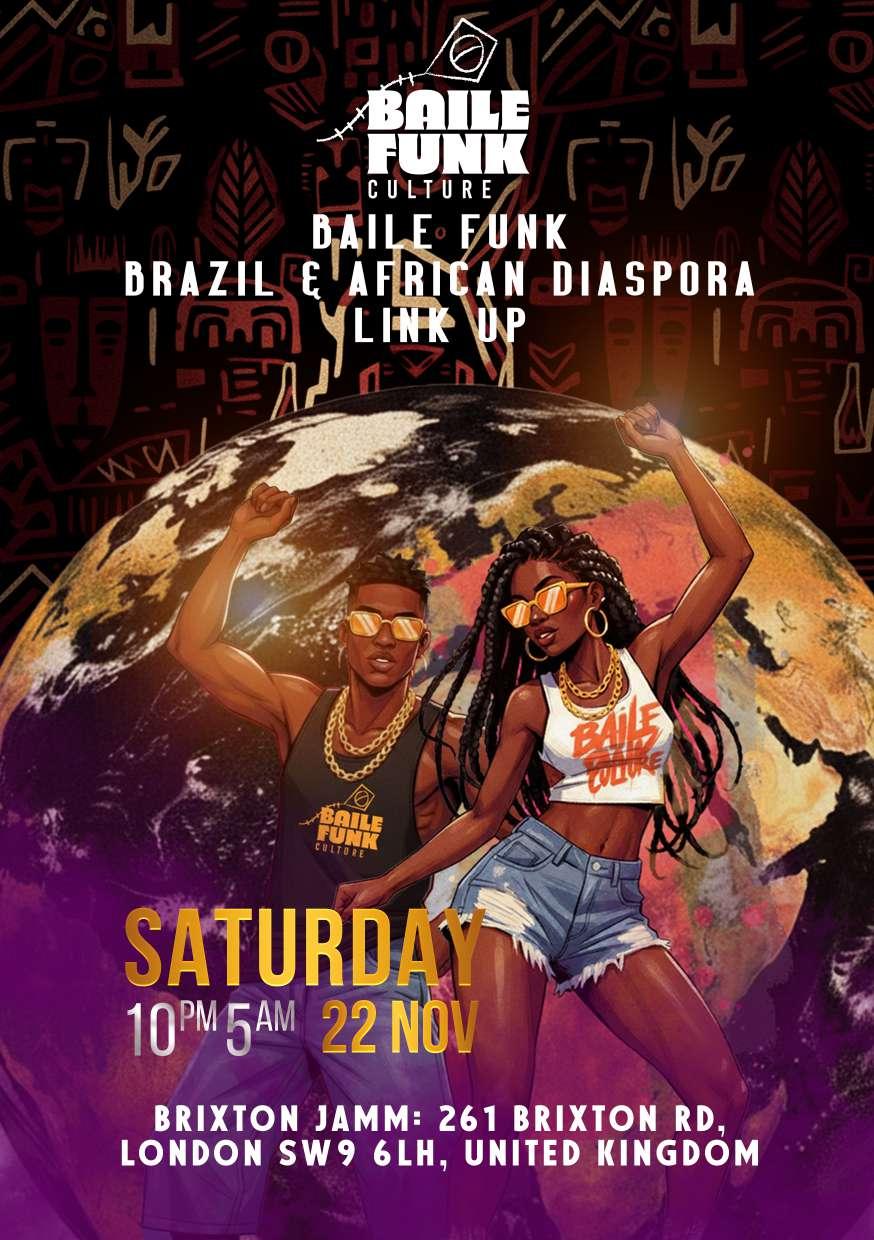

ondon's club nights are vibrating with something ancient and new. It's a sound where warm bells and brass of Highlife and Afrobeats collide with the pulsating, heavy bass of Brazilian Baile Funk—an intoxicating fusion that feels both utterly contemporary and ancestrally inevitable. Anthony Larbi and Gabriela Vallim describe the spiritual and cultural connection that bond two shores on opposite sides of the Atlantic, finding a natural home in London.

The connection between Brazil and Africa was already inevitable. As Brazil has the largest population of Afro-descended people outside of the Motherland. What is also destiny is that this connection is claiming dance�loors across London. What is emerging from the underground clubs, where Africans, Brazilians, and Londoners of all races celebrate life through music, isn't a �leeting trend to be commodified, it is a powerful

reclamation, a remembering. It is the rhythmic DNA of the Black Atlantic finally speaking its own name. The proof of this movement isn't just in the charts; it's on the dance �loor. The iron bells of Accra and Salvador don’t just share a lineage — they share a rhythmic blueprint that survived the Middle Passage

The historical beat: la clave’s shared code

To understand why Afrobeats and Baile Funk blend so seamlessly on London dance �loors, you must listen closely to the time-keeper. The instrument that dictates

rhythm for the entire ensemble. The heartbeat.

In Ghana, this is the Gankogui (or Gan Gan) —a double iron bell fundamental to Ewe and Akan traditions, The Gankogui anchors the time-line for traditional forms like Kpanlogo, whose core rhythm is identical to the clave found in Latin-Caribbean music. In Brazil, particularly within Afro-Brazilian religious music like Candomblé and secular forms like samba and maculelê, the identical function is performed by the Agogô.

Visually and functionally nearly identical, the Agogô and the Gankogui share more than aesthetic form—they share a rhythmic architecture. Both play recurring patterns known in ethnomusicology as the Standard Pattern, or more familiarly, la clave - a five-accent rhythmic code guiding countless Afro-diasporic genres.

The fusion we hear today is simply a new generation speaking an ancient, shared language—one that was never permitted to be forgotten. The 3:2 or 2:3 clave pattern they play is the memory, the pulse, and the ancestral agreement that binds the music of Accra, Salvador, and London.

The iron held the memory. The body remembered the pattern. Across the Atlantic, the beat survived.

Producer Juls, a leading architect of afrobeats, reignited this lineage through his 2025 documentary Travelling Man: Com Amor Brazil. Launched in Brixton, the film retraces connections between Ghana and Brazil via the Tabom community — Afro-Brazilians who resettled in Ghana during the 1800s.

Juls’s work is living proof of the beat that survived the Atlantic. It transforms heritage into sound, proving that the Black Atlantic is one continuous cultural ecosystem, not fragmented continents but a conscious collectiveness that is reawakening.

The London lab: where rhythm remembers itself

London’s clubs have become the laboratory where Afrodiasporic timelines and rhythmic grammar are translated into the future tense. If Ghana

and Brazil provided the roots, London is the rendezvous, the ultimate cultural melting pot for this reunion.

Baile Funk Culture (BFC) is dedicated to combating the "media whitewash" that has historically reduced Afro-Brazilian genres to shallow tropes, similar to how early Samba was o�ten dismissed. Through nights at Hackney Social, Dalston Den, Stereo and community projects blending music, art, and politics, BFC has built a space where South America, Africa, & the Caribbean all vibrate as Londoners and dance as one diaspora.

Each drop, whistle, and drum hit echoes those twin iron bells — the Agogô and the Gankogui — now vibrating through subwoofers and bodies refusing to forget.

Baile Funk was born in the 1980s favelas, inspired by Miami Bass yet rooted in Afro-Brazilian survival. It carried the joy,

sensuality, and pain of Black life in Brazil’s margins.When global fame arrived, its politics were stripped away. That’s why Baile Funk Culture exists: to restore meaning. Shaking your nyash is a political language, ancestral memory, and healing. We recognise art, culture and diversity as essential to the world we want to be part of. Art and culture save lives.

The connection between Ghana, Brazil and the UK isn’t history; it’s heartbeat. Africa birthed the rhythm. Brazil evolved it. London amplifies it.

In today’s clubs, what we hear isn’t fusion — it’s recognition. The DJ booth, the studios, the dance �loor: modern altars where descendants of forced migrationto hear it clearly again.

BFC Brazil & African Diaspora takes place on Saturday 22nd November 10 pm - 5 am Brixton Jamm, 261 Brixton Rd, London SW9 6LH

Anthony Larbi is director or (Motherland / On Da Beat Studio) Gabriela Vallim, founder of the collective Baile Funk Culture (BFC).

abriela Vallim interviews Adriana Barbosa, the entrepreneur and visionary behind Feira Preta - the festival celebrating the Black diaspora all over the world, which is today recognised as the largest Black culture and entrepreneurship festival in Latin America. In 2017 Adriana was listed as one of the 50 most in�luential Black people under 40 by the Obama Foundation and, in 2024, she was named one of TIME's 18 global leaders for racial equity.

Every November, as Brazil celebrates Black Consciousness Month, the name Adriana Barbosa gains renewed resonance. Adriana

embodies a generation that has transformed resistance into creation and opened paths for a new economy founded on ancestry, community, and innovation.

It was with this vision that, in 2002, she founded Feira Preta. What began as a small gathering of Black entrepreneurs and artists has become a living ecosystem that gives visibility, voice, and economic power to those historically excluded from mainstream markets. Through initiatives such as the PretaHub and the AfroHub, Adriana’s work continues to expand, reshaping what is known as the Black economy in Brazil and beyond.

Adriana Barbosa’s journey reminds us that Black entrepreneurship is not only an economic act but also one of healing and historical reconstruction. Her legacy continues to inspire Brazil — and the world — to rethink the value of creativity, the importance of representation, and the power of creating what does not yet exist.

Who is Adriana Barbosa – and what drives you?

“I recognise that my grandmothers, great-grandmothers, mothers, and aunts carried knowledge, practices, and narratives that sustained me.”

More than a festival, the Feira Preta movement connects identity, creativity, and sustainable development, revealing how the Brazilian creative economy is one of the most powerful engines for social transformation in the Global South. Over 12,000 Black entrepreneurs have been trained through its programmes, and more than 30 million reais have circulated within the Black economy — proof that when culture and innovation walk together, new models of collective prosperity emerge.

Iam

a Black Brazilian woman who grew up within a matriarchal

family, surroundedby grandmothers, mothers and aunts who were protagonists in our daily survival, community and care. They created economic alternatives. The women in my family taught me early on that true value lies in collectivity, collaboration, and the ability to turn resistance into creation.

What drove me was the need to exist fully and to open spaces for those who had never been invited. Today, as the founder of Feira Preta, PretaHub and AfroHub, I continue with the mission of transforming inequality into power, building platforms where Black people can see themselves and thrive, and showing that our knowledge forms the grammar of the future.

Feira Preta was born more than two decades ago and is now an international reference. What was your dream at that moment?

When I launched Feira Preta in 2002, there was already a vibrant movement in technology, design, health, beauty, fashion, art, and Black

music. Yet, there were few events that recognised the Black population as protagonists of market, consumption, and culture — not merely as its audience. I was not trying to “copy” international models; I was inspired by what did not yet exist but needed to.

Seeing Black women running informal businesses, taking my own first steps at street fairs, and realising that the money generated by Afro-consumption rarely circulated within our communities — I decided to create a space where Black producers could exhibit, sell, connect, and be recognised.

Today, Feira Preta is part of a much larger ecosystem, but its root remains the same: to give visibility and value to Black creativity.

In Brazil, faith plays a significant role in the lives of Black people. Do you consider yourself a spiritual person?

Yes, I consider myself a spiritual person, deeply connected to African diasporic religions and syncretism — not only in the traditional sense of

The women in my past found creative ways to survive. That living spirituality gave me strength during moments of uncertainty, when resources were scarce, when rejections were many, when fatigue pressed in. Faith, community and belonging were the values that allowed me to keep going. And today, when I look at the ecosystem we’ve built, I can see that spirituality — understood as respect for ancestry, collectivity, and purpose — is in the DNA of this entire work.

he Feira Preta ecosystem and its programmes are living laboratories of a new economy: one that sees Black “I o�ten highlight the idea of Afro-consumption in Brazil the fact that Black money circulates, but rarely stays within Black communities.”

faith,Brazilian but in the connection with ancestry. I recognise that my grandmothers, great-grandmothers, mothers, and aunts carried knowledge, practices, and narratives that sustained me.

FOver the years, your personal dream has become a global platform that upli�ts thousands of people. How has your definition of success evolved?

or me, success is not just about reaching numbers or recognition — it’s about seeing Black people prosper,

gaining access to credit, networks and markets, expanding their businesses, and building self-esteem. It’s realising that a dream which began humbly, as a street vendor, has become a global platform with tangible impact.

At the beginning, I had the support of the women in my family, friends, and those who believed despite the risks. But I also faced lack of resources, and invisibility. That made every achievement a collective one — success was not only mine, but also for those who were part of the network we were building.

The Global North o�ten embraces the aesthetics of Black cultures while overlooking their social and economic structures. What do you believe remains misunderstood about the Brazilian experience in this context?

Tculture as an asset, creativity as value, and ancestry as innovation. We are building narratives and models of sustainable development grounded in cultural authenticity and economic viability.

What tangible outcomes show how Feira Preta has impacted the lives of Black entrepreneurs and their communities?

Iv technology, fashion, and gastronomy, helping entrepreneurs move from survival work to strategic growth and value creation.The impact goes beyond financial outcomes — it is also symbolic and psychological: strengthening racial literacy, self-esteem, networks, and belonging, which reverberate across communities and redefine what is possible.

n just the past three years, the Feira Preta ecosystem has invested R$4 million in Black-owned businesses in areas such as

Many people still don’t fully understand what “Black economy” means. How would you explain this concept in simple terms

TIt is a tool for social transformation because it puts resources in the hands of those historically le�t at the margins, breaks cycles of invisibility, and circulates wealth within Black communities, generating autonomy, dignity, and belonging. I o�ten highlight the idea of Afro-consumption in Brazil — the fact that Black money circulates, but rarely stays within Black communities. The Black economy changes that dynamic.

“For too long, the market taught us how to survive, not how to prosper. We deserve not only to exist, but to thrive, grow, and multiply.”

he Black economy is the sum of the practices, knowledge, strategies of survival, creation, and prosperity of Black

people — especially the ways in which Black women mobilise resources, networks, culture, aesthetics, and ancestry. It is not limited to consumption, but to the creation of value through Black identity — in fashion, art, technology, aesthetics, and production networks.

You o�ten say that money is also about self-esteem. What does that idea mean to you?

When I say that “money is also self-esteem,” I mean that access to

resources, credit, markets, and visibility gives Black people the conviction that they belong, that their work has value, and that they can care for themselves and their communities.

For too long, the market taught us how to survive, not how to prosper. This statement is a call for reclamation — we deserve not only to exist, but to thrive, grow, and multiply. Money becomes a symbol of autonomy, possibility, and belonging.

Do you believe that the Feira Preta model could be replicated in London or other parts of the world? What would be essential to make it work in di�ferent cultural contexts?

Ibelieve that the Feira Preta model is highly replicable in London, which has a vibrant African Caribbean,

and Latin diaspora. What matters is adapting to local specificities — but the driving force remains the same: creating platforms for visibility, access, and networking among Black entrepreneurs, celebrating Black culture, and activating economic movement.

London, with its multicultural ecosystem, can embrace this proposal. The essence is universal: Black excellence is global. At the same time, I understand that every locality has its own dynamics — and adaptation is part of the strategy.

You’ve been working to reposition Brazilian entrepreneurship around the world, yet most Brazilians don’t speak other languages. What role does learning new languages play in the global Black economy? And do you intend to take an active role in that area?

Learning other languages plays two strategic roles: first, it opens doors to international dialogue, connections, and

markets beyond Brazil; second, it allows our stories to circulate without depending on translation or mediation.

Working within the global Black economy requires linguistic, cultural, and market �luency. Yes, I intend to act on that front — to take the Feira Preta/PretaHub ecosystem beyond borders, connecting with Africa, Latin America, and Europe. Part of that mission involves mastering multiple languages and codes.

Feira Preta was born at a time when few believed it was possible to create a project like yours — and today it’s a global reference. What do you think is society’s role in building initiatives that don’t yet exist, that may seem utopian at first?

There is no ready-made formula — only courage and purpose. Creating what does not yet exist means believing when no one else believes. And when no one believes , it’s time to

remember why you started: to look at the problem you want to solve, gather your network, mobilise your visible and invisible resources — symbolic, ancestral — and persist.

My journey shows that a small dream of selling at street fairs can become an international platform if we maintain faith, strategy, and community.

What advice would you give to young artists and creatives in London who face the challenges you encountered. And how can ordinary citizens support local businesses and artists so that these collective dreams can keep standing strong?

Challenges can become creative power. To every Black artist or entrepre-

neur starting out in London, my message is this: do not shrink in the face of rejection. Each “no” can be transformed into an opportunity to reinvent your path. Cultivate your identity, build your network, recognise your worth. And remember: you are part of constructing another possible world — one that is fairer, more diverse, and more collective. Your presence matters. Your product matters. Your culture matters. Let’s build this global Black economy together.

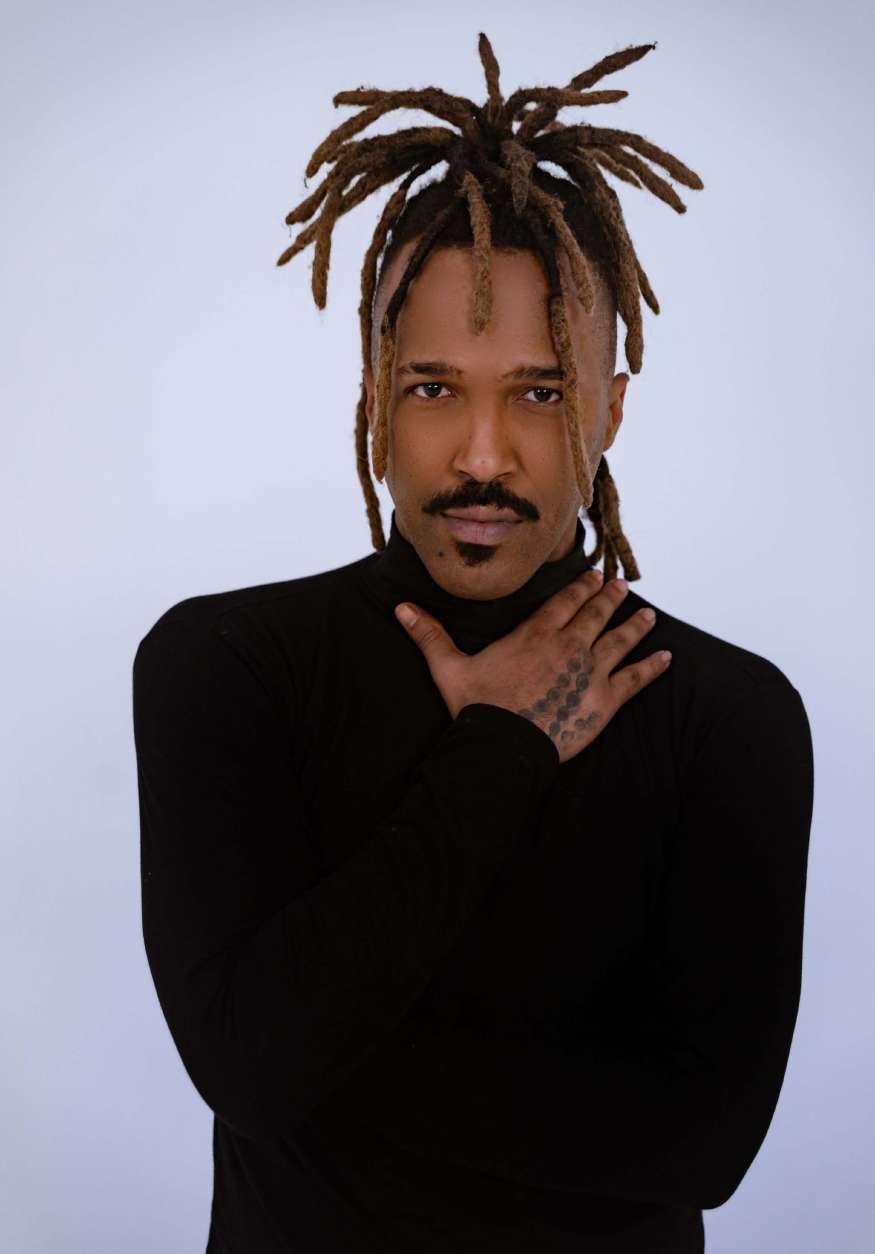

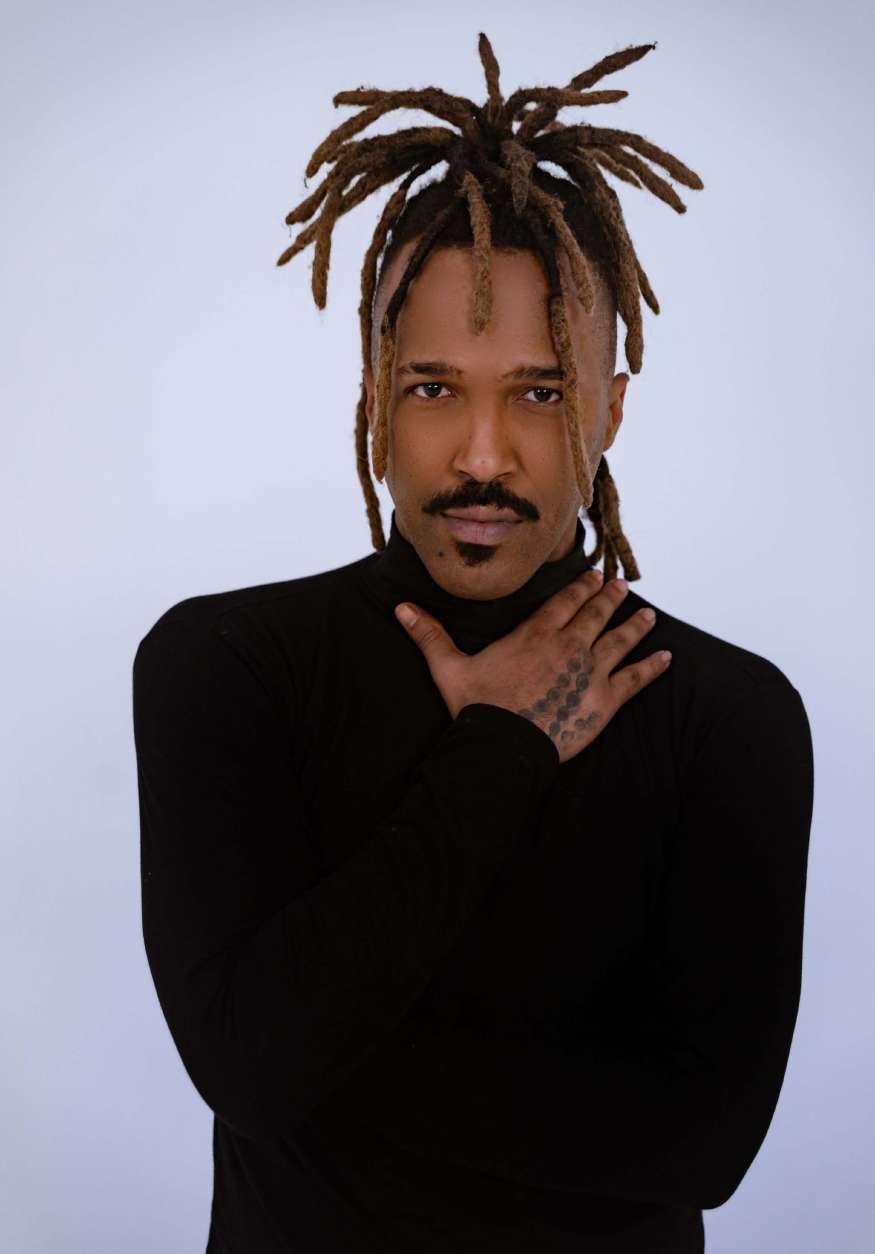

What happens when a South London artist who raps in Portuguese, English and Spanish with roots in Angola meets one of Brazil’s foremost percussion outfits? “It feels like the circle is closing,” said Afrocidade, when we hooked them up with lyricist

Broken Pen. Here is the story of a meeting of musical souls, as LatinoLife takes the British-Angolan rapper to perform with one of Bahia’s most exciting bands at

There’s a WhatsApp group called Afrocidade e Broken Pen. It was born at 11:31pm

on a humid October night — a digital circle between London and Bahia, where two worlds met on a screen and began to speak in rhythm.

The first message: Salve galera! Grupo criado. Seconds later, Broken Pen sent three voice notes — his freestyle spilling across the Atlantic. Someone replied, Kuduro Bahiano! And suddenly, the group wasn’t just a chat; it was the spark of a new movement.

That spark is Cultura Circular, a collaboration between Broken Pen, one of the UK’s sharpest lyricists, and Afrocidade, the electrifying Bahian collective known for transforming the ancestral pulse of Afro-Brazilian percussion into political celebration. Together they’ll write, record, and perform an original track at Feira Preta 2025, Latin America’s largest Black-culture festival — an event that turns São Paulo’s Ibirapuera Park into a living manifesto of African-diasporic pride.

Born in Angola, Broken Pen grew up in London amid the kaleidoscope of Caribbean, African, and British in�luences that shaped the city’s underground

sound. A lyricist who fuses spoken word,rap, and Afro-conscious storytelling to create transformative performances, a poet, rapper, and educator, Broken Pen bridges hip-hop’s social conscience with the storytelling of London’s spoken-word scene.

His name says it all: a writer who breaks pens so words can breathe.

“To collaborate with incredible musicians who speak my language — maybe not English, but something deeper,” he says. “This is a cultural space I’d never experienced before, but somehow I already understood through rhythm.”

“This is a cultural space I’d never experienced before, but somehow I already understood through rhythm.”

Broken Pen

With deep roots in both African and urban British culture, his voice resonates across continents. Having performed at the LatinoLife stage at Brixton’s Lambeth Country Show he was the first artist LatinoLife thought of when we were asked to bring a London artist to Feira Preta to build bridges between African diasporic identity and Brazil’s vibrant urban and cultural scenes.

When Broken Pen first logged into Zoom with Afrocidade, he didn’t know what to expect. “Everyone was so open and encouraging,” he recalls. “From the start, it felt like we were meant to shine together.”

Afrocidade was founded in 2011 by Eric Mazzone, during percussion workshops where he worked as an art educator at the Cidade do Afrocidade: The Power of Rhythm, Identity and Collective Creation

Saber Music Center in Camaçari, Bahia. Drawing inspiration from “current Africa and other possible Africas,” the group challenges North-Atlantic notions of what contemporary music should be.

For Afrocidade, creativity is born from collective energy — a euphoric exchange between band and audience that shapes their sound. “Live experiences are our strongest foundation,” says Mazzone (vocals, musical direction, drums). “That’s where we build our art and share energy. Our event Afrobaile is proof of that.”

The band’s core lineup includes Fernanda Maia (vocals & percussion), Deivite Marcel and Guto Sobral (vocals, dance & percussion), Rafael Lima and Douglas Santos (percussion), Marley Lima (bass & synth), and Sulivan Nunes (keyboard & live PA).

Their sound fuses politicised lyrics with ancestral, African, Jamaican, and Brazilian rhythms — the result of more than twenty years of sonic research blended with electronic processes. Beyond celebrating Africa’s drums, their lyrics rea�firm the strength and in�luence of Bahian identity — music as both celebration and resistance.

Broken Pen: From South London to Salvador

With di�ferent time zones, languages, and ways of working, the first virtual meetings could have been awkward — but the chemistry was instant.

“At first, we thought it would be a challenge,” says Mazzone. “But when we heard Broken Pen’s �low, we felt a sincere connection. Both sides were excited and open. That gave us confidence.”

Since then, their chat has become a virtual rehearsal room: beats, basslines, and laughter �lying across continents. They’re already sketching the live setlist — mixing Broken’s London grime and soul with Afrocidade’s Afro-Bahian percussion.

“Projects like this feed our dreams,” Mazzone says. “They remind us that art has no borders.”

“When we heard Broken Pen’s �low, we felt a sincere connection. Both sides were excited and open. That gave us confidence.”

Broken Pen arrives in Salvador, where the band will record and rehearse at the legendary WR Studio — the birthplace of much of Bahia’s modern music. Afrocidade will handle the local production; Latino Life will oversee mixing and mastering, ensuring the track resonates across Brazil and the UK.

With di�ferent time zones, languages, and ways of working, the first virtual

Afrocidade see deep kinship in this meeting: “We’ve spent years researching sounds that connect us to Africa and its diaspora. To now meetings could have been awkward — but the chemistry was instant.

“At first, we thought it would be a challenge,” says Mazzone. “But when we heard Broken Pen’s �low, we felt a sincere connection. Both sides were excited and open. That gave us confidence.”

Since then, their chat has become a virtual rehearsal room: beats, basslines, and laughter �lying across continents. They’re already sketching the live setlist — mixing Broken’s London grime and soul with Afrocidade’s Afro-Bahian percussion.

share that process with an artist who raps in Portuguese, English, and Spanish, and whose roots reach Angola — it feels like the circle is closing. This is the beginning of a friendship, maybe a movement.”

Broken Pen agrees: “It’s been incredible discovering how we complement each other. I can’t wait to step into the studio and then on stage with Afrocidade. Going to Brazil and smashing that show — that’s the dream.”

“It feels like the circle is closing. This is the beginning of a friendship, maybe a movement.”

“Projects like this feed our dreams,” Mazzone says. “They remind us that art has no borders.”

Broken Pen arrives in Salvador, where the band will record and rehearse at the legendary WR Studio — the birthplace of much of Bahia’s modern music. Afrocidade will handle the local production; Latino Life will oversee mixing and mastering, ensuring the track resonates across Brazil and the UK.

The collaboration will culminate at Feira Preta 2025, where they’ll premiere their joint track and perform together on the festival’s main stage. More than a show, it’s a reunion of histories — a dialogue between the drums of Bahia and the verses of London, between ancestry and modernity, between what was taken and what has returned.

As the WhatsApp group keeps buzzing — voice notes, emojis, and midnight beats — one message lingers on the screen:

O groove falou por nós. The groove did the talking.

Because when Bahia’s drums meet London’s bars, when the beat speaks both Portuguese and English, you realise the same language was always there — waiting to be heard, danced, and lived.

If Brazil is a land of infinite sounds, then Bahia is the ancestral heart that sets its tempo. In this top eastern corner of Brazil, every beat finds its origin in the force of nature, in the memory of the body, and in the sacredness that permeates the culture. The atabaque is far from just an instrument—it

sets the rhythm and charts the passage of ancestry, stretching from the Recôncavo to the capital. Bahian music is not merely heard, it is intensely lived; it is memory in motion, transformed into a political body that sings, through art, its own story.

Bahia’s e�fervescent contemporary scene is a direct heir of centuries of cultural invention. From the ritualistic chants of African litanies to the innovative beats of today’s urban peripheries, artistic production in Bahia is synonymous with resistance and constant reinvention. Its cities, such as Salvador, Feira de Santana, Santo Amaro, Cachoeira, embody true urban quilombos of sound, dance and a�fection.

We asked Bahian journalist and visual artist David Sol to choose ten places and experiences that keep Bahia’s sonic soul burning, stitching past and future in the same drumbeat. These spaces straddle Bahia as the cradle of Brazilian music and laboratory of its future inventions, where a�fection and art walk hand in hand; faith and groove intertwine. In every party, terreiro or cultural centre, there is a gesture of resistance and beauty that tells Brazil—and the world—that Bahian art is more than expression: it is existence. Translated by Gabriela Vallim.

Ṣíbí Dúdú

síbí Dúdú stands as one of Salvador’s most powerful celebrations, elevating samba to a ritualistic dimension. The event blends

samba de caboclo, performances, and arts in an atmosphere where the sacred and the profane coexist and dance in perfect harmony. More than entertainment, each edition of Ṣíbí Dúdú is felt as a sonic o�fering to ancestry, rea�firming samba as a living and deeply spiritual language—one that seeks to reconnect with the musicality of the terreiro.

@sibi_dudu

Casa Preta

Cultural Centre

Located in Dois de Julho, Casa Preta is an independent, political and a�fective space dedicated to concerts performances, and ,

artistic residencies focused on Black and peripheral production. Here, music acts as a tool for education, gathering and collective healing. The sound that echoes from its walls is not just entertainment—but the sound of the future, built upon the powerful memory of yesterday, solidifying itself as a centre of cultural resistance.

@casapretaespacodecultura

Casa Rosa

Music venue

Once a historic house of bohemian spirit and a�fection in Rio Vermelho, Casa Ros a has re-emerged as one of the most vibrant

hubs of Salvador’s new music scene. The venue serves as a convergence point for independent artists from Afro-Bahian music, alternative sounds, and electronic beats, with a line-up that bridges and intertwines generations. At Casa Rosa, sound blends with the sea breeze, and musical tradition gains fresh, contemporary tones at every event.

@casarosasalvador

Theatre

Teatro Gamboa is recognised as the prime stage for Salvador’s contemporary and experimental scene. The venue has become a laboratory

for sonic and political experimentation, hosting everything from spoken word events to poetic performances.

@teatrogamboa

Samba da Feira

Pier da Feira de São Joaquim

Every Sunday from 1pm

Amid the hustle of stalls, fruit and scents of the Feira de São Joaquim, Samba da Feira is the living pulse of Bahia’s

popular culture. Born from a spontaneous gathering of friends, the project has become one of the most authentic spaces in the city. Between the beat of the tamborim and the comings and goings of market vendors, samba blends into the everyday, giving Salvador back its own soundtrack. Samba da Feira is a lesson in community and resistance—a space where people celebrate themselves in a circle.

@sambadafeira.ba

Cultural Centre

At the creative heart of Salvador, Espaço Multicultural Alohaxé is a crossroads of languages—a meeting point between art,

spirituality, and movement. Created by artists and producers who view the body as a territory of creation, the space hosts rehearsals, performances, and experiences that connect the sacred with the urban, the drum with the digital. Every action at Alohaxé is a call to presence, an invitation to experience axé as a creative force and to share the power of Afro-Brazilian cultures in their most contemporary form.

@alohaxe.studio

Foto: Divulgação Teatro Gamboa

Divulgação Afropunk Bahia

The Afropunk Festival has turned the Bahian summer into a true global quilombo, placing Salvador at the centre of the creative diaspora

and the celebration of Black power in all its forms—from Afrofuturism to pagodão baiano. The event is a cultural crossroads where fashion, music and politics intertwine. Here, the stage becomes an extension of the streets, and axé meets trap in a rhythmic encounter where percussion serves as both an act of revolution and a celebration of Afro-diasporic culture.

@oafropunkbrasil

Casa do Benin Cultural Centre

Divulgação Casa do Benin

Located in Pelourinho, Casa do Benin is a powerful symbol of the diaspora in dialogue—functioning as a cultural bridge

between the Atlantic and the African continent. Through exhibitions, circles and musical performances, the space celebrates Afro-Brazilian and African art, rea�firming that music is a vital spiritual link between continents and generations. It is a place where ancestry meets and renews itself in the daily life of Salvador.

@casadobenin

Weekly party

Created by cultural producer Matheus Morais, Samba de Quinta has become one of the most vibrant manifestations

of the new Bahian samba generation. The project has transformed Thursday nights into celebrations of living tradition. Samba de Quinta rea�firms Bahia as a vital territory of rhythmic resistance, where each samba circle transcends entertainment to become a powerful act of memory and a�fection.

@osambadequinta

Cultural Centre

The life and legacy of the great shellfish gatherer from Nagé, Tonha Preta, �lourish in Salvador as an authentic

space of ancestry and Afro-Brazilian culture. Named in her honour, the venue celebrates the Recôncavo Baiano and translates her story into soul food, where �lavours from the waters—molluscs and shellfish—are the heart of the dishes. To enrich this temple of taste, music pulses with the infectious energy of samba, establishing the venue as a vibrant gathering point that upli�ts Black beauty.

@tonhapreta

nown as Bibiu, or as the "Choreographer to the Stars," he is one of Brazil’s best known dancers and choreographers and is a favourite among the country's top artists. Having travelled the world, primarily for Anitta, his shows and performances have repeatedly gone viral. Oopsy Daisy finds out the things that matter to Edson Damazzo.

Ialways loved to dance, to act. As a child I was fascinated by TV and the movies and learned how to dance all

the popular dance crazes of the time,like É o Tchan. As a teenager, I looked for a studio with dance and theatre classes and then I started taking ballet. I graduated as a dancer and began to work and earn money from it—traveling abroad, working on TV and with artists. Through this, I discovered a talent for directing and choreographing.

Theatre helped me a lot. There, I realized I had good ideas; I invented scripts, scenes and I saw that was what I wanted for my life. Later, I graduated from a professional school for ballet and jazz, and at the same school, I became a teacher and director for many years.

There weren't many successful Black choreographers in Brazil when I was growing up. Most were white: Daniela Marcondes, Caio Nunes, Regina Miranda, Washington Cardoso, Alice Arja, Kátia Bardos, Vânia Reis, and others. I was in awe of everything they did. Later, I started to turn my attention to the great American choreographers—the choreographers for Beyoncé, Cardi B, Britney Spears and Madonna.

I love being Brazilian; we are di�ferent from the entire world. Brazilian dance culture is an explosion of colours, rhythms, and energy. Samba, forró, frevo... each of these dances has its own vibe and history. Brazilian dance inspires me through its diversity and the contagious joy it transmits. It's as if every movement is a celebration of life!

“Samba and funk aren't just dances—they are cultural manifestations that carry histories, struggles and triumphs….”

Politically, dance can be a powerful tool. In Brazil, samba and funk aren't just dances—they are cultural manifestations that carry histories, struggles, and triumphs. It's a way to give voice and visibility to marginalised groups, to question structures, and to promote social change.

The important thing when taking funk and samba to international stages is to maintain the essence and authenticity of these cultural manifestations. I always try to deliver the best we have to o�fer without losing our originality.

The biggest challenges for Brazilian dancers abroad is dealing with cultural and artistic di�ferences, in addition to overcoming language and financial barriers. Many dancers face di�ficulties finding work and recognition in other countries, especially if they don't have a network or international experience.There are several scholarship opportunities and programs that can help …like Erasmus Mundus, which o�fers scholarships for master's degrees in dance in Europe, and the Fulbright Program, which o�fers scholarships for Brazilians to study in the USA.

Brazilian artists have contributed to the international dance scene, like Deborah Colker, who was the first woman and Latin American to direct a Cirque du Soleil show, and Ingrid Silva, who is one of the first Black ballerinas to perform with the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Tradition is constantly evolving. So, while respecting the past, it's possible to create something new and original that re�lects current reality. Samba is a global symbol of Brazilian culture, but it's important to preserve its authenticity and essence, ensuring that globalization does not distort it.

The advice I’d give Brazilians abroad is don't lose your connection with Brazilian culture. Always seek to learn more about your origins and share them with others. Don't try to mold yourself to what you think others want to see. Be true in your art and expression.

Being in the diaspora can be a challenge, but it's also a chance to learn and grow. Seek out training opportunities, performances, and collaborations. Find other Brazilian dancers and artists in the diaspora and form a support network. This can help keep the culture alive and create new opportunities.

ão Paulo, known as terra da garoa, “the land of drizzle,” is Brazil’s largest city, home to over 21 million people. Latin America’s financial and cultural powerhouse, the city pulses with energy, contradictions and stories waiting to be discovered. Gabriela Vallim proposes the best of her home town.

Adestination for Brazilian migrants seeking a better life, São Paulo, a�fectionately known as Sampa, was built

by people like my father, who le�t the northeastern part of Natal, Brazil, as a child.

It has also been a magnet for international migrants; home to the largest Lebanese community outside Lebanon, and to Liberdade, the Japanese neighbourhood glowing with red lanterns, where the smell of tempura mingles with pastel dough frying in oil. Between República and Vale do Anhangabaú, you’ll find a slice of Lagos. Inside the multi-storey Galeria do Reggae, you might feel as if you’re in a shopping mall in Abuja: hearing Yoruba and Igbo spoken in the corridors, finding ingredients to prepare fufu, jollof rice and egusi and seeing Black women driving the local economy through their hair salons.

This is the city of gra�fiti, rap battles, poetry slams in the favelas and samba from the Velha Guarda (old skool), the birthplace of samba rock. It is also home to the bailes de favela and the famous �luxosMy, spontaneous street parties where booming speakers and motorbike stunts take over each corner. Young people gather to dance to the pulsating beats of baile funk, celebrating life, identity, and resilience.

Dancehall has become a staple in São Paulo’s peripheries over the past decade. The genre brings thousands

together every weekend, from small community bars to massive street parties. Notable hubs include Jardim Peri, Cidade Líder, Monte Kemel, Grajaú, and Guaianazes.

In Itaquera, where I am from, Felipe Silva, also known as DJ Fya Sound, hosts the celebrated 3Coco party, bringing up to 2,000 people fortnightly. Meanwhile, the Dancehall no Morro collective in Favela do Sapo, northern São Paulo, blends music, social awareness, and community activism.

Artists like Lei Di Dai, dubbed the queen of Brazilian dancehall, perform and run sound systems, such as Gueto Pro Gueto. Female DJs and collectives, such as Feminine Hi-Fi, are following in the footsteps of Sister Nancy, the first female dancehall DJ in history.

São Paulo is the city of Racionais MCs, Brazil's most in�luential rap group. Its members, Mano Brown, Edi Rock, KL Jay and Ice Blue, turned street poetry into a national movement.

Baile funk is now part of São Paulo’s public policy, recognised for its role in acultural and social

development. In areas like Cidade Tiradentes, initiatives support local artists and integrate funk into the city’s cultural agenda. Journalist Rúbia Mara, the first funk culture coordinator at São Paulo City Hall, continues to be a key figure in advancing these e�forts, promoting funk as a powerful tool for inclusion, representation, and community empowerment.

The Museu Afro Brasil is one of the city’s most vital cultural landmarks. It is dedicated to the research, preservation, and exhibition of art and artefacts that celebrate the Black Heritage

Capoeira at Praça da República history and creativity of Black Brazilians.

ESão Paulo, which received many Africans during colonisation, continues to bear the marks of this heritage through capoeira, Afro-Brazilian religions like candomblé and umbanda, and samba and feijoada, all living expressions of our African ancestry movement, and tradition.

very weekend, the iconic Roda de Capoeira at Praça da República, right next to República metro station, brings together people from all over São Paulo to share rhythm,

Capoeira, an Afro-Brazilian martial art that blends dance, music, and acrobatics, was created by enslaved Africans in Brazil as a form of resistance and cultural expression. Today, it stands as a living symbol of freedom, community, and heritage.

This historic roda was founded by Mestre Ananias, originally from Bahia, and has become one of the most traditional gatherings in Brazil. Over the years, legendary capoeiristas such as Mestre Suassuna (Cordão de Ouro), Mestre Camisa (Abadá Capoeira), and members of Senzala from Rio de Janeiro have played and sung here, preserving the spirit of Capoeira Regional, Angola, and Capoeira de Rua for future generations.

In addition to the classes, the Capoeira Viva website o�fers an extensive audiovisual archive and online project dedicated to documenting the history of capoeira in São Paulo. It serves as both a source of knowledge and entertainment, featuring exclusive videos created by capoeiristas, for capoeiristas.

The cultural vibrancy of São Paulo is alive in events like the Baile da DZ7 in Paraisópolis, the city’s largest favela, home to nearly 80,000 residents. Since the early 1990s, this iconic street party has been a gathering point for young people from the city’s outskirts, where music, identity, and community intertwine.

In Heliópolis, a�fectionately known as Helipa, the Baile do Helipa stands as another landmark of funk culture, one of the region's most enduring and celebrated parties. Every weekend, spontaneous �luxos take over streets and alleys as crowds dance from Friday to Sunday night, echoing rhythms immortalised in songs like Baile de Favela.

Across São Paulo’s favelas, baile funk is far more than nightlife; it’s a form of Black cultural expression and resistance. Yet these spaces of joy and creativity face constant repression. Since 2012, at least 16 people have been killed and six teenagers blinded in police “pancadão” operations, according to research by Unifesp.

The most tragic case, the Paraisópolis Massacre of 2019, le�t nine young people dead a�ter a police raid on a funk party. Five years later, no o�ficer has been convicted. Authorities justify the crackdowns with noise complaints, but researchers point to more profound inequality: leisure in poor, Black neighbourhoods is criminalised, while nightlife in wealthier districts faces little scrutiny.

Still, the funk scene endures and young people transform everyday struggle into art, a powerful reminder that in Brazil, joy is an act of resistance.This is a city where love blossoms amid chaos, collaborations emerge from unlikely encounters, and partying becomes a circular economy. There is love in São Paulo in the bodies that resist, reinvent, create and dance.

Among the initiatives shaping São Paulo’s Black cultural scene, Africanize stands out as a leading force. Founded in 2014 by Wanessa Fernandes, the platform has become one of Latin America’s most in�luential voices in celebrating and amplifying Black culture. With over six million followers, Africanize goes beyond being a news portal; it's a movement that bridges education, art, music, and Black entrepreneurship. Through projects such as Africanize Party and Africanize Sessions, the platform connects artists, producers, and communities, merging online visibility with real-life cultural impact. This spirit of collaboration between parties, collectives, and independent media is vital to understanding the richness, diversity, and creative power of São Paulo’s Black culture and its contribution to the city’s cultural and economic landscape.

A city of rain, rhythm and resilience proves that love truly exists in the streets, sound systems and stories of those who keep it alive. For young travellers, this is a São Paulo that dances, creates and celebrates life, rain or shine. So here’s a musical journey through the sounds of the diaspora in São Paulo, the one I lived, the one I still carry from afar and the one that keeps dancing, even when it rains.

ASunday samba circle held at Cruz da Esperança, an old community sports club in Casa Verde (north São Paulo). It’s

more than a musical gathering it’s an urban quilombo that keeps the spirit of samba and community alive.

@samba_do_cruzz

Discopédia - Founded in 2012 by DJs Dandan, Marco, and Nyack, this event celebrates vinyl culture, the art of the DJ, and Black

music in all its forms, including rap, soul, funk, jazz, and beyond, right in the heart of downtown São Paulo.

@discopedia

Created by two friends who turned their passion for music and community into a celebration of Black culture. With

its welcoming atmosphere, diverse line-up and warm hospitality, the event brings people of all ages together to dance, connect and celebrate the joy of Brazilian identity every Sunday.

@adomingueira

One of Brazil’s largest samba circles, created in 2018 by brothers Magnu Sousá and Maurílio de Oliveira, in

partnership with Margareth Valentim. The audience becomes part of the show in four uninterrupted hours of live samba, acoustic and intimate.

@quintaldosprettos

Founded in 2010, this collective is a leading force in São Paulo’s reggae and sound system culture. Their parties bring Jamaican

energy to Brazilian dance�loors, a complete celebration of vinyl, bass and Black sound.

@freshdancehall

Is a traditional party in the Liberdade neighbourhood that celebrates música preta dançante, dancing to Black music

like soul, original funk, samba-rock, and brasilidades. It brings generations together in rhythm and nostalgia.

@equipemusicaliando

BAILE DA LUXURY

For over 12 years, this party has been one of São Paulo’s most iconic celebrations of Black music, empowerment and

community. With Afrobeat, hip hop and Black charm, it brings together the city’s top DJs in the heart of downtown.

@baile_da_luxury

Acelebration of Afrocentric love, dance and rhythm that connects diasporic communities through

music, style and togetherness.

@afroloversoficial

Is an urban quilombo founded by Érica Malunguinho. It mixes popular and fine arts while amplifying Black and queer

voices. The venue hosts exhibitions, performances, and discussions, featuring works by artists like Dona Jacira, the mother of rapper Emicida, a living link to ancestry and resistance.

@aparelhaluzia

Created by KL Jay from Racionais MCs, this iconic São Paulo baile (party in English) has promoted Black music for

over two decades, blending soul,jazz, MPB, rap and samba-rock. With resident DJs like KL Jay, Ajamu, Marco and Will, Sintonia is more than a party; it’s a cultural community.

@sintoniafesta

razilian culture is a dazzling celebration of life, bringing together music, dance, and vibrant community spirit. At the heart of this energy lies the favela aesthetic—unexpected beauty blossoming in urban neighbourhoods, where artists and designers blend in�luences their Brazilian heritage with local and contemporary �lair. Hayala Campos explores how this unique style, full of bold colours and eclectic designs, is shaping the future of fashion and art in exciting ways. From streetwear that tells a story to art that speaks of resilience, she uncovers the fresh and dynamic impact of favela aesthetics in today’s fashion scene. Photos by Emy Barbosa

Growing up in Queimados, a small community in Rio de Janeiro, my surroundings were vibrant with colourful murals and the rhythms of samba and funk, yet art and fashion weren't part of my early experiences. As I navigated the fashion world at London College of Fashion, I realised that, although I o�ten felt di�ferent to my classmates, my Brazilian roots o�fered a unique perspective. Drawing inspiration from the street culture and urban art where I grew up, this distinctive aesthetic enriched by bold colours and intricate patterns would come to infuse my work as a fashion communicator and storyteller in the industry.

But I’m not the only one in�luenced by baile funk beats, bold streetwear and Brazili’s DIY creativity. On global catwalks and stages, ‘favela chic’ has already made its appearance, as in Rosalía’s funk-infused showcase at the Louis Vuitton Fall-Winter 2023 show in Paris, Rihanna’s Super Bowl hal�time show incorporating funk beats and Beyoncé’s dynamic passinho dance during her performance at Rock in Rio. These moments illustrate how favela aesthetics are moving from the margins to the mainstream, leaving an indelible mark on contemporary style.

In the UK, two independent brands Lodge Brava and FLAMENCO, founded by Brazilian creatives based in London, stand out. FLAMENCO designed by Sharon Flamenco blends high fashion and street style using a range of cra�tsmanship techniques that result in elegant, environmentally friendly and innovative designs. Meanwhile, Lodge Brava directed by Charles Base o�fers fresh perspectives and �lair that celebrate resilience and innovation by blending modern sport elements and raw style in�luences from marginalised communities.

Meanwhile, back in Brazil, Massati a São Paulo–based label founded by artist Matheus Santos, merges fashion, music, and emotional storytelling. Handmade in small batches, Massati’s pieces express freedom, identity, and self-esteem while promoting equality and authenticity. The list goes on with Dendezeiro, Piet, Az Maria’s and Isa Silva catapulting these dynamic in�luences into the global fashion and creative industries.

The journey of Brazilian creatives, whether living abroad or at home, is a celebration of roots, identity and cultural representation in art and fashion. Brazilian aesthetics within the fashion industry invites everyone to re�lect on their own cultural narratives through their artistic choices. By supporting diverse voices, curators and consumers can help cultivate a vibrant fashion industry that champions inclusivity and innovation. That way we can inspire a deeper appreciation for cultural stories and enrich the fashion landscape.

Hayala Campos is a fashion journalist and content creator @hayalacampoxx Emy Barbosa @emydaora

By Gabriela Vallim

Friends, students, and Brazilian lovers always ask me the same question: “Where can I eat, dance, or experience a bit Brazil in London?” The list,

believe me, is of long and full of �lavour. Of all the cities I’ve lived in and travelled to, London is the one where I feel closest to home. Whether it’s through food, the vibrant parties that echo with samba, forró and baile funk, or the warmth of the Brazilian community that gathers to celebrate our culture, this is where Brazil beats strongly beyond its borders. Walking through certain streets, you can hear Portuguese blending with accents from around the world. You can find a little piece of Brazil on every corner: in festivals, capoeira circles, and cultural gatherings that connect rhythms, memories, and emotions.

Nowhere is this more vivid than in Brent, home to one of the largest Brazilian communities in the UK with over 30,000 Brazilians living across Willesden Green, Kensal Rise, and Harlesden.

London is the city where everything happens and Brazil happens here too. It’s where our music, cinema, and culture thrive, represented with pride by Brazilians and embraced by Britons and people from all over the world who fall in love with our jeitinho, our joy, and our contagious passion for life.

The jeitinho brasileiro or “Brazilian little way” is the art of finding creative, �lexible solutions when rules or systems don’t work. It re�lects Brazilians’ resourcefulness, warmth, and adaptability, o�ten using charm, empathy, or improvisation to solve problems. In short, it’s Brazil’s way of saying: “If there’s no way — we’ll find one.”There’s no better way to understand Brazil than by seeing how it reinvents itself abroad.

Experiencing Brazil in London is, in many ways, an anthropological journey, a chance to witness how our community organises itself, welcomes others, and shares, with open arms and open hearts. That special blend that wherever it goes, continues to captivate the world.

For those missing home or Londoners eager to discover Brazil, I prepared this guide so you can enjoy it as the Brazilian community out there every weekend. Among my favourite spots is Frigideira, a restaurant famous for its feijoada, picanha, and coxinha. Just around the corner, D’Broa Café serves comforting Brazilian snacks and juices, while Açaí Carioca in the same street brings the taste of Rio’s beaches to London.

Frigideira Restaurant – Kensal Rise

Authentic Brazilian food and friendly hospitality make Frigideira one of the most loved restaurants in North London. Expect hearty dishes, live music, and a community vibe that feels like a corner of Rio.

37 Chamberlayne Road, London NW10 3NB

https://frigideira.co.uk

@frigideirauk

A cosy, family-run café serving pão de queijo, sandwiches, and fresh juices (vitaminas). The perfect stop for breakfast or a relaxed weekend brunch.

114 Chamberlayne Road, London NW10 3JP

+44 7955 814019

https://dbroa.co.uk

@dbroacafe

This café celebrates Brazil’s beloved açaí fruit in all its forms, from smoothie bowls to tapioca pancakes. Bright, welcoming, and health-conscious — it’s pure Rio energy in London.

52 Chamberlayne Road, London NW10 3JH

https://acaicarioca.co.uk

@acaicarioca

The UK’s most popular Brazilian rodízio, o�fering endless cuts of grilled meat served tableside — a must for any churrasco lover.

17-19 Sha�tesbury Avenue, London W1D 7ED

https://preto.co.uk

@preto_restaurants

Run by chef Camilla Vargas, Little Piece of Bahia serves authentic Bahian street food acarajé, abará, and moqueca blending

Afro-Brazilian �lavours with a London twist. A Manchester native on weekdays, Camilla brings her soulful cooking to Brick Lane on weekends, honouring her mother’s legacy and generations of women who cooked before her.

223 Mare Street, London E8 3QE

Weekends, 11am–6pm

https://ilittlepieceo�bahia.com

@littlepieceo�bahia

A lively bar-restaurant inspired by Rio’s Lapa district. Live music, caipirinhas, and vibrant décor make this one of the best spots in London for a true Brazilian night out.

12 Inverness Street, Camden, London NW1 7HJ

https://madeinbrasil.co.ukv @madeinbrasilcamden

Unit 14, Boxpark Wembley, London HA9 0JT

https://ipanemalondon.co.uk

@ipanemabbq

A family-run Brazilian BBQ bringing the �lavour of Rio’s street grills to London. Located inside BOXPARK Wembley, it serves smoky picanha, espetinhos, and traditional feijoada in a lively, music-filled setting perfect before a football match or concert.

Born in Brazil’s Northeast, Forró is a partner dance full of warmth and rhythm, accompanied by accordion (sanfona), triangle and zabumba. The name derives from “for all” a dance of togetherness.

Forró Foundations – Tuesdays

Juju’s Bar & Stage – Wednesdays

Pé Descalço & Forró Works – Thursdays

Forró Fridays – Fridays

Forró Family – Saturdays

Forró Academy – Tia Maria Bar & Kitchen – Sundays

Forró de Sexta – Monthly

Forró at the Park -

Samba is Brazil’s heartbeat, a rhythm of resistance and celebration that unites generations. Originating in Bahia and �lourishing in Rio, it embodies the beauty of Afro-Brazilian culture.

Samba de Raiz UK

Samba de Raiz UK is a cultural project that promotes traditional Brazilian samba in London. Events are frequently held at the Maxilla Social Club in Notting Hill, gathering musicians, DJs, and a passionate community of Brazilian music lovers. In addition to samba de roda, the event celebrates other cultural expressions, such as forró and feijoada, creating a warm and authentic atmosphere that feels like home.

Maxilla Social Club, Notting Hill Next edition: 23 November – Black Consciousness Month

@sambaderaizuko�ficial

@forroregents_park

Samba de Bamba UK

Samba de Bamba UK has been one of London’s leading samba events, celebrating Brazilian culture for the past five years. The group hosts regular rodas de samba, bringing the best of Brazil’s music and energy to London audiences. Their events o�ten combine music, dance, and authentic Brazilian cuisine at the Maxilla Social Club.

Maxilla Social Club, Notting Hill Next event: 9 November

@sambadebamba_uk

In London, Brazilians have shared more than food and music; we've shared our essence. We continue transforming nostalgia into innovation and rhythm into community through creativity and connection.

Capoeira is more than a martial art, it's freedom in motion. Created by enslaved Africans in Brazil, it blends fight, acrobatics, and music, representing resistance and resilience.

Capoeira Club Croydon

Capoeira Club Croydon is a women-led project that promotes capoeira as a tool for empowerment and physical and mental well-being. Open to all ages, the group o�fers weekly classes for children and adults, combining rhythm, music, and movement in a truly immersive cultural experience.

https://capoeiraclubcroydon.com

@capoeiraclubcroydon

Senzala London

Senzala London is the London branch of one of the most renowned capoeira groups in the world. Based on the Centro Cultural Senzala de Capoeira, founded by Mestre Peixinho, the collective operates in several areas of London, including Camden and Liverpool Street. The group organises capoeira circles, workshops, and cultural events celebrating Afro-Brazilian heritage through movement, music, and community.

https://senzala-london.co.uk

@senzalalondon

Capoeira Sul da Bahia London

Capoeira Sul da Bahia London is part of the traditional Brazilian school founded by Mestre Railson. With a strong focus on discipline, musicality, and body expression, the project promotes Afro-Brazilian cultural heritage through capoeira, connecting generations and communities across the United Kingdom.

Venue 28, Beckenham Rd, BR3 4LS & St. Philip’s Church, Ealing

@capoeira_suldabahia_london

Neto Brazil founded Rádio Mais Brazil, which broadcasts 24 hours daily, connecting the diaspora through music, culture, and interviews.

https://soundcloud.com/radiomaisbraziluk

@radiomaisbraziluk

No matter how far from home we go, Brazil always finds a way to be present in our lives. From samba schools to sound systems, from feijoada to funk, these are the people and places keeping Brazil’s spirit alive in London.

Brazilian singer-songwriter and producer known for his samba-funk fusion and deep Afro-Brazilian roots. His music has travelled from Rio’s streets to London’s stages, celebrating heritage through groove and soul.

Iuli Caroline Lemos da Silva

Professional samba dancer and educator, founder of the Sambando com Iuli project and co-leader of the Império da Rainha Samba School.

São Paulo-born, London-based dancer, entrepreneur, and samba performer. Founder of DG Events, Danielle produces Brazilian dance workshops, samba shows, and community events. “Art saved me — and I want to use it to inspire others never to give up on their dreams,” she says.

CEO, choreographer, and dancer behind Baile Da Silva, a creative company that celebrates Brazilian movement within the global Latin scene. Her work merges fitness, empowerment, and storytelling through dance.

Santana Antonio Pandeiro

One of the most loved Brazilians in London, where he leads Samba-Reggae drum workshops. With his students, his batucada, Tribo, plays every year at carnival and has become regular at LatinoLife in the Park.

The beating heart of Oi Brasil, which produces spectacular Brazilian shows in London

North London-born, Brazilian-British producer blending Baile Funk, UK bass, and percussive club sounds. With releases on More Time Records, RKS, and XXIII, and sets at Glastonbury and Love Saves The Day, AÆE connects Salvador's beats with Bristol's dance�loors.

Capixaba-born DJ, producer, and composer spreading the essence of Brazilian Funk across Europe. From Espírito Santo to London, Taigo brings funk capixaba to international dance�loors.

Percussionist and bandleader fusing samba, jazz, and Tropicalia. His beloved George Band has played at the EFG London Jazz Festival and Wilderness Festival, while his Jambu Music Jam unites Brazilian musicians across the UK.

@belovedgeorgeband

Singer-songwriter blending MPB, soul, and London jazz. Described by The Independent as “a voice that makes you feel the soul of Brazil,” Raf has performed at Ronnie Scott’s, Somerset House, and BBC Maida Vale Studios.

Brazilian-born, London-based DJ and visual artist known for her genre-�luid sets and commitment to women in music

A London-raised Brazilian rapper fusing Baile Funk, UK rap, and trap. His bilingual lyrics explore the immigrant experience, street life, and resilience — already surpassing 130,000 streams in his first year.