Gregorius Magnus: biannual magazine of Una Voce International

The FIUV’s magazine is dedicated to St Gregory the Great (Pope Gregory I), who died in 604 AD, a Pope forever associated with Gregorian chant and the Gregorian rite of Mass (the Traditional Mass).

Gregorius Magnus magazine aims to be a showcase for the worldwide Traditional Catholic movement: the movement for the restoration to the Church’s altars of the Mass in its traditional forms. We draw features and news from our supporters all over the world, including the magazines published by some of our member associations.

Gregorius Magnus is published twice a year: in March and in October.

The Editor wants to hear from you! We want to spread the news, good or bad, about the movement for the restoration of the Church’s liturgical traditions, from all over the world.

The production of the magazine is supported financially by the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales, and we wish to record our thanks to them.

ʻHe who would climb to a lofty height must go by steps, not leapsʼ.

St Gregory the Great

Please send contributions to secretary@fiuv.org, for our two annual deadlines:

15th February, for the March issue

15th September, for the October issue

FIUV News

President ʼs Message 4

Obituary: Rodolfo-Francisco Vargas Rubio

Una Voce: The Cult of the Sacred Heart

St Mary Margaret and the Apparitions of the Sacred Heart

Dominus Vobiscum: On the Divine Virtue of Hope

The Little Flower: Interview with Fr Angelo Van der Putten, FSSP

How

Features and News from Around the World

The Deep 'Romanitas' and Catholicism behind England's Christian Foundation

Tradition on Display: Rome's Jubilee Doors Open to the Latin Mass by Michael Haynes

The Fall of Adam and Eve: The Ultimate Metaphor of St Francis de Sales by Robert Lazu Kmita

Making Our Appeal to Pope Leo by Joseph Shaw

News from Scotland by Dorothy McLean

A Holiday Experience of the Tridentine Mass in the Diocese of Prato, Italy by Anthony Bailey

Book

The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt by Joseph

Editor: Joseph Shaw

Website: http://www.fiuv.org/ For further queries, please email secretary@fiuv.org Designed by GADS Limited

Gregorius Magnus is published by the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce. The FIUV is a lay movement within the Catholic Church, founded in Rome in 1965 and erected formally in Zürich in January 1967. The principal aims of the FIUV are to ensure that the Missale Romanum promulgated by Pope St John XXIII in 1962 is maintained in the Church as one of the forms of liturgical celebration, to obtain freedom of use for all other Roman liturgical books enshrining ‘previous liturgical and disciplinary forms of the Latin tradition’, and to safeguard and promote the use of Latin, Gregorian chant, and sacred polyphony.

The Council of the International Federation Una Voce, renewed at the 2023 General Assembly

President:

Joseph Shaw (Latin Mass Society, England and Wales)

President d’Honneur: Jacques Dhaussy (Una Voce France)

Vice Presidents:

• Felipe Alanís Suárez (Una Voce México)

• Jack Oostveen (Ecclesia Dei Delft, The Netherlands)

Secretary: Andris Amolins (Una Voce Latvia)

Treasurer:

Monika Rheinschmitt (Pro Missa Tridentina, Germany)

Councillors:

• Patrick Banken (Una Voce France)

• David Reid (Una Voce Canada)

• Jarosław Syrkiewicz (Una Voce Polonia)

• Fabio Marino (Una Voce Italia)

• Rubén Peretó Rivas (Una Voce Argentina)

• Uchenna Okezie (Una Voce Nigeria)

President’s Message

by Joseph Shaw

Welcome to Gregorius Magnus, the edition which coincides with our General Assembly in Rome marking the 60th anniversary of our foundation.

Many reading these words in Rome that weekend will be about to experience, or will have just experienced, the first fruits, from the point of view of the movement for the preservation of the Traditional Mass, of the new pontificate: the celebration of the ancient Mass in the Chapel of the Throne in St Peter’s Basilica, by Raymond Cardinal Burke. At the time I was preparing the last edition, Pope Francis was in his last illness: requiescat in pace.

However much we may have disliked Traditionis Custodes, we should not forget that Pope Francis also helped us –making provision for the marking of the feasts of newly canonised saints, giving the Society of St Pius X authorisation to hear confessions, and giving the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest the use of a basilica in Rome. Finally, he refused to countenance what appears to have been a final attempt to crush the Traditional Mass. In the famous words of Thomas Grey’s ‘Elegy’:

No farther seek his merits to disclose, Or draw his frailties from their dread abode, (There they alike in trembling hope repose) The bosom of his Father and his God.

Now we address ourselves to Pope Leo, with simple and filial confidence. I have written a feature in this edition explaining my own optimism. To take a different approach to the question, we might ask: given the typical assumptions and habits of mind of the higher clergy, and of lay Catholic opinion-formers, what would a normal, ‘establishment’ view of us and our aspirations be?

First and foremost, we are a group of Catholics with pastoral needs, like everyone else. We are fortunate that there has always been an important number of priests and bishops, and popes as well, who understand the pastoral stakes: the real harm that would be done by stopping the

celebration of the Traditional Mass completely. At first, the pastoral harm that concerned the ecclesial establishment was naturally to the older generation. Later, as this generation was thinned out by the passage of time, the people attached to the Traditional Mass must have appeared to them like a band of eccentrics: for the most part, I think, harmless eccentrics. Since 1988, and even more so since 2007, many of them have come to see that the Traditional Mass sustains the spiritual lives of many young people and young families: indeed, it not only sustains them but also facilitates family formation and vocations to the priesthood and the religious life. At the same time, the number of marriages and vocations in the Church as a whole is falling to worryingly low levels, to such an extent that our movement, small as it is, begins to look significant.

One possible reaction to this is anger: that somehow those traditionalists have stolen some of the energy and life

that ought by rights to be animating the structures of what we must call the ‘mainstream Church’. A more mature judgement would be that the ancient Mass, the Church’s traditional spirituality, and her artistic patrimony constitute resources that it would be foolish to squander.

This more positive assessment is not yet universal in the hierarchy and among lay commentators, but it is becoming an obvious one. Those who refuse to see things in this way should be challenged. Perhaps things have developed in an unexpected way; perhaps the Holy Spirit hasn’t worked quite as you would have preferred. But what are you going to do about it? Will you tell these young people, who want to worship as their predecessors worshipped for many centuries, that they are not welcome? Or, at a moment when the Church is threatened from within and from without in so many ways, will you grant them the right to exist, where they may even do some good?

Become a Friend

of the Una Voce Federation

Becoming a Friend is an easy way to support the work of the Federation for the ‘former Missal’ of the Roman Rite, and to keep yourself informed about its activities.

You can become a Friend by e-mailing your name and country of residence to treasurer@fiuv.org and making an annual donation according to your means: all are welcome. This can be sent by PayPal to the same email address, or using the bank details below.

You will be included on the mailing list for publications and regular bulletins, but your details will not be shared with others.

Two Traditional Masses are offered each month, one for living and one for deceased Friends.

Bank details:

IBAN: DE21600501010001507155

BIC/SWIFT: SOLADEST600

Bank: BW-Bank Stuttgart

Account Owner: Monika Rheinschmitt

'It is vitally important that these new priests and religious, these new young people with ardent hearts, should find—if only in a corner of the rambling mansion of the Church— the treasure of a truly sacred liturgy still glowing softly in the night. And it is our task—since we have been given the grace to appreciate the value of this heritage—to preserve it from spoliation, from becoming buried out of sight, despised and therefore lost forever. It is our duty to keep it alive: by our own loving attachment, by our support for the priests who make it shine in our churches, by our apostolate at all levels of persuasion...'

Dr Eric de Saventhem, founding President of the Una Voce Federation, New York, 1970

Obituary: Rodolfo-Francisco Vargas Rubio, 1958-2025 FIUV Secretary, 2007-11

by Leo Darroch

Rodolfo-Francisco Vargas Rubio was born in Lima, Peru, on 23rd November 1958. He was also known as Francisco de Morandé, from the surname of one of his ancestors. He studied at the Jesuit school of Lima, the Colegio de la Immaculada, where he was a student of the great apostle of devotion to the Sacred Heart, Fr Florentino Alcañiz García. When he was a young pupil of the Jesuits, his patron was St Stanislaus Kostka, a young Polish boy who was educated by the Jesuits and died in Rome in 1568 at the age of 17 on the Feast of the Assumption. St Stanislaus is the patron saint of novices, youth, young students, and seminarians. On leaving the Colegio de la Immaculada, Rodolfo studied Law and Political Science at the University of Lima.

He entered the seminary at Écône, Switzerland, and received the clerical tonsure from Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, but while visiting home in Peru, he broke his leg and neglected to tell his superiors that he would be late returning, and so was asked to leave. He then spent some time studying philosophy at the diocesan seminary of Cuenca (Spain); in Rome, he studied at the International Seminary Mater Ecclesiæ, a seminary built by then Cardinal Ratzinger for Traditional seminarians, and later studied for a bachelor’s degree in Sacred Theology at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (Angelicum), as a seminarian for the Diocese of Venice in Florida, USA. He was subsequently accepted at the Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest in Gricigliano, Italy. This, however, was cut short by health problems, when he suffered a stroke. It was his poor health throughout his life that prevented him from being ordained.

When Rodolfo was studying in Rome, he spent all his time in his room reading. When exams came around, his great friend Mgr Apeles one day asked him if he had already taken the oral exam for a subject, and he didn’t even know he was enrolled for it. He went straight to the exam and obtained the highest grade. He was extremely well educated in all theological and historical subjects, but quite incapable of conforming to administrative norms. His character was very free-spirited, and he never managed to stay very long in one place: it could be said that he had little sense of reality.

In Spain, he studied history at the National University of Education, the largest university in Spain. He also studied law, political science, theology, and geography. He moved to Barcelona, since his mother was Spanish, and he was able to settle there. With the encouragement of Michael Davies, he founded the Roma Aeterna association to establish an Una Voce presence in Spain, and the association was welcomed into the International Federation in November 1997.

He tutored numerous students and worked as a lecturer and historian for Áltera Publishing House. He was commissioned to write several articles for the Spanish Biographical Dictionary of the Royal Academy of History. In 2005, he published TheLastPope?BenedictXVI and His Time: A Biographical Profile of Pope Ratzinger, and was delighted to be able to present a copy personally to Pope Benedict XVI during an audience in 2009.

Rodolfo was indefatigable in pursuing the cause of the traditions of the Church. He was the founder of the International Committee for the Exaltation of Benedict XIII (Papa Luna), and of the Sodalitium Pastor Angelicus in 1998, an association of laypeople that aims to disseminate knowledge of the life and work of Pope Pius XII and to advance the cause of his beatification and canonisation. Rodolfo was born in 1958, the year that Pope Pius XII died, and he commented that the more he read about this wonderful Pope, the more he regretted that he had not been born 30 years earlier. He was delighted when, on 21st December 2009, Pope Benedict XVI conferred the title of Venerable on Pope Pius XII.

Rodolfo was also a Knight of the Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George, a dynastic order of the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, recognised by the Holy See and several states, including Spain and Italy. At the invitation of Michael Davies, he would wear the cape of the order while attending Masses in Rome during the FIUV assemblies. Rodolfo also had an attachment to the cause of the French monarchy.

At the FIUV General Assembly in Rome in 2007, he reported that the situation in Spain had improved remarkably. In 2005, the only member association in Spain was Roma Aeterna, but since then two more have been established: Una Voce Seville and Una

Voce Madrid. A Spanish chapter, Una Voce Hispania, was constituted for admitting new associations in future. It was in 2007 that Rodolfo was elected to the FIUV Council and accepted the office of Secretary, a post he held for four years. He was extremely effective in this role, especially on visits to Rome for meetings with the Ecclesia Dei Commission and the various Roman Congregations, where his facility with languages was particularly helpful.

At the 19th General Assembly in Rome in 2009, the Federation was, for the first time, granted permission for a Traditional Latin Mass in the upper Basilica of St Peter: previously, we had had to be content with Mass in the Crypt. It was celebrated in the Chapel of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary in the Temple. The altar is the final resting place of St Pius X. Rodolfo had arranged for the celebrant, Mgr Pablo Colino Paulis, former Chapel Master of the Basilica and Director of the Capella Giuli Choir, whom he knew from his time studying music in Rome. Although it was intended to be a Low Mass, Monsignor turned to the delegates at the Kyrie and suggested that they sing – which we did with gusto. It was probably the first time a sung Latin Traditional Mass had been sung in the Basilica since 1970, and it attracted a number of visitors who came over to join the delegates.

In 2009, Rodolfo’s links with the Spanish-speaking countries of Central and South America proved of great value when he was contacted by associations in Mexico, Chile, Colombia, and Peru, which became members of the Federation. The following year, he was instrumental in welcoming groups from Cuba, Argentina, Honduras, and Portugal, and taking inquiries from Panama and Puerto Rico.

He had always suffered poor health and seemed to spend his entire life going from doctor to doctor and from hospital to hospital. From 2011, his problems grew worse, and it was for health reasons that he stood down from his role of Secretary. In all these troubles, his faith never wavered and he was more concerned for others. He worried about his ‘beloved Peru’ being ‘under attack from communist and terrorist forces with complicity of Latin-American red dictatorships and socialist governments’. He prayed that ‘Our Lady and Saint Rose of Lima have mercy on my other homeland’.

On 8th May 2024, because of failing health, he moved to Valencia to live initially with his brother while he convalesced; later, he rented a small house in Sueca, his mother’s birthplace. Unfortunately, he found that the nearest Traditional Latin Mass was in Valencia, some 22 miles away, and he was too infirm to travel. He thanked God that the parishes kept ‘a decent Eucharistic worship and the celebrations were quite correct’. He was also consoled that the local churches were beautiful and very traditional.

He died on 31st August 2025 and his funeral Mass was celebrated at the Church of Our Lady of Carmen, Sueca. He is buried in the Sueca cemetery. The International Federation Una Voce has many reasons to be thankful for the presence and devoted service of Rodolfo Vargas Rubio, and we mourn his passing.

Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine: et lux perpetua luceat ei. Requiescat in pace.

– Leo Darroch. With appreciation to Alfonso Vargas Rubio and Monsignor Jose-Apeles Santolaria de Puey y Cruells for important contributions.

Una Voce is the magazine of Una Voce France

From Una Voce, the magazine of Una Voce France, number 352, June-August 2025

This edition devotes a series of articles to the cult of the Sacred Heart, in this 350th anniversary year of the apparitions of St Margaret Mary at Paray-le-Monial.

The Cult of the Sacred Heart Today

by Anne-Marie Epitalon

This jubilee year of the apparitions of the Sacred Heart to St Margaret Mary at Paray-le-Monial reminds us of the importance of this devotion, which is too often wrongly associated with a sentimental spirituality. The Sacred Heart is the fleshly heart of Our Lord. Throughout history, the heart has been the symbol of love. The Sacred Heart symbolizes Jesus’ human love for His Father and for us, as well as the divine love for us, since humanity is united with divinity in Jesus. The entire history of salvation is explained by God’s infinite love for mankind. This is why Pope Pius XII wrote on 15th May 1956: ‘The devotion to the Sacred Heart is not just any form of piety that one could underestimate, but the perfect expression of the Christian religion’. It is true that until the seventeenth century there was no developed doctrine on the Sacred Heart, but merely a simple presence of the Heart of Jesus in the

lives of Christians. The source of this devotion is found in the Gospels, when the Heart of Jesus was pierced by the soldier’s lance: ‘Then when he came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, he did not break his legs. But one of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and immediately blood and water came out’ (Jn 19:33-34).

Even though the early Christians did not explicitly venerate the Sacred Heart of Jesus, they recognised the immensity of God’s love and Christ’s love for humanity. However, from the very first centuries, the Church Fathers looked at the wound in Christ’s side and saw the Church being born from it. This devotion would be relayed and spread by numerous saints: in the eleventh century, St Bernard; in the thirteenth century, the Benedictines St Mechtilde and St Gertrude, who loved to contemplate the Heart of their Master with a joyful piety; in the fourteenth century, St Catherine of Siena; in the sixteenth century, St Teresa of Avila; and in the seventeenth century, St John Eudes, who introduced this devotion into the liturgy. During the same period, when the Christian faith was shaken by Protestantism and Jansenism, and when piety had waned, it was through St Margaret Mary that Jesus chose to

manifest the riches of His Heart. This devotion has continued to spread to this day, and bears many fruits of conversion.

The jubilee year of the apparitions at Paray has reminded us of the importance of this devotion for today’s Christians, particularly through Pope Francis’ encyclical on the Sacred Heart, Dilexit nos (2024), 214: ‘The wounded side of Christ continues to pour forth that stream which is never exhausted, never passes away, but offers itself time and time again to all those who wish to love as he did’.

More recently, our new Pope Leo XIV addressed the Conference of Bishops of France in May 2025, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the canonisation of St John Eudes, St JohnMarie Vianney, and St Thérèse of the Child Jesus, to reaffirm the necessity of drawing from this source of life and charity in order to awaken hope and inspire a new missionary fervour among Catholics. Leo XIV reminds us that these three saints drew their strength to fulfil their mission from the love of the Heart of Jesus: ‘Is not St John Eudes the first to have celebrated the liturgical worship of the Hearts of Jesus and Mary? Is not St John-Marie Vianney the passionately devoted priest who asserted, “The

priesthood is the love of the Heart of Jesus”? And finally, is not St Thérèse of the Child Jesus the great Doctor in the Science of Love that our world so desperately needs? ... God can, with the help of the saints He has given you, and whom you celebrate, renew the wonders He has accomplished in the past’.

Let us not hesitate today to dedicate ourselves to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, to draw the necessary graces to persevere in Faith, Hope, and Charity, which are essential for the new missionary impetus to which the Pope invites us. ‘Sacred Heart of Jesus, I trust in You; Sacred Heart of Jesus, make my heart like unto Thine; Sacred Heart of Jesus, reign over France!’

Testimony of pilgrims – Jubilee pilgrimage to Paray-le-Monial

At the shrine of the Sacred Heart of Paray-le-Monial in Burgundy, a jubilee was celebrated from 27th December 2023 to 27th June 2025, to commemorate the 350th anniversary of the apparitions of Jesus to St Margaret Mary. This jubilee provided a special opportunity to undertake a pilgrimage to the Chapel of the Apparitions at the Monastery of the Visitation.

In the seventeenth century, Christ revealed His Heart to Sister Margaret Mary, a nun of the Order of the Visitation in Paray-le-Monial, which is now part of the Saône-et-Loire department in the Diocese of Autun. The three principal apparitions took place on 27th December 1673, on the first Friday of a month in 1674, and in June 1675.

The message has three dimensions: Jesus reveals His Heart, which has loved the world so greatly, filled with passionate love for all mankind; He laments receiving only ingratitude and indifference in return; and He asks for reparation for this lack of love, notably through the establishment of a feast to honour His Divine Heart. Thus, returning love for love means welcoming Jesus’ personal love for each of us, repairing the lack of love that He endures, and entering into the compassion of His Heart for those who are in great need of consolation. A jubilee approach is an invitation to begin a journey to respond to Jesus’ call: ‘Come to me, all you who are weary and heavy laden, and I will give you rest, for I am gentle and humble in heart’ (Mt 11:28). Passing through the jubilee door is to enter into the Heart of Jesus to be profoundly renewed in our baptised lives and to give Him love for love.

St Margaret Mary and the Apparitions of the Sacred Heart

by Catherine Bosson

Jesus loves to entrust great treasures to humble creatures, fragile and even ignorant. Our saint from Paray-leMonial is one of those humble beings to whom Jesus revealed the fervour of His love. We shall delve into the significant events of her existence, then pause to consider the main ‘revelations’ that Jesus imparted to our saint, and finally we will outline how we can respond to this message of the Sacred Heart.

Historical context

St Margaret Mary was the daughter of Philiberte and Claude Alacoque, a royal judge and notary in Charolais, Burgundy. They already had three sons when, on 22nd July 1647, a girl was born, who was given the name Margaret at her baptism, three days after her birth.

At that time in France, the reign of Louis XIII (1601-43) came to an end and the Regency of his wife, Queen Anne of Austria, began, and continued

until 1651. The long-awaited heir to the crown, Louis XIV, was born in 1638, after twenty-three years of his parents’ childless marriage. This long-awaited birth was the result of the intercession requested by Brother Fiacre before Our Lady of Graces, to whom the religious performed three novenas of prayer to obtain ‘an heir for the crown of France’. In gratitude to the Virgin for this unborn child, the king signed the Vow of Louis XIII, dedicating the kingdom of France

to the Virgin Mary and making 15th August a public holiday throughout the kingdom. In 1660, Louis XIV and his mother would go in person to Cotignac to pray and thank the Virgin.

At the age of four or five, Margaret spent an extended stay with her godmother, Madame de Fautrières. For the first time, she heard about a life dedicated to God and religious vows, since Marie-Bénigne de Fautrières, her godmother’s daughter, was a nun at the Visitation of Ste-Marie in Parayle-Monial. The little girl felt a constant urge to say and repeat these words: ‘O my God, I consecrate my purity to Thee, I make a vow of perpetual chastity’. One day, she uttered this formula during the two elevations of the Mass. These words acquired such significance in her eyes that she recalled them, twenty years later, as having marked her life.

After the early death of her father (in 1655, when Margaret was only eight years old), Madame Alacoque had to face serious material concerns and could no longer care for her children, who went to boarding school. Margaret was sent to school at the Clarisses of Charolles. Everywhere, her fervour and love for the Most Holy Virgin were noticed. Every day, she recited the rosary with extraordinary devotion. However, a long illness interrupted her studies when she was eleven years old, and forced her to leave the convent of Charolles. She remained paralyzed in her bed for four years. The child then promised Mary that she would one day become a nun if she recovered her health. ‘As soon as I made this vow’, Margaret would say, ‘I received healing’. This miracle inspired a new surge of Marian piety in her heart: ‘The Holy Virgin’, she tells us, ‘then became the mistress of my heart ... She governed me as being dedicated to her, corrected me for my faults, and taught me to do the will of God’.

Upon her recovery, Margaret and her mother were compelled to leave their home and take refuge with the paternal grandmother, who was also joined by an aunt and the latter’s motherin-law. The three of them claimed absolute rights over Margaret and her mother. Margaret was treated worse than the servants, who themselves were mistreated by these terrible women. However, Our Lord comforted her and made her understand that He

had chosen her to share in His painful Passion: ‘I wish to make Myself present to your soul to enable you to act as I have acted in the midst of the cruel sufferings endured out of love for you’. Margaret would later say: ‘One must often delight the adorable Heart of Jesus with this dish so delightful to His taste, I mean the precious humiliations, contempt, and abjections with which He nourishes His most faithful friends here below’.

When Margaret was eighteen years old, her relatives, particularly her mother, considered arranging her marriage. The young girl enjoyed worldly celebrations, and this influenced her calling. Finally, after six years of struggle, she decisively chose to enter religious life. On 26th May 1671, she went to the Visitation of Ste-Marie at Paray-le-Monial. As soon as she entered the parlour, an inner voice assured her: ‘This is where I want you’. A month later, she entered this monastery for good. On 25th August of the same year, Margaret received the religious habit and added the name of Mary to her baptismal name. On 6th November 1672, she made her vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. She was assigned the role of caregiver at the infirmary.

From December 1673, shortly after her first vows, Margaret Mary began to receive revelations from Jesus regarding the Sacred Heart. A long path of suffering opened up for her, as her superior and the other sisters took her for a madwoman, subjecting her to terrible humiliations and vexations. However, from 1675 to 1678, a Jesuit priest, Claude La Colombière (who has been beatified), was appointed to Paray-le-Monial, and he was able to soothe her and make her understand that they were both called to the same mission: to better make known God’s love for His children.

Margaret Mary completely yielded to Jesus as He had requested of her, and she was appointed mistress of novices until 1686. Her novices admired her and quickly became attached to her; to celebrate St Margaret, they organized a surprise in the novitiate hall and created a large pencil drawing representing the Sacred Heart. The novices took turns all day reflecting in front of this image, represented for the first time. Gradually, devotion to the Sacred Heart developed within the convent, and one day in the refectory, a message by Father La

Colombière, now deceased, was read, in which he recounted the requests made by the Heart of Jesus. In the monastery, a chapel dedicated to the Sacred Heart was completed in 1688. Margaret Mary continued to write down the promises that Jesus revealed to her, but she sensed that He would soon call her to Himself. She passed away on 17th October 1690, at the age of fortythree. (She was beatified in 1864 and canonized in 1920.)

The revelations of the Sacred Heart

On 27th December 1673, during the feast of St John the Evangelist, Margaret Mary was in the chapel. Jesus ‘made her rest long on His divine breast, where He revealed to her the wonders of His love and the inexplicable secrets of His Sacred Heart, which He had until then hidden from her’. Jesus also said to her: ‘My Divine Heart is so passionate in love for men, and for you in particular, that, unable to contain the flames of this ardent charity any longer, I must pour them out ... it is you I have chosen’.

From this day forward, Margaret Mary received the stigma of the wound of the lance inflicted on Jesus on the cross at her side. Jesus asked her to receive Holy Communion every first Friday of the month, and to unite with His agony in the Garden of Olives from 11 p.m. to midnight every Thursday, through a ‘holy hour’ of prayer and suffering in atonement for the sins of the world. Then Jesus requested that ‘a special feast be established to honour this love of my Heart for mankind, on the Friday following the week during which Corpus Christi is solemnized’.

Then the saint had other revelations, which she took care to note at the request of her confessors. Among the promises of devotion to the Sacred Heart, we can mention:

1 That all those who will be devoted and consecrated to Him will never perish

2 That, as He is the source of all blessings, He will abundantly pour them out in all places where the image of his Divine Heart will be set and honoured

3 That He will reunite divided families and protect and assist those who are in any need and who address themselves to Him with confidence

4 That He will pour the sweet anointing of His ardent charity upon all communities that honour Him and place themselves under His special protection

5 That He will divert all blows of divine justice from them to restore them to grace when they fall

The fifth promise concerns the apostles of the cult of the Sacred Heart: ‘My divine Master made me understand that those who work for the salvation of souls will work successfully and will have the art of touching the most hardened hearts, if they have a tender devotion to His Sacred Heart, and if they work to inspire and establish it everywhere’.

Then in 1675, there came what is called the ‘great promise’. The feast of Corpus Christi had just been celebrated and Margaret Mary remained as much as possible in adoration before the Blessed Sacrament. Pointing to his heart, Jesus said to her: ‘Behold this Heart that has loved men so much that it spared nothing, even exhausting and consuming itself to bear witness to its love; and instead of gratitude, I receive from most only ingratitude, indifference, and even contempt in this sacrament [the Eucharist]. But I suffer even more when it is consecrated souls who act this way’. He added: ‘I promise you, in the excessive mercy of my Heart, that my all-powerful love will grant to all those who receive communion on the nine first Fridays of the month in succession, my grace of final penitence, not dying in my disgrace and without receiving their sacraments, my Divine Heart becoming a sure refuge at the last moment’.

In what ways can we respond to the requests of the Sacred Heart?

‘If you only knew’, Jesus said to Sister Margaret Mary, ‘how much I thirst to be loved by men, you would spare nothing: “I thirst, I burn with desire to be loved!”’ The love of Christ compels us, says St Paul (2 Corinthians 5:14); it especially compels us to return love for love.

A privileged means of manifesting our love for Jesus is to honour Him in the Most Holy Eucharist. ‘I have a burning thirst’, Jesus confided to our saint, ‘to be honoured and loved by men in the Most Blessed Sacrament, and I find almost no one who strives, according to my desire, to quench my thirst by

making some return to me’. Our Lord particularly desires that Christians receive Him in Holy Communion in a spirit of reparation, offering to the Eternal Father His Heart, truly present under the Eucharistic species.

We understand what a devotion to the Sacred Heart will consist in. Does God love us? The devotion to the Sacred Heart makes us love Him in return. Are men ungrateful? The devotion will consist of loving Him greatly to repair, comfort, and make reparation. Pope Pius XI, in his encyclical Miserentissimus Redemptor of 8th May 1928, on the Sacred Heart, wrote: ‘The creature must offer, regarding uncreated love, a compensation for the indifference, forgetfulness, offences, outrages, and insults it endures: this is what is commonly called the duty of reparation’. The Pope says this consolation is mysterious but very real. And he quotes the words of Scripture that are put on the lips of Our Lord: ‘I looked for someone to grieve with me, but no one came; I looked for someone to comfort me, but I found no one’ (Ps 68:21).

To concretely repair the ingratitude of man towards the Sacred Heart, the Pope recalled the devotion of the first Fridays of the month, which consists of making a reparative communion. St Margaret Mary explains: ‘My Divine Saviour commanded me to receive communion on the first Fridays of each month, to repair, as much as possible, the outrages He has suffered throughout the month in the Most Holy Sacrament’. The saint often experienced the power of reparative communion

herself to soften the Sacred Heart of Jesus. In order to make such a communion, it is advisable to confess within eight days before or after it.

Always with the aim of making reparations, we can also attend the Holy Hour before the exposed Blessed Sacrament. Our Lord said to his apostles in the Garden of Olives: ‘So, could you not stay awake one hour with me?’ (Mt 26:40). May our presence before the altar allow us to respond affirmatively. To console the Sacred Heart, we can also strive to practise fraternal charity, which Our Lord has elaborated on. Finally, a great means of comforting Our Lord is found in the enthronement of the Sacred Heart in families. Father Matéo, from the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, to whom we owe this practice, declares: ‘It can be stated, in all truth, that in opposition to the campaign of social apostasy, enthronement is a true act of reparation’.

The enthronement in families is an official and social recognition that the king of the family is the Sacred Heart. This recognition is made visible by the solemn installation of the image of the Sacred Heart in a place of honour. It is also made lasting by an act of consecration of the family to the Sacred Heart.

He also invites us to pray as a family before his image: ‘There is the Eucharistic tabernacle, there must be the family tabernacle. If you need a God to worship in a temple, you also need a God to pray to in your homes’. The Cult of the Sacred Heart, although it had been initiated well before St Margaret Mary, saw tremendous growth after her death; it is hard to count the publications, confraternities, and orders that placed themselves under its protection and spread its devotion across all continents. St Margaret Mary would have wanted Louis XIV to consecrate his kingdom to the Sacred Heart; he did not, and France paid a heavy price. However, in July 1873, the National Assembly voted for a law to build what is called the basilica of the National Vow, the basilica of the Sacred Heart in Montmartre, where Adoration is perpetual.

Finally, in 1899, Pope Leo XIII made the consecration of mankind to the Sacred Heart an official act of the Church. On the feast of Christ the King, in front of the exposed Blessed Sacrament, one can renew this act of consecration.

Dominus Vobiscum is the magazine of Pro Missa Tridentina Germany

The following contribution is the slightly revised manuscript of the lecture given at the Pro Missa Tridentina General Assembly on 10th May 2025 in Frankfurt. This is a shortened translation for Gregorius Magnus.

On the Divine Virtue of Hope

by Dr Sebastian Ostritsch

What is hope? A first approach

What does it actually mean to hope? In a common usage of the term, ‘to hope’ is merely a synonym for ‘to wish’. When someone starts a message with the words ‘I hope you are doing well’, they are articulating a wish: essentially, ‘I do not know how you are, but I would be pleased if you were doing well’.

As Josef Pieper noted in his essay ‘On Faith’, the proper and unique meaning of a word becomes clear where it cannot be replaced by another without changing the meaning of the sentence.1 In the case of hope, to hope for something is to orient oneself with full confidence towards that thing in the future. However, there is more to Christian hope, which – like charity and faith – is

a ‘theological’ or ‘divine’ virtue. Both the concept of virtue and the adjective ‘divine’ (or ‘theological’) require further explanation.

What is virtue?

The best and primary reference point for clarifying the concept of virtue is and remains the ethics of Aristotle. It is the questionable intellectual legacy of the Enlightenment and Immanuel Kant that we equate the concept of morality – where we take it seriously at all –with an unconditional duty; a duty that does not concern itself with whether it contributes to our personal happiness or not. In contrast, Aristotle’s virtue ethics begins with the question of the highest good for man, eudaimonia. The common translation of eudaimonia as ‘happiness’ is, however, only partially correct. For it involves, contrary to what the English word may suggest, something more than a mere feeling.

For feelings are fleeting, but the highest good of man must be something enduring. Eudaimonia refers to the good, flourishing life as a whole. However, what constitutes a good, flourishing life cannot be discussed with regard to humanity without first understanding what man essentially is.

As a living being, man possesses a physical, sensory side, which he shares

partially with plants and partially with animals. However, what distinguishes man from plants and animals, thereby marking him as a human being, is that he possesses a rational soul. A rational person is so in two respects. On one hand, he is capable of shaping his natural strivings, his affections, desires, and passions, in accordance with reason. On the other hand, humans possess intellectual or cognitive abilities. In other words, man can think and reflect. This dual aspect of rationality makes humans human. Therefore, an individual leads the life most suited to him when he realizes this rational nature in the most excellent manner possible. In doing so, a person expresses in every respect what he fundamentally is, namely, an animal rationale, a rational being.

With the term ‘excellence’, we are already touching upon virtue. For the Greek word aretē, which we translate as ‘virtue’, fundamentally means ‘excellence’. Therefore, the virtuous person is nothing other than an excellent person, one who embodies what it means to be human in an outstanding way. But what does it concretely mean to be virtuous? Virtues come in two forms, corresponding to the two ways the soul is rational. The so-called intellectual virtues pertain to excellence in reasoning and thinking, while ethical virtues relate to the rational handling

of our passions (such as fear, for example). To be virtuous, in this latter case, means to find the right balance in dealing with them.

This balance is not an absolute, quasi-arithmetic average. Instead, it concerns the golden mean between two destructive extremes, that of too much and too little. In the example of fear, this means: Those who know how to find and maintain the right measure in dealing with a frightening situation are courageous. In contrast, an excess of fear is cowardice, while a lack of appropriate fear is foolhardiness – and both excess and defect are considered vices rather than virtues. What is cowardly, foolhardy, or courageous depends on the specific circumstances, including the nature of the actor: A well-trained police officer who fails to confront a perpetrator will incur accusations of cowardice, whereas an unsuspecting layperson who runs into a burning house that has been cordoned off by the fire service is acting foolhardily.

However, being virtuous is not merely about hitting the right mean occasionally. Rather, virtue requires a virtuous character or habit (habitus), which enables a person to consistently strike the right mean in a stable manner. Therefore, virtue ethics is less concerned with merely doing the right thing and more focused on ‘the rightness of the person’, as articulated by Josef Pieper.2 We refer to someone as virtuous only when the virtues have become second nature to him, when they have been ingrained in his very being.

Is worldly hope a virtue?

Against the backdrop of this brief virtue-ethical sketch, we can now turn to the question of whether natural (that is, not theological) hope can indeed be considered a virtue. First, let us ask whether natural hope can be conceived as a mean between two extremes. One can certainly affirm this. For there is both an excess and a deficiency of hope. Those who have too much hope are naïve, out-of-touch optimists. They will inevitably fall flat on their faces with this attitude. After all, there are situations where scepticism towards fellow humans, societal institutions, or oneself is warranted.

On the other hand, those who have too little hope will close themselves off from their fellow human beings.

Their lack of hope that the world could treat them well will prevent them from seizing the opportunities that arise.

But what does the right measure of worldly hope look like? Natural hope, as a middle ground between naïve optimism and bitter pessimism, should be such that one expects bad things yet can still accept that bad as part of a life worthy of affirmation. But this cannot be considered a moral virtue, because it is not necessarily oriented towards something good.3 A bank robber may be filled with hope of getting away with his crime, yet the objectively good outcome – even for him – would be that this hope is not realised. As Josef Pieper comments: ‘Hope can, in the natural realm, also turn towards the objectively evil, without thereby ceasing to be truly hope’.4

The supernatural virtue of hope

Whereas natural hope is directed towards earthly things, theological hope pertains to God. More precisely, according to Aquinas, it is directed towards being with God, towards the vision of God, inasmuch as it entails eternal happiness (beatitudo aeterna).5 Since God is not only good but Goodness itself, the hope directed towards Him cannot be morally misguided like secular hope. Therefore, supernatural hope fulfils the requirement of virtue,

which is to always be directed towards the objective good. In order for us to truly speak of a virtue, the confident orientation towards God must not be a one-time act. Virtues are, after all, stable character traits. Thus, the supernatural virtue of hope must involve a stable attitude, consisting in the confidence of attaining eternal happiness with God.

The theological virtues – faith, charity, and hope – possess certain particularities in comparison with the ordinary moral virtues. One notable characteristic is the manner in which they are acquired. While moral virtues are developed through moral education, ethical training, and ultimately through habituation, the divine virtues cannot be acquired through natural means. Rather, they are gifts of grace from God, infused into the soul of man by Him.

The theological virtues are not, in the same manner, a mean between extremes as the moral virtues are. For while there can be an excess of fear or courage, there is no excess of supernatural hope: we cannot

1. See Josef Pieper, Über den Glauben [On faith] (Freiburg: Johannes Verlag, 2010), ch. 1, 13–28.

2. Josef Pieper, Das Viergespann [The cardinal virtues], 6th ed. (München: Kösel, 1991), 9.

3. See Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae (ST) I-II, q. 55, a. 3.

4. Josef Pieper, Über die Hoffnung [On hope], 3rd ed. (Freiburg: Johannes Verlag, 2022), 27.

5. See ST II-II, q. 17, a. 2.

believe, love, and hope too much. However, what this hope refers to is solely God’s assistance – for we can never overestimate this. What we can certainly overestimate, though, is our own contribution to the hoped-for state of being with God. Only in this sense can there be both an excess of hope – that is, presumptuousness (praesumptio) – and a lack of hope – which is despair (desperatio).

The presumptuous individual is certain of his eternal salvation, completely independent of whether and how he accepts God’s grace. One of the clearest expressions of this presumption might consist in living with the false certainty that hell is, under all circumstances, empty. As Pieper has shown, presumption can take two forms. The first is, in a sense, Pelagian in nature and is based on the misconception that a person can achieve his salvation through righteous deeds. For Pieper, this is the expression of a ‘typically liberal-bourgeois moralism’, which holds the belief that ‘a “decent” and “orderly” person, who “does his duty”, will – solely based on his personal moral performance – also “be declared righteous before God”.’6 The other, opposing form of presumption lies in the heresy that the free acceptance of and consent to God’s gift of grace plays no role in the process of salvation.7

The despairing person, on the other hand, suffers from the opposite deception. He believes his own corruption to be so great that God could not possibly atone for it through His grace. To live in this despair is, according to a saying of Isidore of Seville, to ‘descend into hell’.8 According to Aquinas, it is the damned who live forever in hopelessness. Thus, it is part of the ‘unfortunate condition of the damned that they are aware that they can escape damnation in no way and cannot attain bliss’.9 Or to embellish an image made known by C.S. Lewis: the damned have not only locked hell from the inside but they have also thrown away the key. One can better understand the sin of despair when one considers its two roots with the help of St Thomas Aquinas.10

On the one hand, despair can be a consequence of hedonism (luxuria). The hedonist may derive such pleasure from worldly sensory delights that he even loses the desire for supernatural happiness, i.e., for eternal life in communion with God. In this case, despair manifests itself in the form of a person who says: ‘Life here on earth is so beautiful and fulfilling that I feel no longing for eternity’. The second possibility of how despair can arise is lethargy (acedia). This vice is more than mere laziness or sluggishness. Aquinas defines it as tristitia quaedam deiectiva spiritus, as ‘a kind of sadness that casts down the spirit’.11 The difficult-to-attain

goal of eternal life seems unattainable to the man subject to acedia – and neither man nor God can seemingly change that.

At the same time, despair is paradoxically not only a religious sin but above all a decidedly Christian sin. Or perhaps better said: in the despair that only a Christian can fall into, there is expressed a spiritual-religious depth that transcends everything one could associate with the despair of a pagan person. This is because despair is the sinful mirror image of the supernatural virtue of hope, which envisions for humans an infinite, allencompassing future happiness. ‘For the same lightning that reveals to us the reality of supernatural grace’, as Pieper states, ‘also illuminates the abyss of creaturely estrangement from God and sin’.12

Even though they may be accompanied by emotional or mood-related hues, hope, despair, and presumption are not, in truth, emotions or affections but acts of will, movements of will. This point may initially sound purely theoretical, but it also has practical relevance. First, regarding the theory: Aquinas distinguishes between different faculties of the human soul. One of these is the appetite, which is directed towards the good or what is perceived as good. The appetite is further divided into a sensual and an intellectual part. The sensual striving faculty is accompanied by passions: here, fear, anger, sorrow, and so forth come into play. The intellectual appetite, on the other hand, is the will –and it is independent of the affections. Hope, insofar as it is directed towards an invisible, immaterial, supersensible God, cannot possibly be assigned to sensual appetite but only to the intellectual – that is to say, to the will. The same holds true for the aberrations of hope: presumption and despair.

So much for the theory. It is practically relevant because it follows from it that despair is not something one ‘falls into’, as Pieper writes, ‘but rather something that one commits to’. Thus, there is freedom at play! The same is of course true in the case of presumption and hope. With hope, it can only be considered a virtue – even if it is one infused by God – because it involves an act of free will on the part of the individual. Conversely, despair and presumption are sins precisely insofar as individuals freely consent to them.

6. Pieper, Über die Hoffnung, 70.

7. Ibid., 7.

8. Quoted by Pieper, Über die Hoffnung, 49.

9. ST II-II, q. 18, a. 3.

10. ST II-II, q. 20, a. 4c.

11. Ibid.

12. Pieper, Über die Hoffnung, 52.

Hope and the status viatoris

Starting from the theological virtue of hope, it can be clarified in what way we are ‘pilgrims of hope’ or at least should be, as the motto of this year’s Holy Year proclaims. Our entire earthly existence is a pilgrimage. This characterizes the true condition of our existence. According to Christian teaching, we are in a status viatoris. The viator is the wayfarer, this our fate during our earthly lives.13 Only after his death does the final state of man begin – the status comprehensoris, the comprehensor being one who has reached his goal and encompasses it.14

Human beings are, by nature, striving individuals. In their pursuit of the good, they do not seek a chaotic multiplicity of goods but rather a well-ordered hierarchy of goods, at the pinnacle of which stands that which is unequivocally worthy of pursuit: something that represents the complete fulfilment of all our aspirations and actions. This is the aforementioned happiness (eudaimonia), which consists in a good and flourishing life.

The anthropological insight that man strives for happiness (eudaimonia) has been adopted by Christianity from Aristotle. However, the scholastic philosophy of the Middle Ages also recognised that Aristotle’s philosophy, which is limited to this world, offers only an incomplete happiness. In contrast, Aquinas is also aware of the perfect, superhuman, angel-like happiness that is available to man, provided he does not reject God’s offer of grace.

By understanding human earthly life as a being-on-the-way, our creatureliness is likewise emphasized. Creation is not a one-time event but a continuous happening: God sustains His creation from timeless eternity in every moment of existence. This means: Without God, man has no self-subsistence; without his Creator, the creature would fall back into nothingness.

God is not only the origin of man and the cause that continuously sustains his

existence: God is also the true and ultimate goal of man; man is created towards God. The purpose for which he has been called into existence is nothing less than the vision of the Almighty Himself, a vision that ultimately signifies the spiritually loving communion between creature and Creator.

The being-on-the-way of the human creature is, as Pieper states, an ontological ‘Not-Yet’ – and this ‘Not-Yet’ has both a negative and a positive aspect. On its negative side, it signifies the possibility of approaching the nothingness from which humanity was created. This occurs through the turning away from God, which simultaneously is a voluntary turning towards the utter insignificance of one’s own existence. In this orientation towards the nothingness, which is most likely to occur unconsciously, lives the hopeless human. In the worst case, he is not even aware of his hopelessness.

What becomes of the man who has lived from hope and thus receives salvation? For him, hope comes to an end as soon as he has been definitively ushered into the timeless presence of God. Although hope is thus suspended, it is in a different sense from that of condemnation: hope becomes obsolete in heaven because it has been fully realized. In its place arises the beatific certainty of the vision of God. This is the longed-for transition from the status viatoris to the status comprehensoris, as anticipated by those who hope.

A final objection

However, the Not-Yet of humanity also has a positive side, as mentioned: it consists in the orientation towards future fulfilment, the ultimate overcoming of nothingness through eternal communion with God. The theological virtue of hope is nothing other than the firm orientation towards this future salvation. At the same time, hope already contains a present anticipation of the hoped-for state for the future. A person who lives in and from hope lives differently in the here and now from one who exists without hope. The person filled with hope may lead his life with an awareness of his potential nothingness, but simultaneously with the trust that he will escape this nothingness and instead will ultimately enter into the fullness of God’s being.

According to these two aspects of the Not-Yet, there are two definitive states of human existence that mutually exclude each other: damnation and salvation. In one of these, the earthly pilgrimage of man comes to its end. Damnation consists of an endless continuation of existence apart from the fullness of God. Although even the damned, insofar as they exist at all, still have a share in God, their existence is now entirely characterized by sinful futility, by nothingness. Therefore, it can only be a correspondingly dark, shadowy existence – precisely a state of definitive hopelessness.

In conclusion, I would like to briefly address a pertinent objection to living in and from hope. Does theological hope not lead to a devaluation of earthly life? Do we not reduce our existence in this life to a mere means to an end when we understand it as a pilgrimage, the ultimate goal of which lies beyond this life? Does this not amount to an instrumentalisation and thus a devaluation of earthly existence?

This objection is based on a misunderstanding. It is indeed true that every desirable good ultimately receives its goodness from God. Therefore, being with God – the beatifying vision of God – is the ultimate goal of human striving. However, this does not imply that there are no other subordinate goods that we should not also value for their own sake. Honour and pleasure, for instance, are desired for their own sake – but at the same time also in order to achieve happiness in the broader sense. A similar relationship holds for certain activities: art, music, play, or philosophical contemplation, for example, are pursuits that can be meaningful and fulfilling in themselves, which we nevertheless also engage in because they contribute to a fulfilled life.

Thus, the earthly life also possesses an intrinsic value: God has given us this life because it is inherently good, just as the entire order of creation is good. This is already attested to in the creation account of Genesis: ‘God saw that it was good’. However, this intrinsic value of earthly life does not preclude the fact that we have not yet reached our ultimate goal on earth. The best that God has planned for us still awaits us – and the confident expectation that we can attain this best, despite our creaturely proximity to nothingness, is hope.

13. Ibid., 13. 14. Ibid., 11f.

The Little Flower, magazine of Una Voce Nigeria

This is also the magazine of St Therese of the Child Jesus School, established with assistance from Una Voce Nigeria.

Interview with Fr Angelo Van der Putten, FSSP

by Uchenna Okezie

Little Flower: Good morning, Father. We’re interviewing you for the Little Flower Magazine. I’d like to ask you a few questions. Since the last time we spoke with you, how have things been going at the school?

Fr Angelo Van der Putten: Wonderful. I think we can say that this past year especially has been very successful. We’ve had wonderful results. The children have been obviously very influenced by what they’ve learned in school. The Sisters have been tremendous. We can’t really complain, I think, in any way. I mean, the Sisters have been full-time. They’re committed to continuing that. And the teachers are all wonderful and they’re getting better at doing their job, so they’re learning and experiencing, so experiential knowledge. They’re gaining wisdom. They’re getting to know the children better. The children are getting to understand what we want. So I think it’s really wonderful. Things are going very well. We can’t complain. And I think this year is going to be even better in the sense that we have nine more children. And since the teachers and the children already in the school know what to expect and what’s expected of them, then bringing these other children into the school is not going to be an issue. The first year, we had trouble because we didn’t know where to set the children. There’s all kinds of ages and grades and everything. But that’s all been streamlined now. So I think it’ll be a great year.

LF: Wonderful. Would you say there has been an improvement in the cooperation of the parents?

Father: I think so, yes. Like I say, with the teachers and the students, they’re both understanding better, as time goes on, what is expected of them and what to expect from each other. And I think the parents as well. Clearly, the parents are seeing the consequences, the evidence of what is being done in the school. And they come to the parents’ conferences three times a year and they’re reminded of what is expected of them. And I think to a large extent, they’re more cooperative. They’re seeing the tangible results of the education. So I think it’s good. I don’t think we have too much to be concerned about.

LF: All right, great. That’s good to hear. How do you measure the success of the school?

Father: Well, I think it’s very simple. You just walk into the compound and the children are all happy and they’re running around joyfully. They’re smiling, they’re open, obviously very happy. So I think that’s the number one indicator, the happiness of the children. The teachers are happy. And when the parents come to pick up the children, the children are still happy. And then you hear the stories from the parents about the children correcting the parents at home with things that the Sisters and the teachers have told them. So clearly, the education is having a huge influence on the children. And then the children go home and correct their parents. So I think it’s absolutely wonderful.

LF: Great. So how are you doing with finances?

Father: Well, that’s always a tough one, of course. We just had to spend another million naira on booklets. So that’s always a challenge. We have benefactors from Nigeria who graciously help to support the church. But of course, the school fees are simply not equitable with regard to the expenses that we put in the school. The secretary of the school was expressing to me his amazement just the other day about what we have in the school; not only do we have running water constantly in all the toilets and sinks on a regular, constant basis, but we also have toilet tissue, which he said is just simply not existent in any other school. So everything is going well. I don’t think we can complain.

LF: Awesome. So is there anything else you’d like our readers to hear from you?

Father: Well, I think if they come, if people come to see what we’re doing, they will be deeply impressed. And of course, obviously we thank the benefactors, because without them we wouldn’t have a school. But I think if they continue to pray and then if they ever get a chance to come in to walk through the classrooms and see the children and the joy that permeates the school, I think they would be deeply impressed and very appreciative of what we’re doing. So, continue to pray, continue to financially support us, and we’ll see the fruits. We’re seeing the fruits already, so it’s beautiful.

LF: Thank you, Father, and God bless. God bless you.

How Should We Educate Our Children?

Extracted from “50 Days with Fr VdP”

by Uchenna Okezie

The education of children is the responsibility God Himself has given to parents. It is not a duty that can be outsourced to anyone else. Just as you cannot have someone else take your place in the marital act, you cannot have your children be educated by a hireling. A good school is supposed to be only an extension of the Catholic home. This is because Mummy has already started teaching her little child the ABCs, and the catechism and simple prayers, and how to walk and talk and smile and converse and do chores. Then, when the child is about five years old, he is sent to a good Catholic school to see that what Mummy and Daddy have taught them is the right way to live. In school, he is trained in discipline, and taught how to think, how to study, and how to love God. He is taught to know the truth, to always do good, and to notice, appreciate, and love the beautiful. God has created us to know Him, to love Him, to serve Him in this life, and to be happy with Him forever in the next. Any education that does not purposefully help the child achieve these goals is not true education. There is no reason for an education other than to make a person more pleasing to God.

You must recognise and acknowledge that the world is waging a heavy battle against the soul of your children. It is your duty to protect them and keep them in God. The smartphone is probably the most dangerous weapon the devil uses to indoctrinate your child. I do not see how any parent who allows his child unsupervised access to the Internet can be exempt from mortal sin.

You cannot send your child to any school that does not make the impacting of Catholic culture its priority. You must see to it that your child is immersed in a Catholic atmosphere and indoctrinated from the earliest age in truth, goodness, and beauty. Otherwise, you risk losing that child to the suggestions of the world, the flesh, and the devil.

There was a family we visited where one of the boys was arguing with Father about the existence of extra-terrestrial life. He could not see how stupid he was sounding and he insisted on his erroneous position because he has been taught in school to think this way. To change a mind like that is very difficult.

Homeschooling is the next best thing, where there is no good Catholic school available. Getting your children to attend a fine Catholic school is a worthwhile

reason to move. Why else would you choose to live in a certain place? Money?

Follow a schedule in your home. There should be a set time for rising and one for going to bed. There should be fixed meal times, rosary time, study time, and so on. The clock should guide our lives, and it pays to give your children the good example of obeying the clock yourselves. If one is able to order his life on external prompts as a schedule makes you do, it becomes easier to obey the commandments of God and His Church. Do not let your children know that you as a father do whatever you want, when you want to. There should be a good degree of predictability in your life. This helps to increase the trust your children have in you, and they learn discipline. The saints have said that if you succeed in getting out of bed at the same time every day, you have already accomplished half of the spiritual life.

There are four major elements that form the education of a child: good work, good play, study, and prayer.

Make your child work. Give him responsibility as soon as he can crawl. Constantly challenge your child. Do not do for him what he should be able to do by himself. Make the toddler discard

her diapers by herself. Make her pick up things for you and make her run simple chores. By the time the child is two years old, she is ready to water the plants. Teach her to perform these simple tasks and insist on her doing them by herself. Make the boys work with you on the farm, in the garage, in your workshop. Make them love work and work well. Teach them the discipline of producing excellent work always. No compromises. This way, the child grows up knowing that laziness is not an acceptable way of life. He matures quickly and is not afraid of responsibility. The second element is play. Invest in play. And by play I do not mean video games. Never encourage your children to play video or computer games. Do not allow those things in your home. They are horrible. Also, throw out the TV. It is the voice of the devil in the home. Instead, make the children explore and play with

nature. Buy land and have lots of space for the boys to run around and get lost. Encourage them to play outdoors and to do exciting things. Get a trampoline and have them jump on it and exercise their muscles. And when you spend time indoors, play board games that task the mind. Teach your kids to strive to win, but also to accept losses well. They should play fairly, lovingly, and diligently. You can accomplish more character formation on the playing field than you can by praying 15 decades of the rosary in the chapel every day.

The next element is study. Your child should have a curiosity for the things God has created. She should want to know the names of the flowers, the names of the different kinds of animals, how our body systems work, and how God has designed this orderly world. It is your duty as her parents to nurture this curiosity. It is a sign of gratitude to God, Who has created all things well, that we seek to learn about them to better appreciate them. Your child needs to polish his natural gifts so he can better use them for the glory of God. This is where reading comes in. (John Senior’s list of the thousand great books is a wonderful guide to good reading. You can find it in the last chapter of his book The Death of Christian Culture.) Reading exfoliates the mind and sharpens it for the appreciation of the true, the good, and the beautiful. Teach your child to enjoy spiritual reading. He should also read the lives of the saints. The saints are the real heroes, not these silly Marvel characters that are being socially engineered into

your children’s imaginations. Every child wants to be Superman and Spiderman. Who wants to be St Benedict Labre or St Therese of the Child Jesus?

The last major element in your child’s education is prayer. Prayer is the raising up of the mind and heart to God. ‘Raising up’ means that, due to our fallen human nature, it requires some effort to lift our minds from mundane things and focus them on the good God. To make a habit of prayer requires constant practice from the earliest age. So the parent should often speak of God to the children, and remind them to offer up their pains and frustrations. For example, you can teach your little toddler to say ‘Deo gratias’ whenever he cries from pain. This way, the child begins to realise, little by little, that we have been created for another world and are only sojourners in this temporary world. Place many holy images and statues around the home and teach your kids to venerate some of these images, perhaps with a simple bow, when they pass them. This helps to keep the presence of God in their consciousness. Teach them the catechism and have them memorize as much of it as they can. Pray the rosary as a family every single day, without fail. Only 5 decades a day, not 15. Do not make family prayers too long. Short morning prayers, short night prayers, grace before and after meals, and the family rosary at the same time every evening.

Take the kids to daily Mass and insist they behave themselves. No crying in the church, no chatting, no slouching. They

must kneel when you kneel and stand when you stand. Teach them to reverence the Divine Presence even when they do not yet know what It means. Take your family with you as much as possible to parish communal devotions: Stations of the Cross, parish rosary, Benediction, potlucks. Go with your children to devotions. Don’t just send them off to Block Rosary to go and pray while you sit in the shop and make money. They would grow up to be like you, chasing money and not having time to pray. Your kids must not learn from your example that church devotions are for kids and that adults have more important things to worry about. If you need to adjust your lifestyle to allow you to go with your children to church, trust me, it is totally worth it. I know the logistics of carrying little children around all the time can be a huge inconvenience but this is what you signed up for when you answered God’s call to get married. The kids need all the good influence they can get, so do not hesitate to take them with you to visit priests, attend ordinations, or things of the sort.

The most important education to give your child is to make him to never do his own will. Never let your child do his will. He must do your will. This is difficult to achieve because crushing anyone’s will involves a lot of pain. So insist that the baby sleeps when you say she must sleep (I recommend 7 p.m. every evening, so that the husband and wife can get to spend plenty of time

alone before they sleep). Train your child to keep quiet when you say so and to obey all simple instructions you issue. Come, sit down, stand up, kneel down, eat your food, keep quiet, go to Mummy, and so on. Your child should never disobey you from the time he is seven months old. Each time he disobeys you, or anyone else for that matter, he should immediately receive a painful punishment.

Finally, allow your children to spend plenty of time around you. Let them be there with you when your friends visit. They should listen to your conversations. If there are discussions you are not proud to have in the presence of your kids, you probably should not be having those discussions. Take your child with you when you go grocery shopping,

when you go to make your visit to the Blessed Sacrament, when you go to have a drink with the priest. When you are reading a book, have your child sit near you with her own book and read silently. Children learn more from what they see than from what we tell them. Every parent should desire that his children become like him. You will succeed if you consciously work hard at it. And the beautiful thing is, the more you take this job seriously, the more you will see an advancement in your own soul, for charity increases the more it is spent. Never worry about trying to make your child know that you love him. You have nothing to prove. Simply love your kids by educating them right, and that is all that matters. They know you love them.

The Joy of Gardening

God’s orderly world ... what a beautiful creation made by His majesty. Everything made is precise and proportional. God spoke, and all was made in six days. Man, the pinnacle of creation, was formed from the slime of the earth, and God breathed life into man and placed man in the Garden of Eden.

Man was given dominion over all creatures. He was given the task to tend the Garden of Eden with its beauty and splendour. The garden was endowed with an array of flowers and fruit-bearing trees. Man had everything needed for his self-sustenance. One can only imagine how awesome was the garden fashioned by God. It is safe to say that man’s first occupation was farming.

When man fell, the whole of creation was also affected. And part of the consequence was that man was kicked out of the Garden of Eden. Man did not forget his first occupation – farming/ gardening. Adam taught his children the art of gardening. Cain and Abel were predominantly farmers. Cain tended towards planting crops, while Abel shepherded the animals.

An aspect of gardening is the cultivation of flowers. Each and every flower reminds us of the grandeur of Eden. Flowers not only add colour, texture, and biodiversity to the environment but are also a reminder of the profoundness of the creation of God.

Gardening in the home provides the necessary support every family needs. In an ideal family, there sits a garden with its crops, flowers, and domestic animals. The children are introduced to the art of gardening right from a tender age. Each child is assigned a task to perform routinely. There is the father with his boys, whom he trains to be men, tilling the soil, dressing the piece of land for the next planting season. The boys, led by their father, sweat with joy and show no sign of boredom.

The mother and her pretty girls look after the poultry and ensure that the chickens are fed properly and the poultry is cleaned regularly. She works with her girls to ensure the viability of the seeds for the next planting season. Not forgetting there are flowers planted in

the garden, the mother teaches her girls to daily beautify the altar with flowers and not forget the grotto of Our Lady outside the house. The girls are taught how to make the home admirable.

Throughout the planting season till harvest, routine work is done in the garden by the children. Each child is given a task, and it is done joyfully. No one is bored. Gardening is not only a daily schedule but also a delightful chore.

Parents must have a garden at home, or at least plant flowers and vegetables in small pots to keep the children busy and make the home beautiful.

Train up a child in the way he should, and even when he is old he will not depart from it (Proverbs 22:6).

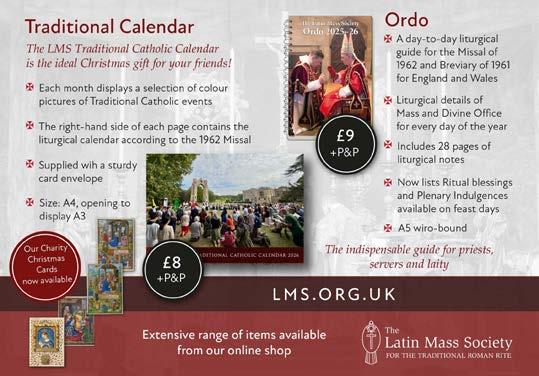

Mass of Ages is the magazine of the Latin Mass Society of England and Wales

In this edition of Gregorius Magnus we reprint three articles from Mass of Ages.

Ad multos annos to the Latin Mass Society!

by Name

Bishop Athanasius Schneider visited England in June to take part in the Latin Mass Society’s Faith and Culture Conference and Holy Cross Pilgrimage, both held as part of the Society’s sixtieth anniversary celebrations.

During a six-day visit coinciding with the Octave of Pentecost, His Excellency celebrated Solemn Pontifical Masses at Northampton Cathedral, St William of York in Reading, and the Shrine of St Augustine in Ramsgate. He also presided at Solemn Pontifical Vespers at the London Oratory, a service held in connection with the Faith and Culture Conference at which he spoke on The Joy of our Catholic Faith. Each liturgical celebration concluded with singing of the Vexilla Regis and Benediction with the relic of the True Cross which is touring England and Wales in the Holy Cross Pilgrimage.

At a dinner held in Bishop Schneider’s honour at the Rembrandt Hotel—the very place where the Latin Mass Society was founded in 1965—he praised the

Society’s work in safeguarding the Church’s liturgical tradition and offered his heartfelt wishes for its continued flourishing over the next sixty years.

The Importance of Tradition A report from the LMS Faith and Culture Conference

The atmosphere was buoyant as the Latin Mass Society’s sixtieth anniversary Faith and Culture Conference heard from a range of prominent speakers about the importance of tradition in shaping the Church’s mission for the future. All talks are now available to watch on the LMS YouTube channel.

The sold out conference at the London Oratory was joined by a global livestream audience, first hearing from Bishop Athanasius Schneider, who was visiting England to participate in the conference and a programme of other LMS anniversary celebrations. Next came the philosopher and LMS Patron Prof Thomas Pink, who gave an engaging paper on ‘Tradition, Secular and Religious’ and the historian and journalist Dr Tim Stanley, who captivated the audience with his incisive ‘Reflections on 20 Years as a Catholic’.

After lunch, LMS Chairman Dr Joseph Shaw rallied the troops, with his address, ‘Evangelising after the Cultural Revolution’, in which he highlighted the Church’s opportunity to respond to contemporary cultural challenges. The acclaimed contemporary painter, James Gillick, then offered an impactful exposition on how sacred art can engage and transform believers.

The conference concluded with a keynote address by Cardinal Raymond Burke, appearing via video link from America. The Cardinal used the occasion to give a theological commentary on the relationship between the Sacred Liturgy and the Divine Law, the Jus Divinum.

The day concluded with a magnificent celebration of Solemn Pontifical Vespers – the First Vespers of Trinity Sunday –at which Bishop Schneider presided. The visceral beauty of the liturgy—in its sacred music, ceremonial richness, and reverent atmosphere—offered a fitting culmination to the conference. It served as a living expression of the themes explored throughout the day: the power of tradition, the role of beauty in worship, and the enduring vitality of the Church’s liturgical heritage.

Sacred Light