Books to Think With From CHICAGO

States of Plague

Reading Albert Camus in a Pandemic

“Camus argued that ‘The true work of art is one that says the least’. La Peste is such a work, and States of Plague is a moving, thoughtful, and scrupulous examination of both the novel and its readers, the book’s inheritors.”—Times Literary Supplement

CLOTH $20.00

Dangerous Children On Seven Novels and a Story

“In a series of startling insights and evocations, Dangerous Children reveals just how uncanny and enigmatic children can be. In eight really quite brilliantly subtle chapters Gross shows us, improbably, that we have never really been curious enough about childhood.”—Adam Phillips, author of On Getting Better

CLOTH $27.50

Atmospheres of Projection

Environmentality in Art and Screen Media

“To project is to throw forth, to transform, to draw, to plan, to move forward. Existing long before the cinematograph and surviving the transformations of this medium in the digital era, projection is too pervasive to be forgotten.”—BOMB Magazine

CLOTH $45.00

Now in Paperback The Modern Myths

Adventures in the Machinery of the Popular Imagination

“Their fecund capacity to produce new narratives is what allows these myths to do their ‘cultural work’: they ‘erect a rough-hewn framework on which to hang our anxieties, fears, and dreams.’”

Los Angeles Review of Books

PAPER $22.50

W.

Edited by Paul Buhle and Herb Boyd

Introduction by Jonathan Scott Holloway Paul Peart-Smith (artist)

Deirdre Boyle

Edited by Andrew R. Spieldenner and Jeffrey Escoffier

Edited by Shantel Gabrieal Buggs and Trevor Hoppe

THE LARB QUARTERLY No. 37 SPRING 2023

Publisher: Tom Lutz

Editor-In-Chief: Michelle Chihara

Managing Editor: Chloe Watlington

Senior Editor: Paul Thompson

Poetry Editors: Elizabeth Metzger and Callie Siskel

Art Director: Perwana Nazif

Type Director: J. Dakota Brown

Copy Desk Chief: AJ Urquidi

Executive Director: Irene Yoon

Social Media Director: Maya Chen

Publications Coordinator: Danielle Clough

Ad Sales: Bill Harper

Contributing Editors: Aaron Bady, Annie Berke, Maya Gonzalez, Summer Kim Lee, Juliana Spahr, Adriana Widdoes, and Sarah Chihaya

Board Of Directors: Albert Litewka (chair) , Jody Armour, Reza Aslan, Bill Benenson, Leo Braudy, Eileen Cheng-Yin Chow, Matt Galsor, Anne Germanacos, Tamerlin Godley, Seth Greenland, Darryl Holter, Steven Lavine, Eric Lax, Tom Lutz, Susan Morse, Sharon Nazarian, Lynne Thompson, Barbara Voron, Matthew Weiner, Jon Wiener, and Jamie Wolf

Editorial Interns: Genevieve Nollinger and Kali Tambreé

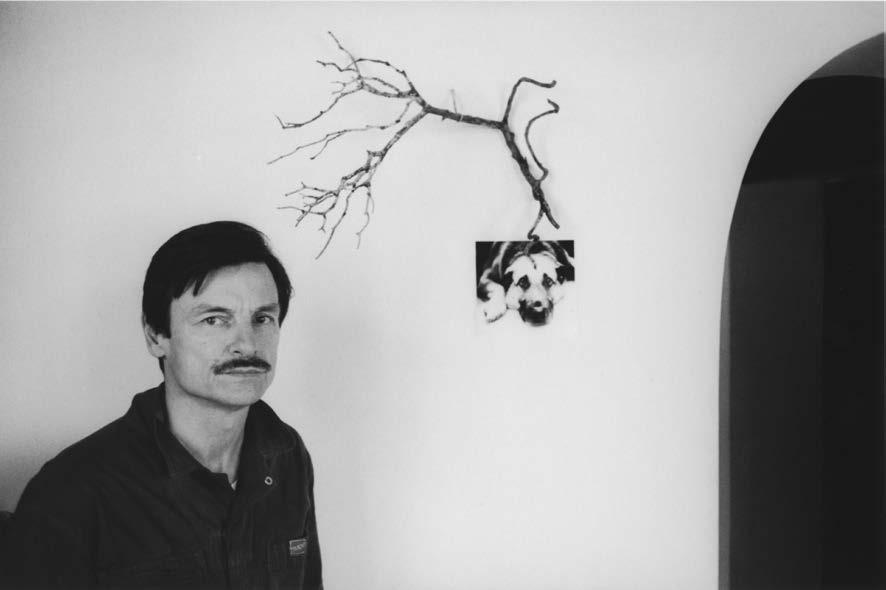

Cover Art: Image from Curtis Cuffie published by Blank Forms Editions. Photography by Tom Warren, 1997. Courtesy Tom Warren.

Cover Design: Ella Gold

The Los Angeles Review of Books is a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit organization. The LARB Quarterly is published by the Los Angeles Review of Books, 6671 Sunset Blvd., Suite 1521, Los Angeles, CA 90028. © Los Angeles Review of Books. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Visit our website at www.lareviewofbooks.org.

The LARB Quarterly is a premium of the LARB Membership Program. Go to www.lareviewofbooks.org/ membership for more information or email membership@lareviewofbooks.org. Annual subscriptions are available at www.lareviewofbooks.org/shop.

Submissions for the Quarterly can be emailed to chloe@lareviewofbooks.org. To place an ad, email bill@lareviewofbooks.org.

“Engaging and insightful ... each chapter reveals why, for many of us, music is as essential as breathing or eating.”

—Valerie Day, lead singer of Nu Shooz and Grammy nominee

“

The Narrow Cage and Other Modern Fairy Tales is a marvel in every sense of the word. Adam Kuplowsky’s translation is a masterful homage to a storyteller whose own journey holds all of the hope and despair the best fairy tales contain. Read this book!”

—Amanda Leduc, author of Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space

“A treasure trove of inventive and sometimes subversive fables that transcend borders.”

Tokyo Weekender

“The very best food journalism lifts the veil on everyday components of our diet, peeling away accumulated layers of hype, pseudoscience, and ingrained fallacies to reveal the truth. No writer today does this more deftly than Anne Mendelson. Spoiled is the result of scrupulous and unbiased research presented in delightfully readable prose. A masterpiece.”

Barry Estabrook, author of Tomatoland

“Vincent Figueredo helps us to understand the heart as a cultural symbol, biological miracle, and central theme in human history. A tour-de-force of scholarship and storytelling, The Curious History of the Heart is a great read and an important one.”

—Daniel Weiss, president and CEO, Metropolitan Museum of Art

“A thoughtful and thorough consideration of a global movement.”

Publishers Weekly

THE LARB QUARTERLY No. 37

SPRING 2023

INTERVIEW

13 FIRE ROUND with Tongo Eisen-Martin

NONFICTION

25 WHAT NOT TO WEAR

Bharat Jayram Venkat

31 “SIR, YOU DO REALIZE I AM 9-1-1?”

Jaime Lowe

37 SOWING THE FUTURE

Mike Davis and Jon Wiener

45 THIS NIVÔSE: THE DIARY OF A MONTH IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY CALENDAR

Sharon Kivland

59 TWO THINGS TOUCHING

Claressinka Anderson

PORTFOLIO

74 HERVÉ GUIBERT AND CURTIS CUFFIE

Introduced by Perwana Nazif

FICTION

69 ANOTHER MATTER: THE FIRE EXCERPTS

Alla Gorbunova, translated by Elina Alter

92 METAPHYSICS IN THE NUDE

Vladimir Sorokin, translated by Max Lawton

103 WITNESS STATEMENT

Bud Smith

109 OMISSIONS

Mike Jeffrey

122 BLACK SUN

Etel Adnan, translated by Laila Riazi

POETRY

131 THE WARRIOR IS A WOMAN

Tina Chang

133 HARVEST

Megan Pinto

135 THE NIGHT

Katie Peterson

138 PORCH POEM

Jessica Abughattas

139 [I HAD A BOUT]

Jane Huffman

141 THIS NATION

Shangyang Fang

“A revealing and original book about an understudied aspect of the Holocaust. Highly recommended.”

—Jan T. Gross, author of Neighbors

—Jan T. Gross, author of Neighbors

“[A] superb biography. . . . Turner’s beautifully written, rewarding and thought-provoking book about this imaginary woman shows how much her literary existence has to say about actual women’s lives.”

—Gillian Kenny, The Spectator

—Gillian Kenny, The Spectator

“One of our most eminent historians of American art here joins impeccable scholarship with an abiding love of blues, rock, and punk to spin the tale of California artists’ surprisingly central role in a cultural revolution.”

—Carrie Lambert-Beatty, Harvard University

—Carrie Lambert-Beatty, Harvard University

“Written with Lavery’s precision and daring, Pleasure and E cacy is both a challenging theory of trans realism—developing the deep significance of DIY ethics and trans avowal over ontological approaches—and a lifeline of intellect and warmth in an era of transphobic violence.”

—Rei Terada, author of Metaracial

—Rei Terada, author of Metaracial

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Dear reader,

Near Sunset Junction, around the new year, an aspiring pop star or someone who works for her, or a sympathetic friend spray-painted a QR code onto the sidewalk, alongside a line from her recent release:

I don’t wanna die in L.A.

Her name is Hunter Daily. Her mother once starred in a Nic Cage rom-com called Valley Girl. Her father, the enfant terrible poker player Rick Salomon, produced movies and was married to Elizabeth Daily before marrying and divorcing a string of other actors.

Hunter sings, “There’s more to life than palm trees / And looking good at parties […] Take me, this city makes you crazy / And I won’t say I hate it / ’Cause I love it just the same / But I don’t want to die in L.A.”

For most people here, the glitzy palm-tree version of L.A. is a relic suspended in amber, maybe still glowing in Malibu or somewhere west of La Brea. But only as a remnant. I don’t live in Daily’s Los Angeles, and I don’t particularly want to die there. And yet, I like the song. It’s pleasurable to conjure that bubble and then to resent it a little.

Pop-star aspirations and an attachment to sunshine and noir Daily’s snuffing of those glamorous fumes are woven into the texture of the city. If you live here, you know the release that comes from speeding out the curve from the McClure Tunnel and turning up the volume. You know the incandescent rage of Bad Religion’s classic punk anthem “Los Angeles Is Burning” “palm trees are candles in the murder wind. ” Freedom and anger. It’s a heady mix that’s baked into the Pacific Coast Highway.

I’m a lifelong California girl with just two decades in Los Angeles. In the same way that only you get to criticize your family, I feel vaguely entitled to obsess over the noir history and the cults and the tech-bro California ideology. I get to resent the beautiful actors, the loony wellness trends, and yes, even the hours of my life spent on the 5. And I still get to love it and claim it all as my own private contradiction. Since I noticed it on the

pavement, I’ve had “Die in L.A.” on gentle rotation.

A darker soundtrack has always echoed through L.A. I’d rather dwell on how we live with it than try to drown it out. And a significant part of how I have lived with all of the challenges of this place has been by engaging it as an editor and a writer for the Los Angeles Review of Books. For almost a decade, as a member of the community of arts and letters that LARB brings together, I’ve participated in conversations and reflections on this city and how it opens out onto the world beyond. After the 2016 election, writers and artists and academics gathered at an independent bookstore in Los Feliz to share words that we then circulated and published, in a moment that felt lifesaving. I am incredibly grateful that the Los Angeles Review of Books is now my full-time gig.

Sometimes locals still joke that they’re surprised that Angelenos read. They get to make that joke. But the city, as the nation’s biggest midlist publishing market, has had a vibrant book culture for decades, ranging from the big-ticket L.A. Times Festival of Books to the indie Beyond Baroque to a dynamic public library system to independent presses like Tia Chucha and Kaya Press. Right now, though, media outlets and writing centers and arts organizations and schools are struggling and closing all around us. The book industry still publishes tens of thousands of books a year, and people still care about books. But as the polycrisis rolls on, nothing makes economic sense, and book supplements and literary magazines continue to fold. As an editor, I feel that I’ve been handed something fragile and precious, as I try to keep the conversation alive.

Like Hunter says, there’s more to life than palm trees, especially in the times and spaces where we pause to reflect and to reconnect. Books and stories can provide an escape from the harrowing news cycle; talking about books can be a dreamspace apart and outside that helps get us through. At the same time, sustained inquiry and indepth research the truth itself needs the ecosystems of knowledge that exist only through books. Talking about books is evanescent and fun, and it’s deadly serious. It’s leisure-class fluff, and it’s everything that holds meaning, all at the same time. Just like this crazy city.

As I step into this new role, our mission remains to bring the complexity and radiance of Los Angeles to the world and to bring the world to Los Angeles. The LARB Quarterly will be a magazine that puts this Pacific Rim megalopolis on the map, a magazine of Los Angeles but for the world, a magazine that finds the universal in the local.

Last year, the Quarterly asked questions, like: Do you love me? Isn’t it uncanny? Are you content? This year, we plan to cut through the increasingly fractured, atomized publishing landscape by cutting close to the bone, by writing into what is inarguable, essential what is elemental.

Throughout 2023, the Quarterly will explore how the elements that comprise everything fire, earth, air, and water shape us, and how we can harness them in turn. First is the Fire issue, a theme that in its literal incarnation has become all too present in the lives of Californians, whether those driven from their homes by the wildfires that seem to be ever-spreading, or the incarcerated people conscripted to fight those fires, or those who merely breathe

Pushing the boundaries of visual culture, science, technology, and society

White Sight

A new history of white supremacist ways of seeing—and a strategy for dismantling them. Mirzoeff connects Renaissance innovations with everexpanding surveillance technologies to expose how white sight creates an oppressively racializing world.

#You Know You’re Black in France When…

What does it mean to be racialized-asblack in France on a daily basis? Tricia Keaton offers a groundbreaking study about everyday antiblackness and its refusal in an officially raceblind France.

The Language of the Face

For thousands of years, artists, philosophers, and scientists have explored the question of what our outer appearance might reveal about our inner selves. This broad and riveting cultural history of physiognomy explores how the desire to divine deeper meaning from our looks has compelled humans for millennia.

Sol LeWitt’s Studio Drawings in the Vecchia Torre

A visual archive of Sol LeWitt’s masterpiece of conceptual art, this book situates the artist’s provisional, material, bodily, and highly personal drawings in their historical, biographical, and theoretical contexts.

Gallup

A poignant artistic collaboration, showing how history and mythology converge in the Navajo communities in and around Gallup, New Mexico in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

in that detritus on their way to work or school. But fire is also personified in stories of grifting, gambling, urban despair, political assassination, everything that goes up in smoke and, of course, love, dreams, and more deepfakes.

I don’t want to die in Los Angeles, but I want to drive right out to the edge of the Pacific Coast Highway with “Die in L.A.” at full volume, and I want to invite the world along for the ride. Another Angeleno friend and writer likes to say that the future happens here first. You can love it from afar or hate it up close or remain committed to your deep and productive ambivalence about it, but you should definitely read about it.

An undergraduate student at UCLA sent us her self-produced, pitch-perfect spoof of The New Yorker called The Angeleno. Samia Saad, who included no social media handle or email, made the glossy deepfake “to satirize the ridiculous monopoly the East Coast has on ‘high-end’ literature and journalism.” It was accepted into her undergrad art show, but its circulation stopped in a manila envelope delivered to my desk. She thanked us “for all the phenomenal work you do proving that there is a vastly talented community of writers and a readership in Los Angeles and up and down the Pacific coastline. I only gripe that your existence takes a bit of the punch from my satire by rendering part of it untrue and obsolete.”

The editors of the Los Angeles Review of Books would like to invite Samia Saad of The Angeleno to make fun of us, any time, on her way to becoming a senior editor at The New Yorker and to pitch us, too. We hope Samia Saad continues to mock everyone in her way, and we want to reach all

the readers and writers who understand that the things that burn you up are also the things that keep you warm. Borrowing a metaphor from Sharon Kivland, from her French Revolutionary calendar diary in this issue, “Saltpeter is incendiary, Greek fire, but also preserving.”

Whatever you listen to on PCH, whatever dark romance you have with the places where you want to live and die, and however the elements inspire you, I hope you’ll spend time with the Los Angeles Review of Books and all of our programs, come hellfire or high water, this year.

Love,

Athena Unbound

An excerpt from Athena Unbound by Peter Baldwin: a clear-eyed examination of the open access (OA) movement—past history, current conflicts, and future possibilities.

Torrents have been written about open access, but little comes from those who supply or consume knowledge: the scholars who produce the works that are to be accessible and their potential readers, whether colleagues or the general public. Instead, the drum is beaten by librarians, information- and data-science scholars, media professors, and others who populate a kind of second-order stratum of academia, scholars of scholarship.

A vast quantity of work has billowed forth, professionalizing the field by making it a full-time job just to keep up. Countless conferences, workshops, networks, study groups, Twitter feeds, journals, and blogs keep up a tireless outpouring. The caravan moves on, but where is it going? Founding and running open-access journals and publishers, organizing boycotts of the worst-o ending academic presses, lobbying politicians to reform copyright laws, probing the boundaries of what counts as legal under current rules: such activities move us toward a freer exchange of information. What the theorizing and discussion contribute is less obvious. As so often in the academic world, noble intent does not necessarily produce tangible results. Process is often confused with progress.

Why, then, add another brick to the edifice? Because many participants come from a nimbus formed around the scholarly enterprise without being part of it, they often pay little attention to workaday academics’ concerns. Especially in the humanities, arts, and social sciences, the professoriate is surprisingly ignorant of—and, if aware, often hostile to—open access. Because the well-funded sciences have been the first to warm to the cause, open access has been tailored to their specifications, with publishing fees paid out of generous research budgets. Including less well-endowed fields remains a hurdle.

Athena Unbound seeks to flesh out debates that often remain focused on the sciences. It situates current discussions in a long history of information’s progress toward greater openness. Despite the mantra that “information wants to be free,” much does not. Corporate R&D makes up the majority of research and is not striving for release. Most writers of fiction and commercially viable nonfiction sell their wares in the marketplace, hope to live from the proceeds, and have no interest in opening up. That holds for most producers of visual and aural content, too. Nor are privacy and open access harmonious bunkmates. We naturally resist freeing up information about ourselves except as we choose.

The problem of too much information is a leitmotif. Even without copyright reform or open access, as the public domain inevitably expands, freely available content will eventually dwarf what any current cohort of creators issues.

Sponsored by the MIT Press

What e ect will this have on future cultural producers’ motivations to bring forth novel work? What does the common complaint that we disgorge too much information mean? Can more information ever be a bad thing, even if some is mediocre?

Enthused by the idea that openness must be an absolute, the debate often fails to situate the particular circumstances of academic knowledge in the broader domain of intellectual property. For most content, there is no moral case for accessibility. Yes, other arguments also speak for the virtues of opening up—the logic of knowledge as a commons and the turbocharging of its usefulness allowed by networks. These are claims of public utility. None packs an ethical punch. Most cultural producers do not (yet) want to make work freely available. Only for content that society has paid for can it also claim access. Work for hire is the logic of open access’s moral leverage. But when applied to scholarship, it is often dismissed as a neoliberal encroachment on academic freedom and the sanctity of the university. Perhaps it could just as well be seen as an element in democratizing access to the ivory tower’s knowledge.

The humanities and social sciences have been the stepchildren of these debates. For the hard sciences, existing funding only needs to be repurposed. The expense of disseminating results is a small fraction of research’s total cost. But more than money separates the humanities from the sciences. Humanists cannot be as indi erent to aesthetic and presentational issues as their scientific colleagues. They claim a continued stake in how others use their works. Their data are not just nature’s coalface, but often the copyrighted work of others to which they can lay no claims. Lack of funding has not only hamstrung their ability to adopt open access on the scientific model. The sciences’ ability to solve the problem for themselves has drained library budgets that once were more equitably shared, compounding the issue for other scholars.

FIRE ROUND

Tongo Eisen-MartinI recently saw the San Francisco Poet Laureate Tongo Eisen-Martin give a reading at Beyond Baroque in Venice Beach. Tongo was not reading his poetry out of book or with any notes, instead he recited every line from memory. His parlance raised and lowered, the content and his real time reaction to it controlled his dictation and meter. The outcome was quite exceptional, like watching someone possessed by a spirit; the poetry had force and electricity. Thinking back on the reading, the most appropriate line of questioning I could imagine was a fire round, so here it is. Chloe

New and Forthcoming from The University of Texas Press

Quantum Criminals

Ramblers, Wild Gamblers, and Other Sole Survivors from the Songs of Steely Dan

by Alex Pappademas and Joan LeMayWhy Tammy Wynette Matters by

Steacy Easton

Steacy Easton

Why Sinéad O’Connor

Matters by

Allyson McCabePitching Democracy

Baseball and Politics in the Dominican Republic by

April YoderResurrecting Tenochtitlan

Imagining the Aztec Capital in Modern Mexico City by

Delia Cosentino and Adriana ZavalaThe Comitán Valley

Sculpture and Identity on the Maya Frontier

by Caitlin C. EarleyChanneling Knowledges

Water and Afro-Diasporic Spirits in Latinx and Caribbean Worlds by Rebeca

L. Hey-ColónShifting Sands

Landscape, Memory, and Commodities in China’s Contemporary Borderlands by Xiaoxuan

LuWe Are All Armenian

Voices from the Diaspora

Edited by Aram MrjoianThe Thirty-first of March

An Intimate Portrait of Lyndon Johnson

by Horace BusbySelling Science Fiction

Cinema

Making and Marketing a Genre by

J. P. TelottePoetry: June 19 - 25

Fiction, Nonfiction & Memoir: J uly 10 - 17

Application Deadline: March, 2023

For additional program details and to apply, visit: communityofwriters.org

Financial aid available

What’s the best advice you ever got from your mom?

Unity is more important than speed.

What are you getting worse at?

Defeating my homebody tendency.

Better?

Dealing with pain.

Do you think about your own death?

Yes, maybe tri-hourly.

Have you ever dreamed about fire?

Fire is rarely a protagonist in my dreams. I can’t think of an instance, but I did semi-recently dream that my cousin (who had recently passed away) wanted us to drive to a strange sea level volcano.

Why do you write poetry?

It is what my mind coughs up when it is resting in the respect of interconnectedness.

Pretend you are someone else and answer: why do you write poetry?

My family enjoys it.

What do you want?

Liberation for all oppressed peoples.

NEW FROM AVIDLY READS

READ AVIDLY. THINK BOLDLY.

“It is a truth too rarely acknowledged that there is nothing better than being both smart and fun: how lucky for us, then, that Avidly Reads books are both. To delve into them is to engage new ideas without having to sacrifice pleasure for knowledge, or feeling for thinking.”

“This book offers a roomy haven for working out what it means to live and grow up in a modern age, honoring the tangle of feelings—bad, euphoric—that accompany our most sacred rituals, from appointment television to all that scrolling.”

“Hopscotching elegantly from Twin Peaks to bedtime doomscrolling, Zoom school to Vine, Maciak explores the deep paradoxes of ‘screen time,’ the mirror we all gaze into, at once together and alone."

“Phillip Maciak is one of the best TV critics alive right now, full stop.”

The Millions

Emily Nussbaum, author of I Like to Watch Naomi Fry, writer at The New Yorker Lauren Michele Jackson, contributing writer, The New Yorker“Vegas

is

—John L. Smith, author of Saints, Sinners, and Sovereign Citizens: The Endless War Over the West’s Public Lands

cl 978-1-64779-100-1 • e-book 978-1-64779-101-8 • $24.95

“Wright has given us a gorgeously written journey, equally adventurous and sobering. It is a beautiful and necessary book.”

—Jesse Goolsby, author of Acceleration Hours

pbk 978-1-64779-096-7 • e-book 978-1-64779-097-4 • $22

“Moreno is one of the leading, most experienced writers on Nevada history and he did a masterful job of telling the story of these gifted, quirky writers.”

—Martin Gri th, Associated Press journalist, 1985-2015

pbk 978-1-64779-086-8 • e-book 978-1-64779-087-5 • $21.95

The sea that calls all things unto her calls me, and I must embark.

“A lively adaptation of The Prophet, one sure to draw in new readers and invite those with well-worn copies of Kahlil Gibran’s beloved work to rediscover it all over again.”

—Nick Sousanis, author of Unflattening graphicmundi.org

Strong

thoughtful, touching, and a reminder of this absurdly violent era in which we live.”UNPRESS.NEVADA.EDU

Klip and Corb on the Road

e Dual Diaries and Legacies of August Klipstein and Le Corbusier on their Eastern Journey, 1911

Ivan Žaknić

In 1911, Charles-Eduoard Jenneret (Le Corbusier, 1887–1965) embarked on a grand tour of Eastern Europe, Turkey, and the Balkans with his friend, August Klipstein (1885–1951). Both young men kept detailed notebooks throughout their journey with drawings, sketches, and photographs created en route. While Le Corbusier’s notebooks were published in 1966 as Journey to the East and attained wide renown, Klipstein’s record of their travels has remained relatively unknown. And yet two witnesses to the same events should provoke anyone familiar with Le Corbusier to seek the other side of the coin.

In Klip and Corb on the Road, Ivan Žaknić brings the notebooks together for the rst time to explore the fruitful creative symbiosis of this friendship. Richly illustrated, the book includes copious previously unpublished material, including the complete text of Klipstein’s diary and the friends’ correspondence.

Cloth $55.00

“An important reflection on evolutionary theory, o ering a radically new perspective on the transition from biological to cultural evolution.”

Jürgen

Jürgen

“A timely intervention in our age of debates about fact and fiction, Fuchs o ers fresh insights on small forms.”

“A landmark study that will change the terms in which Goya’s art will henceforth be understood.”

Peter

Bolla,

Peter

Bolla,

“A startling meditation on the ways monuments defy the everyday and succumb to it.”

“A great book for our time: a moment when our own sense of good cheer has been challenged by political and social upheaval.”

“One of the most original, compelling, and intellectually rigorous books ever written on the plagues of history.”

— Brad Evans,University

of Bath

Until recently, Dan shared this apartment – right across the street from Vitsœ’s New York shop – with his dog, Sullivan.

They’ve since switched home – and coasts – for a new life in Seattle, Washington, together with their treasured Vitsœ shelving system.

Whether you’re just over the road, or on the other side of the globe, Vitsœ’s planners are on hand to take care of you personally.

If you’re planning your first system, moving it to a new home, or reconfiguring a decades-old system, our team offers expert help and advice, free of charge.

Founded 1959

Design Dieter Rams

Delivered

vitsoe.com

“I wanted furniture I could grow old with ... Vitsœ provided just that.”

The Interpretation of Owls

$24.99 $19.99 | 978-1-4813-1734-4 hardcover | 478 pages | 6 x 9

“For some four decades, John Greening has been a centering figure in the poetic landscape of Britain: a poet whose unbounded curiosity has taken him through the wide (and often conflicted) world with a passion for details that root his work in place. He finds, in a broad range of settings and circumstances, a language adequate to his emotions. Like Auden, he seeks out memorable language in a variety of poetic forms. I hope this marvelous selection brings a grateful audience to his splendid, moving, spiritually adept, and always provocative work.”

—Jay Parini, author of New and Collected Poems: 1975–2015

Panzer Herz: A Live Dissection

Poems by KYLE DARGAN

Poems by KYLE DARGAN

A poet’s final barbed compilation that pierces the inherited and self-inflicted experiences of masculinity

Synthetic Jungle

Poems by MICHAEL CHANG

Poems by MICHAEL CHANG

“A bewildering collection of ache, awe, and rebuttal.”

—PHILLIP B. WILLIAMS, author of Mutiny

—PHILLIP B. WILLIAMS, author of Mutiny

Los Angeles Review of Books is proud to be printed by Hemlock Printers

Hemlock Printers had a humble beginning: a backyard studio with a letterpress and an A.B. Dick offset. Since then, Hemlock has grown to be the most reliable printer in the business (according to us!). In this industry it is difficult to find a combination of mass production and sustainability, but Hemlock comes through on that front. Hemlock has a plan to be Zero Waste by 2030 and they offer a ZERO Carbon Neutral Printing Program. Their craftsmanship is evident in these pages you hold in your hands and in all the many publications like ours they print and distribute.

www.hemlock.com

Hervé Guibert

Thierry la grille, 1980

Vintage gelatin silver print

© Christine Guibert / Courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris

WHAT NOT TO WEAR

A manikin in a suit

by Bharat Jayram VenkatIn the fall of 2019, Fiona Hill strode into the Longworth Office Building in Washington, DC , sporting a white blouse and a subdued chain-link necklace peeking out from below a black blazer. Her outfit, in the words of a writer at the Washington Post, was “ferociously, unapologetically dull.”

The dictates of feminist reportage would suggest that there’s nothing so regressive as obsessing over a powerful woman’s clothing choices (see, for example, much of the coverage of Hillary Clinton’s tragically unsuccessful presidential campaign in 2016).

That day, Hill had an important job to do: she was to testify before the House Intelligence Committee. Her testimony would be televised, as a fact witness preceding the Senate’s first impeachment trial for then-president Donald Trump. Hill was a Russia expert, and the former senior director for Europe and Russia at the National Security Council; her words would undercut the right-wing narrative of Ukrainian meddling and point instead to the Kremlin’s investment in sowing discord in American politics, despite Trump’s claims to the contrary.

In the days leading up to her testimony, Hill met not only with her lawyers but also with a media consultant named Molly Levinson, known as a top crisis counselor, problem solver, and reputation manager. The stakes were high: everything Hill said (and didn’t say) would be dissected and analyzed. But Levinson’s concerns extended beyond what Hill said to what she wore.

“Molly knew the congressional hearing room well.” Hill wrote in her memoir. “The air conditioning was cranked up and the temperature set low to accommodate congressmen in their layers of undershirts, dress shirts, and suit jackets so there would be no risk of sweaty armpits and brows beaded with perspiration.” Levinson warned “that as a more lightly dressed woman, [Hill] risked freezing.”

To effectively transmit the seriousness of her message to the viewers at home, Hill could not appear cold. Levinson made Hill practice grinding the balls of her feet into the ground to prevent shivering. She also counseled Hill to wear pantyhose to hide the goose bumps that might emerge as her body responded to the chilled congressional hearing room (based on available

photos, it’s difficult to gauge whether she followed this particular piece of advice). What Levinson offered was something like a finishing school for women in politics; rather than learning to stay afloat atop their heels, women now had to learn how to push their feet into the floor.

To the American public witnessing Hill’s testimony from the comfort of their homes, an involuntary shiver, as easily as a perspiring brow, might read as a sign of dishonesty. It was not only Hill’s reputation that was under threat but also her message: according to her testimony, Hill wanted to communicate nothing less than the “peril that […] we were in as a democracy.”

The emergence of mechanical air conditioning in the early 20th century made it possible to control thermal conditions on a previously unfathomable scale, ensuring that vaccines preserved their potency, bananas ripened at just the right time, and congressmen avoided unsightly pit stains. As the world outside became hotter a reflection of our impending climate catastrophe our interior worlds became colder. But the creep of climate control technology into nearly every aspect of our lives is only part of the story. What was also needed was a whole series of developments in the measurement of heat and its effects. Why, for example, did the business suit become the standardized unit for measuring how heat infiltrated the clothed body? And how could you safely study the impact of extreme heat without killing your test subjects? •

These questions began to find answers at the height of the Second World War. About as far away from the front as you

could get, a physiologist named Harwood Belding Woody to his friends and colleagues sat in a basement at Harvard University. There, he grafted together his own contribution to the war effort out of sheet metal and stovepipes. Belding was employed as a civilian scientist working for the US Army as part of Harvard’s Fatigue Lab.

The Fatigue Lab was a critical site for the study of exercise physiology, labor, and adaptation to extreme conditions, including both temperature and altitude in other words, conditions that went far beyond what might be narrowly defined as fatigue. The Lab was established in 1927, in the basement of the newly constructed Morgan Hall (named after the financier J. P. Morgan) at Harvard Business School, and ran for two decades. Test subjects included not only soldiers but also sharecroppers, miners, workers at the Hoover Dam, Olympic athletes, and even the scientists themselves (self-experimentation was far more acceptable in those days).

At the Fatigue Lab, Belding tested clothing and equipment for both the military and industry on human volunteers. The army in particular had heavily financed Belding’s research, in the hopes that his findings could help fortify American soldiers against heat-related illnesses like stroke and fatigue as well as cold-related conditions like trench foot and frostbite. Soldiers were offered up to uncomfortable thermal conditions, had their vitals taken and their comfort levels questioned. But humans, it turned out, were unreliable narrators of their own experiences. The same soldier, subjected to the same conditions, might provide a different response the second time around. Moreover, the soldiers

kept passing out under extreme heat conditions, which was both inconvenient for researchers and undoubtedly unpleasant for the soldiers themselves.

Inspired by a mannequin that he saw in a department store window, Belding’s solution to these problems was to construct what he called a manikin: a headless and armless automaton complete with an internal heating unit and a fan to distribute heat throughout its metal body. Manikins were built to emulate specific physiological functions of the human body; in this case, to sense heat. Two years later, Belding refined his rudimentary design with engineers at General Electric to build an electroplated, copper-skinned manikin transected by a single electrical circuit. The various parts of the “Harvard Copper Man,” as he came to be called, were created using clay molds produced by the Connecticut-based sculptor Leopold Schmidt. The measurements for these manikins were based on anthropometric measurements taken of male army recruits.

Thermal manikins could also be fitted with clothing, which allowed researchers to test how the things we wear mediate thermal sensation and comfort. Given that most humans are nearly always wearing some kind of clothing (except for when we’re bathing or making love), the effect of various textiles and layers on how we experience heat was and has remained an important thing to study especially given that clothing (taking it off, putting it on, changing it) represents a straightforward way of adjusting our thermal conditions.

Though hardly fashionable as a group, thermal researchers nevertheless became highly sought out as clothing designers. The Yale-trained physicist Adolf Pharo

Gagge, for example, helped to redesign the outfits worn by Air Force pilots, initiating a shift from the use of natural fibers to artificial materials that better maintained thermal comfort as aviators navigated intense atmospheric conditions. Gagge’s expertise was in physics; he served as chief of biophysics at the Aeromedical Laboratory at Wright-Patterson Air Force, then at the Human Factors Division Directorate (also in the Air Force), and finally, as manager of what was rather sinisterly described as “cloud physics and weather modification” for the Secretary of Defense.

Around the same time that Belding was experimenting with his manikins, Gagge developed a unit for measuring thermal insulation that he called the clo. After acquiring his own manikin from General Electric, Gagge began to assess the insulative properties of a range of clothing ensembles. One clo was standardized as the insulation provided by a business suit and cotton underwear. By contrast, pantyhose only provided .01 clo, and a long-sleeved T-shirt and tie provided .29 clo.

Gagge’s use of the business suit as the standard measure for insulation was deliberate: to his mind, it was familiar to the general public and therefore a readily available reference. But while the figure of the suit-clad 1940s human might have been widely recognized similar to the way that we might all recognize a firefighter or police officer it only represented a very small portion of American society: one that was predominantly male, white, and white-collar.

So now we’re finally back to the business suit and the pantyhose. And we only have to think back to Fiona Hill’s description of preparing herself to testify before

the House Intelligence Committee to understand how Gagge’s research shaped the climate of Congress a climate built for a man in a suit, or more precisely, a manikin in a suit.

The clo was developed as a tool for better understanding thermal conditions and increasing comfort. Yet, the decision to take the business suit as the fundamental unit for insulation resulted in the standardization of thermal conditions that made certain kinds of bodies comfortable at the expense of others.

In the early 1960s, Cold War anxieties about chemical warfare provided a new stimulus to thermal manikin research. The Soviets and their allies, it was feared, had built large warehouses stockpiled with chemical munitions. During World War II, the US armed forces had developed certain forms of protective clothing. But the effectiveness of troops while wearing this complicated and heavy outfit which included a gas mask, long underwear, a buttoned-up combat uniform, cotton gauntlets, long socks, and a rubberized overboot on top of standard combat boots was questionable. Experiments conducted with soldiers in climate-controlled chambers revealed that at high temperatures, the thermal conditions produced by wearing this baroque outfit could actually kill troops more quickly than chemical exposure. Manikins were once again utilized in an effort to develop lightweight materials that might offer chemical protection while avoiding overheating.

I was reminded of this Cold War research in July of 2022. While doomscrolling through my social media feeds, I came

across a photograph of Chinese health workers encased in biohazard suits, delivering COVID-19 tests in the midst of a prolonged heatwave. The suits were meant to protect the health workers from infection. But they also caused them to overheat. A friend who worked in Sierra Leone during the recent Ebola epidemic described a similar dynamic, where suited-up doctors and nurses began to suffer from heatstroke in the midst of their long shifts. To avoid this fate, these Chinese health workers had taped popsicles (the ones that come in plastic wrappers) to their suits. They hoped that these frozen desserts would cool them down. A bit of cold comfort, indeed.

Hervé Guibert

Ombre chinoise, 1979

Vintage gelatin silver print

© Christine Guibert / Courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris

“SIR, YOU DO REALIZE I AM 9-1-1?”

On the lives and afterlives of California’s firefighters

by Jaime LoweShawna Lynn Jones was 22 years old when she was dispatched to fight the roughly 10-acre Mulholland Fire from conservation camp

Malibu 13. It was February 25, 2016, and after serving eight months following a probation violation from a 2014 drug charge, Shawna was only three weeks shy of her release date. She and her incarcerated crew 13-3 were first to arrive on scene.

This was not like their usual assignments maintaining Malibu fire roads for multi-million-dollar estates and ranches. This was an actual fire. They hiked in, cut line, and worked through the night and early morning to put out the flames. By dawn, the catastrophic event was not the fire; it was that Shawna had been struck by a boulder and lay lifeless on a steep incline of the Santa Monica mountains.

In my book Breathing Fire, I investigated Shawna’s life and her death and the stories of the more than 200 women who worked on all-female crews as part of California’s incarcerated firefighting system. Since the book came out, I have given countless talks and lectures. What I repeat over and over is something I’ve learned from people in the field: firefighting is one of the most physically and mentally demanding jobs. Doing it while incarcerated is nearly impossible. Incarcerated fire crews aren’t just responsible for fire. They respond to mudslides, floods, blizzards and, as recently as February, were tasked with shoveling and clearing snow in the San Bernardino mountains for stranded residents. They are on the front lines of the climate crisis. One of the many differences between civilian crews and incarcerated crews is that, after protecting California’s wildlands and neighborhoods built in high-risk fire zones, incarcerated crews return to the status of state prisoners: they’re confined to camp, monitored, and reprimanded by corrections officers. The women, and thousands of men, who make up incarcerated crews work for dollars a day. Upon release, they’re largely forgotten. What started as a portrait of Shawna Lynn Jones, whose death shocked me, grew into an investigation of California’s prison

system, its fire fighting brigades, and personal histories of the women who knew Shawna and the system that killed her. I wanted Shawna to be recognized by the community she served. I wanted people outside of the prison system and beyond her immediate family to know who she was and what she did: that she wanted to join the forestry service when she was released; that she had an absurdist sense of humor; that she skateboarded throughout the Antelope Valley; that she loved her mom; that she rescued puppies and stole food for them; that she was a whole person, more than just her sentence. I wanted to write about Shawna Lynn Jones because I wanted to give her an afterlife.

Books are fixed objects, but they, too, have an afterlife. Because of the book, I talk regularly with those who were in the incarcerated firefighting program and people who are imprisoned. They hear me on the radio or TV. If they’re incarcerated, it’s harder to get the book hardcovers aren’t allowed in prison because California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) believes that they can be used as weapons. But my book has continued to circulate through the firefighting community. Last year I got an email from a man named Jason Hodge who, for roughly 20 years, had worked for the Ventura County Fire Department and as management on largescale incidents as a Federal Wildlands Firefighter. The subject of his email was “Shawna Lynn Jones.”

When Hodge wrote to me, it had been six years since Jones died. There was still no official resolution about Jones’s death from the Los Angeles County Fire Department, Ventura County Fire, Cal Fire, or CDCR. Several women who were at the scene had

told me there was another crew above them and that, even though the fire was contained and relatively small, rocks and loose soil fell on them from above. A falling boulder fatally struck Jones in the head. Her mom, Diana Baez, received no compensation from the state because it didn’t consider Jones a firefighter.

“First off, I believe her death was our fault,” Hodge wrote in an email to me. He and his crew of civilian firefighters were “careless and arrogant” because it was a small fire in February with no drought conditions. From that day forward, Hodge continued, his “life’s been a bit of a nightmare. A lot of it is still very raw to me. I’ve also spent years trying to get basic help from my department and it’s failed me miserably.” He included his phone number and said he wanted to talk. I wanted to hear his perspective that of a civilian firefighter. Most aren’t willing to share details of deaths like Shawna’s. In searching for answers about her death and about why and how the incarcerated fire camps existed, I also found neglect and exploitation coursing through the civilian fire infrastructure. One of the women I profiled whose firefighting career started at Malibu 13 ended up on a Hotshot crew, and then on Helitack crew. As part of the federal brigades, her status was classified as seasonal. She had no job security, health insurance, or pension. Just last year, the Biden-Harris administration raised the minimum wage of federal wildland firefighters to $15 an hour.

Last June, CalMatters, a nonprofit news organization that focuses on California, released a four-part investigation into Cal Fire and mental health. In it, they found that, “with too few firefighters to

cover all the fires, firefighters are on the front lines longer, with shorter respites at home. Some battle fires for months at a time.” The report included accounts from fire station leaders who are witnessing an unaddressed epidemic of PTSD and suicidal thoughts among their crews. Cal Fire does not collect any data on suicide or PTSD within its ranks and never has, despite having ample reason to. Firefighters are 40 percent more likely to take their own lives than the general population; in another study conducted in 2019, co-authored by former federal firefighter Patricia O’Brien, of more than 2,600 wildland firefighters surveyed, about a third reported experiencing suicidal thoughts; and nearly 40 percent said they had colleagues who had committed suicide.

When I called him, Hodge was forthcoming about his condition. He told me that he experienced suicidal ideation regularly. “They finally got me diagnosed with moderate to severe PTSD,” he said. “I started taking medication.” But, he explained, he has to pay out-of-pocket for psychiatric care.

He’d just gotten back from three weeks doing fire logistics in New Mexico and said that he was aware of the risks he was taking in talking on the record about his situation. He knew that he could have stayed silent, worked two more years, and retired. He feared losing relationships within the field and opportunities for advancement in his career. “You’re always afraid there will be repercussions,” Hodge said. He told me he wants to continue working fire long after he retires, but that he feared he wouldn’t be allowed to because of the stigma attached to mental health issues. Firefighters have long cultivated an air of stoicism. But a

combination of fatigue, intensifying fires, and increasing workloads have left many crews understaffed. “Then it would have been the same for everyone else, and I’m just sick of us failing ourselves,” Hodge said. “Our world has changed, and we have not changed with it. The stress is going to get higher, and it’s going to get worse before it gets better.”

Hodge needed someone to talk to about the day Jones died. He described the still-smoldering mountains stumps and roots glowing orange. He was standing a few feet above Shawna and three of the women on Shawna’s crew, joking with them. Hodge noticed another crew 20 feet up the mountain. “I had no idea who was up there. But they kept knocking rocks loose. And so, there were small rocks falling, and someone says on the radio to be careful because someone’s working up top. Well, first off, that’s fucking negligence,” Hodge said. He heard a crack, the sound of the boulder hitting Shawna’s helmet; then screaming, the sound of her crew’s reaction. “I ran down and Shawna had fallen somewhat down the hillside when it hit her. And then me and the other inmate, we both pulled her up and started cutting her gear off to do CPR. And as soon as I felt her head, I knew it was bad. I knew her skull was broken.”

Hodge told me that, after they had witnessed Jones’s death, the department “didn’t bother to put us out of service. For some firefighters, trauma is a result of a single incident; for others, it’s an accumulation of a lifetime of service. For Hodge, it seemed to be both. “I do see five or six big fires a year. And I like it. And I want to keep doing it for a long time, even after I retire. But the system itself prevents me from healing at

this point,” Hodge said. He told me about how he ignored symptoms of PTSD after Jones’s death he was claustrophobic, he couldn’t get an MRI because of the tight enclosure, and after a lifetime of surfing, he could no longer swim with his head underwater. “I just couldn’t find a lot of peace in my mind,” he said. Every now and then, he searched Jones’s name and didn’t see any lawsuits or follow-up. “It was a fire in February, which we weren’t expecting, and we weren’t taking it seriously.” He went on: “At least if it was me who got killed, my wife would get a quarter million dollars or something.”

Two years after Jones’s death, Hodge was on a similar emergency response in which he administered CPR to a woman who suffered similar injuries to Jones. She also died. “I grabbed her head, and as soon as I did, the back of my fingers just went into her skull. And it’s the same thing that happened with Shawna, I had the exact same feeling,” Hodge said. It instantly took him back to the Mulholland Fire and Jones’s death. He called in sick; drove six and a half hours home to his wife in San Francisco; canceled his next shift; tried to drive back to Ventura but couldn’t bring himself to start his truck. “I had a panic attack,” he said. Hodge called the Employee Assistance Program, a counseling hotline for county workers. According to Hodge, when he first called, no one answered. He left messages. No one returned his call. When he did get through, the person on the other end of the line told him that the first available appointment was in four to six weeks. When Hodge told the operator he was suicidal, the operator suggested he call 9 -1-1. “Sir, you do realize I am 9 -1-1?” Hodge said. “Those are the last people

I wanted to see.” That’s part of the problem, Hodge explained. The state’s strategy in dealing with the mental well-being of its firefighting brigade is to rely on peer counseling. “You don’t want to tell the guys that you work with that you’re going crazy,” Hodge said. “You feel so pathetic. You feel like you failed.”

Hodge knows that climate catastrophe means fires will only become more frequent, bigger, and more intense, and fire agencies municipal, state, and federal are unprepared. California’s worst fire season on record was 2020, with more than 8,600 blazes taking 33 lives and burning four percent of the state. Megafires have been replaced by million-acre “gigafires.” The United Nations estimated that highly devastating fires worldwide could increase by 57 percent by the end of the century. “We’re still putting Band-Aids on,” Hodge said. The department, according to Hodge, hands people in crisis stacks of paperwork and routinely denies Workers’ Comp claims, especially ones rooted in mental health. “The county told me to download a form for an injury which, when you read it, asks what caused the injury. For example, ‘struck against concrete.’ Then it asks you how you can avoid this injury which at that point…” He trailed off sounding frustrated all over again. Hodge recognizes that he works for one of the better fire departments in the country and yet he still can’t get the help he needs. He said that he likes being a firefighter friends and relatives call him a hero but in reality, he added, “I just have the best seats for the apocalypse.”

When Shawna was riding in the fire buggy to the Mulholland Fire, she had just started to train as a sawyer, the lead position on crew responsible for holding the

chainsaw and cutting branches and growth to create the containment line. She had asked her captain to train as a sawyer so that, when she was released, she could list the experience when applying for forestry jobs. Being a sawyer is the hardest position on crew because of the weight of the chainsaw and because each cut creates a path for the crew to hike. As the bus wound its way up the circuitous mountain roads, Shawna turned to her crewmate and said she was scared. She had never seen fire before.

Hervé Guibert

Thierry à la fenêtre de la Sacristie, Santa Catarina, 1983

Vintage gelatin silver print

© Christine Guibert / Courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris

SOWING THE FUTURE

A posthumous excerpt from Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties honoring the life of Mike Davis

with an introduction by his coauthor Jon Wiener

Mike Davis started talking about writing a movement history of L.A. in the sixties a long time ago, in 2007. In 2014, when he asked me to co-author the book, he said he didn’t want this to be a trip down memory lane for the aging activists of yesteryear; nor did he want to tell the young activists of today that they should follow the splendid example set by our generation. He did want to recover a history that had been mostly overlooked by the chroniclers of “the sixties,” and twisted beyond recognition by the forces of the right. He wanted to connect past and future. He also said that writing it together would be “a blast.” I immediately said “yes.”

Mike passed away on October 25, 2022. What follows is the Epilogue to the completed project that we wrote together, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties more than 600 pages about the movements of people of color, many of whom were surprisingly young, along with participants in the antiwar movement, the women’s movement, and gay liberation, as well as counterculture institutions, starting with the underground press. All faced the unending efforts of the LAPD to crush them. But as John Densmore of The Doors (whose song gave us our title) told us about today’s movements: “the seeds were planted in the sixties.” Herewith, some of the fruit of those seeds.

— Jon WienerThe Yorty era ended with a whimper in the May 1973 general election. A year earlier the mayor, who had already run for more offices than any politician in American history, had astounded political observers by launching his twentieth campaign this time for the Democratic presidential nomination. Utterly unknown in most of the country, he campaigned on promises to stop school busing, continue the war in Vietnam, and make George Wallace his running mate. The L.A. Times disgustedly accused him of making L.A. “a national joke.” In the event, he won only 1.4 percent of California’s votes cast, coming in far behind Shirley Chisholm, the first Black woman to contest a presidential primary. Elsewhere, Yorty was almost invisible; in Rhode Island, for instance, he received exactly six primary votes. Despite his buffoonery and exorbitant malapropisms (in a national debate, he introduced himself as “mayor of the third largest city in Los

Angeles”), he still managed to win a majority of white votes in his mayoral rematch with Tom Bradley. But Bradley increased his own proportion of the white vote from 37 percent in 1969 to 46 percent in 1973 and won 51 percent of a Chicano vote, which had gone strongly for Yorty in 1969. The result was a four-point victory over Yorty.

In key respects, however, this was a different Bradley than the progressive candidate of 1969. Although the core cadre of the old coalition middle-class Blacks, Jews, and Japanese Americans from the Tenth Council District remained influential as allies and advisors, the conduct of the campaign itself was turned over to a clique of powerful white business leaders and political professionals. Nelson Rising, a corporate lawyer and future mega-developer who had managed John Tunney’s sensational 1970 Senate race, became campaign chair, while Max Palevsky, the fabulously rich founder of SDS (Scientific Data Systems), coordinated the finances, including his own series of large loans to the campaign. Together they convinced Bradley to hire David Garth, who had invented the modern television-based political campaign in 1965 on behalf of New York’s John Lindsay. Garth’s strategy, as Raphael Sonenshein later explained in Politics in Black and White: Race and Power in Los Angeles (1993), inverted the key elements of the 1969 crusade. “It had become more professional and less ideological. The emphasis would be on mass media, backed by grassroots campaign, rather than the other way around.”

The ad blitz focused on Bradley’s police career and his political moderation. A very reserved and well-spoken man, Bradley radiated strength and conciliation while Yorty simply acted berserk.

His attempts to race- and red-bait Bradley gained less traction than in 1969, in part because the streets and campuses were tranquilized. The last big antiwar demonstration, protesting Nixon’s second inauguration, was held downtown on January 20th and a week later a ceasefire was called in Vietnam. At the same time, the Nixon administration suspended the draft. Robert Hahn, an education professor at Cal State L.A., announced that he was ending the silent vigil he had conducted weekly for seven years in protest of the war. Meanwhile, the L.A. Panthers, US, SNCC, SDS, the Berets, Che-Lumumba, the Chicano Moratorium Committee, and even the Peace Action Council were now either extinct or moribund. The threat of school busing, on the horizon as the federal court finally moved toward resolution of the ACLU’s 1963 “Crawford” lawsuit, roiled white voters, particularly in the Valley, but Barth ensured that the Bradley campaign steered clear of controversies about school integration. Likewise, when Bobby Seale in Oakland endorsed Bradley, the candidate publically rejected his support.

Bradley’s victory was unique and would remain so for many years: a Black mayor elected by a multi-racial coalition in a city whose Black population share was actually declining. The greatest rewards, however, did not go to the neighborhoods or jobless youth, as the 1969 campaign had promised, but to white men in office towers gathered around ambitious plans for downtown redevelopment and multi-billion-dollar expansions of LAX and the Port. Bradley’s election ended the organic crisis of elite governance that had arisen in the wake of Yorty’s surprise victory in 1961 and the schism between liberal Westside and

conservative Downtown power structures. With his electoral base stabilized by liberal rhetoric and patronage (mediated by his arch-supporter Rev. Brookins), his relationship with Westside moguls, big developers, major banks, and the Times’ Otis Chandler grew more intimate and eventually more corrupt over the course of twenty years in office. In historical retrospect, his greatest accomplishments were not attacking residential segregation or directing public investment to have-not neighborhoods but rather the rebirth of Downtown property values and the creation of a state-of-theart infrastructure for the globalization of the metropolitan economy in the 1990s. Despite public expectations, he was no more successful than the early Yorty in controlling the LAPD or changing its leadership, which continued to be passed on dynastically to proteges of Chief Parker such as Daryl Gates. Moreover the department continued to blackmail politicians and occasionally destroy their careers, as in the case of Maury Weiner, Bradley’s progressive conscience and deputy mayor, who was arrested in 1975 for supposedly groping an undercover vice officer in a Hollywood theater. Weiner’s real sin was not that he was gay but rather that he was still urging the mayor to tame the cops.

Although Bradley made a number of key Chicano hires at City Hall, he was soon accused of betraying his Eastside supporters by not endorsing Chicano candidates for the City Council, particularly for Edward Roybal’s old seat held by Gilbert Lindsay. (Only in 1985 and running in another, white-voter majority district would Richard Alatorre finally restore a Spanish surname to the Council roster.) Instead of fully integrating Chicanos into his

coalition, the new mayor gave priority to meshing his policies with the plans of the major power players in the business community who in turn guaranteed the campaign finances that made Bradley’s tenure unassailable. Otherwise, he might have been more vulnerable to political challenges within the Black community that arose from his “invasion” of the turf controlled by allies of Mervyn Dymally (now lieutenant governor) and Jesse Unruh. Their respective political bases in 1973 were roughly defined by Vermont Avenue. West of Vermont, Bradley support was rooted in stable Black working-class and middle-class neighborhoods whose relative prosperity was based on expanding public employment opportunities for which the mayor claimed much of the credit. East of Vermont, in the 1965 riot zone, Dymally loyalists represented a population was more likely to be badly housed, dependent on low-wage private employment, and served by the worst schools. Far from experiencing a community renaissance under the new regime, the riot zone neighborhoods in the 1970s lost the little ground they had gained through the War on Poverty and temporary youth employment schemes. Watts in particular, once a symbol of hope and Black pride, was now a pit of despair. In 1975, on the eve of the tenth anniversary of the uprising, L.A. Times reporters surveyed the district and came to the grim conclusion that conditions were considerably worse than in 1965. “Unemployment is now higher in the Watts area, welfare rates are climbing, and housing continues to deteriorate.” Ron Karenga, interviewed in prison, told the L.A. Times that “people view the 60s as a failure when in fact the 60s were not a failure but a transitional period in our long

struggle.... We can’t look at the temporary disarray that we find ourselves in and be dispirited.” Yet most of the people who talked to the L.A. Times were dispirited and expressed little hope that the Bradley administration, particularly in the absence of federal support, would reverse the decline. As Walter Bremond, the former chair of the Black Congress, put it: “the system whipped the shit out of us.”

By the early 1980s, moreover, a wave of plant closures had shuttered the auto assembly plants, aluminum mills, steel plants, and tire factories that had symbolized greater L.A.’s prowess as the nation’s second largest manufacturing center. Although thousands of older white workers were victims of this industrial collapse, it hit especially hard at the young Blacks and Chicanos, many of them Vietnam veterans, who thanks to federal consent decrees had recently acquired access to more of these unionized high-wage jobs and in some cases risen to union leadership. Many leftists in the 1970s had envisioned the big plants as the new power bases for continuing the Black and Chicano liberation struggles. Deindustrialization, whether or not an inevitable response to global competition, was the asteroid that destroyed Marxist dreams. City Hall, so proactive on behalf of exporters, land developers, and the financial sector, did nothing to stanch the hemorrhage of good jobs. (Bradley and the Council, for instance, could have led a coalition of the region’s industrial cities and suburbs to pressure Sacramento and Washington.)

Meanwhile, gang violence, largely quelled in the wake of the ’65 rebellion, returned to the streets of South Central in a new and more deadly form. A few months

after Bradley’s inauguration, investigators were warning his office of the existence of 27 “chapters” of a new, heavily armed gang nation that called itself the Crips. Twelve additional gangs later to be known as Bloods had been formed in self-defense against the expanding Crip empire. Gang membership would steadily increase through the 1970s, then grow exponentially in 1980s as crack cocaine, imported from Colombia and retailed by neighborhood gangs, became the ghetto’s alternative economy. The connection between the decline of Black radicalism and rising gang violence may have escaped the notice of the white media but was widely acknowledged and mourned in the community. The Crips were indeed, as Cle Sloan titled his film made in the wake of the 1992 uprising, the “Bastards of the [Black Panther] Party.”

But it was LAUSD that remained ground zero in the struggle for equal opportunity. Waves of immigration from Mexico, as well as Central America and South Korea, reshaped the city’s demography and added their own baby boom to the school-age population. But new immigrants were typically years away from citizenship, so a chasm opened up between the active electorate and voteless immigrant parents. White voters, their children now grown, had little inclination to vote for school bonds but were enthusiastic for Proposition 13 in 1978, which ended the financing of schools through local property taxes and inaugurated an era of permanent fiscal stress and declining quality of education. The conservative Valley was the cradle of this statewide tax revolt and soon became the principal school desegregation battleground. The Valley-based New Right activists who in 1976 organized

Bustop, an anti-busing group that claimed 30,000 members, went on to win positions on the School Board and even a seat in Congress. They also helped lead the rebellion of local homeowners’ associations against apartment construction and, in the 1994 election, were catalysts in the passage of anti-immigrant Proposition 187 (“Save Our State”) ultimately ruled unconstitutional which among other provisions ordered school districts to expel undocumented children. Their underlying political raison d’être, reincarnated today in the Trump administration, was to deny immigrants and children of color the opportunities that high levels of public spending on education in 1950s California had provided for their own kids.

The fires of April 1992 that followed the not-guilty verdicts in the trial of the cops who beat Rodney King illuminated the city’s continuing landscape of inequality. South and East L.A. were still policed ruthlessly by the LAPD, but the uprising of angry Black youth and poor Latinos also presented a price tag for the failures of reform in the 1960s. From this perspective, one might conclude that all the dreaming, passion, and sacrifice of that era had been for naught. But the sixties in Los Angeles are best conceived of as a sowing whose seeds grew into living traditions of resistance. Movements rose and fell to be sure, but individual commitments to social change were enduring and inheritable. Thousands continued to lead activist lives as union organizers, progressive doctors, and lawyers, as school teachers, community advocates, and city employees, and, perhaps most profoundly, as parents. Memories of Black power, draft resistance, the highschool blowouts in South Central and the

Eastside, the grape boycott, the Artists’ Peace Protest Tower, Gidra and the Asian new left, the Free Angela movement, the mass arrests at Valley State in the struggle for Black studies, the Black Cat Tavern

“riot,” the women’s movement, the 1970 Teamster wildcat strike, the endless battles to free Venice and free the Strip all of this was transmitted intergenerationally, sometimes providing icons of protest during the massive renewal of labor activism and immigrant rights organizing in the 1990s.

The turning point came after California voters approved Prop 187 in 1994. It won almost 60 percent of the votes statewide and passed in L.A. County by a 12-point margin. But it spurred a massive Latino backlash. Miguel Contreras, a son of migrant farm workers who had picked grapes as a child, became the first Latino head of the County Federation of Labor. He set to work making unions a vehicle for mobilizing L.A.’s vast Latino community. A massive door-to-door registration drive was followed by a get-out-the-vote operation in support of progressive candidates allied with Latino labor. They reshaped the City Council and L.A.’s delegations to the state legislature and Congress, and soon California was solidly Democratic. In L.A., labor organized the Living Wage campaign, which in 1997 became one of the first in the nation to succeed at raising the incomes of workers on publicly funded projects. Next came the Latino-led Justice for Janitors campaign, which, after protracted struggle, mass arrests, and police beatings, won a huge citywide strike in 2000. And the LAPD was finally required to change its ways in 2001. After decades of litigation by the ACLU and protests

organized mostly by activists in South L.A., the federal courts forced dozens of major reforms on the department and imposed a court-appointed monitor to supervise compliance. The decree wasn’t lifted until 2013. And history was made in the streets: on May Day in 2006, half a million people marched down Wilshire Blvd demanding rights for undocumented immigrants. Most of them were Latino and most were young. The march had been called by labor unions and immigrant rights groups and endorsed by the pro-immigrant Cardinal Roger Mahony and the city’s first Latino mayor, Antonio Villaraigosa. On January 21, 2017, the day after Trump was inaugurated, 750,000 protested downtown at the L.A. Women’s March perhaps the largest in L.A. history.

But the 2019 L.A. teachers’ strike was perhaps the most dramatic example of the renewal of activism. A coalition of the classroom and the community, it focused on the same issues of overcrowded schools and educational disinvestment (now aggravated by the drain of resources to charter schools) that had contributed to the student uprisings in 1967 – 69. Moreover, thousands of the Latino students who boycotted classes and joined teacher picket lines were proudly aware that they were following in the footsteps of Sal Castro, Gloria Arellanes, Bobby Elias, Carlos Muñoz and all the others who had made time stop in March 1968. The union then capped its victory by recalling L.A.’s most irrepressible sixties veteran, Echo Park’s Jackie Goldberg, from retirement and electing her to the School Board where she had fought so hard for integration and quality education thirty years earlier.

For more than a half century, the right

has waged a relentless campaign against the goals and achievements of the sixties’ movements for racial, social, and economic equality. From Reagan to Trump, there has been an endless hammering away at caricatures of dopey hippies, traitorous peace protestors, bra-burning feminists, dangerous Black radicals, and commissars of political correctness.

However, as this book’s two authors have discovered in myriad conversations with their students and other young comrades, this rewrite of history from the standpoint of wealthy white men has had minimal impact on the social consciousness of the young people of color who are Los Angeles’ future. If anything, their own experiences of nativism, discrimination, sexual harassment, and blocked mobility ensure that they will be genuine successors to grandmothers and grandfathers who raised their clenched fists and demanded power to people so long ago. To keep that circle unbroken, this book was written.

Excerpted from Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, Verso, 2020 © pp. 631–638

Hervé Guibert

Autoportrait, rue du Moulin-Vert, porte vitrée, c. 1986

Vintage gelatin silver print

© Christine Guibert / Courtesy Les Douches la Galerie, Paris

It is the first day of the month of nivôse in the French revolutionary calendar. The year is CCXXXII. Nature converged with revolution to create this calendar. Time started again, anew, according to reason and nature and the intentions of history. It was Year I of a new order, one in which there was collective time, human time, no gods or masters, tyrants abolished, kings done away with and their queens too, no longer a divine order of the universe: our time, our space, a difference between temps voulu and temps veçu, with nothing but the changes of nature marking the changing of the hours, the days, the years. The short-lived calendar of the revolution was

formed of months of three weeks of ten days, of days with ten hours, of hours with a hundred minutes, of minutes with a hundred seconds; a calendar of natural and attractive names: the calendar of Jacobin history. Days that ended in zero were assigned to an agricultural implement. Days ending in five were assigned to an animal. All other days were assigned to a plant or a mineral.

Nivôse is the month of snow, though this year there has not been any snow yet. Mist and frost have passed, while rain and wind arrive, and then later, seed will be sown, and after there will be blossom, harvest, heat, and fruit leading to fine vintage. That is all attendant; for now, it is a matter of keeping warm and keeping the wolf from the door. Three stoves are lit daily, sometimes a fourth. The collection of firewood is endless. I sometimes hear nivôse, which comes from nivosus, abundant in snow, as névrose, a psychic trouble characterized by conflict, hysterical or obsessional, according to the psychic structure of the subject.

TOURBE (peat): Today is the day of peat. When the land is set on fire to clear for new growth, it is not the peat that burns but the blue grass or the heathers rooted in the peat. For hearth-fires it is cut by hand, left to dry in the sun, then stacked; burning, it smells like bacon and grass, sour and sweet at the same time. Today is the shortest day, the winter solstice, associated with Apollo, Dionysus, Mithra (the holly and the ivy, the mistletoe). The young sun was born on this day, the fire of the earth, the sun king, son of the goddess, and he brought with him all the promises of the year to come. Another calendar, here on my writing-table, measures the passing of time: the almanach du facteur. Now I buy this almanach du

facteur myself but my neighbor Marcelle, for whom I had both the pleasure and burden of being her “second daughter,” used to give one to me every Christmas Eve. She kept all her almanac calendars, each year marked with the weather, the sowing, and planting, or the gathering, as well the date of the deaths of the dogs and cats all buried in our gardens. When we did not live here all the time, Marcelle always laid a fire in our hearth, in time for our arrival in winter. The house was always cold.

HOUILLE (coal): Coal or coke, houille, is between lignite and anthracite, sometimes poisonous. The silicone death of miners. Germinal. Let them burn, those who oppose us, they said, and they cut down the trees of the grand canal at the palace of Versailles for firewood. Later, they said burn Paris, and later still, others lied, saying it was the women who had done it, the pétroleuses, with their canteens and guns, their bombs and their flames. Later still, cars were set on fire, businesses and public buildings blazed.

BITUMEN (bitumen): Bitumen is black and viscous. Bitumen binds asphalt. Exposure to its fumes is linked to respiratory effects, asthma, bronchitis, to cancer. Inhaling its vapor produces drowsiness and vertigo. The saints and martyrs, the dead, those who died for their devotion, their beliefs, the croyant /es, measured time in the Christian calendar with its distinction between sacred and profane days, indicating the way time should be spent according to the dictates of the church. Such a parade of saints and martyrs but sometimes, on certain days, they were replaced with “great men,” sunkings, for example (after Apollinaire: soleil

cou coupé, sun corpseless, sun cutthroat, the sun a severed neck, solar throat slashed, and let the sun beheaded be, and so on), or other illustrious figures, even with Voltaire, imagine!