BOOKSOFREVIEWANGELESLOS IssueHigh/Low29NO.QUARTERLYJOURNAL 9 781940 660769 5 1 2 0 0 > ISBN 978-1-940660-76-9$12.00 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS QUARTERLY JOURNAL : HIGH/LOW NO . 29

BuzzFeed News, 29 Best Books of 2020 “A quest toward wonder re-envisioning,and a quest to go beyond, as the best poems do, the ‘edge of thinking.’”

To place an ad in the LARB Quarterly Journal, email adsales@lareviewofbooks org

—Roxanne Dunbar-Ortz, author of An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States “An accessibleunusuallyprimer on immigraton law and a valuable guide to the ways it currently works to perpetuate an excluded underclassimmigrantwith diminished rights.”

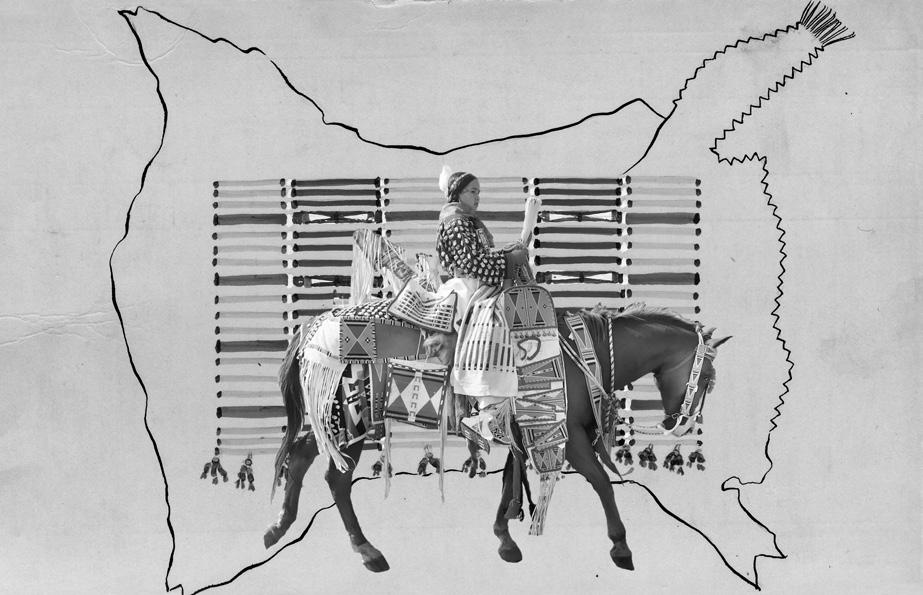

PUBLISHER: TOM LUTZ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: BORIS DRALYUK MANAGING EDITOR: SONIA ALI CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: SARA DAVIS, MASHINKA FIRUNTS HAKOPIAN, ELIZABETH METZGER, CALLIE SISKEL ART DIRECTOR: PERWANA NAZIF DESIGN DIRECTOR: LAUREN HEMMING GRAPHIC DESIGNER: TOM COMITTA ART CONTRIBUTORS: JA'TOVIA GARY, ROSEMARY MAYER, REYNALDO RIVERA PRODUCTION AND COPY DESK CHIEF: CORD BROOKS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: IRENE YOON MANAGING DIRECTOR: JESSICA KUBINEC AD SALES: BILL HARPER BOARD OF DIRECTORS: ALBERT LITEWKA (CHAIR), JODY ARMOUR, REZA ASLAN, BILL BENENSON, LEO BRAUDY, EILEEN CHENG-YIN CHOW, MATT GALSOR, ANNE GERMANACOS, TAMERLIN GODLEY, SETH GREENLAND, GERARD GUILLEMOT, DARRYL HOLTER, STEVEN LAVINE, ERIC LAX, TOM LUTZ, SUSAN MORSE, MARY SWEENEY, LYNNE THOMPSON, BARBARA VORON, MATTHEW WEINER, JON WIENER, JAMIE WOLF COVER ART: WENDY RED STAR, CATALOGUE NUMBER 1950.74, 2019, PIGMENT PRINT ON ARCHIVAL PAPER, 18 X 28 INCHES. COURTESY OF THE ARTIST AND SARGENT'S DAUGHTERS. INTERNS & VOLUNTEERS: THOMAS WEE, EMILY SMIBERT Te Los Angeles Review of Books is a 501(c)(3) nonproft organization. Te LARB Quarterly Journal is published quarterly by the Los Angeles Review of Books, 6671 Sunset Blvd., Suite 1521, Los Angeles, CA 90028. Submissions for the Journal can be emailed to editorial@ lareviewofbooks org. © Los Angeles Review of Books. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Visit our website at www lareviewofbooks org Te LARB Quarterly Journal is a premium of the LARB Membership Program. Annual subscriptions are available. Go to www.lareviewofbooks.org/membership for more information or email membership@lareviewofbooks org Distribution through Publishers Group West. If you are a retailer and would like to order the LARB Quarterly Journal, call 800-788-3123 or email orderentry@perseusbooks.com.

ConversationsNew

—Mary Szybist, author of Incarnadine “Historian Gretchen Eick has ofabiographyemployedtowritebrillianthistorytheUSgenocidal policy of eliminaton or assimilaton.”

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS no. 29 QUARTERLY JOURNAL HIGH/LOW unpress.nevada.edu Start “Murray makes it impossible for readers to maintain the shelter of distance from politcs... It is absolutely essental reading.”

The New York Review of Books

essays 7 WHERE GILDED AGES GO TO DIE: HOLLYWOOD RETURNS TO THE 1930S AND ’40S by J.T. Price 23 SEX — EVERYTHINGAND ELSE by Katherine Angel 55 WHY VIOLENCE GOES VIRAL by Brian Lin 72 PULLING by Rachel Genn 87 "LITERATURE IS A MAXIMTRIBUNE":GORKYANDTHEKLAVIDAGROSSSTORY by Donald Rayfield 114 COLLECTING STEPHEN LEACOCK by Andrew Nicholls 127 JEFF TWEEDY WILL TEACH SONGWRITINGYOU by Alex Scordelis fiction 43 QUEEN'S RUN by Gar Anthony Haywood poetry 20 TARKOVSKY by Michael M. Weinstein 40 TWO POEMS by Victoria Chang 84 THE BLADES by Emily Jungmin Yoon 111 FACING IT by Forrest Gander & Ashwini Bhat 123 MY FATHER FINDS HOME THROUGH THE BIRDS by Threa Almontaser 139 ATE MOON by Tyree Daye interview 31 PAUL R. WILLIAMS IN LOS ANGELES: A CONVERSATION WITH JANNA IRELAND by Erin Aubry Kaplan NO . 29 QUARTERLY JOURNAL : HIGH/LOW CONTENTSFROM THE ENDLESSANGELES’MURDEROUSMOSTERAINAMERICANHISTORY,AVINTAGETRUECRIMETALESETAMONGLOSGLASSYTOWERSANDRIBBONSOFASPHALT brilliant“Jacobs’MarchAvailable2021chopsareondisplayin The Darkest Glare, a delightfully of-kilter true-crime tale. The prose is intimate, darkly funny, and crisp. This isn’t an old song in a new key, but an entirely new song about crime, fear, and a weird kind of redemption that could only happen in the general vicinity of Hollywood.” —RON BESTSELLINGFRANSCELL,AUTHOR OF THE DARKEST NIGHT

STANFORDstanfordpress.typepad.comsup.orgUNIVERSITY PRESS A Matter of Death and Life Irvin D. Yalom and Marilyn Yalom “An unforgettable and achingly beautiful story of enduring love. I will be thinking about this for years to come.”—Lori Gottlieb, New York Times bestselling author of Maybe You Should Talk to Someone Our NationNon-Christian How Atheists, Satanists, Pagans, and Others Are Demanding Teir Rightful Place in Public Life Jay “Timely,Wexlertrenchant, and tremendously engaging.” —Phil Zuckerman, author of Living the Secular Life NOW IN PAPERBACK Nothing Happened A History Susan A. Crane “Clever and funny and serious and illuminating. You won’t want to put it down.”—Marita authorSturken,of Tourists of History Identity Capitalists Te Powerful Insiders Who Exploit Diversity to Maintain Inequality Nancy “Entertaining,Leong accessible, and thought-provoking.”—NicoleBuonocorePorter,co-authorof Feminist Judgments Copy Tis Book! What Data Tells Us about Copyright and the Public Good Paul J. Heald “ T is book is so engaging and sensible. T is will sound ridiculous, but I can’t put it University—Sauldown.”Levmore,ofChicago Feral Atlas Te HumanMore-TanAnthropocene Edited by Anna L. Tsing, Jennifer Deger, Alder Keleman Saxena, and Feifei Zhou REDWOOD PRESS DIGITAL PUBLISHING INITIATIVE Explore now at feralatlas.org

ArchitecturalLynetteFilmmakerSerbiaWidderHistoryColumbiaUniversityClairWillsCulturalHistoryUnitedKingdom

JosephPortugalPhotographerR.Slaughter

Abigail R. Cohen Fellow English and Comparative LiteratureColumbia University Ersi WriterSotiropoulosGreeceMilaTurajli ć

Indeed, the current issue perfectly embodies LARB’s central aims — aims we’ve followed for 10 lively years: to break down traditional barriers and to encourage a rigorous yet openminded and soulful engagement with the broader culture. So what’s to feel low about? Simple. With this issue we’re bidding farewell to Medaya Ocher, LARB’s brilliant longtime Managing Editor, under whose imaginative and discerning leadership the Quarterly Journal became what it is: one of the most groundbreaking, consistently surprising, unfailingly rewarding literary venues in the nation. We take comfort in the knowledge that Medaya is moving on to bigger and brighter things, and though our world will be less luminous without her, we’ll make sure that the Quarterly Journal continues to shine.

— Boris Dralyuk, Editor-in-Chief, and Sonia Ali, Managing Editor

Abigail R. Cohen Fellow Visual YasmineEnglishUnitedArtistKingdom/NigeriaDeniseCruzandComparativeLiteratureColumbiaUniversityElRashidiWriterEygptLamiaJoreigeVisualAristLebanonAnaPaulinaLeeLatinAmericanandIberianCulturesColumbiaUniversitySkyMacklayComposerColumbiaUniversity

The theme of this issue is “High/Low” and, fittingly, we at LARB feel two ways about it. On the one hand, we’re truly floating high. The pieces in these pages tackle everything from fine art to the latest Hollywood productions from exciting, unusual angles, putting disparate genres and themes into fruitful conversation with each other. Here fiction and nonfiction, architecture and photography, songcraft and poetry, crime writing and comedy mingle freely without jostling for a loftier hierarchal position.

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

John Duong Phan East Asian Languages and ColumbiaCultures University João Pina Abigail R. Cohen Fellow

For further details about our Fellows and their work, the Institute and its mission, or our fellowships and how to apply for them, please visit our website at www.ideasimagination.columbia.edu. We encourage cooperation with partner organizations from the world of academia and the creative arts. is proud to announce its 2020 21 class of Fellows: The Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination is made possible by the generous support of the Areté Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, and Daniel Cohen, and with additional gifts from Judith Ginsberg and Paul LeClerc, Olga and George Votis, the EHA Foundation, and Mel and Lois Tukman.

Located at Reid Hall, home to Columbia Global Centers | Paris, the Institute hosts a community of scholars, writers, and artists whose work has the potential to transform the way we think about the world. A presidential global initiative of Columbia University, the Institute aims to foster collaboration across the creative arts and scholarly disciplines (including the humanities, social sciences, and theoretical sciences) through residential and short-term fellowships, workshops, conferences, exhibitions, and artistic events. Its primary goal is to enrich academic modes of presenting ideas by drawing together the scholarly and the artistic imagination.

AnonymousAbounaddaraFilm Collective WriterArudpragasamColumbiaUniversityKarimahAshadu

AnukSyria

—Nina Totenberg, Legal Affairs

Correspondent, National Public Radio “A treasured compilation of essays, interviews, and thoughts about one of the most important artists of the late twentieth century.”

—Richard J. Powell, author of Going There: Black Visual

www.ucpress.edu AMERICAN HISTORIES AND FUTURES “A welcome contribution to Native studies and the rich literature of California’s fi rst peoples.” —Kirkus Reviews “Her fi nal work gives readers a glimpse at the person behind the accomplishments.” —Hillary Rodham Clinton, former United States Secretary of State “Must reading for anyone interested in James Baldwin.” —Washington Post “Intensely local and satisfyingly global, it is thorough.”staggeringly —Matthew Frye Jacobson, author of Whiteness of a Different Color and Barbarian Virtues staggeringly “If you admired Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, you should love this book by Herma Hill Kay.”

Satire

Eric N. Mack, Key, 2020, assorted fabric, acrylic, felt, feathers, toweling, graphite, 46 1/2 x 45 in. (118.1 x 114.3 cm).

Photo: Steven Probert. © Eric N. Mack. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, and Morán Morán, Los Angeles.

7 In California in 1934, as dust clouds across the plains drew migrants west ward in droves, an outspoken socialist writer, Upton Sinclair, donned the man tle of the Democratic Party to run for governor. Te new flm Mank, David Fincher’s latest directorial efort, sug gests that Sinclair was favored to win the race, at least until the movie studios had their say. Tanks in large part to a series of faux-documentary shorts purporting to give newsreel testimony of voter prefer ences, Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPiC) movement fell short, and a revan chist attitude took hold: circle the wagons against the unwashed hordes. Today, under the shadows of California’s highway overpasses, tent WHERE GILDED AGES GO TO DIE: HOLLYWOOD RETURNS TO THE 1930S AND '40S J.T. PRICE ESSAY

Perhaps in recognition of the blend ing of Simon & Co.’s vision with Roth’s, the family surname is no longer “Roth,” as in the novel, but Levin, and it is through the Levins that we experience the creep ing changes to American norms under President Lindbergh, a prejudiced man dressed up as a media hero. In Te Plot Against America, initially subtle shifts in what the middle of the country will accept soon pitch toward the precipitous; simply seeing, through digital magic, President Lindbergh shaking Adolf Hitler’s hand — “like he’s any other fella,” as a friend of the family’s patriarch, Herman, puts it — immediately makes the skin crawl.

Te American Jewish family, middle class with hopes of a better tomorrow, is the heart and soul of the story, and the dramatic arc traces the way child can be turned against parent, sister against sister, the prosperous against those who identify with the victimized. Nearly every episode opens with a bravura sequence: chalk on asphalt outlines a child’s understanding of the war; Lindbergh’s aircraft zips across the skyline of a New York City rewound 80 years in time; a series of American presidential stamps transforms into an endless succession of Hitlers. Te signa ture systems-not-individuals storytelling technique that worked so well in Te Wire takes more than an episode to get rolling here; the frst episode, especially, lags, as the viewer grasps for a focal point among the profusion of characters they do not yet know. But things pick up.

Trough its depiction of an alternate 1940s USA, the miniseries comments

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 8 cities lurk, visceral evidence of a crisis in afordable housing, even as a new studio system has emerged under the banners of Disney, Netfix, Apple, and Amazon. Tose inside the studio gates earn sala ries sufcient to buy property, driving up the cost of housing and forcing the less fortunate from their homes, while those trapped in the gig economy are stuck in rental apartments. A housing system vest ed widely in rentals allows those who can aford it to become rentiers, perpetuating a vicious cycle in which much of the pop ulation can’t aford to own the foor be neath their feet. Maybe we should not be surprised, in our own time of radical inequality, that storytellers would turn with renewed vig or toward the 1930s and ’40s. In our col lective anxiety about what comes next, it makes sense to grapple with an era when the last gilded age gave out and radical politics came roaring to the fore. ¤ Perhaps no single fgure holds more sway in convincing Americans that Tis Is Just the Way It Is than a sitting US presi dent. Philip Roth intuited as much in his celebrated 2004 novel Te Plot Against America. Set in the immediate lead-up to what would have been the country’s involvement in World War II, this fc tion charts an alternate course wherein Charles Lindbergh, “that little man in the plane,” runs a successful campaign for president as the Republican nominee. Te six-part HBO adaptation by Te Wire’s David Simon and Ed Burns is an impres sive expansion of Roth’s tightly conceived narrative, with more developed parts for two supporting characters at the oppo site poles of a nuclear family: aunt Evelyn Finkel, whose every quaver of uncertainty plays out on Winona Ryder’s brow, and cousin Alvin Levin, the frebrand whose righteous indignation is communicated through Anthony Boyle’s gaze.

David Wittenberg, author of Time Travel: The Popular Philosophy of Narrative Edited by Costica Bradatan

Elizabeth Kolbert, author of The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, winner of the Pulitzer Prize NEW SERIES from Columbia University Press “These are the books we need right now: unorthodox, irreverent, forward-looking. Knowledge is no longer what it used to be, nor is book writing. This series is among the first to recognize that.”

Julia Kristeva“Tom

9

CUP.COLUMBIA.EDU “Intervolution is at once informative and thought-provoking—a fascinating exploration of the ever-narrowing gap between men and machines. Mark C. Taylor uses his own experience of chronic illness to probe some of the central questions of our time.”

Lutz is an explorer, a tinkerer, a connoisseur, a peripatetic scholar, a prodigious reader, and a beguiling writer. His Aimlessness invites us to ask how, when, and above all why we set goals for ourselves and why perhaps we sometimes ought not to.”

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 10 all but directly on our past four years. Lindbergh’s celebrity as a pilot is rendered as a sort of prototypical version of tele vision stardom. “ Tere’s a lot of hate out there,” says Herman Levin, “and he knows how to tap into it.” “ Tey keep putting it on the radio,” says Bess Levin, “no matter how many times he says it.” Te central ity of the newsreel in establishing mass narrative is played to the max, starting with actual historical footage before slid ing into digital alterations, and climaxing with the well-cast Ryder’s confused yet fattered Evelyn dancing in black-andwhite with Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi ambassador to America. Ironically, the intra-family tensions the Lindbergh presidency brings out in both versions of the story are the same that Roth spent nearly his entire career exorcising from his own psyche: the brim ming confdence, and recursive neurosis, of the midcentury secular Jewish belief that America was homeland enough, all anyone could ask for, in contrast with an older generation’s intractable sense of oth erness, the need to cling to kin against the great assimilating tide of the mainstream. ¤ Ian Brennan and Ryan Murphy’s new Netfix series, Hollywood, comes at the viewer fast with its own vibrant take on the tensions between image and reality. Adopting the swagger of high camp, the series delivers the clean and well-lit in teriors of Musso & Frank’s and Schwab’s Pharmacy, sites of Tinseltown infnite re turn. Tis alternate vision of Hollywood’s Golden Age posits a scenario in which the right circumstances and creative chutzpah sufce to explode the color and gender barriers that prevailed on screen (then and, arguably still, now). “Sometimes I think,” opines a frst-time director to the studio executive on whose good graces his career depends, “folks in this town don’t understand the power they have. Movies don’t just show us how the world is, they show us how the world can be. If we change the way movies are made […] I think you can change the world.” Change the content of the newsreel and the world will follow suit. One moment you’re at the bar con soling yourself over your failure to make it as an actor when a guy named Ernie (who looks a lot like Dylan McDermott) proudly declares, “I have a very big dick”; blink, and you’re a high-class gigolo an swering the needs of high-powered grand dames with erotically disinterested part ners, precocious overworked women in ju nior administrative roles, and, whoa, who’s that — Cole Porter? “I tried sleeping with the help,” declares Patti LuPone as the studio head’s wife, Avis Amberg, a tur baned lady-in-charge. “ Tis is easier. Less complicated.” In response, Jack Castello, earnest and plain with Superman looks, asks from Amberg’s bedroom entryway, “You think I got what it takes to make it in this town?” Or, as seen through the eyes of proprietor-pimp Ernie West, the guy for whom Castello does his energetic business: “In a way, I’m no diferent than Louis B. Mayer!”

Diference, though, is the name of the game, and while the creators have fun with the distinctions between two os tensibly identical, white-bread, would-be male leads (David Corenswet’s Castello and Jake Picking’s Rock Hudson — i.e., the one we know makes it, right?), those two play second fddle to the rest of

NEW FROM MARK K. SHRIVER A Children’s Book with an Inspiring Message HARDCOVER W/ JACKET | 978-0-8294-5269-3 | $14.99 From New York Times best-selling author Mark K. Shriver comes 10 Hidden Heroes, which features a counting and seek-and-find visual extravaganza! Highlighting everyday heroes at home and in our neighborhoods, this vibrantly illustrated book helps children develop counting skills and discover how they too can be heroes in day-to-day life. Ages 3–8 MARK K. SHRIVER is president of Save the Children Action Network in Washington, D.C. He is the author of the New York Times best-selling memoir A Good Man: Rediscovering My Father, Sargent Shriver, which received a 2013 Christopher Award. Shriver lives with his wife, Jeanne, and their three children, Molly, Tommy, and Emma, in Maryland. store.loyolapress.com | 800-621-1008 | PREORDER TODAY MarchAvailable2021

the cast, at least dynamically speaking: LuPone’s regal Amberg; Joe Mantello’s suave, high-minded, torturously clos eted exec Dick Samuels; Jeremy Pope’s omni-talented, radically incoherent, al ways on-the-make Archie Coleman; Jim Parsons’s gleefully vicious proponent of tough love, power agent Henry Willson; Darren Criss’s charmed boy-genius di rector Raymond Ainsley; Laura Harrier’s walks-on-rose-petals starlet of color, Camille Washington; Samara Weaving’s slim beauty set on evading, via stage name Claire Wood, the embarrassment of being the studio head’s daughter; and Holland Taylor’s smoky Mid-Atlantic-accented casting director Ellen Kincaid. Archie wants to get his script pro duced, but fnds himself running lines, and more, with the unknown Hudson; Willson represents Hudson, alternately building him up and dressing him down (literally); Samuels greenlights Ainsley’s picture based on Archie’s script about Peg Entwistle, the real-life actress who jumped from the Hollywoodland sign in agony over her stalled-out career; Claire conspires with Camille over how to fake tears for the camera; Camille puts her sex ual majesty to negotiating use to score an audition from her boyfriend Ainsley for the starring role in his frst picture as di rector, which development sets everyone into a frizzle. All these plot lines converge on the key question: Is it a good idea, in 1947, for a Black woman to play the lead in what must, for the sake of everyone in volved, become a motion picture hit? You commend the ambition. Admire the verve, the refusal of any inkling of shame. Indeed, shame is the enemy over which Hollywood means to triumph, and for more than a minute it looks like the kid might make it. From John Schlesinger’s classic Midnight Cowboy, where homo erotic inklings lurked on the margins of urban squalor, we have arrived at Brennan and Murphy’s Hollywood, where gay desire is central, luxurious, and vehement (“I’m not ashamed,” says Archie, “I know who I am”); where the desires of women of a certain age are insisted on, with immacu lately coifed hair and a sparkle in the eye; where heterosexual unions are slam-bang propositions that crash past with brute force or, alternately, in the show’s one tru ly loving scene between a husband and wife, immediately followed by death. Tere’s a wicked humor to it all, in verting the tropes and expectations of the (straight) hero’s journey: when the pro duction of “Peg,” which turns into “Meg” after Camille lands the leading role, hits a budgeting snag, the guys team up with a plan to turn tricks to fund a sound stage recreation of the Hollywood sign. Addressing blowback from more culturally conservative quarters, and the threat that he will be run out of town, McDermott’s West declares, with a crooked grin and ironclad confdence, “I am this town.” We recognize that he’s speaking beyond the frame for a newly ascendant orthodoxy decked out in the vestments of power, an orthodoxy that is a heterodoxy, a hetero doxy that celebrates every way there is to be, while throwing shade on white-bread normalcy, the tried-and-true universal mold that couldn’t keep all this reveling diference down. ¤ As cheery camp, Hollywood is, at least in part, in on the joke of its own shortcom ings: the original script for “Peg,” around which the entire story turns, is laugh ably awful, with a major bummer of an

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 12

What do we give away when we click “I AGREE” to the terms of service on our phones? Why are billionaires squirrelling away all that money? And why is everyone so depressed? Ms. Never is the story of Farya, who sufers from world-ending depression, and Bryan, who buys and sells human souls for a living. They fall in love, and soon have to risk everything to save their family— and reality itself. “an exceptional work… a fantastical tale…” kirkus reviews (starred review) “a wildly entertaining novel.” indies today (5/5 stars, best books of the year finalist) “extraordinary and unreservedly recommended…” midwest book review AVAILABLE NOW! nupress.northwestern.edu “. . . romps through an art infused life of love, loss, and redemption, inviting the reader on a wild, exhilarating ride.” AVAILABLE NOW! —Carlanupress.northwestern.eduTrujillo,author of Faith and Fat Chances

Tis sentiment is a bedrock of the movie-making ethos, whose fne wording includes at least the possibility, no matter how far-fetched, that it isn’t a lie. Yet the true Fuck You, Hollywood! moment arrives when none other than Eleanor Roosevelt visits the Ace Studios lot to sway the deciders-in-chief into casting Camille as Meg. Te widow of FDR, a woman who was no stranger to power or the potential for politics to efect real-world outcomes, declares to the studio’s gathered digni taries, “I used to believe that good gov ernment could change the world. I don’t know if I believe that anymore. However, what you do […] can change the world.”

Here we have a recognizable depic tion of the ascendant vanguard in the contemporary arts, and it’s in the felt con nection between artifce and lived reality that the phenomenon is most afecting. I am thinking, to take a popular example, of the late Chadwick Boseman respond ing to his experiences getting to know a child with terminal cancer, someone for whom a viewing of Black Panther fgured as the culmination of nearly every wish. Tis was beautiful, and beautiful in part for how it hurt to see the pathos between image-making and reality that tends to determine what we remember best. When such a connection is forced into a fction, however, the takeaway can feel mawkish, at best.Ultimately, it isn’t the series’s glar ing ahistoricity that is damning, the fact that, most especially in the 1930s and ’40s, stars were, in efect, the owned property of the studio heads, who controlled not only which pictures they appeared in, but where they were to dine, at which flm pre miere or party they were to make an ap pearance, and who they were permitted to date, or even marry. Te notion that a frsttime director like Ainsley would have had a leg to stand on in resisting the studio’s decrees defes the reality of that time. Yet this reality is exactly what Brennan and Murphy’s alternate history wants to shake of in its fantasy of a watershed moment when all at once every barrier falls — in cluding the actual history of those who sufered for their diference (like Wong, or Queen Latifah’s Hattie McDaniel, to say nothing of the studio heads themselves, mostly immigrant Jews from ghetto back grounds) on the long hard road toward col lective progress. Tat Hollywood’s creators are savvy to the toxicity that lurks within the prevailing orthodoxy is expressed early in the story when Avis, soon to be the stu dio boss, implores Castello, the actor-gig olo, as he is preparing to bed her, “Make me feel like I matter. Even if it’s a lie.”

ending. Te actress Anna May Wong, an actual early Hollywood player devastated when passed over for the lead in Te Good Earth in favor of a white actress in yel low-face, is performed with beset dignity by Michelle Krusiec, even as Hollywood itself repeats Wong’s injury by sidelin ing her role (though, yes, Krusiec does get an acceptance speech at the end). Te cringe-inducing fnal episode of the series takes place largely at the 1947 Academy Awards ceremony, where the creative team behind “Meg” wins award after award, giving speeches that celebrate what a diference their diference-making has made. “ Tink of what it might mean,” says Herrier’s Camille from the Oscar podi um, “to a dirt-poor little Black girl living in a shanty in some cotton town, where she’s told she’s free but really her life is no better than that of her grandparents who were the owned property of another hu man being […] to see herself up there on that screen. Vaunted. Dignifed. Valued.”

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 14

— BENJAMIN BINSTOCKDISTRIBUTED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS | ZONEBOOKS.ORG

SPRING 2021 Te power these moviemakers wield, no matter how benevolently employed, is that of tyrants, not of politicians elect ed by a democratic vote. To imagine that Eleanor Roosevelt would see societal change as best efected by movies is a dis tortion well beyond the absurd. ¤ Tere is no shortage of things to say about Perry Mason, the Robert Downey Jr.produced reboot for HBO, which plays like a top-notch hard-boiled detective novel. Resolutely the yin to Hollywood’s yang, Ron Fitzgerald and Rolin Jones’s cool, slow-burning yarn vests itself in the se ductive hues — and visceral horror — of Depression-era Los Angeles. From its top-of-the-bill actors Matthew Rhys, Juliet Rylance, and Chris Chalk on down to the bit parts, each memorably scripted and performed, this immaculately wellcast series afrms that even the smallest detail matters in the never-ending tug-ofwar between those with power and those without. Nobody comes through uncom promised — and it’s often knowledge of one’s own transgressions that serves as a driving impulse toward universal justice. Subversive in its own fashion toward the tropes of noir, Perry Mason traces a sort of deranged and unconsummat ed romance between Rhys’s Mason and Tatiana Maslany’s Sister Alice McKeegan, an Aimee-Semple-McPherson-type. It is the ghost of a bond between the dogged, self-destructive investigator and the exu berant, self-evading celebrity minister that turns the gears of a plot involving an in fant’s horrendous murder. Hollywood’s Jack Castello claims brightly to have fought at J.T. PRICE

— GEORGES ABSENTEES:DIDI-HUBERMANONVARIOUSLY MISSING PERSONS by Daniel Heller-Roazen “Weaves scholarly rigor together with theoretical vision . . . Heller-Roazen is operating at the height of his powers.”

— BERNADETTE MEYLER NEW IN PAPERBACK HISTORICAL G R AMMAR OF THE VISUAL ARTS by Aloïs Riegl

“A crucial precedent for the current reevaluation of the theory and practice of art history today.”

BIZARRE-PRIVILEGED ITEMS IN THE UNIVERSE: THE LOGIC OF LIKENESS by Paul North “At once free and rigorous, impertinent and lucid . . . a philosophical tour de force.”

John Outterbridge Untitled, ca. 1974-76. Mixed media. 20 x 18 x 17 in. (50.8 x 45.7 x 43.2 cm). Collection of Vaughn C. Payne Jr., M.D. Photo by Ed Glendinning. Photo courtesy Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

What you wanna do is take these poor sufering people’s hope away? […] You need to decide what kind of person you wanna be.” Te tension between a private awareness of ugly facts and the public vo calization of a popular narrative gives the ostensibly apolitical Perry Mason its quiet political torque. ¤ No actor living does a look of deathly judg ment as well as Charles Dance, and it is his withering gaze, as William Randolph Hearst, around which the drama in Fincher’s Mank turns. Mank is a great flm, not because it is perfect but because it’s overabundant, deft in its commentary on the relationship between Hollywood and politics, and the kind of picture that doesn’t really get made anymore. What begins as a standard postcard to Hollywood’s Golden Age soon re solves into a split narrative: a Beckett-like present-tense wherein a bedridden Herman Mankiewicz (played by Gary Oldman) scratches out his masterpiece on deadline for Orson Welles (Tom Burke, brilliantly channeling the voice) — a drama, Citizen Kane, about a man whose immense wealth and fame can’t satisfy him; and a remembered history of Mank’s rise and fall in the court of Hearst at San Simeon, which features Amanda Seyfried’s smarter-than-she-looks Marion Davies, Ferdinand Kingsley’s resolutely poised Irving Talberg, and Arliss Howard’s bombastic, mercurial Louis B. Mayer. Te story grows more interesting by far when the focus segues from movie making to political campaigning, a shift in the script that culminates with the best send-up of a Republican Party cel ebration on screen since Hal Ashby’s Shampoo. Rather than sharp-edged satire issued from some imagined moral high ground, Mank ofers a rueful observation of the state of play from a guy close to the nerve center of conservative politics, his deep misgivings fnding expression only in his art. A dissolute screenwriting suc cess whose satirical tongue can’t hide the fact that he’s a softie, Oldman’s Mank is one part Bryan Cranston in Trumbo, one part John Hurt in Krapp’s Last Tape, yet a sweeter and more freewheeling spirit than either of them, a fellow on whose shoul der Seyfried’s Marion Davies can rest her golden head for a minute, and to whom that loaded exchange will recur and recur and recur in memory. Blackout drunk, he awakens in yet another magisterial bed (the set designers who selected the beds for Mank deserve special recognition; these are beds of enormous character).

Te functionary assigned by Welles to keep Mank on schedule encourages the screenwriter to write down to his audi ence; his refusal to do so stands as her oism, or at least its facsimile. Any minor liberties with the facts here seem like fair play for a fctive work. J.T. PRICE

17

Anzio, while looking as if he never saw a day of battle; Rhys’s Mason mentions the trenches of the Argonne, and one glance at his face appears testament enough. When Mason seeks to cash in on com promising pics of a Fatty Arbuckle type making merry with an up-and-coming starlet (and various foodstufs), the head of the fctional Hammersmith Pictures drops his mask of jollity to oversee hired thugs in torturing Mason. “People are desperate out there, Mason,” says the mo gul (played by Howard Korder), “and for one little nickel, what do we give them? Two hours in the dark. Singing. Dancing. Laughter, tears, romance. Hope. […]

Ultimately, it is the art of art, and not the bullhorn, that sways hearts and minds. Te likeness to life we behold in fction happens to be pure illusion besides. It is our own lives, at least for the present, that matter.

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 18 “ Tis is a business,” says studio head Mayer, speaking not just to his screen writer Mank in the mid-’30s but, why not, to the coterie of hopefuls in Hollywood convinced of moviemaking’s moral vir tue, “where the buyer gets nothing for his money but a memory. What he bought still belongs to the man who sold it. Tat’s the real magic of the movies and don’t let anybody tell you diferent.” What Mank experiences leaves him only with the foundering wish to look after those who pass within his orbit. When he fails at that, an excoriating wind rises from his throat, alienating everyone at Hearst’s al titude — and driving the speaker into an exile from which, years later, he will draft his masterpiece.Discussingthe Upton Sinclair cam paign among Hearst’s court at San Simeon, Mank teases, “Upton just wants you to apportion some of your Christmas bonus, Irving, to the people who clean your house.” As everyone laughs, Talberg responds, “Nobody’s asking to hear you sing the WhenInternationale.”Talberglater prevails on him to contribute to Mayer’s fundraising campaign on behalf of the Republican gubernatorial candidate, Mank refuses, in of-handed fashion, “You have every thing it takes right here. You can make the world swear King Kong is 10 stories tall and Mary Pickford a virgin at 40. And yet you can’t convince starving vot ers that a turncoat socialist is a menace to everything Californians hold dear?”

Taking the barb perhaps more literally than the screenwriter intended, Talberg commissions a set of faux-documenta ry flms featuring actors who pretend to be everyday American voters, a form of propaganda that sways public opinion not so much by the merits of argument as by how strongly the public identifes with the person speaking on screen. After this technique proved highly efective for the Republican Party in 1934, the step from defeating Sinclair to seeing Ronald Reagan into the governor’s mansion three decades later really wasn’t so great at all.

In between, from the Depressed ’30s to the Swinging ’60s, a period of wide spread homeownership and prosperity took root. Notwithstanding the many ex cluded from the American dream of the 1950s, the average CEO of that era made 20 times the salary of the average worker while, in our day, that ratio stands at 271 to 1. Rising roughly in parallel to CEO salaries were the earnings of movie stars as the original studio system crumbled into dust.Te politics of Mank are ambivalent, as perhaps are those of the greatest art.

Te screenwriter’s stance isn’t about po litical ends — we have no reason to be lieve he actually wants to see a candidate like Sinclair elected — but the means. His objection is to a breach of fair play, which turns out to be a deft message for our age of ever-more-fervent absolutes.

John Outterbridge, No Time for Jivin', from the Containment Series, 1969. Mixed media. 56 x 60 in. (142.2 x 152.4 cm). Mills College Art Museum Collection, Purchased with funds from the Susan L. Mills Fund. Photo by Ed Glendinning. Photo courtesy Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

20

TARKOVSKY

MICHAEL M. WEINSTEIN [indistinct chatter] say the subtitles, and my eyes listen harder tug the loose thread of sadness through the syllables the familiar fray where the voice’s poise and fuency start to unravel — free.hethetoonscreenformeroflikevulnerabilityswallowedastoneinthethroatthebroken-facedbusdriver—becausehisdreamhoisthispastandleaveonlycityhasknownwillnotsethimIcanfeelthe

21 last thread snap, then drop.

Ten a silence: the kind of day when the sun seems to carve light into every edge, a medieval engraver with gold leaf stuck to fngers that have traced each frontispiece since the birth of the world. A hard almost reverential light as if the day watched what becomes of us. In this movie, it does: it lavishes the man with attention nothing else pays — his misgivings, mistakes. It is based on real life.

Nancy Lupo, Container, 2016, Rubbermaid Brute ICE ONLY 10-gallon container, 30 Nasco Human Body Fat Replicas, 1 lb., 18 x 17 x 16 inches. Courtesy the artist and Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles.

23 ESSAY

KATHERINE

SEX —

EVERYTHING

In Netfix’s Sex Education, teenager Otis struggles with his mother Jean’s profession: she is a sex therapist. Tey live, the two of them, in a home adorned with vulval art. Patients — individuals, couples, groups — come to unpack their sexual difculties and participate in plea sure workshops with Jean. It’s mortifying for Otis, whom Jean is constantly trying to get to talk about his feelings. And yet somehow Otis, despite his uncomfortable situation, fnds himself advising students at his school on their sexual problems. He has problems too: he can’t masturbate, and is repulsed by the thought of ejaculating. Jean, for her part, has difculty commit ting to a man. Having separated from a philandering husband — with whom she co-wrote sex books — she now has fings AND ELSE ANGEL

.

Te Fall in fact had a dark subcurrent running beneath its supposed celebra tion of female sexual agency. Its slavish depiction of the ways a killer pursues his female victims felt designed to instill ter ror in women (it certainly did in me). Te show felt curiously pedagogical, even in structional; a scene in which Dornan ac quired an unsuspecting woman’s address made me resolve, briefy, never to talk to a pleasant-looking man on a train again. Te Fall seemed almost to salivate over the killer’s murderous schemes. Under the guise of feminism — and with a fgure of Anderson’s stature standing in for female empowerment — the series got away with a lot of traditional, titillating misogyny, feeding an appetite for crimes committed against the bodies and hopes of wom en and girls. It addressed women by as suming, and insisting, that they must, as scholar Rachel Hall has put it, be “afraid of becoming the next body in line.” Tis kind of address to a viewer can be read as feminist — after all, the series is savvy about the violence and injustice women face. And what enabled Te Fall to feel feminist was precisely its depiction of an assertive woman pursuing sex for its own sake, a woman who unashamedly satisfes her sexual desires. A high sex drive in women may be read as assertively feminist, but it also worries us. In Te Fall, Stella’s sexual con fdence and pleasure set her up for a fall: they make her more vulnerable, or more hateable, or more punishable. Te eternal warning is there: that the pursuit of sexual pleasure may bring women more danger than it’s worth. In many narratives, a high sex drive can fgure as a red fag for some deeper pathology. In Sex Education, Jean meets Jakob, a rugged Swedish handy man, and they begin to have sex; gradu ally, a relationship develops, but Jean is rufed and unsettled — Jakob leaves his things in her house; he noisily cooks or does odd jobs while Jean sees patients; he disrupts the calm space of her home. Her frustration grows, and she lashes out at him. Ten her oleaginous ex-husband turns up, having been thrown out by his current partner, and she kisses him. Jakob fnds out, is heartbroken, and leaves her. Regretful, she comes to realize that she misses Jakob and wants him back. But the betrayal is too much for him, and she has lost her chance at happiness. While Jean may be read as feminist in large part be cause of her “masculine” approach to sex

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 24 and one-night stands, attending to them with a brisk efciency. Matter of fact with her partners about these arrangements, she is also straight with Otis, and he takes to pointing out to heartsick men coming down for cofee in the morning that his mother “doesn’t do relationships.”

Jean does, however, have a high sex drive, which often functions in popu lar discourse as a symbol of female em powerment. Contemporary feminist dis course often fgures the truly emancipated woman as one who is sexually confdent and assertive, as brazen as a man. Gillian Anderson’s Jean in Sex Education is not dissimilar to Stella Gibson, the detec tive she played in Te Fall, an ITV show that also starred Jamie Dornan (of Fifty Shades) as the serial killer Gibson is trying to track down. Stella is a ballsy feminist: she speaks back to presumptuous male colleagues, and she is sexually assertive. She pursues men for casual sex and, like Jean, treats these encounters with a breezy masculine air. Stella was readable — and rhapsodized over — as an admirable, crush-worthy feminist, just as Anderson’s Jean is in Sex Education

25 — instrumental, pragmatic, unsentimen tal — this approach is also represented as a cover for her deep longing for intimacy and love. She fell in love, felt vulnerable, and sabotaged the relationship. Her sex ual appetite was thus both a sign of her unhappiness — her impulse to keep inti macy at a distance — and a further cause of it.Watching Anderson in Sex Education, I thought, too, of Samantha Jones, the sexual libertine of Sex and the City, which aired on HBO in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Tat show featured material that was in some ways radical for mainstream TV at the time: women talking irrever ently about sex, their partners’ penis sizes, STDs, fertility. Te four main characters were to a large extent stock types: Carrie was overwrought and creative, Charlotte prim and prudish, Miranda smart and cynical, while Samantha was the voracious and adventurous one, racing from one sexual encounter to the next. Like Jean in Sex Education, Samantha didn’t really, or comfortably, do relationships; like Jean, she stood in for the emancipated woman, fnally free to be as sexually carefree as a man. Samantha’s character invited the audience to admire — and to enjoy be ing shocked and thrilled by — her brazen attitude toward conquest, her frankness about her needs. It’s not, of course, that simple. Te sexual freedom and assertiveness of Jean Milburn and Samantha Jones are also si multaneously portrayed as rather patho logical; it’s hard to let time-worn stigmas go. Sex and the City’s defant celebration of fnancially independent women pursu ing sexual pleasure fought for space with the show’s own prescriptive undertones. It could be daring, insightful, and tender; it was smart and acute on the sexual double standard (remember the guy who criti cized Samantha for inadequate genital grooming?), but it also tended to follow a neat, lesson-learning structure, emerging no doubt from the weekly advice column on which it was based. Te four diferent types of girl would, in their weekly sce narios, learn an often-painful truth. In Samantha’s case, these lessons were usu ally cautionary: don’t expect commitment from a fuck-buddy; if you pursue men purely for sex, you are going to have no one to mend a broken curtain rod when you need it, or make you soup when you’re ill. Tese depictions were undeniably driv en by some familiar misogynistic horror of unrestrained female sexuality. We may valorize women’s sexual desire, but that doesn’t mean we don’t also have the same old anxieties about it: the admonitory im age of the out-of-control maneater who ends up Samantha,alone. for all her pleasure-taking, her joyful escapades, was, we were meant to know, really searching for an intimacy she both craved and feared. When she loses her capacity to orgasm and, preoccu pied by frantic, thwarted masturbation, is unable to express sympathy or tenderness on hearing of Miranda’s mother’s death, it is fairly clear that her sexual frenzy is a desperate keeping at bay of something else entirely (she eventually breaks down at the funeral). A promiscuous woman has to be in denial about something, right? Samantha sufers for her sexual liberation; she is lonely, she gets hurt. Ultimately, she represents not a joyous libidinal emanci pation but a conservative anxiety about the very idea of sexual liberation for wom en, a sense that women are just not made for sexual freedom. Her promiscuity is depression denied, her sexual emancipa tion a delusion. Te audience is asked to KATHERINE ANGEL

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 26 enjoy, vicariously, her unashamed sexual indulgences but is also warned that she is a pitiable fgure — because her sexuality is ultimately empty, her voraciousness a facade behind which cowers a damaged woman fearful of love and commitment.

Te recent BBC series Fleabag took this dynamic still further, ultimately prob ing it more thoughtfully. Fleabag firts with earnestness, in a winkingly knowing way, only to puncture it; the show evinc es a palpable distaste for the po-faced, an urge to defate pomposity. But pretty soon, the more painful motivations be hind the winking humor become clear. In the opening scene, the eponymous her oine pretends to have just arrived home at 2:00 a.m., so as to appear nonchalant when a booty-call appears at her door. She tells the viewers that she’s just gone through the rigmarole of digging out her sexy underwear and “shaving everything” so that she can appear efortlessly appeal ing. Te sex, she says, is okay: we see them have anal intercourse, for which the man is grovelingly grateful, but it’s not clear whether the act is pleasurable or joyful for her. Fleabag is frankly cynical about sex: she enjoys using it, enjoys watching various men want her, need her, be grate ful for her. Her sort-of boyfriend Harry, a rather wet, doleful character, tells her on the event of their umpteenth breakup that there’s no point her “turning up out side the house in your underwear, it won’t work,” at which Fleabag ficks her gaze to the camera and whispers, knowingly, “It will.”She’s arch, she’s canny, but does Fleabag enjoy the sex she has? While she’s having sex with a guy with protrud ing teeth, he keeps repeating, “ Tat was amazing,” but she just says, with a fake smile, “Yeah.” With another man who asks her if she’s okay, she replies, overly brightly, “Yeah, I’m amazing.” Te insin cerity is glaring. Fleabag is compulsive about sex but does not seem to be en joying it very much. “I masturbate a lot these days,” she says, “especially when I’m bored, or angry, or upset, or happy.”

Talking to a therapist, whom her father has paid for, she says — again brightly, a performative smile on her face, defend ing herself against sadness — that she’s “been for most of my adult life using sex to defect from the screaming void inside my empty heart.” It’s self-knowledge as camp — but it’s still painful. Te sex in Fleabag, though often rather joyless, does have its pleasures, not least the knowing ness of the performance, as the heroine dissects sex’s petty humiliations, pokes fun at masculinity’s fxations, all while speaking directly to the audience. But the savvy humor is often a kind of bargain, a way of gaining something while stav ing something else of. At the end of the frst episode, we learn about the death of Fleabag’s mother, and about her friend’s apparent suicide, yet Fleabag seems to be trying not to grieve. In Sex and the City and Sex Education, a woman’s high sex drive serves as a marker of feminist fulfl ment — you go, girl! — while also fgur ing as a cover for a deep longing for all the traditional trappings of marriage: stability, emotional commitment. Yet this longing is disavowed and converted into anxious avoidance. While Fleabag might nod to the pressure women feel to be performa tively sexual, it also exposes the way sex can be used to manage unbearable grief, to keep excruciating loneliness at bay. When Fleabag takes her dead friend’s hamster out of its cage, and reluctantly begins to stroke it after a long period of neglect, she is acknowledging that mere sex does

KATHERINE ANGEL

27 not amount to intimacy — that she is a lonely woman, in need of warm human contact.When I frst started watching Fleabag, it felt wearily familiar: as with Samantha in Sex and the City, it seemed to be asking whether a woman behaving like a man (or, rather, adhering to what is typically cast as masculinity) is a recipe for happiness in sex. Sex and the City was ultimately inca pable of imagining a sexually adventurous woman as anything other than a failed mimicry of manhood, parroting clichés of what she thinks men are like — only out for themselves, unable to truly feel, prioritizing their orgasm over everything else, dispensing with tenderness or obliga tion. Te way Samantha, and Jean in Sex Education, assert their right to sex uncan nily mirrors the way men are thought to assert theirs: these women fuck like men; they avoid intimacy and vulnerability, treat lovers as dispensable — and it makes them miserable. Fleabag is in some ways continuous with these portrayals. Te sex Fleabag has is gallingly empty; she is so detached from it that she can talk to the camera while having it. Tese asides to the audience are an oblique way of critiquing and ruefully regretting the performative aspect of sex that so many women experience at one time or another — the hyper-awareness, the experience of seeing oneself from the third person, from the outside. Tis sort of critique often edges into a view that women’s sexual feelings are themselves in authentic, only ever brought in from the outside.But this is not all that Fleabag is doing. Te second season ofers a much deeper delve into the unbearable pain and shared grief in families that can manifest either in sudden aggression or in a wary keeping of one another at arm’s length. In the ear ly episodes, Fleabag rather hyperactively defends herself against her own misery, trying to convince us that she is okay. In the later ones, her attempts to do so lose their potency, as both she and the series itself come to embrace a deeper reckoning with her grief. It’s a relief — though a poi gnant one — when Fleabag fnally has sex that appears so genuinely joyous that she pushes the viewers and the camera away. And yet something in me prickles at my own account of the show. Why? Because it has been so hard for women’s sexual desire to fgure at all, except as a symptom, or a metaphor for something else. In popular culture, women rarely simply have sexual desire; instead, it is usually in the service of, or a cover for, something they want more (such as inti macy). Is it possible ever to see a woman’s sexual desire as simply itself, rather than as a vehicle that usually winds up afrming traditional virtues? Tis might be a wor thy political aim for popular narrative: for sexual desire to simply be, without having to be explained, justifed, or rationalized. (Te Good Wife and Broad City did a good job along these lines.)

Because women’s sexual activity has so often been pathologized, it is import ant to be on guard when watching depic tions of sexually voracious women. Tey often serve as warnings, or as rueful de pictions of how unnatural a libidinous woman is, how her desire cannot really be what it seems but must instead be a com munication of something else. Fleabag shows us, however, with unusual intensity, how everything else in life does pervade our experience of sex, and our desire for it. Sexual desire can both be sexual desire and something else, can express diferent, even competing aims and impulses. In addition

Nancy Lupo, Open Mouth, 2019 (detail), cast aluminum bench, bronze, iron, nail lacquer, 22 7/17 x 54 15/16 x 29 9/16 inches. Courtesy the artist and Kristina Kite Gallery, Los Angeles.

29 to being itself, sex can also be, and often is, a way to manage pain and sufering, to contain and suppress certain feelings (sor row, fear) while engendering others (relief, absorption, distraction). Sex can distract us, can help us feel something when we are numb, can help us release feelings we didn’t know needed releasing. Like any other human activity, sex can be recruited to the management of pain. In his book on Freud, Jonathan Lear writes that the founder of psychoanaly sis “regularly causes ofence because he is seen as trying to reduce our mental life to our animal nature. But in our sexuali ty, as Freud understands it, we are unlike the rest of animal nature.” For Freud, Lear argues, the human sexual drive is impor tantly diferent from animal instinct, in that it is so varied in the activities it in cludes and the targets of that activity; we can recognize as sexual an activity that is unmoored from reproduction, such as fe tishism; sexuality can manifest itself in the least overtly genital activities. Nothing, in other words, is excluded from potentially beingWhat’ssexual.more, while one of the clichés about Freud is that he reduced everything to sex, it’s more accurate to say that sex be comes, in psychoanalysis, a way of think ing about everything else. Tere is such ambivalence and melancholy in Fleabag’s portrayal of female desire. Rightly so, perhaps — and not just because sex is a source of deep pain and confusion for many, but because it acknowledges that sex is also about the rest of life. Sex can be a window onto meaning. Te trick is to think about what sex can do without reducing sexual desire, especially in wom en, to something that is only ever brought in from the outside. But Fleabag’s hunch — one that bears further exploration — is that the way we have sex can tell us a great deal about what we want, what we fear, and what we grieve. KATHERINE ANGEL

31

W hen, in 2016, photographer Janna Ireland frst started a project of shoot ing buildings around Los Angeles designed by Paul R. Williams, she had almost no idea of what his work was like. I have to confess that, for a long time, I shared her ignorance. Like many Angelenos more than a little familiar with local history, I’ve always been more aware of Williams’s stature as an iconic local architect than of his actual work. I thought of him as a fgure more historical than aes thetic, one of many trailblazing black profes sionals who de fned ascending black L.A. and the Central Avenue scene at its zenith in the 1940s. I assumed that his designs followed the popular ones of the era — streamline moderne, Art Deco. Tat would have been impressive enough.

PAUL R. WILLIAMS IN LOS ANGELES: A CONVERSATION WITH JANNA IRELAND ERIN AUBRY KAPLAN

INTERVIEW

But, over the years, I’ve learned that the scope of Williams’s work was much more varied, stylistically and functional ly, than I ever imagined. Geographically, it ranged across the city, and across the cities of Southern California, and beyond. Ireland’s new book, Regarding Paul R. Williams: A Photographer’s View (Angel City Press, 2020), captures that scope not by cataloging the physical buildings — Williams designed an astounding 3,000-plus, including luxe single-family homes for Hollywood stars, housing projects, hotels, and churches — but by capturing the emotional sweep and dogged ambition that connects all of Williams’s work and creates a narrative about Los Angeles itself.

Ireland’s black-and-white images are sometimes intimate, glimpses of voluptuous staircases and immaculate interior walls in half shadow; sometimes they observe, unsen timentally but meditatively, dirt and concrete lots where Williams’s work used to be. Tere is a poignancy to all of this that make each image a compelling piece of a larger search for the essential meaning of Paul R. Williams, and of the city that gave him his chance. It’s a search that, for Ireland, is far from over. I recently talked to Ireland about the book and its impact. ¤

ERIN KAPLAN: Te photos in this book are beautiful and profound, but also kind of feeting and elegiac. Tere are stately structures that have stood the test of time, and there are the ghosts of what were. Overall, your images capture built Los Angeles at its core. Did you plan JANNAthat?IRELAND: Originally the idea was to photograph buildings that were still in pretty good condition. More and more I’d hear about a Williams building that was in a fre or damaged, and I want ed to get to places in various states of re pair. In terms of fnding places, I did my own research, one person would lead to another, and another. You didn’t know much about Paul Williams before you started the photo project. What do you think of him now? He was someone who was really brilliant, creative, and driven in a way that is in teresting. He had to maintain this career, keep his ofce open for 50 years. Tat took lots of tenacity.

He’s a continued source of fascination for me, the way he presented himself, the way he wanted to keep things positive, to minimize the stress of racism. He himself said about his own life, “It leaves you to consider the facts.” Te epiphany he had of not competing with the white world but of always competing with himself, of blocking everything else out — I love that.

It took incredible skill to please all these clients and to fulfll all these diverse interests. If he had wanted to or if he had been in a position to, he absolutely could have developed a “signature” style the way many architects did — the way he uses curves jumped out at me. His own house is full of curves, it’s defnitely something I see again and again in his work. But that diversity was kind of used against him, it made him a generalist and not specialized or exclusive. But his diversity was his ge nius. It’s what made him unique, and also ubiquitous.Hisvariety is very L.A. You can have one block with houses in many diferent styles. Back east, you have row homes, and there’s a real uniformity, but here there’s a feeling that anything could be on any

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 32

Hillside Memorial Park Mausoleum (in Culver City) was my favorite building. It was very peaceful, very resonant. For all the “gone” structures — the rubble — there’s the question of what comes next? So often in architecture, these really classical houses are replaced with monstrosities. I’m always thinking about that, so I was trying to get the last little bit of what remains. One thing I learned doing this project is that people buy Paul Williams houses, they promise sellers to preserve them, then they get torn down. It’s kind of horrifying. What else did you learn? Before starting this, I knew only a little about black history here. I knew about the First AME church that Paul Williams designed, and attended. I learned about racial redlining, restrictive covenants. I didn’t know specifcally about segregation in L.A., but it didn’t surprise me at all. But I fell in love with L.A. — it has a real art community. Tat’s a necessity for me. My grandmother lived here when I was grow ing up, so I had that connection. Now I live in Sherman Oaks. Paul Williams did a couple of smaller projects here in the Valley, in Encino.

33 street. Paul Williams started his career in the ’20s when there was still much to build in Los Angeles; his work was from the ground up. He did many single-family homes across the spectrum of styles, from Moorish to Spanish Colonial to Tudor. You capture a lot of that spectrum in this book. But you say it’s the tip of the iceberg. Tere’s so much more to do! I didn’t shoot the buildings he worked on with part ners, partly because it’s hard to see the line between his work and someone else’s. I didn’t shoot the Beverly Hills Hotel, where he designed an addition — not the whole building, though the hotel’s iconic lettering is his. Paul Williams is so iconic, but he’s not well known. I would say he’s not unrecognized, but underrecognized. I think because of the sheer variety of his work, and because of his race, he never got recognition during his lifetime (he won the prestigious AIA Gold Medal Award in 2017, 37 years after his death in 1980). I’m still going, trying to get into the ar chives at Getty and USC.

ERIN AUBRY KAPLAN

You write in the book’s introduction that you’re not an architectural photographer or a documentary photographer. How would you characterize this book? Tis book isn’t the frst of its kind, but it’s the frst of a kind. I haven’t fgured out exactly what to call it — fne art photogra phy, but something else. It isn’t a straight forward architectural book. It might be confounding for some people who are ex pecting that. Tere is overlap of photog raphy and architecture, of course. But this is its own thing. Te choice of shooting in black and white seemed right, though not because the buildings are old and I want ed to do this period thing; it just felt right for the project. I moved to Los Angeles six years ago, got a driver’s license when I was 31. For this project, I drove around a lot, mostly on Saturdays. My favorite thing was visiting communities where Williams designed all the houses, created a scene — like in Rancho Palos Verdes, and Willowbrook. I liked seeing him all around me, as opposed to seeing one of his houses here and there.

35

How did you integrate this project with your working life, and your life as a wife and mother? Before the project, I was working fulltime as an administrator at USC, teaching at Pasadena City College, running around and commuting. After I had my second child, I eventually quit USC because the cost of childcare basically meant I wasn’t making money, just breaking even. After I started the project at the end of 2016, I did an exhibition, then kept going with it in 2018 and 2019. Te whole thing fed on itself.Tehomeowners whose places I want ed to shoot received me very well, though for others it didn’t quite happen. But once someone knew what I was doing, they were usually very happy to help. All of them had at least one of Karen Hudson’s books (Hudson is Paul Williams’s grand daughter, an author and director of his archives). For the most part, people who lived in these houses understood they had something very special. Te day I went to Rancho Palos Verdes to shoot, I did feel very selfconscious. Very conspicuous. Carver Manor in Willowbrook, next to Watts, was very diferent. Te single-family homes in Willowbrook were conceived by a black woman, Velma Grant, who fgured middle-class black people needed some where to live after World War II. Williams started designing public housing proj ects, Pueblo del Rio, Nickerson Gardens. He also designed stuf way outside Los Angeles — in Memphis, Oregon, South America. I’d like to fgure out where more of these places were. What do you want people to take away from this book? I hope it encourages them to go do their own research. Tere’s room for lots of dif ferent projects about Paul Williams’s work. It deserves more. For me, doing the book defnitely made my world in L.A. bigger — it introduced me to all these architects and all these other people interested in the city. I discovered the art community, but there are so many other people that I never would have encountered otherwise.

ERIN AUBRY KAPLAN

Te East Coast perception that there is no culture, no history, here — that’s not true. Te city has now become a subject for me. It’s L.A. as subject, not just, “Oh I’m here and I happen to be taking pictures.”

40 Te bank is empty. A cluster of birds live there. Te birds are all gold, but they can fy like dollars. Tey are lawless birds glorifed by all our poems. If you look closely at the ones in the corner, some of them have human lips. A DEBT VICTORIA CHANG

41 Mass graves are modern. I caught up with the future, the metal trees are silent as they wait for us. Te future isn’t modern. It worries it won’t arrive. WHAT IS MODERN VICTORIA CHANG

Celia Herrera Rodríguez, La Jornada, silkscreen print on Japanese paper, 2011. Created for exhibition Ser Todo Es Ser Parte/To Be Whole Is To Be Part at LACE. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Ray Barrera.

43 FICTION

Washing her hands in the dark, empty bathroom of a rest stop of Highway 10, just west of Ripley, California, Margaret’s thoughts turned once more to Lloyd and Ray Pettibone. Of all the old enemies she was think ing about revisiting upon her return to Los Angeles, the Pettibone brothers were the ones who made her skin crawl the most, Lloyd in particular. Te little bastard had laughed in her face. Murdered a 20-yearold girl and made a paraplegic out of her 17-year-old brother, and when she’d promised him she was going to fnd a way, somehow, someday, to make he and Ray pay for both crimes — having failed mis erably to build a prosecutable case against them — he’d chuckled at the threat as if it had come from a little girl in pigtails: “I guess I’ll see you tomorrow, then.” Maybe if Churchill Stevens hadn’t been everything Lloyd Pettibone wasn’t — a young, hardy black man with a mind HAYWOOD

QUEEN'S RUN GAR ANTHONY

Outside in the parking lot, standing alongside an old Chevy sedan with a white man who, in look and demeanor, delivered the same message of lingering desperation. Teir car had been so loaded down with dufels and garbage bags, it sat as low to the ground as a tortoise. At 2:00 a.m., the couple and Margaret had been the only ones stirring in the entire rest stop. Rather than enter a stall to do her business, the woman went straight to a sink instead, on the end near the door to Margaret’s left. She didn’t speak, just turned the water on and made a halfhearted attempt to run her hands through

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 44 and a future and zero interest in the thug life — Margaret might not have taken what the Pettibones did to him so person ally. But Churchill was a jewel, a rare ray of light in a desolate, South Central patch of the City of Angels that generally knew only darkness, and to see him reduced to an emaciated, paralyzed stick-fgure by two pieces of shit like Lloyd and Ray Pettibone … It had just been more than Margaret could bear. Lloyd Pettibone hadn’t been the frst punk to treat her like a joke and he hadn’t been the last, but it was he and his broth er Ray she now found herself wanting to pay back more than all the others. Not because of Lloyd’s cruelty or disrespect, but because of his apathy. What he and his brother had done to Churchill Stevens and his sister Violet hadn’t moved Lloyd Pettibone one way or the other; it had just been something that needed doing, like hammering a nail or taking out the trash. He should have been made to feel something, some combination of pain and regret, but Margaret had left that job undone.Tis was part of the unfnished busi ness she would spend the next few days attending to in Los Angeles. She remembered Lloyd Pettibone’s crooked, self-satisfed grin and felt the old familiar outrage boil to the surface. She’d been suppressing it for years, unwilling to agonize over something she could never change — but now she let it come, turn ing a deaf ear to the dull voice in her head demanding that she come to her senses and drive her sick, crazy ass back home. It wasn’t too late. She hadn’t yet done anything to embarrass herself and no one ever had to know she’d come this far. All she had to do was get back in the car and return to Scottsdale. Crawl into bed, say a prayer, and commit herself to being a compliant, hopeful cancer patient. It was a tempting thought. But not tempting enough. She wasn’t going home. She was go ing to Los Angeles. Not just to enact some revenge against Lloyd and Ray Pettibone, but against this thing, this crawling evil, that had taken root in her body and was threatening to destroy it, one cell at a time. What she couldn’t do to cancer she would do to the Pettibones because it was either that or lose her mind. She had run into a mammoth trafc jam just outside of Goodyear that had set her back almost four hours and she was exhausted beyond description. She was at the bathroom sink in the ladies’ room, freshening up to stay awake, when the girl came in. A big white girl with oversized teeth and jet-black hair, cut the way a blind man might have done it. She wore a silk-screened T-shirt one size too small underneath a dark green hoodie, and den im pants with shredded holes along the tops of both thighs. Margaret put her age at somewhere in the early 30s, her silver nose ring Margaretnotwithstanding.hadseenherbefore.

“Go fuck yourself,” the man said, but he was in too much pain to put any sub stance behind it. Margaret rushed out, paused to fre a round into each tire on the driver’s side

“ Te man outside waiting. Te one who sent you in here, with the beard and the gut. Call him!”

Another second passed before she was convinced: the Beretta wasn’t blufng, even if Margaret was. “Danny!” He came storming into the room in short order, reckless and clumsy like an ox in heat. He was a big blonde, with thick arms and legs and a neck that wasn’t there, but the most he could do with all of it was throw it Margaretaround.put a bullet in his left shin, just below the knee, to take the steam out of him right away. He howled and went down in a heap as his woman let out a scream of her own. Margaret backed her way to the door, stopping just long enough to pick the girl’s knife up from the foor.

GAR ANTHONY HAYWOOD

45 the spray. Margaret dried her own hands on a towel and watched her, waiting, but the girl wouldn’t look up. Shit, Margaret thought. She started for the exit and the white woman stepped away from the sink to block her path, shaking the water from her hands.“Hey,excuse me. Don’t mean to both er you, lady, but I wonder if you could help me out.”Upclose, her frayed nerves and ill in tent were more easily recognized. She was in a bad Margaretway. tried to move past her but the white woman blocked her again, slip ping a knife from the pocket of her hoodie as she did so. It wasn’t much of a knife, but she held the blade up high where Margaret would be forced to consider its potential for mayhem. “I don’t want to hurt you, nigger, but I will. Your money. Everything you’ve got, rightMargaretnow.” had felt sorry for her to this point but being called a nigger with a hard “R” had its usual efect, sucking her dry of all sympathy. She performed the required assessment, relying on old skills not yet dead, and decided the woman before her was nothing she couldn’t handle. “Okay. Please don’t hurt me.” She nodded and raised her left hand in com pliance, then reached into the purse hang ing from her shoulder with the right. “Easy!” the girl said. Easily or otherwise, Margaret had the Beretta out of her purse and pointed at the girl’s face before she could blink. Te knife seemed to fall from her hand with a will of its own. “Call him,” Margaret said. Te white girl didn’t seem to under stand. Her eyes were wide with terror and she lilted to one side, unsteady on her feet. “Lady, I don’t — ” Margaret almost laughed. She’d stopped being a “nigger” and was back to being a “lady” again.

“You fucking bitch!” the woman said. “Yeah, that’s me. On the foor. Face down. Unless you want some of what boy friendTgot.”ewhite girl didn’t move. “What, you think that shit was an accident? Grandma with a gun just got lucky?” Margaret took aim at her right leg. “All right, all right! Fuck!” She got down on the foor, her man still wailing and bleeding beside her. “I’m leaving now,” Margaret said. “I see either one of you outside before the count of a hundred, I fnish you.”

Celia Herrera Rodríguez, La Cuentista, silkscreen print on Japanese paper, 2011. Created for exhibition Ser Todo Es Ser Parte/To Be Whole Is To Be Part at LACE. Courtesy of the artist. Photo by Ray Barrera.

47 of the overloaded Chevy, and resumed her trip to Los Angeles. ¤ Minutes later, fying down the interstate, eyes checking her mirrors for the fashing lights of a Highway Patrol car that had yet to appear, Margaret was overcome by a giddy lightheadedness she hadn’t known since her earliest days as a rookie cop. She still had it. She was still the Queen. She should have been ashamed for taking such a stupid chance, shooting a man in a public rest stop and leaving the scene of the crime, but she wasn’t. She felt good. Alive. Te asshole and his lady friend had fucked with the wrong angry black woman. She rolled her window down and laughed into the wind. When her cell phone rang, she almost didn’t hear it. She took it in hand and checked the display: Early again. Her sec ond call in three hours. Margaret hadn’t answered the phone the frst time and she was reluctant to answer it now. Te voice mail Early had left previously mentioned no emergency; she just wanted to talk. After 11 months of treating Margaret like a pariah. Te child’s timing was incredi ble. Even if Margaret were interested in a reconciliation — and to her mild surprise, she was — it was too late to pursue it. Any peace she made with her daughter now would only feel like a slap in the face to Early later, after Margaret had done what she was planning to do behind Early’s back in Los Angeles. And yet … It was almost 3:00 a.m. Two unanswered late-night calls would almost certainly arouse Early’s suspicions. As broken as their relationship was, they’d never been in the habit of not picking up the phone for each other. If Margaret didn’t answer this call, a third would come after it. And a fourth after that. Margaret put an end to the phone’s ringing. “Do you know what time it is?” she asked, trying to sound half asleep. Early ignored her mother’s rude greeting, said, “Yes, mother, I’m sorry. I tried to call you earlier, but you didn’t pick up. I’ll call back tomorrow.” “No, no. I’m awake now. What’s on your“Wheremind?” are you? It sounds like you’re in theMargaretcar.” quickly rolled her window up, cursing silently. “In the car? It’s three o’clock in the morning, Early. I’m home in bed, of course.” An ensuing silence suggested the lie was less than convincing, but Early moved past it. “Well, I only called to say I was thinking about you tonight and realized how much I miss you. And how much I love Sheyou.”waited for Margaret to reply. Feeling a twinge in her chest, Margaret had to pause to think before she could say something her pride would hold against her later. “ Tat’s nice to hear. I love you, too.” “You do?” “Of course. But — ” “ Tat doesn’t mean you forgive me. Is that what you were going to say?” “Something like that.” “Mother, I did my job. Tat’s all I did. In most cases, when I do my job, justice is done. Mistakes are corrected and lives are saved. But I’m not perfect. I can’t al ways see all the ways the work I do can go sideways.”“Except in this case, you could have. I told you how it would go sideways.” “You were guessing. You couldn’t have known. No one could have known.” GAR ANTHONY HAYWOOD

If“Shit!”shehadn’t been on the clock before, she was now. Early would not rest until she found out what Margaret was up to. She would call and keep calling, and text and keep texting, when Margaret refused to an swer — which Margaret would from this point forward — and after that, she would call the police in Arizona. Tey’d wait two days to make sure she was really missing, and then someone would eventually enter Margaret’s condo and fnd the note she’d left for her daughter. After that … Margaret rolled her window down again, needing to feel the night air on her face, and stepped harder on the Camry’s gas. ¤ In Harry Shepard’s experience, people who didn’t write always thought it came easily to those who did. Tey had this idea in their heads that a writer just sat down under a shady tree with his laptop, fipped an inner-switch while sipping a piña cola da, and watched the words fow onto the page, one immaculate, inspired line after another.Harry knew all that was bullshit. In the seven years he’d been writing professionally, he had yet to write a full paragraph that he hadn’t had to drag, kicking and screaming, into existence. Te process of writing for Harry, if it wasn’t comparable to natural childbirth, was at least akin to passing a gallstone, and it pissed him of that some couldn’t look upon what he now did for a living as work. Of course, it only made matters worse that Harry was an ex-cop who wrote novels about a fctional one, Telonious Wendall Coltrane. People assumed Harry got all his story ideas from his own per sonal experiences, or the experiences of cops of his acquaintance, eliminating any need he might otherwise have for an actual imagination. In truth, Harry hadn’t writ ten a book yet that was based to any sub stantial degree on a real-world case in his past. Tat wasn’t his method. Rather than draw upon history, Harry chose instead to reinvent it, using his own experiences as

“I’m not going anywhere. You’re imagining things. Good night, Earlene.” Margaret ended the call.

“Callaccomplish.itwhatyou

“Mother — ”

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS 48

“Mother, what is that? Is that a siren?” Early“It’sasked.nothing. We can talk about all this later. I’m going back to sleep now.”

“Is this why you called, Earlene? So we can have the same old argument?” “No! I just wanted to talk. To see if we could fnd a way to be friends again. Wouldn’t you like that, too?”

But Margaret had known. She hadn’t been the cop who put Anthony Kingman away but she had known enough about his arrest and conviction for the murder of nine-year-old Jamilla Alberts to pre dict what returning him to the streets was likely to

will,” Margaret said. “A guess, intuition. Any way you slice it, you had a chance to trust my judgment and you chose not to. And now we’re both living with the consequences.”

Before Margaret could answer, a sound outside the car became incessant, building from a faint note to a violent wail. It was the Highway Patrol car Margaret had been dreading, only this one, fashing by on the opposite side of the highway, wasn’t coming for her.

“You are in the car. At three o’clock in the morning. Mother, what’s going on? Where are you going?”

GAR ANTHONY HAYWOOD