Piers

scratching

Palakdeep

1/1/25

Piers

scratching

Palakdeep

1/1/25

Palakdeep

@mvlapluma

Aster

ofcers

Editors In Chief

Ashley Kwong

Alyssa Yang

Lead Selection Editor

Selina Wang

Production Manager

Dana Yang

In the Bay Area, winter is a season of crescendoes—sudden downpours and unexpected sunbursts stagger the days to keep them from fowing by, and the quiet tension of fog lingers just long enough to hold the world in suspense. Nature seems to hold its breath, only to exhale in paroxysms—a downpour, a rosy sunrise, a ferce gust of wind—reminding us that even in its stillest season, the world is never truly at rest.

Paroxysm is everywhere. It’s in the frst breath of icy air that jolts you awake on a winter morning and the ferce joy of laughing until you’re breathless. It’s in the fre of an argument that erupts without warning, the food of tears that follows a long-held silence, and the sharp inhale before you leap into the unknown. Just as storms carve new paths through the mountains that surround us, these moments of unrestrained energy leave their mark, reshaping who we are.

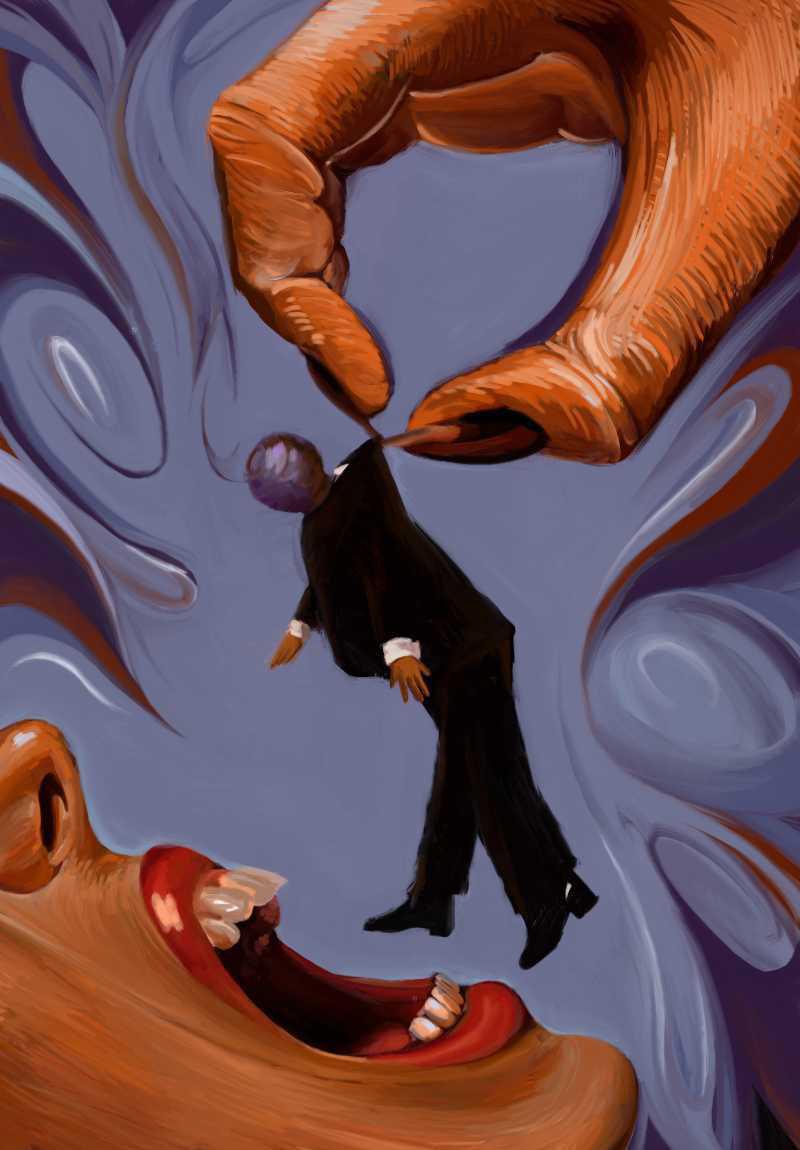

In Volume 6: Paroxysm, we embrace the tumultuous nature of emotion and change. Tis issue is a celebration of crescendos—the turbulence of goodbyes; the exhilaration freworks leave in their wake; the confrontations between ourselves and our inner demons. We unwind the tension of the quiet that comes both before and afer peaks of emotion, ultimately leaving us with a better understanding of our own beginnings.

As you turn these pages, we hope you will fnd echoes of your own life’s paroxysms—those feeting but vivid moments when the world feels most alive. Let this issue remind you that in every outburst, our world forever in emotion also contains the capacity of transforming into something extraordinary.

Ashley Kwong & Alyssa Yang Co-Editor-in-Chiefs

(n.) a sudden attack or violent expression of a particular emotion or activity

PR Managers

Jillian Ju

Giljoon Lee

Webmaster

Katie Wang

Secretary/ Treasurer

Suhana Mahabal

Cover Illustrat by Selina Wang

Writing by Jillian Ju

&thought of you, the details we can’t ft into our pockets. It’s hard to tell if picking up the hat counts as infatuation, some immediate pull I can’t displace—my house is already full of sentimental trash sheathed in dust. Te terrain I know is grief—but then there’s you in your garden, lifing soil into light, making touch a diferent substance. Te hat’s texture reminds me of those painted pots. You gave me one before you lef and I still can’t think of anything to fll it with.

Te facts: I do not have you, but I do have the collection of pens we stole from city hall, two planters occupied by impassive voids, two wallet-sized photos, one polaroid, your overdue Spanish textbook, the hoodie I found the moment your plane landed, a stack of stickers, and your least favorite hat, sitting in some corner where I’ll remember to forget them.

I have been working through all my other issues, like I promised you. I try to eat more. I try to worry less. I am trying not to objectify myself—I am trying to love myself—but sometimes I feel as though all I need to be is the coatrack by our door, the closet in our bedroom, the curtains parting gently in the mornings—I could choke on dedication—I consume old halves of this body, this desiccation—I am subbing out these bones for lampshades by our bedside—

I drop it, even afer we pull it, even afer you reinvent yourself for a night in Pittsburgh or LA or whatever place girls kiss other girls to go back to feeling trapped, feeling mine. You don’t tell me any of this.

Tere’s music at the party, and skin, and both sound the same. I am not listening. I am thinking I should have added embroidery.

I know this decision is one I invented, because I remember this: the last time we guessed gifs, it was winter, and we agreed on twenty questions, fully honest, in your hopes of evading the unexpected. I wanted to keep mine a secret; you could never get behind surprises. Recall that gif was another hat, waiting for you on my desk, packaged in tissue paper and rough around the edges. I’m not sure where it went.

I imagine myself in the department store window. I think of your reflection. I feel like a souvenir.

Suppose I bought it. Here, I’ll say, a few hours afer your fight, I got you something.

So the hat watches you. It watches you walk up stairs and stumble down them, watches you buy mediocre cofee, pops in and out of your backpack, mostly in, sometimes out, hears you say all these pretty things to transient people, nods in tandem with you, nods when you’re ofered a drink, nods when you’re ofered a night out, slips of your head at the party—you’re wearing it backwards as a costume as though this makes you a diferent person, and even afer you drop it it feels like an ache, a headache you can’t pull out, even afer

But you were curious then, and I was indulgent, so we traded guesses like punches—a scarf? A collar for our hypothetical dog?

Your fnal guess was me, and the desperation stung like a confession I was never able to place. I was fattered, really—but, tell me, what kind of surprise would that be?

Suppose I leave it. No issue. I trip past your stuf in the corner and brush the dust of with my lef hand, so when you come home and hold it you’ll know what I did. I put the hoodie on, I put on the old hat too, while I’m at it, hold the pens in one arm and the textbook under the other. I look in the mirror, blink, arrange my hands in new positions to feel intentional for once, like a mannequin dancing with the manager for the night. Te moment she holds both wrists at the same time, making order out of order, stillness out of gesture. I imagine myself in the department store window. I think of your refection. I feel like a souvenir.

In the store, I put the hat down.

You’re back in a few. You ask when we might meet up. I tell you I have a gif for you, again. You ask what it is. A hat, I say. I don’t mention that it’s already yours. I am thinking that I will show up in your hoodie, with my hands up in surrender, so you can reach for my arms, hang your coat over my shoulder before we talk. I’ll take you to the thrif store. I’ll ask you if you want me.

Piers Boyer

Suhana Mahabal

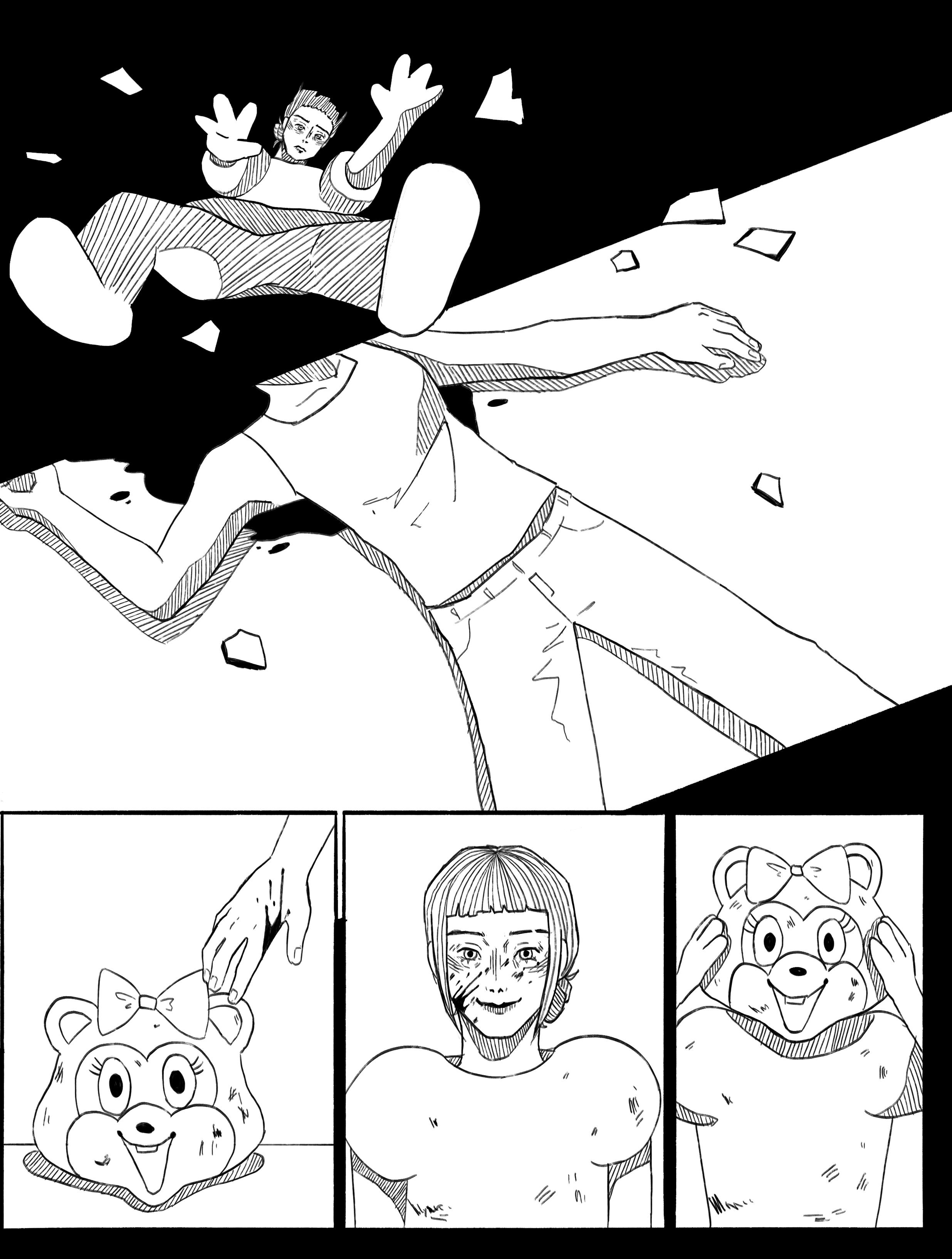

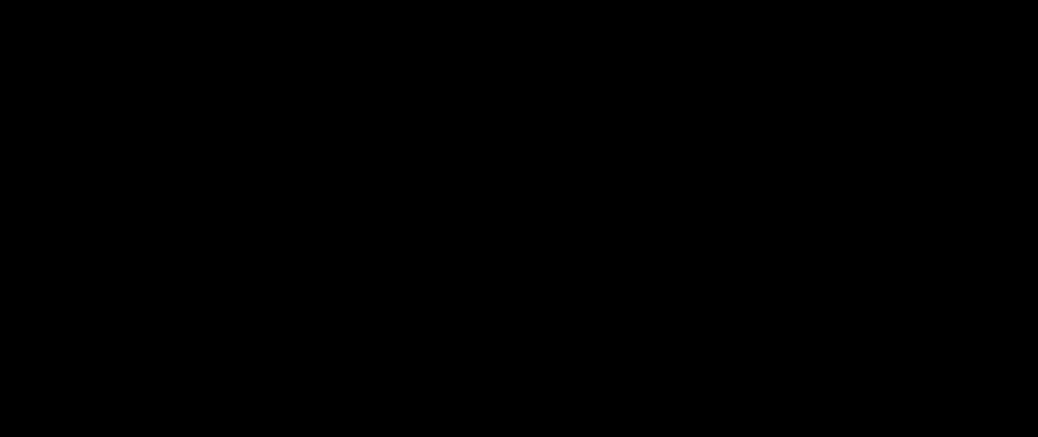

In the dark, I awake with glass shards in my hand. Blood trickles down my palm and into my sleeve as I struggle to sit up, feeling woozy. I blink a few times until my eyes adjust and absorb the destruction I have woken up in.

I stand up, only to fall just a moment later, my knees buckling as I gasp in pain. Blood seeps from the bottom of my foot as I realize I have multiple pieces of glass in my legs. I try to call for help but realize I can barely scream. My throat is dry and scratchy and makes me want to rip it out. Looking around, I realize that I’m in my kitchen and surrounded by a mosaic of broken plates and glasses.

I rise once again, this time grabbing onto a slippery counter, my blood washing it a metallic red. As I hobble through the labyrinth of glass on the tiles, trying not to shriek, I fnd I can’t cry either—my eyes feel hot and raw.

I reach the switch and fip it on, shielding my eyes as the room flls with an ugly fuorescence. Looking upon the scene before me, horror flls me as I stare at the strange pattern of blood and glass and fne china laid before me like a morbid Renaissance painting.

“James?”

I hear a low whisper from the hallway. Turning, I fnd my roommate staring at me with a strange, glazed expression on his face.

me like a zookeeper would watch a violent animal.

Feeling accused, I snap, “What?”

At my tone of voice, he suddenly becomes agitated. “What is wrong with you? Do you not remember what you did last night? Do you not remember?” He steps closer.

My arms feel cold all of a sudden and I wrap my red comforter around me. I can’t remember what I did. I can’t remember my dreams or what I felt or what I did.

. . . what I did . . .

I am hot and cold and angry, so blisteringly angry, and—

“It was scary—it’s like someone turned on a switch in you. You were just sitting there with Nat and Em and then you were rabid—and violent—and god, I was so scared,” Nate was saying, his words becoming rushed and hurried all of a sudden, his body tense as if he might have to run.

I don’t feel a hangover in my limbs. I don’t feel the kind of weak sickliness I do afer I drink.

I feel something under the surface. Something black and clawing and gasping and biting . . .

“James?” he whispers again, his eyes futtering to mine which he can’t seem to meet for more than a few seconds. I step towards him, every movement laborious. He lurches backward, almost slipping on the lacquered foor. His eyes fll with a pure terror, stopping me in my tracks.

“Nate?” I breathe, my voice hoarse. “I don’t know what happened. An earthquake? Was it an earthquake?” I ask, almost begging. I don’t know why I’m begging. I don’t know what happened. But I don’t like the animal look in Nate’s eyes, raw and vulnerable and desperate.

“No—I heard you in the kitchen. You sounded angry —really angry—and you were banging around and there were crashes and screams and I thought maybe—”

He stops at the look in my eyes. He takes a cautious step forward and surveys the damage and my broken body. “Nevermind. Let’s get you cleaned up.” He reaches out to touch my arm but pulls back, and instead beckons me to follow him to the guest bathroom.

Tis time, I wake up in my small bedroom, the weak sun fltering through my curtains. I sit up, my head pounding and my throat raw. Feeling eyes upon me, I turn my gaze to my doorway, where Nate leans against the frame, watching

I feel something under the surface. Something black and clawing and gasping and biting. Something loud and desperate and scratching at the surface—

“I’m moving out now, James. Something is wrong with you.”

It is cold and dull. Tere are metal bars across the wall and the room is gray and dirty and smells faintly. I am sitting in a padded chair when a man walks in. Tere is a gun in his holster. My hand itches. My mind is empty.

. . . I am empty . . .

“I just have a few questions for you, James.” Go ahead.

“Do you know who Nate Grifns is?”

My old roommate. He moved out a few months ago. “Why did he move out?”

“Why were you at his apartment last night?”

. . .

“James.”

. . .

“Why did you push him out of that window, James?

. . . you killed him.”

I don’t know what he’s talking about. I don’t remember anything. I am empty. I look at his pistol. My hand itches.

. . . something is boiling under my skin . . .

I am blistering—burning hot—screaming—insane I am completely normal. I don’t remember anything.

. . . except for his screams as he fell . . . I am completely normal.

Alyssa Yang

1. What is your new life like?

2. What are you waiting for?

3. What comes next?

1. unreal. i don’t know how i got where i am and i’m scared to ask, for fear that i’ll understand the answer. for fear that i am that bug scurrying around in a little glass jar and asking this will open my eyes to the world.

2. what am i even doing? taking a glass of wine out of her hand, gently nudging her into bed saying, it’s alright, it’s alright, i know you’ll be better tomorrow. staying up propping my eyes open until i fall asleep, unaware, and wake up with the realization unpleasant in my mouth.

3. tomorrow i see acquaintances and friends and not-sofriends-anymore and i am afraid i won’t recognize them. how did i get here? scurrying around, over and over, but one day, the jar will break.

Carina Ke

If you could see me now, would you remember this street? It stands dull for most of the year, but tonight it’s been flled with life once more.

Te same lights are hanging, flling the sky with a faint but familiar rainbow glow; they fash, every once in a while, with the same twinkling pattern. Music booms through speakers, loud enough to resonate down the road, yet still too quiet to drown out the calls of nearby vendors and the laughter of the bustling crowd. Te aromas of freshly-fried foods are carried down the path, by people marching towards the river and by the faint winter breeze, overwhelming the scent of freshlyfallen snow.

As I take a seat on the riverbank, I can’t help but think that it is all exactly as it had been last year, when you were there to sit beside me.

Would you remember the freworks?

You could hardly wait for the show to begin.

Looking up in awe as the freworks exploded one by one, you stared at the sky from the moment the frst rocket lef the ground to long afer the last ember had faded, watching for each explosion of color across the inky black sky.

stranger in my own house occurred daily.

Back then, you had not yet started to disappear for hours on end, only to return with less of you than what was there before you lef

Back then, I could still talk to you. I could try to help you fnd your way back to yourself, without becoming yet another thing for you to be scared of.

And yet, even back then, I already knew to wish for the freworks to never end, to cherish that one small moment when you looked at me and you smiled.

Now, it’s all I can do to sit and watch for a minute before I have to leave.

I go to a park nearby, the same one where we had gone afer the show last year, where the fading light blurs the blinding whiteness of the snow. Te fash of the freworks never makes it past the tall line of trees. Even the explosions are mufed in the distance, their sound distorted by the now howling winds.

How could I not like them when they were the reason you looked alive after so long drifting through life in a haze?

Troughout the show, you only spoke once, calling them beautiful. Like fowers, but blooming in the sky, you said. Ten, once you had broken free from your trance, you turned to me for the frst ime that night and asked if I liked them too. And I said I did.

Of course I did. How could I not like them when you had looked forward to seeing them all week? How could I not like them when they were the only way I could convince you to go outside with me at all? How could I not like them when they were the reason you looked alive afer so long drifing through life in a haze?

Would you remember what life used to be like?

Back then, you had only just begun to slip away. It was nothing like the year of exploding dishes and shouts ringing long throughout the night that soon followed. Te year when looks of fear never lef your eyes and declarations that I was a

Te blurring of my senses and the bitter cold. Te knowledge that there are people so close by and yet I am alone. I wonder if this is what you used to feel.

Would you remember your promise?

I’m wearing the bright red scarf you gave me the last time we were here. I’d specifcally remembered to wear it tonight. It was meant to be a Christmas present, you had explained while carefully wrapping it around my neck, but you had only fnished making it in time for the new year.

You told me you worked on it every night while I slept and every day while I went to work. You started and restarted as many times as it took to make it perfect. You said you knew the year had been hard for me, and you asked me to wait for you to get well again. With a gentle whisper, you promised that next year, it would be on time. And next year, when we come again, I had better have a present for you too.

I wanted to tell you then that there was no need to apologize, that I would wait for you as long as you needed, but I didn’t know how much of it I believed myself. As I pull

out your gif now, my hands shake violently, either because of the numbness of my fngers or the words that are fnally building in my lungs.

Last year, I had wanted so badly to say something, anything, to you. And now that I’m fnally ready, you are not here to listen. I’m all alone.

Even with your scarf, the frosty air bites into my neck. I can see the pufs of white that escape with each breath I take, growing bigger, and more frequent. And the silence only grows louder around me.

Maybe that’s why, with one fnal explosion in the distance, one last hurrah for the show, I take a deep breath.

And, for the frst time in a long time, I scream.

If you could see me now, would you remember me?

Shreejay Arja

Ilived for the high notes in sad songs.

It was like the bliss of the ignorant or the rise before a rollercoaster. A brief moment of paradise destined to confront harsh reality.

And for most of my life, I moved to a melancholy tune. I lived in a box, and in my time not staring at a broken clock, I drew angels in my room. Tey always turned out pretty miserable. My crayons kept breaking even if I pressed them lightly, until I was forced to rub the crayons’ dust on the weathered walls using nothing but my fngers. It wasn’t long before my wall was covered in drawings and my hands were a multicolored mess. As the days passed by I closed my eyes to a room full of outstretched wings and stupidly simple faces. Yet, there was not a breath where I felt alone in my room of angels.

Te scariest part of the day was leaving the confnes of my room to the living room. It was even worse than trudging through feet of snow to get to school, because I always felt a diferent kind of cold. Tere was a hole that swallowed me from head to toe when I stared at the papers on the dining table.

I’m coming back. I will,” he said. “In the meantime, I was wondering if you wanted anything.”

He didn’t know how to say goodbye. He didn’t know if it was goodbye. And he looked at me with that look, that stupid look, where he looked at me as if I was a dog and not his son.

“Crayons. I need crayons.”

I could see something more in his expression, but he extended a stif arm to me in a handshake, a proper one, a manly one, one that I took and shook with equal apathy. He looked stupid when he tried to be brave.

Tat day I flled every inch of my room with my angels.

The same hands dirtied of crayon powder days ago—now drenched in his blood.

Letters too complex in fancy-looking writing were printed on the page, along with the infamous blue stamp. I hated that blue stamp, and it seemed my father did too. Afer all, when I returned from school, all I heard were shouts about that paper. My father argued with my mother, frantically waving the papers like a fag. I wish it were a white one. Te bits and pieces I gathered were that my father was leaving, and he didn’t know if he was coming back. He was afraid. My mother was afraid too.

One day my father pulled me aside and grabbed onto my cheeks. He mustered his widest-and fakest smile, before fnally breaking the silence.

“I...might miss your birthday this year, bud. But

Te day afer was when my father was to leave.

As we stood in line, it looked as if someone had died. Hundreds of families with a bitter expression. Crying mothers and confused children. Even though the air was smokey and the black dividers covered their faces, I could still see their tears drip down onto the pavement and roll down into the gutters, like water dripping from the bottom of an icicle. A guard in a disheveled manner, gently clasping a lit cigarette in one hand and clothes in his other hand, shufed in a line next to me, handing out neatly folded green uniforms to the men. On the side of his faded pants lay a beautiful grey pistol, close enough to his hands for him to pull it out and shoot—to end a life with the slip of his fngers. But he didn’t need a gun, for he was like a grim reaper, taking lives as he dropped each single uniform on another broken family. One down. One more; more tears. It wasn’t long before his slow footsteps landed on our family. His eyes barely scanned our trembling hands as he haphazardly threw the clothes upon my father’s arms before moving aside. One down. One more.

Te next family, however, was diferent. As the soldier dropped the uniform on the father’s arms, the youngest child, who looked no older than twelve, grabbed it and with a certain rage, threw it on the snow, dirtying the blanket of ice with debris. Te soldier, who previously had been moving without any care, now stood still in a frightening silence. And then he began cackling, loud as a hyena, before crouching so he looked eye to eye with the boy. He took out his cigar carefully, almost treasuring its heat, before burying the butt of it frmly against the young boy’s arm. He watched the boy yelp in pain sadistically, pressing harder and harder till his screams echoed across the ground. Te boy’s mother fell on her knees, fnally seeing enough, and began begging that he remove his hand.

“Please, remove your hand. He didn’t know what he was doing—he was insolent—we’re sorry. We’re sorry,” she begged, and she prayed, but the man’s hand would not budge.

To see her sickly body fall on the snow and cry as her child screamed. To see the man silent, unable to move in fear. I had never seen such a horrible sight in my solitary life. Families with gaunt bodies and lifeless smiles losing what little they have. Another child having to mourn the alive, not knowing if the next sight of their father was a hug or a body. And so, it was no surprise, even to me, that when the soldier fnally dropped his smoking cigar, now blunt by the boy’s touch, my fngers had already grasped the cold steel of a pistol from within the soldier’s pocket.

Time seemed to pause. My hands, this time holding death, seemingly moved up and up, lifing from the man’s soles to his soul. A beautiful symphony seemed to play. Te hundreds of angels from my bedroom rushed past the forgotten playgrounds and buried notepads, from what ifs and could have beens, and sang zealously a song I had never heard of. Of freedom—of love. Of a world in which we threw our bombs to hell and embraced each other. Of a paradise in the death of this soldier.

But for a moment, the soldier turned around, and in what should have been a primal fear—was instead acceptance. In him was a family, a job, and friends.

Cigar burns on his wrists and glass bottles stacking up. Suitcases and an empty house, walls that used to be full of crayon drawings covered over with harsh paint. A love just like mine.

So just when the highest note was about to play, fnishing the symphony I had sung my entire life, I swerved my gun away from the soldier’s chest, and instead, I misfred. Te smell of gunpowder invaded my nose, and I could not tell if it was the recoil or my heart that created that beat in my head and a voice that seemed to scream “I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry.” No more was the beautiful symphony, and long gone were the angels that lighted my childhood. My high note was gone. Instead was the dust, and behind it, lay my father clutching his chest. “I’m sorry I’m sorry I’m sorry.”

He smiled, and for a moment I saw myself jumping on top of the play structures. Mashing dinosaurs together while he held me close to his arms. I could see him waiting for me to come to the living room, to let myself drop my crayons and draw real memories. I saw him running to me and embracing my empty arms instead of shaking my hands. Te same hands dirtied of crayon powder days ago—now drenched in his blood.

He died for the high notes in sad songs.

Graphics

by

Katie Wang

Graphics by Jillian Ju

Sebastian Chen

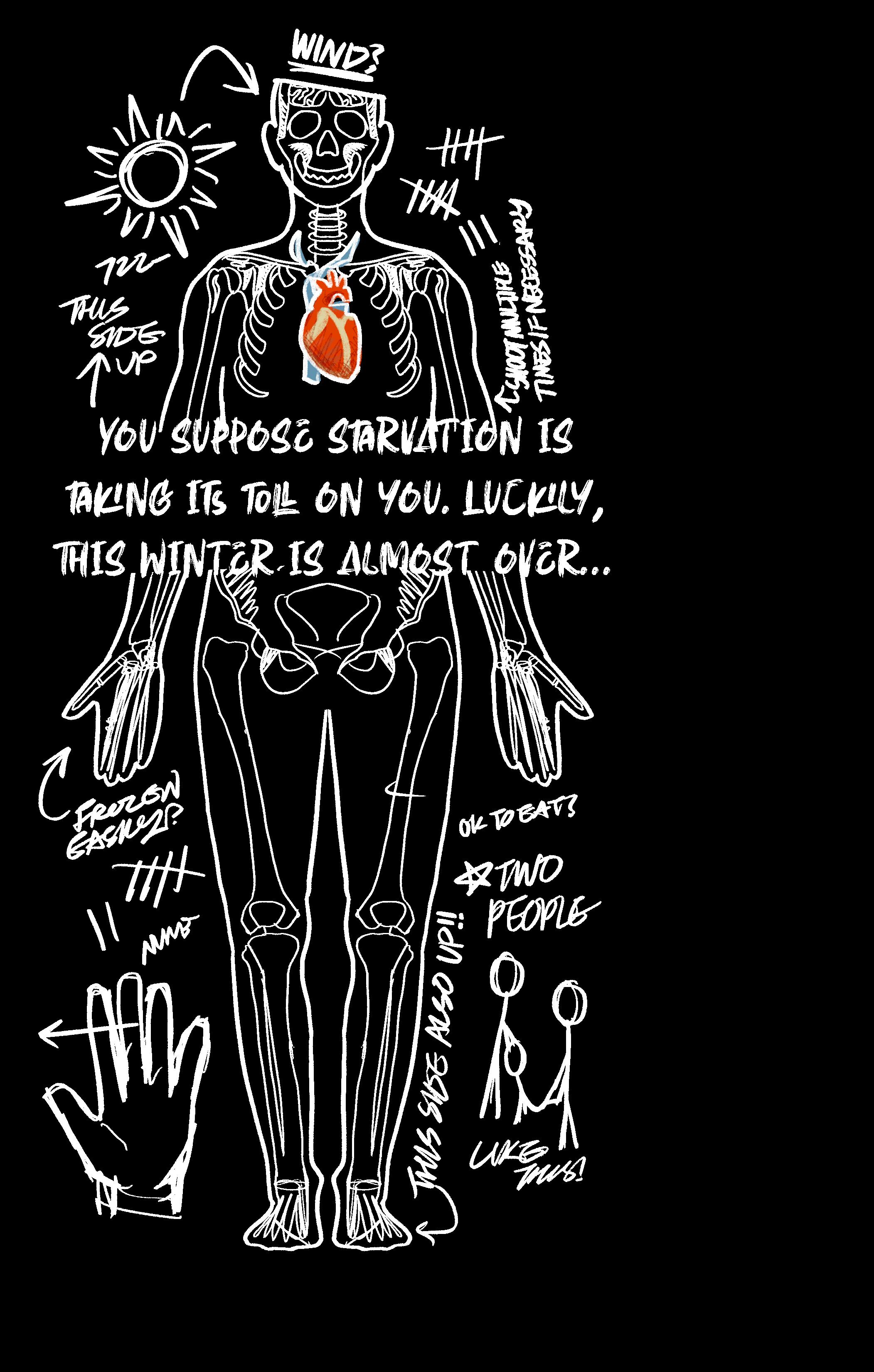

Te dead rise at night. You can hear them moaning through the thick walls of that old house.

Jackson theorizes that they don’t make any sound and it’s just the wind blowing through their bloodless hollow organs; Navia says that they lament their lost lives; Carlos doesn’t say much anymore. He hasn’t been eating what little you’ve all managed to hunt. You have no idea. You all make sure to stay out of their sight.

Te dead burn in the gaze of the sun. Despite the cold and the gloom, they catch fre quickly. A layer of thin fame spreading across their exposed bodies as they fall charred and extinguish, just to rise the next night.

You step outside. Cold but warmer than usual—winter will be letting up soon. Good—famine trails this season, for everyone. In the spring perhaps the four of you can scrape up a garden.

Jackson is half heartedly kicking a blackened body as you approach. You give him a look and he gives you a what? gesture. You grab it by the legs, Jackson hefs the shoulders and you set of to the edge of town.

Te whole place is eerie and abandoned. Nobody has been here possibly since Markhett and Ihland fell. Some of the roofs are caved in, the intact ones are collecting ice and snow, the street lamps are still oil-fueled and there’s absolutely nobody else but your small band, just the evidence of their existence.

You’re at the edge now. Tere’s a river that fows past where a dock and mill were constructed by the townspeople. On that dock you heave the body over and into the waters. Te river moves rather slowly; stops it from freezing but takes a while to carry the body out of sight. Hopefully whatever’s downstream doesn’t mind or care enough.

Te two of you go back for the next one.

Te dead burn again in the day. Snow lightly falls. It’s colder than the day before. You keep watch outside the house and sit on the bitterly cold, icy steps, staring out into the snow. Tere’s a forest through which you came in the fall that you can just barely see through the snow and winter haze.

And something else. A silhouette, almost. Tey take form—two people. It’s been quite a while. You eye each other for a moment. Tey keep walking towards you. You stand. A beat. Te lef fgure pauses and extends their hand towards you. A gunshot rings out.

You scramble inside, barricading the door with antique furniture. You’re unarmed, quarry waiting for its protectors. And wait you will, there’s nothing else you can do. Jackson and Navia will have heard the gunfre; the only question is will they simply—

A thump from outside the house. Alarmingly close. Scufing, rapidly fading away B L A M Silence reclaims its territory. It’s a long while before you hear someone again.

“You okay?” Navia asks, mufed. You move aside the barricade and open the door. Navia pushes into the house next to you, eager for warmth. Her hand brushes against yours; you feel the cold metal of a barrel stripped from your assailant. You look to your lef: there they are.

You look up at the sun. You have enough time for a cooking fre. No time to waste... you grab them by the legs and Jackson heaves their shoulders as you take a detour to the cookhouse. Along the way, you see Carlos eyeing you through a window. He speaks

“You’re a monster.” You didn’t sign up for this either, but this is the dealt hand. Eat, or, well

You all eat in the darkness. All three of you are ravenous. You’re almost surprised at how hungry you are. You suppose starvation is taking its toll on you; luckily, this winter is almost over...

Te door is kicked in to reveal the snowing night; Carlos in the doorway with a weapon drawn—BLAM—Jackson collapses, hand halfway to his holster. Navia scrabbles for her own frearm, just to realize that Carlos had taken possession of it. You try to stand—BLAM—a miss, his hand is shaking too hard—you get up and try to bolt away through the house—BLAM—hit somewhere, bleeding, the ground rising up to meet you... ah—dammit—good

Jackson’s gun kicks one more time in Navia’s hands. Distantly, you hear Carlos swear and a THUMPK. You roll onto your back. Ten minutes and ten seconds pass as Navia rushes over to you. More as she gets something and begins rendering whatever aid to you. You stare up at the ceiling dazed, bleeding... Oh, is this dying? At least she’s not leaving...

“ Tey’re not going to come... are they?” You gasp. Navia shakes her head.

You shudderingly exhale. Yeah, ok Navia somehow seems to be done already.

“Come on, get up we need to get out of here.” She ofers you her hand. You take it.

And she helps you stand. “Let’s go.”

Kai Liu

Elizabeth Yang

in this cold machine world where all i hear is beep-beep-beep and all i see iseyes futter, too weak to wake there’s a frestorm surging through my lungs, they swell and inhale surrender beep my disgust claws at me, hacking away why do i need help breathing? just get the hell away from me

exhale beep why don’t you (leave me) stillstay?

gasping-head-poundingplease let me go home, want to hold my mother’s hand one last time breathe quiet, nothing like imaginedit takes a moment to realize that you no longer lie on that bed of yours

i taste static your fat-line buzzing in my mouth

Rudrika Randad

Icannot sleep. I cannot sleep. I cannot sleep. I hear the whole world, and I cannot sleep.

Te birth of the universe is exploding and spiraling in incandescent rays, electrons course through my veins, and I cannot sleep.

Tere is an electric pole in front of my house. It and I have very little to do with each other, except for the nights when I imagine it’ll come crashing down some day. Tose nights, I undergo a kind of gory metamorphosis. Can you see it? Skin tears to reveal glistening, sinewy red muscle; organs distend, limbs arch, cells morph into splintered exoskeleton; bones of honeycomb and nougat are exposed. Te electric pole will fall, and we will all be lit on fre. Perhaps, then, I will sleep.

Recall, again, what I meant to say. Tere is a dull thrumming in my head, as though there’s a vibrating thread strung through my skull, ear to tortured ear. I would call deafness a respite, if only it were quiet.

It’s an odd anachronism, the way I still hold the phone to my ear like it’s those old, boxy ones. Speaker one end, receiver the other. I think I’m afraid of the electrons. Being the birth of the universe does that to you. Whether the phone is connected or not, it will continue to dial in my head.

Is it a testament to my loneliness, that I perpetually live in the ring of silence, no matter who responds?

It’s neurotic, really. I don’t possess the grace to call it insomnia—I merely don’t sleep. I would rather attribute the buzz to the sounds of electricity than to misfred neurons in my brain. Is it the universe or my soul that is red and hot and furious?

An excerpt from my hippocampus, if you’d care to read: One of these days, molted rock will erupt and lava will pour from every orifce. One of these days, the rocks will explode and there’ll be asteroids suspended in atmospheric silence. It’s the shameful admittance to my delusion that I am a volcano—the buzz is only the rumbling of the Earth as she prepares to destruct in grandeur. It’s voltaic, cacophonic, omnipresent.

I still can’t sleep.

long way to sunrise

Chloe Tsai

Last Tursday, as my footsteps carried me forward, I looked down and saw that the sidewalk was paved and cracked. It felt strange that I could see details such as those, so I cast my gaze upwards and there the sun was, shining so bright it hurt, a deep ache, to stare directly into it.

How peculiar that I already expected the pain.

Someone’s shoulder bumped into mine, causing me to stumble slightly. Tat shoulder was warm—a curiously startling revelation—and it was connected to a body, which was connected to a head; that shoulder was connected to a person. And that person apologized with a good-natured smile, a small nod, before moving on. I stopped and stared long enough for two others to pass me. Suddenly I was consumed by a solid truth—that person had a beating heart and lips that could smile.

Slowly, I turned around, the thought still incomprehensible, and took one more step forward.

Tere were more and more of these epiphanies as I continued to walk. Te sun was bright, yes, but it was also warm. Had I put on sunscreen that morning? Te only trace of the past still-drowsy hour lef on me was the taste of my breakfast—cofee and toast— lingering in my mouth; though there was none of the greasiness or cloying scent that always comes with sunblock clinging to my skin, so I supposed I had not.

ever gone stargazing, despite my reveries that had started perhaps even when I was still a child at the planetarium, staring up at the carefully crafed night sky ablaze with jewels. Each one had been so bafingly far and ancient, and then they had foated down or perhaps I had foated up and there were twinkling hello’s addressed to me, to me, and then they were pulling me along to dance with them and then the crowd and the Earth were submerging, quieting and then—

I had reached out, transfxed, and sofly, sofly touched Jupiter.

But I had, at least, gone to the library last week and lost myself in a whirlwind of dragons that pressed their scaly, too-warm foreheads to mine, of sentient fowers that chittered about the weather, of wings sewn to my back and someone I could elope with. It hadn’t been a sad boovk, but it had felt so real, and when I emerged there had been tears on my face that I hadn’t even noticed I was shedding.

I had reached out, transfixed, and softly, softly touched Jupiter.

Te trees had trunks that were so intricately and uniquely textured, small crevices, larger valleys, some edges splintered, others moist and sof. I could already imagine what it would feel like to run my hands across the bark, but I didn’t.

A bird fitted past overhead. I recognized the feathers, white and gray and black, and I recognized the chirp. It was a small bird, and I watched as it perched on a branch that shivered more than swayed under its weight.

A single leaf drifed to the ground, gold at the edges.

Te little bird futtered its wings and twitched its little tail and peeped a single, high note. My mother loved that bird. Just a week ago I had dreamt that I was little again and we were at the park. She was holding my hand and with the other, she had pointed up at a nest within the branches and said, look, there they are. Te sky had been so brilliantly blue behind the limbs of the trees.

Te bird chirped once more and fitted away, just as quickly as it had landed, leaving the branch swaying anew. Te bird. I didn’t even know the name of its species—I had simply never bothered to learn it.

Nor had I ever bothered to watch a sunset from start to fnish, no matter how captivating it was. Nor had I

I had watched in fascination as an ant hoisted a crumb above its head and went along its own little invisible path. I had laughed until my face scrunched up and there were stitches in my stomach and I couldn’t breathe and not a single sound came out of my mouth. I had woken up earlier than everyone else and went to the backyard and saw my breath in the air, reached out and felt it; perhaps it had held my hand.

I had heard a tune that sofly turned my world inside out, and it was right there, right there from a busker in the middle of the street, had wondered why everyone else walked past him without a second glance, why my parents pulled me along before I could properly savor his music, why I never saw him again.

I had lost my frst tooth. Wondered what it would be like to fy. Shufed my feet every night as I brushed my teeth. Watched the ocean waves. Picked a daisy and spun the stem between my fngers until it quietly forgot its shape and crumbled into emerald stains on my skin. Hummed that wonderful tune and mused where the busker was now and why he looked so sad when his music was so lovely and if he was smiling at that very second because somehow… somehow I felt that he deserved to be happy.

And I had wondered, when it was just me and the moon, if perhaps there had been nothing before all of this. No music, no smiles, no stars, no sunlight…

Just nothing.

But in that moment, at least, the sidewalk beneath my feet was paved and cracked, the trees had branches that

shivered to the whims of the birds, the sun was so bright it hurt and the sky was blue and I was alive, alive, alive beneath it… I looked down at my hand and fexed my fngers. Clenched and unclenched my fst. I was real and I was here— perhaps I had never been more aware of the fact and that was why it felt so unsettling yet idyllic. Like something pure and signifcant and beautiful, the ocean or the Milky Way. But it was just me, just a human, a human with a beating heart and lips that could smile.

And yet I have never wanted to be alive as much as I had last Tursday.

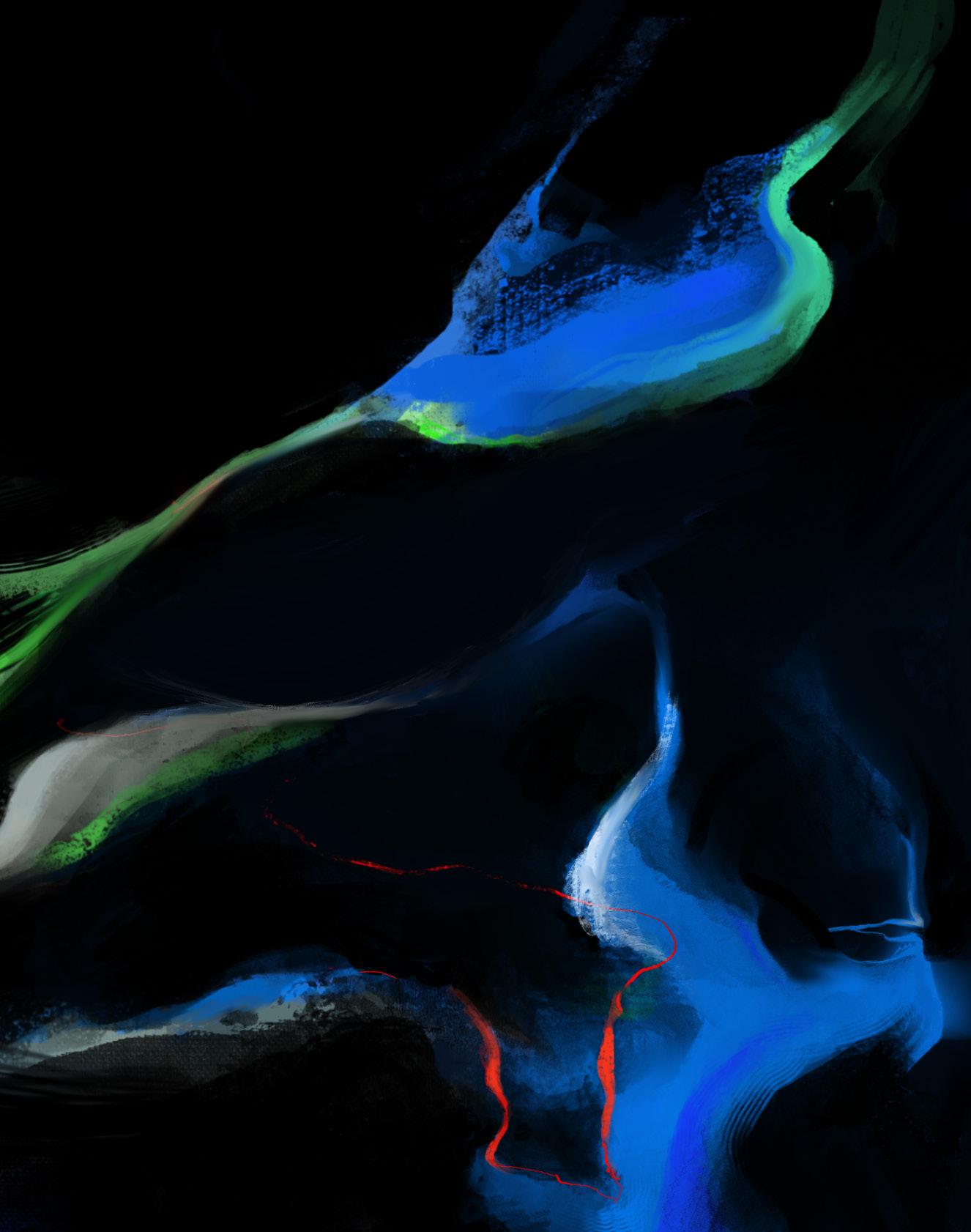

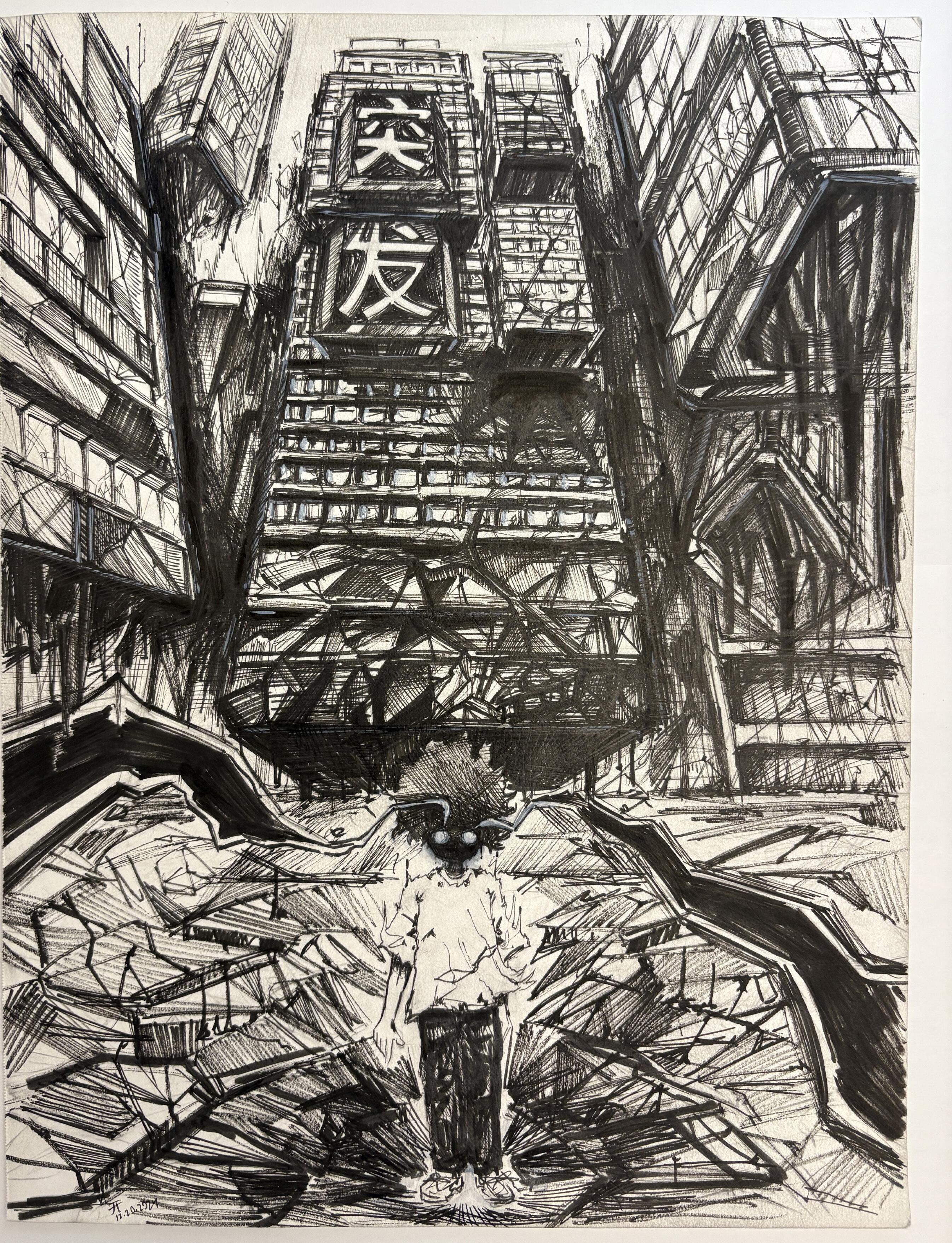

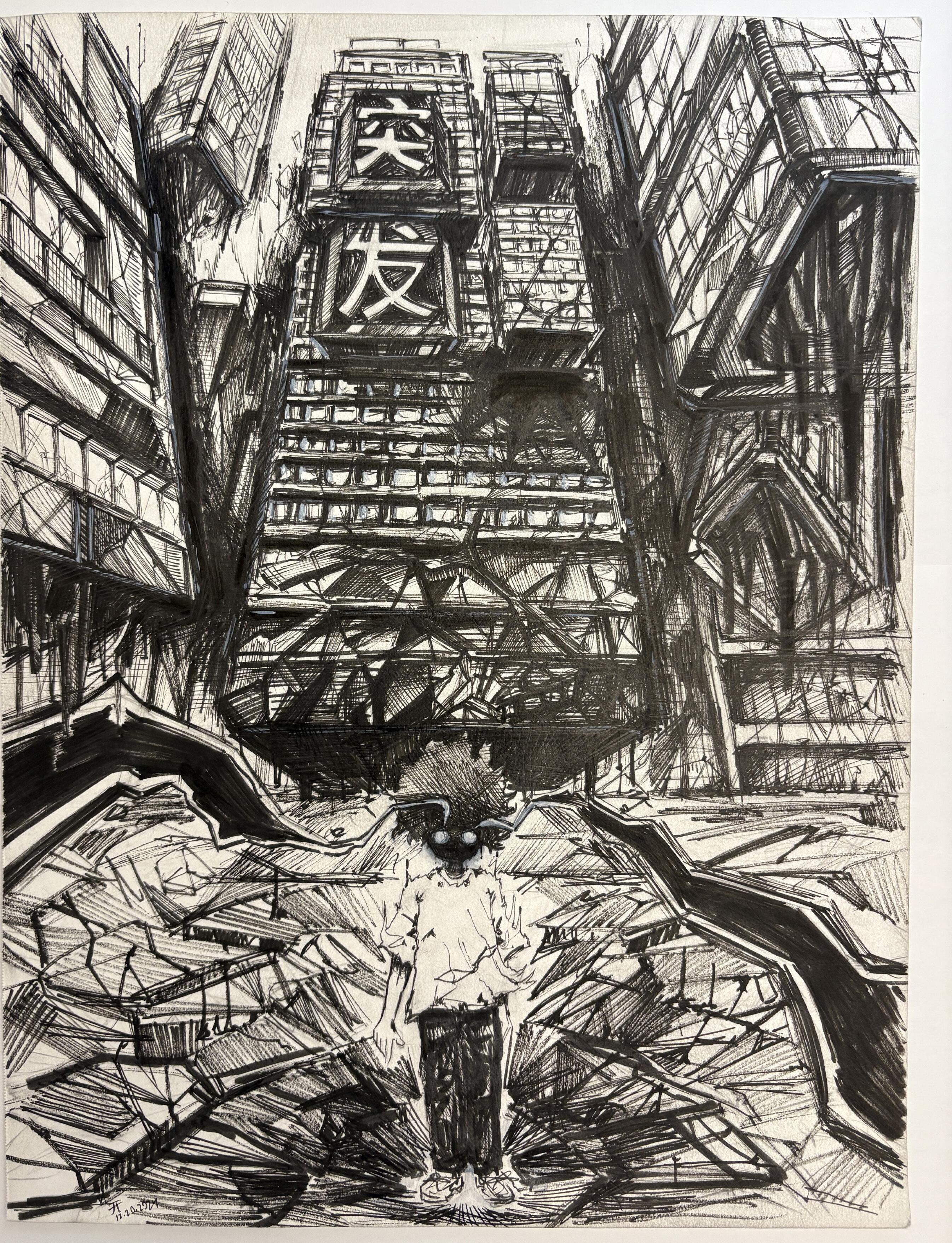

Art by Selina Wang / Written by Giljoon Lee & Alyssa Yang

*the following work contains graphic and potentially disturbing imagery. Viewer discretion advised

Atharv Dirisala

a swarm of steel silently approaching this invisible island nestled in the bosom

snow sofly falls on your hair and i can’t stop wondering why you? why not me?

so heartless— “... mom?” don’t say that to me when you’re going to leave me when they’re going to take you away they’re moving faster and faster and i’m asphyxiating there’s no time to breathe

in a blink gone the skies rip open where did you go and we’re at god’s mercy the breeze blurs my eyes to catch your sight the winds whip the waters panic kills my voice to scream for you the sea swerves the ships

it’s you they want so it’s me they’ll get come back to me i’m begging you and let me say goodbye the snow’s melting or is that just tears knowing they’ll tear you away from me?

their fags ripped to bits i can fnally see you i hold you in an embrace so they can’t take you away we’ll be together forever

1/1/25 at 12:41 am

Sophia D’sa

The person you are trying to reach is not available. At the pound, please record your message.

###

I found our old recipe book today. As much as it may surprise you, I haven’t used the oven in this apartment yet, so I was looking for something to make today. I fipped to the cinnamon roll page—your handwriting is all over that one. Te loops on your y’s in that smooth purple pen. Te pale blue sticky notes with scaled measurements so you wouldn’t have to “sufer the math.” It’s been a while since I remembered you like that.

I don’t know if you remember me at all, honestly. It’s okay if you don’t—I had forgotten you for years, but some parts I didn’t realize I was holding on to. I still hate dragon fruit but I buy it when it’s in season because I always used to keep it stocked for your smoothies. Tat planter you made me at your frst pottery class is still on my windowsill. I don’t have the patience to grow plants anymore, but the planter is a piece of home. Te windowsill feels empty without it.

I told myself if you really cared about us, you’d fght harder. You’d call me or text or even just send a Happy Birthday, something to tell me you remembered. But I was so used to having you around every day that even when you were trying, even when you did everything I could’ve asked for, it felt like too little. I know you hate excuses, but that’s mine. I just wanted you to stay. I wasn’t ready to accept anything less, and responding felt like settling.

I didn’t want to think about you afer you lef. I saw reminders of you everywhere for months: your favorite fowers on the side of the road, a new stall with your favorite snacks, even people at parties who looked like you. And every time it just made me think of everything I could’ve had and everything we said we would be.

I know you hate excuses, but that’s mine. I just wanted you to stay.

I always thought that maybe one day I’d feel ready to fnd you again and we could catch up like the old friends we are. I remember the voice memos I recorded in those frst few months, the ones I pretended were voicemails before I had the courage to record a real one. Eventually I started to tell you about my life, all the places I went and people I met. I know you’d love it here.

I don’t think I ever really told you how I felt when you moved, how alone I was. You were always saying how badly you wanted to get out of here and it was hard to believe that you’d leave everything behind and still want me. So I assumed that was it for us and stopped attaching myself to you so much. I fgured it would hurt less if I made myself easy to leave.

Was I wrong? If I’d replied to your texts more those frst few months, would we have stayed friends? Would you have cared enough to tell me when you moved and changed your number? To come see me, maybe bake something in my new apartment together? To take me around your city for a day or two? Or was I really just an extra to you, part of the life you packed up and sent to Goodwill?

I watched a movie the other night, curled up under that rust colored blanket you knitted for us, the one that’s the reason I learned to wash wool. It was about two friends reconnecting afer decades apart and confronting that the versions of them that loved each other were just long-gone clueless children. I think we were a little like that—friends because we liked the same things at the same time even though we weren’t headed in the same direction.

I don’t know if this mic is good enough for you to hear them, but the freworks just fnished outside, and I think that’s my cue to go. Yours should be starting soon—they probably look the same, but send me a picture anyway. One last one.

You mailed me a jar of olives & I would’ve released my doves, but they are already cremated ash scattered in the gently lapping waves of the sea— ceasefres are easier than peace.

I think we are like seawater, you and I—homogeneous until fre comes. Ten I transform into something you’ve never known & you’re lef behind, waiting for me to cool down & return to what I was before. It might happen (but you should know I’m never coming home).

Home was a house of cards—now it’s scattered across the table. If I stacked and straightened it with a tap to each side we would hear the sound of the red & black court locked into disarray. Te last time we crumbled, you said it would be the last time we rebuilt

Arielle Fam

Graphics by Giljoon Lee

Photographs I (don’t) remember taking spread before me & I put a lighter to each and every one. Tey burned into my I. Burning

I hate how the second I felt a glimmer of warmth I leapt into the hearth. I realised I was burning once my skin was charred and peeling & my nerves alight with fame; it was bloodless so I didn’t know if it was agony or bliss I felt— was it really pain if I didn’t see red?

Arielle Fam

I love your eyes because they are not so intense, like an echo of daylight in winter. Tere is something so mesmerising about the way your gaze locks on mine; I blink and you’re a fraction closer. Is this what moths see before they die—blinding light beckoning them home?

A ghost-light brushes your just-breathing corpse; all the while I sink knee-deep into damp earth. Tis is why I don’t believe in your God’s justice: the heavens know where your shadows lie and bless you still with the moon as your bride. As I prepare for our funeral I see you kiss her back, but your eyes lock with mine & my pulse stutters.

Remember when you were a stone’s throw away? Now throwing stones is all we do. My palms know nothing but the sharp edges of a rock (and the touch of your skin, but now that is a ghost haunting the crevices in mine).

We lie together like oil lies with water, touching everywhere save for our hands. We ought to mix— neither of us are drowning men, heads bobbing just below the surface—and yet I feel like a sinking stone in your presence.

Tere is a slow beauty in the way you sleep, your breaths like the ocean washing away my sins; existing in your arms is my baptism & your lips anoint me like oil.