THE ARTS ARCHIVE

A brief discussion of why we assume the white male as our default

A review of this groundbreaking collection of women artists in Britain from 1520 to 1920 3

Explore Judy Chicago’s retrospective, focusing on her radical manuscript 4

Discover this photographer’s crucially works exposing the horrors of Apartheid

7

Learn about the challenging story behind one of the most iconic contemporary artists of our time

An introduction to Muholi’s powerful photography, documenting black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people's lives in South Africa

Hear about the stories of the women only remembered for the men in their lives

A few ideas of ways to engage with art beyond the gallery wall, from new films and documentaries to insightful books

16

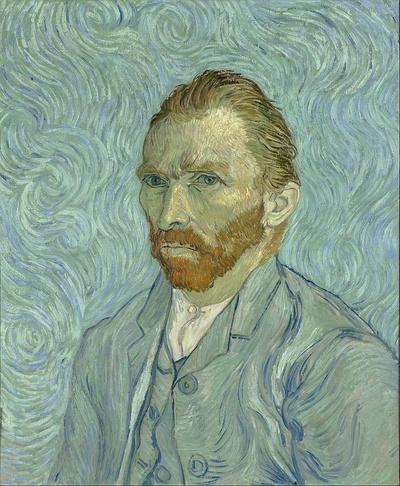

Ask anyone to name a famous artist and you’ll hear a whole range of answers. Michelangelo, Da Vinci, Van Gogh, Picasso. Now there is nothing wrong with any of these answers: they are truly great artists, masters of their craft, innovative creators who each changed the course of art history. But, there’s something else that these names all have in common, and it’s not just their artistic abilities: they are all white men. So why is public knowledge of artists dominated by the western male?

A recent study found that 85.4% of the works in the collections of all major US museums belong to white artists, and 87.4% are by men. Data from the Tate galleries suggests that UK institutions don’t do much better: just 15% of the artists in the Tate’s permanent collection were women in 2014. Therefore, it can be no surprise that the white male has become our cultural default, when it is seemingly all we know and are surrounded by. The problem is that museums take this majority for granted, as ‘neutral, objective, normal, professional and high quality’, thereby making art made by men appear as the default and the norm. This is all part of a system of white supremacy that perpetuates oppression, racism, sexism, and colonialism.

African American artists: 1.2%

Asian artists: 9%

Hispanic and Latinx artists: 2.8%

White supremacy describes the culture we live in, a culture that positions white people and all that is associated with them as ideal, defining this as the norm or standard for human, and people of colour as a deviation from that norm. In fact, for most of our history the very category ‘human’ hasn’t embraced people of colour, nor anyone who wasn’t male. White supremacy thrives within this tyranny of the universal, the neutral, the apolitical, the fair and balanced, and the objective. Its pervasive hold is arguably one of the single greatest threats to the deep, transformational change that is needed within museums today, yet the simple act of recognising that ‘museums are not neutral’ could be a meaningful and urgent step toward gaining awareness of the powerful role that white supremacy and white dominant culture play within our institutions. It is a crucial step toward recognising one’s own role in questioning it, interrupting it, and being a part of taking transformative action to replace it.

Of course in the last few years, there has been a huge effort to rectify this imbalance with many galleries and museums focusing their exhibitions and acquisitions on artists who previously were shut out of the artistic sphere. Yet one may wonder, by introducing these works to counter the imbalance, does this only reinforce the white male as the norm? And therefore does that make us believe that art created by a minority group is ‘other’, and by extension not representative of the human condition? The problem of white supremacy in the art world and beyond is a never ending issue that doesn’t quite seem to have a solution yet, but all one can do is embrace all voices so that we can slowly but surely chip away at this exclusive narrative.

Roshy Orr

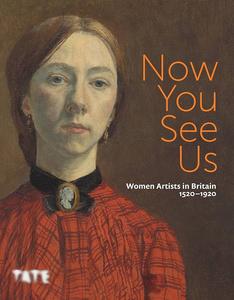

Spanning 400 years of art history, Tate Britain’s Now You See Us is a revelation, showcasing the extraordinary contributions of over 100 women artists who defied societal norms. Featuring over 150 works by trailblazing women like Mary Beale, Angelica Kauffman, Elizabeth Butler, and Laura Knight, each piece offers a window into the struggles and triumphs of these remarkable artists. Their stories remind us of the hardwon freedoms women enjoy today, thanks to their relentless efforts to fight for their right to an art education, to participate in exhibitions, and to make a career in the arts. Tate’s mission was to redress the huge gender imbalance in British art history by ensuring these artists are not only seen but remembered.

The exhibition begins with two striking works by Italian artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1652), both her powerful Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting and Susanna and the Elders (1638-40). In her depiction of herself as the essential artist, her head is cocked to one side as she lunged forward utterly absorbed in her work as she reaches out a bared arm to add a splash of paint to the canvas she fiercely works on. This emanates her formidable presence and is a testament to female resilience in the face of adversity. The exhibition is carefully curated so that for every Gentileschi, there are another 10 unknown artists on display, thereby signalling a shift from the view that such women artists were mere anomalies, and the rest of women could not be artistic geniuses. Her second work Susanna and the Elders, which uses an Old Testament narrative to suggest the difficulty of being a woman in a dangerous, patriarchal society, is more typical of the treatment of works by women throughout history. The work, first painted for Queen Henrietta, was lost in storage for years, only recognised as a Gentileschi in 2023, evidencing the fluctuation of her eminence through time, unlike her male peers. If a work by someone who equaled Caravaggio in skill could be lost and forgotten, it becomes all too clear how an entire gender’s artistic production could be suppressed. But this exhibition attempts to redress this.

As one of the first women members of the Royal Academy of Arts, Angelica Kauffman’s depictions of historical, classical, and mythological narratives — regarded as the highest forms of art — received great critical attention in her day. Commissioned in 1778 to paint the four Elements of Art for the RA’s Council Chamber in Somerset House, Kauffman portrayed Invention as a woman, a highly provocative move since only men were considered capable of creative imagination.

Indeed, she was criticised for her somewhat androgynous portrayals of men, but given that women were barred from life drawing classes until 1893, surely this is to be expected. When Kauffman left London for Rome, Maria Cosway inherited her spot as a high profile exhibitor at the RA’s annual exhibitions. When it was shown in 1782, her painting of the Duchess of Devonshire as Cynthia, the Moon Goddess caused a sensation. The huge canvas shows the Duchess swathed in grey blue clouds and striding through the air, in a frightfully mesmerising and memorable mythical image. The other female RA member was Mary Moser, whose career was far less established since her focus on flowers and botanical paintings was regarded as inferior. To combat art history’s systemic exclusion of this genre, deemed suitable for ladies, the exhibition includes an entire room dedicated to scientifically accurate botanical paintings, including flamboyant florals by Mary Delaney, who began paintings in her seventies.

Among the women artists who were usually rebuffed for their ‘lower arts’, such as pastel and watercolour painting, miniatures, embroidery, and needlework, Sarah Biffin (1784-1850) had no arms or legs, so she learned to sew, write, and paint using her mouth and shoulder. Emily Mary Osborn's 1857 painting, Nameless and Friendless encapsulates the struggle many women faced, restricted by endless rules preventing their artistic production, in its portrayal of a lonely woman, anxiously awaiting judgment from an art dealer, surrounded by indifferent men. This painting is a poignant reminder of the invisibility and lack of agency experienced by women in a male-dominated society.

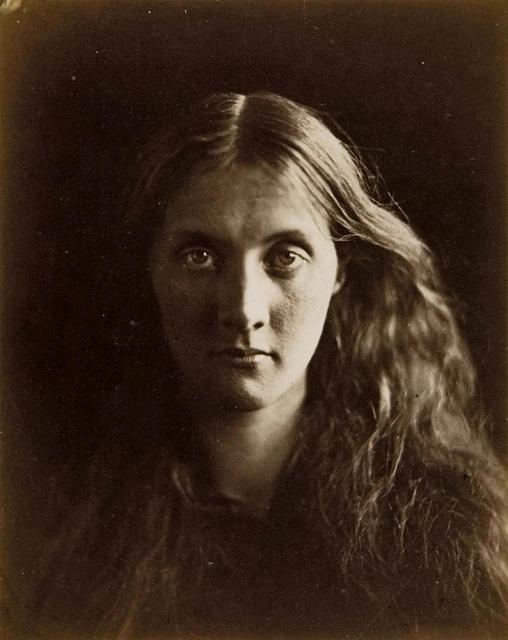

As we progress through the exhibition, we witness a transformation in art style, reflecting the gradual changes in women's rights over time. The works of artists like Mary Beale, whose meticulous records are kept by her husband, illustrate her professional achievements and highlight the perseverance required to succeed. These women forged ahead despite systemic barriers, often finding ingenious ways to navigate their restrictions. By the Victorian era, women artists began to gain more visibility and opportunities, although they still faced significant challenges. Florence Claxton's satirical piece, Woman's Work, humorously critiques the limited roles available to women, making light of grim realities through dark comedy. One of the exhibition's most poignant moments is Mary Grace's self-portrait, which captures her confident gaze and unwavering determination to succeed in a maledominated field. Toward the end of the exhibition, visitors encounter a captivating section on photography. Delving into the early days of this medium, it is fascinating to learn how photography revolutionised artistic expression, offering new avenues for creativity. Pioneering women like Clementina Hawarden and Julia Margaret Cameron embraced this new medium, excelling in a rapidly evolving field.

The exhibition's final room explores modernity, showcasing how women forged their own paths and pursued careers with purpose and confidence. This progression is palpable, as you move from room to room, seeing how each generation of women artists built upon the foundations laid by their predecessors. By the end of the exhibition, women could now vote, travel, earn money, and express themselves as never before, cleverly highlighting how far women have come, both in art and society, after overcoming adversity and refusing to let societal rules stifle their creativity. Therefore, this exhibition is a powerful reminder that the fight for gender equality in the art world is far from over. With each new generation of artists, we move closer to a future where women's contributions are recognised and valued equally.

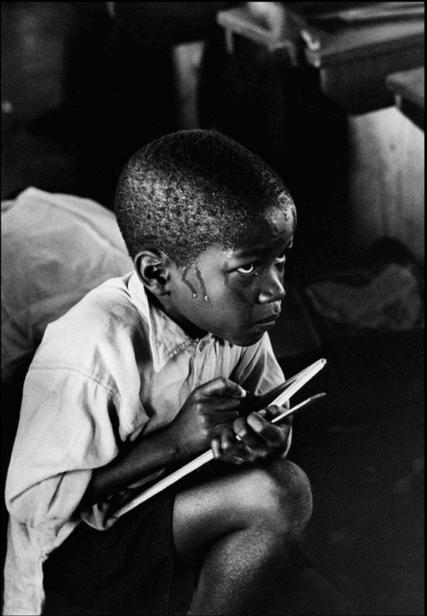

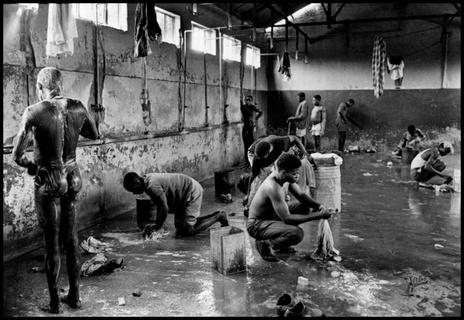

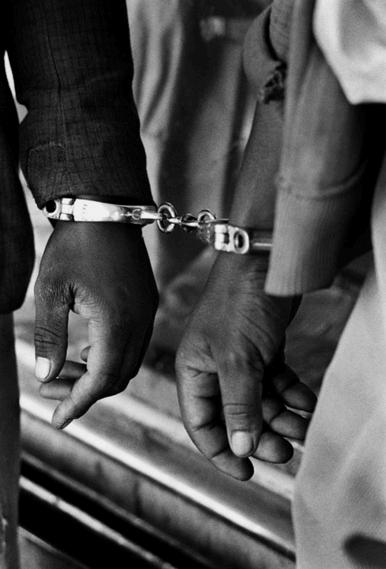

Born in South Africa in 1940, Cole grew up experiencing the extreme racism and segregation that was present in his home country, facing it directly when he was forced to leave school due to the 1953 Bantu Education Act. This enforced segregation within the schooling system, aiming to train the children for manual labour and menial jobs that the government deemed suitable for those of their race, and it was explicitly intended to inculcate the idea that black people were to accept being subservient to white.

Self-taught in photography, Cole began his career at Drum magazine in 1958, before becoming a freelance photojournalist where his photography focused largely on the black community. While working at Drum, Cole met with other young black South Africans in the arts sphere —journalists, photographers and jazz musicians — who were all involved in the anti-apartheid movement. This exposure to political ideas influenced his decision to expose to the daily evils and social effects of the apartheid.

The apartheid began in 1948 and was a system of institutionalised racial segregation, underpinned by white minority rule. It meant that anyone who was not classified as white was actively oppressed by the regime. The Population Registration Act of 1950 meant that citizens were segregated into four racial groups Black, White, Coloured and Indian. Classified through a variety of tests by apartheid officials, Cole was able to trick the Race Classification Board. One of these tests was the pencil test where a pencil was pushed into the hair and if it fell out, the person was classified as white (and their hair was classified as straight rather than curly, kinky or coily). Cole tricked them by straightening his hair and changing his name from Kole to Cole which meant he was classified as coloured rather than black. Because of the strict segregation laws, those classified as black would have been unable to travel or photograph as easily.

However, by 1966 it was becoming increasingly hard for Cole to work in South Africa. He took a lot of risks with some of the photos he shot, many of which could have resulted in life imprisonment –especially those taken in prisons or mines featuring people undergoing inhumane medical checks and other humiliations. Seeking to leave South Africa, he fled to New York, taking his photographs with him. The result was his book ‘House of Bondage’ published in 1967, chronicling the humiliation and horrors experienced throughout South Africa. House of Bondage was the product of six years of research, photographing, and editing. Each of the book’s chapters represents a different aspect of life under apartheid, illustrating segregation’s impact on housing, education, employment, childcare, medical care, and daily life. The book was consequently banned in South Africa and in 1968 the apartheid regime permanently banned him in perpetuity and stripped him of his South African passport. However, it continues to be a powerful visual testimony and archive of the stories and memories of the Black South African population during apartheid.

Cole died from colon cancer in New York City on 18 February 1990 at the age of 49, and it was readily assumed that the vast majority of his negatives had been lost and thus his photos were gone forever. However, in 2018, 60,000 negatives were found in a bank vault in Stockholm. As a result, House of Bondage, out of print since the 1980s, was republished in 2022, making its monumental achievement widely accessible once again. To experience his works in person, you can visit his exhibition at the Photographer's Gallery.

"Three hundred years of white supremacy in South Africa have placed us in bondage, stripped us of our dignity, robbed us of our self-esteem and surrounded us with hate."

Maddie Parker

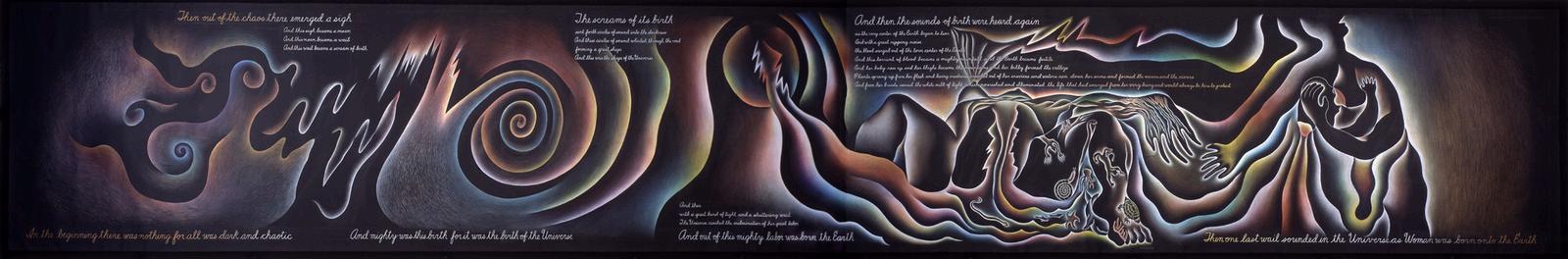

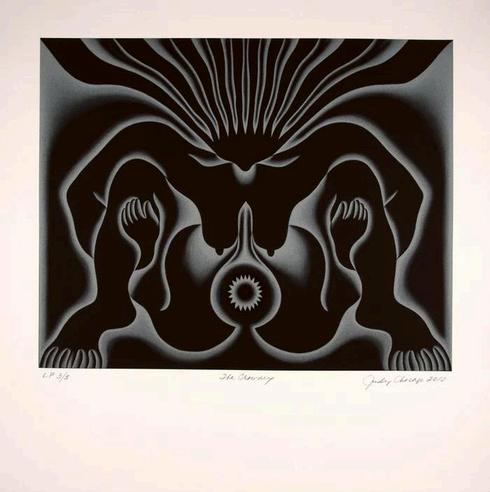

The year is 1974 and Judy Chicago has begun working on her monumental feminist installation The Dinner Party, which subverts the male dominated iconography of The Last Supper, instead commemorating 39 important but overlooked women in history through personalised place settings on the massive ceremonial banquet. The settings consist of embroidered runners, gold chalices and utensils, and china-painted porcelain plates with raised central motifs that are based on vulvar and butterfly forms and rendered in styles appropriate to the individual women being honoured. The names of another 999 women are inscribed in gold on the white tile floor below the triangular table. Whilst this immense artwork is permanently located at the Centre for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, the exhibition features a documentary form of it. However, this is not the main focus: instead her psychedelic paintings and drawings take precedence, outlining decades of revolutionary feminist practice and mapping out themes explored within her until recently unpublished manuscript Revelations, for which this exhibition takes its name. Written at the same time as origins of the The Dinner Party began to emerge, it offers a radical retelling of mythological creation based on Chicago’s extensive research into goddess worship and women’s history.

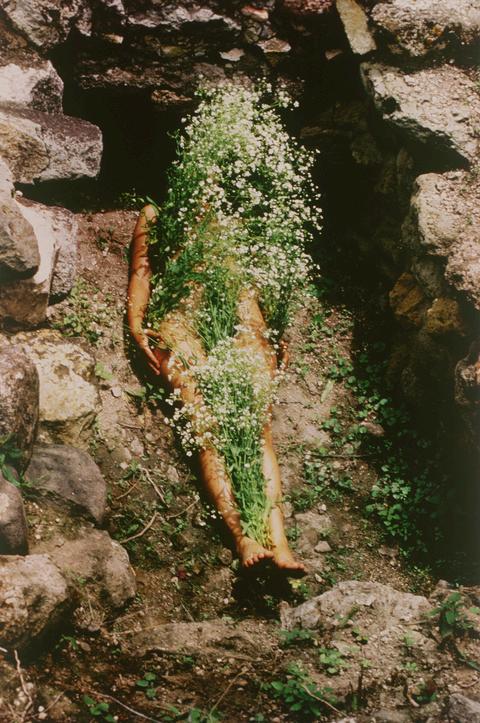

The exhibition opens with In the Beginning, a huge nine-metre-long drawing in Prismacolor pencils which reimagines the patriarchal Genesis account of creation from a female perspective. Emerging from her psychedelic, swirling forms is both a landscape and a woman’s body, inscribed with a new tale of creation, challenging the transmutation from female to male deities: “her body rose up and her thighs became the mountains and her belly formed the valleys. Plants sprang up from her flesh, and living creatures crawled out of her crevices, and waters ran down her arms and formed the oceans and the rivers”. Similar goddess iconography used to express the divine was also employed by eco feminist Monica Sjöö in her equally ethereal works which also likened the destruction of the planet to the oppression of women in society.

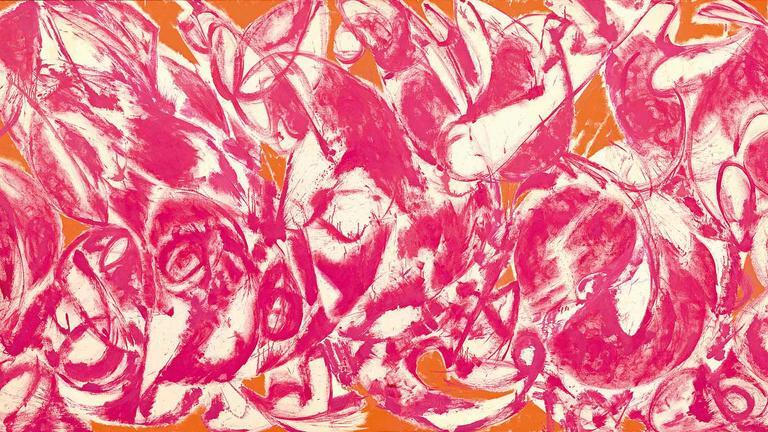

Chicago was radicalised in the 1960s by negative responses to her feminist version of minimalism On show are the geometric gradient-coloured abstractions she made soon after graduating from the University of California in 1964, that fan out from a central slit, making them appear to open and close, through Birth Project, which addresses the “iconographic void” of birth in the Western art-historical canon. Hard-edges are softened by glowing candy colours and, soon, straight lines began to morph into ripples and furls.

The series PowerPlay (1982-87) signifies a pivotal shift for Chicago as she began to interrogate notions of power, social conditioning, and the construct of masculinity The artist deliberately uses sprayed acrylic and oil in homage to the "heroic Renaissance paintings" made by male artists, rendering her male subjects as grotesque, thereby subverting typical depictions of masculinity as expressed in Western art. She then moves her focus to apocalyptic visions of society being destroyed, nature being eviscerated and women being exploited; her art is her response, and it’s a vicious, technicolour, satirical attack on the patriarchy, shot through with ecological activism.

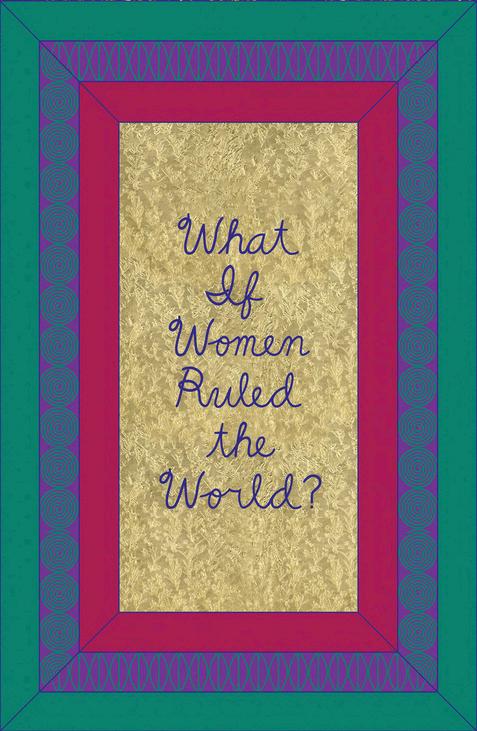

The final work is a vast tapestry filled with quotes from people answering the question: ‘what if women ruled the world?’ The answers, from people all over the world, imagine a society where ‘there would be considerably less violence’ and ‘our culture would reward gentleness’, a world without private property or war or environmental destruction Throughout her career, Chicago has worked with an endless array of media, particularly those which were overlooked as merely women’s work in the case of tapestry, to assert its importance in the art world Although the message of this piece may be overly simplistic and optimistic, a real sense of power and truth emanates from it, encouraging us as we go out into the world to reflect on the power that lies with feminism.

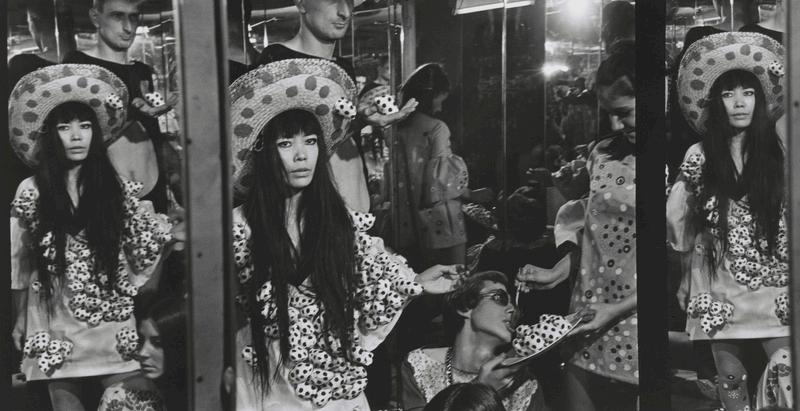

In the world of contemporary art, few have sparked as much intrigue and admiration as Yayoi Kusama. She is a pioneer in every sense of the word - a visionary who has spent countless years using her art to break boundaries, challenge the norms, and define what it means to be an artist. Although she is now one of the most influential and recognised artists in the world, her journey as a Japanese woman into the male-dominated art world was filled with many challenges including gender and racial discrimination. Her work is repetitive and psychedelic and evokes themes of psychology, feminism, obsession, creation and intense self-reflection.

However it is not just her gender and race that led to challenges. She started experiencing vivid hallucinations of flashing lights, auras and dense fields of dots at the age of 10, which soon became the foundation for her art. Clearly, her art was not just a profession but an expression of her mental struggles and turmoil, in a way that words could not match. Beyond mental health struggles, her upbringing was marked by conservative values, which greatly discouraged her artistic practice, and the cold relationship between her parents hugely impacted her.

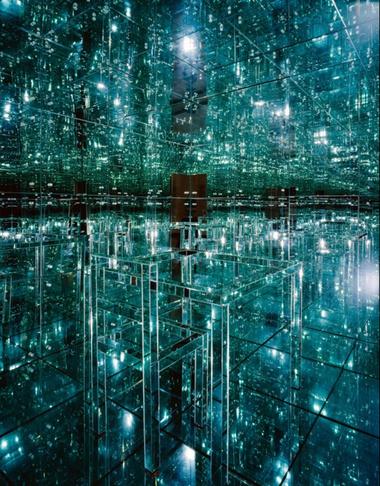

In 1958, Kusama bravely escaped Japan and made it to New York in the hope of finding success, but only confronted more difficulty. A highly male dominated field, not only did she struggle to exhibit, but her very own ideas were stolen by male artists and taken for their own. Claes Oldenburg was 'inspired' by her fabric phallic couch to start creating the soft sculpture for which he would become world famous, while Andy Warhol would copy her innovative idea of creating repeated images of the sole exhibit in her One Thousand Boats installation for his Cow Wallpaper. Worse still, in 1965 Kusama created the first mirrored room environment at the Castellane Gallery in New York, yet only a few months later, in a complete change of artistic direction, avant-garde artist Lucas Samaras exhibited his own mirrored installation at the far more prestigious Pace Gallery. Distraught by this injustice, Kusama threw herself from the window of her apartment.

“Our earth is only one polka dot among a million stars in the

cosmos.

Polka dots are a way to infinity. When we obliterate nature and our bodies with polka dots, we become part of the unity of our environment”

Kusama experimented with a huge variety of media to critique the patriarchy, war and other pressing social and political issues at the time. Her performance art did exactly this: she would stage nude female models, painted with her signature polka dot pattern, around New York, commentating on the commodification of the female body. She chose to return to Japan in 1973, a transition made difficult by the fact that her avant-garde style, so admired and celebrated in New York City, was met with huge resistance and even bringing ‘shame’ on her family

Having been admitted to the hospital multiple times for panic attacks and hallucinations, she voluntarily admitted herself to a psychiatric facility in Tokyo, where she still resides today, however, she did not, as many expected, retreat from the art world. Instead, she turned her room into an art studio to follow what she has stated is her “life's purpose”. By this point Kusama had been virtually forgotten both at home and abroad but she began to gradually re-establish herself from scratch, and eventually her work was re-evaluated A retrospective of her work was held at the Centre for International Contemporary Arts in New York in 1989, and four years later, the Japanese art historian, Akira Tatehata, managed to persuade the government that she should be the first solo artist to represent Japan at the 1993 Venice Biennale. The exhibition was a phenomenal success and led to a huge transformation in how she was received and recognised in Japan.

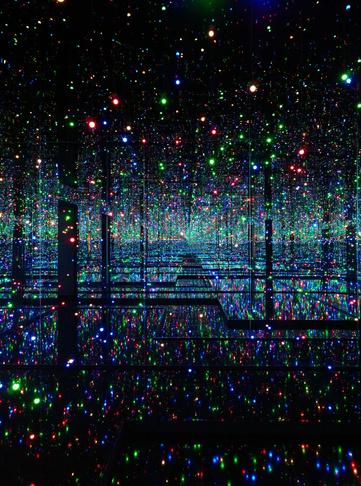

Her artistic output speaks of a mind that is truly creative although haunted, which makes for extremely captivating art One such example is her Infinity Mirror Rooms, which not only gained international acclaim but captivated audiences through endless illusion, dissolving the barrier between the art and the viewer. The extensive use of mirrors on all walls in these rooms creates an optical illusion of an infinite tunnel of light and any objects placed inside Over the course of her long career, she has created over twenty distinct Infinity Mirror Rooms They encourage viewers to lose themselves in the works, whilst becoming immersed in what must be close to Kusama's own visual reality.

This sees an overwhelming amount of luminous yellow pumpkins covered in strategically placed black dots. The result is a hypnotic, endless sea of pumpkins that have become Kusama's characteristic symbol The room represents themes of the sublime and obsessive repetition.

At well over 90, today, Kusama is still astonishingly prolific and one of the most recognisable artists of our time. Her work has proliferated well beyond the gallery sphere, seen most recently in a collaboration with Louis Vuitton, which produced a series of dotted clothes and accessories, demonstrating her immense impact and relevance.

This was an interactive exhibition in which the visiting public were invited to cover a previously white and clinical space in coloured circular stickers. After a few weeks, the space was completely coloured in blues, greens, pinks, oranges and yellows. The title has Obliteration in it, relating the complete destruction of every trace of something.

Kusama may be known today as the 'Queen of the Polka Dots' but her work is far more than a signature motif, it is an exploration of humanity and the mind, and an attempt to create beauty out of chaos. Her advocation for mental health awareness through her art as well as her position as a Japanese woman in a heavily male-dominated world has opened up doors in the art world for many leaving her with a powerful legacy.

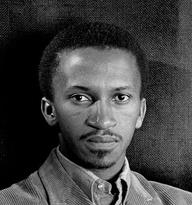

Zanele Muholi describes themself as a visual activist who has, from the early 2000s, documented and celebrated the lives of South Africa’s Black lesbian, gay, trans, queer and intersex communities. Raised by a single mother during the period of apartheid under an all white government from 1948-1994, they first turned to photography as a method of self healing. Muholi has investigated the severe disconnect that exists in post-apartheid South Africa between the equality promoted by its 1996 Constitution and the ongoing bigotry towards and violent acts targeting individuals within the LGBTQIA community through works of photography; some strikingly graphic, others imbued with a gentle glow

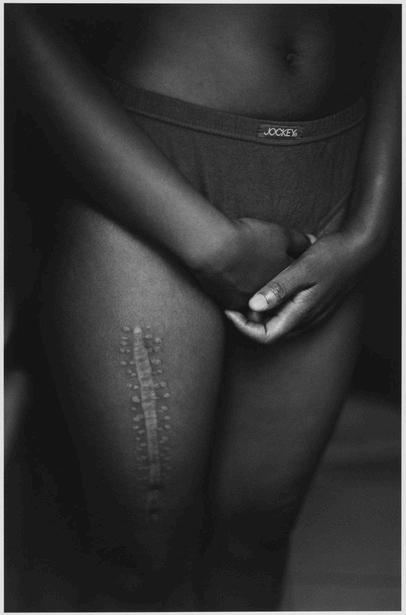

In the early series Only Half the Picture (2003-06), Muholi captures moments of love and intimacy as well as intense images alluding to traumatic events Aftermath (2004), for example, depicts the lower torso and legs of a person wearing briefs with a large scar visible on their right thigh. This series encapsulates natural moments of everyday life that have long been marginalised, asserting the participants as an accepted norm, hoping to offset the stigma and negativity attached to queer identity in African society Muholi’s hope is that the next generation can have access to their work, connecting with the experiences of people who have often been excluded, through an immediate and tangible visual image. Despite their political potency, Muholi’s portraits do not exploit their subjects for a progressivist agenda. They are deeply intimate, sensitive, and organic: close-ups of women kissing, dancing at weddings, bathing in colorful baths This kind of representation challenges the centuries-long project to commodify the black female body as the African ‘other’ and the object of a patriarchal colonial imagination.

Other key series of works, include Brave Beauties, which celebrates empowered non-binary people and trans women, many of whom have won Miss Gay Beauty pageants, and Being, a series of tender images of couples which challenge stereotypes and taboos. These images are intimate and soft, clearly demonstrating the sensitivity in which Muholi handles such subjects

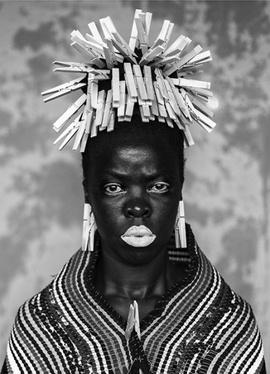

In Faces and Phases each participant looks directly at the camera, challenging the viewer to hold their defiant gaze. These images and the accompanying testimonies form a growing archive of a community of people who are risking their lives by living authentically in the face of oppression and discrimination. Some of these images depict people who have been subjected to the horrendous ordeal of “corrective rape”, evidence that they live in a country still notoriously homophobic, and violently opposed to any kind of gender nonconformity Not only are there a multitude of images but there are gaps too, signifying and reminding us of all those who have either passed on or have seemingly been forgotten by the system Muholi’s work perceives each person as a participant rather than merely a subject, thereby eradicating the hierarchy in which the photographer is granted power, instead prioritising forging relationships with each participant, charting their lives according to how they wish to be seen through the series Muholi’s pictorial archive offers visibility to the invisible, history to the erased, and celebration to the stigmatised

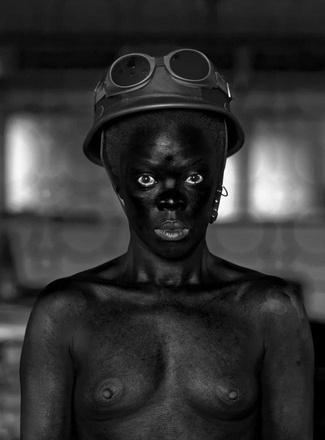

Muholi turns the camera on themself in the ongoing series Somnyama Ngonyama, translated as ‘Hail the Dark Lioness’, in which they experiment with different characters and archetypes that reference specific events in South Africa’s political history In the portrait Bester I, Mayotte, the sitter’s eyes stare directly at the camera, practically boring a hole in the lens. Their lips are painted white, their hair and ears adorned with clothespins and scouring pads, acting as a tribute to Muholi’s mother, Bester Muholi, and speak to domestic workers’ experiences of labour and servitude Unlike Faces and Phases, these images are also heavily edited to darken Muholi's skin in order to accentuate their striking blackness in all their regal strength and stoicism.

In Thulani II, Parktown, 2015, Muholi is dressed as a South African miner in a helmet and goggles, with the implication that they have just risen up from the darkest depths of the earth, bearing the coal dust of their labour. This commemorates the Marikana massacre in South Africa in 2012, which saw 112 men shot down, killing 34 as they walked out on strike at a platinum minefield in South Africa. In one image Muholi is portrayed as a black-and-white minstrel, a tribesperson with coils of sinister rope nooses for hair, or with fuse wire around their neck. Muholi has also appeared in necklaces of tyres, and wearing a wooden stool on their head in sardonic pastiche of western ideas of darkest Africa

The mordant title of one of their works, Nolwazi (translated as knowledge) is almost as disturbing as the image itself, where Muholi’s hair is filled with pencil. This refers to the dehumanising “pencil test” practice used by the South African government in racial classification under apartheid. If authorities weren’t sure whether someone was truly white, a pencil would be inserted in their hair. If it dropped out, the person “passed” as white

Muholi’s work is an art of agency, one which makes us question race, colonialism, oppression, gender and sexuality This is not merely just portraiture: it is activism

“Historically and in the present day, the body is the most politicised space, so it is crucial to my work. Many have exiled our female African bodies: by colonisers, by researchers, by men. ”

- Muholi

Today, Frida Kahlo is widely recognised as one of most important artists of the 20th century. But during her own lifetime, her own talents were often overshadowed by those of her famous husband, the painter Diego Riviera. In the early Thirties, Riviera and Kahlo were in Detroit, where he was working on a mural at the city’s Institute of Arts. When a reporter wrote an article about Kahlo’s own work, it was published in the Detroit News with the condescending headline “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art”. And although the surrealist artists Dorothea Tanning and Leonora Carrington are by now undoubtedly renowned painters, neither received the same widespread acclaim as their one-time romantic partner Max Ernst. However, these are but a few examples of the many creative women to have their work overlooked or eclipsed by a close male’s fame. Here is a collection of artists who deserve to be recognised for their own achievements – rather than viewed only as the lovers and muses of celebrated men.

Elaine de Kooning was a painter and Abstract Expressionist, and a particularly skilled portraitist. She became a well-known figure in the New York art scene – her work is vibrant and full of life. When she met Dutch abstract expressionist painter Willem de Kooning in 1938, Elaine Fried was 20 years old and studying art in New York City. He became her teacher, often destroying her work if he didn’t consider it good enough. Despite this, they married in 1943, and Elaine went on to build a successful career as an expressionist painter in her own right. However, she was aware that – in an artistic movement heavily dominated by men – her own reputation was dwarfed by her husband’s In 1951, she and Willem showed their paintings at an exhibition about artistic couples, which also included work by Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner and Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth. Elaine later regretted agreeing to the show. “It seemed like a good idea at the time, but later I came to think that it was a bit of a put-down of the women,” she said. “There was something about the show that sort of attached women-wives to the real artists.” As well as being a proficient artist – she had solo exhibitions all over the US and in Mexico, and in 1962 was commissioned to paint a portrait of then-President John F Kennedy – Elaine was also a prominent art critic and writer at a time when female art critics were extremely rare. Although not as famous as her husband for most of her life, her work began to receive more recognition in the years before she died in 1989. In the last few years, her paintings have appeared in several major exhibitions, including a retrospective of her portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC.

Jo Hopper was an artist of many talents, having worked as a teacher and actor alongside painting and selling sketches to newspapers. Born Josephine Nivison, Jo Hopper married the American realist artist Edward Hopper in 1924. Today, his keen-eyed depictions of life in 20th century America are still famous, but she has generally been forgotten. Yet, she was an accomplished artist herself, and had been a successful painter for 15 years before Edward made her his muse. Between 1923 and his death in 1967, she served as the model for every single one of his paintings featuring a woman. After Jo put Edward forward for an exhibition, his career rocketed into the stratosphere, and her work fell out of favour. Yet, like many wives of famous artists, she was integral to his success, managing his correspondence, maintaining records of his paintings, and liaising with gallerists to keep his career ticking over. She also provided him with artistic inspiration: many of his paintings feature motifs and colour palettes she had previously used in her own work.

As a child growing up in Switzerland, Sophie Taeuber showed an early enthusiasm for sewing and decided to study textile design. She met the Dadaist sculptor and painter Jean Arp in 1915 and the couple married in 1922. At around this time, Taeuber-Arp was teaching embroidery and textile arts and, in her own practice, producing geometric compositions in a variety of media that would eventually be counted as some of the very first Constructivist works. She had also become a regular at the Cabaret Voltaire, designing puppets and sets for Dada performances to which she would also contribute as a dancer. Other notable projects include the “Five O’Clock” tea room and foyer-bar at the Aubette in Strasbourg, an avant-garde leisure complex conceived by Theo van Doesburg in the 1920s that immersed visitors in its daringly abstracted interior designs. Taeuber-Arp fled Nazi occupation in Paris in 1940, eventually returning to Switzerland where she died in 1943 from accidental carbonmonoxide poisoning. She was a respected member of several modernist movements, including Dada, Constructivism, and Concrete Art, and her lively geometric compositions were important contributions to the early evolution of abstraction. Nonetheless her reputation has waned since her death in 1943. Her husband, meanwhile, is still remembered as one of the 20th century’s great artistic innovators, though he himself freely admitted in 1955 that “[Sophie] had a decisive influence on my work.” A recent attempt to correct this oversight has seen Taueber-Arp become the only woman to be featured on a Swiss bank note and she received a major retrospective at both Tate Modern and MoMA in 2021.

Studying at art school in London, Jean Cooke specialized in a wide variety of media including drawing, textile design, sculpture and pottery. Though she would eventually become best known as a painter, she originally set up a ceramics workshop in 1950. She met the painter John Bratby in 1953, and entered into an extremely volatile 20-year relationship that resulted in marriage and four children. After they separated in 1973, Cooke rented a cliffside cottage in East Sussex and, until her death in 2008, sought solace in its dramatic coastal views. Despite the difficulty of finding time to work within the confines of her marriage, Cooke’s many transfixing, wide-eyed self-portraits are a record of her perseverance. “I started painting myself the way I wanted to be seen,” she once said. After her first solo exhibition in 1964, she soon gained a following of loyal collectors. In fits of jealousy over her commercial success, Bratby would often destroy Cooke’s works by painting over or slashing them. He may be recognized as a founder of “kitchen sink realism” a British cultural movement that extended to films, plays, and novels, and favoured gritty portrayals of everyday life for work-class Britons but it is Cooke’s vulnerable expositions of domestic life, with all its harsher realities, that has left a lasting impression.

Lee Krasner was an American abstract expressionist, whose particular specialisms were painting and collage, but she also produced portraits and Cubist drawings amongst her 50 years’ work. During the Great Depression, Krasner worked as a muralist for the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a public art project, and was an arts activist. In the 1930s, Krasner was at the centre of the New York art world, having joined the American Abstract Artists group. She later married Jackson Pollock, and following his demise, Krasner was one of the key players in establishing his legacy. She even included fragments of discarded paintings by Pollock in works such as ‘Bald Eagle’, spattering them with paint. Posthumously, Krasner has received more recognition, and her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art sadly opened just a few months after her death.

Elizabeth Siddal is remembered first and foremost as the muse and lover of Pre-Raphaelite painter Gabriel Dante Rossetti, a pre-eminent artist of the Victorian era who remains a household name in the U.K. As the model for paintings like John Everett Millais’s Ophelia, Siddal’s delicately refined features and cascading, copper-coloured hair came to define the aesthetics of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, although Gabriel forbade her from modelling for the others. As the movement’s name suggests, however, it was male-dominated, and Siddal’s own creative output as a poet and artist was sidelined. Initially taught to draw by Rossetti, with whom she had an on-and-off romantic relationship, Siddal adopted a similar style and thematic interest in Medieval literary sources. These works quickly attracted the attention of the illustrious art critic John Ruskin, who believed she was a “genius” and paid an annual salary of £150 to support her practice. Siddal was the only woman to contribute to the Brotherhood’s summer exhibition of 1857 and one of her best known paintings, Clerk Saunders, sold to the American collector Charles Eliot Norton. Despite suffering ill health, Siddal left London and the overbearing influence of both Rossetti and Ruskin to enrol at the Sheffield School of Art. Her studies were unfortunately interrupted by serious illness and she eventually reunited with Rossetti, marrying him in 1860. Just two years later, she died at the age of 32.

Born in Havana, Ana Mendieta was exiled from Cuba with her older sister at just 12 years old, and was sent to an Iowan orphanage. Her work explores her identity as a female emigrant. Amongst Mendieta’s bestknown pieces are her ‘earth-body’ performances, and her oeuvre also includes sculpture, film and photography. Mendieta used the earth as a platform to confront the difficulties of displacement, recording her body’s imprint in video and photo in several outdoor locations. She was inspired by what she referred to as ‘primitive art’, and her work is expressive and visceral as a result. Mendieta tragically died at 36 after falling from her apartment window in New York, after being pushed by her husband Carl Andre, who was acquitted for her murder after being defended by the New York art world, and continued his highly successful career as a minimalist sculptor, outshining Mendieta’s career.

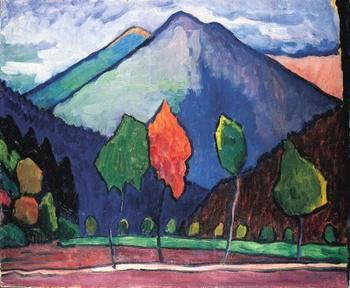

Gabriele Münter was an Expressionist painter from Germany best known for her stylised landscapes, domestic interiors, and self-portraits. After enrolling at the short-lived Phalanx School in Munich, she studied under renowned Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, the two later became a cohabiting couple for over a decade. Both artists influenced each other in the production of even more abstracted and vibrantly colourful paintings and were leading lights of Der Blaue Reiter (the Blue Riders), a group of artists at the very forefront of German Expressionism. After their relationship came to an end, Münter fell to the margins of their artistic circle and, embittered by the experience, refused to return some 1,000 of Kandinsky’s works in her possession. Forging her own path, she continued producing painterly landscapes, portraits, domestic interiors, and folk art, always with a knack for capturing her subject’s essence. While he is celebrated as an avant-garde pioneer, she is perhaps best known as one of his devoted followers despite the fact that her inventive painterly sensibility may have inspired Kandinsky. “In the eyes of many, I was only an unnecessary side-dish to Kandinsky,” she once recalled. “It is all too easily forgotten that a woman can be a creative artist with a real, original talent of her own.”

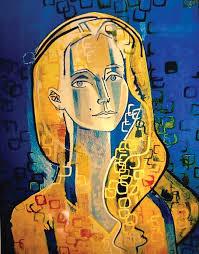

Françoise Gilot was an accomplished painter whose art was eclipsed by her long and stormy romantic relationship with a much older Pablo Picasso, and who alone among his many mistresses walked out on him. But unlike his two wives and other mistresses, Gilot rebuilt her life after she ended the relationship, in 1953, almost a decade after it had begun despite an age difference of 40 years. She continued painting, adopting a colourful abstract style associated with the postwar School of Paris rather than imitating Picasso. Even towards the end of her life, Picasso, though long gone from her life and by then long dead (died 1973), nevertheless remained an imposing and, as a giant of 20th-century art, overshadowing presence.

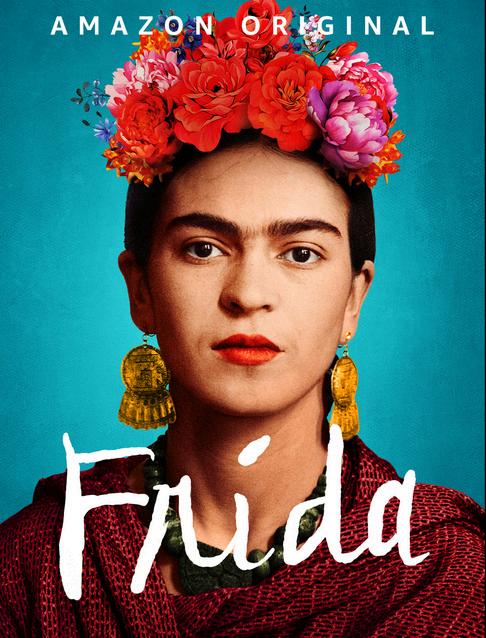

A documentary exploring the life and work of Frida Kahlo like never before. Told through her own words drawn from her diary, revealing letters, essays and print interviews, we finally are given an intimate and raw insight into the true character of this iconic artist. Her works are brought vividly to life through lyrical animations, making her already all consuming works somehow more immersive and moving.

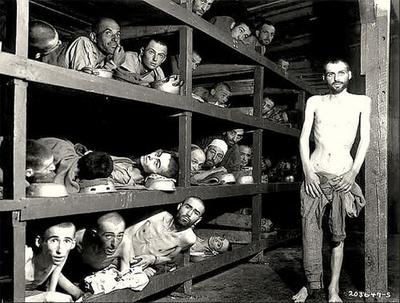

A recent film produced by and featuring Kate Winslet, which tells the story of American photographer and photojournalist, Lee Miller, whose legacy consists of 60,000 images, which were accidentally discovered by her son after her death in 197 7. Beginning her career as a fashion model in New York City in the 1920s before going to Paris to become a fashion and fine-art photographer, her harrowing and crucial war photography is often overshadowed and undermined by this. She became a war correspondent for Vogue in 1943 and took some of the first photographic evidence of the Holocaust, exposing to the public the horrifying atrocities committed by the Nazis in the concentration camps. The film primarily focuses on her revolutionary work in this time period, as the first woman to follow the US army’s advance onto the front lines.

Ware’s novel is an essential work that elevates a globally dismissed legacy to its proper place in the mainstream art canon. It covers the hundreds of years of Black faces cast as only the subject of the white gaze, before delving into the work of revolutionary black artists, including a small group of trailblazing Black American painters and sculptors who reached national and international fame, setting the stage for the flourishing of Black art in the 1920s and beyond.