Neutral Magazine allows students to voice their creative thoughts, insights and ideas, covering a multitude of topics and styles.

Neutral’s contributor base is largely made up of film and media students who are keen to share their passion and dedication to the media, film, arts and industry.

Neutral examines the advantages and consequences of living in a technological world and begins to explore what our world may look like in the future.

100% of Film and Media students thought that staff made the subject interesting.

(National Student Survey 2022)

Immerse yourself in the world of film and explore it’s evolving relationship with wider media and culture.

Learn to analyse and discuss films from different genres, periods and cultures. We embrace the changing landscape of film. You will explore cinema’s evolution and it’s interaction with visual art, literature, digital media and more.

Discover how media and culture affects who we are, what we do, and how we interpret the world around us. BA (Hons) Media and Communication

Find out how media influences society and culture. This varied degree allows you to be creative as well as analytical. Explore the varied world of media, taking in film, television, digital media, advertising and more.

MA Film and Screen Studies

Explore the relationships between different types of screen media and how they impact the world today.

You will gain an understanding of the history, nature and power of film and screen media. Discover the ways film can influence ideas and identities. Engage with film and other media by writing for our Neutral magazine and exploring digital media and communicative methods. During your studies you will develop your abilities in relevant applications within the Adobe Creative Suite, focusing on transferable and sought after skills.

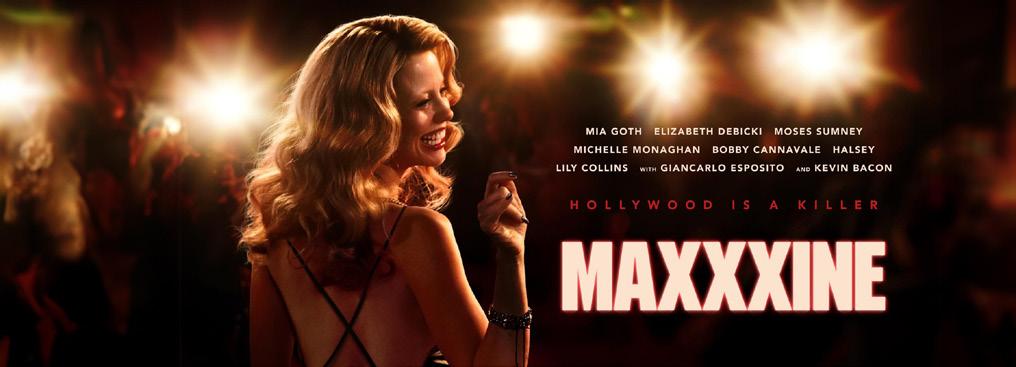

Ti West’s MaXXXine (2024) follows Mia Goth’s character, Maxine Minx, as she aspires to become a Hollywood actress after her prior experience in the adult film industry.

Throughout the film, we learn that a serial killer is targeting young women in Los Angeles, the majority of which are connected to Maxine - it becomes evident that she’s being stalked. MaXXXine is the third instalment in West’s horror trilogy. All three films explore characters played by Mia Goth; Pearl (2022) provides a character study in the form of a prequel to the first film in the trilogy, X (2022), as well as being a display of Goth’s unmatchable acting prowess. Throughout this trilogy, West explores themes surrounding violence and pornography, as well as paying homage to a range of film genres. For example, X is a classic-style slasher, akin to that of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1976), and Pearl borrows tropes from other genres, such as the drama, thriller, and even the musical. Much of its miseen-scene (the overall look and feel of a film) is inspired by The Wizard of Oz (1939). Due

By Amber Bissell

to the success of the first two films, MaXXXine has been highly anticipated; it made the most capital on opening weekend out of all three films of the trilogy. Despite the apparent excitement for MaXXXine, at the time of writing it’s the lowest rated out of the three on sites such as IMDb and Letterboxd.

However, the film does have some good points, such as Goth’s incredible performance. Just like in X and Pearl, Goth is able to prove herself as one of the greatest actresses in horror at the moment. From her facial expressions down to her line delivery, Goth is able to convincingly sell whichever character she is playing to the audience. Furthermore, Kevin Bacon and Giancarlo Esposito’s characters and performances were a welcome surprise, actually providing some unexpected comic relief. The film follows on from the events of X, after Maxine escapes the farm. MaXXXine doesn’t neglect the fact that she would be affected by prior events. For example, in one particular scene, she experiences flashbacks to the horror and violence that Pearl and Howard subjected her and her friends to in X, and is clearly haunted by it. Despite this, MaXXXine stands as its own film and doesn’t depend heavily on the first two instalments

to tell its story. This is a positive for casual moviegoers, however, it left a lot to the imagination of fans of the prior films. Aside from the few moments mentioned in which Maxine is haunted by Pearl’s actions in X, it doesn’t refer to the story of the other films, or fully wrap the trilogy up in a satisfying way.

Furthermore, the film doesn’t seem to be able to decide how it wants Maxine to come across. There are short moments in the film that portray her as unhinged and when it does so, Goth provides a stellar performance. However, it also conveys her as some sort of damsel in distress, especially within the final act. These two aspects of Maxine’s character seem to be at odds with each other and are unable to create a cohesive study of her character, perhaps damaging the flow of the film/trilogy. Additionally, her character development is hindered by the storyline; it seems to make an attempt at being a character study at the same time as being a crime/mystery/horror film, all of which are unable to be fully explored due to the relatively short length of the film. Consequentially, the quality of storytelling and Maxine’s character cohesion suffers because of this.

The setting of MaXXXine is unmistakeably eighties-themed, demonstrated by the hairstyles, clothing, and even through the use of lighting. West draws inspiration from real-life events and infamous serial killers, most obviously Richard Ramirez, nicknamed the Night Stalker. Ramirez killed thirteen people between the years of 1984 and 1985 in and around California - satanic symbols were often observed at the scenes of his crimes. MaXXXine draws on this for its stalker-serial killer storyline, however, it doesn’t expand upon it. The identity of the killer is unknown for the majority of the film (until the final act), and most of the killings occur offscreen, which feels like a missed opportunity considering the calibre of the murders that were presented in both X and Pearl

In addition, the final glaring issue presented by MaXXXine is the majority of the third act. After a sequence of unnecessary flashbacks that seem to spoon-feed the audience, Maxine realises that the killer and her stalker is her father, a televangelist who along with the help of members of his ministry, claims to have been creating a snuff film to expose the evil within Hollywood. He ties Maxine to

a tree in an attempt to exorcise the evils he believes Hollywood has bestowed upon her. West is clearly attempting a nod towards the satanic-panic present in the 1980s with the religious and cult theming, however, the payoff feels unearned, the killer cartoonish and the motive forced.

Due to the current expansion of social media platforms, proliferation adds to issues surrounding safety, influence, and legitimacy.

Richard and Couchot-Schinex wrote about how perhaps in our postmodern world, and even during fourth-wave feminism, cyberspace has allowed for the growth of cyberbullying and the spread of pejorative attitudes concerning a person’s gender or sexuality. In 2020 they wrote that some people, who wish to galvanise hate and division with regard to gender, ‘disproportionately target youth who are seen as the most removed from idealised forms of masculinity or femininity’.

One of the most well-known influencers who has caught the attention of youths regarding gender and sexuality within the last few years is Andrew Tate. Tate, an ex-kickboxer, has created divisive content since around 2009. He has since gained notoriety as a hatemongering and lawbreaking figure who has, nonetheless, retained a dedicated fanbase. Tate proclaims to be the leader of the ‘Alpha Male Movement’

By Holly Barker

and its toxic ideology. This movement has caught the attention of many social media users and not all for good reasons. Tate has released podcast videos on platforms such as TikTok, which is heavily popular amongst Gen Z. His toxicity can be commonly seen in the videos he posts on social media, where he makes statements such as “Women are f***ing backwards”. These abusive videos have been estimated to have garnered almost 1.5 billion views on TikTok.

Tate has the ability to use micro-media formats to spread macro-abuse. His Twitter posts are usually between 5-20 words, making it easier for audiences to understand the message quickly and share it. The way in which his TikTok videos are made also could have an impact; the message he is trying to convey is usually spoken within the first 10 seconds of his one-minute videos. Again, this makes it easier for the audience to understand his message and be interested and tempted to watch more, even if his video catches attention for objectionable reasons. His controversial comments that are still live on Twitter include, “Men go through so much pain that they will never talk about it because they know that nobody cares” (2022). The noun ‘men’ is the

first word in his post, linking to how he uses gender and sexuality as a way of catching the attention of an audience. This statement has over three hundred thousand likes. This message could have been seen by anybody of any age or gender, and could have detrimental impacts. The mental health crisis has become an epidemic in society, and for men to believe that nobody cares about their feelings could impact societal ideologies and make them believe they shouldn’t speak out. Although Tate has been a successful businessman over the last few years, he doesn’t have evidence or proof that his statements are true. He is potentially spreading harmful messages surrounding gender and sexuality to large audiences, and in doing so presents himself under the guise of a successful entrepreneur and leader. What is of the utmost concern is the fact that people can reshare tweets and videos on Twitter, which allows these messages to be spread across the globe at a remarkable pace, monopolising social media’s position of Freedom. X (formerly Twitter) states that their policy is dedicated to ‘defending and respecting the user’s voice […] This value is a two-part commitment to freedom of expression’.

What is also concerning is the statistic of users who have watched Tate’s reshared TikTok content. Maya Oppenheim stated in The Independent in 2023 that ‘Polling finds eight in 10 teenage boys have watched Tate’s content.’ One of his statements was “Imagine being a normal dude who likes football and now you’re forced to be a massive advocate for homosexuality” (2022). Firstly, the adjective ‘normal’ to describe a man who isn’t within the LGBTQ+ community or a man who likes football is very concerning. For a boy, teenager, or man to believe this scaremongering could be damaging and of course further marginalises those coming to terms with their own sexuality in what one would hope to believe is a more tolerant society.

In Henry Jenkins, Joshua Green, and Sam Ford’s book Spreadable Media (2013), digital content and ‘spreadable media’ is discussed. They state, ‘Successful creators understand the strategic and technical aspects they need to master in order to create content more likely to spread […and] build relationships with the communities shaping its circulation’ (p.196). What is so vital about this quotation is that Tate may in fact know how to use social

media to his advantage and then how to form communities, ironically giving some a sense of belonging that is bonded by division and hatred.

At the time of writing, Tate is currently being retained in Romania after he and his brother Tristan were charged in June 2023 with rape

and human trafficking. His views and flagrant toxicity may not have broken some rules of social media platforms, but his alleged actions have resulted in material consequences. However, influencers by their nature have influence, and the damage that he has caused to many remains to be seen in full.

The ‘Miracle of the Andes’ has fascinated filmmakers and audiences alike since the harrowing true story of human survival became publicly known in 1972.

The story of a plane crash where the survivors resorted to eating their deceased friends for survival has previously been translated to dramatic retellings in film. Frank Marshall’s Alive (1993) and ‘Mexploitation’ film Supervivientes de los Andes! (1976) had earlier attempted to demonstrate the ensuing seventytwo days of gruelling survival. However, it’s Spanish director J.A. Bayona’s La Sociedad de La Nieve, or Society of the Snow (2023), that arguably portrays the ordeal in its most poetic form thus far. By not solely focusing on the horror of the group’s survival, but also the ‘society’ that formed around the goal to escape their situation, Bayona’s narrative takes deep care for the memory of the deceased. The intense cinematography, the mise-en-scene, and the powerful dialogue and performances all coexist in such a way that feels incredibly authentic and respectful towards the victims and survivors alike.

“Who Were We On The Mountain?” J.A. Bayona’s Society of the Snow (La Sociedad de La Nieve.) (2023)

By Ren Anthony

A ten-year-long effort to finance and create the film highlights how crucial it was to Bayona for the dialogue to be in Spanish (specifically Uruguayan), to uphold the authenticity of the story. This allowed the story to be told in the language spoken by the community that was shaped by the disaster. On a global scale, Spanish-spoken media is often overshadowed by English-language productions, which generally have more accessibility to financial backing. Therefore, finding funding to create a more authentic portrayal proved incredibly difficult. Nonetheless, the language of the production is attributed as a large part of the film’s importance, with all of the cast being fairly unknown actors from Uruguay and Argentina. The near-global anonymity of those portraying both the victims and survivors was intended to present the viewer with the opportunity to reflect solely upon the trauma faced by these ordinary, mostly young victims from a more historically faithful position. The intent by the creators to focus on the group as a whole carries in itself the reckoning with mortality, emphasising the power of humanity and grief at odds with nature. These themes can be examined across Bayona’s filmography, most notably in The Impossible (2012) and A Monster Calls (2017), and seemingly harbour a deep narrative fascination.

The experience of watching the film is an incredibly visceral one; the plane crash and avalanche sequences contain graphic body horror, and the idea of cannibalism is included in much of the dialogue - although Bayona was careful to not show much as to not overlysensationalise the experience. Whilst these themes are upsetting, La Sociedad de la Nieve does not cross the line into commoditising them for the sake of entertainment. The film demonstrates that the deaths of some made the survival of others possible, as their bodies were consumed for sustenance and saved them from starvation. In the same way, it was clarified that the main intention of the film was for the survivors themselves to give something back to those who perished on the mountainto thank them. Not only does the most recent interpretation of this disaster recognise the survivors, but also shows the audience the help that those who lost their lives gave to those who were ultimately rescued.

The text explores themes of humanity and endurance through suffering with its realism and close camera angles, capturing the claustrophobia of the fuselage the victims were confined to for warmth and shelter. The philosophical relationship between the living and the dead is what touches the spiritual layer that is intrinsic to this retelling’s poeticism.

By featuring a voiceover narration from Numa Turcatti, the last victim of the crash to die in the fuselage, the film bridges the metaphysical gap between life and death, and heightens the cohesive idea of ‘society’ across those abandoned in the mountains. The collective power of this group of mostly young men is a theme that is deeply examined in the narrative; every single member was fundamental to the strength of the others. Part of Numa’s intention as the narrator is to elicit an emotional response from the viewer at the unexpectedness of his death. This subverts the hero’s journey narrative arc that disaster films often follow; the ‘hero’ character is expected to survive. This abruptness emphasises the tragedy of how close each of them was to surviving, but how he was no less of a hero for not making it. In the narrative and in the true accounts of the actual survivors, it was Numa’s death that acted as the inciting incident for survivors Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa to begin their arduous mission to find help beyond the mountain. The entirety of Canessa and Parrado’s journey is without the previous narration. There is limited dialogue between the pair, and Michael Giacchino’s tense score underlies their scenes. This illuminates their isolation

from the rest of the world, but also expresses how close they are to surviving the ordeal with each step.

The film could have ended on the triumphant note of a rescue helicopter arriving, as previous iterations have. However, Society of the Snow opts for a more sobering tone to end on. The closing shot of the film features the surviving sixteen all huddled in the same hospital room, echoing their dynamic in the fuselage. The parallels between the fuselage and the world which they return to emphasises the loss of those who didn’t survive, and the group trauma that stayed with them. Accompanying the shot is a final voiceover from Numa, addressing the survivors, telling them to “keep taking care of each other, and tell everyone what we did on the mountain”. This final line echoes the intentions of Bayona when he set out to create the text a decade prior; he wanted the survivors to be able to give something back to those who died, by telling the world what happened in the Andes in 1972.

Riz Ahmed is an incredibly strong example of a transnational artist who uses his work to demonstrate how different people face discrimination based on where their heritage lies.

His postcolonial trilogy consists of the film Mogul Mowgli (2020), the short film The Long Goodbye (2020), and the album also titled The Long Goodbye (2020). Their engagement with historical-political contexts demonstrate the lasting effects of colonialism on many people across the world. This trilogy highlights how the British colonial rule over South Asia has led to many people today feeling like they lack identity.

Throughout all three modes of the trilogy, the characters feel a strong sense of unbelonging due to border crossing by past generations. Zed avoids his parents in Mogul Mowgli because he doesn’t want to confront his culture. His parents, aunties, and uncles speak Pakistani, whereas he and his cousins speak English. Zed embodies two nationalities but is

unsure of his true identity, frequently dismissing his Pakistani heritage. In one scene, he tapes a rap song, an American genre, over a Pakistani cassette, physically erasing his culture. Despite his persistent efforts to do this, Zed is confronted by a Pakistani figure, Toba Tek Singh, who appears whenever he is the most dismissive about his culture.

Ahmed’s monologue, Where You From, features in every part of this trilogy, where he suggests, “Maybe I’m from everywhere but nowhere”. People whose heritage lies outside the borders they currently live within often feel like they don’t belong anywhere. Parts of their being can originate from multiple places, but their colonial past has interfered with their ability to know exactly what this heritage is. Overlooking this colonial past would be inappropriate and disrespectful. Ahmed pleads, “Stop trying to make a box for us”, showing us that by crossing borders, his identity becomes much more indistinct. Zed struggles to label himself, but learns to embrace his culture out of respect for those who faced many troubles before him.

Ahmed frequently calls himself Mowgli in this trilogy, which you might recognise from

The Jungle Book (1967). Mowgli’s home is ambiguous; his human appearance implies that he belongs in the village. However, he mostly lives with the animals in the jungle, who he looks nothing like. In Where You From, Ahmed states, “If you want me back to where I’m from, then bruv, I need a map”, showing that people tell him to go ‘back’ to Pakistan because of his appearance, despite being born England. If he did go to Pakistan, he would feel as lost and unknowing as the White tourists. These characters face racism because people believe they don’t belong in a ‘White’ country; in The Long Goodbye, the White supremacists kill and kidnap Riz’s family purely for existing in England.

Another interesting aspect of these films is the imagery from the backs of cars. Mogul Mowgli features home videos from Ahmed’s childhood, filming key London tourist sites from the back of a car. In The Long Goodbye, the women are forced into the back of the supremacists’ van. This imagery emulates a taxi service, implying that these characters are viewed as tourists who disrupt the British way of life. This imagery is also seen in other postcolonial films like Dirty Pretty Things (2002), where Okwe, a Nigerian immigrant, becomes a taxi driver in London.

The taxi service indicates that non-White people are on holiday and will leave soon, but these characters have no choice. People expect Ahmed to return to Pakistan because he isn’t white, but they fail to recognise that England has always been his home.

Ahmed’s use of home videos and close-up shots in the back of the cars also give these films a slight documentary-feel. Certain closeup shots resemble scenes in the documentary Miss Americana (2020), where Taylor Swift sits in the back of a car talking about some of the struggles she has faced as a female celebrity. Similarly, Zed uses his car journey to consider his identity. This documentary-type imagery shines a light on the reality of postcolonial cinema - these stories are based on the real experiences of real people.

Another major aspect of this trilogy is music. In Mogul Mowgli, Zed writes Toba Tek Singh, which is a city developed by British colonisers in the 19th century. When the Long Partition occurred in 1947 and Britain lost control of South Asia, nobody knew whether this city was located in Pakistan or India. A short story of the same name was published in 1955, where the characters can’t self-identify

because they don’t know which country Toba Tek Singh is in. In Ahmed’s song, he sings “Left me in no-man’s land […] she wanna kick me out”, mirroring the way that Pakistani people’s land was selfishly taken from them. When the British Empire dissolved, South Asians were left without a true identity. The line “I love a cup of tea and that […] it’s from where my DNA is at” demonstrates how many people choose to forget about the colonisation of South Asia, but postcolonial cinema refuses to let this happen. Tea is known as a muchloved British drink, but as it comes from Asia, it seems that many people ignore this colonial past. Ahmed shows that this past colonisation still affects people today, particularly through racism and Islamophobia. Through the intertextuality of Toba Tek Singh, the short story, Zed’s characterisation, and South Asia’s colonial past, Ahmed highlights the importance of not choosing to deny the past.

Often, it is hard for people from disadvantaged backgrounds to share their stories, but Ahmed has found the perfect way to share his experiences as a PakistaniBritish individual - through cinema and music. Although these specific narratives have been partly made for entertainment, Ahmed has

made sure to capture true authenticity, like through the use of his real name and music. He shows a strong refusal to forget South Asia’s colonial history and demonstrates how these past events still affect people like him today. Whether you’re more interested in film or music, Riz Ahmed is the perfect artist to start with to learn more about a community that is often neglected in the media.

As long as there is a media cycle, the people will have satire.

The possibilities for satirical media seem endless; cult classics like Life of Brian (dir. Terry Jones, 1979) and Hot Fuzz (2007), cringeworthy coming-of-age tales such as The Inbetweeners, countless mockumentaries like The Office (both the US and UK versions). Even the news comes to us satirised for print and screen (Private Eye and Mock the Week, respectively). It is by no means a modern invention. Satire ‘always was’ and ‘always will be’ integral to the fabric of British society. But we can’t deny that satire must have come from somewhere. Through that question of where, we are then further led to the bigger question of why? Why is satire so prevalent? What makes satire, out of all of the comedic traditions, the genre that has undeniably stood the test of time?

Like many things, we can thank the Romans for satire. In the beginning, satire was relatively formless, that was until the genre was first refined by Gaius Lucilius. His work was responsible for cultivating the critical

By Fyn Taylor

commentary that was set to become the centre of satirical work, also establishing the poetic form that many satirists still follow to this day. Lucilius’ collected works also served as the foundation for, most likely, two of the most important satirists in the history of the formHorace and Juvenal.

Of the pair, Juvenal came first. His style was earmarked by ironic criticism, scathing and full of bitterness. His poems attacked life in Rome under Emperor Domitian, particularly the corruption of society and the failings of mankind. Juvenal acknowledged that criticise powerful people was dangerous, often stating that it was the reason he chose to only criticising the dead - unsurprisingly this was not actually the case. His works criticised many of his contemporaries, but his declaration of only writing about the dead emphasised his opinion that Rome had always been corrupt.

The Juvenalian satire style fits comfortably within the landscape of English literature, especially in the hands of Johnathan Swift. Swift recognised the way in which satire could be used as a tool for protest in a time when censorship was rife. Notably, his poem A Satirical Elegy, written upon the death of a

war profiteer, provided a voice for the angry masses. It showed the disinterest that the public felt upon his death, reminding those that he was no God, but simply a man. The voices in the poem show little sympathy for the figure, and the sympathy that is shown is sarcastic - why should the public mourn a man who is responsible for the deaths of so many?

The influences of Juvenal and Swift are even seen today in the publication of the Private Eye magazine. Like the two satirists that came before, the publication aims to criticise those in power. It removed the status of notable figures by making them the subject of comedic scrutiny, or rather by mocking them. While censorship today may not be as aggressive as it was in Ancient Rome or 1700s England, satire is still relevant as a means of expressing public sentiment, especially when the public is angry.

Horace followed Juvenal, offering a form of satire that was more focused on comedy than the brutal takedown of those in power. Horace was a firm believer that, above all, satire was comedy. Horace appreciated that Lucilius’ main point was self-revelation. Horatian satire is more self-aware. Historically, a good example of this is The Importance of Being Earnest – a

play criticising the upper class, written by a member of the upper class so that upperclass audiences could laugh at themselves while the working class could laugh at their peculiarities. Horatian satire often puts weight on recognising the trivial nature of life, to laugh at the flaws of humans instead of criticising them. While it doesn’t paint the most flattering picture of politics, the series The Thick of It has a relatability that anybody who has worked in an office environment can enjoy. For those in corporate jobs, the show is a representation of the absurdity of office politics, it is quite literally a show about the absurdity of politics.

Monty Python, too, has taken its shot at encouraging the public to laugh at politicians and politics in the flying circus episode, Party Political Broadcast. While the episode as a whole calls into question the unsavoury use of classicism and other underhanded methods used by political parties to get into power, there is a sketch that chooses to focus away from the content and instead on the delivery. It has been long understood in this country that politicians are rigorously media-trained, and

the Python troupe chose to focus on this by making their fictional politicians do ridiculous dances choreographed to their speeches. One thing is for certain: the idea of dancing politicians is absurd, but the message of the sketch is clear - to partake in politics is to perform, but by choosing to make comedy from their performance, the Pythons are in their own way removing the status of those in power.

With that I am brought back to my question: why is satire important? In my eyes, satire holds those in power accountable. It is a method for the masses to express their displeasure, but is also a method to take people from being in power to being peers. Satire serves as one big inside joke that transcends status and hierarchy. Satire is a tool for protest, but is also a tool for unification. In this digital age, we are seeing more people creating satirical media to express their frustrations with those in power because above all else, satire is comedy, satire is entertainment, and satire is showing no signs of going away because it is accessible. Satire, the people’s comedy, is important because in

even the most heavily censored of societies, it is one of the few forms that is able to challenge the status quo and call into question the state of society and man alike.

When faced with the ideology of a monster, typically horror films depict one of two contrasting narratives to the audience.

The monster either devolves from a less-thanfortunate origin, which elicits the audience to understand their contentious actions, or the monster is inherently malicious and possesses the desire to terrorise its victims. Bride of Frankenstein (1935) is the sequel to Frankenstein (1931), and is one of the first iterations of the sympathetic monster in horror. Whale asserts a depth into his characters that transcends their bad actions, recognising humanity in those that would otherwise be labelled as a villain or a monster. The intrigue of The Monster is centred around his human-like nature, but also the uncanny disparity which causes him to be shunned from society and yet elicits sympathy from the audience.

Since The Monster’s conception in the preceding film, he has become aware of his origin as an experiment. This accumulates sympathy because The Monster is made up

By Hannah Roberts

of body parts from graves and the gallows, including the brain of a criminal. This combination of fragments of those who have already met death causes great wonder in The Monster’s creator, Henry Frankenstein, who wishes to make a scientific breakthrough. However, his ambition likens him to The Monster because he becomes consumed in his experiment to the extent that he doesn’t prepare for the future in which his creation becomes an entity of uncontrollable chaos. Therefore, Henry Frankenstein could also be perceived as monstrous for the lack of responsibility he takes regarding the murders The Monster commits. Although, he is likely exempt from being ridiculed as a monster due to his regret that he created this creature, and his ample attempts to dispose of him. This seems to make him blameless in the eyes of the townspeople, despite being the source of their anguish. Moreover, he is sympathised with by the audience, as he didn’t produce his experiment for a vindictive reason.

A significant contribution to The Monster’s uncontrollable behaviour is the lack of preparation Frankenstein made for his existence, signified by the fact that he was never named and only ever referred

to as ‘Monster’. Beyond this, his outward appearance (that The Monster had no capacity to control or change) separates him from societal norms. Therefore, he is antagonised by the townspeople, conditioning him to confront terror and violence by being aggressive himself; he was never taught another way to exist.

Boris Karloff’s performance should be acknowledged as one of the most important factors in generating sympathy for The Monster. He clearly expresses the struggle between the clashing pieces of humanity he possesses, which onlookers perceive as unusual. Karloff also emphasises how The Monster tries to replicate human actions and expressions, but falls too heavily into the uncanny despite his physical humanity - we are forced to sympathise with his futile efforts.

Whale highlights the obstructive effect The Monster’s appearance has on his ability to form human connections in Bride of Frankenstein when he encounters a blind man residing alone in the woods. He is drawn by the sound of a violin, showing his inherent ability to appreciate art. Though he is hesitant at first, The Monster distinctly realises that his appearance is

causing his difficulties with others. Whale uses the motif of reflections to convey The Monster’s own disgust when he observes himself in a body of water, allowing him to feel the repulsion he has been conditioned to feel by spectators. Whale utilises the character of the blind man to accentuate that The Monster’s inherent behaviour isn’t the reason he lacks connection; his ‘monstrous’ appearance forces people to react corresponding with their preconceived opinions of him. This barrier is eradicated by the blind man, who doesn’t judge his inability to talk or express himself. In fact, he is able to learn some words and communicate more easily after this encounter, as well as trying alcohol and cigars - things that make him appear human to the audience. Whale elicits our sympathy further when the townsfolk disrupt the meeting between The Monster and the blind man, causing the house to go up in flames. The fire antagonises The Monster and acts as a continuous trigger for him to retaliate and protect himself.

It can be inferred that The Monster’s victimhood stems from the repetitive attacks he preserves himself from that resemble contemporary accounts of lynching. This

implies that Whale may have employed The Monster’s constant attacks as a microcosm for racism and prejudice, in that he appears as the ‘other’, who instils fear in those who fit into society. Therefore, he is ostracised and pursued by mobs similar to those who would lynch minorities.

It’s ironic that the titular character of The Bride in Bride of Frankenstein only appears in the final act of the film, as though she is a final resort to change The Monster’s fate and give him a connection. The Monster’s desperation for Henry Frankenstein to create him an equal accentuates his final wish to be understood by a creation akin to him. However, The Bride appears instantly terrified by her existence and the unfamiliarity of being reborn, which in turn causes her to be unsettled by The Monster himself - she declares that she hates him like the rest. It appears that The Bride instantly recognises herself as grotesque and can’t even attempt to live with her monstrosity in the same way The Monster does. This sequence of events encourages the audience to sympathise with The Monster, who can’t even be accepted by a creation that is indistinguishable from him.

It’s clear that Whale wanted to emphasise the tragedy that Frankenstein’s narrative has always portrayed. The Monster is easily able to capture the compassion of the audience because he replicates a child seeing the world for the first time before his untimely abandonment – it’s wonder but mainly it’s terror. Such a message resonates with anyone who is or has felt marginalised in society. The film generates the ultimate sympathy for The Monster because it doesn’t provide a positive resolution for his qualms, due to him not being accepted throughout each attempt he makes at forming a relationship.

By Isobel Williams

Noah Baumbach’s work as a writer and director often explores the impact of strained relationships on his characters - often tortured artists.

These thematic concerns, his penchant for Naturalism, and consistent collaborations create an intriguing auteur who specialises in the dynamics of relationships.

The history of auteurism resonates with Baumbach’s work. His filmography highlights the importance of art and philosophy through his characters; he almost always includes a character that is an artist of some kind. The thematic concerns of Baumbach’s work reflect a desire to portray more realistic depictions of the difficult aspects of life. Marriage Story (2019) details the impact divorce proceedings have on families, The Meyerowitz Stories (2017) reunites three estranged siblings due to their father’s declining health, and Frances Ha (2012) follows the uncertain life of a woman struggling to maintain friendship and her dancing career. Baumbach often analyses strained relationship dynamics, particularly focussing on families and/or

tortured artists. The influence of Naturalism (illusion of reality) on his work is clear; in terms of cinematography, Baumbach tends to use a blend of static wide shots and close-ups to highlight a space that is being inhabited or the key character within the scene. In terms of dialogue, there is a mixture of Naturalism and comedy. Many of Baumbach’s characters have explosive outbursts that represent the irrationality that anger instils in us, and the ridiculousness that comes with it. Yet it is difficult to believe that most people have the same level of wit that his characters possess.

Marriage Story is arguably Baumbach’s most well-known film due to Laura Dern’s Oscar win for Best Supporting Actress, its (more than) 100 additional nominations, and its release straight to Netflix. Baumbach began writing Marriage Story in 2016, using both his and his parents’ divorces as inspiration. Aiming for the most realistic depiction of divorce possible, Baumbach took pains to capture the range of emotions that people often feel during this time. Charlie and Nicole were once in love, and still hold great care for one another and their son, Henry. However, the tension and resentment that is heightened by the divorce leads to an explosive argument, resulting in the pair

apologising, holding each other, and sobbing. The external factors of the divorce only serve to make things more difficult, as others’ opinions and self-interests become intertwined in the matter. This is most prevalent in the legal side of the divorce; the lawyers drive a larger wedge between Charlie and Nicole’s already strained relationship. Charlie’s lawyer, Jay, uses gendered assumptions to demean Nicole and accuse her of alcoholism - a stretch from the truth of Charlie’s anecdote. Nicole’s lawyer, Nora, retaliates against his misogyny and arrogance as the hearing becomes a professional competition rather than a legal proceeding. She does this in defence of Nicole due to Charlie’s last-minute switch to a more aggressive lawyer, yet privately she also feeds into the gendered way of thinking, stating that “the idea of a good father was only invented like thirty years ago”. The aggressive nature of the hearing goes entirely against the civil proceeding that Charlie and Nora originally wanted, and through their subtle expressions and infrequent comments, they ultimately must accept that their divorce is out of their control; their relationship will continue to be strained.

The importance of company and relationships is arguably Baumbach’s most integral theme

across his filmography; the most interesting of which is illustrated by putting characters through forced togetherness and forced isolation, explored in The Meyerowitz Stories and Frances Ha. In The Meyerowitz Stories, three siblings must reunite and work together to ensure their father receives the best possible healthcare, despite their strained relationships. The tension between Danny and Matthew is evidenced by their competitiveness and jealousy of each other, which is heightened by their father consistently favouring Matthew and underappreciating Danny’s efforts. This all culminates in an argument and physical fight that helps the brothers understand their resentment for each other and their father. Their sister, Jean, has been subjected to serious neglect from their father, causing her to become reserved. Ineffective communication is a major factor as to why the Meyerowitz family’s dynamic is so strained, all of which stems from Harold’s neglectful parenting and stubbornness as both a father and an artist.

In contrast, Frances Ha explores unwanted isolation and loneliness. Frances experiences a tumultuous relationship with her best friend, Sophie, leaving her feeling lonely

and depressed. While Frances has several casual friendships, there are several comments throughout the film that suggest that she and Sophie may as well be married. Sophie’s engagement and subsequent move to Japan causes their friendship to break down. Frances begs Sophie to stay in New York, attempting to convince her that she doesn’t truly love her fiancé and that she’d be happier staying with Frances. The theme of the tortured artist is prevalent to Frances Ha; not only does Frances risk losing her strongest relationship, but her career as a dancer is constantly under threat because she doesn’t measure up to the other members of the company - she struggles with both her relationships and her artistic integrity. Baumbach uses various wide shots to illustrate the loneliness Frances experiences. Often there won’t be anyone else in the frame. If there is, they are positioned in the background, not noticing her existence. The cinematography of Frances Ha references French New Wave cinema, mostly from its grey colouring. Perhaps Frances Ha is the clearest example of each of Baumbach’s thematic concerns - the culmination of what makes him an auteur.

As a modern auteur, Baumbach illustrates clear inspiration from older eras of cinema and combines them with his own Naturalistic sense of style, all of which culminates in a series of films that explore the reality and difficulties surrounding relationships. Auteurism is strongly related to art. Baumbach demonstrates this not just through the inclusion of artists, but by making art out of painful, relatable experiences.

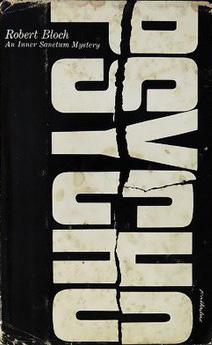

When Robert Bloch’s 1959 horror novel, Psycho, was adapted for our enjoyment on screen in 1960, Alfred Hitchcock made sure to bring the story to life.

Despite them having the same narrative, there are many differences between the two versions, particularly in the shower scene. Some of these changes were made for practical reasons (such as using music to indicate characters’ internal thoughts instead of being outright told in the book), but some were made to suit a different type of audience. Marion (or Mary in the book) Crane’s death remains arguably one of the most memorable death scenes in cinematic history. Indeed, the scene shocked 1960s audiences, leaving a lasting legacy by opening the door to a myriad of cinematic taboos like nudity and violence. Nevertheless, this scene holds several noteworthy differences from the novel.

Prior to Crane’s murder, Bloch structures his novel to allow the reader to engage with the victim’s emotions and thoughts that arise after

By Joe Walker

she steals $40,000. Crane internally considers how to dispose of her car and the cost of her escape from the legal repercussions of her actions “that would sound reasonable” (37). The reader becomes aware of Crane’s feelings towards motel owner Norman Bates, who she refers to as “that pathetic man”, soliloquising that if she had kissed “the poor old geezer [he] would probably faint” (37). Arguably, this literary technique allows readers to engage with Crane in a way that film viewers can’t. Crane’s internal monologue confirms that she views Bates as weak and peculiar, thereby creating a false illusion that there is no danger. Hitchcock’s portrayal differs; Bates secretly watches Crane and harbours sinister motives. The scene contains no dialogue and is instead superseded by brief moments of silence before dramatic music resonates, building suspense before the violence unfolds. Consequently, both versions highlight the semantic field of horror and suspense, via soliloquy in the novel and music in the film to engage readers and viewers respectively.

Both Bloch and Hitchcock convey the theme of suspense in different ways to engage readers and audiences, despite portraying the same scene. Bloch’s literary devices, like the use of

Crane’s soliloquy, create a conversational yet unnerving tone married with sharp staccato sentences to heighten the tension and invite readers into Crane’s mind, such as “Mary stood up.” and “She’d do it.” (37). This technique is less obvious in Hitchcock’s portrayal; instead of dialogue, silence creates an unnerving atmosphere. The film adaptation also makes use of simple cinematography and slow camera movements, allowing audiences to embody the false sense of security felt by Crane prior to her slaughter. Although the dialogue of the narrative is absent, Hitchcock utilises facial expressions representing Crane’s inner torment, thus compensating for the lack of vocabulary. Hitchcock thereby foresees themes of voyeurism and scopophilia (taking pleasure in watching someone without them knowing) when Bates watches Crane through the hole in the wall. Both instances showcase how suspense can be presented both visually and in a literary format to present the same scene though they are outwardly different.

Crane’s murder in the novel differs from Hitchcock’s portrayal in the film in myriad ways. Bloch’s portrayal is described with less detail, commanding a few mere sentences before ending abruptly. This format mirrors the

literary format utilised throughout the scene with the use of short sentences. The sexual undertones in Bloch’s portrayal compensate for the lacking details, for example through the use of white imagery; he implies that after her shower, Crane will “come clean as snow” (38). Traditionally an orthodox view of white is synonymous with virginity and purity, a trait mirroring Crane’s forename which she coincidentally shares with the mother of Christ. Likewise, Crane’s provocative movements symbolise an awareness of her growth into womanhood. Bloch states that “If she’d been a religious girl, she would have prayed” (37), representing how she is becoming supercilious, believing she will get away with her crime and increasing sexuality. Her overconfidence is also proved by her thoughts about herself. Whilst she looks at herself in the mirror, she thinks she has “a damned good figure” and demonstrates “an amateurish bump and grind, tossing her image a kiss”, insinuating her growing self-confidence and sexuality (38). As she giggles to herself numerous times, she implies a lasting immaturity within her. However, moments after this series of self-empowering thoughts, she meets her gruesome death. Crane’s death arguably harbours hellish connotations, as

“the room [begins] to steam up”, symbolising her fate for both her provocative and thieving conduct.

Hitchcock’s version of Crane’s murder is more grotesque and visually disturbing. Although the murder in the novel commands a few vague sentences, Crane’s death in the film remains at the forefront of audiences’ imaginations due to the drawn-out graphic content for shock value. Hitchcock steers away from Bloch’s sexually transparent narrative, thus granting focus on the suspense, violence, and horror. However, the film retains minor provocative elements, such as close-ups of Crane’s legs upon entering the shower and her looking titillated when the hot water from the shower gushes over her body. For the most part, however, these aspects from the novel are overshadowed within the film, as the viewers are ominously and eagerly waiting for something unfavourable to occur. The use of simplistic cinematography is contrasted against the white backdrop of the bathroom, which is eventually darkened by Bates’ arrival, demonstrating how white is used to make the darkness of his shadow and the blood of Crane stand out. Hitchcock’s portrayal presents good versus evil and the

insanity of the human mind, while Bloch’s literary portrayal focuses on the sexual motives underpinning Crane’s murder, despite both examples detailing the same scene.

Spotify has allowed consumers access to an online library of music and podcasts since 2006, gaining high popularity by offering its users an endless supply of music at a fixed monthly rate.

This caused the app to receive an outstanding 226 million premium listeners in 2023, and has even led to it being called ‘the new radio’. Whilst it has introduced a new streaming model to society, it can be argued that it has had a negative effect on artists’ revenue and the sales of older songs and albums.

For most of the 20th century, music consumption relied on listeners buying albums on CD, vinyl, or cassette, or counted on radio DJs to play artists’ new releases. This lack of easy, quick access caused people to frequently pirate music, creating illegal websites to download music for free. To combat this issue, music streaming services such as Apple Music and Spotify were created with the purpose of ensuring that individuals had access to a wide range of music, while

By Katie Mellowes

providing the artists with their entitled revenue. Whilst this has allowed users to have access to a wider range of music, it has impacted how it’s produced within modern society by introducing a new framework for individuals to be able to listen to and enjoy music. This is a huge positive for us as consumers, but still causes a few problems.

This change in the music consumption model had the intention of helping artists receive their deserved revenue, however, it seemed as though Spotify targeted pirating music markets. To compare, when films are pirated, they can rely on box office and DVD sales to help recover from the loss of sales, meanwhile if music is being pirated, there is a lack of physical music revenue (i.e. sales of CDs and vinyl) to help recover from the loss of music sales. This idea of streaming services causes the music industry to have to rely on one revenue instead of two. Spotify’s introduction into the music scene was initially seen as a small disruption but has now transformed into its main advancement. The streaming app has caused a downfall in the sales of CDs and vinyl, as it grants users access to any song or album they want to listen to within seconds –it’s all at the tip of their fingers at a reasonable

fixed price. These days, CDs and vinyl have become relatively expensive and difficult to access. In the late 20th century, vinyl could cost as little as £5, whereas now they are seen as a novelty and can easily cost at least £3040. It’s no wonder we all prefer streaming, with Spotify Premium currently costing £11.99 per month (or £5.99 for students!) and making any song accessible within a few seconds.

Furthermore, Spotify caused a decrease in the selling of other forms of physical media, as the streaming service allows users to not only have all their music on one platform, but also enables them to listen to podcasts, create collaborative playlists, and discover new music weekly. This not only impacts the sales of CDs and vinyl, but will also impact the way that artists produce their music. With the introduction of streaming services, they have begun to focus on producing shorter EPs rather than full albums, as consumers are more focused on the music being released as soon as it’s made rather than waiting for a full-length album. It also means artists can attract a wider audience by drawing them in from one song, rather than hoping that new fans will take a chance on them and buy a whole album on CD, which seems less likely.

It can be argued that there is controversy in the way that artists receive revenue from their songs and albums. Despite ensuring that they would pay artists their deserved revenue, Spotify has in the past failed to meet this promise. In 2009, Lady Gaga only received $167 for her song Poker Face, despite its extreme success and position at the top of the charts. Evidently, she wasn’t paid a fair amount of money that reflected her extreme success, meaning Spotify failed to keep to its word. Additionally, in 2011, many smaller American labels took their music off the streaming service, as they, too, were not being paid revenue that reflected their hard work and success. This does demonstrate the notion that Spotify can pose a threat to artists, who rely on revenue from streaming services such as Spotify to pay for the music they have released. Without fair payment, artists are less likely to want to put their music on streaming sites, as it sometimes doesn’t seem worth it for them.

Whilst this evidence does display the company as being controversial, Spotify has been providing a platform for independent artists to present their music on a global scale. This has enabled a diversification of the music industry and has allowed artists to build

careers and fan bases through streaming platforms. Whilst this is groundbreaking in the music streaming business, it’s still important to recognise that there is an inequality in the way these artists receive revenue from streams, especially within this generation of digital media, where physical media is dying out.

Spotify has revolutionised society’s relationship with music by making it more accessible, personalised, and social. Its impact extends beyond individual listening habits to influence music discovery, industry dynamics, and cultural trends, shaping the ways we experience and interact with music in the digital age. However, whilst it has introduced a new way of listening to music within society, it’s important to consider that there are criticisms, such as the unfair compensation for artists, and causing a loss of physical and cultural connection. Despite this, Spotify has allowed smaller indie artists to have a platform and receive revenue for their music, making it an improvement against old forms of listening that made it difficult for independent artists to be able to distribute their music.

Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite (2004) explores the blend between the comedy and coming-of-age genres, showing us the experiences of socially awkward teen, Napoleon.

The audience’s reaction to a comedy is what creates the legacy of the comedy genre. Napoleon Dynamite seems to attract a specific audience that is fascinated with an awkward, unconventional comedy. This film connects audiences through humour and laughter, allowing it a cult status.

The satirical element of Napoleon Dynamite allows the ‘nerd’ characterisation of Napoleon to be exaggerated, adding to its humour. This film sits with others like Juno (dir. Jason Reitman, 2007), Superbad (2007), and even The Breakfast Club (1985), which focus on the high school experience. Often, these films demonstrate stereotypical cliques commonly associated with high school, specifically the ‘nerd’. Napoleon Dynamite follows the life of Napoleon; his characterisation, dialogue,

By Layla Wilson

and storylines creates one of the dominant sources of the audience’s reaction to this comedy - mostly laughter and joy. Napoleon is particularly unique in his depiction of a school nerd. His specific facial expressions, repetition of certain phrases like “Gosh!”, and body language give him the relevant comic persona that makes us respond with laughter. His oversized glasses, slightly parted lips, and famous curly hair are what make his character recognisable to his cult audience. The film’s cult appeal may be down to the dilemma of whether we’re supposed to laugh at Napoleon’s characteristics and mannerisms, or whether we’re laughing with him, because of his self-confidence.

Other characters in the film also bring a sense of belonging to a cult audience, especially as they are a group of outsiders, which some audiences may relate to. We are introduced to his brother, Kip, who has a particularly camp demeanour. Although difficult to define, his personality and exaggerated characteristics play on the sense of intrigue that the term ‘camp’ may have on us. Kip has a certain femininity and exaggeration about him that triggers camp stereotypes. For example, his elongated pronunciation of words creates a sense of intrigue for his character, also adding

comedic effect. The film and its variety of characters create a sense of belonging, due to each character’s unique quirks.

Napoleon Dynamite’s use of sound also contributes to its comedic attributes. For example, there is an excessive use of silence and diegetic sound as its main source of audio. Throughout the movie, we hear chirping birds, rustling packets, footsteps, etc., that grant it an awkward yet familiar feel. The lack of music and non-diegetic sounds aid the sensation that the film involves us in the lives of the characters; we experience the sounds that Napoleon and the other characters experience, allowing a relationship between the characters and the audience. When the sound is diegetic and high volume, this allows us to pay closer attention to the world of not only hearing but also seeing. Although this film is relatively slow-paced with little action, we still pay close attention to the exaggerations in the sight and sound of the film. In this way, the silent qualities of the movie contribute to the comedic aspects - our senses are heightened and more sensitive to the exaggerated sounds, visuals, and actions. Even when music is played, it’s heard and experienced by Napoleon. For example, in his sign language performance in class, the music is heard by the characters, who watch

Napoleon display sign language. The shot after this shows the other students somewhat awkwardly watching him, adding to this comedic sense of irony that we too are doing the same. However, there is beauty in the fact that Napoleon’s character is unaware of the judgement and speculation surrounding him.

Finally, we see the famous dance scene, where Napoleon joins his friend, Pedro, in his campaign to become class president. Napoleon performs a last-minute skit for the campaign, which births a famously humorous dance routine. It’s a similar experience to the sign language performance, in that we take the position of his classmates being the audience, except this time, Napoleon takes centre stage and performs individually. The dance begins awkwardly, causing a sense of second-hand embarrassment amongst the audience. There’s an intentional use of body humour to convey refreshing comedic value. This dance involves atypical dance moves, something we are not used to, yet Napoleon’s body movements and careless dance flow are admirable. He receives a heart-warming standing ovation from his fellow classmates, resonating with this secret rooting we have developed for Napoleon throughout the film.

He receives the recognition he deserves for his “sweet skills”, as self-described by Napoleon. The use of music also adds to the peculiar yet spectacular dance sequence. The use of the song Canned Heat by Jamiroquai seems to perfectly capture the essence of Napoleon and his camp sensibility, as well as comedic value. The rhythmic value of this song can’t help but spark this desire to resonate in the ‘groove’ of Napoleon Dynamite as the spotlight shines on its protagonist.

To conclude, the peculiarity and ‘otherness’ throughout this film greatly highlight its cult comedy aesthetic. It’s not your typical slapstick or satirical comedy, yet it conforms to the expectation of a comedy in that it puts a smile on your face and creates laughter in response to loveable Napoleon. Its awkwardness is what creates this refreshing outlook on comedy; we don’t quite understand what’s funny, yet our response confirms the film’s sense of humour. It seems to rely on a particular audience to understand the comedic value of just watching a satirical exaggeration of a teenage boy and simply enjoying it.

The emotional complexities of grief and its many manifestations have been explored widely across film and media, with 2023 bringing audiences Andrew Haigh’s metaphysical All of Us Strangers.

Haigh’s delicate, modern ghost story explores deep themes such as parental loss, grieving, and isolation, but also emphasises the overwhelming power of love, despite its risks of loss. Adam is an isolated screenwriter living in London. Whilst attempting to seek writing inspiration from his deceased parents, he happens upon their spirits, just as they were on the day that they died when he was young.

Inspired by Taichi Yamada’s 1987 supernatural novel, Strangers, the film diverts from its source material, most notably with Haigh’s version featuring a homosexual relationship between Adam and Harry. This initial encounter with a drunken and suicidal Harry acts as the catalyst for many of the emotional beats of the film, coinciding with Adam’s visit to his childhood home and the discovery of his parents. He later has the opportunity to open up to them

By Ren Anthony

about his sexuality - something he was unable to accomplish while they were living. The addition of a queer relationship explored across the narrative seemingly heightens the idea of loneliness, with certain dialogue and themes finding particular emotional resonance to audiences that identify outside of the heteronormative framework of society’s expectations.

The existence of All of Us Strangers as both a modern ghost story and a delicate examination of grief is clearly emphasised by the diegetic sound design of the film. Adam’s detached and liminal experiences of the world are intricately tied to the loneliness that the dialogue across the narrative describes, and is especially reflected in the film’s sound design. Heavy silences are intensified by the distinct lack of usually expected diegetic sounds across most areas of the plot, and so when arbitrary sounds such as plastic packaging being moved occurs, the comparison is sharper and more emphasised. The effect of this near silence resonates cohesively with the subject matter and the theme of ‘aloneness’; the silence amplifies the feelings of loneliness and yet paradoxically exists due to Adam often being on his own.

Adam’s physical existence and psyche mirror one another, where he perhaps exists in liminality. This isolation is often compounded by the visual motif of Adam at different windows, looking out at the wider world, but never integrated. This could be read as him being physically detached, like his parents’ spirits. The atmosphere of the flat is accented by muffled diegetic sounds outside, which could be likened to the muted sounds of being underwater, facilitating an almost other-worldly feeling of disconnection. Furthermore, the notion of being underwater is often used across poetry and culture to describe feelings of being overwhelmed, or suffering from depression or isolation. Both the visual and audible quietness are notably apparent within scenes located in the seemingly otherwise empty block of flats where Adam resides. A theoretical interpretation focuses upon the implication that Adam himself is trapped in a metaphysical limbo, in between life and death. Harry acts as a troubled but guiding spirit to allow him to process his grief and move on both spiritually and emotionally. This interpretation could further inform the flat’s emptiness. Perhaps the flat is not entirely devoid of other inhabitants, but instead left open to individual interpretation to heighten both the metaphysical aspects of the narrative, as well as the limbo-like isolation that grief is often showcased as.

The visual motifs continue to imply the isolation of Adam’s living conditions, and again can potentially imply how the loneliness in Adam’s life has obscured the rest of the world’s population. In the first instance of verbal contact between Harry and Adam in the doorway of Adam’s flat, the blocking of the scene could hint towards both Harry’s fear of rejection, as well as Adam’s reluctance to allow people to enter into his life, speculatively for fear of losing them. These images can prompt explorations of how trauma itself can be isolating, but also how it can be easy to remain there in the ‘comfort’ of sadness. The door is the physical and metaphorical barrier between the two; Harry leans into the doorframe, desperately signaling his desire for human connection, whereas Adam is shielded by the door, almost in need of protection and obscurity.

The emptiness of both physical and emotional detachment is emulated throughout the visual style of All of Us Strangers. This concept of isolation can be further explored in the incendiary imagery of rising flames as the narrative progresses. The first notable indication of flame-like imagery involves the fire alarm that incites Adam’s initial silent contact with Harry. The abruptness of the

alarm immediately shatters the fragile silence, however as Adam vacates the block of flats, it is noted that it is only he who appears to be waiting outside. Across the course of the narrative, Adam progressively becomes more unwell, with his physical body temperature rising - perhaps readable as a response to trauma, with mental health issues often being manifested physically. These allusions to illness could also heighten the symbolism of the gay community’s past with the 1980s AIDS crisis, and the fear of contagion and disease. Themes of queerness and grief can often be read in cultural conjunction with one another, due to the community’s ongoing fight against oppression, prejudice, and discrimination, which has over time caused the loss of many members.

Across the length of the film, a multitude of cinematic techniques are used to symbolise the mental barriers that different characters either create or overcome, as well as to emphasise the power that love can have. Haigh’s emotionally resonant dialogue, the mise-en-scene (the overall look and feel of a film), the sound design, and the performances by the cast all cohesively contribute to a truly devastating and beautiful exploration of grief, loneliness, and the power of love.

Every year we become more and more reliant on technology. One of the main goals of a tech company is to make their products a necessary part of our lives, something that we didn’t know we needed until we used it and now can no longer live without.

The everyday life of average people is continuously changing in order to keep updated with the latest technological ‘necessities’.

One way in which a company can create an everlasting successful technological product is by making it wearable, quite literally a part of a person. It’s argued that a phone is already just an extension of a human at this point but recently, technology companies have taken it as far as performing surgeries to connect people to their tech. Biohacking supposedly changes people’s lifestyles for the better by installing science and technology methods to alter their biology. Vitamins and supplements

By Ruby Thornton

are no new invention, rather it’s the technological side of biohacking that seems to be raising concerns, specifically ethically. The company Second Sight placed their technology into people’s heads and charged them money for visual prosthetics, intended to aid people with vision loss. The company went bankrupt and closed, leaving customers stranded with bionic eyes that no longer had a use. Customers have to place their trust in a tech company when undergoing these procedures, but perhaps that’s not safe. Biohacking to aid people with disabilities can change their overall experience of life, creating a positive impact, but more recently companies such as Apple and Neurolink are marketing devices for everyone, even if they don’t need them. Also, Apple has admitted to slowing down previous versions of their products to force you to upgrade, so why would you want them to implement their technology in your body? What if you can no longer afford to upgrade the technology that is embedded under your skin? This is all very new, and important to question before jumping on the technological trend.

Already within the scientific world, people are sceptical of new health endeavours, let alone allowing someone to alter your body

unnecessarily. These new body modifications seem in most ways built out of laziness - for example, getting a chip placed in your hand instead of just owning a key for your front door. Time, and saving it, is what people are prioritising, which is where biohacking comes in. This means that if these time-saving advancements take off and you don’t follow through with biohacking yourself, you may be placed in a position of disadvantage, with the rest of the world experiencing life at twice the speed and efficiency. This disadvantage could prevent you from making enough money to sustain an average lifestyle - you have to keep up or you’ll be left behind.

Furthermore, due to wearable and biological technology, there is the concern that we are always in some way or another connected to the internet. In 1970, a theorist named Alvin Toffler discussed his idea of ‘knowledge implosion’, which essentially captures this concern that the amount of information that is easily accessible and consumable by modernday society creates issues for individual members of the public who are consuming an overwhelming level of information at a worryingly fast rate. This phenomenon is becoming more and more applicable as

time goes on. Toffler coined this term in 1970, before we even had access to an inch of the technology we have now. It’s almost impossible to have a healthy lifestyle by disconnecting yourself from the rest of the world when it’s so easy to consume, especially now with the introduction of biohacking technology that in the future may be impossible to disconnect from. Another worry concerning our constant access to technology is the continuous comparison of people engaging with it. We constantly see what others do, and observe the lives between people who appear to be better off than ourselves. People are placed within a paradoxical position of narcissism and jealousy, creating and observing fake personas that only represent a minor portion of who they really are. The way people experience life is through a third-person lens, rather than their own point of view. This further demonstrates how many people struggle to separate the technological world from the real world.

Finally, this brings us to probably the biggest concern, which is how unreliable technology can be. As previously mentioned with the examples of Second Sight and Apple, tech

companies seem to operate through their own fruition, prioritising capitalist goals over the consumers’ well-being and experiences. Over the past few years, people, especially those within the newest generations, have become reliant on technology in order to function. Nowadays you can’t book doctor’s appointments, apply for jobs, or even get an education without access to the internet and technology. We have become reliant on devices that come from an unreliable source. Humans make mistakes; therefore, so does technology. Even technology that has existed for centuries can still falter and break. Therefore, relying on technology that has been intertwined with your body could have a severe negative impact on your life.

To conclude, lifestyles are being forced to adapt and rapidly change at a higher rate than ever due to the increasingly evolving technological discoveries. As one develops, so must the other if people wish to be a part of mainstream society. This also means it’s getting increasingly more expensive to keep up with societal expectations, aiding the evergrowing class divide to only keep increasing.

Mathijs and Sexton write in their book Cult Cinema: An Introduction that, ‘cult media has often been identified through the fan devotion that it has given rise to.’ (2011, p.57).

Over the last several decades, fan devotion to certain fiction that was viewed as a part of underground ‘geek’ culture has become a major part of mainstream popular culture.

One key feature that evidences this has been the rise of the fan convention. The tradition of the convention has its roots in the sci-fi fan clubs established in the 1920s and 30s in America: small communities formed by fans of sci-fi films and comic books who would correspond both through newsletters and, whenever they could, in person. These groups grew in numbers throughout the 1930s, and eventually started holding conventions. Starting small-scale, with 200 people attending the World Science Fiction Convention in 1939 in New York, the concept of the convention has grown over the decades to the point where the most popular fan conventions today regularly attract upwards of 100,000 attendees. They

By Deacon Fenton

are often focused on specific franchises, such as the powerhouses of Marvel or Star Trek (with this franchise being a game changer in terms of the rise of the convention), or genres, particularly sci-fi and horror, perhaps implying that these films and genres are more connected to intense fan devotion. One key factor in the appeal of conventions is the feeling of belonging among people with similar niche tastes, which were often ridiculed by mainstream society. As Lynn Zubernis describes in the book The Routledge Companion to Cult Cinema, ‘The outside criticism has, from the beginning, drawn fans together into tight-knit communities of likeminded people who felt like outsiders’ (2019, p.259).

A connecting part of this culture is merchandise. Many media products have given way to a variety of associated paraphernalia, such as T-shirts, action figures, and prop replicas to name but a few. These products are mostly from popular franchises, although companies such as Funko have strived to attract cult audiences, making POP Figures of characters from niche favourites such as American Psycho (2000) and The Crow (1994). These products are enjoyed by a sizable proportion of the population, as

evidenced by the tremendous success of Disney merchandise, which makes over 5 billion dollars in revenue yearly. This can be furthered in the popularity of more specialist replicas of iconic props from films, designed with accuracy in mind, which offer the illusion of a fictional object becoming part of one’s lived world. The realisation of fictional objects and characters into reality also provides opportunities for fans to create new stories, which can be seen in the practice of playing with action figures, popular among younger fans, and as collectables among devoted lifelong fans with some money to spare. Some may see this as childish, but such behaviour isn’t too dissimilar to that of the vinyl collector or the sports memorabilia enthusiast.

One way in which cult fans may in particular create alternative ways of engaging with films is through the concept of ironic appreciation, where a film is enjoyed in a way that was not intended by the directors or producers. Candidates for this appreciation are often ‘sobad-it’s-good’ films, where the axis of artistic taste is turned on its head. One example is Reefer Madness (1936). Originally intended as a social problem film about the apparent dangers of marijuana, the film, derided as a piece of hysterical propaganda for decades,

was later rediscovered by the community of marijuana users, who enjoyed the film’s overthe-top melodrama and reclaimed it as a cult classic. Other films such as Tommy Wiseau’s The Room (2003), were never going to win any awards on the Oscar/Cannes circuit, but have retained a loyal and dedicated audience who have great affection for the film exactly because of its many ‘flaws’.

Some films are made with the specific intention of capturing this ‘so-bad-it’s-good’ quality, such as Birdemic 2: The Resurrection (2013) but have not been embraced in the same way as the likes of The Room. Many cult viewers prefer sincerity (unintentional badness in films intended to be good) to intentional badness, which they see as missing the point. In this way, the appreciation of ‘so-bad-it’sgood’ films resembles the enjoyment of ‘camp’ appeal. As Susan Sontag famously wrote in her essay Notes on Camp, ‘the pure examples of camp are unintentional: they are dead serious’ (1964, p.6). The cult viewer, aware of traditional notions of ‘good’ and ‘bad’, decides to disconnect these with their subjective enjoyment, enjoying films, not in spite of, but because of their failures, which become entertaining due to their extremity.

Cult fans also engage with films through participatory screenings (sometimes held at midnight), where the audience, in contrast to the general rule of keeping quiet in the cinema, dress up, repeat lines, and generally ‘play along’ with the film. The most notable example of the ‘midnight movie’ film, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), saw midnight screenings as early as 1976, where audience members turned up dressed as key characters from the film, heckled the characters on screen, and threw props around the auditorium. For fans, the appeal lies not just in watching the film, but also in transforming the film into an active experience,

and above all else, being able to do this with other fans in real time, not unlike those attending a concert or sporting event. In this respect, film can go from being a singular viewing experience to a fundamentally social one, and sees people turn their backs on the online world for an authentic appreciation of the art that they and others share a love for.

David Cronenberg’s sci-fi horror film Videodrome (1983) dissects fears around how media affects society and the media subject, expressing this through a physical and psychosexual metaphor.

This primary use of literal body-affecting media is hugely indebted to the media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who was the first major media theorist to discuss the intersection of media technology and the body.