2 (40) 2025

saganmanaTleblo-sazogadoebrivi Jurnali

2 (40) 2025

saganmanaTleblo-sazogadoebrivi Jurnali

2 „TavaqaraSviliseuli~ vefxistyaosnis mxatvroba THE ILLUSTRATIONS OF THE “TAVAKARASHVILI MANUSCRIPT” OF “THE KNIGHT IN THE PANTHER’S SKIN”

12 grigol robaqiZis erTi ucnobi werili AN UNKNOWN LETTER BY GRIGOL ROBAKIDZE

18 balo! baloo! / BALO! A CRY FROM THE DEPTHS OF TIME

24 eh, guram gabiZaSvilo, guram! / REMEMBERING GURAM GABIDZASHVILI

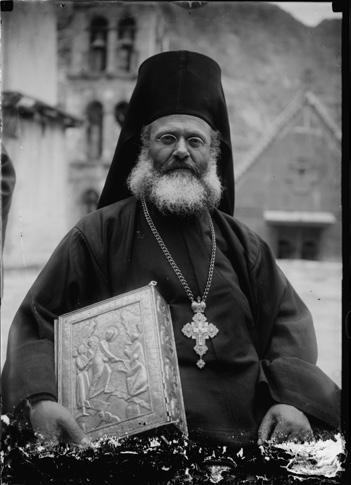

36 sinas mTa / MOUNT SINAI

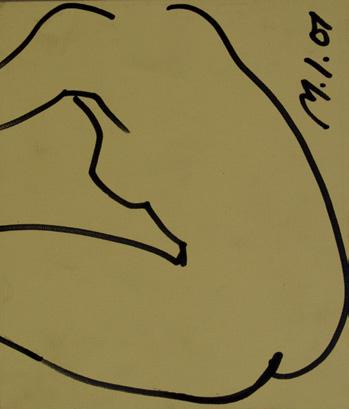

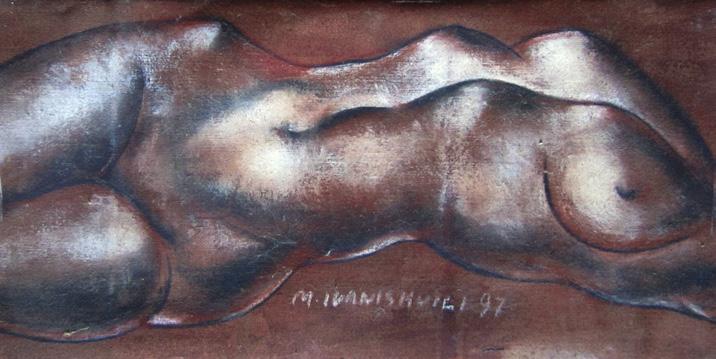

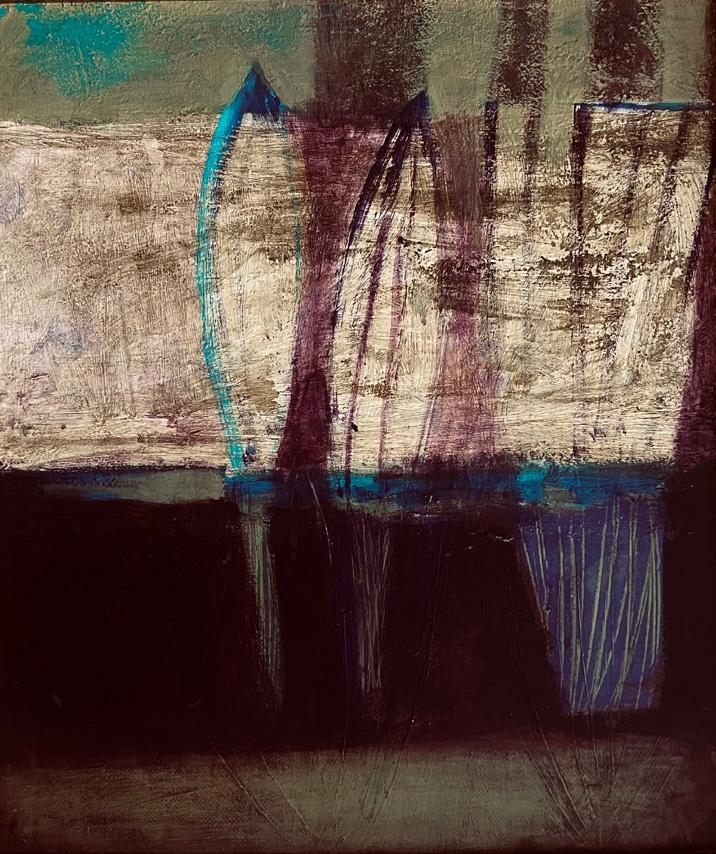

44 marina ivaniSvili / MARINA IVANISHVILI

58 iliko morCilaZe - erTi gundis ukvdavi xma / ILIKO MORCHILADZE – THE IMMORTAL VOICE OF A CHOIR

62 BASSO CONTINUO...

70 idumali samyaro fardis miRma / THE MYSTERIOUS WORLD BEHIND THE CURTAIN

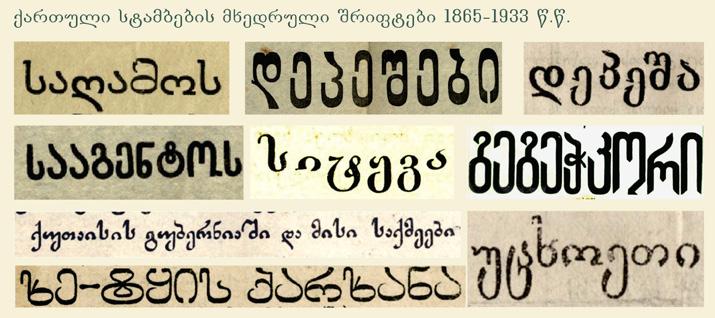

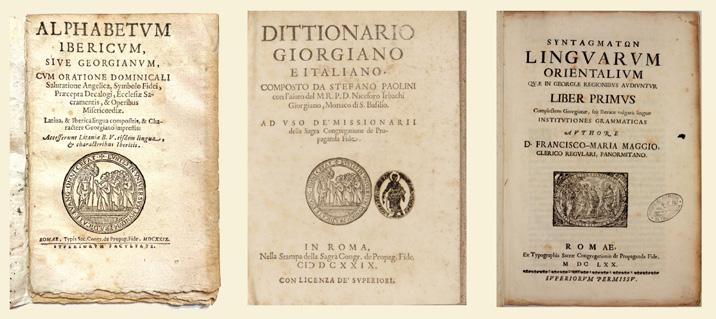

82 qarTuli „moZravi aso~ / GEORGIAN MOVABLE TYPE

92 nodar tabiZe - da zecas vumzer saxuravidan... NODAR TABIDZE AND I GAZE AT THE SKY FROM THE ROOFTOP…

saredaqcio jgufi / EDITORIAL STAFF

revaz iukuriZe / REVAZ IUKURIDZE

xaTuna kereseliZe / KHATUNA KERESELIDZE

ekaterine CulaSvili / EKATERINE CHULASHVILI

gvanca fifia / GVANTSA PIPIA

mariam gabedava / MARIAM GABEDAVA

dizaineri / DESIGNER

nikoloz bagrationi / NIKOLOZ BAGRATIONI

el-fosta: kulturaplusm@gmail.com facebook.com/kulturaplusm www.kulturaplus.ge

beWdva: favoriti stili / Print: Favorite style

gamodis kvartalSi erTxel / Issued quarterly JurnalSi ganTavsebuli masalis gamoyeneba SeiZleba mxolod redaqciis TanxmobiT The materials published in this magazine cannot be used without the authorization of the editorial staff fotomasalis mowodebisTvis madlobas vuxdiT korneli kekeliZis saxelobis saqarTvelos xelnawerTa erovnuli centrs

ISSN 2346-8165

eTer ediSeraSvili

„TavaqaraSviliseuli~

ETER EDISHERASHVILI

THE “TAVAKARASHVILI MANUSCRIPT” OF “THE KNIGHT IN THE PANTHER’S SKIN”

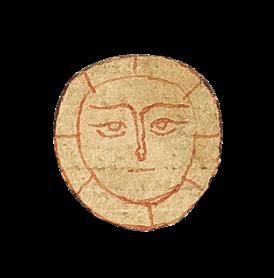

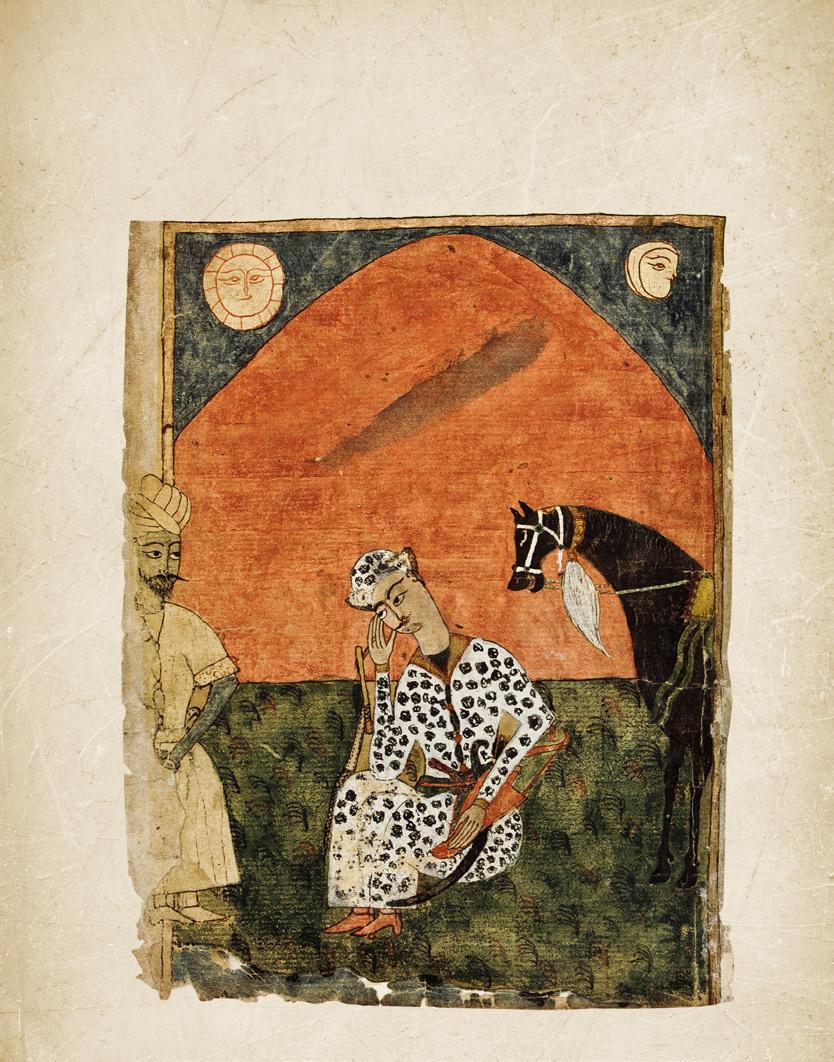

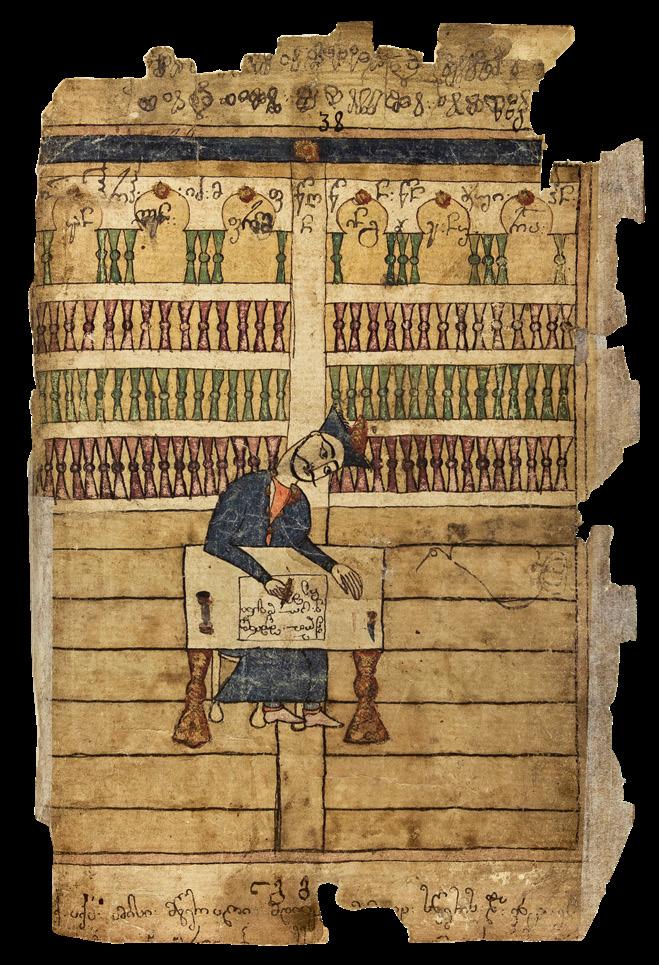

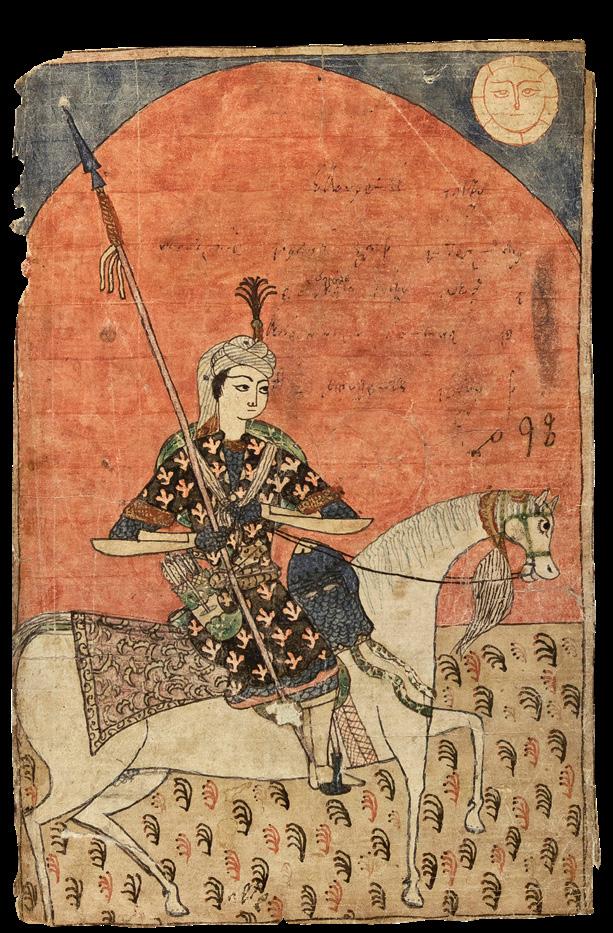

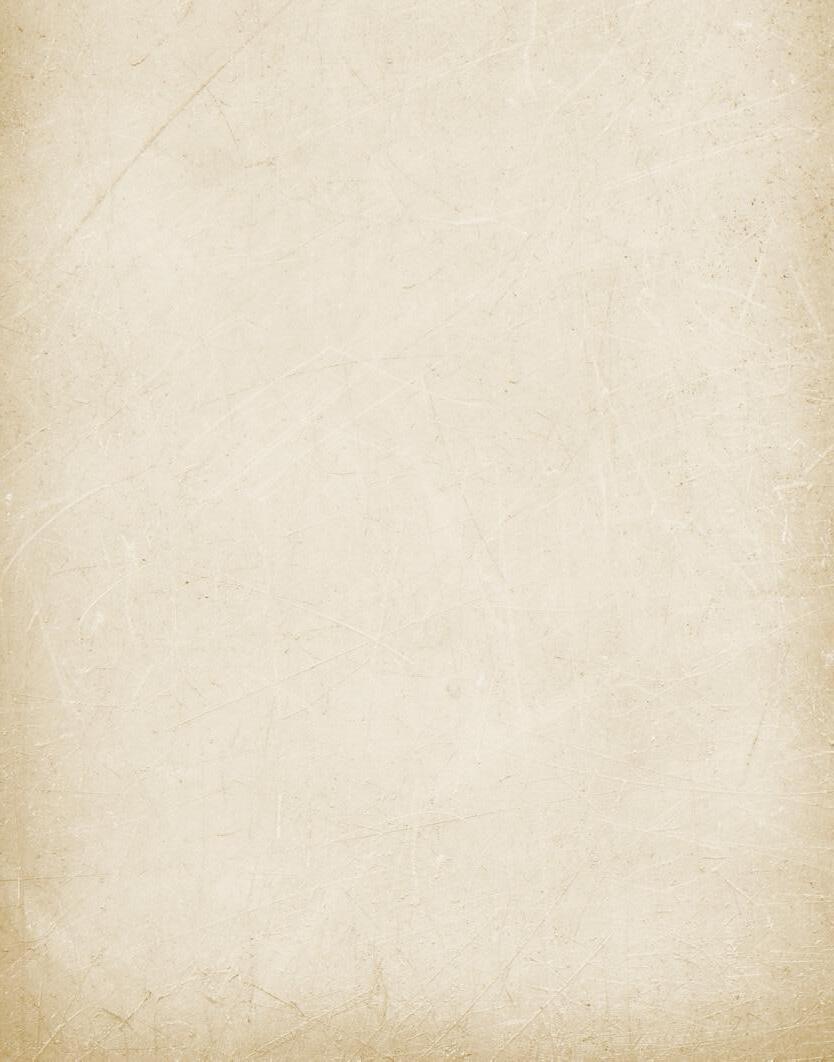

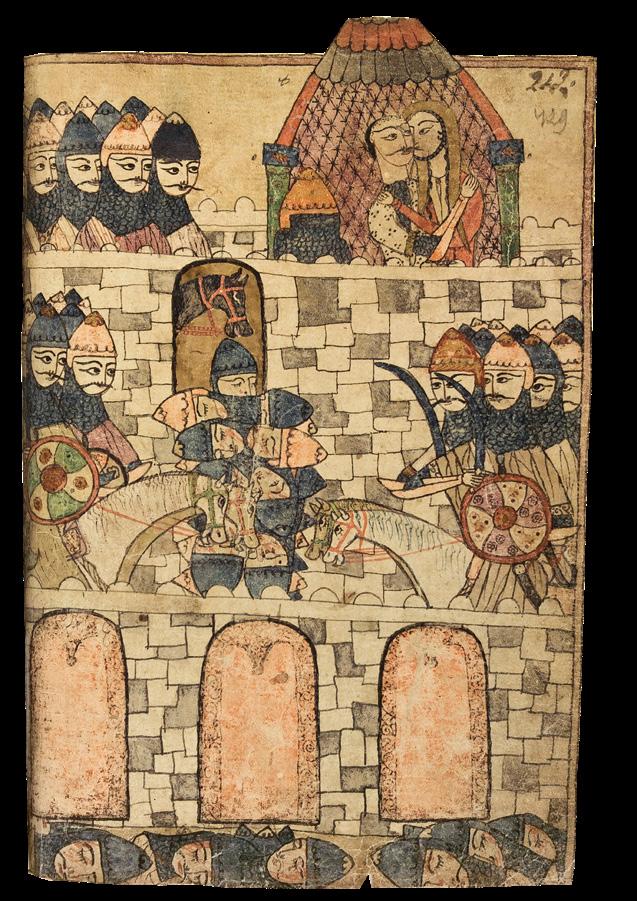

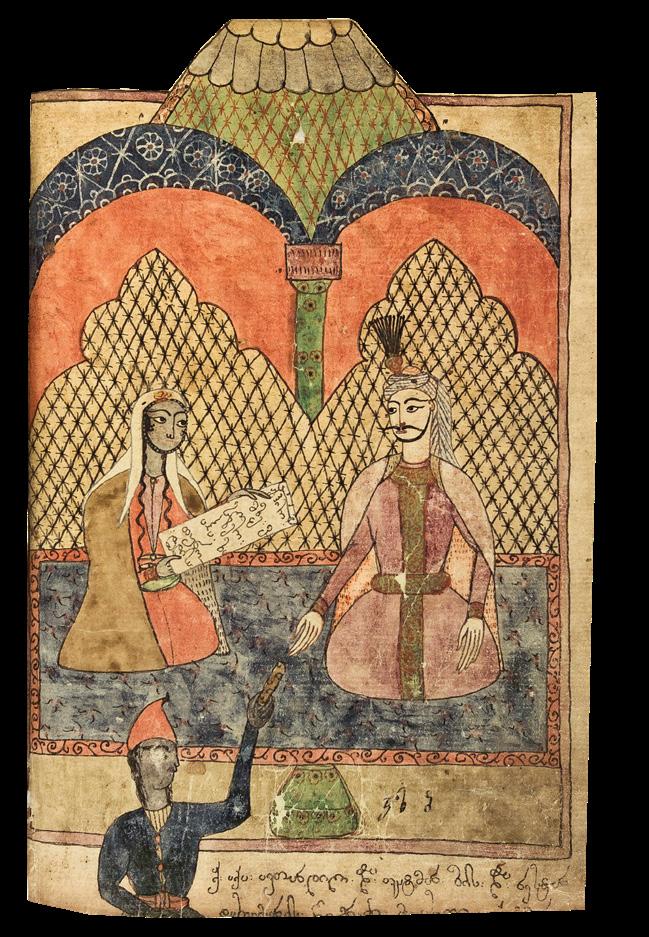

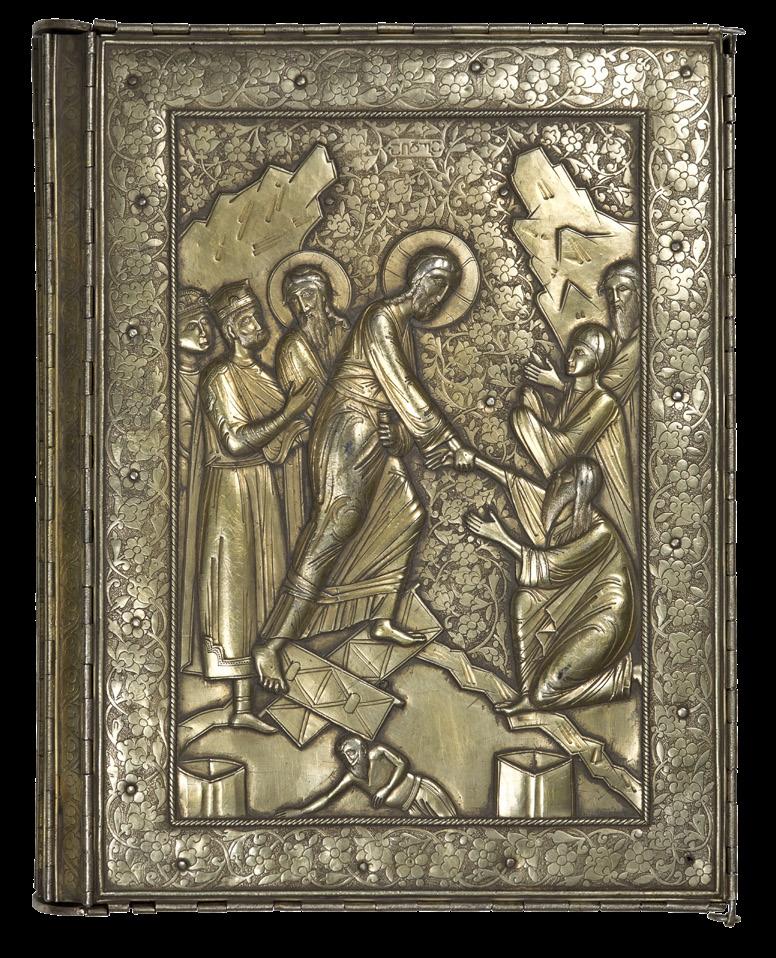

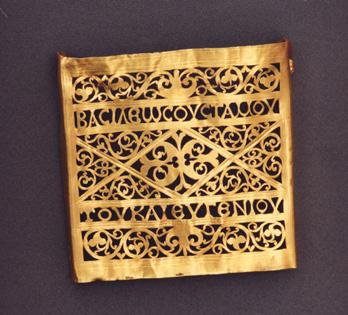

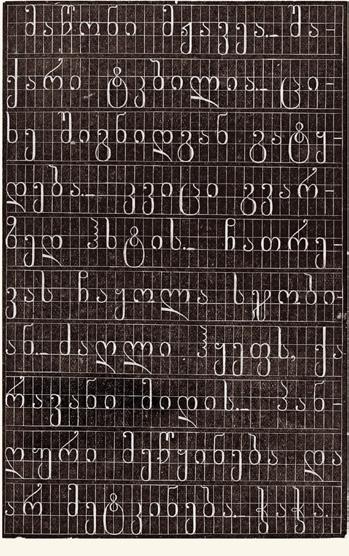

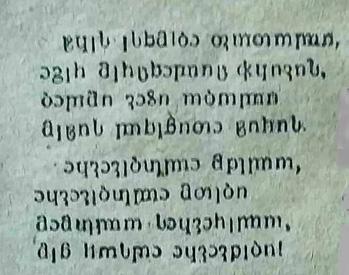

„TavaqaraSviliseulis~ saxeliT cnobili „vefxistyaosnis“ nusxa da misi mxatvroba poemis dRemde moRweul xelnawerebs Soris erT-erTi yvelaze cnobili da gamorCeulia mxatvruli, kulturuli da istoriuli TvalsazrisiT. is daculia korneli kekeliZis saxelobis saqarTvelos xelnawerTa erovnul centrSi H 599 SifriT. xelnaweri (27x19 sm.) 267 furclisgan Sedgeba da naweria mxedruliT, qaRaldze. xelnawers mTel gverdze gaSlili 39 miniatura amkobs. mxatvrul-stiluri maxasiaTeblebis mixedviT aSkaraa rom 38 ilustracia, romelic poemis sxvadasxva epizods asuraTebs, xelnaweris Seqmnis procesSia CarTuli da erTi ostatis xels ekuTvnis. erTi maTgani ki, romelic imeorebs TinaTinis taxtze dasmis scenas, sparsuli miniaturisgan mZlavrad STagonebuli mxatvrul-stiluri maxasaTiaTeblebiT mkveTrad sxvaobs danarCenebisgan. savaraudod, is sxva xelnawers ekuTvnoda da am nusxaSi xelnaweris Seqmnis Semdeg unda iyos CarTuli.

TavaqaraSviliseuli `vefxistyaosani“ sadReisod poemis Cvenamde moRweul pirvel TariRian nimuSad iTvleba. misi dRevandeli saxelwodeba gadamweridan, mamuka TavaqaraSvilidan momdinareobs, romlis vinaobas da xelnaweris Seqmnis istoriasac TandarTuli anderZminawerebi avlens: „q. RmerTo Semindev codvani Cem...~ qvemoT miwerilia: „aqa amisi mwerali mdivani mamuka swers da vinc es...~ (252 r).

mamuka TavaqaraSvili imereTis samefos mdivanTa sagvareulos warmomadgeneli da imerTa mefis, aleqsandre III-s (1639-1660) mdivani iyo. igi 1634 wels tyved Cauvarda levan II dadians (1611-1657), mas mere rac am ukanasknelma Tavis mokavSiresTan _ rostom qarTlis mefesTan (1633-1658) erTad kakas xidTan gamarTul brZolaSi imereTis mefe giorgi (1604-1639) da kaxeTis mefe Teimurazi (1606-1648) daamarcxa. TavaqaraSvilma odiSis samTavroSi, tyveobaSi, 23 weli gaatara. swored levan II dadianis dakveTiT, misive karze yofnisas gadawera 1646 wels „vefxistyaosnis~ nusxa _ `dideba srulmyofelsa RmerTsa, yovelTa Semwe-mfarvelsa. viwye es vefxistyaosani TibaTvesa cametsa, srul vyav

The manuscript of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” known as the “Tavakarashvili Manuscript” and its illustrations represent one of the most renowned and distinguished among the extant handcopied versions of the poem, in terms of its artistic, cultural, and historical value. It is preserved at the Korneli Kekelidze Georgian National Centre of Manuscript under the catalog number H 599. The manuscript (27x19 cm) consists of 267 folios and is written

Tvrametsa agvistosa, q-ksa samas ocdaToTxmetsa. Tu ram akldes, nuravin damwyevliT, tyveobaSid vswerdi. SigniT ocdacxra rveuli aris, furceli oras ocdaTormeti“. (267 v). mkvlevarTa Soris mxatvrobis avtoris Sesaxeb mecnierTa azri orad iyofa: nawili mamuka TavaqaraSvilsve miiCnevs momxatvelad, xolo nawili am mosazrebas ar iziarebs.

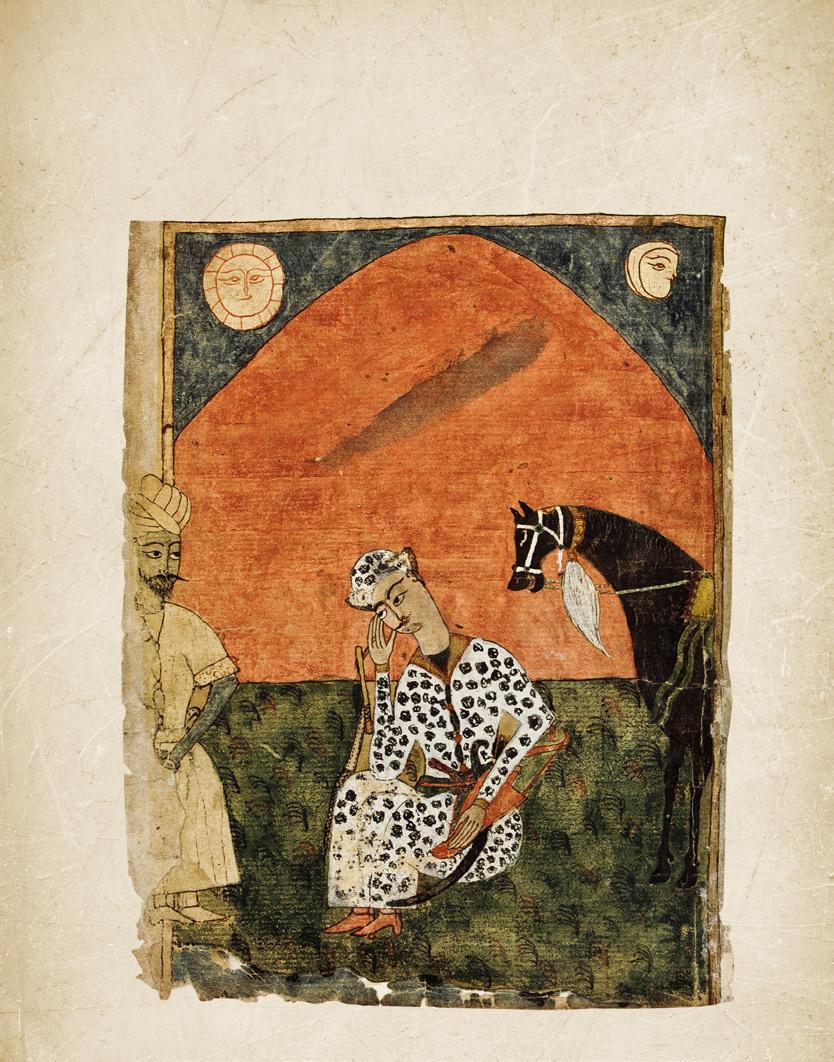

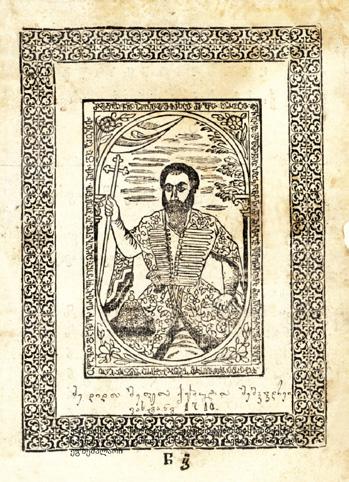

„vefxistyaosnis~ dasuraTeba mkiTxvelis winaSe zemoT moyvanili minaweris erTgvari ilustraciiT „ixsneba“, romelic xelnaweris Seqmnis istoriasTan erTad, misi damkveTis pirovnul Strixebsa da Tanadrouli epoqis msoflmxedvelobasac warmoaCens. pirvelive miniaturaze kompoziciis zeda nawilSi, centrSi warmodgenilia levan dadianis frontaluri, aRmosavlur yaidaze muxlmoyrili, gamosaxuleba or mxlebels Soris. qveda registrSi ki, erTmaneTis pirispir, 3/4-Si mocemuli aseve muxlmorTxmiT mjdomi ori figuraa gamosaxuli. mkvlevarTa mosazrebis Tanaxmad, SoTa rusTaveli poemis teqsts karnaxobs gadamwers, mamuka

in the mkhedruli script on paper. It is adorned with 39 full-page miniatures. Based on its stylistic features, it is evident that 38 of these illustrations – depicting various episodes from the poem – were executed during the creation of the manuscript and are the work of a single artist. One miniature, however, which repeats the scene of Tinatin’s enthronement, markedly differs from the others in its stylistic characteristics, being heavily inspired by Persian miniature painting. It likely belonged to another manuscript and was added to this one after the main manuscript was completed.

Today, the “Tavakarashvili Manuscript” of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” is considered the earliest dated version of the poem that has survived. Its current name derives from the scribe, Mamuka Tavakarashvili, whose identity and connection to the manuscript are revealed in accompanying colophons: “Lord, forgive my sins…” followed by: “Here the writer of this, scribe Mamuka, writes, and who…”.

Mamuka Tavakarashvili was a member of a noble family of royal scribes in the Kingdom of Imereti and served as a scribe to King Alexander III of Imereti (r. 1639–1660). In 1634, he was taken prisoner by Levan II Dadiani (r. 1611–1657), after the latter, allied with Rostom, King of Kartli (r. 1633–1658), defeated King Giorgi of Imereti (r. 1604–1639) and King Teimuraz of Kakheti (r. 1606–1648) at the Battle of Kakaxidi. Tavakarashvili spent 23 years in captivity in the Principality

TavaqaraSvils, romlis muxlebze gaSlil gragnilzec ikiTxeba: „q. ese ambavi...~. mamuka TavaqaraSvilis kidev erT, magidasTan mjdom, weris procesSi warmodgenil portrets vxvdebiT xelnaweris bolos. aRsaniSnavia, rom gadamweris gamosaxva (Tan orgzis!), aseve misi qtitorTan warmodgena, qarTuli Sua saukuneebis miniaturisTvis iSviaT movlenas warmoadgens da rogorc xelnaweris damkveTis, aseve mdivan-mwignobris statussa da mniSvnelovanebaze miuTiTebs. sagulisxmoa da gansakuTrebiT aRsaniSnic levan II dadianis gamosaxuleba, romlis portretuli Strixebi _ mogrZo saxis ovali, grZeli, swori cxviri da axloaxlo Camjdari viwro Tvalebi, asociacias iwvevs kedlis mxatvrobasa Tu Weduri xelovnebis nimuSebze warmodgenil mTavris portretebTan (walenjixis, xobis, korcxelis eklesiaTa moxatulobani, korcxelis winaswarmetyvelTa da iloris wminda giorgis Weduri xatebi _ yvela XVII saukune). xelnaweris pirvelsave gverdze sakuTari reprezentaciuli portretis gamosaxva da xelnaweris Seqmnis istoriis ilustrireba levan dadianis mkafio ganacxadi iyo Tu ra mniSvneloba hqonda misTvis „vefxistyaosnis~ gadaweras da misi mxatvrobiT Semkobas da rac, srulad epasuxeboda mis kulturul Tu politikur nabijebs. odiSis samTavros mmarTveli im gamorCeul istoriul figuraTa Soris dgas, romelmac, aqtiuri kulturuli saqmianobis da interesTa mravalferovnebis Sedegad, mniSvnelovani mxatvruli memkvidreoba datova. levan dadianis karze Tavs iyridnen sxvadasxva qveynidan mowveuli ostatebi da mxatvrebi, ikribebodnen vaWrebi da misionerebi, romelTac, mTavari did mxardaWeras ucxadebda. gviani Sua saukuneebis qarTuli xelovneba da kulturuli sivrce rTulad warmosadgenia misi patronaJiT Seqmnili oqromWedlobis, kedlis mxatvrobisa Tu sxva nimuSebis gareSe.

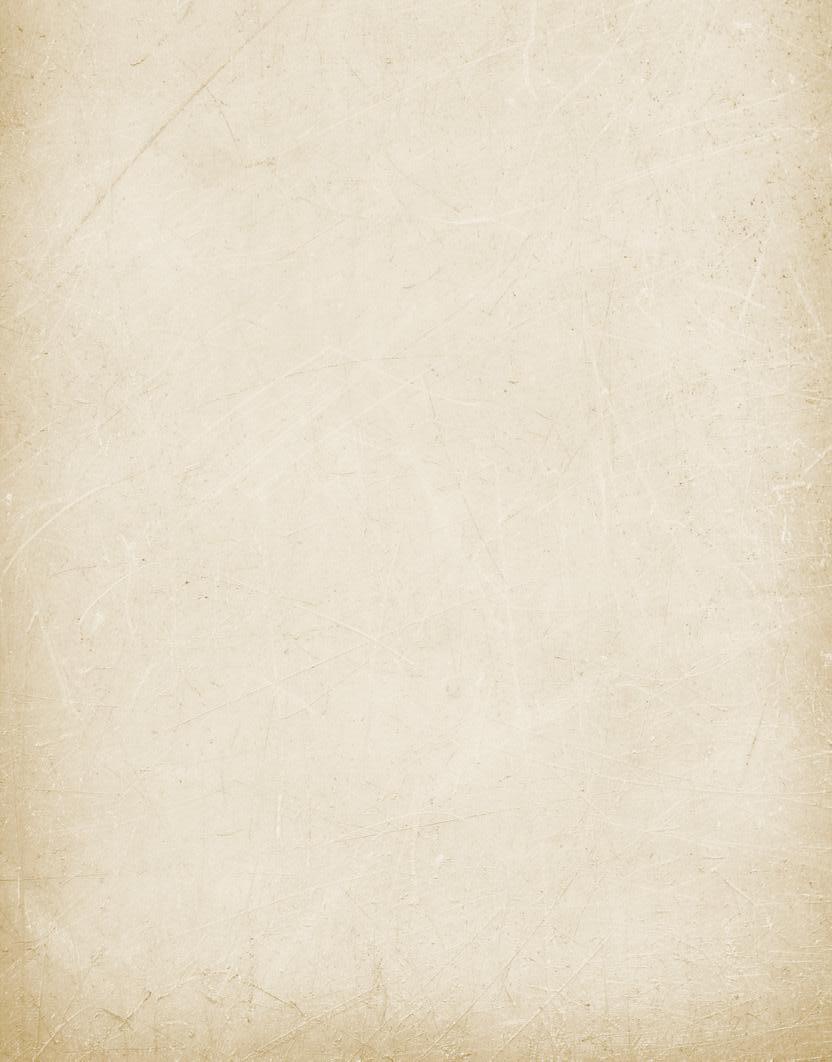

TavaqaraSviliseuli nusxac, Tavisi mxatvruli gaformebiT, levan dadianis dakveTiT Seqmnil nimuSebsa Tu gviani Sua saukuneebis qarTul xelnawer memkvidreobaSi gansakuTrebul adgils ikavebs. „vefxistyaosnis~ miniaturebis mxatvrulgamomsaxvelobiTi xerxebi da garkveul SemTxvevebSi Sinaarsic ki, Sua saukuneebis da axal, realizmis elementebSeparuli droebis mijnis anarekls warmoadgens. Sua saukuneebis rainduli eposi mxatvrisTvis, TiTqos, Cveulebriv ambad qceula, romlis epizodebsac dawvrilebiT gadmoscems sxvadasxva suraT-xatiT: xelnawerSi erTmaneTs mosdevs teqstis sakvanZo ambebis amsaxveli, brZolis Tu yofiTi scenebi Tanmxlebi mxedruli, ganmartebiTi xasiaTis warwerebiT: TinaTinis gamefeba, ucxo moymis naxva, avTandilis anderZi, tarielis

of Odishi. It was during this time, at the court of Levan II Dadiani and at his commission, that he transcribed the poem in 1646:

“Glory to the perfect God, helper and protector of all. I began this Knight in the Panther’s Skin on the thirteenth of June, and completed it on the eighteenth of August, in the year 334 of the chorinicon. If anything is missing, may no one curse me – I was writing in captivity. There are twenty-nine gatherings inside, totaling two hundred and twelve folios.” Scholarly opinion is divided over the authorship of the manuscript’s illustrations: some consider Mamuka Tavakarashvili himself to be the artist, while others disagree with this view.

The illustrated opening of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” can be seen as a visual preface to the above-quoted colophon. Alongside the manuscript’s origin story, it also conveys the personal traits of its patron and the worldview of the period. In the very first miniature, at the top of the composition, frontally and in an Eastern style, Levan Dadiani is shown kneeling between two attendants. In the lower register, two other kneeling figures face each other in three-quarter view. According to scholars, the poet Shota Rustaveli is depicted dictating the text to the scribe Mamuka Tavakarashvili, who holds an open scroll on which the words “This tale…” can be read. Another portrait of Mamuka Tavakarashvili appears at the end of the manuscript, this time seated at a desk in the act of writing. It is noteworthy that the scribe’s depiction (especially depicted twice), as well as his presentation alongside the patron, is an unusual occurrence in medieval Georgian miniature painting and underscores both the significance of the commissioner and the elevated status of the scribe.

Particularly notable is the image of Levan II Dadiani, whose portrait features – an elongated oval face, long straight nose, and closely set narrow eyes – evoke comparisons with depictions of princes in wall paintings and repoussé works (such as frescoes in the churches of Tsalenjikha, Khobi, and Kortsheli, or repoussé icons of the Prophets of Kortsheli and St. George of Ilori – all from the 17th century). The inclusion of his own portrait on the very first page of the manuscript, as well as the illustration of the manuscript’s creation story, served as Levan Dadiani’s emphatic declaration of how significant the copying and embellishment of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” was to him. This act fully aligned with his broader cultural and political agenda. As ruler of the Principality of Odishi, Levan Dadiani stands among those outstanding historical figures whose active cultural engagement and broad range of interests left behind a rich artistic legacy. His court hosted artists and craftsmen invited from various countries, along with merchants and missionaries, all of whom enjoyed his strong support. The art and culture of late medieval Georgia would be hard to imagine without the goldsmithing, mural painting, and other works created under his patronage.

The Tavakarashvili Manuscript, with its artistic embellishments, holds a special place among Levan Dadiani’s commissioned

da avTandilis Sexvedra, tarielis brZola lom-vefxTan, qajeTis cixis brZola da sxv. poemis epizodebTan erTad, gansakuTrebiT, sagulisxmo iseTi ambebis ilustrirebaa, rogoric nestan-darejanisa da tarielis gardacvaleba da maTi datirebaa, rac cnobilia, rom poemis Semdgom, e.w. xalxur danamatebs warmoadgenda. am scenaSive Cndeba welszeviT moSiSvlebul motiralTa jgufi, romelTac xeli TmaSi wauvliaT an TavSi icemen. saintereso da erTgvarad ucnauri moCans „vefxistyaosanSi~ am uCveulo scenis gamoCena. am mxriv sagulisxmo cnoba Cndeba 1633-1649 wlebSi samegreloSi mcxovrebi TeatinelTa ordenis misioneri beris, arqanjelo lambertis „samegrelos aRweraSi“, saidanac Cans rom kolxeTSi micvalebulTa datirebis imdroindeli wesis Sesabamisad, procesis erT-erT nawils WirisufalTa wels zemoT gaSiSvleba da micvalebulis datireba warmoadgenda. am scenis, „vefxistyaosnis~ epizodebsa da mis dasuraTebaSi SeRweva im axali droebis mkafio niSani iyo, romelic TandaTan scildeboda Sua saukuneebis msoflmxedvelobas da realobisken swrafvis ufro da ufro mZafr survils avlenda.

TavaqaraSviliseuli nusxis `vefxistyaosnis~ mxatvrobas e.w. xalxuri nakadis da, erTi SexedviT, aRmosavluri xelovnebis elferic dahkravs, rasac ukve xsenebul yofiT elementebTan da modasTan erTad, mxatvrul-gamomsaxvelobiTi saSualebebic qmnis. miuxedavad imisa, rom mxatvari SesaZloa Cveni drois mnaxvelis TvalisTvis Cveul, saTanado profesiul ganswavlulobas iyo moklebuli, simartiviT, „gauwafaobiT~ da koloritis Tu xazis ostaturi SepirispirebiT, araCveulebrivad gamomsaxveli personaJebis, siuJetebis da zogadad, miniaturebis sruliad TviTmyofad mxatvrul saxes qmnis. kompoziciebi simetriulia, figurebi da samoqmedo garemo Tanabarzomierad ganawilebuli, ise, rom maTi mimoxilvisas mnaxvelis Tvali erTianad aRiqvams mocemuli ambis sakvanZo moments. figurebis Tu kompoziciis Semadgeneli sxva nawilebis konturi odnav mouxeSo, muqi yavisferi, moSavo xaziT isazRvreba, romelsac akvareliseburi vardisfris, mewamulis, oqris, mwvanis, lurjis da wiTlis SeTanxmebiT miRebuli sisadave avsebs. gamosaxulebebi sruliad sibrtyobrivia da dinamiurobis STabeWdilebas kompoziciebSi figuraTa ganlageba, maTi da garemos urTierTmimarTeba qmnis _ kompoziciebis SemomsazRvreli CarCodan gamosuli Tu SigniT „SeWrili~ figurebi, moqmedi pirebisa da arqiteqturis Tu sxva yofiTi elementebis urTierTganlageba, perspeqtivis sibrtyobrivi aRqma da sxv.

works and within the broader tradition of late medieval Georgian manuscript heritage. The stylistic and expressive devices used in “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” miniatures – and in some cases even their content – reflect a transitional moment between the medieval and early modern periods, enriched with emerging realist elements. The medieval knightly epic seems to have become familiar ground for the artist, who vividly illustrates its episodes through numerous narrative images: scenes of Tinatin’s coronation, the encounter with the foreign knight, Avtandil’s testament, the meeting of Tariel and Avtandil, Tariel’s battle with the lion-panther, the siege of the fortress of Kajeti, and others, all accompanied by explanatory captions in the mkhedruli script.

Alongside the poem’s canonical episodes, especially noteworthy is the illustration of scenes such as the deaths of Nestan-Darejan and Tariel and their mourning – events known to originate not from the poem itself but from the so-called folk additions that followed. In this very scene, a group of mourners appears bare-chested from the waist up, pulling at their hair or striking their heads in grief. The appearance of such an unusual scene in ”The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” is both curious and thought-provoking. In this regard, a compelling clue emerges in A Description of Samegrelo by Archangelo Lamberti, a Theatine missionary monk who lived in Samegrelo between 1633 and 1649. From this account, we learn that in Colchis, one part of traditional mourning rituals involved mourners baring their upper bodies while weeping for the deceased. The insertion of such a scene into the illustrated episodes of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” thus signals a clear departure from a medieval worldview and reveals a growing desire for realistic representation – a sign of the changing times.

The artwork in the Tavakarashvili manuscript of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” bears the aesthetic trace of what is known as the “folk stream,” with a distinct overtone of Eastern visual tradition. This impression is created not only by the domestic details and stylistic choices already mentioned but also by the expressive and compositional techniques employed by the artist. Though the painter may not have possessed the formal training expected by modern standards, the simplicity and so-called “naivety” of the miniatures, combined with a masterful handling of color contrasts and line work, result in strikingly expressive characters and scenes. These elements give the miniatures a unique and self-contained artistic identity. The compositions are symmetrical, the figures and narrative environments evenly balanced, allowing the viewer’s gaze to take in the entire central moment of the depicted story at once. The contours of the figures and other compositional elements are outlined with slightly rough, dark brown or nearly black lines, which are softened and enriched by a harmonious palette of watercolor-like pinks, purples, golds, greens, blues, and reds. The images are entirely flat, and the illusion of movement is conveyed through the spatial arrangement of figures and their relationship to the environment – characters

tipaJebi, maTi samoqmedo garemo _ anturaJi, arqiteqtura, yofiTi nivTebi, varcxniloba da samosi, qarTuli da sparsuli elementebis „Tanacxovrebis~ amsaxvelia. yovelive es swored rom imdroindeli yofis ilustracias warmoadgens, romelSic ukve mZlavradaa SemoWrili da damkvidrebuli aRmosavluri kulturuli gavlena _ ara mxolod im drois artefaqtebi, aramed istoriuli wyaroebic (mag., vaxuSti bagrationi „aRwera samefosa saqarTvelosa~ da sxv.). amasTan mimarTebiT, kvlav, arqanjelo lambertis cnobaa yuradsaRebi, romlis Tanaxmadac misi Tanamedrove qarTveli qalebi aRmosavlur yaidaze ixatavdnen pirisaxes. warbebs Savi saRebaviT iRebavdnen, ise rom yurebamde Cadiodnen da cxvirTanac gaerTianebuli hqondaT. Sesabamisad, safiqrebelia, rom mxatvrobis, erTi SexedviT, aRmosavluri mxatvruli saxe sparsuli xelovnebis gavleniT Seqmnili ki ara, aramed, ufro imdroindeli yofis amsaxveli unda iyos. mxatvrisTvis `vefxistyaosnis~ gmirebi mis Tanamedrove garemoSi arsebuli Cveulebrivi adamianebi iyvnen, visac yoveldRe xedavda da ara miuwvdomeli, Sua saukuneebis rainduli elferiT Semosili personaJebi.

Zveli saqarTvelosken mibrunebasa da Tanadrouli epoqis tendenciebis gaziarebaSic ganmsazRvreli, epoqis msoflaRqmaa. qarTuli kulturisTvis XVI-XVII saukuneebi, erTgvarad, xelaxali `aRorZinebis~ xanad moiazreba. sparsul-osmalur politikur Tu kulturul eqspansiasTan dasapirispireblad, samefo-samTavroebad daSlili saqarTvelos erovnuli da sulieri gamoRviZebis epoqad qceuli droebisas Senebis da gamSvenebis iseTi mZafri survili Cndeba, romlis Sedegebic kontrastuladac ki gamoiyureba imxanad ganuwyveteli brZolebisa da ekonomikur-socialuri mdgomareobis fonze. igeba da ixateba eklesiebi, iqmneba Weduri, ferweruli xatebi da xelnawerebi. im drois saxviTi xelovneba mxatvrul mimarTulebaTa mravalferovnebiTaa gamorCeuli: e.w. xalxur nakadTan erTad, arsebobas ganagrZobs post-bizantiuri stili da ukve Semosulia iranuli kulturis gavlenebi. am yovelives Tan erTvis maSin, ukve, CvenSi SesamCnevad Semosuli evropuli xelovnebisadmi swrafvac. am mravalferovan da kulturul gzajvaredinze TavaqaraSviliseuli „vefxistyaosnis“ mxatvroba, Tavisi individualuri maxasiaTeblebiT, ufro sainteresod Cndeba da mnaxvels saTayvanebeli eposis dasuraTebasTan erTad, XVII saukunis Sua xanis saqarTvelos kulturas, yofas da saxviTi xelovnebis tradiciebs aziarebs.

or objects that cross the framing border of the composition, or appear embedded within it; the juxtaposition of protagonists and architectural or domestic elements; the use of flat perspective, and more.

The characters themselves, as well as their surroundings –architecture, furnishings, hairstyles, and costumes – reflect a coexistence of Georgian and Persian elements. All of these details serve as visual documentation of contemporary life, in which Eastern cultural influence had already taken deep root. This was not only evident in material artifacts of the time but also in historical accounts – for example, Vakhushti Bagrationi’s Description of the Kingdom of Georgia, among others. A relevant detail again comes from Archangelo Lamberti, who observed that contemporary Georgian women would paint their faces in an Eastern manner: their eyebrows were dyed with black pigment, extended to the ears, and joined at the bridge of the nose. Thus, it is more likely that the seemingly “Eastern” style of the miniatures is not directly a product of Persian artistic influence, but rather a reflection of the lived reality of the time. For the painter, the heroes of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” were not distant, idealized figures clad in medieval chivalric splendor, but ordinary people from their contemporary surroundings – people he saw every day.

This dual movement – toward the heritage of old Georgia and the simultaneous embrace of contemporary trends – was driven by the prevailing worldview of the time. The 16th–17th centuries are often seen as a kind of cultural “Renaissance” for Georgia. In an era when the fragmented kingdoms and principalities of Georgia faced political and cultural expansionism from Persia and the Ottoman Empire, a powerful desire emerged for national and spiritual renewal. This desire to build and embellish was especially vivid, even amidst near-constant warfare and economic hardship. Churches were built and painted, ruined or damaged monuments restored, and elaborate metalwork, icons, paintings, and manuscripts were created. The visual arts of this period are remarkable for their stylistic diversity: alongside the so-called folk stream, the post-Byzantine tradition persisted, while Iranian influences had clearly made their mark. Added to this mix was an increasingly noticeable attraction to European art. Within this rich and culturally crossroads-laden context, the illustration of “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin” in the Tavakarashvili manuscript stands out even more for its individuality. Alongside the visual narration of Georgia’s beloved national epic, it also offers a window into the material culture, worldview, and artistic traditions of 17th-century Georgia.

nugeSa gagniZe

NUGESHA GAGNIDZ

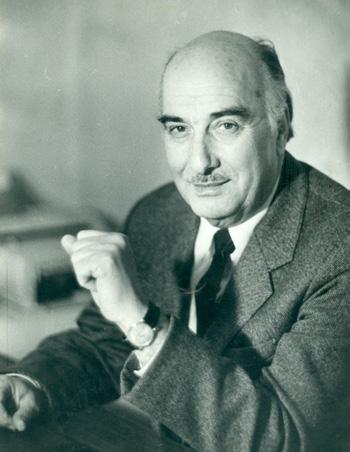

wlebi gadis grigol robaqiZis teqstebisa da masze dawerili kritikuli werilebis ZiebaSi. bevric vipove, magram vici, rom sadRac, romeliRac arqivisa Tu biblioTekis jadosnur sacavebSi, kidev iqneba saintereso masalebi, romlebic naTels mohfenen orjer emigrirebuli mwerlis cxovrebisa da Semoqmedebis burusiT mocul ambebs.

Years go by in my search for texts by Grigol Robakidze and critical writings about him. I have found many, yet I know that somewhere – in the enchanted repositories of some archive or library – there are still undiscovered materials that could shed light on the life and work of this twice-exiled writer, enshrouded in mystery.

Sometimes I feel Grigol is already someone close to me, a family member, a part of my life. But then, a newly discovered note can suddenly remind me that I still haven’t fully come to know this strange gentleman. His manuscripts, publications, or fragments of literary texts often surface at the most unexpected times and in the most unexpected places.

This time, I want to tell you about a short letter I came across by chance in the Kutaisi Central Archive.

The archive truly feels like a magical realm. You never know what you’ll stumble upon. You wander through epochs, past centuries, unearthing forgotten stories of statesmen and artists, along with impressive, eloquent photographs. Sometimes, the allure of these old tales is so strong that you forget the very reason you came to this treasury. This is exactly what happened on a sunny day in September 2024. That morning, I began researching the family histories of the Margvelashvilis and Khechinashvilis – ancestors of writer Givi Margvelashvili. These remarkable individuals endured so much pain and hardship during the first quarter of the 20th century. There is so much we must know – and yet don’t. And then, completely by chance, I came upon a letter by Grigol Robakidze in the archival files of Thaddeus Margvelashvili – the father of historian Tite Margvelashvili and grandfather of postmodernist writer Givi Margvelashvili. The card is dated March 9, 1911.

We have only scant material about Grigol Robakidze’s activities in 1911–1912. The writer himself rarely references this period in his autobiographical writings. My own research suggests that during these years, Robakidze was primarily giving lectures and engaging in journalistic work. His public talks – on literature, philosophy, and political issues – captivated audiences. In fact, in 1911, Akaki Tsereteli attended one of Robakidze’s lectures and was so inspired he declared, “The tree of our nationality is not yet withered.”

Enchanted by the young man, the national poet soon published an article in the newspaper “Thema”, writing, “The lecturer revealed himself to me as the first swallow, herald of spring. Now I see that, after a long winter, spring is coming to Georgian intellectual life as

xandaxan vfiqrob, rom grigoli ukve Cemi axlobelia, ojaxis wevria, Cemi cxovrebis nawilia. magram, uceb, erTma axladaRmoCenilma patara baraTma SeiZleba magrZnobinos, rom bolomde mainc ver gavicani es ucnauri batoni. Tanac iseT dros da iseT adgilas aRmoCndeba misi xelnaweri, publikacia an mxatvruli teqstis fragmenti, sul rom ar eli.

amjerad giambobT erT patara werilze, romelic SemTxveviT vipove quTaisis centralur arqivSi. marTlac rom zRapruli samyaroa arqivSi. ras ar waawydebi aq. daabijeb epoqebSi, gardasul saukuneebSi, poulob usamarTlod miviwyebul eriskacTa da xelovanTa Sesaxeb informaciebs, STambeWdav da mravlismTqmel fotoebs. ise gagitacebs xandaxan Zveli istoriebi, is mTavari SeiZleba kidec migaviwydes, risTvisac am ganZTsacavs ewvie. ase iyo 2024 wlis seqtembris erT mzian dRes. dilaadrian Sevudeqi givi margvelaSvilis winaprebis, margvelaSvilebisa da xeCinaSvilebis ojaxebis istoriebis Ziebas. ramdeni ram gadautaniaT, ramdeni

well. I say with joy, soaring to the seventh heaven: blessed be the future!”

The letter by Grigol Robakidze that I found in Kutaisi’s Central Archive is important above all because it contributes to a deeper understanding of the writer’s biography – particularly his activities during 1911–1912 – and helps uncover some previously unknown or little-known facts. In 1910, Robakidze traveled to Tartu (known as Yuryev) to continue his studies in law. The letter, dated March 9, 1911, was sent from Tartu and begins as follows:

“Brother Kita,

Forgive me for writing such a prosaic letter. But what can a person do when reality betrays him?”

I believe the addressee is Kita Abashidze. It was thanks to him, along with Nino Nikoladze and Giorgi Maiashvili (Zdanovich), that Grigol Robakidze was able to study at the universities of Leipzig, Tartu, and Kazan. A gifted but financially struggling student, Robakidze had a difficult time making ends meet far from home. This is evident from his many letters to Giorgi Maiashvili, which were discovered and studied by Mr. Mikheil Nikoleishvili. They date from

tkivili ganucdiaT am didebul adamianebs meoce saukunis pirvel meoTxedSi. ramdeni ram unda vicodeT da ar viciT! da, ai, uceb Tadeoz margvelaSvilis, istorikos tite margvelaSvilis mamisa da postmodernisti mwerlis givi margvelaSvilis babuis, saarqivo masalebSi sruliad SemTxveviT vipove grigol robaqiZis patara baraTi, dawerili 1911 wlis 9 marts.

1911-1912 wlebSi grigol robaqiZis saqmianobis Sesaxeb masalebi mcire odenobiT mogvepoveba. Tavadac ar wers mwerali avtobiografiul teqstebSi am periodis Sesaxeb. Cemma kvleva-Ziebebma ki im daskvnamde mimiyvana, rom aRniSnul wlebSi igi ZiriTadad leqciebs kiTxulobs da publicistur saqmianobas eweva. msmenelebs aRafrTovanebs misi gasaocari sajaro moxsenebebi literaturis, filosofiisa da politikis problemur sakiTxebze.

1911 wels mousmenia akaki wereTelsac grigol robaqiZisTvis da imedi gasCenia _ „Cveni erovnebis xe jer ar gamxmarao“. misiT moxiblul saxalxo mgosans gazeT `TemSi~ maleve gamouqveynebia statia, romelSic xazgasmiT aRuniSnavs: „leqtorma iCina Tavi Cems TvalSi, rogorc pirvelma mercxalma, gazafxulis maxarobelma. axla ki

1910–1914. In one of them, Robakidze describes the monotony and dullness of life in Tartu, as well as his dissatisfaction with the courses and uninteresting subjects. The same mood is present in the letter to Kita Abashidze, in which Robakidze asks him to send 50 rubles to pay university fees:

“I sent you a telegram last week: 50 rubles (for university fees) – please send it. So far, I’ve received nothing except the monthly allowance. I hope you will send it upon receiving this letter. Giorgi agrees…”

The “Giorgi” mentioned is likely Giorgi Maiashvili uradze (Zdanovich), a Polish-born publicist, economist, and revolutionary populist who was a member of the Social-Revolutionary Organization of All Russia and a loyal patron of Georgian students. He also chaired the Council of Manganese Industrialists in Chiatura. Besides the university fees, Robakidze has another request – he wants to return to Georgia. The reason: his family situation.

“I ask you for one more thing, and I hope you will grant it. I must return to Georgia in mid-April. The main reason: my family has been left without care after the death of my father.”

This final sentence is underlined by the writer. There is little

vxedav, rom qarTvel inteligenciasac udgeba xangrZlivi zamTris Semdeg gazafxuli da mec meSvide camde afrenili, vambob sixaruliT: kurTxeul iyos momavali!“

quTaisis centralur arqivSi, Cven mier aRmoCenili grigol robaqiZis werili, pirvel rigSi, imiTaa mniSvnelovani, rom gvexmareba mwerlis biografiis, kerZod ki, 1911-1912 wlebSi misi saqmianobis safuZvlianad Sesaswavlad da zogierTi ucnobi an naklebad cnobili faqtis dasadgenad.

1910 wels grigol robaqiZe tartuSi (iurievi) gaemgzavra, raTa gaegrZelebina iurisprudenciis Seswavla. 1911 wlis 9 martiT daTariRebuli baraTi swored tartudanaa gamogzavnili da igi ase iwyeba:

„Zmao kita!

mapatie amdeni prozauli werili. ra hqnas adamianma, Tu sinamdvile orgulobs!“ vfiqrob, werilis adresati kita abaSiZea. swored

biographical information available about Robakidze’s father, the deacon Tite Robakidze. The writer himself says very little about him in his autobiographical essays. In this sense too, the letter to Kita Abashidze is significant. It seems the father’s death was doubly difficult for the young man, so far from home. Robakidze clearly wants to return to Georgia to support his family, but he doesn’t have the funds. So he writes:

“On April 7–8, the Council will send me 50 rubles, but that won’t be enough for travel. I ask you to send me the full year’s allowance: that is, 130 rubles (excluding the 50 rubles for the university). This amount includes April’s allowance too. In short: upon receiving this letter, please send 50 rubles, and at the beginning of April another 130 rubles. That will complete my annual support.”

Based on materials from the Estonian Historical Archive, we can say that Robakidze did manage to return to Georgia. The archive preserves a letter he sent from Borjomi to the rector of Tartu University, dated August 24, 1912, in which he writes that he is suffering from malaria. Attached to the letter is a medical certificate from Dr. Gomarteli prescribing bed rest until October 10. This is the only known document that confirms Robakidze ever contracted

misi, nino nikolaZisa da giorgi maiaSvilis (zdanoviCi) xelSewyobiT swavlobda grigol robaqiZe laifcigis, tartusa da yazanis universitetebSi. niWier, magram xelmokle students uWirda Tavis gatana samSoblodan Sors, rasac adasturebs misi araerTi werili giorgi maiaSvilisadmi, romlebic moiZia da gamoikvlia batonma mixeil nikoleiSvilma. isini 1910-14 wlebSia dawerili. erT-erT maTganSi tartus erTferovani da mosawyeni cxovrebis Sesaxeb wers grigol robaqiZe, rasac emateba ukmayofileba saswavlo procesiTa da uintereso sagnebiT. es ganwyoba igrZnoba kita abaSiZisadmi miweril baraTSic, romelSic robaqiZe mas universitetSi Sesatan 50 maneTs sTxovs. „dReis swors depeSiT mogmarTe: 50 man (univ. Sesatani) gamomigzavneTqo. dRemde araferi momsvlia, garda Tviurisa. imedia, am werilis miRebisTanave momawvdi. giorgi Tanaxmaa...~ giorgi, albaT, giorgi maiaSvilia (zdanoviCi), polonuri warmomavlobis cnobili publicisti, ekonomisti,

malaria – an illness that was widespread in the lowlands of Colchis at the time.

Despite financial difficulties, family burdens, and illness, Robakidze completed the summer semester in 1913 and received a certificate from the Faculty of Law at Tartu University on March 22, 1914, confirming he had studied there for eight semesters. That same year, he enrolled at Kazan University, but did not pass the state exams – World War I had broken out, and he was forced to return home.

The one-page letter to Kita Abashidze contains yet another valuable detail. Robakidze writes:

“I’ll give lectures. The first lecture will be on Friedrich Nietzsche; the second on the idea of Hamlet. My article about Vazha-Pshavela will be published in [the newspaper name is illegible] in an upcoming issue. Other writings will be published as well.”

Between 1911 and 1913, Robakidze was very active as a publicist. During this time, he published works such as “A Necessary Clarification (in response to D. Kasradze’s article),” “On Friedrich Nietzsche,” “The Spirit and Creativity of the Nation,” “Rustaveli the Artist: A Sketch,” “Art and Reality,” “Oscar Wilde,” “Leaves, II: The Integrity of the Nation,” “Letters” and more – in The People’s Newspaper and Golden Ram.

At the bottom of the letter to Kita Abashidze, there’s a noteworthy postscript:

“P.S. Potskhverashvili asks me to pass this on: While others receive their funds from the Council at the beginning of the month, I get mine at the end, and so I lose a month’s money.”

This note shows that Robakidze was concerned about other struggling students as well. It is known that he often used money earned from his public lectures to assist fellow Georgian students abroad. At the same time, it must be noted that Robakidze himself almost never enjoyed material prosperity. Even in emigration, he often depended on influential friends. I recall one letter he wrote to Bruno Goetz in 1938:

“My financial hardship is plunging me into despair. My economic situation is catastrophic. What can I do? Money loves neither you nor me. A lady friend promised last summer to send me funds in secret – did you receive it? Perhaps she forgot. When I see her, I’ll remind her.” “I’ve completed a mythic portrait of a certain figure. Once it’s published, I hope to make a lot of money.”

The “mythic portrait” referred to is the literary portrayal of Hitler in an essay, which was soon followed by a portrait of Mussolini. After these fateful publications, Robakidze’s financial condition improved briefly. But that reprieve was short-lived, followed by an even darker chapter. At one point, living in exile in Switzerland, he didn’t even have a typewriter to finish his writings – works that would go unpublished, some of which are now lost…

The letter I found in Thaddeus Margvelashvili’s personal file gives us hope that somewhere, scattered across the world, more of Robakidze’s texts may still be found – pieces that will help us complete the portrait of the writer.

revolucioner-xalxosani, „sruliad ruseTis socialurrevoluciuri organizaciis wevri“, WiaTuris Savi qvis mrewvelTa sabWos ucvleli Tavmjdomare, qarTvel studentTa erTguli mfarveli.

garda universitetSi Sesatani Tanxisa, kidev aqvs grigols saTxovari _ samSobloSi unda wasvla. wasvlis mizezi ki misi ojaxuri mdgomareobaa. „gTxov kidev erTs rames, da, imedia, amasac amisruleb. aprilis Sua ricxvebSi saqarTveloSi unda wamovide. mTavari mizezi _ ojaxis upatronobaa mamis Cemis gardacvalebis Semdgom“. es bolo winadadeba xazgsamulia mwerlis mier.

grigol robaqiZis mamis, medaviTne tite robaqiZis Sesaxebac ar moipoveba sakmarisi masala. mweralic Zalian cotas wers masze avtobiografiul eseebSi. amdenad, kita abaSiZisadmi gagzavnili baraTi am mxrivacaa sagulisxmo. rogorc Cans, mamis gardacvaleba samSoblos moSorebuli axalgazrdisTvis ormagad mZimea. werilidan irkveva, rom mas Zalian unda saqarTveloSi Camovides da ojaxs miexmaros, magram ara aqvs gzis fuli. amitom kita abaSiZes sTxovs: „aprilis 7-8-s sabWodan momiva 50 man., magram wamosasvlelad es ar meyofa. gTxov gamomigzavno ama wlis sargo sruliad: ese igi, 130 man (zemoxsenebul 50 m. universitetisaTvis garda rCeba sul 130 man.): am fulSi aprilis fulic Sedis. erTi sityviT, am werilis miRebis dros gamomigzavne 50 man. da pirvel ricxvebSi aprilisa 130 man., da sruliad miRebuli meqneba am wlis fuli“.

estoneTis istoriuli arqivis masalebze dayrdnobiT SeiZleba vTqvaT, rom grigol robaqiZem moaxerxa saqarTeloSi Camosvla. am arqivSia daculi misi 1912 wlis 24 agvistos werili, romelsac igi tartus universitetis reqtors borjomidan swers da atyobinebs, rom malariiTaa avad. am gancxadebas Tan erTvis eqim gomarTelis mier Sedgenili samedicino daskvna, romlis Tanaxmad, mas 10 oqtombramde woliTi reJimi aqvs. aqve isic unda aRvniSno, rom es erTaderTi dokumentia, romelic mwerlis malariiT daavadebis Sesaxeb gvamcnobs. malaria ki imxanad kolxeTis dablobSi sakmaod gavrcelebuli yofila.

miuxedavad finansuri problemebisa, ojaxuri mdgomareobisa da avadmyofobisa, grigol robaqiZem 1913 wels daasrula zafxulis semestri, xolo 1914 wlis 22 marts tartus universitetis iuridiuli fakultetisgan miiRo momwmoba, rom man am universitetSi rva semestri iswavla. 1914 wels mweralma yazanis universitets miaSura, Tumca saxelmwifo gamocdebi aqac ar Caubarebia, radgan pirveli msofilio omi daiwyo da iZulebuli gaxda samSobloSi dabrunebuliyo.

kita abaSiZisadmi miwerili erTgverdiani baraTi kidev erT sayuradRebo informacias gvawvdis. grigol

robaqiZe wers: „leqciebs wavikiTxav. pirveli leqcia iqneba: fr. nicSe; meore: idea hamletisa. Cemi werili vaJa-fSavelas Sesaxeb gamova [gazeTis saxelwodeba ar ikiTxeba. n.g.] axlobel nomerSi. garda amisa daibeWdeba sxva werilebic“.

1911-13 wlebSi grigol robaqiZe aqtiur publicistur saqmianobas eweva. swored am periodSi daibeWda misi naSromebi: „iZulebiTi ganmarteba (d. kasraZis werilis gamo)“, „fridrix nicSes gamo“, „eris suli da Semoqmedeba“, „rusTaveli xelovani: eskizi“, „xelovneba da sinamdvile“, „oskar uaild“, „foTlebi, 2, eris mTlianoba“, „baraTebi“ da sxv. `saxalxo gazeTsa~ da `oqros verZSi~. grigol robaqiZis werils kita abaSiZisadmi Zalze sagulisxmo minaweri aqvs: „P.S. focxveraSvili mTxovs gadmogce: im dros, roca sxvebis fuls Tvis Tavs ugzavnis sabWo, me Tvis bolos migzavnis da Tvis fuli mekargebao.“ minaweri cxadyofs, rom mwerali sxva xelmokle studentebzec zrunavs. cnobilia, rom grigol robaqiZe Tavisi sajaro leqciebidan Semosuli TanxebiTac araerTxel daxmarebia finansur gaWirvebaSi myof Tanamemamuleebs sazRvargareT. Tumca aqve isic xazgasmiT unda aRvniSno, rom Tavad mwerals TiTqmis arasodes hqonia materialuri keTildReoba. emigraciis periodSic metwilad gavleniani megobrebis imedad iyo. maxsendeba erTi werili bruno gecisadmi miwerili 1938 wels: „materialuri siduxWire sasowarkveTilebaSi magdebs. Cemi ekonomikuri mdgomareoba amJamad katastrofulia. ra SeiZleba gavakeTo? fuls arc Sen „uyvarxar“ da arc me. erTi Cemi megobari qalbatoni gasul zafxuls dampirda, rom saidumlod gadmomiricxavda Tanxas. miiRe Sen is? SesaZloa daaviwyda kidec. roca Sevxvdebi, usaTuod Sevaxseneb.

me davasrule erTi pirovnebis miTiuri portreti. roca daibeWdeba, imedia, bevr fuls aviReb“.

„miTiuri portreti“ hitlerisadmi miZRvl eseSi warmodgenili fiureris mxatvruli saxea, romelsac male musolinis portreti mohyva. am sabediswero eseebis gamoqveynebis Semdeg, namdvilad gaumjobesda cota xniT grigol robaqiZis finansuri mdgomareoba. es ki Zalze xanmokle periodi iyo, rasac SemdgomSi kidev ufro mZime etapi mohyva. SveicariaSi emigrirebul mwerals erTxanad sabeWdi manqanac ki ar hqonda Tavisi nawarmoebebi rom daesrulebina. es is teqstebia, romelTac aRar ubeWdavdnen da romelTa nawilic dakargulia...

Tadeoz margvelaSvilis pirad saqmeSi aRmoCenili grigol robaqiZis baraTi aCens imeds, rom odesme moiZebneba msoflios sxvadasxva kuTxeSi mimofantuli misi teqstebi, romlebic dagvexmareba mwerlis portretis dasrulebaSi.

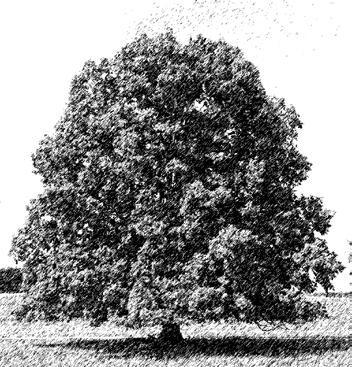

am statiaSi gvsurs giamboT salocavad miCneul xeebze, ufro sworad ki saqarTveloSi sakralurad Seracxul xeTagan erT-erTze _ balze. 2017 wlis zafxulSi savele eTnografiuli muSaobis dros Sevxvdi araCveulebriv qalbatons _ sof. zubis mkvidr Jenia (Rvata) CakvetaZes, romelmac gadmogvca: „dedaCemisgan gamigonia, rom moxucebi blis win muxlze daemxobodnen da xelebaweulebi xmamaRla ilocebodnen: „baloo! baloo!~. arc wminda xeebia ucnobi qarTuli eTnografiuli sinamdvilisaTvis da blis xesTan dakavSirebuli akrZalvebsac vxvdebiT Sesabamis literaturaSi, magram es fraza da blis ZirSi xelebapyrobili mlocvelis „balo! balo!..“ ireklavda raRac imdenad Soreuls, rom misi logikuri axsna Zneli Canda da, rogorc Cans, imdenad mniSvnelovans didi xnis manZilze, rom misi mkrTali xsovna informaciuli epoqis adamianebsac gadmogvwvda. leCxumsa da svaneTSi fafala gardafxaZe-qiqoZis mier Sekrebili eTnografiuli cnobebidan, romelic Tsu istoriisa da eTnologiis institutis arqivSia daculi, vgebulobT, rom svaneTSi did xuTSabaTs qalebi gamTeniisas, „Citis azvramde~, midiodnen tyeSi da ubrad agrovebdnen mware blis qerqsa da foTlebs samkurnalo balaxebTan da askilTan erTad. gamxmari da wvril-wvrilad dakepili es nazavi „gaTvalulis~ wamlad miiCneoda, asmevdnen kidec da Sav qsovilSi samkuTxedad gamokruls amuletadac atarebdnen avi Tvalisagan dasacavad. leCxumSi blis tots „sacavs~ eZaxdnen da mas kaloze aTavsebdnen. saamisod didi xuTSabaTs mamakaci tyeSi moWrida mware blis tots da kalos SuagulSi daasobda, zemodan ki askiliT jvars gaukeTebda. avi Tvalisagan adamianisa Tu yanis mcvelis funqciaminiWebuli bali rom warsulSi namdvilad salocavi xe iyo, yvelaze kargad samegrelos eTnografiulma masalam Semogvinaxa. alio qobalias „megrul leqsikonSi~ mravali Zvirfasi eTnografiuli cnobaa daculi, maT Soris CvenTvis saintereso sakiTxzec. bals megrulad „buli~ hqvia, „buliS ja~, anu blis xe ki asea ganmartebuli: „salocavi, sakraluri xea, romlis ZirSic sruldeba araerTi warmarTul-qristianuli rituali, imarxeba salocavi qvevrebi...~ rogorc vxedavT, blis qveS mlocveli leCxumeli im saerTo wess asrulebda, romelsac fesvebi uTuod Soreul warsulSi unda hqondes. samegreloSic iseve eridebodnen blis SeSad gamoyenebas, rogorc leCxumSi. gansxvavebiT leCxumisagan, samegreloSi mas saxlis win ar rgavdnen. rogorc alio qobalia aRniSnavs, „blis adgili upiratesad ezos ukana yurea, Tvalmuxvedreli, mofarebuli adgili“. bals mcvelad aRiqvamdnen _ rogorc adamianis, aseve marCenali cxovelisa da yanis mcveladac. salocav qvevrebsac, safiqralia, amitom aTavsebdnen mis ZirSi. amitomac sulac araa gasakviri, rom uwin Turme samegreloSi micvalebulis samudamo gansasvenebelsac blisgan Tlidnen _ mas andobdnen Zvirfasi micvalebulis

In this article, we would like to tell you about trees considered sacred for prayer – in particular, one of the sacral trees in Georgia: the cherry tree. In the summer of 2017, during field ethnographic research, I met an extraordinary woman – Zhenia (Ghvata) Chakvetadze, a resident of the village of Zubi – who shared the following: “I’ve heard from my mother that the elders would kneel before the cherry tree, raise their hands, and pray aloud: ‘Balo! Balo!’” (Cherry, cherry!”) Sacred trees are not unknown in the ethnographic reality of Georgia, and prohibitions associated with cherry trees can be found in the relevant literature. However, this phrase – and the image of a supplicant with raised hands beneath a cherry tree – echoes something so distant that a logical explanation is difficult, and it seems to reflect something so deeplysignificant that even in the information age, a faint memory of it still reaches us.

From ethnographic data collected by Papala GardapkhadzeKikodze in Lechkhumi and Svaneti – now stored in the archive of the Institute of History and Ethnology at Tbilisi State University – we learn that, in Svaneti, on Maundy Thursday, women would go into the forest before dawn, “before the birds start chirping,” and collect the bark and leaves of the wild cherry along with other medicinal herbs and dog rose. This dried and finely chopped mixture was considered a remedy for the “evil eye” – it was both ingested and worn as an amulet sewn into black fabric in a triangular shape, to protect against harm. In Lechkhumi, the cherry branch was called a “protector” and placed on the threshing floor. For this, on Maundy Thursday, a man would go into the forest, cut a branch of the wild cherry, and place it in the center of the threshing floor, making a cross from a dog rose atop it.

The cherry tree, regarded as a protector of both people and crops, was undeniably considered a sacred tree in the past, a truth best preserved in ethnographic materials from Samegrelo. Alio Kobalia’s Mingrelian Dictionary includes many precious ethnographic notes, among them ones relevant to our topic.

In Mingrelian language, the cherry tree is called “Buli”, and the phrase “Bulish Ja” – meaning “cherry tree” – is defined as follows: “A sacred, sacral tree beneath which numerous pagan-Christian rituals are performed, where votive Kvevris (Georgian earthenware pots) are buried…” As we can see, the Lechkhumian supplicants praying under the cherry tree were following a common rule that must undoubtedly have its roots in the distant past. In Samegrelo, just as in Lechkhumi, people avoided using cherry wood as fuel. Unlike Lechkhumi, however, in Samegrelo, the tree was not planted in front of the house. As Alio Kobalia notes: “The proper place for a cherry tree is at the back of the yard, out of sight, in a hidden spot.”

The cherry tree was seen as a guardian – not only of humans but also of livestock and crops. This may be why votive Kvevris were buried at its base. It is also no surprise, then, that in the past, coffins were carved from cherry wood in Samegrelo – people entrusted the bodies of their beloved deceased to it. The choice of cherry for a final resting place was likely shaped by the long-held belief in its

sxeuls. blis xisagan samudamo gansasveneblis gamoTlac igivenairad SeiZleba avxsnaT: didi xnis ganmavlobaSi ganmtkicebulma rwmenam blis RvTaebrivi bunebis Sesaxeb ganapiroba misi arCeva samudamo gansasveneblad, Torem warmoudegeneli iqneboda, rom sakubove xe yanisa da kalos mcvelad qceuliyo da uxvmosavlianobis Tavisebur „garantad“. piriqiT ki, swored rom SesaZlebelia. gana eklesiis mimdebared sasaflaos mowyobaSi igive survili ar gamosWvivis, rom uzenaesi Zalis mfarvelobas mivandoT CveTvis Zvirfas adamianTa samudamo gansasvenebeli? maS, bals mcvelis funqcia hqonia da muxldaCoqili mlocvelic hyolia, magram riT unda yofiliyo ganpirobebuli adamianis es mosazreba? mkiTxvelma SeiZleba ikiTxos, ratom gamakvirva balma, roca kargad viciT, rom Cvens dromde moatana rwmenam salocavi muxisa Tu cacxvis Sesaxeb? amisaTvis, Zalzed mokled gadavavloT Tvali im mizezebs, rac safuZvlad unda dasdeboda salocavi xeebisadmi rwmenas. ama Tu im xisaTvis zeburnebrivi, RvTaebrivi Zalis miwerasa da mis salocavad gaxdas msoflios yvela kuTxeSi vxvdebiT. igi nawilia rwmena-warmodgenaTa im mTliani sistemisa, romelsac mecnierebi animizmad moixsenieben. am sityviT aRniSnaven religiuri azrovnebis ganviTarebis sawyis safexurs, rodesac adamianisaTvis mis irgvliv arsebuli samyaro gasulierebulia. uxsovari droidan xes Tayvans scemdnen sxvadasxva geografiul arealSi mcxovrebi da gansxvavebuli kulturis matarebeli xalxebi. anTropologi frezeri naSromSi, „oqros rto“, aRniSnavs, rom germanelTa uZveles taZrebs tyeebi warmoadgenda. druidebi muxas eTayvanebodnen da sityva, romliTac isini taZars aRniSnavdnen niSnavs koroms. wminda tye, wminda koromi arsebobda ufsalaSi _ Sveicariis uZveles religiur centrSi da iq mdgari xeebi RvTaebrivad iTvleboda. wminda xeebsa da tyeebs Tayvans scemdnen slavebi. litvelebi aRmerTebdnen muxas da sxva did xeebs da Tvlidnen, rom nebismieri, vinc tots moatexda wminda xes, sastikad daisjeboda. indielTa Soris danaSaulad iTvleboda giganturi xeebis moWra da asakovani xalxis azriT, maTze Tavsdatexili ubedurebis mizezi is iyo, rom xalxi pativiT aRar epyroba xes. vanikas tomis xalxi aRmosavleT afrikaSi ki Tvlda, rom „qoqosis palmis moWra dedis mkvlelobas utoldeba“. afrikis dasavleTSi, senegalidan nigeriamde, pativiscemiT epyrobian bambis xeebs, swiraven mas msxverpls da akrZaluli iyo bambis xis totis motexva. magaliTebis moyvana mravlad SeiZleba, Tumca anTropologiaSi evoluciuri skolis erT-erTi fuZemdeblis, j. frezeris mier moxmobili es CamonaTvalic sakmarisia imisaTvis, rom warmovidginoT ramdenad gavrcelebuli da sazogado movlena iyo kacobriobis istoriaSi xis gaRmerTeba da misi Tayvniscema. am sakiTxis kvlevas CvenSic araerTi samecniero kvleva eZRvneba da dainteresebuli mkiTxveli SeZlebs siRrmiseulad gaecnos sakiTxs qarTvel mkvlevarTa

divine nature. Otherwise, it would be unthinkable for a coffin tree to be associated with guarding harvests or threshing floors, or with ensuring abundant yield. And yet the opposite proves true. After all, isn’t the idea of placing cemeteries beside churches also a reflection of the desire to entrust our loved ones’ eternal rest to the protection of a supreme force?

So, the cherry tree had a protective function and was an object of kneeling prayer – but what underpinned this belief? A reader might wonder: why did the cherry tree surprise me, when we already know that the belief in sacred oaks and lindens has endured to this day? To answer this, let us briefly review the reasons that may have given rise to belief in sacred trees.

The attribution of supernatural or divine power to certain trees, and their transformation into prayer sites, is found in every corner of the world. It is part of a broader system of beliefs known among scientists as animism (from anima, meaning soul) – the earliest stage of religious thought, in which the surrounding world is perceived as spiritually animate. Since ancient times, trees have been venerated by people across vastly different geographies and cultures. Anthropologist James Frazer, in his seminal work “The Golden Bough”, notes that the earliest temples of the Germanic peoples were forests. The Druids revered the oak, and the word they used for “temple” meant “grove.” Sacred forests and groves existed in Uppsala, Sweden’s ancient religious center, where trees were considered divine. Slavs also worshiped sacredtrees and forests. Lithuanians revered the oak and other large trees, believing that anyone who broke a branch of a sacredtree would be harshly punished. Among Native Americans, cutting down giant trees was a crime, and elders believed that disasters befell people because they no longer respected the trees. In East Africa, the Vanika people believed that cutting a coconut palm was tantamount to murdering one’s mother. In West Africa, from Senegal to Nigeria, the cotton tree was revered – sacrifices were offered to it, and breaking its branches was forbidden.

Examples abound, but even the list provided by Frazer, one of the founders of the evolutionary school in anthropology, suffices to demonstrate how widespread and universally resonant the worship of trees has been throughout human history.

In Georgia, too, many scholarly studies have explored this topic. Readers interested in a deeper understanding can refer to works by Georgian scholars such as Vera Bardavelidze, Giorgi Chitaia, Sergi Makalatia, M. Chikovani, J. Rukhadze, N. Vachnadze, T. Gudushauri, T. Ochiauri, T. Tsagareishvili, N. Khazaradze, N. Abakelia, and others. Articles from the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Georgian and Russian periodicals also offer ample evidence for the existence of sacred trees in Georgia, though listing them all would take us too far afield. One thing is certain: sacred trees were widespread throughout Georgia. For instance:

The Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta was built on the site of a sacred oak. After King Mirian’s conversion to Christianity, the

naSromebSi. XIX saukunis meore naxevrisa da XX saukunis dasawyisis qarTul da rusul periodul presaSic didZali magaliTebia damadasturebeli salocavi xeebis arsebobisa da maTi CamoTvla Sors wagviyvanda. erTi ram ki dadasturebulad SegviZlia vTqvaT - salocavi xeebi gavrcelebuli iyo mTels saqarTveloSi. ase, magaliTad: wminda xis, ufro zustad ki, wminda muxis adgilzea agebulia mcxeTis sveticxovli. mirian mefis gaqristianebis Semdeg wminda muxa mouWriaT da mis adgilas Tavdapirveli xis eklesia auSenebiaT. wminda tyeebi aqvs xats aRmosavleT saqarTvelos mTianeTSi, saidanac warmoudgenelia nafotis gamotanac ki. zemo aWaraSi, iq, sadac Zvelad eklesiebi mdgara, am saukunis 20-ian wlebSi maTi kvali wminda tyeebiT aRiniSneboda, romelTa xelis xlebas veravin bedavda. egnate gabliani aRniSnavs svaneTSi salocavi xeebis arsebobas da aRwers mulaxis sazogadoebaSi, sofel zardlaSis dasavleTiT mdebare saeklesio tyes, romelsac saxelad „xvamli“-s uwodeben. misi azriT „es tye Sewiruli unda iyos leCxumSi xomlis mTaze arsebul wminda giorgis eklesiisadmi“.

leCxumSi araerT sofelSi minaxavs uzarmazari cacxvis xeebi, romlebsac dRemde salocavad miiCnevs xalxi da romlebic Tvals itaceben Tavisi silamaziTa da gansakuTrebuli zomebiT.

istoriul kolxeTSic, romelic axla Cveni administraciuli sazRvris miRmaa darCenili, igive suraTia. „es bavSvi xis totze Camokidebuli cekvavs~ _ ase ityvian bavSvis gadaWarbebul sicelqeze Turme lazebi. am sityvebSi Semonaxulia maTi Soreuli winaprebis tradicia. rogorc 2015 wels gamocemul wignSi „lazeTi da lazebi TurqeTis gamocemebSi“ vkiTxulobT: „gazafxulze, miwis damuSavebis, TevzWerisaTvis zRvaSi gasvlis da sxva mniSvnelovani sakiTxebis win lazebi oxvameebze cdilobdnen RmerTebisagan nebarTvis miRebas. oxvameebis centri iyo didi muxis xe, mWkoni, romelic xalxis rwmeniT, maT avisagan icavda. aq Sesrulebul locvebs oxvamus uwodebdnen. oxvamu mravalferovan locvebs moicavda da grZeldeboda cekvis TanxlebiT. „amis mizani iyo, rom caSi mcxovrebi RmerTebi miwaze CamoeyvanaT da maTTan SeerTebuliyvnen. xalxi xelCakidebuli wres Sekravda, xelebs cisken aRapyrobda da ambobda sityvebs, romelTa Sinaarsi dReisaTvis dakargulia. RmerTebis miwaze Camosvlas specialuri niWis mqone adamianebi grZnobdnen, sxvani ki zustad asrulebdnen am adamians naTqvamsa da moZraobas. roca misteriisgan aRtkinebuli xalxi miiRebda cnobas, rom RmrTebi miwaze Camovidnen, sixarulisgan gons kargavdnen da tansacmelsac ixevdnen. xes Camoekidebodnen da ase gamoxatavdnen grZnobebs emociurad. am uZvelesi misteriis kvalia im sityvebSi, romelsac lazebi sicelqisgan aRtacebul bavSvs etyvian „ham bere Tamli moklimeri ixoronams”. mTasa Tu barSi gavrcelebul am rwmenas erTi saerTo aqvs - salocavad didi da STambeWdavi xeebia SerCeuli.

oak was felled, and the first wooden church was constructed on its spot.

In the highlands of eastern Georgia, sacred groves surround shrines, and removing even a twig from them is unthinkable.

In Upper Adjara, where churches once stood, their traces were marked in the 1920s by sacred forests – untouchable by human hands.

E. Gabliani mentions sacred trees in Svaneti and describes the “Khvalmi” forest west of the village of Zardlash in the Mulakhi community. In his view, “this forest must have been a votive offering to the Church of St. George located on Khomli Mountain in Lechkhumi.”

In many villages of Lechkhumi, I have seen enormous linden trees still regarded as sacred today, remarkable for their beauty and colossal size.

The same picture emerges in historical Colchis, now beyond Georgia’s current administrative borders.

“When a child is wildly mischievous, the Laz people say: ‘This child is dancing on a tree branch’”. This phrase preserves an ancient tradition of their ancestors. According to the 2015 book “Lazeti and the Laz in Turkish Sources”, in the spring before sowing, going out fishing to sea, or other important events, the Laz would seek divine permission at sites called okhvamebi. At the center of these gatherings stood a large oak tree, mchkoni, believed to protect them from harm. The prayers performed there were called okhvamu – a complex ritual accompanied by dancing. The aim was to summon the gods from the sky and unite with them. People would form circles, raise their hands to the sky, and chant words themeanings of which are now lost. Those with a special gift would feel the gods’ descent; others would mimic their movements. Once it was revealed that the gods had arrived, people would fall into ecstasy, tear off their clothes, and cling to the tree, expressing their joy emotionally. This ancient mystery play is echoed in the Laz expression for a wild child: “Ham Bere Tamli Moklimeri Ikhoronams.”

Whether in the mountains or lowlands, this belief shares a common thread: sacred trees were always large and impressive – usually oaks or lindens, or, in the eastern Georgian highlands, poplars and ash trees. As we have noted, belief in sacred trees stretches back thousands of years, rooted in the early stages of religious consciousness. Of course, for modern people, it can be difficult to comprehend the logic behind such a belief that endured for millennia and has reached us only as a reflection. To understand this, we must radically shift our perception of the world around us. Imagine a time when there is no heat or light source except the sun – no electricity, no coal stove, and you don’t even know how to light a fire. Whether your body survives the freezing winter nights depends entirely on whether you reach dawn and whether you can draw enough warmth from the person beside you or from your breath-warmed shelter. “Fire?” the reader may ask – and here we come to the answer. Fire first entered

ufro xSirad es muxaa, an cacxvi, aRmosavleT saqarTvelos mTianeTSi ki alva da ifanic. Cven ukve aRvniSneT, rom salocavi xeebisadmi rwmena aTaswleulebs iTvlis da adamianis religiuri azrovnebis ganviTarebis adreuli xanidan iRebs saTaves. raRa Tqma unda, rom Tanamedrove samyaros SvilebisaTvis umeteswilad Znelad asaxsnelia, ra logika unda dasdeboda safuZvlad am mosazrebas, romelmac aTaswleulebi iarseba da Cvens dromde anareklis saxiT moaRwia. amis asaxsnelad ki jer Cvens irgvliv garemomcveli samyaros Sesaxeb warmodgena unda SevcvaloT. aba, warmovidginoT, rom ar arsebobs gaTbobisa da ganaTebis aranairi sxva wyaro, garda mzisa. ar arsebobs eleqtroenergia, arc qvanaxSirs Rumeli SegiZliaT daanToT da saerTodac, danTebac ki ar iciT raimesi. SeinarCunebs Tu ara Tqveni sxeuli zamTris civ RameebSi sasicocxlod aucilebel temperaturas, mxolod imazea damokidebuli, miaRwevT Tu ara ganTiadamde, roca caze mze gamoCndeba da manamde gagaTbobT Tu ara sakmarisad gverdiT myofis siTbo da Tqveni sunTqviT damTbari samyofi. cecxlio? _ ikiTxavs mkiTxveli da ai, pasuxamdec mivediT. cecxli pirvelad adamianTa samyofSi daaxloebiT 300-400 aTasi wlis win Cndeba, manamde ki milionze meti welia ucecxlo yofis. im 300 aTasi wlis Semdegac cecxlis irgvliv mxolod adamianTa nawili cxovrobs. Cveni goneba albaT srulad verasodes gaiazrebs im yofis adamianTa mopovebuli cecxlis sixaruls da Camqrali cecxlis eldasa da mwuxarebas, Tumca darwmunebiT SegviZlia vTqvaT, rom cecxli niSnavda sicocxles da misi gaqroba ki mTeli ojaxisaTvis sasikvdilo safrTxe iyo. didi xeebisadmi krZalva da Tayvaniscemac, savaraudod, jer kidev im periodidan iRebs saTaves, roca sibneliT, siciviT da yoveli mxridan momdinare safrTxiT SeZrwunebuli adamianis goneba da gancda caze diliT amosul mzes misi „bavSvuri~ logikiT RmerTad aRiqvamda. Tu Cven erTi wamiT gaviTavisebT mis yofas da misi TvalebiT davinaxavT zecidan mexad wamosul cecxls, TvalnaTeli gaxdeba, rogor Seqmna pirvelyofilma logikam kavSiri: mze (zeca) _ cecxli da xe. sxvaTa Soris, kavkasiam Cinebulad Semoinaxa imdroindeli krZalva cidan wamosuli cecxlisadmi. sayovelTaod cnobilia, rom Cerqezebi mexdacemuls gansakuTrebuli pativiT krZalavdnen da gamorCeulad Tayvans scemdnen namexar xesa Tu arsebas. cota gagvigrZelda sityva da unda iTqvas, rom es sakiTxi marTlac Zalzed vrceli da sainteresoa. mas Semdeg rac gagacaniT mosazreba, ra unda yofiliyo didi xeebisadmi krZalvis safuZveli, isev Cvensave SekiTxvas davubrundeT: riT gamoarCia Cvenma Soreulma winaparma bali? igi arc alvasaviT aSoltilia, arc cacxviviT STambeWdavi da warmosadegi, arc muxasaviT mtkice da didebuli ieris. maS riT aRibeWda igi adamianis gonebaSi iseTad, rom megrulma enam Semogvinaxa sityva „bula“ _ balze mlocveli. vis da ratom unda eloca balze? gana ra gadaulaxav saWiroebas

human dwellings some 300–400 thousand years ago. Before that, humans lived in a fireless state for over a million years. Even after fire became known, it remained accessible only to a part of humanity. We may never fully grasp the joy of those who first secured fire, nor their terror when it was lost – but we can say for certain: fire meant life, and its extinction posed a mortal threat to the entire family. The reverence and veneration for great trees likely originates from a time when the human mind and emotion – shaken by darkness, cold, and danger coming from all directions – perceived the sun rising in the morning sky as a god through its “childlike” logic. If we momentarily place ourselves in that existence and see the fire descending from the sky through such eyes, it becomes clear how primitive logic forged a connection: the sun (sky) – fire – and tree. By the way, the Caucasus region has preserved the ancient reverence for fire that descends from the sky remarkably well. It is widely known that the Circassians would bury a person struck by lightning with special honor and show exceptional reverence toward any tree or being that had been struck.

This discussion has grown lengthy, but it truly is a vast and fascinating subject. Now that we have examined the basis for reverence toward great trees, let us return to our original question: why did our distant ancestors single out the cherry? It is neither towering like the poplar, nor grand like the linden, nor sturdy like the oak. Why then did it etch itself into the human imagination so deeply that the Mingrelian language preserved the word “Bula” – “one who prays at the cherry”? Who, and why, would pray to a tree that gives sweet fruit?

You may already have thought of the answer: the cherry is the first fruit of the season. Today, with supermarkets stocked yearround with fruit from all continents, it’s easy to forget the joy, even just a few decades ago, of hearing: “The cherries have come into season!” Now, let us return once again to that distant time – before agriculture, before granaries – and imagine the sheer joy and relief of encountering the season’s first fruit. The cherry, herald of life’s renewal, may well have been worthy of prayer. Now let us go back once again to that distant time when humans Did not yet know how to cultivate the land and could not store the harvest gathered in autumn as provisions for the winter. After all, throughout the entire existence of humankind, the era of foraging lasted the longest. Not only in hunter-gatherer societies – in fact, even in ethnographic records collected as recently as the 1930s, the month of June was described as follows: “Kvakhirekia is the month – there is no more of the old, and the new has not yet arrived.”Can you imagine what kind of diet people had without agriculture or stored provisions for the winter? How many pairs of hungry eyes would look at a returning hunter who came back empty-handed? Let us imagine how these people waited for that springtime moment when fruits would begin to ripen and

uqrobda adamians tkbili nayofis momcemi es xe? pasuxi SesaZloa ukve Tqvenc mogividaT azrad _ bali xom pirvelmwifea. dResdReobiT, roca hipermarketebi weliwadis nebismier dros savsea sxvadasxva kontinentidan Camotanili xiliT da adamians aRar ukvirs ianvarSi marwyvis monatreba, gavixsenoT, rogori sasixarulo iyo sulac ramdenime aTeuli wlis win roca gavigonebdiT: _ bali Semosula! axla isev ukan davbrundeT im Soreul droSi, roca adamianma jer kidev ar icoda miwis damuSaveba da ar SeeZlo Semodgomaze moweuli sazrdo zamTris maragad Seenaxa. kacobriobis arsebobis manZilze xom yvelaze xangrZlivad swored Semgroveblobis xana gagrZelda. ara Tu monadireSemgrovebel sazogadoebaSi, sul axlaxan, meoce saukunis 30ian wlebSi Sekrebil eTnografiul cnobebSi asea aRwerili ivnisis Tve: „kvaxirekia Tvea, Zveli aRar aris, axali jer ar Semosula“. warmogidgeniaT, rogori racioni unda hqonodaT adamianebs miwaTmoqmedebisa da zamTris maragis gareSe? xelmocarulad dabrunebul monadires ramdeni wyvili mSieri Tvali Sexedavda? warmovidginoT, rogor elodnen es adamianebi gazafxulis im dros, roca xilis mwifoba daiwyeboda da xeebze sitkboTi savse nayofi gamoCndeboda. es xom SimSilis dasasruls niSnavda, weliwadis axali drois _ mwifobis dawyebas. niSnavda imas, rom momdevno warmatebul nadirobamde im momlodine mSieri TvalebiT maqcerals sulis mosaTqmeli aqve _ xeebze eguleboda: tkbili, gemrieli, Zalisa da Ronis swrafad momcemi nayofi. vfiqrob, swored monadire-Semgrovebeli sazogadoebis yofaSi arsebobda is garemoebebi, romlisTvisac weliwadis axali, SimSilisagan Tavisufali sezonis dawyeba pirvelmwife xils unda emcno. bali ki swored mcire aziisa da samxreT kavkasiis endemuri mcenarea da logikuria vifiqroT, rom CvenSi is iqneboda aseTi „macne“. misi SeTvaleba iqneboda weliwadis axali, tkbili periodis dawyebis niSani da Taviseburi kalendaruli movlena, romelic or nawilad hyofda weliwads _ mwifobisa da aramwifoebis xanad, es ki rogorc ramdenjerme aRvniSneT udaod sasicocxlod mniSvnelovani iqneboda Semgrovebeli sazogadoebisaTvis. mas Semdeg aTobiT aTasma welma gaiara. adamianma iswavla miwis damuSaveba, jer rqiT, Semdeg kidev ufro da ufro srulyofili xerxebiT. miwaTmoqmedebam erT adgilze daafuZna adamiani da gamravlebisa da ganviTarebis bevrad didi SesaZleblobebi misca. magram imdenad xangrZlivi iyo is epoqa, roca SeTvaluli xili weliwadis axal dros da TviTgadarCenis met SesaZleblobas niSnavda, rom Cvens miwa-wyalze amis macne xe _ bali _ eTnografiul yofas SemorCa rogorc salocavi, mcveli da mosafrTxeli. statiis dasawyisSi naxsenebi „balo! baloo!“ ki aTaswleulebgamovlili am didi molodinis da imedis anarekli yofila.

the sweet, nourishing bounty would appear on the trees. That moment marked the end of hunger, the beginning of a new season – of ripeness. It meant that until the next successful hunt, those hungry, waiting eyes could find solace nearby – in the trees, where sweet, delicious, and strength-giving fruits hung in abundance.

I believe it was precisely in the life of hunter-gatherer societies that the circumstances emerged under which the beginning of a new, hunger-free season would be announced by the first ripened fruit. The cherry, being an endemic plant of Asia Minor and the South Caucasus, would logically have served as such a “herald” in our region. Its appearance would have signaled the start of a new, sweet season of the year – a kind of calendrical event that divided the year into two parts: the season of ripeness and the season of unripe scarcity. And as noted before, this division would have been of vital importance to a foraging society.

Since then, tens of thousands of years have passed. Humans learned how to cultivate the land – first with a horn, and then with increasingly advanced tools. Agriculture rooted people in one place and offered far greater possibilities for growth and development. But the era in which the sighting of the first fruit marked a new time of year and a better chance of survival lasted so long that the tree bearing this message – the cherry – remained in our land and culture as sacred, to be protected and revered. And the words mentioned at the beginning of this article – “Balo! Baloo!” (“Cherry! Cherry!”) – turn out to be the echo of this ancient, millennia-old anticipation and hope.

paata jaSi PAATA JASHI

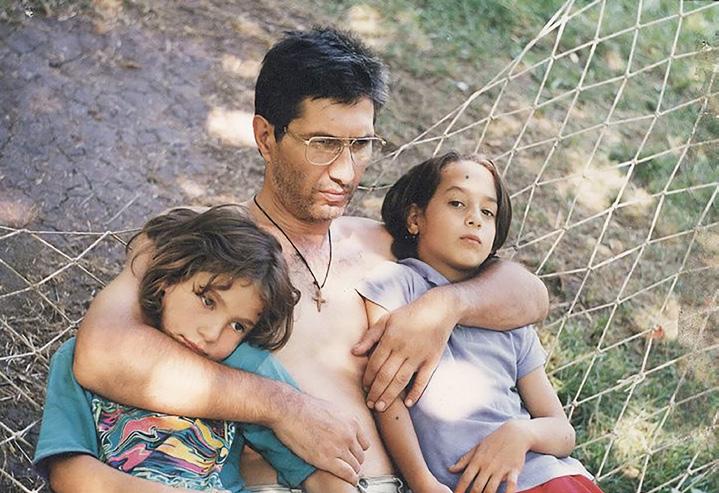

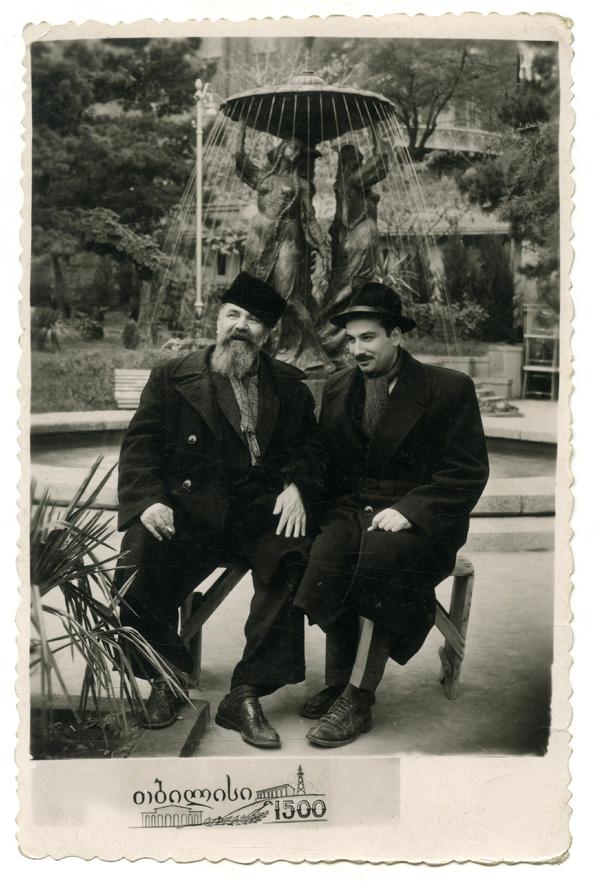

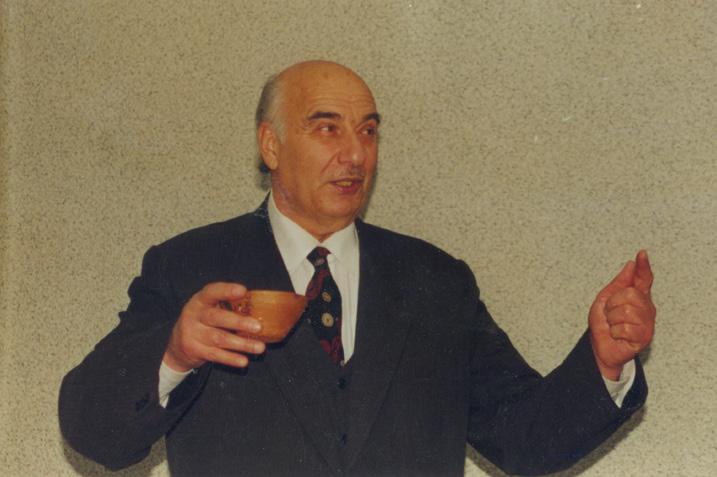

20-21 wlis Tu iqneboda pirvelad rom Sevxvdi, 1981 wels, qobuleTSi, fiWvnarSi, sadac aWaris samecnierokvleviTi institutis arqeologebis jgufi muSaobda. samuSao velidan axlad dabrunebulebi viyaviT da Cveni jgufis usaTnoesi wevris, maiko boWoriSvilis dabadebis dRis aRniSvnisaTvis vemzadebodiT, rodesac `versalis~ (ase eZaxdnen xumrobiT eqspediciis wevrebi Zvel Tavlas, sadac rekonstruqciis Semdeg, arqeologiuri baza unda ganTavsebuliyo) „karibWes~ ori ymawvili moadga. pirvelma (igi yovelTvis yvelgan pirveli iyo), gamorCeuli habitusiT, umalve miiqcia Cveni yuradReba: maRali, saTvaliani, sufTad gaparsuli, dinji da mozomili qceviT msaxiob indiana jonss hgavda. `vin aris meTqi?~ _ vikiTxe. `guram gabiZaSvilia, universitetis studenti, leqsebi uyvars, kargi biWia,~ _ miTxra kukuSam (erekle astaxiSvilma). leqsebis siyvaruli ki iseTi daxasiaTeba iyo, romelic, umal, keTilgangawyobda...

I first met him when he was about twenty or twenty-one. It was 1981 in Kobuleti, in the Pichvnari area, where a group of archaeologists from the Adjara Scientific Research Institute was working. We had just returned from the field and were preparing to celebrate the birthday of our group’s most virtuous member, Maiko Bochhorishvili, when two young men approached the “gates” of the Versaille (as we jokingly called the old barn, which, after reconstruction, was to serve as an archaeological base for the expedition). One of them immediately drew attention – tall, bespectacled, clean-shaven, with calm measured movements, he looked like an actor’s version of Indiana Jones. I asked, “Who is this?” “That’s Guram Gabidzashvili, a university student, he loves poetry, he’s a good guy,” Kukusha (Erekle Astakhishvili) replied. And his love of poetry was described in such a way that would instantly won you over.

Later, at the table, taking advantage of the toastmaster’s privilege, I unexpectedly addressed this still-unknown young man aloud: “Guram! Please, read us a poem.” Silence fell; all eyes turned to him. Guram looked at me, paused for a few seconds – probably weighing the sincerity of my request – and then, adjusting his glasses with his index finger, began – “Over the steppe, past Karbada Where partridges arise from the kurgans…” Do you know how he read it? It wasn’t an artistic recital, nor theatrical performance – it was a mystique born of naked emotion and passion, pain felt truthfully, desire filled with hope. We didn’t just passively watch this mystique – we became part of it. He carried us up to the heavens and flew us from the kurgans of Kabardian to the ridges of Ksani and Aragvi. We froze with him at the sight of an unknown woman’s beauty; with him we “raised the dust on all the roads around,” with him we “broke the locks on the gates of Mtskheta,” and “smashed temples, with their great candles, down!” With him we fought the man in morion, with him we lay decapitated on rose petals, hoping for a new encounter. The poem ended, a moment of silence followed – no other expression of agreement or praise, for Guram had made us not passive listeners, but participants in his mystery.

It’s hard to say which aspect predominated in Guram’s actions – his emotional world or his rational part? In both cases his actions stood out with astonishing artistry. Artistry was his defining trait generally. But this artistry was spontaneous and natural, not contrived. Guram was an extraordinary storyteller. When his performance emerged, even the most trivial matter he recounted – adding something new

Semdeg ki, ukve sufrasTan, visargeble ra Tamadis privilegiiT, yvelasTvis moulodnelad, jer kidev ucnob kacs xmamaRla mivmarTe _ guram! gTxov, rame leqsi wagvikiTxe-Tqo. _ siCume Camovarda, yvelas mzera guramisken iyo miqceuli. guramma gamomxeda, ramdenime wamiani pauza... albaT, gonebaSi afasebda Cemi Txovnis gulwrfelobas, Semdeg saCvenebeli TiTiT saTvale cxvirze gaiswora da daiwyo, magram ra daiwyo _ „yorRanebidan gnoli afrinda, yabardos veli gadaiara...“ rogor kiTxulobda iciT? es ar iyo mxatvruli deklamacia, arc Teatraluri artistizmi, es iyo SiSveli grZnobiT da vnebiT, tkivilis marTali gancdiT, imediT aRsavse surviliT Seqmnili misteria. da Cven am misteriis pasiuri mayurebelni ki ara, misi monawile gagvxada. agvitaca zecas da mogvafrina yabardos yorRanebidan qsnisa da aragvis xodabunebi. Rvino nasmevze, masTan erTad gavxeldiT ucxo qalis simSvenieris xilviT, masTan erTad „avamtvrianeT gzebi tiali“, masTan erTad „mcxeTas vumtvrie(T) saketurebi“ da „vlewe(T) taZrebi kelaptriani“, masTan erTad SevebrZoleT muzaradian vaJkacs, masTan erTad TavgaCexilni, vardis furclobis Jams, axali paemanis imediT. damTavrda leqsi, wuTieri garindeba, araviTari taSi an mowonebis sxva gamoxatva,

each time, a refined humor – was worth listening to. He captured hearts, drew attention effortlessly. Being with Guram meant inhabiting a world he created, unreal but protective, peaceful, and full of beauty and love.

His favorite subject was “The First Garment” by Guram Dochanashvili. One day he invented a game of finding prototypes of characters from the city of beauty. We had such fun when we found prototypes for Celio, Julio, Conchettina’s aunt Ariadne, especially Duilio. We searched with sorrow and anger for Kamora’s characters, easily finding Marshal Betancourt and the court painter Grekrikio. Finding Michinio was more difficult. It was the early 1980s; the national liberation movement was just beginning. Freedom and independence were taboo subjects under the regime. Thus, city of beauty and the Kamora existed for us in reality – which was Tbilisi and Moscow – so we looked for prototypes there and found them easily. And as for Kanudos, it was a land of dreams, and we searched for its heroes in dreams. Guram’s theme was assigning names of the seven Kanudosians. One evening in Derchi, in the beautiful courtyard of Guram’s ancestral house among centuries-old walnut trees, we lounged in hammocks.We had just returned from Khvamli and were savoring the silence and the sky filled with stars. Suddenly, he said to me, “Patiko! So, can you name seven Kanudosians among our brotherhood? Who do you have in mind?” We began thinking

radgan Cven pasiuri msmeneli ki ara, am misteriis nawili gagvxada guramma.

Zneli saTqmelia romeli ufro, Warbobda guramis qmedebebSi _ grZnobiTi samyaro Tu racio? misi qmedebebi, orive SemTxvevaSi, gamoirCeoda, saocari artistizmiT. zogadad artistizmi misi damaxasiaTebeli buneba iyo. magram es artistizmi ar iyo xelovnurad dadgmuli _ Zalian uSualo da bunebrivi qmedeba iyo. gurami saocari mTxrobeli gaxldaT. ai, sad gamovlindeboda xolme, misi artistizmi. sruliad umniSvnelo ambavs ise moyveboda, Tanac, sxvadasxva dros, raRac axali momentebis damatebiT, daxvewili iumoriT, rom misi mosmena erT ramed Rirda... yvelgan sulis Camdgmeli, yuradRebis epicentrSi iyo. saocrad exerxeboda sazogadoebis monusxva, ayolieba da es yvelaferi bunebrivad, Zaldautaneblad gamosdioda. guramTan erTad Tu iyavi, ese igi, mis gamogonil irealur samyaroSi cxovrobdi da am samyaroSi Tavs daculad, komfortulad grZnobdi, mSvenierebis, simSvidis, siyvarulis sasufevelSi. doCanas „samoseli pirveli~ iyo misi sayvareli Tema. erT dRes raRac TamaSiviT moigona: lamaz-qalaqis gmirebis prototipebis moZebna. Zalian vxalisobdiT,

out loud. The title of Don Diego was awarded to Soso Bandzeladze without any debate. After a brief discussion, we chose five more Kanudosians. That left Manuel Costa and Zé Moreira. “So, who do you see as Manuel?” I asked. “I am,” he replied.

And indeed, he resembled Manuel Costa – cheerful, restless, spirited, loyal, a seeker of life’s hardships, someone who overcame them playfully, always inventing clever tricks, a true friend to friends and a steadfast fighter against foes. He had fought in Abkhazia, returned wounded, with his health shaken. I wouldn’t say he liked leadership or being in the spotlight, but taking the lead came to him naturally. He would always start the singing. I can still hear his call echoing in my ears – “Laleee~.” No one could match him in sharing joy or offering support during hard times. Friendship was the central theme of his life.

In “Khvamli’s Starry Multitude,” dedicated to Guram Gabidzashvili and Soso Bandzeladze, I once wrote: “Every Georgian bears within their heart at least one monument as an icon. Some are aware of it, and some are not – but the monument is there.” (Levan Gotua, Living Ancestors) For Guram Gabidzashvili, Khvamli was that monument. Khvamli was an inseparable part of his life. He had been enchanted by it since childhood, when, visiting his elder cousin Ioseb Bandzeladze (a scholar of architecture and architectural restorer) in the ancestral

rodesac cilios, julios, konCetinas mamida ariadnas da, gansakuTrebiT duilios prototopebs vpoulobdiT. sevdiTa da gabrazebiT veZebdiT kamoris gmirebs. marSal betankurs advilad mivageniT, agreTve, karis mxatvar grekrikios. Zalian gviWirda miCinios povna. es 80iani wlebis dasawyisia. erovnul-ganmaTavisuflebeli moZraoba axali dawyebulia. Tavisuflebaze da damoukideblobaze saubari tabudadebuli Temaa reJimis mier. amdenad lamaz-qalaqi da kamora CvenTvis realurad arsebobda, es Tbilisi da moskovi iyo, da amitomac prototipebs iq veZebdiT da adviladac vpoulobdiT, xolo, rac Seexeba, kanudoss es iyo ocnebis sofeli da Cvenc, mis gmirebs, ocnebaSi veZebdiT. guramis Tema iyo Svidi kanudoselis saxelis miniWeba. erT saRamos, derCSi, guramis mama-papiseuli saxlis did ulamazes ezoSi, aswlovani kaklis xeebs Soris gaWimul hamakebSi vnebivrobdiT. axali Camosulebi viyaviT xvamlidan da vtkbebodiT siCumiTa da varskvlavebiT moWedili ciT. ucbad meubneba _ patiko! aba Cvens saZmoSi Svid kanudosels Tu xedav da vis gulisxmob? _ daviwyeT xmamaRla fiqri... don diegoeba yovelgvari kamaTis