BEELDENTUIN KRÖLLERMÜLLER MUSEUM

FREEDOM WALK SCULPTURE GARDEN

KRÖLLER-MÜLLER MUSEUM

Museum in oorlogstijd en het ontstaan van de beeldentuin

In de middag van 15 april 1945 bevrijden Canadese soldaten het Kröller-Müller Museum. Drie weken later, op 5 mei, is in het gehele land de oorlog voorbij. Met het vertrek van de Duitse bezetter keert in Nederland na vijf jaar de vrijheid terug. Na de bevrijding wordt het museum heropend, de blik vooruit gericht. De patiënten uit het noodziekenhuis, dat in 1944 in de museumzalen was opgezet, maken plaats voor de collectie. Die was tijdens de oorlogsjaren in de schuilkelder ondergebracht. Bram Hammacher (1897-2002), die in 1948 als directeur wordt aangesteld, besluit zich te concentreren op de beeldhouwkunst. Al snel groeit de verzameling sculpturen aanzienlijk. Hammacher koestert de wens om met de collectie buiten de muren van het museumgebouw te treden en ‘zijn’ beelden in de vrije natuur te tonen. En zo opent in 1961 de beeldentuin.

Vrijheid in de naoorlogse sculptuur

Het tachtigjarig jubileum van de bevrijding nodigt uit het thema ‘vrijheid’ in de beeldentuin van het Kröller-Müller Museum te verkennen. De Tweede Wereldoorlog zelf is een onderwerp dat uiting krijgt

Museum in wartime and the origin of the sculpture garden

On the afternoon of 15 April 1945, Canadian soldiers liberate the KröllerMüller Museum. Three weeks later, on 5 May, the war is over throughout the country. With the departure of the German occupiers, freedom is restored in the Netherlands after five years. After the liberation, the museum is reopened with a view to the future. Patients from the emergency hospital, which had been set up in the museum rooms in 1944, make way for the collection. This had been housed in the bomb shelter during the war years. Bram Hammacher (1897–2002), who is appointed director in 1948, decides to concentrate on sculpture. Before long the collection of sculptures increases considerably. Hammacher harbours a desire to take the collection outside the walls of the museum building and display ‘his’ sculptures in the open air. And so in 1961 the sculpture garden is opened.

Freedom in post-war sculpture

The 80th anniversary of the liberation invites us to explore the theme of ‘freedom’ in the sculpture garden of the Kröller-Müller Museum. The Second World

in de naoorlogse sculptuur. Bij binnenkomst ben je bijvoorbeeld al langs Grote Auschwitz (1967) van Carel Visser [11], dat op het gazon voor de entree staat, gelopen. De kunstenaar verbeeldt de spoorlijnen en schoorstenen van het vernietigingskamp met een paar stalen balken. Het werk is robuust en roestig. In alle eenvoud draagt het de systematische, ontmenselijkende vernietiging treffend uit. De Holocaust is het uiterste gevolg van het in geding komen van onze vrijheid.

War itself is a subject expressed in post-war sculpture. For example, upon entering the museum, you have already walked past Large Auschwitz (1967) by Carel Visser [11], which stands on the lawn in front of the entrance. The artist depicts the railway lines and chimneys of the death camp with a few steel beams. The work is robust and rusty. In all its simplicity, it poignantly conveys the systematic, dehumanising destruction. The Holocaust is the ultimate consequence of compromising our freedom.

Juichende zusters van het noodhospitaal in Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller verwelkomen de eerste Canadese colonnes, 15 april 1945. Nurses from the emergency hospital in the Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller cheer the arrival of the first Canadian troops, 15 April 1945.

Het verbeelden van (on)vrijheid

De beelden die in deze wandeling centraal staan zijn allemaal gemaakt in de afgelopen honderd jaar. Ze geven op verschillende manieren vorm aan het abstracte begrip vrijheid. Vrijheid is meer dan de afwezigheid van oorlog. Het gaat om openheid, onafhankelijkheid, hoop, vernieuwing, wilskracht en levenslust. Van lichamelijke, geestelijke en persoonlijke tot ruimtelijke, politieke en maatschappelijke vrijheid: de werken die zijn uitgelicht tonen elk op hun eigen manier wat het betekent om (on)vrij te zijn of je (on)vrij te voelen.

Kunst als bevrijding

Veel van de kunstenaars die hier aan bod komen zoeken zelf binnen het kunstenaarschap naar vrijheid. Ze bevrijden zich van tradities en verleggen artistieke grenzen, benaderen vrijheid subtiel en gevoelsmatig of vormen trauma’s om tot iets nieuws. De gekozen materialen en technieken verschillen, de ideeën, thema’s en verhalen lopen enorm uiteen. Maar gemeenschappelijk lijkt dat het maken van kunst een middel is om vrij te zijn of te worden. En dat is in deze wandeling in alle facetten te ervaren.

Depicting (un)freedom

The sculptures featured in this walk were all made in the last hundred years. They give shape to the abstract concept of freedom in different ways. Freedom is more than just the absence of war. It is about openness, independence, hope, innovation, willpower and the lust for life. From physical, spiritual and personal to spatial, political and social freedom, the works highlighted here each show in their own way what it means to be or feel (un)free.

Art as liberation

Many of the artists featured here seek freedom within the artistic practice itself. They free themselves from traditions and push artistic boundaries, approach freedom subtly and sensitively or transform traumas into something new. The materials and techniques used differ and the ideas, themes and stories vary enormously. But what they all seem to have in common is that making art is a means of being or becoming free. And you can experience that in all its facets during this walk.

11 Carel Visser, Grote Auschwitz, 1967

10 UITGELICHTE BEELDEN IN DE BEELDENTUIN

10 FEATURED SCULPTURES IN THE SCULPTURE GARDEN

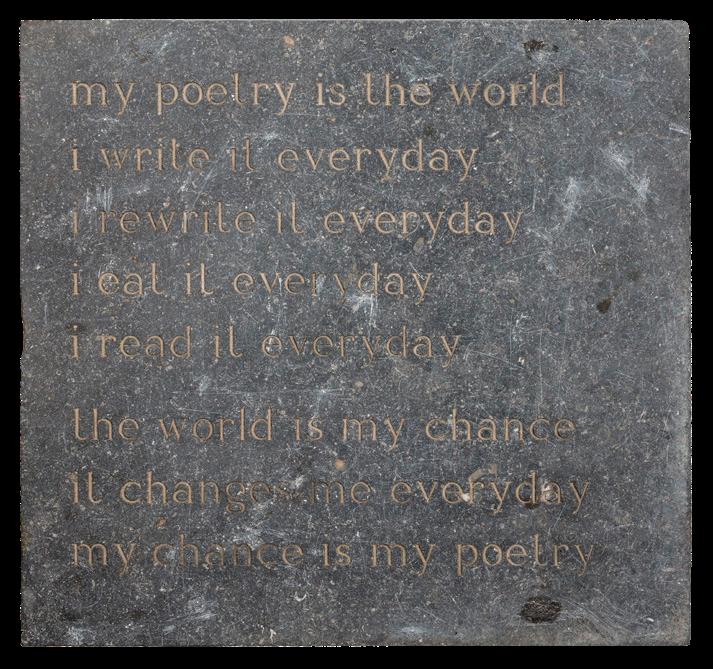

De poëzie van de wereld

Voor herman de vries (1931) is natuur gelijk aan kunst. Deze tegel is een lofzang aan de poëzie van de wereld, een kunstwerk waar ook hij onderdeel van is. De natuur zelf is het grootste gedicht, dat de vries elke dag in dankbare verwondering leest. De kunstenaar, van oorsprong plantkundige, verzamelt objecten uit de natuur. Sinds 1970 woont hij in Eschenau, een Duits dorpje aan de rand van een groot bos dat zijn atelier vormt. In zijn collages en installaties presenteert de vries zijn vondsten – bladeren, grassen, grondmonsters – precies zoals hij ze vindt. Deze uitstallingen reflecteren zijn visie op de natuur als een domein dat eigenlijk niet past in de strenge wetenschappelijke categorieën die de vries kent uit zijn voormalige vakgebied. Hij ziet dat de natuur zich ontwikkelt door toeval en kans, ‘chance’. De groei van een plantje is bijvoorbeeld afhankelijk van omstandigheden die nooit exact hetzelfde zijn. Alles dat leeft is dan ook eindeloos divers. De vries omarmt deze willekeur: hij observeert en toont de voortdurende verandering – ‘change’ – van zijn omgeving zonder in te grijpen. Zo bewaart hij de openheid en vrijheid van de natuur.

The poetry of the world

For herman de vries (1931), nature is equivalent to art. This tile is an ode to the poetry of the world, a work of art that he is also a part of. Nature itself is the greatest poem, which de vries reads every day in grateful amazement. The artist, originally a botanist, collects objects from nature. Since 1970 he has lived in Eschenau, a German village on the edge of a large forest that constitutes his studio. In his collages and installations, de vries presents his finds – leaves, grasses, soil samples – precisely as he found them. These presentations reflect his view of nature as a domain that does not actually fit into the strict scientific categories familiar to de vries from his former profession. He sees that nature develops by coincidence and chance. The growth of a plant, for example, depends on conditions that are never exactly the same. All living things are therefore endlessly diverse. De vries embraces this randomness: he observes and shows the constant change of his surroundings without intervening. Thus he preserves the openness and freedom of nature.

herman

Verlost van verdriet

Jacques Lipchitz (1891-1973) maakt Le cri (Le couple) in een periode van rouw. In korte tijd zijn zijn vader, zijn zus en een goede vriend overleden. Het maakproces van het bronzen beeld blijkt een emotionele ontlading. Hij vertelt: ‘Ik was vervuld van vreselijk verdriet en depressieve gevoelens, maar omdat ik van nature geen pessimist ben, maakte ik dit sculptuur als een soort bevrijding, een trotsering om te laten zien dat het leven door moet gaan te midden van tragedie, dat we moeten leven en ons moeten vermenigvuldigen. Te midden van de dood is er liefde en voortplanting en geboorte.’ Aanvankelijk heet het beeld Le couple, het paar, wat als een te letterlijke verwijzing naar de intieme houding van dit vrijend stel wordt opgevat. Lipchitz verandert de titel en noemt het Le cri, de schreeuw: de kreet van wanhoop is een zucht van opluchting geworden. Door te creëren heeft de kunstenaar zichzelf van zijn verdriet verlost.

Released from sorrow

Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973) creates Le cri (Le couple) (The Scream (The Couple)) in a period of mourning. In a short time, his father, his sister and a close friend have died. The process of creating the bronze sculpture proves to be an emotional release. He recounts: ‘I was filled with a terrible sadness and depression, but because I am not a pessimist by nature, I made this sculpture as a kind of liberation, a defiance to show that life must go on in the midst of tragedy, that we must live and multiply. In the midst of death, there is love and procreation and birth’. Initially, the sculpture was called Le couple, the couple, which was considered too literal a reference to the intimate pose of this couple making love. Lipchitz changes the title and calls it Le cri, the scream: the cry of despair has become a sigh of relief. Through the act of creation, the artist has released himself from his sorrow.

Jacques Lipchitz, Le cri (Le couple), 1928-29

Je eigen plaats bepalen

In de jaren 60 en 70 vinden er grote veranderingen plaats in de beeldhouwkunst. Kunstenaars breken met het traditionele idee van een beeld op een sokkel in een afgesloten museumzaal. Ze verleggen de grenzen en maken onder meer enorme werken die in direct verband met de natuurlijke omgeving staan. Ook in de beeldentuin van het Kröller-Müller Museum krijgen kunstenaars de ruimte.

Spin Out, for Robert Smithson van Richard Serra (1938-2024) vormt een ingreep in het omliggende landschap. Het werk bestaat uit drie staalplaten in een valleikom. Vanuit het lege centrum van de vallei zie je pas dat de platen geen middelpunt creëren. Hierdoor ontstaat een denkbeeldige, naar buiten draaiende beweging – een ‘spin out’– die haaks staat op de doorgaans naar binnen gerichte aard van de valleikom. Deze op elkaar in werkende krachten zorgen voor een nieuwe ruimtelijke beleving, die je ervaart door rond te lopen. Je wordt als het ware opgenomen in het werk. Tegelijkertijd is het een uitnodiging je te bewegen in en te verhouden tot de omgeving.

Define your own place

In the 1960s and 1970s, major changes occur in the field of sculpture. Artists break with the traditional idea of a sculpture on a pedestal in an enclosed museum room. They push the boundaries and create, among other things, enormous works that are directly connected to the natural environment. Artists are also provided space in the sculpture garden of the Kröller-Müller Museum.

Spin Out, for Robert Smithson by Richard Serra (1938–2024) is an intervention in the surrounding landscape. The work consists of three steel plates in a valley basin. Only from the empty centre of the valley can you see that the plates do not create a focal point. This results in an imaginary, outward turning movement – a ‘spin out’ – which is at odds with the typically inward nature of the valley basin. These interacting forces create a new perception of space, which you experience by walking around. You become absorbed into the work, so to speak. At the same time, it is an invitation to move in and relate to the environment.

Richard Serra, Spin Out, for Robert Smithson,1972-73

Een proteststem

Chen Zhen (1955-2000) groeide op in China tijdens de Grote Proletarische Culturele Revolutie (19661976) geleid door de communistische dictator Mao Zedong (1893-1976). Het is een periode van gewelddadige politieke onderdrukking en chaos. Met Resonance verbeeldt Chen de verstikkende macht van dit regime, maar ook de kracht van het volk om zich hiertegen te verzetten. Een klok werd van oudsher gebruikt om de tijd te communiceren en belangrijk nieuws van hogerhand aan te kondigen. Een ander, moderner middel voor massacommunicatie is de megafoon. Tijdens de Culturele Revolutie werd die ingezet om op grote schaal ideologische propaganda uit te dragen. Chen houdt de megafoons in Resonance echter onheilspellend stil, als symbool voor een dictatuur die ieder de mond snoert. De kapotte stoelen onder de bel staan voor de macht die de massa kan opeisen door in protest te gaan. Chen verwijst hier naar een eeuwenoud Chinees gezegde over de verhouding tussen volk en machthebber: ‘water kan de boot dragen, maar kan de boot ook doen omslaan’.

A voice of protest

Chen Zhen (1955–2000) grew up in China during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) led by communist dictator Mao Zedong (1893–1976). It was a period of violent political repression and chaos. With Resonance, Chen depicts the suffocating power of this regime, but also the power of the people to resist it. A bell was traditionally used to communicate time and announce important news from higher up. Another more modern means of mass communication is the megaphone. During the Cultural Revolution, this was used to broadcast ideological propaganda on a large scale. However, Chen keeps the megaphones ominously quiet in Resonance, symbolising a dictatorship that silences everyone. The broken chairs under the bell represent the power that the masses can claim by protesting. Here Chen refers to an ancient Chinese proverb about the relationship between the people and those in power: ‘water can float the boat, but can also capsize the boat’.

Chen

Grenzeloze vrijheid

Needle Tower is gebaseerd op Kenneth Snelsons (1927-2016) principe van ‘tensegrity’, dat hij in 1948 ontwikkelt: trekkende en drukkende krachten die elkaar in evenwicht houden. Snelsons ranke bouwwerk heeft een hoogte van 26,5 meter, maar lijkt zich uit te strekken tot in het oneindige. De toren is opgebouwd uit staalkabels en aluminium staven, die naar boven toe steeds kleiner en smaller worden en de indruk geven te zweven.

Needle Tower is een werk vol spanning. Er is het letterlijke krachtveld tussen de kabels en de staven die de constructie overeind houden. Maar ook is er het contrast tussen het ogenschijnlijk luchtige karakter van de toren en het strakke netwerk van precies uitgebalanceerde onderdelen die de structuur stabiel doen staan. Met een minimale hoeveelheid materiaal weet Snelson in zijn Needle Tower een gevoel van maximale, grenzeloze vrijheid te creëren. Maar als je goed kijkt zie je dat het in werkelijkheid rust op een nauwgezet, vastgesteld systeem.

Boundless freedom

Needle Tower is based on the principle of ‘tensegrity’, which Kenneth Snelson (1927–2016) developed in 1948: pulling and pushing forces that balance each other. Snelson’s slender structure has a height of 26.5 metres, but seems to stretch into infinity. The tower is composed of steel cables and aluminium rods, which become increasingly smaller and thinner towards the top and give the impression of floating. Needle Tower is a work full of tension. There is the literal interplay of force between the cables and rods that keep the construction upright. But there is also the contrast between the seemingly ethereal nature of the tower and the tight network of precisely balanced components that keep the structure steady. With a minimal amount of material, Snelson manages to create a sense of maximum, boundless freedom in his Needle Tower. But if you look closely, you can see that it actually relies on a meticulous, well established system.

Kenneth Snelson, Needle Tower, 1968

Vlag van verzoening

Van de ene kant lijkt de witte vlag van overgave te wapperen, maar zodra je de zwarte kant ziet vertroebelt die boodschap. Reiner Ruthenbeck (1937-2016) verwijst met Schwarz/weisse Doppelfahne naar de vlag als symbool voor de natiestaat. De kunstenaar relativeert de zwaarte van dit officiële symbool, dat vaak gepaard gaat met nationalistische en zelfs militaire associaties. Hij lijkt een ironisch commentaar te leveren op de nationale trots waar een vlag doorgaans voor staat.

Ruthenbecks vlag is een dubbele vlag, die bestaat uit twee losse, contrasterende doeken. De kunstenaar streeft in dit werk naar evenwicht tussen de twee tegengestelden en wil een gevoel van balans en eenheid tussen tegenpolen creëren. Hoewel Schwarz/weisse Doppelfahne statig aan een metershoge mast hangt, functioneert deze dus niet als teken van nationale identiteit. Ruthenbeck keert juist weg van die betekenis en zet met zijn werk aan tot denken over de verdeeldheid die daaruit kan voortkomen. Hier wappert de dubbele vlag van verzoening.

Flag of reconciliation

From one side, the white flag of surrender seems to be flying, but as soon as you see the black side, that message becomes blurred. With Schwarz/weisse Doppelfahne (Black / White Double Flag), Reiner Ruthenbeck (1937–2016) refers to the flag as a symbol of the nation state. The artist puts into perspective the weight of this official symbol, which is often accompanied by nationalistic and even military associations. He seems to be making an ironic comment on the national pride that a flag usually represents.

Ruthenbeck’s flag is a double flag, consisting of two separate, contrasting canvases. In this work, the artist seeks to balance the two opposites and to create a sense of equilibrium and unity between counterparts. So although Schwarz/ weisse Doppelfahne hangs majestically from a pole several metres high, it does not function as a sign of national identity. Instead, Ruthenbeck rejects that meaning and through his work encourages us to contemplate the divisions that can result from it. Here the double flag of reconciliation flies.

Reiner Ruthenbeck, Schwarz/weisse Doppelfahne, 1985

Lijf en leven

Alina Szapozcnikow (1926-1973) beseft al vroeg dat het menselijk lichaam kwetsbaar is. Ze overleeft haar tienerjaren in Poolse nazi-getto’s en concentratiekampen, waar ze als verpleegkundige werkt. Na de oorlog vindt ze haar creatieve vrijheid in een radicaal nieuwe beeldhouwkunst. Kunst maken wordt voor Szapocznikow de uiterste bevestiging van het leven. In haar werk ontleedt ze het lichaam en geeft het weer in fragmenten. Afgietsels van haar eigen lichaamsdelen, zoals mond, benen en borsten, vermaakt ze tot sculpturen van gips, brons of kunsthars. Haar beelden zijn sensueel en tegelijk vreemd en macaber. Ze breken met de traditionele, vaak eenzijdige weergave van de vrouwelijke vorm.

Wielkie brzuchy, grote buiken, is gebaseerd op een afgietsel van de buik van een vriendin, hier verdubbeld en uitvergroot. Het duurzame marmer contrasteert met de vergankelijkheid van het menselijk lijf waar de kunstenaar zich zo van bewust is. Ook is marmer een klassiek materiaal voor monumentale standbeelden en bustes.

Szapocznikow gebruikt het juist voor de verbeelding van een meestal verborgen, intiem lichaamsdeel.

Wielkie brzuchy is een ode aan het fragiele lichaam, dat ondanks trauma en verval blijft voortbestaan.

Body and life

Alina Szapozcnikow (1926–1973) realised the fragility of the human body at an early age. She survived her teenage years in Polish Nazi ghettos and concentration camps, where she worked as a nurse. After the war, she finds creative freedom in a radical new form of sculpture. For Szapocznikow, making art becomes the utmost affirmation of life. In her work, she dissects the body and depicts it in fragments. She transforms casts of her own body parts, such as mouth, legs and breasts, into sculptures of plaster, bronze or synthetic resin. Her sculptures are sensual yet strange and macabre. They depart from the traditional, often one-sided representation of the female form. Wielkie brzuchy, large bellies, is based on a cast of a friend’s belly, here doubled and enlarged. The durable marble contrasts with the transience of the body, of which the artist is acutely aware. Marble is also a classic material for monumental statues and busts. However, Szapocznikow uses it here to depict a part of the body that is intimate and normally hidden. Wielkie brzuchy is an ode to the fragile body, which endures despite trauma and deterioration.

Alina Szapocznikow, Wielkie brzuchy, ca. 1968

De stem van de natuur

De geluidsinstallatie The Wind Rose van Susan Philipsz (1965) bestaat uit acht tonen, die via acht verborgen luidsprekers worden afgespeeld. Het geluid ontstaat door te blazen op een hoornschelp. De kunstenaar maakte gebruik van hoornschelpen uit verschillende plekken op de wereld, zoals een ceremoniële horagai-schelp uit Japan en een grote koninginneschelp uit de Florida Keys. De klanken zijn atonaal, hebben geen vaste toonsoort. Ze symboliseren de acht windrichtingen op aarde en klinken allemaal anders, variërend van een razende storm tot een zacht briesje. Een traag samenzang ontstaat, die enigszins droevig en verontrustend klinkt maar ook een gevoel van rust en kalmte creëert. Philipsz heeft het beukenbos een stem gegeven. Het zucht, kreunt en huilt. De bomen lijken zelf te ademen, gelijk aan de menselijke ademhaling, als een metafoor voor het leven en onze sterfelijkheid. The Wind Rose moet je zelf ervaren: zit, lig of beweeg tussen de bomen en geluiden en luister naar wat de natuur te vertellen heeft.

The voice of nature

The sound installation The Wind Rose by Susan Philipsz (1965) consists of eight tones played through eight hidden speakers. The sound is created by blowing into a conch shell. The artist used conch shells from different places around the world, such as a ceremonial horagai shell from Japan and a large queen conch shell from the Florida Keys. The sounds are atonal and have no fixed key. They represent the earth’s eight major wind directions and all sound different, from a raging storm to a gentle breeze. A slow harmonic resonance is produced, sounding somewhat sad and unsettling but also creating a sense of peace and calm. Philipsz has given the beech forest a voice. It sighs, moans and cries. The trees themselves seem to breathe, similar to human breathing, as a metaphor for life and our mortality. You have to experience The Wind Rose for yourself: sit, lie or move among the trees and sounds and listen to what nature has to say.

Susan Philipsz, The Wind Rose, 2019

Jean Dubuffet, Jardin d’émail, 1974

Kunstspeeltuin

Jardin d’émail van Jean Dubuffet (1901-1985) vormt met zijn stralend witte oppervlak en zwarte lijnen een enorm contrast met de omliggende groene natuur. Via een kleine doorgang kom je bovenop deze ommuurde tuin uit. Als je er eenmaal op staat, ontvouwt zich plots een hele nieuwe wereld: een glooiend landschap met een ‘boom’ en enkele ‘struikjes’. De zwart-witte wereld is als een ander universum, dat losstaat van alledaagse structuren en maatschappelijke normen. Hier gelden de gangbare voorschriften voor omgang met kunst niet. Jardin d’émail is namelijk gemaakt om aan te raken en op te lopen. Dubuffet putte onder andere inspiratie uit tekeningen van kinderen. Hierin zag hij échte ongeremde expressie, vrij van de regels en conventies van de gevestigde kunstwereld. Ook in deze ‘kunstspeeltuin’ overheerst een gevoel van kinderlijke verwondering. Dubuffet stimuleert een radicaal nieuwe verhouding tot kunst, die de nieuwsgierigheid en fantasie activeert. Zelfs als volwassene krijg je zin om te spelen.

Art playground

With its brilliant white surface and black lines, Jardin d’émail by Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) creates a huge contrast with the surrounding green nature. A small passageway leads you to the top of this walled garden. Once you get up there, a whole new world suddenly unfolds: a rolling landscape with a ‘tree’ and several ‘bushes’. The black and white world is like another universe, detached from everyday structures and social norms. The usual rules for dealing with art do not apply here. This is because Jardin d’émail is made to be touched and walked on. Dubuffet drew inspiration from children’s drawings, among other things. In these he saw true uninhibited expression, free from the rules and conventions of the established art world. A sense of childlike wonder also prevails in this ‘art playground’. Dubuffet encourages a radically new relationship to art, which activates curiosity and imagination. Even as an adult, it makes you want to play.

Weiner, EEN VERZAMELING VAN HETGEEN SAMENHANGT MET GEBRUIK IN EEN GEMATIGD / WARM / KOUD KLIMAAT, 1981

Ruimte voor kunst

Het materiaal van Lawrence Weiner (1942-2021) is taal. Zijn werken bestaan uit woorden en teksten. Toch noemt Weiner zijn werken beeldhouwkunst, omdat hij ervan overtuigd is dat taal alleen genoeg is om visueel iets tot stand te brengen. De gelezen woorden roepen in je hoofd een beeld op. EEN VERZAMELING VAN HETGEEN SAMENHANGT

MET GEBRUIK IN EEN GEMATIGD / WARM / KOUD

KLIMAAT is zo’n tekstueel werk. Weiner verwijst met de tekst niet alleen naar de collectie van het museum, maar ook naar het klimaat. Dit klimaat kan worden opgevat als een spiritueel klimaat, waarin kunst kan gedijen. Het is van toepassing op Helene Kröller-Müller (1869-1939), die een plek in de natuur creëerde waar haar verzameling door iedereen geestelijk ervaren kan worden. Het is een omgeving waarin kunst in alle vrijheid onbeperkt kan bloeien.

Let op, dit kunstwerk bevindt zich aan de voorzijde van het museum.

Space for art

The material of Lawrence Weiner (1942–2021) is language. His works consist of words and texts. Nevertheless, Weiner calls his works sculpture, because he is convinced that language alone is enough to create something visual. The words when read evoke an image in your mind. EEN VERZAMELING VAN HETGEEN SAMENHANGT MET GEBRUIK IN EEN GEMATIGD / WARM / KOUD KLIMAAT (A GROUPING OF THAT WHICH IS CONNECTED WITH USE IN A TEMPERATE / HOT / COLD CLIMATE) is one such textual work. With his text, Weiner refers not only to the museum’s collection, but also to its climate. This climate can be understood as a spiritual climate, in which art can thrive. And it applies to Helene Kröller-Müller (1869-1939), who created a place in nature where her collection can be experienced spiritually by everyone. It is an environment in which art is entirely free to flourish without restrictions.

Please note: this work of art is at the front of the museum.

Lawrence

Deze brochure is gemaakt ter gelegenheid van het tachtigjarige jubileum van de bevrijding van Nederland.

This brochure was created to coincide with the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Netherlands.

Tekst en samenstelling / Text and composition

Kröller-Müller Museum

Vertaling Nederlands-Engels / Dutch-English translation Mike Ritchie

Vormgeving / Design Saiid & Smale, Amsterdam Fotografie / Photography Marjon Gemmeke, Cary Markerink, Victor Nieuwenhuijs, archief / archive Kröller-Müller Museum

Druk / Print Aeroprint, Ouderkerk aan de Amstel

Mede mogelijk gemaakt door / Made possible by the support of