If you have untreated hearing loss, you may not be enjoying the show to its fullest! Let us help enhance your next symphony experience with better hearing! Schedule your comprehensive hearing evaluation today!

If you have untreated hearing loss, you may not be enjoying the show to its fullest! Let us help enhance your next symphony experience with better hearing! Schedule your comprehensive hearing evaluation today!

It is the first painting I created after surviving a devastating home propane explosion, which led to a ten-week recovery in a major burn center in San Antonio, Texas. Initially given less than a 20% chance of survival, I was determined to live— through pain, through uncertainty, through fire.

This work represents more than survival; it is a testament to rebirth. From the flames, I emerged into the singularity of the present moment—into each new day of my life. “Now and Forevermore” speaks to that transformation and to the enduring strength found in choosing to begin again.

100 Years of Route 66, July 31 – August 10, 2026 Santa Fe Opening Reception: Friday, July 31st from 5 – 7 pm

El Castillo/La Secoya is a continuing care retirement community in downtown Santa Fe. We offer independent and assisted living, nursing services, and memory care. Contact 505-995-2110 for more information or a tour. Independent living apartments available now!

Wallman Marketing Director

Regina Klapper Patron Services Manager

Marketing Assistant

Katie Rountree Development Director

Laura Witte Events & Annual Fund Manager

Jennifer Ferraro Grants Manager

Susan Meredith Finance Director

Nicolle Maniaci Personnel Manager

Curtis Mark Stage Manager

Amy Huzjak Operations Assistant & Orchestra Librarian

Callie Kent Education & Community Director

Elizabeth Young Youth Program Director

William Waag Associate Director, Youth Education

Milliken Chorus Librarian

Grace Davis Office Coordinator

All of us here at The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus want to make your experience with us as wonderful as possible. Whether it’s securing your favorite seats for one of our live performances, enrolling your child in one of our award-winning Youth Education classes, or exploring how best to support The Symphony through one of our many giving opportunities, we are just a phone call or e-mail away.

In 2025–2026, The Santa Fe Symphony offers something for everyone. Each of our concerts, whether at the Lensic, Cathedral, or elsewhere in the community, has The Symphony’s trademark balance of repertoire: ranging from much-beloved masterworks to rarely-performed gems.

We believe that great music has the power to transform lives and bring communities together. When you support The Santa Fe Symphony with a ticket purchase or donation, you are supporting professional orchestral and choral musicians in your community, as well as an

There are so many ways to get involved with The Symphony. Invite a friend to join you for a concert. Volunteer to assist with our performances or in the office. Join our family of subscribers, donors, and friends. Sponsor a soloist or adopt a musician. Get involved with our education and community programs. Share your thoughts with us and tell us what you’d like to hear!

Thank you for your support of great music in Santa Fe. See you

The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus is proud to serve and entertain residents in our community. We want to play our part in keeping music—in all its forms—a vibrant and important part of the lives of all of us in Northern New Mexico.

• 9,000 attend ticketed orchestral and/or choral concerts at the Lensic

• Patrons are almost entirely local to Northern New Mexico

• 12 ticketed concerts featuring Orchestra, Chorus, Chamber Music

• 20+ free concerts each season featuring Orchestra, Chorus, and Chamber Ensembles

• 20+ Youth Program concerts each season featuring the 300+ students in our after-school programs for orchestra, jazz, mariachi, chamber music, and chorus

• Each year, we employ 100+ New Mexican orchestral and choral musicians

• Donor support is vital – ticket sales only account for 25% of annual revenue

• Donor support enables the symphony to attract world-class musicians, guest artists, and conductors, delivering inspiring performances that elevate the cultural life of the region

Whether you’re an individual, granting authority, foundation, or business, you can give with confidence. A Platinum Seal awarded by Candid ensures our records are available for review online, providing evidence your investment in The Symphony is safe and that your donations will be used as you request.

We’re committed to enriching the lives of area children and their families through the performing arts. We encourage young people to explore their potential in all areas of life while helping them develop their musical skills.

• 20+ weekly classes for students ages 7-20, teaching: Orchestra, Chorus, Mariachi, Jazz, Chamber Music

• 20+ Youth Program concerts each season

• Over 5,000 students have participated in youth music classes since 1994

• 400+ students receive after-school and in-school programming

• 1,500+ students receive classroom visits and attend their first Symphony Concert at the Lensic each year

FINANCIAL AID: 27% of students qualify for aid and 100% of students who applied received tuition and instrument rental assistance. Assistance is offered “no questions asked,” with no tax returns required.

STUDENT DEMOGRAPHICS: 29% Hispanic/Latino, 8% Asian, 3% Native American, 3% African American, 57% Caucasian

BILINGUAL SUPPORT: 11% of families served are primarily Spanish-speaking at home. The Symphony has a bilingual enrollment process, Spanish-speaking support staff, and Spanish-speaking class instructors.

Best Youth Arts Program 2025 — Santa Fe Reporter

SYMPHONY OF SERENITY awaits in the Land of Enchantment

fourseasons.com/santafe

PRE SIDENT

Perry C. Andrews III

VICE PRESIDENT, DEVELOPMENT

Mary Macukas, CFP®, CPWA®

VICE PRESIDENT, EDUCATION

Steven J. Goldstein, MD

VICE PRESIDENT, MARKETING

Robert Vladem

SECRETARY

Justin Medrano

TREASURER

David Van Winkle

HONORARY COUNCIL

Ann Neuberger Aceves

E. Franklin Hirsch

NO

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

Laura Chang, Orchestra Musician

Ann Dederer

Laura Dwyer, Orchestra Musician

Stephen Eastwood

Emily Erb, Orchestra Musician

Jose (“Pepe”) Figueroa

Kimberly Fredenburgh, Orchestra Musician

Naomi Israel

Kathy Landschulz, Chorus Council President

William Landschulz

Boo Miller

Ifan Payne

Teresa Pierce

Dr. Stefanie Przybylska, Orchestra Musician

Lee Rand

Rebecca Ray, Orchestra Musician

Laurie Rossi

Robin Smith, Foundation President

Gloria Velasco, Orchestra Musician

Everett Zlatoff-Mirsky

WHAT ROLE

— Perry C. Andrews III, Board President

As I sit here in front of my laptop on this beautiful, sunny summer morning in mid-June reflecting on both this past year as well as the next, I think about the significance of the many accomplishments and success stories YOUR Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus has experienced during the last 12 months and our high expectations as we move into our 42nd Season in 2025-2026.

Twelve months ago, we were rapidly nearing our merger date of July 1, 2024 which would bring about the successful (and dare I say unique) combining of two of Santa Fe’s premier and financially sound performing arts organizations. With 70 years of combined service to the greater Santa Fe community, The Santa Fe Symphony and the Santa Fe Youth Symphony Association became one, forging a pathway for the combined organization to exponentially expand and enhance its outreach, youth education and mentorship to students throughout Santa Fe and beyond via our orchestra, mariachi, jazz and choral Projects.

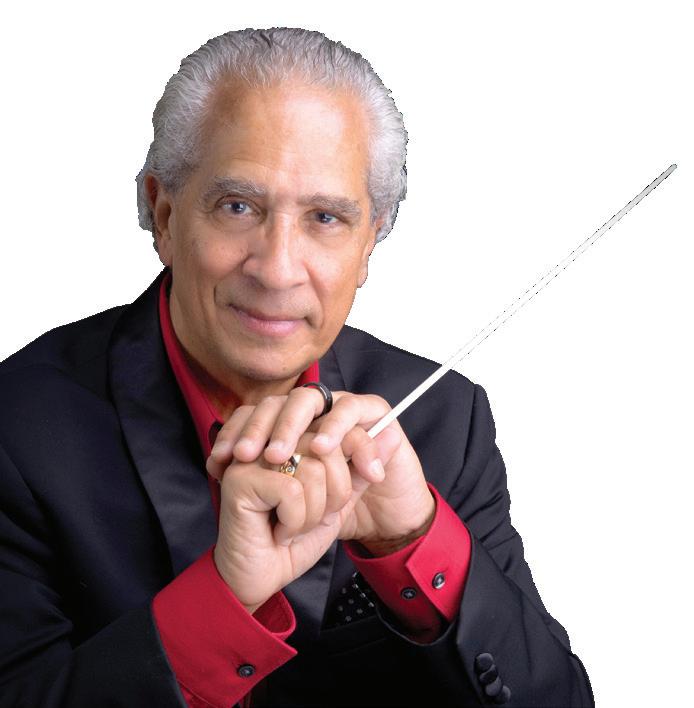

This past season once again found our amazingly talented New Mexico orchestral and choral musicians, as well as an impressive lineup of guest soloists, performing to sellout crowds on stage at The Lensic Performing Arts Center, including major works seldomly performed such as our season finale, Hector Berlioz’s La damnation de Faust, conducted by Maestro Guillermo Figueroa.

This coming 2025-2026 Season promises to be nothing short of equally spectacular! Maestro Figueroa, Choral Director Carmen Flórez-Mansi, along with our orchestral and choral musicians will have you on the edge of your seat. Starting in September with guest violinist and longtime Santa Fe favorite Alexi Kenney all the way through to our season finale in May with two performances of Carl Orff’s incomparable cantata Carmina Burana – from start to finish, our 42nd Season is absolutely one you won’t want to miss!

On behalf of everyone at The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus – our truly amazing staff, incredibly talented musicians and my fellow Board members who give so much of their time – let me end by sending a huge and very sincere “THANKS” to all of YOU, our greatly appreciated donors, season subscribers, single ticket purchasers, sponsors and community partners. Without all of YOU – especially now, in these times of increasing uncertainty regarding the future of the performing arts – we couldn’t do what we do every day, bringing great music to life in our “City Different!”

Perry C. Andrews III Board President

VIOLIN I

David Felberg, Concertmaster

Ruxandra Marquardt, Assistant Concertmaster THE BOO MILLER ASSISTANT CONCERTMASTER CHAIR

Elizabeth Young

Alan Mar

Elizabeth Baker

Carol Swift

Rebecca Callbeck

VIOLIN II

Nicolle Maniaci, Principal Violin II

Sheila McLay

Laura Chang

Anne Karlstrom

Lidija Peno-Kelly

Laura Steiner

Justin Pollak

Carla Kountoupes

Valerie Turner

Gloria Velasco

VIOLA

Kimberly Fredenburgh, Principal Viola

Lisa Ann DiCarlo-Finch

Barbara Clark

Allegra Askew

Christine Rancier

Virginia Lawrence*

CELLO

Dana Winograd, Principal Cello

THE DR. PENELOPE PENLAND PRINCIPAL CELLO CHAIR

Joel Becktell, Assistant Principal Cello

Erin Espinoza*

Melinda Mack

Lisa Collins

James Holland*

BASS

Terry Pruitt, Principal Bass

Kathy Olszowka

Sam Brown

Frank Murry

FLUTE

Jesse Tatum, Principal Flute

Laura Dwyer

OBOE

Elaine Heltman, Principal Oboe

Rebecca Ray

CLARINET

Lori Lovato, Principal Clarinet

Emily Erb

BASSOON

Dr. Stefanie Przybylska, Principal Bassoon

Leslie Shultis

HORN

Daniel Nebel, Principal Horn

Andrew Meyers

Peter Erb

Allison Tutton

TRUMPET

Jennifer Brynn Marchiando, Principal Trumpet

Sam Oatts

TROMBONE

Lynn Mostoller

BASS TROMBONE

Dave Tall, Principal Bass Trombone

TUBA

Dr. Richard White, Principal Tuba

TIMPANI

Ken Dean, Principal Timpani

HARP

Carla Fabris, Principal Harp

*ON LEAVE 2025–2026 SEASON

Scan to view the choral musician roster for each concert.

I am thrilled for The Santa Fe Symphony’s 2025-2026 Season. For our 42nd concert season, we have selected a fantastic array of music for your enjoyment—from well-known and beloved classics such as Brahms’ First Symphony and Dvorak’s New World Symphony to more recent works such as Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story and Moncayo’s Huapango.

Special highlights for me are the appearances of three great virtuosos—violinist Alexi Kenney, returning to Santa Fe as part of our opening concert; pianist Olga Kern playing Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini on our February concert, and cellist David Finckel from the Emerson Quartet, performing Strauss’ Don Quixote, a masterpiece for cello and orchestra. And for our grand finale in May, our extraordinary Santa Fe joins us on stage in the ever-popular

The 2025-2026 Season promises to be our best ever. Thrilling and innovative programs overflowing with glorious music, our exceptionally fantastic orchestra, an outstanding symphonic chorus, and a gorgeous theater

Pasatiempo presents a rigorous composition of things to see and do in Santa Fe — from checking out the city’s world-class musical offerings presented by the Santa Fe Symphony to exploring the renowned arts and culture scene. Find it on newsstands, in the Friday edition of The Santa Fe New Mexican, and online at pasatiempomagazine.com. And don’t miss a beat by signing up for the Pasatiempo weekly newsletter at santafenewmexican.com.

SOPRANO

Lany Berger

Nia Brannin

Sophia Carillo•

Danielle Cordova*

Anastasia Docherty

Heather Eaves

Alexandra Esquibel*

Patricia Fasel

Jolene Gallegos

Charlotte Grenier

Divara Harper

Susan Harris

Amy Hernandez•

Megan Huston

Katherine Keener*+

Amrita Khalsa•

Ansley King•

Kristin MacKowski

Liza Martinez

Kelsea Martinez-Eggleston+

Audrey McKee

Dalia Melendez*

Cyra Mersereau

Bettina Milliken

Elizabeth Neely

Elizabeth Roghair

Amanda Sidebottom*

Paula Young

Elizabeth Zollo

ALTO

Petra Archuleta•

Talitha Arnold

Luana Berger*

Robin Chavez+

Juliana Chiano

Barbara Cooper

Rachelle Elbert

Joseph Fasel

Mary Fellman*

MaryAlice Gillette

Libby Gonzales

Priscilla Gray•

Paige Johns

Colleen Kelly

Kehar Koslowsky*+

Katherine Landschulz+

Jahn Clarisse Madlangbayan

Maya Charlie Ortiz•

Amanda Penaloza

Joann Reier

Edna Reyes-Wilson

Anna Richards+

Judith Rowan

Joan Snider

Sveuja Strieker

Wendy Wilson

Laura Witte*+

Diana Zeiset

TENOR

Mattéo Bitetti

Rev. Doug Escue*

O’Shaun Estrada*+

Stephen Fasel*

Antonio Gonzales

Sarah Gupta

Robert Hoffman

Landen Kessler•

Grayson Kirtland

Joe Long

Fintan Long

Jonah Scott Mendelsohn*

Karson Nance

Joshua Narlesky

Todd Ritterbush

Nate Salazar*

Wesley Sisson

BASS

Jerel Brazeau

Devin DeVargas*+

Patrick Dolin

Bob Florek

David Foushee+

Anthony Hernandez•

Lewis Johnson

Peter B. Komis

Nicholas Lopez*

Dan Morton

Andrew Paulson*

Alan Rosales•

Issac Rosales•

Thomas Rogowskey

Richard Schacht*

Jim Schute

Carlos Vazquez-Baur*+

Roy Yinger+

Paul J. Roth+, Collaborative Piano

• Choral Scholar

+ Adopted

* Chamber Singer

CHORUS COUNCIL

Kathy Landschulz, President

Jerel Brazeau, Vice President

Rev. Doug Escue, Treasurer

Bettina Milliken, Chorus Librarian

Joseph Fasel

Jolene Gallegos

Carmen Flórez-Mansi, Ex Officio

Laura Witte, Ex Officio, Chorus Manager

Scan to view the choral musician roster for each concert.

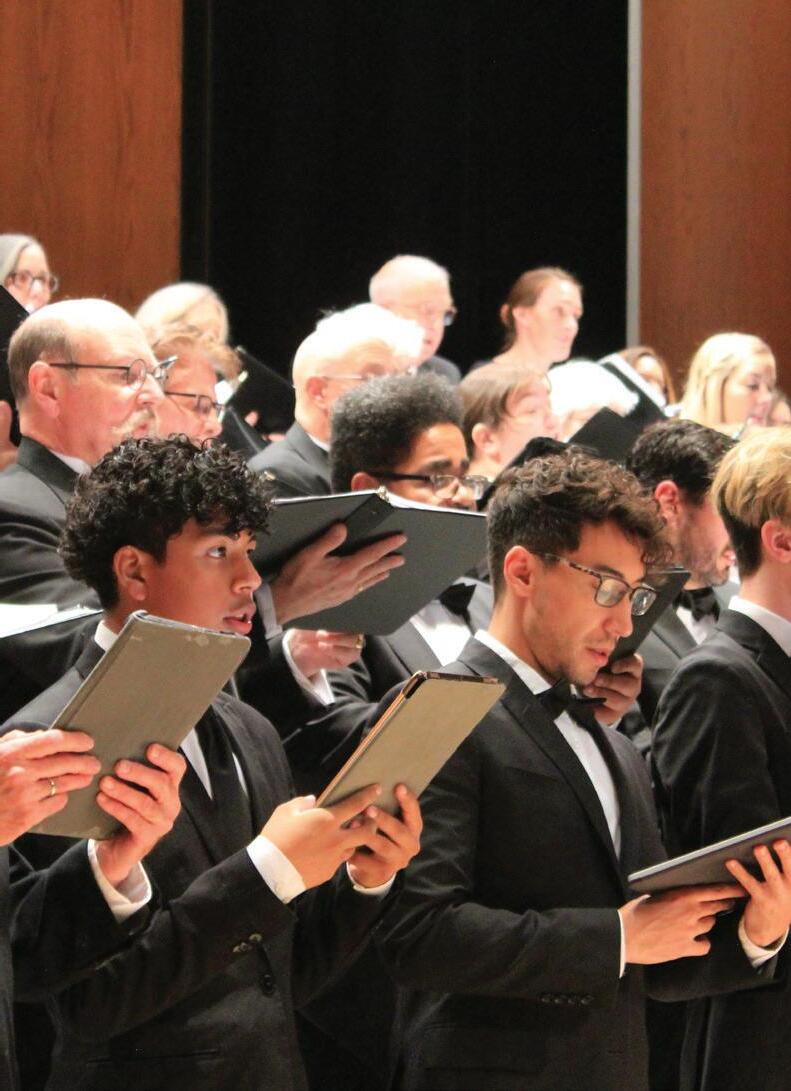

The Santa Fe Symphony Chorus is a community of the most generous, dedicated, and skilled choral musicians of Northern New Mexico and the surrounding areas. In my eight-year tenure, we have together created a nurturing environment in which we can grow and create beautiful and challenging choral masterworks at the highest level of performance. As a choral community we are proud to come together to present choral singing at its finest that excites the senses and touches the heart in ways that only choral music can provide.

The richness of the music presented by our fine choral musicians is only matched by the richness and diversity of our singers, which represents the community of Santa Fe. Last year we debuted our choral youth program locally, and by the end of the season, we were getting a new children’s chorus ready to launch this September in Los Alamos. These new beginning and intermediate youth choirs, along with the wonderful advanced Choral Scholars, will now ensure that choral music will continue to grow for years to come.

We are honored to continue this great tradition of excellence in choral music with the exciting choral offerings this season in our collaboration with Maestro Figueroa, and the amazing orchestral musicians of The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra.

I am thrilled and honored to work with the members of our superb chorus and orchestra and experience the great joy of creating art and beauty in our community. I am eager to lead them to new heights this season.

Carmen Flórez-Mansi

EMBARK ON YOUR CUSTOM-TAILORED FINANCIAL JOURNEY

At Enterprise Bank & Trust, we believe in banking that goes beyond transactions. It’s about creating a relationship where your needs guide our actions. From individualized financial solutions to dedicated advisory services, we’re here to turn your goals into achievements.

Scan the QR code or visit enterprisebank.com/private-banking to discover the Enterprise Private Banking difference.

Enterprise Bank & Trust proudly stands alongside The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus. Together, we are dedicated to preserving The Symphony’s rich history while embracing exciting new, youth-centered initiatives presented through The Symphony’s education and community programs.

Learn more about Enterprise’s community partnerships at enterprisebank.com/impact.

Together, there’s no stopping you.

ALEXI KENNEY, Violin

Violinist Alexi Kenney is forging a career that defies categorization, following his interests, intuition, and heart. He is equally at home creating experimental programs and commissioning new works, soloing with major orchestras, and collaborating with some of the most celebrated artists and musicians of our time. Alexi is the recipient of an Avery Fisher Career Grant and a Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award.

Alexi has performed as soloist with the Cleveland Orchestra, the San Francisco, Dallas, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and San Diego symphonies, l'Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Gulbenkian Orchestra, and the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra. Last season, he played the complete violin sonatas of Robert Schumann with Amy Yang on period instruments at the Frick Collection, Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, and the Phillips Collection. He continues to tour his project Shifting Ground in collaboration with the new media artist Xuan, which intersperses works for solo violin by J.S. Bach with pieces by Matthew Burtner, Mario Davidovsky, Salina Fisher, Nicola Matteis, Angélica Negrón, and Paul Wiancko.

Alexi is a founding member of the quartet Owls—hailed as a “dream group” by The New York Times—alongside violist Ayane Kozasa, cellist Gabe Cabezas, and cellist-composer Paul Wiancko. He regularly performs at chamber music festivals including Caramoor, ChamberFest Cleveland, Chamber Music Northwest, La Jolla, Ojai, Marlboro, Music@Menlo, Ravinia, Seattle, and Spoleto. He is an alum of the Bowers Program at the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.

Born in Palo Alto, California in 1994, Alexi is a graduate of the New England Conservatory in Boston, where he studied with Donald Weilerstein and Miriam Fried. Previous teachers in the Bay Area include Wei He, Jenny Rudin, and Natasha Fong. He plays a violin made in London by Stefan-Peter Greiner in 2009 and a bow made in Port Townsend, WA by Charles Espey in 2024.

Outside of music, Alexi enjoys searching for great food and coffee, baking for friends, and walking for miles on end in whichever city he finds himself, and listening to podcasts and Bach on repeat.

PROGRAM

JEAN SIBELIUS

Violin Concerto in D Major, op.47

Allegro moderato Adagio de molto Allegro, ma non tanto

Alexi Kenney, Violin

INTERMISSION

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Symphony No. 1 in C minor, op.68

Un poco sostenuto; Allegro Andante sostenuto

Un poco allegretto e grazioso Adagio; Più andante; Allegro non troppo, ma con brio

FULL CONCERT UNDERWRITER

CONCERT SPONSORS-IN-PART

Dr. Thomas McCaffrey

Megan & David Van Winkle

REACH FOR THE STARS | ALEXI KENNEY

Allegra & James Derryberry

Violin Concerto in D Minor, op.47

JEAN SIBELIUS

Born 1865, Tavastehus, Finland

Died 1957, Järvenpää, Finland

Sibelius composed his Violin Concerto (his only concerto) in 1903, between his Second and Third symphonies. This was a time of transition for the 38-year-old composer, who was moving away from an early Romantic style influenced by Tchaikovsky and toward a leaner, more concise language. Sibelius was dissatisfied when he heard the concerto premiered in Helsinki in 1904 by Viktor Novácek, and he revised it completely. The final version was first performed in Berlin on October 19, 1905, with Karl Halir as soloist and Richard Strauss conducting.

It is difficult to characterize this haunting music. The second movement sings gracefully and the finale is full of energy, but the prevailing impression the concerto makes is of an icy brilliance. The orchestral sonority emphasizes the darker, lower voices—cellos, violas, and bassoons—so that the violin, which often plays high in its range, sounds even more brilliant by contrast. Sibelius was a violinist who had hoped to make a career as a soloist before he (fortunately) gave up that dream and turned to composition, and he fills the solo part with complex technical hurdles. Long passages played in octaves, great leaps, sustained writing in the violin’s highest register, and such knotty problems as trilling on one string while simultaneously playing a melodic line on another, make this one of the most difficult of all violin concertos.

The Allegro moderato opens with a quiet mist of string sound, and over this the solo violin presents the long, rhapsodic main theme: singing, dark, surging. Certain features of this theme—a triplet tag and a pattern of three descending notes—will assume important thematic functions as the movement develops. The originality of this movement appears in many ways. There are three main theme-groups instead of the expected two, but before we get to the second, Sibelius defies all expectations by giving the soloist a brief cadenza. The sober and steady second subject arrives in the dark sound of bassoons and cellos, while the vigorous third is stamped out by the violin sections. And then, another surprise: Sibelius presents the main cadenza, which is long and phenomenally difficult, before the development begins. Then the development and recapitulation are truncated, and the ending is abrupt: Sibelius drives with unremitting energy to the close, where the solo violin catapults to the top of its range as the orchestra seals off the cadence with fierce attacks.

Woodwind duets introduce the second movement before the violin enters with the intense main theme, played entirely on the G string. This movement, in ternary form, rises to a great climax and falls back to end quietly and gently. The tempo indication for the last movement, Allegro, ma non tanto (Fast, but not too fast), is crucial: Timpani and low strings set the steady tread that marches along firmly throughout much of this movement. The violin’s vigorous dotted melody dominates

this rondo, but even here the mood remains somber. This movement has been described in quite different ways. The English musicologist Donald Francis Tovey called it “a polonaise for polar bears,” while Sibelius is reported to have referred to it as a “danse macabre.” The concerto concludes as the violin climbs into its highest register and, with the entire orchestra, stamps out the concluding D.

C Minor, op.68

JOHANNES BRAHMS

Born 1833, Hamburg Died 1897, Vienna

Brahms waited a long time to write a symphony. He had impetuously begun one at age 23 in reaction to Schumann’s death, and he got much of it onto paper before he recognized that he was not ready to take on so daunting a challenge and abandoned it. Brahms was only too aware of the example of Beethoven’s nine symphonies and of the responsibility of any subsequent symphonist to be worthy of that example. To the conductor Hermann Levi, he made one of the most famous—and honest—confessions in the history of music: “You have no idea how the likes of us feel when we hear the tramp of a giant like him behind us.”

Brahms began work on what would be his first completed symphony in the early 1860s and worked on it right up to (and after) the premiere on November 4, 1876, when the composer was 43. He was concerned enough about how his first symphony would be received that he chose not to present it in Vienna, where all of

Beethoven’s symphonies had been first performed. Instead, he said, he wanted “a little town that has a good friend, a good conductor, and a good orchestra,” and so the premiere took place in the small city of Karlsruhe in western Germany, far from major music centers. Brahms may have been uncertain about his symphony, but audiences were not, and the new work was soon praised in terms that must have seemed heretical to its composer. Some began to speak of “the three B’s,” and the conductor Hans von Bülow referred to the work as “the Tenth Symphony,” suggesting that it was a worthy successor to Beethoven’s nine. Brahms would have none of it; he grumbled: “There are asses in Vienna who take me for a second Beethoven.”

There can be no doubt, however, that Brahms meant his First Symphony to be taken very seriously. From the first instant of the symphony, with its pounding timpani ostinato, one senses Brahms’ intention to write music of vast power and scope. The 37-bar introduction, which contains the shapes of the themes of the first movement, was written after Brahms had completed the rest of the movement, and it comes to a moment of repose before the exposition explodes with a crack. This is not music that one can easily sing. In fact, themes here are reduced virtually to fragments: arpeggiated chords, simple rising and falling scales. Brahms’ close friend Clara Schumann wrote in her diary after hearing the symphony: “I cannot disguise the fact that I am painfully disappointed; in spite

of its workmanship I feel it lacks melody.” But Brahms was not so much interested in melodic themes as he was in motivic themes with the capacity to evolve dramatically. After a violent development, the lengthy opening movement closes quietly in C major.

Where the first mov ement was unremittingly dramatic, the Andante sostenuto sings throughout. The strings’ glowing opening material contrasts nicely with the sound of the solo oboe, which has the poised second subject, and the movement concludes with the solo violin rising high above the rest of the orchestra, almost shimmering above the final chords. The third movement is not the huge scherzo one might have expected at this point. Instead, the aptly named Un poco allegretto e grazioso is the shortest movement of the symphony, and its calm is welcome before the intensity of the finale. It opens with a flowing melody for solo clarinet, which Brahms promptly inverts and repeats; the central episode is somewhat more animated, but the mood remains restrained throughout. That calm, however, is annihilated at the beginning of the finale. Tense violins outline what will later become the main theme of the movement, pizzicato figures race ahead, and the music builds to an eruption of sound. Out of that turbulence bursts the pealing sound of horns. Many have commented on the nearly exact resemblance between this horn theme and the Westminster chimes, though the resemblance appears to have been coincidental (Brahms himself likened it to the sound of an Alpenhorn resounding through mountain valleys). A chorale for brass leads to the movement’s main theme, a noble (and now very famous) melody for the first violins. When it was pointed out to Brahms that this theme bore more than a passing resemblance to the main theme of the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, he replied tartly: “Any ass can see that.” The point is not so much that the two ideas are alike thematically as it is that they are emotionally alike: Both have a natural simplicity and spiritual radiance that give the two movements a similar emotional effect. The development of the finale is as dramatic as that of the first movement, and at the climax the chorale is stamped out fortissimo as the symphony thunders to its close.

– Program Notes by Eric Bromberger

SVET STOYANOV, Marimba

Praised by The New York Times for his “understated but unmistakable virtuosity” and “winning combination of gentleness and fluidity,” Svet Stoyanov is a unique force in modern percussion. A winner of the Concert Artists Guild International Competition, he enjoys a multifaceted career as a performer, music producer, and educator.

Svet’s performing career highlights include concerto appearances with the Chicago, Seattle, and Houston symphony orchestras; The Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music, and many more, as well as solo performances at Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, the Kennedy Center, Verizon Hall, Shanghai Symphony Hall, and Taiwan National Concert Hall.

A passionate advocate for contemporary music, Svet Stoyanov has commissioned a significant body of works by composers, such as Mason Bates, Marcos Balter, Andy Akiho and many more. Recent highlights include Duo Duel, a double percussion concerto written by Pulitzer- and GRAMMY®-winning composer Jennifer Higdon. The concerto premiered with the Houston Symphony, conducted by Robert Spano. These performances were recorded live, and Duo Duel was released on a CD by NAXOS.

Svet’s next major commissioning initiative is a Concerto for Violin and Percussion—a first of its kind. This imaginative project is a consortium led by the Colorado Symphony and Peter Oundjian, with commissioning partners such as the Seattle Symphony, New York Youth Symphony and The Frost School of Music. The work will be written by Christopher Theofanidis and is scheduled for a world premiere and a recording in early 2026.

As a producer, Svet worked on numerous projects for The Cabrillo Festival of Contemporary Music during the virtual seasons of 2020 and 2021. Most recently, he produced and released the percussion masterworks Kyoto by John Psathas, and Water by Alejandro Viñao to great critical acclaim, as well as the album “Through Broken Time” by flutist Jennifer Grim, which was featured in The New York Times

Svet is a Professor of Percussion at the University of Miami’s Frost School of Music, where he has built one of today’s most innovative percussion programs, creatively bonding orchestral, solo and chamber music. Many of his students hold positions in prestigious arts institutions around the globe. Svet’s artistic mission is committed to the authenticity, virtue, and transformative power of music.

ROBERTO SIERRA

Sinfonía No. 7

Elegía

Cronos y El eterno ritorno De Profundis Clamavi Kairós y Apoteosis

EMMANUEL SÉJOURNÉ

Concerto for Marimba and Strings

Quarter-note = 69

Tempo souple Rhythmique. Energetique

Svet Stoyanov, Marimba

ANTONIN DVOŘÁK

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, op.95 “From the New World”

Adagio: Allegro molto Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Allegro con fuoco

MAXIMIANO VALDÉS , Guest Conductor

One of the most recognized Latin American conductors in the world, Maximiano Valdés has made a significant mark on the global music scene. Since 2008, he has served as Music Director and Principal Conductor of the Orquesta Sinfónica de Puerto Rico and as Artistic Director of the prestigious Festival Casals in San Juan since 2010. Valdés was Music Director of the Orquesta Sinfónica del Principado de Asturias in Spain for over 16 years and is now Conductor Laureate. He also led the Buffalo Philharmonic for more than a decade and has held leadership roles with Orquesta Euskadi in Spain, Orquesta Filarmónica de Santiago in Chile, and Orquesta Nacional de España.

Valdés developed his career in North America, leading major ensembles like the Philadelphia Orchestra, National Arts Centre Orchestra, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre symphonique de Montréal, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Seattle Symphony, Indianapolis Symphony, and Houston and Dallas Symphony Orchestras, among others.

His discography includes recordings with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Philharmonique de Monte-

Carlo. He also recorded a series of works by Latin American and Spanish composers with the Orquesta Sinfónica Simón Bolívar for Naxos. His recent CD offers works by Roberto Sierra with the Orquesta Sinfónica de Puerto Rico.

Sinfonía No. 7

ROBERTO SIERRA

Born 1953, Vega Baja, Puerto Rico

Roberto Sierra’s Seventh Symphony is his most recent. It premiered on June 1, 2024, at the Festival Casals by the Puerto Rico Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Maximiliano Valdés. Sierra has had a long and distinguished career as a composer. He trained first in his native Puerto Rico, then went on to study in Europe, some of that time spent as a student of György Ligeti in Hamburg. Sierra has had works commissioned and performed by almost all the leading American orchestras, and he has served as composer-in-residence with the Philadelphia Orchestra, Milwaukee Symphony, Puerto Rico Symphony, and New Mexico Symphony. Sierra’s music has been performed throughout the United States, and it has found international audiences as well: His works have been performed by orchestras in Europe, South America, and Asia. In 2010, Sierra was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2010, and in 2021 he retired from Cornell University after nearly 30 years on the faculty there. Sierra has composed prolifically in almost all musical forms: In addition to his seven symphonies, he has composed operas, choral and solo vocal works, chamber music, keyboard music

(for both piano and harpsichord), and 25 concertos for a variety of instruments.

The symphony is in four movements that span nearly half an hour. Each movement has a title (in Spanish, Latin, or Greek) that make clear that this symphony is the record of a spiritual journey. That journey is often troubled, but the arc of the symphony is from the static darkness of its beginning to the shining strength of its conclusion. The opening movement is marked Elegía , and Sierra stresses that the performance should be played con profuna expresión. We usually expect an elegy to be restrained and heartfelt, but this one is violent and full of tension. It bursts to life on great eruptions of sound that’s dramatic, discordant, and full of the large percussion section. A measure of relief comes in the violins’ quiet theme that yearns upward, but even this remains troubled. The movement alternates these two quite different impulses before coming to a subdued conclusion.

The second movement is titled Cronos y El eterno ritorno (Chronos and the Eternal Return). This is the symphony’s scherzo. Sierra marks it Movido (“active, restless, hectic”), and it rips past, again full of the sound of percussion and brass. The meter here is particularly interesting. The opening meter is 3+2 over 8, and the movement will dance wildly on that asymmetric pulse, but the meter changes constantly, jumping from that opening through 3/4, 2/4, and 6/8, but always returning to that uneven but very dynamic opening meter.

The conclusion is violent; Sierra’s marking is quadruple forte.

De Profundis Clamavi (Out of the Depths I Cry to You) is the symphony’s slow movement, but it is driven by the same tensions that animated the first two movements. The music builds to a great climax full of the sound of pealing brass calls, then falls away, and on quietly rippling harmonics from the violas and cellos, it concludes quietly.

The finale, titled Kairós y Apoteosis (Kairos and Apotheosis), is the longest movement. In Greek, kairos is a moment for decisive action. Sierra marks the tempo rápido , and the movement is in whirling motion throughout. The apotheosis this movement brings after the varying darkness of the first three movements is a wild excitement. The music may often be dissonant and frenetically violent, but it is also powerfully alive, and on an unending supply of white-hot energy, it powers its way to a shining close.

Concerto for Marimba and Strings EMMANUEL SÉJOURNÉ

Born 1961, Limoges, France

Emmanuel Séjourné studied at the Strasbourg Conservatory, where he specialized in mallet percussion and in new music, improvisation, and jazz. He received the gold medal for percussion there in 1980, when he was only 19. A virtuoso performer on marimba and vibraphone, Séjourné currently teaches at the Strasbourg Conservatory, where he is head of the percussion department. He has performe d in Europe, Asia, and North America, and he is also

a distinguished theorist: He has written a six-volume theory for mallet percussion as well as a book on his career as a percussionist. Séjourné has made numerous recordings, and he also gives master classes and serves as a judge at percussion competitions.

The Concerto for Marimba and Strings was commissioned by the International Marimba Competition in Linz just as that competition was established in 2006 (it is now situated in Salzburg). Séjourné wrote the piece specifically for the Austrian marimba player Bogdan Bacanu, who gave the first performance. As originally written, the concerto was in only two movements (the current second and third movements) but in 2015 Séjourné returned to it and wrote a new first movement, so the work is now in the standard three-movement concerto form. The concerto has proven extremely successful, with more than 800 performances.

Séjourné’s music has been described as “eclectic,” and his idiom here is romantic. The concerto is built on attractive themes, and he gives the soloist ample opportunity to shine. Séjourné takes care never to let the sometimes delicate sound of the marimba be overwhelmed by the string orchestra: He will often alternate passages for the orchestra with passages in which the soloist plays alone. The piece gets off to a vigorous start as the orchestra leads the way to the arrival of the soloist, who enters on a reflective solo. This movement pitches between different moods: It can be

inward, quick, melodic, or brilliant by turn, and it drives to a spirited close. The composer marks the central movement Supple tempo, and once again it is introduced by the strings, though this time their music is subdued. And again, the soloist makes an entrance with a solo cadenza of its own. Near the end, there are solos for violin, cello, and viola before the orchestra grows more animated, then breaks off for another extended solo passage for marimba. The finale, marked Rhythmic. Energetic , is built on sharply defined themes and rhythms. Some have heard the influence of flamenco music here, and even this movement’s quiet interludes are full of rhythmic energy. The energy level increases as we approach the end, and the concerto drives to an exciting conclusion.

Symphony No. 9 in E Minor, op.95 “From the New World” ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

Born 1841, Muhlhausen, Bohemia Died 1904, Prague

When Dvořák landed in America in the fall of 1892 to begin his three-year tenure as director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York, his new employers tried to turn his arrival into a specifically “American” occasion: They timed his arrival to coincide with the 440th anniversary of Columbus’ discovery of America, and the composer himself was to mark that occasion by writing a cantata on the poem The American Flag. Shortly after arriving, Dvořák announced his intention to write an opera on Longfellow’s Hiawatha, and soon “American” elements—

including Indian rhythms, spirituals, and a birdsong he heard in Iowa— began to appear in the music he wrote in this country.

These elements touched off a debate that has lasted a century. Nationalistic American observers claimed that here at last was a true American classical music, based on authentic American elements. But others have pointed out that the musical characteristics that make up these elements (pentatonic melodies, flatted sevenths, extra cadential accents) are in fact common to folk music everywhere, and that the works Dvořák composed in this country remain quintessentially Czech. Dvořák left contradictory signals on this matter. At the time of the premiere of the New World Symphony, he said: “The influence of America can be felt by anyone who has ‘a nose.’ ” Yet after his return to Europe, he wrote to a conductor who was preparing a performance in Berlin: “I am sending you Kretzschmar’s analysis of the symphony, but omit that nonsense about my having made use of ‘Indian’ and ‘American’ themes—that is a lie. I tried to write only in the spirit of those national American melodies.” Perhaps safest is Dvořák’s simple description of the symphony as “impressions and greetings from the New World.”

Composed in the first months of 1893, Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony had an absolutely triumphant premiere on December 16, 1893, by the New York Philharmonic in Carnegie Hall. One New York critic observed of the thunderous ovation that followed

each movement: “The staidness and solemn decorum of the Philharmonic audience took wings.” That occasion has been described as the greatest triumph of Dvořák’s life, and the surprised composer wrote to his publisher, Simrock: “I had to show my gratitude like a king from the box in which I sat. It made me think of Mascagni in Vienna (don’t laugh!)”

One of the most impressive aspects of this music is Dvořák’s use of a single theme-shape to unify the entire symphony. This shape, a rising dotted figure, first appears in the slow introduction, where it surges up in the horns and lower strings as a foreshadowing of the Allegro molto: There the shape is sounded in its purest form by the horns. This theme (actually in two parts, the horn call and a dotted response from the woodwinds) becomes the basis for the entire movement: When the perky second subject arrives in the winds, it is revealed as simply a variation of the second part of the main theme. The third theme, a calm flute melody in G major that has been compared to “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” seems at first to establish a separate identity, but in fact it is based on the rhythm of the main theme (although at a much slower tempo). That rhythm saturates the movement: within themes, as subtle accompaniment, or thundered out by the full orchestra. Dvořák drives the movement to a mighty conclusion that, pushed ahead by stinging trumpet calls, combines all these themes.

Solemn brass chords introduce the Largo, where the English horn sings

a haunting melody that was later adapted as the music for the spiritual “Goin’ Home.” More animated material appears along the way (and the symphony’s central theme rises up ominously at the climax), but the English horn returns to lead this movement to its close on an imaginative stroke of orchestration: a quiet chord built on a four-part division of the double basses. The Scherzo has sounded like “Indian” music to many listeners, and for good reason: Dvořák himself said that it “was suggested by the scene at the feast in Hiawatha where the Indians dance, and is also an essay I made in the direction of imparting the local color of Indian character to music.” The pounding opening section gives way to two brief trios, and in the coda the symphony’s central theme boils up one more time in the brass.

After a fiery introduction, the sonata-form finale leaps to life with a ringing brass theme that is, for a change, entirely new. But now Dvořák springs a series of surprises. Back come themes from the first three movements (there is even a quotation—doubtless unconscious—of “Three Blind Mice” along the way). The movement drives toward its climax on the chords that opened the Largo, and it reaches that soaring end as Dvořák ingeniously combines the main themes of the first movement and the finale. The composer has one final surprise: Instead of ringing out decisively, the last chord is held and fades into silence.

– Program Notes by Eric Bromberger

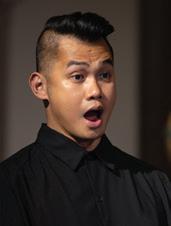

Sam Dhobhany, Bass-Baritone

Ryan BryceJohnson, Tenor

The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

Guillermo Figueroa, Music Director

Carmen Flórez-Mansi, Choral Director

Elisa Sunshine, Soprano

Gretchen Krupp, Mezzo-Soprano

Ryan Bryce Johnson, Tenor

Sam Dhobhany, Bass-Baritone

Paul J. Roth, Collaborative Piano

ElisaSunshine, Soprano

GretchenKrupp, Mezzo-Soprano

Saturday, November 22 & Sunday, November 23

7 pm & 4 pm | LENSIC

Sinfonia (overture)

Comfort ye (tenor recitative)

Every valley (tenor aria)

And the glory of the Lord (chorus)

Thus saith the Lord (bass recitative)

But who may abide the day of his coming (alto aria)

And He shall purify (chorus)

Behold, a virgin shall conceive (alto recitative)

O Thou that tellest good tidings to Zion (alto aria and chorus)

For behold, darkness shall cover the earth (bass recitative)

The people that walked in darkness (bass aria)

For unto us a child is born (chorus)

Pifa (“Pastoral Symphony”)

There were shepherds abiding in the field (soprano recitative)

And lo, the angel of the Lord (soprano recitative)

And the angel said unto them (soprano recitative)

And suddenly there was with the angel (soprano recitative)

Glory to God (chorus)

Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion (soprano aria)

Then shall the eyes of the blind be opened (alto recitative)

He shall feed His flock like a shepherd (soprano and alto duet)

His yoke is easy, and His burden is light (chorus)

INTERMISSION

PART II

Behold the Lamb of God (chorus)

He was despised (alto aria)

Surely He hath borne our griefs (chorus)

And with His Stripes we are healed (chorus)

All we like sheep have gone astray (chorus)

All they that see him (tenor recitative)

He trusted in God (chorus)

Thy rebuke hath broken His heart (tenor recitative)

Behold and see (tenor aria)

He was cut off (tenor recitative)

But Thou didst not leave His soul in Hell (tenor aria)

Why do the nations so furiously rage together? (bass aria)

Let us break their bonds asunder (chorus)

He that dwelleth in heaven (tenor recitative)

Thou shalt break them (tenor aria)

Hallelujah (chorus)

I know that my Redeemer livith (soprano aria)

Since by man came death (chorus)

Behold, I tell you a mystery (bass recitative)

The trumpet shall sound (bass aria)

Then shall be brought to pass (alto recitative)

O death, where is thy sting? (alto and tenor duet)

But thanks be to God (chorus)

Worthy is the Lamb that was slain (chorus)

Amen (chorus)

FULL CONCERT SPONSOR

CONCERT SPONSORS IN-PART

Kathryn O’Keeffe Charitable Foundation

GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL

Born 1685, Halle, Germany

Died 1759, London

In 1741, when George Frideric Handel was asked to compose and present a series of concerts in Ireland to benefit local charities, his music had become less fashionable and his financial straits dire. This fortuitous invitation was issued by William Cavendish, Duke of Devonshire and Lord Lieutenant of Dublin. It culminated in the first public presentations of the now-famous Messiah . Before leaving London for Ireland that fall, Handel composed the work in a mere 24 days, completing it on September 14.

Handel knew little about the quality, disposition or experience of the performers with whom he’d be working. Therefore, when he arrived in Dublin in November 1741, he changed the work to suit the particular abilities of his cast, and he continued to do so every time it was performed. Sometimes he changed things slightly, transposing an aria from one key to another to fit the range of the singer. Other times, he reassigned arias to different voices either because he had a different mix of soloists or because there was a guest star he wanted to feature. Sometimes he recomposed movements altogether. There are at least 10 different arrangements of the score, with 15 individual movements existing in more than 40 versions. In addition to the choral parts, Messiah is scored for oboes, bassoons, trumpets, strings, harpsichord, and timpani.

Handel presented 12 concerts in Dublin before unveiling Messiah on April 13, 1742, in the New Musick-Hall. The normal capacity was 600 people, but the Dublin Journal reported a crowd of at least 700. Such was the excitement about the new work that a Journal article admonished women to “come without hoops” and men to “come without swords” so that more people could be crammed in.

The event was an artistic and financial success, earning great reviews and making it possible for 142 people to be released from debtors’ prison. Handel waited a year before presenting Messiah in London. Seven years later, in 1750, he had the idea to perform the oratorio as a fundraiser for the Foundling Hospital. Annual performances have continued in London and around the world ever since. The Hospital still owns Handel’s autographed score and performance notes, which he left to the institution upon his death.

Messiah marked the beginning of a resurgence in Handel’s career; when he died in 1759, he was able to leave a substantial legacy to a niece, friends, servants, and various charities in England.

– Program Note by Tom Hall

ELISA SUNSHINE , Soprano

Celebrated for her “blend of vocal sparkle and theatrical charisma” by the San Francisco Chronicle, American soprano Elisa Sunshine is a recent graduate of San Francisco Opera’s Adler Fellowship, which brings the complexity of the human experience to life through vocal acrobatics and theatrical dynamism. She joined The Santa Fe Opera as an Apprentice Artist in 2024, making her company debut as Annina in La Traviata and covering Sheila in the world premiere of Gregory Spears’ and Tracy K. Smith's The Righteous. In the 20242025 season, Elisa made noteworthy debuts with The Atlanta Opera as Iris in Semele and Boston Symphony Orchestra as Juliette in Die tote Stadt. She returned to The Santa Fe Opera in summer 2025 as Waltraute in Die Walküre.

Elisa has covered Marie in La fille du régiment, Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro, and Gilda in Rigoletto in previous collaborations with the Lyric Opera of Chicago. She returned to San Francisco Opera for its centennial celebration as part of Richard Strauss’ masterpiece Die Frau ohne Schatten under the baton of Sir Donald Runnicles. During her time as an Adler Fellow, she made her San Francisco Opera debut as the Shepherd boy in Tosca, sang Annina in La Traviata, and sang Soeur Anne de la Croix and covered Constance in Dialogues des Carmèlites.

GRETCHEN KRUPP, Mezzo-Soprano

Acclaimed for her “show-stopping,” “ripe, round,” and “searing” voice, Gretchen Krupp is rapidly establishing herself as a magnetic force in the opera world, distinguished by her extraordinary vocalism and compelling theatricality. Her diverse repertoire spans centuries and styles, from classic to contemporary, dramatic to comic.

In the last two seasons, Gretchen has made her debut with the York Symphony Orchestra in Verdi’s Messa da Requiem, returned to the Santa Fe Opera to sing Waltraute and cover Fricka in the new production of Die Walküre, performed with The Dallas Opera for the premiere of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly as well as their production of Elektra, performed as Mary in Der fliegende Holländer at Pittsburgh Opera, and as Fricka in Die Walküre with The Atlanta Opera.

Gretchen was named a 2018 Grand Finalist in the Eric and Dominique Laffont Competition and a Finalist in the 29th Annual Eleanor McCollum Competition for Young Singers. She is a proud alumna of prestigious young artist programs at the Santa Fe Opera, Wolf Trap Opera, The Glimmerglass Festival, Des Moines Metro Opera, and Dolora Zajick’s Institute for Young Dramatic Voices.

Tenor Ryan Bryce Johnson is a dynamic and versatile performer whose work spans both opera and musical theatre. In 2025, he returned to The Santa Fe Opera for the role of Borsa in Rigoletto. During the 2024 season with the company, he made his debut as Giuseppe in La traviata, and appeared as Faninal’s Major-Domo in Der Rosenkavalier, and Prunier in La rondine.

In 2023, Ryan was featured at The Glimmerglass Festival as the Grand Inquisitor and Governor in Bernstein’s Candide. At Opera Theatre of Saint Louis, he has performed Borsa in Rigoletto, Frederic in The Pirates of Penzance, Remendado in Carmen, and Nurse Rodriguez in Awakenings.

He is the 2023 First Prize Winner of the Lotte Lenya Competition, a 2024 district winner of The Metropolitan Opera Eric and Dominique Laffont Competition, and a finalist in the George London Foundation Competition.

Ryan holds a Master of Music in Vocal Performance and Literature from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a Bachelor of Music in Vocal Performance from Texas Tech University. He has trained as an Apprentice Singer at The Santa Fe Opera, a Young Artist at The Glimmerglass Festival, and a Gerdine Young Artist at Opera Theatre of Saint Louis.

SAM DHOBHANY, Bass-Baritone

Second-year Houston Grand Opera Butler

Studio artist Sam Dhobhany, originally from Brooklyn, New York, received the Ana María Martínez Encouragement Award at HGO’s 2024 Eleanor McCollum Competition Concert of Arias. He is a 2022 alumnus of HGO’s Young Artist Vocal Academy. During the 2024-25 season at HGO, he made his company debut as Alidoro in HGO Family Day’s Cinderella and performed the role of Terry in Breaking the Waves. In summer 2024, he returned to Santa Fe Opera as an apprentice artist, where his roles included Marchese d’Obigny in La traviata, as well as covering Dulcamara in The Elixir of Love and The Notary in Der Rosenkavalier. Previously, with Santa Fe Opera in 2023, he covered and performed the role of Un Médecin in Pelléas et Mélisande.

Last summer, Sam was a Filene Artist at Wolf Trap Opera, where he appeared as Bartolo in Le Nozze di Figaro and Zuniga in Carmen. He was a second-place winner in the Rocky Mountain Region of The Metropolitan Opera Laffont Competition. This season at HGO, he is tackling a variety of repertoire, including the roles of Undertaker in Porgy and Bess, The Notary in Gianni Schicchi, British Major in Silent Night, George in Of Mice and Men, and The Officer in The Barber of Seville. He holds a Bachelor of Music degree in Vocal Performance from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra

Guillermo Figueroa, Music Director

The Santa Fe Youth Symphony Orchestra

William Waag, Youth Symphony Conductor

Maya Mueller, Clarinet

2025 Concerto Competition Winner, Senior Division

Laurie Rossi, Guest Conductor

Georgia McGaughey Nicholls, Guest Conductor

PROGRAM

PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY

Selections from The Nutcracker Suite

March

Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy Waltz of the Flowers Trepak

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Concerto in A Major for Clarinet and Orchestra, K.622

Allegro

Maya Mueller, Clarinet Winner of the 2025 Concerto Competition, Senior Division

MEL TORME

The Christmas Song

MODEST MUSSORGSKY

Pictures at an Exhibition

The Great Gate of Kiev

Side-by-Side with The Santa Fe Youth Symphony

INTERMISSION

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture

Laurie Rossi, Guest Conductor

Sunday, December 7 4 pm |

JAMES M. STEPHENSON

A Charleston Christmas

arr. LUCAS RICHMAN

Hanukkah Festival Overture

LEROY ANDERSON Sleigh Ride

Georgia McGaughey Nicholls, Guest Conductor

JAMES M. STEPHENSON

Holly and Jolly Sing-A-Long

Carmen Florez-Mansi, Choral Director

FULL CONCERT SPONSOR

Margaret & Barry Lyerly

CONCERT SPONSORS-IN-PART

Kay & Neel Storr, Storr Family Endowment Fund

The Nutcracker Suite

Born 1840, Votkinsk

Died 1893, St. Petersburg

In 1891, the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg approached Tchaikovsky with a commission for a new ballet. They caught him at a bad moment: At age 50, Tchaikovsky was assailed by worries that he had written himself out as a composer, and—to make matters worse—they proposed a storyline that the composer found unappealing: They wanted to create a ballet based on the E.T.A. Hoffmann tale Nussknacker und Mausekönig, but in a version that had been retold by Alexandre Dumas as Histoire d’un casse-noisette , and then further modified by the choreographer Marius Petipa. This sort of Christmas fairy tale, full of imaginary creatures set in a confectionary dream-world of childhood fantasies, left Tchaikovsky cold, but he nonetheless accepted the commission.

Sidetracked by his American tour and his sister’s death, Tchaikovsky tried to resume work on the ballet when he returned to Russia. To his brother, he wrote: “The ballet is infinitely worse than The Sleeping Beauty so much is certain.” The score was completed in the spring of 1892, and The Nutcracker was produced at the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg that December, only 11 months before the composer’s death at 53. At first, it had only modest success, but then its popularity grew so steadily that Tchaikovsky reassessed what he had created: “It is curious that all the time I was writing the

ballet I thought it was rather poor, and that when I began my opera [Iolanthe] I would really do my best,” he wrote. “But now it seems to me that the ballet is good, and the opera is mediocre.”

Tchaikovsky could have had no idea just how popular The Nutcracker would become: It has become an inescapable part of our sense of Christmas. This concert offers a selection of movements from the ballet, largely characteristic dances. March (also known as March of the Toy Soldiers) plays during a lively party scene, which includes dancing, games, and merriment. Dance of the Sugarplum Fairy is an elegant and dreamlike performance by a solo ballerina, while the fiery Russian Dance (also called Trepak) is a wild Cossack dance, while La mère Gigogne (roughly equivalent to The Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe, and also called Mother Ginger and her Children) features dancing clowns. Tchaikovsky, who was an admirer of Johann Strauss, loved waltzes, and this selection includes one of his finest, The Waltz of the Flowers from Act II.

– Program Note by Eric Bromberger

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Born 1756, Salzburg

Died 1791, Vienna

The second half of 1791 seemed, at least on the face of it, a promising time for Mozart. After several years of diminished popularity and income in Vienna, he suddenly found his music much in demand.

He composed La clemenza di Tito as a commission for the coronation of Leopold II as King of Bohemia, followed by his completion of The Magic Flute and working on the Requiem Mass. Despite brief periods of illness, Mozart’s prospects seemed very bright.

It was during the first week of the heady success of The Magic Flute that Mozart composed his Clarinet Concerto; it would be his final masterpiece and his last completed work before his death, eight weeks short of his 36th birthday. During his first years in Vienna, Mozart had become friends with Anton Stadler (1753-1812), a fellow Freemason and a virtuoso clarinetist. He wrote three great works for Stadler that feature the clarinet: the Clarinet Trio (1786), the Clarinet Quintet (1789), and the Concerto. Stadler played the basset clarinet, an instrument of his own invention, which could play four pitches lower than the standard clarinet of Mozart’s day. That meant Mozart’s clarinet works could not be played on the contemporary clarinet, so they had to be rewritten to suit the range of that instrument. Subsequent modifications have given the modern A clarinet those four low pitches, and today we hear these works in the key in which Mozart originally intended them.

Mozart completed the Clarinet Concerto on October 7th, only 59 days before his death. It is of course tempting to make out premonitions of death in Mozart’s final instrumental work, and many have been unable to resist that temptation, but such conclusions must remain subjective.

What we can hear in the Clarinet Concerto is some of the most graceful, noble, and moving music Mozart ever wrote. This is not a concerto that sets out to dazzle a listener’s ears with a soloist’s fiery technique (it has no cadenza) but rather music that, through its endless beauty, engages a listener’s heart. Mozart’s subdued orchestration (pairs of flutes, bassoons, and horns, plus strings) produces a smooth, warm, and understated sonority, ideal to accompany the clarinet and ideal for the restraint of the music itself. Mozart often has the first and second violins playing in unison, further purifying the sound of the orchestra.

At nearly half an hour, this piece is longer than almost all of Mozart’s other concertos. But its length brings with it a spaciousness that is very much a part of this music’s character. The opening Allegro establishes the concerto’s spirit immediately with its calm and lyrical opening idea. Solo clarinet takes up this theme at its entrance, and the soloist also has the graceful, arching second theme, a theme that—rather than contrasting sharply with the opening—remains very much within that same character. This may be a sonata-form movement, but it is one without conflict. Instead, it is endlessly graceful and expressive music, beautifully written for the clarinet.

The emotional center of this concerto is the Adagio. It is in this movement that one feels most strongly the concerto’s compelling combination of surface restraint and emotional depth; if one needs to make out premonitions of Mozart’s death, this movement’s intensity

and spi rit of gentle resignation offer the place to look. The opening measures bring some of the most expressive Mozart music ever wrote, as the smooth sound of the clarinet rises and falls above the strings’ murmuring accompaniment. Near the end the music rises to a climax, but it is an emotional rather than a dramatic climax (Mozart’s marking is only forte), and the music slips into silence.

The concluding rondo-finale dances and turns cheerfully along its 6/8 meter. The clarinet has wide skips and long, athletic runs throughout its range here, but even more impressive are the interludes between the return of the rondo theme, many of them beautifully shaded and hauntingly expressive.

– Program Note by Eric Bromberger

Pictures at an Exhibition MODEST MUSSORGSKY

Born: 1839 Karevo, Russia

Died: 1881, Saint Petersburg

Pictures at an Exhibition, particularly its final movement, is widely considered one of Modest Mussorgsky’s (18391881) greatest works. He wrote the suite in three weeks’ time and dedicated it to Vladimir Stasov, a major figure on the Russian art scene in the late 19th century. The composition is Mussorgsky’s response to a display of Viktor Hartmann’s work at the Imperial Academy of Art.

Hartmann (1834-1873) was an artist and architect who met the composer between 1868 and 1870. The two became close friends immediately,

largely due to their shared passion for creating Russian art that was rooted in Russian culture rather than in European traditions. Hartmann died suddenly of a brain aneurysm at age 39. The Russian art world was in shock, no one perhaps more so than Mussorgsky.

Hartmann’s friends organized an exhibition of 400 of the artist’s paintings, architectural drawings, and other works. Pictures at an Exhibition illustrates, musically, 10 of those illustrations. For many, it is the most well-known example of 19thcentury program music—music that tells a story while, at the same time, depicts it sonically. The 10-movement suite includes the sounds of chickens, children, peasant carts moving through the mud, and more. Listeners are guided throughout the museum with sudden contrasts between movements as well as a few moments of reflection, not unlike if you were walking through a museum.

Originally written for solo piano, Maurice Ravel orchestrated Pictures in 1922, creating the edition most audiences have come to know and love.

The Promenade, which introduces the work, provides continuity between movements much like a hallway connects galleries in a museum; indeed, that was how the composer intended it to be heard. It also provides the underlying musical material for the final movement —

The Great Gate of Kiev, known more formally in Ukraine as The Bogarty Gates or “Gate of Heroes at Kiev.”

For the exhibition that inspired Mussorgsky’s Pictures , Hartmann designed this Ukranian landmark in the “massive” Russian style, tall thick walls with a cupola shaped like a Slavonic helmet. His design was to commemorate the bravery of Tsar Alexander II’s men as they helped the monarch narrowly escape assassination, April 4, 1866.

While Hartmann’s designs for the gate in Kiev never materialized, Mussorgsky majestically depicted the grandeur he saw in Hartmann’s designs. For The Great Gate , the composer once again brings back the Promenade’s opening trumpet solo followed by brass choir, now retooled to showcase the tall, dense walls of the gate Hartmann proposed in his designs. The opening melody is now played by the entire brass section. Once the full orchestra joins in, the effect is a massive wall of sound, splendid and impressive, much as Hartmann’s Imperial Gate would have signaled to visitors arriving at the walled city of Kiev that they were about to enter a special place, one that was of great significance in the Imperial Russian Empire.

The Great Gate of Kiev is one of six portraits from the exhibition that Mussorgsky owned. By preserving it in sound and by expressing the emotions portrayed in Hartmann’s watercolors of life in 19th-century Italy, France, Poland, Russia and Ukraine, Mussorgsky shares with modern listeners a world now lost to war and the passing of time.

In the fall of 1954, the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra needed a new work to celebrate the October Revolution for a concert that was to take place in three days time. Shostakovich agreed to write something and immediately set to work.

As his friend Lev Lebedinsky related: “The speed with which he wrote was truly astounding. When he wrote light music he was able to talk, make jokes and compose simultaneously, like the legendary Mozart. He laughed and chuckled, and in the meanwhile, work was underway and the music was being written down.”

This commission — made at the peak of Stalin's power — challenged the composer's reputation for producing high quality work "while you wait." There are varying stories about its composition — that Shostakovich locked himself in a room and passed pages under his door to copyists waiting outside to make parts for the players or that, as Lebedinsky recalled, the composer laughed and made jokes as he dashed off the main themes like he’d had it in his head all along. Whatever really happened, one thing is clear. The chaos and panic happening behind the scenes at the Bolshoi is simply not present in the work. Shostakovich's Festive Overture flows naturally to the ear; it is full of good humor, yet polished, energetic, and truly festive.

Many listeners recognize this work from an unlikely source: television. Five years after Shostakovich’s death, it was the musical theme of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow.

– Program Notes by Elisabet de Vallée

WAAG

Over the course of Director of Youth Orchestras William Waag’s career in music education, he has taught and conducted groups in Albuquerque, Seattle, El Paso, and Anchorage. A native of Boise, he’s led ensembles and classes in elementary schools as well as at the college level, but his true passion is working with young musicians, helping them develop and hone their skills.

Professionally, William plays the trombone, but you probably know him best as a conductor. In addition to leading The Symphony’s top two youth orchestras, he is on the podium with two groups for adults— the Santa Fe Community Orchestra and the Los Alamos Symphony.

William is busy signing up students for the Youth Symphony’s new season. If you’ve not registered your child for private lessons, ensembles or other music classes, William says to give him a call. He’d love to help you get your budding musician enrolled in whatever sessions are the right fit for your student.

Maya Mueller is a clarinetist currently pursuing her Master of Music degree at the Manhattan School of Music. She recently graduated from Vanderbilt University with a Bachelor of Music in Clarinet Performance. Originally from Rio Rancho, New Mexico, Maya is proud to represent her home state in this performance. She is especially grateful to her high school band director, Daniel Holmes of Cleveland High School, as well as her early instructors Michael Herrera and Michael Gruetzner, for their foundational support and encouragement throughout her musical development. She was also a dedicated member of the Albuquerque Youth Symphony for four years.

At the Imani Winds Chamber Music Festival in New York, she performed at Lincoln Center. At the Zodiac Music Academy & Festival in France, Maya premiered a student composition and performed in historic venues. She also held principal roles at the Eastern Music Festival in North

Deeply committed to making music more accessible, Maya has taught in underserved communities across the U.S. and abroad. Her outreach includes volunteer teaching through the W.O. Smith Music School in Nashville, the Banda Sinfónica Integrada de las Américas in Colombia, and the Daraja Music Initiative in Tanzania.

Curated by Artistic Director and Violinist Colin Jacobsen

“Armed with vision, courage, a sense of humor and a devastating bow arm, Jacobsen is emerging as one of the most interesting figures on the classical music scene.”

(The Washington Post)

GRAMMY-nominated Orchestra

Renowned String Quartets

The Southwest’s Premier Bach Festival

Nosotros, the award-winning Latin band known for its socially conscious music, has been drawing music lovers to its distinctive Latin groove for nearly three decades. What began as a guitar trio in 1994 quickly took on a life of its own, becoming something that no one could have predicted, including becoming one of the most recognizable and original Latin bands in the Southwest United States.

The band’s remarkable evolution over the years—taking on new members and leadership along the way—has resulted in the 10-piece Latin music powerhouse it is today. The group seamlessly combines a myriad of rhythms—cumbia, bolero, salsa, chica— with elements of rock, jazz, and beyond, creating an innovative and imaginative Latin sound that is unique, undefinable and unmistakably Nosotros.

Nosotros continues to this day to astound audiences wherever they perform. They have become festival favorites and have shared stages with the likes of Etta James, Gypsy Kings, Los Lobos, The Wailers, Roy Hargrove, Los Lonely Boys, Robert Mirabal, Joan Osborne, Ozomatli, Las Cafeteras, Flor de Toloache, Grupo Fantasma, Victor Wooten, Dave Mason, Making Movies and many more. And, importantly, their new music continues to be relevant, reflecting our ever-changing world. It also continues to be vibrant, fun and, yes, undefinable.

THOMAS HEUSER

American conductor

Thomas Heuser serves as Music Director of the San Juan Symphony and the Idaho Falls Symphony. He was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship for Orchestral Conducting while serving as a Conducting Fellow with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. Dr. Heuser holds degrees in music from Vassar College, Indiana University, and the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music.

MUSIC BY NOSOTROS

Arranged for orchestra by Micah J. Hood

El Perseguido

Mama Tierra Hermosa Olvidarme Érase Una Vez Quemazón Esperanza

INTERMISSION

Aqui y Allá En El Más Allá Mentiras Siempre Seguimos Eres Tu Quien Escojo Amor Sincero

The Santa Fe Symphony Orchestra & Chorus

Overture and Chorus of The Priests from The Magic Flute, K.620

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Born 1756, Salzburg

Died 1791, Vienna

As he often did, Mozart delayed writing the overture to The Magic Flute until almost the last minute: The premiere took place in Vienna on September 30, 1791, and Mozart wrote the overture on the 28th. Curiously, though Mozart was pressed for time, he did not base the overture on themes from the opera (his frequent practice) but instead wrote one using entirely new material. The only part of the opera that appears in the overture are three solemn chords. Three was a number with mystical meaning in Masonic ritual (the overture is in E-flat major, a key with three flats), and in the opera those chords herald the beginning of Sarastro’s ritual initiation of Tamino in Act II. These three massive chords, solemnly intoned by the full orchestra (an orchestra that includes three trombones), open the overture’s brief introduction, setting the tone for the opera’s high moral message. But at the Allegro, the music bursts forward suddenly, establishing the mood of sparkling fun that is also so much a part of The Magic Flute. The overture is in sonata form, and the exposition begins as a fugue, introduced by the second violins. Mozart will use this fugal opening as the first theme group; the second, the simplest of lyric figures, arrives in the solo woodwinds. And then a surprise: Mozart brings matters to a complete halt at the end of the exposition with a return of the three solemn chords from the overture’s beginning. The development begins in minor-key urgency, pressing ahead on the fugal material. The overture drives to a great climax and, riding along the splendid sound of timpani and the large brass section, comes to a ringing close, having established perfectly the mood for the action that will follow.

In the second act, the hero Tamino and his comic sidekick, the birdcatcher Papageno, must undergo a series of trials to determine if they are worthy of being received into the fellowship of Isis and Osiris. Papageno of course fails completely (but is rewarded with a beautiful young wife), while Tamino endures and is reunited with his love, Pamina. In the course of Tamino’s trials, he is observed by a chorus of priests, who sing optimistically yet solemnly to the gods Isis and Osiris about his progress toward enlightenment: He is bold, he is pure; soon he will be worthy of us.

PROGRAM

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

Overture and “Chorus of the Priests” from The Magic Flute

GIUSEPPE VERDI

“Va, Pensiero” from Nabucco

“The Anvil Chorus” from Il Trovatore

GEORGES BIZET

Prelude, “Aragonaise,” Intermezzo, and “March of the Toreadors” from Carmen

RICHARD WAGNER

“Bridal Chorus” from Lohengrin

“Entry of the Guests” from Tannhäuser

INTERMISSION

RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO

Intermezzo and “Bell Chorus” from I Pagliacci

GIOACHINO ROSSINI

Overture to The Barber of Seville

ALEXANDER BORODIN

“Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor

FULL CONCERT SPONSOR

Katherine & William Landschulz

CONCERT SPONSORS-IN-PART

Bernard Ewell & Sali Randel

Ralph Craviso

Elizabeth & James Roghair

“Va, pensiero” from Nabucco

GIUSEPPE VERDI

Born 1813, Roncole

Died 1801, Milan

Nabucco was Verdi’s first success. Composed in 1842, when the 29-yearold composer had just endured some crushing failures and was on the verge of giving up composing, Nabucco proved so successful that it was given 57 times during the following season, and within 10 years it had been produced throughout Europe and as far away as New York and Buenos Aires. The opera tells of Nebuchadnezzar’s capture of Jerusalem and of the plight of the Jews in their Babylonian captivity. (The Italian word for Nebuchadnezzar is the unwieldy and almost unsingable Nabucodonosor, and so Verdi and his librettist Temistocle Solera shortened it to Nabucco. ) The opera is remarkable for its dramatic use of the chorus, which has some of the best music in the opera.

The opera’s most famous music, the chorus Va, pensiero, is sung by the Jews during their Babylonian captivity in Part 3. Its first lines set the tone of nostalgic longing that have made it so popular:

Fly, thought, on golden wings; rest upon the slopes and hills, where, soft and mild, the air of our native land smells sweet!

“Anvil Chorus” from Il Trovatore

GIUSEPPE VERDI

Born 1813, Roncole

Died 1801, Milan

First performed in Rome in 1853, Il Trovatore has become one of the most famous operas ever composed, despite (or perhaps because of) its really horrifying events, such as a woman and babies burned to death, false imprisonment, bloody revenge, and some spectacular cases of mistaken identity gone tragically wrong. The Anvil Chorus, one of the opera’s most famous moments, comes at the beginning of Act II. A group of gypsies stirs to life as dawn breaks on their encampment in the mountains of Spain, and as the day brightens they sing this lusty chorus in praise of wine, hard work, and the beauty of gypsy women. The men start fires, heat sword blades, and pound them with hammers as they sing, and a nice feature of Verdi’s setting is the fact that the clink of their hammers comes on the off-beat rather than the downbeat. The tune of that chorus has taken on a life of its own, from its use in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Pirates of Penzance to becoming the tune of the American popular song “Hail! Hail! The gang’s all here.”

Prelude, “Aragonaise,” Intermezzo, and “March of the Toreadors” from Carmen GEORGES BIZET

Born 1838, Paris

Died 1875, Bougival, France