108 minute read

CHAPTER SIX Remnants: Memories of Life in War

from Neshama: Inspiration for Such a Time as This: A Collection of Stories, Recipes, Poems and Other

Remnants: Memories of Life in War Воспоминания, живущие во время войны

Semyon Belkin, Military Destinies of One Large Family Valentina Belkina, Looking at the Photograph

Advertisement

Emilia Brodskaya, Leningrad Apartment

Leonid Bruk, Leningrad Evacuates Children

Ludmila Dakhia, Childhood Memories

Azik Goldovskiy, The Secret Galoshes

Tamara Gribach, The Delight of Fresh Air

Mark Kresin, My Wife, Zina

Yefim Milinevsky, Evacuation to Uzbekistan Zalman Polott, Memory!

Natalia Ptitsyna, Turquoise Vase

Grigoriy Sapozhnikov, Thanks to My Father

Alexander Tulchinsky, Notes of A Natural Israelite

Abram Vizhansky, Orphanage Khana Zartdinova, Hunger & Refuge in an Abandoned Village

Edward Zhitomirsky, First Day of War

Uli Zislin, Evacuation: Novosibirsk Household Memories

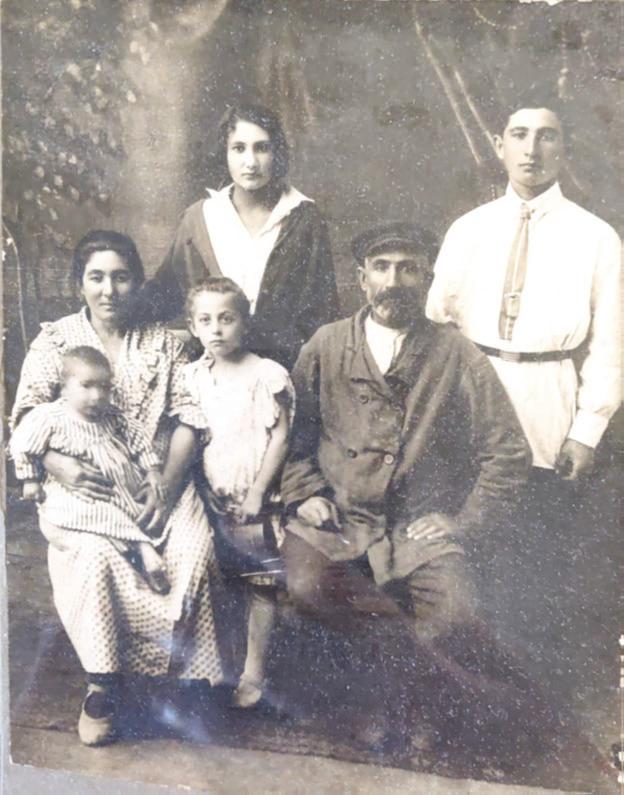

Передо мной старая фотография, одна из тех, какие есть, наверное, в каждой патриархальной семье. Этот снимок был сделан, видимо, где-то в конце двадцатых годов минувшего века, когда меня еще и в помине не было, в доме моего деда Мойше и бабушки Стыси, в маленьком чисто еврейском городке Речица, недалеко от Гомеля. В центре фотографии – хозяин дома, известный дамский портной Мойше Белкин, рядом с ним- его верная жена Стыся, которая родила ему девять детей, но на фотографии их только семь: пять дочек и два сына. Один из сыновей умер во младенчестве, а один еще до революции эмигрировал в Америку. Слева и справа от родителей на фотографии – четыре замужних дочери: Песя, Фрейда, Тайба (она же Таня) и Рива. Позади каждой дочери стоит ее муж, а непосредственно за дедом и бабушкой – трое холостяков: мой будущий отец Исаак, дядя Абрам и тетя Лиза, тоже пока незамужняя.

А на переднем плане прямо на полу в живописном беспорядке расположилась молодая поросль. С грустью вглядываюсь я в лица этих малышей. Вот слева сидит карапуз в бархатном костюмчике и с бантиком на шее. Это Яша, который прошел всю войну простым солдатом, и дошел до Берлина. Справа – два стриженых «под нуль» лопоухих мальчика. Один из них Додик, который со школьных лет проявил себя как талантливый поэт, печатался в газетах и журналах, в 18 лет добровольцем пошел на фронт, писал с передовой трогательные патриотические стихи и очень скоро погиб. Его брата Хацкеля долго не брали в армию изза плохого зрения, тем не менее где-то в 1943 году он уже был на передовой, где получил тяжелое ранение: пуля прошла через челюсть и застряла в руке. По воспоминаниям моей кузины Цины, когда Хацкель вернулся домой после всех госпиталей, на него было страшно смотреть: через всю нижнюю челюсть проходил уродливый рубец, во рту - ни одного зуба, правая рука висела как плеть. От плеча до локтя не было кости, и этот тоненький обрубок был весь в рубцах. Как выяснилось много лет спустя, Хацкель буквально воскрес из мертвых: он лежал братской могиле, которую уже собирались закапывать, когда один из бойцов услышал слабый стон. Хацкеля вытащили из ямы и отправили в госпиталь. После многих месяцев лечения он вернулся матери, которая, потеряв одного сына, уже отчаялась увидеть второго сына живым. Впоследствии он станет доктором физических наук, профессором, действительным членом Академии наук. Он ушел из жизни в возрасте 75 лет, окруженный

почетом и славой. Старший из сидящих на полу детей Ида в самом начале войны пропадет без вести. По слухам он был осужден и закончил жизнь в одном из советских лагерей.

В эвакуации, в далеком Узбекистане умерли с интервалом в два дня дедушка и бабушка. А они были здоровыми, крепкими, и если бы не война, они могли бы еще жить и жить. Из четырех семейных пар папиных сестер, изображенных на фото, не осталось ни одной: в годы войны один из супругов умер или погиб.

Смерть или тяжелые ранения не миновали и внуков. Я уже рассказал о гибели 18-летнего Додика. Страшно сложилась судьбы моей тети красавицы Фрейды и ее 13-летней дочери Хаюси (на фотографии они сидят во втором ряду: тетя с маленькой дочкой на руках). Накануне войны они жили с мужем - офицером в Белостоке на самой границе с Польшей и проснулись 22 июня 1941 года уже на оккупированной территории. Более года их скрывали от немцев, а потом кто-то их выдал, Фрейду и Хаюсю вывели в гетто, а потом расстреляли. Оля, старшая дочь Фрейды, уже студентка (на снимке она, тогда еще подросток, сидит на полу в матроске), пешком, через леса, прошла огромное расстояние, добралась из Белостока до Речицы, в дом своего дедушки и бабушки, и оттуда добровольцем пошла в действующую армию. Тяжелую контузию получил на фронте мой отец, подполковник И. М. Белкин, и последствия этой контузии сказывались до самого конца его жизни. Большой воинский путь прошел мой дядя Абрам, который всю войну был в действующей армии, дослужился до подполковника и достойно дошел до Берлина.

Полную чашу голода, холода, бомбежек и прочих испытаний военных лет испила моя кузина Цина, которую мы видим на фотографии на руках у папы в третьем ряду. Была многоступенчатая эвакуация: сначала по Днепру на пароходе, потом на поезде в Моздок, затем в Махач-Калу, далее пароходом до Баку и другим пароходом через Каспий в Красноводск и оттуда уже на поезде – в Узбекистан, где она, 12-летняя девочка, вместе с со своими родными перенесла и постоянный голод, и непосильный труд.

И сегодня, вглядываясь в фотографию, я сознаю, какой удар нанесла война моей большой семье. И в то же время история этой семьи – жестокое обвинение антисемитам, которые всегда говорили, что евреи во время войны отсиживались в Ташкенте. Да, мои тёти с малолетними детьми, чтобы не быть расстрелянными в немецкой оккупации, «отсиживались» в Узбекистане, но мой отец и все здоровые мужчины и даже некоторые из женщин моего клана никогда не прятались за чьи-то спины и честно сражались на фронте наравне со всеми.

Military Destinies of One Large Family

Semyon Belkin, Holocaust survivor from Russia

In front of me is an old photograph, one of those which are likely in every patriarchal family. This picture was taken in the late twenties of the last century, when I was yet to be born, in the house of my grandfather Moishe and grandmother Stysya, in the small, primarily Jewish, town of Rechitsa, not far from Gomel. In the center of the photo is the owner of the house, the famous ladies’ tailor Moishe Belkin. Next to him is his faithful wife Stysya, who bore him nine children, but there are only seven of them in the photo: five daughters and two sons. One of the sons died in infancy and one emigrated to America before the revolution. To the left and right of the parents in the photo are their four married daughters: Pesya, Freida, Taiba (aka Tanya) and Riva. Behind each daughter is her husband, and directly behind the grandparents are three bachelors: my future father Isaac, uncle Abram and aunt Lisa, who are at the time of this photo still unmarried.

In the foreground, the youngsters are on the floor in picturesque disorder. Now, I gaze sadly at the faces of these children. Here on the left sits a toddler in a velvet suit with a bowtie. This is Yasha, who went through the whole war as a simple soldier and reached Berlin. On the right are two lop-eared boys, hairstyles trimmed to zero. One of them, Dodik, who since his school years exhibited talent as a poet and was published in newspapers and magazines. At the age of 18 he volunteered for the front, wrote touching patriotic poems from the front line, and died shortly thereafter. His brother Khatskel was not taken into the army for a long time due to poor eyesight. Nevertheless, in 1943 he was sent to the front, where he was seriously wounded. A bullet went through his jaw and got stuck in his hand. According to the recollections of my cousin Tsina, when Khatskel returned home after all the hospitals, it was scary to look at him. An ugly scar ran through his entire lower jaw. There was not a single tooth in his mouth. His right hand hung like a whip. There was no bone from shoulder to elbow, and this thin stump was covered in scars. We learned many years later that Khatskel literally rose from the dead. He was lying in a mass grave, which they were about to bury when one of the soldiers heard a faint groan. Khatskel was dragged out of the pit and sent to the hospital. After many months of treatment, he returned to his mother, who, having lost one son, was desperate to see her second son alive. Subsequently, he became a Doctor of Physical Sciences, professor, and full member of the Academy of Sciences. He passed away at the age of 75, surrounded by honor and glory. The eldest of the children, Ida, sitting on the floor will disappear without a trace at the very beginning of the war. According to rumors, he was convicted, and his life ended in one of the Soviet camps.

In the evacuation to distant Uzbekistan, grandfather and grandmother died within an interval of two days. They were healthy, strong, and, if not for the war, they could still live and live. Of the four married couples of dad’s sisters shown in the photo, none of the pairs remained intact: during the war, one of each two died.

Death or serious injuries did not escape the grandchildren. I have already told about the death of 18-year-old Dodik. The fate of my beautiful aunt Freida and her 13-year-old daughter Hayushi was terrible (in the photo they are sitting in the second row: an aunt with a little daughter in her arms). On the eve of the war, they lived with her husband, an officer, in Bialystok on the border with Poland and woke up on June 22, 1941, already in the occupied territory. For more than a

year they were hidden from the Germans, and then someone betrayed them. Freud and Hayusia were taken to the ghetto, and then shot. Olya, Freida’s eldest daughter, already a student (in the picture she, then a teenager, sits on the floor in a sailor’s suit), walked a great distance through the forests, went from Bialystok to Rechitsa, to the house of her grandfather and grandmother, and from there volunteered in the army. My father, Lieutenant Colonel I.M. Belkin, received a severe concussion at the front, and suffered consequences of this concussion to the very end of his life. My uncle Abram had a long military path was in the army throughout the war, rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and reached Berlin with dignity.

A full cup of intense hunger, freezing temperatures, bombing raids, and other trials of the war years was consumed by my cousin Qing, whom we see in the photograph in the hands of my father in the third row. There was a multi-stage evacuation. First along the Dnieper by a steamer, then by train to Mozdok, then to Makhach-Kala, then by steamer to Baku, and another steamer across the Caspian to Krasnovodsk, and from there by train to Uzbekistan. She was a 12-year-old girl, together with her family, suffered both constant hunger and backbreaking work.

Today, looking at the photograph, I realize what a blow the war dealt to my large family. And at the same time, the story of this family is a cruel accusation against anti-Semites, who have always said that the Jews were hiding out in Tashkent during the war. Yes, my aunt with her young children, so as not to be shot in the German occupation, “sat out” in Uzbekistan, but my father and all healthy men, and even some of the women of my clan, never hid behind someone’s back. They fought honestly at the front on an equal footing with everyone.

В прошлом году мы с мужем впервые в жизни посетили Израиль, и одной из наших первых экскурсий была поездка в Иерусалим, где мы прежде всего посетили музей жертв Холокоста, знаменитый мемориал Яд Вашем. Потрясенные мы переходили из зала в зал, но в одном из них мы буквально застыли на месте. Там на стене я увидела фотографию, которая навсегда запечатлелась в моей памяти. На краю рва, в котором лежит груда мертвых человеческих тел, стоит на коленях молодой мужчина, окруженный группой немецких солдат и офицеров. Над ним наклонился один из вояк с пистолетом в руке. Сейчас прогремит выстрел, обреченный мужчина, с простреленной головой упадет в ров. Эту фотографию сделал офицер айнзатцгруппы и на обороте сделал надпись: «Последний еврей Винницы.

Моя родная Винница, город, где родились мои дедушка и бабушка, мои родители, где за несколько лет до начала войны родилась я. Это был тихий провинциальный город, в котором всегда проживало очень много евреев. Все они рожали много детей. Так, у моей мамы было две сестры и три брата. Когда началась война, мой отец, дядя Соломон и мужья маминых сестер сразу отправились на фронт, оставив своих жен с маленькими детьми в Виннице. События развивались очень быстро. Уже 19 июля 1941 г на двадцать восьмой день войны немецкие танки грохотали на улицах Винницы, а сотни женщин с детьми отчаянно штурмовали товарный эшелон - последний поезд, отходящий из города. В этой толпе была моя мама с тремя маленькими дочками, две ее сестры тоже с маленькими детьми, причем одна из них была на последнем месяце беременности; полуслепой брат Миша с женой и двумя детьми, младший брат – Абраша, которому только что исполнилось 16 лет и дедушка с бабушкой. Уже в глубокой старости моя мама на листочке бумаге старательно выписала имена всех членов ее большой семьи, которые на последнем поезде бежали из Винницы, и подсчитала: всего их было двадцать два человека.

С невероятными мытарствами, под бомбежками, поезд доставил беженцев в городок Георгиевск на Северном Кавказе, но через несколько месяцев сюда подошли германские войска. Когда немцы были уже совсем рядом, работники местного военкомата на грузовиках объезжали дом за домом и всюду, где обнаруживали мужчин, без разбору сажали их в кузов и отправляли на фронт. Не обошли они и дом, в котором жили мы. Никакие уговоры и объяснения, что Миша практически ничего не видит, не помогли. И тогда младший брат отправился вместе с ним, чтобы быть рядом. Так два брата попали на передовую. В первом же бою Миша погиб, а юный Абраша прошел всю войну, был тяжело ранен и вернулся домой, в Винницу.

Оставшихся членов маминой семьи снова погрузили в товарный поезд и повезли в Ташкент, где они жили под стеной вокзала и хоронили уходящих из жизни от голода и болезней: бабушку, дедушку, мою младшую сестру, и мы не знаем , где их похоронили. А по дороге в Ташкент у маминой сестры погиб только что родившийся ребенок. Через некоторое время нас поселили в кишлак под названием Гурч Мазар, где нас всех разместили в одной комнатке с земляным полом. Все члены нашей большой семьи, включая детей, собирали хлопок. Мы – взрослые и особенно дети - очень страдали от постоянного чувства голода, а еще больше

– от жажды. Самых маленьких иногда подкармливали местные жители – сердобольные узбеки. До сих пор я сохранила в своей душе чувство искренней благодарности этим простым людям, которые поддержали нас, малышей, в эти суровые годы. По стечению обстоятельств в последние годы жизни моей мамы за ней ухаживала женщина - узбечка, и она это делала с полной отдачей – так, как если бы это была ее родная мать. Может быть поэтому у меня особое отношение к узбекскому народу.

Сразу же после освобождения Винницы мы вернулись на родину. Только тогда мы узнали о судьбах родных и близких, оставшихся в Виннице, и прежде всего о семье моего отца. Дело в том, что его мама с четырьмя дочками и их детьми категорически отказались уезжать из города. Старики вспоминали Первую мировую войну, когда немцы оккупировали Украину, но мирные жители продолжали жить довольно спокойно, евреи вполне миролюбиво общались с немецкими солдатами на Идыш. Поэтому мать отца, равно как и многие другие евреи, не считали необходимым срываться с насиженных мест и отправляться куда-то в неизвестность. Но жизнь преподнесла им совсем иную реальность.

Буквально через несколько дней после того, как немцы вошли в Винницу, все евреи были загнаны в гетто, и вскоре начались расстрелы. Первая партия евреев -146 человек была расстреляна 28 июля, к 22 сентября было уничтожено 28 000 человек, а последние 150 евреев были расстреляны 25 августа 1942 г., включая того мужчину на фотографии, которую мы с мужем увидели в музее Яд Вашем.

Когда мы вернулись в Винницу, наша соседка показала маме место, где была расстреляна вся папина семья, и только через некоторое время объявилась Мила, племянница моего отца, которую расстреливали вместе с другими евреями, но ее мама прикрыла собой свою дочь, и получив свою пулю, она упала в яму, продолжая прикрывать маленькую Милу. После экзекуции немцы не торопились закапывать трупы и отправились пить водку, а Мила выползла из ямы, где ее подобрала женщина из соседнего села, крестила, чтобы спасти от новых экзекуций и оставила у себя до прихода в Винницу советских войск.

Вот так через жизнь моей большой семьи прошла беспощадная война, оставившая неизгладимый след в моей памяти, хотя я была еще совсем маленьким ребенком. И та фотография, которую я увидела в музее жертв Холокоста - это не просто один из жутких эпизодов Второй Мировой войны, а частица моего сердца, самая скорбная страница моей биографии, ощущение того что я прямая наследница того последнего еврея Виннице и что я обязана жить и рассказывать своим детям и внукам о страшном времени, именуемом Великой Отечественной войной.

Looking at the Photograph

Last year, my husband and I visited Israel for the first time in our lives. One of our first excursions was to Jerusalem, where we first visited the Museum of Holocaust Victims, the famous Yad Vashem memorial. Shocked, we moved from hall to hall, but in one of them we literally froze in place. There, on the wall, I saw a photograph that is forever imprinted in my memory. At the edge of the ditch, which contains a pile of dead human bodies, a young man is kneeling, surrounded by a group of German soldiers and officers. One of the soldiers is bent over him with a pistol in his hand. Any moment now there will be a shot, the doomed man will fall into the ditch with a bullet in his head. This photograph was taken by an officer of the Einsatzgruppen and on the back, he inscribed: “The last Jew of Vinnitsa.”

My native Vinnitsa, the city where my grandparents and parents were born, and where I was born a few years before the war. It was a quiet provincial town where there were always many Jews, who had many children. My mother had two sisters and three brothers. When the war began, my father, Uncle Solomon, and the husbands of my mother’s sisters immediately went to the front, leaving their wives with small children behind in Vinnitsa. Events moved very quickly. Already on July 19, 1941, on the 28th day of the war, German tanks rumbled on the streets of Vinnitsa. Hundreds of women with children desperately stormed the freight train: the last train leaving the city. In this crowd were my mother with three small daughters. Her two sisters also with small children, and one in her last month of pregnancy. Her half-blind brother Misha with his wife and two children. Her younger brother Abrasha, who had just turned 16, and her grandfather and grandmother. In her later years, my mother wrote down the names of all the members of her large family who fled from Vinnitsa on the last train, carefully documenting all twenty-two of them.

Experiencing incredible ordeals, under bombing raids, the train delivered the refugees to the town of Georgievsk in the north Caucasus. Only a few months later German troops reached there. When the Germans were getting close, the workers at the local military enlistment office drove trucks from house to house and wherever they found men, indiscriminately put them in the back and sent them to the front. Our house was no exception and no persuasion or explanation that Misha could hardly see did any good. His younger brother went with him to be near him. The two brothers were sent to the front line. In the very first battle, Misha was killed, while young Abrasha went through the whole war, was seriously wounded, and eventually returned home to Vinnitsa.

The remaining members of my mother’s family were again loaded onto a freight train and taken to Tashkent, where they lived under the wall of the train station. They buried those who died from hunger and disease: grandmother, grandfather, my younger sister; we do not know where they were buried. On the way to Tashkent, the newly born child of my mother’s sister died.

After a while we were settled in a village called Gurch Mazar, where we were all placed in the same room that had an earthen floor. All members of our large family, including children, picked cotton. All of us, adults and especially children, suffered greatly from the constant pains of hunger and, even more, from thirst. The smallest were sometimes fed by residents, compassionate Uzbeks. Until now, I have kept in my soul a feeling of sincere gratitude to these regular people who

supported us in these harsh years. By coincidence, in the last years of my mother’s life, an Uzbek woman looked after her, and she did it with full dedication, as if it were her own mother. Maybe that is why I have a special kinship towards the Uzbek people.

Immediately after the liberation of Vinnitsa, we returned to our homeland. Only then did we learn about the fate of relatives and friends who had remained in Vinnitsa, and, above all, about my father’s family. The fact is that his mother with four daughters and their children categorically refused to leave the city. Many older people recalled the First World War, when the Germans occupied Ukraine, when civilians continued to live quite calmly, and the Jews quite peacefully communicated with the German soldiers in Yiddish. Therefore, my father’s mother, as well as many other Jews, did not consider it necessary to break away from their homes and flee to the unknown. But events presented them with a completely different reality.

When we returned to Vinnitsa, our neighbor showed my mother where all my father’s family had been shot. All but Mila, my father’s niece. She was to be shot along with the other Jews, but her mother used her body to shield her, falling into the pit while continuing to cover little Mila. After the execution, the Germans were in no hurry to bury the corpses and went to drink vodka. Mila crawled out of the pit and a woman from a neighboring village picked her up, baptized her in order to save her from new executions, and looked after her until the Soviet troops arrived in Vinnitsa.

A few days after the Germans entered Vinnitsa, all Jews were driven into the ghetto and the executions soon began. The first batch of 146 Jews were shot on the July 28, 28,000 were killed by September 22, and the last 150 Jews were shot on August, 25, 1942, including the man in the photograph my husband and I saw at Yad Vashem.

This is how a merciless war went through the life of my large family, leaving an indelible mark on my memory, although I was still a very young child. The photo that I saw in the Museum of Holocaust Victims does not just illustrate a terrible episode of the Second World War, but is a part of my heart, the most sorrowful page of my biography: the feeling that I am the direct heir of that last Jew in Vinnitsa and that I must live to tell your children and grandchildren about the terrible period called the Great Patriotic War.

Мое имя Эмилия родская. Роднласья в городе Ленинграде, в 1931 г., 12 июля, в госпитале на улице Маяковского. Я была единственным ребенком у моих замечательных родителей. Мама- Софья Григорьевна, была домохозяй- кой, растила дочку. Папа - Бродский Наум Борисович, был инженер-кораблестроитель, работал в проектном институте по проектированию кораблей.

Из родственников две мамины сестры с семьями также жили в городе Ленинграда. Тетя с двумя детьми была эвакуирована из осажденного города на Урал, другая мамина сестра была врач, ушла добровольцем на фронт.

Жили мы в Ленинграде на улице Чехова, дом 11/13, в квартире То 7, на пятом этаже. это была обычная коммунальная квартира, пять семей жили под одной крышей, с одной кухней, с одним туалетом, без душу, без ванны. Конечно же, люди с разными характерами, и, наверное, не всегда было все в гармонии. Но я этого не помню.

Мои детские воспоминания о нашей квартире, о соседях самые теплые. Я любила семью Карасевых, любила моих подруг - Зою и Нину, любила их родителей - тетю Катю и дядю Карасева (так я их называла). Они были добрые люди. Эти хорошие взаимоотношения просуществовали всю нашу совместную жизнь. Мы расстались, когда мне было 46 лет. Я родилась в этой квартире и росла у всех на глазах. Это сближало. Мы с Зоей обожали нашу соседку тетю Аню и дядю Сашу, ее мужа. Они были актерами. У них не было своих детей, они любили проводить время с нами. Она водила нас в театр, в ТЮЗ, насколько я помню, так зародилась моя любовь к театру. До сих пор я ей благодарна. И вот началась война.

Пришел 1941 г. Как обычно, на три летних месяца мы уезжали в деревню на отдых. Это место было в трех часах езды поездом, и с начала июня мы с мамой были уже на даче в деревне. Папа приехал на следующий день после объявления войны и забрал нас домой, обратно в Ленинград. Через несколько дней он ушел добровольцем на Ленинградский фронт. Началась война. Все было нарушено, сломано, начались суровые военные будни.

С каждым днем ситуация в городе ухудшалась, постепенно исчезали продукты из гастрономов, ввели карточки, продукты стали выдавать по карточкам. Конечно же, никто не ожидал, что город окружен немцами. Маму отправили копать окопы, меня же определили в интернат для детей фронтовиков, где я проводила целый день, меня там кормили. Участились обстрелы.

Когда мама вернулась с окопов я пошла в обычную школу, которая находилась в соседнем доме. Мы приходили в школу, радовались общению друг с другом, шутили, дружили. Удили математику, литературу, географию- все, что положено. Несмотря на трагическую реальность окружающей нас жизни, мы оставались детьми. Незабываемый эпизод: мальчик, который сидел со мной за одной партой, однажды принес мне луковицу. Это было огромной поддержкой для организма. Как же он это знал? Ему было 10-11 лет, а сердце уже гигантское.

Leningrad Apartment

Emilia Brodskaya, Holocaust survivor from Russia

My name is Emilia Brodskaya. I was born on July 12, 1931, in the Mayakovsky Hospital in Leningrad. I was the only child of my remarkable parents. My mother, Sophia Grigoryevna, was a homemaker who raised me. My father, Boris Naumovich Brodsky, was a ship-building engineer who worked in a ship design institute.

During the war, two of mother’s sisters were evacuated with their families from the besieged city to the Ural region. Another of her sisters was a doctor who volunteered to the frontline.

We lived in Leningrad at 11/13 Chekhova Street, Apartment 7, on the 5th floor. It was a regular communal apartment, where five families lived under one roof with one kitchen, one toilet, no shower, and no bathtub. Of course, all the families had different personalities and we were probably not always living in harmony. But I do not remember that.

My childhood memories about our apartment and neighbors are very warm. I loved the Karasevs family: my playmates Zoya and Nina and their parents, Aunt Katya and Uncle Karasev, as I called them. They were kind people. This good relationship lasted all our shared life. We parted when I was 46 years old. I was born and grew up in front of them. It made us close. Zoya and I adored our neighbors, Aunt Anya and her husband Uncle Sasha. They were actors. They did not have children, so they liked to spend time with us. She took us to a theater, TUZ, as far as I remember, and that is how my love for theater was born. I am thankful to her to this day.

Then the war started. The year 1941 arrived. As usual, we went to the countryside for the three summer months. The place was a three-hour train ride away, and my mother and I had been there since early June. On the next day after the declaration of war, my father came and took us back to Leningrad. In a few days, he volunteered to the frontline. The war began, and everything was disrupted and broken by the severe war routine.

With every day, the situation in the city worsened. Groceries gradually disappeared from the stores and food was rationed. Of course, nobody expected the Germans to approach Leningrad that fast. Soon, it was announced that the city was surrounded. My mother was sent to dig trenches, and I was assigned to the boarding school for children of frontline soldiers, where I stayed, and was fed. Bombings became more frequent and artillery barrages became more furious.

When my mother came back, I went to a regular school in a nearby building. At school, we enjoyed our comradery and had fun. We learned math, literature, geography: everything we were supposed to. Despite the tragedy surrounding us, we remained children. I will never forget how a boy sitting next to me brought me an onion. This was a huge support for my health. How did he know? He was ten years old, but his heart was gigantic.

Children Sent West

Leonid Bruk, Holocaust survivor from Russia

This is dedicated to my mother E Merrin, my father M Bruk, and my uncle L Shtukin.

In the beginning of July 1941, the government of Leningrad executed an absurd action to evacuate children aged 4 to 13. The children were taken away from their parents, sometimes forcibly, and sent to different regions of the country, including to the West, towards the attacking German army!

I was 6 at that time, and together with my cousin, Ella (10), and brother Dima (13), we were among the children to be sent to the Novgorod region. My mother, a teacher, volunteered to accompany this group that was sent west.

By that time, parents realized that their children were being sent towards the attacking Germans and were frantically tried to find them, to save them. Some buses were sent to bring them back to Leningrad. My uncle, Lev Semenovich Shtukin, came in a bus from a Kirov factory, where my father worked. He, together with my mother, loaded the children on the bus, as the cannonade of German artillery was getting closer. The three of us and another 15-20 children were saved even as a train in Lychkovo station was bombed, and thousands of Leningrad children perished.

This sad chapter in the Leningrad saga has not been talked about by Soviet historians.

В 1941 г. мне было 5 лет. Я хорошо помню Москву, погружённую во тьму светомаскировок, воздушные тревоги (по несколько раз за сутки), истошный вой сирены среди ночи и поспешные поиски бомбоубежищ. Первое время мы бежали к ближайшей станции метро, спускались и лежали на рельсах в ожидании отбоя. С маленькими детьми располагались в стоявших на путях вагонах.

С самого начала войны мой отец и старший брат были призваны в армию. Мама со мной по распоряжению властей вынуждена была эвакуироваться. Вместе с нами в эвакуацию отправилась сестра мамы с тремя детьми. Её муж, уйдя в ополчение, погиб под Москвой (вернее, “пропал без вести” ) в первые дни войны.

Мы ехали на Восток в товарных вагонах, забитых до отказа женщинами с детьми. Поезд двигался страшно медленно, с частыми остановками. На остановках люди пытались раздобыть воду, а лучше – кипяток, но боялись отстать от поезда.

Когда нас высадили в Башкирии на станции Чишмы под Уфой, в местной школе приехавших распределили по разным населённым пунктам, кажется, в основном, по деревням. Мама больше всего хотела попасть в русскую деревню, т.к. в башкирской или татарской были бы

проблемы с языком. В этом нам повезло. И ещё в том, что попали не в город, а в деревню. В деревне во многих избах жили одни женщины, мужчины были либо на фронте, либо в тюрьме.

Мы попали к Пелагее. Взрослые сажали на огороде картошку и турнепс. Благодаря этому мы не голодали. Многие из эвакуированных женщин работали на полях, зарабатывали “трудодни” и в уплату получали ржаную муку. Пшеничной муки, как и каких-либо фруктов, не было. Я не знала, что такое – яблоко, а пирог со свёклой, испечённый мамой в день рождения, считала деликатесом. А ещё у Пелагеи была коза, и когда появлялись козлятки, они жили вместе с нами в избе. Немногие привезённые из Москвы вещи (одежду брата, например) мама выменивала у местных крестьян на продукты, на горсточку “белой” муки. Деньги не имели тогда хождения, были не нужны.

Самым заметным человеком в деревне была тётя - почтальон. Мы ждали писем с фронта. Я писала родным письма печатными буквами. Зимой 1943-го года папу демобилизовали по состоянию здоровья. Он вернулся в Москву, ему предстояла серьёзная операция. Но благодаря этому он смог добиться для мамы разрешения на возвращение в Москву и выслал вызов. Однако, прежде, чем отправиться в обратный путь, маме пришлось ехать в Уфу, чтобы в вызов и пропуск вписали меня. Это было сопряжено с большими трудностями (добиться подводы с лошадьми и человека – “водителя кобылы”).

А ещё труднее было сесть в поезд на Москву. Для этого нам пришлось жить две недели на вокзале (т.е. на скамейке) в Чишмах со всеми узлами и чемоданами. Поезда, едущие в Москву, не останавливались на этой мелкой станции, т.к. были полностью нагружены вылеченными в тыловых госпиталях ранеными бойцами, возвращающимися на фронт. Свободных мест там не было. Наконец, с помощью каких-то мужчин в обмен на полушубок брата, мы были втиснуты в тамбур поезда, на минуту открывшего двери. На следующем полустанке нас высадили.

Как мы в результате уехали, не помню. Зато помню папу, встретившего нас в нетопленной комнате. Мы вернулись из эвакуации в начале марта, была ещё зима. Дом напротив нашего разбомбило, и в окнах не осталось стёкол. Папе пришлось отгородить уголок возле самой двери подальше от окон и поставить “буржуйку.” железную печурку, которую надо было топить дровами – остатками уцелевшей мебели. Зато мы оказались дома!

Осенью того же, 1943-го года я пошла в первый класс. Тетради приобрести было невозможно. Папа брошюровал тетради из каких-то листочков, чистых с одной стороны. Он линовал эти листочки в косую линейку и в клеточку – для письма и арифметики.

Наша соседка по коммунальной квартире работала на швейной фабрике, где шили военную форму. Тоненькие обрезки защитного цвета работникам разрешалось использовать для своих нужд. Помню, мама сшила мне юбочку из множества узеньких клинышков. Получилось очень даже кокетливо... Учительницы в школе любовались и хвалили мамину находчивость. Ни о какой школьной форме не могло быть и речи. На стене висела большая карта Европейской части СССР, и папа каждый вечер, по мере того, как наши войска продвигались всё дальше на Запад, с помощью булавок передвигал на ней красную ленточку – границу нашей территории, освобождённой от немецких захватчиков. Никогда

не забуду День Победы, точнее, ночь, когда я проснулась от того, что кто-то из домашних (кажется, невеста моего брата) целовал меня, со слезами повторяя: «Война закончилась!

Childhood memories

Ludmila Dakhia, Holocaust survivor form Russia

In 1941 I was 5 years old. I remember Moscow well, plunged into the darkness of blackouts, air raids (several times a day), heartrending howls of sirens in the night, and the hurried search for bomb shelters. At first, we ran to the closest metro station, and laid on the rails in the anticipation of the all-clear. Those with small children went into the train cars still on the track.

My father and older brother were called up at the very beginning of the war. My mother had to evacuate with me by order of the authorities. My mother’s sister and her three children were evacuated with us. Her husband, who went into the Home Guard, was killed near Moscow (or really, went “missing in action”) in the early days of the war.

We went east in freight trains, packed with women and children. The train moved terribly slowly, with frequent stops. At the stops people tried to find any water, or better yet, boiled water, but they were afraid to go far from the train.

When they let us off in Bashkortostan at the station Chishmy near Ufa, they divided us up in a local school by resettlement area, mainly by village. My mother preferred to go to an ethnically Russian village, since in a Tatar or Bashkir village there would be a language barrier. We got lucky about that. And even more lucky, we ended up not in a city, but a village. In the village, many huts were only women, the men were all at the front, or in jail.

We ended up in Pelagea. The adults planted potatoes and turnips in the garden. Thanks to that, we did not starve. Many of the evacuated women worked in the fields and earned “days of labor” and in payment received rye flour. There was no wheat flour, or any fruit. I didn’t know what an apple was and considered the beet turnover that my mother made on my birthday to be a delicacy. There were goats in Pelagea too. When the goat kids were born, they lived with us in the hut. My mother traded some of the things we had brought from Moscow, such as my brother’s clothes, with the local peasants for groceries, for a handful of “white” flour. There was no money in circulation; it was not needed.

The most famous person in the village was the postwoman. We awaited letters from the front, and I wrote notes to relatives in print letters. In the winter of 1943, my father was demobilized for health reasons. He returned to Moscow facing a serious operation. But thanks to that, he was able to get my mother permission and a travel permit to return to Moscow. However, before heading out on the return journey, my mother had to travel to Ufa to have a travel permit issued to me as well. This was fraught with great difficulties, getting a cart and horse and driver.

Even harder was getting onto a train to Moscow. To do so, we had to live in the station for two weeks (on a bench) in Chishmy with all our bundles and bags. Trains going to Moscow did not stop

at this tiny station because they were jammed with soldiers who had been treated at hospitals in the interior and were returning to the front. There was no space. Finally, we gave some men my brother’s fur coat to let us into the vestibule of the train as the doors opened briefly…and at the next step they had us get off….

How we left in the end, I do not remember. But I remember my father meeting us in the unheated room. We returned in March, when it was still winter. The building opposite had been bombed and there was no glass left in our windows. My father had to fence off a corner as far from the window as possible and brought over a pot-bellied stove heated with wood, mainly the remains of our furniture. But we were home!

That fall of 1943 I entered first grade. It was impossible to get notebooks. My father made notebooks out of discarded pieces of paper that were blank on one side. He lined the paper horizontally and vertically for writing and arithmetic. Our neighbor in our communal apartment worked in a garment factory where they sewed military uniforms. The workers were allowed to use narrow bits of khaki remnants for themselves. I remember my mother sewed me a little skirt from a bunch of these narrow wedges. It turned out a little flirty in the end. The teachers at school loved and praised my mother’s resourcefulness, and there was not a word spoken about a school uniform.

A big map of the European part of the USSR hung on the wall, and each evening my father used pins and red ribbon to show how our soldiers moved farther and farther west, and where our territory had been freed from German invaders. I will never forget Victory Day, or really, the night, when I woke up because someone at home (my brother’s wife, it turned out) kissed me, and with tears in her eyes repeated “the war is over!”

Моя статья польёт свет нашему поколению о жизни евреев в 20 веке на территории СССР.

Родился в 1925 году в семье ремесленника в городе Златополь, Украина. Название городу дала царица Екатерина Вторая. Объезжая Российские владения в 1787 году, увидела кругом золотые пшеничные поля и дала названия этим землям “Золотые поля”. Раньше эта территория называлась “Гуляй Поль”. Жили там в основном евреи 4050 человек и украинцев 1997 человек. В бытность СССР город переименовали в Новомиргород, Кировской области и начали обустраивать промышленными и культурными учреждениями город стал районным центром в 1959 году.

Мое рождение вызвало сенсацию у евреев города и осуждение моих пожилых родителей. Маме Тубе было 54 года, папе Моисею 61 год. Брату Иосифу 16 лет, сестре Розе 13 лет. Но мои родители сами не знали какой подарок они мне подарили на всю мою жизнь. В 20ом веке по гороскопу 1925 и 1975 года были годом Древесного Быка. Человек родившийся в год древесного быка присуще: терпение, сдержанность, он молчалив и медлителен,

под его спокойной внешностью скрывается мудрость, он упрям и не терпит, когда ему перечат. Такие качества сопровождают меня всю мою сознательную жизнь. В 1929 году умер папа Моисей, мне было года. В семье остался старшим брат Иосиф. В 1930 году он решил семью перевести в Москву в связи с наступившим голодом на Украине. Дом и все хозяйство, заработанное папой, бесплатно отдали бедным евреям. В Москву приехали на Казанский вокзал и жили на вокзале две недели. Мой брат Иосиф нашел комнату в бараке и продуктовые карточки на всю семью. Русского языка я не знал, но слышал от ребят, что я еврей. В 1933 году мне исполнилось 8 лет, но в школу меня не приняли по причине незнания русского языка. В нашем бараке жила еврейская семья, две дочери уже учились в старших классах. Они начали меня учить русскому языку в течение всего 1934 года. Язык я выучил и в 9 лет пошел в первый класс. К учебе в первом классе мама купила мне всю новую одежду даже новые калоши. На первой перемене меня окружили старшие школьники и предложили мне отдать мои новые калоши мальчику в рваных ботинках, из которых выглядывали голые пальцы ног. Я оказал сопротивление, меня повалили на пол, сняли мои новые калоши. Дома я боялся сам рассказать о моем ограблении, но мама сразу заметила и мне пришлось рассказать все как было. Мама мне сказала, чтобы я об этом никому не рассказывал. Я хранил мамину заповедь о моих новых калошах 86 лет, но, для вас решил огласить эту тайну. Школа была начальная, в пятый класс перешел в другую, новую школу и сразу попал в отстающие ученики. Для поднятия моего уровня знаний в учебе мне прикрепили из старшего класса отличницу по имени Бертина. Она проявила много усилий, в седьмом классе в 1941 году я сдал экзамены с хорошими оценками. Начались летние каникулы. Я готовился начать свою трудовую деятельность на авиационном заводе. Но, началась война и все пошло по другим канонам. Эвакуацию всей семьи из Москвы в годы войны я описал, будучи уже в Америке, в книге к 70ти летию нашей победы. “Война – наши судьбы”. На фронте в боях я был тяжело ранен. Всю войну я получал от Бертины теплые письма с надеждой на победу. В 1947 году был демобилизован, вернулся в Москву. Мама умерла, не дождавшись моего возвращения. У брата Иосифа образовалась семья и двое детей. Сестра Рода из эвакуации не вернулась, осталась в Казахстане, обзавелась хозяйством и растила своих троих дочерей. Бертина вернулась из эвакуации в Москву, жила одна и уже работала. Наши отношения стали близкими, и мы решили стать мужем и женой. В этом же году узаконили наш брак. Через год у нас родился сын Игорь. Я начал трудовую деятельность в строительных организациях. Московским строителям после десяти лет работы гарантировали квартиры на всю семью. Все десять лет мы жили с родителями Бертины в одной квартире, у нас была отдельная комната. 12 лет из работающих строителей готовили кадры на руководящие должности. Это был вечерний институт с двухгодичной

программой. Закончив институт, получил диплом строителя по специальности инженер. Работал на руководящей работе в системе Главмосстроя. Приближался десятилетний срок получения квартиры (1958 год). Решили пополнить свою семью еще одним ребенком, родилась дочь, назвали Татьяной, в память о моей маме. Сейчас Татьяна живет в США. В Москве закончила институт иностранных языков, здесь преподает в школе русский и английский. Подарила мне внука Марка, который в свои двадцать лет закончил институт и стал биологом.

В 2004 году умерла жена Бертина. Ей исполнилось 80 лет. В 2005 году в госпитале имени Бурденко комиссия врачей хирургов определила о необходимости операции мне на позвоночнике. В операции мне отказали из-за возраста, мне исполнилось 80 лет, Таня настояла о моем переезде в Америку, где меня полностью обследовали, назначили операцию и не спросили, сколько мне лет. Операция была в 2006 году в медицинском институте в Вашингтоне. После операции меня направили в реабилитационный центр, где меня полностью восстановили для нормальной жизни. Жил я в семье моей дочери Татьяны до 2008 года. Обрел много друзей выходцев из России, каждую неделю собирались вместе, делились своими новостями, оказывали потом моральную и материальную помощь нуждающимся. В 2008 году я переехал в дом для пожилых людей, получил двухкомнатную квартиру, в которой живу уже 12 лет. В 2011 году получил гражданство США. Получаю пособие, обеспечивающее достойную жизнь. С возрастом здоровье сдает. Отпраздновал свое 95летие, приходится пользоваться ролейтором.

Азик Голдовский, ветеран второй мировой войны. 07/23/2020

The Secret Galoshes

Azik Goldovskiy, Holocaust survivor from Ukraine

My article will shine a light on my generation: the lives of Jews in the 20th century in the USSR.

I was born in 1925 to a family of artisans in the city of Zlatopil, Ukraine. The name of the city was given by Catherine the Great. When she went around the Russian lands in 1787, she saw the golden wheat fields and named the area “Golden Fields.” Previously, it had been called Hulajpol. The population was mainly Jewish (4,050 people) and Ukrainians (1,997 people). During the time of the Soviet Union, the city was renamed Novomyrhorod Kirov Region, where industrial and cultural institutions developed, resulting in the city becoming a district center by 1959.

My birth caused a sensation among the Jews of the city and condemnation of my elderly parents. My mother Tuba was 54 and my father Moses was 61. My brother Joseph was 16 years old when I was born, and my sister Rose was 13 years old. But my parents did not know what a gift they gave me for the rest of my life. In the 20th century, the horoscope for the years 1925 and 1975 was the Tree Bull. A man born in the year of a Tree Bull is characterized by patience, restraint, he is silent and slow, under his calm appearance hides wisdom, he is stubborn and does not tolerate when he is interrupted. Such qualities have accompanied me my entire adult life.

In 1929, my father Moses died. I was four. My elder brother Joseph became the man of the family. In 1930 because of the famine in Ukraine, he decided to move our family to Moscow. The house and the farm established by my father were given free of charge to poor Jews. In Moscow we arrived at the Kazansky Station, where we lived for two weeks. Joseph found a room in the barracks and food cards for the family. I did not know Russian, but I was able to pick up from others that they referred to me as Jewish.

In 1933, I was 8 years old, but I was not accepted to school because of my ignorance of the Russian language. In our barracks, there was a Jewish family with two daughters who were already in high school. They taught me Russian throughout 1934. I learned the language and at 9 years old I went to first grade.

When I started first grade, my mother bought me all new clothes, including galoshes. At the first recess, I was surrounded by older students who asked me to give my new galoshes to a boy in torn shoes, whose bare toes peeked out. I resisted. I was knocked to the floor and my new galoshes were taken. At home I was afraid to tell about the theft, but my mother immediately noticed, and I had to tell everything. My mother told me not to tell anyone about it. I kept my mother’s commandment about my new galoshes for 86 years, but I decided to make this secret public here, to you.

In elementary school, in the fifth grade I moved to another school and was immediately put with the lagging students. To improve my studies, I was assigned to a senior classmate with excellent grades named Bertina. She put a lot of effort into helping me through the seventh grade in 1941 and I passed the exams with good marks.

During the summer holidays, I was preparing to start my career at the aviation plant, but then the war started, and everything went according to other canons. I described the evacuation of my family from Moscow during the war in a book, War Is Our Destiny, released to commemorate the 70th anniversary of our victory. On the front, I was seriously wounded in battle. Throughout the war I received warm letters from Bertina who wrote of the hope of victory. In 1947 we were demobilized and returned to Moscow.

My mother died before I came back. My brother Joseph had a family and two children. My sister Rhoda did not return from the evacuation, staying in Kazakhstan on a farm where she raised her three daughters. Bertina returned from the evacuation to Moscow, lived alone, and was already working. Our relationship became close and we decided to become husband and wife. In the same year, our marriage was legalized. A year later our son Igor was born. I started working for construction organizations. After ten years of work, Moscow builders were guaranteed apartments for the whole family. For those ten years, we lived with Bertina’s parents in the same apartment, where we had a separate room.

For 12 years, working builders were trained for senior positions. It was an evening institute with a biennial program. After graduating from that institute, I received a diploma of builder in the specialty of engineering. I worked in a leadership role in the system called Glavmostroy (Chief Builder). As the ten-year period to obtain an apartment was approaching (1958), we decided to add another child to the family, and our daughter was born. We named her Tatiana, in memory of my mother. Now, Tatiana lives in the United States. She graduated from the Institute of Foreign Languages in Moscow and teaches Russian and English. I have a grandson, Mark, who graduated from university at the age of twenty as a biologist.

My wife Bertina died in 2004. She was 80 years old. In 2005, at the Burdenko Hospital, a commission of surgeons determined that I needed surgery on my spine. I was refused the surgery because of my advanced age and Tanya insisted that I move to America, where I was fully examined and had surgery, since they did not care how old I was. The operation was in 2006 at the Medical Institute in Washington. After the operation, I was sent to a rehabilitation center, where I was completely rehabilitated for a normal life.

I lived with my daughter Tatiana’s family until 2008. I made many Russian friends and we gathered weekly, shared news, and provided moral and material assistance to those in need. In 2008, I moved into a two-room flat at an apartment complex for the elderly, where I have been living for 12 years. I was granted U.S. citizenship in 2011. I receive benefits that support a decent life. With age, health gives up and I now rely on a walker to get around. I recently celebrated my 95th birthday.

The Delight of Fresh Air: A Story from My Life

Tamara Gribach Holocaust survivor from Russia

My three grandchildren are grown up. When they were six years old, memories of being six-anda-half myself surprised me very much, because I had always worried about them. I walked alongside them like any grandmother.

When I was at that age, the Great Patriotic War ended. During the war years I was very ill; I became particularly weak after a bout of malaria. The doctors advised getting me to a warmer climate immediately, and so my father took me by train to the city of Kherson, which has a dry, southern climate. We lived in Kuybyshev at the time. The train cars were stuffed with people, men were smoking, and it was very hot and humid. Quite often I would run to the inside open door of the train to breathe some fresh air, where I saw a ladder leading to the roof of the car. I bounded up the ladder to the top and with great delight breathed in fresh air. I spent a lot of time on the top of this car. Nobody knew about it, and I never told my father. The journey was long, and no one saw my trips to the top of the car.

Just as my grandchildren turned the age I was then, my memories came to life and I was horrified at how dangerous it was, as the train was very rickety.

In Kherson, my father was offered an engineering position and an apartment with seven other people, and left me with my cousin’s family and went back to Kuibyshev to finish up business at the aviation factory where he worked (which launched the famous airplane Li-2), and prepare for the family’s move.

Two years ago, Efim’s brother invited me to Israel. He had already organized an itinerary of tourist sites beforehand and I saw many things. I very much enjoyed Israel, especially the people there. They were very pleasant and caring towards tourists; they always tried to help. My cousin told me, “Next time, when you come…” I laughed, I am almost 80, I know that there will not be a next time, but I am happy that I saw this wonderful country. I am very thankful to my cousin.

Another Memory: When my son-in-law found out that I remember Victory Day in the former Soviet Union, he asked me to write about it.

I was about six and a half years old, and my parents worked at an aircraft manufacturing plant in Kuybyshev, where the famous Li-2 was launched. All of a sudden, my parents came back home on the bus from the factory at an unusual time. Everyone was shouting gleefully, “Victory, victory!” Happiness filled the entire area. I am reading a book on the history of this factory; it is very interesting by P Kozlov.

Я был инженером-конструктором в Харькове и жил там с моей прекрасной женой, изображенной здесь, Зиной. Ниже приведена история моей любимой жены, которая скончалась после многочисленных болезней 6 июня 2014 года.

Я Кресина ( Мачульская) Зинаида Абрамовна родилась в 1936 году в городе Харькове Украинской СССР. Там же, в городе в Харькове в 1939 году родилась моя сестра Фельдман ( Мачульская ) Татьяна Абрамовна. Со дня рождения и до эвакуации мы с родителями, отцом – Мачульским Абрамом Яковлевичем, матерью – Рабинович Розалией Зиновьевной проживали в городе Харькове. Эвакуировались мы семьей: я, сестра и наши родители. Папа по состоянию здоровья был признан не годным к строевой. Эвакуироваться было очень тяжело так как все составы в сторону Урала и средней Азии уже в Харьков приходили переполненными и мало кому удавалось как-то втиснуться. Люди оставались на вокзале в ожидании следующих составов. Так было и с нами. Мы несколько суток были на вокзале. И только 17 октября 1941 года нам удалось уехать. Это был последний эшелон, который отошел от Харьковского вокзала. А немцы уже были на окраине Харькова. Поэтому вспоминать посадку на этот эшелон страшно. Все наше имущество – мешок с сухарями. Вагоны были переполнены. Детей передавали в окна. Нас с сестрой родители тоже передали в окна и с трудом заняли места. На подножке вагона в мою детскую память врезались отчаянные крики людей, оставшихся на перроне и потерявших последнюю надежду на спасение. Одновременно с нами должна была выехать семья папиного родного брата. Но, они выехать не смогли и были расстреляны на Харьковском тракторном заводе – место массового истребления евреев (наподобие Бабьего Яра в Киеве).

Состав обстреливался. Мы встречали разбомбленные встречные проезжавшие составы. На участке (примерно) Курск-Воронеж полыхало пламя. Мы видели превратившийся в груды металла встречные поезда. В моменты, когда пули свистели почти над головами в вагоне затихали голоса, даже переставали плакать дети, наступало гробовое молчание. В мыслях было одно: хоть бы пронесло! Трудно передать то нервное напряжение, в котором мы находились в этой страшной дороге. Все это потрясло наши детские сердца, и мы не по возрасту взрослели.

Не доехав до Ташкента, мы с сестрой заболели корью и воспалением легких. В Ташкенте нас высадили и положили в больницу. Родители днем были у нас в больнице, а ночевали на вокзале. Результат перенесенной болезни – осложнение на уши, которое давало себя знать долгие годы. Из Ташкента путь наш продолжился до Намангана. По пути в дороге заболели сыпным тифом родители и нас снова высадили на каком-то полустанке и поселили в глухом колхозе, кажется, колхоз назывался “Шуро”. Местный узбек выделил нам во флигеле маленькую холодную комнату, в которой помещались только четыре железные кровати и стул. Эту комнату я отчетливо помню и по сей день. Помню, даже, что дверь комнаты не запиралась и папа на ночь привязывал своим поясом ручку двери к своей кровати. В этом колхозе мы пробыли какое-то время (точно не помню сколько) и уже уехали в Наманган. Это был последний этап страшной дороги, которая вела нас в неведение, но и которая спасла нас от немецкой гибели. Сколько мы были в пути я точно не помню, но с учетом вынужденных остановок мы прибыли в Наманган, кажется, в конце 1941 года или в начале 1942 года. В Намангане я заболела тяжелой азиатской болезнью, которая практически не давала шансов на выживание. Благодаря усилиям мамы, как врача меня удалось спасти. Но последствия этой болезни – ухудшение зрения, которое позже усложнилось в связи с сахарным диабетом – предмет моих страданий по сей день. Папу призвали в строительный отряд в городе Кишинев на Урале. Но там он пробыл не долго (несколько месяцев). В связи с тяжелой болезнью его демобилизовали и он снова вернулся к нам в Наманган. Таким образом мы, практически, все время эвакуации были всей семьей. Мама работала в городе Намангане – врач, что видно из записи в трудовой книжке. В эвакуации мы были более двух лет.

В апреле 1944 года мы вернулись в Харьков. Освобожден Харьков от немцев 23 августа 1943 года. Получили квартиру в полуразваленном доме, которую долго ремонтировали так как у нас не было мебели и вещей, родители пошли в квартиру по Поплавской 8, откуда мы эвакуировались. Все вещи были сохранены. Но жили там новые жильцы. На просьбу родителей вернуть хотя бы детские кроватки, жильцы антисемиты грубо ответили отказом. Пришлось начинать жить с нуля. Тяжелые годы войны, эвакуация, тяжелые послевоенные годы, дали о себя знать. Мама заболела тяжелой формой гипертонии и на 54ом году жизни умерла от инсульта. Папа умер позже от инфаркта. Умерли родители в Харькове.

Мы с сестрой жили в Харькове. В Харькове вышли замуж. Сестра с семьей жила в Харькове по апрель 1991 года. В 1991 году уехала в США. Я с мужем жила в Харькове по январь 1994 года. В январе 1994 года, как беженцы приехали в США. Мы воссоединились с сестрой. В настоящее время мы с мужем живем в США.

На оригинале письма написано другим почерком:

6 июня Зина Мачульская-Кресина после многочисленных болезней, к сожалению, ушла из жизни.

My Wife, Zina

Mark Kresin, Holocaust survivor from Russia

I was an Engineer Constructor in Kharkov and lived there with my beautiful wife Zina, photographed here. Below is the story of my beloved wife who passed away after numerous illnesses on June 6, 2014.

I, Zinaida Abramovna Kresina (Machulskaya), was born in 1936 in Kharkiv (Kharkov), Ukraine. My sister Tatiana Abramovna Feldman (Machulskaya) was born in Kharkiv in 1939. From the day of birth until the evacuation, my parents, my father Maculsky Abram Yakovlevich, and my mother Rabinovich Rosalia Zinovievna, lived in the city of Kharkiv. We were evacuated as a family: me, my sister, and our parents. My father was deemed unfit for service for health reasons. It was very difficult to evacuate as all trains in the direction of the Urals and Central Asia were arriving in Kharkiv overcrowded, so only a few people managed to squeeze aboard. Most people remained at the station waiting for the next trains, which happened to us too. We were at the station for several days. It was only on October 17, 1941, that we managed to leave. It was the last train that departed from Kharkiv station. The Germans were already on the outskirts of Kharkiv.

I have a frightful memory of boarding this train. The only luggage we boarded with was bags of dried bread. The train cars were overcrowded. The children were boarded by being passed through the windows. My sister and I were also passed through the windows and hardly found somewhere to sit. Upon boarding the train, my childhood memories are of the desperate cries of people left on the platform—losing their last hope of salvation. At this same time, my uncle’s family was also trying to leave, but they were unable. They were shot at the Kharkiv tractor factory: a place of mass extermination of Jews (like Babi Yar in Kiev).

The train was fired upon, and it passed bombed and damaged oncoming trains. On the Kursk-Voronezh section (approximately), fires were burning. We saw trains that had been turned into piles of burned metal. At the moments when the bullets almost whistled over the heads of those in the train car, all voices died down, even the children stopped crying, everyone was deathly silent. I had only one thought: please let the bullets miss us! It is difficult to convey the nervous tension we were under on this terrible journey. These events changed our childhood and forced us to grow up instantly.

Before reaching Tashkent, my sister and I fell ill with measles and pneumonia. In Tashkent we were dropped off and admitted to the hospital. Our parents stayed in the hospital with us during the day and spent the night at the train station. As a result of this illness, I had developed a complication in my ears, which bothered me for many years. From Tashkent our journey continued to Namangan. On the way, my parents fell ill with typhus and we were again dropped off at some station. We were settled in a remote collective farm, called “Shuro.” A local Uzbek gave us a small, cold room in a freestanding building, in which there were only four iron beds and a chair. I clearly remember the room to this day. I even remember that the door of the room was not locked and my father tied the handle of the door to his bed with his belt at night.

We stayed on this collective farm for some time and then left for Namangan. This was the last stage of the terrible road that led us into uncertainty, but which also saved us from German death. I do not know exactly how long we were on the road, but taking into account the forced stops, we arrived in Namangan near the end of 1941. I fell ill with a severe Asian disease, from which they considered I had a low chance of survival. Thanks to the efforts of my mother, acting as my doctor, I survived. But the consequences of this disease, deterioration of vision, which later became more complicated in connection with diabetes mellitus, is the subject of my suffering to this day.

My father was called to join a construction team in the city of Chisinau in the Urals. But he did not stay there for long, only for a few months. Due to a serious illness, he was demobilized and he returned to us in Namangan. Thus, we remained practically as a whole family during the evacuation. Mom worked in the city of Namangan, as a doctor, as can be seen from the entry in the work book. We were in exile for over two years.

In April 1944, we returned to Kharkiv. The city was liberated from the Germans on August 23, 1943. We rented an apartment in a dilapidated house, which had been abandoned for a long time, and that did not have furniture or other essentials. My parents went to the apartment at 8 Poplavskaya Street, from where we had been evacuated previously. All our old things remained, but new tenants lived there. At the request of my parents, who asked to at least return our childhood cribs, the new residents, who were anti-Semitic, rudely refused. We had to start over from scratch. The difficult years of the war, the evacuation, the difficult post-war years made themselves felt. Mom fell ill with a severe form of hypertension and died of a stroke in the 54th year of her life. Dad died a few years later of a heart attack. Both my parents died in Kharkiv.

My sister and I lived in Kharkiv and we both were married there. My sister and her family lived in Kharkov until April 1991, when she left for the United States. My husband and I lived in Kharkov until January 1994 when we came to the United States as refugees. We were reunited with my sister. My husband and I continue to live in the United States.

Evacuation to Uzbekistan

I was born in Kiev, Ukraine. Germans came and occupied Kiev, the capital of Ukraine. My grandmother, mother, and I rushed to escape the German invasion by evacuating to Uzbekistan.

Опубликованно в «Каскад», Мау 2011 №10(382). Cascade Russian Newspaper

Из Прошлого. Кануло каждое мгновение в вечность. Такое свойство у мгновения – скоротечность. Момент, он раз… и в прошлое ушел. И каждый в прошлом жизнь свою нашёл.

Память! Укаждого - своя. Почему мы запоминаем те эпизоды, а не другие? Кто знает. Память избирательна. Вероятно, стрессовые моменты больше задерживаются и запечатляются в мозговых извилинах. У меня в памяти прошлого всплывают эпизоды с 6-летнего возраста, когда русские войска вошли в Ригу, где я родился. Это относится к периоду 1940 года. По улице ходили демонстранты в полосатых одеждах, на эсплонаде, в центре города стояли русские танки, и солдаты поднимали на них детей. А через год война.

Идём по Мариинской улице к вокзалу. Мы от него недалеко. Разбитые и разграбленные витрины. Слышны хлопки выстрелов.

Мы в маленьком купе поезда. Людей битком. Сидят плечо к плечу, стоят. Поезд всё время дёргается, движется рывками. Мама куда-то исчезла. Оказалось, что она подслушала разговор по немецки (она понимала) и передала содержание нашей няне, которая ехала в вагоне с военными. Те пришли, начали обыскивать человека, обнаружили пистолет. Вывели, услышал хлопок....

Помню, остановился поезд. Я выглянул в окно. Стоит высокий мужчина спиной к окну, у него вся голова в крови, а на его руках ребёнок с откинутой головкой.

Кто–то бросился с винтовкой от поезда в лес, он был неподалеку. Бежал зигзагами, а по нему стреляли. Проскочил опушку и скрылся в лесу.

На одной из остановок всем мужчинам велели выйти и встать вдоль вагона. Отец с трудом двигался, ослаб от голода. Всех стали обыскивать. У папы был небольшой перламутровый ножичек. И его отняли.

Другая остановка. Заброшенные товарные вагоны на параллельной ветке. В одном из них были ящики с изюмом. Один ящик принесли в купе. Все набросились. Ели до тошноты. Но скоро пришли красноармейцы и унесли что осталось.

Снова медленно, через бомбёжки, рывками движемся и вот опять, но теперь уже длительная остановка. Теперь мы едем в теплушке (товарном вагоне). Мама ушла за кипятком. И вдруг наш поезд стал двигаться, а мамы нет! О ужас! Мы просто замерли. К счастью, поезд просто перевели только на другие пути, а их было очень много. И много стояло поездов. Как же мама нас найдёт? Боже ты мой, где мама! Ура! Нашла. Но волнений сколько было! Наконец приехали. Село Якшанга, Горьковской области. Поселили нас в хате без электричества.

Лучины, потрескивая освящали хату. Не было даже керосинок, не то, что электричества. Моя сестра и я, которая была ровно на два года старше, устроились на печи.

Сейчас, много лет спустя, я понимаю, что решение мамы уехать спасло нам жизнь. Спасая нам жизнь, она дала жизнь моим детям и их детям и будущим поколениям. Мой дядя с двумя детьми и женой остались и погибли.

Уже на склоне лет приехал в Ригу из Америки навестить сестру. Я шёл по мемориалу в Бикерниекском лесу (как-то созвучно с Биркенау, помните, часть Освенцима), где проходили массовые убийства евреев с 1941 по 1944 год. Хорошо сделанный мемориал. Острые отколотые гранитные глыбы из разных стран и городов, остриями в небо, символизируют оборванные жизни и образуют небольшой сад. Белый каменный шатер и надписи на камне на латышском, иврите и русском из книги Иова Ветхого Завета:

Земля! Не закрой крови моей и да не знает покоя мой вопль! ИОВ 16;18

Сделаю отступление. Недавно мы с женой были на выставке Холокоста. Там большие плакаты с фотографиями людей, переживших и выбравшихся из ада. Приведена краткая история их судьбы. Меня поразило, что почти в каждом заключении призыв к отказу от мести и ненависти. Простить за муки невинных людей, детей, это значит вычеркнуть часть прошлого, забыть о нём! Это значит не считаться с историей. Есть вещи и действия, которые можно простить. Но годы заточения, унижения, надругательств, голода и холода, издевательств, каторжного труда и наконец убийств родных, близких, знакомых и не знакомых, детей – это нельзя забыть и забывать. Как эти люди пришли к этому заключению для меня непостижимо. Возвращаюсь к надписи на камне. Земля! Не закрой крови моей и да не знает покоя мой вопль! Это призыв как раз к обратному.

Иду дальше по тропинке, где братские могилы, примерно 8 на 3м., направо и налево, только обрамлены бордюром, и мне казалось, что в одной из них лежат они, мои родные, убитые только потому, что были евреями. Хотелось остановиться, убрать ветки, сломанные сучья, погладить траву...

Известно, что местные жители тоже принимали участие в убийствах, конфискации имущества, выдачи прячущихся и прочих злодеяниях. Почему и они? Это для меня необъяснимо! Ведь убитые были совершенно невинные люди. Откуда такая ненависть? Откуда безразличие к человеческой жизни? И многие из них кто был причастен к злодеяниям не понесли за это никакого наказания.

Мои близкие убиты, а я живой. Горечь от их утраты не покидает меня.

Мне давно пришло в голову идея, что люди умирают дважды. Первый раз физически, а второй, когда исчезает память о них. Гении живут вечно, такова их судьба, другим везёт меньше. Какая хорошая традиция у евреев говорить Кадиш в каждую годовщину смерти. Уйдём мы и кто будет читать Кадиш?

Memory!

Zalman Polott, Holocaust survivor from Latvia

Published in Cascade, May 2011 No. 10 (382). Cascade Russian Newspaper Memory! Everyone has his own. Why do we remember some episodes and not others? Who knows? Memory is selective. Probably, stressful moments linger and are imprinted on the brain. I have memories pop up from when I was six, when Russian troops entered Riga, where I was born. This was in 1940. Demonstrators in striped robes were walking along the street, on the esplanade Russian tanks were on standby in the center of the city, and soldiers carried their children. A year later, the war. We go along Mariinsky street to the train station. We are not far from it. Broken and looted windows. Shots can be heard.

We are in a small train compartment. People are shocked. They sit shoulder to shoulder, or stand. The train is always twitching, jerking around. Mom’s gone somewhere. It turned out that she overheard the conversation in German, and passed on what she heard to our nanny, who was traveling in a car with the military. They came, started searching a man, found a gun. They retreated; I heard a pop.... I remember the train stopped. I looked out the window. There is a tall man with his back to the window. His whole face is bleeding, and in his hands, there is a child with the head thrown back. Someone rushed with a rifle from the train into the woods nearby us. He ran zigzags, and he was shot. He slipped through the edge and fled into the woods. At one of the stops all the men were told to get out and stand along the carriage. My father struggled to move, weakened from hunger. Everyone was searched. Dad had a small pearl knife. And he was taken away. Another stop. Abandoned freight cars on a parallel track. One of them had boxes of raisins. One box was brought in the compartment. Everyone pounced. They ate until they were nauseous. But soon the Red Army came and took away what was left. Again slowly, through bombings, we are moving jerkily again, but now there is a long stop. Now we moved into a freight car. Mom went to get boiling water. And suddenly our train started to move, and my mother was gone! Oh horror! We just froze. Fortunately, the train was simply transferred to another track, and there were a lot of them. How will Mama find us? Oh, my god, there’s Mama! Hooray! She found us. But there were so many worries! Finally, we arrived at Yakshanga Village in theGorky Region. They settled us in a hut without electricity or kerosene. My sister, who was exactly two years older, and I warmed ourselves by the stove. Now, many years later, I realize that my mother’s decision to leave saved our lives. By saving our lives, she gave life to my children and their children and future generations. My uncle and his two children and wife stayed and perished.

Already in my declining years I traveled to Latvia from America to visit my sister. I walked through the memorial in the Bikernieki forest where the mass killings of Jews took place from 1941 to 1944. There is a well-made memorial. Sharp chipped granite blocks from different countries and cities, spike to the sky, symbolizing ragged lives and forming a small garden. There is a white stone tent and inscriptions on the stone in Latvian, Hebrew, and Russian from the Book of Job in the Old Testament:

Earth! Do not cover my blood and let my cry need no rest! IOV 16:18

I am retreating. Recently my wife and I were at a Holocaust exhibition. There were large placards with pictures of people who survived and got out of the hell. A brief history of their fate was given. It struck me that in almost every instance there was a call to renounce vengeance and hatred. To forgive for the torments of innocent people, children, it means to erase part of the past, to forget about it! It means not to reckon with history. There are things and actions that can be forgiven. But years of imprisonment, humiliation, abuse, hunger and cold, bullying, hard labor and finally murders of relatives, close friends, acquaintances and non-acquaintances, children—it is impossible to forget. How these people came to this conclusion is incomprehensible to me. I am returning to the inscription on the stone. Earth! This is a call to the contrary.

I go further along the path to the mass graves. In one of them lie, my relatives, killed simply because they were Jews. I wanted to stay, to clear the broken branches, to stroke the grass...

It is known that local residents also took part in the murders, confiscation of property, extradition of those in hiding, and other atrocities. Why them? It is inexplicable to me! After all, those killed were completely innocent people. Where does that hatred come from? Where does indifference to human life come from? And many of them who were involved in the atrocities were not punished for it.

My loved ones are dead, and I am alive. The bitterness of their loss does not leave me. It was a long time ago that the idea of people dying twice came into my head. The first time physically, and the second, when the memory of them disappears. Geniuses live forever, such is their fate, others are less lucky. What a good tradition Jews have of saying Kaddish on every anniversary of the death. We are going to leave and who is going to say Kaddish?

Мои родители поженились в ноябре 1934 года, а осенью 1938 г. родилась я. Мы жили вместе родителями моей мамы на 7 Советской улице. Это центр Ленинграда, недалеко от Московского вокзала. Перед самой войной родители построили большой дом в прекрасном месте, в знаменитом своими фонтанами Петергофе. Там, в этом доме в солнечный воскресный день 22 июня 1941 г мы и услышали объявление о начале войны.

В июле меня, вместе с детским садом эвакуировали из Ленинграда. Предполагалось, что таким образом детей спасают от фашистов, но в реальности их отправили прямо под немецкие бомбежки и танки. Каким-то чудом отец меня разыскал и привез назад в Ленинград. Но в ноябре, после начала блокады, когда немцы приблизились к самому городу, стало ясно, что надо бежать. Маме со своими родителями и со мной - трехлетней дочерью, удалось попасть на поезд, который следовал в Среднюю Азию, в Таджикистан. Мы добирались туда целый месяц. Поезд подолгу стоял на полустанках, пропуская составы с солдатами и техникой, следовавшими на Запад, на фронт и санитарные поезда с раненными - на Восток. По рассказам мамы и бабушки это было тяжелое и изнурительное путешествие. Вагон был товарный, так называемая теплушка, в которой были установлены двухъярусные нары, покрытые соломой. Спать было жестко, у всех нас тело было в синяках. Раз в день на станциях выдавали еду, за которой мама бегала в эвакуационный пункт, иногда очень далеко, подлезая под составами на соседних путях. При этом никогда не было известно, когда наш поезд тронется, и бабушка с дедушкой все время пребывали в ужасе, что мама отстанет от поезда. Но, наконец, это бесконечное бегство закончилось, мы приехали в Ленинабад, маленький городок в Таджикистане. Там был Педагогический Институт, куда мама смогла устроиться на работу. Нас поселили в общежитии для студентов. И хотя нам полагалось всего по 2 квадратных метра на человека, все равно это было счастьем, у нас была крыша над головой. С продовольствием, правда, всю войну было плохо. Я сама не помню эвакуацию из Ленинграда, дорогу и почти не помню жизнь в Ленинабаде. Помню только, что всегда хотелось есть. У меня сохранилось всего два очень ярких воспоминания о том времени. И оба они связаны с едой.

Одно воспоминание - я в очереди, она медленно движется к прилавку, на котором стоит большой алюминиевый бак полный восхитительных жареных пирожков с мясом. Эти пирожки выдавались студентам. Маме как преподавателю они были не положены. Но буфетчица тетя Гуля жалела меня, маленькую худенькую девочку из блокадного Ленинграда, и всегда тайком давала мне один пирожок.

Второе воспоминание - мы в гостях у маминого знакомого, какого-то начальника. У него дочка моего возраста. И нас с ней угощают необыкновенным лакомством. Это большой ломоть черного хлеба, щедро политый хлопковым маслом и посыпанный крупной солью. Много позже я поняла, что нерафинированное хлопковое масло невкусное, его надо

пережарить с луковицей, чтобы отбить очень специфический вкус и запах. Но тогда, в 1943 году, мне казалось, что ничего вкуснее на свете нет. У меня и сейчас при воспоминании о том куске хлеба с хлопковым маслом сразу начинается слюноотделение.

Мой отец остался в блокадном Ленинграде и погиб от голода в первую очень тяжелую военную зиму, в феврале 1942 года. Дедушка очень быстро умер в Ленинабаде. Я его совсем не помню.