*

http://www.inosr.net/inosr experimental sciences/ Kang’ethe etal

INOSR ExperimentalSciences9(1):33 47,2022.

©INOSR PUBLICATIONS

InternationalNetworkOrganizationforScientificResearch

ISSN:2705 1692 Prevalence, Factors Associated and Susceptibility Profile of Group B Streptococcus Anogenital Colonization among Third Trimester Antenatal Mothers at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital

Charles Kang’ethe1* , Yerine Fajardo1, Leevan Tibaijuka2, Ubarnel Almenares1, Maxwell Okello1 , Asanairi Baluku1, Rogers Kajabwangu1 , And James Nabaasa1

1Departmentof ObstetricsandGynecology, Kampala InternationalUniversityTeaching Hospital,Faculty ofClinical MedicineandDentistry, IshakaUganda

2Departmentof ObstetricsandGynecology, MbararaRegionalReferral Hospital,Mbarara Uganda

Corresponding author: Charles Kang’ethe, Kampala International University Teaching HospitalP.O. Box 71, Bushenyi, Uganda,Tel +256756066850, E mail: charlesmuniu84@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Group B Streptococcus (GBS), or Streptococcus agalactiae, are catalase negative gram positivecocciwhicharerecognizedaspartofthenormalfloracolonizinggastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. It is a normal component of the normal vaginal bacterial microbiome, but pregnancy offers good conditions for GBS multiplication in the vagina, sometimesleadingtoseriouscomplicationstothenewbornincludingpneumonia,sepsis anddeath.Themothermaysufferfromchorioamnionitis,endometritis,woundinfection, sepsis and death. The biggest risk factor for invasive GBS infection is rectovaginal colonization whose worldwide prevalence stands at 5 30%. Locally, data is sparse concerning the prevalence, associated factors and antibiotic susceptibility profile of rectovaginal colonization in pregnant mothers with this lethal organism. The purpose of this studywastodeterminethe prevalence, factors associatedandsensitivityprofilesof anogenital GBS colonization among third trimester antenatal mothers at Kampala InternationalUniversityTeachingHospital(KIU TH).Across sectionalstudyconductedat theantenatalclinicandpostnatalwardofKIU THbetweenAugustandOctober2021were used 348 women were recruited and rectovaginal samples taken. Culture for GBS was done and antibiotic susceptibility determined for positive cultures. Logistic regression was used to analyze data. The results showed the prevalence of GBS colonization among thirdtrimestermothersatKIU THwas10.1%(95%CI,7.3 13.7%).Inmultivariableanalysis, beingoverweight(aOR2.595%CI1.11 5.64, p=0.028)andhavinghypertensivediseasein pregnancy (aOR 4.97 95% CI 1.03 24.06, p=0.046) were found to be independently significant. All isolates in this study were resistant to ampicillin 10µg, ceftriaxone 30 µg andcefazolin30µg.Only1isolate(2.86%)wassensitivetoclindamycin2µgand3(8.57%) toerythromycin15µg.8isolates(22.86%)weresensitivetopenicillinG10µg,12isolates (34.29%) to vancomycin 30 µg, while the highest sensitivity;29 isolates (82.86%) was to imipenem 10 µg. GBS colonization in third trimester mothers at KIU TH falls within the worldwide prevalence. Being overweight or having hypertensive disease in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of GBS colonization. Isolates show high resistance to antibiotics commonly usedinpregnancy.

Keywords: GroupBstreptococcus,colonization,prevalence,factorsassociated,antibiotic susceptibility

INTRODUCTION

Group B Streptococcus (GBS), or Streptococcus agalactiae, are gram positive, catalase negative cocci which characteristically occur in pairs or small

chains. Nine serotypes are known to be normal flora in humans colonizing mucous membranes, especially the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts

33

[1] While it is part of the normal vaginal flora,excessivegrowthduringpregnancy cancause adversematernalandneonatal outcomes [2], including for the pregnant woman: chorioamnionitis, caesarean delivery, endometritis, wound infection and maternal sepsis. It can also cause preterm labor, PPROM and intrauterine fetal death[3]. Up to 2% of infected neonatesdevelopinvasivediseasewitha 5 20% mortality rate and serious complications especially among premature neonates. Sepsis and pneumonia are the most common infections in newborns followed by meningitis, cellulitis, osteomyelitis and septic arthritis[4]. The mother and baby are most vulnerable during labor and delivery where vertical transmission occurs when there is contact with or inhalation of vaginal fluid in a colonized vaginaltract[4] Worldwideprevalenceof maternal anogenital colonization is estimated to be between5 30%[3]

Over time, efforts to mitigate the effects of GBS have been made and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP) with penicillin G or ampicillin recommended. Cefazolin, clindamycin and vancomycin are used as second line drugs [5]. This approachminimizestransmissionduring deliverybyupto89%[6] However,Africa continues to bear the brunt of GBS disease with estimates that it accounts for 60% of infant mortality related to invasive GBS disease. It is also estimated that most of maternal invasive GBS disease happens in sub Saharan Africa [6]

In Uganda, death and disease in mothers and neonates due to sepsis continue to hinder our achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 3 that sets targets

regarding maternal and child health. There are no local protocols for GBS testing and prevention by IAP, despite a recent study by Namugongo and colleagues at Mbarara Teaching and ReferralHospital,Ugandashowingahigh colonization prevalence of 28.8% [7] We alsodonotknowwhich womenare more likely to have GBS colonization. With the recent observed rise resistance to commonly used antibiotics [8], [9] ,we have no information on whether the drugs of choice for IAP and treatment of GBS disease are effective in our setting. This study aims to fill this knowledge gap.

Aim of the study

This study aims at determining the prevalence, factors associated and sensitivity profiles of anogenital GBS colonization among third trimester antenatal mothers at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital(KIU TH)

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Committee, KampalaInternationalTeachingHospital; REC No KIU 2021 37. Following approval by the KIU REC, approval was sought from the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST), UNCST No HS1567ES. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant before recruitment and participation in the study. Confidentiality of the study participants was ensured by using unique identifiers. Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time during the study. Recruitmentintothestudywasvoluntary andfree.

METHODS

Study setting, study design and study population

This was a cross sectional study conducted at the antenatal clinic and prenatal ward of Kampala International University Teaching Hospital (KIU TH), Western Uganda between August 2021 and October 2021. KIU TH is located in Ishaka town which is a municipality in Bushenyi District. Ishaka is found approximately 62 kilometres west of Mbarara city. A minimum of 200 deliveriesareconductedinthematernity ward and around 500 women seen at the antenatal clinic per month. The study

participants came from catchment areas of Kampala International Teaching Hospital such as Bushenyi, Sheema, Rubirizi, Mitooma and other neighbouring districts. KIU TH was especially suitable for my study because of the large number of antenatal women seen monthly and the wide catchment area of the hospital. The laboratory department at KIUTH is well equipped and staffed to carry out growth, isolation, culture and sensitivity of specimen provided. It is well equipped with incubators, refrigerators, microwave ovensandautoclaves.

34

Our target population was all women with a gestational age of 35 42 weeks while our study population was all women with a gestational age of 35 42 weeks at the prenatal ward or antenatal clinicatKIU TH. Sample size and sampling Prevalence

Sample size calculation for cross sectional study using Kish and Leslie 1965formula: n=(Z2 × q×p) / d2

Z = Standard Normal variant corresponding to 95% confidence interval is 1.96

P = Proportion of women with GBS colonization according to a recent study done at Mbarara Regional Referral Hospitalthatrecruited309women at≥35 weeks gestation. 89 (28.8%) were GBS positive[7]

d=therequiredprecisionoftheestimate (0.05) q=(100 p) % n=(1.962×(1 0.288) ×0.288)/0.052 n=315.097

Adding 10 percent to cater for non response rate (316×0.1) =316+32 n=348 Sample size (n) =348 participants

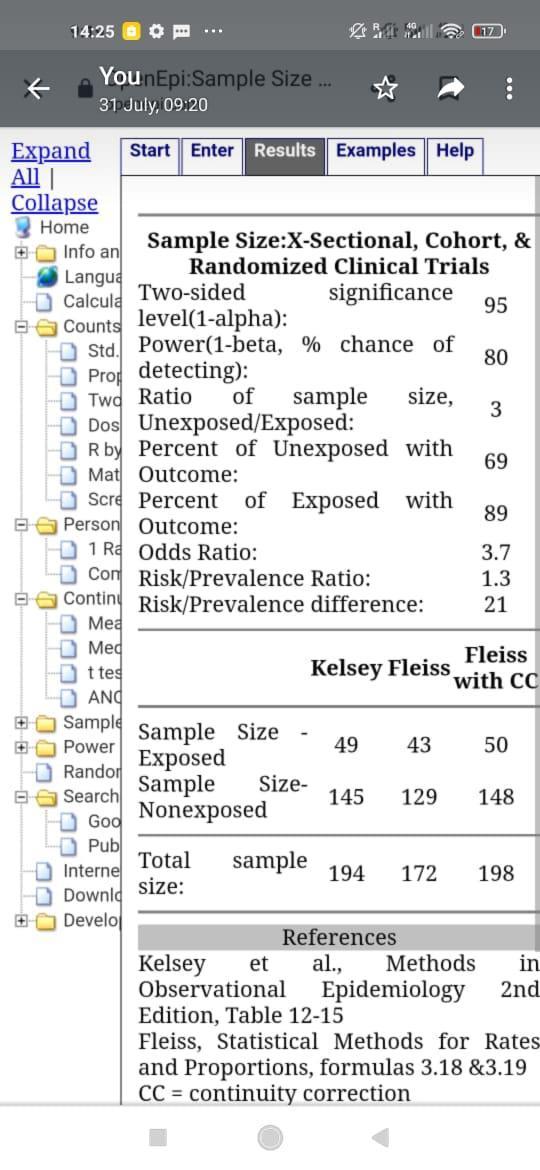

Factors associated

openepi.com online calculator used where obesity was significant as per the Namugongo study with an odds ratio of 3.78. An assumption was made that out of every 10 women, 3 have GBS colonization. Minimal sample size obtained was 198. Accounting for 10% lossto follow up n=220

Higher sample size (348) used

We enrolled the mothers in the prenatal ward and antenatal clinic who met the inclusion criteria into the study through consecutive sampling. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant before recruitment and participation inthestudy.

35

Data collection and study definitions

Data was collected using interviewer administered structured questionnaires. The questionnaire was first prepared in English and then translated to the local language (Runyankole). It was then translated back to English to ensure its consistency. The research assistants were three intern doctors, who were trained on data collection and study procedures

Our dependent variable was GBS anogenital colonization while the independent variables were social demographic characteristics such as maternal age & residence, marital status, level of education and socio economic status, obstetric factors such as gravidity, gestational age, history of still birth and medical factors such as HIV, diabetes, hypertension in pregnancyand BMI

Data analysis and presentation

Data on questionnaires were entered in REDCAP and thereafter exported to STATA 15 (Statacorp, USA Texas). Socio demographic, medical and obstetric factors were summarized as means and medians, standard deviations and interquartile range (for continuous variables) determined. Proportions, percentages and frequencies were used forcategoricalvariablesusingSTATA15.

Objective 1: Prevalence of GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester women in women was summarized as percentages and presented using pie chart. 95% confidence interval was used for estimation purposes.

Objective 2: Factors associated withGBS colonization in the third trimester of pregnancy were analysed by both bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis. Variables that were biologically plausible and those with p values p< 0.2 were considered for multivariate analysis. Interaction and confounding were assessed using chunk test (log likelihood and 10% cut off) respectively. The variables in the final multivariatemodelweresignificantwhen thep valuewaslessorequalto0.05.The measure of association reported was odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CI and p value. All statistical analysis was carried out in STATA version 15 (Statacorp, Lakeway Drive, USATexas).

Objective 3: GBS antibiotic susceptibility profiles were calculated in percentages with each common antibiotic classified as sensitive or resistant andpresented intables.

36

RESULTS

362 third trimester antenatal women at KIU-TH

14 women opted out

348 women were enrolled into study

Culture and sensitivity (348)

GBS positive=35 GBS negative=313

Figure 1. Flow chart for recruitment of study participants at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, southwestern Uganda, August 1st, 2021 October 31st, 2021

Socio demographic characteristics of study participants

The average age of participants was 27.8(±17.2) years with most residing in rural areas (87.1%). Most had a primary education (51.4%), were married (93.7%),

unemployed (56.9%), Banyankole (90.2%) and Christian (92.8%). There was no statistically significant difference in sociodemographic characteristics betweenthosewithGBScolonizationand those without

37

Table 1: Socio demographic characteristics of third trimester mothers at KlU TH

Variable Total (N=348), n (%)

GroupBStreptococcus (GBS), n(%) p value Positive (n=35) Negative (n=313)

Age (±SD) years 27.8(±17.2) 27.5(±5.6) 27.9(±18.1) 0.890

Age (Years) 0.846 <20 28(8.05) 3(3.57) 25(7.99) 20 34 277(79.60) 27(77.4) 250(79.87) >34 43(12.36) 5(14.29) 38(12.14)

Residence 0.427 Urban 45(12.93) 6(17.14) 39(12.46) Rural 303(87.07) 29(82.86) 274(87.54)

Distance from KIUTH 0.676 <5km 56(16.09) 6(17.14) 50(15.97) >5km 270(77.59) 26(74.29) 244(77.96) Unknown 22(6.32) 3(8.57) 19(6.07)

Level of Education 0.539 Uneducated 12(3.45) 2(5.71) 10(3.19) Primary 179(51.44) 15(42.86) 164(52.40) Secondary 103(29.60) 12(34.29) 91(29.07) Tertiary 54(15.52) 6(17.4) 48(15.34)

Marital status 0.708 Married 327(93.7) 34(97.14) 293(93.61) Unmarried 21(6.03) 1(2.86) 20(6.39)

Employment status 0.060 Employed 150(43.10) 14(40.00) 136(43.45) Unemployed 198(56.89) 21(60.00) 177(56.55)

Religion 0.712 Christian 323(92.82) 34(97.14) 289(89.47) Muslim 25(7.18) 1(4) 24(96) Tribe 0.056 Munyankole 314(90.23) 30(85.71) 284(90.73) Muganda 22(6.32) 1(2.86) 21(6.71) Mukiga 9(2.59) 3(8.57) 6(1.92) Others 3(0.86) 1(2.86) 2(0.64)

Personal income 0.697 <150,000 248(71.26) 24(68.57) 224(71.57) >150,000 100(28.74) 11(31.43) 89(28.43)

*p<0.05,

Obstetric and medical characteristics of study participants

In their obstetric and medical characteristics, most were multigravidas (44.3%)atgestationalagesbetween37 40 WOA (45.7%). Most had attended ANC ≥4 times and had no history of abortion (65.2%), stillbirth (73.6%) or early

neonataldeath(74.4%).Mostwereneither diabetic (98.6%) nor hypertensive (97.4%). Most were HIV negative (87.1%). There was no statistically significant difference in obstetric and medical characteristics between those with GBS colonization andthose without

Table 2: Obstetric and medical characteristics of third trimester antenatal mothers at KIU-TH

Variable Total (N=348), n (%)

GroupBStreptococcus (GBS), n(%) p value Positive (n=35) Negative (n=313)

Gravidity 0.857

38

SD: standard deviation, KIUTH: KampalaInternationalUniversity Teaching hospital

Primipara 145(41.67) 16(45.71) 129(41.21) Multigravida 154(44.25) 14(40.00) 140(44.73) GrandMultigravida 49(14.08) 5(14.29) 44(14.06)

Gestational age (in weeks) 0.361 35 37 148(42.5) 18(51.4) 130(41.5) 37 40 159(45.7) 12(34.3) 147(47.0) >40 41 (11.8) 5(14.3) 36(11.5)

History of PROM (current pregnancy) 0.147

No 326(93.68) 35(100.00) 291(92.97) Yes 22 (6.32) 0(0.00) 22(7.03)

ANC attendance 0.852 <4 117(33.62) 11(31.43) 106(33.87) ≥4 231(66.38) 24(68.57) 207(66.13)

UTI in current pregnancy 0.859 No 186(53.45) 18(51.43) 168(53.67) Yes 162(46.55) 17(48.57) 145(46.33)

History of abortion 0.373

No 227(65.23) 27(77.14) 200(63.90) Yes 48(13.79) 3(8.57) 45(14.38) N/A 73(20.98) 5(14.29) 68(21.73)

History of stillbirth 0.204 No 256(73.56) 30(85.71) 226(72.20) Yes 16(4.60) 0(0.00) 16(5.11) N/A 76(21.84) 5(14.29) 71(22.68)

History of early neonatal death 0.508 No 258(74.4) 29(82.86) 229(73.16) Yes 14 (4.02) 1(2.86) 13(4.15) N/A 76(21.84) 5(14.29) 71(22.68)

BMI 0.109 Normal (18.5 24.9) 173(49.71) 12(34.29) 161(51.44)

Overweight(25 29.9) 119(34.20) 17(48.57) 102(32.59) Obese (≥ 30) 56(16.09) 6(17.14) 50(15.57)

Smoking 0.273 No 345(99.14) 34(97.14) 311(99.36) Yes 3(0.86) 1(2.86) 2(0.64)

Alcohol 0.722 No 323(92.82) 32(91.43) 291(92.97) Yes 25(7.18) 3(8.57) 22(7.03)

Hypertension

0.051 No 339(97.41) 32(91.43) 307(98.08) Yes 9(2.59) 3(8.57) 6(1.92)

Diabetes 0.899 No 343(98.56) 35(100.00) 308(98.40) Yes 5(1.44) 0(0.00) 5(1.60)

HIV 0.516 No 303(87.07) 4(11.43) 41(13.10) Yes 45(12.93) 31(88.57) 272(86.90)

*p<0.05, PG= primigravida, PROM= premature rupture of membranes, BMI= body mass index, ANC= antenatal clinic, UTI= urinary tract infection and HIV= humanimmunodeficiencyvirus.

Prevalence of GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital The prevalence of GBS colonization amongthirdtrimestermothersatKIU TH was 10.1%(95%CI, 7.3 13.7%).

39

Group B Streptococcus Anogenital Colonization in 3rd Trimester Women at KIU-TH

35/348

positive negative

(10% 95% CI, 7.3 13.7) 313/348

10% 90%

Figure 2: Pie chart showing prevalence of GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at KIUTH

Factors associated with GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital

Socio demographic characteristics There were no statistically significant factors on univariable analysis of socio demographicfactors

40

Table 3: Univariable analysis of socio demographic factors associated with GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at KIU TH

Variable GroupBStreptococcus (GBS),n (%)

Univariable analysis p value Positive (n=35) Negative (n=313) cOR (95%CI)

Age (Years)

<20

3(3.57) 25(7.99) Ref. 20 34 27(77.4) 250(79.87) 0.90(0.26 3.12) 0.870 >34 5(14.29) 38(12.14) 1.10(0.24 5.0) 0.905

Residence

Urban 6(17.14) 39(12.46) Ref. Rural 29(82.86) 274(87.54) 1.45(0.57 3.72) 0.436

Distance from KIUTH

<5km 6(17.14) 50(15.97) Ref. >5km 26(74.29) 244(77.96) 0.88 (0.35 2.27) 0.804 Unknown 3(8.57) 19(6.07) 1.32(0.30 5.80) 0.717

Education

Tertiary 6(17.4) 48(15.34) Ref. Secondary 12(34.29) 91(29.07) 1.06(0.37 2.99) 0.920 Primary 15(42.86) 164(52.40) 0.73(0.27 2.00) 0.540 Uneducated 2(5.71) 10(3.19) 1.60(0.28 9.1) 0.596

Marital status

Married 34(97.14) 293(93.61) Ref. Unmarried 1(2.86) 20(6.39) 0.43(0.60 3.31) 0.418

Employment status

Employed 14(40.00) 136(43.45) Ref. Unemployed 21(60.00) 177(56.55) 0.66(0.30 1.49) 0.323

Religion

Christian

34(97.14) 289(89.47) Ref. Muslim 1(4) 24(96) 0.41(0.53 3.11) 0.384

Tribe

Munyankole 30(85.71) 284(90.73) Ref. Muganda 1(2.86) 21(6.71) 0.45(0.06 3.47) 0.444 Mukiga 3(8.57) 6(1.92) 4.73(0.13 19.90) 0.554 Others 1(2.86) 2(0.64) 4.73(0.07 0.15) 0.210

Personal income

<150,000 24(68.57) 224(71.57) Ref. >150,000 11(31.43) 11(71.57) 1.15(0.54 2.45) 0.711

*p<0.05; cOR: crude oddsratio; CI:Confidence Interval; Ref: Reference category, KIUTH: KampalaInternationalUniversity Teaching hospital

Obstetric and medical factors

In the univariable analysis of obstetric and medical factors, the only significant factors were being overweight (cOR 2.24

95%CI 1.03 4.88, p=0.043) and hypertensioncOR4.8095%CI1.15 20.10, p=0.032).Gestationalageof37 40 weeks (p=0.177) hadap value of<0.2

41

Table 4: Univariable analysis of obstetric and medical factors associated with GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at KIU TH

Variable

Gravidity

Primipara

Gestational age (in weeks)

GroupBStreptococcus (GBS),n (%)

Univariable analysis p value Positive (n=35) Negative (n=313) cOR (95%CI)

16(45.71) 129(41.21) Ref Multigravida 14(40.00) 140(44.73) 0.81(0.38 1.72) 0.577 GrandMultigravida 5(14.29) 44(14.06) 0.92(0.32 2.65) 0.872

35 37 12(34.3) 147(47.0) Ref. 37 40 18(51.4) 130(41.5) 1.69(0.79 3.65) 0.177 >40 5(14.3) 36(11.5) 1.70(0.56 5.14) 0.348

History of PROM (current pregnancy)

No 35(100.00) 291(92.97) Ref. Yes 0(0.00) 22(7.03)

ANC attendance

≥4

24(68.57) 207(66.13) Ref. <4 11(31.43) 106(33.87) 0.90(0.42 1.90) 0.772

UTI in current pregnancy

No 18(51.43) 168(53.67) Ref. Yes 17(48.57) 145(46.33) 0.11(0.07 0.17) 0.801

BMI Normal (18.5 24.9) 12(34.29) 161(51.44) Ref Overweight (25 29.9) 17(48.57) 102(32.59) 2.24(1.03 4.88) 0.043* Obese (≥ 30) 6(17.14) 50(15.57) 1.61(0.58 4.51) 0.365

Smoking No

34(97.14) 311(99.36) Ref. Yes 1(2.86) 2(0.64) 4.57(0.40 51.77) 0.219

Alcohol No 32(91.43) 291(92.97) Ref. Yes 3(8.57) 22(7.03) 1.30(0.37 4.60) 0.685

Hypertension No 32(91.43) 307(98.08) Ref. Yes 3(8.57) 6(1.92) 4.80(1.15 20.10) 0.032*

Diabetes No

35(100.00) 308(98.40) Ref. Yes 0(0.00) 5(1.60)

HIV No 4(11.43) 41(13.10) Ref. Yes 31(88.57) 272(86.90) 0.86 (0.29 2.55) 0.780

*p<0.05; cOR: crude odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; Ref: Reference category,PG= primigravida, PROM= premature rupture of membranes, BMI= body mass index, ANC= antenatalclinic, UTI= urinarytract infection and HIV= human immunodeficiencyvirus.

Multivariable analysis of factors associated with GBS colonization In multivariable analysis of socio demographic, obstetric and medical factors,beingoverweight(aOR2.595%CI 1.11 5.64, p=0.028) and hypertensive disease in pregnancy (aOR 4.97 95% CI 1.03 24.06, p=0.046) were found to be independentlysignificant.

42

Table 5: Multivariable analysis of factors associated with GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at Kampala International University Teaching hospital

Variable

Age (Years)

GBS Positive (n=35) (%)

Univariableanalysis Multivariable analysis cOR (95%CI) pvalue aOR (95% C.I) pvalue

<20 3(3.57) Ref. Ref. 20 34 27(77.4) 0.90(0.26 3.12) 0.870 0.84(0.23 3.08) 0.792 >34 5(14.29) 1.10(0.24 5.00) 0.905 0.94(0.19 4.56) 0.938

Residence

Rural 29(82.8 6) Ref. Urban 6(17.14) 1.45(0.57 3.72) 0.436 1.1(0.37 3.16) 0.887

Marital status

Married 34(97.1 4) Ref Ref Unmarried 1(2.86) 0.43(0.60 3.31) 0.418 0.33(0.04 2.98) 0.324

Gestational age (in weeks)

37 40 12(34.3) Ref. Ref. <37 18(51.4) 1.69(0.79 3.65) 0.177 1.61(0.72 3.58) 0.245 >40 5(14.3) 1.70(0.56 5.14) 0.348 1.60(0.51 4.99) 0.422

BMI

Normal (18.5 24.9) 12(34.2 9) Ref Ref. Overweight (2529.9) 17(48.5 7) 2.24(1.034.88) 0.04 3* 2.50(1.115.64) 0.028* Obese (≥ 30) 6(17.14) 1.61(0.58 4.51) 0.365 1.763(0.61 5.12) 0.297

Smoking No 34(97.1 4) Ref. Ref. Yes 1(2.86) 4.57(0.40 51.77) 0.219 8.32(0.64 108.77) 0.106

Hypertension in Pregnancy No 32(91.4 3) Ref. Ref. Yes 3(8.57) 4.80(1.15 20.10) 0.03 2* 4.97(1.03 24.06) 0.046*

HIV No 4(11.43) Ref. Ref. Yes 31(88.5 7) 0.86(0.29 2.55) 0.780 0.85(0.27 2.65) 0.781

*p<0.05; GBS: Group B streptococcus, cOR: crude odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; Ref: Reference category, BMI: body mass index, HIV: human immunodeficiencyvirus

43

Antibiotic Susceptibility profile of GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital

All isolates were resistant to ampicillin, ceftriaxone and cefazolin. Only 1 isolate

(2.86%) was sensitive to clindamycin and 3(8.57%) to erythromycin. 8 isolates (22.86%)weresensitivetopenicillinG,12 isolates (34.29%) to vancomycin, while the highest sensitivity; 29 isolates (82.86%)was to imipenem.

Table 6: Antibiotic susceptibility of GBS colonization in third trimester mothers at KIU TH

Susceptibility profile (n=35),% Antibiotic Sensitive Resistant

PenicillinG 8(22.86) 27(77.14)

Ampicillin 0(0.00) 35(100.00)

Vancomycin 12(34.29) 23(65.71) Cefazolin 0(0.00) 35 (100.00)

Ceftriaxone 0(0.00) 35(100.00

Clindamycin 1(2.86) 34(97.14)

Imipenem 29(82.86) 6(17.14) Erythromycin 3(8.57) 32(91.43)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

8 0

12 0 0 1

29 3

Group B streptococcus antibiotic susceptibity profiles in % % Antibiotics

Figure 3: Bar graph showing Antibiotic susceptibility of GBS colonization in third trimester mothers at KIUTH

DISCUSSION

Prevalence of GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at KIU-TH

The prevalence of GBS colonization amongthirdtrimestermothersatKIU TH was 10.1%, that is comparable to a study done at the Kenyan coast that found a prevalence of 11.7% [6] and another in Tanzania that had a prevalence of 11.8% [10]. This can be attributed to use of culture basedmethodstodetectGBSand similar socio demographic

characteristics of the participants. Similarly, the prevalence in Iran was reported at 11.8% [11] and that in Liuzhou China was 8.2% [12]. Both used culture basedmethods likein ourstudy. Lower prevalence was reported in India (2%) where the study was done on a socially privileged urban population [2]. Prevalence was also lower in Ganzhou China at 4.9%[13].

Locally, in Mbarara Uganda, GBS colonization was found to be high

44

Penicillin G Ampicillin Vancomycin Cefazolin Ceftiaxone Clindamycin Erythromycin Imipenem

(28.8%). In this study, antigen based techniqueswereused[7].Thehigherrate could be attributed to the fact that while culture based techniques are the gold standard, antigen based methods, despite the possibility of detecting non viable GBS, have a higher detection rate [14]. Additionally, GBS colonization in pregnantwomencanalsovarywithinthe same country due to differences geography, timing and where the sample was collected from [15]. Higher prevalence of colonization in pregnant women (21.6%) was also found by Edwards (2019) in USA who considered positive urine cultures in addition to recto vaginal ones [3]

Factors associated with GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at KIU TH

In this study, being overweight and having hypertension in pregnancy were found to be independently significant factorsassociatedwithGBScolonization.

Overweight

Compared to pregnant women with normalBMI,overweight womenweretwo and a half times more likely to have recto vaginal GBS colonization. Previous studies have shown a link between increasing BMI and GBS colonization. A USA studyfoundthatoverweight women were more likely to have anogenital GBS colonization than those of normal BMI [16]. In contrast other studies found obesity being a significant factor [7],[17] while others found there was no significantassociation [18,19,20]

The biologic mechanism of increasing GBS colonization with increasing BMI may be related to a shift in the lower digestive tract microbiome with increasing BMI. Studies have shown a shift towards the phylum to which GBS belongs (Firmicutes) with decrease in Bactreroides with increasing BMI due to their different energy absorbing properties, which favors the Firmicutes. Additionally, pregnancy is associated with similar changes in the gastrointestinal tract’s microbial composition [19,20, 21, 23, 24, 25]

Hypertension in Pregnancy

Inourstudy,awomanwithhypertension in pregnancy was found to be 5 times morelikelytohaveGBScolonizationthan onewithout.Thisisbackedbyastudyin the USA where a pregnant woman was

more likely to have GBS colonization if she hadhypertension [3]

Thereisnocurrentscientificexplanation for this phenomenon. We think this association is a result of the high incidence of hypertension in pregnancy intheregionwherethestudywascarried out.Assuchwethinkthattheassociation between Group B streptococcus anogenital colonization and hypertension in pregnancy is a coincidentalfinding.

Antibiotic Susceptibility profile of GBS anogenital colonization among third trimester mothers at KIU TH

GBS is known to cause significant illness and even death to the newborn and/ or the mother. The purpose of antenatal testing is to provide IAP at least 4 hours prior to delivery, which achieves up to 89% reduction in neonatal EOD [4] Penicillin or ampicillin is first line therapy. Cefazolin may be used for patients who are mildly allergic to penicillin while vancomycin or clindamycin may be used in those who areseverelyallergicto penicillins [5]

Inourstudy, eight antibiotics commonly used in pregnancy were used for susceptibilitytestingincludingpenicillin G, ampicillin, cephazolin, ceftriaxone, clindamycin, vancomycin, erythromycin, andimipenem.

Penicillin G (77.14%) and ampicillin (100%),thedrugsofchoiceinIAPshowed high resistance. This is similar to a Nigerian study where there was uniform resistance to both penicillin G and ampicillin [20]. This could be due to overuse of these antibiotics since penicillins are the commonly prescribed antibiotics for most bacterial infections [21]

Ceftriaxone and cephazolin showed uniform resistance. A recent study in Tanzaniafoundceftriaxoneresistance to be at 60% [10]. A study in Uganda evaluating the use of ceftriaxone shows that there is a high rate of inappropriate use (32%) and doses are not given to completion [22]. This could lead to resistance.

In our study, there resistance to vancomycin, erythromycin and clindamycin was 65.7%, 91.4% and 97.1% respectively. Antibiotic overuse directly influences emergence of resistant bacterial strains and these genes can be

45

inherited or acquired among different bacterial species. Antibiotics also eliminate drug sensitive strains leaving resistantbacteriabehindtoreproduceas aresultofnaturalselection [23,24,25].

Imipenem, showed the highest sensitivity(82.9%),probablybecauseitis expensiveandrarely usedinoursetting.

CONCLUSION

TheprevalenceofGBScolonizationin third trimester mothers at KIU TH falls within the global average.

Third trimester mothers are more likelytohaveGBScolonizationifthey have a higher BMI or have hypertensive diseasein pregnancy. GBS shows a high rate of antibiotic resistance to commonly used antibiotics inourlocality

Recommendations

A follow up study to find out outcomes of GBS colonized mothers andtheirnewborns

A clinical trial for commonly used antibiotics to determine their suitability in prophylaxis and treatmentof GBS infection

Authors’ contributions

CK, AB, UA, YF, MO, RK and JN contributedtotheconceptionanddesign ofthestudy.LTandCKperformedformal data analysis. CK, AB and JN contributed to drafting the manuscript. CK

contributedtostudyimplementationand data acquisition. JN, YF, RK and AB critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for key content. All authors readandapproved the finalmanuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Castellano Filho, D. S. (2010). DetectionofGroupBStreptococcusin Brazilian pregnant women and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology,. 41(4): p. 1047 1055

2. Khatoon, F. (2016). Prevalence and riskfactors forgroupB streptococcal colonization in pregnant women in Northern India. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology, 5(12): p. 4362.

3. Edwards, J. M. (2019). Group B Streptococcus (GBS) colonization and disease among pregnant women: a historical cohort study. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology, 1064 7449

4. Raabe, V. N. and Shane, A. L. (2019). Group B Streptococcus (Streptococcus agalactiae). Gram PositivePathogens, p. 228 238.

5. Arif, F. (2018). Updated Recommendations Of Rcog On Prevention Of Early Onset Neonatal Group B Streptococcus Infection. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad, 30(3): p. 489 %@ 1819 2718.

6. Seale, A. C. (2016). Maternal colonization with Streptococcus agalactiae and associated stillbirth andneonataldiseaseincoastalKenya.

Naturemicrobiology, 1(7):p.1 10%@ 2058 5276.

7. Namugongo, A. (2016). Group B streptococcus colonization among pregnantwomenattendingantenatal care at tertiary hospital in rural Southwestern Uganda. International journalof microbiology, 3(1): 12 35.

8. Byonanuwe, S. (2020). Bacterial pathogens and their susceptibility to antibiotics among mothers with prematureruptureofmembranesata teaching hospital inwestern uganda, 3(7):p. 386 394.

9. Ainomugisha, B. (2021). CERVICAL AMNIOTIC FLUID BACTERIOLOGY, ANTIBIOTIC SUSCEPTABILITY AND FACTORS ASSOCIATED AMONG WOMEN WITH PREMATURE RUPTURE OF MEMBRANES AT MBARARA REGIONALREFERRALHOSPITAL

10.Kwetukia, F. R. (2020). Prevalance, predictors and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of group B streptococcus colonization among pregnant women and newborns at Iringaregionalreferralhospital. The Universityof Dodoma.

11.Darabi, R. (2017). Theprevalenceand risk factors of Group B streptococcus colonization in Iranian pregnant women. Electronic physician, 9(5): p. 4399.

12.Chen,J.(2018). GroupBstreptococcal colonizationinmothersandinfantsin

46

western China: prevalences and risk factors. BMC infectious diseases, 18(1): p. 291%@ 1471 2334.

13.Chen, Z. (2019). Group B streptococcus colonisation and associated risk factors among pregnant women: A hospitalbased study and implications for primary care. International journal of clinical practice, 73(5): p. e13276 %@ 1368 5031.

14.Konikkara, K. P. (2014). Evaluationof culture, antigen detection and polymerase chain reaction for detection of vaginal colonization of group B Streptococcus (GBS) in pregnantwomen, 8(2): p. 47.

15.Ali, M. M. (2019). Prevalenceofgroup B streptococcus among pregnant women and newborns at Hawassa University comprehensive specialized hospital,Hawassa,Ethiopia, 19(1): p. 1 9.

16.Venkatesh, K. K. (2020). Association betweenmaternalobesityandgroupB Streptococcus colonization in a national US cohort, 29(12): p. 1507 1512.

17.Manzanares, S. (2019). Maternal obesity and the risk of group B streptococcalcolonisationinpregnant women, 39(5):p. 628 632.

18.Najmi, N. (2013). Maternal genital tract colonisation by GroupB Streptococcus:Ahospitalbasedstudy. Journal Pakistan Medical Association: JPMA, 63(9): p. 1103.

19.Kleweis,S.M.(2015). Maternalobesity and rectovaginal group B streptococcus colonization at term. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology.

20.Onipede, A. (2013). Group B Streptococcus carriage during late pregnancy in IleIfe, Nigeria. African Journal of Clinical and Experimental Microbiology, 13(3):p. 135 143.

21.DeTejada,B.M.(2014). Antibioticuse and misuse during pregnancy and delivery: benefits and risks, 11(8): p. 7993 8009.

22.Kutyabami, P. (2021). Evaluation of theClinicalUseofCeftriaxoneamong InPatientsinSelectedHealthFacilities inUganda. 10(7): p. 779.

23.Ventola, C. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistancecrisis:part2:management strategies and new agents. Therapeutics, 40(5): p. 344.

24.Yves Tibamwenda Bafwa, Dafiewhare Onokiojare Ephraim, Charles Lagoro Abonga and Sebatta Elias (2022).FactorsAssociatedwithElectroc ardiographic Abnormalities among Heart Failure Patients at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Ishaka, Uganda. IAA Journal ofBiological Sciences 9(1):166 175.

25.Yves Tibamwenda Bafwa, Dafiewhare Onokiojare Ephraim, Charles Lagoro Abonga and Sebatta Elias (2022). Electrocardiographic Pattern among Heart Failure Patients at Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Ishaka, Uganda. IAAJournal of Biological Sciences 9(1):159 165 2022.

47